49 minute read

References / Resources

from Sustainable Shared Sanitation Post-COVID : A Design Guide to Low-Income Peri-Urban Areas

by Daryl_Law

Management of sanitation for COVID-19

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Water, sanitation, hygiene and waste management for SARS-CoV-2, the virus the causes COVID-19.

Advertisement

UNICEF (2020). Handwashing stations and supplies for the COViD-19 response.

Shared sanitation in Accra / Ghana

Antwi-Agyei, P., Dwumfour-Asare, B., Adjei, K.A., et al. (2020). Understanding the Barriers and Opportunities for Effective Management of Shared Sanitation in Low-income Settlements - The Case of Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17:4528.

Appiah-Effah, E., Duku, G. A., Azangbengo, N. Y., et al. (2019). Ghana’s post-MDGs sanitation situation: an overview. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 9(3).

Ayee, J,, and Crook, R. (2003). Toilet Wars: urban sanitation services and the politics of public-private partnerships in Ghana.

Mazeau, A. P. (2013). No toilet at home: Implementation, Usage and Acceptability of Shared Toilets in Urban Ghana.

Mansour, G. and Esseku, H. (2017), Situation analysis of the urban sanitation sector in Ghana. Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP).

NIkiema, J., Olufunke, C., Imrpaim, R., et al. (2015). The Excreta Flow Diagram: A Tool for Advocacy and a Wake Up Call for All. Presentation.

Shared toilet management models

Cardone, R., Schrecongost, A., and Gilsdorf, R. (2018). Shared and Public Toilets: Championing Delivery Models That Work. The World Bank Group.

Gender- and age- inclusive shared toilets

WSUP (2018). Female-friendly public and community toilets: a guide for planners and decision makers.

WSUP (2018). Female-friendly public and community toilets: a guide for planners and decision makers.

Sanitation Technologies

Sanitation Value Chain

Nikiema, J., Impraim, R., Gebrezgabher, G., et al. (2015). The Excreta Flow Diagram: A Tool for Advocacy and A Wake Up Call for All. International Water Management Institute.

How can the design of (existing and future) shared sanitation facilities in urban Ghana be improved in response to challenges arising from COVID-19?

A systematic literature review as part of Research Methods: Trandisciplinary Urbanism

Joshua Baker, Hannah Byrom, Jian Gao, Daryl Law, Bethany Stewart, and Yuxi Yang

Abstract

SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) has brought unprecedented interruption to our daily lives. Subsequently, an abundance of research highlights the various transmission pathways of the virus. However, such findings have not been applied to shared sanitation facilities to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In Africa, approximately 638 million people use shared facilities with over 60% of the population without access to improved sanitation (World Health Organization, 2018a; World Health Organization, 2018b). This systematic literature review aims to address the vulnerabilities of shared sanitation facilities in Accra, Ghana introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic. This review concludes by suggesting recommendations to prevent transmission of the virus within these environments and looks to form a larger conglomerate of information for the World Toilet Organisation (WTO).

Keywords: Covid-19, Shared Sanitation, Public Toilets, Accra, Ghana,

Introduction

An estimated 800,000 people die annually from diarrhoea and other related diseases due to unsafe water, poor sanitation and hygiene (WHO, 2018). The target, set out by The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is to eliminate open defecation by 2025 and introduce household sanitation facilities by 2040 for all (Ritter et al., 2018).

Improved sanitation is a toilet facility that protects human health by preventing contamination of the environment with human faecal waste (Rheinlander, 2015). Also, shared facilities are sanitation of an otherwise acceptable type shared between two or more households (WHO, 2015). Based on this classification, approximately 638 million people use shared facilities (Sagoe et al., 2019). In Africa, over 60% of the population does not have access to improved sanitation, while 40% of the rural population openly defecate (Sagoe et al., 2019). This figure is unlikely to change due to a lack of space and financial barriers in impoverished urban areas (Ritter et al., 2018).

Ghana is in West Africa, along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean. The focus of this literature review is the city of Accra, the capital city of Ghana. Accra is one of the 16 administrative regions, and it has an estimated population of 1,848,614 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2010).

Accra comprises of densely populated urban slums. The term ‘slum’ is a neighbourhood that lacks access to improved water or sanitation, security, the durability of housing, sufficient-living area (UN, 2015). These are the focus of our literature review.

Between 2000 and 2006, it had an average annual population growth rate of 2%. However, this figure could rise to 2.4% between 2016 and 2030 (Musah et al., 2020). Rapid urbanization has put a strain on infrastructure and the provision of adequate sanitation facilities (Mariwah, 2018; Appiah-Effah et al., 2019). Approximately 19% of Ghanaians practice open defecation and, another 66% use unimproved or shared facilities (Ritter et al., 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the issues faced by residents of informal peri-urban settlements who rely on shared toilets. The paper will discuss recommendations identified through the analysis of relevant literature.

Methodology

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the methodology for this qualitative and quantitative grounded theory study, regarding how existing and future shared facilities in urban Ghana can be improved in response to challenges arising from COVID-19. The approach provided a deeper understanding of these facilities to identify practices to limit the spread of infection.

Before identifying relevant literature, we devised a criterion of inclusion/exclusion. Specifically, the focus of our review is shared sanitation facilities within informal settlements in Accra, Ghana. We have excluded literature on rural communities of Ghana along with private household facilities.

Each researcher identified 20 items of literature and grouped them by category. For example, literature classified under 'Ghana and Shared Sanitation Facilities', are divided into five subheadings: access, availability, standards, norms and perceptions, and maintenance. Finally, in batches of four, each text was analysed through coding and allowed us to reflect and organise data as trends began to emerge.

Language Population / Subject User

Public sanitation facilities in Urban Ghana (Accra) Sanitation facility types 1 Toilets

Toilet types

English Communities in Urban Areas (Kumasi and Accra) 1 Pit latrine 2 Dry composting toilet 3 Flushing toilet

Accra 1 Changing facilities 2 Breastfeeding facilities Toilets in private households

Non-English Communities in rural areas of Ghana

For Comparison Urban Settlements Informal and formal settlements; lowmedium-high density

Time frame

2000 - Present Research earlier than 2019 that are related to built environment, public health, urban planning, etc. Pre-2000 Material

Type of Literature

Peer-reviewed journals World Health Organization Nature National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Google scholar, JSTOR

Single / multi author books Edited books Grey literature Not peer-reviewed, but completed with supervision and consultation of academic staff or specialists in related fields Wikipedia

Fiction

Poetry Blogs

Research design / Sampling methodology

News Articles Specialist Reports Thesis (PhD) Posgraduate dissertations Literature with 'shelf-life' - eg Sanitation Policy 20202030 Qualitative Prose

Quantitative

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Review (Law et al., 2020)

COVID-19 Transmission Pathways

In December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan, China. Early transmission into the human population is speculated to be via consumption of wild animals, particularly bats (Mackenzie and Smith, 2020). Human-to-human transmission occurs from close exposure to an infected person via aerosols. Aerosols are virus-carrying particles that infiltrate the body by inhalation through the nose or mouth (Shereen et al., 2020). Increased transmission risks occur between family members due to long-term, highfrequency contact (Guo et al., 2020).

Ozyigit (2020) studied the relationship between the transmission rate and changes in air temperature and humidity. He argues that climate warming could slow down transmission and, the results showed that strains survived longer in lower temperatures and relative humidities. Data analysis shows the transmission rate of COVID-19 will decrease by 0.9% for every degree of increase in temperature. Also, COVID-19 has shown substantial transmission potential before symptoms appear (He et al., 2020). Toilets are high-risk sites, especially when shared between households and large groups (public facilities). COVID-19 is present in infected people's excrements, and many have experienced gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhoea, therefore concerns remain over faecal-oral transmission (Nomoto et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). The prevalence of water-based toilets, malfunctioning infrastructure, unsafe sanitary habits, and inadequate maintenance could further increase the cross-infection risks of open-lid flushing (Li et al., 2020). A recent study identified COVID-19 as 'both waterborne and non-waterborne' therefore, it is imperative to consider the transmission of the virus via wastewater systems (Dasheng et al., 2020).

Concerns remain regarding the implications of COVID-19 in low-income countries. Impoverished areas lack the required infrastructure (e.g., hand washing stations), resulting in poorly exercised hygiene practices, thus accentuating the concern of transmission surrounding sanitary and wastewater infrastructure (Dasheng et al., 2020). It can be challenging for families and communities to adhere to government restrictions due to over-crowded living environment and religious practices (Corburn, 2020). Improvements have been implemented, such as immediate food assistance; instituting

informal settlement emergency planning committees; and meeting Sphere humanitarian standards for water, sanitation and hygiene (Corburn, 2020). Moreover, decentralized wastewater treatment facilities, that use low-cost strategies for highly effective disinfection, may benefit regions not connected to centralized water and sanitary networks (Dasheng et al., 2020). Although unlikely, transmission by contaminated water sources could lead to oral infection (Dasheng et al., 2020).

Predominantly, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been negative. However, there have been positive strides within urban design, such as creating better FDA standards and employing drones to deliver testing samples and PPE equipment (Afriyie et al., 2020). Technical strategies to reduce transmission within the built environment pertain to light, ventilation, abiotic surfaces, fomites, and spatial configurations (Dietz et al., 2020). However, human-tohuman transmission remains the most prevalent transmission pathway and tackling the pandemic within sanitary facilities calls for intelligent design and improved provision of related infrastructure. In turn, this will enable attentive use between users and promote better hygiene practices.

Ghana and Shared Sanitation Facilties

Access

Improved sanitation is defined as “toilet facilities that protect human health by preventing contamination of the environment with human faecal waste” (Rheinlander, 2015). In 2015, Ghana had achieved 14% improved sanitation access and an open defecation rate of 11% (World Health Organisation, 2015; Appiah-Effah et al., 2019).

Approximately 72% of the urban population of Ghana use shared facilities (Peprah, 2015). In 2014, 60% of the residents were without indoor toilets, and only 4.5% of Ghana’s population have access to sanitation facilities which are connected to a sewer network (Virginia et al., 2020). Therefore, open defecation has become a common phenomenon, especially among residents in resource-poor areas.

In 2012, there were 340 registered public toilet facilities (Peprah et al., 2015). The barriers to use include woman and child safety, risk of violence towards women, and lack of provisions for young children (Peprah et al., 2015). Moreover, 79% of Ghanaians lived in compound houses and shared water, electricity, and sanitation between several households (Rheinlander, 2015). Access to private household latrines was 2.7% (Ritter et al., 2018).

In Accra, 15% of the land area is connected to a sewer network, and the remainder of the public toilets have septic systems, pit latrines, or VIP latrines (Sagoe et al., 2019).

Within the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, 41% rely on payper-use public toilets, 33% have private sanitation facilities, 3% use bucket or pan latrines, and 7% do not have access to any improved sanitation facility (Robb et al., 2017). A study, commissioned by the Water Engineering and Development Centre (WEDC), found that 92% of respondents believed Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) face difficulties accessing toilets. 75% of PWDs stated that the main challenge was with the design of facilities. In the context of KVIP Latrines, the requirement to squat and the height of the seat are constant obstacles, and toilets are too small, dark and narrow (Ivy and Hazel, 2018). They are usually not considered in infrastructural designs and development (Ivy and Hazel,

Fig. 1 Bucket Latrine. Source: http://www.clean-water-for-laymen.com/best-sanitation.html

Fig. 2 Pit Latrine Source: https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/my-resources/graphicsbrowse-display.html?x=LBAS

Fig. 3 Pour Flush Toilet Source:http://www.open.edu.openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view. php?id=80510&sec-tion=8.1

Fig 5. Kumasi Ventilated Improved Pit Latrine (KVIP) Source:https:// repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/figure/A_twin-pit_ventilated_improved_ pit_latrine/7957586/1

A study, undertaken by Peprah (2015), analysed the physical conditions of public toilets and rates of use among the population in four Accra neighbourhoods: Alajo, Bukom, Old Fadama and Shiabu. In Bukom, they found 72% of compounds did not have a toilet (Peprah et al., 2015). Additionally, 93% and 98% of homes in Bukom and Old Fadama lacked sanitation facilities, compared to 42% and 54% of households in Alajo and Shiabu (Peprah et al., 2015). Bathing facilities were present in 38% of the public toilets, along with very few hand washing facilities and the cost of using these facilities ranged from US$ 0.08–0.15 per use (Peprah et al., 2015).

Monney (2013), found that there are 39 public toilet facilities in Old Fadama, of which 76% are Pan Latrines and, 24% are KVIPs. 635 squat holes serve a population of 80,000 people (Monney et al., 2013). The current population is approximately 100,000 people (Amnesty International Ghana, 2018). Limited or no household toilet facilities are available, and residents rely on poorly maintained public toilets whilst others, mostly men and children, resort to open defecation (Monney et al., 2013). Consequently, this has resulted in faecal contamination of the environment, the transmission of gastroenteric infections, and a diminished quality of life (Monney et al., 2013). In these communities, the use of Kumasi Ventilated Improved Pits (KVIPs) and Pan latrines costs approximately US$0.1 per visit (Monney et al., 2013). Sabon Zongo has two main public toilets and six privatelyowned public toilet facilities, used by approximately 6,000 people (Owusu, 2010). Severely low sanitation coverage figures recorded in Sabon Zongo, Old Fadama, Nima, and Teshie, coincide with Kumasi’s informal settlements (Adubofour et al., 2013; Amoako and Cobbinah, 2011; Monney et al., 2013; Owusu, 2010). Service charges across all four settlements are considered unaffordable, and all communities significantly lack refuse dumpsites (Adubofour et al., 2013; Amoako and Cobbinah, 2011; Monney et al., 2013; Owusu, 2010).

Standards

Lack of sanitation infrastructure stems from the colonial period, where municipal governments gave low priority to sanitation systems (Freeman, 2010). Since then, Ghana’s National Environmental Sanitation Policy (1999), revised in 2009, covers sanitation, food hygiene, solid waste, excreta disposal, and reflects Ghana’s overall commitment to decentralization (WEDC, 2005). Past efforts to provide sanitary excreta disposal, by constructing institutional latrines, became ineffective due to social and economic reasons. Many sanitation facilities fell into disrepair; hence the UN does not identify communal latrines as improved sanitation (Dumpert, J, 2008). Since then, the 2007 National Water Policy took effect, underpinned by the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) (Government of Ghana, 2007); education proved to be instrumental in ‘ensuring change in behaviors and attitudes towards fundamental principles of hygiene’ (Government of Ghana, 2007:42). Following in 2017, The Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD) issued the Construction of Institutional Sanitation Facilities (2017), which focused on improved sanitation in schools. This document outlined practical construction mitigation about accessibility and the provision of ramps, landscaping, drainage, flooding measures, and security (MLGRD, 2017).

More recently, President Nana Akufo-Addo committed to improve and reform sanitation during his term (Mansour and Esseku, 2017), and the Ghana Standards Authority (2018) published its first building code, establishing the minimum requirements for buildings including sanitation facilities. Nevertheless, as of 2019, there is only 21% basic sanitation coverage (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019) and Ghana has failed to meet its MDG for sanitation (Mansour and Esseku, 2017). The responsibility of sanitation byelaws belongs to Metropolitan Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs), which have not prioritized sanitation or effectively enforced them (WEDC, 2005; Mansour and Esseku, 2017).

Norms & Perception

With few adequate sanitation facilities, residents express common concerns alluding to cost, cleanliness, and safety. Many complain about the filthiness and discomfort of shared facilities and consider the high risk for disease – women often fear contracting vaginal yeast infections by touching dirty latrine seats (Van der Geest, 2013; Hurd et al., 2017). Frequent toilet trips become overly expensive, and factors alongside accessibility, safety, distance to latrines and lengthy morning queues engender people to practice alternative defecation methods. These include the use of take away bags, containers, chamber pots, and open defecation (Hurd et al., 2017).

In Ghana, social-cultural attitudes, educational attainment, and commonplace perceptions contribute to the lack of compliance with sanitation standards and practices (AppiahEffah et al., 2019). For example, estimated daily exposure of fecal contamination for young children was more than 10,000 times higher in Shiabu than Alajo – suggesting that exposure to fecal contamination, is determined by more complex factors (Robb, 2017). Many openly defecate due to beliefs that public toilets are heinous places (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019). On the other hand, the majority in Southern Ghana perceive excreta to be unclean and therefore demonstrate the importance of washing hands (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019).

A study conducted by Odonkor (2020) reveals that 26.5% of respondents who reported environmental problems did not link poor sanitation to diseases such as malaria or diarrhea, highlighting a lack of knowledge. Data also suggests that younger people and those who are more educated are most likely to participate in the improvement and design of environmental policy. Further education of the sanitation related health problems could improve community awareness thus improving hygiene practices (Odonkor, 2020).

Maintenance

Since the 1990s, lower government levels and private companies, manage public toilets. They are controlled and supervised by district cleansing officers who, are expected to clean toilets daily (Sagoe et al., 2019).

Guidance on the maintenance of KVIP latrines includes keeping the latrine clean, allowing minimal light into the privy room to prevent insects and flies, use paper or decomposable materials to clean themselves. They are advised to repair any cracks and damage to the mesh on the vent pipe to prevent flies from entering (CHF International, 2010).

Sanitation waste is managed by centralised, semi-centralised or on-site sanitation systems and this is dependent on available resources, socio-economic context, legal or institutional conditions and the type of system (Sagoe et al., 2019; Van der Geest, 2002).

Fees are charged to public toilet users to pay for disposing faecal waste from the VIP latrine tanks. Every 2-3 years, septic tanks are emptied, and low funds continue to make management and maintenance difficult (Sagoe et al., 2019). There are little to no personal protective measures for the personnel engaged in waste treatment, and they face the risk of faecal-oral transmission (Kretchy et al., 2020; Grieco, 2009).

Large numbers of toilet users, in high population density areas, result in tanks filling up quicker. Thus, these require frequent emptying, which increases cost. There is low government expenditure to ensure sustainable disposal of waste and maintenance of the public toilets (Sagoe et.al., 2019). The illegal sector charges less for emptying services, typically with disposal of faecal sludge directly into the environment (Boot, 2009). The main faecal sludge dumping point is at Korle Gono, and it is discharged into the ocean or onto surrounding land completely untreated. Furthermore, waste stabilisation ponds at Teshie are not working effectively (Boot, 2008). There are two problematic methods of personal disposal. The first includes removing and dumping of waste from homes by children. Secondly, households dispose of faecal waste within the general garbage dumpsites, which is hazardous to garbage collectors (Grieco, M, 2009).

Vulnerabilities in Shared Toilets in urban Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic

Faecal Sludge Management, Sewerage Service & Risks of Faecal-Oral Transmission

This review considers the potential implications to the urban environment that is connected to shared sanitation. Ongoing studies have compared SARS-CoV-2 to known viral diseases that are structurally similar and transmit via wastewater (Bhatta et al., 2020). However, only further research may prove the transmission of COVID-19 via environmental faecal matter or via the faecal-oral pathway. Nonetheless, in Ghana, COVID-19 patients that contracted the virus, from sharing toilets, have been transferred to regional isolation centres with independent toilets and centralized faecal sludge treatment systems (Spangenberg, 2019).

An earlier study by Berendes et al. (2018), suggests that high local coverage of contained sanitation, including shared sanitation, may reduce environmental faecal contamination. The researchers measured E. Coli concentrations in the public domain of low-income areas in Accra. The study lends insight into the link between type and coverage of sanitation facilities, and environmental faecal contamination. ‘Uncontained’ facilities (bucket latrines or other types), as opposed to, ‘contained’ facilities (KVIP latrines, flush toilets into septic systems, covered pit latrines), lead to the discharge of untreated excreta into open drains. Thus, resulting in a high-risk faecal exposure pathway (Berendes, 2018). The study suggests that containment of faecal sludge in shared sanitation facilities, despite the high number of shared users, may reduce environmental faecal contamination (Berendes, 2018). Findings from the paper call for further research examining the whole sanitation chain to ensure safe, sustainable sanitation in urban areas.

Another study by Robb et al (2017), used the SaniPath tool to identify that the dominant faecal exposure pathway in a lower-income area of Accra links sanitation and urban agriculture. There is no public wastewater treatment system in Accra, and over 50% of households discharge excreta into open drains, yet the drain water, is commonly used for irrigation (Wallace et al., 2020; Robb, 2017). Urban agriculture is the main food supply channel in Accra, along with many sub-Saharan African countries (Robb, 2017). The agricultural products irrigated by sewage could move from low-income areas to middle- and high-income areas as vectors of viruses (Robb, 2017).

The quality of shared sanitation in lower-income areas is affected by urban infrastructure, city administration, and the local economy (United Nations, 2015). Considering COVID-19, it is not unreasonable to address in advance the whole sanitation chain. Among the immediate targets is to reduce untreated excreta and wastewater exposed to the private and public domain. As flooding has become a serious environmental problem in Ghana (Keraita and Amoah, 2011), increased the possibility of contamination of open drainage. In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a “safely- managedsanitation” strategy, including abandoning open drainage system as the choice of discharge and transportation (United Nations, 2015).

Ghana's own social, economic, and related policies make Ghana have the highest public facilities dependence rate in the world (59%) (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019). In low-income neighbourhoods, Accra has approximately 68% of the population renting compound houses with 1-2 shared toilets (Dispatch et al., 2020; Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020).

Typically, landlords construct a shared facility within their property, and the tenants pay for the use and maintenance (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020). Private shared toilets have four advantages: 1. Flexible using time; 2. Closer using distance compared with public facilities; 3. Higher security and privacy; 4. Lower cost compared with public toilets (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020). However, there could be up to three families sharing the same toilet due to space constraints.

A study by Antwi-Agyei et al. (2020) indicated overcrowding during use, children soiling the toilet, and other behaviours, severely reducing useability. Gender separation in shared facilities is rare; males and females use the same latrine. Due to the pandemic, much of the population spend more time at home, dramatically reducing social efficiency. Moreover, the shortage of materials makes it a challenge to build new, temporary sanitation facilities. The capacity of the shared toilet could increase and would soon experience frequent crowding (Durizzo et al., 2020).

Commonplace issues include water supply burden from more frequent flushing, improper use leading to faecal contamination, inadequate cleaning practices, or conflict with cleaners (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020). Tenants are highly unlikely to pay for toilet use if costs rise due to more frequent cleaning schedules. Culturally, women are responsible for family health and are responsible for cleaning the toilet (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020). As a result, the home workload may increase significantly during the pandemic. Families without women omit the cleaning schedule, heightening transmission fears in a compound house (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020). Everyone is responsible for the daily cleaning of their private areas, and in some public spaces, the cleaning is organised according to an oral agreement (community rota). Selfprovided cleaning tools include brooms, brushes, detergents, water, and disinfectants (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2020).

Although the government has provided water and other materials to ease household expenditure pressures, COVID-19 has negatively impacted most residents (Durizzo et al., 2020). Additionally, due to the high dependence on public facilities, the government did not order shared toilets to close in Ghana. Ultimately, to control the spread of COVID-19, it will cost the government much more than previously envisaged.

Addressing Water Insecurity

Sanitation is part of the broader, interdependent WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) sector. The sector contributes to viral containment and alleviates marginalised communities associated with low WASH levels (Amankwaa and Fischer, 2020). Amankwaa and Fischer (2020), found that poor access to safe sanitation and drinking water are associated with higher COVID-19 fatality rates in sub-Saharan Africa. Albeit, they acknowledge that more robust research is required to establish causality between the two variables.

Since April, the Ghanaian government has waived all domestic and non-commercial water tariffs as an economic relief across the country. Smiley et al (2020) assert that the directive may have not fully considered Ghana’s complex water source types and user groups, despite its aim to alleviate water insecurity and contain the pandemic. Firstly, shared sanitation facilities that are prevalent in informal settlements are excluded from the free water directive, thus they still impose financial burden on most low-income households (Smiley et al, 2020). This also challenges their ability to social distance and limit exposure to pathogens, in turn encouraging open defecation; also, handwashing appliances are still lacking in these facilities. (Smiley et al, 2020). Second, most urban low-income households lack piped water supply and would rely on private water tankers and vendors who expect reimbursement by the government. However, these households may not afford large and secure water storage or be able to transport large amounts of water from the source (Smiley et al, 2020).

Accelerated Investment in Improved Sanitation

COVID-19 has accelerated the decision by The World Bank to finance an additional $125 million to the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area Sanitation and Water Project (GAMASWP) (The World Bank, 2020). The additional financing aims to reduce open defecation, sanitation-related disease, absenteeism of menstruating schoolchildren, freshwater pollution and storm floods. These are achieved via the construction of more household toilets in low-income areas (some with subsidies), toilets in needy schools and healthcare facilities, new water supply connections, improved technical training to tackle leaks and inaccurate metering, and strengthen drainage infrastructure (GSWR, 2020).

Increasingly, particularly in flood prone low-lying areas, septic tank liquid waste is directly discharged into drains. The growth of urbanization has caused the frequency of floods to increase and flood water is likely to be contaminated with faeces and pose a risk to public health (Ashley et al., 2005). For Accra, flooding has become a serious environmental obstacle and with rising sea levels, may become a greater threat to the improvement of the sanitation value chain (Keraita and Amoah, 2011).

Although GAMA-SWP addresses the need for toilets in the public realm, it overlooks the dependence, now and for the immediate future, on shared sanitation facilities by most people in low-income neighbourhoods. GAMA-SWP targets improved sanitation, the de facto indicator for universal sanitation access in the WHO Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and is monitored by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) (Evans et al., 2020). Improved sanitation excludes shared toilets due to disparities in their service level that make monitoring difficult (Evans et al., 2020). Although planners and donors of GAMA-SWP describe a commitment to provide equitable access to improved water supply and sanitation services (The World Bank, 2020), it is unclear whether or how all low-income households in GAMA will be beneficiaries. Studies have shown that the prevalence of shared toilets is influenced by spatial limitations in these housing types and how the tenant-landlord relationship itself disincentivizes investment by landlords (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019: 403; Awunyo-Akaba et al, 2016; Mansour and Esseku, 2017). The complex, dense peri-urban built environment presents significant technical challenges, thus drawing concern whether financed projects favour households where private installation is more feasible (Evans et al., 2020; Mansour and Esouku, 2017).

Recommendations for the design of shared toilets Post-COVID-19

Shared sanitation facilities play an instrumental role in the everyday lives of low-income citizens, either as an intermediary option until the supply of private household toilets is maximized, or as a service to fluctuating urban populations (SaniPath, 2016; Cardone et al., 2018; Lutalo, 2018). Planners must improve the facilities in dense informal settlements, while simultaneously progressing service levels in more developed areas.

Accra's sanitation facilities have been a long-standing concern, even before the pandemic. For this section, we analysed literature about COVID-19 and shared toilets in Accra, to deduce recommendations. The preceding discussion seeks to outline proposals for improving such environments, as a direct result of the current global health crisis.

Hand Hygiene

Handwashing is a highly effective physical intervention of respiratory diseases such as COVID-19 (WHO, 2020; UNICEF, 2020). In high-density settings with limited WASH services, it is especially vital to prioritize handwashing in the movement between the private and public domain (WHO, 2020). In the long term, handwashing appliances must be provided in all shared sanitation facilities, and mobile handwashing stations with soap distribution in informal settlements. Improved water sources, e.g., piped water, boreholes and rainwater, are protected from faecal contamination and should be prioritized for handwashing (WHO, 2020). Ash, as an alternative to soap or alcohol-based hand-rub, can inactivate pathogens by raising pH levels (WHO, 2020). Lastly, washing with water alone can reduce faecal contamination, albeit with lower effectiveness (WHO, 2020). The drying of hands is just as important to prevent formic transmission (WHO, 2020).

Inclusive Design

Gender - and age-inclusive design considerations ascertain to adequately distanced male and female quarters; and robust, lockable structures and cubicle doors. They require well-lit entrances and walkways that promote informal surveillance; and access to washing appliances, hooks or ledges for changing and menstrual hygiene management (WSUP, 2018). Higher levels of provision for female users can advance employment, health, education, recreation and political involvement (WSUP, 2018).

Shared toilets should meet caregiving requirements, typically by women, whilst encouraging men in sharing these responsibilities (WSUP, 2018). This includes a cubicle spacious enough for a user and caregiver, child-friendly or babychanging fittings; or clothes-washing facilities to alleviate water insecurity (WSUP, 2018).

Limiting Contamination

Wherever applicable, the design of appliances and fixtures should limit cross-contamination, even beyond COVID-19. Foot-operated doors and locks should be considered, along with taps operated by foot pumps or long handles that use the arm or elbow (UNICEF 2020).

Improving the Sanitation Value Chain

Safe management of excreta throughout the entire sanitation chain is ever more critical (WHO, 2020). Data from 2010 shows that only 7% of Accra’s excrement was safely managed (Mansour and Esseku, 2013). Previously mentioned studies on environmental faecal contamination, compounded with COVID-19, highlight the public health risks in the poor faecal sludge management in Ghana.

Ghana should enforce the elimination of uncontained sanitation technologies and exposed drains to reduce the risk of storm floods and environmental faecal contamination. The government should also continue to incentivize private businesses that arrange collection, treatment, and recycling of faecal sludge (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019). Compost, irrigation water, and energy could be generated from treated wastewater while reducing pollution in the treatment cycle (Appiah-Effah et al., 2019). This can in turn sustain the operation of centralized sanitation infrastructure.

Setting a Benchmark for Monitoring

Clear determinants for the hardware, hygienic conditions and user behaviour can incentivise investment. Also, they can earn shared sanitation facilities an improved sanitation classification in monitoring protocols such as the JMP (Evans et al., 2018; Simiyu et al., 2017). The following example adapts Common-pool Resource (CPR) management principles for community toilets (Simiyu et al., 2017).

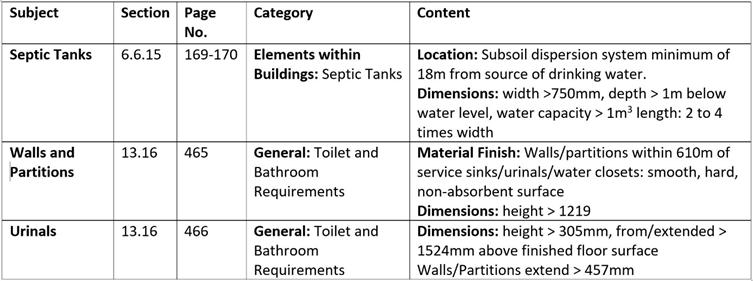

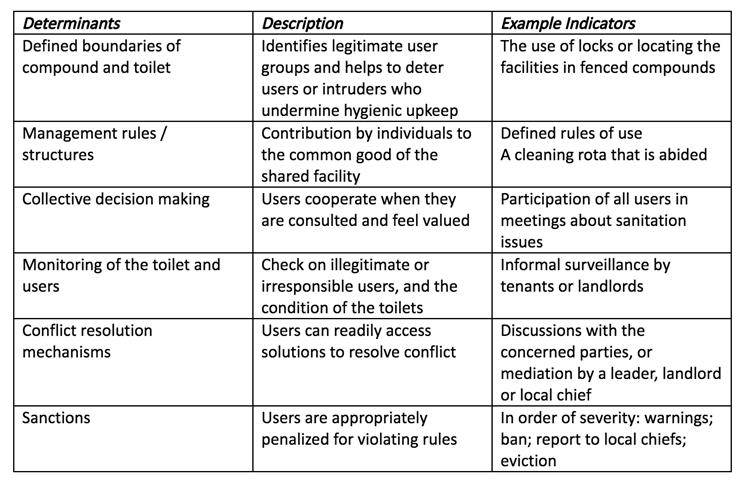

Table 3. Determinants to monitor the quality of shared toilets based on Common-pool Resource (CPR) management principles (Source: [Adapted from] Simiyu et al., 2017).

Conclusion

To summarise, our findings show that a range of factors contribute to the lack of toilet facilities and improper hygiene practices within Accra, Ghana. Due to the lack of provision of sanitation facilities, high costs, accessibility, maintenance, and safety issues, many abandon proper hygiene practices and resort to open defecation. Perception and awareness contribute to existing poor conditions, which are currently magnified due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the time of conducting this review, no studies have explored the impact of COVID-19 on shared sanitation in Accra, specifically. Nevertheless, recommendations have been made in response to these findings and the current pandemic to improve shared sanitation facilities and sanitation practices holistically. It is imperative that the government accelerate investments in centralised water and sanitation infrastructure, including water treatment facilities and faecal sludge plants, and regularly update planning policies as rapid urbanization continues to unfold. Effectively managing human excreta and wastewater can provide opportunities for composting, irrigation, and energy generation; all long-term benefits of a successful and considered value supply chain.

Other recommendations include reducing the spread of the virus through additional provisions for handwashing facilities, touchless appliances, improved technical training and maintenance. Usage can be improved by bettering maintenance, safety, inclusivity, accessibility and by employing contained facilities such as KVIP latrines.

Sanitation in Ghana will significantly improve if pragmatic steps are taken to implement the recommendations we have put forward. Nonetheless, they could be further examined by future research pertaining to COVID-19 transmission in such environments.

References

Ablo, A. D., Yekple, E. E. (2018) 'Urban water stress and poor sanitation in Ghana: perception and experiences of residents in the Ashaiman Municipality.' GeoJournal, 83:3, pp. 583-594. [online][Accessed on 7th November 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9787-6

Adams, E. A., Boateng, G. O., and Amoyaw, J. A. (2016) 'Socioeconomic and Demographic Predictors of Potable Water and Sanitation Access in Ghana.' Soc Indic Res, 126, 2016, pp. 673-687. [online][Accessed on 28th October 2020] https://doi-org.manchester.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0912-y

Adubofour, K., Obiri-Danso, K. and Quansah, C. (2013) 'Sanitation survey of two urban slum Muslim communities in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana.' Environment and Urbanization, 2:1, pp. 189-207. [online][Accessed on 17th Jan 2021] https:// journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956247812468255

Afriye, D., Asare, G., Amponsah, S., Godman, B. (2020) 'COVID-19 Pandemic in resource-poor countries: challenges, experiences and opportunities in Ghana.' The Journal of infection in Developing countries, 14:8, pp. 838-843. [online][Accessed on 07th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.12909

Akpakli, D. E., Manyeh, A. K., Akpakli, J. K., Kukula, V. and Gyapong, M. (2018) 'Determinants of access to improved sanitation facilities in rural districts of southern Ghana: evidence from Dodowa Health and Demographic Surveillance Site.' BMC research notes, 11:1, pp. 473-473. [online][Accessed on 07th November 2020] DOI: 10.1186/s13104-018-3572-6

Amoako, C., Cobbinah, P. B. (2011) 'SLUM IMPROVEMENT IN THE KUMASI METROPOLIS, GHANA: A REVIEW OF APPROACHES AND RESULTS.' Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13, pp. 150-170. [online][Accessed on 27th December 2020] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232957170_Slum_ improvement_in_the_Kumasi_metropolis_Ghana_A_review_of_approaches_and_ results?enrichId=rgreq-c9607343926772852554802e66110011-XXX&enrichSource =Y292ZXJQYWdlOzIzMjk1NzE3MDtBUzo0MjcxOTgzOTA3NzE3MTRAMTQ3ODg2M zQ0MTkwNA%3D%3D&el=1_x_2&_esc=publicationCoverPdf

Antwi-Agyei, P., Monney, I., Dwumfour-Asare, B., Cavill, S. (2019) 'Toilets for tenants: a cooperative approach to sanitation bye-law enforcement in Ga West, Accra.' Environment and Urbanization, 31:1, pp. 293-308. [online][Accessed on 7th November 2020] DOI:10.1177/0956247818800654

Antwi-Agyei, P., Dwumfour-Asare, B., Adjei, K. A., Kweyu, R., Simiyu, S. (2020) 'Understanding the Barriers and Opportunities for Effective Management of Shared Sanitation in Low-Income Settlements - The Case of Kumasi, Ghana.' International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17:12, p. 4528. [online][Accessed on 28th October 2020] DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17124528 overview.' Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 1, 9:3, pp. 397–415. [online][Accessed on 8th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.2166/ washdev.2019.031

Awuah, E., Nyarko, K. B., Owusu, P. A. (2009) 'Water and sanitation in Ghana.' Desalination, 248:1, pp.460-467. [online][Accessed on 14th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.088

Awunyo-Akaba, Y., Awunyo-Akaba, J., Gyapong, M., Senah, K., Konradsen, F., Rheinländer, T. (2016) 'Sanitation investments in Ghana: An ethnographic investigation of the role of tenure security, land ownership and livelihoods.' BMC Public Health, 16:594, pp. 1-12. [online] [ Accessed on 4th December 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3283-7 Ablo, A. D., Yekple, E. E. (2018) 'Urban water stress and poor sanitation in Ghana: perception and experiences of residents in the Ashaiman Municipality.' GeoJournal, 83:3, pp. 583-594. [online][Accessed on 7thNovember 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9787-6

Adams, E. A., Boateng, G. O., and Amoyaw, J. A. (2016) 'Socioeconomic and Demographic Predictors of Potable Water and Sanitation Access in Ghana.' Soc Indic Res, 126, 2016, pp. 673-687. [online][Accessed on 28thOctober 2020] https:// doi-org.manchester.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0912-y

Adubofour, K., Obiri-Danso, K. and Quansah, C. (2013) 'Sanitation survey of two urban slum Muslim communities in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana.' Environment and Urbanization, 2:1, pp. 189-207.[online][Accessed on 17th Jan 2021] https:// journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956247812468255

Afriye, D., Asare, G., Amponsah, S., Godman, B. (2020) 'COVID-19 Pandemic in resource-poor countries:challenges, experiences and opportunities in Ghana.' The Journal of infection in Developing countries, 14:8, pp. 838-843. [online][Accessed on 07th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.12909

Akpakli, D. E., Manyeh, A. K., Akpakli, J. K., Kukula, V. and Gyapong, M. (2018) 'Determinants of access to improved sanitation facilities in rural districts of southern Ghana: evidence from Dodowa Health and Demographic Surveillance Site.' BMC research notes, 11:1, pp. 473-473. [online][Accessed on 07thNovember 2020] DOI: 10.1186/s13104-018-3572-6

Amoako, C., Cobbinah, P. B. (2011) 'SLUM IMPROVEMENT IN THE KUMASI METROPOLIS, GHANA: A REVIEW OF APPROACHES AND RESULTS.' Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13, pp. 150-170. [online][Accessedon 27th December 2020]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232957170_Slum_ improvement_in_the_Kumasi_metropolis_Ghana_A_review_of_approaches_and_ results?enrichId=rgreq-c9607343926772852554802e66110011-XXX&enrichSource =Y292ZXJQYWdlOzIzMjk1NzE3MDtBUzo0MjcxOTgzOTA3NzE3MTRAMTQ3ODg2M zQ0MTkwNA%3D%3D&el=1_x_2&_esc=publicationCoverPdf

Antwi-Agyei, P., Monney, I., Dwumfour-Asare, B., Cavill, S. (2019) 'Toilets for tenants: a cooperative approach to sanitation bye-law enforcement in Ga West, Accra.' Environment and Urbanization, 31:1, pp. 293-308.[online][Accessed on 7th November 2020] DOI:10.1177/0956247818800654

Antwi-Agyei, P., Dwumfour-Asare, B., Adjei, K. A., Kweyu, R., Simiyu, S. (2020) 'Understanding the Barriers and Opportunities for Effective Management of Shared Sanitation in Low-Income Settlements - The Case of Kumasi, Ghana.' International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17:12, p. 4528. [online][Accessed on 28th October 2020] DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17124528

Appiah-Effah, E., Duku, G. A., Azangbego, N. Y., Aggrey, R. K. A., GyapongKorsah, B., Nyarko, K. B. (2019) 'Ghana's post-MDGs sanitation situation: an overview.' Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 1, 9:3, pp. 397–415. [online][Accessed on 8th November 2020]https://doi.org/10.2166/ washdev.2019.031

Awuah, E., Nyarko, K. B., Owusu, P. A. (2009) 'Water and sanitation in Ghana.' Desalination, 248:1, pp.460-467.[online][Accessed on 14th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.088

Awunyo-Akaba, Y., Awunyo-Akaba, J., Gyapong, M., Senah, K., Konradsen, F., Rheinländer, T. (2016) 'Sanitation investments in Ghana: An ethnographic investigation of the role of tenure security, land ownership and livelihoods.' BMC Public Health, 16:594, pp. 1-12. [online] [ Accessed on 4th December 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3283-7

Ayee, J., Crook, R. (2003) ‘Toilet wars: urban sanitatio1n services and the politics of public-private partnerships in Ghana.’ Insitute of Development Studies, 213:1, pp. 1-40 [online] [Accessed on 3rd November 2020] https://assets.publishing.service. gov.uk/media/57a08d0be5274a31e00015e0/wp213.pdf

Ayisi-Boateng, N. K., Egblewogbe, D., Owusu-Antwi, R., Essuman, A., Spangenberg, K. (2020) 'Exploring the illness experiences amongst families living with 2019 coronavirus disease in Ghana: Three case reports.'Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med, 12:1, pp. 1-3. [online] [Accessed on 3rd November 2020] Exploring the illness experiences amongst families living with 2019 coronavirus disease in Ghana: Three case reports | Ayisi-Boateng | African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine (phcfm.org)

Berendes, D. M., Kirby, A. E., Clennon, J. A., Agbemabiese, C., et. al. (2018) 'Urban sanitation coverage and environmental fecal contamination: Links between the household and public environments of Accra,Ghana.' PLoS ONE, 13:7, pp. 1-19. [Online] Accessed on 3rd November 2020] https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199304

Berendes, D. M., de Mondesert, L., Kirby, A. E., et al. (2020) ‘Variation in E. coli concentrations in open drains across neighborhoods in Accra, Ghana: The influence of onsite sanitation coverage and interconnectedness of urban environments.’ Int J Hyg Environ Health, 224:1, pp. 1-19. [Online][Accessed on 24 October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.113433.

Bhatta, A., Arora, P. and Prajapati, S. K. (2020) ‘Occurrence, fates and potential treatment approaches for removal of viruses from wastewater: A review with emphasis on SARS-CoV-2’. Elsevier, 8:5, pp. 1-11.[Online] [[Accessed on 20 October 2020] https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jece.2020.104429

Boadi, K. O. and Kuitunen, M. (2005) 'Environment, wealth, inequality and the burden of disease in the Accra metropolitan area, Ghana.' International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 15(3), pp. 193-206.[Online] [Accessed on 20 October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/09603120500105935

Boot, N. and Scott, R. (2008) 'Faecal sludge management in Accra, Ghana: strengthening links in the chain.'Access to Sanitation and Safe Water: Global Partnerships and Local Actions, pp. 99-107. [online] [Accessed on 21 October 2020] https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/33/Boot_NLD.pdf

Cardone, R., Schrecongost, A. and Gilsdorf, R. (2018) 'Shared and Public Toilets: Championing Delivery Models that Work.' New Dehli, India: The World Bank Group, pp. 1-65. [Online] [Accessed on 18th December 2020] https:// openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30296/W18035.pdf

Corburn, J., Vlahov, D., Mberu, B., et al. (2020) 'Slum Health: Arresting COVID-19 and improving Wellbeing in Urban Informal Settlements.' J Urban Health, 97, pp. 348-357. [Online] [Accessed on 30 September 2020]. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11524-020-00438-6

CHF International. (2010) 'Guidelines for usage and maintenance of KVIP Latrines.' [Online] [Accessed on 9 November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14677679.2006.00313.x

Crook, R., Ayee, J. (2006) 'Urban Service Partnerships, ‘Street-Level Bureaucrats’ and Environmental Sanitation in Kumasi and Accra, Ghana: Coping with Organisational Change in the Public Bureaucracy.'Development Policy Review, 24:1, pp. 51-73. [Online] [Accessed on 9 November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467-7679.2006.00313.x

CSO 2, 2015. Water Supply and Sanitation in Ghana: Turning Finance Into Services for 2015 and Beyond.

Daniel Armah-Attoh, J. A. S., and Edem Selormey. (2020) 'Ghanaians’ acceptance of security-related restrictions faces test with COVID-19 lockdown.' [Online] [Accessed on 9 November 2020]https://newsghana.com.gh/wp-content/ uploads/2020/03/COVID-lockdown-will-test-Ghanaian-acceptance-of-restrictionson-movement-Afrobarometer-30march20.pdf Drafor, I., Jones, H. (2008) ‘Access to water and sanitation in Ghana for persons with disabilities: findings of a KAP survey.’ Loughborough University. Conference contribution. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/29842

Drechsel, P., Scott, A. C., Raschid-Sally, L., Redwood, M., Bahri, A. (2010) Wastewater Irrigation and Health: Assessing and Mitigating Risk in Low-Income Countries. London, Routledge.

Dumpert, J. (2008) 'Performance evaluation of VIP latrines in the Upper West Region of Ghana.' [Online] [Accessed on 26 December 2020] https://core.ac.uk/ download/pdf/151507551.pdf

Durrizo, K., Asiedu, E., Van der Merwe, A., Van Niekerk, A., and Gunther, I. (2020) 'Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in poor urban neighbourhoods: The case of Accra and Johannesburg.' Elsevier. [Online] [Accessed on 3 November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105175

Ekumah, B., Armah, F. A., Yawson, D. O., Quansah, et al. (2020) 'Disparate on-site access to water, sanitation, and food storage heighten the risk of COVID-19 spread in Sub-Saharan Africa.' Environ Res, 189, Oct, 2020/09/28, p. 1-12. [Online] [Accessed on 16 Dec 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.envres.2020.109936

Evans, B., Hueso, A., Johnston, R., Norman, G., Pérez, E., Slaymaker, T., Trémolet, S. (2017) Limited services? The role of shared sanitation in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Journal of Water, S anitation and Hygiene for Development, 7:3, 349–351. [Online] [Accessed on 12 Dec 2020] https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2017.023

Fiasorgbor, D. (2013) 'Water and sanitation situation in Nima and Teshie, Greater Accra Region of Ghana.' Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Sciences, 5, pp. 23-28. [Online] [Accessed on 11 November 2020] DOI: 10.5897/JTEHS12.054

Fischer, C., Amankwaa, G. (2020) 'Exploring the correlation between COVID-19 fatalities and poor WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) services.' medRxiv, pp. 1-9. [Online] [Accessed on 11 December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.0 8.20125864

Fobil, J., N., Armah, N, A., Hogarh, J, N., Carboo, D. (2008) 'The influence of institutions and organizations on urban waste collection systems: An analysis of waste collection system in Accra, Ghana (1985–2000).' Journal of Environmental Management, 86:1, January 2008, pp. 262-271. [Online] [Accessed on 06 Dec 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.12.038

Freeman, F. (2010) 'Ghana: The Waste Land.' World Policy Journal, 27:2, pp. 47-53. [online] [Accessed on 11th January] https://doi.org/10.1162/wopj.2010.27.2.47

Ghana Standards Authority. (2018) GS 1207:2018 Ghana Building Code: Building and Construction. Accra. ICC.

Ghana, A. I. (2018) 'Effects of State facilitated forced evictions on the structure of poverty among slum dwellers within the capital, Accra, Ghana for the visit of the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights to Ghana.' p. 531.

Ghana, W.A., 2005. ASSESSMENT OF NATIONAL SANITATION POLICIES-GHANA CASE. Final report (PDF). Available from URL: http://wedc. lboro. ac. uk/projects/ proj_ contents0/WEJEH, p.9.

Grieco, M. (2009) 'Living infrastructure: Replacing children's labour as a source of sanitation services in Ghana.' Desalination, 248:1, pp. 485-493. [Online] [Accessed on 10th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.092

Gyader, G. (2020) ‘Covid-19 in Africa: A Ghanaian Case.’ Italian Institute for International Political Studies. [Online] [Accessed on 9th November 2020] https:// www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/covid-19-africa-ghanaian-case-26459

Harter, M., Contzen, N., Inauen, J. (2019) 'The role of social identification for achieving an open-defecation free environment: A cluster-randomized, controlled trial of Community-Led Total Sanitation in Ghana.' Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66. [Online] [Accessed on 19th December 2020] https://doi-org. manchester.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101360

Hurd, J., Robb, K., Null, C., Peprah, D., Wellington, N., Yakubu, H., Moe, C. L. (2017) 'Behavioral influences on risk of exposure to faecal contamination in low-resource neighbourhoods in Accra, Ghana.' Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 7, pp. 300–311. [Online] [Accessed on 14th December 2020] https:// doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2017.128

Jenkins, M. W., Scott, B. (2007) 'Behavioural indicators of household decisionmaking and demand for sanitation and potential gains from social marketing in Ghana.' Social Science & Medicine, 64:12, pp. 2427-2442. [Online] [Accessed on 7th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.010

Kanhai, G., Agyei-Mensah, S., Mudu, P. (2019) 'Population awareness and attitudes toward waste related health risks in Accra, Ghana.' International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 24, pp. 1-17. [Online] [Accessed on 17th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2019.1680818

Keraita, B., Amoah, P. (2011) ‘Fecal exposure pathways in Accra: a literature review with specific focus on IWMIs work on wastewater irrigated agriculture’. Centre for Global Safe Water, Emory University,

Kiddy, J., Asamoah, B., Owusu, M., Zhen, J., Oduro, B., Abidemi, A., Gyasi, E. (2020) 'Global stability and cost-effectiveness analysis of COVID-19 considering the impact of the environment: using data from Ghana.' Chaos Solitons Fractals, 140:110103. [Online] [Accessed on 17thDecember 2020] DOI: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110103

Knott, S. (2020) 'COVID-19 Heralds Mass Clean-up in Ghanaian Capital.' VOA News. [Online][Accessed on 11th December 2020] https://www.ghanaiantimes. com.gh/investment-in-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-critical-amid-covid-19/

Kretchy, J., Dzodzomenyo, M., Ayi, I., Dwomoh, D, Agyabeng, J., Konradsen, F., Dalsgaard, A. (2020) 'Risk of faecal pollution among waste handlers in a resourcedeprived coastal peri-urban settlement in Southern Ghana.' PLoS ONE 15:10, e0239587. [Online] [Accessed on 11th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0239587

Mansour, G., Esseku, H. (2017) 'Situation analysis of the urban sanitation sector in Ghana.' WSUP, pp. 1-33. [online] [Accessed on 14th November 2020] https:// www.wsup.com/content/uploads/2017/09/Situation-analysis-of-the-urbansanitation-sector-in-Ghana.pdf

Mackenzie, J. S., & Smith, D. W. (2020) COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don’t. Microbiology Australia, MA20013. [online] [Accessed on 14th January 2021] https://doi.org/10.1071/MA20013

Mazeau, A., Tumwebaze, I. K., LÜThi, C. and Sansom, K. (2013) 'Inclusion of shared sanitation in urban sanitation coverage? Evidence from Ghana and Uganda.' Waterlines, 32:4, pp. 334-348. [online] [Accessed on 14th November 2020] DOI: 10.3362/1756-3488.2013.034

Mensah, I. (2007) 'Environmental management and sustainable tourism development: The case of hotels in Greater Accra Region (GAR) of Ghana.' Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 6(1), 2007/01/01, pp. 15-22. [Online] [Accessed on 12th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.rlp.5100039

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (2001) Environmental Sanitation Policy. Accra: Government of Ghana. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/gha170015.pdf

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. (2010) Environmental Sanitation Policy. Accra: Government of Ghana. [Online] [Accessed on 23rd December 2020] https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/MLGRD-2010Environmental.pdf

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD). (2017) Construction of Institutional Sanitation Facilities. Accra: SAL Consult Ltd. Accra: Government of Ghana. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] http:// documents1.worldbank.org/curated/zh/916581491560004282/SFG3246-V1-EAP119063-Box402900B-PUBLIC-Disclosed-4-5-2017.doc

Ministry of Water Resources Housing. (2007) National Water Policy. Accra: Government of Ghana. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] https://www. gwcl.com.gh/national_water_policy.pdf

Monney, I., Buamah, R., Odai, S., Awuah, E. and Nyenje, P. (2013) 'Evaluating access to potable water and basic sanitation in Ghana's largest urban slum community: Old Fadama, Accra.' Journal of Environment and Earth Science, 3:11, pp. 72-79. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257351347_Evaluating_access_ to_potable_water_and_basic_sanitation_in_Ghana%27s_largest_urban_slum_ community_Old_Fadama_Accra

Murray, A., Drechsel, P. (2011) 'Why do some wastewater treatment facilities work when the majority fail? Case study from the sanitation sector in Ghana.' Waterlines, 30:2, pp. 135-149. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] DOI: 10.3362/1756-3488.2011.015

Obeng, P., Keraita, B., Oduro-Kwarteng, S., Bregnhøj, H., Abaidoo, R., Awuah, E., Konradsen, F. (2015) 'Usage and Barriers to Use of Latrines in a Ghanaian Peri-Urban Community.' Environ: Process, 2, pp. 261–274. [Online] [Accessed on 12th November 2020] https://iwaponline.com/washdev/article-pdf/doi/10.2166/ washdev.2019.098/564705/washdev2019098.pdf

Obeng, P., Oduro-Kwarteng, S., Keraita, B., Bregnhoj, H., Abaidoo, R., Awuah, E., Konradsen, F. (2019) 'Redesigning the ventilated improved pit latrine for use in built-up low-income settings.' Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 9, 02/25. [Online] [Accessed on 16th December 2020] https://doi. org/10.2166/washdev.2019.098

Odonkor, S. T. and Adom, P. K. (2020) 'Environment and health nexus in Ghana: A study on perceived relationship and willingness-to-participate (WTP) in environmental policy design.' Elsevier, 34(100689), pp. 1-12. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100689

Oteng-Ababio, M. (2014) 'Rethinking waste as a resource: insights from a lowincome community in Accra, Ghana.' City, Territory and Architecture, 1:1, p. 10. Owusu, G. (2010) 'Social effects of poor sanitation and waste management on poor urban communities: a neighborhood-specific study of Sabon Zongo, Accra.' Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 3:2, pp. 145-160. [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2010.502001

Peprah, D., Baker, K., Moe, C., Robb, K., Wellington, N., Yakubu, H. and Null, C. (2015) 'Public toilets and their customers in low-income Accra, Ghana.' SAGE Journals, 27:2, pp. 589-604. [Online] [Accessed on 18th November 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1177%2F0956247815595918

Plageman, N., Hart, J.A, and Yeaboh, T. (2020) 'Urban Planning Needs to Look Back First: Three Cities in Ghana Show Why [analysis].' The Conversation. [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://theconversation.com/urban-planningneeds-to-look-back-first-three-cities-in-ghana-show-why-144913

Quaresima, V., Naldini, M. M. and Cirillo, D. M. (2020) 'The prospects for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Africa.' EMBO Mol Med, 12:6. [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202012488

Ghana Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resource (2020) GAMA Sanitation and Water Project (Additional Financing) : Final Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF). Accra: Government of Ghana

Rheinländer, T., Konradsen, F., Keraita, B., Apoya, P., Gyapong, M. (2015) 'Redefining Shared Sanitation.' Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93:7, pp. 509-510. [Online] [Accessed on 9th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.2471/ BLT.14.144980

Ritter, R., et. al. (2018) 'Within-Compound Versus Public Latrine Access and Child Feces Disposal Practices in Low-Income Neighbourhoods of Accra, Ghana.' American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 98:5, pp. 1250-1259. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0654

Robb, K., Null, C., Teunis, P., Yakubu, H., Armah, G., Moe, C. (2017) 'Assessment of Fecal Exposure Pathways in Low-Income Urban Neighbourhoods in Accra, Ghana: Rationale, Design, Methods, and Key Findings of the SaniPath Study.' The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97:4, pp. 1020-1032. [Online] [Accessed on 16th October 2020] doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0508

Ryan, B., A. Mara, D, D. (1983) 'Ventilated Improved Pit Latrines: Vent Pipe Design Guidelines.'

Saba, C. K. S. (2020) COVID-19: Implications for food water hygiene sanitation and environmental safety in Africa-A case study in Ghana. Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, University for Development Studies. [Online] [Accessed on 16th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202005.0369. v1

Safro, A., Karuppannan, S. (2020) 'Application of Geospatial Technologies in the COVID-19 Fight of Ghana.' Transactions of the Inidian National Academy of Engineering, 5, pp. 193-204. [Online] [Accessed on 28th December 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1007/s41403-020-00145-3

Sagoe, G., Danquah, F. S., Amofa-Sarkodie E. S., Appiah-Effah, E., Ekuma, E., Mensah, E. K., Karikari, K. S. (2019) 'GIS-aided optimisation of faecal sludge management in developing countries: the case of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana.' Elsevier, 5:9. [Online] [Accessed on 28th December 2020] https://doi. org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02505

SaniPath. (2016) Should Public Toilets Be Part of Urban Sanitation Solutions for Families Living in Slums? [Online] [Accessed on 28th December 2020] https:// sanitationupdates.blog/2016/04/21/policy-note-should-public-toilets-be-part-ofurban-sanitation-solutions-for-poor-families-living-in-slums/

Silver, J. (2014) 'Incremental infrastructures: material improvisation and social collaboration across post-colonial Accra.' Urban Geography, 35:6, pp. 788-804 [Online] [Accessed on 1st January 2021] https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014 .933605

Simiyu, S., Swilling, M., Cairncross, S., and Rheingans, R. (2017) 'Deterrminants of quality of shared sanitation facilties in informal settlements: case study of Kisumu, Kenya.' BMC Public Health, 17:68. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] DOI 10.1186/s12889-016-4009-6

Smiley, S. L., Agbemor, B. D., Adams, E. A., and Tutu, R. (2020) 'COVID-19 and water access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Ghana’s free water directive may not benefit water insecure households.' African Geographical Review. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2020.1810083

Smith, F. (2020) 'Accra Metropolitan Assembly prosecute 2 for not wearing face masks in public’.' Joy Online, pp. 1-7. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://www.myjoyonline.com/accra-metropolitan-assembly-prosecute-2-for-notwearing-face-masks-in-public/

The World Bank. (2020) Ghana to Provide 550,000 People with Improved Water and Sanitation Services’. [Online] [Accessed on 7th November 2020] https://www. worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/09/22/ghana-to-provide-550000people-with-improved-water-and-sanitation-services

Thrift, C., 2007. Sanitation policy in Ghana: Key factors and the potential for ecological sanitation solutions. Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/ Thrift-2007-Sanitation.pdf

UNICEF. (2020) 'Handwashing Stations and Supplies for the COVID-19 Response.' [Online] [Accessed on 12 Dec 2020 https://www.unicef.org/documents/ handwashing-stations-and-supplies-covid-19-response

United National Human Settlements Programme. (2009) Ghana: Accra Urban Profile. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

United Nations. (2015) General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Online] [Accessed on 10th December] http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. United Nations. (2015) 'Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.'

Van der Geest, S., Obirih-Opareh, N. (2002) 'Getting out of the shit: toilets and the daily failure of governance in Ghana.' Bulletin de L'APAD, pp. 1-15. [Online] [Accessed on 8th December 2020] https://doi.org/10.4000/apad.150

Van der geest, S. (2002) 'The night-soil collector: Bucket latrines in Ghana.' Postcolonial Studies, 5:2, pp. 197-206. [online] [Accessed on 7th November 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/1368879022000021092

Van der Geest, S. (2013) 'Public toilets and privacy in Ghana.' Ghana Study Council Newsletter, 12, pp. 6-8. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254783200_Public_toilets_and_privacy_ in_Ghana

Wallace, L. J., Nouvet, E., Bortolussi, R., Arthur, J. A., Amporfu, E., Arthur, E., Barimah, K. B., Bitouga, B. A., et al. (2020) 'COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: impacts on vulnerable populations and sustaining home-grown solutions.' Can J Public Health, 111:5, pp. 649-653. [Online] [Accessed on 12th December 2020] https://doi. org/10.17269/s41997-020-00399-y

Water, Engineering and Development Centre. (2005) 'National Sanitation Policy in Ghana: A case for improved co-ordination?', pp. 1-4. [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/books/Assessing_ Sanitation_Policy_-_BN-Ghana.pdf

Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor. (2018) High Quality Shared Sanitation: how can we define that? https://www.wsup.com/content/uploads/2018/08/PBrief_ Shared-sanitation-project-introduction_WEB.pdf

Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (2018) 'Female-friendly public and community toilets: a guide for planners and decision makers.' [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/femalefriendly-public-and-community-toilets-a-guide-for-planners-and-decision-makers

WaterAid. (2018) 'Technical guidelines for construction of institutional and public toilets - Annexes.' (1) pp. 1-66.

Word Health Organization. (2015) Ghana: Sanitation, drinking water and hygiene status overview. Switzerland: World Health Organisation UN Water. [Online] [Accessed on 16th November 2020] https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/ glaas/2014/ghana-22-oct.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organization, 2020. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for the COVID-19 virus: interim guidance, 23 April 2020 (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/IPC_WASH/2020.3). World Health Organization.

Word Health Organization. (2018) 'Guidelines on sanitation and health.'

COVID-19 Transmission Pathways References:

Adelodun, B., Ajibade, F., Ibrahim, R., Bakare, H. and Choi, K. (2020) ‘Snowballing Transmission Of COVID-19 (SARS-Cov-2) Through Wastewater; Any Sustainable Preventative Measures to Curtail the Scourge in Low-Income Countries.’ Sci Total Environ, pp.1-10. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] https://doi. org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140680

Afriyie, D., Asare, G., Amponsah, S., Godman, B. (2020) ‘COVID-19 pandemic in resource-poor countries: challenges, experiences and opportunities in Ghana.’ The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 14(8), pp. 838-843. [Online] [Accessed on 9th October 2020] https://jidc.org/index.php/journal/article/view/12909 Anderson, E., Turnham, P., Griffin, J., Clarke, C. (2020) ‘Consideration of the Aerosol Transmission for COVID-19 and Public Health.’ Wiley, 40(5), pp. 902-907. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13500

Bhatt, A., Arora, P., and Prajapati, S. (2020) ‘Occurrence, fates and potential treatment approaches for removal of viruses from wastewater: A review with emphasis on SARS-CoV-2.’ Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 8, 104429. [Online] [Accessed 10th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.104429 Covaci, A. (2020) ‘How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised.’ Environment International, 142. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412020317876#bi005 Dasheng, L., Thompson, J.R., Carducci, A., and Xuejun, B. (2020) ‘Potential secondary transmission via wastewater.’ The Science of the Total Environment, 749, 142358. [Online] [Accessed 10 Oct 2020] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scitotenv.2020.142358

Dietz, L., Horve, P., Coil, D., Fretz, M., Eisen, J., Wymelenberg, K. (2020) ‘2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Built Environment Considerations to Reduce Transmission.’ American Society for Microbiology Journals, pp.1-15. [Online] [Accessed 10 October 2020] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00375-20

Durizzo, K., Asiedu, E., Merwe, A., Niekerk, A., Gunther, I. (2020) ‘Managing The COVID-19 Pandemic in Poor Urban Neighborhoods: The Case of Accra And Johannesburg.’ Elsevier, pp. 1-14. [Online] [Accessed 10th October 2020] doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105175

Guo, Y., Cao, Q., Hong, Z. et al. (2020) ‘The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak – an update on the status.’ Military Med Res7, 11. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] doi: https://doi. org/10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0

He, X., Lau, E.H.Y., Wu, P. et al. (2020) ‘Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID- 19.’ Nat Med, 26, pp. 672–675. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 Jayaweera, M., Perera, H., Gunawardana, H. et al. (2020) ‘Transmission of COVID-19 virus by droplets and erosols: A critical review on the unresolved dichotomy.’ Environmental Research, Vol188, pp. 1-19.[Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109819

Nomoto, H., Ishikane, M., Katagiri, D., Kinoshita, N. (2020) ‘Cautious handling of urine from moderate to severe COVID-19 patients.’ Elsevier, 48(8), pp. 969–971. [Online] [Accessed on 10th October 2020] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC7266575/#bib0003

Ozyigit, A. (2020) ‘Understanding Covid-19 transmission: The effect of temperature and health behaviour on transmission rates.’ Department of Healthcare Management, University of Mediterranean Karpasia. [Online] [Accessed 18th Oct 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2020.07.001

Safro, A., Karuppannan, S. (2020) ‘Application of Geospatial Technologies in the COVID-19 Fight of Ghana.’ Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering, 5, pp.193-204. [Online] [Accessed 9th October 2020] https://link. springer.com/article/10.1007/s41403-020-00145-3

Saks, A., Ajisola, M., Azeem, K., et al. (2020) ‘Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre- COVID and COVID-19 lockdown stakeholder engagements.’ BMJ Global Health, 5, e003042. [Online] [Accessed 9th October 2020] DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003042

Schwartz, D. A. (2020) ‘An Analysis of 38 Pregnant Women With COVID-19, Their Newborn Infants, and Maternal-Fetal Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Maternal Coronavirus Infections and Pregnancy Outcomes.’ Arch Pathol Lab Med, 144 (7), pp. 799–805. [Online] [Accessed 9th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.20200901-SA

Shereen, M., Khan S., Kazmi, A. et al. (2020) ‘COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses.’ Journal of Advanced Research, Vol. 24. [Online] [Accessed 9th October 2020] DOI: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005

Sun J, Zhu A, Li H., Zheng, K. et. al. (2020) ‘Isolation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 from urine of a COVID-19 patient.’ Emerge Microbes Infec, 9:991–993, pp. 1-4. [Online] [Accessed 11th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1760144

Tian, Y., Rong, L., He, Y. and Nian, W., 2020. ‘Review Article: Gastrointestinal Features In COVID-19 And the Possibility of Faecal Transmission.' Beijing: Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, pp.1-10. [Online] [Accessed 11 October 2020] https:// doi.org/10.1111/apt.15731

Van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T., Morris, D.H., Holbrook, M.G, et al. (2020) ‘Aerosol and surface stability of HCov-19 (SARS-CoV-2) compared to SARS- CoV-1.’ N Engl J Med, 382:1564-1567, pp. 1-4. [Online] [Accessed 10 Oct 2020] https://www.nejm. org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmc2004973

Yun-yun, L., Ji-Xiang, W., and Chen, X. (2020) ‘Can a toilet Promote virus transmission? From a fluid dynamics perspective.’ Physics of Fluids 32, 065107, pp. 1-15. [Online] [Accessed 10 Oct 2020] https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0013318

Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R. (2020) ‘Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens.’ JAMA, 323, pp.1843–1844. [Online] [Accessed 11th October 2020] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762997

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A.C., Peacock, S.J., Prescott, H.C. (2020) ‘Pathophysiology Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review.’ JAMA, 324(8), pp. 782–793. [Online] [Accessed 11th October 2020] DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.12839