Microcomputed tomography of the stapes: Wide-ranging dimensions An absence of cilia outer microtubules, an etiology not previously recognized in bilateral mucocele

Computational analysis of swallowing mechanics after surgery for obstructive sleep apnea

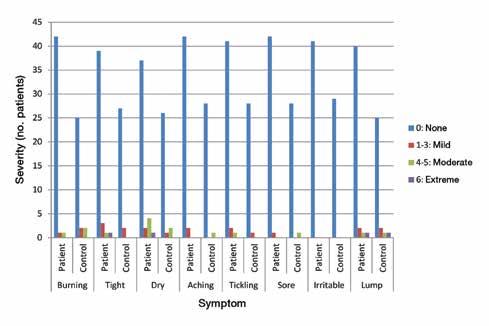

Vocal tract symptoms: Severity and frequency in patients on statins

www.entjournal.com A Vendome Publication APRIL/MAY 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 4-5

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Editor-in-Chief

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Professor and Chairman, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Senior Associate Dean for Clinical Academic Specialties, Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, PA

Jean Abitbol, MD

Jason L. Acevedo, MD, MAJ, MC, USA

Jack B. Anon, MD

Gregorio Babighian, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Bruce Benjamin, MD

Gerald S. Berke, MD

Michael J. Brenner, MD

Kenneth H. Brookler, MD

Karen H. Calhoun, MD

Steven B. Cannady, MD

Ricardo Carrau, MD

Swapna Chandran, MD

Chien Chen, MD

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Nicolle T. Clements, MS

Daniel H. Coelho, MD, FACS

David M. Cognetti, MD

Maura Cosetti, MD

James V. Crawford, MD

David H. Darrow, MD, DDS

Rima Abraham DeFatta, MD

Robert J. DeFatta, MD, PhD

Hamilton Dixon, MD

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Mainak Dutta, MS, FACS

Russell A. Faust, PhD, MD

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Charles N. Ford, MD

Paul Frake, MD

Marvin P. Fried, MD

Richard R. Gacek, MD

Andrea Gallo, MD

Frank Gannon, MD

Emilio Garcia-Ibanez, MD

Soha Ghossani, MD

William P. R. Gibson, MD

David Goldenberg, MD

Jerome C. Goldstein, MD

Richard L. Goode, MD

Samuel Gubbels, MD

Reena Gupta, MD

Joseph Haddad Jr., MD

Missak Haigentz, MD

Christopher J. Hartnick, MD

Mary Hawkshaw, RN, BSN, CORLN

Garett D. Herzon, MD

Thomas Higgins, MD, MSPH

Jun Steve Hou, MD

John W. House, MD

Glenn Isaacson, MD

Steven F. Isenberg, MD

Stephanie A. Joe, MD

Shruti S. Joglekar, MBBS

Raleigh O. Jones, Jr., MD

Petros D. Karkos, MD, AFRCS, PhD, MPhil

David Kennedy, MD

Seungwon Kim, MD

Robert Koenigsberg, DO

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Jamie A. Koufman, MD

Stilianos E. Kountakis, MD, PhD

John Krouse, MD

Ronald B. Kuppersmith, MD, MBA, FACS

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Robert S. Lebovics, MD, FACS

Keat-Jin Lee, MD

Donald A. Leopold, MD

Steve K. Lewis, BSc, MBBS, MRCS

Daqing Li, MD

Robert R. Lorenz, MD

John M. Luckhurst, MS, CCC-A

Valerie Lund, FRCS

Karen Lyons, MD

A.A.S. Rifat Mannan, MD

Richard Mattes, PhD

Brian McGovern, ScD

William A. McIntosh, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Oleg A. Melnikov, MD

Albert L. Merati, MD, FACS

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ron B. Mitchell, MD

Steven Ross Mobley, MD

Jaime Eaglin Moore, MD

Thomas Murry, PhD

Ashli K. O’Rourke, MD

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

J. David Osguthorpe, MD

Robert H. Ossoff, DMD, MD

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Michael M. Paparella, MD

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD

Arthur S. Patchefsky, MD

Meghan Pavlick, AuD

Spencer C. Payne, MD

Kevin D. Pereira, MD, MS (ORL)

Nicolay Popnikolov, MD, PhD

Didier Portmann, MD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Matthew J. Provenzano, MD

Hassan H. Ramadan, MD, FACS

Richard T. Ramsden, FRCS

Gabor Repassy, MD, PhD

Dale H. Rice, MD

Ernesto Ried, MD

Alessandra Rinaldo, MD, FRSM

Joshua D. Rosenberg, MD

Allan Maier Rubin, MD, PhD, FACS

John S. Rubin, MD, FACS, FRCS

Amy L. Rutt, DO

Anthony Sclafani, MD, FACS

Raja R. Seethala, MD

Jamie Segel, MD

Moncef Sellami, MD

Michael Setzen, MD, FACS, FAAP

Stanley Shapshay, MD

Douglas M. Sidle, MD

Herbert Silverstein, MD

Jeffrey P. Simons, MD

Raj Sindwani, MD, FACS, FRCS

Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

William H. Slattery III, MD

Libby Smith, DO

Jessica Somerville, MD

Thomas C. Spalla, MD

Matthew Spector, MD

Paul M. Spring, MD

Brendan C. Stack, Jr., MD, FACS

James A. Stankiewicz, MD

Jun-Ichi Suzuki, MD

David Thompson, MD

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Helga Toriello, PhD, FACMG

Ozlem E. Tulunay-Ugur, MD

Galdino Valvassori, MD

Emre Vural, MD

Donald T. Weed, MD, FACS

Neil Weir, FRCS

Kenneth R. Whittemore, MD

David F. Wilson, MD

Ian M. Windmill, PhD

Ian J. Witterick, MD,MSc, FRCSC

Richard J. Wong, MD

Naoaki Yanagihara, MD

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Anthony Yonkers, MD

Mark Zacharek, MD

Joseph Zenga, MD

Liang Zhou, MD

CLINIC EDITORS

Dysphagia

Jamie A. Koufman, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Facial Plastic Surgery

Anthony P. Sclafani, MD, FACS

Geriatric Otolaryngology

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD, FACS

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Head and Neck

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Reena Gupta, MD

Imaging

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Laryngoscopic

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Otoscopic

John W. House, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Pathology

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Pediatric Otolaryngology

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Rhinoscopic

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Special Topics

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Thyroid and Parathyroid

David Goldenberg, MD

98 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl., Philadelphia, PA 19107 entjournal@phillyent.com Ph: 215-732-6100

Managing Editor Linda Zinn

Manuscript Editors Martin Stevenson and Wayne Kuznar

Associate Editor, Reader Engagement Megan Combs

Creative Director Eric Collander

National Sales Manager Mark C. Horn mhorn@vendomegrp.com Ph: 480-895-3663

Traffic Manager Eric Collander

Please send IOs to adtraffic@vendomegrp.com

All ad materials should be sent electronically to: https://vendome.sendmyad.com

Customer Service/Subscriptions

www.entjournal.com/subscribe Ph: 888-244-5310 email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com

Reuse Permissions Copyright Clearance Center info@copyright.com Ph: 978-750-8400 Fax: 978-646-8600

Chief Executive Officer Jane Butler

Chief Marketing Officer Dan Melore

Vice President, Finance Bill Newberry

Vice President, Custom Media Jennifer Turney Director, Circulation Rachel Beneventi

ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal (ISSN: Print 0145-5613, Online 1942-7522) is published 9 times per year in Jan/Feb, Mar, Apr/May, June, July, Aug, Sept, Oct/ Nov and Dec, by Vendome Group, LLC, 237 West 35th Street, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10001-1905.

©2018 by Vendome Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal may be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast in any form or in any media without prior written permission of the publisher. To request permission to reuse this content in any form, including distribution in education, professional, or promotional contexts or to reproduce material in new works, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at info@ copyright.com or 978.750.8400.

EDITORIAL: The opinions expressed in the editorial and advertising material in this issue of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal are those of the authors and advertisers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher, editors, or the staff of Vendome Group, LLC. ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed and Current Contents/Clinical Medicine and Science Citation Index Expanded. Editorial offices are located at 812 Huron Rd., Suite 450, Cleveland, OH 44115. Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.editorialmanager.com/entjournal. Instructions for Authors are available at www.entjournal.com.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For questions about a subscription or to subscribe, please contact us by phone: 888-244-5310; or email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com. Individual subscriptions, U.S. and possessions: 1 year $225, 2 years $394; International: 1 year $279, 2 years $488; Single copies $28; outside the U.S., $40.

POSTMASTER: send address changes to Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, PO Box 11404 Newark, NJ 07101-4014.

100 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

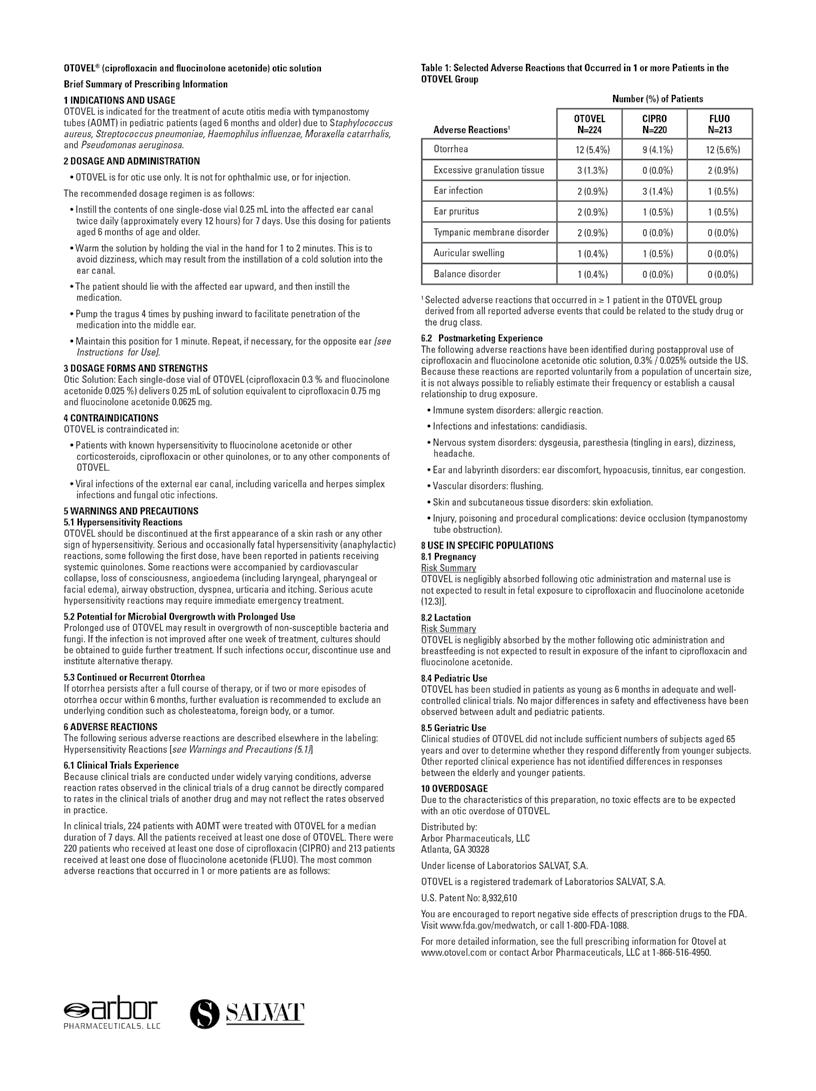

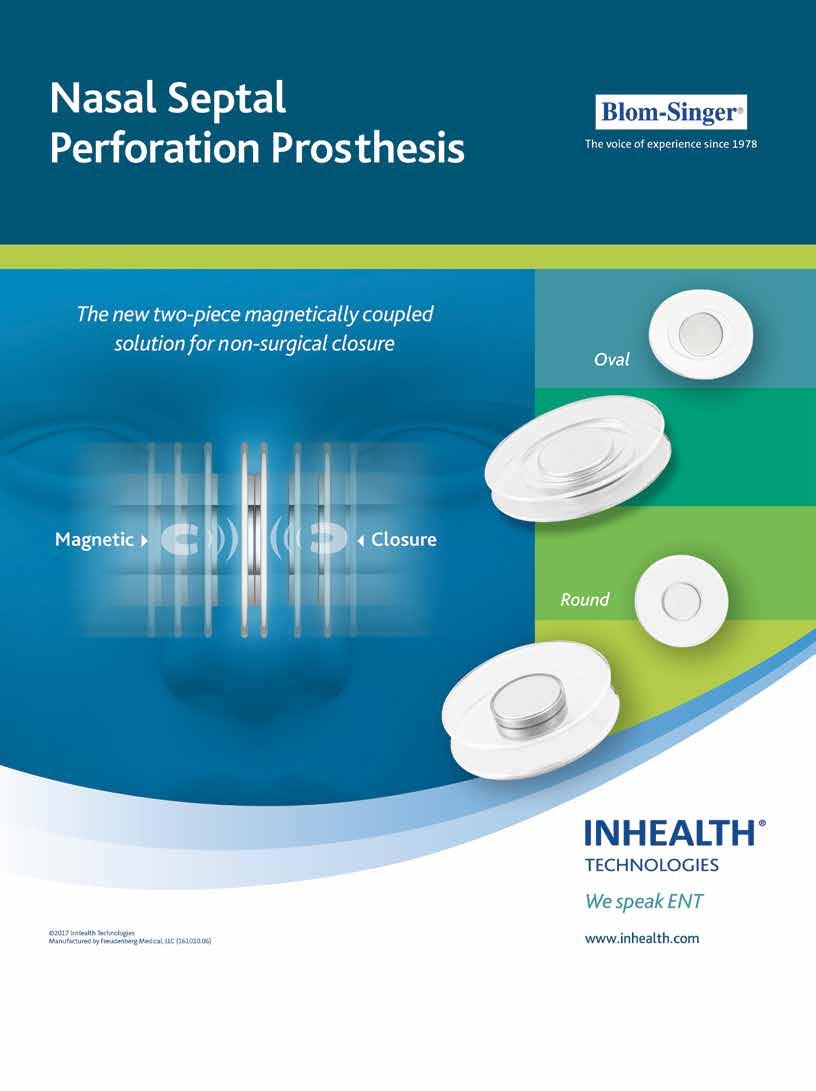

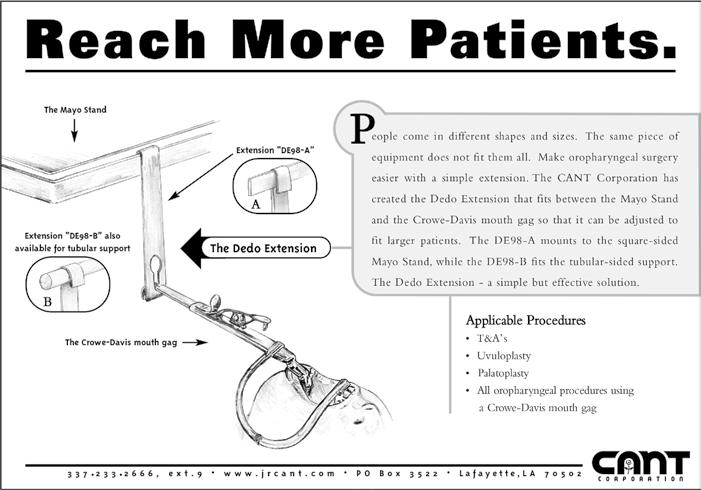

ADVERTISER INDEX Pages Acclarent, Inc. 103 American Rhinologic Society ............. CVR2 Arbor Pharmaceuticals 123-124 CANT Corporation ................................. 105 Coastal ENT 100 Compulink Business Systems ............ CVR3 Eagle Surgical Products, LLC 111 Entellus .................................................... 99 Fyzical Therapy and Balance 97 InHealth Technologies ........................... 101 McKeon Products, Inc. CVR4 Reliance Medical ................................... 129 Xlear, Inc. 107

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

116 Microcomputed tomography of the stapes: Wide-ranging dimensions

Jason Patrick Calligas, MD; Norman Wendell Todd Jr., MD, MPH

119 An absence of cilia outer microtubules, an etiology not previously recognized in bilateral mucocele

Javier E. Spínola-Hernández, MD; Andrés E. Castell-Rodríguez, MD; Héctor M. Prado-Calleros, MD; Gerardo A. Bravo-Escobar, MD; Andrés Sadek-González, MD

122 Computational analysis of swallowing mechanics after surgery for obstructive sleep apnea

Mark A. Ellis, MD; Mariah B. Pate, MD; Hugh D. Dorris, BA; William G. Pearson Jr., PhD; Jimmy J. Brown, DDS, MD

128 Vocal tract symptoms: Severity and frequency in patients on statins

Abdul-Latif Hamdan, MD, MPH, FACS; Marc Mourad, MD; Ghina Fakhri, BS; Doja Sarieddine, BS; Elie Khalifee, MD; Sami T. Azar, MD

134 Undifferentiated sarcoma presenting as a slowly enlarging facial mass

Alexis Lopez, MD, MPH; Anton M. Kushnaryov, MD; Robert A. Weisman, MD

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

E1 Anxiety, depression, and hopelessness in patients before and after treatment for peripheral facial paralysis

Fatih Arslan, MD; Mert Cemal Gökgöz, MD; Murat Binar, MD; Emre Aydemir, MD; Abdullah Durmaz, MD

E5 Early experience in endoscopic transoral resection for parapharyngeal space tumors

Ling-zhao Meng, MD; Qi Zhong, MD; Ju-gao Fang, MD; Hong-zhi Ma, MD; Jian-hong Wang, MS; Yong-xiang Wei, MD

E10 Surgical treatment of symptomatic subglottic stenosis during the third trimester of pregnancy

Erin R.S. Hamersley, DO, LT MC USN;

Angel J. Perez, MD, LCDR MC USN;

Michele P. Morrison, DO, CDR MC USN, FACS;

Halton W. Beumer, MD, MAJ MC USAF

E13 A unique manifestation of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations of atypical cases

Judit Kálmán, MD; Tamás Horváth, MD, PhD; Bálint Liktor, MD; Balázs Liktor, MD, PhD

E18 Esthesioneuroblastoma with widespread distant metastasis: Case report and literature review

Manraj Khosla, MD; Cristina Pecci, DO; Annie Do, MD; Lee McGhan, MD; Mahesh Seetharam, MD; Richard Sue, MD

E22 Screening and management of postoperative hypoparathyroidism-induced hypocalcemia in thyroidectomized patients in the endocrine ward compared with the surgical ward

Nina Sauer, MD; Anne Lautenbach, MD; Katharina Pohl, MD; Gerhard Schön, MD; Hans-Peter Brose, MD;

Clarissa Alexandra Schulze zur Wiesch, MD; Jens Carsten Aberle, MD

E27 Powered irrigation with suction evacuation for chronic rhinosinusitis in the office setting: A pilot study

Margherita Bruni, MD; Lindsey E. Ryan, MD; Mark H. Tabor, MD

E31 Horizontal (vs. vertical) closure of the neo-pharynx is associated with superior postoperative swallowing after total laryngectomy

Giannis Thrasyvoulou, MD, PGCert Med, PhD; Petros V. Vlastarakos, MD, MSc, PhD; Michael Thrasyvoulou, BSc(Math); Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

E36 Wireless mobile ultrasonography-assisted parotid duct stone removal

Na Rae Oh, MD; Joo Hyun Woo, MD, PhD; Dong Young Kim, MD, PhD; Min Kwan Baek, MD, PhD

102 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018 EDITORIAL OFFICE Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS, Editor-in-Chief • 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl. • Philadelphia, PA 19107 CONTENTS APRIL/MAY 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 4-5

DEPARTMENTS 100 Advertiser Index 104 ENT Journal Online 106 Guest Editorial 108 Rhinoscopic Clinic 109 Laryngoscopic Clinic 112 Head and Neck Clinic 114 Dysphagia Clinic E39 Otoscopic Clinic

JOURNAL ONLINE

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal's website is easy to navigate and provides readers with more editorial content each month than ever before. Access to everything on the site is free of charge to physicians and allied ENT professionals. To take advantage of all our site has to offer, go to www.entjournal. com and click on the “Registration” link. Once you have filled out the brief registration form, you will have full access. Explore and enjoy!

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

Anxiety, depression, and hopelessness in patients before and after treatment for peripheral facial paralysis

Fatih Arslan, MD; Mert Cemal Gökgöz, MD; Murat Binar, MD; Emre Aydemir, MD; Abdullah Durmaz, MD

We conducted a prospective study to investigate the effectiveness of pharmacologic treatment on alleviating facial paralysis, as well as the anxiety and depression that are associated with it. Our study population was made up of 105 patients—59 men and 46 women, aged 18 to 60 years (mean: 38.2)—who had acute idiopathic peripheral facial paralysis. Before treatment, paralysis was classified as House-Brackmann grade II or III in 44 patients (41.9%) and grade IV to VI in the remaining 61 (58.1%). After....

Early experience in endoscopic transoral resection for parapharyngeal

space tumors

Ling-zhao Meng, MD; Qi Zhong, MD;

Ju-gao Fang, MD; Hong-zhi Ma, MD;

Jian-hong Wang, MS; Yong-xiang Wei, MD

The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of the resection of parapharyngeal space (PPS) tumors via an endoscopic transoral approach. We reviewed 9 patients who were diagnosed with PPS tumors and who were treated with an endoscopic transoral approach. PPS tumors ranging from 2.5 to 6 cm were removed completely with no complications and excellent recovery (mean inpatient hospital stay: 6.89 days). Pathology was pleomorphic adenoma (n = 7), schwannoma (n = 1) and malignant pleomorphic adenoma (n = 1)....

Surgical treatment of symptomatic subglottic stenosis during the third trimester of pregnancy

Erin R.S. Hamersley, DO, LT MC USN;

Angel J. Perez, MD, LCDR MC USN;

Michele P. Morrison, DO, CDR MC USN, FACS;

Halton W. Beumer, MD, MAJ MC USAF

Subglottic stenosis is a narrowing of the airway distal to the glottis. Airway narrowing can be severe and, when coupled with pregnancy, can pose a significant threat to the mother and fetus. There is sparse literature describing treatment of these critical patients, posing a challenge for management. We describe our experience with a 31-year-old woman with idiopathic subglottic stenosis who became symptomatic during her pregnancy, requiring surgical intervention early in her third trimester. The....

A unique manifestation of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations of atypical cases

Judit Kálmán, MD; Tamás Horváth, MD, PhD; Bálint Liktor, MD; Balázs Liktor, MD, PhD

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is regarded as a clonal disease, usually carrying the activating BRAF mutation V600E. Although LCH theoretically may affect all types of human tissue and typically appears during childhood, temporal bone involvement in adult patients is exceedingly rare. We report an atypical case of a 56-year-old man as one of the oldest patients diagnosed with temporal bone involvement of a BRAF-negative LCH, which caused painless otorrhea and hearing loss. Cutaneous manifestation (multifocal multisystem LCH, also known as Letterer-Siwe....

Esthesioneuroblastoma with widespread distant metastasis: Case report and literature review Manraj Khosla, MD; Cristina Pecci, DO; Annie Do, MD; Lee McGhan, MD; Mahesh Seetharam, MD; Richard Sue, MD

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB) is an uncommon sinonasal tract tumor, and it is even more uncommon among all neoplasms. Literature regarding the incidence and spread of the disease is limited. The prognosis of metastatic disease is poor. In this report, we present a case of recurrent ENB in a young woman involving metastasis to the neck, lungs, and ovary. Metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes is relatively common, but metastasis to the lungs is rare. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no cases of ovarian metastases of ENB have been reported. This case highlights....

Screening and management of postoperative hypoparathyroidism-induced hypocalcemia in thyroidectomized patients in the endocrine ward compared with the surgical ward

Nina Sauer, MD; Anne Lautenbach, MD; Katharina Pohl, MD; Gerhard Schön, MD; Hans-Peter Brose, MD;

Clarissa Alexandra Schulze zur Wiesch, MD;

Jens Carsten Aberle, MD

Transient hypoparathyroid-associated hypocalcemia is a common side effect after thyroidectomy. Not only may it be life-threatening, but it also can distinctly affect length of hospital stay and treatment costs. Screening and treatment practices are suspected to differ between clinicians in endocrine and surgical wards. We therefore compared....

104 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018 www.entjournal.com

Powered irrigation with suction evacuation for chronic rhinosinusitis in the office setting: A pilot study

Margherita Bruni, MD; Lindsey E. Ryan, MD; Mark H. Tabor, MD

Bacterial infections in the form of adherent biofilms are frequently implicated in the pathogenesis and recalcitrance of chronic rhinosinusitis. The Hydrodebrider, a disposable powered irrigation and suction device, has been developed specifically to remove biofilm from the paranasal sinuses. We conducted a prospective study to evaluate the tolerability and efficacy of the Hydrodebrider in the office setting with....

Horizontal (vs. vertical) closure of the neo-pharynx is associated with superior postoperative swallowing after total laryngectomy

Giannis Thrasyvoulou, MD, PGCert Med, PhD; Petros V. Vlastarakos, MD, MSc, PhD; Michael Thrasyvoulou, BSc(Math); Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

We conducted a cross-sectional study to compare the horizontal and vertical methods used in the surgical closure of the neo-pharynx after total laryngectomy in terms of their effect on swallowing function, swallowing-related quality....

Wireless mobile ultrasonography-assisted parotid duct stone removal

Na Rae Oh, MD; Joo Hyun Woo, MD, PhD;

Dong Young Kim, MD, PhD; Min Kwan Baek, MD, PhD

Ultrasonography is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of sialoliths. Recently, wireless mobile ultrasonography was developed. We describe the case of a 49-year-old man who presented with painful postprandial left cheek swelling. Computed tomography detected a solitary 5-mm parotid duct stone with infection at the anterior portion of the left masseter muscle. Transoral stone removal was planned, although difficulty was expected in view of the surrounding infection. Surgery was performed under the guidance of mobile ultrasonography, and the stone was removed safely.

ONLINE DEPARTMENTS

Otoscopic Clinic: Iatrogenic external auditory canal stenosis induced by silver nitrate

Samantha J. Mikals, MD; Zhen Huang, MD, MBA; Brian K. Reilly, MD, FACS, FAAP; Ashkan Monfared, MD

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 105 ENT JOURNAL ONLINE

GUEST EDITORIAL

Rough sailing on a sea of gray

It is not news that our patients are aging. It is not news that older patients pose unique clinical challenges. It is not news that the health insurer for these patients, Medicare, is under tremendous pressure to reduce the cost of providing healthcare for older patients. It is not news that the level of political inaction, which borders on indifference, is resulting in the problems associated with our aging population becoming ever more daunting, and potentially insurmountable. What is not news is that the physician workforce is graying, a process that will increase the burden on those who continue in active practice. What may be news to many of our colleagues is that there is an otolaryngology society, the American Society of Geriatric Otolaryngology, that has made its mission to assist otolaryngologists in navigating the rough sea of gray.

Founded a decade ago, the American Society of Geriatric Otolaryngology (ASGO) has engaged with the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO–HNS), the Triological Society, and other specialty societies, to prepare our specialty for the gray tsunami. ASGO has focused, and will continue to focus, on understanding the unique clinical challenges older patients face, and pose. The AAO–HNS and the Triological Society deserve mention for their support and assistance with arranging meeting space for ASGO’s annual meeting. ASGO, through its annual meeting, has tackled such diverse topics as preoperative management of the older surgical patient, presbylaryngis, presbycusis, presbystasis, swallowing disorders, end of life, head and neck oncology, vestibular evaluation, bone-anchored hearing aid and cochlear implantation in the elderly, the future of Medicare, and when not to operate.

ASGO members not only contribute with lectures and peer-reviewed medical literature, but they also have collaborated to author, with the assistance of Thieme Medical Publishers and AAO–HNS, the textbook Geriatric Otolaryngology (2015, Print ISBN: 9781626239777, EBook ISBN: 9781626239784). Edited by Dr. Robert T. Sataloff, Dr. Michael Johns, and Dr. Karen Kost, the text is an essential resource for otolaryngologists and other health professionals who care for older patients. Why engage with and through ASGO? Where others see only overwhelming challenges, ASGO sees remarkable opportunity for independent thinking and action by a group of like-minded otolaryngologists. While acknowledging the difficult facts of the current reality, ASGO is driven by the belief that by working through those same challenges as concerned and engaged colleagues, we can, in the end, ensure that geriatric otolaryngology patients receive the care they need, and that those who care for geriatric patients are compensated fairly. Annual dues are modest at $100 a year and include the annual meeting. Residents have no annual dues and have an annual opportunity to present their research related to geriatric otolaryngology. For those interested, ASGO’s secretary, Dr. Carl Shipp, would welcome an inquiry: GCShipp@uams.edu.

Brian J. McKinnon, MD, MBA, MPH, FACS

Associate Professor and Vice Chair

Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Associate Professor

Department of Neurosurgery

Drexel University College of Medicine

Associate Professor and Vice Chair

Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Associate Professor

Department of Neurosurgery

Drexel University College of Medicine

Philadelphia

106 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

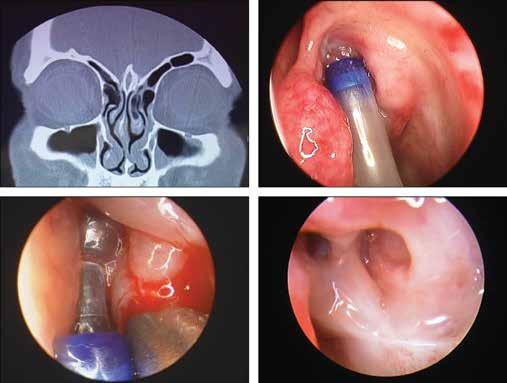

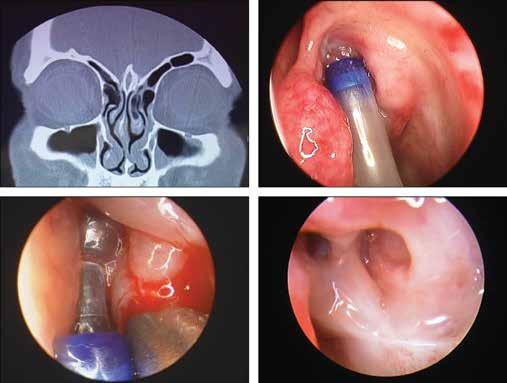

Balloon catheter dilation of a septated frontal sinus

A 32-year-old man presented with intermittent recurrent left frontal headaches. He had noticed that the headaches occurred when he had significant nasal congestion. He had a history of allergies for which he had been treated over a 6- year period.

Computed tomography (CT) of the sinuses revealed a large, septated, left frontal sinus with evidence of obstruction of the nasofrontal duct and mucosal thickening (figure, A). Nasal examination was unremarkable other than pale, boggy, allergic appearing

Continued on page 110

From the Department of Otolaryngology, the Halifax Medical Center, Daytona Beach, Fla. (Dr. Mirante and Dr. Christmas); Florida State University School of Medicine, Daytona Beach (Dr. Mirante); and the Section of Otolaryngology, Yale New Haven Hospital–St. Raphael Campus and the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Ct. (Dr. Yanagisawa).

108 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

RHINOSCOPIC CLINIC

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS; Dewey A. Christmas, MD; Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

A B C D

Figure. A: CT Scan of the sinus shows septation in the left frontal sinus. B: A cannula is inserted into the left middle meatus and placed into the left frontal recess. C: An inflated balloon is seen in the left frontal recess. D: The left frontal recess is viewed 2 years after the balloon dilation.

LARYNGOSCOPIC CLINIC

An undulating vallecular cyst

Yu-Hsuan Lin, MD; Ming-Yee Lin, MD, PhD

A vallecular cyst is an uncommon and generally benign lesion in the larynx. In adults, it is usually asymptomatic, but it can cause airway distress. Although most lesions are indolent, physicians should maintain full awareness of the potential occurrence of unanticipated catastrophic consequences in those rare cases in which such a cyst might enlarge and produce airway obstruction.

A 47-year-old man presented to our Otolaryngology Department complaining of a decade-long lump-inthe-throat sensation. His medical history was not remarkable. Diagnostic indirect laryngoscopy revealed a well-delineated cystic mass lying on the right vallecular fossa (figure, A). When we asked the patient to phonate, the mass shifted to the left side (figure, B). The tumor

oscillated from side to side along the axis of the median glossoepiglottic fold.

The patient underwent an endoscopic total excision. Histopathology revealed a cystic structure composed of stratified squamous and columnar epithelium, with no lymphatic elements or oncocytic changes, compatible with a diagnosis of a ductal cyst. After surgical excision, the patient’s symptom vanished. He had no recurrence over the next 27 months.

Vallecular cysts (VCs) account for approximately 10.5% of all laryngeal cysts.1-3 VC has a higher occurrence in the fifth and sixth decades of life, with no sex predilection.1-3 There is no consensus on the genesis and development of VCs; a commonly accepted hypothesis

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 109

From the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainen, Taiwan (Dr. Y.H. Lin); and the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (Dr. M.Y. Lin).

A B

Figure. The laryngoscopic exam reveals a vallecular cyst attached to the median glossoepiglottic fold. The cyst flickers from side to side when the patient is asked to phonate and sniff repeatedly (A and B).

LARyNgOSCOPIC CLINIC

is that the cyst is either an embryologic remnant or a consequence of ductal obstruction.1-3

In contrast to infantile VC—which is recognized as a distinct entity and often occurs with laryngomalacia, leading to choking during feeding, cyanotic spells, failure to thrive, and a feeling of airway obstruction— adult VC is usually asymptomatic.4 Patients sometimes present with relapsing acute epiglottitis or an episode of epiglottic abscess.5 The differential diagnosis includes hemangioma, lymphangioma, teratoma, thyroid ectopia and, thyroglossal duct cyst. Endoscopic excision and transoral laser marsupialization are effective treatments.6 Repeated aspiration of the lesion represents a more conservative strategy, but it is often associated with a higher recurrence rate.4,6

References

1. DeSanto LW, Devine KD, Weiland LH. Cysts of the larynx— classification. Laryngoscope 1970;80(1):145-76.

2. Forte V, Fuoco G, James A. A new classification system for congenital laryngeal cysts. Laryngoscope 2004;114(6):1123-7.

3. Arens C, Glanz H, Kleinsasser O. Clinical and morphological aspects of laryngeal cysts. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1997; 254(9-10):430-6.

4. Tsai YT, Lee LA, Fang TJ, Li HY. Treatment of vallecular cysts in infants with and without coexisting laryngomalacia using endoscopic laser marsupialization: Fifteen-year experience at a single center. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77(3):424-8.

5. Berger G, Averbuch E, Zilka K, et al. Adult vallecular cyst: Thirteen-year experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 138(3):321-7.

6. Su CY, Hsu JL. Transoral laser marsupialization of epiglottic cysts. Laryngoscope 2007;117(7):1153-4.

Continued from page 108

nasal mucosa. Because of the long-standing left frontal headaches and failure of adequate medical therapy, the patient elected to undergo left frontal sinus balloon dilation.

The left frontal sinus balloon catheter dilation was carried out through the left frontal recess (figure, B). The balloon was inflated in the usual manner, and an adequate opening was obtained through the left frontal recess (figure, C).

The patient’s left frontal headache problem resolved after the surgery and has not recurred over a period of 2 years. Endoscopic examination of the nose 2 years postoperatively revealed a widely patent left frontal recess area (figure, D).

Balloon catheter dilation has been described as an excellent tool in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis.1 It has been associated with symptomatic relief comparable to that associated with traditional endoscopic sinus surgery, but with less tissue destruction. 2 The case presented shows long-term patency of the frontal recess.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Grayson Bertaina for his assistance in preparing this article.

References

1. Kuhn FA, Church CA, Goldberg AN, et al. Balloon catheter sinusotomy: One-year follow-up-outcomes and role in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 39(3 Suppl 3):S27-37.

2. Bizaki AJ, Taulu R, Numminen J, Rautiainen M. Quality of life after endoscopic sinus surgery or balloon sinuplasty: A randomized clinical study. Rhinology 2014;52(4):300-5.

110 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

CLINIC

RHINOSCOPIC

HEAD AND NECK CLINIC

Aggressive desmoid fibromatosis of the neck after total thyroidectomy

Alexander Delides, MD, PhD; Ioannis Plioutas, MD; Stephanos Konstantoudakis, MD; Pavlos Maragoudakis, MD, PhD

Alexander Delides, MD, PhD; Ioannis Plioutas, MD; Stephanos Konstantoudakis, MD; Pavlos Maragoudakis, MD, PhD

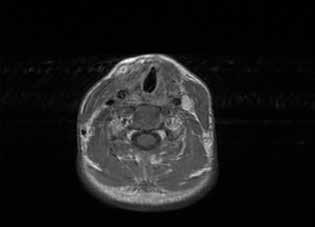

A 21-year-old woman underwent total thyroidectomy. Three years later, she noticed a neck mass and increasing discomfort in her neck. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass near the site of the previous thyroidectomy, on the right. Fine-needle-aspiration cytology tests were nondiagnostic.

The patient underwent surgery, during which a paralaryngeal mass was found firmly attached to the surrounding structures and impossible to dissect.

Frozen section biopsy was negative for malignancy; a biopsy was taken for permanent section, and the wound was closed. The histologic diagnosis was desmoid tumor.

During the following weeks, the patient’s symptoms rapidly worsened and she was referred to our department, complaining of severe swallowing difficulty. She was not hoarse and had no pain.

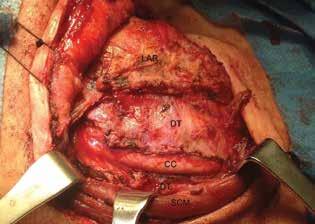

Physical examination revealed a firm, palpable neck mass fixated on the right (figure 1, A). Laryngeal endoscopy showed normal vocal fold movement and a projection of the posterior pharyngeal wall. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an 11-cm mass extending from the right to the left sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles (figure 1, B). Surgery was scheduled, with the goal to resect as much tumor as possible and to refer the patient for postoperative radiotherapy.

112 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

From the 2nd Otolaryngology Department (Dr. Delides, Dr. Plioutas, and Dr. Maragoudakis) and the 2nd Department of Pathology (Dr. Konstantoudakis), Attikon University Hospital, Athens, Greece.

A B

Figure 1. A: Photo shows the appearance of the neck, with enlargement of the right side and obliteration of the space between the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the larynx. The scar of the previous thyroidectomy is visible. B: T2-weighted MRI of the neck reveals the tumor occupying the space between the larynx and the spine and extending between the large vessels on both sides. The right carotid is enclosed within the tumor.

During surgery, a nasogastric tube was placed as a palpable guide to the esophagus. A right hockey-stick incision, including the previous thyroidectomy incision, was made. After elevation of the subplatysmal flaps, the tumor was found completely occupying the space between the right SCM and the larynx. It was dissected away from the SCM, the larynx, the cervical spine, and the esophagus. The right common carotid was surrounded by the tumor but was palpated and used as a landmark (figure 2). The internal jugular vein was saved, but the right inferior laryngeal nerve was sacrificed. An attachment to the right cricothyroid muscle was noticed as a possible point of tumor origin.

Postoperatively, the patient had bilateral vocal fold palsy, but movement of the left vocal fold returned to normal 3 days later. She also had Horner syndrome on the right side, which improved after 3 months. Her swallowing difficulty immediately resolved, and she was discharged on the fifth day. One month later, a follow-up MRI showed no sign of tumor presence, and it was decided to wait before any additional treatment was undertaken.

Two years later, the patient remains disease-free (figure 3), so she is considered cured. Histology showed the lesion to have the morphologic aspects of extraabdominal fibromatosis.

Desmoid tumors are benign musculoaponeurotic tumors with the potential to strangle surrounding structures. They are caused by mutations of fibroblast

cells1 and do not metastasize. Their recurrence rates range between 20 and 77%.2

Treatment is surgical resection.3 External beam radiation or systemic drug treatment may be used when total resection is impossible. A history of prior trauma or surgery at the site of the tumor may be elicited. However, these tumors are considered a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory reactive process.4

This is the third case of a desmoid tumor after thyroidectomy, 5,6 the second after total thyroidectomy, 5 and, to the best of our knowledge, the first with such a large tumor to be completely cured by surgery.

References

1. Ali R, Parthiban N, O’Dwyer T. Desmoid fibromatosis of submandibular region. J Surg Tech Case Rep 2014;6(1):21-5.

2. Hoos A, Lewis JJ, Urist MJ, et al. Desmoid tumors of the head and neck—a clinical study of a rare entity. Head Neck 2000;22(8):814-21.

3. Merchant NB, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, et al. Extremity and trunk desmoid tumors: A multifactorial analysis of outcome. Cancer 1999;86(10):2045-52.

4. de Bree E, Zoras O, Hunt JL, et al. Desmoid tumors of the head and neck: A therapeutic challenge. Head Neck 2014;36(10):1517–26.

5. Arena S, Salamone S, Cianci R, et al. Aggressive fibromatosis of the neck initiated after thyroidectomy. J Endocrinol Invest 2006;29(1):78-81.

6. Wang CP, Chang YL, Ko JY, et al. Desmoid tumor of the head and neck. Head Neck 2006;28(11):1008-13.

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 113 HEAd ANd NECk CLINIC

Figure 2. Intraoperative view shows the tumor being opened to reveal the common carotid. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted posteriorly and the larynx anteriorly.

Figure 3. T1-weighted MRI of the neck 2 years after surgery reveals no presence of tumor.

DYSPHAGIA CLINIC

A rare cause of dysphagia: Pyriform sinus atypical lipomatous tumor

Atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT) and welldifferentiated liposarcoma (WDL) are rare liposarcoma subtypes that are histologically identical but distinguished by the 2002 WHO classification: ALTs occur in surgically amenable locations, whereas WDLs do not. This distinction exists because these tumors do not tend to recur after complete surgical removal, despite their infiltrative growth pattern and locally aggressive behavior.1

A 60-year-old male nonsmoker presented for evaluation of several months of throat irritation and a sense of something stuck in his throat. Physical examination was normal, except flexible endoscopy revealed a benignappearing, pedunculated mass with normal-appearing mucosa extending from the posterolateral pharyngeal wall onto the arytenoid tower. Computed tomography showed a benign-appearing mass within the left hypopharynx effacing the pyriform sinus.

The patient underwent transoral robotic surgical (TORS) excision of the mass. It was 5 cm in size, pedunculated and bilobed (figure 1, A). It was excised, leaving an approximately 1-cm mucosal defect. The specimen was soft and pink (figure 1, B). Microscopic examination

revealed a relatively circumscribed, adipocytic proliferation arranged in lobules of mature-appearing adipose tissue with prominent intervening fibrous septae. Random distribution of enlarged hyperchromatic cells with mild nuclear atypia and occasional multinucleation involved both the adipose and stromal components. Scarce lipoblasts and a rare hibernoma-like nodule were appreciated. Neither necrosis nor mitotic activity was identified. Cells were immunoreactive for MDM2 and p16, and nonreactive for p53, consistent with ALT (figure 2). Three months postoperatively, the patient had no evidence of recurrence.

ALT rarely presents in the laryngopharynx.1-3 In 2009, Davis et al reviewed all head and neck sarcomas at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center over a 60-year period (1945–2005) and found 30 head and neck liposarcomas, of which only 7 were ALT/WDLs.4 Three of these were in the upper aerodigestive tract. In 1999, Mandell et al compiled reports of eight hypopharyngeal liposarcomas from three studies, all of which were ALT/WDLs; they had a strong male predominance (7/8) and a size ranging from 2 to 14.5 cm.3 In 2010, Shi et al reported five ALTs in the laryngopharynx: two

From the Department of Otolaryngology, Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the United States government.

114 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

Yoseph A. Kram, MD; James M. McCann, DMD, MS; Joseph Golden, MD; Eric Wirtz, MD

A B

Figure 1. A: Intraoperative image shows the pedunculated, bilobed tumor in the left hypopharynx. B: The 5-cm excised tumor is soft and pink with a fatty appearance.

in the hypopharynx and three in the larynx, ranging from 2.0 to 5.0 cm.2 Dysphagia, dysphonia, and globus sensation were typical presenting symptoms.

Immunohistochemistry staining of MDM-2, a negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor, and p16 have emerged as markers for ALT/WDL. A 2017 study of 101 ALTs showed that dual p16 and MDM2 testing yielded a 100% positive predictive value and a 100% negative predictive value when MDM2+/p16+ and MDM2–/p16–staining were observed for ALT-WDL, respectively.5

Surgical excision in the hypopharynx can be challenging because of inadequate access and visualization. Classic approaches include lateral pharyngotomy or direct suspension microlaryngoscopy.6 Radiation is not recommended as primary therapy for hypopharyngeal ALTs but has been offered as adjunctive therapy.3,4 If TORS continues to show a low recurrence rate for ALTs, it will further differentiate them from WDLs.

References

1. Dei Tos AP, Pedeutour F. Atypical lipomatous tumour/well differentiated liposarcoma. In: Fletcher C, Unni KK, Mertens F (eds). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002:35-7.

2. Shi HY, Wei LX, Wang HT, Sun L. Clinicopathological features of atypical lipomatous tumors of the laryngopharynx. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2010;11(12):918-22.

3. Mandell DL, Brandwein MS, Woo P, et al. Upper aerodigestive tract liposarcoma: Report on four cases and literature review. Laryngoscope 1999;109(8):1245-52.

4. Davis EC, Ballo MT, Luna MA, et al. Liposarcoma of the head and neck: The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Head Neck 2009;31(1):28-36.

5. Kammerer-Jacquet SF, Thierry S, Cabillic F, et al. Differential diagnosis of atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma: Utility of p16 in combination with MDM2 and CDK4 immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol 2017;59:34-40.

6. Wenig BM, Heffner DK. Liposarcomas of the larynx and hypopharynx: A clinicopathologic study of eight new cases and a review of the literature. Laryngoscope 1995;105(7 Pt 1):747-56.

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 115 dySPHAgIA CLINIC

Figure 2. The tumor is positive for p16 on immunohistochemical staining.

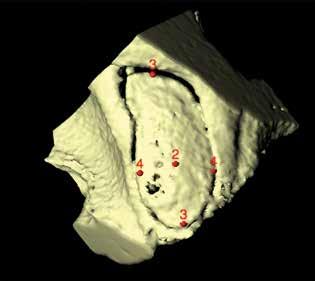

Microcomputed tomography of the stapes: Wide-ranging dimensions

Jason Patrick Calligas, MD; Norman Wendell Todd Jr., MD, MPH

Abstract

Although human stapes are known to have varied dimensions and the footplate is considered to be oval (fitting as it does into the oval window), few studies of high-resolution imaging of these structures have been performed. No study appears to have addressed the bilateral symmetry of stapes dimensions or to have determined if an association exists between the size of the stapes and the size of mastoid pneumatization; a small mastoid pneumatization is an indicator of childhood otitis media. We obtained 41 ear-normal cadaver crania specimens for study in our temporal bone laboratory and isolated 10 for further analysis: the 5 with the largest areas of mastoid pneumatization and the 5 with the smallest. Microcomputed tomography of tissue blocks was performed on the in situ stapes. Using ImageJ software, we created a three-dimensional model of each stapes. The mean height of these stapes was 3.43 mm (range: 3.20 to 3.80), the mean length of the footplates was 2.71 mm (range: 2.52 to 2.97), and the mean width of the footplates was 1.23 mm (range: 1.12 to 1.46). Qualitatively, the footplate was shaped like a human footprint in moist sand, as Eysell described in 1870. The dimensions of the stapes were found to be bilaterally symmetrical in general, but there was no correlation between these dimensions and the size of mastoid pneumatization. The distribution of footplate widths may be bimodal, which is consistent with the observation of Sim et al that men have wider footplates than do women.

Introduction

The stapes, the smallest of all the named bones in the human body, has intrigued clinicians and researchers for many years. More than a century ago, Eysell1 and Urbantschitsch2 published qualitative and quantitative descriptions of the stapes. Dass et al in 1966 reported marked variations in stapedial structure.3 Working with a precision caliper under a microscope, aWengen et al found an impressive range of distances in six measurements between

From the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Corresponding author: Norman Wendell Todd Jr., MD, MPH, Emory Children’s Center, 2015 Uppergate Dr., NE, Atlanta, GA 30329.

Email: ntodd@emory.edu

various points on the stapes.4 Rouset et al, studying normal ears with clinical computed tomography (CT), found that stapes heights ranged from 2.3 to 4.2 mm (mean: 3.7).5

Using microcomputed tomography (microCT), Sim et al reported stapes heights and footplate lengths and widths as 3.28 (±0.21), 2.81 (±0.16), and 1.27 (±0.11) mm, respectively, in predominately right-sided stapes.6 They also reported that men have wider footplates than do women.

In this article, we describe our study to validate the work of Sim et al,6 as well as to assess bilateral symmetry in the quantitative features in pairs of stapes and to determine the qualitative appearance of the footplates. Our hypothesis was that there is symmetry between the stapes pairs—a feature that to the best of our knowledge has not been previously studied. Bilateral symmetry would suggest that genetic influences play a role in stapes development.

A secondary aim of our investigation was to correlate stapes metrics with mastoid pneumatization (minimal temporal bone pneumatization is a correlate of childhood otitis media).7,8 Our hypothesis was that the development of the stapes is independent of the size of mastoid pneumatization. To the best of our knowledge, this issue has not been explored, either.

A third goal was to determine if stapes height, footplate width, and footplate length are correlated. In other words, If a stapes is large in one dimension, is it large in the other dimensions, as well, and vice versa? The question is apropos, since Rodríguez-Vázquez reported that the entire stapes develops from the mesenchyme of the second branchial arch, independent of both the Reichert cartilage and the otic capsule.9

Finally, a fourth objective was to determine if the distribution of footplate widths is bimodal, since Sim et al reported that footplates are wider in men than in women.6

Materials and methods

Specimens. We studied 41 adult skulls (82 temporal bones) that were provided by the anatomy unit at the Emory University School of Medicine. The specimens had been obtained from humans who had bequeathed their bodies to science before they died. No information about the age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the do-

116 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

nors was available. While we knew that none of the donors had died of ear disease, further unambiguous historical ear data were not available.

On plain Law lateral radiography of the 82 temporal bones, the areas of mastoid pneumatization were traced as previously described.10 The 5 crania with the largest areas of mastoid pneumatization and the 5 with the smallest underwent microCT imaging.

MicroCT and 3-D reconstruction. Images of the 20 temporal bones from the 10 selected crania were obtained on a microCT device (Inveon MicroCT; Siemens Healthineers; Erlangen, Germany). Since the gross physical sizes of the temporal bones exceeded the imaging aperture of the scanner, the specimens were physically reduced. The microCT images were then made with a pixel size of 20 × 20 μm, a slice thickness of 21.5 μm, and a resolution of 46.499 pixels/mm.

Segmentation and 3-D volume reconstruction were performed with the ImageJ program and the plug-in BoneJ.11,12

First, each stapes was cropped from the surrounding structures and ambient air by hand. Second, the “background noise” was subtracted. Third, the image stack was processed with the Isosurface algorithm of BoneJ, which converts the stack into a triangular surface model. The surface model was saved into a Standard Tessellation Language (STL) file format for dimensional analysis of the stapes structure. Fourth, the 3-D viewer was used to visualize the STL models. Reference points were marked directly on the 3-D models and recorded as x, y, and z coordinates.

Complete stapes were missing from 2 tissue blocks before microCT imaging, and therefore no data were obtained from them. For 2 other stapes, the crura were

damaged before microCT imaging, making calculation of stapes height impossible.

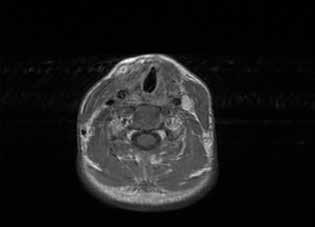

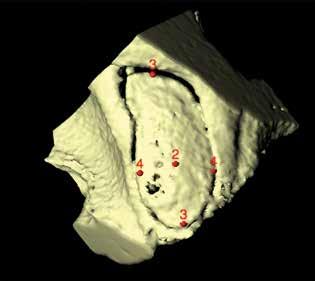

Stapes measurements. The stapes height was calculated by measuring the distance between a point in the center of the top of the capitulum and a point in the center of the stapes footplate on the medial (vestibular) surface (figure 1). The footplate’s length was calculated by measuring the distance between points on both ends of the long axis of the footplate annulus. The footplate’s width was calculated by measuring points on both ends of the short and long axes of the footplate annulus.

After we created the models in BoneJ, we identified each landmark in 3-D space (x, y, and z) with the point tool. For measurements of the footplate length, we used the landmarks that represented the farthest point on the “big toe” side of the footplate and the farthest point at the “heel.” For footplate width, we determined the widest diameter perpendicular to the footplate length. Footplate dimensions were thus determined in a manner analogous to a shoe salesman measuring a foot (figure 2). Each measurement was performed twice, independently. Calculations and statistics. Distance measurements were calculated according to the Pythagorean theorem in three dimensions. Only if associations were suggested on scatterplot graphs were nonparametric Spearman correlations calculated. No correction for multiple comparisons was done.

Ethical considerations. Our university’s Institutional Review Board determined that IRB approval was not required because this study “does not meet the definition of ‘research involving human subjects’ or the definition of ‘clinical investigation’ under applicable federal regulations.”

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 117 MICROCOMPUTEd TOMOgRAPHy Of THE STAPES: WIdE-RANgINg

dIMENSIONS

Figure 1. MicroCT shows a right stapes viewed from a surgeon’s perspective, laterally onto the superstructure. Note the footplate’s socked-foot appearance, with the big toe anterorinferior. The red circle (1) indicates the center of the top of the capitulum.

Figure 2. MicroCT demonstrates a right footplate viewed onto the vestibular (medial) surface. The red circles denote the center of the footplate (2), the limits of its length (3), and the limits of its width (4) perpendicular to the length.

Table.

Results

The range of stapes heights was wide (3.20 to 3.80 mm; mean: 3.43), as were the ranges of footplate lengths (2.52 to 2.97 mm; mean: 2.71) and widths (1.12 to 1.46 mm; mean: 1.23). The repeatability of measurements was excellent (table).

Bilateral symmetry of the stapes measurements was suggested, but symmetry was statistically significant only for the footplate width (rs = 0.86; n = 8; 95% confidence interval: 0.39 to 0.97). No stapes feature showed a correlation with the size of mastoid pneumatization.

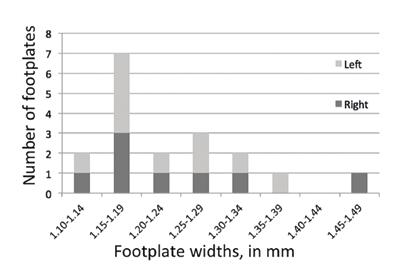

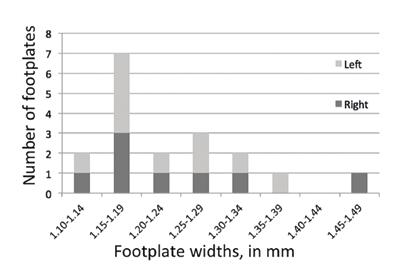

We found no correlation among the linear dimensions themselves—that is, if any one measured dimension of a stapes was small (or large), other measured dimensions of that stapes were not necessarily small (or large). Unlike the distribution of the stapes height and footplate length, the distribution of footplate width may be bimodal (figure 3).

Each footplate qualitatively resembled the appearance of a sock-covered human foot.

Discussion

The stapes measurements acquired in this study are consistent with those of previous reports.2-4,6 The mean height, footplate length, and footplate width for combined right and left stapes in our study was 3.43, 2.71, and 1.23 mm, respectively. Sim et al demonstrated similar findings using microCT analysis.6 They also reported that men have wider footplates than women (mean: 1.32 vs. 1.17 mm, p < 0.001).

Our study aimed to overcome a limitation of previous microCT analyses by looking at pairs of stapes. Bilateral sym-

metry was suggested for all three metrics, but because of the small number of specimens, we found statistical significance only with respect to footplate width.

No correlation of the stapes parameters and the size of mastoid pneumatization was suggested. Thus, these data may indicate that local middle ear environmental factors affecting pneumatization are unrelated to stapes development. The first and second branchial arches and the first pouch contribute to the development of the middle ear. Mastoid bone development occurs at a very different stage of life, but it might nevertheless be influenced by “intrinsic defects.”13 The fact that we did not find a correlation between stapes height and footplate length and width might be surprising, considering the second arch one-anlage origin of the entire stapes.9

* Repeatability is depicted by both the Spearman nonparametric correlation coefficient r s, with 95% confidence interval (CI), and by a clinically relevant value. Each measurement represents the mean of two independent measurements. Continued on page 121

118 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018 CALLIgAS, TOdd

Figure 3. Chart shows that the distribution of footplate widths appears to be bimodal, consistent with two populations (presumably male and female, according to the work of Sim et al6).

Measurement Repeatability, r s, (95% CI) Repeatability, practical Median (range) Mastoid area, right, all crania 0.89, n = 41, (0.80 to 0.94) 31/41, ≤2 cm2 9.6 cm2 (2.4 to 14.2) Mastoid area, left, all crania 0.92, n = 41, (0.85 to 0.95) 34/41 ≤2 cm2 10.0 cm2 (2.0 to 18.0) Height of stapes, right 0.99, n = 7, (0.93 to 0.99) 5/7 ≤0.05 mm 3.30 mm (3.20 to 3.80) Height of stapes, left 0.99, n = 9, (0.95 to 0.99) 7/10 ≤0.05 mm 3.45 mm (3.25 to 3.74) Length of footplate, right 0.80, n = 9, (0.21 to 0.96) 6/8 ≤0.05 mm 2.71 mm (2.62 to 2.97) Length of footplate, left 0.87, n = 10, (0.86 to 0.99) 6/10 ≤0.05 mm 2.68 mm (2.52 to 2.83) Width of footplate, right 0.87, n = 8, (0.42 to 0.98) 5/8 ≤0.05 mm 1.20 mm (1.13 to 1.46) Width of footplate, left 0.96, n = 10, (0.86 to 0.99) 9/10 ≤0.05 mm 1.22 mm (1.12 to 1.33)

Summary of the repeatability and distribution of each measurement*

An absence of cilia outer microtubules, an etiology not previously recognized in bilateral mucocele

Javier E. Spínola-Hernández, MD; Andrés E. Castell-Rodríguez, MD; Héctor M. Prado-Calleros, MD; Gerardo A. Bravo-Escobar, MD; Andrés Sadek-González, MD

Abstract

Most paranasal sinus mucoceles are unilateral and affect one or at most two contiguous sinuses. We describe the case of a 44-year-old woman with bilateral maxillary sinus mucoceles who presented clinically with left malar pain, right-sided swelling, and proptosis of the right eye. The diagnostic workup included computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, because of the atypical bilateral presentation, we analyzed mucosal sinonasal tissue samples by electron microscopy. Microscopic analysis revealed an absence of one of the microtubule doublets in three of the outer doublets of the axoneme, thereby establishing a diagnosis of isolated ciliary dysfunction. To the best of our knowledge, ciliary dysfunction as a cause of bilateral mucoceles has not been previously reported in the literature. The patient underwent successful surgery for removal of the mucoceles, and she exhibited no evidence of recurrence at the 18-month follow-up. When a diagnosis of bilateral mucocele formation is made, we suggest that ciliary dysfunction be considered in the differential diagnosis and that electron microscopy of the sinonasal mucosa be performed in the workup.

Introduction

Most paranasal sinus mucoceles are unilateral and affect one or at most two contiguous sinuses. They produce dilation of the involved sinus, as its interior fills with mucus produced by the mucosa. They usually arise as a

From the Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González,” Mexico City (Dr. Spínola-Hernández, Dr. Prado-Calleros, Dr. Bravo-Escobar, and Dr. Sadek-González); and the Department of Cell Biology and Tissue, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City (Dr. Castell-Rodríguez). The case described in this article occurred at General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González.”

Corresponding author: Hector M. Prado-Calleros, MD, Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González,” Calzada de Tlalpan 4800, Colonia Sección XVI, Delegación Tlalpan, 14080 Mexico City, Mexico. Email: hmpradoc@hotmail.com

result of occlusion of the sinus ostium, which can occur secondary to inflammation, scarring, or a neoplasm.1-3

Bilateral mucoceles are rarely reported. They can occur secondary to surgery, a papillomatous tumor, or chronic inflammation, and they might be related to mucous abnormalities or primary ciliary dyskinesia.1-3

The histologic appearance of mucoceles is remarkable given the intense intralesional pressure. They exhibit strips of flattened ciliated columnar epithelium with bone remodeling and chronic inflammation.4

Primary ciliary dyskinesia is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder that results in impairment of mucosal ciliary movement. It usually manifests as recurrent and chronic infections of the upper and lower airways.1 The structure of the ciliary apparatus consists of a microtubule-based axoneme, which is a highly ordered structure made up of nine peripheral microtubule doublets that are arranged around a central core. This core might or might not contain two central microtubules (a 9 + 2 axoneme and a 9 + 0 axoneme, respectively). The cilia of the 9 + 2 axoneme usually contain dynein arms that link the microtubule doublets, and the cilia are motile. Most cilia of the 9 + 0 axoneme lack dynein arms, and they are nonmotile. Mutations of two genes—DNAI1 and DNAH5 —account for about 30 to 50% of all cases of primary ciliary dyskinesia, and they are responsible for the defects in the outer dynein arms.1,5

In this article, we describe a case of bilateral maxillary sinus mucoceles that featured an absence of one of the microtubule doublets in three of the outer doublets of the axoneme, thereby establishing a diagnosis of isolated ciliary dysfunction.

Case report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a 7-month history of left malar pain, right-sided swelling, and proptosis of the right eye. Previously, her dentist had performed a left upper canine extraction. During that procedure,

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 119 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

the dentist had found a bulking lesion in the alveolar canine area that was filled with mucinous fluid.

On physical examination at our institution, we observed preserved vision in both eyes, but with a limitation of downward movement of the right eye. Nasal endoscopy detected swelling in the right lateral nasal wall and a white polypoid mass with smooth edges in the left nasal lateral wall. Both middle meatuses were without purulent discharge. Findings on the remainder of the examination were normal.

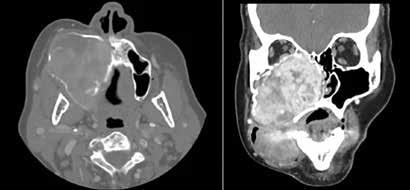

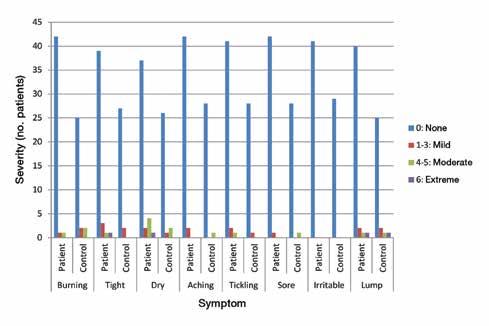

The diagnostic workup included computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which clearly demonstrated the bilateral masses in the maxillary sinuses (figure 1). Because of the atypical bilateral presentation of the mucocele, we also performed electron microscopy to examine sinonasal mucosa tissue samples. This analysis revealed an absence of one of the microtubule doublets in three of the outer doublets of the axoneme (figure 2). To rule out etiologies such as cystic fibrosis and Kartagener syndrome, we obtained a chest x-ray and performed a chloride-in-sweat test; findings were normal. Our final diagnosis was isolated ciliary dysfunction.

The patient underwent endoscopic sinus surgery with a medial inferior left endoscopic maxillectomy. The mucoceles were drained via a sublabial approach and endoscopic right mucopyocele drainage.

The surgical outcome was satisfactory. Follow-up CT performed 18 months later detected no sinonasal disease.

Discussion

The presence of mucoceles in both maxillary sinuses is a rare presentation, accounting for only 4% of all reported cases of mucocele.2,3 When bilateral cases do occur, most are bilaterally symmetrical; asymmetrical sinus involvement with or without orbital complications has rarely been reported.2,3 Maxillary sinus involvement is also uncommon, accounting for less than 10% of all mucocele cases.2,3

Many bilateral mucoceles are pseudomucoceles that arise as a result of mucus abnormalities or primary ciliary dysfunction, as is the case with cystic fibrosis or Kartagener syndrome; this presentation is commonly associated with a rhinobronchial syndrome.2,3 Our patient presented without chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms. Because of her atypical presentation, we suspected ciliary dysfunction. Analysis of the sinus mucosa under electron microscopy found alterations of the cilia, which explained the underlying pathophysiology of the mucocele formation.5 To the best of our knowledge, such a cause of bilateral maxillary mucoceles has not been previously described in the literature.

As far as we know, only 1 case of mucocele secondary to primary ciliary dyskinesia has been reported.1 In that case, a 12-month-old boy who presented with such a mucocele and ipsilateral proptosis was found to have an absence of the inner dynein arms linking the microtubule doublets. Our case involved alterations of the outer microtubules. The variations of the ciliary alterations may explain the different clinical presentations in these two cases.

We suggest that in addition to endoscopy and imaging studies, otolaryngologists should consider performing electron microscopy and measuring levels of chloride in sweat in cases of bilateral or atypical mucocele formation (figure 3).

120 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

SPíNOLA-HERNáNdEz,

CASTELL-ROdRígUEz, PRAdO-CALLEROS, BRAvO-ESCOBAR, SAdEk-gONzáLEz

A B

Figure 1. A: Coronal CT shows the homogeneous isodense soft-tissue mass occupying both maxillary sinuses with bone remodeling of their walls, including the orbital floor. B: Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrates the hyperintense cystic masses in both maxillary sinuses and the expansion of the orbital floor.

Figure 2. Electron microscopy demonstrates the absence of an outer microtubule in three of the nine external doublets of the cilia (one of them is highlighted).

References

1. Berlucchi M, Maroldi R, Aga A, et al. Ethmoid mucocele: A new feature of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010;45(2):197-201.

2. Varghese L, John M, Kurien M. Bilateral asymmetric mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses: A first case report. Ear Nose Throat J 2004;83(12):834-5.

3. Chong AW, Prepageran N, Rahmat O, et al. Bilateral asymmetrical mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses with unilateral orbital complications. Ear Nose Throat J 2011;90(2):E13.

4. Thompson LD. Paranasal sinus mucocele. Ear Nose Throat J 2012;91(7):276-8.

5. Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ. The roles of cilia in developmental disorders and disease. Development 2006;133(21):4131-43.

MICROCOMPUTEd TOMOgRAPHy Of THE STAPES: WIdE-RANgINg dIMENSIONS

Continued from page 118

The major limitations of our study are that (1) we looked at specimens of only 10 crania (the 5 with the largest areas of mastoid pneumatization and the 5 with the smallest) and (2) we had no specific information about age, sex, or otologic history. Nevertheless, our study does have three distinct positive features: (1) the specimens represented the size extremes of mastoid pneumatization in 41 clinically ear-normal crania, (2) images of the stapes were obtained in situ, and thus any possible damage sustained during harvesting was precluded, and (3) bilateral symmetry of stapes features was checked. In conclusion, stapes heights and footplate lengths and widths in our study were consistent with those reported by Sim et al6 and others.2-4 Studying as few as 7 paired specimens, we found that bilateral symmetry was suggested for superstructure height and footplate length and found to be statistically significant for footplate width. We found no correlation between the stapes measurements and the size of mastoid pneumatization. The distribution of footplate widths may be bimodal, as reported by Sim et al, in that men have wider footplates than do women.6

References

1. Eysell A. Beiträge zur Anatomie des Steigbügels und seiner Verbindungen. Arch Ohrenheilk 1870;5:237-49.

2. Urbantschitsch V. Zur anatomie der Gehörknochelchen des Menschen. Arch Ohrenheilkunde 1876;11:1-10.

3. Dass R, Grewal BS, Thapar SP. Human stapes and its variations. I. General features. J Laryngol Otol 1966;80(1):11-25.

4. aWengen DF, Nishihara S, Kurokawa H, Goode RL. Measurements of the stapes superstructure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995;104(4 Pt 1):311-16.

5. Rousset J, Garetier M, Gentric JC, et al. Biometry of the normal stapes using stapes axial plane, high-resolution computed tomography. J Laryngol Otol 2014;128(5):425-30.

6. Sim JH, Röösli C, Chatzimichalis M, et al. Characterization of stapes anatomy: Investigation of human and guinea pig. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2013;14(2):159-73.

7. Swarts JD, Foley S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ. Mastoid geometry in a cross-section of humans from infancy through early adulthood with a confirmed history of otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012;76(1):137-41.

8. Chole RA, Sudhoff HH. Chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, and petrositis. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:1965-78.

9. Rodríguez-Vázquez JF. Development of the stapes and associated structures in human embryos. J Anat 2005;207(2):165-73.

10. Todd NW. Orientation of the manubrium mallei: Inexplicably widely variable. Laryngoscope 2005;115(9):1548-52.

11. Doube M, Kłosowski MM, Arganda-Carreras I, et al. BoneJ: Free and extensible bone image analysis in ImageJ. Bone 2010;47(6):1076-9.

12. Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9(7):671-5.

13. Kalter H. Teratology in the Twentieth Century Plus Ten. New York: Springer; 2010.

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 121 AN ABSENCE Of CILIA OUTER MICROTUBULES, AN ETIOLOgy NOT PREvIOUSLy RECOgNIzEd IN BILATERAL MUCOCELE

Figure 3. Flow chart shows our suggestion for the diagnosis of ciliary dysfunction.

Computational analysis of swallowing mechanics after surgery for obstructive sleep apnea

Mark A. Ellis, MD; Mariah B. Pate, MD; Hugh D. Dorris, BA; William G. Pearson Jr., PhD; Jimmy J. Brown, DDS, MD

Abstract

Multilevel upper airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been shown to cause clinically significant dysphagia in some patients. We describe the cases of 2 adults with OSA who developed persistent dysphagia after multilevel upper airway surgery. Patient-specific computational analysis of swallowing mechanics (CASM) revealed absent pharyngeal shortening and aberrant tongue base retraction in both patients. These findings are consistent with the OSA surgical goal of enlarging the hypopharyngeal airway but likely contributed to our patients’ dysphagia. Patient-specific CASM allows for sensitive identification of swallowing mechanical dysfunction that might otherwise be overlooked, and it may be utilized in future head and neck surgery patients to analyze swallowing dysfunction associated with treatment.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder that affects between 5 and 14% of middle-aged adults.1 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first-line therapy for OSA; however, long-term compliance with CPAP is only 50 to 70%.2 Multilevel upper airway surgeries are often employed in OSA patients who do not respond to or who are unable to tolerate

From the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston (Dr. Ellis); and the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (Dr. Pate and Dr. Brown) and the Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy (Mr. Dorris and Dr. Pearson), Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta.

Corresponding author: Mark A. Ellis, MD, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, 135 Rutledge Ave., MSC 550, Charleston, SC 29425.

Email: ellismar@musc.edu

CPAP therapy. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is the most commonly performed upper airway surgery for OSA and is often used in conjunction with other sleep surgery techniques. Unfortunately, OSA surgical techniques are associated with several untoward outcomes, including clinically significant dysphagia, which has been reported in 13 to 36% of patients.3

The primary sleep surgeon (J.J.B.) at our academic institution employs a variety of sleep surgery techniques. Most patients have evidenced significant improvement in their OSA symptomatology over short- and long-term intervals, but a subset of patients complains of clinically significant dysphagia after surgery. We describe the cases of 2 adults with OSA who developed persistent dysphagia after OSA surgery, and we analyze their postoperative swallowing mechanics using patient-specific computational analysis of swallowing mechanics (CASM).

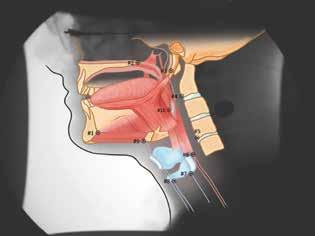

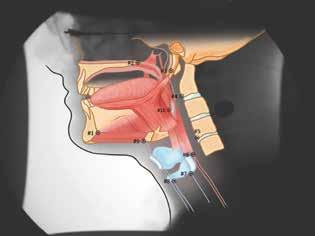

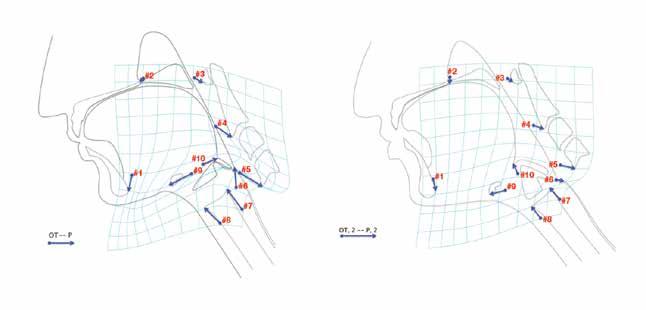

Patient-specific CASM allows for visualization of swallowing mechanics (hyoid movement, laryngeal elevation, tongue base retraction, and pharyngeal shortening) using eigenvectors that characterize the relative contribution of each element of swallowing mechanics. CASM is a multivariate morphometric analysis of coordinates that is used to map muscle groups that underlie oropharyngeal swallow mechanics represented in the lateral-view modified barium swallow (MBS) imaging at 30 frames per second (figure 1).4,5

For patient-specific CASM, these anatomic coordinates are collected for each frame of the oropharyngeal swallow using a semiautomated MATLAB tracker tool.6 Coordinate data are then uploaded into integrated MorphoJ software, and a procrustean superimposition (a mathematical realignment of all coordinates)

122 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

is performed to control for image rotation and patient movement.7 A canonical variate analysis with post hoc discriminant function analysis is performed to statistically evaluate shape change representing the covariate components of swallowing mechanics.

In this article, the eigenvectors of this analysis are reported to demonstrate the patient-specific mechanics associated with surgical intervention.8

Case reports

Patient 1. The first patient was a 49-year-old woman with diagnosed OSA who demonstrated CPAP intolerance and desired surgical intervention. Preoperative polysomnography revealed a baseline apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 41 and an Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) score of 22. Physical examination revealed a body-mass index (BMI) of 44.2 and a Friedman class III tongue position. The fiberoptic nasal endoscopy with modified Müller maneuver (FNMM) scores were 4/4, 4/4, and 3/4 for retropalatal, retrolingual, and lateral pharyngeal wall collapse, respectively.

The patient underwent UPPP, relocation pharyngoplasty, transoral robotic surgery tongue base resection, and tracheotomy. She was decannulated on postoperative day 17. After surgery, she complained of persistent dysphagia with nasal regurgitation and globus sensation.

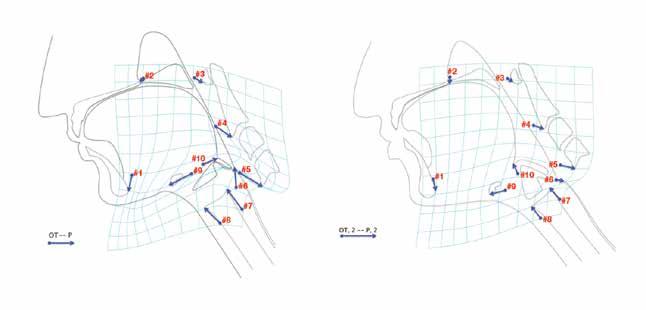

An MBS study performed 8 months after surgery revealed a penetration aspiration scale (PAS) score of 2 (penetration without aspiration). Findings were otherwise unremarkable, including complete velopharyngeal valve closure. Patient-specific CASM was performed on the MBS imaging. When visually compared with normative values for CASM in nonsurgical controls (figure 2, A), our patient’s analysis (figure 2, B) demonstrated an absent pharyngeal shortening (vector #6)

Volume 97, Number 4-5 www.entjournal.com 125 COMPUTATIONAL ANALySIS Of SWALLOWINg MECHANICS AfTER SURgERy fOR OBSTRUCTIvE SLEEP APNEA

Figure 1. Coordinates are used to map the swallowing mechanics in the suprahyoid muscle group (#9 to the mandible [vectors #1 to #3]) and in the thyrohyoid (#8 to #9), the stylopharyngeus (#7 to #3), the palatopharyngeus (#6 to #2), and the styloglossus and hyoglossus (#10 to #3) muscles. It also shows the movement of three skeletal levers, including the skull base (#2 to #3), the mandible (#1 to #3), and vertebrae (#3, #4, and #5). Illustrations courtesy of Mark A. Ellis, MD, and William G. Pearson Jr., PhD.

A B

Figure 2. Patient 1. A: Vectors in nonsurgical controls show normal swallowing mechanics. B: Vectors in patient 1 demonstrate an absent pharyngeal shortening (vector #6) and an aberrant (superior vs. posterior) tongue base retraction (#10). (OT = oral transport; P = pharyngeal swallowing; 1 = patient 1).

and an aberrant (superior vs. posterior) tongue base movement (vector #10).

Patient 2. The second patient was a 23-year-old man with OSA who could not tolerate CPAP due to claustrophobia. Preoperative polysomnography revealed a baseline AHI of 7.3 and an ESS score of 17. Physical examination revealed a BMI of 31.6 and a Friedman class III tongue position. The FNMM scores were 4/4, 4/4, and 3/4 for retropalatal, retrolingual, and lateral pharyngeal wall collapse, respectively.

The patient underwent UPPP, relocation pharyngoplasty, transoral robotic surgery tongue base resection, and tracheotomy. He was decannulated on postoperative day 4. After surgery, he complained of nasal regurgitation with liquids and clinically significant dysphagia.

An MBS study performed 2 months after surgery revealed a PAS score of 2. Findings were otherwise unremarkable, including complete velopharyngeal valve closure. Patient-specific CASM was performed on the MBS imaging. When visually compared with normative values for CASM in nonsurgical controls (figure 3, A), our patient’s analysis (figure 3, B) demonstrated an absent pharyngeal shortening (vector #6) and an aberrant (superior vs. posterior) tongue base retraction (vector #10).

Discussion

We used computational analysis to examine swallowing mechanics and structural changes in postoperative OSA surgery patients. It is interesting that our 2 patients demonstrated similar changes in swallowing mechanics—namely the absence of pharyngeal shortening and the presence of aberrant movement of the tongue base in the superior vs. posterior direction compared with swallowing mechanics of nonsurgical patients. There were no significant differences in laryngeal elevation and hyoid excursion between our 2 patients and normal controls.

Relocation pharyngoplasty is a modified UPPP technique that includes tonsillectomy, removal of supratonsillar mucosa and adipose tissue, suturing of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle to the anterior tonsil pillar, and suturing of the posterior pillar to the anterior pillar.9 The palatopharyngeus muscle resides within the posterior pillar mucosa and aids in pharyngeal shortening.10

Our preliminary data suggest that relocation pharyngoplasty alters the function of the palatopharyngeus muscle by tethering it to the anterior tonsil pillar. In normal swallowing, the pharynx shortens, allowing the pharyngeal esophageal segment to engulf the bolus head. In these patients, the middle pharyngeal constrictor

126 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal April/May 2018

ELLIS, PATE, dORRIS, PEARSON, BROWN

A B

Figure 3. Patient 2. A: Vectors in nonsurgical controls show normal swallowing mechanics. B: Vectors in patient 2 demonstrate an absent pharyngeal shortening (vector #6) and an aberrant (superior vs. posterior) tongue base retraction (#10). (OT = oral transport; P = pharyngeal swallowing; 2 = patient 2).

muscle appears to compensate by collapsing toward the tongue base to help drive the bolus through the pharyngeal esophageal segment.

Preoperatively, both patients demonstrated 4/4 retrolingual collapse on FNMM and were deemed candidates for transoral robotic surgery tongue base reduction. CASM results indicated a reduction in tongue base retraction, which is consistent with the surgery’s goal of stabilizing the hypopharyngeal airspace and relieving tongue base obstruction. Reduced tongue base retraction has been associated with incomplete bolus clearance in head and neck cancer patients, thus compromising airway safety during swallowing.11

The PAS score for both patients was 2, indicating that the bolus penetrated the larynx but was ejected without aspiration. Findings of a recent study suggested that reduced tongue base retraction impairs epiglottic inversion, which acts as an element of airway protection.4 Since our patients had reduced tongue base retraction, they likely had associated reduced epiglottic inversion and thus poorer protection of their airway and a greater likelihood of penetrating (PAS score of 2, penetration).

Li and Lee reported “no serious dysphagia,” including no nasal regurgitation, 3 months postoperatively in their initial cohort of 10 patients who underwent relocation pharyngoplasty.9 They did not report how dysphagia was measured or determined. By objective measures in our study, the procedure did not result in serious dysphagia; a PAS score of 2, while not normal, may be considered to be within functional limits. However, in view of patients’ complaints of postoperative swallowing difficulty, our concern is whether relocation pharyngoplasty impairs swallowing mechanics.

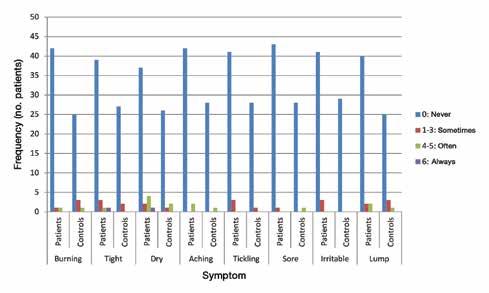

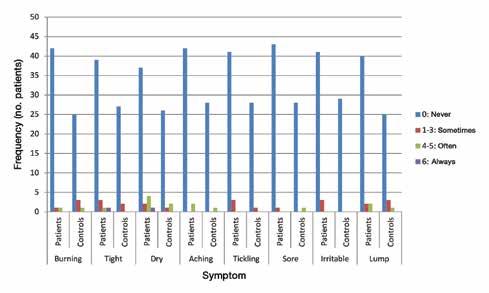

The current standard of care does not include a preoperative MBS swallowing study for OSA patients. In the absence of preoperative MBS swallowing studies, impaired swallowing mechanics before treatment cannot be ruled out. However, since dysphagia symptoms are newly onset and the altered mechanics of swallowing are consistent with the anatomic changes of the procedure, it is likely that the OSA surgery resulted in impaired swallowing mechanics. Future directions for research include preoperative and postoperative MBS imaging to determine if these alterations in swallowing mechanics are consistent with this procedure.