Clinical outcome of revision cartilage

tympanoplasty

Persistent local demucosalization after endoscopic sinus surgery: A report of 3 cases

Desmoid tumors of the head and neck: Two decades in a single tertiary care unit and review of the literature

Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: An Indian perspective

www.entjournal.com A Vendome Publication OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 10-11

Nasal Septal Perforation Prosthesis

The new two-piece magnetically coupled solution for non-surgical closure Round Oval www.inhealth.com We speak ENT ©2017 InHealth Technologies Manufactured by Freudenberg Medical, LLC (161010.06) The voice of experience since 1978

Magnetic4

3Closure

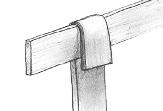

The #1 Most Profitable Ancillary Service for Private Practice ENTs

Y our peers wanted to share an update since adding a FYZICAL Balance Center to their ENT practice:

“This is the single best thing we’ve ever done in our practice. We can’t comprehend why an otolaryngologist would not do this. It’s a no-brainer and it’s taking our profession by storm."

ü We're seeing 40 - 4 5 patients per day for balanc e therapy only.

ü Our hearing aid sales have increased 59%.

ü Our total patient visits are up 15% for new patients and 5% for return patients.

ü Our allergy / immunotherapy population has grown 20% since joining.

"We couldn’t be more

our future.

with FYZICAL.

Discover the systems and procedures behind this opportunity. Call 941-227-4314 to register now or learn more about this event.

*Limited seating and only open to those with open territories*

Discover more at www.BusinessofBalance.com

"We can't stress enough how amazing of an opportunity this really is. You will grow every part of your practice through this vehicle."

excited about

Get in touch

You absolutely, positively, 100% need to see for your own eyes what this can do for your practice before it’s too late.”

Explore FYZICAL Balance at OTO Game Changer

Tuscaloosa ENT Group

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Editor-in-Chief

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Professor and Chairman, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Senior Associate Dean for Clinical Academic Specialties, Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, PA

Jean Abitbol, MD

Jason L. Acevedo, MD, MAJ, MC, USA

Jack B. Anon, MD

Gregorio Babighian, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Bruce Benjamin, MD

Gerald S. Berke, MD

Michael J. Brenner, MD

Kenneth H. Brookler, MD

Karen H. Calhoun, MD

Steven B. Cannady, MD

Ricardo Carrau, MD

Swapna Chandran, MD

Chien Chen, MD

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Nicolle T. Clements, MS

Daniel H. Coelho, MD, FACS

David M. Cognetti, MD

James V. Crawford, MD

David H. Darrow, MD, DDS

Rima Abraham DeFatta, MD

Robert J. DeFatta, MD, PhD

Hamilton Dixon, MD

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Mainak Dutta, MS, FACS

Russell A. Faust, PhD, MD

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Charles N. Ford, MD

Paul Frake, MD

Marvin P. Fried, MD

Richard R. Gacek, MD

Andrea Gallo, MD

Frank Gannon, MD

Emilio Garcia-Ibanez, MD

Soha Ghossani, MD

William P. R. Gibson, MD

David Goldenberg, MD

Jerome C. Goldstein, MD

Richard L. Goode, MD

Samuel Gubbels, MD

Reena Gupta, MD

Joseph Haddad Jr., MD

Missak Haigentz, MD

Christopher J. Hartnick, MD

Mary Hawkshaw, RN, BSN, CORLN

Garett D. Herzon, MD

Thomas Higgins, MD, MSPH

Jun Steve Hou, MD

John W. House, MD

Glenn Isaacson, MD

Steven F. Isenberg, MD

Stephanie A. Joe, MD

Shruti S. Joglekar, MBBS

Raleigh O. Jones, Jr., MD

Petros D. Karkos, MD, AFRCS, PhD, MPhil

David Kennedy, MD

Seungwon Kim, MD

Robert Koenigsberg, DO

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Stilianos E. Kountakis, MD, PhD

John Krouse, MD

Ronald B. Kuppersmith, MD, MBA, FACS

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Robert S. Lebovics, MD, FACS

Keat-Jin Lee, MD

Donald A. Leopold, MD

Steve K. Lewis, BSc, MBBS, MRCS

Daqing Li, MD

Robert R. Lorenz, MD

John M. Luckhurst, MS, CCC-A

Valerie Lund, FRCS

Karen Lyons, MD

A.A.S. Rifat Mannan, MD

Alexander Manteghi, DO

Richard Mattes, PhD

Brian McGovern, ScD

William A. McIntosh, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Oleg A. Melnikov, MD

Albert L. Merati, MD, FACS

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ron B. Mitchell, MD

Steven Ross Mobley, MD

Jaime Eaglin Moore, MD

Thomas Murry, PhD

Ashli K. O’Rourke, MD

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

J. David Osguthorpe, MD

Robert H. Ossoff, DMD, MD

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Michael M. Paparella, MD

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD

Arthur S. Patchefsky, MD

Meghan Pavlick, AuD

Spencer C. Payne, MD

Kevin D. Pereira, MD, MS (ORL)

Nicolay Popnikolov, MD, PhD

Didier Portmann, MD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Matthew J. Provenzano, MD

Hassan H. Ramadan, MD, FACS

Richard T. Ramsden, FRCS

Gabor Repassy, MD, PhD

Dale H. Rice, MD

Ernesto Ried, MD

Alessandra Rinaldo, MD, FRSM

Joshua D. Rosenberg, MD

Allan Maier Rubin, MD, PhD, FACS

John S. Rubin, MD, FACS, FRCS

Amy L. Rutt, DO

Anthony Sclafani, MD, FACS

Raja R. Seethala, MD

Jamie Segel, MD

Moncef Sellami, MD

Michael Setzen, MD, FACS, FAAP

Douglas M. Sidle, MD

Herbert Silverstein, MD

Jeffrey P. Simons, MD

Raj Sindwani, MD, FACS, FRCS

Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

William H. Slattery III, MD

Libby Smith, DO

Jessica Somerville, MD

Thomas C. Spalla, MD

Matthew Spector, MD

Paul M. Spring, MD

Brendan C. Stack, Jr., MD, FACS

James A. Stankiewicz, MD

Jun-Ichi Suzuki, MD

David Thompson, MD

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Helga Toriello, PhD, FACMG

Ozlem E. Tulunay-Ugur, MD

Galdino Valvassori, MD

Emre Vural, MD

Donald T. Weed, MD, FACS

Neil Weir, FRCS

Kenneth R. Whittemore, MD

David F. Wilson, MD

Ian M. Windmill, PhD

Ian J. Witterick, MD,MSc, FRCSC

Richard J. Wong, MD

Naoaki Yanagihara, MD

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Anthony Yonkers, MD

Mark Zacharek, MD

Joseph Zenga, MD

Liang Zhou, MD

CLINIC EDITORS

Dysphagia

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Facial Plastic Surgery

Anthony P. Sclafani, MD, FACS

Geriatric Otolaryngology

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD, FACS

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Head and Neck

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Reena Gupta, MD

Imaging

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Laryngoscopic

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Otoscopic

John W. House, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Pathology

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Pediatric Otolaryngology

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Rhinoscopic

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Special Topics

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Thyroid and Parathyroid

David Goldenberg, MD

330 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

Balloon dilation for Eustachian tube dysfunction

The superior, durable results your patients deserve.

With the safety you can count on.

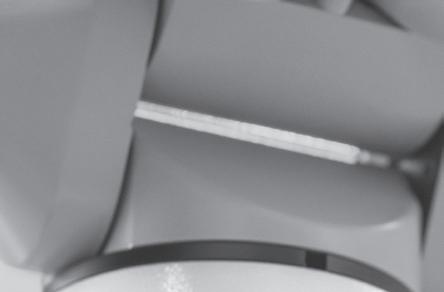

A randomized, controlled trial comparing balloon dilation with ongoing medical therapy as treatment for persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction reported zero complications and significant symptom improvement through 12 months for patients treated with the XprESS™ ENT Dilation System.1

dilation SUPERIOR to medical management

1 Meyer TA, O’Malley E, Schlosser RJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of balloon dilation as a treatment for persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction with 1-year follow-up. Otol Neurotol. 2018. DOI: 10.1097/

MAO.0000000000001853

INDICATIONS FOR USE: To access and treat the maxillary ostia/ethmoid infundibula in patients 2 years and older, and frontal ostia/recesses and sphenoid sinus ostia in patients 12 years and older using a transnasal approach. The bony sinus outflow tracts are remodeled by balloon displacement of adjacent bone and paranasal sinus structures. To dilate the cartilaginous portion of the Eustachian tube for treating persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction in patients 18 years and older using a transnasal approach.

Please see Instructions for Use (IFU) for a complete listing of warnings, precautions, and adverse events as well as cleaning, sterilizing and care for surgical instruments.

CAUTION: Federal (USA) law restricts these devices to sale by or on the order of a physician.

ENTELLUS MEDICAL and XPRESS are trademarks of Entellus Medical, Inc.

DURABLE symptom improvement through 12 months

NEW CLINICAL DATA Read more at: go.ent.stryker.com/ETDRCT1YearData

©2018 Entellus Medical, Inc. 1738-762 rA 07/2018

Balloon Dilation (N=28) Control (N=27) Baseline (N=54) 6 Weeks (N=51) 3 Months (N=52) 6 Months (N=51) 12 Months (N=49) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.6 2.1 2.12.1 2.1 MILD (NO PROBLEM) MODERAT E SEVERE M EAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE MEAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE ∆= -2.9±1.4 ∆= -0.6±1.0 p<0.0001 p<0.0001

follow-up periods BaselineFollow-up Baseline Follow-up ET balloon

Balloon Dilation (N=28) Control (N=27) Baseline (N=54) 6 Weeks (N=51) 3 Months (N=52) 6 Months (N=51) 12 Months (N=49) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.6 2.1 2.12.1 2.1 MILD (NO PROBLEM) MODERAT E SEVERE M EAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE MEAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE ∆= -2.9±1.4 ∆= -0.6±1.0 p<0.0001

periods BaselineFollow-up Baseline Follow-up ET balloon

for change from baseline to all

p<0.0001 for change from baseline to all follow-up

dilation with XprESS is SAFE

0 % COMPLICATION RATE

Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl., Philadelphia, PA 19107 entjournal@phillyent.com Ph: 215-732-6100

Managing Editor Linda Zinn

Manuscript Editors Martin Stevenson and Wayne Kuznar

Associate Editor, Reader Engagement Megan Combs

Creative Director Eric Collander

National Sales Manager Mark C. Horn mhorn@vendomegrp.com Ph: 480-895-3663

Traffic Manager Eric Collander

Please send IOs to adtraffic@vendomegrp.com

All ad materials should be sent electronically to: https://vendome.sendmyad.com

Customer Service/Subscriptions

www.entjournal.com/subscribe Ph: 888-244-5310 email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com

Reuse Permissions Copyright Clearance Center info@copyright.com Ph: 978-750-8400 Fax: 978-646-8600

Chief Executive Officer Jane Butler

Chief Marketing Officer Dan Melore

Vice President, Finance Bill Newberry

Vice President, Custom Media Jennifer Turney Director, Circulation Rachel Beneventi

ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal (ISSN: Print 0145-5613, Online 1942-7522) is published 9 times per year in Jan/Feb, Mar, Apr/May, June, July, Aug, Sept, Oct/ Nov and Dec, by Vendome Group, LLC, 237 West 35th Street, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10001-1905.

©2018 by Vendome Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal may be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast in any form or in any media without prior written permission of the publisher. To request permission to reuse this content in any form, including distribution in education, professional, or promotional contexts or to reproduce material in new works, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at info@ copyright.com or 978.750.8400.

EDITORIAL: The opinions expressed in the editorial and advertising material in this issue of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal are those of the authors and advertisers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher, editors, or the staff of Vendome Group, LLC. ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed and Current Contents/Clinical Medicine and Science Citation Index Expanded. Editorial offices are located at 812 Huron Rd., Suite 450, Cleveland, OH 44115. Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.editorialmanager.com/entjournal. Instructions for Authors are available at www.entjournal.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For questions about a subscription or to subscribe, please contact us by phone: 888-244-5310; or email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com Individual subscriptions, U.S. and possessions: 1 year $225, 2 years $394; International: 1 year $279, 2 years $488; Single copies $28; outside the U.S., $40.

POSTMASTER: send address changes to Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, PO Box 11404 Newark, NJ 07101-4014.

ENT-Ear,

332 www.entjournal.com

Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

ADVERTISER

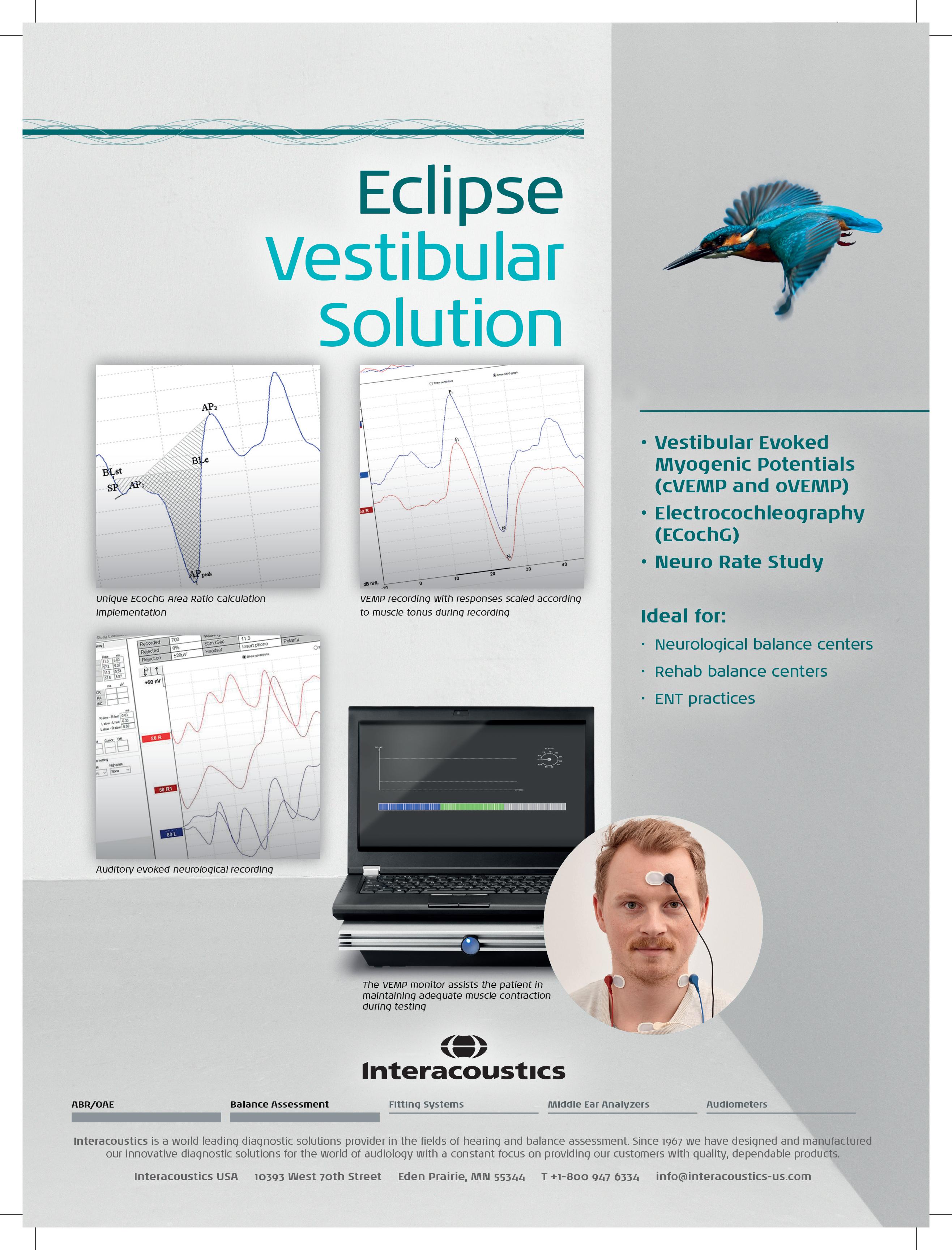

Pages Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC ......... 351, 352 CANT Corp. 337 Carl Zeiss 343 Compulink .................................. 368, CVR3 Entellus Medical ............................ 331, 369 Fyzical ........................................... 329, 370 InHealth Technologies CVR2 Interacoustics 333 Lumenis ................................................. 371 McKeon Products............... 345, 372, CVR4 Medtronic 335, 341 Novartis 355, 356 Optim LLC 373 Reliance Medical ................................... 374 Sinoptim ................................................ 375 Spectrum Audiology 339 Stryker 376

INDEX

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

349 Clinical outcome of revision cartilage tympanoplasty

Pei-Yin Wei, MD; Chia-Hui Chu, MD, MPH; Mao-Che Wang, MD, PhD

354 Persistent local demucosalization after endoscopic sinus surgery: A report of 3 cases

Conner J. Massey, MD; Menka M. Sanghvi, MD; Thomas R. Troost, MD, PhD; Vijay K. Anand, MD; Ameet Singh, MD

362 Desmoid tumors of the head and neck: Two decades in a single tertiary care unit and review of the literature

Aleksi Schrey, MD, PhD; Maria Gardberg, MD, PhD; Riitta Parkkola, MD, PhD; Ilpo Kinnunen, MD, PhD

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

E1 Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: An Indian perspective

Swati Agrawal, MS, DNB; Sandeep Arora, MS, DNB; Nishi Sharma, MS, DNB

E7 Anxiety and depression in patients with sudden one-sided hearing loss

Fatih Arslan, MD; Emre Aydemir, MD; Yavuz Selim Kaya, MD; Hasan Arslan, MD; Abdullah Durmaz, MD

E11 Serum levels of oxidative stress indicators and antioxidant enzymes in Bell palsy

Nazim Bozan, MD; Ömer Faruk Kocak, MD; Canser Yılmaz Demir, MD;

Mehmet Emre Dinc, MD; Koray Avcı, MD; Halit Demir, PhD; Ahmet Faruk Kıroglu, MD

E15 Paraneoplastic syndrome or metastatic sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma?

Clinical conundrum

Panagiotis Kerezoudis, MD;

Patrick R. Maloney, MD; Brandon McCutcheon, MD, MPP; Jeffrey Janus, MD; Mark Jentoft, MD; Timothy Kaufmann, MD; Daniel Honore Lachance, MD;

Jamie J. Van Gompel, MD; Mohamad Bydon, MD

E19 Risk of developing sudden sensorineural hearing loss in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: A population-based study

Yao-Te Tsai, MD; Ku-Hao Fang, MD; Yao-Hsu Yang, MD, MSc; Meng-Hung Lin, PhD; Pau-Chung Chen, MD, PhD; Ming-Shao Tsai, MD; Cheng-Ming Hsu, MD

E28 Primary parapharyngeal leiomyosarcoma: A case report

Luca Giovanni Locatello, MD; Jano Maria De Cesare, MD; Cecilia Taverna, MD; Oreste Gallo, MD

E32 A rare case of coexisting lacrimal sac adenocarcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma

Tsutomu Nomura, MD, DDS, PhD; Daisuke Maki, MD; Fumihiko Matsumoto, MD, PhD; Taisuke Mori, DDS, PhD; Seichi Yoshimoto, MD, PhD

E36 Long-term use of Le Fort I osteotomy for the management of nasopharyngeal rhinosporidiosis: A case series

Vikram Shetty, DNB; Akshaya Kulkarni, MDS; Suman Banerjee, MDS

E44 The effect of zoledronic acid on middle ear osteoporosis: An animal study

Ozgur Surmelioglu, MD; Feyha Kahya Aydogan, MD; Suleyman Ozdemir, MD; Ozgur Tarkan, MD; Aysun Uguz, MD; Ulku Tuncer, MD; Lutfi Barlas Aydogan, MD

334 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018 EDITORIAL OFFICE Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS, Editor-in-Chief • 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl. • Philadelphia, PA 19107 CONTENTS OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 10-11

DEPARTMENTS 332 Advertiser Index 336 ENT Journal Online 338 Guest Editorial 340 Otoscopic Clinic 342 Imaging Clinic 346 Pathology Clinic 347 Thyroid and Parathyroid Clinic E49 Laryngoscopic Clinic E51 Rhinoscopic Clinic

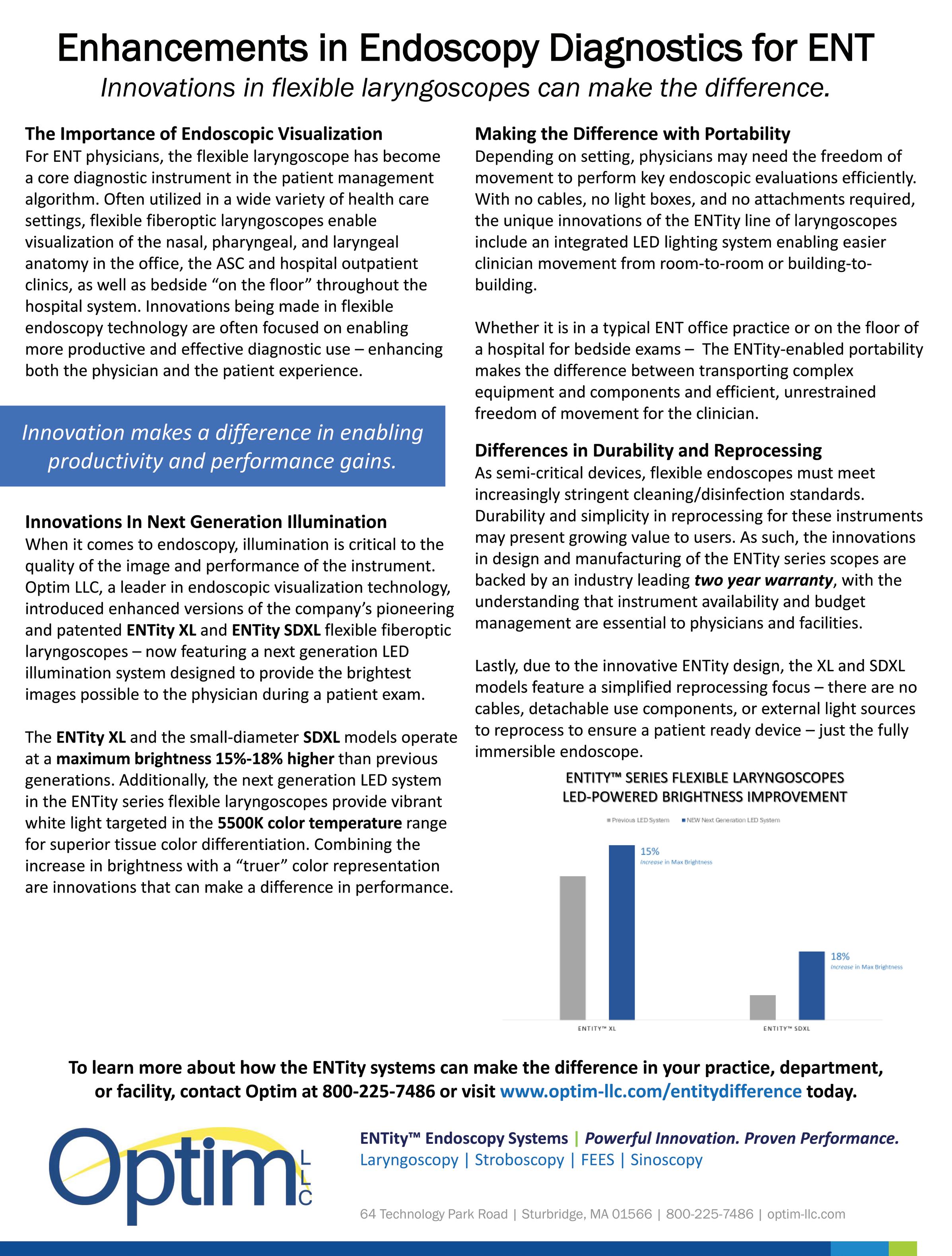

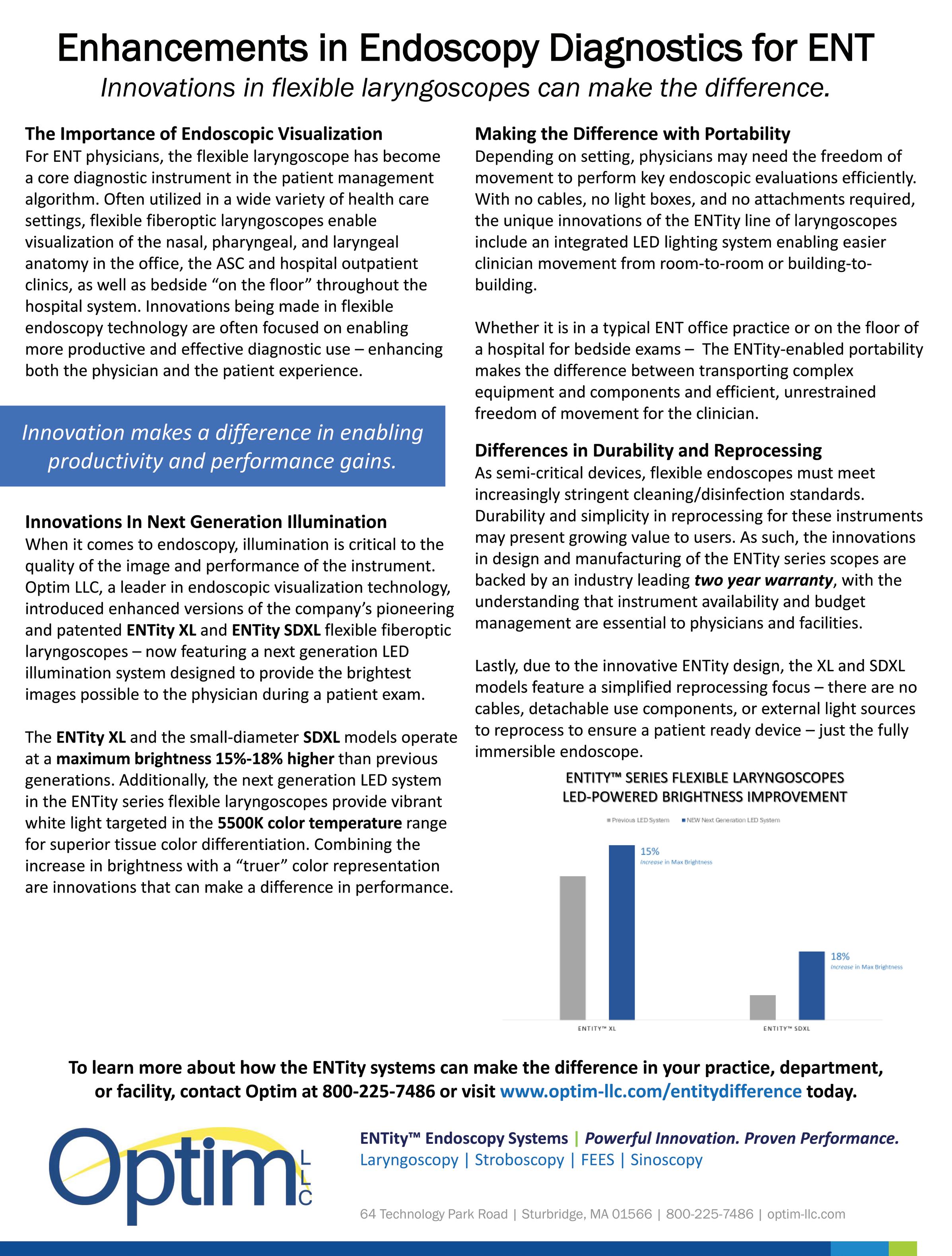

IRRIGATION. SUCTION. SYNCHRONIZATION.

Now there’s a better way to provide saline washes. The HydroCleanse™ Sinus Wash Delivery System from Medtronic combines pressurized sinus irrigation with builtin suction capability for a more efficient procedure. Disposable and easy to use, it allows you to irrigate the sinuses while limiting pooling and effluent discharge.

§ Disposable and easy to use

§ 360° fan spray

§ Pressurized saline irrigation

§ Built-in suction capability

§ Choice of angled catheter tips

HydroCleanse™ Sinus Wash Delivery System

IMPROVE THE SALINE WASH EXPERIENCE. CHOOSE HYDROCLEANSE.

Rx only. Refer to product instruction manual/package insert for instructions, warnings, precautions and contraindications.

For further information, please call Medtronic ENT at 800.874.5797 or consult Medtronic’s website at www.medtronicent.com

© 2018 Medtronic. All rights reserved. Medtronic, Medtronic logo and Further, Together are trademarks of Medtronic. All other brands are trademarks of a Medtronic company. UC201902765 EN 07.2018

JOURNAL ONLINE

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal's website is easy to navigate and provides readers with more editorial content each month than ever before. Access to everything on the site is free of charge to physicians and allied ENT professionals. To take advantage of all our site has to offer, go to www.entjournal. com and click on the “Registration” link. Once you have filled out the brief registration form, you will have full access. Explore and enjoy!

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: An Indian perspective

Swati Agrawal, MS, DNB; Sandeep Arora, MS, DNB; Nishi Sharma, MS, DNB

Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (IFRS) is a fatal disease of the nose and paranasal sinuses that typically affects immunocompromised patients. Data on this disorder, which is rare and difficult to diagnose, are lacking in the literature. We collected comprehensive data from 9 patients (7 males, 2 females) with a mean age of 34 years (range: 6 to 58) with IFRS who were treated at our center and examined the factors associated with successful treatment. The parameters examined were patient demographics, disease characteristics, clinical course including surgical and medical therapy, treatment, fungal species involved, and long-term survival....

Anxiety and depression in patients with sudden one-sided hearing loss

Fatih Arslan, MD; Emre Aydemir, MD;

Yavuz Selim Kaya, MD; Hasan Arslan, MD; Abdullah Durmaz, MD

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss is a hearing loss of >30 dB in at least three consecutive frequencies that occurs in 3 days. The aim of this study was to investigate anxiety and depression caused by sudden, idiopathic, one-sided hearing loss. The levels of anxiety and depression in patients with this type of hearing loss were determined using the Beck Anxiety Scale (BAS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) at the time of the patient’s first visit. In total, 56 patients (32 men and 24 women) with a mean age of 32.8 ± 9.9 years (range: 20 to 58 years) were selected as the patient group and 45 individuals without symptoms of anxiety and depression....

Serum levels of oxidative stress indicators and antioxidant enzymes in Bell palsy

Nazim Bozan, MD; Ömer Faruk Kocak, MD;

Canser Yılmaz Demir, MD; Mehmet Emre Dinc, MD; Koray Avcı, MD; Halit Demir, PhD;

Ahmet Faruk Kıroglu, MD

We conducted a prospective study to comparatively evaluate serum levels of malondialdehyde, an oxidative stress indicator, and the antioxidant enzymes glutathione, catalase, and superoxide dismutase in patients with Bell palsy. Our study population was made up of 30 patients with Bell palsy—15 men and 15 women, aged 25 to 68 years (mean: 50.4)—who were seen in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at a....

Paraneoplastic syndrome or metastatic sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma? Clinical conundrum

Panagiotis Kerezoudis, MD; Patrick R. Maloney, MD; Brandon McCutcheon, MD, MPP; Jeffrey Janus, MD; Mark Jentoft, MD; Timothy Kaufmann, MD; Daniel Honore Lachance, MD; Jamie J. Van Gompel, MD; Mohamad Bydon, MD

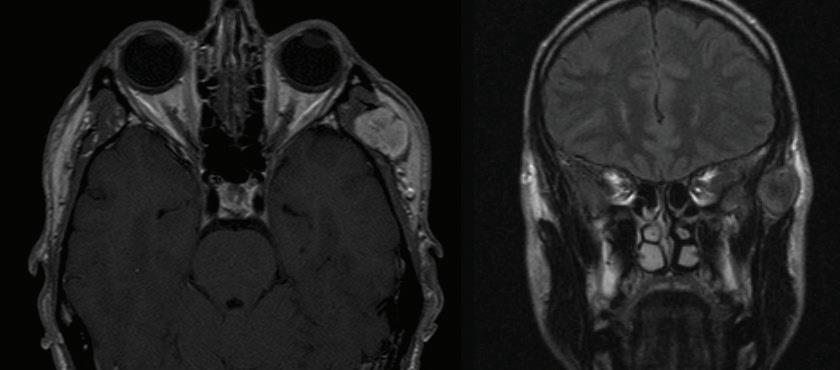

We report a case of a middle-aged woman with a diffuse, nonenhancing, progressively atrophic T2-hyperintense lesion involving the left frontotemporal lobes and insula found to be synchronous high-grade sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) after initial endonasal resection. In 2014, a 47-year old woman underwent resection of a left-sided high-grade ethmoidal neuroendocrine carcinoma after....

Risk of developing sudden sensorineural hearing loss in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: A population-based study

Yao-Te Tsai, MD; Ku-Hao Fang, MD; Yao-Hsu Yang, MD, MSc; Meng-Hung Lin, PhD; Pau-Chung Chen, MD, PhD; Ming-Shao Tsai, MD; Cheng-Ming Hsu, MD

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) has significant impact on quality of life. It may result from viral infection, but the relationship between hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and SSNHL remains uncertain. To investigate the risk of developing SSNHL in patients with HBV, we conducted a nationwide, population-based, retrospective cohort study from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. A total of 33,234 patients diagnosed with HBV infection and 132,936 control subjects without viral hepatitis....

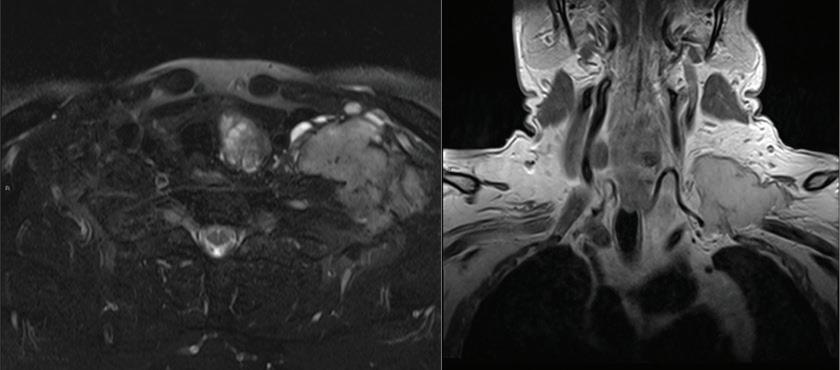

Primary parapharyngeal leiomyosarcoma: A case report

Luca Giovanni Locatello, MD; Jano Maria De Cesare, MD; Cecilia Taverna, MD; Oreste Gallo, MD

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare malignant soft-tissue tumor whose cells resemble smooth-muscle tissue. It has been reported to arise in different areas of the head and neck region. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the parapharyngeal space, however, is extremely rare, as only 4 cases have been previously reported to date. We describe the somewhat urgent case of a primary leiomyosarcoma of the right parapharyngeal space in a 30-year-old man. We also review the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges that clinicians....

336 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018 www.entjournal.com

A rare case of coexisting lacrimal sac adenocarcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma

Tsutomu Nomura, MD, DDS, PhD; Daisuke Maki, MD; Fumihiko Matsumoto, MD, PhD;

Taisuke Mori, DDS, PhD; Seichi Yoshimoto, MD, PhD

Lacrimal sac tumors are rare and difficult to diagnose. We present a case of coexisting lacrimal sac adenocarcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma in a 73-year-old woman who presented with swelling of the inner canthus. Biopsy identified the growth as an adenocarcinoma. After dissection...

Long-term use of Le Fort I osteotomy for the management of nasopharyngeal rhinosporidiosis: A case series

Vikram Shetty, DNB; Akshaya Kulkarni, MDS; Suman Banerjee, MDS

Rhinosporidiosis is a rare, chronic, granulomatous infection of the mucous membranes that mainly involves the nose and nasopharynx; it occasionally involves the pharynx, conjunctiva, larynx, trachea and, rarely, the skin. The characteristic clinical features of this disease include the formation of painless polyps in the nasal mucosa or the nasopharynx that bleed easily on touch. At our center, excision of the lesion with a Le Fort I osteotomy is carried out in patients....

The effect of zoledronic acid on middle ear

osteoporosis: An animal study

Ozgur Surmelioglu, MD; Feyha Kahya Aydogan, MD; Suleyman Ozdemir, MD; Ozgur Tarkan, MD; Aysun Uguz, MD; Ulku Tuncer, MD; Lutfi Barlas Aydogan, MD

Hearing function in older patients may be related to bone structure. We conducted an experiment to evaluate the effect of zoledronic acid on osteoporotic middle ear ossicles in an animal model. Our subjects were 19 female New Zealand....

ONLINE DEPARTMENTS

Laryngoscopic Clinic: Oropharyngeal histoplasmosis in an HIV-negative patient

Mohamedkazim Alwani, MD; Todd J. Wannemuehler, MD; Don-John Summerlin, DMD, MS; Marion E. Couch MD, PhD, FACS

Rhinoscopic Clinic: Endoscopic view of a posterior nasal and nasopharyngeal vascular plexus Dewey A. Christmas, MD; Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS; Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Reach More Patients.

People come in different shapes and sizes.The same piece of equipment does not fit them all.Make oropharyngeal surgery easier with a simple extension.The CANT Corporation has created the Dedo Extension that fits between the Mayo Stand and the Crowe-Davis mouth gag so that it can be adjusted to fit larger patients.The DE98-A mounts to the square-sided Mayo Stand,while the DE98-B fits the tubular-sided support. The Dedo Extension - a simple but effective solution.

• All oropharyngeal procedures using a Crowe-Davis mouth gag

Volume 97, Number 10-11 www.entjournal.com 337

ENT JOURNAL ONLINE

The Dedo Extension

The Crowe-Davis mouth gag

The

Mayo Stand

T&A’s

Uvuloplasty

Palatoplasty

Applicable Procedures •

•

•

337 • 233 • 2666, ext.9 • www.jrcant.com • PO Box 3522 • Lafa yette,LA 70502 Extension “DE98-B” also available for tubular support Extension “DE98-A” A B Dedo Ext 9 (ENT1/18/05) 1/19/05 1:51 PM Page 1

GUEST EDITORIAL

Two sides of the same coin

Many years ago, I opened an issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings Magazine. In it I found a column entitled, “Nobody asked me, but….” The intent of the column was to provide a venue for officers, often junior officers, to give commentary on current naval practice or policy. I am certain other publications had similar columns, but what struck me was that the column allowed for constructive, honest, and public critique of an organization, the U.S. Navy, that was not outwardly thought of as being inwardly reflective.

I don’t feel that our profession has the same reputation of not being inwardly reflective, although I can’t recall our profession having a readily available venue for constructive, honest, and public critique. With that in mind, I began to gather my thoughts on the challenges with which otolaryngologists must contend.

As background, I currently practice at Philadelphia ENT Associates, with an academic appointment at the Drexel University College of Medicine. My previous experience has been as a physician in the military, the Veterans Administration, academics, and private practice. My formal education in pursuit of my MBA and MPH also shape what I wish to focus on in this editorial: achieving financial sustainability and achieving economic sustainability

Currently, our practices face tremendous financial stress. Those in the public sector and those in academics are under the greater financial stress. The public sector and academic practices historically have not been prudent managers of their resources; academic practices have been particularly poor in achieving consistent financial sustainability. These practices form the safety net of our healthcare system, as well as the core of the resident and fellow training system.

With increasing enrollment in health exchanges and Medicaid, and facing reimbursement based on outcomes, many of these practices are ill equipped for the business challenges of reduced reimbursement combined with the increased cost of improving care. Academic programs that are financially unsustainable often are left to limp on—an “always sick, never dead” approach. It is intellectually difficult for these programs to institute the most basic revenue and cost-management systems, despite often having very fine business schools affiliated with the parent educational institution. They view themselves as “good stewards” of their patients’ health but fail to realize that stewardship requires the maintenance of a financially sustainable healthcare system. Prudent financial management can markedly improve disease management.

The issue for private practice is somewhat different, in my opinion. The challenge for private practice is to achieve a business that is economically sustainable within the community. Private practices, if not financially viable, will close. Generally, they have fairly good business processes in place, unlike many academic practices. The threat to these practices is the perception that the reporting requirements for MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) and MIPS (Merit-Based Incentive Payment System) are insurmountable for smaller groups; or worse, that the cost of reporting successfully is more expensive than the penalties.

If private practices begin to avoid participation in MACRA and MIPS, the lack of quality reporting will ultimately harm all of ENT, not just private

338 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

practice. Reimbursement will be based on the data returned through MACRA and MIPS; poor-quality data, or data based on a very narrow segment of physicians, will adversely impact the “value” assigned to the care otolaryngologists provide.

Further, in their drive for margin, these practices may lose sight of another important fact that is critical to economic sustainability. The otolaryngologist’s charge to the community is a social contract; failing to respect that social contract, with its benefits and obligations, by practicing in a manner no longer economically sustainable within the community, will result in the loss of the economic benefits gained by the social contract. The community is not just those patients who are cared for by the practice, but it also includes fellow otolaryngologists regionally and nationally. Narrowly defined interests usually result in similarly limited achievements.

While our Academy and specialty societies deserve much credit for the resources they have placed in their members’ hands, these resources could make an assertive and concerted effort to educate the public sector and academic practices on their respective fiscal and economic responsibilities and help them develop and use the skills in responsible stewardship of their roles.

Further, our Academy and specialty societies could make an assertive and concerted effort to educate those in private practice on the long-term importance of quality reporting and the need to engage with the Academy, so that the Academy can better provide guidance for successful participation and provide feedback to the public, public officials, and private/public payers on the burden current reporting requirements place on private practice. These actions by the Academy and specialty societies would serve to remind those in academics what their stewardship requires, and those in private practice of the benefits and obligations of their social contract with the community. Such action is essential to the continued high-quality care of our patients, and to the future success of our specialty.

Brian J. McKinnon, MD, MBA, MPH, FACS Associate Professor and Vice Chair

Department of Otolaryngology–

Head and Neck Surgery Associate Professor

Brian J. McKinnon, MD, MBA, MPH, FACS Associate Professor and Vice Chair

Department of Otolaryngology–

Head and Neck Surgery Associate Professor

Department of Neurosurgery

Drexel University College of Medicine

Philadelphia

Volume 97, Number 10-11 www.entjournal.com 339 GUEST EDITORIAL

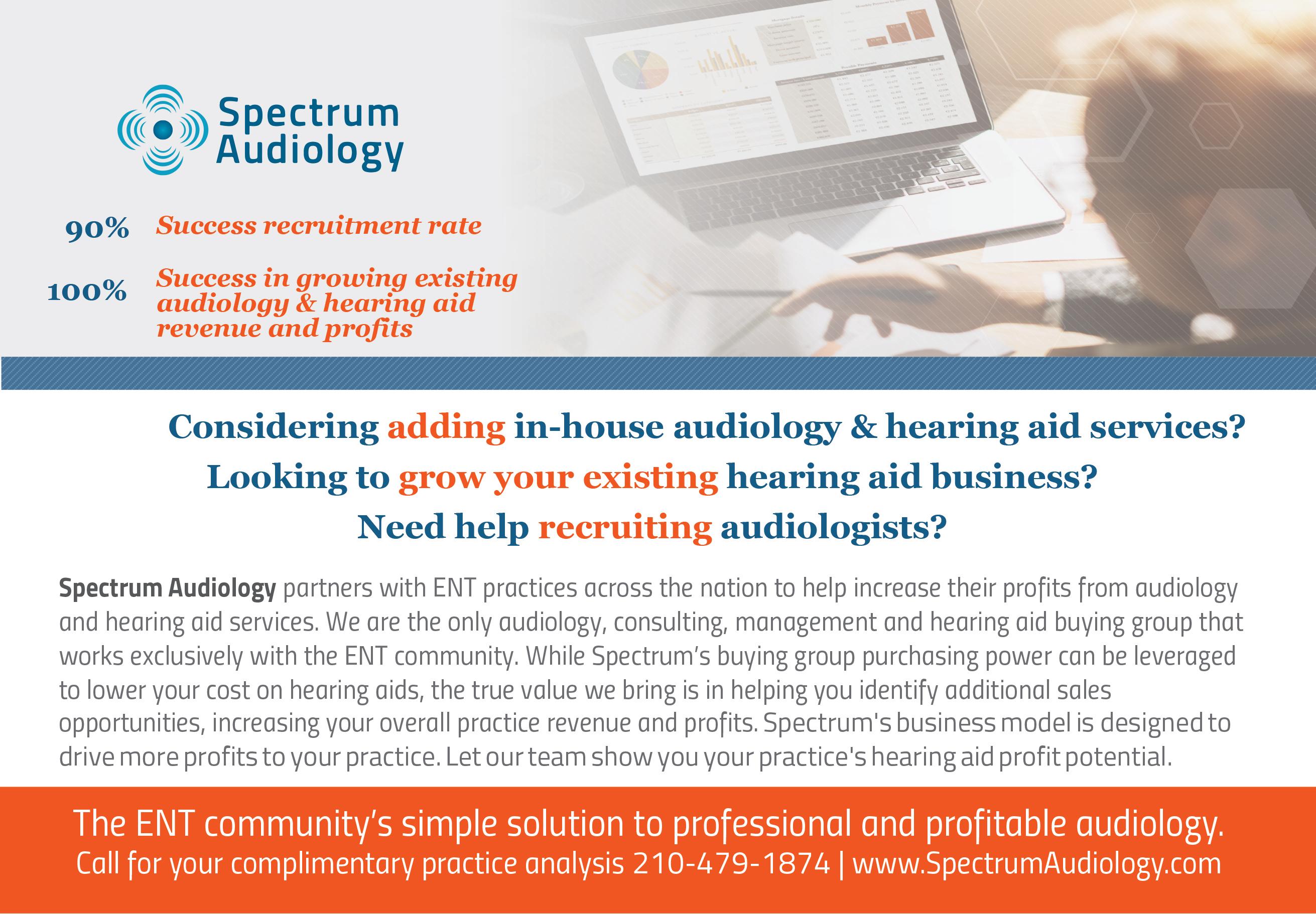

Iatrogenic external auditory canal cholesteatoma with mastoid erosion

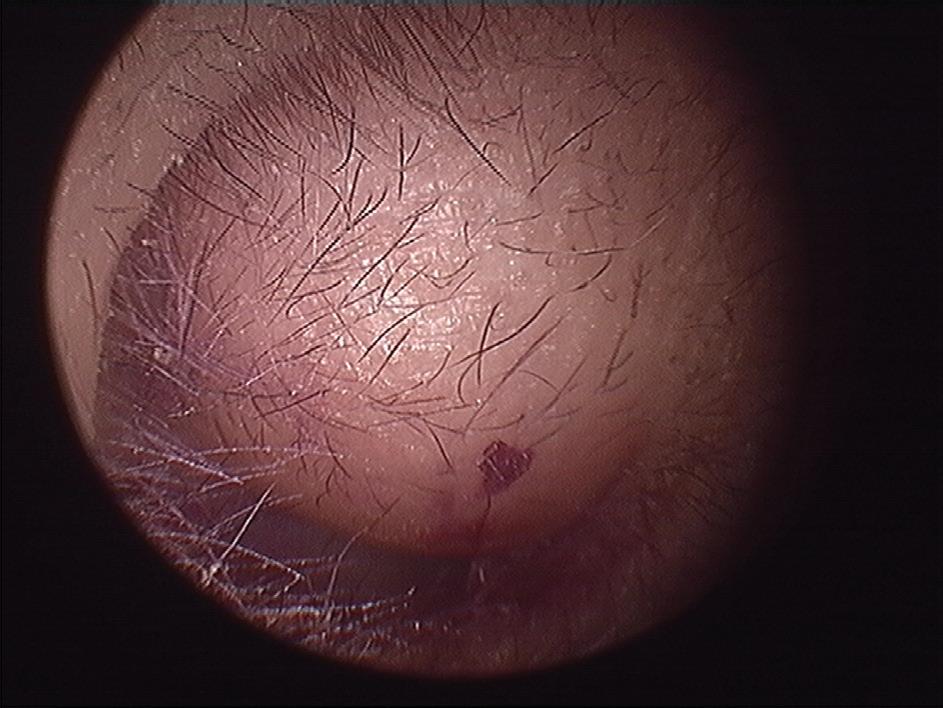

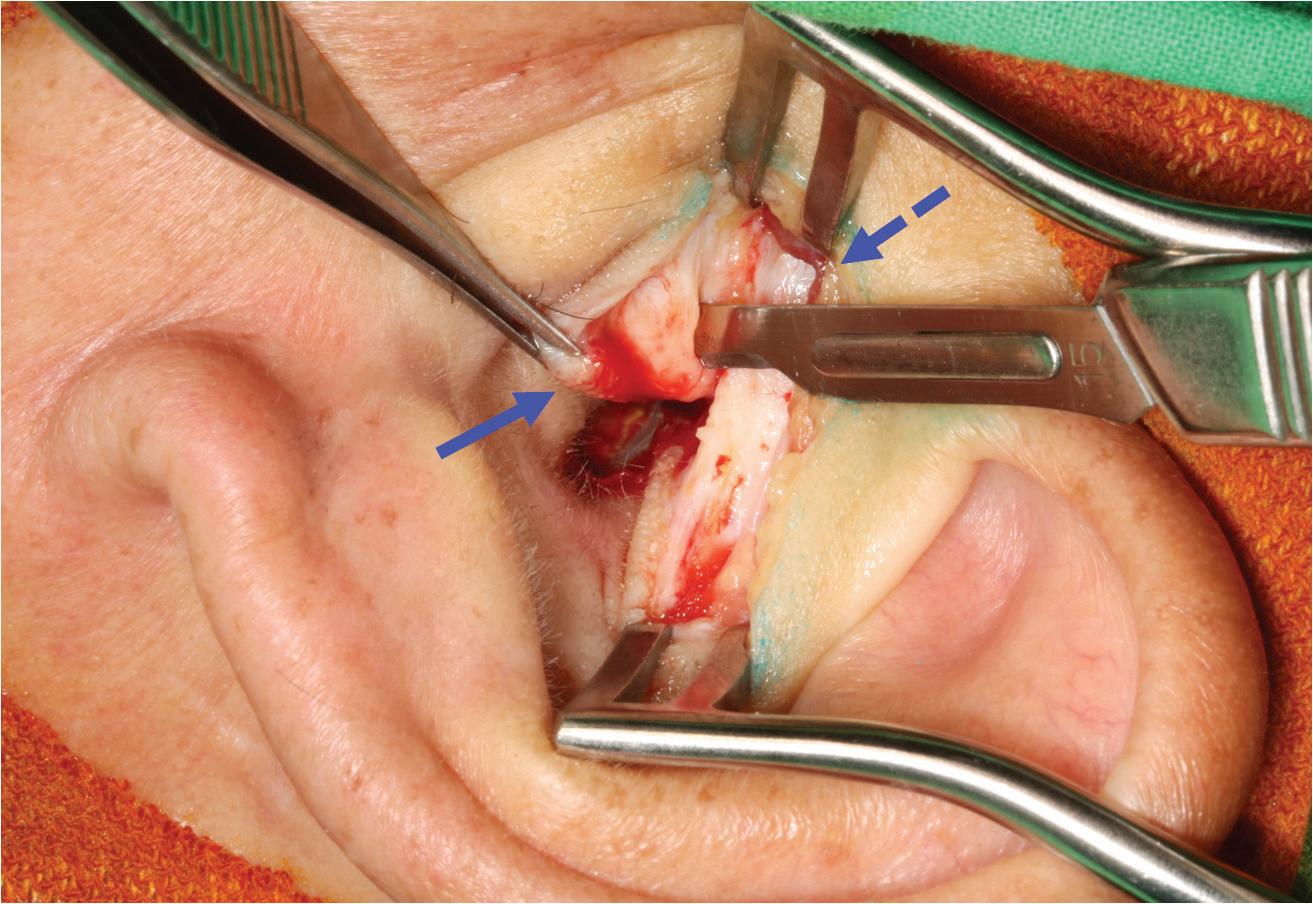

A 70-year-old man who had undergone postauricular underlay myringoplasty to treat chronic otitis media 10 years earlier presented with a 6-month history of hearing impairment, aural fullness, and occasional otorrhea of the right ear. Otoscopy revealed a large, bulging mass on the posterosuperior aspect of the external auditory canal (EAC); the tympanic membrane was invisible (figure 1). Computed tomography of the temporal bone revealed a right-sided, 2 × 2-cm soft-tissue mass in the EAC, with erosion of mastoid air cells but a normal eardrum and middle ear cavity.

Considering the postsurgical history and the site of the mass, we diagnosed an iatrogenic EAC cholesteatoma. A whitish, spherical mass was identified on surgical exploration and was completely removed through the prior postauricular incision (figure 2). We subsequently performed canalplasty with EAC

defect reconstruction using fragments of conchal cartilage. The pathologist’s report revealed histopathologic features compatible with cholesteatoma. No evidence of recurrent disease was present during the 5-year follow-up.

Iatrogenic EAC cholesteatoma is a rare complication developing after myringoplasty. The precise incidence of the disease remains unknown. We speculate that inversion or malpositioning of a tympanomeatal flap, or unintentional implantation of epithelium during the prior surgery, causes the subsequent defect.1,2

Small postsurgical EAC inclusion cysts or cholesteatomas are common and can be treated in the office via “unroofing” of the cyst and good ear hygiene practices.3 However, large, complicated iatrogenic EAC cholesteatomas usually require surgical management. The technique chosen is generally based on the extent of the disease and the surgeon’s preference, and it ranges

Continued on page 344

340 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

From the School of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taiwan (Dr. Lee); the School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taiwan (Dr. Hu, Dr. Chuang, and Dr. Chan); the Division of Otology, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (Dr. Hu and Dr. Chan); and the Department of Anatomic Pathology (Dr. Chuang), Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan.

Yen-Hui Lee, MD; Chih-Yu Hu, MD; Wen-Yu Chuang, MD; Kai-Chieh Chan, MD

OTOSCOPIC CLINIC

Figure 1. Otoscopy displays a large, bulging mass in the posterosuperior aspect of the external auditory canal.

WITH YOU, FOR YOU.

Partnership between Medtronic and surgeons like you, working together to advance navigation technology and protect patients — over 20 years strong — has resulted in some of the most advanced ENT technology available.

You can continue to trust navigation surgical solutions from Medtronic, such as the StealthStation™ ENT, to increase your operative efficiency and precision. Let’s advance further, together.

Rx only. Refer to product instruction manual/package insert for instructions, warnings, precautions and contraindications.

For further information, please call Medtronic ENT at 800.874.5797 or consult Medtronic’s website at www.medtronicent.com

© 2018 Medtronic. All rights reserved. Medtronic, Medtronic logo and Further, Together are trademarks of Medtronic. All other brands are trademarks of a Medtronic company. UC201902149a EN 09.2018

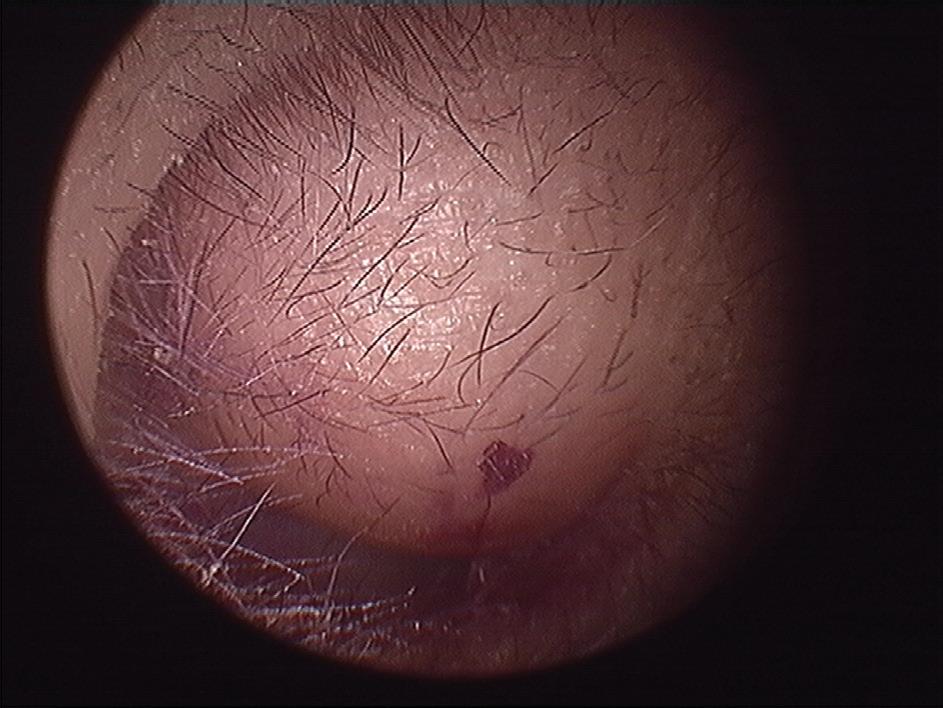

IMAGING CLINIC

Eagle syndrome: Transient ischemic attack and subsequent carotid dissection

Thomas Sullivan, MD; Jordan Rosenblum, MD

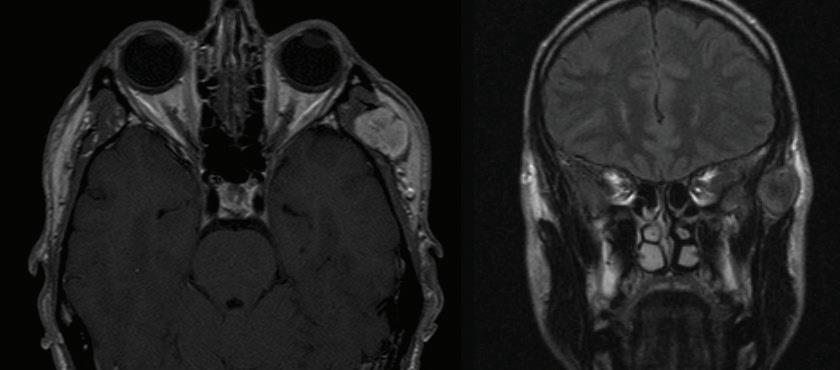

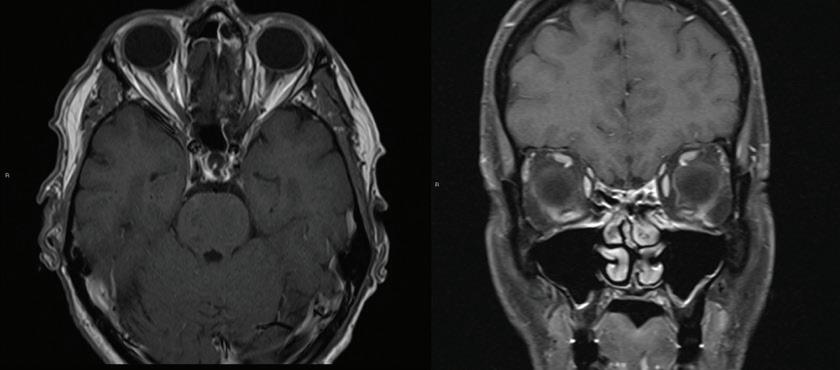

A 62-year-old man initially presented to our institution 3 months before his final diagnosis with transient right-sided weakness and brief loss of consciousness after reaching across his body in the shower. His medical history was significant for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. He had an implantable cardiac device and was on lifelong anticoagulation. Head computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography (CTA) were unremarkable, and although a transient ischemic attack (TIA) was thought to be unlikely given the anticoagulation therapy, this was a working diagnosis based on his symptoms, which were otherwise unexplained, and he was sent home.

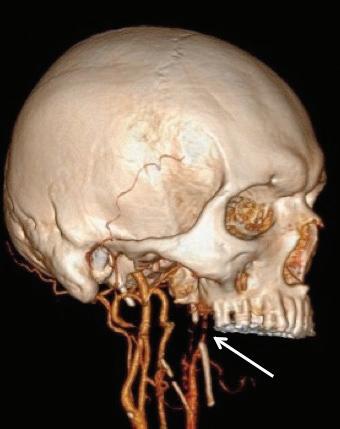

The patient returned 3 months later with sudden-onset behavioral changes, disorganized speech, and right-sided weakness. He reported no specific activity related to symptoms. CTA demonstrated complete left internal carotid occlusion at the level of the styloid tip, 1-cm cranial to the bifurcation, which extended to the carotid terminus (figure 1). Review of imaging obtained at his presentation 3 months earlier demonstrated a normal carotid.

CT of the head obtained at the most recent visit demonstrated new anterior, middle, and posterior circulation infarcts. In addition, we observed not only that his left styloid process was elongated (3.0 cm), but also that his stylohyoid ligament was calcified to the hyoid and possibly fractured (figure 2). We speculate that the fracture might have acted as a lead-point, causing injury

and subsequent dissection of the patient’s carotid. The contralateral styloid process was within normal limits, but the ligament was also calcified.

Prophylactic contralateral styloidectomy was considered, but the patient was deemed a poor surgical candidate given his underlying cardiomyopathy and anticoagulation. After further review of imaging, we felt his right carotid was a safe distance from the right styloid and ligament. As the left carotid was occluded to the skull base, he was not offered revascularization. We speculate that our patient’s initial presentation

From the Department of Radiology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

342 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

A B

Figure 1. A: 3-D reconstruction of the patient’s CTA with soft-tissue subtraction demonstrates the elongated and calcified stylohyoid ligament and dissected carotid artery cranial to the ligament (arrow). B: Additional 3-D reconstruction of the CTA with bone and soft tissue removed further demonstrates the dissected left internal carotid artery (arrow).

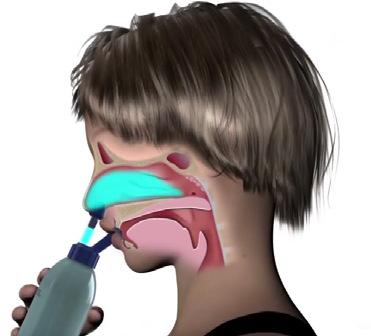

Boosting Effi ciency.

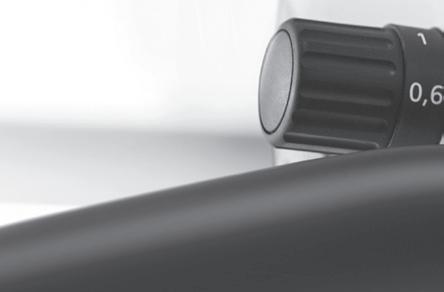

ZEISS EXTARO 300

INNOVATION

EXTARO® 300 from ZEISS allows you to save valuable time before, during and after each surgical intervention with:

• Augmented Visualization

• Single-Handed Operation

• Digital Data Management

We understand. Future.

www.zeiss.com/ent/extaro-300

//

MADE BY ZEISS

EN_30_030_0092I SUR.10455

might have been a harbinger of his impending cerebrovascular accident.

Eagle Syndrome is an uncommon but well-described entity with a nonspecific clinical presentation; more benign manifestations include globus sensation, dysphagia, facial neuralgias, throat pain, and cranial neuropathies, for which a differential is extensive.1,2 In the presence of an elongated styloid bone or stylohyoid, diagnostic consideration is often given to Eagle syndrome, but it may have a more insidious presentation. Elongation of the styloid also has been reported as a cause for symptomatic carotid disease, including TIA, Horner syndrome, eye pain, and cluster headache.3 Dissection associated with elongated styloids has been reported in the neurology literature,4 but to the best of our knowledge, no prior reports have demonstrated TIA with a normal carotid and subsequent carotid dissection during two separate clinical presentations.

Surgical and nonsurgical treatments for Eagle syndrome have been reported. Medical treatments, including carbamazepine, local and systemic steroids, and NSAIDS have been used.4 Surgical options include transpharyngeal resection, as originally favored by Eagle, versus an extraoral resection.

References

1. Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process: Report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1937;25(5):584-7.

2. Werhun EL, Weidenhaft MC, Palacios E, Neitzschman H. Stylohyoid syndrome, also known as Eagle syndrome: An uncommon cause of facial pain. Ear Nose Throat J 2014;93(9):384-5.

3. Infante-Cossio P, Garcia-Perla A, Gonzáles-Garcia A, et al. Compression of the internal carotid artery due to elongated styloid process [in Spanish]. Rev Neurol 2004;39(4):339-43.

4. Zuber M, Meder JF, Mas JL. Carotid artery dissection due to elongated styloid process. Neurology 1999;53(8):1886-7.

Continued from page 340

from canalplasty with skin grafting for lesions confined to EAC, to canalplasty or canal-wall-up mastoidectomy with reconstruction of canal defects for lesions involving mastoid cells, to canal-wall-down mastoidectomy for lesions with large wall defects exhibiting mastoid erosion.4 If an EAC defect is to be reconstructed, as in our case, nonretractable materials such as cartilage make ideal grafts.

Myringoplasty is a commonly used and simple type of middle ear surgery associated with a low risk of postoperative, iatrogenic EAC cholesteatoma. However, it is important to ensure high accuracy when repositioning the skin flap. In addition, delicate and meticulous management of every step is essential to avoid trapping or implantation of epithelial debris under the skin flap or graft.

Our case emphasizes the need for long-term follow-up because the average disease latency after otologic surgery is usually more than one decade.1,5

Approval of this case study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

References

1. Sweeney AD, Hunter JB, Haynes DS, et al. Iatrogenic cholesteatoma arising from the vascular strip. Laryngoscope 2017;127(3):698-701.

2. Persaud R, Hajioff D, Trinidade A, et al. Evidence-based review of aetiopathogenic theories of congenital and acquired cholesteatoma. J Laryngol Otol 2007;121(11):1013-19.

3. Holt JJ. Ear canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 1992;102(6):608-13.

4. Viswanatha B. External auditory canal cholesteatoma: A rare complication of tympanoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J 2009;88(11): 1206-9.

5. Cronin SJ, El-Kashlan HK, Telian SA. Iatrogenic cholesteatoma arising at the bony-cartilaginous junction of the external auditory canal: A late sequela of intact canal wall mastoidectomy. Otol Neurotol 2014;35(8):e215-21.

344 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018 OTOSCOPIC CLINIC IMAGING CLINIC

Figure 2. A spherical cholesteatoma sac is discovered during surgical exploration.

Figure 2. Axial CT shows the dissected internal carotid artery (arrow) and calcified stylohyoid ligament (asterisk).

PATHOLOGY CLINIC

Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis

Blake Raggio, MD

An 80-year-old farmer with arthritis, anemia, chronic kidney disease, and a history of shingles presented with a 3-month history of a painful, nonhealing, ulcerative pinna lesion refractory to antibiotics and local wound care (figure 1). He reported a subsequent development of similar ulcerative lesions involving the oral tongue and floor of his mouth.

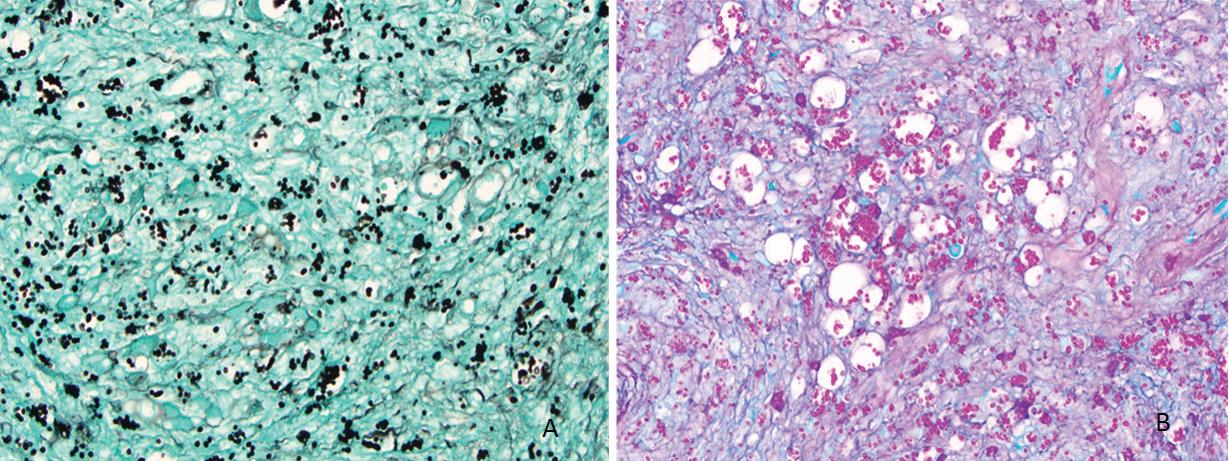

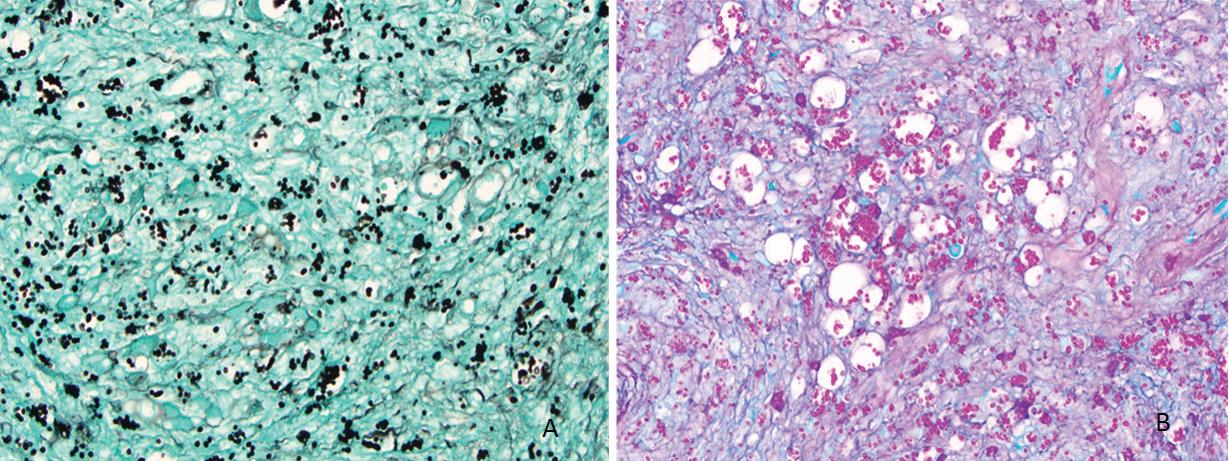

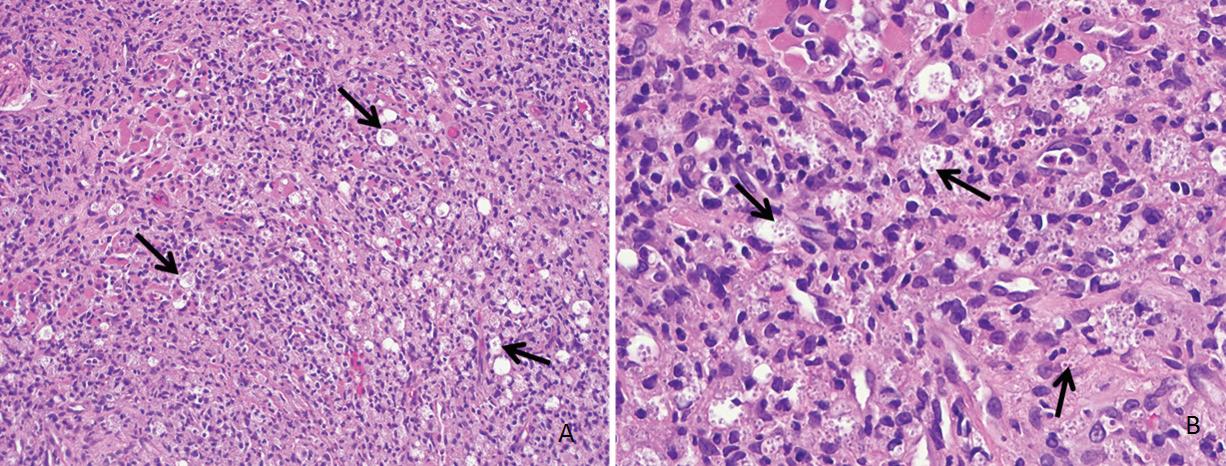

Biopsy of the pinna and oral cavity revealed diffuse, mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous epithelioid histiocytes containing small, circular yeast cells compatible with Histoplasma capsulatum (figure 2). Special stains for fungal organisms, including Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) were strongly positive (figure 3).

The patient had no clinical or laboratory findings to suggest systemic fungal infection, so oral itraconazole was initiated for treatment of primary cutaneous histoplasmosis with dissemination to the oral cavity. Despite a promising initial clinical response, the medication was withdrawn several weeks into therapy because of the patient’s worsening renal function. Hemodialysis was initiated; however, the patient’s health progressively deteriorated, and he passed away a few months later from renal-, heart-, and liver-associated complications.

H capsulatum is a soil saprophyte endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, often found in chicken habitats or caves inhabited by bats and birds. Infection by inhalation of aerosolized H capsulatum microconidia primarily affects the lungs of immunosuppressed individuals, although a variety of clinical presentations exist.1 Histoplasmosis of the skin, a less common presentation, occurs either secondarily via systemic infection that disseminates to the skin, or primarily via direct inoculation of H capsulatum during injury to the skin.1,2 The latter disease process, termed primary cutaneous histoplasmosis (PCH), rarely presents in the head and neck and is poorly described in the otolaryngologic literature.3

Patients with PCH present with nonspecific skin lesions including papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, abscesses, impetigo, or dermatitis.4 Diagnosis hinges on evidence of fungus in the wound and absence of systemic disease. Tissue biopsy of the cutaneous lesion should be performed promptly. Microscopy may reveal fungal elements and granuloma formation, but histopathology showing any distinctive 2- to 4-µm, oval, narrow-based budding yeasts secures the diagnosis (figure 2).

Continued on page 348

346 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

From the Department of Otolaryngology, Tulane University Medical Center; and the Department of Otolaryngology, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans. The case described in this article occurred at the University of Florida Medical Center, Gainesville. This article has been edited and adapted from its presentation as a poster at the American Academy of Otolarayngology–Head and Neck Surgery Annual Meeting; Sept. 10-13, 2017; Chicago.

Figure 1. Photo shows the erosive, ulceronodular lesion of the left pinna and preauricular skin.

THYROID AND PARATHYROID

CLINIC

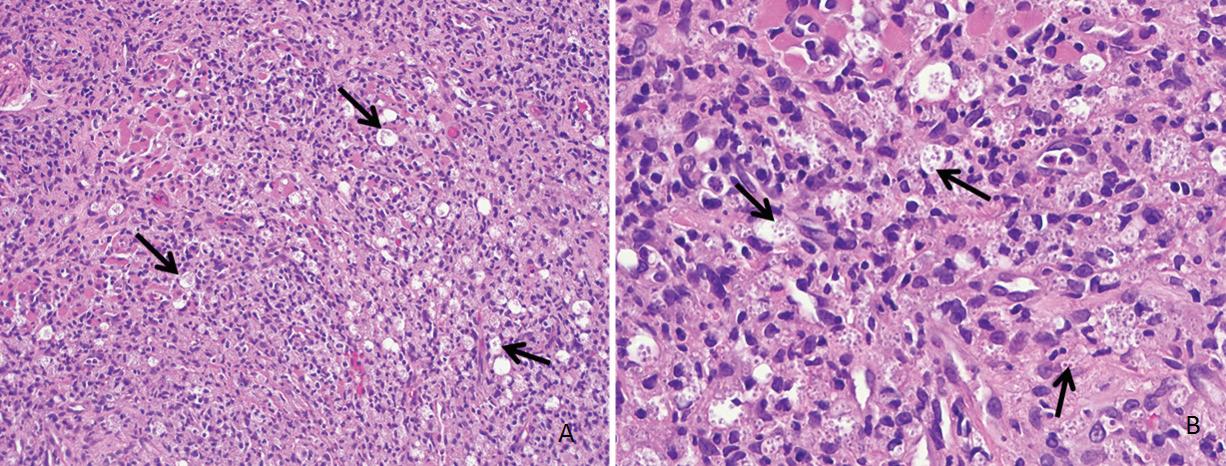

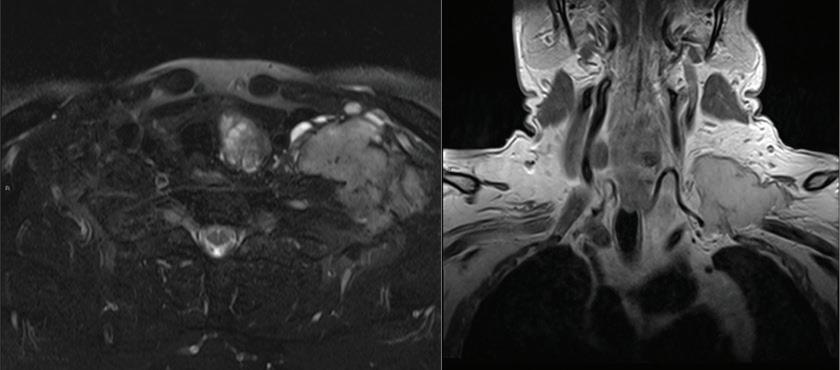

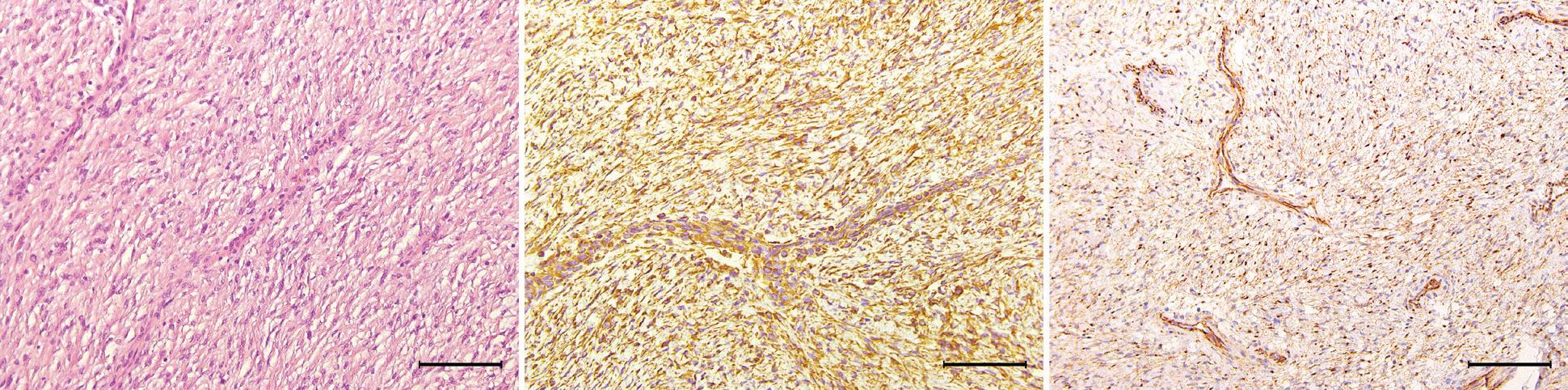

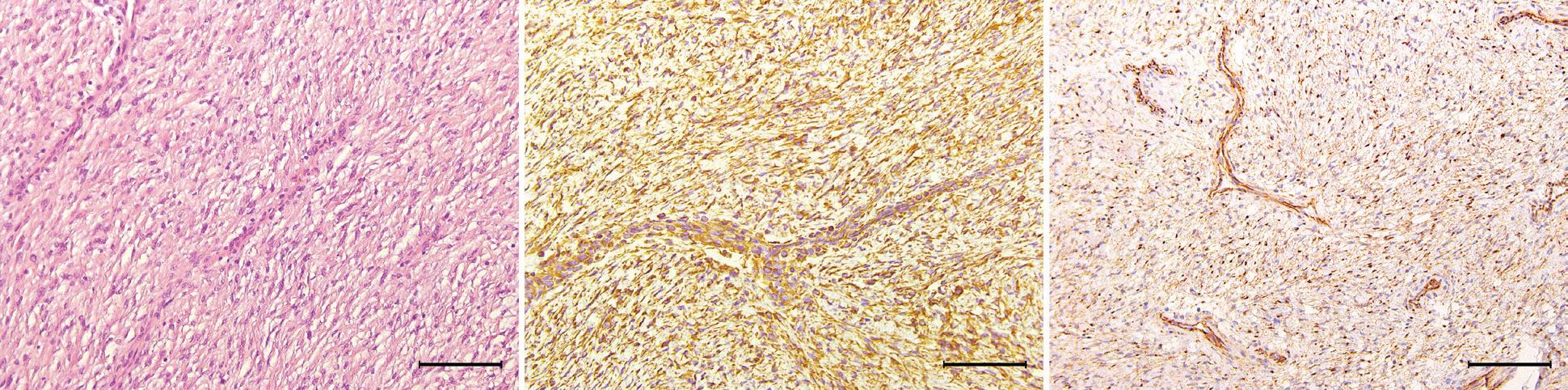

Huge primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland

Yong Tae Hong, MD; Ki Hwan Hong, MD

Primary leiomyosarcoma (LMS) of the thyroid gland is a rare thyroid malignancy, accounting for only 0.014% of primary thyroid tumors.1 It has an aggressive clinical course with a low survival rate. Diagnosis of LMS is challenging as it has a pathologic resemblance to other thyroid tumors. Therefore, immunohistochemical staining is essential for diagnosis.

There are 26 previously reported cases of primary thyroid LMS.2,3 Of the 26 patients, 14 died within 6 months due to the disease; only 7 lived >1 year, and only 1 patient survived for >5 years.3

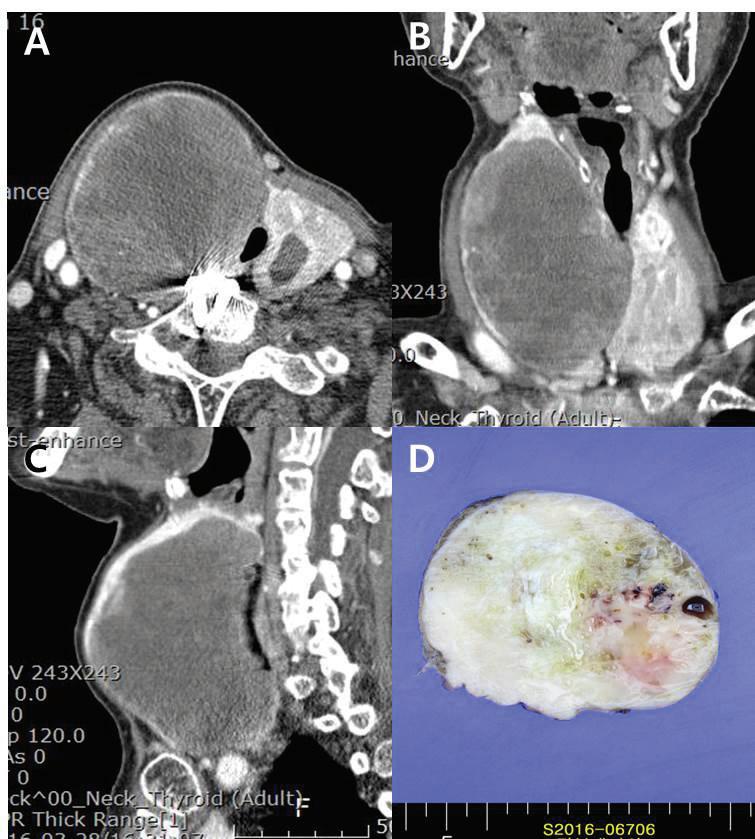

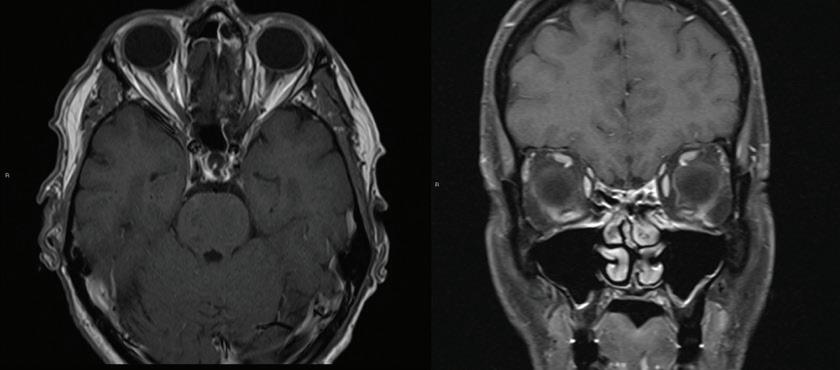

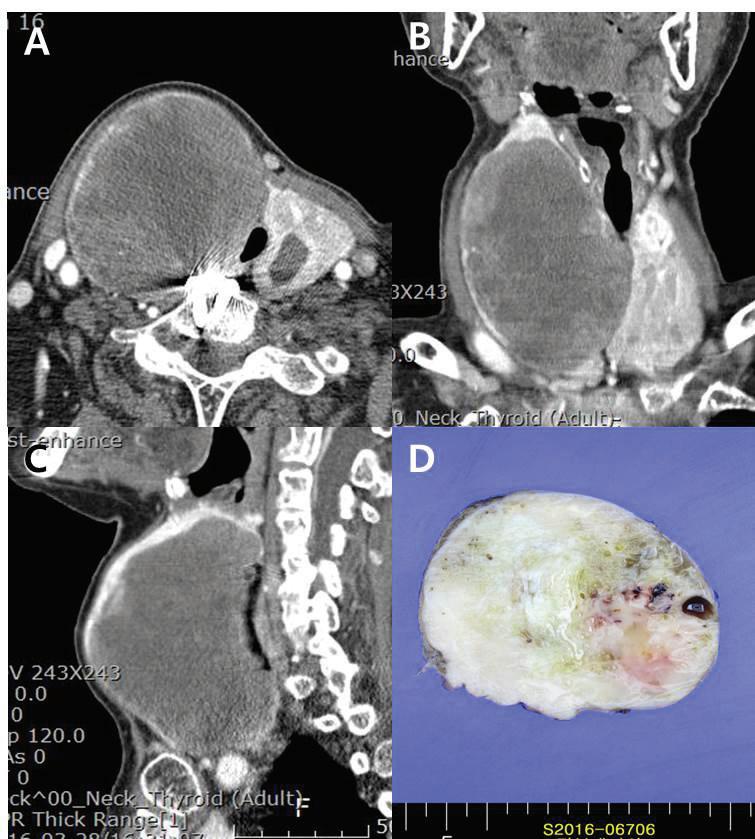

An 83-year-old woman who presented with aggravated dyspnea over a period of 1 month was admitted to our tertiary referral hospital. She had a history of Graves disease with a multinodular goiter involving the thyroid gland and had been receiving medical treatment with methimazole. On physical examination, a hard, protruding mass was noted in the anterior neck over the right thyroid cartilage. The cartilage was shifted toward the left side due to mass effect. Computed tomography (CT) with enhancement of the patient’s neck showed a huge (10 cm) mass in the right thyroid with luminal narrowing of the upper trachea due to mass effect (figure 1).

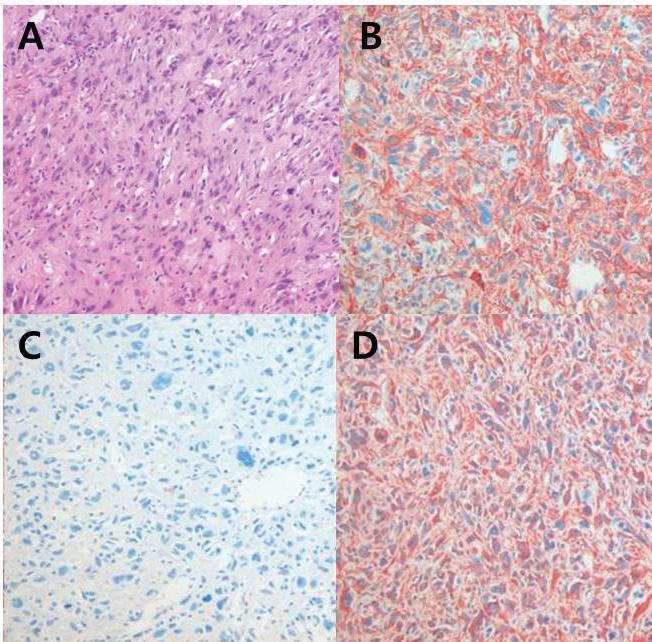

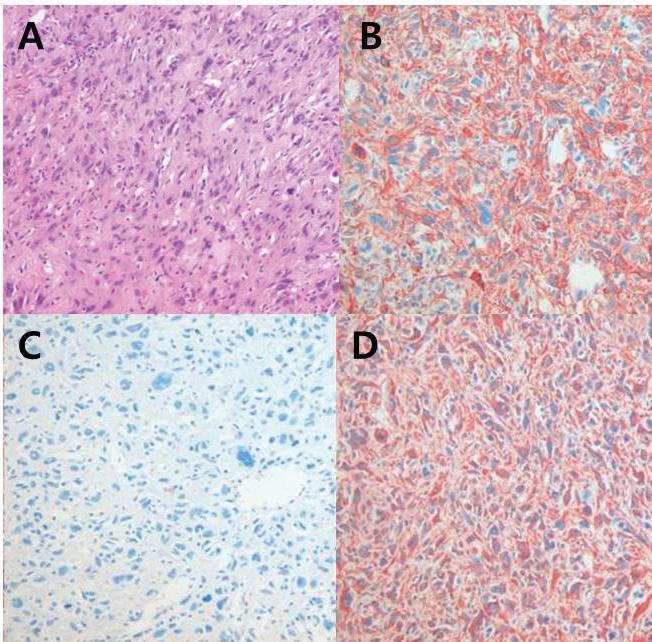

The patient underwent total thyroidectomy. Pathologic examination showed the mass to be positive for vimentin, cytokeratin, and actin, and negative for TTF-1, thyroglobulin, CD34, and EMA (figure 2). Therefore, the diagnosis of primary thyroid LMS was conclusive.

Considering the patient’s age and general condition, no other treatment was planned. At follow-up 12 months after surgery, the patient was still alive with no evidence of recurrence.

The etiology of primary LMS of the thyroid gland is not clear, although some studies have emphasized that the site of origin may be smooth muscles in blood vessels within the capsule of the thyroid.3 It has also been proposed that LMS may originate as a result of smooth-muscle metaplasia from a previously existing anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid.4,5 There is also a reported case of an LMS of the thyroid associated

Volume 97, Number 10-11 www.entjournal.com 347

From the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Research Institute for Clinical Medicine, Chonbuk National University, Chonbuk, Korea.

Figure 1. A-C: Contrast-enhanced neck CT images show the 10-cm heterogeneous mass with rim calcification on the right thyroid gland. The trachea is deviated to the left. D: An excised surgical specimen shows a homogeneous and partially cystic change.

with Epstein–Barr virus in a child with congenital immunodeficiency.6

There are several treatment options for LMS. In many reported cases, thyroid lobectomy or total thyroidectomy with or without neck dissection has been the first choice for treatment. Although surgery is the most commonly accepted treatment for the disease, no treatment has shown effectiveness. However, it is difficult to make an exact diagnosis of LMS before surgery and to distinguish it from anaplastic thyroid cancer, especially the spindle-cell variant of anaplastic thyroid cancer.1,2

References

1. Tanboon Jantima, Phawin Keskool. Leiomyosarcoma: A rare tumor of the thyroid. Endo Pathol 2013;24:136-43.

2. Chetty R, Clark SP, Dowling JP. Leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid: Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Pathology 1993;25:203-5.

3. Zou ZY. Primary thyroid leiomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review. Oncology Letters 2016;11:3982-6.

4. Tran LM, Mark R, Meier R, et al. Sarcomas of the head and neck: Prognostic factors and treatment strategies. Cancer 1992;70:169–77.

5. Akcam T, Oysul K, Birkent H. Leiomyosarcoma of the head and neck: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Auris Nasus Larynx 2005;32:209–12.

6. Just PA, Guillevin R, Capron F. An unusual clinical presentation of a rare tumor of the thyroid gland: Report on one case of leiomyosarcoma and review of literature. Ann Diag Path 2008;12:50–6.

Continued from page 346

GMS and PAS stains (figure 3) help identify H capsulatum in macrophages and within the tissue. Cultures showing small, oval, budding yeast can be used to confirm the diagnosis, but their results often take several weeks. Antigen detection is a sensitive method used for ruling out disseminated disease.1-3

Treatment of PCH depends on the extent and severity of the disease. Topical amphotericin B and nystatin can be used for limited disease, while systemic amphotericin B and itraconazole often are reserved for more widespread lesions.5 Incision and drainage may be necessary for lesions refractory to medical therapy.6

References

1. Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, et al. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016;30(1):207-27.

2. Tesh RB, Schneidau JD Jr. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. N Engl J Med 1966;275(11):597-9.

3. Kollipara R, Hans A, Hall J, Watson K. A case report of primary cutaneous histoplasmosis requiring deep tissue sampling for diagnosis. Dermatol Online J 2014;20(11). pii: 13030/ qt/11b53041.

4. Chang P, Rodas C. Skin lesions in histoplasmosis. Clin Dermatol 2012;30(6):592-8.

5. Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45(7):807-25.

6. Buitrago MJ, Gonzalo-Jimenez N, Navarro M, et al. A case of primary cutaneous histoplasmosis acquired in the laboratory. Mycoses 2011;54(6):e859-61.

348 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018

Figure 2. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E)-stained sections demonstrate numerous vacuolated areas (arrows) surrounded by a diffuse, mixed inflammatory infiltrate (A; original magnification ×20) and numerous epithelioid histiocytes with small, circular yeast cells (arrows), characteristic of H capsulatum (B; original magnification ×40).

Figure 3. GMS (A) and PAS (B) stains highlight numerous aggregates and randomly distributed organisms of H capsulatum (original magnification ×40).

A A B B

Figure 2. Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows a spindle-cell tumor arranged in a fascicular pattern with eosinophilic cytoplasm (A). Immunohistochemical staining of the tumor shows a positive reaction to smooth muscle actin (B), cytokeratin (C), and vimentin (D) (original magnification ×200).

PATHOLOGY CLINIC THYROID AND PARATHYROID CLINIC

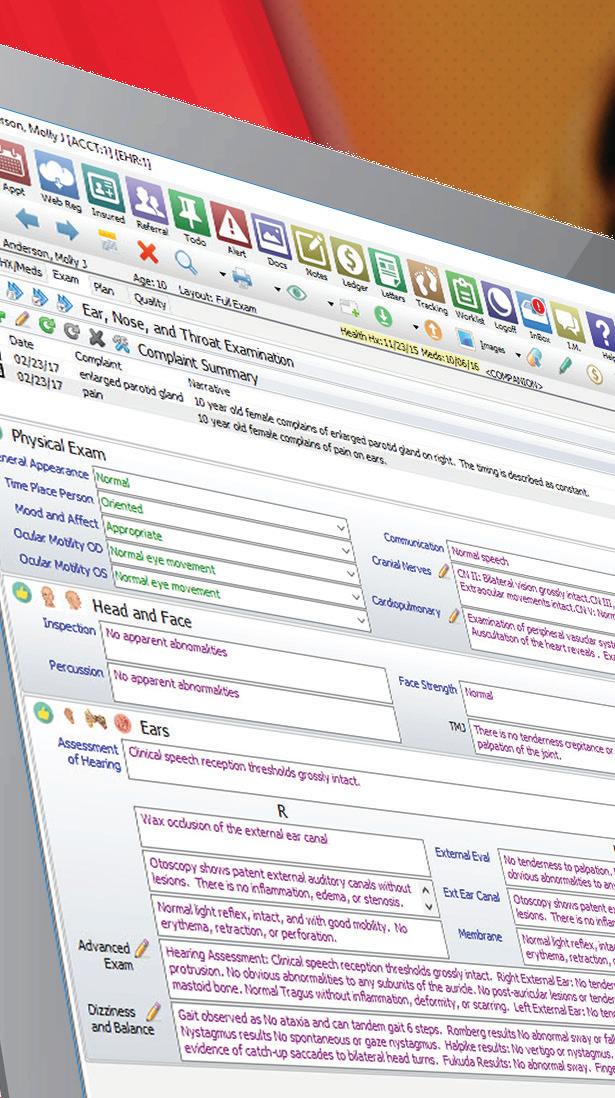

Clinical outcome of revision cartilage tympanoplasty

Pei-Yin Wei, MD; Chia-Hui Chu, MD, MPH; Mao-Che Wang, MD, PhD

Abstract

We retrospectively reviewed 32 ears from 30 adult patients with chronic otitis media who underwent revision tympanoplasty using cartilage graft (performed by a single surgeon) from January 10, 2011, to May 10, 2016. All procedures were performed using an endaural incision for both temporalis fascia graft and tragal cartilage graft harvesting. The overall surgical success rate was 93.3%. The average preoperative hearing level was 43.1 ± 17.3 dBHL, and the average postoperative hearing level was 39.2 ± 18.2 dBHL, representing a significant improvement. The average air-bone gap was 19.4 ±7.6 dB preoperatively and 16.9 ± 9.9 dB postoperatively. Also of note, the improvement in air-bone gap reached the level of significance at 500 Hz (p = 0.023). We conclude that using cartilage graft in revision tympanoplasty is a safe and reliable technique with good surgical outcomes. Using one single endaural incision for both fascia and cartilage harvesting is simple while achieving aesthetic wound healing.

Introduction

Tympanoplasty is a commonly performed surgery for the management of chronic otitis media with the aim of preserving the tympanic membrane without infection and restoring the sound-conducting mechanism. Since it was first introduced by Wullstein in 19521 and Zollner in 1955,2 several grafting materials have been described including temporalis fascia, perichondria, periostia, vein, fat, and cartilage.3-5

To date, the temporalis fascia and perichondrium are still the grafting material mainstays in primary tympanoplasty, with a success rate ranging from 35 to 95%.6,7 However, fascia and perichondrium appear to undergo atrophy and subsequently fail in the reconstruction of high-risk perforations,8 such as total or

From the Department of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (Dr. Wei, Dr. Chu, and Dr. Wang); and the School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei (Dr. Chu and Dr. Wang).

Corresponding author: Mao-Che Wang, MD, No. 201, Sec. 2, Shipai Rd., Beitou District, Taipei City, Taiwan 11217, R.O.C. Email: wangmc@vghtpe.gov.tw

subtotal atelectatic perforations, those with cholesteatoma, and revision cases. In these situations, cartilage tympanoplasty is being used increasingly due to its stability, resistance to negative middle ear pressure, and resistance to infections due to the lack of vascularization.9 Compared with fascia graft, similar functional results (hearing improvement) but better morphologic results (intact eardrum) have been reported with the use of cartilage tympanoplasty.10

One of the possible risk factors of failed tympanoplasty is persistent negative middle ear pressure, in which fascia and perichondrium grafting might not be sufficiently robust. Therefore, in revision surgery, cartilage graft may be preferred because of its rigidity, a property that may promote resistance to negative middle ear pressure.

The aim of this study was to analyze the anatomic and audiologic results of revision cartilage tympanoplasty.

Patients and methods

From January 10, 2011, to May 10, 2016, we analyzed 30 adult patients (32 ears) with chronic otitis media who underwent revision cartilage tympanoplasty; all surgeries were performed by a single surgeon. Patients with cholesteatoma or younger than 20 years were excluded.

By retrospective chart review, we recorded each patient’s sex, age at operation, perforation size (small: perforation up to one-third of the tympanic membrane; medium: perforation between one-third and twothirds of the tympanic membrane; large: perforation more than two-thirds of the tympanic membrane), preoperative and postoperative pure-tone audiograms (500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz, respectively), and surgical success.

All patients underwent revision cartilage tympanoplasty according to the following protocol. First, an endaural incision was made to facilitate temporalis fascia graft harvesting. Second, the medial part of the tragus was harvested from the same incision and cut into halves to be used as the cartilage graft. Third, after refreshing the perforation edge and elevating the tympanomeatal flap, an underlay grafting technique

Volume 97, Number 10-11 www.entjournal.com 349 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

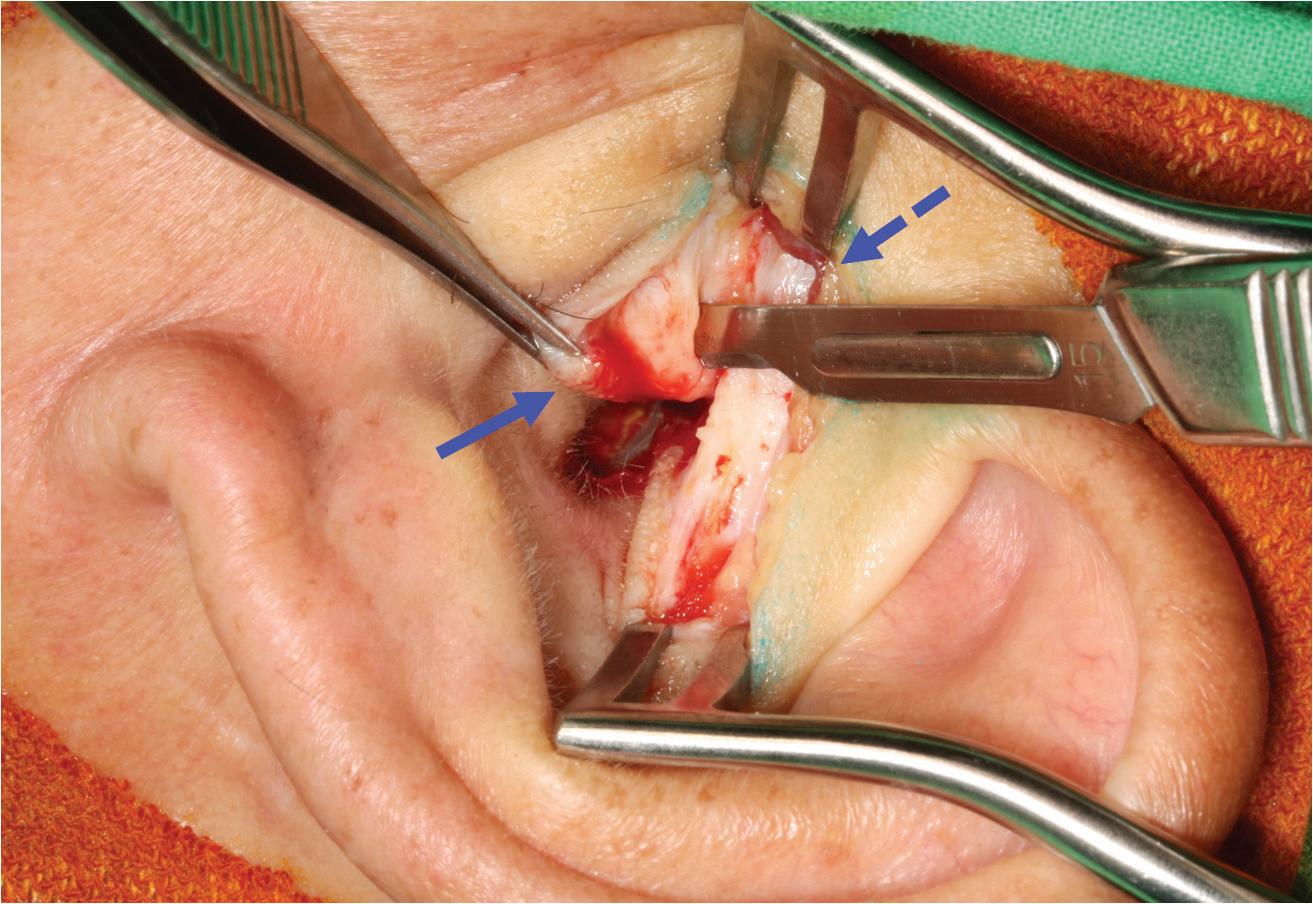

with a temporalis fascia graft and cartilage reinforcement was performed (figure 1). No patient underwent simultaneous ossiculoplasty.

Surgery was considered successful if no residual perforation of the eardrum was present. Postoperative pure-tone audiometry was measured 3 months after surgery. The average hearing level was defined as the mean air-conduction threshold at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz.

A paired t test was performed to determine the difference between preoperative and postoperative pure-tone average and air-bone gaps. Statistical significance was assumed for p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, v. 19.0.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Results

A total of 30 patients (17 men and 13 women) (32 ears) with a mean age of 52 years (range: 20 to 74) were enrolled. The mean number of previous tympanoplasties was 1.18 (range: 1 to 3); perforation size was small in 14 (43.8%) ears, medium in 13 (40.6%) ears, and large in 5 (15.6%) ears, and included 2 total perforations. The average preoperative air-bone gap was 19.4 ± 7.6 dB. The mean follow-up time was 7 months (range: 1 to 45), and the overall surgical success rate was 93.3%. An image obtained 9 months postoperatively is shown in figure 2.

Audiologic outcomes. The average hearing level was 43.1 ± 17.3 dBHL preoperatively and 39.2 ± 18.2 dBHL postoperatively. The change between preoperative and postoperative hearing level was significant (p = 0.029) (table 1). The average air-bone gap declined from 19.4 ± 7.6 dB preoperatively to 16.9 ± 9.9 dB postoperatively, a

trend toward improvement that did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.196) (table 2).

Both the change in hearing level and air-bone gap reached a level of significant improvement at 500 Hz (tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

Use of the cartilage graft was first described in middle ear surgery in 1959,11 and it has been used in the management of high-risk perforations more recently due to its robust and rigid characteristics. In revision tympanoplasty, eustachian tube dysfunction and negative middle ear pressure are the possible causes of previous failure.

Compared with fascia and perichondrium grafts, cartilage graft proved to be a superior choice in revision surgery because of its superior resistance to negative middle ear pressure.

Although primary tympanoplasty has a high success rate, the graft-take rate decreases in revision tympano-

350 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018 WEI, CHU, WANG,

Figure 2. In this image, an intact eardrum without residual perforation can be seen on otoscopy 9 months postoperatively.

Figure 1. These photographs show elements of the single endaural incision approach. A: An endaural incision is made. B: Both the temporalis fascia (dashed arrow) and tragal cartilage (arrow) grafts are harvested with a single incision.

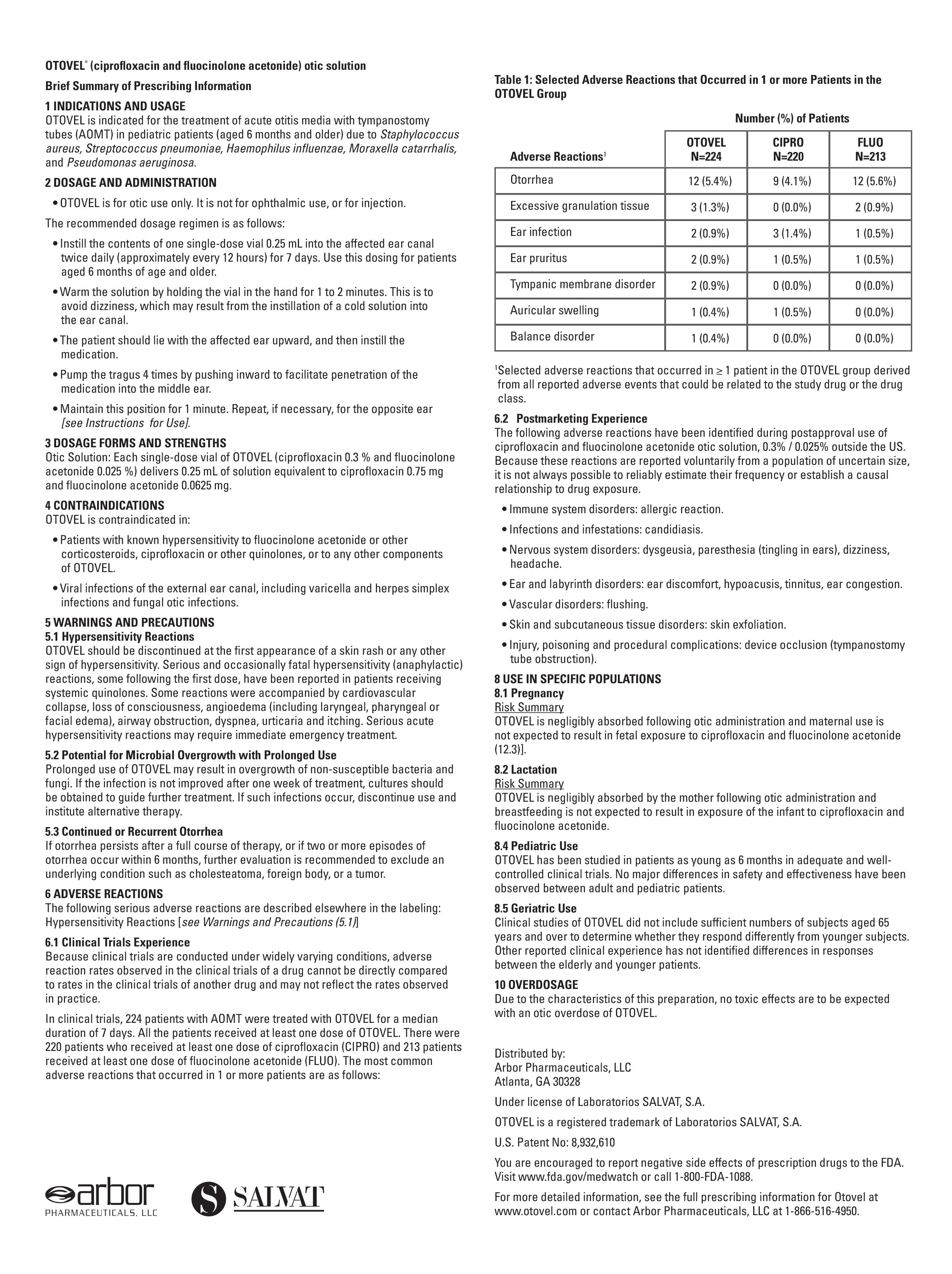

For the treatment of AOMT in pediatric patients due to S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, and P. aeruginosa.

The difference is in the delivery.

The first and only antibiotic/steroid combination ear drop in single-dose vials

• Manufactured using blow-fill-seal technology— each vial is formed, filled, and sealed in a continuous, automated, sterile operation2,3

• Technology minimizes human intervention in the fill/finish process3

• Single-use vials contain 1 premeasured dose each—dose BID/7 days4

• No drop counting. No mixing or shaking required4

• Demonstrated efficacy and safety in 2 clinical trials1,5 Order

INDICATIONS

OTOVEL® (ciprofloxacin and fluocinolone acetonide) is indicated for the treatment of acute otitis media with tympanostomy tubes (AOMT) in pediatric patients (aged 6 months and older) due to S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, and P. aeruginosa.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Contraindications

OTOVEL is contraindicated in:

• Patients with known hypersensitivity to fluocinolone acetonide or other corticosteroids, ciprofloxacin or other quinolones, or to any other component of OTOVEL.

• Viral infections of the external ear canal, including varicella and herpes simplex infections and fungal otic infections.

The following Warnings and Precautions have been associated with OTOVEL: hypersensitivity reactions, potential for microbial overgrowth with prolonged use, and continued or recurrent otorrhea.

The most common adverse reactions are otorrhea, excessive granulation tissue, ear infection, ear pruritis, tympanic membrane disorder, auricular swelling, and balance disorder.

For additional Important Safety Information, please see Brief Summary of Prescribing Information on adjacent page, and full Prescribing Information available at www.otovel.com.

References: 1. Otovel [package insert]. Atlanta, GA: Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. 2016. 2. Data on file. Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. 3. Guidance for industry: sterile drug products produced by aseptic processing—current good manufacturing practice. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm070342.pdf.

2016. 5. Spektor Z, Pumarola P, Ismail K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone in otitis media with tympanostomy tubes in pediatric patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;143(4):341-349.

Otovel is a registered trademark of Laboratorios Salvat, S.A. with the US Patent and Trademark Office and under license by Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. Trademarks are the property of their

September 2004.

March 15, 2018. 4. Orange Book:

products

US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/

May 17, 2013.

July 15,

Published

Accessed

Approved drug

with therapeutic equivalence evaluations.

cder/ob/default.cfm. Updated

Accessed

respective owners. © 2018 Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. All rights reserved. Printed in USA. PP-OTO-US-0268

1

Starter Packs today at otovel.com/hcp/resources

AOMT=acute otitis media with tympanostomy tubes; BID=twice daily.

*Statistically significant.

Key: SD = standard deviation.

plasty. Lesinskas and Stankeviciute reported successful closure rates of primary and revision tympanoplasty of 93.6 and 90.2%, respectively.12 Additionally, the grafttake rates of revision tympanoplasty were 90.9% for temporal fascia, 82.4% for perichondrium, and 93.8% for perichondrium/cartilage as graft material, without a statistically significant difference between them.

Sismanis et al reported a 93.5% graft-take rate with the use of cartilage shield grafts in revision tympanoplasty,13 and Boone et al reported a 94.7% graft-take rate with tragal cartilage–perichondrium island graft or palisaded concha cymba cartilage.14

In our study, the overall success rate was 93.3%, which was comparable to that obtained in previous studies. Residual perforation was found in 2 patients, 1 with a small and 1 with a large preoperative perforation. Neither size of perforation nor number of previous tympanoplasties correlated with surgical success. Possible explanations for surgical failure in these 2 cases were anterior marginal perforation in 1 patient, which was a relative surgical challenge compared with central perforation, and granulation with fibrosis in the middle ear cavity of the other patient, which may imply previous infectious status.

Several techniques for cartilage tympanoplasty have been described, such as cartilage palisade tympanoplasty, cartilage shield graft, perichondrium/cartilage island flap, cartilage butterfly inlay technique, and cartilage reinforcement tympanoplasty.13,15-17

In the present study, we used a single endaural incision for both temporalis fascia and tragal cartilage harvesting. The advantages of this method are that only one incision was needed and there was no deformity of the tragus postoperatively. To our knowledge,

this surgical technique has not been reported previously.

We showed a statistically significant improvement in the mean postoperative hearing level, from 43.1 ± 17.3 dBHL preoperatively to 39.2 ± 18.2 dBHL postoperatively, but not in the mean postoperative air-bone gap, which declined from 19.4 ± 7.6 dB preoperatively to 16.9 ± 9.9 dB postoperatively. However, changes in the hearing level and in the air-bone gap at 500 Hz both improved significantly (42.8 ± 15.5 dBHL to 32.6 ± 18.0 dBHL, and 18.6 ± 11.2 dB to 11.1 ± 14.5 dB, respectively). One possible explanation is that sound transmission was affected because of an increased mass and stiffness of the cartilage graft, especially at high frequency.

Using laser Doppler vibrotomy, Zahnert et al showed that cartilage should not exceed 0.5 mm in thickness to minimize the energy loss in sound transmission.18 Through the use of finite element analysis, Lee et al reported that the optimal thickness of cartilage graft was 0.1 to 0.2 mm for medium (55% perforation) and large perforations (85% perforation), and less than 1.0 mm for small perforations (15% perforation).19 Sound transmission properties at different frequencies require further investigation.

The limitation of the present study was the relatively small sample size.

Conclusion

Revision cartilage tympanoplasty is a safe and reliable technique with both an excellent morphologic result and good audiologic outcome at low frequency. A novel single endaural incision approach was advantageous for both fascia and cartilage harvesting and also achieved aesthetic wound healing.

*Statistically significant. Key: SD = standard deviation.

Volume 97, Number 10-11 www.entjournal.com 353 CLINICAL OUTCOME Of REvISION CARTILAGE TYMPANOPLASTY

Frequency (Hz) Hearing level (dB) ± SD p Value Preoperative Postoperative 500 42.8 ± 15.5 32.6 ± 18.0 0.001* 1,000 41.3 ± 16.2 37.3 ± 18.1 0.103 2,000 40.3 ± 20.0 38.4 ± 19.6 0.387 4,000 47.8 ± 25.8 48.4 ± 22.1 0.786 Average 43.1 ± 17.3 39.2 ± 18.2 0.029*

Table 1. Comparison of preoperative and postoperative hearing level

Frequency (Hz) Air-bone gap (dB) ± SD p Value Preoperative Postoperative 500 18.6 ± 11.2 11.1 ± 14.5 0.023* 1,000 19.7 ± 11.9 18.1 ± 8.6 0.537 2,000 17.7 ± 9.4 18.1 ± 8.6 0.859 4,000 21.8 ± 10.1 19.3 ± 10.4 0.320 Average 19.4 ± 7.6 16.9 ± 9.9 0.196

Table 2. Comparison of preoperative and postoperative air-bone gap

Continued on page 361

Persistent local demucosalization after endoscopic sinus surgery: A report of 3 cases

Conner J. Massey, MD; Menka M. Sanghvi, MD; Thomas R. Troost, MD, PhD; Vijay K. Anand, MD; Ameet Singh, MD

Abstract

Mucosal preservation is paramount to achieving successful outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). Despite best surgical practices and implementation of evidenced-based postoperative care, patients in rare cases might exhibit persistent demucosalization that is recalcitrant to conservative therapies. We retrospectively reviewed the records of 3 patients—a 63-year-old woman, a 67-year-old woman, and a 43-year-old man—who experienced clinically significant local demucosalization after uncomplicated ESS despite routine surgical and postoperative management. We collected data on the characteristics of presentation, wound management strategies, and postoperative care practices. Two patients achieved remucosalization with mechanical debridement, gelatin sponge placement, and intensive moisturization therapy. Our experience suggests that surgical debridement of these chronic, persistent demucosalized wounds may be an effective management strategy for patients who develop this unusual and rare postoperative complication. Biopsy and culture of the persistently demucosalized wound bed may be useful in recognizing the presence of worrisome disease processes and identifying any tenacious infectious agents so that more appropriate therapy can be initiated if necessary.

Introduction

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) is a primary treatment modality for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) whose disease is refractory to maximal medical management. ESS functions to aerate the paranasal sinuses and remove polyps, fungus, and debris that can impede mucociliary clearance, all while attempting to preserve normal mucosal tissue as much as possible. In fact, it has been shown repeatedly that mucosal preservation is paramount to achieving successful outcomes after ESS.1,2 Failure to adequately preserve the nasal and sinus mucosa during ESS has been associated with a number of complications that can result in treatment failure, such as adhesions, persistent crusting, osteoneogenesis, osteitis, postoperative chronic sinusitis, and ostial stenosis.3

Mucosal preservation and wound healing in general depend on several surgical and nonsurgical factors. Surgical factors primarily include surgical technique, the type of adjunctive biomaterials used (if any), routine postoperative surgical debridement, and patient compliance with wound care. Nonsurgical factors that can negatively impact wound healing consist of systemic conditions such as diabetes, immunodeficiencies, primary ciliary dyskinesia, and cystic fibrosis. Other factors include exposure to tobacco smoke and cytotoxic medications, and the presence of entrenched bacterial or fungal colonization.4

From the Department of Otolaryngology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora (Dr. Massey); the Department of Ophthalmology (Dr. Sanghvi) and the Division of Otolaryngology (Dr. Troost and Dr. Singh), George Washington University Hospital, Washington, D.C.; and the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Weill Cornell School of Medicine, New York City (Dr. Anand). The cases described in this article occurred at the George Washington University Hospital and the Weill Cornell School of Medicine.

Corresponding author: Conner J. Massey, MD, Department of Otolaryngology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 12631 E. 17th Ave., B-205, Aurora, CO 80045. Email: conner.massey@ ucdenver.edu

By and large, patients who undergo ESS with an exacting surgical technique, judicious debridement of the postoperative surgical cavity, proactive wound care, and an absence of deleterious host factors tend to experience excellent wound-healing outcomes. Most such patients experience complete remucosalization by 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively. Histologic animal studies have confirmed this timeline, showing that respiratory mucosa is restored by the 28th day after injury.5 However, there are unusual cases in which patients fail to heal as expected despite a confluence of optimal factors.

354 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal October-November 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A clear choice for EAR-RESISTIBLE patients

It’s a clear choice ear after ear

CIPRODEX® Otic is the #1 prescribed antibiotic eardrop of ENTs and pediatricians.1

It has been prescribed for AOE and AOMT since 2003, with more than 30 million prescriptions filled.1,2

AOE, acute otitis externa; AOMT, acute otitis media with tympanostomy tubes. Not an actual patient.

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

CIPRODEX® Otic is indicated for the treatment of infections caused by susceptible isolates of the designated microorganisms in:

• Acute Otitis Media (AOM) in pediatric patients (age ≥ 6 months) with tympanostomy tubes due to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

• Acute Otitis Externa (AOE) in pediatric (age ≥ 6 months), adult and elderly patients due to Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

DOSAGE

• CIPRODEX® Otic is for otic use only, and not for ophthalmic use, or for injection.

• The recommended dosage is four drops into the affected ear twice daily for seven days.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION CONTRAINDICATIONS

• CIPRODEX® Otic is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to ciprofloxacin, to other quinolones, or to any of the components in this medication.

• Use of this product is contraindicated in viral infections of the external canal including herpes simplex infections and fungal otic infections.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION (CONT) WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Hypersensitivity Reactions: CIPRODEX® Otic should be discontinued at the first appearance of a skin rash or any other sign of hypersensitivity. Serious and occasionally fatal hypersensitivity (anaphylactic) reactions, some following the first dose, have been reported in patients receiving systemic quinolones.

Potential for Microbial Overgrowth with Prolonged Use: Prolonged use of CIPRODEX® Otic may result in overgrowth of nonsusceptible bacteria and fungi. If the infection is not improved after one week of treatment, cultures should be obtained to guide further treatment. If such infections occur, discontinue use and institute alternative therapy.

Continued or Recurrent Otorrhea: If otorrhea persists after a full course of therapy, or if two or more episodes occur within six months, further evaluation is recommended to exclude an underlying condition such as cholesteatoma, foreign body, or a tumor.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most commonly reported adverse reactions in clinical trials were:

• AOM pediatric patients with tympanostomy tubes: ear discomfort (3.0%), ear pain (2.3%), ear residue (0.5%), irritability (0.5%) and taste perversion (0.5%).

• AOE patients: ear pruritus (1.5%), ear debris (0.6%), superimposed ear infection (0.6%), ear congestion (0.4%), ear pain (0.4%) and erythema (0.4%).

Please see Brief Summary of Prescribing Information on adjacent page.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation East Hanover, New Jersey 07936-1080 © 2018 Novartis 10/18 T-CDX-1364334

References: 1. IQVIA. CIPRODEX® : Annual TRx & NRx 2003-2017. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; February 2018. 2. CIPRODEX® Otic [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Alcon Laboratories, Inc; 2015. CIPRODEX® is a registered trademark of Bayer, used with permission.

BRIEF SUMMARY OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

For additional information refer to the full prescribing information.

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

CIPRODEX® is indicated for the treatment of infections caused by susceptible isolates of the designated microorganisms in the specific conditions listed below:

• Acute Otitis Media in pediatric patients (age 6 months and older) with tympanostomy tubes due to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

• Acute Otitis Externa in pediatric (age 6 months and older), adult and elderly patients due to Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

• CIPRODEX is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to ciprofloxacin, to other quinolones, or to any of the components in this medication.

• Use of this product is contraindicated in viral infections of the external canal including herpes simplex infections and fungal otic infections.

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Hypersensitivity Reactions

CIPRODEX should be discontinued at the first appearance of a skin rash or any other sign of hypersensitivity. Serious and occasionally fatal hypersensitivity (anaphylactic) reactions, some following the first dose, have been reported in patients receiving systemic quinolones. Some reactions were accompanied by cardiovascular collapse, loss of consciousness, angioedema (including laryngeal, pharyngeal or facial edema), airway obstruction, dyspnea, urticaria and itching.

5.2 Potential for Microbial Overgrowth with Prolonged Use

Prolonged use of CIPRODEX may result in overgrowth of non-susceptible, bacteria and fungi. If the infection is not improved after one week of treatment, cultures should be obtained to guide further treatment. If such infections occur, discontinue use and institute alternative therapy.

5.3 Continued or Recurrent Otorrhea

If otorrhea persists after a full course of therapy, or if two or more episodes of otorrhea occur within six months, further evaluation is recommended to exclude an underlying condition such as cholesteatoma, foreign body, or a tumor.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are described elsewhere in the labeling:

• Hypersensitivity Reactions [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

• Potential for Microbial Overgrowth with Prolonged Use [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to the rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

In Phases II and III clinical trials, a total of 937 patients were treated with CIPRODEX. This included 400 patients with acute otitis media with tympanostomy tubes and 537 patients with acute otitis externa. The reported adverse reactions are listed below:

Acute Otitis Media in Pediatric Patients with Tympanostomy Tubes

The following adverse reactions occurred in 0.5% or moreof the patients with non-intact tympanic membranes.

Adverse Reactions Incidence (N=400)

Ear discomfort 3.0%

Ear pain 2.3%

Ear precipitate (residue) 0.5%

Irritability 0.5%

Taste Perversion 0.5%

The following adverse reactions were each reported in a single patient: tympanostomy tube blockage; ear pruritus; tinnitus; oral moniliasis; crying; dizziness; and erythema.

Acute Otitis Externa

The following adverse reactions occurred in 0.4% or more of the patients with intact tympanic membranes.