Crafting Carménère

Award-Winning Home Wine Labels

Successful Backyard Vineyard Case Study

Crafting Carménère

Award-Winning Home Wine Labels

Successful Backyard Vineyard Case Study

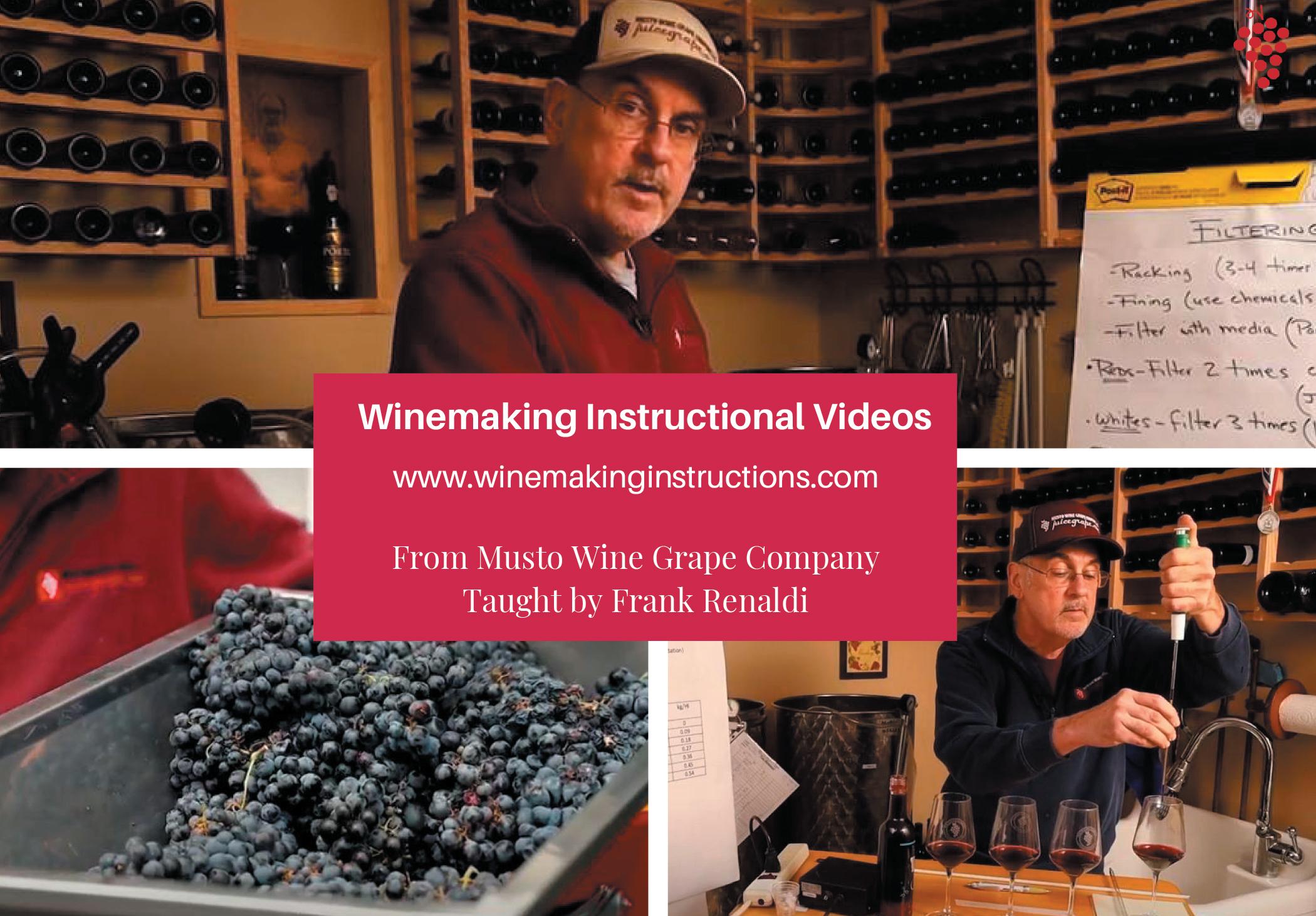

KEYS TO SCALING UP & MAKING MORE GREAT WINE

CREATING A WINERY IN YOUR GARAGE

ADDING FRUIT TO HOMEMADE MEAD

Fermenting fruit and honey is nearly as old as time, but there is more to consider than just tossing fruit in with honey and yeast. Matching fruit to honey varietal, processing the fruit, and contact time are just a few concepts to master when making fruit meads.

by Jason Phelps

by Jason Phelps

Whether it was because people were cooped up with free time to pick up a new hobby in 2020 or something else, one thing we can say for sure is this year’s home wine label entries were some of the best we’ve received in our 21 years of running this contest.

Home winemakers often start with 5-gallon (19-L) batches of wine. As they gain experience (and the number of friends and relatives who hear about their hobby and request a bottle increases) there often comes a time when larger batch sizes make sense. This means new equipment and considerations, which we’ll run through for anyone thinking about stepping it up. by Dominick

Profaci

Tired of making wine in various places throughout his house, Richard Hector turned an unused stall of his garage into a winery. Use his advice and plans to create your own dedicated home winery space.

by Richard Hector

by Richard Hector

8 MAIL

A reader points out differing opinions from two professional winemakers in a recent “Tips from the Pros” column, and another shares their own techniques for making country wines.

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

The 21st Annual WineMaker Home Wine Label Contest saw a slew of entries with COVID-19 themes. We compiled a few of our favorites for your viewing pleasure. Also, learn the basics to the why and when of racking and catch up on the latest news, products, and events.

14 TIPS FROM THE PROS

Two proficient meadmakers share advice for winemakers looking to make their first traditional honey wine.

16 WINE WIZARD

Sometimes we get several questions that revolve around a similar theme. The Wine Wizard had several questions this go-round on volatile acidity and malolactic fermentation. She provides some specifics for winemakers who have bigger picture problems on their hands.

20 VARIETAL FOCUS

Similar to a varietal like Malbec, Carménère has come to be identified with the wine growing regions of South America, but this grape actually was one of the classics of Bordeaux. Chik Brenneman explains the history of this varietal and how to tame this grape when it gets temperamental.

53 TECHNIQUES

There is a certain set of hobby winemakers that are happy with their current winery set up and volume. But for those that are looking to grow their hobby, here are some finer points to expanding your volume with fresh grapes.

56 BACKYARD VINES

Have you ever visited a vineyard and wondered, “How did they do that?!” You know the place, where all the vines seem to be in sync and healthy. Wes found such a hobby vineyard and decided to interview the green thumb.

64 DRY FINISH

Twenty years ago his dad was featured here in the pages of WineMaker magazine. But now that he has joined the ranks of home winemakers it’s his turn to talk about his drive to make his own wine.

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe

Dominick Profaci, Wes Hagen

Bob Peak, Alex Russan

Jeff Shoemaker, Gene Spaziani

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Jim Woodward, Chris Champine

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Charles A. Parker, Les Jörgensen

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981 Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $26.99

Cover Photo Illustration: Shutterstock.com

After jumping into some new varietals in 2019 and 2020 including Petite Sirah, Barbera, and Cabernet Franc, the grape I would be most interested in working with in 2021 is . . . drumroll . . . Chenin Blanc. The Chenin Blancs from California — especially those grown in Vouvray, Napa, and the Clarksburg AVA, have always driven my imagination. The mineral-driven, high-acid style really appeals to me as a wine drinker. As a winemaker, I always lead with my own palate — as I find making wines for myself (and an audience that recognizes that style) makes for better wines that are easier to be passionate about promoting and selling.

Being a cold-climate grape grower and winemaker, I have historically tried to maximize extractions from my red wine grape varieties to try to please my wife’s palate. She prefers dry tannic reds. There is only so much you can get out of the cold-tolerant varieties I grow, however, so I end up blending with more tannic reds from California to achieve what I am after. For 2021 I’d love to find a quality source for Tempranillo grapes to make wine from. This is one of my wife’s favorites . . . mine too, actually. I’m looking forward to a better year in 2021; hopefully with a great homemade Tempranillo to share.

PUBLISHER

Brad Ring

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

WEBSTORE MANAGER

Julie Ring

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

The path to becoming a professional winemaker can take many forms, the key is to be adaptable. Here are four winemakers from around the U.S. (one a head winemaker) to explain what they did to get their foot in the door.

https://winemakermag.com/technique/ 1235-going-pro-roundtable

MEMBERS ONLY

Whether you’re driven by quality, quantity, or efficiency — or by the high-tech joy of using the latest home winemaking toy — this guide will help you decide what specialized winemaking equipment, tools, and gadgets match your budget, annual wine production, and goals. https://winemakermag.com/ article/712-upgrade-your-home-winery

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2021 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 24, Number 1: February-March 2021

Once you have the basic concept of making wine, be it from a kit, juice, or fresh fruit, you can easily make other fermented beverages, including mead. Try using some of your new fermenting skills to make a tasty alternative to wine.

https://winemakermag.com/article/ your-first-mead

MEMBERS ONLY

Beyond a commitment to using the same grapes as those used in the great wines of Bordeaux, making a Meritage blend is mostly a matter of a winemaker’s own tastes and preferences . . . and your options are limitless. Get some pointers from pros. https://winemakermag.com/technique/ meritage-roundtable

MEMBERS ONLY

* For full access to members’ only content and hundreds of pages of winemaking articles, techniques and troubleshooting, sign up for a 14-day free trial membership at winemakermag.com

Is there a grape varietal you would like to work with in 2021 that you have not worked with before?

I read “Red Fermentation Decisions: Tips from the Pros” (from the October-November 2020 issue) and the two winemakers had basically opposite opinions so I’m not sure how inexperienced aspiring winemakers would use these tips. FYI, I’ve been a commercial winemaker for six years and I totally align with Chik Brenneman’s answers.

MikeGamble (Blue Mule Winery) • Fayetteville, Texas

WineMaker Editor Dawson Raspuzzi responds: “The expression of asking 10 doctors for their opinion and getting 11 answers notoriously applies to winemakers as well. Expressing that sentiment — that winemakers don’t all approach the process of making wine the same way — was the point behind the feature “Red Wine Fermentation Considerations” that ran in the same issue. In that article, WineMaker columnists and professional winemakers Wes Hagen and Alex Russan took different sides of various fermentation decisions that come up when making red wines and argued the merits of each side based on scientific evidence, their own experience, and some “that’s just the way I’ve always done it.” The “Tips from the Pros” column was an extension of that article, because there are certainly more than two arguments for each of the topics Wes and Alex debated.

“I understand where you are coming from that someone new to winemaking may feel lost when reading conflicting information, and we hope any readers who felt that way continued doing research on these topics, but the truth is there is no “right” way to make wine. If there was, we’d all be making the same wines and the hobby would be much less creative. Imagine never conducting process experiments or experiencing the excitement of trying a new technique? That’s what attracts so many people to this wonderful hobby!

“These ‘Tips from the Pros’ columns are intended to offer insight into what a couple of well-respected professional winemakers are doing, but it is just a snippet and nobody is going to argue that what works for one winemaker will work for another. Thank you for pointing this out and letting me get on my soapbox!”

I enjoyed the article “Making Berry Good Wines” from the June-July 2020 issue. I have been making fruit wines for almost 20 years, mostly from fresh fruit and berries that my wife and I have picked

Jason Phelps started homebrewing nearly 15 years ago, and like many hobbies it became a life changing experience. After first learning to make beer Jason branched out into cider, wine, and ultimately mead. Along the journey Jason has received more than 120 competition medals for a wide range of fermentations. As an author of articles in both WineMaker and Brew Your Own magazines, Jason loves to share his experiences and knowledge with other beverage makers. After recently retiring from a 25-year career in IT, Jason and his wife, Margot, opened Ancient Fire Mead & Cider, a producer of meads, ciders, and wines in Manchester, New Hampshire, in 2017.

Beginning on page 28, Jason shares tips, techniques, and recipes for making fruit meads.

Dominick Profaci’s interest in winemaking began by chance in 2008 when he received some excess Concord juice following an impromptu harvest at a local home vineyard. Instead of letting it go to waste, he went to a local winemaking supply shop and purchased a couple demijohns and made wine. He followed those instructions and after a number of months he was sharing palatable wine with family and friends. From there, Dominick decided to plant a vineyard at his Hudson Valley, New York home. The vineyard now encompasses more than 200 vines comprised of seven varieties of hybrid and native grapes and four varieties of table grapes.

Dominick explores the equipment and process considerations for making the move to big batch winemaking beginning on page 42.

Richard Hector, a native Oregonian, had a career as an engineer working for the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB, California. As such he was involved in management of test ranges and developmental testing of numerous aircraft and cruise missiles. He has a BS in math/physics from Oregon State, a MS in engineering from Arizona, and a MS in management from Stanford. After retiring, he and his family moved to Roseburg, Oregon in the Umpqua Valley where he planted his first grapes and started making wine in 2008. Over time his vineyard expanded to a 1⁄3-acre with Pinot Noir, Syrah, Merlot, Muscat, Pinot Gris, and Zinfandel. He named his winery “Vučetić Cellars” after his Croatian roots on his mother’s side. During the winter months, he writes sci-fi and historical fiction screenplays. In this issue, Richard shares his plans, advice, and what he learned from turning a vacant one-stall garage into his home winery, beginning on page 48.

ourselves. We have used frozen raspberries because we find picking them in the quantity needed too tedious. We have on occasion resorted to freezing the fresh berries for the reasons the author stated. But my mentor when I started suggested heating them instead. I add enough water to just cover them and then heat them on high heat on our electric range until the water steams. Just before it begins to steam you can see the color come out of the fruit into the water. You do not want it to boil — that happened once through my carelessness and the resulting wine had a burned straw flavor that persisted for a year until I threw the wine out. I then pour the heated water and fruit into a primary fermenter, add cool water to bring it up to volume, let it cool and add the other ingredients, similar to what Alex Russan recommended in the article. I typically use 4–5 lbs. of fruit/gallon (0.5–0.6 kg/L). Our wines have included blueberry, blackberry, red raspberry, strawberry, cranberry, tart cherry, black sweet cherry, apple, pear, elderberry, autumn olive, peach, apricot, pomegranate, and plum. We now use apple cider and cherry juice when making those wines because we are able to obtain them commercially and it is easier.

Although I only make fruit wines, and grape wines from kits, I enjoy your magazine immensely and read it from cover to cover. I attended the conference in Traverse City, Michigan, less than 150 miles from my home in 2019 and that was great, too. Keep up the good work!

WineMaker Editor Dawson Raspuzzi responds: “Thanks for reaching out to us — we always love to hear feedback on stories, as well as techniques home winemakers are using that may differ from the norm. We passed your email on to Jason Phelps, who frequently writes for us and has run workshops on making country wines. Following is his response, however, I would first say that if what you are doing works for you, and you’re enjoying the resulting wines, then that’s great! Like I just said in the previous letter, there are many ways to make delicious wine.”

Take it away, Jason: “I don’t recommend heating fruit to break it down for winemaking. The act of heating the fruit can set the pectins and result in a haze that won’t be as easily remedied. You also risk a cooked flavor, but the reader already found that out. The freezing part I do recommend, however. This is the best way to give your berries, cherries, blueberries, etc. a mechanism to start falling apart. The work of fermentation is going to break most fruit down, and starting with defrosting fruit can ensure that happens almost right away. The feedback about picking is something I agree with from experience. Assuming the root challenge is the fruit mass and managing it through the fermentation; that can be solved. I have always encouraged the use of nylon straining bags for fruit in wine/meadmaking. This holds the majority of the fruit pulp back, but allows for full contact during fermentation and/or flavoring. Once the desired result is achieved this fruit can be easily removed, dumped into a fruit press, and pressed out; returning the juice to the wine. If the fruit quantity is relatively small it can even be hand pressed.”

If you’re a fan of wine and cheese, today is your day to celebrate. A new study put out by a team of scientists out of Iowa State University noted that these two items can improve both cognitive function as well as combat against age-related cognitive degeneration such as Alzheimer’s disease. When the team evaluated a study of nearly 1,800 aging adults and their consumption of a broad range of food and drinks, what they uncovered was that cheese was hands down the best food to enjoy in order to protect against cognitive problems later in life. They also found that moderate daily consumption of alcohol (red wine in particular) improved cognitive function. If this topic peaks your interest, you can learn more at:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/12/201210145850.htm

Christopher Shockey and Kirsten K. Shockey turn their expertise to the world of fermented beverages in a guide to home cidermaking. With expert advice and step-by-step instructions, The Big Book of Cidermaking equips readers with the skills they need to make the cider they want: Sweet, dry, fruity, farmhouse-style, hopped, barrel-aged, or fortified. Readers will benefit from the authors’ years of experience cultivating an orchard and their experiments in producing their own ciders. This book is for any cidermaker, whether starting with apples fresh from the tree or working with store-bought juice. Cider recipes range from cornelian cherry to ginger, and styles including New England, Spanish, and late-season ciders. You can purchase a copy at better bookstores or at: https://www.storey.com/books/the-big-book-of-cidermaking/

Brewer’s Best® Kombucha Kits

A new series of kombucha recipe kits by Brewer’s Best® allows home winemakers to craft their own flavored kombucha at home. Each kit comes with the ingredients to craft one gallon (3.8 L) of fresh kombucha and is available in four flavors: Blackberry, hemp, passion fruit, and raspberry. Note that these kits do not include a SCOBY for fermentation, which needs to be purchased separately from a supplier. SCOBYs are not included since they can be reused time and again and don’t need to be started fresh each time. First time making kombucha? Each kit comes with its own detailed, stepby-step instructions for a successful batch the first time and every time.

http://brewersbestkits.com/kombucha.html

Backyard Grape Growing Online

Boot Camp with Wes Hagen

Former professional vineyard manager and WineMaker’s longtime “Backyard Vines” columnist Wes Hagen will lead an online Boot Camp for four hours detailing all the steps a smallscale grape grower needs to know: Site selection, vine choice, planting, trellising, pruning, watering, pest control, harvest decisions, plus more strategies to successfully grow your own great wine grapes. https:// winemakermag.com/product/january-29-2021-onlinegrape-growing-boot-camp

12, 2021

29, 2021 FEBRUARY

Home Wine Lab Skills Online

Boot Camp with Bob Peak

It’s very difficult to make great wine if you don’t know how to properly and accurately test your wine. WineMaker’s “Techniques” columnist and Technical Editor Bob Peak will take you step-by-step online over four hours teaching you live how to properly test your wine for sulfites, malolactic, acidity, sugar, and pH. You’ll have the chance to learn visually how to run these tests on your own wines at home. https://winemakermag.com/product/winemakersonline-home-wine-lab-skills-boot-camp

This past year all around the world, people have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and winemakers are no exception. With so many people at home it seems that many of you took advantage of the time to design labels for your wines. The 21st Annual WineMaker Label Contest saw more entries than ever before, including its fair share of COVID-19-themed labels. Here are just a few of our favorite pandemic-themed labels submitted by readers.

or anyone that has been in the hobby for a while, you’ve seen the instructions, “Siphon wine into a vessel for aging,” or some variation of that. But tips and tricks to racking often go undisclosed. Racking wine is in its essence a simple process, but can easily be done poorly and negatively impact your wine. So today we’re going to run through some basic concepts of transferring your wine and ways you can improve your process to better your wine.

Home winemakers will transfer their wines using either gravity to allow the wine to “fall” from one vessel to the other, or use an external force to either push or pull the wine into the receiving vessel. The first challenge to the transfer process is getting the line primed (filled with wine) to get the process going. Having a spigot near the bottom of your fermenter allows the transfer to occur with a simple siphon tube and the tube will self prime with the help of gravity. If you don’t have a spigot, then filling the tube with water, then submerging one end of the tube in your wine while placing the receiving vessel below allows the wine to flow from the higher spot to the lower spot. The water in the tube acts as the priming agent.

An auto-siphon is a hybrid system that can be purchased at any home winemaking or beermaking supply store. The auto-siphon starts the priming process by having the winemaker simply pull wine up into an oversized syringe-like tube. A clapper valve then closes as you push down on the syringe, forcing the wine up into the transfer line to achieve a prime.

Serious winemakers can step up to purchasing a wine transfer pump. In the commercial world there are many kinds of pumps used for various purposes:

Impeller pumps, lobe pumps, vane pumps, progressive cavity pumps, etc. But in the amateur world, diaphragm pumps are the most commonly used. They’re self priming and gentle on the wine during transfers. They can be seen in various configurations such as acting like a vacuum pump in the All-In-One Wine Pump or it can be used as an inline pump. Another mechanical way to push the wine from one vessel to another is to use compressed CO2, but this is not a common practice in the wine world.

Wine is often racked many times early in its life for a multitude of reasons. Wine kit users should try to follow the instructions found in their kit on when to transfer. For winemakers using frozen must or juice, the first racking will not occur until after primary fermentation has finished. For fresh grape winemakers, first racking often will occur after the juice has been pressed from the grapes and unwanted particulates (gross lees) have had time to settle to the bottom. A second racking may be required for bigger red wines like a Cabernet Sauvignon.

A final round of racking is often employed once the fine lees are settled and a fining agent has been employed. This will often be a final racking of the wine unless more clarification is required before packaging.

For the most part, winemakers want to utilize what I would call a quiet rack, meaning that the tube in the receiving vessel is submerged in the wine as soon as there is enough liquid to get it under. This minimizes the oxygen pickup that occurs during the racking process. To further minimize this issue, an inert gas such as argon or carbon

dioxide could be used to “purge” the receiving vessel so that the wine has minimal contact with oxygen. This would only be truly needed for more delicate wines like whites and rosés.

Splash racking is the other style of racking and that would only be desired for bigger red wines where a strong tannin presence is noted. Oxygen introduced during the splash racking process can help bind the tannins and help them elongate and eventually fall out of solution, smoothing out the wine’s profile. Notes of sulfur can also be knocked down by a splash racking. To perform a splash rack, simply remove the tubing from below the liquid level to allow the wine to mix in with the oxygen found in the vessel’s air. Splash racking should only be employed early in the wine’s life, either in the first or second racking — never after longerterm aging has occurred.

For anyone that plans to step up to making more than 5-gallon (19-L) batch sizes or has a bad lower back, there are two popular options. First is moving from a gravity-fed racking system to a pump-driven one like the ones mentioned earlier in this column. The alternative to this though is to devise a hoist system. These can be operated using either a secure ratchet, electric winch, or other mechanical lift system.

Finally a note about tubing dimensions and how they affect transfer rates. Remember back in arithmetic that the area of a circle grows exponentially based on its radius: A = πr2. So if you double your tubing’s radius, you’re not just doubling its transfer speed/volume, you’re squaring it. While this can mean much faster transfers, it also can create a lot more turbulence and potential for oxygen ingress if not handled properly. Just some factors to consider.

Want to try something new between grape harvest seasons? How about trying your hand at making mead, a wine made from honey? Meads come in many different forms — from dry to sweet, with added fruit (melomel), malt (braggot), spices (metheglin), and so on. But to get a good foundation for your meadmaking, start at the beginning with traditional mead. These pros will get you on the right track.

Ilike many different honeys for mead. The key element I look for is a really vibrant and attractive aromatic profile. There is a huge spectrum of floral aromatics — on the end I like are things like carnations, roses, and fruit blossoms. They are clear, pleasing, and smell like things you might want to put in your mouth. The spectrum gets less attractive as it goes through the less fruity, to vegetal, to earthy, and even to stuff like daisies that are nearly fecal. Citrus blossom or orange blossom has been a consistent honey that we can get in the quantities we need. We also use some wildflower, but we evaluate the lots before we buy them. Wildflower is a catch-all descriptor, and great care is required.

When choosing your own, taste a lot of honey and decide what you like. For traditionals, especially, I like honeys that really bring it, so to speak, aromatically and on the palate.

Like beer, mead is mostly made from water. Our municipal water in Detroit is very similar to the spring water we have access to, and the assay and the taste is right in the window we want so we don’t have to do any treatment. There are no real historical examples of meads from specific water profiles that determine whether or not you are “to style,” as there are in beers.

180-225 ppm of free amino nitrogen (FAN) for meads that will hit 12% alcohol. I did not know about nutrient additions when I got started, and that change (even without staggering) turned my meads around dramatically.

Yeast choice is dependent on which characteristics I want to accentuate in the honey, and what I would like to see as a finishing alcohol level. We like Lalvin 71B-1122, ICV D-254, and the Chico beer strain (yes, we do use ale yeasts). We have also used and enjoyed Steinberger and other Riesling strains.

We don’t use potassium sorbate due to distributor restrictions, but as a home meadmaker you don’t have that restriction if you make a mead that comes out drier than you’d like. Using a 5-gallon (19-L) batch as an example, at bottling, I would pull off four cups of the mead into a sanitized eight cup measuring cup, and add 1 pound (0.45 kg) of honey at a time, stir thoroughly, and mix that back into the whole batch, re-taste, and repeat until I got to the level I wanted.

I like to get off the initial fermentation lees in about 28 days. I’ll make a decision about whether to rack again once I see how much sediment is thrown in secondary. I have done some again in another month, and I have let some go a year or longer.

Ken Schramm is Owner/Head Meadmaker at Schramm’s Mead in Ferndale, Michigan, and the author of The Compleat Meadmaker, (Brewers Publications, 2013), the current reference text of record on meadmaking. Ken has been making mead since 1988. He co-founded the Mazer Cup Mead Competition in 1992, the world’s oldest and largest mead-only competition. Ken is also an avid fruit grower, and has grafted multiple varieties of cherries and apples onto trees in his orchard.

As far as nutrients go, we currently prefer a combination of DAP (diammonium phosphate) and Fermaid O. We use it in four additions, one every 24 hours, starting at the end of lag phase. I actually divide the total amount of nutrient I will use into five equal parts, and start with two for the first addition and one thereafter. We like to shoot for

The investment in time and effort to actually make your mead can be much less than in making other wines, but you need to take that time and use it to find the best possible ingredients you can find — honey, fruit, spices, whatever. What our grandparents said is true: You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. Quality in, quality out.

I did not know about nutrient additions when I got started, and that change (even without staggering) turned my meads around dramatically.

It all started back in 1995, when Michael Fairbrother tried a cyser (apple and honey mead) for the first time. Since that first sip he has developed a passion and a masterful skill at making international award-winning meads and ciders. Michael opened Moonlight Meadery in Londonderry, New Hampshire in 2010 and is President of the American Mead Makers Association. He also helped develop and has taught the meadmaking course at The Honey and Pollination Center at the Robert Mondavi Institute at UC-Davis.

For my meads I prefer the lighter-colored honeys like orange blossom and star thistle over darker honeys, which have a stronger flavor that can be a bit off-putting. The key is to taste the honey and make sure it’s something you like.

The minimum requirements to make mead are a 6-gallon (23-L) food-grade fermenter, 15 lbs. (6.8 kg) of honey, water, nutrients, yeast, and sanitizer. Even more so than with other wines, the yeast you use will make all the difference to the mead you make. My go-to yeast for meadmaking is Lalvin 71B-1122 dry yeast. I use it commercially for everything we make. As a home meadmaker I have also had good success with Lalvin 47D as well. White Labs and Wyeast also have many good choices of mead yeast.

When it comes to hitting the desired sweetness of a mead my preference is to make the mead bigger than the yeast can handle and fermenting to the desired sweetness level before

stabilizing the mead. To do this I will have a mead that starts out with a gravity greater than 1.120 and then we stabilize after primary fermentation has completed.

For a 5-gallon (19-L) batch of mead, do the following: In a small drinking glass add about 1⁄2 cup of good-tasting water. Add 1⁄4 teaspoon of potassium metabisulfite and 33⁄4 teaspoons of potassium sorbate (also called Sorbistat-K) into that water; stir until fully dissolved. Gently add this water/liquid into your 5 gallons (19 L) of mead and stir gently for about a minute. Re-seal the fermenter and let the mead sit undisturbed for 12 hours.

Excellent mead can be ready in weeks, however I tend to age my meads with a minimal bulk storage time of three months to assist in the natural clarifying of the meads.

Get more tips and a recipe from Michael Fairbrother at https://wine makermag.com/technique/traditionalmeadmaking-tips-from-the-pros

QI WAS CARELESS, AND LET AIR GET INTO A TANK CONTAINING ABOUT 60 GALLONS (227 L ) OF CABERNET SAUVIGNON. IT NOW HAS A SLIGHTLY STALE OXIDIZED TASTE. IS THERE A WAY TO RECOVER THE WINE?

JOHN BOLLES SIMI VALLEY, CALIFORNIAADon’t worry, it’s happened to the best of us! If you can, check your pH and your VA (volatile acidity) to try to get a handle on whether or not this air intrusion caused any chemistryaltering damage to the wine. What I mean is, sometimes when we have an oxygen incursion it can mean an increase in spoilage bacteria that can lead to high VAs, film yeasts, and other issues. For this reason, if you have the capability, I’d sterile filter this wine immediately to rule out the possibility of a high count of spoilage organisms in the wine. That being done, you can focus on some of the following approaches to try to “recover” the wine and nudge it back to where it was heading before it got a big oxygen shock.

Get it topped, adjust pH (if needed), and add SO2: If you can filter your wine, do it as soon as you can to remove the possibility of microbial damage. Then, adjust the free SO2 up to a healthy zone, which for a filtered red wine like Cabernet can often be 25–35 ppm, as long as your pH is under control. What I mean by under control is subjective. I’ve given up chasing the holy grail “molecular SO2” of 0.8 ppm. Molecular SO2 is a measurement based on both the pH and free SO2 of a wine, and to achieve 0.8 ppm, more often than not your pH has to be very low, your SO2 level very high, or both. Because of style and taste (hey, we want our wines to taste good, right?), getting any wine, especially a red wine, to conform to those parameters is just not real-

istic. For that reason, I choose to have my pHs for reds rest between 3.5–3.75 and my free SO2 between 25–35 ppm. I’ve found over the years that that’s a pretty good sweet spot for me, as long as I’m topping barrels monthly and monitoring my oxygen ingress as well as VA levels. Blend out the defect: Don’t forget that blending is always an option . . . as long as you have other wines. Do your winemaking buddies have some gallons they could lend you this year in exchange for replacement in a future year? In a pinch, and only with full disclosure to your friends (no bragging rights on bought wine!), I do think it’s OK to purchase a bottle or two off of the shelf to be able to blend something down. However, this probably won’t work with a 60-gallon (227-L) lot — that’s a lot of wine you’d have to buy! However, it’s likely that you’ve got other avenues, so read on below.

Try an oxidation-specific fining agent: Most winemaking supply companies (AEB, Laffort, Scott Labs, etc.) will have a fining agent that specifically targets oxidized aromas and flavors. Often, they contain PVPP, and may strip color, so do be sure you do bench trials first. Have a chat with a sales representative or check out their websites and it’s likely you’ll find something that could help.

Try refreshing with oak chips: Sometimes all a wine needs, especially a red like a Cabernet, is a little bit of oak. If your wine got a big hit of oxygen, I’m guessing it lost some of its fruit character. There are a number of oak chips on

Sometimes all a wine needs, especially a red like a Cabernet, is a little bit of oak.

the market that can help contribute not exactly fruity flavors, but elements like spice, coffee, or vanilla. These chips don’t actually have spice, coffee, or vanilla in them — they are just specifically sourced and toasted to express those characteristics in wine. For a barrel or even a carboy, you can easily make a little chip “sock” by putting small chips into a mesh or nylon bag. A nylon stocking makes a perfect single-use bag. To punch up some new aromas and add back some of the antioxidants you lost (also, see “Try a fining tannin”, below) experiment with about 1–2 g/L chip addition and see where that takes you. As always, be sure to buy chips from a reputable supplier with high turnover for freshness and best quality.

Try a fining tannin: As logic would have it, you’ve introduced oxygen, which has reacted with some of the natural antioxidants in your Cabernet (the color and tannin molecules). So it would make sense that now you have to build them back up again, right? Some of my favorite, and certainly the most

versatile, winemaking aids I’ve discovered in the last five years are the new breed of oak and grape tannins available on the market. The aforementioned winemaking supply companies all carry different kinds of tannins that can be added during fermentation, aging, or even just before bottling, to boost body, grip, or even to give a subtle oak flavor. They are extracts from oak and grape skins, typically, so are just another way of introducing some of the elements you’d get from a barrel or from fermentation. They can also do wonders in reviving and refreshing a wine that is getting tired from age or suffered an untimely accident, like yours. Again, be sure to do bench trials so you see what works and at what levels. All suppliers should be willing to give you a tiny packet or vial with which to do trials before making a purchase, and likewise should be able to guide you towards which of their products they think would work the best. Good luck — I have faith that your wine is not beyond rescue.

QBECAUSE OF TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS OVER THE PAST FEW MONTHS, I WAS UNABLE TO RACK MY 2019 ( NEW ZEALAND ) PINOTAGE FROM A SPEIDEL PLASTIC FERMENTER TO THE STAINLESS CONTAINER OR ADEQUATELY MANAGE SULFITE LEVELS ( BASICALLY I WAS UNABLE TO TRAVEL BACK FROM THE U.S. TO NEW ZEALAND UNTIL RECENTLY ). I COULD TASTE VOLATILE ACIDITY ( VA ) AND SENT THE WINE OFF FOR TESTING:

Sample Name: Pinotage 2019

Lab Number: 2452770.1

I HAVE READ THAT THE LEGAL THRESHOLD FOR VA IS 0.7 g/L AND BLENDING IS THE BEST SOLUTION. SO FAR, I HAVE ADDED ANOTHER 1 g/L OF TARTARIC ACID AND BUMPED UP THE SULFITE TO 75 PPM. UNFORTUNATELY, I DON’T HAVE ANY BLENDING WINE. IT IS OK TO DRINK, ESPECIALLY WITH FOOD, SO I AM RELUCTANT TO DUMP IT. DO YOU HAVE ANY SUGGESTIONS? I DON’T NORMALLY FILTER MY WINES SHOULD I PASS THROUGH A STERILE FILTER BEFORE BOTTLING, ANY OTHER WAY TO REDUCE THE VA OR MINIMIZE THE SENSORY IMPACT AND CAN I PREVENT IT DETERIORATING FURTHER?

ASadly, blending VA levels downward remains the only option available for reducing VA content in small lots. Larger commercial wineries, with big lots and bigger pocketbooks, can afford the expense of reverse osmosis and distillation technology to remove it from their wines but there’s no affordable option for small producers. Simple filtration doesn’t work to

remove VA, though sterile filtration can certainly remove the spoilage yeast and bacteria that may be contributing to it.

The good news for you is that your VA levels are nowhere near approaching legal limits. The legal limit for VA in the U.S. is actually 1.1 g/L for white wines, and 1.2 g/L for red wines. At these levels, I indeed do find the wine objectionable. Sensorially, at 0.6 g/L, you should be within a tolerable range, especially

for a wine that is already a year old. VA tends to climb with time and even though you had a moment during the wine’s lifetime where you weren’t able to keep the SO2 levels up in ideal ranges, it’s actually not that bad. It is possible, however,

down — that’ll help prevent some of the inevitable future VA creep. (For other reader’s reference, it always helps me diagnose a problem when I can see a wine’s analysis; it gives a bigger picture, so thank you very much for including yours!)

that you’re also smelling some aldehydes or acetaldehyde, which can smell like nail polish remover or paint thinners. If that’s the case, your SO2 addition should help bind up some of these and reduce the perception of those offensive aromas.

At a free SO2 of 35 ppm and a total SO2 of 82 ppm, I wouldn’t worry about the wine being safe to consume; it certainly is. Many wines are bottled with free SO2 in that range and though I’d certainly be wary of big additions in the future, your big add should tide you over for at least a couple of months as long as the wine isn’t exposed to oxygen and isn’t carrying a high microbial load. If you do suspect you’ve got spoilage bacteria (if you have any film yeasts growing, or if the wine is cloudy and spritzy where it should be clear and settled), you might want to filter it anyways.

I’m glad that you added some tartaric acid to get your pH

High pHs, especially coupled with oxygen exposure and low SO2, are notorious for leading you down the path to VA issues. Indeed, VA prevention is something about which an entire book can be written. Just give a search on WineMaker magazine’s website, winemakermag.com, for some great free articles and member’s-only content. VA is definitely something where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

For your wine, in your case, I’d say that if you like how the wine tastes, feel free to keep it as topped as possible, with your free SO2 levels up between 25–30 ppm, and see how it ages over the next month. I know it sounds a little blasphemous but, in the past, I have told readers (if they don’t feel like it’s breaking all the rules) that it’s OK to buy some wine to blend if it helps rescue a batch. Just be sure to tell your friends and family full disclosure that it’s not all yours . . . if it turns out tasty!

MY RED WINE MEASURES TARTARIC ACID: 50%, MALIC ACID: 25%, AND LACTIC ACID: 25% BY CHROMATIC PAPER. AT WHAT % LACTIC ACID IS IT SAFE TO ADD SORBATE SO WINE CAN BE SWEETENED A LITTLE AND NOT RISK NEGATIVE RESULTS. CAN YOU ADD A REDUCED AMOUNT OF SORBATE IF NECESSARY?

Winemakers typically add sorbate (aka sorbic acid, often purchased as potassium sorbate) when they want to bottle a wine with a little residual sugar. It is often added right before backsweetening and bottling. Sorbate will inhibit the reproduction of yeast cells but it will not “kill” yeast, nor will it inhibit or kill bacteria. It should always be added in the recommended doses; too short of a dose will not inhibit the yeast from continued growth.

As you hint in your letter, if you add sorbate before the ML fermentation is complete, you run the risk of a geranium-like

off-odor that can really ruin the aromas and flavors of your wine. For this reason, I recommend that you wait until your “malic acid spot” on your chromatograph disappears entirely, which means that you’ll have an ML complete wine.

It’s really difficult to determine the amount of lactic acid you have based on the size of a spot on a chromatograph, so I always have just gone with the “malic spot” disappearing. Because chromatography is tricky to do and somewhat inexact, I’ve always been a fan of sending in my wine for malate analysis when you think it might be done (often when you hear the little CO2 bubbles stop ‘ticking’ in the fermenter).

RECENTLY I CONDUCTED A PAPER CHROMATOGRAPHY TEST TO CHECK THE STATUS OF MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION INTRODUCED THIS FALL INTO A NUMBER OF 5- GALLON (19- L ) MARQUETTE CARBOYS PRODUCED FROM MY BACKYARD VINEYARD. RESULTS SHOWED PLENTY OF MALIC ACID STILL PRESENT. I PLAN TO COLD STABILIZE OVER THE WINTER MONTHS IN MY WINERY. WILL MALOLACTIC FERMENTATION UNDER THESE CIRCUMSTANCES NATURALLY KICK BACK IN WHEN TEMPERATURES RISE IN THE WINERY IN THE SPRING? OR IS IT BEST TO RE - INOCULATE WITH NEW CULTURE AND NUTRIENTS IN THE SPRING?

JIM BOUTIN POWNAL, VERMONTSadly, blending VA levels downward remains the only option available for reducing VA content in small lots.

I always think it’s wonderful when people can do a “natural” cold stabilization over the winter months. It’s an incredibly intuitive and very old-fashioned, non-interventionist way to accomplish a key winemaking task. It never gets cold enough here in Napa, California during the winter to really knock down any significant amount of our tartrate crystals (the goal of cold stabilizing a wine), so that’s very cool (LOL) if you can do it. I do indeed think that it’s very likely that your malolactic fermentation will re-start once the weather warms up.

Instead of re-inoculating (malolactic bacteria are expensive!) you could wait and see if you start to get any activity when the temperatures start to rise. You can do this by monitoring the disappearance of the malic acid spot on your paper chromatography test. In addition, you can also listen at the mouth of your carboys for the little “tick . . . tick . . . tick” of carbon dioxide bubbles being produced by an active malolactic fermentation.

To be sure that you’re detecting any change, do a chromatography measurement right before you put your wines out in the cold to start stabilizing. On your paper, since the spots will fade over time as the solvent degrades, very carefully (don’t touch the paper with your hands, use gloves as the solvent is toxic) draw a pencil line around the little malic blob. This way when you test again in the

springtime months, or whenever you believe malolactic fermentation has resumed, you’ll be able to see if the size of your spot has shrunk and if activity has indeed kicked back into gear.

If you don’t see any signs of activity after the weather has been warm (above 55 °F/13 °C) for a few weeks, and if you’ve tried things like bringing your carboys inside or wrapped them with electric blankets, then it’s time to consider re-inoculating. Make sure that the alcohol isn’t too high (>14.5% is inhibitory), the pH too low (<3.3 is inhibitory), or the temperature too low (>55 °F/13 °C is ideal).

I’m so glad that you mention malolactic nutrients! So many people just toss in a bunch of bacteria and hope for the best, not realizing that malolactic bacteria are even more fastidious in their nutritional needs than yeast cells are. Especially since the wine has been sitting for a while, it’s possible that many things have fallen to the bottom of the vessel or have been consumed (albeit slowly) over the winter’s nap and are now unavailable. Re-supplementing with a nutrient at this time is key.

Additionally, be sure not to add any SO2 as malolactic bacteria are extremely sensitive to sulfur dioxide. Hold that addition until you have confirmed completion. Good luck with your cold stability, and I hope that your wine does reignite its malolactic fermentation in the spring. If not, re-inoculating is nothing to be ashamed about!

Almost ten years ago my wife Polly and I visited the city of Bordeaux in the southwest part of France and toured its famed surrounding wine country. A truly memorable experience that ranged from pop-up wine tastings, gastronomic indulgences, and the much-revered activity of dodging pigeon bombs in the city center. But why the trip was also most memorable is that I got to really understand the region’s geography, soils, grape varieties, and why these specific varieties were grown where they were. Years earlier as a student of wine I couldn’t quite grasp Left Bank versus Right Bank, they were just lines and dots on a map. But there it was right in front of me, and it all started coming together. The sun, the winds, the microclimates, the geology . . . Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot, and Malbec; were all starting to make sense.

But there were more varieties it seemed as I teased through my limited French language skills and our guide telling us that some words just do not translate very well . . . kind of like Inuit language and their 50 words for snow. It made sense with such a long history of wine growing in the region that there had to be more than just the “big five.” Returning home and slightly jet-lagged, I was reading more and understanding more about the region and I came across another red variety that must have been what our hosts were talking about. Certainly not obscure in the wine world, just not a lot of it left in post-Phylloxera Bordeaux, and it blends (pun intended) into the landscape with those big five.

Carménère is an old variety from the Gironde region of France. It is a vigorous red grape varietal with small clusters and medium-sized berries. Its leaves are the typical Bordeaux shape with five slightly overlapping lobes, and an upper leaf sinus with a tooth at the margin. If this sounds like a couple of the other Bordeaux reds, then you are correct. The DNA parentage has recently established that Carménère is a natural cross between Cabernet Franc and Gros Cabernet, an even older variety from the Gironde and the Tarn, which was often confused with Cabernet Franc.

Gros Cabernet is now largely uncultivated, however, the DNA truth seekers have determined that Carménère and Cabernet Franc have a high level on consanguinity, or common ancestry. It turns out that Carménère is both a progeny and great-grandchild of Cabernet Franc, a half sibling of both Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. That explains all the confusion between them and what our hosts were talking about on that trip to Bordeaux. The confusion does not stop at Bordeaux, and thanks to the DNA truth seekers, many of the Cabernet Franc and Merlot vines of Italy, Chile, China, and California, were determined to actually be misidentified Carménère. China took it a step further in 1892 and imported cuttings under the name Cabernet Gernischt, German for “mixed Cabernet,” which refers to the broad ampelographic group called Carmenet. And here I thought it was hard to get my head around the family tree I married into!

The Phylloxera epidemic of France in the 1860s really changed how the Carmenet ampelographic group was

Make the best from this old Bordeaux varietal

The DNA parentage has recently established that Carménère is a natural cross between Cabernet Franc and Gros Cabernet . . .

125 lbs. (57 kg) Carménère fruit

Distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution. (Weigh 10 grams of KMBS, dissolve into about 50 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g Lallemand D254 yeast

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

5 g Go-Ferm

5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

Malolactic Fermentation Starter Culture (CHR Hansen or Equivalent)

OTHER EQUIPMENT OR NEEDS SPECIFIC TO THIS RECIPE

15-gallon (57-L) food-grade plastic bucket for primary fermentation

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

1–2 one-gallon (3.8-L) jugs

Racking hoses

Destemmer/crusher

Wine press

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 81–86 °F (27–32 °C)

Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–43 °C) in one degree increments.

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 mL

Tartaric acid – addition rate is based on acid testing results.

1. Clean and sanitize all your winemaking tools, supplies and equipment.

2. Destem and gently crush the grapes. Transfer the must to your bucket.

3. During the transfer, add 15 mL of 10% KMBS solution (This addition is the equivalent of 50 ppm SO2).

4. Take a sample of must to test for Brix, acidity, and pH. Keep the results handy. We’ll take this up later.

5. Layer the headspace with inert gas and keep covered. Keep in a cool place overnight.

6. The next day sprinkle the Fermaid K directly to the must and mix well.

7. Go back to those lab results you took yesterday. Typical Brix for this style is 24–25 °Brix. Typical acid levels will be 0.58–0.62%. Adjust as nec-

essary using tartaric acid. If the acid is higher than 0.7%, don’t panic, this recipe calls for a minimum final acidity of 0.55%. Higher acid won’t hurt here.

8. Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 108 °F (42 °C). Measure the temperature. Pitch the yeast when the suspension is 104 °F (40 °C). Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature of the yeast and the must temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). To avoid temperature shock, acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. When the yeast is ready, add it to the fermenter.

9. You should see signs of fermentation within about 1–2 days. This is referred to as the “cap rise.” You need to have on hand the ability to push the grapes back into the juice to promote color, tannin extraction, and to distribute the heat produced by the yeast. This is called “punching down” and this should be done three times per day. Use a clean utensil to mix.

10. Monitor the Brix and temperature twice daily during peak fermentation (10–21 °Brix). Morning and evening is best and more often if the temperature shows any indication of exceeding 86 °F (30 °C) in which case place frozen water bottles (or Chiller apparatus) into the fermentation then mix. Wait 15 minutes, mix and check the temperature again. Do this as often as it takes to keep the temperature between 81–86 °F (27–32 °C). Do not cool off to less than 81 °F (27 °C). Alternatively, you may need to keep the must warm in a colder climate.

11. At about 19 °Brix, sprinkle in the DAP and punchdown.

12. When the Brix reaches 4 °Brix (about 4–5 days), transfer the must to your press, and press the cake dry. Keep the free run wine separate from the press portion for now. Be sure to

label your vessels.

13. Transfer the wine to your carboy and 1-gallon (3.8-L) jugs. Your press fraction may only be 1–2 gallons (3.8–7.6 L). Make sure you do not have any head space. Label the vessels.

14. Inoculate with your malolactic (ML) bacteria. Check the manufacturer’s instructions on how to prepare and inoculate. Cover the tops with an airlock to allow CO2 to escape.

15. Monitor the ML fermentation using a thin layer chromatography assay available from most home winemaking supply stores. Follow the instructions included in the kit.

16. When the ML is complete, add 2 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon (3.8 L) of wine. This is the equivalent to ~40 ppm addition.

17. Measure the pH and titratable acidity. Most importantly you want a finished TA of about 0.55–0.6%. The pH is secondary but should be around 3.6. Add acid to adjust prior to settling. Place the wine in a cool place to settle.

18. After two weeks, test for SO2, adjust the SO2 as necessary to attain 0.8 ppm molecular SO2. (There is a simple SO2 calculator at winemakermag.com/ sulfitecalculator). Check the SO2 in another two weeks and adjust. Once the free SO2 is adjusted, maintain at this level. You’ll just need to check every two months or so and before racking.

19. Rack the wine clean twice over a 6–8 month time frame to clarify.

20. Once the wine is cleared, it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about eight months after the completion of fermentation. Make the project fun by having a blending party to integrate the press fraction back into the free run. You may not need it all, use your judgment and make what you like. Fining with egg whites may be necessary to tame the tannins.

21. Filtration is generally not needed if SO2 levels are maintained and there are no surface films or indications of subsequent fermentations. If all has gone well to this point it can probably be bottled without filtration. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling. Once bottled, you’ll need to periodically check your work by opening a bottle to enjoy with friends.

distributed in Bordeaux. Both Malbec and Carménère were widely planted, but in the post-Phylloxera world, Malbec did not graft to rootstock well and Carménère was subject to poor fruit set and inconsistent yields. Thus, their respective vineyard acreage decreased in France . . . only to be introduced in other parts of the world where they both performed very well and made some nice wines. Carménère’s current power base is Chile where it was planted as a field blend with Merlot and, given the long history of ampelographic confusion, most growers probably thought it was all Merlot. Though some writers will debate that the growers did know the difference and they were designated Merlot and Merlot Chileno, the latter name in reference to Carménère.

This varietal flourished in warm, dry climates like those found in Chile, eastern Washington, California, and China. Of these regions, Chile has the lion’s share of vineyard area. The key was the ability to set fruit, something that was not a given in its native Bordeaux, which is largely a maritime environment. Typical to the Carmenet family of grapes, early harvested grapes from this family are notorious for strong notes of herbaceous, capsicum (bell pepper) aromas from

elevated methoxypyrazine levels. As the fruit hangs longer, these flavors morph to red berry, black pepper, tomato, and, when the berries are perfectly ripe, blackberry, blueberry, chocolate, coffee, and soy. But at this late stage there is a significant reduction in acidity, which requires adjustment to rebalance the wine. Needless to say, the fruit benefits from longer hang times but the winemaker needs to step in, and where permitted, make appropriate acid adjustments.

So, what is an appropriate acid adjustment? The winemaker must first understand why an acid adjustment is necessary. In the case of Carménère and other varieties that benefit from longer hang times, it has to do with the berry’s main source for carbon. Prior to veraison, the berries use glucose as their main source of carbon for respiration while accumulating malic acid. Ever taken a bite of a green berry before or at veraison? Everyone does once. At veraison, the berry reverses gears and starts to accumulate sugar while now utilizing the malic acid reserves for respiration. These reserves can be depleted significantly, and I have seen little or no malic acid in grape musts at crush. This is why, as winemakers, understanding the pH, acidity, and actual malic acid concentrations in your musts are the key to balanced

It is important to note that varieties that are high in polyphenolics can also show increased bitterness and perceived astringency.

wine. An understanding of when it is best to make these supplements is beyond the scope of this “Varietal Focus” column but suffice to say, Carménère in warmer climates often will need a little work by the winemaker.

It can be a tannic wine, and also of deep red color. Recent research has indicated that it has a different polyphenolic profile than other Carmenet members. A lot of this interest is not just understanding the color and flavor profiles of the grape, but the correlated potential health benefits associated with polyphenolic compounds: Heart health and cancer prevention. Carménère has very high concentrations of anthocyanins, specifically malvidin, flavonols, quercetin, myricetin, and the flavanols; catechin and epicatechin. All of these compounds increase in the berry as a result of indirect sunlight exposure while they undergo extended hang time. To promote indirect sunlight exposure, strategic leaf pulling on the shady side of the canopy is necessary. As Carménère is classified as a vigorous variety, this is also necessary to promote good airflow through the fruiting, which also promotes good penetration of sprays.

It is important to note that varieties that are high in polyphenolics can also show increased bitterness and perceived astringency. So when working with these wines careful processing will moderate the extraction of these compounds into the must. At the destemmer/crusher for example, it’s preferable to have the ability to adjust the rollers so that the berries are just fractured as opposed to rollers that macerate the berry and crush the seed. In the study I reviewed for this piece about half of the tannin measured was seed tannin, which is perceived more bitter than astringent. Seed tannin can be mechanically extracted as previously described or extracted by extended maceration of the must. I recommend pressing at seven to ten days. When pressing, watch your press cuts by tasting as the pressure builds. Keep the press fractions separate to possibly blend back in later. I always say, don’t put any more in that you may have to take away later.

Circling back to that Bordeaux trip

with my wife. Our hosts drove us all around the region, visiting chateau after chateau. At one chateau, the bookkeeper even came out and tasted with us, as he was bored preparing reports for his ownership group. Everyone needs to unwind sometimes.

Meanwhile the city of Bordeaux proper was undergoing a noisy renaissance of sandblasting the dark molds from the stone buildings. Looking at the newly renovated building facades

revealed many old murals hidden by the years. Polly and I enjoyed standing back a little way from the buildings to see it all come together . . . similar to the way the matrix of vineyards and varietals comes together in harmony in Bordeaux and its famed wines. Carménère is one of the many grapes that make this part of France such an amazing wine region. While it may now be better known as a New World grape, its roots are found in Bordeaux.

ENTER YOUR BEST HOMEMADE WINES IN THE WORLD’S LARGEST COMPETITION FOR HOBBY WINEMAKERS!

DON’T WAIT — SEND YOUR ENTRIES NOW!

ENTRY DEADLINE: MAY 11, 2021

Enter your wines and compete for gold, silver and bronze medals in 50 categories awarded by a panel of experienced wine judges. You can gain international recognition for your winemaking skills and get valuable feedback on your wines from the competition’s judging panel.

Entry Deadline: May 11, 2021 5515 Main Street • Manchester Center, VT 05255 ph: (802) 362-3981 ext. 106 • fax: (802) 362-2377

email: competition@winemakermag.com

You can also enter online at: www.winemakercompetition.com

will be awarded thanks to our award sponsors:

Grand Champion Wine

WineMaker of the Year

Best of Show Red

Retailer of the Year

Best of Show White

U-Vint of the Year

Best of Show Dessert

Club of the Year

LALLEMAND BREWING

Best of Show Mead

Best of Show Country Fruit

Best of Show Sparkling

Best of Show Estate Grown

Best of Show Kit/Concentrate

Category Medals (gold, silver and bronze) will be awarded thanks to our category sponsors:

19. White Vinifera Bordeaux

34. Red Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

Gino Pinto Inc.

35. Blush Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

36. Grape & Non-Grape Table Wine Blend

37. Apple or Pear Varietals or Blends

38. Hard Cider or Perry

39. Stone Fruit (Peach, Cherry, Blends, etc.)

40. Berry Fruit (Strawberry, Raspberry, Blends, etc.)

41. Other Fruits

42. Traditional Mead

43. Fruit Mead

Moonlight Meadery

44. Herb and Spice Mead

Ancient Fire Mead & Cider

45. Flower or Vegetable

46. Port Style

47. Sherry Style

48. Other Fortified

33.

49. Sparkling Grape, Dry/Semi-Dry or Sweet

50. Sparkling Non-Grape

1. Entry deadline for wines to arrive is May 11, 2021

Wines are to be delivered to: Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street Manchester Center, VT 05255 Ph: (802) 362-3981

2. Send ONE (1) BOTTLE per entry. Still wines must be submitted in standard 750 ml wine bottles. Ice wines or late harvest wines can be submitted in 375 ml bottles. Meads and Hard Ciders can be submitted in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must be in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire. All bottles must be free of wax, decorative labels and capsules. However, an identification label will be required on the bottle as detailed in rule #5.

3. Entry fee is $25 U.S. dollars (or $25 Canadian dollars) for each wine entered. Each individual person is allowed up to a total of 15 entries. You may enter in as many categories as you wish. Make checks payable to WineMaker. Only U.S. or Canadian funds will be accepted. On your check write the number of entries (no more than 15 total) and the name of the entrant if different from the name on the check. Entry fees are non-refundable.

4. All shipments should be packaged to withstand considerable handling and must be shipped freight pre-paid. Line the inside of the box with a plastic trash bag and use plenty of packaging material, such as bubble wrap, around the bottles. Bottles shipped in preformed styrofoam cartons have proven reliable in the past. Every reasonable effort will be made to contact entrants whose bottles have broken to make arrangements for sending replacement bottles. Please note it is illegal to ship alcoholic beverages via the U.S. Postal Service. FedEx Air and FedEx Ground will destroy all amateur wine shipments so do not use either of these services. Private shipping companies such as UPS with company policies against individuals shipping alcohol may refuse your shipment if they are informed your package contains alcoholic beverages. Entries mailed internationally are often required by customs to provide proper documentation. It is the entrant’s responsibility to follow all applicable laws and regulations. Packages with postage due or C.O.D. charges will be rejected.

5 Each bottle must be labeled with the following information: Your name, category number, wine ingredients, vintage.

Example: K. Jones, 9, 75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch, 2016. If you are using a wine kit for ingredients please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients. Example: K. Jones, 22, Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon, 2016. A copy of the entry form, listing each of your wines entered, must accompany entry and payment.

6. It is entirely up to you to decide which of the 50 categories you should enter. You should enter each wine in the category in which you feel it will perform best. Wines must contain a minimum of 75% of designated type if entered as a varietal. Varietals of less than 75% must be entered as blends. To make sure all entries are judged fairly, the WineMaker staff may re-classify an entry that is obviously in the wrong category or has over 75% percentage of a specific varietal but is entered as a blend.

7. Wine kits and concentrate-based wines will compete side-by-side with fresh fruit and juice-based wines in all listed cate gories.

8. The origin of many Native American grapes is unknown due to spontaneous cross-breeding. For the purposes of this competition, however, the Native American varietal category will include, but is not limited to, the following grape families: Aestivalis, Labrusca, Riparia and Rotundifolia (muscadine).

9. For sparkling wine categories, dry/semidry is defined as <3% residual sugar and sweet as >3% residual sugar.

10. Contest is open to any amateur home winemaker. Your wine must not have been made by a professional commercial winemaker or at any commercial winery. No employee of WineMaker magazine may enter. Persons under freelance contract with Battenkill Communications are eligible. No person employed by a manufacturer of wine kits may enter. Winemaking supply retail store owners and their employees are eligible. Judges may not judge a category they have entered. Applicable entry fees and limitations shall apply.

11. All wines will be judged according to their relative merits within the category. Gold, silver and bronze medals within each category will be awarded on point totals and will not be restricted to the top three wines only (for example, a number of wines may earn enough points to win gold). The Best of Show awards will be those wines clearly superior within those stated catego-

Entry deadline for wines to arrive in Vermont: May 11, 2021

Wines judged: June 11–13, 2021

Results first announced at the WineMaker Magazine Conference in San Luis Obispo, California July 17, 2021

(Results posted on winemakermag.com)

ries. The Grand Champion award is given to the top overall wine in the entire competition.

12. The Winemaker of the Year award will be given to the individual whose top 5 scoring wine entries have the highest average judging score among all entrants.

13. The Club of the Year, Retailer of the Year and U-Vint of the Year awards will be based on the following point scale: Gold Medal (or any Best of Show medal): 3 points

Silver Medal: 2 points

Bronze Medal: 1 point

The amateur club that accumulates the most overall points from its members’ wine entries will win Club of the Year. The home winemaking retail store that accumulates the most overall points from its customers’ wine entries will win Retailer of the Year. The U-Vint or On-Premise winemaking facility that accumulates the most overall points from its customer’s wine entries will win U-Vint of the Year.

14. The Best of Show Estate Grown award will be given to the top overall scoring wine made with at least 75% fruit grown by the entrant. Both grape and country fruit wines are eligible.

15. All entrants will receive a copy of the judging notes for their wines. Medalists will be listed by category online.

16. All wine will become the property of WineMaker magazine and will not be released after the competition.

17. All decisions by competition organizers and judges are final.

Deadline: May 11, 2021

Entry Fee: $25 (U.S.) or $25 (Canadian) per wine entered

Number of entries _____ x $25 (US) or $25 (CD) = $________Total (limit of 15 entries per person)

q Enclosed is a check made out to “WineMaker” in the amount of $_________.

Name___________________________________________________________________________

Address_________________________________________________________________________

City________________________State/Prov______Zip/Postal Code____________________

Telephone_______________________________________________________________________

E-Mail____________________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Club:________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Retailer:_____________________________________________________________

U-Vint / On-Premise Store:________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage: Please list fruit varieties and percentages used in each wine. Example: “75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch.” If you are using a wine kit for ingredients, please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients.

Example: “Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Wine 1 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ____________________________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 2 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 3 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

winemakercompetition.com

Remember that each winemaker can enter up to 15 wines. If entering more than eight wines, please photocopy this entry form. Entry shipment includes ONE BOTTLE of wine per entry. 750 ml bottle required for still wines. Ice or late harvest wines can ship in 375 ml bottles. Still meads can ship in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must ship in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire.

Send entry form and wine to:

Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Ph: 802-362-3981 • Fax: 802-362-2377

E-mail: competition@winemakermag.com

If entered online at winemakercompetition. com, please print a copy of your entry form and send it along with your wine.

Wine 5 Entered:

Category Number_________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 6 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 7 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 4 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Enter online at: winemakercompetition.com

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 8 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

eads containing fruit are a perpetually hot topic amongst home meadmakers as well as being a huge part of the commercial mead conversation. Taking what we know about making mead from just honey and then adding fruit doesn’t seem to be all that complex of a leap, but I assure you that the adventure of smashing fruit and honey together is way more interesting than just saying, “I made fruit mead!” Making mead with fruit is a creative journey. What fruits and combinations you use, where and when you use them in the process, and what attributes of the fruit you work to express are all creative choices. Unlocking the secrets of all these different choices is the key to being able to mix them up to create your own hits.

As with any adventure, it is best to jump right in!

(5 gallons/19 L, bottled under cork)

OG = 1.152

FG = 1.028

ABV = 16%

16 lbs. (7.3 kg) wildflower honey

2.5 gallons (9.5 L) 24 °Brix Black

Muscat grapes

2 Tbsp. pectic enzyme

Water to 5 gallons (19 L)

20 g Lalvin KV1116 yeast

10 g Fermaid-K

2.5 g diammonium phosphate (DAP)

1.67 g potassium metabisulfite

4 g potassium sorbate

STEP BY STEP

Prepare the pectic enzyme by mixing with a small amount of 65 °F (18 °C) tap water. Crush the grapes, mix the pectic enzyme mixture with them and perform a two-hour cold soak prior to pressing off the juice. The grape pomace can be discarded.

Combine grape juice, honey, and water to 5 gallons (19 L).

Re-hydrate and pitch the yeast. Degas and feed nutrients at 24, 48 and 72 hours. Ferment to target final gravity and stabilize with sorbate and metabisulfite. Rack off sediment. Bottle under cork.

The above directions results in an “orange” pyment due to the skins not being part of the ferment. This was a creative choice. Fermenting with the skins will produce a much darker color, but even more of the specific grape character as well.

At Ancient Fire Mead & Cider (where I’m the Owner/Meadmaker) in Manchester, New Hampshire, we produce three different product lines, including draft style meads, draft ciders, and honey wines. We use fruit in a number of different ways in all of these products. We are constantly dreaming up new combinations and innovative ways to layer fruit, honey, and other ingredients to make delicious new beverages.

This adventure is also based on a whole bunch of questions. Here are some I get from meadmakers all the time: What kinds of fruit should I use? Should I combine different fruits? How do I handle and prepare whole fruit? How do I integrate fruit into my process? Are juices and concentrates good to use, and if so, how? Are there specific fruit combinations that work really well together? How about any that don’t? Got any secrets to share?

Let’s take a look at a recipe for an example of using fruit in mead, in this case wine grapes. In the fall of 2018 I acquired Black Muscat grapes from California through Musto Wine Grape Company. We used the grapes to make a 15.5% ABV honey wine named 60% Of The Time (a recipe for a 5-gallon/19-L version of this recipe can be found to the left).