IMPORTED BY

Phil Plummer was one of the experienced judges at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition. After three days of judging he found himself repeating similar comments on numerous entry sheets. Now he’s here to explain in greater depth the most common flaws he tasted and the techniques that can be employed to avoid them in your next vintage.

by Phil Plummer

by Phil Plummer

No two fermentations are the same, which means that there is always more to be learned with each one! Give your yeast the best chance for success by creating an ideal environment for a clean fermentation.

by Jenne Baldwin-Eaton

by Jenne Baldwin-Eaton

Chemical and microbial stability measures must be taken after fermentation but prior to bottle aging to protect the wine from contamination and subsequent off-aroma generation caused by microbial metabolism. Learn the most common methods for achieving microbial stability, both during aging in the cellar and at packaging.

by Dwayne BershawWhether it’s a decadent red, crisp white, or robust rosé, Master Vintner® Sommelier Select® brings you grapes from the world’s best wine regions, that you’ll be proud to share with family & friends.

8 MAIL

A reader searches for insight on making spiced wines such as one he recently tried at a winery. The secret may be in the name: Glühwein (more commonly known as mulled wine in North America).

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

Learn about the lees that we find in wine and how we can use them to our advantage. A creative winemaker tells the backstory for a homemade wine label. We also share the latest news, new products, and upcoming events.

14 TIPS FROM THE PROS

Fall is here and there is an abundance of apples available and ready to be fermented. Three experts share advice for three different types of hard ciders (fruited, spiced, and hopped) so that you can try something different this year.

16 WINE WIZARD

With wildfires on the rise in many wine regions around the world, smoke taint has become a common phrase. Learn about it and ways winemakers may be able to try to make the best from affected grapes. Also learn about Campden tablets, getting news on grape growing conditions, and some other pearls of wiz-dom.

20 VARIETAL FOCUS

With origins in Spain, Garnacha grapes may now be more commonly associated with the Rhône and Languedoc-Roussillon region of France where it’s known as Grenache. Learn about Garnacha’s background and making the best version of wine with it.

46

Tannins are a big piece of the large puzzle when balancing many styles of wine. It’s important to understand ways to increase or decrease their presence when that balance leans too heavily in one direction or the other.

49

Once you have your site selected, soil figured out, as well as irrigation; it’s time to start planning things like row and vine spacing, what type of wine grapes you are going to grow, and then finally what trellis system will best support those vines.

56

Considered one of the great wine regions back in the days when Phoenicians ruled the Mediterranean Sea, Israel is seeing a big comeback in recent decades. Get the scoop on the burgeoning commercial and hobby scene in this holy land.

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Dwayne Bershaw, Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe, Wes Hagen,

Maureen Macdonald, Bob Peak, Phil Plummer, Dominick Profaci

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Jim Woodward, Chris Champine

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Charles A. Parker, Les Jörgensen

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus

EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

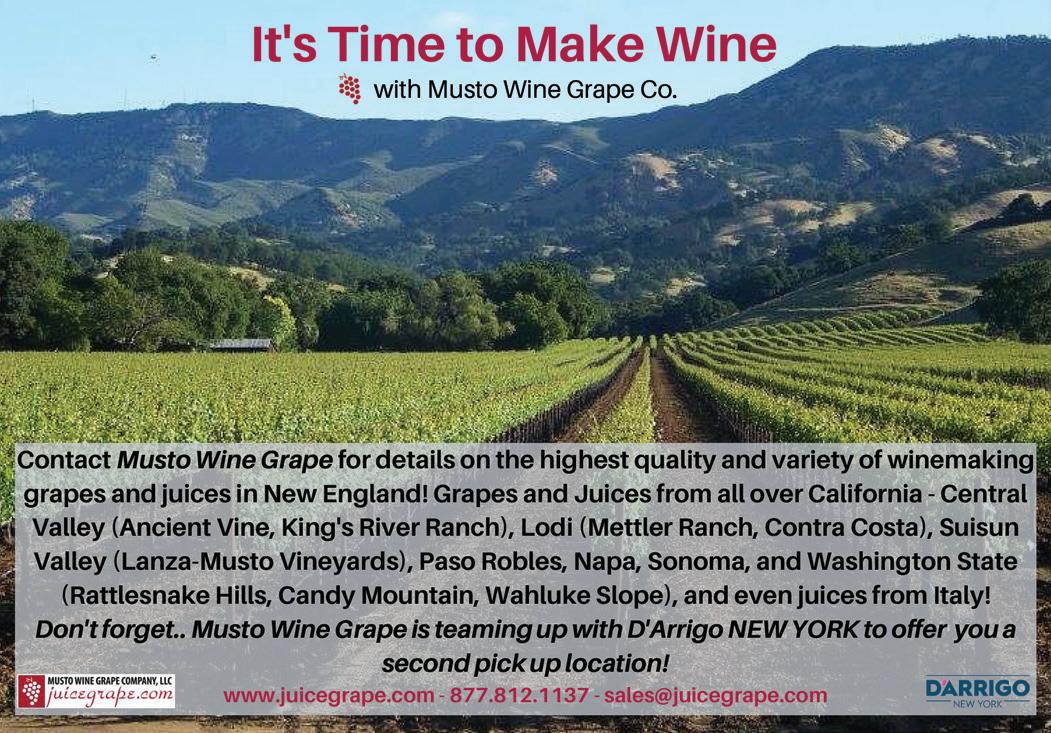

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Phil Plummer Montezuma Winery

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981

Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $29.99

Cover Photo: Shutterstock.com

PUBLISHER

Brad Ring

QASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER

SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

Sulfites get a bad rap in the world outside of true wine aficionados. Take a journey through the world of sulfites and understand some of the various philosophies regarding its use throughout the winemaking process. https://winemakermag.com/article/ so2-fundamentals

MEMBERS ONLY

My choice for red wines is EC-1118. It is relatively bulletproof. Good alcohol tolerance, temperature range, nutrient requirements are basic. If you are looking for yeast characteristics, this is not the one to use, but most of those yeast characteristics are gone by the time a red wine is ready to drink, anyway.

Oh man, do I have to pick just one?! If that’s the case here’s what I’d say: For the part of the world where I make wine (New York’s Finger Lakes), I’m not sure there’s a more versatile red wine yeast strain than Anchor’s Exotics Mosaic. In our cool climate, Mosaic’s ability to drive rich texture, minimize underripe aromas, and partially degrade malic acid are all highly desirable characteristics that help us to craft structured, ageworthy red wines from hybrids and vinifera alike.

A few years ago Anchor came out with the Alchemy series of yeast. They are a blend of compatible yeast strains that work together in a single fermentation to make some really complex results. My favorite for reds (this week) is Alchemy 4 — it can really support fruit character and makes a wonderful mouthfeel in the wine.

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2022 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 25, Number 5: October-November 2022.

While a winemaker does not need to know the chemistry of polyphenols and tannins to make good wine, some basic knowledge can help drive winemaking decisions that may improve the outcome of any given vintage. https://winemakermag.com/ technique/tannin-chemistry-in-wine

Winemakers in Chateauneufdu-Pape in the southern Rhône region are happy to have 13 grapes to work with, permitted by the appellation rules. Blending plays a large part in how they have made wines of great distinction for hundreds of years. https://winemakermag.com/ article/674-the-joys-of-blending

MEMBERS ONLY

Whether it is choosing a yeast strain, halting fermentation with a little residual sugar, putting a wine through malolactic fermentation, or a myriad of other options, there is a lot to consider when fermenting white wines. https://winemakermag.com/article/ white-wine-fermentation-decisions

MEMBERS ONLY

* For full access to members’ only content and hundreds of pages of winemaking articles, techniques and troubleshooting, sign up for a 14-day free trial membership at winemakermag.com

I recently had some spiced wine called Glühwein at Duck Creek Winery in Denmark, Wisconsin that they sold bottled. The label didn’t list the spices included only that it was 10% ABV. They don’t have it listed on their website currently. I suspect it might be a seasonal wine for them. I’d like to make my own but I’m not finding recipes except ones you’d make on the stove with a bottle of wine. Would you have suggestions where I might find a recipe?

Scott Sanford • via email

As you may know, “glühwein” is the German name for mulled wine and is made in the same way as described in the articles we’ve run on mulled wine. These wines are most often created by using a red wine that is heated on the stove along with spices and fruits. They can then be served hot or chilled and are popular in the winter months around the holidays not just in North America, but across the world. That said, we wanted to make sure that is in fact what Duck Creek was doing. Jim Ploetz of Duck Creek responded and, while he isn’t sharing many secrets, he did provide some insight into the spices he uses.

“We do make a glühwein, we release it usually around the end of September. It’s a family recipe and really would like to keep it a winemaker’s secret. It is made from a red wine and has some clove and cinnamon in it. The wine can be served warm or at room temperature. We have had a lot of customers come in and say that it is very close to what they had when they were in Germany . . . The Germans serve this around holidays.”

With all of this said, our recommendation if you wanted to make an entire batch of spiced wine to bottle would be to approach it in a different way, more similar to how homebrewers spice beer or aperitifs (such as sweet vermouth) are made. In these processes, instead of adding spices for a quick extract in a heated liquid, you would make a tincture of each spice by adding the spice to vodka. After a week or two, remove the spices and add the tincture to the wine (after doing trials to dial in the right amount of each based on taste). This method will likely result in a clearer wine than bottling a heated and then cooled mulled wine.

If you are interested in making a mulled wine, Bob Peak wrote a great story on the subject with spicing recommendations in the October-November 2021 issue, which digital members can also read online at: https://winemakermag.com/article/mulled-wine. Bob also wrote a piece on making aperitifs, which will be helpful if you choose to go the tincture route, available at: https://winemakermag.com/article/aperitifs

Phil Plummer has been a student of wine since 2004 when he began his formal education in the subject at Rochester Institute of Technology. For the past 11 years, Phil has worked for the Martin Family Wineries (Montezuma, Idol Ridge, and Fossenvue) in New York’s Finger Lakes Region, serving as Head Winemaker since 2013. In his time as Head Winemaker, he has developed a diverse portfolio of unique wines made from grapes, fruit, and honey. Phil’s passion for wine and winemaking is boundless, as evidenced by his constant experimentation with new techniques, materials, and mindsets.

Starting on page 28, Phil revisits his time judging at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition and the most common flaws he saw and how to address those issues in the cellar.

Jenne Baldwin-Eaton has been a winemaker in the Colorado wine industry for the past 28 years. Hired as a lab chemist in 1994, she progressed to Head Winemaker in 1999 for Plum Creek Cellars, one of the largest and most award-winning wineries in Colorado. In 2017, she started the first Colorado Associates of Applied Science in Viticulture and Enology program at Western Colorado Community College, a division of Colorado Mesa University. Jenne says the motivation behind starting the program and teaching was to help integrate what had been learned by the Colorado grape growing and winemaking pioneers with the current experimentation of the next generation. Although recently retired from academia, Jenne has a long-standing passion for the Colorado wine industry and continues to support, educate, research, and consult with her community.

Jenne makes her WineMaker writing debut beginning on page 34 as she outlines the keys to a successful fermentation, which all begins with happy yeast.

Dwayne Bershaw began making wine in his garage in 2006 while working as an engineer in Silicon Valley. The passion grew and in 2010 he received a master’s degree in viticulture and enology from UC-Davis. He has four years of experience in a variety of temporary positions in Sonoma and Napa County wineries, and served four years as the Associate Director of the Southern Oregon Wine Institute at Umpqua Community College where he taught all of the enology coursework. There he was also responsible to schedule and manage production of 300–700 cases of wine per year with student participation at the school’s commercial winery. Since 2015 he has held a lecturer position in the food science department at Cornell University.

Beginning on page 40, Dwayne explains how to protect our wine from the moment fermentation is complete through to bottling by making it microbially stable.

In the August-September 2022 issue of WineMaker, we reported on a big potential breakthrough in the fight against glassywinged sharpshooters, a scourge of California grape growers. In another breakthrough, scientists say they may have found the pathway and potential cure for grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs). GTDs are a fungal issue that has caused an estimated $1.5 billion in annual damage to vineyards according to a study done in 2012. Eutypa dieback and esca are two commonly known GTDs. The researchers found that a mix of reduced iron (Fe2+) and hydrogen peroxide combine in a complex interaction among several fungal species and are released into the wood. It is here that combination can prove deadly to grapevines because it releases free radicals. Free radicals are the reason we are told to take our antioxidants . . . they’re not good for any living creature.

The good news is that this combination of iron and hydrogen peroxide should be easily stopped by antioxidants and a common compound we know as chelating agents. So what is a chelating agent? It’s a chemical compound that reacts with metal ions to form a watersoluble, stable complex. They can be found in our food, in cleaning products, in medicines (such as cancer treatments), and water treatment systems, among other uses. So potentially by treating the wounds (growing fungi) on the grapevine trunk with a chelating agent and antioxidants, the reduced iron can be removed from the equation and hydrogen peroxide can be turned to water. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.921961/full

The new GOvent from GOfermentor allows users to get a real-time estimate of the alcohol levels in their wine. By replacing your airlock with their alcohol estimator, which gauges the carbon dioxide gas released, you can graph and monitor the progress of your fermentation from anywhere using the optional Android/iOS app. The accuracy is +/– 0.25% ABV in closed fermenters up to 30 gallons (120 L) of wine, beer, mead, and other fermentations. There is an LCD display and WiFi internet connection is required for remote access. https://www.GOfermentor.com

The new RQ series from RJS Craft Winemaking, the Charisma line, sources grapes from the Southern Hemisphere countries of Australia and South Africa. There are five options to choose from: A Chenin Blanc-Chardonnay-Viognier blend; a Grenache-Shiraz-Mourvèdre blend; a Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc blend; a Pinotage varietal; and a Merlot varietal.

https://rjscraftwinemaking.com/restricted-quantities-2023/

OCTOBER 7, 2022

Registration deadline for the American Wine Society (AWS) 2022 Amateur Wine Competition. Open to all amateur winemakers and includes still, fortified, and sparkling wines made from vinifera, native, and hybrid grapes. Also judged by certified judges will be wines and ciders made from fruit, vegetables, flowers, honey, and grasses. Pre-registration is required and the cost is $25 (AWS member) / $35 (non-member) per entry. For more information visit: https://www.awscompetitions.com/on-line-entry

OCTOBER 31, 2022

Judging for the 49th Annual U.S. Amateur Winemaking Competition will take place on November 12 & 13, 2022. Entries will be accepted from August 15 through October 31. Entries should be shipped to or dropped off at The Home Wine, Beer, and Cheesemaking Shop in Woodland Hills, California. Fees are $20 per entry. The U.S. Amateur is sponsored by the Cellarmasters of Los Angeles Home Winemaking Club. More information and registration forms can be found at www.CellarmastersLA.org

Here is a list of medal-winning kits for the Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot categories chosen by a blind-tasting judging panel at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition in West Dover, Vermont:

Cabernet Sauvignon

SILVER

Winexpert Reserve Cabernet

Sauvignon

BRONZE

Finer Wine Kits Forte Series

Cabernet Sauvignon

VineCo Estate Series Cabernet

Sauvignon

Winexpert Eclipse Three Moons

Cabernet Sauvignon

Winexpert Private Reserve Lodi Ranch II California Cabernet

Sauvignon

Merlot

SILVER

Winexpert Private Reserve Napa Valley Stag’s Leap Merlot

BRONZE

ABC Cork Fontana Washington

Merlot

Finer Wine Kits Lodi Merlot

Mosti Mondiale L’Originale Merlot

RJS Craft Winemaking En Primeur

Merlot

RJS Craft Winemaking Grand Cru

Merlot

VineCo Passport Merlot

Winexpert Classic Chilean Merlot

Winexpert Eclipse California

Merlot

when you register now. We look forward to seeing you in Oregon in 2023!

MICHAEL CONNOR • COVENTRY, CONNECTICUT

MICHAEL CONNOR • COVENTRY, CONNECTICUT

Iam of Irish descent and wanted to create a label that paid homage to not only my Irish roots but also to the many past and present amateur home winemakers in my family. A green outline of Ireland serves as the backdrop for this label.

Conchobar (pronounced as konx-o-var) is, according to online sources, the old Irish source name for my surname and our Irish family crest is emblazoned with an oak tree, a symbol of strength. Both the oak tree and winery name are displayed in the top section of the label with two acorns under the winery name.

The bottom section of the label contains two beagles looking at each other. Conchobar means “lover of hounds” (or lover of canines depending on the source) and our family just happens to have two beagles (Bo and Stanley) who highly resemble those found on the label.

All images on the label are public domain or copyright-free images with countless hours spent trying to choose the right ones. I hope you enjoy both the aesthetics and meaning behind the label.

From the sun-kissed plains of the Alentejo wine region to the terraced hillside vineyards of the Douro River valley to the charm of Porto, what’s not to love about Portugal? Join WineMaker Magazine for a comprehensive Portugal wine vacation visiting remarkable wineries and port wine lodges with in-depth wine tastings and winery tours geared towards our group of home winemakers. We will visit the Vinho Verde DOC, Douro River valley, and Porto in the north, and the Alentejo wine country further south outside of Lisbon. Along the way we’ll visit a cork forest, delight in vineyard picnics, take a local cooking class, enjoy a Rabelo boat ride down the Douro River, explore several historic cities, and stay in luxurious hotels each night. Join us for an immersion in a rich wine experience in Portugal! For more details visit: winemakermag.com/trip

hile this issue’s topic is really more of an intermediate to advanced concept and technique in winemaking, there is no reason beginning winemakers should not be thinking about these techniques as they advance. Let’s start with the basic idea of what lees are, the process of sur lie aging, and how bâttonage fits into the picture.

In the broadest sense of the term, lees are what fall to the bottom of a fermenting or aging vat of wine. Winemakers generally will split lees into two classes, each with their own set of characteristics. Gross lees are generally the first to precipitate to the bottom of your fermenter, usually within the first 24 hours after the grapes are pressed. These include grape skins, MOG (material other than grapes), seeds, stems, dead yeast, and tartrates, among other things. It is preferred that gross lees are removed after they have settled since they can contribute off-flavors.

Fine lees take longer to settle and they mainly consist of dead yeast cells. These take days to settle, even weeks, and unlike gross lees, can greatly enhance the body of a wine. This is why some of the great wines of the world, e.g., Champagne, are aged on the fine lees. While it is traditional to age some wine on the lees, not all wine is meant to be aged on them. So let’s take a spin through why you may want to use them.

So what makes fine lees so special to winemakers? Well we can’t talk about them without understanding autolysis and mannoproteins. The term autolysis refers to the breakdown of the dead yeast cells that have precipitated out of the wine. While this decom-

position may seem like something winemakers would like to avoid, the dead yeast release a class of compounds from the cell wall known as mannoproteins. These compounds are a natural enhancer to the mouthfeel and body of a wine.

Mannoproteins will also interact with tannins, reducing the astringency and harshness that can be associated with excess tannins. The benefits of mannoproteins doesn’t stop there . . . they also can stabilize a red wine’s color, inhibit tartrate crystallization, and reduce both oxidation and protein haze. Winemakers can find products that will provide them via inactivated yeast like Enartis Pro Uno.

So while winemakers often want to remove the gross lees, as we just found out, aging wine on the fine lees can have many benefits. The only downside with aging on fine lees can be in the extreme example that they completely run out of oxygen in solution and start to produce hydrogen sulfide. This can easily be taken care of by racking wine, which will both remove the wine from the lees and reintroduce a little oxygen to solution.

First off, winemakers using kits or juices are at an advantage here since most will contain very limited amounts of gross lees. The fine lees will be the vast majority of the lees that settle to the bottom of their fermenters. Fresh grapes on the other hand will need an extra step to separate the two forms of lees. Since gross lees will settle within roughly 24 hours and fine lees take longer, we can use the physical discrepancy to our advantage. After pressing the grapes, winemakers can allow the gross lees to settle for 24 hours, then rack the wine off the gross lees. Then most of the fine lees will slowly settle to the bottom over the course of the next several days.

Sur lie aging simply means that the winemaker has aged their wine on the lees. An important element to sur lie aging is the bâttonage process. This is simply a French term for stirring the wine and in doing so, mixing the lees back into solution. Why would winemakers want to do this? There are several reasons. First is that it can speed up the autolysis process and the release of the mannoproteins into your wine. Second, if your wine is going through the malolactic fermentation process, the stirred lees can better provide nutrients to the bacteria as well as scavenge oxygen from solution, which the bacteria likes. Finally, the bâttonage process prevents the yeast from compacting on the floor of your fermenter, which can cause problems such as creating hydrogen sulfide gas.

Just be sure to be very gentle while stirring since you want to minimize the introduction of oxygen. Carboys and demijohns can simply be rolled around on their rim so you don’t actually need to even open the fermenter. For larger tanks or when aging in barrels, there are special tools winemakers can utilize for the stirring process.

So how often do you want to perform the bâttonage process on your wine when aging on the lees? While there is no hard and fast rule, the general answer from professional winemakers is every 2–4 weeks. If all you’re doing is rolling the carboy around, then every two weeks seems reasonable. If you have to open your fermenter and stir, you may want to do it every four weeks to minimize oxidation issues.

For a deeper dive into the science and different stylistic approaches to lees and sur lie aging, I recommend: https://winemakermag.com/technique /lees-and-you-dead-yeast-can-beyour-friend

After you’ve made a couple batches of hard cider it is fun to branch out to some more unique styles. In this column, we ask for advice from three cidermakers to make fruited (Incline Cider), spiced (Meriwether Cider), and hopped (Jason Phelps) hard cider.

For our fruited ciders we primarily use fruit juice as purees can be a bit harder to work with, needing some more attention on the filtration. For the majority of these ciders we add the fruit additions post-fermentation. I think the advantages of adding post-fermentation are the consistency it lends us for the end product and the ability to replicate a recipe. Co-fermenting apples with other fruits is a lot of fun — it is an additional world that is worth exploring, but, it also brings several new variables into the mix.

The ratio of apple-to-fruit depends on the end result you are looking for. Do you want to really sweeten something up or just add a touch of fruit flavor? Do you want to obtain color from your fruit addition? For most single-strength juices I’d say 5:1 appleto-fruit is an easy place to start. Some juices will take a lot to shine through the cider and others just a touch. Just experiment and have fun with it.

We generally utilize a similar blend of apples to make most of our base ciders and do not tweak that apple mix to account for later fruit additions. This is part of keeping things consistent and of high quality for us. When sourcing apples I would suggest seeking out a place near you that offers fresh-pressed juice instead of getting too hung up on the variety. There is an enormous world of apples to explore but that would be my recommendation for a good jumping off place — something you can replicate and hopefully have some continued access to. I started making cider in

Arizona and at the time finding freshpressed juice was gold — there was not easy, local access to any specific apple varieties.

We have a house yeast for most all of our ciders (including these fruited ciders) that we find accentuates our apple mix. However, for some smaller projects I enjoy experimenting with different yeast strains from the beer and wine worlds.

As winemakers and cidermakers know, it is all about experimenting and finding out what works for your style. There is no right or wrong way to make a fruit cider. If I had the flexibility of a home winemaker making small batches I’d probably spend a little more time playing with co-fermentations and making some sour ciders with fruit additions. I’d recommend that home winemakers try co-fermenting as well as adding fruit post-fermentation. Experience the differences of working with the same fruit in different ways. If you can get to a point where you are making a consistent apple cider, playing with different juice or puree post-fermentation additions are a great way to build out some recipes.

Working on a home winemaking scale really provides an opportunity to source high-quality, single-strength juices without breaking the bank at most mainstream grocers. Aim for juices without additives or funky extras, as generally the shorter the ingredients list, the better. When you only need a gallon or so (4 L), even utilizing whole fruits and juicing them yourself with a hand press, blender, or juicer is a great option. If you can’t find watermelon juice, just make your own!

I’d recommend that home winemakers try co-fermenting as well as adding fruit postfermentation. Experience the differences of working with the same fruit in different ways.Jordan Zehner is a Co-Founder of Incline Cider Company in Tacoma, Washington. Since 2015, operating an independently owned, family-run cider company requires and allows Jordan to be a part of just about all business operations from product development, to marketing and design, to accounting. He focuses on creating unique yet approachable hard ciders.

e make a lot of ciders with different spices and herbs in them. To get the most flavor out of the spices, 99% of the time we add them post-fermentation, however the approach varies depending on the specific spice. We use tinctures when the zest of a citrus fruit is used or when a dried herb/ botanical is used in the flavoring. For fresh spices like hops, basil, etc. we dry hop where we let the spice sit in the cider in a mesh bag until the right flavor is obtained (let your palate be your guide).

These styles of cider can be dry or sweet. Personally, I’m more of a dry cider guy and love our hopped cider, which I think needs to be dry because it allows you the delight of hop flavor and aroma without the bitterness. Also that slight sweetness in the hops balances well with the dry cider. If I were to choose a sweeter cider it would be our grapefruit rosemary cider. The tartness and bitterness of the grapefruit zest tincture and juice is balanced by backsweetening with apple juice.

We don’t do anything different with

For dry-hopped cider I generally add 0.25–0.5 oz. of hops per gallon of finished cider (2–4 g/L). I’ll typically leave those in contact for three days, and if I want more hop character I’ll dry hop a second time after removing the first addition. Any longer and I begin to pick up a grassy, herbal character and a building astringency. Hop lightly for a short period of time.

I have found that many hops have far too much character and can easily overpower a cider. One of my all-time favorites is Nelson Sauvin, which includes descriptors of white wine grapes, gooseberry, and passion fruit. These are all great matches for apple and the lightly floral aromas from the cider. I have also tried some European hops that might not be thought of as aromatic powerhouses, but have very complementary features. Hallertauers, including my own backyard grown ones, have been the most reliable hops for me to get a subtle, pleasant hopping without any concerns that I’ll have gone

apple or yeast selection for these spiced ciders. We generally stick with a five-apple blend making sure the Granny Smith with its tartness dominates. This blend has worked very well for us but on occasion we use crab-apple and foraged apple blends for experimentation. We’ve also tried small batches of New Town Pippins and Granny Smith as single varietals and it has worked well for us. Our house yeast is made for Champagne and/or white wine and is what we use in 95% of our ciders and then backsweeten post-fermentation. However, we have 5-gallon (19-L) carboys everywhere experimenting with new yeasts and apple juice combinations.

For home winemakers, my advice is if you’re collecting apples around your neighborhood to crush and press, make sure you have a combination of apples that have tannins, tartness, and sweetness. Post-fermentation, make both orange and lemon zest tinctures (zest of a lemon and orange, add ~6 oz./177 mL of vodka to each, shake, and let sit for a day or five), filter the zests out, add enough sweet apple juice to balance and add each tincture slowly until it pleases your palate. It’ll make a great summer cider!

too far in 2–3 days.

One area I experimented with commercially was the use of hot-fermenting kveik beer yeasts like Hornindal and Voss to ferment ciders (these strains work best in the upper 90s °F/mid-30s °C). What I was looking for was how that aromatic profile is different in the outcome overall, but I also wondered if that could lead to hop pairings that did not work as well with ciders fermented with traditional wine or ale yeasts. We dry-hopped one of these ciders with Mosaic® hops, and the combination of the earthy, fruity cider with the big hop aromas was delicious. Outside of that, I typically recommend ICV D47, ICV D21, or 71B1122 for traditional cider ferments — all of which work well with hopped ciders too. These are reliable at 62–65 °F (17–18 °C). With a good nutrient program they lead to clean ferments at a good pace with lots of pleasant aromas retained and without the hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production that cider is notorious for in rushed ferments.

QDO YOU SEE ANY OPPORTUNITIES FOR NEW STYLES OF WINE MADE FROM SMOKE -TAINTED GRAPES? HAVE YOU TASTED ANY COMMERCIAL EXAMPLES PURPOSEFULLY USING SMOKE -TAINTED GRAPES?

BRIAN COX MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIAAI’ve heard rumor that a couple of smaller wineries that have experienced smoke taint in their grapes are indeed evolving that wine into new styles. Depending on the grape type and level of impact, it’s possible their base wines may have a wide array of “smoke effect” descriptors like: Bacon-y, deli meat, barbecue, toasty, etc., which all can be positives in the right place. As long as a wine isn’t completely objectionable (think old ashtray or cigarette butt), it’s perfectly sensible to me to try to work with what you’ve got. In some cases, winemakers are layering on a lot of oak, or doing one of these Bourbon-barrel style wines, which lean heavy on the toasty oak and seek to make a feature of the smokiness, rather than perceive it as a flaw. How well are these wines selling and how consumers are perceiving them I couldn’t tell you as I don’t have any insight there; but I do know some folks are getting creative when they are working with grapes and wines with a somewhat smoky character.

In general, smoke taint is a new phenomenon as wildfires have really only been a part of winemaking in the past 5–10 years. The research on the subject is still fairly nascent and there is still so much we don’t know. For what it’s worth, I would like to tell our readers some basic facts about smoke taint in grapes and wines as well as some of my personal observations:

• Smoke-affected grapes and wines are

still safe for human consumption.

• Many of the “smoky” compounds that can be signs of smoke exposure in grapes and wine are actually desirable in many wine styles. In fact, many are the exact same chemical components that winemakers purposefully put into wines in the form of toasted oak barrels, chips, beans, etc.

• Smoke-taint research is still in its infancy. Experts still disagree about which markers to use to track evidence of smoke taint, what level of smoke exposure is a risk, and even the definition of what smoke taint is.

• Just because there is smoke in the air doesn’t mean your grapes and wine will exhibit smoke taint in the finished wine.

Anecdotal evidence from my winemaking community includes:

• After about a year of age the wine will express whatever smoky characteristics it’s going to.

• Spending a lot of money to send wine and grape samples into fancy labs like ETS is practically meaningless as the numbers don’t seem to correlate well to actual aroma or flavor intensity of defects in the wine.

For more information about smoke taint in grapes and wine, I recommend visiting the Australian Wine Research Institute’s (AWRI) website.

There’s a lot more that I could write about the topic. But in the meantime, yes, feel free to experiment with some new wine styles if ever you are faced with a smoky vintage!

In some cases, winemakers are layering on a lot of oak, or doing one of these Bourbon-barrel style wines, which lean heavy on the toasty oak and seek to make a feature of the smokiness, rather than perceive it as a flaw.Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com Some characteristics found in smoke-tainted wines are the same that can be found in toasted oak barrels.

I’VE GOT A RECIPE THAT SUGGESTS I SHOULD CRUSH AND DISSOLVE A CAMPDEN TABLET AND ADD IT TO THE GRAPE MUST ( I’M PLANNING ON MAKING A RED WINE FROM SOME SPARE CABERNET AND MERLOT I’LL BE ABLE TO PICK UP FROM A FRIEND THIS HARVEST ) BEFORE FERMENTATION. WON’T THIS KILL OFF THE YEAST?

AThe great thing about Campden tablets (a convenient form of dosing in sulfur dioxide for home winemakers) is that they will inhibit the yeast and bacteria you do not want (which are sensitive to sulfur dioxide) while allowing the yeast you do want to continue to power through the fermentation.

Longtime readers of my column know that I almost always inoculate my wines with a commercial yeast strain (purchased from a reputable dealer) that is specifically chosen for my wine’s conditions. Since you’re doing a red wine in the Prosser area, I’ll figure you’ll be able to get your grapes plenty ripe . . . and that you’ll need a yeast strain that can tolerate a temperature up to about 95 °F (35 °C) and an alcohol up to 15%. This will provide the best chance at a complete fermentation.

A purchased yeast is grown and formulated to tolerate a little bit of sulfur dioxide and I almost always add around 35-50 ppm total sulfur dioxide at the crush pad in order to inhibit ambient bacteria and to suppress “wild” yeast that could spoil an entire batch. By dosing your grapes with a little sulfur dioxide, you’re making sure your yeast will be able to power through your fermentation safely while “bad bugs” and their “bad behavior” will be repressed.

One crushed Campden tablet in one gallon (3.8 L) of wine produces about 65 ppm (or mg/L) of total sulfur dioxide. Since I’m not sure which recipe you’re referring to in your question I can’t quite tell you if one tablet is too much or not. Just be sure you don’t use more sulfur dioxide or Campden tablets than a recipe calls for. Measure twice, cut once, and ferment on!

QIS THERE A WEBSITE OR ANOTHER RESOURCE I CAN USE TO CHECK TO DETERMINE WHETHER THE GROWING CONDITIONS WERE FAVORABLE IN A PARTICULAR AVA BEFORE I BUY GRAPES FROM THAT AREA?

STEPHEN BOYLE COLONIA, NEW JERSEYASometimes local AVA (American Viticultural Area) groups will have data available on their websites or emails available to members (the latter is the case with, for example, Napa Valley Vintners). For the most part, however, home winemakers won’t be members of these kinds of groups (they can cost thousands of dollars to join) so they will have to seek out data independently.

Many viticulturalists and winemakers I know subscribe to newsletters and data services like those from Western Weather Group (westernweathergroup.com) or Weather Bell (weatherbell.com). You can look up forecasts for a given area, current conditions as well as browse searchable and downloadable historic data in order to get an idea of how an area is progressing. Sadly, these are not wine-specific in any way, though most will provide an agricultural-based data set like degree days from certain dates, etc., which can help predict when grapes will ripen.

This kind of forecasting and historical weather information isn’t free, however. For example, Weather Bell costs $270/year for a personal/non-professional subscription and $660/year for a professional/business subscription. It might

be worth poking around the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) website at www.ncei.noaa.gov/ cdo-web/ because it does seem to offer current and historical data and is searchable by state, county, or zip code. It’s a big clunky website, however, so it might take a little digging to find things that will be of specific interest to you. In the few minutes I spent on the website, I was able to find degree-day data as well as precipitation data for the Napa area over certain date ranges.

Numbers are only numbers, however. Actually getting in the vineyard and checking out the fruit and canopy, even two or three months before harvest, can give you a great idea about what the year has done so far. For example, this year, as I was touring our Russian River vineyards, I could visually see that in some cases the winter hail damage we had caused a lot of berries to not set, and the vines were setting a bunch of second crop. If you can possibly go to visit a vineyard yourself that’s always best, but if you can’t, if you’ve got connections in the area or if you can have the vineyard owner send you pictures or just talk you through what’s going on in an area, it all will help you to make a decision.

One crushed Campden tablet in one gallon (3.8 L) of wine produces about 65 ppm (or mg/L) of total sulfur dioxide.

I REALLY ENJOY YOUR COLUMN AND HAVE BEEN A BIG FAN OVER THE YEARS. I’VE EVEN HEARD YOU SPEAK AT SOME OF THE WINEMAKER CONFERENCES, WHICH ARE ALWAYS REALLY FUN. I LOVE THE WAY YOU PUT THINGS AND LOVE YOUR BITS OF “WINEMAKING WIZ- DOM” THAT YOU SHARE WITH US. IS THERE ANY WAY YOU COULD DISTILL DOWN FOR ME SOME OF YOUR “PEARLS OF WIZ- DOM” IN ONE OF YOUR COLUMNS? IT’D BE FUN TO SEE WHAT YOU THINK ARE SOME OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AXIOMS OF WINEMAKING.

STACY BEAMER SAN CARLOS, CALIFORNIAAThanks for your kind words! I always really enjoy the WineMaker Conferences and connecting with the readership — it helps me put names and faces to the invisible readership out there and I so much enjoy doing a little “Wine Wizard Live.” So, in an attempt to take up your challenge, here are some snippets of “Wiz-dom” (as you put it, lol) that I do seem to find myself repeating in the columns and in my talks . . . consider it a lovingly-edited “Best of” list from me to you!

1. Your wine is only as good as your starting material.

2. Acid is the backbone of a wine.

3. Learn the science behind the art.

4. Listen to your wine. Let the wine tell you the path it needs to tread, don’t force it.

5. Don’t take wine, or yourself, too seriously.

• The single most important decision a winemaker can make for a wine is when to pick or selecting raw material if you don’t buy grapes (but I assume many of you do).

• Timing of the harvest will guide you on the path to what the wine will (or won’t) become. This is already laid out before you. The key is knowing how to read which path to take.

Pressing: Press cuts — take them if you can!

Maceration: You get most of your color in five days anyway and I’m not sold on the benefits of an extended maceration, it really just increases your biogenic amines as well as ups your microbial load.

1. Start with sanitation. Know the difference between cleaning and sanitizing. Cleaning is rote soil removal. Sanitizing is killing unwanted microbes *after* cleaning removes many of them. An effective sanitizing solution is the following:

3 g sulfite powder

12 g acid

1 gal. (3.8 L) water

2. You want happy yeast! Nutrition balance is key. If you can get your juice and must tested, shoot for 300 ppm YAN (yeast assimilable nitrogen) using a non-DAP containing yeast nutrient, and only add DAP in small amounts, and not after 5 °Brix.

3. Acid adjustment. Do it as early as possible in the must/ juice stage. Try to have reds finish out with a pH of 3.45–3.65, whites under 3.60. Be sure to have your wines go through malolactic fermentation unless you will filter and/or hold cold/bottle early.

4. Air is your friend during fermentation. Yeast needs oxygen to build their cellular membranes.

5. If you add copper, measure it! Don’t just use copper fittings. 6. Try fermenting on oak! It can fix color, add sacrificial tannins, and start your wine off on the right footing.

1. Don’t overthink it.

2. Go native only if conditions allow it.

3. I use PDM except for QA23 for Chardonnay.

4. If you have lots of separate containers and can predict what your conditions will be, it’s OK to use some fancy specific yeasts.

5. A complete fermentation should be your goal. Dealing with a stuck fermentation is hard for home winemakers.

1. A topped container is a happy container!

2. Ullage management, volatile acidity (VA) management, film yeast management . . . these are all key to keeping spoilage microbes from invading and ruining your wine during aging.

3. Air is good when you need to rack.

4. Don’t let a nasty lees reduction layer accumulate at the bottom of your containers; it can cause H2S (hydrogen sulfide, i.e., rotten egg smell).

5. Check free SO2 every month and after every big move.

6. Ideally check VA every month when you check free SO2 — this helps you keep track of a wine’s microbial health.

1. “Winemaker, step away from the barrel!” i.e., don’t over-oak your wine or attempt to hide flaws.

2. A full barrel is a happy barrel. Keeping the barrel topped up will help ensure safe, well-aged wine with no oxidation or VA problems over its lifetime.

3. Definitely consider the wonderful world of chips, barrel inserts, and staves. They’re ideal for small batches. Radoux, Barrel Mill, G3/Boise Vivelys are all good lines, but most coopers and oak companies will offer non-coopered oak.

1. Never blend a loser, i.e., don’t throw good wine after bad.

2. Look for “what’s missing” and try to find wines to fill the slot.

3. Don’t be afraid to try 0.5%–5% . . . a little of something can make a big difference.

4. Trade wine to create blends with your winemaking friends or club members.

5. Don’t be afraid to buy a commercial bottle of wine to get a few mLs to top up your carboy. It’s OK, I won’t tell anyone!

6. Explore finishing tannins, arabinols — add sweetness and roundness with non-fermentable sugars.

1. Time is the best fining agent.

2. I don’t tend to fine my wine, especially with animal products. It often just isn’t necessary. My sole exception is for my whites: Bentonite and then use Celstab/ CMC to avoid cold stabilization issues. It’s a game changer!

1. Picking grapes too early or too late.

2. Inappropriate must adjustment.

3. Not understanding the destructive power of oxygen.

4. Not understanding the constructive power of oxygen.

5. Keeping inadequate records.

Most importantly: Keep good records, do your bench trials before making additions, and HAVE FUN!

Winemaking itself is an accumulation of experiences starting from our first day, and over the time that follows we build on our knowledge base. We have all had little crush pad accidents, chemical addition errors, blending mistakes, and coming up short on bottles on the magical day. Oh, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Then we sit down with our friends and many bottles of wine on the table, and start to talk about that time when something happened. In the end, you and your friends end up laughing about it. That’s the way I like to admit my mistakes . . . over wine and laughter.

I covered this grape variety before, back in the April-May 2011 issue, but I didn’t give it many positive descriptions. I told readers it was a fickle grape with poor color and tannin structure. But my opinions have changed over time with more experience, not just with our focus on this issue’s variety but also with how I approach winemaking. Our topic today is Garnacha and I am taking an alternative look at some misconceptions I may have provided readers with previously. I cannot believe I couldn’t say everything good about the variety that is one of the most abundant in the world.

Garnacha is an old variety that has undergone many mutations. I have previously focused on Garnacha Tinta and Garnacha Blanco, but here we’ll bring in the Roja and Peluda versions as well. As the name implies, Garnacha was thought to be Spanish in origin. But, there’s always another theory

when it comes to Old World varieties. On the Italian island of Sardinia it has been known as Cannonau for centuries, hence raising the speculation that it is in fact an Italian variety. According to The Wine Bible by Karen MacNeil, both versions of the story are plausible. Without too much nitty-gritty detail, both Garnacha and Cannonau started appearing in historical records about the same time, but author Jancis Robinson leans towards its origins being Spanish in nature. Later, as it spread into France in the 18th century, it took on the French name Grenache as it was planted and grown across the south of the country.

Viticulturally the variety is drought tolerant with early budding and late ripening, making it ideal for growing in warm, dry climates. It is a vigorous variety but sometimes this doesn’t show through when grown in sandier soils. It is susceptible to downy mildew, Phomopsis, Botrytis bunch rot, grapevine bacteria necrosis, grape moth damage, and millerandage. (In case you didn’t know, millerandage is more commonly known as shatter or coulure (FR.) where there is incomplete fruit set due to adverse weather conditions at flowering.)

Garnacha can mature with very high sugar levels while maintaining moderate acidity levels, which vary depending on the cropping level. Color can be challenged with higher crop levels. Its longevity can be attributed to its relative resistance to esca (black measles) and Eutypa dieback. It can grow in lightly acidic soils, gravel or stony soils, and soils high in limestone. It is best pruned as headtrained vines.

The most notable blend combination is with Syrah (Shiraz) and Mourvèdre (Monastrell), more commonly known as the GSM blend . . .

A grape with many facets

This is a simple way to make Garnacha from juice concentrate. Kits and fresh grapes are also available for this variety. If using a kit, be sure to consult the manufacturer’s specifications included with the kit for specific directions. If using juice concentrate, this recipe is a good guideline.

(5) 46-oz. (1.36-L) cans Garnacha or Grenache juice concentrate (~68–70 °Brix)

3.5 gal. (13.2 L) distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 grams of KMBS, dissolve into about 50 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g EC-1118 (Lallemand or Scott Labs). Red Star Premier Cuvee can be used as a substitute.

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

5 g Go-Ferm

5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

Malolactic fermentation starter culture (CHR Hansen or equivalent)

6-gallon (23-L) food-grade plastic bucket for fermentation

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

1–2 one-gallon (3.8-L) jugs (optional)

3-gallon (11-L) carboy (optional)

Racking hoses

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 70–75 °F (21–24 °C)

Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–43 °C)

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 mL

Clinitest® tablets to measure residual sugar

1. Clean and sanitize all your winemaking tools, supplies, and equipment.

2. If refrigerated, warm distilled water to about 65 °F (18 °C). You will use 3.5 gallons (13.2 L) to dilute the concentrate. Add five cans of the juice concentrate, using the water to completely dissolve remaining concentrate in the

can. Mix well. In the end, you will have about 5.5 gallons (21 L) of juice in the bucket at about 22.5 °Brix.

3. Layer the headspace with inert gas and mix Fermaid K or equivalent yeast nutrient into the juice.

4. Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 108 °F (42 °C). Mix the Go-Ferm into the water to make a suspension. Take the temperature. Pitch the yeast when the suspension is 104 °F (40 °C). Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature of the yeast and the must temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). To avoid temperature shock, acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. Do not let the yeast sit in the original water suspension for longer than 20 minutes. When the yeast is ready, add it to the fermenter.

5. Initiate the fermentation at room temperature (75 °F/24 °C). You should see signs of fermentation within about one to two days. This will appear as some foaming on the juice.

6. Monitor the Brix and temperature twice daily during peak fermentation (10–21 °Brix). Maintain temperature between 70–75 °F (21-24 °C).

7. At about 15 °Brix, dissolve the DAP in a small amount of water and add to the fermenter.

8. When the wine is consistently less than 0 °Brix, inoculate with your malolactic (ML) bacteria. Check the manufacturer’s instruction on how to prepare and inoculate the malolactic bacterial culture.

9. Monitor the ML fermentation using a thin layer chromatography assay available from most home winemaking supply stores. Follow the instructions included in the kit.

10. When the ML fermentation is complete, add 2 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon (3.8 L) of

wine. This is the equivalent to ~40 ppm addition.

11. Place in a cool spot to settle.

12. Consider adding some French and American oak chips. Do not treat the entire lot of wine. Rather break down the 5 gallons (19 L) to smaller vessels and treat one of the fractions to blend back later.

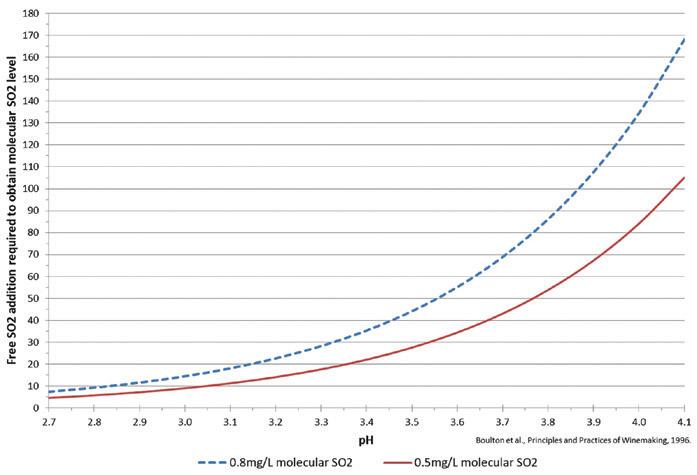

13. After two weeks, test for pH and SO2. Adjust the SO2 as necessary to attain 0.8 ppm molecular SO2. (There is an SO2 calculator at www.winemak ermag.com/sulfitecalculator). Check the SO2 in another two weeks and adjust. Once the free SO2 is adjusted, maintain at this level. You’ll just need to check every two months or so, and before racking.

14. Rack the wine clean twice over 4–6 months to naturally clarify. Fining and/or filtration are generally not needed if SO2 levels are maintained and there are no surface films or indications of subsequent fermentations. Consult the magazine website for tips on fining and filtration if problems are evident.

15. Once the wine is cleared, it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about six months after the completion of fermentation.

16. Make the project fun by having a blending party to integrate the oak fraction back into the unoaked fraction. You may not need it all, use your judgment and make what you like.

17. If all has gone well to this point, given the quantity made, it can probably be bottled without filtration. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling. Once bottled, you’ll need to periodically check your work by opening a bottle to enjoy with friends. Have fun!

The recipe calls for specific additions of sulfur dioxide at specified intervals. Once these scripted additions are made, you must monitor and maintain 30–35 ppm. Adjust as necessary using the potassium metabisulfite solution described or other methods. Testing can be done at a qualified laboratory or in your home using one of the commercially available kits.

The Blanca (SP.) and Blanc (FR.) have the same viticultural characteristics, with the exception of mid-budding and less susceptibility to shatter. The Roja (SP.) and Gris (FR.) versions are a little more productive than Garnacha Blanca. The Peluda (SP.) version is characterized by downy undersides of the leaves; smaller, thick-skinned berries; and a little more acidity. The downy undersides help prevent heat damage to the vine by protecting transpiration and reflecting light.

The Tinta (SP.) and Noir (FR.) versions are often not seen as a varietal-labeled wine, being blended with other local varieties. The most notable blend combination is with Syrah (Shiraz) and Mourvèdre (Monastrell), more commonly known as the GSM blend, which you will find where the three grow together: France, the United States, Australia, and South Africa. You will find that all of the versions will thrive by having good placement in their local communes across France and Spain. Local AOC/AOP rules will govern

how it is grown in the vineyard and made into wine across much of southern France and Spain.

From a viticulture and winemaking point of view, work with the general premise that it can be prone to large crop levels. The larger crop levels can be fine depending on the mutation. If making rosé with the Tinta and Peluda mutants then higher crop levels may be acceptable, depending on the degree of color that is desired in the final wines. You will often see rosé versions with a lighter salmon/pink version of the wine. Consider a green harvest sometime around veraison if a deeper color is desired.

Due to fairly low polyphenolic concentration in Garnacha’s grape skins, all versions are reported to be susceptible to oxidation once they are in the winery. Protecting from excessive oxygen exposure and liberal use of sulfur dioxide will help push your wine towards a cleaner rendition. My

Garnacha can mature with very high sugar levels while maintaining moderate acidity levels, which vary depending on the cropping level.

general experiences with the Tinta and Blanca versions center on varietal dry red or white wines respectively.

Don’t feel the need to ferment the must hot or over-press the grapes in order to compensate for the lack of tannins. Fermenting these grapes lower and slower is generally the preferred approach.

When I was at UC-Davis I used to make up a GSM blend that the students had to try to match me on. With the wines that I was using it was very intriguing as to how little Syrah was needed to blend into the wine to give the color a big boost. The students were fooled almost every time.

Garnacha is not just limited to the dry red and white wines, it is also the basis for vin doux naturelle in southern France. The name literally translates to “wine sweet natural.” Any grape can be used for this, but locally Grenache is used for its versatility. Invented in the 13th century, the mutage process is a fortification of the wine. It involves adding a supplement of wine alcohol to the grape must in order to stop the fermentation and preserve some of the natural grape sugars.

The rules state that a neutral grape alcohol (95%) must be added. In reading the rules, it is added to the must at a minimum of 5% and maximum 10% by volume. The resulting total “alcohol richness,” a combination of the alcohol acquired and potential alcohol, can range from 15–21.5% by volume in most of the appellation d’origine protégée (AOP). There are initial Brix requirements for these wines as well; just over 25 °Brix is the minimum sugar level. I had to read the rules several times and I think I now understand them. But I believe I would most certainly make a mistake if I were to try crafting my own vin doux naturelle. At least I’ll admit it before the fact!

All versions of Garnacha pair well with a wide array of foods. As a varietal, it goes best with the lighter meats, chicken, lamb, pork, and some seafood dishes. Pairing up the Garnacha blends takes a little more thought. The more tannic GSM blends require red meat

to tone down the astringency; sometimes mild cheeses will do the trick as well. You don’t want anything that will overpower the fruit characters. So strong cheeses and spicy sauces are out unless there is a bit of residual sweetness to the wine, like in a vin doux naturelle.

Coming around full circle on this article, I have left my opinion in the “room next door” and pointed out the facts as presented from my references. The

column covering this variety from 2011 certainly presented some facts, but I was jaded by the versions of Garnacha I had experience with. I am a long-standing advocate of the right variety needs to be grown in the right place (OK – just a little opinion there) but returning to the facts, the fruit I was working with was not the right variety, and I was too naïve to understand that (fact . . . not opinion). There we have it . . . enjoy the wine and mea culpa.

ENTER YOUR BEST HOMEMADE WINES IN THE WORLD’S LARGEST COMPETITION FOR HOBBY WINEMAKERS!

DON’T WAIT — SEND YOUR ENTRIES NOW! ENTRY DEADLINE: MARCH 17, 2023

Enter your wines and compete for gold, silver and bronze medals in 50 categories awarded by a panel of experienced wine judges. You can gain international recognition for your winemaking skills and get valuable feedback on your wines from the competition’s judging panel.

Entry Deadline: March 17, 2023 5515 Main Street • Manchester Center, VT 05255 ph: (802) 362-3981 ext. 106 • fax: (802) 362-2377

email: competition@winemakermag.com

You can also enter online at: www.winemakercompetition.com

WineMaker of the Year

will be awarded thanks to our award sponsors:

Best of Show Red

Retailer of the Year

Best of Show White

U-Vint of the Year

Best of Show Dessert

Club of the Year

LALLEMAND BREWING

Best of Show Mead

Best of Show Country Fruit

Best of Show Sparkling

Best of Show Estate Grown

Best of Show Kit/Concentrate

Category Medals (gold, silver, and bronze) will be awarded thanks to our category sponsors:

18. Other White Vinifera Varietals

34. Red Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

35. Blush Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

36. Grape & Non-Grape Table Wine Blend

37. Apple or Pear Varietals or Blends

38. Hard Cider or Perry

39. Stone Fruit (Peach, Cherry, Blends, etc.)

GLCC Co.

40. Berry Fruit (Strawberry, Raspberry, Blends, etc.)

GLCC Co.

41. Other Fruits

GLCC Co.

42. Traditional Mead

43. Fruit Mead

Moonlight Meadery

44. Herb and Spice Mead

45. Flower or Vegetable

46. Port Style

47. Sherry Style

48. Other Fortified

33.

49. Sparkling Grape, Dry/Semi-Dry or Sweet

50. Sparkling Non-Grape

1. Entry deadline for wines to arrive is March 17, 2023

Wines are to be delivered to: Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Ph: (802) 362-3981

2. Send ONE (1) BOTTLE per entry. Still wines must be submitted in standard 750 ml wine bottles. Ice wines or late harvest wines can be submitted in 375 ml bottles. Meads and Hard Ciders can be submitted in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must be in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire or crown cap. All bottles must be free of wax, decorative labels and capsules. However, an identification label will be required on the bottle as detailed in rule #5.

3. Entry fee is $30 U.S. dollars (or $30 Canadian dollars) for each wine entered. Each individual person is allowed up to a total of 15 entries. You may enter in as many categories as you wish. Make checks payable to WineMaker. Only U.S. or Canadian funds will be accepted. On your check write the number of entries (no more than 15 total) and the name of the entrant if different from the name on the check. Entry fees are non-refundable.

4. All shipments should be packaged to withstand considerable handling and must be shipped freight pre-paid. Line the inside of the box with a plastic trash bag and use plenty of packaging material, such as bubble wrap, around the bottles. Bottles shipped in preformed styrofoam cartons have proven reliable in the past. Every reasonable effort will be made to contact entrants whose bottles have broken to make arrangements for sending replacement bottles. Please note it is illegal to ship alcoholic beverages via the U.S. Postal Service. FedEx Air and FedEx Ground will destroy all amateur wine shipments so do not use either of these services. Private shipping companies such as UPS with company policies against individuals shipping alcohol may refuse your shipment if they are informed your package contains alcoholic beverages. Entries mailed internationally are often required by customs to provide proper documentation. It is the entrant’s responsibility to follow all applicable laws and regulations. Packages with postage due or C.O.D. charges will be rejected.

5 Each bottle must be labeled with the following information: Your name, category number, wine ingredients, vintage.

Example: K. Jones, 9, 75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch, 2020. If you are using a wine kit for ingredients please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients. Example: K. Jones, 22, Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon, 2021. A copy of the entry form, listing each of your wines entered, must accompany entry and payment.

6. It is entirely up to you to decide which of the 50 categories you should enter. You should enter each wine in the category in which you feel it will perform best. Wines must contain a minimum of 75% of designated type if entered as a varietal. Varietals of less than 75% must be entered as blends. To make sure all entries are judged fairly, the WineMaker staff may re-classify an entry that is obviously in the wrong category or has over 75% percentage of a specific varietal but is entered as a blend.

7. Wine kits and concentrate-based wines will compete side-by-side with fresh fruit and juice-based wines in all listed categories.

8. The origin of many Native American grapes is unknown due to spontaneous cross-breeding. For the purposes of this competition, however, the Native American varietal category will include, but is not limited to, the following grape families: Aestivalis, Labrusca, Riparia and Rotundifolia (muscadine).

9. For sparkling wine categories, dry/semidry is defined as <3% residual sugar and sweet as >3% residual sugar.

10. Contest is open to any amateur home winemaker. Your wine must not have been made by a professional commercial winemaker or at any commercial winery. No employee of WineMaker magazine may enter. Persons under freelance contract with Battenkill Communications are eligible. No person employed by a manufacturer of wine kits may enter. Winemaking supply retail store owners and their employees are eligible. Judges may not judge a category they have entered. Applicable entry fees and limitations shall apply.

11. All wines will be judged according to their relative merits within the category. Gold, silver and bronze medals within each category will be awarded on point totals and will not be restricted to the top three wines only (for example, a number of wines may earn enough points to win gold). The Best of Show awards will be those wines clearly superior within those stated catego-

Entry deadline for wines to arrive in Vermont: March 17, 2023

Wines judged: April 21-23, 2023

Results first announced at the WineMaker Magazine Conference in Eugene, Oregon June 3, 2023

(Results posted June 4, 2023 on winemakermag.com)

ries. The Grand Champion award is given to the top overall wine in the entire competition.

12. The Winemaker of the Year award will be given to the individual whose top 5 scoring wine entries have the highest average judging score among all entrants.

13. The Club of the Year, Retailer of the Year and U-Vint of the Year awards will be based on the following point scale: Gold Medal (or any Best of Show medal): 3 points

Silver Medal: 2 points

Bronze Medal: 1 point

The amateur club that accumulates the most overall points from its members’ wine entries will win Club of the Year. The home winemaking retail store that accumulates the most overall points from its customers’ wine entries will win Retailer of the Year. The U-Vint or On-Premise winemaking facility that accumulates the most overall points from its customer’s wine entries will win U-Vint of the Year.

14. The Best of Show Estate Grown award will be given to the top overall scoring wine made with at least 75% fruit grown by the entrant. Both grape and country fruit wines are eligible.

15. All entrants will receive a copy of the judging notes for their wines. Medalists will be listed by category online.

16. All wine will become the property of WineMaker magazine and will not be released after the competition.

17. All decisions by competition organizers and judges are final.

Deadline: March 17, 2023

Entry Fee: $30 (U.S.) or $30 (Canadian) per wine entered

Number of entries _____ x $30 (US) or $30 (CD) = $________Total (limit of 15 entries per person)

q Enclosed is a check made out to “WineMaker” in the amount of $_________.

Name___________________________________________________________________________

Address_________________________________________________________________________

City________________________State/Prov______Zip/Postal Code____________________

Telephone_______________________________________________________________________

E-Mail____________________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Club:________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Retailer:_____________________________________________________________

U-Vint / On-Premise Store:________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage: Please list fruit varieties and percentages used in each wine. Example: “75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch.” If you are using a wine kit for ingredients, please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients.

Example: “Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Wine 1 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ____________________________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 2 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 3 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

winemakercompetition.com

Remember that each winemaker can enter up to 15 wines. If entering more than eight wines, please photocopy this entry form. Entry shipment includes ONE BOTTLE of wine per entry. 750 ml bottle required for still wines. Ice or late harvest wines can ship in 375 ml bottles. Still meads can ship in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must ship in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire or crown cap.

Send entry form and wine to:

Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Ph: 802-362-3981 • Fax: 802-362-2377

E-mail: competition@winemakermag.com

If entered online at winemakercompetition. com, please print a copy of your entry form and send it along with your wine.

Wine 5 Entered:

Category Number_________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 6 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 7 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 4 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Enter online at: winemakercompetition.com

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 8 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

“More attention to ullage management and SO2 levels would help.”

“Pay closer attention to overall fermentation health.”

“Prioritize cellar hygiene.”

by Phil Plummer

by Phil Plummer

f you entered wines in the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition and your scoresheets were marked with one or more of the abbreviated suggestions on the facing page, there’s a strong chance your wines were evaluated by Judge 21, yours truly. For a few days in April, I had the pleasure of tasting amateur wines from around the world with a diverse team of thoughtful and talented wine judges. The creativity and care expressed in the wines were obvious, but as the flights continued to pile up, I realized that I was giving a lot of the same commentary from wineto-wine. Often, it seemed like a few common, preventable flaws were stifling wines that would have otherwise been delightful. The limited time and space allotted to make suggestions on the scoresheets felt insufficient, and I even considered leaving my contact information on a few because I thought a broader conversation might be helpful. This feeling nagged at me for a few weeks before I realized I had the perfect platform I’d hoped for all along: This magazine!

I’m not trying to push a perfectionist winemaking ethic here; far from it, in fact. I’m as aware as anyone that a flaw can present as a beauty mark in the right context. Furthermore, it’s important to keep in mind that many of the classes of chemical compounds in wines have both pleasant and unpleasant examples — courting the pleasant ones sometimes creates the perfect conditions to generate or hang on to the unpleasant ones. A hint of volatile acidity might amplify the red fruit aromas of a rich, bold Sangiovese. A little hydrogen sulfide might be tolerable in Sauvignon Blanc if it’s reflective of the reductive winemaking needed to preserve that variety’s signature thiol aromatics. There are real-world instances of technical flaws improving or at least not ruining a wine, but those aren’t what I intend to talk about.

When I pitched this article, I realized a discussion of how wine competitions work might help to explain why flaws factor so heavily in scoring. After all, many of the world’s great commercial wines are far from flawless; occasionally, as mentioned, a flaw here or there might even make a wine more appealing. So why doesn’t that hold true in the context of a wine competition? It’s simple, really: Wine competitions are all about first impressions. Think of it like dating — in a perfect world, you’d get to spend

some quality time with a wine, learning about what made it the way it is, where it’s been, where it’d like to be, not leaving a single stone unturned or question unasked. Wine competitions, though, they’re a lot like speed dating. The sheer volume of wines to be tasted over a short period of time necessitates that judges develop a streamlined heuristic to speed up the process — often this places priority on seeking out a wine’s red flags: Flaws. Whether a red flag is a deal breaker (crossing the boundary between flaw and fault) or not is another question; sometimes a flaw is present for stylistic reasons, sometimes it’s just not offensive enough to spur fixation. Regardless, the mere presence of a detectable flaw is almost always reflected in a wine’s overall score — learning how to prevent and address some of the most common ones is a surefire way to improve your medal count.

TESTING . . . 1, 2, 3