GET READY FOR HARVEST:

PRE-FERMENT TREATMENTS

TAMING WILD FERMENTS

SULFITE MANAGEMENT

UNDERSTANDING MLF

Cru International invites you discover two highly acclaimed international wine styles!

Bourbon Barrel Style brings to life full-bodied whiskey flavours all the way from Kentucky and French Gamay Style highlights the unique tastes of grapes inspired by one of the finest grape-growing regions of France.

Working with Musto Wine Grape gives you access to a wine grape and wine juice network unlike any other. We have grower contracts that date back to the 60's plus on staff winemakers to help ensure you have a successful fermentation. MWG is your premier source for all your winemaking needs

MustoWineGrapeCo.

sales@juicegrape.com

877-812-1137

www.juicegrape.com

www.WinemakingInstructions.com

Wild fermentations can often bring a level of complexity to a wine not always found using commercial Saccharomyces strains. But the tradeoff for that complexity is higher risk. What if you could introduce the good microbes of a wild fermentation to your wine without the risk? There are techniques, along with new isolated non-Saccharomyces yeasts, that can do just that.

by Phil PlummerThe use of sulfites in wine — how much, or even if used at all — remains a contentious subject. WineMaker’s Technical Editor shares his own simple yet practical approach to sulfite management that works every time.

by Bob Peak

by Bob Peak

Most red and some white wines are put through a secondary malolactic fermentation (MLF). The process converts malic acid to lactic acid, which smooths out harsh flavors while adding a richness on the palate, as well as contributing to the stability and aging potential of the wine. Learn when a wine should go through MLF, how to do it, and ways to test for it.

by Maureen MacdonaldWhether you are considering a career in winemaking or just want to further your knowledge, a formal education in enology and viticulture has its benefits. Here is what you should know before you enroll.

by Kristen Kuchar

by Kristen Kuchar

• Destemmer Crushers

• Speidel Bladder Presses

• Pumps For Must & Wine

• Speidel Stainless Tanks

• Bottle Fillers

• Oak Barrels

CellarScience™ adds complexity and flavor to your wine with our carefully curated set of wine yeasts. Designed to work directly with CellarScience™ yeast nutrients FermStart™, Fermfed™, and Fermfed™ DAP Free. As with all CellarScience™ products, the value is the best in the industry.

8 MAIL

A reader in Northern California shares a technique he believes has been beneficial in mitigating the impact smoke taint has had on his homemade wines over the last 5+ years when wildfires have destroyed many other wines from the area.

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

Wine bottle capsules can take many forms. Reader Nicholas Cozzarelli takes us on a tour of the various kinds and how they are applied. Also, learn about the grape crushing process and options, as well as the latest winemaking news and upcoming events.

14 WINE WIZARD

There has been growing interest in reduced alcohol wines in recent years as the health benefits and caloric reduction is lauded by the medical world. The Wine Wizard offers tips to a home winemaker looking to produce their own lower-alcohol wine. Another winemaker is trying to find ways to reduce their water usage in the winery.

18 VARIETAL FOCUS

A new flock of hybrid grape varieties in the market is turning heads, not only for their disease and cold tolerance in the vineyard, but also in the winery for the qualities that they can carry to the bottle. Meet Cabernet Doré.

48 TECHNIQUES

Finding high-quality grapes, even in wine country, can be a challenge for new winemakers. Get some advice for sourcing fresh grapes, no matter where you live, as well as how to handle the grapes to get them home safely.

51 ADVANCED WINEMAKING

Most red winemakers will begin alcoholic fermentation shortly after the grape clusters are pressed. But there are some alternative techniques that can be utilized pre-fermentation to try to bring distinctive character to the wines they produce.

56 DRY FINISH

When an amateur winemaker notices that his 6-year-old daughter is taking a keen interest in his hobby, he happily opens the door to his winery. Join in on a family winemaking adventure.

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Dwayne Bershaw, Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe, Wes Hagen, Maureen Macdonald, Bob Peak, Phil Plummer, Dominick Profaci, Clark Smith

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER

Charles A. Parker

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Phil Plummer Montezuma Winery

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

I really like aromatic white wines and would like to produce some more varietals that are less common here in the States. I’ve tried (and failed) to get a couple hundred pounds of Albariño in the past. Although, I’d be equally happy if I could line up some Verdejo or Vernaccia.

I’d love to make some wine from Gamay Noir. I really enjoy Beaujolais wines, so I’ve always had an eye out for this grape being made in other regions. Currently there are a few Finger Lakes, New York, wine producers who have planted and are making wines with this variety, but it’s relatively uncommon. I’ve tried several of these local wines and I’m impressed with the quality. If we can economically grow this variety in NY I think it may catch on with consumers.

QPUBLISHER

Brad Ring

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER

SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

Yeast are fairly simple, single-celled organisms. But their diversity, functionality, and ability to adapt is why humans, and especially winemakers love these fungi so much. Bob Peak takes us through several strains that winemakers should know are available. https:// winemakermag.com/technique/ special-purpose-wine-yeasts

Whether it is just the basics (Brix, pH, etc.) or more advanced (free SO2, yeast assimilable nitrogen, etc.) all home winemakers should perform some tests to monitor their wines. https://winemakermag.com/ article/at-home-in-the-wine-lab

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981 Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $29.99

Cover Photo:

Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

There are plenty of grapes that seem to do really well in our neighborhood that aren’t planted widely enough that we’ve ever had a chance to work with them; if I had to pick just one, it’d probably be Gamay.

Crunchy, chillable dry reds are some of my favorites to drink and cool-climate Gamay produced in a Beaujolais-style sounds like a layup to me. There are a few plantings in the Finger Lakes AVA, but there isn’t enough to go around. Hopefully the variety can build enough of a following that more will get planted!

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2023 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 26, Number 4: August-September 2023.

Volatile thiols are delicate but powerful aromatic compounds released during fermentation. Through careful techniques and yeast selection, these thiols can be both preserved and enhanced to create an aromatic wine that pleases the senses. https://winemakermag.com/ article/the-role-of-varietal-thiols-inwhite-wines

As harvest nears it is time to make a plan of action for how you will proceed with each batch of wine you plan to make this fall. With red wines there are many options. We take a closer look at cold soaking, extended macerations, and carbonic macerations, which are all worth consideration for home winemakers. https://winemakermag.com/ article/maceration-considerations

I subscribe to the print copy of WineMaker magazine and always read the headlines from the online version before delving into the full article. I read the Wine Wizard’s response to a question about making wine from grapes affected by smoke taint in the April-May 2023 issue and would like to offer a bit of my experience.

While I agree that the last several years here in Northern California have been a challenge with “minimizing” the taste of smoke in the finished wine, I have yet to read that thoroughly washing the fruit bunches with copious amounts of cold water can minimize the problem. It has been my experience that a thorough washing removes most of the “ash,” which is the real culprit here. There is a concentrated smoky element to every flake of ash that floats from a wildfire and envelops a vineyard. If harvested grapes are destemmed and crushed without a thorough washing, the “taint” effect cannot be minimized nor eliminated. I believe washing the grapes helps, perhaps not 100%, but certainly enough to prevent an undrinkable wine.

I live in the eastern foothills of Santa Clara Valley (Mt. Hamilton area). I have about 100+ vines in my vineyard and have suffered from the wildfire smoke like everyone else. Additionally, I source fruit from two friends who have vineyards in the Santa Lucia Highlands and virtually all of us are affected regardless of where we live in Northern California.

I am the first to agree with those who say that washing the fruit with cold, clean water is both time consuming and quite an extra expense. However, I weigh that once a year investment against the loss of everything we work for all year long! Wash the fruit thoroughly with a copious amount of cold, fresh water and allow a bit of time for the fruit to drain. Then proceed with crush and fermentation.

Jim D’Amico • Mt. Hamilton, California

If you’ve had success mitigating the negative impact of smoke taint caused by the wildfires in Northern California and elsewhere with this practice, then great job and others should keep it in mind as well. If there is ash on the grapes coming in, then giving the grapes a rinse certainly makes sense! We’ll continue following the research that is being done regarding smoke taint — many studies are currently being conducted by the Australian Wine Research Institute, UC-Davis, and other institutions — and we’ll keep relaying this information so amateur winemakers are set up for success.

Phil Plummer has been a student of wine since 2004 when he began his formal education in the subject at Rochester Institute of Technology. For the past 11 years, Phil has worked for the Martin Family Wineries (Montezuma, Idol Ridge, and Fossenvue) in New York’s Finger Lakes Region, serving as Head Winemaker since 2013. In his time as Head Winemaker, he has developed a diverse portfolio of unique wines made from grapes, fruit, and honey. Phil’s passion for wine and winemaking is boundless, as evidenced by his constant experimentation with new techniques, materials, and mindsets.

Yeast manufacturers have released a number of isolated non-Saccharomyces strains in recent years to offer winemakers the complexity of wild fermentations without the risk. Beginning on page 24, Phil explores these options for the home winemaker.

Maureen Macdonald is a University of Vermont graduate with two decades professional experience in the beverage and wine industry. She has experience in both viticulture and enology as a Field Manager and Head Winemaker for commercial vineyards. After years of working as a consultant to many vineyards, she now is the Head Winemaker for Hawk Ridge Winery in Watertown, Connecticut, where she makes 30 different wines. When she isn’t hard at work in the lab or winery, she is often judging commercial and amateur competitions or making hard cider and beer at home.

Starting on page 36, Maureen explores the process of malolactic fermentation — from what it does and the reasons you may want to employ this secondary fermentation in your wines, to when, why, how to test for completion, and more.

Kristen Kuchar is a Colorado-based freelance writer and editor who has the wonderful opportunity to cover her greatest loves in life – beer, wine, travel, and other craft beverages. She is a Cicerone Certified beer server, completed WSET in Wine Level One, and is a certified American Wine Expert. Her byline has appeared in Brew Your Own, VinePair, The Beer Connoisseur, Beer Advocate, Zymurgy, DRAFT, All About Beer, and dozens of other publications. When she’s not writing about her favorite things, you can find her exploring new breweries, hiking in the Rocky Mountains with her sweet cattle dog, and traveling every chance she can get with her husband.

In her first article for WineMaker, starting on page 42, Kristen shares the benefits of a formal education in enology or viticulture through the eyes of those associated with various academic programs and others who have gone through them.

In 2009 the European Union announced that the debate should be over, Presecco would be the designated region of origin where the namesake wines are produced (in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy) and the grape variety utilized to produce its famed Prosecco sparkling wines would now be called Glera. So just like a wine cannot be named a Champagne wine if it made outside of the region, the name Prosecco, according to this new rule, should only be applied to wines produced in that specific region of Italy. Why does this matter? Well, because there are a number of wineries, most notably in Australia, that call their wine Prosecco because it was made from the grape variety that, according to the new designation, can no longer use the title Prosecco. Since there are no grape varieties named Champagne, or Bordeaux, or Burgundy, this was never an issue with those regional designations.

But after five years of research, Monash University’s Professor of Law Mark Davison came to the contradictory conclusion that it should be the grape named Prosecco, not Glera, citing reference to the grape variety as far back as the 1700s. His research found no similar reference to the region being known as Prosecco. Whichever side prevails, this could have major implications for not only the Italians but also the $200 million Australian sparkling wine segment that would be forced to list the grape type as Glera. The use of geographic indicators has become a hot button topic for the European Union and is playing out in economic trade negotiations. Stay tuned: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-21/proseccoeuropean-union-geographic-indication-italy-champagne-/102250984

Sonoma County Harvest Fair Amateur Wine Competition deadline to register entries is Friday, August 18 at 11:59 p.m. (PST). Registration for entries are accepted starting July 1. Wines can be received, either via mail or dropped off in-person, at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds and are only accepted the week of August 21–25. Judging takes place on September 9 with the public tasting on October 14. For more visit http://harvestfair. org/amateur-wine/

Save The Date for our 15th annual WineMaker Conference, which will be held in beautiful Charlottesville, Virginia. Regarded as the birthplace of American wine thanks to the first commercial vineyard planted in 1774 by Thomas Jefferson, the Monticello AVA is keeping that legacy alive with 40 wineries. Don’t miss dozens of winemaking and grape growing workshops, seminars, and special events all geared for home winemakers. https://winemakerconference.com

Virtually all professional winemakers finish the tops of their wine bottles with a capsule — whether it’s composed of PVC, tin, polylaminate, aluminum, or wax. The capsule is thought to help protect the cork from mycobacteria. I personally love the look of capsules as it makes the presentation of a homemade bottle of wine more appealing aesthetically. But it is important to understand the differences of what they are and how to apply them.

PVC, or polyvinyl chloride, is utilized by the home winemaker and comes in an array of colors. In our winemaking setup, we actually have a cabinet that houses all different colors of PVC shrink capsules. This becomes our palette when we apply our label and pick an appropriate colored capsule to finish the work. PVC is the least expensive for both commercial and home winemakers, but it is one of the worst plastics from an environmental health perspective. It can pose major health hazards in the manufacturing process, and disposal (look no further than the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio). PVC capsules can be applied by three different methods: Blow dryer, a pot of boiling water, or using a heat tunnel (my preferred method).

Tin capsules bring a very elegant and expensive look to your wine bottle. Tin capsules require a specific piece of equipment called a spinner, which is common in the commercial winemaking world. We have a single spinner for the home winemaker. One must be careful when handling a tin capsule as there is a sharp edge to them.

Polylaminate capsules are comprised of a three-layer aluminum-polyethylene-aluminum seamed skirt and aluminum top disc. “Polylams” (for short) are not approved by the FDA for direct contact with food but are a secondary, decorative closure, and not intended to contact wine or other beverages. Polylams have many of the characteristics of tin with a reduced price and are the most requested closure and are suitable for any type of wine, including both premium and homemade wines. If the winemaker wants to upscale his bottle of wine to appear nicer, polylam is an excellent choice and applied with a spinner.

The aluminum capsule offers the form and function of tin, but at a more affordable price, similar to the price of polylam capsules. Aluminum capsules are more sustainable because they are more environmentally friendly and can be recycled. Like tin and polylam cap-

sules, an aluminum capsule is applied with a spinner.

Back when the only choice in high-end wine packaging was amphorae, wax was the seal of choice, often embossed with a signet. The wax is comprised of rosin, paraffin wax, or microcrystalline wax, and many different colors are available. Some wineries still use wax, but the cost is expensive and is very time consuming for the application. Hand-dipping wine bottle sealing wax accomplishes a distinct look on the bottle, provides a positive seal, and is an environmentally conscious product as opposed to using the traditional products such as foil or metal capsules. The winemaker wax is supplied either in one-pound bars or bags of wax chips. I prefer the chips, which melt faster. The wax capsule helps you achieve a tough, moisture-resistant coating that preserves freshness, flavor, and fragrance in your wines. Despite the additional time for the home winemaker, the wax capsule look is distinct.

or fresh grape winemakers, the task of crushing the grapes is generally going to be the first task on the list after the grapes have been received and inspected for damage. Most winemakers would highly recommend that specialty equipment is used, but that shouldn’t stop those on a budget because there are workarounds. Before we dive in here about crushing grapes, it’s important to note that while it is generally recommended that winemakers crush their grapes after they are received, it is not always a necessary task.

The benefit of crushing is primarily to allow access to the juice inside the grape skins. For reds you want this exposure so that the yeast can access the juice and for the skins to macerate during fermentation. For whites and rosé wines, crushing can allow for easier pressing to extract the grape juice into a fermenter.

But there are a couple instances where grapes can be left uncrushed such as in whole cluster winemaking and when a winemaker is looking to perform a carbonic maceration. In the case of whole cluster winemaking for white and rosé wines, it implies the grape clusters go directly to the press with their stems and skins still intact. This means the juice will have almost zero time to extract compounds from the skins before being run off. The goal of this technique is to produce a delicate wine with very low astringency. Unfortunately for home winemakers, the standard ratcheting basket press does not have the necessary pressure to press whole cluster grapes in this manner. This method can be done at home with a bladder press.

Carbonic maceration is a specialized way to produce very fruity, early drinking red wines, such as seen in Beaujolais nouveau style of wines. In this situation whole clusters of

red grapes are purged of oxygen and enzymatic fermentation is allowed to commence within the berries. Eventually the grape skins burst and then the wine can be pressed. This is a very niche technique and should not be employed unless a deep dive has been done into the process and what it produces in the finished wine.

We’re going to look at three of the most popular ways that home winemakers can get their grapes crushed: Hand crushing, using a mechanical crush, and using a crusher/destemmer. The initial equipment cost goes up as we move along that list with the crusher/destemmer being the most convenient but also garnering the highest price tag, especially models that feature an electric motor to turn grinding wheels as opposed to hand crank-driven models.

Hand crushing is the cheapest to set up but requires plenty of muscle and can get pretty messy. It can be performed on a large stainless steel screen, a screen that you feel comfortable leaning some weight into as you’ll be smushing the grapes through the screen and into your fermentation bucket in the case of reds or a settling bucket in the case of whites and rosés. (Technical Editor Bob Peak also mentioned that milk crates are another tool that can be used to crush the grapes.) Stems preferably will be sorted out with this technique and this method is perfect for small-scale, 5 gal. (19 L) and under, batches.

If hand crushing (or even the classic foot stomping) doesn’t appeal to you, then it’s time to consider your options with either a mechanical crusher model or a crusher/destemmer.

A mechanical crusher can be built at home by those with some engineering chops. But most winemakers opt to purchase (or rent) one through a wine supplier. Models that offer destemming

capabilities are more expensive, so why might you invest? Stems can provide a lot of small polyphenolic compounds (providing astringency and bitterness to wine) if left in contact with the juice, such as in red winemaking.

For white and rosé wines, it’s perfectly fine to leave the stem with the grapes and juice since it will see the press quickly and those polyphenolic compounds won’t have time to get extracted. But for red wines, just how ripe the stems are does have an impact on the characteristics it will impart on the wine. Green stems will provide a more herbaceous and vegetal character while brown, lignified stems provide more spicy, black tea character. Being able to control when to include a little or a lot can be useful.

If doing small-batch winemaking (5 to 10 gal./20 to 40 L), destemming can be done by hand. But for those that are looking to grow their hobby and do larger batch sizes, especially with red winemaking, you should consider spending the money on the destemmer option. Stems can always be added back after being removed.

While it would be nice if more commercially available hobby crushers offered adjustable gap spacing, there are ways to play around with your crush even with fixed rollers. Just as it was earlier mentioned that winemakers don’t have to crush, there are ways to play around with the percentage of grapes you crush.

You may want to try crushing 80% of the grapes for a Burgundian-style wine and leave the remaining 20% intact to undergo carbonic maceration to enhance the fruitiness. For white wines, maybe just crushing 50% of the grapes to minimize skin exposure for a Pinot Gris. There are no set rules, just options.

QI’VE SEEN A FEW LOWER ALCOHOL WINES COME ONTO THE MARKET LATELY AND AS MY WIFE AND I GET OLDER WE AREN’T SUCH BIG FANS OF BOOZY WINES, ESPECIALLY THOSE OVER 15%. WE’RE TRYING TO CUT BACK A BIT ON ALCOHOL IN OUR LIVES IN GENERAL, FOR CALORIES’ SAKE, AND ARE LOOKING TO KEEP ENJOYING OUR WINE. ALSO, IT SEEMS THAT LATELY WE’VE BEEN EXPERIENCING MORE HEATWAVES IN OUR GROWING AREA, MAKING IT HARDER AND HARDER TO KEEP OUR ANNUAL VINTAGE OF CHARDONNAY, SAUVIGNON BLANC, AND CABERNET ( WE’RE IN CALIFORNIA’S MENDOCINO COUNTY ) UNDER 14% ALCOHOL WHERE WE’D LIKE IT. DO YOU HAVE ANY TIPS FOR HOME WINEMAKERS WHO WANT TO TRY TO MAKE BALANCED, TASTY WINES WHILE STILL KEEPING ALCOHOL MODERATE? I KNOW IT CAN’T BE JUST AS SIMPLE AS PICKING THE GRAPES A LITTLE GREENER.

AFunny you mention this topic because I’m currently working on a lower-alcohol project at work (at Plata Wine Partners, I often develop custom projects for clients, and this is one). The brief for me is to come up with a delicious, balanced Pinot Noir and rosé that clock in around 9% alcohol. There is some evidence that the typical U.S. consumer is increasingly interested in buying and enjoying wines with more moderate levels of alcohol.

Like you, they seem to be interested in a) avoiding getting a little too tipsy and/or b) achieving health and wellness goals of reducing alcohol consumption like curtailing inflammation or lowering calorie consumption. Now, of course, for my project I’m going to have to use reverse osmosis machinery to physically remove some of the alcohol, something that your usual home

winemaker won’t be dealing with. The process can cost thousands of dollars to employ and only larger-scale bottling runs can justify it. That being said there are many things that winemakers can employ to try to get balanced, delicious wines with naturally lower alcohol levels.

Whatever a winemaker’s goal, we all have to think about how alcohol plays (or doesn’t play) well with the other components in any given wine. Alcohol never stands alone and, contrary to what some wine advocacy groups would have us believe, isn’t the only component important for “balance.” Total acidity, pH, aromatic complexity, tannin, sugar, and carbon dioxide levels, especially, are all important pieces of the overall picture of a wine.

Bruce W. Zoecklein at Virginia Tech sketches out the below schematic, which explains the interactions:

Total acidity, pH, aromatic complexity, tannin, sugar, and carbon dioxide levels, especially, are all important pieces of the overall picture of a wine.Photo by Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

Alcohol brings a sense of body to wine and can also increase the perception of tannin. Sugar can mask both acidity and tannin and also can give the impression of body and a “full” mouthfeel. It often is present in lower-alcohol wine because of these effects. In order to not have a product be too sweet, higher acid is often required to balance the sugar if present. Acid and phenolics reinforce and amplify each other so too much of one can bring out a negative in another. The most important thing to remember is that if alcohol is going to be lower, other “sweet” components have to be higher or something on the other side of the equation (acid + phenolics) has to be lower.

Carbon dioxide bubbles will contribute body, which is one of the reasons many sparkling wines can be so successful at lower alcohol levels. Floral, distinctive, or especially rich aromatic varietals as well, will help the “nose” take the place of some of the complexity that ripeness and alcohol might have contributed. For this reason, Chardonnay is hard to do on a low-alcohol level whereas Riesling can really shine.

Like I mention above, most winemakers aiming for lower-alcohol wines aren’t simply removing alcohol post-fermentation but are taking a systemic, holistic approach. Below are some techniques to employ if you are seeking to reduce the sugar levels in your grapes or the eventual alcohol levels in your wines.

• Plan to make varietals that don’t rely on the heft of booze for style and that bring other charms to the party. Floral and aromatic varietals like Riesling and Malvasia Bianca, for example, are lovely at lower alcohol levels. In your case, your Sauvignon Blanc may be a really great play. Instead of trying to make your Cabernet super “lite” maybe buy some Pinot Noir from a neighbor?

• Choose to make wine styles that naturally lend themselves to lower alcohol like low tannin, sparkling (or slightly spritzy . . . think vinho verde) products.

• Choose naturally lower-acid sites, especially those with hot nights (over 70 °F/21 °C) and lower diurnal fluctuation, which will burn off residual acid earlier in the season. Especially in whites, this will allow for full-flavored picking at lower Brix. I would think your Mendocino Sauvignon Blanc would be ideal for this.

• Hold off on irrigation as much as possible post-veraison. This pushes the vine into senescence and developing tannins earlier in the season.

• Don’t thin fruit too much. A higher tonnage per acre (contrary to popular belief) will assist to ripen fruit faster for a given leaf load.

• Remove laterals.

• Make sure you don’t have too much canopy, especially for reds. Dappled, open sunlight into the fruit zone is critical as it decreases malic acid during ripening. Also, you do not want bell pepper pyrazines in your Cabernet, so be especially careful here.

• Leaf pluck in the fruit zone, as long as a heat wave doesn’t

threaten sunburn.

•Try box-pruning or “California sprawl” to get dappled sunlight into all of the vine.

• Get out in the vineyard and taste constantly as harvest approaches. Don’t be afraid to pick some “early lots” if you can in order to get some lower alcohol blenders. You may be surprised at the quality, especially if you’ve followed some of the above suggestions.

• Add water generously to combat any berry dehydration. Water added early always integrates better.

• Adding untoasted oak dust/shavings at the crusher can help combat green flavors in red grapes.

• Warmer fermentations (more suitable for reds than whites) can help “blow off” a certain amount of alcohol, perhaps 0.25–1%.

• Open top fermenters, like those often employed in producing Pinot Noir, can also contribute to ethanol “blow off” and reduce alcohol slightly by another 0.25–1%.

• For white wines that will not be 100% malic acid complete, choose a malic acid reducing yeast like Lalvin C. It gives a 30% reduction in malic acid during primary fermentation and “rounder” flavor without any undesired malolactic fermentation byproducts that may not be style appropriate.

• Try arresting fermentation, especially for whites that have higher acid, to leave a little residual sugar. This will result in a lower final alcohol and will balance out the higher acid/lower alcohol and lend some body to the finished wine that alcohol would’ve contributed.

• Try blending lots from early-pick, warmer-night sites (see above, less acid) with those that come from higher-flavored, more “traditional” sites.

• Surprisingly, some of the newer tannin preparations from companies like Laffort, AEB, and Enartis can really smooth out rough phenolics and make “green” disappear in young and finished wines. I hear good things about the “Rouge” tannin from AEB and the “Dark Chocolate” tannin from Enartis. By removing green or rough-feeling tannins, the reduction of body-enhancing alcohol won’t be missed quite so much.

• If you are storing sweet wine, chill and/or filter in order to keep tabs on possible re-fermentation. Certainly sterile-filter the wine via crossflow or 0.45 micron nominal pad or cartridge if this is the case.

• I knowyou mentioned health as a goal, but don’t be afraid of adding 1–2 g/L residual sugar to achieve mouthfeel and flavor balance at bottling. I like to buy a little grape juice concentrate and meter it in maybe around 1–3 mL/L, just to give some roundness and add to the finish. Lower alcohol wines often need to be balanced in this way (sterile filter afterwards) and it can really help.

WE LIVE IN A PRETTY DRY AREA OF EASTERN WASHINGTON STATE. I’VE GOT A NICE LITTLE WINERY SETUP AND MAKE ABOUT 5–7 BARRELS OF MIXED REDS A YEAR, DEPENDING ON HOW AMBITIOUS WE FEEL. ONE THING I’VE NOTICED IS OUR WATER BILL HAS REALLY GONE UP A LOT TO A POINT WHERE IT’S A SIGNIFICANT MONETARY INVESTMENT IN THE PROCESS AND I HAVE TO FACTOR IT INTO OUR OVERALL WINEMAKING BUDGET. I KNOW WE’RE IN A DROUGHT- PRONE AREA AND IT MIGHT JUST GET WORSE AS THE YEARS GO ON. WHAT TIPS DO YOU HAVE FOR HOW WINEMAKERS CAN SAVE WATER DURING THE ENTIRE PROCESS FROM START TO FINISH?

AIt generally takes about 6 gal. (23 L) of water to make one gallon (3.8 L) of wine though estimates vary from as little as 2 gallons (7.6 L) all the way up to 20 gallons (76 L). Many folks have no idea where they fall on this spectrum and performing some kind of a water audit, even if it’s just to measure how much water you use to clean a typical small tank or barrel, will help establish a baseline.

Measuring your water consumption can start with installing flow meters to measure usage at key points like on the crush pad, at filtration, and at barrel washing areas. By filling up that stainless tub or drum you’ll get an idea how much wash-water gets used when you do any given task. Do the math to figure out how many gallons or liters of water per length of hose it takes to fill that volume. Use your current usage to create a realistic target for reduction.

• Pick “balanced” grapes, not overripe raisins, so you don’t have to add additional hydration water. Similarly, every time you avoid an addition (acid adjustment, etc.), you avoid having to clean and sanitize the tools.

• Cover your crush and reception area to minimize the “baking on” of waste material. The shade will make juice and grape skins easier to remove from equipment and will reduce the amount of water needed for cleaning.

• Pre-clean with brushes, brooms, and elbow grease before resorting to water for soaking and rinsing.

• Move from an old-fashioned three-step cleaning (caustic cycle, acid-neutralization cycle, and then water rinse) to a twostep process (K-OH followed by per-acetic acid or “quats” followed by a water rinse). If you wait 30 minutes after the per-acetic acid cycle, you don’t need to rinse with water.

• Invest in a pressure washer. Pressure washers clean floors and equipment well while only using between 2–4 gallons (8–14 L) per minute. Bonus — they are fun to use! One of my favorite winery jobs is pressure washing because you can always see what you’ve accomplished.

• Use water hoses with automatic shut-off valves and timers where appropriate.

• Minimizing the length and diameter of hoses as appropriate will use less water in sanitation.

• Be efficient with tank and barrel movements. The more you rack or move wine from one vessel to the next, the more often you have to clean and sanitize gear . . . and the more

water you will use.

• If you employ small variable “floating top” tanks for wine storage, you have to move wine less-often for breakdowns.

• Use “dirty” wash water as secondary wash water for other vessels (water recycling). Empty dirty water out into a sump and re-use for other tasks. Use relatively clean rinse water from your last phase of cleaning as the dirty first-step water for barrel cleaning.

• Clean carboys, kegs, and tanks in batches. Use the rinse water from one as the cleaning water for the next.

• Don’t chase wine with water in hoses if you can — flush/ push with gas and a pig (winemaker slang for a foam ball that you push through the line).

• About a third of all of the water a winery consumes can be in barrel washing! Be water-wise in this step.

• Coordinate barrel emptying and filling work to reduce the amount of time that barrels are empty. Freshly-emptied barrels don’t have to be swelled up with water again.

• Soak heads separately by flipping end-to-end.

• Use rinse water from one barrel to do initial cleaning of next (though do dump your cleaning water if you’ve got an infected barrel).

• Filters take water to clean and set up. If your red wine has a pH under 3.75, its free SO2 was maintained, doesn’t have any volatile acidity climbing, and you’re going to bottle it dry . . . do you really need to filter it before bottling?

• Consider using a liquid cellulose gum, like Laffort’s Celstab®, for cold stability instead of the traditional chilling and seeding with potassium bitartrate crystals.

• Settling well before hand, perhaps using isinglass, may enable you to filter with one pass rather than twice.

• Install aerators in all sinks so less water is used when sink taps are turned on.

• Foot-pedal operated “on/off” taps (like those often seen in hospitals) use less water when washing up at sinks.

• Under-sink or on-demand tankless water heaters get water up to temperature quickly, without having to travel a long distance from a traditional water heater tank. Luckily, depending on where you live, there may be significant government rebates or tax credits associated with switching over to these kinds of water heaters.

WITH WINEMAKER WINE & SAFARI ADVENTURE

March

Join WineMaker Magazine in South Africa next March 18 - 26, 2024 to combine wine with a safari adventure in one epic vacation! We’ll tour the most famous wine regions of South Africa including Stellenbosch, Franschoek, Paarl, and the Cape. We’ll visit both small and large wineries meeting their winemakers and tasting the local Pinotage and many other great wines during the excitement of their Southern Hemisphere grape harvest season. Then we’ll head to Kruger National Park to seek out lions, leopards, elephants, rhinos, and cheetahs from an open Land Rover with a ranger and spotter on a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime safari.

ONLY

Genetics is what really intrigued me about this issue’s variety. Ever since Watson and Crick discovered the double helix of DNA and unraveled its codes, scientists of many disciplines have sought out to map genomes. In the plant world, breeders have sought to genetically select for the biggest, the best, the most drought-tolerant, the most cold-tolerant, and the most disease-tolerant hybrids using the best characteristics of the parent varieties.

I was fortunate to be involved with some of the most advanced breeding programs for grapes in my former career. While I wasn’t the one doing the breeding, I was the one making the wine from the fruits of their efforts. These wines were subsequently judged by various panels to deem if the quality of the wine produced from the fruit was worth that hybrid moving to the next round.

I became involved in the grape breeding process five to six years after a new variety started as a first seedling. So there was a lot of pressure to make the best varietal wine from each specific hybrid. When I first started with the breeding team, my job was explained and I was told, “just make the best wine possible and your first fruit (about 50 lbs./23 kg or so) will be here next Tuesday.”

My first experimental variety was a cross of two white grapes . . . and this happened to be the first load of fruit of the season, so my excitement to perform my new winemaking role ran sky high. I prepared the cellar for a white grape crush and press. When the fruit arrived, I questioned its color — why was it red?! How did this happen? Was it an anomaly? No, it was simply

genetics. Today’s variety, Cabernet Doré, is a story about genetics and wine, of course.

Cabernet Doré (pronounced Dor-ay) is a white grape, opposite of the aforementioned example. How this occurs is that almost all grape varieties are inbred extensively and carry recessive genes from many different forbearers. The parents are two well-known varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon and Norton (listed as Cynthiana in some databases). Both parents have white grapes in their lineage, that being Sauvignon Blanc, and likely an unknown Vitis sp., respectively.

Because each seed in a cluster of grapes is genetically slightly different, Cabernet Doré’s sibling is Crimson Cabernet. It is a relatively young variety in the hybrid field, the first cross being made in 2001 and the patent applied for in 2007 (USPP20, 915 P3). The breeder was Lucian W. Dressel, who lists his address on the patent form as Carrollton, Illinois, but also has ties to one of the most famous and pioneering grape breeders, Dr. Harold Olmo, who had a long career at UC-Davis and mentored countless breeders in his career.

With the variety a relative newcomer in the world of grapes compared to some of the Old World varieties like Chardonnay or Sauvignon Blanc, it will take time to catch on with those growers and winemakers in the regions that is was bred for. It is reported to be growing in 32 of the 50 states here in the U.S., from Minnesota to Texas and Maine to California, primarily in states east of Colorado and clustered around Illinois where Dressler first established it.

It is a relatively young variety in the hybrid field, the first cross being made in 2001 and the patent applied for in 2007.

125 lbs. (57 kg) Cabernet Doré fruit

Distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 grams of KMBS, dissolve into about 75 milliliters (mL) of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g Lallemand QA23 yeast (or a favorite white wine yeast)

10 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

6-gallon (23-L) plastic bucket

6-gallon (23-L) carboy

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

Airlock/stopper

Racking hoses

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

Refrigerator (~45 °F/7 °C) to cold settle the juice

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 55 °F (13 °C)

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 mL

1. Crush and press the grapes. Do not delay between crushing and pressing. Move the must directly to the press and press lightly to avoid extended contact with the skins and seeds.

2. Transfer the juice to 6-gallon (23-L) bucket. During the transfer, add 16 mL of 10% KMBS solution (This addition is the equivalent of 40 ppm SO₂). Move the juice to the refrigerator.

3. Let the juice settle at least overnight. Layer the headspace with inert gas and keep covered.

4. When sufficiently settled, rack the juice off of the solids into the 6-gallon (23-L) carboy. Leave some headspace for expansion during fermentation.

5. Add Fermaid K or a similar yeast nutrient.

6. Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 104 °F (40 °C). Do not exceed this temperature as you will kill the yeast. Sprinkle the yeast on the surface of the heated water and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast

suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). Acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the cold juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. When the yeast is ready, add it to the carboy

7. Initiate the fermentation at room temperature ~(65–68 °F/19–20 °C) and once fermentation is noticed, (~24 hours) move to a location where the temperature can be maintained at 55 °F (13 °C). If using the refrigerator, be sure to monitor your fridge temperature as some older models can be too cold even at the warmest temperature. If your fridge is too cold (colder than 55 °F/13 °C), consider placing the carboy in an ice bath and add ice to the water as needed while monitoring the temperature. If your refrigerator is dedicated to winemaking, there are some aftermarket temperature controllers that can be wired in.

8. Two days after fermentation starts, dissolve the DAP in as little distilled water required to completely go into solution (usually ~ 20 mL). Add directly to the carboy.

9. Normally you would monitor the progress of the fermentation by measuring Brix. One of the biggest problems with making white wine at home is maintaining a clean fermentation. Entering the carboy to measure the sugar is a prime way to infect the fermentation with undesirable microbes. So at this point, the presence of noticeable fermentation is good enough. If your airlock becomes dirty by foaming over, remove it and clean it and replace as quickly and cleanly as possible. Sanitize anything that will come in contact with the juice.

10. Leave alone until bubbles in the airlock are appearing at a rate of about one bubble per minute.

11. After about two to three weeks it is time to start measuring the sugar. Sanitize a wine thief; remove just enough liquid to use for your hydrometer. Record your results. If the Brix is greater than 7 °Brix wait another week

before measuring. Discard the juice. If the Brix is less than 7 °Brix; begin measuring every other day.

12. Continue to measure the Brix every other day until you have two readings in a row that are negative and about the same. This should be -1.5 °Brix or lower for a dry wine.

13. Taste the wine for dryness and overall acidity balance. If it is too tart, consider a malolactic fermentation. Move to the next step when desired results have been met.

14. When appropriate, rack to the 5-gal. (19-L) carboy and control for headspace. Add 16 mL 10% KMBS solution, lower the temperature, ~45 °F (7 °C).

15. Let the lees settle for about 2 weeks and stir them up. Repeat this every 2 weeks for eight weeks. This will be a total of four stirs. This is called the bâttonnage. You’re doing this to enhance the mouthfeel. The whole process is called sur lie aging.

16. After the second stir, check the SO₂ and adjust to 30–35 ppm free.

17. Let the lees settle. At this point, the wine is going to be crystal clear or a little cloudy. If the wine is crystal clear, that is great! If the wine is cloudy, then presumably, if you have kept up with the SO₂ additions and adjustments, temperature control, kept a sanitary environment, and there are no visible signs of a re-fermentation, then this is most likely a protein haze. If you choose to, you can fine with bentonite to clarify.

18. While aging, test for SO₂ and keep maintained at 30–35 ppm. Titratable acidity (TA) target is about 6.5 g/L. The pH target is around 3.4–3.5, but rely more on the TA as that contributes to mouthfeel. You do not want an overly acidic (by mouth) wine.

19. Once the wine is cleared it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about six months after the onset of fermentation. If all has gone well to this point, given the quantity made, it can probably be bottled without filtration. Your losses during filtration could be significant. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling and you should have a fine example of a clean, creamy Cabernet Doré wine. Enjoy!

Yield 5 gallons (19 L)

A challenge to catching on in the marketplace is the fact that there are so many other good hybrids out there that name recognition comes slowly. And that was always discussed as a stumbling block in the breeding program I worked with. When the final selections are launched in the public, they are touted as a great winemaking grape with characteristics for where they should be grown and why they were grown there. Cabernet Doré has an advantage over some others in this department in that it is like its betterknown grandparent — Sauvignon Blanc.

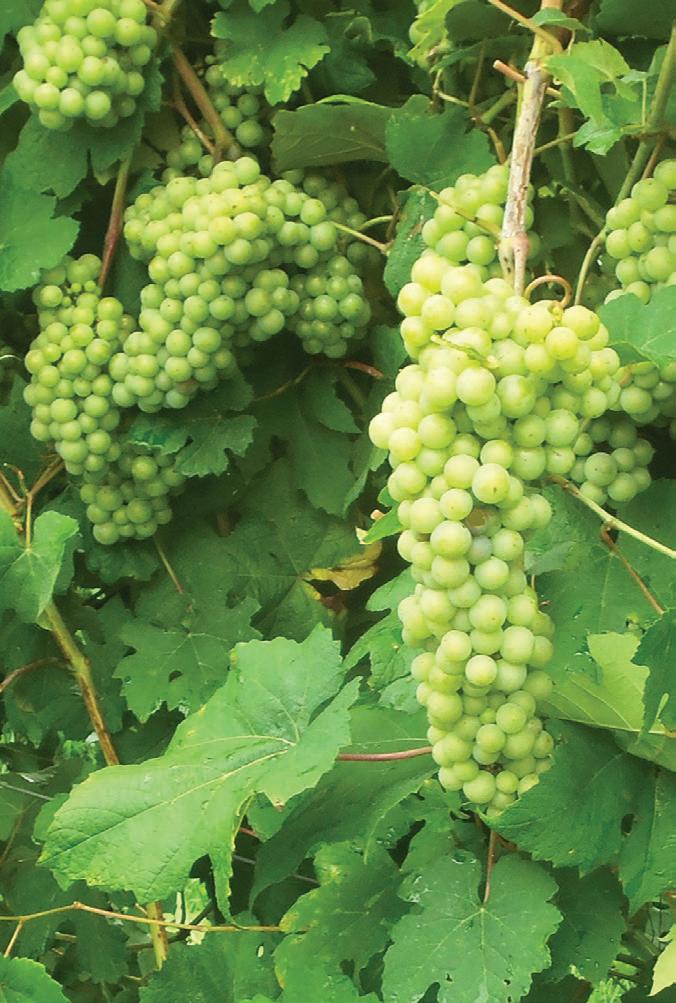

It is reported to propagate moderately well from cuttings. It has an abundance of tendrils and easily adapts itself to various wire-training systems. Bud break and flowering is fairly late and it generally sets a moderate crop. The berries are small to medium in size with a waxy bloom at maturity. It is a fairly vigorous vine when grown in fertile soil (but not as vigorous as Norton) so space should be given between vines and rows. Ten-by-eight plantings was recommended in the original patent, which means 10 ft. (3 m) between rows and 8 ft. (2.4 m) between vines in each row. But your soil vigor will dictate what is best in your vineyard.

It has excellent cold hardiness, disease resistance, good productivity, and does not need to be grafted. The harvest parameters I found reported were Brix in the 23 °B range, pH ~3.4, and a relatively high TA of 8.7 g/L. While this may be a perfect start for a dry white wine, your own local growing conditions and seasonal variations will be your limiting factors. With a fairly late flowering, hoping for a warm, sunny fall to hasten ripening is everyone’s dream with this variety.

The fruit can be fermented to produce dry white wines with a Sauvignon Blanc-like character. Depending on your equipment, typically you should destem then crush the fruit and then transfer to your press to extract the juice. For smaller lots, remove the berries by hand and then transfer them to a press bag (like a muslin bag found commonly in use in homebrewing) and lightly squeeze, collecting the juice.

Once the juice has been extracted, you can travel down two different paths. The first option is to cold-settle the juice, rack, and then ferment with your favorite white wine yeast. The other is to skip the cold-settling process and move directly to fermentation. The former wine will produce a crisp dry white wine, pale and straw in color, the latter having more golden hues from the solids contact and per-

haps more herbaceous characters. I generally recommend to cold-settle, but that is a stylistic choice and one you need to make on your own.

One thing you will not get is the flavor associated with the Native American grapes in its lineage. It would be a winemaker’s choice, based on initial taste assessment of the newly fermented wine, to conduct a partial or complete malolactic fermentation (MLF). In any case, Cabernet Doré would benefit from short aging on the lees, with or without stirring, and bottling after a few months.

I have recently been experimenting with using a touch of French oak with some Sauvignon Blanc-based wines. Having not been a fan of moderate to heavily oaked white wines and the micro-oxygenation process associated with them, I was turned onto a brand new François Frères 30-gal. (114L)barrel. With these smaller barrels, the interior surface area-to-wine volume ratio is increased, which can lead to faster extraction of the primary characters of the new oak barrel, like cream, vanilla, and butterscotch. My goal was to get some subtle oak characters that could be blended back into the all-stainless steel for a “fumé” character reminiscent of the same styled Sauvignon Blanc wines made popular by Robert Mondavi in the 1960s and 70s.

Cabernet Doré produces golden-yellow white wines with aromas of pineapple, papaya, banana, and delicate Muscatel. With some oak contact you can enhance the creaminess of the body, with a little mouthfeel and complexity that is slightly reminiscent of butterscotch and vanilla. The use of oak cubes and staves should also achieve similar benefits. As always, I caution to use these adjuncts carefully, in that the same relationship of surface area-to-wine volume applies. Many manufacturers will put the recommended usage and time interval on their packaging. Using a higher dose rate may achieve faster results, but a lower dose rate may not achieve those same results, since the extractable flavors could be depleted. This is the craft of winemaking, some call it art.

A final thing of note that I found in my research for this article is that Cabernet Doré was one of the fastest ever commercial releases for a new hybrid variety. As previously mentioned, the first seedlings that come out of the breeding process take about 5–6 years to produce enough fruit for trial winemaking (then there is all the work that goes into the seedlings in the same trial that did not make the cut).

Cabernet Doré and its sibling, Cabernet Crimson, succeeded and showed enough promise to get that patent expedited. The stars were aligned with this one. Try it if you can, I think you’ll like it!

Cabernet Doré produces golden-yellow white wines with aromas of pineapple, papaya, banana, and delicate Muscatel.

Looking to advance your winemaking knowledge?

Check out these wine education programs to start your journey down the path to a higher education in winemaking and the business of wine.

Our coursework is recognized for combining the science of winemaking with hands-on vineyard experience. Choose from degree or certificate programs, with options to specialize in viticulture or enology — and study online.

FLCC Viticulture and Wine Center, Geneva, New York VISIT FLCC.EDU/WINE

May 30 – June 2, 2024 • Charlottesville, Virginia

Join us in the birthplace of American wine – the Monticello AVA in historic Charlottesville, Virginia – for four days of winemaking learning and fun. Thomas Jefferson planted the first commercial vineyard here in 1774 and there are now 40 local wineries continuing his legacy. Don’t miss exploring this history-laden region in the Blue Ridge Mountains and our dozens of winemaking and grape growing workshops and classes. You can save your spot at what should be another sold-out East Coast conference, plus save $100 when you register now. See you in Virginia in 2024!

EARN A CERTIFICATE IN

■ Viticulture ■ Enology

EXPLORE SELF-DIRECTED COURSES IN

■ Wine Chemistry

■ Wine Microbiology

■ Wine Production

■ Winery Equipment

■ Sensory Evaluation

■ Growing Grapes

■ Disease Management

REGISTER NOW wine.wsu.edu/certificate

by Phil Plummer

by Phil Plummer

Every Spring, as buds begin to swell and break in vineyards of the Northern Hemisphere, a different but no less exciting ritual occurs in their associated cellars: The arrival of fermentation supply catalogs. Bright and inviting, they’re filled with a dizzying array of the latest and greatest yeasts, nutrients, fining agents, etc.; everything a winemaker might want to ensure the coming vintage lives up to its full potential. But if you’ve been leafing through them over the last 10–15 years, you may have noticed a new trend taking root in their pages: An emphasis on harnessing or mimicking wild fermentation. If that seems counterintuitive to you, you’re not wrong. Why would yeast manufacturers with millions of dollars tied up in producing and promoting highly selected strains be throwing attention on anything as freely available as wild yeast and bacteria? The answer is simple: Complexity.

It’s no secret that the yeast and fermentation technologies that we all take for granted are new . . . like, really new. We’ve known the role of microflora in fermentation since the mid1800s, so it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that there were literally thousands of vintages on the books before the first-ever yeast pitch. But the ubiquity of wild microbes certainly didn’t make things easy on pre-modern winemakers. Think of every problematic fermentation you’ve encountered in your own cellar, and then remind yourself that all of that happened while our understanding of fermentation has been at its peak. That in mind, it’s easy to understand why the precision of our modern winemaking tools was so desired. Clean, predictable fermentations have allowed the wine industry to, for lack of a better term, industrialize. This consistency has made winemaking easier and more profitable while also greatly increasing the accessibility of the finished products. So why look backward? Again: Complexity.

The vast majority of Saccharomyces strains on the market have been isolated and purified from spontaneous fermentations — often from classic, Old World wine regions. Why, then, have winemakers in these regions opted to continue their tradition of spontaneous fermentation while safer, more predictable versions of their native yeast strains are so widely available? As it turns out, Saccharomyces is just one player in the biological drama of indigenous fermentation.

Honed by natural selection, Saccharomyces is perfectly optimized for winemaking. Its ability to withstand the unique chemistry of must and wine allows it to develop strong populations that dominate the microbiome of a fermentation. As the population grows, consumes resources, and generates alcohol, it quickly outcompetes and silences its non-Saccharomyces rivals. However, in the time it takes Saccharomyces to build dominant populations, there’s room for other yeasts

and bacteria to thrive and impact flavor and aroma. That lag phase window is where our problem lies.

Fresh must is teeming with microbes. Some of them, like Saccharomyces and Oenococcus, are prized for their positive effects on fermentation and wine quality, while others, like Brettanomyces and Acetobacter, send chills up the spine of most winemakers at their mere mention. Absent intervention, these microbes are allowed to compete against each other until one (generally Saccharomyces) gains a competitive advantage. Unfortunately, it can sometimes take several days for Saccharomyces to dominate, which leaves an awful lot of time for their less desirable counterparts to do damage. The result can often be disastrous: Wines that are marred by flaws before they’re even finished fermenting.

The early interventions that many of us employ in our cellars are aimed at averting catastrophe. Techniques like must stage SO2 additions have the effect of killing or suppressing a wild, unpredictable microbiome until Saccharomyces can take over. However, this can still take quite some time if not aided by the winemaker’s hand — that’s why inoculation is such a valuable tactic. By adding a large population of highly specialized, competitively advantaged yeast to a must, the winemaker is able to limit the amount of time it takes for that yeast to establish dominance. This quickly limits the opportunities for spoilage microbes to take root and makes the overall fermentation management far more predictable — a welcome shift at an already chaotic time in the winemaking process.

But what if not all the non-Saccharomyces microbes in a must are negative? As it turns out, there are a host of species that fit this description, capable of contributing positive qualities to a wine if allowed an opportunity to do their work. Aggressive and early interventions like heavy-handed SO2 additions and inoculation with Saccharomyces, while increasing the predictability and ease of fermentation, deny these other microbes an opportunity to leave their mark and

may in fact put a cap on the flavor and aromatic potential of these wines at an early stage. Therein lies the conundrum of spontaneous fermentation: By leaving room for non-Saccharomyces microbes to work, the potential for greatness and/or disaster is increased.

With this in mind, yeast manufacturers set out to harness the magic of wild fermentation, separating its best elements from its worst and aiming to develop a toolkit for winemakers who desire more complexity with fewer complications. The first step in this process was to characterize the species and strains most commonly found in spontaneous fermentations, then determine the strengths, weaknesses, and metabolic attributes of each. From there, a wide variety of products have come to light, including commercially available non-Saccharomyces strains and SO2-free bioprotectants. Implementing some or all of these in a strategic manner allows a winemaker to make unique, complex wines without the associated spoilage risks of a truly wild fermentation.

Of all the tools aimed at capturing the best of wild fermentation, none are easier to apply or manage than commercially available non-Saccharomyces yeasts (though it should be noted that most of these are only packaged in sizes intended for commercial winemakers, for now). Developed to be used in conjunction with Saccharomyces, these yeasts impart aromatic and textural precursors to the wine that may then be revealed via alcoholic fermentation. The theory behind these products is the same as their Saccharomyces counterparts: By inoculating must with a sizable population, you give them a chance to outcompete the indigenous microflora, leading to cleaner, more manageable fermentations. So what do these yeasts bring to the table that Saccharomyces doesn’t? That depends on which one you use.

Likely the most commonly used non-Saccharomyces yeast, Torulaspora delbrueckii, has a wide range of posi-

tive attributes that lend themselves to versatile winemaking applications. From an aromatic standpoint, Torulaspora is a fantastic ester producer, increasing the potential for fresh fruit and floral aromatics. On the palate, it’s an excellent driver of weight, producing acid-balancing glycerol and influencing overall roundness. In addition to its applications in traditional ferments, Torulaspora’s tolerance of high-sugar musts can be leveraged to limit volatile acidity (VA) production in late harvest and ice wines. With an alcohol tolerance of 7–10%, this yeast may be used on its own; however, using it in conjunction with a compatible Saccharomyces strain (inoculated after 1–5 ºBrix depletion) is suggested if fermentation to dryness is desired.

In addition to Torulaspora, Metschnikowia yeasts have also been found to have desirable effects on fermentation. Though largely non-fermentative themselves, commercial strains of Metschnikowia pulcherrima may be used to shape aroma and mouthfeel. These preparations are perfectly suited for aromatic whites like Riesling, Gewürztraminer, or Traminette because of their ability to generate large amounts of terpene and thiol precursors that may then be released by compatible Saccharomyces yeasts during alcoholic fermentation.

From a textural standpoint, Metschnikowia rapidly contributes mannoproteins, the polysaccharides often associated with lees aging, contributing a rounded quality to the overall mouthfeel of a wine. Metschnikowia also does a great job of making life difficult for other wild microbes, gaining population quickly and scavenging valuable resources like the dissolved oxygen and minerals required by most spoilage microbes; this has led to its application as a bioprotectant (more on that in the next section). Metschnikowia is only alcohol-tolerant to around 3% ABV, so it’s imperative that it be followed by inoculation with a Saccharomyces strain to complete the fermentation. This inoculation should be performed 24–48 hours following the Metschnikowia pitch.

Though the mechanics of their use are largely the same as familiar Saccharomyces rehydration and inoculation, these yeasts are a bit less resilient and require specific must parameters to survive and thrive. First, winemakers should be aware that the SO2 tolerance of these yeasts is extraordinarily low; it’s important that the free SO2 of the must be no higher than 20 ppm prior to pitching. Another chemistry consideration that winemakers ought to think about when using these yeasts is yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN). The manufacturer’s YAN guidelines for the Torulaspora and Metschnikowia strains I use most often (Lallemand’s BiodivaTM and FlaviaTM, respectively) call for YAN greater than 150 ppm; this may be adjusted using complex yeast nutrients or diammonium phosphate (DAP). A final parameter that may affect the health of non-Saccharomyces yeasts is must temperature. Though their ideal fermentation temperatures are right in line with most Saccharomyces strains, using these yeasts in the

two-step inoculation process we’ve been discussing doesn’t give them a whole lot of time to work — getting your must temperature in line with their optimal range prior to pitching helps to maximize their effect.

If inoculating with commercial nonSaccharomyces yeasts still isn’t adventurous enough for you, you’ll be glad to know that there are also tools available to improve the efficacy of truly native ferments. Designed with an eye toward inhibiting the sorts of microbes that make wild fermentation scary, these tools provide winemakers with an effective mechanism for shaping must microbiomes. When paired with the right fermentation management strategy, they can have a profound effect on the quality of the resulting wines.

If you’ve been following along so far, you’ll recognize the first of these tools: Metschnikowia yeasts. Slight-

ly di erent strains than those used for amplifying aromatic precursors, these yeasts may be deployed for biocontrol — rapidly scavenging dissolved oxygen while also producing metabolites that have a suppressant e ect on wild microbes. By inhibiting organisms that produce VA and other o -aromas, these yeasts keep a must safe until native Saccharomyces can establish dominant populations. The Metschnikowia strains selected for this purpose are also a bit more cold-tolerant, making them extremely well-suited to cold soaks. They’re most often inoculated in juice or must, but can be added at the crusher or even sprayed on fruit pre-harvest to limit microbial pressure during processing. As with the other non-Saccharomyces yeasts discussed, a restrained approach to SO2 use pre-fermentation is critical for ensuring successful implementation.

Another indispensable tool for improving the quality of native ferments should be old hat for many home winemakers: Chitosan. While traditionally used for clarification, fungal chitosan has an ability to bind and/ or destroy the cell walls of spoilage microbes like Acetobacter, lactic acid bacteria, and Brettanomyces, all while allowing favorable yeasts like Torulaspora, Metschnikowia, and Saccharomyces to proliferate. Additionally, its chelating abilities allow it to remove heavy metals from juice and must, greatly decreasing the potential for downstream oxidative defects, and, as with Metschnikowia, allowing the winemaker to use less SO2. Chitosan may be deployed in the same manner as a fining agent, though care must be taken to select an appropriate preparation; most are well-suited to juice applications, while other, more specialized preparations are designed for use in whole-fruit fermentations.

While these biocontrol products are excellent additions to the wild fermentation toolkit, they’re even more powerful when paired with a timeless, Old World culturing technique called “Pied de Cuve.” French for “foot of tank,” Pied de Cuve is effectively the wine world’s answer to a sourdough starter. Ahead of harvest,

a small amount of grapes are picked and crushed, the native yeasts are allowed to start fermentation, and the fermentation is regularly fed with fresh grapes or juice. This helps to build a large and healthy yeast population that may then be added to must as an inoculum. Some extra complexity may even be gained by including items from the vineyard and surrounding area that may be sources of wild yeast cells: Wildflowers, fruit, stones, and tree bark among them. Pied de Cuve also allows winemakers to evaluate their wild microbes before adding them to more consequential volumes of must; if evidence of spoilage microbes is present, there is an opportunity to shut them down early. Chitosan and Metschnikowia may be used to great e ect here: Either can be added to the must upon crush as a prophylactic; chitosan may be added to refine the microbiome if undesired species announce their presence. This combination of culturing technique and biocontrol products puts clean, complex wild fermentations within reach for winemakers of any experience level.

Commercial Saccharomyces yeasts may be prized for their predictability and ease of use, but the complexity gained from wild and non-Saccharomyces fermentation is undeniable. With unique and compelling contributions to aroma, flavor, and texture, it’s not hard to see why winemakers and yeast manufacturers alike have set out to harness this potential. New products like non-Saccharomyces yeasts allow even the most cautious winemakers an opportunity to flirt with this wilder style. For more adventurous vinification, combining biocontrol products like chitosan with the time-tested Pied de Cuve technique allows for wild fermentations without many of the rough edges we’ve come to expect of them. It’s a brave new world with Old World sensibilities. So if you’re looking for new ways to bring out the most in your wines, try taking a walk on the wild side — it’s never been easier.

SO2 (Free & Total)

Titratable acidity (TA)

pH

Malic acid (MLF)

Residual sugar (new!)

In 14 years of assisting home winemakers in a beer and winemaking shop, questions about sulfites came up often. While some hobbyists were bound and determined to use no sulfites in their wine, most wanted practical advice to help produce a sound, pleasant, drinkable wine in the finished bottle. While “no sulfites” is at least a simple program to apply, it has never been my choice as the most reliable way to make good wine. Lots of theoretical information is out there — and we will necessarily touch on a bit of theory today — but most practical is a simple, prescriptive approach that has long proven to be almost always successful. That is what I am describing here.

To be clear on concepts and terminology, we will cover some basic facts about sulfur. Chemically speaking, sulfur is a reactive element that can adopt a range of oxidation states. The dreaded “rotten egg” smell of hydrogen sulfide, H2S, represents one end of the oxidation scale with sulfur in the minus two oxidation state. At the other end of the scale are some sulfur compounds in plus oxidation states. One of these is today’s subject: Sulfite. Sulfite refers to the ionic form in aqueous solution (water or wine) that is noted by the symbol SO32-. Depending on the pH of the solution, a portion of sulfite ion combines with a hydrogen ion, H+, to form the bisulfite ion, HSO3-. The reason you hear sulfite additions sometimes called SO2 additions is because that compound, sulfur dioxide, is a gas that reacts to form sulfite and bisulfite ions when it is dissolved in wine. An important note is that in acidic (low pH) solutions, a tiny fraction of the sulfite also occurs in the molecular form, dissolved sulfur dioxide, regardless of how it was introduced to the wine. While you may hear a winemaker say they add “sulfur” to their wine, it is only meaningful if they are adding sulfite. Commercial winemakers may actually add sulfur dioxide gas, but that material is too hazardous for home use. We use other forms of sulfite.

Before details or “how,” here is a little bit of “why.” For my practical program, I apply a consensus approach that I have heard from many commercial winemakers. While it may not have exact theoretical justification, it seems to work well. The target under this program is to maintain 0.5 mg/L (parts per million, ppm) of molecular sulfur dioxide in red wines and 0.8 ppm in white and rosé wines. At those levels, the added sulfite helps protect against oxidation and browning of the wine while also inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms. One drawback to those cited levels is that we do not have practical means of analysis for molecular sulfur dioxide in wine. However, there is a well-understood relationship between the amount of molecular sulfur dioxide and the sum of sulfite and bisulfite ions at a given pH. That sum is referenced as “free” SO2, and we do have reliable analytical methods for it. Since the ratio is pH-dependent, there are various calculator tools and charts to help interpret it. One such calculator is at Winemakermag.com/ sulfitecalculator. Table 1, below, illustrates some of the ratios at the 0.5 and 0.8 ppm levels.

Along with guiding sulfite additions, this table is a good reminder of why we try to keep pH low in our home winemaking. Since se nsitive tasters can begin to detect the presence of sulfite at about 50 ppm, it may be difficult to produce a high-pH wine without suffering an unpleasant “burnt match” aroma or giving up some level of protection.

For initial additions of sulfite to your wine, you can simply add the recommended amount as dictated by the pH. But how will you do that?

Home winemakers use various forms

of the solid material potassium metabisulfite, chemical formula K2S2O5, which dissociates in water (or wine) to produce two positive potassium ions and two negative sulfite ions. The sulfite ions distribute into sulfite, bisulfite, and molecular sulfur dioxide according to the pH of the solution. While sodium metabisulfite (Na2S2O5) would work the same way, we do not want to introduce sodium salts to our wines that might be harmful to a person on a sodium-restricted diet.

Potassium metabisulfite goes by several nicknames in winemaking: Pot meta, KMBS, KaMBuS, Campden tablets, and sometimes (confusingly) just “sulfur.” We will stick with its full name or chemical formula here to remain perfectly clear, but be aware that you may hear these other names. If you work with the powder itself, a key factor is that a given weight of potassium metabisulfite yields 57.6% of that weight as sulfur dioxide when it is dissolved in water. That is, adding 100 g of the solid produces the same final concentration as adding 57.6 g of the gas. These ratios come about for two reasons. The first is that the potassium ions play no role in the sulfite concentration and are just along for the ride. The second is that chemical term “meta” in the compound’s name. In this chemical context it means something like “about to become.” That is because the S2O52- produces the equivalent of two SO2 molecules upon dissolving, those react to form (partly) bisulfite, so the solid was “about to become” potassium bisulfite when dissolved in water or wine. The important takeaway is that you get 57.6 g of sulfur dioxide out of every 100 g of potassium metabisulfite.

Here are some ways you can use

potassium metabisulfite in your wine program. To help with comparisons, each method is given with an addition to a 5-gallon (19-L) carboy of wine. Using the powder itself, if you add one gram of potassium metabisulfite you are adding 576 mg of SO2 That 576 mg in 19 L is an addition of 30.3 mg/L. It is much less accurate to measure a powder by volume, but if you don’t have a small scale to weigh gram quantities, it may be your best choice. At the midrange of 1.25 g/mL a teaspoon (5 mL) of potassium metabisulfite powder weighs about 6 g or a quarter teaspoon contains about 1.5 g.You can use that weight estimate to make a corresponding addition. A quarter teaspoon in 5 gallons (19 L) is about 45 ppm (1.5 x 30.3 ppm).

Campden tablets are a pre-measured form of potassium metabisulfite compressed into a pill that needs to be crushed and stirred into a bit of water or wine before you add it. They are most commonly sold at a size that produces 65 mg/L when added to one gallon (3.8 L) of wine. To continue our comparison of 5-gallon (19-L) volumes, one tablet crushed and added to that carboy would introduce 13 mg/L of SO2. Note that you do not need to account for the difference between the weight of potassium metabisulfite and the yield of SO2, as the tablet manufacturer has already taken that into account. Check your package label when you buy Campden tablets as other sizes are sometimes produced.

With stirring often recommended for solid additions of potassium metabisulfite, I prefer to work with a solution so I can make the addition quickly and re-stopper the carboy or barrel with less air exposure. For small quantities of wine, it is convenient to make a 3% solution. You can purchase potassium metabisulfite powder in a 4-oz (113-g) bag and dissolve the entire contents in a gallon (3.8 L) jug of distilled water. Label it “3% Potassium Metabisulfite,” add the date and mark it “Poison” and you are ready to go. If you are making larger quantities of wine, you may find a stronger 10% solution suits your needs better. To make that, dissolve 100 g of potassium metabisulfite powder in about

900 mL of distilled water. Dilute up to exactly one liter, label as “10% Potassium Metabisulfite” plus the date and “Poison.” Note that these percentage figures, 3% and 10%, reference the whole powder, so the SO2 content is, as noted earlier, 57.6% of that value. A 3% solution contains 0.03 x 57.6 or 1.7% SO2 and a 10% solution contains 5.76% SO2. From those values you can calculate your needed addition to any volume of wine, or you may find it quick and convenient to use a reference chart. A graduated 10-mL pipet is convenient for adding portions of 10% solution while common kitchen tablespoons (15 mL each) work well for 3% solution. Table 2 is filled out for additions to 5 gallons (19 L) of wine, using either tablespoons (Tbsp.) or milliliters (mL).

There is another method only