HISTORIC

VOLUME

Bibliography

Building

HISTORIC

VOLUME

Bibliography

Building

The purpose of this Architectural and Historical Significance Report is to guide the development and implementation of a treatment plan for the Athens Chancery, a historic structure listed in the Secretary of State’s Register of Culturally Significant Property. Using documentary research and physical examination, this report documents the history and construction chronology of the chancery; describes its as-built condition and changes to the original design; evaluates its significance and integrity; and identifies the visual aspects and physical features that define its essential character. This report evaluates all aspects of the historic structure as well as its associated landscape and site features. By recording the historic appearance of the chancery and identifying its character-defining features, this report serves as an effective management tool for selecting the most appropriate approach to treatment prior to the commencement of work.

The contents, format, and objectives of this report follow the guidelines for preparing Part I of a Historic Structure Report as set forth by the National Park Service in two publications: “NPS-28: Cultural Resource Management Guideline” (specifically Chapter 8: Management of Historic and Prehistoric Structures) and “Preservation Brief 43: The Preparation and Use of Historic Structure Reports.” As such, this report focuses on the developmental history of the Athens Chancery with sections on historical background and context, chronology of development and use, and evaluation of significance. The NPS guidelines also provided the process for conducting work and formatting the report.

Research methods used in the preparation of this report included the examination of both primary and secondary resources. Primary source material included historic architectural drawings and details provided by the State Department’s Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations and historic photographs in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums, Busch-Reisinger Museum (available online).

Extensive research was carried out at MIT’s Rotch Library of Architecture and Planning, which holds The Architects Collaborative Archives. This archive included substantial documentation on the Athens Chancery, including correspondence, contracts, project reports, specifications, and other primary source materials. Additional research on the building’s development, as well as contextual research related to the history of diplomatic facilities in Athens, was carried out at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. Secondary source material included contemporary architectural journals, newspaper articles, and monographs on architect Walter Gropius. Books related to the State Department’s overseas building program, such as Jane Loeffler’s The Architecture of Diplomacy, provided contextual history on diplomatic facilities. Studies such as Robinson & Associates’ Growth, Efficiency, and Modernism: GSA Buildings of the 1950s, 60, and 70s provided background on federal architecture of the period.

On-site evaluations of the Athens Chancery and its associated landscape and site features occurred over a four-day site visit in October 2012. Site evaluations involved the documentation of physical evidence of the building’s original construction and subsequent modifications and the verification of existing conditions. Research tasks at the chancery included the review of architectural drawings, surveys, and project files, as well as a comprehensive set of historic photographs documenting the construction and as-built condition of the building, held by Office of Facilities Management. Other resources, including additional historic photographs, were located with the Office of Cultural Affairs.

The United States and Greece have a long-standing tradition of consular and diplomatic relations. The United States supported the emergence of modern Greece from its earliest days, establishing a consular post in Athens in 1837 shortly after Greece gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The organization of consular relations with Greece reflected the growing importance and volume of foreign trade and navigation relations for both economies. Later, in the 1870s, an American consulate was also established in the Greek port city of Thessaloniki. Diplomatic relations with Greece were established in 1868.1 The fact that diplomatic relations were formed several decades after the consulate was established was not unusual at the time. For much of the nineteenth century when American politics were focused on domestic issues, U.S. foreign relations emphasized good will toward other nations rather than the pursuit of an active policy that required formal overseas envoys.

With one exception, throughout the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, the U.S. government did not own property abroad and did not provide official consular accommodations or residences for its foreign envoys.2 Thus, America’s earliest consular and diplomatic facilities in Athens were most likely leased spaces in modest residential buildings.3 In 1907, for example, the American consulate in Athens operated out of the ground-floor rooms of the consular officer’s home, which was located in a residential quarter “near the leading hotels and near principal exporters.”4 The house was leased, with the U.S. government contributing $500 annually — the maximum amount allowed at the time

1. The first Minister Resident in Athens was Charles K. Tuckerman. At the time, U.S. envoys overseas were known as “ministers.” The change from ministers to ambassadors and legations to embassies was a gradual process that continued until the late 1960s when all U.S. chiefs of mission finally held the rank of ambassador. See “A Short History of the Department of State,” at <http://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history>.

2. Jane C. Loeffler, The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies, 2d ed. (New York: Princeton Arch. Press, 2011), 13. The exception is the American Legation in Tangier, Morocco, which was given to the U.S. as a gift in 1821 and is the longest-held property acquired abroad by the U.S. for a diplomatic mission.

3. For the purpose of this report, the location, character, and quality

for office rent — and the consul general providing the remaining balance of $137. It was typical for foreign service officers to rely on personal funds to supplement their time abroad. Critics of this arrangement, which many believed was undemocratic and favored the independently wealthy, began to demand reforms.

One of the first steps in modernizing American diplomatic and consular facilities abroad was the passage of the Lowden Act in 1911, which authorized the federal government to buy land and construct diplomatic buildings in foreign countries. The act signified a growing recognition of America’s global diplomatic role and the need for suitable representational offices and residences. Moreover, it supported a more professional and democratic foreign service. Perhaps as an indirect result of the Lowden Act, in July 1912, the American legation in Athens was relocated to a building described as “one of the best in Athens, large, thoroughly modern, and well adapted for all Legation purposes.”5 The new legation was located at 14 University Street in a residential structure formerly occupied by both Greek and German diplomats (see Figure 1).6

Another important step in expanding the scope and authority of the U.S. foreign building program was the passage of the Foreign Service Building Act in 1926. This act formalized the building program, created the Foreign Service Buildings Commission to oversee the purchase and construction of foreign buildings, and set up a dedicated fund to finance such projects.7 The Supervising Architect of the Treasury was initially responsible for the design and

of the earliest American consular offices and diplomatic legations were not identified.

4 “Form of Inspection Report,” July 19-27, 1907, Inspections Reports on Foreign Service Posts, Box 10, Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland (hereafter cited as RG 59, NARA).

5. Letter from George H. Moses to Secretary of State, June 6, 1912, General Decimal Files 1910-29, Box 1896, RG 59, NARA.

6. The American legation in Athens was located at 14 University Street from 1912 through the 1920s and possibly up until 1938, when the government took out a new lease on a building at 2 Vasilissis Sofias Avenue for use as an embassy.

7. Loeffler, Architecture of Diplomacy, 19.

supervision of all foreign building projects under the act. Later, greater authority was given to contract with private architects, although the Treasury almost always remained responsible for preparing working drawings and specifications and had final design approval.8 In the late 1930s, the Foreign Service Buildings Commission was transferred to the State Department. Following World War II, its functions gradually diminished to a largely advisory role, as the responsibilities of choosing overseas sites, selecting architects, and approving plans for foreign buildings were transferred to the State Department’s Office of Foreign Buildings Operations.

1.2 The Office of Foreign Buildings Operations in Athens after World War II

With the United States emerging from World War II as a preeminent power with vastly increased global responsibilities, the State Department’s Office of Foreign Buildings Operations (FBO) experienced a period of enormous growth. To meet the State Department’s objective of amplifying America’s presence abroad, the FBO significantly expanded its foreign building program. It benefited from the ample supply of discounted properties available on the overseas markets following the war and from readily available funds. In 1946, the State Department received congressional authorization to use $110 million in postwar foreign credits for overseas acquisitions and construction projects. This had the profound effect of greatly expanding the FBO’s financial resources. It also allowed the State Department to bypass the usual budgetary review process, and, because they were nontax dollars, Congressional oversight was minimal. Foreign countries that owed the United States for wartime

loans could repay their debts by supplying building materials, equipment, or local labor. For example, foreign credits were used to acquire teak from Burma and marble from Greece and Italy for FBO projects.9 It also gave the State Department’s foreign building program the benefit of being strongly endorsed by politicians as a way to recoup American assets following the war.

As a way of improving America’s presence abroad, the FBO during this period began to rely less on the use of leased quarters, which were frequently located on scattered sites across cities, and started to shift toward the development of consolidated U.S. government-owned properties. Consequently, large, multipurpose office buildings replaced traditional, residential-type diplomatic buildings.10 This new building type allowed the FBO to accommodate both diplomatic and consular activities in one location as well as staff from other government departments that stationed representatives abroad (such as Defense, Commerce, Agriculture, and Justice, among others). Also during this period, it became more common for the FBO to award design commissions to private architects, as it was believed to be an economical option that would provide the best design solutions.11

At the start of World War II in Europe, the American legation in Athens was located in a leased four-story building located at 2 Vasilissis Sofias Avenue built as an apartment building (see Figure 2). In 1941, the United States closed its legation in Athens due to the Nazi occupation of Greece. The office was relocated to London, and later Cairo, where Greece had established exile governments. The American legation was elevated to embassy status during this time with Anthony J. Drexel Biddle, Jr., serving as the

10. In the early years of the Foreign Service Buildings Commission and the FBO, the properties most often occupied by American representatives were palatial villas or grand houses, and new diplomatic buildings were modeled on this residential building type. Embassies from this period often reflected American Colonial Revival styles with iconic buildings such as the White House or Monticello serving as design influences. See Loeffler, Architecture of Diplomacy, 24.

11. Ibid., 57.

first Ambassador. The American embassy returned to Athens in 1944, reassuming its former location. Two years later the Greek government entered into a civil war against forces controlled by the Greek Communist Party. Amid this crisis — one of the first conflicts of the Cold War — President Harry S. Truman delivered a speech to Congress requesting military and economic support for the government of Greece, as well as Turkey, against the Communist threat. Under the tenets outlined in this speech, which became known as the Truman Doctrine, American foreign policy was fundamentally reoriented to actively provide political, military, and economic assistance to all democratic nations threatened by authoritarian forces.

During this period, the U.S. had an important stake in democratic Greece, and, under the Truman Doctrine and later the Marshall Plan, the U.S. dedicated considerable economic aid as well as political and military resources to foster the country’s stability. As a consequence, the U.S. government acquired a considerable number of foreign properties in Athens. By 1954, for example, the U.S. owned or leased five office buildings, eighteen residential buildings, three garages, three parking lots, one hospital, one cold storage space, and four warehouses. The embassy (formerly the legation) continued to occupy leased office space at 2 Vasilissis Sofias Avenue although it was considered deficient by embassy staff and described as “in poor condition and totally inadequate because of small size, layout of building, obsolescent heating and electrical systems, and insecurity.”12

The Farragi Building, located at 59 King Constantine Street, was a U.S.-owned property acquired in 1948

12. “Statements to Facilitate Inspection,” March 1, 1954, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 9, RG 59, NARA.

13. See “U.S. Building Stoned,” New York Times, 15 December 1954 and Memorandum “Preliminary Program for Embassy Office Building, Athens, Greece,” March 21, 1956, The Architects Collaborative Archives, Rotch Library of Architecture and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (hereafter cited as TAC Archives).

14. “Statements to Facilitate Inspection,” April 28, 1947, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 9, RG 59, NARA.

using surplus property credits. It housed the office of the consulate general and residences for American officials. Other American missions were located in the Tameion Building at 4 Churchill Street near Syntagma Square (see Figure 3). After the Tameion Building was stoned during anti-American demonstrations in 1954, an FBO report was issued indicating that, in general, the Athens facilities were inefficient, in poor condition, and provided unsatisfactory security.13

Countries such as Greece that were regarded as prime targets for Communist expansion by the State Department became the immediate focus for new FBO projects during the early Cold War period. A 1947 facilities assessment report for Athens noted that the State Department had authorized “an extensive program envisaging the acquisition of sites for, and the eventual construction of, an official establishment in Athens to take care of all official activities here.”14 The construction of a new, highly visible, embassy compound in Athens was seen as a way to strengthen America’s diplomatic presence in Greece and counterbalance Soviet expansion. Consolidating all diplomatic and consular activities into a single building would also save in rental and maintenance costs and provide for more coordinated operations.

By 1953, U.S. negotiations with Greece resulted in the donation of land for a new chancery site.15 The approximately 1.5-acre lot along Vasilissis Sofias Avenue had an estimated value of $1 million. It was bound by Vasilissis Sofias Avenue on the southeast and Makedonon Street on the northeast (see Figure 4). Proposed streets “A” and “B” created the northwest and southwest boundaries but were unimproved at the time of the land transfer. The land

15. The United States acquired the land for the chancery through two separate Deeds of Donation – the first on May 27, 1953, and the second on October 9, 1953. See “Statements to Facilitate Inspection,” March 1, 1954, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 9, RG 59, NARA.

had formerly been used by the Greek military, and historic plans and photographs indicate that Army barracks, a military monument, and an asphalt road were located on the lot, which was surrounded on three sides by a stone wall (see Figure 5).16 Although the neighborhood was not densely populated at the time, it was characterized as “New Athens… surrounded principally by hospitals, modern apartment houses, and government buildings, some already constructed and some planned.”17 In 1958, perhaps to help facilitate the planned move to the new chancery site, the U.S. government took out a lease on a seven-story office building at 102 Vasilissis Sofias Avenue opposite the chancery site. The U.S. occupied the entire building, with the top floor serving as residential quarters for the marine guards.

At any given time, the design of American diplomatic facilities is influenced by the image that the United States wants to convey to the world. Immediately following World War II, the objective of American embassy design was to present the United States as a global power while reflecting the ideology of democracy and the notions of freedom and openness. Under director Frederick Larkin (1946-52) and assistant director and supervising architect Leland W. King, the FBO established a reputation as a showcase for contemporary architecture.19 Modernism, opposed to the Neoclassical or Colonial styles, was believed to best represent democratic principles and American progressivism. Well-known architects were awarded foreign design commissions as a means to attract attention, generate positive publicity, and augment the impact of the FBO program. Examples from the

16. “Boundary and Topographical Survey,” May 12, 1956, in uncataloged drawings collection of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens, Greece (hereafter cited as the drawings collection of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens). A Greek journal article published in 1957 stated that the barracks of the First Infantry Division were located on the site. See translation of “A Doleful Architecture,” Ethos, June 29, 1957, TAC Archives.

17. “Statements to Facilitate Inspection,” March 1, 1954, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 9, RG 59, NARA.

18. The U.S. Dept. of State defines an embassy as “the diplomatic delegation from one country to another.” The term embassy, however, is often used to refer to the chancery – the office space

period include embassies constructed in Rio de Janeiro (1948-52) and Havana (1950-52) by Harrison & Abramovitz and the embassy in Stockholm (1951-54) by Rapson & van der Meulen.

By the early 1950s, however, critics in Congress began to express concern that America’s embassies had become too conspicuous and imperialistic. In response, the FBO proposed a new architectural policy under which future projects would continue to showcase high quality contemporary architecture but feature practical and unpretentious designs that fit in well with their surroundings and were admired by their hosts.20 To further enrich their new foreign building policy the State Department created the Architectural Advisory Committee (later known as the Architectural Advisory Panel and the Architectural Advisory Board) to provide oversight and review the quality of new designs. The committee was established in 1954, and its first members included notable and influential practitioners including Harry A. McBride, a former Foreign Service officer and administer of the National Gallery of Art, and architects Pietro Belluschi, Henry R. Shepley, and Ralph Walker. As a result of these measures, subsequent FBO projects featured high-quality modernist designs that responded to regional architectural traditions and demonstrated a respectful understanding of local culture.21

At the time, the process for selecting architects for State Department projects was largely undefined. The FBO, with input from the Architectural Advisory Committee, mainly awarded commissions to architects that were already known to them through the professional network. FBO staff and its advisors were attracted to leaders in the profession who would

where the Chief of Mission and his staff work – and other buildings for the offices of diplomatic staff. See U.S. Department of State, “Diplomatic Dictionary,” available at <http://diplomacy. state.gov/discoverdiplomacy/>. For the purpose of this report, the term “chancery” will be used to refer to the 1961 building and the term “embassy compound” or simply “embassy” will be used to refer to the buildings, including the chancery, the New Office Annex, the Marine Corps Security Guard quarters, and other structures on the site, and its surrounding landscape.

19. Loeffler, Architecture of Diplomacy, 57.

20. Ibid., 117.

21. Ron Robin, Enclaves of America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 137.

add prestige to the building program. A 1954 memo written by Pietro Belluschi during his term on the Architectural Advisory Committee included the names of nearly fifty prospective architects for FBO commissions. The list included prominent Modern-era architects such as Marcel Breuer, Charles M. Goodman, Walter Gropius, Louis Kahn, William Lescaze, Richard Neutra, Paul Rudolph, and Edward Durell Stone, among others. For architects, FBO projects were highly sought after. They were a means to showcase modern architecture and increase their professional recognition on a global scale.

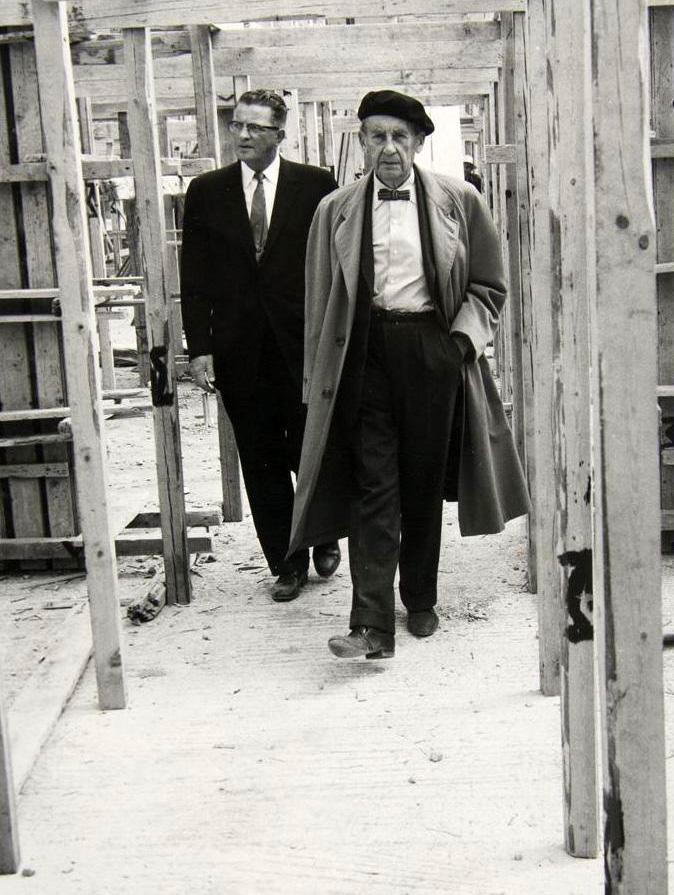

The Athens chancery project was awarded to Walter Gropius and his partners at The Architects Collaborative (TAC) in 1956. At the time, Gropius possessed a well-established international reputation as an academic and theorist as well as a practicing architect, and he was widely recognized by the architectural community as an important leader in the field. Gropius and TAC received the State Department contract during a high point in the FBO building program in terms of total work under construction and under review. The Architectural Advisory Committee met twelve times in 1956 and reviewed plans for fifteen projects, including Athens.22 Typically, architects selected for FBO projects were given an extensive debriefing by the FBO staff and the advisory committee and then sent to visit their assigned sites. The architects were expected to present preliminary designs and a final scheme incorporating suggested amendments made by the advisory committee.23 In the spring of 1956, the FBO provided Gropius with a preliminary program for the building and gave him authorization to travel to Athens to inspect the site and confer with interested parties.

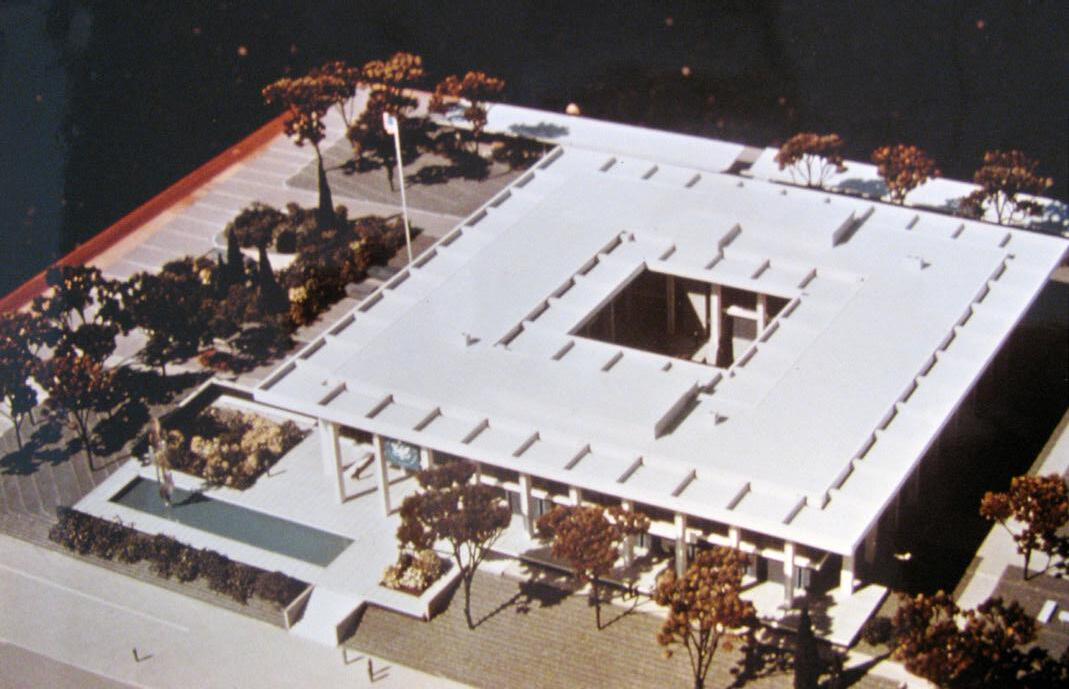

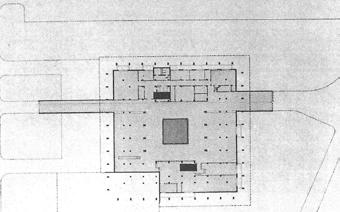

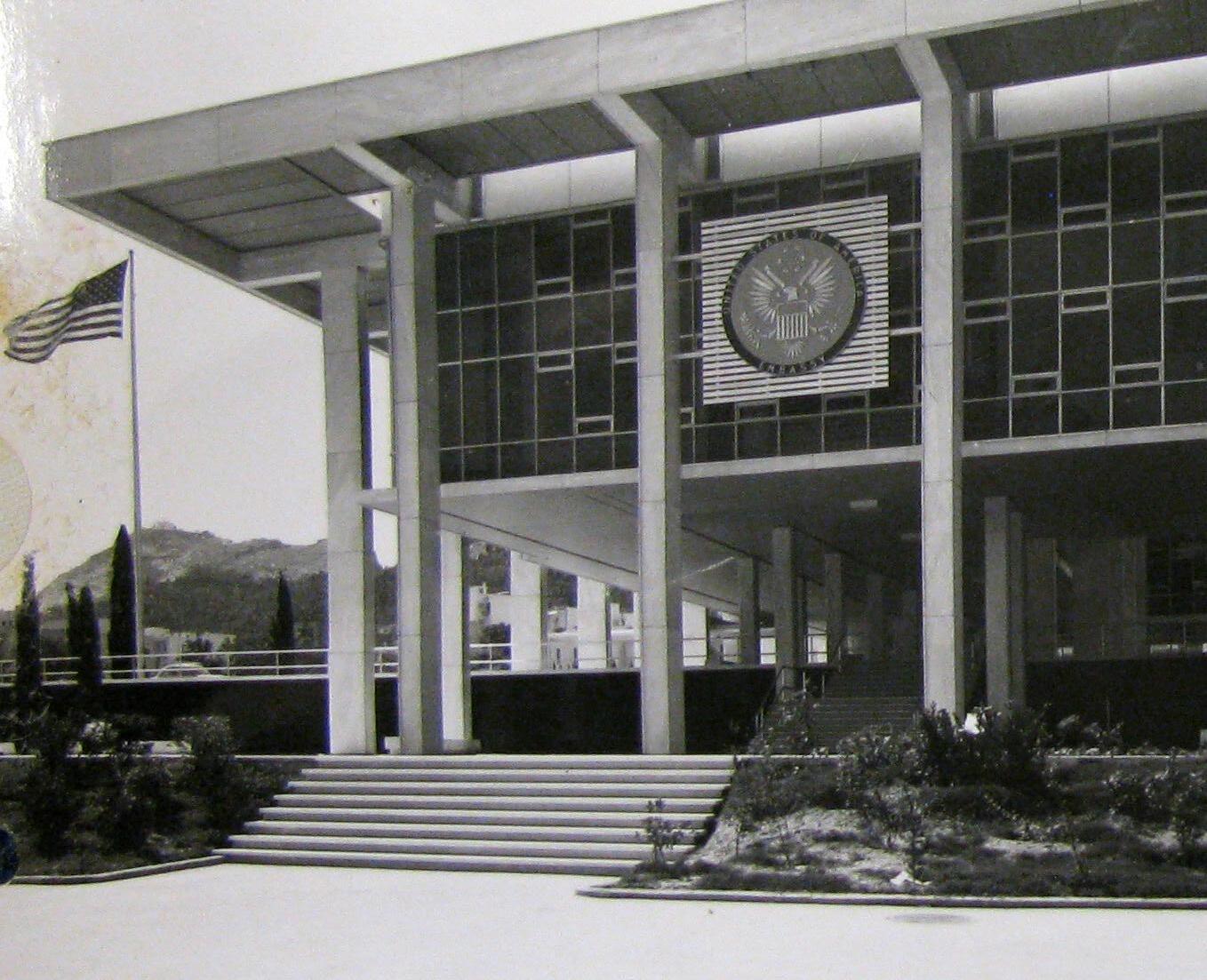

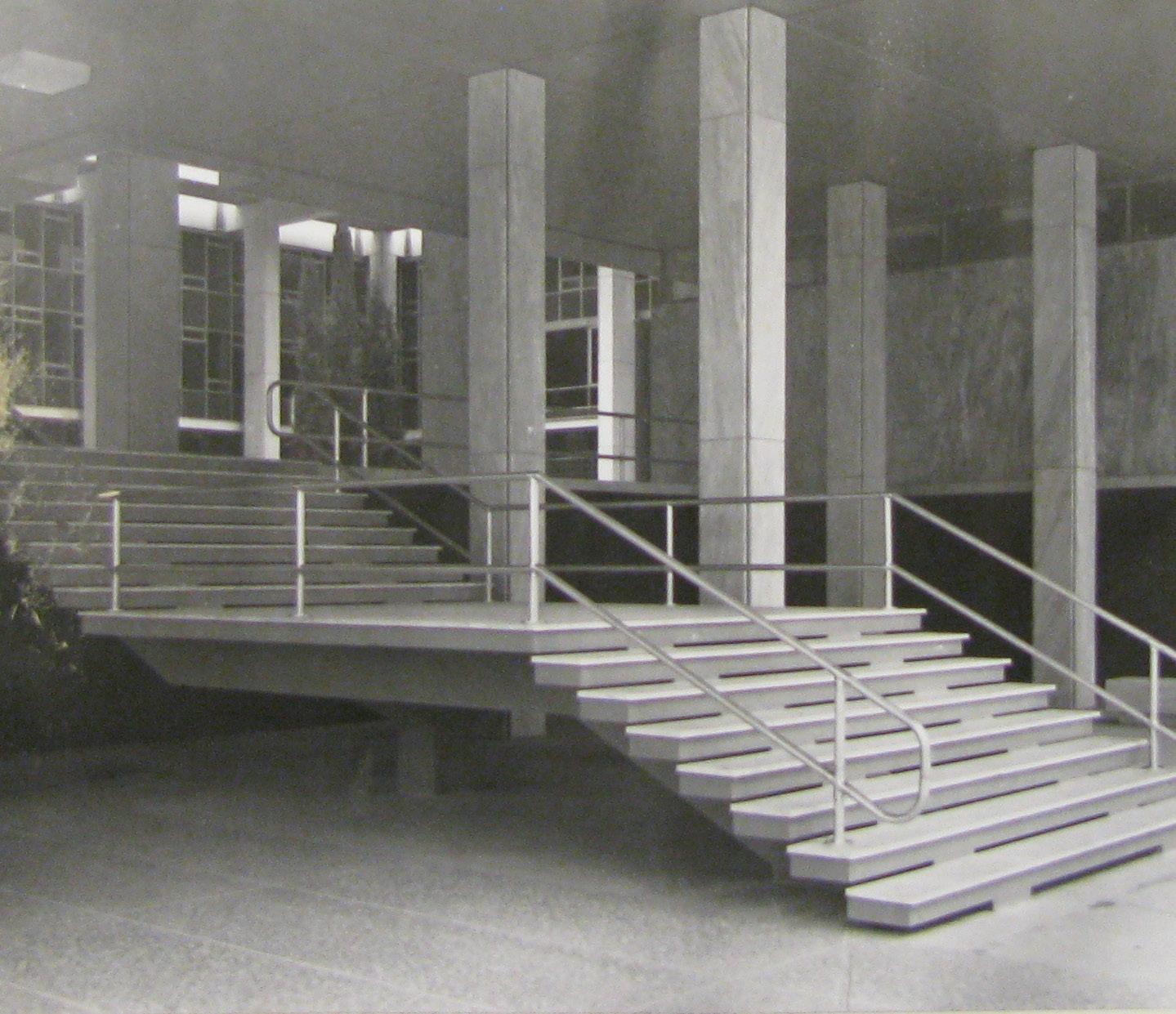

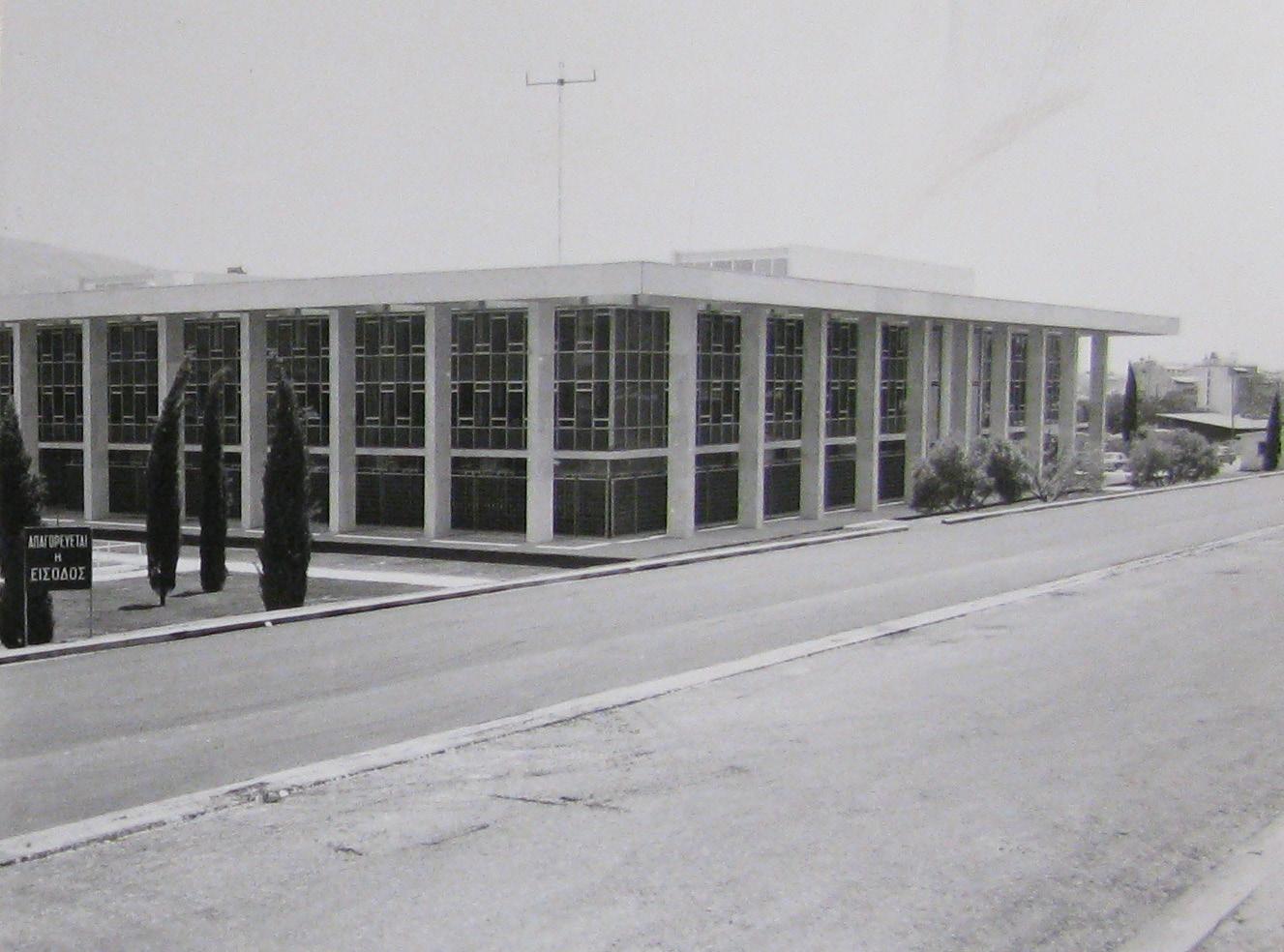

Gropius’s final design for the Athens embassy was a three-story building with a square plan and an open central courtyard (see Figures 7 and 8). The structure consisted of a reinforced-concrete frame clad in white Pentelic marble. It featured a flat roof with deep eaves. The roof was carried by slender peripteral columns that were rectangular in section and located around the exterior and courtyard elevations. The two upper floors of the building were wrapped in glazed curtain walls that were supported on floor slabs hung from interior hangers. The hangers were formed from steel angles joined together and encased in concrete. The ground floor, which also featured glazed curtain walls, was set back slightly from the upper levels and was partially open on the southeast and southwest elevations. Site features included a lower terrace with marble benches, planted beds, and a reflecting pool; an upper terrace with terrazzo paving; and a landscaped central courtyard. Around the perimeter of the ground-floor facade, glazed ceramic screens shaded and protected the exterior glass walls.

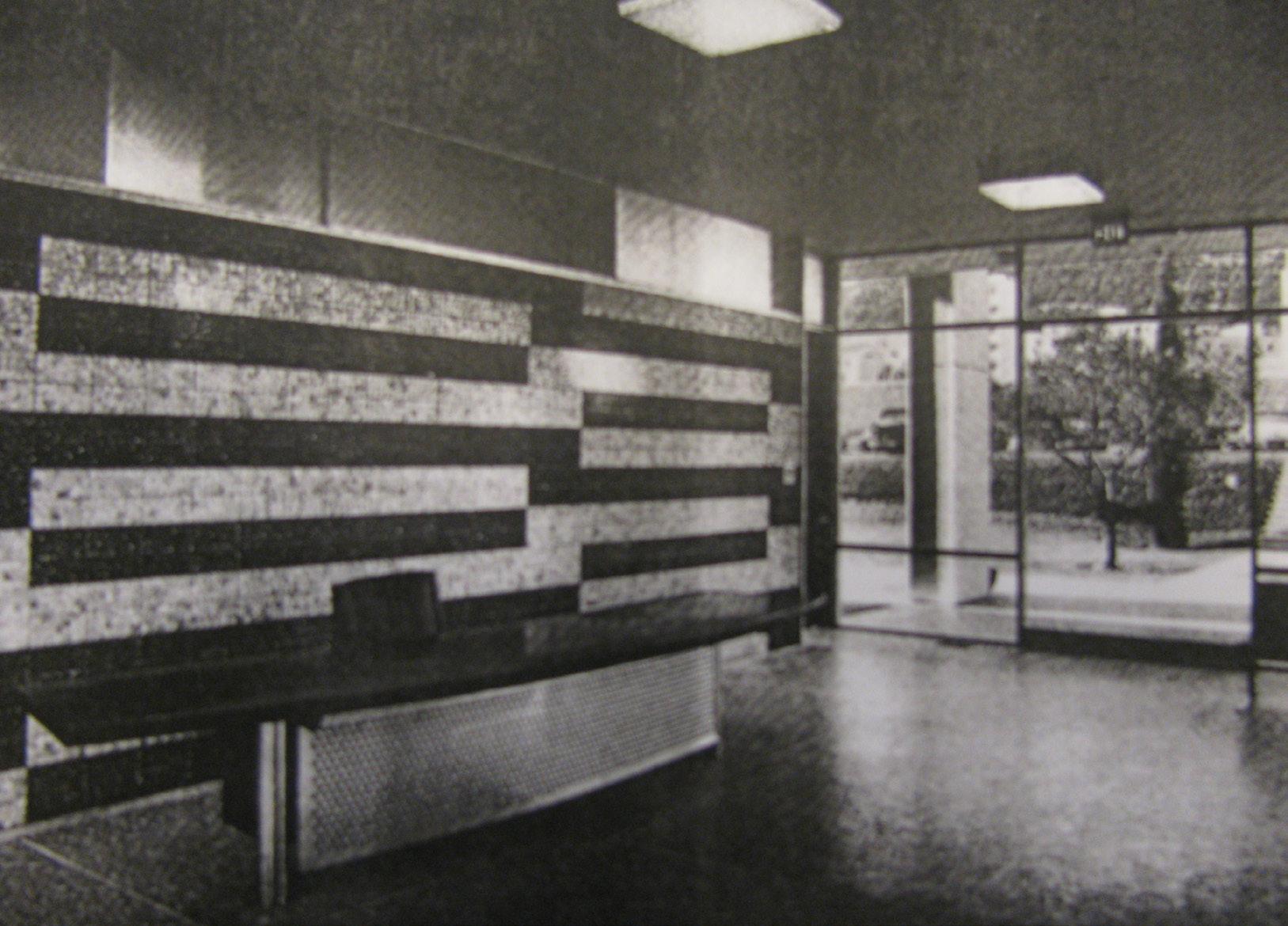

On the interior, the main lobby featured terrazzo flooring, marble-paneled walls, mirrored columns, and a Gropius-designed reception desk and mosaic wall panel. A second ground-floor lobby featured terrazzo flooring and provided a separate entrance for the consular services. The floor plans featured modular office space organized around doubleloaded corridors. Vertical circulation was provided by elevators and stairwells that featured marble-tiled walls, marble stair treads, and turned pear wood handrails. Special-purpose rooms included the ambassador’s suite, a conference room, and a classroom teaching area. The basement featured a cafeteria, kitchen, and underground parking. Today,

the building could be characterized as a highly skillful interpretation of Formalism — a Modern-era style typically featuring flat projecting rooflines, smooth wall surfaces, high-quality materials, columnar supports, and strict symmetry.24

The concept of contextualism was a significant focus of the architecture being designed by Gropius and his partners at the time. They defined the concept as: “A sensitivity and respect for the land, the place, the people, the climate from which design determinants are drawn…the work takes roots in its place, materials and form. It is remarkably free of preconceived design ideas and always responsive to local conditions.”25 Gropius was afforded the opportunity to explore the spiritus loci of Athens during a preliminary site visit in early May 1956. While there, he visited the Parthenon and wrote: “The building is translucent, it soars. Every detail seems easy and simple. There is clarity of thought and architectural action. There is no petty detail, no change of material, no effort for effort’s sake. There is no monumentality in its worst sense. The architecture is joyful.”26 He added: “If a restatement of this tradition could be made, it will come from a completely contemporary building in the best possible way and technique…Our contemporary architecture must be joyful and not severe — must be simple and yet subtle, and so on. This is a tremendous challenge.”27 Gropius developed his thinking into a single distinct concept, designing the chancery to embody “dignified simplicity.”28

The contextual approach practiced by Gropius and his partners at TAC and applied to the design of the chancery aligned with the FBO’s mandate that the architectural style of American buildings overseas express a sense of regionalism by harmonizing with

24. The General Services Administration (GSA) study Growth, Efficiency and Modernism: GSA Buildings of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s identifies four commonly accepted styles of the Modern era – the International Style, Formalism, Brutalism, and Expressionism. See Robinson & Associates, Inc., Growth, Efficiency, and Modernism: GSA Buildings of the 1950s, 60, and 70s (Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Services Administration, Office of the Chief Architect, Center for Historic Buildings, 2003), 14-15.

their built environment. The design featured a clear structural expression defined by a single row of peripteral columns that referenced the classical tradition of ancient Greek temple structures. It also employed features that are typically, but not exclusively, Greek — the podium, a quadrilateral plan, an interior courtyard, and exterior columns. Perhaps the most obvious association with local architecture was the extensive use of marble. The exterior used several types of local marble. Honed white Pentelic marble was used for all exterior columns, the visible parts of the horizontal roof beams, the roof cornice, the horizontal shelf under curtain wall, and the balconies. Pentelic marble is quarried from a mountain range northeast of Athens, and it was used for the construction of the Acropolis and other buildings of ancient Athens. White Santa Marina marble was used for the unglazed sections of the exterior ground-floor walls, for the exterior walls of the staircase and bathroom blocks, for the interior walls of the main lobby, for two interior walls of the stairwells, for all interior and exterior stair treads, for the main entrance path from Vasilissis Sofias Avenue, for the edges and dividing strips of the terrace paving, and for the exterior benches located throughout the site. Gray Marathon marble was used for two interior walls of the stairwells and for the lining of the large reflecting pool and the circular pool (the original marble lining of both pools is no longer extant). Marathon marble was specified for the visible basement walls, or podium, and for various exterior cheek walls, but black St. Peter marble was installed in its place.

In addition to meeting the FBO’s stylistic requirements, Gropius’s design had to satisfy certain performance demands that were dictated by the

25. Walter Gropius et al., The Architects Collaborative, 1945-1965 (Teufen, Switzerland: Arthur Niggli, Ltd, 1966), 8-9.

26. Untitled document, May 4, 1956, TAC Archives.

27. Ibid.

28. Memorandum “Embassy Building, Athens,” June 27, 1956, TAC Archives. This document may have been part of the presentation materials prepared by TAC for the FBO meeting that occurred two days later on June 29, 1956.

building’s location and function. Due to local climate conditions, the building had to be designed to protect against glare, sun, and heat.29 Gropius’s solutions included a cantilevered “umbrella” roof to keep the sun off the walls of the upper floors. The roof featured a double-layered system to keep direct heat off the uppermost floor and open slots to allow for the circulation of hot air. Other climate controls included interior blinds to block the light entering through the glazed curtain walls, gray glare-reducing glass for the fenestration, and the liberal use of landscape materials to create a green carpet around the building and an “oasis of relief in the city.”30 Exterior ceramic screens provided additional sun relief at the ground floor, which was not shaded by the roof overhang. The perforated screens were glazed a “sky blue” color, but only on the exterior edges to avoid sun glare reflecting into the interior. Lastly, the building featured an air-conditioning system. (Although air conditioning was originally specified only for the ambassador’s suite, the system was later upgraded to serve the entire building.)

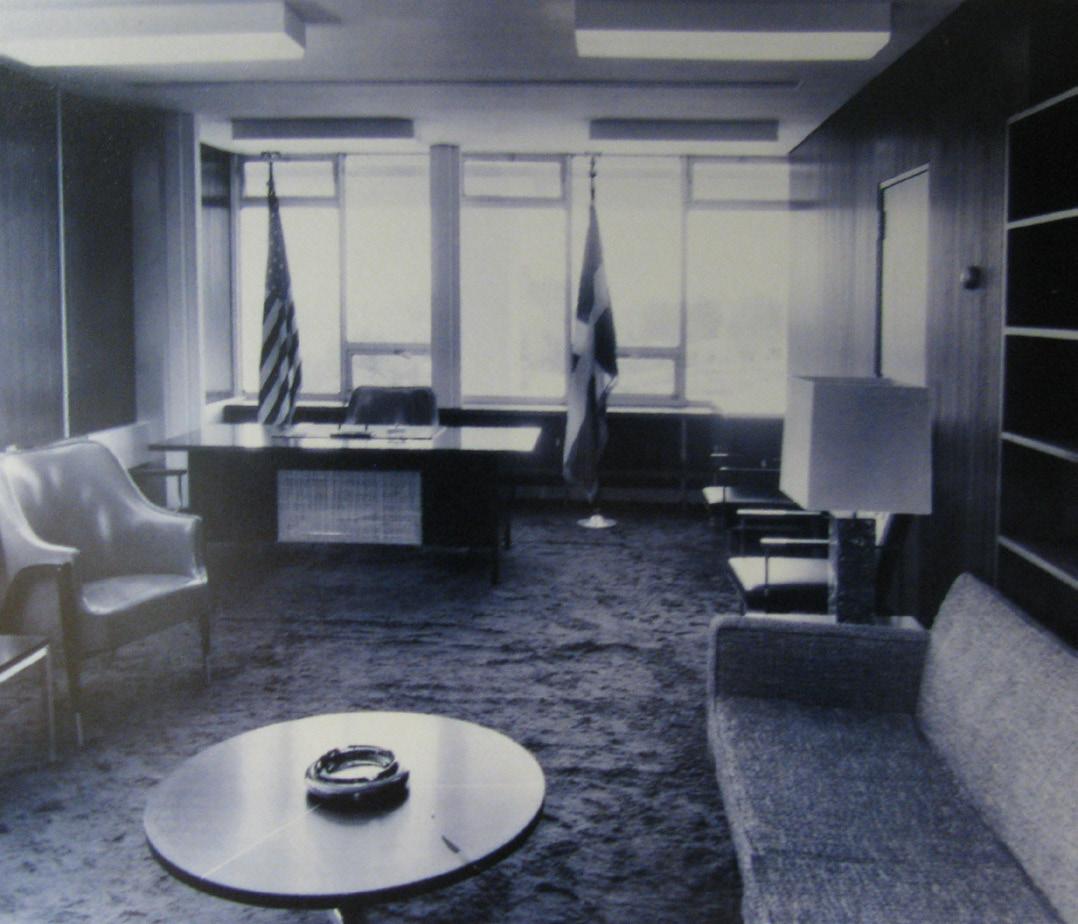

Due to its function as a U.S. chancery, the building had to be designed to provide efficient and flexible office space for both consular and diplomatic operations while conveying a sense of formality appropriate for hosting dignitaries and other ceremonial activities. Gropius designed a highly functional ground-floor space for the consular service that included its own entry point and public lobby. Diplomatic operations were assigned to the upper floors and accessed by a separate ground-floor lobby that had convenient pedestrian and vehicular access.

On all the office floors, Gropius designed doubleloaded corridors and modular work spaces where

29. Memorandum “Embassy Building, Athens,” June 27, 1956, TAC Archives.

30. Notes for Presentation of Athens Embassy Office Building, June 4, 1957, TAC Archives.

31. The metal fence was not on as-built drawings and was never realized. In the early 1980s, as part of the construction of the pavilion in the upper terrace and renovations to the consular section, various plans were drawn up to enclose or partially enclose the courtyard space with a screened corridor and later a fence. These enclosures were also never realized. See text under 2.2 Additions and Alterations for additional information.

door and window openings were laid out to allow for maximum freedom and flexibility in subdividing offices. Public lobbies, the ambassador’s suite, and special purpose rooms featured distinctive finishes such as marble tiles and wood paneling. As a chancery, the building also had to be designed to protect against burglary. The exterior ceramic screens Gropius installed around the building perimeter to provide sun relief also protected the ground-floor curtain wall. (Early drawings included a metal security fence at the open southwest and southeast sections of the upper terrace, but this was never realized.31)

Gropius established his design team shortly after contracting with the State Department. From the TAC offices, contributors included partner Norman Fletcher and architect H. Morse Payne. The mechanical and electrical engineers were General Engineering Associates of Washington, D.C. The structural engineer was Paul Weidlinger of New York with associate Mario Salvadori. The engineer in charge of design was Antranig M. Ouzoonian. Bolt, Beranek and Newman, Inc., of Cambridge, Massachusetts was the acoustical engineer. Pericles Sakellarios served as the local consulting architect in Athens (see text below).

Paul Weidlinger, a Hungarian immigrant who studied under both Moholy-Nagy and Le Corbusier, opened his firm (now Weidlinger Associates) in 1949. Weidlinger developed a reputation as an innovative designer, and, over the course of his career, worked with many important architects of the Modern era including Gordon Bunshaft, Marcel Breuer, and Eero Saarinen. Associate engineer on the Athens project, Mario Salvadori, became a leading educator in the field of engineering.

On June 29, 1956, TAC made its first presentation to the FBO and the Architectural Advisory Committee. Later that year, the State Department commissioned an architectural model of the chancery (see Figure 7). The TAC team presented a refined design to the FBO and its advisors in June 1957. The following passages, extracted from TAC notes from that presentation, provide insight into the final design:

Landscape materials should be used liberally to create a green carpet as an oasis of relief in a city which is principally stone.

While traditional materials are used extensively, the building must also meet contemporary standards of office building design. Materials not available in Greece will be imported principally from other European countries. Since all steel must be imported, the structure is designed in reinforced concrete to use less steel more efficiently. Aluminum is preferred for the curtain wall frames for its color and ease of maintenance. Gray glare-reducing glass has been chosen for the fenestration, maximizing contrast with the Pentellic [sic] marble sheathed elements.

The Embassy is conceived as an inviting building, free of forbidding walls and fortress-like enclosures.

A development in depth of the facade was desired to achieve an interplay of shadow and sunlight… Suspended shields, entrance canopies, and balconies further develop his basic principle of interplay in depth, with their projections and recesses. Finally, to emphasize the suspended character of the upper two stories of offices, the ground floor elements occur as islands which rise from the ground, recessed from the upper building face.32

34. Gerd Hatje, ed., Encyclopedia of Modern Architecture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1964), 140.

Gropius made another trip to Athens in July 1957, and a building permit was issued to the U.S. government by the city of Athens on September 12, 1957.33 Later that year, the design was widely publicized in professional journals with articles that included reproductions of the architectural plans and photographs of the model.

Gropius’s final design for the Athens Chancery reflected monumental classical traditions while exemplifying many themes and design characteristics of Modern architecture. Modernism embraced new technologies, new methods of construction, and the intelligent application of standardization and prefabrication. In designing the chancery, Gropius and his consultants provided an innovative structural system in which the upper floors were suspended from concrete girders. By eliminating load-bearing walls and employing a curtain-wall system, Gropius was able to create a strong sense of openness and transparency at the ground-floor level.

The curtain wall was a quintessential symbol of Modern architecture. One of the first examples of this innovative structural system was Gropius’s Fagus Shoe Factory (1911-13) in Alfeld-an-der-Leine, Germany.34 Gropius also famously designed a glazed curtain wall for the Bauhaus in Dessau. Due to the prevalence of glazed curtain walls, Modern-era buildings also typically featured brise-soleils or other types of screens to prevent the sun from directly hitting the curtain walls. Gropius used prefabricated ceramic screens at the chancery for solar control. Modernist buildings used traditional materials in innovative ways. Masonry, for example, was separated from the load-bearing function and used in applications such as thin stone veneers. This technique was adopted for the chancery

design, where marble cladding was used to convey the same sense of permanency as traditionally constructed stone buildings such as the Parthenon. Modernism also embraced the principal of functionalism, a concept evident in Gropius’s design for the chancery. The building’s structure and other practical considerations determined its form, and the design was almost entirely free of ornamentation and embellishment.

Gropius’s design for the chancery also demonstrated common themes of Modern-era landscape design. The period emphasized the integration of outdoor and indoor space which Gropius accomplished by carrying exterior materials such as the terrazzo flooring and marble cladding into the interior lobby spaces. The glazed walls and entryways at the lobby locations further emphasized the blending of space. Terraces were integrated into the site design to serve as gateways into the property and function as outdoor rooms. Modern-era landscapes also often employed asymmetrical spatial arrangements and three-dimensional volumes, which factored into Gropius’s designs for the lower terrace, the main entry sequence, the central courtyard, and the terrazzo patio at the consular entrance (see Figure 6).

Following the donation of the Vasilissis Sofias Avenue site to the United States in 1953, the Greek government cleared its temporary and semipermanent structures from the site. The following year, as a gesture of its intention to develop the site as planned, the FBO proposed some preliminary site improvements, including the construction of a wall around the lot.35 Additional clearing and excavation work by the building contractor began on December

35. Office Memorandum, June 14, 1954, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 9, RG 59, NARA. Although it is unknown if the wall around the chancery site was constructed by the U.S. as planned, a stone wall does appear in historic photographs of the unimproved site (see Figures 4-5).

36. Gropius to William P. Hughes, Director, Office of Foreign Buildings, January 28, 1959, TAC Archives.

37. Alexander J. Albertis, one of the principals of the A. Albertis & Th. Dimopoulos Engineering Company, studied engineering in the United States at the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign, graduating in 1932.

38. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, April 2, 1962, TAC Archives.

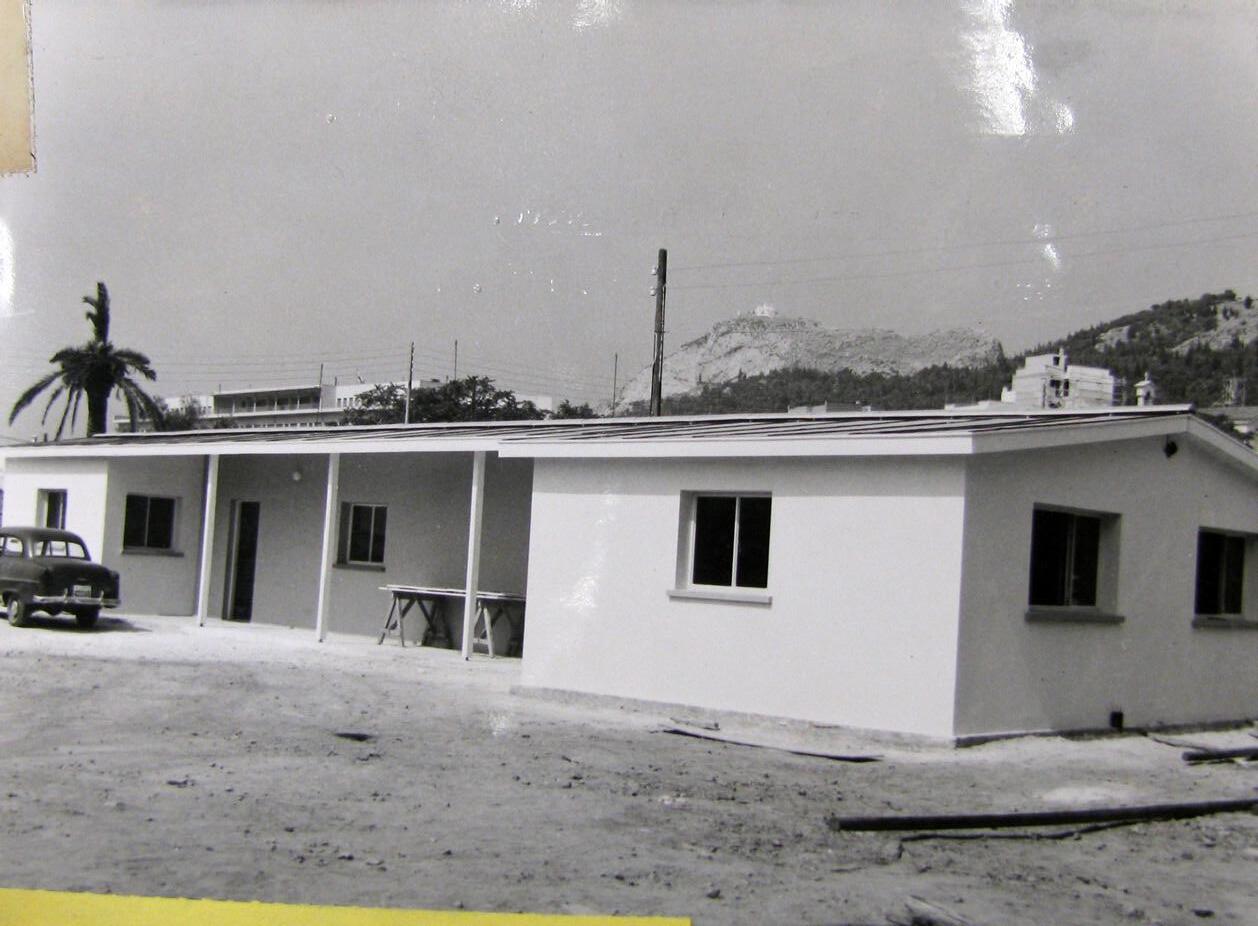

15, 1958.36 The contractor was A. Albertis & Th. Dimopoulos Engineering Company, an Athens firm that offered engineering, architectural, and contracting services.37 At the start of construction, a small contractor’s building (no longer extant) was built at the western corner of the site. When the chancery was complete, Gropius lobbied to have the building demolished, arguing that “it definitely does harm to the looks of the whole building.”38 Despite this, it remained on the site for decades (see Figure 9). It was used as a warehouse and, in the mid-1990s, converted into a small gymnasium.39 The building was eventually demolished in 2005 for the construction of the New Office Annex (see text below).40

In January 1959, Gropius corresponded with William P. Hughes, Director of the FBO, to state his support for the appointment of Pericles Sakellarios as architectural supervisor for the Athens project.41 Local architects were often hired to oversee FBO construction projects because they “knew the local conditions, understood building codes and other restrictions, knew authorities, were familiar with builders and their capabilities, and, generally speaking, could help FBO win local approval.”42

39. Memorandum “Technical Specifications for Gymnasium,” 1994 in the miscellaneous files of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens, Greece (hereafter cited as the miscellaneous files of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens).

40. The date of the demolition was provided by the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations, U.S. Department of State, on December 14, 2012.

41. Gropius to William P. Hughes, Director, Office of Foreign Buildings, January 28, 1959, TAC Archives.

42. Loeffler, Architecture of Diplomacy, 68.

Gropius already had an established relationship with Sakellarios, having consulted with him during the design phase and over the course of his site visit in 1956. A contract was finalized in March 1959, with Sakellarios agreeing to serve as architectural supervisor for a fee equivalent to 1.25% of the building cost, which was estimated at $1,120,000.43 At the time, Sakellarios had his offices not far from the construction site at 35 Vasilissis Sofias Avenue. Prior to Sakellarios’s involvement, the first five months of construction were managed by two American supervisors.44

As part of his role as architectural supervisor, Sakellarios provided monthly progress reports to the TAC office. These reports typically included a description of work completed, equipment used, materials delivered, and materials ordered. The report for July 1959 indicated that aluminum doors, folding gates, aluminum windows, vitreous panels, copper pipes, copper fittings, bathroom fixtures, and roofing felt were all ordered from various manufacturers in England. Transformers, switch and panel boards, a conductor, steel pipes, and ceramic screens were ordered from Germany. Insulation was imported from Holland. The only order placed for local materials in the month of July was for Greek marble.45 Some of these overseas manufacturers were specified by Gropius. For example, he ordered the ceramic screens from the Wilhelm Gail’sche Tonwerke, in Giessen, Germany, a company that he had communicated with during a previous project (see Figure 10).46

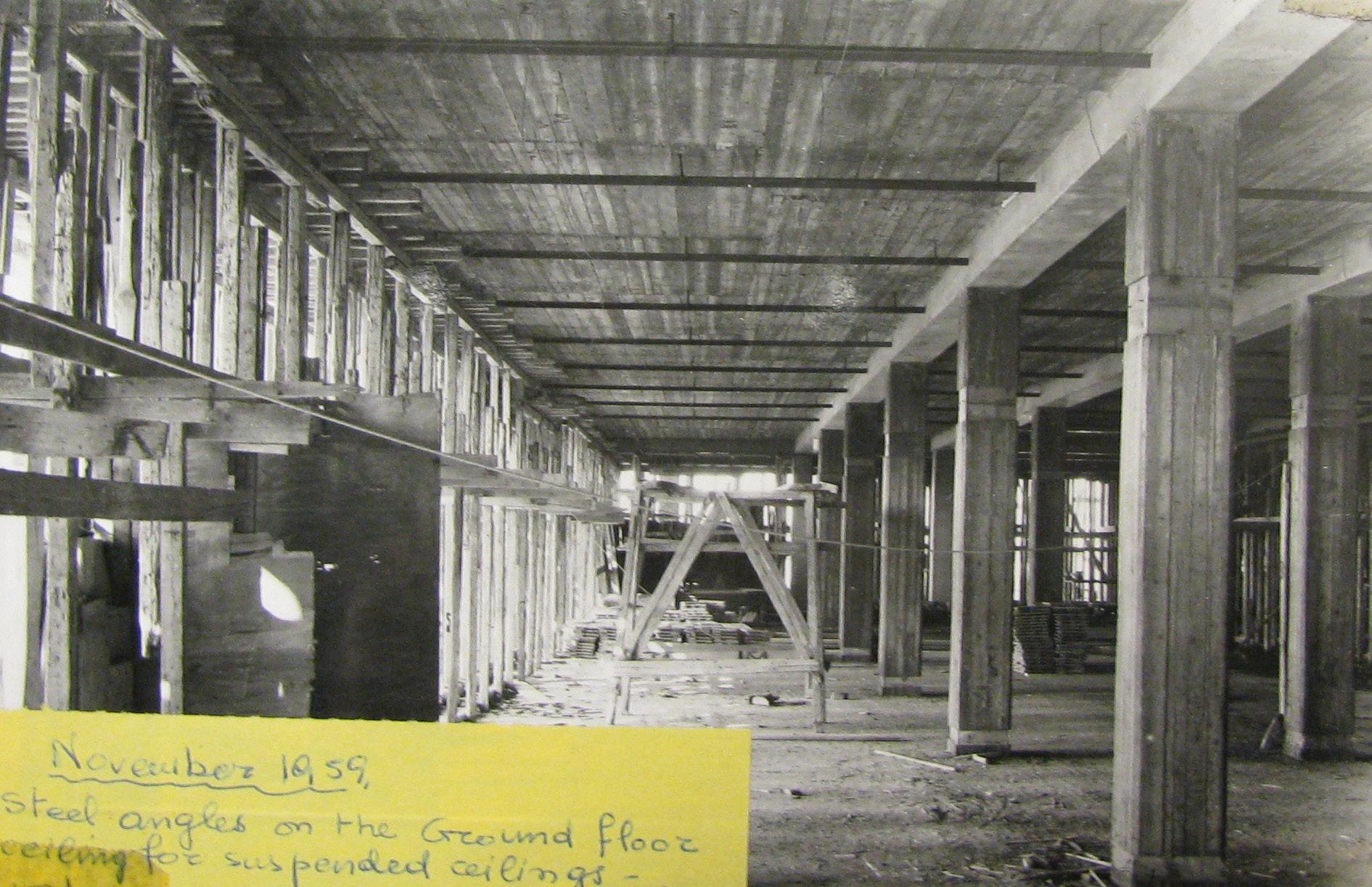

The building was constructed of poured-in-place reinforced concrete made with locally produced Portland cement. By August 1959, the basic work of

the Vasilissis Sofias Avenue entrance, including the planting beds and fountain pool, had been completed.47 That October, the interior columns, beams, and slabs of the first and second floors had been poured, and the third-floor formwork was complete (see Figures 11-13).

Design changes were requested by the FBO early in the construction process. When the need for gray glass in the curtain walls was questioned by State Department officials, FBO field supervisor Adolf K.N. Waterval championed Gropius’s original design writing: “One of the design features of this building is assumed by the Supervisor as having been predicated on an all glass exterior with white marble trim and columns. The columns being of such tremendous scale and surrounding the entire building were no doubt considered by the Architect to be the most outstanding element, thus he subdued his glass curtain walls on the three floors by specifying the special smoked glass, creating in a sense a dark facade behind the columns which would automatically emphasize the beauty of the massive marble columns.”48 He added: “Therefore the Architect provided the smoked glass to protect the occupants’ eyesight from the glare which would otherwise prevail if clear glass was to be used, thus not only providing a most effective design on the exterior, but also most utilitarian.”

Later, Gropius had to defend the use of a marble finish for the interior walls of the stairwells and lobbies. In a letter to the FBO Director, he wrote: “Also in several telephone calls with your Department, I stressed the point that this marble finish could not be taken out, that the walls in plaster only would definitely have a shabby appearance since the proportions going with

44. “Statements to Facilitate Inspection,” August 12, 1960, Foreign Service Inspection Reports, Box 10, RG 59, NARA.

45. “Progress Report for the Month of July 1959,” August 16, 1959, TAC Archives.

46. Gropius to Wilhelm Gail’sche Tonwerke A.G., Giessen, Germany, August 29, 1956, TAC Archives. Gropius had previously corresponded with this manufacturer during his work on an apartment block in the Hansa Quarter of Berlin, Germany.

the details of the stair flights proper have been carefully worked out. Without telling me anything, this item has, however, been omitted…I cannot approve of having such important omissions made without checking up with our office. This is a serious item which I beg you to reinstate. I cannot put my name on it. As you know it is always the Architect who is blamed for unwholesome results.”49 Gropius ultimately prevailed, and the marble finish was installed as designed (see Figure 14). Gropius was less successful with his appeal to the FBO to retain his original design for the reflecting pool in the lower terrace that included a sculpture by Harry Bertoia, the Modern-era sculptor and furniture designer. The sculpture was never installed in the pool; it was replaced with a single water jet. The FBO also made the early decision to upgrade the air-conditioning system for the chancery, calling for “complete air conditioning… instead of the presently designed heating and ventilation system combined with air conditioning of the Ambassador’s offices.”50

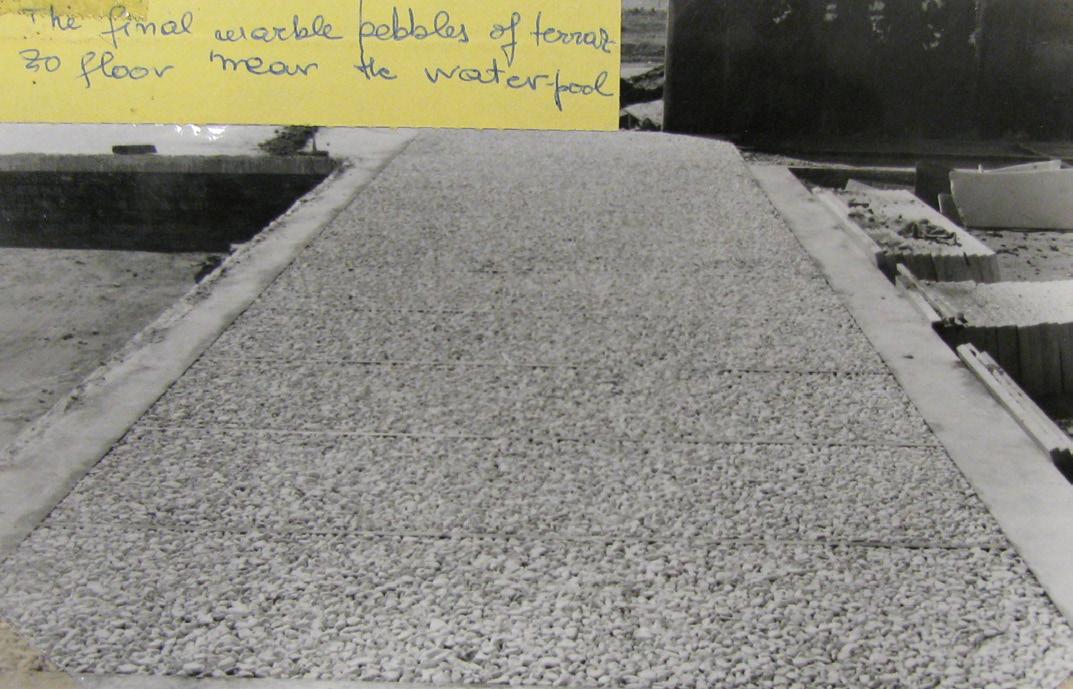

Gropius traveled to Greece for a site inspection in February 1960. By this time, construction of the concrete columns, girders, floor slabs, and roof were finished, and the contractors were beginning to install the marble sheathing on the exterior columns. A sample section of the glazed curtain wall was installed, and work had begun on the terrazzo paving of the lower terrace.

By April 1960, site work, including landscaping, was progressing. Cypress and olive trees and flowering shrubs were planted at various points around the lot, the terrazzo paving around the northeast and northwest sides of the building and around the lower terrace was finished except for the polishing, and

49. Gropius to William P. Hughes, Director, Office of Foreign Buildings, November 20, 1959, TAC Archives.

50. L. V. Del Favero, Assistant Director for Operations, Office of Foreign Buildings, to Gropius, September 1, 1959, TAC Archives.

51. Operations Memorandum from American Embassy, Athens, to U.S. Department of State, Foreign Buildings Office, April 5, 1960, TAC Archives.

52. Gropius to L.V. Del Favero, Assistant Director for Operations, Office of Foreign Buildings, August 9, 1960, TAC Archives.

the marble benches at the consular entrance were installed. On the ground floor, the ceramic screens were installed on the northeast and southeast elevations and the flat slab reinforced concrete entrance canopy was placed at the southwest entrance. On the upper floors, the vertical and horizontal members of the window frames were installed on the southeast and southwest sides of the building, the sashes of the staircase windows were installed, and the steel frames for the dropped ceilings were in place (see Figures 15-20).51

Throughout construction Gropius struggled with the FBO over design decisions related to interior finishes, paint colors, and furnishings. He wanted control of the building and site in its totality, writing: “…the unity of design of the whole job imposes the necessity of coordinating the interior with the exterior.”52 Of primary interest were the main lobby, the consular lobby, the waiting areas at the elevators on the second and third floors, the second-floor classroom teaching area, and the ambassador’s suite. He also wanted input into the “typical office furniture arrangement.” The FBO, however, had its own interior designers who often had to work within limited parameters. For example, whenever possible the FBO tried to use furniture manufactured overseas to avoid the expense associated with shipping American-made goods. Often, pieces were made abroad from contemporary designs purchased from American manufacturers. At the time of the Athens project, the FBO’s Chief Interior Designer was Anita J. Moller, who proposed to furnish the chancery using pieces made by Saridis Furniture Manufacturers, a local Athens company, from designs by the Dunbar Furniture Corporation of Berne, Indiana.53 Moller selected Dunbar for its “attractive contemporary

53. Dunbar’s director of design at the time was Edward J. Wormley (1907-1995), who is today considered one of the major designers of American modernist furniture. See Cornell University Library, “Guide to the Edward J Wormley and Edward Crouse Papers, 1831-1997,” available on the Internet at <http://rmc.library. cornell.edu/ead/htmldocs/RMM07684.html>.

furniture.”54 Gropius disagreed with this arrangement stating: “I have one great doubt however that the pieces of furniture from Dunbar fit the architecture of the building. Only very few pieces of that firm are, in my opinion, up to the quality of design fitting the building, and I ask permission to look for other suggestions as well.”55 The only concession the FBO made regarding this issue was for the lobby furniture. Gropius designed a reception desk and mosaic wall panel for the main lobby and specified four chairs and two glass tables manufactured by the Albano Company (see Figure 21).56

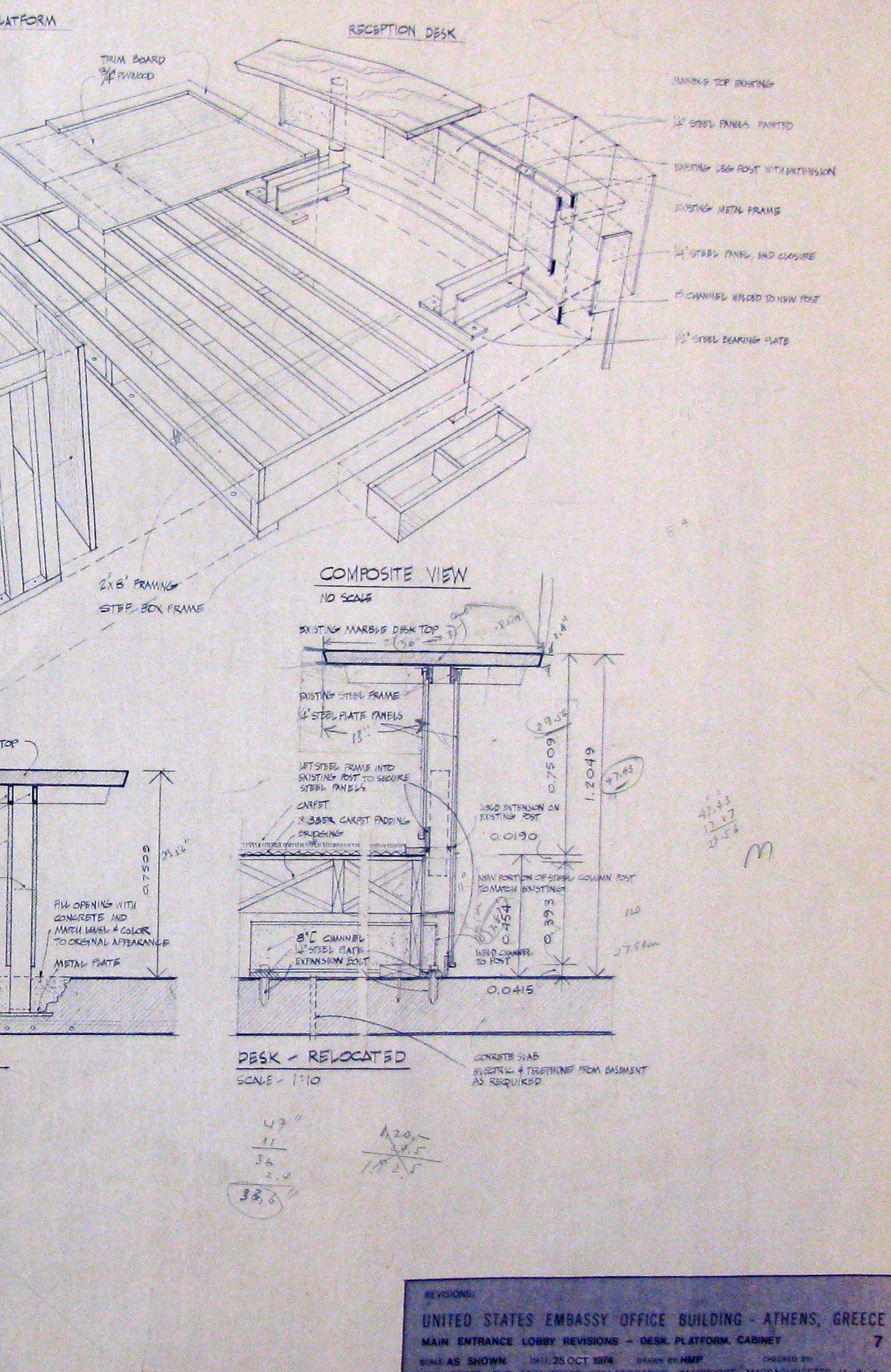

The reception desk designed by Gropius (no longer extant) had a slightly curved top supported by a hollow steel frame. The front of the desk featured a perforated aluminum screen that concealed a set of drawers and a typewriter cabinet. Originally, Gropius designed the desk with a black marble top. Later, black terrazzo was substituted for the marble.57 The terrazzo was made in Greece, and the aluminum screen was fabricated and shipped from New York. It was constructed by Saridis Furniture Manufacturers. The reception desk was originally positioned in front of a black and white marble mosaic wall panel also designed by Gropius. The wall panel featured a bold geometric pattern composed of black and white horizontal bands. It was manufactured by Fulget and imported from Bergamo, Italy.

Gropius identified paint colors for the office floors that were “selected in such a way that they fit the furnishing, carpeting, and vertical blinds.”58 In August 1960, his specifications stated: “All partition walls in all three stories running vertical to the windows should be gray, No. W4. All the walls opposite the windows should get a pale color — cool colors blue

54. Anita J. Moller to Gropius, March 25, 1960, TAC Archives.

55. Gropius to L.V. Del Favero, Assistant Director for Operations, Office of Foreign Buildings, August 9, 1960, TAC Archives.

56. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, August 30, 1960, TAC Archives.

57. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, March 13, 1961, TAC Archives.

58. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, August 30, 1960, TAC Archives.

59. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, August 30, 1960, TAC Archives.

60. As part of the preliminary evaluations undertaken for the preparation of this report, paint samples were removed from key

No. W7, or green No. W5 — towards the sunny side south and west; warm colors pale buff No. W6, and pale pink No. W8, towards north and east.”59 The FBO, however, argued for a simple color scheme that would be easy to maintain. Although the final paint scheme is unknown, it is most likely that neutral colors, grays and off-white, were substituted for the pastel palette requested by Gropius.60 A few special-purpose rooms including the ambassador’s office, the counsellor’s room, and the conference room received stained oak “Alimil” paneling rather than a painted finish.61

Gropius specified vertical window blinds throughout the building to shade interior office spaces from sunlight and glare. He chose a pale orange color fabric blind, writing: “As all the materials of the building from outside, the white marble, the aluminum frames, and the gray glass, have a cool effect, the blinds must have a warm tint as contrast for exterior, as well as interior effect.”62 The blinds were manufactured by Vertical Blinds Corporation of California. For the flooring, gray and black linoleum tiles were specified for the office corridors. Gropius provided detailed instruction for their installation, writing: “Please note that the grain of the gray linoleum should always run perpendicular to the window; whereas the grain of the black linoleum should run parallel to the window.”63 In the ambassador’s office, the counsellor’s room, and the conference room Gropius specified “mottled green” carpeting. The ground-floor lobby spaces had terrazzo flooring with marble divider strips.

During construction, white Santa Marina marble panels were installed around the building podium rather than the gray Marathon marble specified in

interior spaces. Future analysis of these samples may provide insight into the original paint scheme used in the chancery. See U.S Chancery, Athens, Historic Structure Report and Building Conditions Assessment, Volume 2.

61. The wood paneling was manufactured in Germany by Alimil-Holzwerk. See Gropius to Adolf K.N. Waterval, Foreign Buildings Officer, American Embassy, Greece, October 5, 1960, TAC Archives.

62. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, October 7, 1960, TAC Archives.

63. Gropius to Adolf K.N. Waterval, Foreign Building Officer, American Embassy, Greece, September 8, 1960, TAC Archives.

the drawings. After the mistake was realized, the Santa Marina marble was taken down. Due to the difficulty in finding enough available Marathon marble of a uniform color, it was substituted with black St. Peter marble and black Vytina marble. (Before the building was finished, the black marble had begun to crack and fade. Despite various methods of repair and remediation, including polishing it monthly to lessen the discoloration, a satisfactory solution was not identified.)

The curtain wall was constructed using a system manufactured by Williams & Williams Products Corporation of New York. This system featured “Wallspan” curtain walls comprised of “extruded aluminum hollow box-form mullions and transoms with extruded aluminum head and cill [sic] members” and spandrel panels fabricated of 1-inch thick “Vitroslab,” which was described as vitreous enamel panels backed by aluminum.64 Shortly after installation, cracks appeared in the spandrels panels (see Figure 22). By the spring of 1962, Sakellarios reported that the number of cracked panels on the southeast and southwest facades had increased from 34 to 37.65 At the time, one explanation for the defect was that the panels had not been properly heattreated and were cracking due to extreme temperature changes.66 Later, 40 replacement panels were shipped to Athens from the manufacturer.

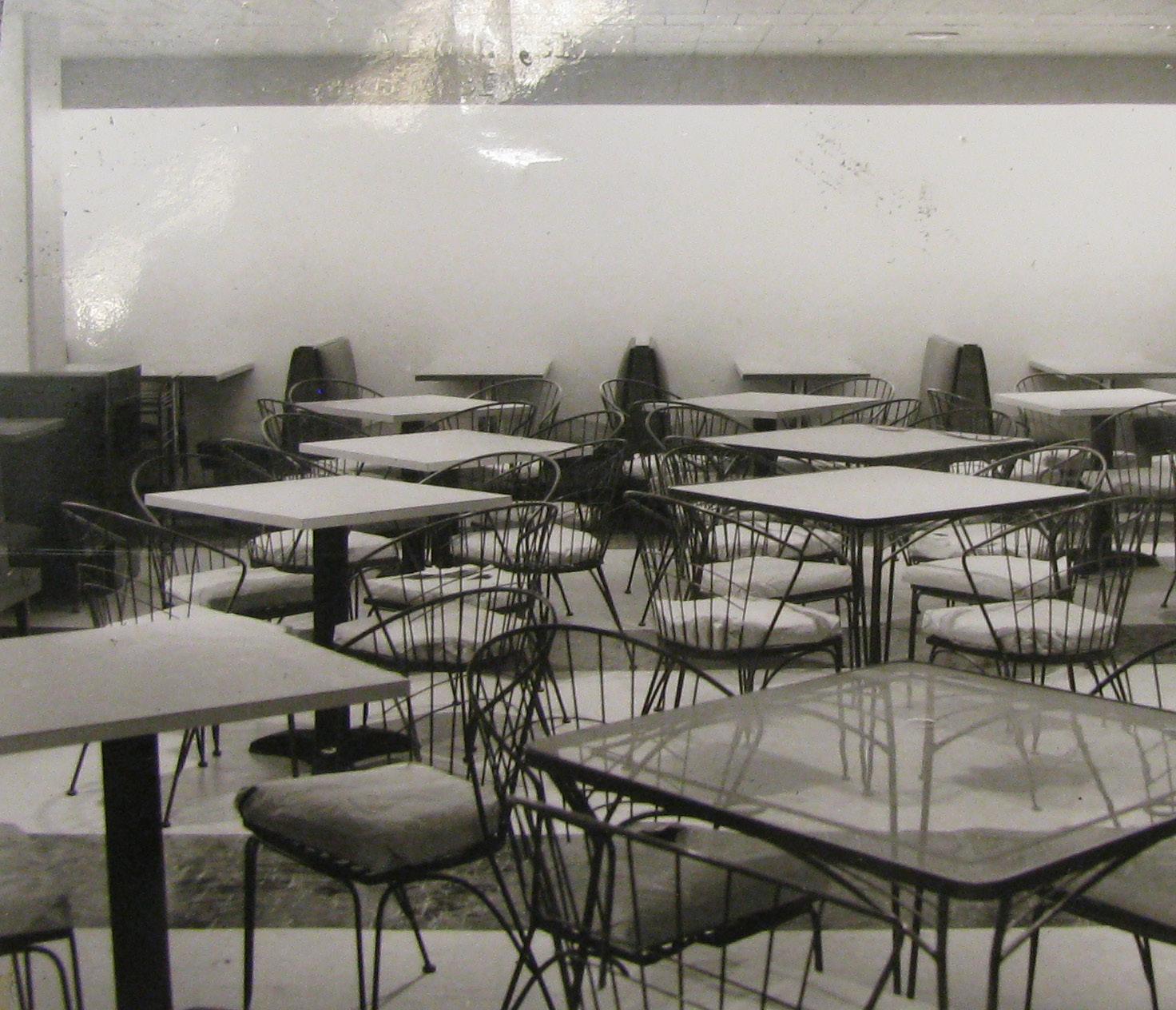

One of the last spaces to be finished in the chancery was the cafeteria and kitchen area in the basement. Early in the design process, Gropius proposed locating a “snack bar” on the roof of the chancery. This was rejected by the FBO, and Gropius revised his plans to place the snack bar in the northeast corridor of the second floor, overlooking the courtyard.67 By July 1960, however, the decision was made to move the snack bar to the basement and reallocate the second-floor space as a classroom teaching area.68 Ultimately, the basement snack bar was upgraded into a full kitchen and dining area/cafeteria. When it was completed in late 1961, the cafeteria featured booths and tables, a service island, and telephone booth. Wall finishes included plaster, ceramic tiles, and “Alimil” wood paneling (see Figure 23). The floor was surfaced with linoleum tiles.

64. A.M.P. Scott, Williams & Williams Products Corp., New York, NY, to Gropius, March 7, 1957, TAC Archives.

65. Sakellarios to Gropius, March 22, 1962, TAC Archives.

66. Memorandum from Lester H. Dinsmore, Supervising Architectural Engineer, Office of Foreign Buildings, to Bernard C. Hibler, Athens, March 28, 1961, TAC Archives.

67. Memorandum “Changes for the Athens Embassy Building According to the Washington Meeting of June 29, 1956,” June 1956, TAC Archives.

68. H. Morse Payne, TAC, to L.V. Del Favero, Assistant Director for Operations, Office of Foreign Buildings, July 25, 1960, TAC Archives.

The building was occupied on July 1, 1961. On the Fourth of July holiday, the chancery hosted a “preview” for Americans living in Athens that was attended by nearly four thousand visitors.69 The photographs on the following pages illustrate the as-built condition of the embassy compound.

Figure 35

View of main lobby, looking northwest, July 8, 1961. The main lobby featured terrazzo flooring, white Santa Marina marble paneled walls, a glazed exterior wall, glass doors, a reception desk designed by Gropius, and mirrored columns. Excluding the reception desk, the lobby furniture — four chairs and two glass tables — were manufactured by the Albano Company.

Figure 36

View of main lobby looking west, date unknown. The original reception desk and the black and white marble mosaic wall panel were customdesigned by Gropius. (Photo from The Walter Gropius Archive, Vol. 4)

Figure 39

Typical office, date unknown. Typical offices featured plaster walls, linoleum tile floors, and overhead lights. The curtain wall had fixed glass and operable hopper windows. Gropius’s window-washing system for the exterior and courtyard curtain walls (shown at right) consisted of ladders built of aluminum tubing, carrying wheels, and steel tracks and guide channels that attached to the building facade.

Figure 40

Office corridor, location unknown, July 8, 1961. The office corridors had “undulating,” or pitched, plaster ceilings, linoleum floors, and wall-mounted lights. The corridors were divided in places by louvered aluminum doors with glass transoms and sidelights. Typical office doors were painted wood, with kick plates where required.

from other office

in several ways. The interior had a wider floor plan that resulted in extra space between the hangers (on the left) and the exterior wall. Folding screens allowed for flexible use of the interior space. On the exterior, the classroom area projected out into the courtyard and had a different glazing pattern than the rest of the curtain wall (see Figure 33). The top of the projection on the exterior was covered in metal flashing, and the side walls were covered in corrugated aluminum panels.

date

Note the hangars and the original light fixtures. On all four facades of both the second and third floors, one corner of the curtain wall had opaque panels, visible on the far left of this photo.

The chancery has continuously functioned as America’s primary diplomatic and consular facility in Greece since it opened in July 1961. Over the past 51 years, under the responsible management of the State Department, both minor and major changes have been made to the original design. These alterations and additions are described below in roughly chronological order.

One of the earliest changes to the original design was approved by Gropius while he was still involved with the project. In October 1961, a memo was sent from the security officer at the chancery to the FBO requesting the installation of an aluminum railing along the southeast edge of the upper terrace. Gropius was consulted and suggested an alternative solution. Instead of a continuous railing that would be “detrimental to the looks of the building,” he suggested installing two short rail pieces perpendicular to the building (see Figure 48).72 This simple solution, he argued, was less expensive and less conspicuous. (The railing is no longer extant.)

The first interior space to be significantly altered was the basement. The basement was originally designed with an underground parking garage accessed by ramps from the southwest and the northeast (see Figure 49). The garage included parking spaces for 30 cars, a parking attendant’s booth, a grease pit, and car wash and car maintenance areas. A series of mechanical rooms were located in the east corner of the basement. A sidewalk extended from one end of the ramp to the

72. Gropius to Thomas A. Pope, Supervising Architect, Office of Foreign Buildings, November 3, 1961, TAC Archives.

73. Memorandum “Changes for the Athens Embassy Building According to the Washington Meeting of June 29, 1956,” June 1956, TAC Archives.

74. Although written documentation of this alteration has not been uncovered to date, there is a floor plan of the basement renovation dated 1964. See “Embassy Building, Basement New Construction,” architect unknown, 1964, drawings collection of the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO), U.S. Department of State (hereafter cited as the drawings collection of the OBO).

other along the northwest edge of the garage, and beyond this was finished space separated from the rest of the basement. This area included a small lobby with access to the elevator and stairwell, which allowed the ambassador and other dignitaries to step right into their automobiles from the basement elevator.73 The lobby also accessed a double-loaded corridor that led to a mail room, supply storage, and telephone operators’ room, as well as the cafeteria and kitchen (shown in Figures 46 and 47).

The basement was first renovated circa 1964 when the underground parking garage was abandoned and the area was partitioned and converted into finished space.74 No changes were made at this time to the mechanical room or the finished space northwest of the sidewalk. The next change occurred in the mid-1970s when the vehicle ramp from the southwest was closed off (see text below), and part of the space in the tunnel of the ramp was converted into a carpentry shop. At some point before 1980, the service ramp on the northeast was modified to serve as a pedestrian entrance only.75 In the early 1980s, minor modifications were made to the interior partitions and a marine security guard booth was constructed at the northeast pedestrian entrance (see text below). Subsequent alterations (dates unknown) converted the kitchen and dining area into offices, partitioned the shop space in the southwest tunnel into offices, and further modified the interior partitions of the former parking garage. Today, the only remnants of the original basement are the concrete curbs that once defined the parking area, the configurations of several mechanical rooms, the double-loaded northwest corridor, and the configurations of several rooms along this corridor (see Figure 50).

In the 1970s, the FBO engaged The Architects Collaborative (Gropius had passed away in 1969) to design a perimeter security fence and other modifications to the Athens embassy compound. The fence consisted of nine-foot-high galvanized steel-tube pickets set into a concrete foundation (see Figure 51). A combination of sliding and swinging gates allowed for access into the site. When the installation of the perimeter fence was completed in October 1977, it significantly changed the original open character of the site (shown in Figures 25, 29, and 31) and visitors’ impressions of the chancery. 76 With the fence in place, Gropius’s intention for “an inviting building, free of forbidding walls and fortress-like enclosures” was largely overturned. At street level, views of the building were obscured, and public access to the grounds was largely cut off. Later changes in the landscape would further alter the views of the building from surrounding streets. Despite this, the perimeter fence greatly enhanced site security during a period of mounting threats to State Department personnel in embassies around the world.

As part of the perimeter security project, the vehicle entrance ramp on the southwest side of the site leading to the basement level was closed off (see Figure 52). All paving, gravel, curbs, and walls associated with the ramp were removed. A new wall to seal the entrance was constructed, the area was filled and graded, and curbing and pavement were added at the sidewalk to match adjacent details. TAC also redesigned the service ramp on the northeast side of the site to accommodate the perimeter fence.

76. Certificate of completion for the installation of the security fence, October 18, 1977, miscellaneous files of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens.

77. In 1976, the embassy’s contracting officer made a purchase of $50,651 worth of ceramic tiles from the original German manufacturer of the ceramic screens. See William W. Ryan, Contracting Officer, to Wilhelm Gail’sche Tonwerke, Germany, January 29, 1976, miscellaneous files of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens.

The ramp was realigned, regraded, and resurfaced. This involved the demolition and reconstruction of the north retaining wall and the construction of new concrete curbs and a planting bed.

In addition to the perimeter security fence and the associated modifications to the entrance ramps, TAC also designed changes to the ground-floor lobbies. In the main lobby, this included removing the original double glass doors from the northwest facade (shown in Figure 35) and replacing them with windows and mullions similar to the adjacent curtain wall. A segment of ceramic screen was installed along the exterior of the new glazed wall to match the rest of the facade.77 Also, the recess in the surface of the floor, which was originally designed as a space for rubber matting, was filled with concrete. The reception desk was relocated from its original position in front of the black and white marble mosaic wall panel to the north corner of the lobby and redesigned. Components of the original reception desk (shown in Figure 36) were reused and set into a new carpeted platform constructed with built-in teak plywood cabinets. The new reception desk used the black terrazzo top and steel frame from the original desk (see Figure 53).

TAC also prepared plans to remodel the consular lobby (shown in Figure 37), although the extent to which these modifications were carried out is unknown. Drawings indicate that TAC proposed closing the courtyard entrance and moving the entrance on the northeast facade to be flush with the adjacent curtain walls (see Figure 54). A memo dated 1977 states that the consular lobby was modified the previous year to include a small screening area for visitors, but it does not describe

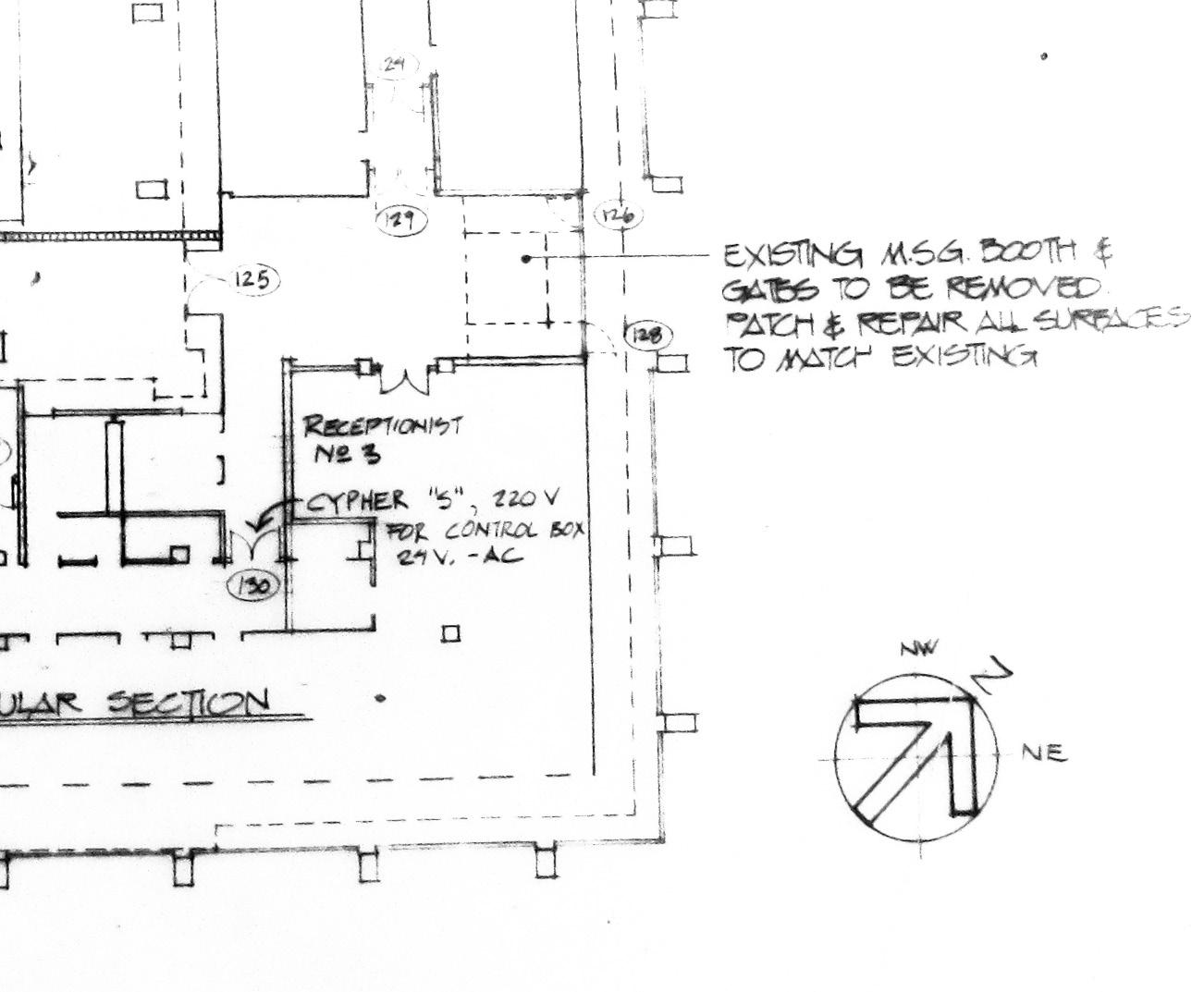

the changes. The memo also proposes the construction of a receptionist’s desk built of brick faced with steel plate and marble.78 Existing conditions drawings from 1981 indicate that the courtyard entrance was not modified following the TAC plans and remained as originally designed. The 1981 drawings do indicate that the consular entrance on the northeast facade was modified, but with a different configuration for the location of the doors than in the TAC drawings (see Figure 55). The 1981 existing conditions drawings indicate that a marine security guard booth was constructed in the consular lobby, which may be the same structure as the reception desk described in the 1977 memo.

In 1980, Oudens & Knoop, Architects, of Washington, D.C., prepared plans for the construction of an addition to the main lobby and a pavilion on the upper terrace, among other changes. The groundfloor addition expanded the main lobby and adjacent offices, which at the time were occupied by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). The new

addition was constructed against the southeast exterior wall of the main lobby, requiring the removal of one of the original ceramic screens (see Figure 56). The exterior walls of the addition featured Santa Marina marble cladding and a glazed clerestory to match the existing facade. The marble cladding of the addition used different size panels than the cladding of the original building to distinguish the new construction from the original. The exterior doors and push plates from the original entry were relocated and reused for the entry to the addition.

On the interior, the existing guard booth, which was located in the north corner of the lobby and featured elements of the original reception desk designed by Gropius (see text above), was disassembled. Partition walls were put up, and a new marine security guard booth was constructed in the center of the former lobby space, altering the floor plan and obstructing views of portions of the mosaic wall panels. In the new lobby space created by the addition, a new black and white mosaic panel was installed to match the existing panels.79 (Later, additional changes were made to the main lobby area when all of the existing doors, clerestory windows, and glazed curtain walls

were replaced with forced-entry ballistic-resistant doors and windows. The date of this alternation has not been conclusively determined.)80

The pavilion, located in the upper terrace at the top of the main entry stairs, was designed to serve as a lobby and screening area for the consular section (see Figure 57). It was originally planned to connect with the consular lobby via a semi-enclosed corridor constructed of two rows of ceramic tile screens.

Consequently, the Oudens & Knoop renovation also planned for the removal of the existing marine security guard booth from the consular lobby.

(Although the pavilion was constructed, no evidence of the semi-enclosed corridor remains, if it was ever realized.)81 Like the lobby addition, the pavilion featured Santa Marina marble cladding, a glazed clerestory, and glass doors to match the existing ground-floor facades. The location of the pavilion required the removal of an existing marble bench which was then sectioned and repositioned in the upper terrace as three smaller benches. Later, the footprint of the pavilion was expanded with the construction of an addition on the southeast facade. (The date of this alteration has not been determined.) Today, the pavilion is used as a drivers’ break room.

In addition to the ground-floor alterations, Oudens & Knoop redesigned the northeast entrance to the basement. This included the installation of security glazing at the exterior wall of the entrance (at the bottom of the former service entrance ramp) and the construction of a marine security guard booth inside this entry. On the upper floors, several existing corridor doors (nonoriginal) were removed and replaced with louvered wood doors.

80. According to information provided by Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations, U.S. Department of State, on December 14, 2012, the forced-entry ballistic-resistant doors and windows may have been installed in the 1980s.

81. The semi-enclosed corridor does not appear in subsequent architectural drawings or in photographs of the period, and there is no physical evidence that the corridor was constructed. Additionally, in 1982, Oudens & Knoop prepared drawings for a steel fence with turnstile between the pavilion and the southwest wall of the consular section. If the semi-enclosed corridor was constructed, there would have been no need for this additional steel fence. See “U.S. Embassy, Athens, Greece, New Fence at Ground Floor,” Oudens & Knoop, Architects,

In 1982, Oudens & Knoop prepared drawings for extensive renovations to the consular section, which at the time occupied the majority of the ground-floor office space. In the southeast corridor of the consular section, existing interior spaces were reconfigured and subdivided as offices for the Federal Benefits Unit (FBU). To provide direct access to the FBU waiting room from the courtyard a new exterior door was created by removing an existing window and a section of the existing ceramic screen. In the consular lobby, the existing transparent glass partitions and clerestories were removed, and the guard booth and countertops were demolished. The interior configuration of the lobby was modified, and a new receptionist’s desk, writing counter, and concrete planter were installed. The northeast entry to the consular lobby was modified to its existing condition. One of the doors was replaced with a window, and a ceramic screen was installed over the glazed portion of the bay. Also, it is likely that at this time the U.S. seal over the northeast entrance was taken down and reinstalled in the center bay of the southwest courtyard facade. (The U.S. seal in the courtyard was removed at some point after 2002, possibly in 2007 when consular services were relocated to the New Office Annex.)82 In the northeast corridor of the consular section, the original double-loaded corridor plan was eliminated, and the interior room configurations were modified as a waiting area, interview rooms, and offices for nonimmigrant visa (NIV) services. To provide direct access to the NIV waiting room from the courtyard, a new exterior door was created by removing existing windows and a section of the existing ceramic screen. Similar

February 22, 1982, drawings collection of the Office of Facilities Management, U.S. Chancery, Athens.

82. According to information provided the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations, U.S. Department of State, on December 14, 2012, the U.S. seal formerly marking the consular entrance is currently in storage in Athens.

changes were made in the northwest corridor of the consular section where the interior offices were reconfigured and a new exterior door to the courtyard was created (see Figure 58). Although consular services were relocated to the New Office Annex in April 2007, many of the alterations made during this renovation are still extant today.

In 1985, nearly a decade after the construction of the TAC perimeter fence, Bechtel Corporation, of San Francisco, California, designed perimeter security upgrades for the embassy compound. One component of the project was the construction of a security screening facility, or Compound Access Control (CAC), for the Vasilissis Sofias Avenue entrance. The CAC consisted of a one-story pavilion constructed of concrete block with a marble panel veneer and aluminum windows. It was located on axis with the main entrance at the top of a short flight of existing stairs and behind the TAC-designed fence and sliding gate. The project required the demolition of one flight of existing stairs to the lower terrace, but retained the reflecting pool and planting bed of the original design. On the northwest side of the CAC, new stairs and retaining walls were constructed to complete the ascent to the lower terrace. Also at this time, new delta vehicle barriers were installed at the entrances to the southwest parking area, and a new guard house (no longer extant) was constructed at the northwest entrance.

In preparation for the 2004 Olympics, modifications were made to the entrance and exit sequences of the CAC to provide accessibility.83 A ramp was constructed on the southeast elevation, requiring

changes to the stairs leading to the facility from the street. On the northwest elevation, the planting bed (original) was removed to provide space for a new stairway, which was reconfigured to include a landing and stairlift.

With the exception of the restroom in the ambassador’s suite, the restroom facilities in the chancery originally featured ceramic tile walls and floors, marble partition walls, and marble shelves. In 1992, all of the public bathrooms in the chancery were renovated, and all existing finishes were replaced. In 2007 a grenade was fired into the chancery, causing material damage to a section of the southeast facade. As a part of the resultant repairs, the ambassador’s restroom, which originally featured marble-tiled walls, was entirely remodeled and all existing finishes were replaced.

Several commemorative plaques and sculptures have been added to the landscape since the chancery’s construction. In 1996, the city of Athens presented the sculpture Niki by Pavlos Kougioumtzis to the city of Atlanta in honor of the Olympic Games. The sculpture represents a modern rendition of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. A cast of the sculpture set on a rectangular marble base was installed in the courtyard of the chancery in commemoration of the event. In June 1998, a plaque commemorating the tenth anniversary of the assassination of U.S. Deputy Attaché Captain William Nordeen was installed on the northeast wall of the lower terrace.

Later, in 2000, a statue of the American statesman George C. Marshall was also installed on the lower terrace (see Figure 59). The statue was created by Greek sculptor Theodorus Papayiannis.

In 1999, a 6.0 magnitude earthquake struck Greece near Athens causing minor structural damage to the chancery. As a result, repairs were made to cracks in interior walls as well as exterior marble panels and terrazzo paving.84 (See U.S Chancery, Athens, Historic Structure Report and Building Conditions Assessment, Volume 2 for additional information.)

In 2003, the street adjacent to the embassy compound on the northeast was closed to vehicles and became a limited-access park called the Makedonon Street Park. As part of the effort, original site and landscape features such as the existing stairs and cheek walls at the east corner of the site and existing olive trees were preserved and protected.