Behind the Curtain

A Creative and Theatrical Study Guide for Teachers

25 – 28,

25 – 28,

DCT Executive Director Samantha Turner

Resource Guide Editor Jessica Colaw

Resource Guide Layout/Design Jamie Brizzolara

Play

Dino-Light Presented by Lightwire Theater

Created by Ian Carney and Corbin Popp

DALLAS CHILDREN’S THEATER, one of the top five family theaters in the nation, serves over 150,000 young people and their families each year through its mainstage productions, educational programming, and outreach activities. Since its opening in 1984, this awardwinning theater has existed to create challenging, inspiring and entertaining theater, which communicates vital messages to our youth and promotes an early appreciation for literature and the performing arts. As the only major organization in Dallas focusing on theater for youth and families, DCT produces literary classics, original scripts, folk tales, myths, fantasies, and contemporary dramas that foster multicultural understanding, confront topical issues, and celebrate the human spirit.

DCT is committed to the integration of creative arts into the teaching strategies of academic core curriculum and educating through the arts. Techniques utilized by DCT artists/teachers are based upon the approach developed in Integration of Abilities and Making Sense with Five Senses by Paul Baker, Ph.D.

TEKS that your field trip to Dallas Children’s Theater satisfies are listed at the back of this Resource Guide.

2024-2025 EDUCATION SPONSORS

O ce of Arts & Culture

THE THEODORE AND BEULAH BEASLEY FOUNDATION

CRAWLEY FAMILY FOUNDATION

HOLLOWAY FAMILY FOUNDATION

As part of DCT’s mission to integrate the arts into classroom academics, the Behind the Curtain Resource Guide is intended to provide helpful information for the teacher and students to use before and after attending a performance. The activities presented in this guide are suggested to stimulate lively responses and multi-sensory explorations of concepts in order to use the theatrical event as a vehicle for cross-cultural and language arts learning.

Please use our suggestions as springboards to lead your students into meaningful, dynamic learning; extending the dramatic experience of the play.

Permission

Margot B. Perot

The Strake Foundation

Medical City

The Ryan Goldblatt Foundation

Prosperity Bank

Capital One

Frost Bank and Frost Insurance

Green Mountain Energy

DCT’s official renewable energy partner

EDUCATIONAL SUPPORT IS ALSO PROVIDED BY SENSORY-FRIENDLY SPONSORS

FICHTENBAUM CHARITABLE TRUST Bank of America, N.A., Trustee

First Unitarian Church of Dallas

classroom.

Every DCT performance you see is the result of many people working together to create a play. You see the cast perform on stage, but there are people behind the scenes that you do not see who help before, during, and after every production.

Determines the overall look of the performance.

Guides the actors in stage movement and character interpretation.

Works with designers to plan the lights and sounds, scenery, costumes and makeup, and stage actions.

Plan the lights, sounds, scenery, costumes, make-up, and actions to help bring the director’s vision to life.

There are also designers who work to create the posters, advertisements, programs, and other media for the performance.

Build and operate the scenery, costumes, props, and light and sound during the performance.

Before the performance, they create a cue sheet to guide the crew in getting set pieces on and off the stage during the performances.

During the performance, the stage manager uses this cue sheet to direct people and things as they move on and off the stage.

Includes all of the performers who present the story on stage.

That’s right! There can be no performance without you—the audience. The role of the audience is unique because you experience the entertainment with the performers and backstage crew. You are a collaborator in the performance and it is important to learn your role so you can join all the people who work to create this Dallas Children’s Theater production.

Watching a play is different from watching television or a sporting event. When you watch T.V., you may leave the room or talk at any time. At a sporting event you might cheer and shout and discuss what you’re seeing. Your role as a member of the audience in a play means you must watch and listen carefully because:

• You need to concentrate on what the actors are saying.

• The actors are affected by your behavior because they share the room with you. Talking and moving around can make it difficult for them to concentrate on their roles.

• Extra noises and movement can distract other audience members.

Check the box next to the statements that describe proper etiquette for an audience member.

q Try your best to remain in your seat once the performance has begun.

q Share your thoughts out loud with those sitting near you.

q Wave and shout out to the actors on stage.

q Sit on your knees or stand near your seat.

q Bring snacks and chewing gum to enjoy during the show.

q Reward the cast and crew with applause when you like a song or dance, and at the end of the show.

q Arrive on time so that you do not miss anything or disturb other audience members when you are being seated.

q Keep all hands, feet, and items out of the aisles during the performance.

Draw a picture of what the audience might look like from the stage. Consider your work from the viewpoint of the actors on stage. How might things look from where they stand?

Write a letter to an actor telling what you liked about their character.

Write how you think it might feel to be one of the actors. Are the actors aware of the audience? How might they feel about the reactions of the audience today? How would you feel before the play began? What about after the show ends?

1 2 3 4

Which job would you like to try? Acting, Directing, Lighting and Sounds, Stage Manager, Set designer, Costume designer, or another role? What skills might you need to complete your job?

ACTOR any theatrical performer whose job it is to portray a character

CAST group of actors in a play

CENTER STAGE the middle of the stage

CHARACTER any person portrayed by an actor onstage. Characters may often be people, animals, and sometimes things.

CHOREOGRAPHER the designer and teacher of the dances in a production

COSTUME DESIGNER the person who creates what the actors wear in the performance

DIRECTOR the person in charge of the actors’ movements on stage

DOWNSTAGE the area at the front of the stage; closest to the audience

HOUSE where the audience sits in the theater

LIGHTING DESIGNER the person who creates the lighting for a play to simulate the time of day and the location

ONSTAGE the part of the stage the audience can see

OFFSTAGE the part of the stage the audience cannot see

PLAYWRIGHT the person who writes the script to be performed. Playwrights may write an original story or adapt a story by another author for performance.

PLOT the story line

PROSCENIUM the opening framing the stage

PROJECT to speak loudly

PROP an object used by an actor in a scene

PUPPET a movable model of a person or animal that is used in entertainment and is moved either by strings from above, or by a hand inside it.

SET the background or scenery for a play

SETTING the time and place of the story

SOUND DESIGNER the person who provides special effects like thunder, a ringing phone, or crickets chirping

STAGE CREW the people who change the scenery during a performance

STAGE MANAGER the person who helps the director during the rehearsal and coordinates all crew during the performance

UPSTAGE the area at the back of the stage; farthest from the audience

Puppetry, like music and dance, is an ancient art ever evolving and renewing itself. A puppet is an inanimate figure that is caused to move by human effort before an audience. The four most common kinds of puppets are:

Operated from below the stage behind a screen or curtain. Light shines through the holes to create a shadow on the screen.

Manipulated from below the stage or from directly behind the playing area, as in Black Theatre.

Operated from below the stage.

Manipulated from above the stage.

Puppets exist in a wide variety of types, and may be two- or three-dimensional. They vary in size from finger puppets to larger-than-life size, and range from the simplest shapes to elaborately articulated figures.

The origins of puppetry are veiled in antiquity, but it is known that primitive peoples made puppets long before the invention of writing. Puppets probably served a function in the ritual magic practices by early man. Extensive use of puppetry for religious purposes is recorded in every subsequent civilization.

For centuries, puppetry was effectively utilized in the church, but gradually some of the comic characters and scenes, originally introduced to lighten the miracle plays, got out of hand and became offensively boisterous and vulgar. Eventually, puppets were totally expelled from the church. Henceforth, the art of puppetry was practiced in the streets, fairgrounds, inns, and later, when it had gained status again, in theaters of its own. In the present day it has returned to some churches. Whatever the setting, audiences have always responded wholeheartedly to those qualities unique to the art.

When operated with skill and artistry, puppets can convey with great intensity every emotion known to humankind, distilling the essence of feelings common to everyone. Puppets eloquently express the gamut of dramatic styles, from slapstick to riotous comedy to heart rending pathos and soul wrenching drama. Images: https://www.adventure-in-a-box.com/shadow-puppet-templates/, DCT staff, https://www.habausa.com/, and istock

Attending a play is an experience unlike any other entertainment experience. Because a play is presented live, it provides a unique opportunity to experience a story as it happens. Dallas Children’s Theater brings stories to life through its performances. Many people are involved in the process. Playwrights adapt the stories you read in order to bring them off the page and onto the stage. Designers and technicians create lighting effects so that you can feel the mood of a scene. Carpenters build the scenery and make the setting of the story become a real place, while costumers and make-up designers can turn actors into the characters you meet in the stories. Directors help actors bring the story to life and make it happen before your very eyes. All of these things make seeing a play very different from television, videos, or computer games.

Hold a class discussion when you return from the performance. Ask students the following questions and allow them to write or draw pictures of their experience at DCT.

• What was the first thing you noticed when you entered the theater?

• What did you notice first on the stage?

• What about the set? Draw or tell about things you remember. Did the set change during the play? How was it moved or changed?

• Was there any space besides the stage where action took place?

• How did the lights set the mood of the play? How did they change throughout? What do you think the house lights are? How do they differ from the stage lights? Did you notice different areas of lighting?

• What did you think about the puppets? Do you think they fit the story? What things do you think the puppet designers had to consider before creating the puppets?

• Was there music in the play? How did it add to the performance?

• What about the puppeteers? Do you think they were able to bring the characters to life? Did you feel caught up in the story? What things do you think the performers had to work on in order to make you believe they were the characters?

LIGHTWIRE THEATER is a unique entertainment experience that utilizes light, technology, and music to tell captivating stories. Our shows are designed to bring audiences of all ages into a fantastical world of imagination.

Lightwire Theater has been featured as a semi-finalist on NBC’s America’s Got Talent and winner of Tru TV’s Fake Off. The group combines theater and technology to bring stories to life in complete darkness and is internationally recognized for its signature brand of electroluminescent artistry.

Lightwire co-creators IAN CARNEY and CORBIN POPP met in New York City while dancing in Twyla Tharp’s Movin’ Out on Broadway. An immediate connection was made between the kindred spirits as they discovered their mutual love of art, theater, and technology. After coming across a product called, “el wire,” the lights turned on and the possibilities seemed endless. Together, with their wives Eleanor and Whitney, they began to experiment with shapes and designs to develop puppetry-based neon creatures that quickly came to life.

Based in New Orleans, Lightwire Theater continues to create and deliver innovative theatrical experiences to audiences worldwide including: Hong Kong, Estonia, Canada, Belarus, China, Abu Dhabi, and as finalists on My TF1’s, The Best Le Meilleur Artiste in Paris.

Excerpted from: lightwiretheater.com/about

Use the following questions to lead a discussion with students after attending DCT’s performance of Dino-Light.

• What is the difference between a scientist, a magician, and an artist? In what ways is the scientist in Dino-Light like a magician or an artist?

• What friends does the dinosaur make on his journey? In what ways are they similar and in what ways are they different from him?

• What did the dinosaur learn from his experiences?

• Retell the story from the point of view of another character. What do they notice that the dinosaur did not notice?

Excerpted from: Lightwire Theater’s Dino-Light Study Guide

What did you think of the Dino-Light performance at Dallas Children’s Theater? What would you tell others about the performance? Did you know that a review, an evaluation (based on personal opinion) of a performance printed online or in newspapers or magazines, can inspire others to see (or not to see) a play? Now’s your chance to play the part of theater reviewer! What do you want to share about Dino-Light at DCT?

Dino-Light Review

You will need:

• Dino-Light Review handouts

• Pencils

Give each student a Dino-Light Review handout. Remind students that a review is based on their own personal opinion and evaluation of the play. After everyone finishes their handout, ask volunteers to share with the class.

Created by: Jessica Colaw Inspired by: Lightwire Theater’s Dino-Light Study Guide

If needed because of the age or writing level of your students, encourage them to draw their reviews.

By:

What was the performance about?

Who were the characters in the performance?

Did you like the performance? Why or why not?

What was your favorite part of the performance?

Would you recommend this performance to another person?

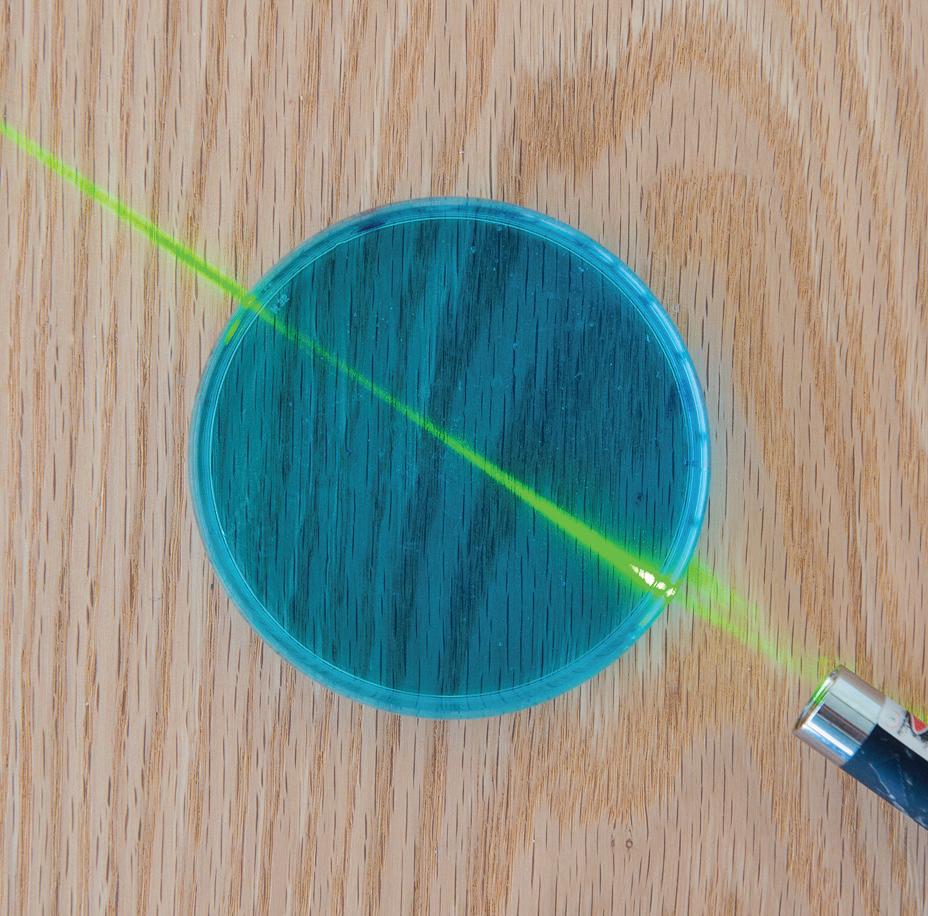

Dino-Light incorporated the use of lights in order to tell the story on stage. Light is fascinating, whether built into a dinosaur puppet or studied in the classroom. In the following science lesson, explore how different colored lights change when shined through different colored gelatin.

Laser

Tools and Materials

• Petri dishes

• Square, open-topped boxes made of clear plastic

• Two packages of Jello®—one red and one blue

• Package of clear gelatin (Knox® brand is easy to find in supermarkets)

• Red and green laser pointers (Note: Please be careful not to shine these lights into anyone’s eyes! Safety first!)

• A protractor

Assembly

1. Prepare the red, blue, and clear gelatin according to the Jello Jigglers™ recipe (found on the Jello® boxes).

2. Pour about 1/2 inch (1.25 centimeters) of blue gelatin into a round Petri dish.

3. Pour about 1/2 in (1.25 cm) of red gelatin into a round Petri dish and 1/2 in (1.25 cm) into a square container.

4. Pour about 1/2 in (1.25 cm) of clear gelatin into a square container.

Hold the red laser flat against the table so the light beam is parallel to the table. Shine the laser through the middle of the round dish of red gelatin—a beautifully visible beam travels through it. Then shine the laser through the blue gelatin. Notice that the beam gets dimmer almost as soon as it hits the gelatin. Shine the laser through the dish of clear gelatin. Notice that you can see the beam very clearly.

Shine the green laser through the round dish of blue jello and observe the beam as it travels through the jello. Shine the green laser through the red jello and notice that the beam gets dimmer as soon as it enters the jello.

Hold the laser parallel to the table and shine it through one side of a square dish of red or clear gelatin. (Use the red laser for the red gelatin; use either the green or red laser for the

clear gelatin.) Start with the beam perpendicular to the edge; notice that it passes through the gelatin in a straight line. Now rotate the laser so that the beam hits the flat edge of the dish at an angle. As you do so, notice how the beam bends towards the center of the dish. Use the protractor to measure the angle of incidence between the beam and a line perpendicular to the flat edge, and the angle of refraction after it enters the gelatin.

Next, take the round Petri dish of blue gelatin. Holding the green laser parallel against the tabletop, shine the laser through the middle of the curved edge of the dish (it should look as though the laser is bisecting the circle). Now, starting from the laser's original position, slide the laser in a straight line to the right and then the left, so that the beam moves toward the outer edges of the dish. Notice how, as you do so, the beam bends towards the center of the dish. (Note: Hold your two lasers parallel to one another and shine both beams through the curved edge of the dish, and then use a piece of white paper or waxed paper as a screen to find the focal point where the two beams cross—see the What's Going On? section below for more information.)

Finally, take a square dish of red or clear gelatin. Holding either laser parallel to the table (use the red laser for the red gelatin; use either the red or the green for the clear gelatin), shine the beam through one edge of the box and notice the beam coming out the far side. Now, shine the beam through one side of the box so that it hits the adjacent side at a glancing angle—you'll notice that no light exits the box through that side! (You may need to play around a bit to find the right glancing angle.) The largest angle at which no light escapes is called the critical angle

Gelatin is colloidal—its large molecules are suspended in solution in such a way that they don't settle out—and so it scatters enough of the laser beam to make it visible. Red dye in the red gelatin doesn't absorb red light, so you can see the red beam when it shines through it. The blue gelatin (which is actually cyan) absorbs red light (but not blue or green), so the red beam isn't visible.

As light enters the gelatin, the change in medium causes a change in the speed of the light and a change in the index of refraction. This change in speed causes the direction of the beam to refract, or bend. When going from a high-speed material such as air to a lower-speed material such as gelatin, the beam will bend into, or towards, the gelatin.

Light traveling through a convex lens will converge. If you shined two parallel beams through your gelatin, you saw that parallel beams of light will come together at a point on the far side of a curved lens (in this case, the curved side of the dish)—this is called the focal point. (Teachers! This might be a good time to introduce the reversibility of light. Shine a laser through your gelatin "lens"—mark its path into and then out of the gelatin. Shine a laser backwards along this path— that is, shine it into the path that the original beam exited. The light path followed by the reversed beam will be exactly the same.)

As light travels from a slower (or more optically dense) substance to a faster medium, it may reflect in a similar way to the skimming of a stone off the surface of water. If the beam hits at an angle that is small relative to the surface, then the light will completely reflect—this is called total internal reflection. If the angle is closer to perpendicular, then the beam will exit out the side of the dish.

Excerpted from: exploratorium.edu/snacks/laser-jello

As the dinosaur explored in Dino-Light, he discovered new friends along the way. What is a friend? How do you make friends? How do you keep friends? What happens when you and your friends fight? How do you make your friends feel loved? What would it feel like for you to receive a thank you note from a friend or to hear about how you are a good friend to another person?

As a class, discuss qualities that describe a friend. Write the ideas on a white board or on a big piece of paper that can be displayed in the classroom.

Have your students write a thank you note or draw a picture for a friend (could be a classmate, or another friend). The note or picture should express gratitude for the relationship, explain why they care for that friend, or tell a story from the friendship. Invite the students to give the thank you notes or pictures to their friends.

Adapted from: clsteam.net/info/daily-sel-lesson-----friendship-6-1

The puppets in Dino-Light use special technology to glow in the dark. You may not have access to that material, but you can still make a puppet that “lights up.” Try out the following activity and explore ways to make your project glow.

You will need:

• Paper lunch bags

• Materials that either reflect light (like glitter or shiny gem stickers) or glow-in-the dark (stickers, markers, paint)

• Other materials to help complete the puppet (regular markers/crayons, glue, etc.)

Begin by putting on your “magic” glasses (use your hands to make a binocular-type shape to look through). Look around the classroom: what do you see? What are you inspired to recreate in a work of art? Be creative and make something unique (will you draw, paint, or sculpt something out of clay or recycled materials?)! When everyone is done creating their artwork, display the pieces around the room and go on an art walk. Don’t forget to celebrate everyone’s different and beautiful perspectives!

Created by: Jessica Colaw

The Dino-Light performance relied on gestures to help tell the story on stage. Gestures are an important part of theater! To understand more about how gestures (and sounds) can relay information, try out this classic theater game:

Drama Game: The Machine

Procedure:

1. Start with one student making a noise and a simple repeatable gesture.

2. When the student has a rhythm and another student has an idea for a movement which connects to the first gesture, that student joins the first student by making a new noise and movement which connects to the original gesture.

3. Each student joins in with a new noise and gesture and connects to the others in some way until all students are involved in creating the machine.

Evaluation:

• What did you imagine the machine you created was?

• What was your part in making it?

• How could we make the machine better?

• Was it difficult to keep your concentration until everyone was creating the machine?

Excerpted from: bbbpress.com/2013/04/the-machine/

The dinosaur in Dino-Light may be a puppet, but long ago real dinosaurs ruled the earth! Did you know there are over 1,000 known species of non-avian dinosaurs (with more possible!)? As a class, in groups, or individually, research a dinosaur (pick a favorite, or learn about a new one). Check out these resources to get started:

National Geographic Little Kids First Big Books of Dinosaurs by Catherine D. Hughes

Big Book of Dinosaurs by Angela Wilkes

DK First Dinosaur Encyclopedia by Caroline Bingham kids.nationalgeographic.com/animals/prehistoric amnh.org/explore/ology/paleontology

Once you have researched your dinosaur, use your new knowledge to create a dinosaur-inspired project. Ideas could range from making a poster detailing your findings to building a model of your dinosaur out of recycled materials to writing a poem about the dinosaur…be creative!

Created by: Jessica Colaw

Learn more about Lightwire Theater’s work at lightwiretheater.com/

Check out the following interview of Ian Carney, one of the co-creators of Dino-Light: shoutoutla.com/ meet-ian-carney-director-of-lightwire-theater/

110.2 English Language Arts and Reading, Kindergarten

b.10 Composition: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and thinking using multiple texts - writing process. The student uses the writing process recursively to compose multiple texts that are legible and uses appropriate conventions.

110.3 English Language Arts and Reading, Grade 1

b.11 Composition: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and thinking using multiple texts - writing process. The student uses the writing process recursively to compose multiple texts that are legible and uses appropriate conventions.

110.4 English Language Arts and Reading, Grade 2

b.11 Composition: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and thinking using multiple texts - writing process. The student uses the writing process recursively to compose multiple texts that are legible and uses appropriate conventions.

110.5 English Language Arts and Reading, Grade 3

b.11 Composition: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and thinking using multiple texts - writing process. The student uses the writing process recursively to compose multiple texts that are legible and uses appropriate conventions.

112.2 Science, Kindergarten

b.1 Scientific and engineering practices. The student asks questions, identifies problems, and plans and safely conducts classroom, laboratory, and field investigations to answer questions, explain phenomena, or design solutions using appropriate tools and models.

112.3 Science, Grade 1

b.1 Scientific and engineering practices. The student asks questions, identifies problems, and plans and safely conducts classroom, laboratory, and field investigations to answer questions, explain phenomena, or design solutions using appropriate tools and models.

112.4 Science, Grade 2

b.1 Scientific and engineering practices. The student asks questions, identifies problems, and plans and safely conducts classroom, laboratory, and field investigations to answer questions, explain phenomena, or design solutions using appropriate tools and models.

112.5 Science, Grade 3

b.1 Scientific and engineering practices. The student asks questions, identifies problems, and plans and safely conducts classroom, laboratory, and field investigations to answer questions, explain phenomena, or design solutions using appropriate tools and models.

117.102 Art, Kindergarten

b.2 Creative expression. The student communicates ideas through original artworks using a variety of media with appropriate skills. The student expresses thoughts and ideas creatively while challenging the imagination, fostering reflective thinking, and developing disciplined effort and progressive problem-solving skills.

117.105 Art, Grade 1

b.2 Creative expression. The student communicates ideas through original artworks using a variety of media with appropriate skills. The student expresses thoughts and ideas creatively while challenging the imagination, fostering reflective thinking, and developing disciplined effort and progressive problem-solving skills.

117.108 Art, Grade 2

b.2 Creative expression. The student communicates ideas through original artworks using a variety of media with appropriate skills. The student expresses thoughts and ideas creatively while challenging the imagination, fostering reflective thinking, and developing disciplined effort and progressive problem-solving skills.

117.111 Art, Grade 3

b.2 Creative expression. The student communicates ideas through original artworks using a variety of media with appropriate skills. The student expresses thoughts and ideas creatively while challenging the imagination, fostering reflective thinking, and developing disciplined effort and progressive problem-solving skills.

117.104 Theatre, Kindergarten

b.5 Critical evaluation and response. The student responds to and evaluates theatre and theatrical performances.

117.107 Theatre, Grade 1

b.5 Critical evaluation and response. The student responds to and evaluates theatre and theatrical performances.

117.110 Theatre, Grade 2

b.5 Critical evaluation and response. The student responds to and evaluates theatre and theatrical performances.

117.113 Theatre, Grade 3

b.5 Critical evaluation and response. The student responds to and evaluates theatre and theatrical performances.