Abstraction & Economy Myths of Growth

Edited by Eva Maria Stadler & Jenni Tischer

Glossary in Quotes 6

Exhibition on Sixteen Pages: Introduction by Eva Maria Stadler and Jenni Tischer 11

Exhibition on sixtEEN PAgEs 17

monEy Setting of Values 33

EvA mariA stAdler Abstraction as Critique of Abstraction 35

christiNA von brAUN Digitizing Art, Money, and Man 51

blAiSE KirschNer aNd david PAnos Sell Everything, Buy Everything, Kill Everything 61

lEigh clAirE LA bergE There Is No More Abstraction 71

bEAt WEber What’s the Matter with Money? On the Relation between Abstraction and Economic Value 81

PAtriciA grzonkA 17,000 Iron Bolts Don’t Lie: On Economy, Abstraction, and Truth in Otto Wagner’s Postsparkasse 97

christiAN scherrer “Who Paints Abstractly?” A Socioeconomic History of Art after Alexandre Kojève 107

PRoPerty aNd dEbt Questions of Rededications 125

brENnA bHANdAr Legal Abstractions: Violence and Vulnerability 127

sVEN lütticKEN Concrete Abstraction – Our Common World 135

kArEL cÍsA ˇ r From “Second-Order Formalism” toward “Political Geometry”: The Work of Florian Pumhösl 153

dEnisE FerrEirA da silvA Blacklight 161

grid A Symbolic Form 171

JENni tischer Off the Grid: Skipping Rope in between the Abstract and the Concrete, Touching Its Material (Pre)Conditions, (Pre)Attitudes, and Anticipations 173

SAbEth bUChmaNN Again(st) the Progression Rule: Reflections on the Nexus of Abstraction and Economy in Brazilian Art of the 1960 s and 70 s and Its Reception 187 R. H. QuAYtmAN Abstract Painter 199

EvA kErnbAuEr Grids, Interfering: Queer Relationality in Works by Lorna Simpson, Andy Warhol, and Sol LeWitt 205

clEmENs APPrich Always Be Filtering 217

NAturAl cAPitAl The Fiction of Post-Season 229

MAriNA vishmiDt Core Absence 231

mARKUs WiSSEN Systemic Externalities: On the Socioecological Costs of the Capitalist Mode of Production 245

GAbRiELE JutZ Absolut Konkret: Technical and Material Aspects of Early Abstract Film 257

Image Credits 270

Acknowledgments 271

Imprint 272

Absolute / Concrete

[I]n the realm of early abstract film, aspects of spiritual teachings go hand in hand with enlightened aesthetics of abstract constructivism. The adjective absolut […] indicates a desire for the autonomy of the cinematic medium. The “pure” or “absolute” film of the 1920s did not seek inspiration from other arts but explored instead its own medium-specific characteristics. See Jutz, p. 267

Abstract Art

Modern “abstract” art and its discourse were in fact a problematization of abstraction. Already in the interwar period, “abstract” artists were well aware that their work constituted such a failure, and they modified or rejected the term “abstract art.” Piet Mondrian called his neoplastic work “abstract-real” art, and Theo van Doesburg and others later preferred the term art concret or concrete art. See Lütticken, p. 139

Algorithm

[A]lgorithms are never fully “objective.” […] [A] critique of the implicit assumptions and patterns coded into machine-learning processes is crucial. [...] Because we are subject to the same symbolic (i.e., language-based) order, filter algorithms eventually (re)produce cultural bias in the forms of racist, sexist, and classist beliefs. See Apprich, p. 221–223

Bitcoin

The idea that Bitcoin-like projects would be useful in challenging official currencies has failed thus far to receive empirical support from the experience of decentralized crypto projects. The key lesson is that for stable, generally acceptable money, hard limits to its quantity or fancy technologies for its operation matter less than the guarantees of reliable social commitments behind it. […] In the case of Bitcoin, its mostly libertarian supporters see it as a milestone in purifying capitalism from politics, a digital utopia governed by competitive individualism, and exchange facilitated by a kind of money considered somewhat neutral. See Weber, p. 94

Bitcoin mining is also extremely energy-intensive, and has been getting more so over time; as a “decentralized waste heat generator,” in 2015 the Bitcoin network already had an energy consumption comparable to that of Ireland. See Lütticken, p. 150

Concrete Art

In [Alexandre] Kojève’s view, the value of the work of art (its beauty) can become concrete only if it no longer remains mediated through something else (what it represents), that is, when its value can only be found within the work of art itself.

[O]ne can already guess why for Kojève particularly nonrepresentational painting came into question as “concrete.” See Scherrer, p. 112

[T]he motif of the Möbius strip […] was as decisive for the Swiss artist, architect, and theorist Max Bill (1908–1994) as it was for his Brazilian colleagues. […] Their models of Neo-Concretism [Neoconcretismo] followed the idea of a smooth transfer between art, architecture, urbanism, and everyday organization, evident for example in the construction of the new capital Brasilia, which was built in just a few years during the 1950s. Modeled after an airplane, it is based on a functional separation of spheres of living, working, producing, consuming, leisure, etc. – the modernist concept of international style par excellence. See Buchmann, p. 192

Diagram

Artist Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s essay “Dear Artfukts, Look at My Curve: A Report to an Academy” [2013] was occasioned by her finding her profile on the site ArtFacts.net, which deploys an algorithm to rank contemporary artists. Looking at the (drooping) graph that showed her career, Sadr Haghighian reflects on the complicated relationship between herself and this graph in what is also a feminist meditation on a new form of objectification (her “curve”): “I don’t identify with what the image represents but I participate in it as much as it participates in me, drawing on its character and power as it draws on my character and power. The curve and I are entangled in a mimetic dance, imitating and becoming one another. Our shapes submerge into one amorphous thing as we interact, and in this process of participation I am not a subject looking at an object that represents me.” See Lütticken, p. 145

Externalities, Expropriation, and Extraction

[T]he creation of exceptions and externalities is seen as fundamental to how capitalist economies and societies function in the critical accounts, from “surplus value” in Karl Marx’s analysis to the production of “cheap nature” […] and many other contemporary theories that focus on the “ex”s of capital beyond those of exchange and exploitation (extraction, expropriation, etc.). See Vishmidt, p. 233

As Nancy Fraser […] states, “capitalism is something larger than an economy,” as the capitalist economy needs a “noneconomic background” that is both external to it and potentially open to incorporation, to appropriation and expropriation –to abstraction. See Lütticken, p. 137

Capitalist societies have an inherent tendency to externalize socioecological costs. And this tendency has grown into a fundamental crisis of society-nature relations, which increasingly calls into question the capitalist mode of production and the imperial mode of living corresponding to it. See Wissen, p. 247

Finance

Finance then occupies a unique role here. Or it did: these debates were happening in the wake of the 2007–2008 global credit contraction and subsequent recession. It seemed to be agreed that f inance was somehow intangible, unrepresentable, elusive – in a word, abstract. […] [O]ne could go even further and claim that the problem of method revolves around the problem of abstraction and the abstract entities and processes of which finance is supposedly composed. For scholars interested in translating financial objects and practices from one field to the other, abstraction has provided a crucial site of exchange. See La Berge, p. 75

Geometric Abstraction

In Western Europe and the United States in the 1960s, then-dominant geometric abstraction followed a rule defined within the context of historical geometric abstraction: the golden ratio’s rule of progression, a combination of organic and technical processes. In 1917 and in the run-up to the international breakthrough of geometric abstraction, Scottish mathematical biologist D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948) published his work On Growth and Form, a study of the relationship between biological growth processes and mathematical progressions that are close to the approximate progression of the golden ratio. See Buchmann, p. 190

Grid

The Cartesian grid is everywhere and binds all thinking. Numbers win, let’s face it. Luckily for painters, or anyone whose work addresses the eye, the grid links math (algebra) with Euclidian geometry, and it is geometry that interests me. I use it to generate ways to approach painting that I could never have arrived at through my own imagination. I think all paintings are, by their typically rectangular nature, natural models for grid systems. See Quaytman, p. 201

As the grid is “antinatural” – one of its distinct characteristics, according to Rosalind Krauss […] – it produces no “natural” logic, which means that it does not naturalize order, and possibly defies naturalizing tendencies that define one’s place in the world. In this sense, the “antinatural” properties of grids have indeed queering potential, producing an erotics of relationality that does not fix location, identity, or meaning, thus expanding the registers of individual subjectivity without ordering them in any significant way, either of mapping, ranking, or identification. See Kernbauer, p. 209

Growth

The capital expansion in and through art goes hand in hand with shrinkage, with austerity, and precarity. Capitalism’s ongoing extractivist violence can no longer guarantee the “growth for all” that postwar Western nations promised their (and only their) citizens. With economic growth being concentrated in emerging economies, and neoliberal tax cuts and other policies facilitating upward wealth redistribution (for instance, through art market speculation), tensions intensify, and are expertly translated into ethnic and cultural terms. Meanwhile, rising CO2 emissions constitute the one form of growth that seems like a truly global commons. See Lütticken, p. 151

[T]here is no process of increasing abstraction, nor of increasing commodification; there really are no conceptual increases, so to speak, and certainly not in analyses of capitalist growth and value. We have to find another way. Therefore, I endorse (and attempt to remedy) Stewart Martin’s […] contention that “institutional theories of art and the ‘artworld’ […] have so far been developed at a level of generality that fails to register the specificity of capitalist forms.” See La Berge, p. 74

1 R. H. Quaytman, קקח, Chapter 29, 2015

2 Florian Pumhösl, Battle of Manila Bay (Turning Maneuvers), 2005

4 Cauleen Smith, The Grid, 2011, still

3 Dierk Schmidt, Tableau 11, Oturupa, Okahandja, 2006

6 Adrian Piper, Parallel Grid Proposal for Dugway Proving Grounds Headquarters, 1968

5 Cauleen Smith, The Grid, 2011, still

7 Cameron Rowland, Pacotille, 2020

MONEY Setting of Values

When it comes to the question of the origin of money, abstraction is not far away. Even the material value of land, gold, and silver, but also the value of grain or the value of pigs and cattle – they are all tied to the symbol and the sign that are negotiated in the act of valuation. This transformation denotes an abstraction process in which the (im)material object is translated into value. After the replacement of the gold standard and the increasing importance of futures and options, digital currencies are increasingly taking over the function of money in financial markets, giving the abstract another dimension. We ask how artistic practices and theories have become inscribed in processes of abstraction, and how they oppose their appropriation.

35 Eva Maria Stadler

51 Christina von Braun

Abstraction as Critique of Abstraction

Digitizing Art, Money, and Man

61 Blaise K irschner and David Panos Sell Everything, Buy Everything, Kill Everything

71 Leigh Claire La Berge

There Is No More Abstraction

81 Beat Weber What’s the Matter with Money?

97 Patricia Grzonka

107 Christian Scherrer

17,000 Iron Bolts Don’t Lie

“Who Paints Abstractly?”

2 hrs: Online meeting with Jenni. Read additional information sent by email. Think. Back and forth to align what is in both our minds. Online search: How to divide a rectangle into 7 equal parts? Find: andreasaronsson.com/guides/perspective-drawing/divide-into-equal-parts/. Dividing without measuring. Too simple? What does this have to do with abstraction and economy? Let’s see… Draw the lines. Maybe color. 8 instead of 7 parts. 1 part for the series and 7 for the individual lectures. 1 unit = 2 hrs (€100).

2 hrs: Quick test colors and fonts. Email for feedback and size check. Further color tests. How do I decide on color? I decide to choose partly on taste, partly on color expressing feeling toward the work. Personal, so: Red = excited (about people and topic of lectures); beige = tension (difficult to not exceed 2 hrs). Quick rewrite text below.

Eva M aria Stadler

Abstraction as Critique of Abstraction

Translated by Lian Rangkuty

Through five thematic fields – “Glass or Gold,” “Learning Abstraction,” “Spiritualistic Calculation,” “Flesh and Gold,” and “Real Abstraction” – the art historian and co-editor of this book Eva Maria Stadler underscores the dialectical potential of abstraction. Building on Rosalind Krauss’s analysis of Picasso’s early collages, Eva Maria Stadler’s contribution sheds light on the question of what defines the “abstract” in art and how artistic methods connect abstraction to economic processes. She traces the correlation between the decoupling of monetary value from the gold standard with the detachment and free circulation of signs within art.

Eva Maria Stadler is Professor of Art and Knowledge Transfer and head of the Institute for Art and Society at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, as well as a curator of contemporary art. She has taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart. From 2012 to 2013 she was director of the Gallery of the City of Schwaz, Austria. From 2007 to 2011 she was curator of contemporary art at the Belvedere in Vienna; from 2006 to 2007 curator in residence at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna; and from 1994 to 2005 she was director of the Grazer Kunstverein. She is the author of “Hochschuleinrichtung. Von der Hochschule für angewandte Kunst zur Schule Oberhuber,” in Schule Oberhuber. Der Künstler, Rektor, Ausstellungsmacher und sein Programm, edited by Cosima Rainer and Eva Maria Stadler (De Gruyter, 2023); “How Lovecraft Saved the World,” in Lovecraft, Save the World! 100 Jahre H. C. Artmann, edited by Alexandra Millner (Ritter Verlag, 2021 ); “Im Stil ist das Spiel das Ziel,” in Reflex Bauhaus. 40 Objects – 5 Conversations, Die Neue Sammlung – The Design Museum, Pinakothek der Moderne München, edited by Angelika Nollert (Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2019 ).

1 See Christian Scherrer’s essay in this volume, p. 107

1 Hilma af Klint, Group X, Altarpiece no. 1, 1915

As imagining infinity is strongly connected to the idea of abstraction, this essay inquires into the impact of modernism’s artistic strategies with regard to the phantasm of infinite growth. In becoming self-aware and self-reflexive, abstract form – ranging from the isolation of symbols, such as the brushstroke in Manet or Cézanne, the cubist deconstruction in Braque and Picasso, or the use of color in Mondrian, and on to the principles of geometry and diagrammatic expression in Hilma af Klint fig. 1 – unfolds an imagination of the universal. The possibilities just enumerated encompass spaces of the infinite, which have been and continue to be embraced, notably by the “aniconic and abstract tendency of advanced capitalism,” according to the art historian Sven Lütticken 2008, 47. In addition, although the Western notion of global universalism has been exposed – as in the critique posed by Neo-Concrete artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, as Sabeth Buchmann discusses in her text in this volume – its inherent power and its faith in infinite growth persist in the social and political conditions of capitalism and the immaterial economies of financialization.

“Abstraction facilitates thought,” the artist Max Bill has declared. He further explains that “this isolating abstraction aims to discern individual phenomena in complex processes” Bill 2008, 43. When speaking of abstraction, an abstraction from nature is implied; abstract means nonvisual or purely conceptual, while concrete describes the visible, tangible object. Accordingly, Bill describes his own artistic work as concrete, the “objectification” of something that is demonstrably real. In doing so, Bill follows the dichotomy of the terms abstract and concrete that the Russian-French philosopher Alexandre Kojève (1902 –1968 ) introduced in relation to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.1

The debates surrounding the differentiation of the terms “abstract,” “concrete,” “constructivist,” and “absolute” illustrate diverse conceptual approaches throughout the twentieth century. It is no coincidence that abstract art has gained more traction than concrete art. In the analysis that follows, emphasis is placed on the reception and transformation of abstraction and its interplay with economic processes.

Glass OR Gold

Félix Fénéon addressed the dynamics of abstraction when, in 1906 , he published a series of “News in Three Lines” in the Paris magazine Le Matin. These were distillations of true stories into short haiku-like texts (or even anticipations of “tweets”). Leveraging the structure of the mass-medium newspaper to bring any topic from anonymity to the public eye, Fénéon turned them into a “fake narrative” Krauss 1998, 4. From the structural dynamic of condensed, self-referential, and vacated symbols and their transformation into falsehoods, the American art

critic Rosalind Krauss, in her book The Picasso Papers, refers to André Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, which uses short news pieces similar to those composed by Fénéon as the foundation for the narrative. Gide selected newspaper articles about counterfeiters and fashioned them into a self-reflexive novel. He had contemplated writing the book as a naturalistic novel, but not without examining his own role as the author of such a one Gide 1957, 128. Doubts about the depiction of reality led him to further inquire about untruths. Gide sees the counterfeit gold piece, with its core made of glass and a mere golden surface, as a symbol of the modernist system because the object itself possesses a paradoxical value. Krauss suggests that the worthlessness of money defines the aesthetic value of the abstract, nonreferential, intrinsic value of the modernist artwork. She argues:

[I]f we think of aesthetic modernism itself as severing the connection between a representation (whether in words or in images) and its referent in reality, so that signs now circulate through an abstract field of relationships, we can see that there is a strange chronological convergence between the rise of the inconvertible token money of the postwar economy and the birth of the nonreferential aesthetic sign. Krauss 1998, 6f. She further elaborates that, while the currency was supported by the tangible value of the gold coin, naturalism still presumed a transparency between language and a real point of reference.

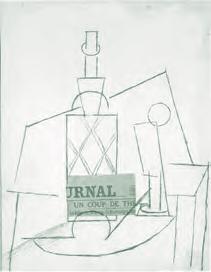

Pablo P icasso’s series of Cubist collages from 1912 and 1913 particularly convey this conflict. In Table with Bottle, Wineglass, and Newspaper from 1912 , fig. 2 Picasso inserts a newspaper clipping from the same year into the abstracting lines that delineate the objects mentioned in the title. Still legible is “URNAL,” and below, “UN COUP DE THÉ,” and another, “La Bulgarie, la Serbie, le Monténégro.” From the puzzling fragment, it can be inferred that the headline of the newspaper Le Journal relates to the ongoing events of the Balkan Wars. In his collages, P icasso is thus expressing his views on the political discussions that were taking place in Parisian cafes. A number of journalists, including André Tudesq, an acquaintance of Guillaume Apollinaire, and René Puaux, documented the political disputes going on in the Balkans, such as that concerning the Battle of Çatalca, northeast of Istanbul, between the Ottoman Empire and those nations about to become entangled in national conflicts. Picasso’s commentary or critique is focused on the depletion of signs, or as Krauss describes it, on the circulation and interchangeability of signs. “Un coup de thé” can be read as an allusion to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, first published in 1897 . Mallarmé dealt with the intricacies of chance, a notion that was destined to become a crucial strategy of avant-garde abstraction. He also had a specific interest in the fusion of language,

2 Pablo P icasso, Table with Bottle, Wineglass, and Newspaper, 1912

Natural capital

The Fiction of Post-Season

The perception of natural capital, encompassing soil, air, water, and all living organisms, as cost-free, inexhaustible, and self-reproducing goods and services is a phantasm rooted in capitalist logics of extraction. Associated with this are devaluation processes of gender-specific and racist labor. In the following chapter, the authors analyze processes of externalization, emphasizing that these do not lie outside the dimension of value circulation but rather constitute an integral part of capitalist relations.

231 Marina V ishmidt Core Absence

245 Markus Wissen Systemic Externalities

257 Gabriele Jutz Absolut Konkret

? hrs: No poster but worked on an image that can be used as part of different publicity materials for the symposium (poster, flyer, program booklet). A strange but enjoyable transition. Finally, an open-ended process, a method of production that has dissolved into work that is differently organized, most likely due to a new demand placed on the product. Funnily enough, a series of posters freed from what it was meant to communicate now becomes a series of images. I take away the logo’s from the Kunst und Wissenstransfer department of Die Angewandte.

? hrs: After some emailing, I meet online with Katarina to discuss the integration of the poster series in the publication as chapter markers and whether the publication’s grid should be derived from the one I used for the poster. I trust Katarina’s process. Jenni sends me the proofread poster-images back. I consider keeping the mistakes and inconsistencies, but it doesn’t make sense in this context, and the work is already done. I wash some clothes by hand while thinking about the title of the series: “(Abstraction and Economy and) Work, and Life”? A bit cheesy maybe, but it’s like that. Sunday evening. After an afternoon spent outside I work a little bit and fantasize about how tomorrow I will do nothing else but peacefully focus on the text I am struggling to write.

Marina v i ShM iDt

Core Absence

In her contribution, Marina Vishmidt analyzes how the devaluation of nature – from nonhuman life to gendered and racialized labor –is seen as a prerequisite for commodification. The economic paradigms for this are forms of the externalization of capitalist modes of production that are based on the devaluation of nature, or labor executed through extraction. Externalization is by no means outside the dimension of the value cycle, but is an integral part of capitalist relations. Building on questions from feminist social reproduction theory and decommodified work in creative industries, Vishmidt demonstrates how value creation relies on externalization.

Marina Vishmidt is a writer and educator. She is Professor of Art Theory at the University of Applied Arts V ienna. She has also taught at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her work has appeared in South Atlantic Quarterly, Artforum, Afterall, Journal of Cultural Economy, e-flux journal, Australian Feminist Studies, and Radical Philosophy, among others, as well as in a number of edited volumes. She is the editor of Speculation for the Documents of Contemporary Art series (Whitechapel/ MIT, 2022 ), author of Speculation as a Mode of Production: Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital (Brill, 2018 / Haymarket, 2019 ), and co-author of Reproducing Autonomy (Mute, 2016 ). She is a member of the Marxism in Culture collective and on the board of the New Perspectives on the Critical Theory of Society series (Bloomsbury Academic). In 2022 , she was the Rudolph Arnheim Visiting Professor in Art History at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

In this essay, I will depart from some of my previous work around art and its link to the politics and epistemology of the exception Vishmidt 2018, 588ff. in order to survey some of the consequences of thinking in terms of the significance of exceptions and externalities to both political ecology and the economic paradigms that have emerged to “value” nature. In imaginaries that range from social reproduction feminist theory to climate investment models, it seems that the relationship between an activity or entity and the capitalist form of value needs to be established in order for that activity or entity to be recognized and protected. At the same time, the creation of exceptions and externalities is seen as fundamental to how capitalist economies and societies function in the critical accounts, from “surplus value” in Karl Marx’s analysis to the production of “cheap nature” Moore 2016, 78ff. and many other contemporary theories that focus on the “ex”s of capital beyond those of exchange and exploitation (extraction, expropriation, etc.). This dynamic of inclusion and exclusion will be assessed from a strategic as well as a theoretical standpoint to see how we can move away from what I would refer to as “accounting” paradigms in emancipatory politics more generally, whether the question is framed in terms of socialist ecological transition or in critical aesthetics. Here, the concept of “accounting” or “accounting for” should be linked more broadly to the question of representation, though that is a question larger than what I am able to specifically engage with here.

Hence, I would like to start by considering the counterintuitive suggestion – if one with clear ecological implications – that externality is intrinsic to the capitalist mode of production in general, and to a phase of it dominated by extraction in particular. The operative category I would like to mention at this point is “waste.”

While we are aware of the process of value being converted into waste as one that is constantly being condensed in time, as captured in terminology such as “fast fashion” and other emblems of hyperconsumerism, political ecology shows us that the construction and devaluation of nature, from nonhuman life to gendered and racialized labor, is a precondition of commodification. Here I am using the term “value” in a dual sense: the everyday sense that derives from neoclassical economics denoting “something which people would pay for” (that is, a marketable commodity), but also the sense in which it is used in Marxist analysis, that is, the value that is constituted by social (abstract) labor producing commodities in a capitalist production process, which comes from surplus value (the difference between the value produced and the wages paid). This is a process which has been analyzed in terms such as “permanent primary (primitive) accumulation,” “accumulation by dispossession,” or the “ecological surplus” Moore 2015, 9ff. talks of, a

concept that is in constellation with the one of “surplus population” that Marx 1981, 343f.; 1976, 781ff. identified as corollary with the capitalist mode of production – as it is necessary to the reproduction of capital as a class relation – and which has lately been brought into focus again in projects looking at racialization and incarceration as the dynamics facilitating the surplussing of populations as well as urban accumulation and commodity frontiers (expulsions, displacements, gentrification, “sacrifice zones”).1

This kind of emphasis on externality as an internal dimension of capital’s value cycle recalls Marx’s observation that the expulsion of labor, and thus the creation of a surplus population, goes hand in hand with the absorption of that labor in the capitalist production processes that generate surplus value. It thus entails a reflection on the relationship between extraction and exploitation, and whether extraction marks a new configuration of absolute surplus value. Likewise, an understanding of how race, and racialization, figure into capitalist social relations can depart from an analysis defined around the three “ex”s, as recently proposed by Chris Chen and Sarika Chandra 2022, 154ff.: expulsion, exploitation, and expropriation, or, as they write: “how capitalism produces relational interlinkages among different domains of social life through a general measure of capitalist value” ibid., 157. This offers a triple lens that also precludes the need for identifying a primary determination in, for example, race or class (or any other social location or identity) while positing a material ground for solidarity. While noting the structural role of this “triple lens” when it comes to understanding both the use and the wasting of labor power and nonhuman natures by capital, we should note another basic principle whereby we would also have to talk about how this triple lens can be applied to, for example, the category of the human itself, and to capital logically. This is the fact that the externality to value is key for the reproduction of value, that appropriation of “free resources” is not only necessary to the production of value that happens through commodification, it may actually be more productive of value than the exchange of commodities. As Liam Campling and Ale jandro Colás 2021, 183 review this point in their Capitalism and the Sea, “appropriation in new commodity frontiers is greater than in existing zones of commodification, allowing for the competitive increase in relative surplus value through productivity gains.” While in this specific analysis the need for an externality to value in order for there to be value manifests in the extraction of aquatic life-forms with value on global markets, it is clear that nonvalued or devalued labor and “resources” – from domestic labor to attention spans and previously exchanged commodities core to many app-based enterprises such as Uber and Airbnb – are also the frontiers of extraction as direct appropriation. By

1 “Commodity frontiers” refers to “sites and processes of the incorporation of resources” in capitalist valorization. See, for example, Beckert et al. 2021, 435ff.; “Over the past 600 years, commodity frontiers […] have absorbed ever more land, ever more labour and ever more natural assets. […] [S]tudying the global history of capitalism through the lens of commodity frontiers and using commodity regimes as an analytical framework is crucial to understanding the origins and nature of capitalism, and thus the modern world. We argue that commodity frontiers identify capitalism as a process rooted in a profound restructuring of the countryside and nature. They connect processes of extraction and exchange with degradation, adaptation and resistance in rural peripheries.”

Exhibition: fig. 1 R. H. Quaytman, קקח Chapter 29, 2015, oil, silkscreen ink, gesso on wood, 62 9 × 101 6 × 2 5 cm. Courtesy of the artist, photo: Adam Reich; fig. 7 Cameron Rowland, Pacotille, 2020, brass manillas manufactured in Birmingham, eighteenth century; glass beads manufactured in Venice, eighteenth century, 103 × 68 × 3 cm. Rental © Cameron Rowland; fig. 11 Heimo Zobernig, untitled, 2012, acrylic on canvas, 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist, photo: Archiv HZ 2012; fig. 18 Monika Baer, untitled, 2007, oil on canvas, 94 × 65 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe; fig. 21 Jenni Tischer, Circle of (Re-)Production, 2023, digital print on textile, ø 1 m. Courtesy of the artist; fig. 23 Hans Haacke, Commemorating 9/11, poster series, 2001 (printed 2002), wheat-pasted, die-cut posters, 45 72 × 60 96 cm. Published by Public Art Fund, New York © 2017 Hans Haacke / Bildrecht, Wien 2024

Eva Maria Stadler: fig. 1 Hilma af Klint, Group X, Altarpiece no. 1, 1915, oil and gold on canvas, 185 × 152 cm. wiki commons: Rhododendrites, photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden, private collection; fig. 2 (and fig. 19 Exh.) Pablo Picasso, Table with Bottle, Wineglass, and Newspaper, 1912, pasted paper, gouache, charcoal, 62 × 48 cm © bpk | CNAC-MNAM © Succession Picasso / Bildrecht, Wien 2024; fig. 3 (and fig. 17 Exh.) Édouard Manet, Nana, 1877, oil on canvas, 154 × 115 cm. Collection Hamburger Kunsthalle, public domain © Anagoria; fig. 4 (and fig. 16 Exh.) Monika Baer, Loot, 2007, watercolor, oil on canvas, 70 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe; fig. 5 (and fig. 12 Exh.): Heimo Zobernig, pages 44, 45 Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 7 9 2019, insert, untitled, 2012, offset print, paper, 46 × 64 cm, digital design: Archiv HZ. Courtesy of the artist; fig. 6 (and fig. 22 Exh.) Jenni Tischer, Diagrammatic Image (a) Llano del Rio, 2023, 160 × 200 cm, acrylic, oil, pencil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Krobath, photo: Rudolf Strobl

Christina von Braun: fig. 1 Mike Winkelmann (aka Beeple), Everydays: The First 5000 Days, 2007–2021, five thousand digital drawings, dimensions variable, non-fungible token (jpg), 21,069 × 21,069 pixels; fig. 2 The weighing of ring money against livestock, Egyptian mural from Thebes. Creative commons; fig. 3 Image plate 73, in Hortus Eystettensis, edited by Basilius Besler, Nuremberg, 1613, p. 234, Vern Ordo 4, fol. 5. Collection: Digitale Sammlungen der Universitätsbibliothek Eichstätt-Ingoldstadt, public domain; fig. 4 Queen Elizabeth II tours the gold vault during her visit to the Bank of England in central London, December 13, 2012. Press photo © Eddie Mulholland/ Daily Telegraph/PA Archive/PA Images; fig. 5 Pallas Athena and her symbol, the owl, on a silver tetradrachm of Athens,

454–404 BC © Classical Numismatic Group, public domain; fig. 6 Top: six rod-shaped oboloi; bottom: one drachma depicted as a handful of oboloi © Odysses, public domain; fig. 7 Bitcoins © 2013 Zach Copley, creative commons; fig. 8 Cowrie shells, 2022 © Vidya Pmysore, public domain; fig. 9 Ephesian Artemis, 125–175 AD. Collection: Ephesus Museum Selçuk, Turkey © 2011 Carole Raddato, creative commons; fig. 10 The evolution of the letter Alpha from the bull’s head to the modern A, creative commons; fig. 11 Patriarch John VII Grammatikos erases an icon of Christ in the shape of a coin, in Chludow-Psalter, ca. 850–875, folio 67r. Collection: State Historical Museum Moscow, public domain; fig. 12 Two-pound coin commemorating the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the DNA double helix, 2003. Collection: Münzkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin © Reinhard Saczewski, public domain

Blaise Kirschner, David Panos: fig. 1 Blaise Kirschner, David Panos, The Last Days of Jack Sheppard, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, 2009, exhibition view; figs. 2–8 (and figs. 14, 15 Exh.) Blaise Kirschner, David Panos, Ultimate Substance, 2012, HDV video, 34 min, still. All images © Blaise Kirschner, David Panos Patricia Grzonka: figs. 1–10 (and fig. 9 Exh.) © 2003 Elmar Bertsch

Christian Scherrer: fig. 1 Theo van Doesburg, scheme of the progressive pictorial abstraction of a cow (“Ästhetische Transf iguration eines Gegenstandes”), published in Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst, Albert Langen Verlag, Munich 1925, p. 45 © Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin; fig. 2 Packaging of the cheese brand La vache qui rit (Fromageries Bel) from the 1920s © La Maison de La vache qui rit; fig. 3 Paulus Potter, The Young Bull, 1647, oil on canvas, 235 5 × 339 cm. Collection: Mauritshuis, Den Haag, public domain; fig. 4 Goddess Hathor in the form of a cow, licking the hand of Queen Hatshepsut (Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Chapel of Hathor), ca. 1470 BC, painted relief in limestone, Deir el-Bahri, West Thebes (Upper Egypt) © akg-images / François Guénet; fig. 5 Luke the Evangelist with Bull, fol. 1 v in: Codex Aureus of Lorsch, early ninth century AD (before 814), illumination on parchment. Collection: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 50 © Peter H. Feist, creative commons; fig. 6 Aison, Theseus killing the Minotaur, ca. 430 BC, painted kylix. Collection: Muséo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid © Marie-Lan Nguyen, public domain; fig. 7 Masaccio, Adoration of the Magi with Portrait of the Donor, 1426, 22 3 × 61 7 cm, oil on wood. Collection: Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, public domain; fig. 8 Theseus as liberator of the Cretans (House of Gavius Rufus, Pompeii), 45–79 AD, 97 × 88 cm, fresco. Collection: Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples,

public domain; fig. 9 Aelbert Cuyp, River Landscape with Cows, 1645–1650, 68 × 90 2 cm, oil on wood. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, public domain; fig. 10 Paul Gauguin, Marine avec vache, 1888, 72 5 × 61 cm, oil on canvas. Collection: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, public domain; fig. 11 Pablo Picasso, Bullfight, 1934, 54 × 73 cm, oil on canvas. Collection: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid © Succession Picasso / Bildrecht, Wien 2024; fig. 12 Vassily Kandinsky, Several Circles, 1926, 140 3 × 140 7 cm, oil on canvas. Collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2018 Tulip Hysteria, creative commons; fig. 13 Marcel Broodthaers, Le Corbeau et le Renard, installation view at Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp, March 7–31, 1968 © Anny de Decker / Succession Marcel Broodthaers / Bildrecht, Wien 2024; fig. 14 Marcel Broodthaers, La vache qui rit (installation view), 1968, 2 5 cm × 11 cm each, eight printed cardboard boxes, manual inscription, letters cut out of photo canvas. Private collection © Niek Hendrix / Succession Marcel Broodthaers / Bildrecht, Wien 2024; fig. 15 Marcel Broodthaers, Maria, 1966, 112 × 100 × 12 cm, dress, hanger, and printed shopping bag (advertising Swiss gruyère cheese) with eggshells, on primed canvas © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence; fig. 16 (and fig. 20 Exh.) Rosemarie Trockel, Pattern Is a Teacher / Le motif est maître, 2021, design for the limited collector’s edition box of Lab’Bel, commemorating the centenary of La vache qui rit © Lab’Bel / Bildrecht, Wien 2024; fig. 17 Newspaper advertisement for La vache qui rit from the 1930s © La Maison de La vache qui rit

Brenna Bhandar: fig. 1 Dierk Schmidt, Tableau 2, Conférence de Berlin, 2007, close acrylic, silicone on canvas, oil on foil, table with accompanying text materials, historical documents and legal material.

Photo: Andreas Pletz, courtesy of the artist and KOW, Berlin © Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, VG-Bild Kunst; fig. 2 (and fig. 3 Exh.) Dierk Schmidt, Tableau 11, Oturupa, Okahandja, 2006, acrylic, silicone on canvas, oil on foil, table with accompanying text materials, historical documents, and legal material.

Photo: Andreas Pletz, courtesy of the artist and KOW, Berlin © Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, VG-Bild Kunst

Sven Lütticken: fig. 1 US president Barack Obama in front of Mondrian’s Victory Boogie Woogie (1944) on the occasion of the Nuclear Security Summit in The Hague, March 25, 2014. Press photo © ANP Foto; fig. 2 Paul Chan, Volumes, one from a series of more than one thousand paintings made out of dismantled book covers and the texts that complement each painting, 2012 © Paul Chan; fig. 3 Natascha Sadr Haghighian, “Dear Artfukts, Look at my Curve: A Report to an Academy,” 2013, cover © Natascha Sadr Haghighian; fig. 4 (and fig. 13 Exh.)

Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann, Updating Page 62/ Bitcoin, 2019, from the ongoing series Atlas (2003–) updating Otto Neurath’s Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft.

Bildstatistisches Elementarwerk (1930) © Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann

Karel Císař: fig. 1 (and fig. 2 Exh.) Florian Pumhösl, Battle of Manila Bay (Turning Maneuvers), 2005; fig. 2 Florian Pumhösl, Modernology (Triangular Atelier), 2007, installation view; fig. 3a Florian Pumhösl, Reliéf (Rossman), 2010; fig. 3b Florian Pumhösl, Relief (Sutnar), 2010; fig. 4 Florian Pumhösl, Fliegender Händler, 2011 All images © Florian Pumhösl

Denise Ferreira da Silva: fig. 1 Otobong Nkanga, In Pursuit of Bling, 2014, singlechannel HD video 11:59 min © Otobong Nkanga, courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Jenni Tischer: fig. 1 Albrecht Dürer, Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, ca. 1600, woodcut, 7 5 × 21 5 cm © akg-images; fig. 2 (and fig. 8 Exh.) Shrew, vol. 3, no. 9, December 1971, special issue: Nightcleaners, cover for the magazine of the Women’s Liberation Workshop by Mary Kelly © Cover design: Mary Kelly; fig. 3 (and fig. 6 Exh.) Adrian Piper, Parallel Grid Proposal for Dugway Proving Grounds Headquarters, 1968, two typescript pages; ink and colored ink on fourteen sheets of paper; architectural tape on acetate over ink on thirteen photostats; and ink on cut-and-pasted map, mounted on colored paper. Twentyfive sheets each 21 6 × 27 9 cm; two sheets each 21 6 × 32 2 cm; and three sheets each 27.9 × 21.6 cm. Detail: #11 Collection Beth Rudin DeWoody © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin; figs. 4, 5 (and f igs. 4, 5 Exh.) Cauleen Smith, The Grid, 2011, single-channel HD video, surround sound, 15:13 min, still © Cauleen Smith

Sabeth Buchmann: fig. 1 Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporu, 1928, oil on canvas, 85 × 73cm. Collection MALBA, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires © Tarsila do Amaral Licenciamentos; fig. 2 Blinky Palermo, Stoffbild, 1970, 200 × 70 cm, dyed cotton on nettle. Collection: Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main / bpk © Bildrecht, Wien 2023; fig. 3 Hélio Oiticica, B16 – Bólide – Box 12, “Archeological,” 1964–1965, polyvinyl acetate and vinylacrylic paint with earth on wood structure, nylon net, corrugated cardboard, mirror, glass, rocks, earth, and fluorescent lamp, 37 × 131 2 × 52 1 cm. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York © Cesar and Claudio Oiticica; fig. 4 Lygia Pape, Book of Creation, 1959–1960, artist book with sixteen unbound pages, gouache on board, paper, and string, each: 30 5 × 30 5 cm © 2023 Projeto Lygia Pape; figs. 5a, 5b Lygia Pape, A mão do povo (The Hand of the People), 1975, single-channel digital video, transferred from 16 mm film, black and white, sound, 10 min, still. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © Centro Técnico

Audiovisual; figs. 6 © Falke Pisano, The Value in Mathematics, Negotiations in exchange, 2015, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

R. H. Quaytman: fig. 1 R. H. Quaytman, installation at American Academy Rome, 1992; fig. 2 R. H. Quaytman, Good Morning to You, 1994, oil, gesso on wood, 58 4 × 58 4 × 1 9 cm; fig. 3 R. H. Quaytman, Replica of Kobros Spatial Composition #2, 2000, silkscreen ink, gesso on wood, 62.9 × 101.6 × 2.5 cm; fig. 4 R. H. Quaytman, The Sun, Chapter 1, Spencer Brownstone, 2001, installation view. All images © R. H. Quaytman

Eva Kernbauer: fig. 1 (and fig. 10 Exh.)

Lorna Simpson, The Park, 1995, serigraph on six felt panels with two felt text panels, overall: 172 7 × 203 2 cm, each image panel: 86 4 × 57 2 cm © Lorna Simpson, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth; fig.2 Andy Warhol, Large Sleep, 1965, 168 9 × 123 8 × 23 5 cm, screen print on Plexiglas © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Bildrecht, Wien 2023; fig. 3 Sol LeWitt, Wall Structure, White, 1962, 113.8 × 113.8 × 53.3 cm, oil on canvas, painted wood. Courtesy of Craig F. Starr Gallery, NY, licensed by Bildrecht, Wien 2023

Clemens Apprich: fig. 1 © Randall Munroe, Machine Learning, 2017, web comic; fig. 2 Principal Component Analysis vs. Factor Analysis © Clemens Apprich

Gabriele Jutz: fig. 1 absolut konkret, University Gallery of the Angewandte, 2022, exhibition view, installation by Katrin Brack, Konrad Brack. Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21, 1921–1923 © All rights reserved by the artists / courtesy of Light Cone, Paris, photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez, kunst-dokumentation.com; fig. 2 absolut konkret, University Gallery of the Angewandte, 2022, exhibition view, installation by Katrin Brack, Konrad Brack © Konrad Brack; fig. 3 absolut konkret, University Gallery of the Angewandte, 2022, exhibition view, installation by Katrin Brack, Konrad Brack. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez, kunst-dokumentation.com; figs. 4, 5 absolut konkret, University Gallery of the Angewandte, 2022, exhibition view, installation by Katrin Brack, Konrad Brack. Oskar Fischinger, Wachsexperimente, 1921–1926. Courtesy of the Center for Visual Music, Los Angeles. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez, kunst-dokumentation.com

Every effort has been made to locate and list all copyrights. If there is any missing or inaccurate information, please contact the editors.

Acknowledgments

Various people and institutions have contributed to the realization of this book. Our thanks go first of all to the authors for their instructive essays and for their care and patience in revising their papers and to the artists for supporting this book with their works, especially to Monika Baer, Otobong Nkanga, Adrian Piper, Falke Pisano, Cameron Rowland, Cauleen Smith, and Heimo Zobernig. We would also like to thank Petra Schaper Rinkel, Rector of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, as well as Gerald Bast, former rector, for their support of the symposium, the lecture series, and the publication. This book would not have been possible without the attention to both the details and the big picture paid by Stefanie Schabhüttl, Katharina Holas, Katarina Schildgen and Paul Gasser, Arturo Silva, Lian Rangkuty, and Belinda Zauner. Furthermore, we would like to thank Christina Androsch, Quirin Babl, Marei Buhmann, Nikita Dhawan, Christian Egger, Sebastian Huber, Roswitha Janowski-Fritsch, Stefanie Kitzberger, Yona Schreyer, Anja Seipenbusch-Hufschmied, and many others for their valuable conversations and for all their support in organizational, content-related, and personal matters.

Special thanks go to the publishers of the books in which some of the texts originally appeared:

“Always Be Filtering” by Clemens Apprich first appeared as part of the 4th Media Studies Symposium of the German Research Association (DFG) in 2022 under the title “Filter” in Filter. Publication of the 4th Media Studies Symposium of the German Research Association, edited by Ralf Adelmann and Tobias Matzner. Bonn: DFG.

“Blacklight” by Denise Ferreira da Silva was first published in 2017 in Luster and Lucre, edited by Clare Molloy, Philippe Pirotte, and Fabian Schöneich, 245–255. London: Sternberg Press and Portikus (Frankfurt), in collaboration with KADIST Art Foundation (Paris/San Francisco) and MHKA (Antwerp).

“Concrete Abstraction – Our Common World” by Sven Lütticken was first published in 2019 in In the Mind but Not from There: Real Abstraction and Contemporary Art, edited by Gean Moreno, 149–176. London/ New York: Verso Books.

“Sell Everything, Buy Everything, Kill Everything” by Blaise (formerly Anja) Kirschner and David Panos first appeared in 2014 as part of a publication series by the cx centre for interdisciplinary studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich in Power of Material/Politics of Materiality, edited by Susanne Witzgall and Kerstin Stakemeier, 208–218. Zurich/Berlin: diaphanes.

“Systemic Externalities: On the Socioecological Costs of the Capitalist Mode of Production” by Markus Wissen first appeared in German in 2022 as “Systemische Externalitäten. Über die sozial-ökologischen Kosten der kapitalistischen Produktionsweise” in Das Klima des Kapitals. Gesellschaftliche Naturverhältnisse und Ökonomiekritik, edited by Valeria Bruschi and Moritz Zeiler, 214–228. Berlin: Dietz.

The original texts have been slightly adapted for the volume at hand.

Imprint

Eva Maria Stadler and Jenni Tischer (Eds.)

This publication results from the lecture series and symposium Abstraction & Economy, University of Applied Arts Vienna (April 28–30, 2022), accompanied by the exhibition absolut konkret (curators: Gabriele Jutz and Eva Maria Stadler; exhibition design: Katrin Brack and Konrad Brack), University Gallery of the Angewandte (March 12–April 9, 2022).

With contributions by Clemens Apprich, Brenna Bhandar, Christina von Braun, Sabeth Buchmann, Karel Císař, Denise Ferreira da Silva, Patricia Grzonka, Gabriele Jutz, Eva Kernbauer, Blaise Kirschner and David Panos, Leigh Claire La Berge, Sven Lütticken, Falke Pisano, R. H. Quaytman, Christian Scherrer, Eva Maria Stadler, Jenni Tischer, Marina Vishmidt, Beat Weber, and Markus Wissen

Concept: Eva Maria Stadler and Jenni Tischer

Project Management “Edition Angewandte” on behalf of the University of Applied Arts Vienna: Stefanie Schabhüttl

Content and Production Editor on behalf of the Publisher: Katharina Holas, Vienna, Austria

Image and reproduction rights: Marei Buhmann, Quirin Babl, and Jenni Tischer

Translation into English: Lian Rangkuty and Jonathan Quinn

Proofreading/Copyediting: Arturo Silva and Belinda Zauner

Design: Katarina Schildgen & Paul Gasser

Cover: Falke Pisano, poster series (Abstraction and Economy and) Work, and Life, 2022, and Katarina Schildgen

Printing: Holzhausen, the book-printing brand of Gerin Druck GmbH, Wolkersdorf, Austria

Paper: Nautilus Classic 80, 120, and 250 gsm

Typefaces: Werksatz and ziGzaG

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023947033

Bibliographic information published by the German National Library

The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in databases. For any kind of use, permission of the copyright owner must be obtained.

ISSN 1866-248X ISBN 978-3-11-136634-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-137134-4

© 2024 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin / Boston

www.degruyter.com

� www.dieangewandte.at/ KunstundWissenstransfer Kunst und Wissenstransfer

University of Applied Arts Vienna Art and Knowledge Transfer Georg-Coch-Platz 2 1010 Vienna / Austria