Prosody

Welcome to the inaugural edition of Prosody, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin’s official student-run literary and arts magazine! As we approach the third anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been reflecting on the significant hardships and burnout that the medical community has endured. It is more important than ever to promote resiliency, and we feel that the humanities offer a unique opportunity to engage in self-expression and reflection. A 2020 report from the AAMC recognizes that engagement with the arts decreases burnout and compassion fatigue in addition to enhancing empathy, altruism, and clinical observation and communication skills. Through Prosody, we not only hope to showcase the creativity of our colleagues, but to provide an outlet for our community to share their experiences through artistic expression. In doing so, we aim to better understand the intimate connections between patient and physician, to seek the meaning of medical practice for both the individual physician and collective profession, and to promote discourse on complex, multifaceted components of healthcare.

A common theme interwoven through this first issue is facing mortality and loss in both personal and clinical settings. During clinical rotations, we and our fellow classmates often find ourselves observing the delicate margin between life and death. For some of us, the experience echoes past memories. For others, the experience opens a conversation into the purpose of medicine. We invite you to listen in on our internal dialogue as we embark on our journey through medical education. Join us in a reflection, celebration, and elegy of human emotion for our first edition!

Executive Board

Editors-in-chief: Victoria Siu, Alexis de Montfort Shepherd

VP of Internal Affairs: Evelyn Syau

VP of Design: Sahana Prabhu, Tammy Spear, Emily Yan

VP of Submissions: Logan Muzyka, Daniel Ramirez

Readers

Vi Burgess, Lundyn Davis, Karen Jimenez, Aiza Kahlun, Natalie Malluru, Brandon Nguyen, Imane Ridouh, Tammy Spear, Catherine Stauber, Ria Sur

Website Editor Jackie Castillo

Faculty Sponsors

Steve Steffensen, MD, Thomas Vetter, MD

Advisory Board

Phil Barrish, PhD, Carrie Barron, MD, Hannah Jane Collins, Craig Hurwitz, MD, Stephen Sonnenberg, MD, Swati Avashia, MD, Richard Peters, MD, Imelda Vetter, MLIS

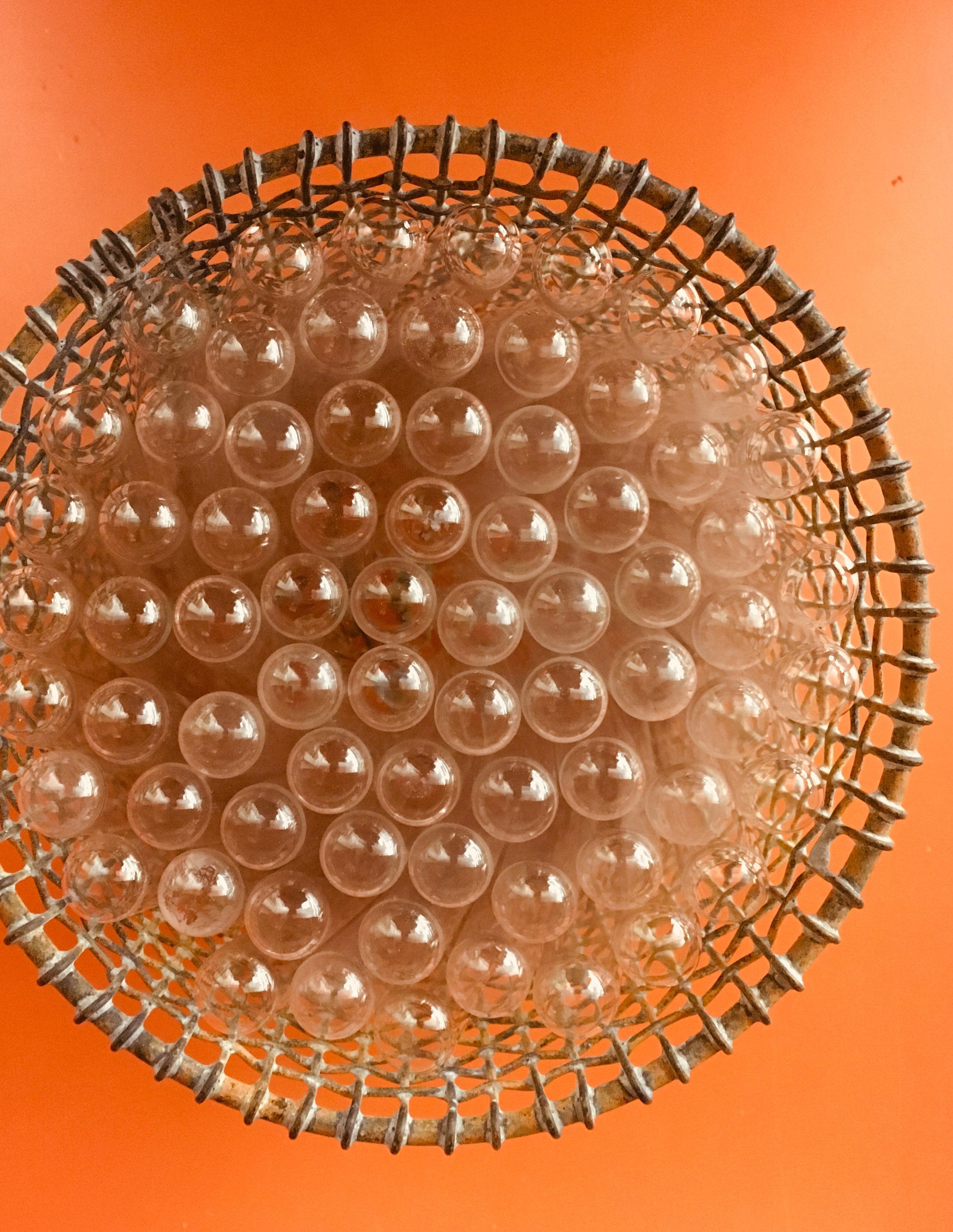

Cover & Table of Contents: Barrels & Virion by William Austin

Victoria Siu, Alexis de Montfort Shepherd, Co-Editor-in-Chief Co-Editor-in-ChiefThe works published in this journal were selected based on literary and artistic merit and do not reflect the views of The University of Texas at Austin, Dell Medical School or the editorial staff.

In the dark a noise is heard and feared. In the day the creature known and revered. Its claws removed by day and teeth but sunlight skies, given again by the moon and her dying cries. This is true power to be feared yet never respected. Power is to do that which is unexpected.

Keith Messenger, DO

Keith Messenger, DO

A 20 year old female was admitted to my inpatient service for BMI Anorexia

Nervosa (AN) with severe range BMI for weight gain and potential refeeding syndrome management. She had a history of previous hospitalization as a child for this. Initially, she demonstrated intelligence and insight into her disease, however over subsequent days to weeks it was clear there was a significant barrier to her prognosis as she continued to lose weight due to declining and hiding food. She also continually declined going to an inpatient eating disorder facility for her condition and it was clear that if this disease was not properly managed, she would likely succumb to it sometime in the future due to the complications of a severely low BMI. At some point, we had to consider whether she had capacity to decline these treatments; however, after discussions with psychiatry it was deemed she did have capacity. This was a rather uncomfortable conversation for our team, as is so commonly in eating disorders, nothing is black and white. As an adult, she had the right to decline interventions, however she was still very young, and we were concerned that if we didn’t intervene, we may be letting a disease eventually take her life. It became very clear that there was a huge gap between the care a patient with AN receives as a child at a children’s hospital where the parent can intervene, and a patient who is an adult and can make medical decisions for themselves.

AN is a notoriously difficult illness to treat and has the highest mortality of eating disorders with poor lifetime outcomes. There is a very obvious difference in how this disease is managed in a child versus an adult which is discussed in an article by Winston, et al 2011, titled “The same but different? Treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents and adults”. They state that child and adolescent health services differ from adults in therapeutic approach and the availability of specialist treatment. Further, they state that child treatment services are typically based around family interventions which help parents take control of their child’s eating and patients are encouraged to externalize the illness. However in adults, treatment tends to be based around individual therapy and the onus is on the patient to take personal responsibility for change. This transition of care type upon entering adulthood can be difficult for providers and the patient as it is an abrupt change in enforcement and psychosocial interventions related to the illness. In this patient’s case, we dealt with this difficult transition of care and it left us constantly questioning whether we were giving her the treatment interventions that would best help her.

As a child, she received typical AN management that you would expect from a children’s hospital which includes very strict rules and regimens for providing care including weight gain goals, daily caloric plans, bedrest if not meeting blood pressure or orthostatic criteria, exercise and movement restriction, and requirements to finish each meal. If treatment continues to fail or the patient continues to decline food intake, more drastic interventions such as a nasogastric tube can be used. All of this can be done against the desires of the child as the parent can make the medical decisions for these treatments. However, once the patient is 18 years old and their own health proxy, it is not possible to provide this level of care against their wishes. Since most of the treatment is structured around strict regimens to enforce habit and change regarding perceptions of weight and food, failure in an adult patient is not uncommon. Often, the patient’s mind will fight every opportunity it can to gain weight despite their insight and best interests. This has often been described as an inner voice and can dominate the patient’s underlying wishes to get better.

These strict treatment regimens bring up several ethical questions and dilemmas such as whether the austerity is too paternalistic, a prevailing mindset of medicine’s past which is rightfully getting phased out over time. In medical school and residency, we are taught that the patient always has the right to manage their own health and their involvement is paramount to success. However, in this case, this disease will kill her if she does not receive the treatment which her inner voice will almost always find a way to oppose. Our inpatient team frequently felt uncomfortable in attempting to correctly manage this patient’s condition as she was barely out of the range of being a child and still had childlike thinking and tendencies, but was her own medical proxy being an adult. We attempted to initiate part of the typical strict regimens that would be performed at a children’s hospital, but frequently ran into issues regarding whether this was hurting the physician-patient relationship and whether this was an appropriate transition of care from family interventions and strict regimens to the individual patient taking responsibility for treatment.

There are parallels with AN and several other diseases medical providers encounter frequently. For example, a patient addicted to drugs or alcohol is chronically damaging their body and depending on the extent could ultimately be their demise, but we don’t remove their capacity to not use alcohol or drugs unless the patient meets criteria for psychiatric hospitalization. A similar situation is seen commonly in a large percentage of patients in primary care offices: the patient with diabetes, hypertension, or CAD who continues to decline engagement of lifestyle modifications. Again, we would never think to take away capacity to eat the foods they want or force them to engage in physical activity. However, where is the line drawn when psychiatric illness comes in to play in the form of a voice telling you to do or not do these things which can jeopardize your health to the point of death? It puts the provider in a very difficult predicament.

In the end, it was deemed by our psychiatry team that this patient did not have capacity to decline nutritional supplementation and the patient’s medical proxy, her mother, ended up declining further interventions.

There is no simple answer...

There was also the consideration of whether a feeding tube and strict refeeding regimens would even benefit her long term as she had done this in the past and continued to revert to her old patterns of food restriction. Eventually, the patient was discharged against medical advice with the hope of strong outpatient follow up to manage this crippling disease. However, the only “cure” would be to have patient participation with psychotherapy to rewire her perceptions of food and body. It was unclear if she would ultimately follow along with this outpatient treatment plan. But without patient participation, how can this disease be treated? Is there therapeutic benefit to removing these patient’s rights to manage their own health or does the voice inside their head prevent them from ever getting better despite their best efforts?

There is no simple answer and likely won’t be until we better understand the pathophysiology of this disease to create improved treatment options. In the meantime, there is unfortunately a small proportion of our population being enslaved by their inner voice to starve their bodies of the life they need, a life with food.

blood drips

I can’t stop thinking about iron about the stars that died in galactic glory just to end up in our veins or on the floor

it’s a brutal thing to witness, saving a life

when really we’re just bearing witness to death always there in the corner, watching solemnly our futile efforts to stave it off

it’s that chilling moment of silence when the trauma bay is holding its breath, before someone whispers, time of death, that we feel closest to it, to the ending and we feel closest to him.

his body, laid bare on the table I can’t stop thinking about his shoes

I wonder where they carried him before he ended up in our arms and I remember he was a person too

they say you get used to it, but I can’t stop thinking about how did he end up like this, become so reduced to anatomy, reduced to another day on the job.

it’s true, you never forget your first I can’t stop thinking about the stars meeting death millions of years before us. I hope he has gone wherever they are, I hope he’s not alone.

First, death was a pet frog. He was floating in the water with his pale belly up and ruptured. I wondered if he ate too many food pellets.

Then, death was my great grandmother. I thought she was sleeping on the hospital bed, but my father was crying. Her hands were oddly cold her lips were slightly open, like she was about to tell me to eat one of her egg tarts.

Stillness is the lack of movement. Is the pause that keeps going and going until it is unsettling until it becomes A full stop.

Death was just stillness until a late 2018 night The patient was coding Nurses scurried in and out of his room like mice in hushed voices

But his breaths were loud He opened his mouth and inhaled And exhaled

And inhaled

Crashing waves just going and going

No family members present. Just fought breaths, hushed voices,

And perhaps a girl who witnessed but did not understand death

Inhale

Exhale

Inhale

Pushing and pushing

Muscles twitching. Lungs gasping. From the cry of birth till the last breath of death. Life did not go silently into that dark night.

Peace in her gray eyes

She held my hand and we wept

Thank you and goodbye

Christian Shannon

POPPIES, Emily Yan

Christian Shannon

POPPIES, Emily Yan

First envision the way her eyes hang

As immotile as sleeping bats

In the caves where seven bones collide

Sphenoid,frontal,zygomatic,ethmoid…

You strain to remember the missing three

A factoid learned in anatomy

Where sharp-eyed professors pinned parts

On cadavers freshly frozen in formaldehyde

Now imagine cachexia as onomatopoeia

Plump limbs replaced by brittle bones

That grind together like rusty gears

Yourmindspillswithstatisticsasuseless...

As her sky-blue hospital gown that slips

Off her small shoulders and you recall Mother’s ring on a child’s finger

Then picture how it might all end

Palliate, from the Latin pallium, to cloak in morphine until her breathing slows

A tangle of rosary caught in her gaunt hand

While her daughter swims through the Fractal of her engulfing grief and…

Wherewereyou,studentdoctor?

The ringing of the telephone in a dark on-call room always startled me, even far into my internship (after I had stopped sleeping with my shoes on).

“Hello” I answered dully, my heart pounding.

Dr. Tierney?”

“Yeah.”

“I have an IV that needs re-starting.”

“Who?”

“24B - Bridgewater.”

“The quad?”

“Yeah.”

My heart sank. Donny Bridgewater had a C6 transection that he acquired in an automobile accident. He had some movement in his atrophic arms, but their greatest value to us was as IV sites for treating his innumerable urinary tract infections and decubiti. Every house officer on campus had treated him at some time or another. His veins had been so abused by IVs that starting a new one was exceedingly difficult.

“What’s he getting?”

“D5 half-normal saline.”

Hope! If he were only getting fluids, perhaps the IV could wait until morning!

“...and tobramycin.”

Groan! No way out. “Okay. I’m coming.” I kicked off my blanket, sat up, and pulled on my shoes. My roommate rolled over.

“Bilgewater?” [I always wondered if the cynical housestaff and students even recognized the reference to Huckleberry Finn.]

“Yeah.”

“Good luck.” He meant it.

My walk to the ward was punctuated by yawns. After picking up an IV tray at the nurse’s station, I walked to his room and turned on the grossly inadequate light, a single yellowed bulb at the head of his bed.

“Hi, Donny. I’m Dr. Tierney. I’m here to re-start your IV.” He glanced up, lanced me with an expression that was a mixture of disdain and indifference, then closed his eyes and ignored me. As I cleaned his atrophic, contracted arm, I noticed a wire contraption attached to his hand. After a few moments, I realized that it must hold a pen or pencil. A look to his bedside tray-table revealed the pencil and a sheet of paper covered with barely legible scrawl:

Quiet and cold

Stone and unyielding Spinning and stark Whispering orb

Old silent singing Blinding dark crescent Metronomes dark Unending chord

Been and begun Feeling and giving Withered and young Furrows, dead fields Wisdom unhurried Order in chaos Refrains but unsung Taking, she yields

I was shaken. I could not reconcile his physical incapacity with the breadth of his vision and the depth of his feeling. Of the two of us, who was more handicapped? Donny and his quadriplegia or me, mired in an exhausting internship that precluded all other life activities? Whose mobility was more limited? Which one of us was mired in the mud? Whose numbness was greater?

In a small, dark room amidst terror, hope, and pain, his angry spark of defiance and feeling had blinded me in my weary performance of routine tasks. I realized that I was a nameless, annoying, meaningless detail in his life.

Later, as I sat down heavily on my on-call bed and pulled off my shoes, my roommate rolled over again.

“Get it?”

“First stick.”

“Lucky.”

“Yeah.”

Evelyn Syau

Code Blue, Code Blue, The intercom blares. A flurry of movement, A husband confused.

The clock – it’s ticking. Who to save first?

Inside, there’s only Blood blood and blood.

A cut deft and sure A newborn – silent. Out, whisked away The clock – it’s ticking.

Keep going, stop The blood, hold it There, steady hands. The clock, it’s ticking.

Hours pass – finally –Breathe, it’s over. They’re safe, both of them, Mother and daughter.

The clock still ticks, but Its meaning is different. It counts now fond moments, Spent with friends and loved ones.

Placental abruption, Devastating hemorrhage. A definitive cut that Allowed me, to be.

Emily Yan

Be still

Be whole

Be beholden

To all

That draws You in

To all

That speaks To you

And wander off

Between the Sunlit trees

Through the Sparkling Autumn stream

Pause

Be still Take care

Some days in the hospital feel steeped in futility. On internal medicine I see “compassionate” dialysis, pushing patients to the brink of death again and again and first a foot amputation, then below the knee, then above the knee. In both cases, the sinking feeling that you will be seeing this patient again very soon. But more than any other specialty I have come across, a sense of hopelessness permeates conversations about neurology. Before starting my rotation, I heard students, residents, and attendings in other specialities talk about how much of neurology was accompanying patients as they slowly deteriorate. Neurology was not the specialty where you helped people get better. It was one of prognosticating whether a patient would wake up from a coma, or gently encouraging stroke patients as they tried to recover some motor strength through many long months of physical therapy.

My very first stroke case of a woman in her early forties, who had come in completely hemiplegic with left sided gaze preference and aphasia. It was a textbook L MCA stroke. She was a candidate for both tPA and a thrombectomy, and was in the OR within an hour of presentation. The next morning, I peek into her room to find her sitting cross legged on her bed scrolling her phone with one hand and nursing a cup of tea in the other hand. This is an odd scene. She has no hemiplegia, no gaze preference, no aphasia, no obvious deficits. And after a conversation and a thorough neuro exam, no subtle deficits either.

Again and again, I heard how this was not a standard stroke case. Anything but. She was too young. She presented quickly. She had no risk factors. Her recovery was unique. Patients did not make complete recoveries overnight. Her success is an abnormality.

I hold on tight to this stroke case. My phone background is a live image of her thrombectomy. Every sick patient I see, I think back to the complete recovery of that forty year old woman. In a healthcare system that is already so broken, I look for windows of hope. I walk into every patients room and remind myself to expect success. Success is not an abnormality.

Diggin down to bedrock thinkin he’ll come out the other side

A better man

Thought he coulda stopped her comet from losing stars to time but she wouldn’t Slow down

He knows that life

Is complicated

So the women sing oh

Why ya lookin at the ground?

There ain’t nuthin for you there

May the lord afford you

Something to fill the void

From his lips is a sigh

Vacant look in his eye

Looked too long at the sun

Now he’s a bumma

He’s a sight on the run

Does he know he weighs a ton

Broke her back on a crack

No fix, don’t bother

And oh woah woah

There’s no fix, don’t bother

So keep your hands on the bottle

Staccato free like her laughter

Narrower, tortured, but thoughtful her eyes

Caught up and dealt a bad hand to her sire

Models, and heroes, ancestors are liars

Ignorance, strength, and our norms all conspire

Hold me close don’t let me go

Gawdy spots on the sun

Craters from her soul

She’s upset and she’s on it

Pen in hand yeah she’s honest

Fools will turn and let her spillah

Black beans until they fill up the page

Little girl trapped in a mother

Little fiend in her ear finds her when she’s under the covers

Can you hear the screams of her brothers

Begotten by the love of the father

He knows not about the spots on the sun

Oh she made em with her soul like a gun

To blast her away from it all

To be safe from it all

I can see it in her eyes I’m telling you all

They’re craters from her soul

Diggin down to bedrock thinkin we’ll come out the other side

Better men

And she moves on The only rider on the train

The conductor says ma’am, it’s time to get off It’s the last stop

She looks up

Can you tell me sir, where am I?

And how get home?

How do I get back?

Thomas Varkey, MD

Thomas Varkey, MD

The morning sun rises and my feet hit the floor. Angst and pain encompass my thoughts. “They need me”. Fear of failure, ineptitude, struggle, and inability to know it all - “why am I like this?” My mind swarms as I shower under the warm water. The numbness of the day’s nuance continues to baffle me. Finally the moment of clarity “They’ve asked for my help, who am I to say they are wrong to ask for my help? Who am I to say no?” The scrubs feel familiar as I walk through the halls. I sit on his bed, the little man crippled. With a divine voice brought forth in that sacred moment of care (is it even mine anymore? It sounds like me, but different) - “What brings you in today sir? How might I help you?” And again I feel whole.

“It’s an alto sax tone that never goes away.”

“Well, mine sounds like the bass line of an electric guitar.”

“All we need is a drum line.”

[laughter]

“I miss hearing pitches.”

I can feel the worm nibbling. There are periods of complete silence, but I give my preference to the Drone. It’s numbing—the monotone in the back of my head. I want to turn the Drone into a Gregorian chant. It is calmness at first, but all night long? Does it ever stop? This cochlear that my doctor likes to talk about, let’s file it away into the library of disappointment. Apathy follows my brain’s dead husk.

“Say again?” is my new favorite catchphrase. The cities within and the voice of what I might have been falls to returning silence. Down deep, I hear bone. Change is a sentence following death. Weightlessness. I am unraveling and the Drone hovers overhead.

Bodies tend to stop at an image. The field of mutilation extends indefinitely, but once you remove a leg or arm, you perceive dismemberment. I forget everything, therefore “I must be broken.” The mirror reveals and the body accommodates. The body is a parchment of ancient music I keep waiting to hear. I have not dismissed myself, Janus-faced.

Water is also a body and we are all drowning. The Drone that hums in the base demonstrates its newness. Mostly it’s just us and the tympanum of limit. The long Drone stays underwater for the fraying clamor, now too robust. I give preference to the Drone, inflection is now distrust. Tinnitus is a phantom standing at the door. When objects fall away, they displace water in cochlea. You who were once body, now mannequin. The formerly person. Light falls equally between human and dwarf.

There is panic among the follicles upon naming. Words. I take up typing again and the screen shatters disconnect between hearing and silence. Associate words and rethink poetry. I who was once a whole name. The missing arm and its ghostly presence. I let the texture of lexicons resonate without rationalizing sources. There is nostalgia even within lyrics remembering the texture of sounds. I still get a kick out of language.

I knew you the day you were born.

You came to us on a gray October morning, your tiny lungs protesting the cruel chill of air on the first day of your life. With your arrival came the usual fanfare; NICU staff swarmed you like ants to a crumb, hand after hand adjusting the tubes and lines supporting you. I followed you down to the OR, scrubbed in to assist my attending in the surgery but really, I was there to hold your hand. Being born is lonely. Even surrounded by people the way you were from the moment you took your first breaths, I knew the artificial warmer in the NICU was no replacement from the warm embrace of your mother’s body. When things quieted and you were safely back in your room I stayed there as long as I could, your little hand wrapped around one gloved finger. I had a feeling I knew you in a way that nobody else would ever know you, amid the soft hum of machinery and the glow of evening, in the hush of a new beginning.

I saw your name again a few weeks later. My heart sank when I clicked through the chart and found your diagnosis, knowing that you were unlikely to see your first birthday. After rounds I went to visit you, armed with a nurse’s blessing and your afternoon bottle. When I picked you up I saw you open your eyes for the first time since I’d met you, and I swore for a second that you recognized me. I held you close as I fed you and I rocked you until you fell asleep, your tiny chest rising and falling with determination. In reality, I knew you didn’t recognize me. I was just another in a long line of caregivers that would come in and out of your life, and yet I felt connected to you.

Holding you that day made me think of the ways that I have embraced others. The first person I remember holding is my sister the day after she was born. She is the most special person in my world and I have held her close ever since, even when the miles separate us. When I was young and my mom was diagnosed with cancer, I held her hand as we walked sixty miles together to celebrate her victory and to advocate for a cure. On the day my white coat was draped across my shoulders I held my grandparents, the people whose values made me the person I am today. I have held silences and conversations, moments of grief and moments of joy. In my life I have opened my arms to heartbroken friends, exuberant teammates, zealous strangers, and my loving family, and I have known for years that I was born to care.

I knew you the day you were born.

As I held you that day I understood the connection I was feeling, the humanness of the experience I shared with you. With my arms around you, I did not need words to explain that to be human is to know that you are never truly alone. To be human is to have the right to be loved. And at its core, what is medicine if not the most human of all professions, the art of caring, the art of loving others?

I happened upon your chart a few months later.

And that is a lie, because I had been checking in on you every week.

I sifted through the flood of notes in your chart and stopped when I came to the last one. You had gone from this earth, more peacefully than when you entered it. Once again, surrounded by people, but I knew. Dying is lonely.

As I sat in my car with glassy eyes I stumbled across a poem my mom had written for me twenty-three years earlier. a mother’s love tiny hands that clutch at my breast eyes so open, so soft, so trusting little clothes that smell like spring and spit-up at the same time her small head wet from sweat because I’ve held her in my arms too long the depth of emotion unimaginable and a feeling of life complete though someday I will have to let her go this is now all mine

and I am holding it tightly in my mind and heart for a time when I will no longer hold her.

I spent so many days holding others that I had forgotten what it meant to be held. I realized that the most important person I embrace, the only one I will have and hold forever, is me. I know that to show myself kindness is to acknowledge that all people are deserving of the same kindness, and to show myself love is to understand how I might better show love to others.

This love is why I am in medicine. This love is what carries me through the hardest parts of caring for others. This love reminds me that we are all connected by this experience of being human. This love is the reason I open my arms and my heart to this beautiful, tormented world and everyone in it.

Thank you, for reminding me of love.

Imane Ridouh

Imane Ridouh

In room 218 there is a man with an ingrown toenail

Staff take turns explaining how local anesthesia will be enough

He argues he does not want to be awake for his surgery

He calls his mom

We wait

For what, I do not know

We continue on our rounds

This becomes a problem for overnight cover

I don’t know what happens to him

I never see him again

In room 468 there is a man with diabetes

Scheduled for a foot amputation

He would rather keep his leg covered

Out of sight

The skin swollen and discolored, exudate seeping into the hospital blanket

His wife loudly plays candy crush

She does not look up when we enter the room

She has seen many limbs lost

But this is routine and life goes on

He is wheeled off to the OR

In the hallway the intern asks the nurse to borrow a chair

His eyes are bloodshot

He is slow to respond

I do not ask how long he has been on

I would not know how to respond

Is it normal for him to be this tired

Is it normal for a man’s foot to be amputated

Is it normal for an ingrown toenail to delay our schedule

In the hospital

I lose sense for all that is normal

It is the 24th of March, 2020. Many may die from COVID-19; thousands have already. The strangest thought to think is that in the absolute worst-case scenario, in which humanity becomes no more, Nature will live on, seemingly unaffected, if not improved…

I’m in the woods right now. On the green belt. Birds are chirping, spiders are weaving, slugs are traveling, water is flowing; Butterflies warm up in the sun, grasshoppers hop on the run; Plants wave as the wind blows, rocks sit—certainly they don’t know. The bumbling bees bombinate about. I’m surrounded by so much life, yet it feels like a drought.

This drought will yield a fertile spring—not for me, or for you, but for life in between. Nature will finally find respite in this Anthropocene, While we hope and pray to wake from this nightmarish dream.

I’ve known it to be true that “good health is a crown only the ill can see”; Until now, in the middle of a pandemic, where corona is king.

We feel helpless—searching, searching, what can we do?

Social distancing for me, for you, and you.

But what is the answer when you feel 6 feet away from yourself?

Mental health, mental health, mental health… is not good right now.

Almost two years ago I sat, On a wooden bench in the woods, Not unlike the one upon which I sit today.

In these years I have grown older, stronger, been remade; Yet sometimes it feels as if I stood still for six hundred and seventy-eight Days, while the world whirred by. Do you know what I mean?

But time kept moving, Zooming; As evidenced by the fact that this past week I studied coronavirus, As a medical student in year one. What an honor it is to join this profession, Alongside professionals who so courageously, resolutely, and selflessly serve our world community.

Let us not forget the true meaning of that word, which is common unity.

For it was together that we made it this far: New vaccine technology and anti-viral therapy; hand washing, social distancing, mass testing, & mask wearing; Sacrifices made and processes made anew, Through cross-sectoral innovation and collaboration to navigate challenges that loomed. Acts of kindness that nourished our scorched soil; works of art that watered our parched soul; Workers on the frontlines, like Atlas to the rest, Bore a weight that none would wish to bear, but they did so anyway, For us.

They pulsed like a heartbeat. Essential. Yes, let us not forget the power of common unity.

For it was together that we faced the trials and tribulations of the pandemic: From lost jobs, homes, education, and progress, To lost hopes, dreams, friends, and family; Disproportionate were these impacts on people of color. Undeniably. Inequity on full display. And the days of “COVID blues,” as my father coined, In which we were forced to pay an existential tax to an unrelenting collector, While we languished, and our thoughts we tried to collect. The roller coaster of emotions we rode, month in, month out, On the statistical graphs of cases, with their spikes and doubts. No, let us not forget the power of common unity.

For in this understanding comes a great opportunity, To emerge a more empathetic, resilient, equitable, resourceful, stewardly, and compassionate community.

You, me, each and every one of us—we now travel on journeys during which we have met COVID. Yet, I wonder.

What is it that you think of…

when you take rest, on the wooden bench in the woods?

in the beginning god created light the absence of darkness enveloped the night a face turned upwards towards the stars the soul stares backwards counting the scars

a thousand days flicker in the dead of the night fluorescent bulbs biding the end of a life

the alpha and omega in neat lines of sutures

the knots and have-nots and wantons alike

look to the heavens that sliver of light still in the depths of (your) small human minds

see that the giants who offered their lives for mortals to see that they are the blind god calls the foolish out of the night to shame the brightest of all the might they often forget that portions of high are only borrowed gifts of time

above all else, consider it (your yoke) light when you do what you love and

love your neighbors right the moment you lose the you that (shows) love is the moment that you return to the dust

pros· o· dy ( noun)

Prosody, the student-run literary and arts magazine of Dell Medical School, brings together student, resident, fellow, faculty and staff voices to explore the intimate connection and meaning inherent in the practice of medicine through prose, poetry and visual arts.

Read Online: Prosody.DellMed.org