Design Code Pathfinders Programme

Supporting local authorities and neighbourhood planning groups developing design codes

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 2 Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 10 The Pathfinders 14 Chapter 1 Pathfinders’ progress against the NMDC 16 1. Set-up 19 2. Engagement 27 3. Analysis: Scoping and Baseline 38 4. Setting a design vision and coding plan 42 5. Coding 46 6. Testing: Adoption and implementation 49 Chapter 2 Monitoring and Evaluation 54 a. Experience using National Model Design Code 55 b. Developing authority-wide codes 56 c. Neighbourhood Planning Groups (NPGs) 56 Chapter 3 Evaluation of the Pathfinder programme 58 a. What went well 62 b. What could be improved 63 c. Spotlight on where Pathfinders needed more support 66

Appendix 1: Pathfinders’ experience of the Pathfinder programme 68 Appendix 2: Community engagement 72 Appendix 3: Consultants and procurement 74 Cover image: Be First

Appendices

The Design Council is working with the Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and the Office for Place Advisory Board to support 25 Design Code Pathfinders to produce design codes for their local areas using the National Model Design Code (NMDC). The Design Council are overseeing the monitoring and evaluation of the Design Code Pathfinders Programme, which focuses on the Pathfinders’ experience of producing their design codes, as well as the programme of support they have received.

Executive Summary

The government’s focus on design codes can help to create well-designed and beautiful places, and provide clarity for developers about what is expected, supporting a faster, more transparent planning system, and bringing in the democratic process of engaging people in the transformation of their places early on, as part of the plan making process.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 4

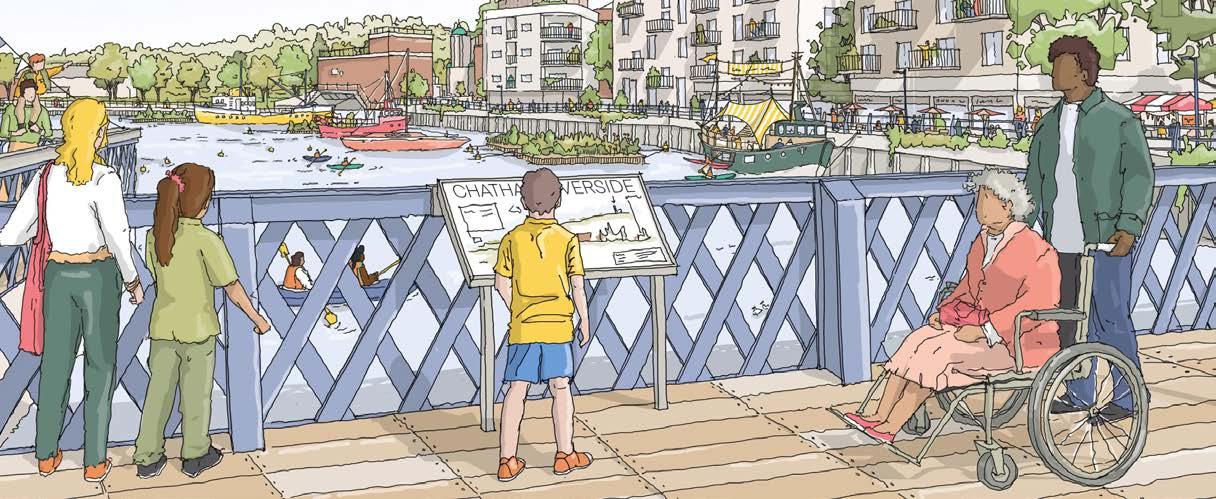

Image: Design for Homes (left), ImaginePlaces (right)

5 The Design Council

Introducing the key learnings

We evaluated the Pathfinder teams over nine months and distilled their experiences to identify the most pertinent programme learnings. We shared emerging findings with an enabling panel of Design Council Experts, DLUHC, the Office for Place Advisory Board and the Pathfinders themselves at two strategic points over the course of the programme. The findings, ordered to correspond with the stages of the NMDC, are summarised below and outline specific activities that need to be considered by teams for successful coding:

1Building a skilled and committed coding team

Pathfinders said they would have benefitted from dedicating sufficient time to assess the skills and resources available to produce the design code. They reflected that development management officers were key stakeholders to determine the areas of focus for the code content and its implementation, followed by the relevant Highways Authority.

There was a preference for preparing codes in-house, provided that the skills and funding were available. Those Pathfinders with dedicated resource committed to the design coding project had a better experience developing their codes, and saw design coding as a positive investment in their future.

Though many local authorities had to rely on commissioning consultants, as they lacked the in-house expertise needed to prepare design codes. Responsiveness, and an openness to being adaptable and flexible, were key markers of a good Pathfinder/ consultant relationship. The procurement of consultants sometimes took longer than

intended. On average, it took eight weeks to procure consultants, and forty per cent of Pathfinders said that this caused delays to the programme. This was not necessarily a bad thing. One Pathfinder told us:

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 6

“We were the last to appoint consultants, but I’d argue that is because we spent a lot of time getting the brief right, which is probably why our code journey went so well.”

Image: Urban Initiative Studio

Scoping the framework for design coding

The process of developing a code was easier for those Pathfinders with an up-todate local plan, and/or other up-to-date planning guidance. If this was not the case, then at this scoping stage, Pathfinders needed to be aware of how they were intending to incorporate the design code into an emerging local plan’s policies, or an adopted local plan’s review process.

Some Pathfinders developed a policy matrix, which enabled them to align their code to existing policies and identify where gaps existed. Others, however, found that the aspirations they had for their codes conflicted with existing policies, which was a challenge to writing objective requirements.

Pathfinders took different approaches from starting with detailed character analysis and generalising upwards, to asking development managers for their top three design issues. Whichever route was taken, the most successful Pathfinders were those that focused on a smaller number of design issues.

3Devising the engagement strategy

Despite the requirement for all local planning authorities to have a statutory, up-to-date Statement of Community Involvement in place, Pathfinders believed that design codes could play a critical role in increasing community participation in the planning system. Either through centring the community’s needs and wants in the code itself, defining how to engage with the local community as part of future applications or embedding community participation in planning through design reviews, for example. Achieving representative engagement was a challenge for most Pathfinders. Many had not formally determined who they would target, and the best ways to reach them. This lack of forward-planning or research led, in some cases, to poor and unrepresentative engagement.

7 The Design Council

2

Identifying design champions

Having strong champions was helpful to all Pathfinders to the development of the code, and their enthusiasm and commitment were important to Pathfinders, who felt bolstered by this support, and more confident in pushing for high-quality codes. We identified four kinds of champions that supported Pathfinder teams: technical champions understanding the planning system and supporting the technical development of the code; department leads connecting different workstreams; executive leaders securing the engagement of seldom heard stakeholders; and political champions securing the long-term buyin needed for eventual adoption and implementation of design codes in the local planning system. 5

Determining area types

The most successful Pathfinders already understood what an area type was and how to use it as a spatial planning tool. Those who did not quite understand the term struggled with determining area types. They had difficulty in seeing how coding could be developed in a locally specific way, to build on existing strengths.

Pathfinders in rural areas found it challenging applying the predominantly urban examples of area types that are indicated in the NMDC, to their local contexts.

Working at different scales

The challenge of working at different scales was significant. Many Pathfinders preparing authority-wide codes struggled to determine the appropriate level of detail for the scale of code. Generally, by the end of the programme, it was understood that:

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 8 6

“The more specific the code, the more musts you can have… so, at a district level, there will also be a high proportion of shoulds. And as you zoom in with a greater level of certainty to a neighbourhood level, or even a parcel level, that’s where the frequency of must-haves increases.”

4

Image: BPTW

Writing an implementable code

Some Pathfinders found it challenging to use coding appropriate language and struggled to achieve a balance between guidance and coding. Many of their codes were drafted from a policy perspective, rather than setting out clear rules, and were excessively long documents. Writing in general took much longer than anticipated, as refining the code and distilling it into key requirements (the musts) and guidance (the shoulds, or coulds) was a highly iterative and collaborative process. Checklists and trackers helped to simplify codes, and their ‘yes/no’ nature helped to underscore the degree of design code conformity.

Sharing learning around testing, adoption and implementation

Pathfinders had begun to test their codes with development management officers and developers – a vital step in developing useable codes – at the time of writing this report. Many Pathfinders were intending to use their design codes to build on and provide more detailed advice and guidance on policies in their development plans, and this was easiest for those with up-to-date local plans that included generic design policies. In these circumstances, the code could be adopted as an SPD, after following a statutory consultation process. For those Pathfinders with an emerging, new local plan, or where an adopted local plan was undergoing review, the draft policies and supporting text could be changed to reflect the code.

Additional guidance

Pathfinders asked for more guidance on developing authority-wide codes, on determining area types and on the specifics of coding for certain geographies and scales. They also asked for support on how to carry out effective engagement, how to develop digital codes and more expert input into addressing policy areas. In particular, there were perceived knowledge gaps in how to write codes that tackled specific issues such as achieving net zero, complying with biodiversity net gain legislation in force from November 2023 onwards, meeting housing land supply requirements and promoting active travel.

9 The Design Council

8

9

7

“Don’t underestimate the amount of time needed to churn through everything and come out with a workable code.”

Introduction Background

Sustainable development and achieving good design lie at the heart of the English planning system, enshrined in both planning law, through the preparation and adoption of statutory development plans and non-statutory SPDs, and promoted in national policy through the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and supporting guidance.

As set out in the NPPF, all local planning authorities in England should prepare design guides or codes consistent with the principles of the National Design Guide (NDG) and National Model Design Code (NMDC), to help achieve well-designed places and to provide clarity about design expectations. Where there is no local design guide or code in place, the NDG and NMDC are material considerations and should be used to inform planning decisions.

Image: Design Council

Image: Design Council

There is increasing recognition of the role that design codes can play in introducing clarity and certainty for applicants and speeding up planning decisions through better quality applications being made. As well as improving engagement with and transparency for local communities who can have an early and meaningful say in the shaping of their area. Government reforms are seeking to further strengthen the role of good quality design – and the weight attributed to it – in the planning system, to deliver well-designed and beautiful places. For example, the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill, due to be enacted in autumn 2023, includes at Schedule 71 provision which states that a Local Planning Authority (LPA) must ensure that for its entire area, the development plan includes the development design requirements that the authority considers should be met for planning permission to be granted. An LPA will be able to prepare design codes either as part of their local plan, or in a supplementary plan both of which will be statutory development plans.

1 In section 15F, ‘Design code for whole area’

About the programme

The Design Code Pathfinders Programme builds on the 2021 National Model Design Code (NMDC) Pilot Testing Programme, which supported 14 local councils in testing the application of different stages of the design coding process, as set out in the-then draft NMDC. As part of the 2022 Design Code Pathfinders Programme, 25 areas across England were awarded a share of £3 million to support the production of local design codes using the NMDC.

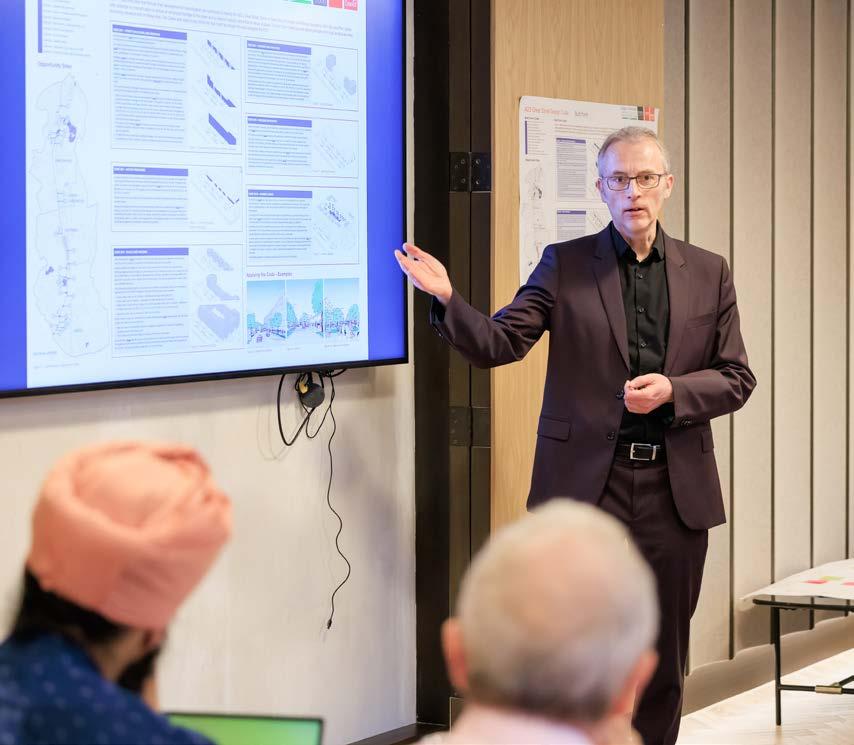

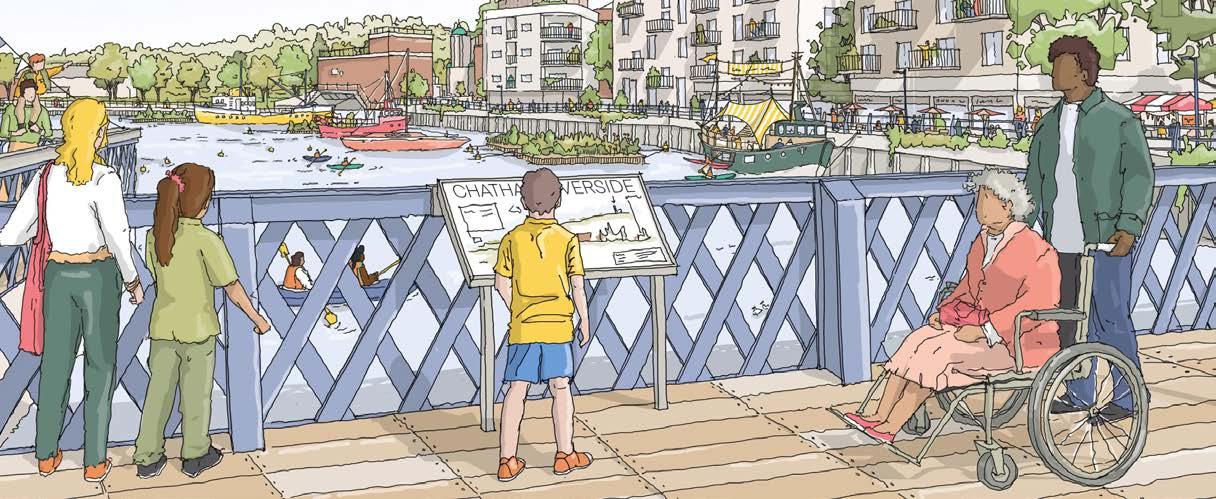

Alongside a package of support delivered to Pathfinders by DLUHC and the Office for Place Advisory Board, the Design Council has provided tailored help through a set of review panels that were delivered in the autumn/ winter of 2022. These sessions were followed up with a set of in-person cohort workshops in March 2023 that brought Pathfinders together to learn from each other’s experiences of developing design codes, tackle shared challenges and gain advice from the enabling panel (Design Council Experts).

11 The Design Council

Above and opposite page: Pathfinder Programme Review sessions.

Learning resources

In April 2023, an interim report was produced, which summarised emerging findings from the first phases of the NMDC process followed by the Pathfinders. These findings were presented to the Pathfinders in a collaborative workshop, followed by a set of activities to refine our understanding of their experience, prioritise key learnings and co-develop learning resources for future coding teams.

These resources, which can be found on the Design Council website, include Pathfinder interviews and insights and a flow chart of the coding process. The resources are referenced throughout this report.

Research methods

The research design was informed by an evaluation framework, developed by the Design Council in collaboration with DLUHC. Based on this framework, a toolkit was drawn up, which includes an ethics review and a suite of research methods. This report is based on four key methods, which include:

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 12

Image: Design Council

1. Two sets of in-depth interviews designed to give Pathfinders the space to explore their experience of the programme to date, including the aspects that have helped them, the challenges and barriers they have faced along the way, as well as obtaining their feedback on the support they have received. These interviews were transcribed, anonymised and analysed thematically to draw out key learning at different stages in the coding process.

a. The first set was carried out with 19 of the 25 Pathfinders between November 2022 and January 2023. The remaining six Pathfinders declined to be interviewed.

b. The second set was carried out with eight of the 25 Pathfinders in May 2023. We opted to carry out these supplementary interviews with only a third of the cohort as this allowed us to go into more depth. These were chosen in conjunction with DLUHC.

2. Documentary review of the design advice letters, summarising the advice that Pathfinders received as part of their Design Council-facilitated design advice sessions, which were held six months into the process, and again at twelve months. These letters were analysed to draw out the aspects of developing a code that the Pathfinders needed help with, from the perspective of the enabling panel (Design Council Experts).

3. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of monthly reports that were issued by DLUHC, and which asked the same 14 questions, supplemented by a further set of one-off questions relevant to the month. For example, ratings of workshops held, or the length of time taken to procure a consultant. Summary tables can be found in the appendix.

4. Participatory evaluation tools that were used to capture feedback from Pathfinders attending the design advice sessions. This feedback was analysed to draw out positive and negative aspects of the review panel sessions, as well as key learnings that Pathfinders took away from the sessions.

Pathfinder Programme Review sessions.

13 The Design Council

The Pathfinders

Overview of the participating local authorities and neighbourhood planning groups outlining the details of their design code.

Authority-wide

1 City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council*

Borough wide, with emphasis on Shipley, Keighley and Bingle.

Focus: site allocations, designated regeneration areas and council owned land

2 East Riding of Yorkshire Council*

Predominately rural area with coastal towns. Focus: development in settlements including infill and greenfield allocations

3 Gedling Borough Council*

Suburban city periphery with rural villages, historic mining. Focus: development in settlements including infill and greenfield allocations

4 Lake District National Park Authority*

Authority-wide covering the whole of the national park.

Focus: development in settlements including infill and allocations

5 Surrey County Council*

County wide code to focus on delivering healthy streets. Focus: streets, public realm, movement

6 Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council*

Suburban city periphery with historic villages in green belt.

Focus: development in settlements including infill and potentially allocations

7 Uttlesford District Council*

Predominately rural dispersed settlement pattern in green belt adjacent to London. Focus: development in settlements including infill and incremental greenfield sites

8 South Woodford Neighbourhood Planning Group†

It will cover all of the neighbourhood planning area, focusing on the town centre and site allocations

Site-specific

9 Reigate and Bansted Borough Council*

A23 corridor and catchment between Redhill and Horley. Focus: urban and suburban regeneration and infill, public realm/highways

Town centre

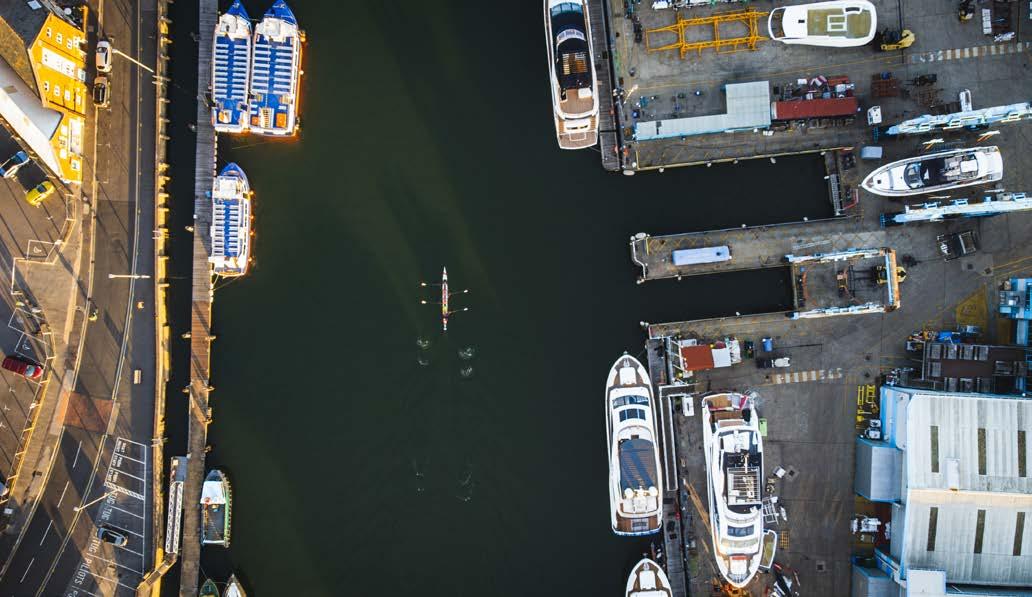

10 Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council*

Mixed use urban sites x2: Poole Quays, Poole and Lansdowne, Bournemouth. Focus: regeneration in historic urban areas

11 Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council*

Lye and Stour Valley, Lye district centre. Focus: regeneration of historic town centre including industrial areas, historic residential suburbs and green corridor

12 Mansfield District Council* Mansfield town centre. Focus: regeneration of historic town centre including historic residential suburbs

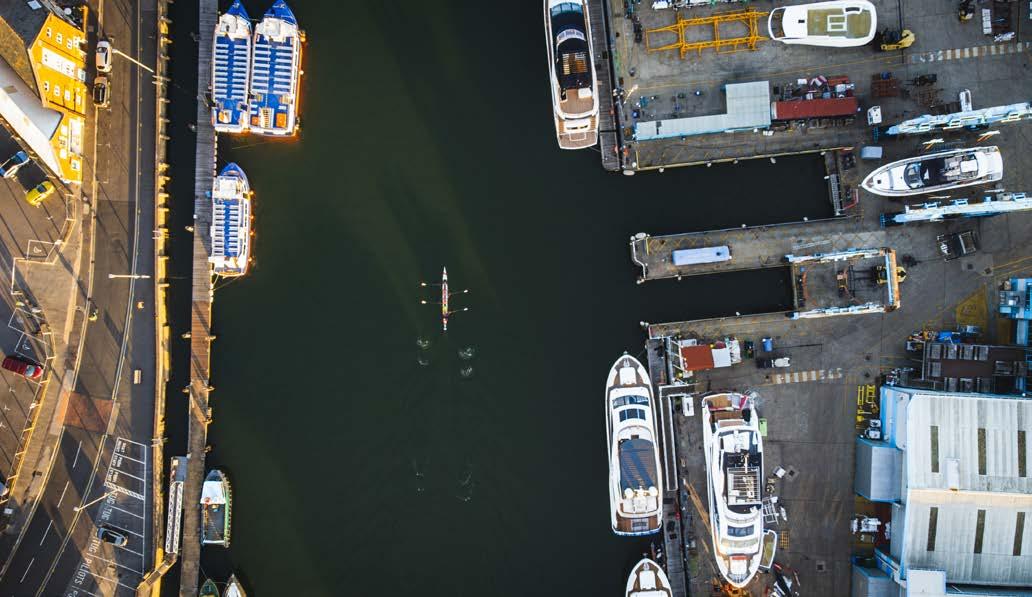

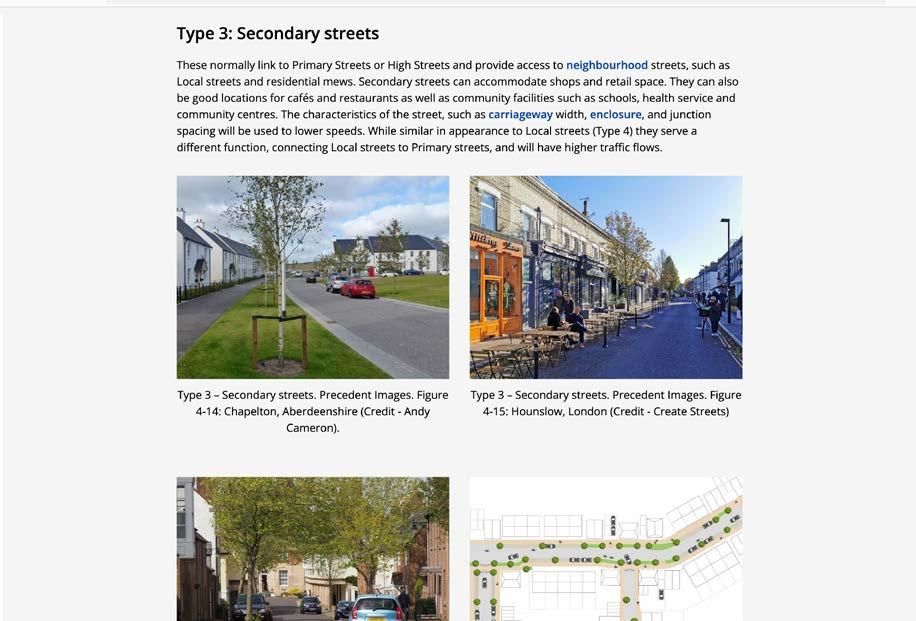

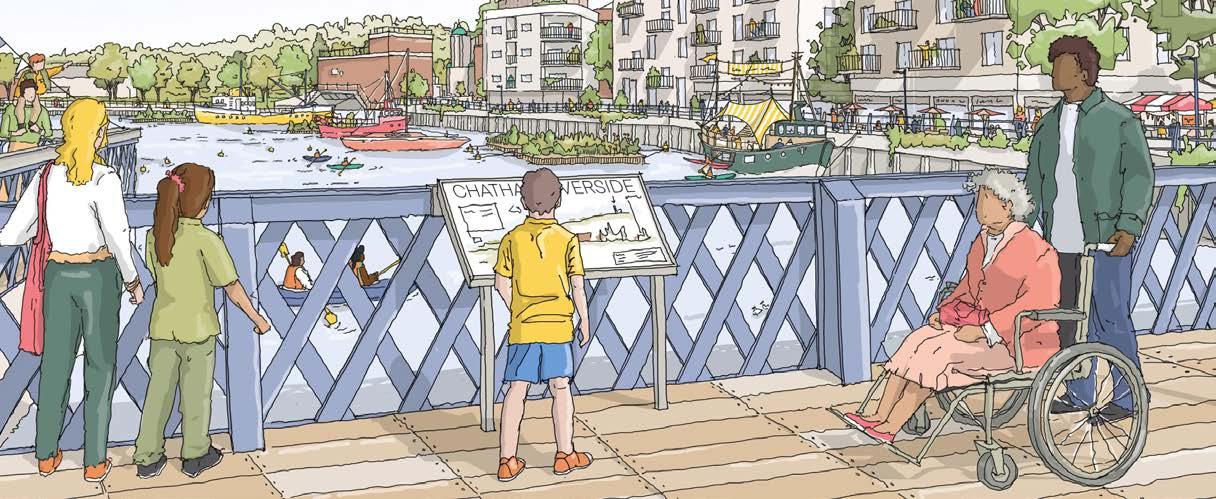

13 Medway Council*

Chatham Town Centre. Focus: regeneration of historic waterfront town centre including industrial areas, historic residential suburbs

14 Shropshire Council*

Shrewsbury Town Centre. Focus: regeneration of historic town centre including residential suburbs, waterfront historic park and garden, with authority as main landowner

15 Finsbury Park and Stroud Green Neighbourhood Forum†

It will cover part of the neighbourhood planning area, the District Centre also known as Finsbury Park Town Centre

16 Weymouth Town Council† Town centre. Focus: it will cover all of the neighbourhood planning area, with particular focus on central Weymouth, which includes the town centre

Mixed use site

17 London Borough of Brent*

Staples Corner. Focus: strategic industrial locations and site allocations

18 East Midlands Development Company*

Wider hinderland related to Toton and Chetwynd Barracks, Ratcliffe Power Station and East Midlands airport with detail on sites 1 and 2. Focus: landscape, connectivity, movement: regen, industrial intensification

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 14

Estate

19 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham*

Beacontree Estate. Focus: manging iterative developments across large interwar war housing estate

20 Greater Cambridge Shared Planning*

Arbury, King’s Hedges and West Chesterton – a low-density existing suburban area. Focus: infill development in existing areas which lack a strategic design vision New settlement

21 Carlisle City Council* St. Cuthbert Garden Village.

Focus: urban expansion/new settlement on mix of brownfield and greenfield including the creation of three new neighbourhoods

Urban extension

22 Darlington Borough Council* Skerningham Garden Village.

Focus: urban expansion on mix of brownfield but predominantly greenfield

23 Epping Forest District Council*

Latton Priory, Harlow and Gilston Garden Village. Focus: urban expansion/new settlement on mix of brownfield but predominantly greenfield

24 Teignbridge District Council*

Houghton Barton, Newton Abbey & Kingsteignton Garden Community.

Focus: urban expansion on mix of brownfield but predominantly greenfield

Key

* Local Authorities

† Neighbourhood Planning Groups

15 The Design Council 13 19 9 8 7 20 18 4 12 11 6 1 22 21 2 14 3 23 15 17 10 16 5

24

Pathfinders’ progress against the NMDC 1

In this chapter, we summarise the experience of Pathfinders putting the NMDC into practice over the course of the Pathfinder programme, highlighting their learning to inform future guidance and support future coding teams in the design coding process. We have chosen to order the findings to correspond with the stages of the NMDC.

The following table has been drafted based on progress information submitted by Pathfinders in monthly reports and indicates the proportion of Pathfinders who had engaged with each stage of the coding process across the twelve-month programme.

Table 1: A heat map of the Design Code stages engaged with month-to-month; percentages refer to the proportion of Pathfinders who undertook phase-specific activities in that month.

17 The Design Council

1 Month Responses, n= Scoping Baseline Design vision Coding plan Masterplan ning Guidance for Area Types General Guidance May 2022 24 88% 83% 25% 8% 4% 4% 25% Jun 2022 24 75% 75% 33% 13% 8% 17% 17% Jul 2022 21 81% 81% 48% 19% 14% 14% 19% Aug 2022 22 64% 82% 41% 27% 9% 14% 18% Sep 2022 18 56% 78% 72% 33% 22% 22% 22% Oct 2022 21 71% 71% 76% 57% 33% 24% 29% Nov 2022 20 60% 60% 60% 55% 25% 35% 25% Dec 2022 20 55% 65% 85% 70% 25% 25% 35% Jan 2023 18 44% 56% 78% 89% 50% 61% 50% Feb 2023 18 28% 33% 56% 67% 56% 56% 50% Mar 2023 15 20% 20% 40% 60% 27% 80% 60%

10 Characteristics of Well-Designed Places

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 18

Image: National Design Guide

1. Set-up

This section summarises learnings from the Pathfinders on how to lay the foundations for a successful design code ahead of formally beginning the coding process itself. It includes their reflections on how they might change their approach going forward.

More details on this step are available in the Pathfinder Insight piece: Working in partnership.

a. Producing a clear and well-defined brief

Reflecting on how they might have better prepared themselves at the outset, Pathfinders said they would have benefitted from dedicating sufficient time to assess the skills and resources available to produce the design code, as well as time to produce a clear and well-scoped brief that clearly articulated the outcome they envisioned the design code would produce. Data from the monthly reports show that Pathfinders spent up to two months developing a brief and programme. One Pathfinder, who spent significantly

Take-aways for future design coders

longer (four months) on this process was able to develop and refine their brief in conversation with colleagues in other departments which, they said, helped them in the process of developing a design code:

“It’s key to try and establish as much as you can before you get started – in terms of what you want this code to achieve, who you’re going to involve, what the timescales are going to be, what resource you need to undertake, even if you are going to be appointing consultants. [..] This was something we set up before we went out to tender and procurement, to have that working up the brief.”

Developing a programme plan helped Pathfinders manage expectations and ensured their coding followed a logical process. Having a clear narrative, vision, and focus on specific issues helped teams have a clear goal for the code throughout the process, and ensured those goals were being met.

Allocate sufficient time to writing a detailed briefing document that includes:

Why a design code is the right tool for the desired outcomes.

How a code delivers better design and value for local communities.

The stages of work to provide structure to the project.

The skill sets and working relationships required for collaborative working.

Inspiring case studies that illustrate the design code’s potential.

Test and iterate the briefing document:

Before going to tender, to ensure it reflects priorities and to manage expectations around costs and the number/quality of tender responses.

19 The Design Council

b. Setting up a well-resourced team

Pathfinders found the process of developing design codes timeconsuming, leading to some instances of stress, particularly for those teams who were working on design codes alongside other responsibilities and projects. Wellresourced Pathfinder teams had a better experience. These teams often had backfilled resource or a newly created role and had ring-fenced time and expertise dedicated to developing a design code, and/or were working with a good consultant to project manage.

“Having a dedicated project manager – a ring-fenced resource – has been crucial to the process. I’m not quite sure how we would have done it otherwise. We really committed to it.”

Many Pathfinders preferred to carry out design code development in-house if they had the required capacity and skills available. They felt that their teams’ understanding of the local area was invaluable. Where Pathfinders did work with consultants, it was felt time-consuming to convey this local knowledge to someone new. Working with consultants felt therefore slower than anticipated.

Local authority Pathfinder teams valued input from their development management officers and the Highways Authority. Early engagement helped teams to understand their processes, and to align their code to their priorities. This supported code development

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 20

Image: Mansfield District Council, PJA and Urban Design Doctor

and the prospect of adoption and implementation. However many struggled in bringing these colleagues on-board. Shorter, more focused sessions helped some Pathfinders to include their colleagues’ perspectives.

“Everyone’s capacity is so stretched, and people want to be involved, but they’ve also got this mountain of work. But I think if it’s something small for an afternoon, and not a big commitment, then that’s easier to get involved with.”

“We have a Teams channel with officers. So, whenever we’ve had anything to look at for the design code, we’ve been able to post something and say: ‘This is what we’ve got, you have a week to look at it, please feed back to us.”

Pathfinders working to a clear and detailed programme plan were better able to manage their time. They were able to predict pinch points, such as extended absence or staff turnover, and plan for these accordingly. Seeking feedback regularly helped one of the Pathfinder teams to maintain momentum with their colleagues and stakeholders, as well as building a sense of trust and ownership within the wider team:

“We’ve tried really hard to keep things moving and just put out a draft as it is. I’ve just said to all of the officers, ‘I’m not an expert, so tell me what I’m doing wrong’.”

21 The Design Council

Image: Mansfield District Council, PJA and Urban Design Doctor

Take-aways for future design coders

Establish a clear and realistic delivery plan that includes: A dedicated project manager.

A detailed programme plan with defined roles and responsibilities for all.

A leader or champion who can ensure regular contributions from development management and Highways Authority colleagues (collate diaries with local authority officers well in advance given their limited availability) built in flexibility for leave, staff turnover and workloads (encourage the coding team to be transparent about their competing priorities, so that these can be accounted for in advance).

Encourage leadership buy-in, by framing the development of design codes as an opportunity to:

Embed a culture of delivering design quality.

Identify skills and resource gaps.

Learn from experts and provide a tool to train officers in future.

Set up a multidisciplinary in-house team: Include someone from the planning policy team, and officers with urban design and development management expertise.

Ensure access to a wider team of regular consultees, a steering group, or design review panel that will include people with backgrounds in architecture, landscape design and sustainable travel, and with expertise that matches key policy areas.

Consider whether there is resource to bring in consultants to add a fresh perspective in addition to their niche expertise and knowledge of best practice.

Explore whether external expertise can be found through offering placements and secondments such as, for example, ‘Public Practice’ which is an organisation that offers placements for professionals in the public sector.

65% of Pathfinders had extant planning policies or existing guidance that referred to architectural styles

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 22

c. Identifying design code champions

Having champions as part of the project team was seen as helpful by Pathfinders to contribute to the development of the design code. We identified four kinds of champions that supported Pathfinder teams:

• Technical champion: understands the planning system and can bring relevant people together, as well as contribute to the development of the code in technical terms.

• Department manager: makes connections between different workstreams.

• Executive leaders: secures engagement of seldom heard stakeholders.

• Political champions: crucial to secure long-term buy-in needed for eventual adoption and implementation of design code. These political champions range from parish and town councils acting as NPGs, to councillors and local MPs.

“Try and get key elected members on board as early as you possibly can: We got the mayor involved very early in the process, and key politicians, members of the business community, to do walking tours around the town, so they could listen and have it explained to them what the process was.”

“From a political perspective, this site has credibility with the politicians thanks to the process we’ve been through. That forms the evidence and demonstrates local support for what can be achieved here.”

d. Auditing policies and evidence

Existing development plan policies offered a clear idea of local priorities and an up-to-date local plan made the process of developing a code easier for teams. This was especially the case for authority-wide codes. It was also the case where an adopted SPD for example a design guide, or other planning guidance, was already in place.

Sixty-five per cent of Pathfinders had extant planning policies or existing guidance that referred to architectural styles2. Working with out-of-date development plan policies posed challenges to Pathfinder teams developing a design code. In some cases, Pathfinders had to write guidance or review and update local plans concurrently with developing their design code, which resulted in an increasingly unclear scope and confusion about what to code for. Ideally codes reflect and elaborate on adopted policies and existing guidance.

“If you go for a borough-wide level code, make sure that you’ve got masterplans for the big sites, because then you can just hang general coding off the bottom of those master plans, rather than having to code on an individual site basis.”

When determining the policy areas to address, policy matrices were a useful tool to keep track of everything that needed to influence and inform the code. Selected Pathfinders used this tool to determine the focus for the code and avoid possible duplication or contradiction between policies, guidance and the code. This tool also helped to make the design code easier to implement by development management officers, by referring to the NPPF and the NDG.

23 The Design Council

2 Statistic from monthly reports; 20 respondents to question (25 Pathfinders).

Take-aways for future design coders

Analyse and audit existing evidence and data

Check ahead of time for access to up-to-date (in-house and national) data needed for baseline evidence to help understand the need for new mapping.

Analyse and audit all relevant policies, plans, and guidance

Check if the development plan, relevant design guidance and any masterplans are up-to-date and consistent with national planning policy.

Be aware of upcoming NPPF changes and updated national guidance (allow flexibility in the code to respond to updates).

In absence of an up-to-date local plan take time to develop a locally informed vision to establish strong design principles.

Map existing guidance to avoid repetition and contradiction

Check existing policies for gaps and cross-reference all planning guidance. Check NPPF and relevant legislation, with respect to heritage protection and building heights to ensure compliance.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 24

Image: Design Council

e. Procurement

All Pathfinders worked with at least one or two consultants on developing their design code. Just over half said that a consultant was leading on the overall project management of the design code, and a third had a consultant managing the community engagement. In general, consultants were supporting every stage of the process, particularly the Design Vision, Coding Plan stages3. On average, it took eight weeks to procure consultants and 40% of Pathfinders said that this caused delays to the programme. This was not necessarily a bad thing. One Pathfinder told us: “We were the last to appoint consultants, but I’d argue that that is because we spent a lot of time getting the brief right, which is probably why our code journey went so well.”

Working with consultants was a mixed experience. Some Pathfinders benefitted from a genuinely collaborative working relationship while others found consultants – predominantly those developing authority-wide codes –did not produce work to schedule. Pathfinders that were successful at building a strong working relationship with the consultant credited this to having developed a clear brief.

“You have to make sure the brief has the right sort of ingredients. We were quite clear in our brief the output we were looking for, the different issues it needed to address and the process that they needed to work with us on.”

A strong working relationship and shared, deep understanding of the code’s purpose and scope were just as important as the competence of a consultant. Most Pathfinders found that

their brief and scope changed over time as it evolved with the findings from the engagement process and said that a flexible and collaborative mindset were other important qualities for a consultant.

“It’s also a learning experience for the consultants… we’ve all needed to continually re-evaluate, and try and keep on track. The consultants have been very open to that. But again, that was their brief: that they were going to work with us to find the best solution.”

It was seen as beneficial to work with consultants that had an existing understanding of the local area and/ or had worked with the Pathfinder organisation before as on-boarding consultants that were unfamiliar with the area took considerably longer than some Pathfinders anticipated.

25 The Design Council

3 Over 80% of Pathfinders had consultants supporting them at these design code stages.

40% of Pathfinders said that the procurement of consultants caused delays to the programme

Spotlight on Bradford Council: Procurement of consultants

When selecting a consultant for its design code, Bradford Council set a brief in conversation with colleagues to ensure it would reflect priorities across various departments. This resulted in a comprehensive briefing document outlining the desired outcomes and the process the consultant would be expected to deliver. The selection process involved a competitive tender, with ten companies submitting proposals. The successful consultant demonstrated its understanding of the challenges and issues faced by

Take-aways for future design coders

Find a collaborative consultant:

Explicitly request a partnership approach, manage expectations on scope of their work.

Interviewing potential consultants may help to gain a better understanding of their expertise, their understanding of the brief and will offer the opportunity to explain your requirements of the working relationship.

the district and its ability to work with the council and the community. The consultant team included experts in urban design and planning, and brought in additional consultants focused on community engagement, civil engineering and cost and viability analysis. The team worked closely with the planning authority in testing the emerging code and responding to stakeholder concerns.

Ensure consultant has the right skill set, consider:

Urban design, architecture, landscape design.

Technical skills, including data analysis, GIS, 3D modelling, technical drawing.

Good understanding of the planning system.

Digital expertise for digitising the code.

Graphic design to support the development of an accessible design code.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 26

2. Engagement

This section summarises learnings from the Pathfinders on how to successfully carry out community and stakeholder engagement. Not only to generate insight on priorities and ambitions for the local area at the outset but throughout the design code process, to ensure that findings have been accurately reflected, and to test useability of the final design code.

More details on this step are available in the Pathfinder Insight piece: Community Engagement.

Pathfinders spoke about the importance of managing the expectations of all groups involved in what the code would realistically cover (geographically and in scale and level of detail), and what it would be able to achieve. Setting out the purpose of design codes was therefore critical to keeping discussions relevant and focused. Being transparent also helped to foster trust and helped those involved to understand how their contributions were going to be used to develop the design code.

“One challenge is about perception of what the design code can do: perhaps politically, it is seen as the answer to all of the problems in the town centre.”

Sharing feedback between the community and stakeholders was important for transparency in the coding process, developing a coherent and well-rounded vision and keeping all participants informed on the direction of coding. The Pathfinders who successfully integrated community and stakeholder perspectives into the code followed an iterative process to enable a feedback loop between the community and stakeholders.

“We directly fed in what the citizens’ panel’s thoughts were into the stakeholder workshop as a sort of summary of the opening statements used to set the scene. This would then lead into a slightly more technical, more professional discussion on whatever the topics were. But always led by what the citizens had said.”

“We’ve made each iteration of the code available to people in advance of the workshop, so they’ve had a chance to look at it, digest it and see whether they think it works or not. The document has evolved and changed as a result.”

27 The Design Council

a. Community engagement

Accessible consultation material made for a more efficient and relevant engagement process. Communities struggled to contribute to abstract or open-ended questions and preferred having something tangible to respond to. Surveys that asked about likes and dislikes were more successful when they were accompanied by examples. This resulted in a more efficient and rewarding analysis process for Pathfinders as it allowed them to use the communities’ insights to define and refine design codes. Pathfinders found that communities responded well to working collaboratively and on equal terms with the coding team. This approach was helped by working with facilitators who did not have a planning background, and were able to support development of accessible consultation materials and events.

“[Our facilitators] were semi-independent from the process, so it’s not a planning officer with a preconception of ideas and approach who will speak in jargon.[They] come from a different background, and that was part of the success of it [the engagement].”

“They [the participants] didn’t feel dictated to, they didn’t feel like they were talked down to, or that they lacked the knowledge or expertise needed to help us make decisions going forward.”

Representative community engagement was a challenge for all Pathfinders, and they particularly struggled to engage young people. Solutions varied from giving talks in schools, using targeted advertising on social media, or recruiting engagement experts to run workshops with young people on behalf of the Pathfinder teams. This last activity was found to be the most successful.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 28

Image: Mansfield District Council, PJA and Urban Design Doctor

Achieving representation from marginalised groups, such as those living with long-term health conditions, people with disabilities, or ethnic minorities, was most successful for Pathfinders who had intentionally reached out to affinity groups and used connections they already had.

“We’ve done lots of engagement in terms of disability groups…an access officer at one of the councils is a wheelchair user himself. He’s been out on a lot of the walk-and-talks with different user groups and really contributed to the inclusivity elements of the code.”

Financial incentives were used by a few Pathfinders to encourage participation from people who were less likely to engage normally and to renumerate participants for their time. While the view was that it may sound cost-prohibitive to pay community members to participate in engagement, it may not require continuous investment to keep people engaged, enthusiastic and participating. As one Pathfinder told us:“The incentive certainly helped them sign up. But what was interesting was [that] after the first session, they didn’t feel that they needed any kind of incentive. They were signed up, they had trust in the process, and they were enjoying participating as well. The feedback that I received was that the residents got a huge amount from being part of this process, and from feeling that they could contribute to shaping this new development.”

Inclusive Design Audit

29 The Design Council

Images: Mansfield District Council, PJA and Urban Design Doctor

Low turnout and response rates led to delays in the design coding process for some Pathfinders. Pathfinders who hosted events around Christmas or over the summer holidays reported low turnout. It was found that the Pathfinders who made use of target advertisements for their surveys on social media received more responses. Linking to social media accounts was also found to be effective. Another Pathfinder reflected that the poor response to their survey was the result of having too many questions, which put respondents off.

Maintaining momentum over time was important to ensure consistent input from communities during the coding process. One Pathfinder who worked with their communications team on producing regular messaging from the beginning saw the benefits. As word-of-mouth grew, participants became more trusting of the process and would advocate for design coding – bringing friends and family to events.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 30

Image: Carlisle City Council

Spotlight on Teignbridge District Council: A citizen assembly

Teignbridge District Council choose a bespoke approach to community and stakeholder engagement, creating a citizen panel to explore diverse views and opinions and develop a shared vision for the coding sites. The citizen panel met fortnightly, with each of the five workshops centred around a key theme such as low carbon operations, shaping the new community and buildings and streets. Using activities such as visioning exercises, creative writing and site visits, the citizen panel worked with the local authority to establish three key spatial principles for the code (creation of place, people and

nature first, a connected and invested community).

The feedback collected at each session set the scene for the subsequent stakeholder discussion. A diverse range of stakeholders was brought in to discuss questions, ideas and concerns addressed by the citizen panel. This approach was repeated to create a feedback loop between stakeholders and the community which helped develop a shared understanding of each other’s priorities and challenges.

31 The Design Council

Images: Be First

Community engagement activities

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 32

Image: Teignbridge District Council

Citizen Assembly Workshops

Take-aways for future design coders

Develop a clear engagement brief and programme before scoping:

Use a mix of digital and in-person engagement techniques, including activities that are tailored to seldom heard groups.

Consider using financial incentives to help establish an engaged group of residents at the outset.

Consult a marketing and communications expert for a comprehensive programme aligned with local engagement activities to avoid consultation fatigue.

Consider when people are most likely to be available for engagement activities.

Connect engagement activities to existing local events to reach a wider audience.

Develop an approach for GDPR ahead of undertaking consultation and engagement activities.

Work with third-party organisations to engage seldom heard groups:

Map out groups to be reached, to help inform types of activities and times to engage them.

Work with external organisations and affinity groups to demonstrate impartiality/build trust, for example church groups and secondary schools.

Test consultation materials ahead of publishing:

Have a multidisciplinary team, including non-planning backgrounds, to develop accessible material and test survey questions to ensure correct interpretation.

Be explicit about what is achievable to encourage more relevant responses.

Liaise with other departments on consultation feedback for example parking problems.

Consider the use of language to simplify planning:

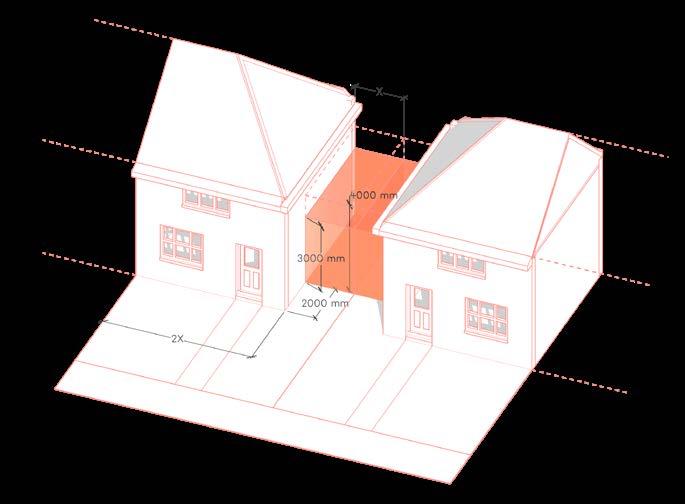

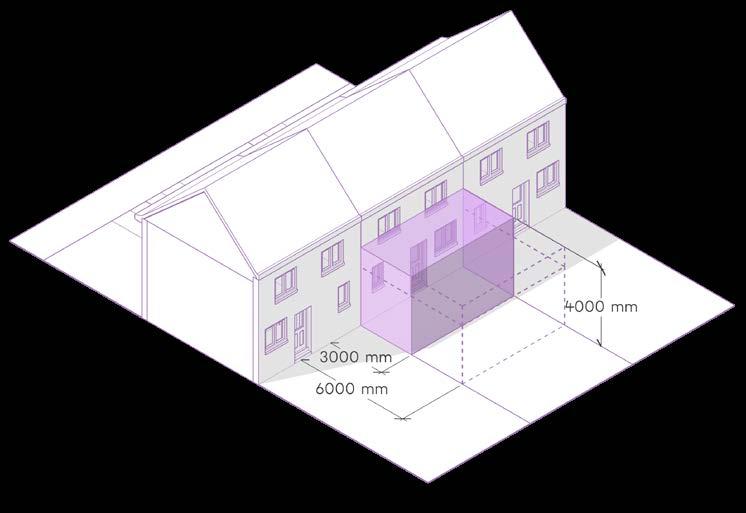

Use accessible language and visual materials such as 3D-models, drawings and photos.

Don’t over complicate – focus on what people like about their place, what they would like to see improved, and their vision for the future.

Stay in touch with stakeholders and participants:

Keep them updated on progress and how their contributions were used.

Ask for feedback after events to understand how members would like to be involved in the future.

33 The Design Council

b. Stakeholder engagement

Investment in the stakeholder engagement process was worthwhile, as meaningful engagement and regular updates with mixed groups created buy-in, enthusiasm and positivity. Moreover, their input was necessary to ensure that the code’s content was wellinformed and would therefore be better understood and successfully applied by responsible authorities.

Pathfinders engaged stakeholders with interests and expertise across a range of planning themes to support the development of their design code. Stakeholders were invited to comment on relevant themes and topics to make best use of their expertise. Pathfinders with existing relationships were able to leverage them to benefit the coding process. NPGs were the least able to convene stakeholders easily, which they attributed to being perceived as residents developing a design code, with little power or influence.

Many Pathfinders struggled to engage elected members. Some found that political sensitivity around development, and upcoming elections, meant that their consultations with councillors were deferred or postponed indefinitely. Finding a political champion was important, as noted above, and Pathfinders who had this support felt more confident about the adoption and implementation of their code in future. Elected members were keen to be involved where a code centred on community aspirations.

“Some of the leading members, including the leader of the council, are very strong supporters of this process. They have said: ‘Who are we to take all the power? Let’s listen to different voices, different views, and bring those into our decision-making’.”

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 34

Stakeholder engagement activities

Image: David Lock Associates for Gedling Borough Council

Some Pathfinders were initially concerned about engaging with developers, fearing that they would not respond positively to change, or that a code would be perceived to threaten the viability of proposed schemes. Pathfinders who engaged with developers and landowners throughout the coding process found that, while many were apprehensive to start with, they realised the purpose and benefits of design coding once they gained a better understanding of community priorities and the value of these insights. Particularly when they discovered that community priorities were often focused on making better places, rather than voicing opposition to development. In some cases, developers were pleased to be given the opportunity

to participate in the process as they perceived the current planning system as adversarial and unpredictable.

“Developers came into the process perhaps thinking that they [the community] would not like anything. And then when we actually explain what citizens have said, they [developers] understood that ‘Okay, they’re actually quite reasonable’.”

Those Pathfinders with pre-existing formats for engaging regularly with developers, such as developer forums, used these to run dedicated sessions to test their design codes. It was believed that this approach may incentivise developers to adhere to the design code once it was adopted.

35 The Design Council

Image: David Lock Associates for Gedling Borough Council

“We are sharing the draft of the code with the developers. But we are making sure we haven’t been sucked into accepting what they express as red lines. We know that this first iteration needs to be really challenging for them, so that we can have a tough conversation, as opposed to going through a comfortable process, accepting everything they’ve said, and putting that into a code that doesn’t cause them to change very much.”

“Currently, it wouldn’t technically prevent the developer from coming forward with a new design code. I think probably the best tool we’ve got is that there’s been lots of public and stakeholder participation in this process. And so, putting all the regulations and legislation to one side, are you really going to shoot yourself in the foot as a developer and go against all that? Especially when the code’s had all this exposure.”

Spotlight on Gedling Borough Council: Working with developers

Gedling Borough Council has an established developer’s forum for engaging and working with local developers. The forum, which meets quarterly, has garnered positive feedback and fosters a productive working relationship between the council and developers. With approximately ten to 15 developers regularly attending each meeting, the forum facilitates a twoway flow of information and provides an opportunity for developers to share challenges they face, allowing the council to gain a deeper understanding of their

concerns. Importantly, the discussions in the forum do not revolve around specific sites but focus on broader issues. The council utilises the forum to provide developers with a heads-up on emerging policies and seek early feedback. This approach ensures that developers are informed about upcoming changes in the planning system, such as the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the Gedling design code, as well as environmental considerations such as biodiversity net gain.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 36

Take-aways for future design coders

Encourage engagement with diverse stakeholders:

Frame consultation activities with statutory consultees and colleagues as an opportunity to shape direction of future placemaking, align workstreams and create partnerships.

Understand individual aims and priorities for the design code, to help reach a consensus on what the code should address.

Use stakeholders’ expertise to sensecheck the vision and develop next steps.

Use an external mediator to bring objectivity and help diverse stakeholders reach consensus.

Encourage engagement from councillors:

Frame design codes as an opportunity to deliver places that build on a community’s vision.

Outline how design coding can boost local support for developments and can help councillors make informed decisions on planning applications.

37 The Design Council

Stakeholder engagement activities

Image: Mansfield District Council, PJA and Urban Design Doctor

3. Analysis: Scoping and Baseline

This section summarises learnings from the Pathfinders on establishing the geographical area to be covered by the code, determining the policy areas it will address, gathering evidence for analysis to underpin and inform its content, and compiling scoping and baseline assessment reports.

More details on this step are available in the Pathfinder Insight piece: Design code in practice.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 38

Over half of Pathfinders were still undertaking scoping activities eight months into the programme, and baselining activities were continuing nine months in.

Images (this page and opposite):

Bournemouth, Christchurch & Poole Council

Pathfinders found scoping more challenging and time-consuming than they had anticipated, and with more tasks than they had planned for. Over half of Pathfinders were still undertaking scoping activities eight months into the programme, and baselining activities were continuing nine months in.

For those developing strategic, authoritywide codes, the task of scoping and baselining across multiple sites or at an authority-wide level was a big challenge, due to the complexities they faced in addressing diverse character areas, land uses and building typologies. A deficient scoping stage, for these Pathfinders in particular, resulted in being over ambitious and losing strategic focus by trying to address too many policy areas, applying too many area types, and taking on a disproportionate amount of work. Overreaching was not experienced solely by those developing authority-wide codes. Some developing area-specific codes, such as for town centres or urban extensions, found that they could not determine the appropriate level of detail when deciding area types, as a result of insufficient clarity on the key issues and what was out of scope.

“From the codes that I’ve seen, people try to do too much. The majority of the time, the things that go wrong are quite simple. It’s best to focus on getting the basics right.”

Pathfinders agreed that development management officers were essential to determining the scope, as they could share the main issues that arose repeatedly in processing planning applications, and which could easily be addressed. Finding and identifying these repeated and basic issues could bring huge benefits.

“Ask your development management officer: ‘What are the three things that if every developer did better would raise design quality?’ That’s where your coding is going to have the most impact. Where you’ll get the most benefit for least effort.”

One Pathfinder said that they recommended looking at design tools and guidance when scoping, such as Building for a Healthy Life and Streets for a Healthy Life, and reflecting as a team on whether they were being used in their area.

39 The Design Council

Pathfinders found that the baseline assessment was important not only for rigorous scoping and ensuring that the design code was based on reality, but also provided the evidence base justifying the requirements set out in the code.

“It’s strong. Everything stems from the baseline assessment. Everything in our code is based on research and observations.”

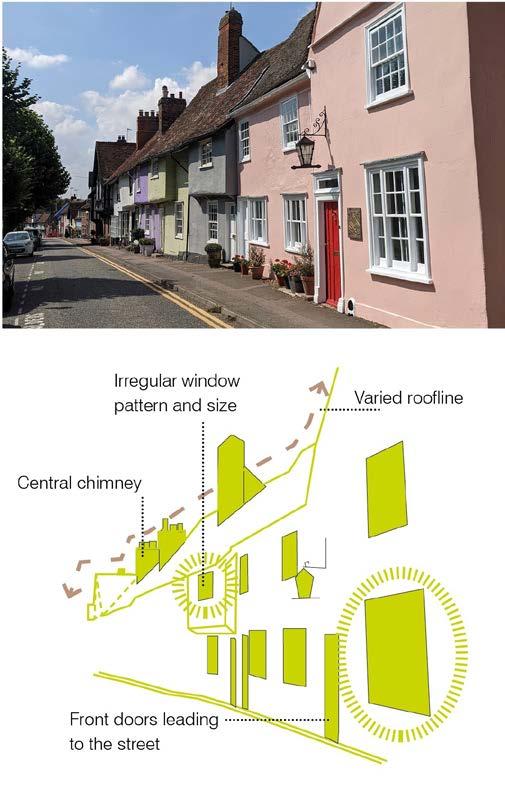

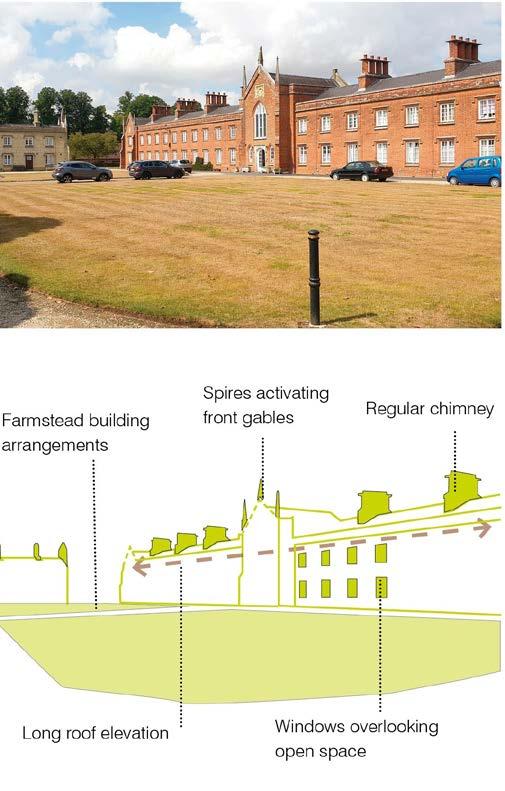

Pathfinders with a pre-existing evidence base from local plan, neighbourhood plans, and/or masterplans used this material to start their baseline evidence analysis. This included conservation area appraisals, local urban characterisation work outlining how settlements had evolved historically and survey detail on landscape, topography and drainage. This information supported determining area types.

Pathfinders that did not have access to high-quality or up-to-date data for their baseline found it difficult to obtain primary data to support the ongoing analysis, such as tree coverage or utilities’ data. These data gaps hindered progress in analysis and building baseline evidence.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 40

Images: Surrey County Council (top left),

Design for

Homes for Uttlesford District Council (top right and bottom)

Take-aways for future design coders

Allocate enough time for scoping

Ensure the team is definite about the code’s aims and ambitions and criteria for the code.

Use evidence and local priorities to narrow down key strategic priorities for the design code, and develop relevant criteria and metrics for these priorities.

If starting scoping is a struggle, try: Thinking about what three things would raise design quality the most. Looking closely at what makes a place special to understand how these can be enhanced through coding.

Focusing on particular types of sites across a wider area such as at-risk heritage buildings and areas, infrastructure, streets and active travel routes or green and blue infrastructure. Starting from baseline evidence and community consultation findings.

Identifying one or two sites as pilots and extrapolate from there, recognising that codes are iterative, and can be added to later.

41 The Design Council

Image: City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

4. Setting a design vision and coding plan

This section summarises learnings from the Pathfinders on setting a vision for their coding area, allocating area types and preparing a coding plan that effectively reflects both.

Pathfinders struggled to pin down an overall vision for their coding area, and often underestimated how long it would take to clearly define their vision and objectives.

Identifying the character of an area helps to determine the priorities of a design code. However, a lack of knowledge on how to use area types meant some Pathfinders struggled to determine a proportionate number of area types for the scale of their code. Some Pathfinders chose to divert from the NMDC guidance and developed alternative approaches to using area types. These included:

• Developing a code from local priorities, rather than area types.

“The NMDC suggests the approach of using area types, but we never really set out to do it that way… maybe it could work for some authorities, but we just didn’t want to be too prescriptive. It was crucial that we linked into those high-level objectives and tried to bring them down into the detail of what that actually looks like on the ground.”

• Using area types to develop a series of area-specific codes each with their own objectives, which were then used to define over-arching design principles:

“We developed site-specific codes and worked with stakeholders and officers to define different character areas within the town centre… from there we were able to create good design principles and coding elements that would be applicable across the whole town centre, regardless of where you are.”

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 42

Image: BPTW

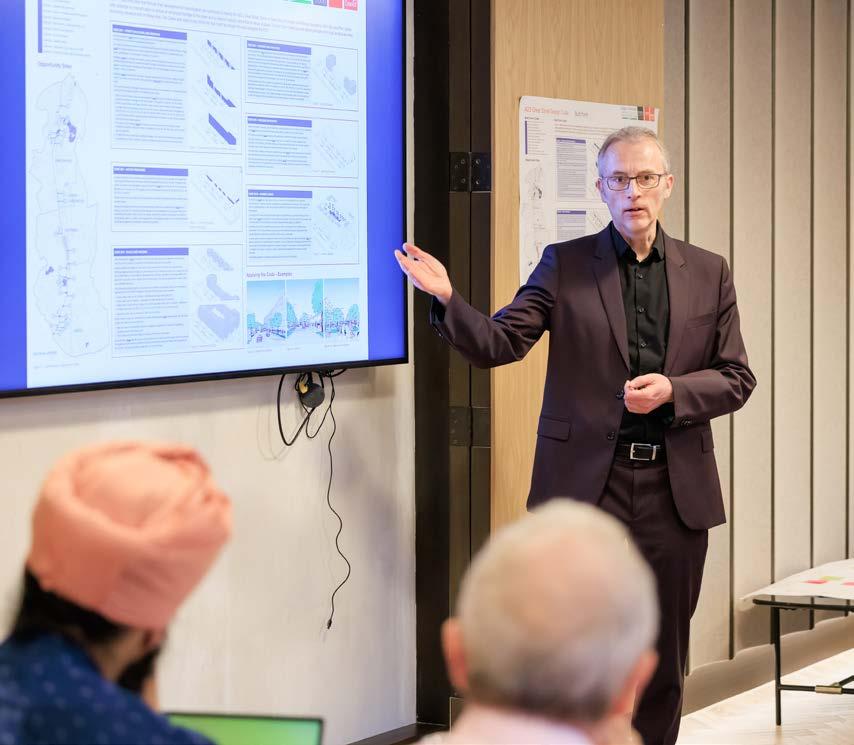

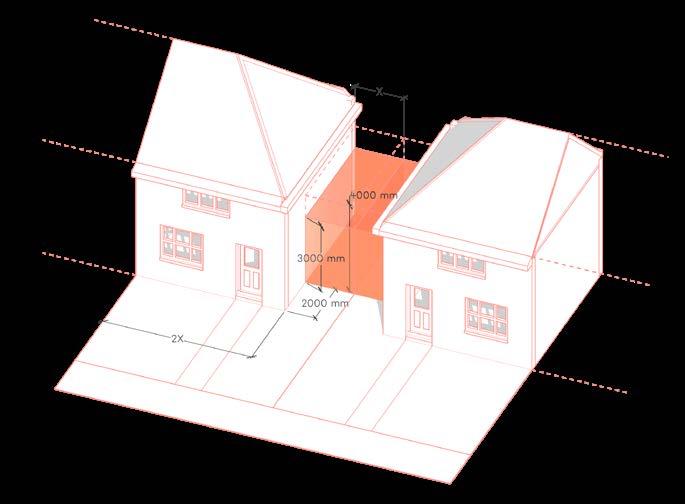

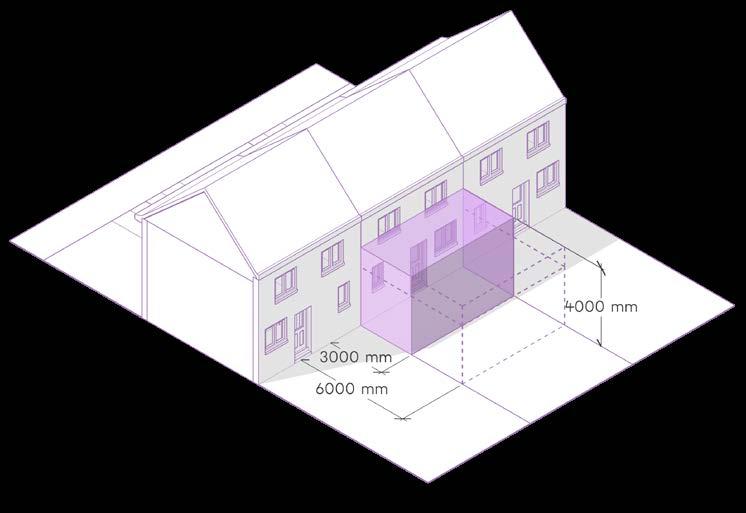

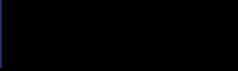

Design vision diagrams for Medway and Reigate & Banstead design code

• Pathfinders coding for authority-wide or large areas found area types were particularly important for their design code. These were not necessary when coding for a small area – for example, one local authority developing a sitespecific code, did not use area types but did identify building types to which different codes applied.

Another challenge was determining the appropriate level of detail for each scale of coding. Some Pathfinders disagreed about this within their teams. By the end of the programme most Pathfinders understood that the more specific the code, the more must-haves it could include.

“At a district level, there will be a high proportion of ‘shoulds’. As you zoom in with a greater level of certainty to a neighbourhood level, or even a parcel level, the frequency of must-haves increases.”

Pathfinders in rural areas found it challenging to apply predominantly urban typologies to their contexts. There was more scope for developing a character area type ‘from scratch’ when referring to greenfield sites, compared to urban settings with an established context.

“The type of development that we’re seeing is mainly greenfield developments on edges of existing settlement. “[This] is where the opportunity to make the most impact in terms of design quality is...but we don’t have the guidance to develop area types from scratch.”

43 The Design Council

Image: BPTW

Coding plan for Chatham Town Centre, Medway

Spotlight on Trafford: Authority-wide coding

Trafford’s design team defined area type boundaries using their collective knowledge and experience of working and living in the borough. The draft area types were then validated through community engagement. Some areas were straightforward to define, such as those aligned with the Council’s Core Strategy and Local Plan allocations for high-density development. However, the suburbs proved to be more challenging because of the variety of layouts and built form found in the neighbourhoods. Consequently, these area types were simplified to a single suburban area type where development is anticipated to primarily come forward on infill sites.

The coding plan includes several area types. Each area has its own distinct design requirements in addition to the general authority-wide strategic design principles applicable to all relevant developments.

These principles have been established to drive forward high-quality design. Each design principle is supported by a set of clear guidelines. This must be followed for all development in the borough, and development proposals must demonstrate how these principles have been addressed through the evolution of the scheme. Applicants are required to locate their site and area type from the coding plan to determine which sections of the design code are applicable to their development.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 44

Images: Urban Initiative Studio

Take-aways for future design coders

Use accessible language and be highly visual when developing a vision:

Ensure it’s clear and concise but detailed on local challenges and aspirations.

Illustrations can help demonstrate how the materials’ palette, building facades, roof profiles and other elements work together explore creative ways of communicating the vision.

When determining area types, proceed from what is unique:

Ensure area types are particular to their context, linked to the overall vision and characteristics the community cherishes.

Ensure area types reflect diversity of typologies to create/characterful neighbourhoods.

Include a limited number of area types, to avoid confusion on implementation.

Define area types through built form as a priority, followed by site edges and landscape:

Consider intersections between street, landscape and buildings.

Use cross-sections or sketches, as well as plans, to understand the relationship of area Types to each other and the boundaries between them.

Use mapping techniques such as morphological analysis to feed into the specifics of the code.

Take an integrated, cross-disciplinary approach to the delivery of functional green and blue infrastructure when defining area type.

In rural areas, divide the code into different scales

Consider settlement form, landscape setting, topography, context and the relationship between settlements.

Design vision diagrams for Medway and Reigate & Banstead design code

45 The Design Council

5. Coding

This section summarises learnings from the Pathfinders on writing the code and how best to format it, including the type of language which should be used and visual components to ensure its accessibility and useability. It also covers how to ensure the code accurately reflects the design vision, setting a clear and enforceable minimum standard.

More details on this step are available in the Pathfinder Insight piece: Presenting codes.

Writing the code took time and expertise to do well and, as with previous stages, it took many Pathfinders longer than anticipated to refine language and avoid repetition. Pathfinders also found themselves having to cut content and code requirements, to ensure that the document was accessible and useable.

“Don’t underestimate the amount of time needed to churn through everything and come out with a workable code”

The prescriptive and metric-based nature of a code is a departure from the writing style commonly employed in planning policy, local plan supporting text or SPD guidance. The process of writing and refining the code to become an accessible document therefore took Pathfinders longer than expected. Graphic design and illustrations were used to develop a visually consistent document that increased legibility.

“The actual development of the code content is taking longer than expected, but we are keen that a thorough process is followed and corners are not cut.”

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 46

Images: Be First

Examples of illustrations used in a design code

“It’s quite a logical, structured document. Each coding element is broken down into page spreads. With a consistent format from a graphic design perspective, we’ve used the colours from the NMDC. It was something that I felt quite strongly about in terms of usability.”

Some Pathfinders used a compliance checklist showing applicants which elements they should comply with and which elements have a level of flexibility, to help create a more legible and enforceable code. Additionally, viability testing can help to demonstrate that requirements in the code are going to be viable to deliver, which will help make the code a more practical and useful tool.

Examples of illustrations used in a design code

47 The Design Council

Images: LDA Design

Take-aways for future design coders

Ensure the code is enforceable

Explain in the code how it is proportionate to what it is trying to achieve.

Be transparent about reasoning behind musts and how they relate to the vision.

Be clear where there is flexibility in the code.

Provide compliance checklists to aid users (applicants and DM officers).

Language should be unambiguous about definitive code requirements.

Be concise and use straightforward language, avoiding non-committal language, such as ‘must aspire to’ or ‘must consider’; keep musts tangible and measurable.

Set definitive figures for definitive requirements, for example, ‘must increase by 50%’

Use graphics and illustrations precisely

Use graphic design to create a strong visual hierarchy through elements such as text size and colour-coding reduce text: use diagrams and images to communicate important ideas quickly, annotate graphics and photographs to make their intent explicit when using axonometric, use the same drawing repeatedly to show different considerations of design; for example, sustainable drainage in one and economics in another.

Use photographs or sketches that represent place well

When choosing imagery, ensure that these completely align with your design code requirements to avoid any misinterpretation. Remove the elements that you consider inappropriate or use an alternative illustration instead.

Where landscape is key to local character, use imagery that highlights this, such as views of distinctive landmarks.

Use images that reflect the diversity of topography and character areas in the code

If using images from outside the code area, use annotations to explain the relevance of the images within the local context,

Photographs of local developments accompanied by tick/cross-boxes and explanations are helpful when using illustrations to communicate an aspirational vision.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 48

6. Testing: Adoption and implementation

This section summarises how to test completed codes, to understand how they will be used and how they might be improved. So far there are limited learnings from this phase, as Pathfinders are just beginning to test their design codes following the completion of the programme, implementation of codes, including the importance of training for officers and councillors.

Pathfinders are testing their design code with developers, development management officers and local communities to understand:

• usability, ensuring it can be used on a day-to-day basis

• robustness, ensuring it works in different decision-making scenarios, and whether there are gaps

• design and legibility, ensuring it is easy to navigate and read.

Take-aways for future design coders

Test draft codes:

Test codes against previous permissions, live planning applications and in pre-application stages.

Test codes from various user perspectives, including developers, development management officers and communities.

Test both the physical document and any digital assets.

Be aware of the interdependencies of any changes made to the code (within the code itself, and in relation to other guidance).

Test the document’s useability to ensure it is easy to navigate and follow, and to ensure that its coding is directly reflected in emerging proposals at pre-application and application submission stages, and in decision taking at local level, and/or on appeal/call in/recovery by the Secretary of State.

49 The Design Council

a. Developing digital codes

Pathfinders found that digitising and formatting a design code for websites took longer than anticipated. Some Pathfinders were disappointed by the cost and a lack of available expertise inhouse to support.

Pathfinders also noted that the website or digital platform, when developed, would need periodic updating, and they expressed concerns about who would assume responsibility for keeping the code up-to-date.

Take-aways for future design coders

Introducing digital expertise into planning departments is very important, as Pathfinders found that graphic design and digital teams in-house were unfamiliar with the technical aspects of developing planning documents.

“It’s a real skill: you need to have the planning knowledge to be able to produce something for planning, so just being a graphic designer isn’t enough. I have been in talks about getting us refreshed and trained on these things and getting us access to the software so that we can take it forward ourselves, rather than having to use another department.”

Prioritise user experience and functionality over aesthetics:

Develop the user journeys at the same time as developing the platform, including:

• Identifying the different users and their relationship to the code

• Establishing the common entry points and barriers for each type of user

Remove barriers through iterative user testing.

Be explicit about the actions users are expected to take, when navigating the digital tool (for example, “read this”, “submit an application here”) place other guidance documents together with the code on the digital platform.

Identify a site owner to maintain the digital platform.

Work with others to make the digitisation of the code easier

Share learning about developing digital codes with other coding teams.

Consider jointly commissioning or procuring the development of the digital platform with another local authority.

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 50

Examples of digital codes produced by the Pathfinder cohort

51 The Design Council

Images: Surrey County Council

Examples of digital codes produced by the Pathfinder cohort

Design Code Pathfinders Programme Evaluation Report 52

Images: Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council

b. Adoption and implementation

Where Pathfinders were using their design codes to expand on an up-to-date, adopted local plan policy by progressing a proposed SPD, this was an easier process than for those where a new, emerging local plan was being prepared, or a local plan review was underway.

“Initially, we’re going to adopt it as a supplementary planning document. Which isn’t ideal in a way that doesn’t have as much weight as a local plan. But it enables us to get it in place reasonably quickly and start using it and testing it.”

“The design code will tie in with the local plan review, so that we can get them on the same cycle and they’ll be kind of brother sister documents together.”

“I think we’re fortunate with the timing of the local plan to be able to put the district wide code in as an appendix.”

Take-aways for future design coders

c. Training

Despite NPPF policies promoting the use and value of design codes, some Pathfinders were concerned that if codes were not accessible and easy to understand they simply would not be used. They believed that a code needed to be accompanied by training for officers and councillors.

“If people aren’t properly trained in how to use and implement it, it’s not going to stick. When we briefed the consultants, two training sessions were built in from the start, which they will deliver. But we have also started thinking about the other support that’s going to be needed for officers within our team.”

Support the adoption and implementation of the design code:

Training development management officers in using the design code is essential for implementing the code.

If planning to combine smaller-scale (site-specific or areaspecific) codes into a larger-scale authority-wide code, then a further piece of work will be necessary, to develop guidance on compatibility.

Define timescales and approach to reviewing the code: Should be reviewed regularly, even if just to check it is still up-to-date.

Decide in advance when the code will be updated, and by whom.

53 The Design Council

Monitoring and Evaluation 2

In this chapter, we summarise the experience and challenges of the Pathfinders teams in applying the National Model Design Code, with further detail provided on teams developing authority-wide codes and Neighbourhood Planning Groups.

a. Experience using National Model Design Code

Pathfinders reflected that the content of the NMDC was easy to understand but many found it difficult to navigate. A lack of confidence in implementing it in practice resulted in some Pathfinders being over-ambitious, by trying to cover too many themes. On reflection, Pathfinders felt that the NMDC could be improved on the following topics:

More guidance on how to determine area types and some more area types for different contexts for instance rural and non-residential. Pathfinders working on rural codes found that the code offered few relevant examples and guidance.

“The NMDC doesn’t identify the areas and types that we have in [our very rural area], apart from the straight ‘rural’… I think there are quite a lot of elements of the NMDC that don’t apply to us. We might be covering them because there’s an expectation to, but possibly we don’t need to. Instead, we should be more focused in the priority areas that apply to very rural areas.”

Pathfinders working on authority-wide design codes particularly struggled to make the NMDC guidance apply to their context and asked for case studies and tools to support them. Pathfinders also needed support on avoiding their high-level code becoming guidance, rather than a set of coded development requirements. It was noted that further training would have been useful for teams developing authority-wide codes.

55 The Design Council

Image: BCP Landsdowne

“Borough-wide codes are missing from the NMDC, and it is a real challenge to do these, particularly where you’ve got varied character… A particular challenge is how you word the code. For an authority-wide design code, being strictly numbers-based is difficult because we’ve got so many different area types that the code becomes unwieldy.”

“What we [those of us developing authority-wide codes] still desperately need is some guidance on coding: how can we produce a code that’s not numbers-based? For example, for a development to be well-designed, it needs to meet all of these specific points, but our confusion is that that’s really more like a guide.”

Some Pathfinders thought the NMDC was asking them to produce a prescriptive code that pre-determined what high-quality design looked like, and which might inhibit an applicant’s flair and keep their area set to current typologies for years to come.

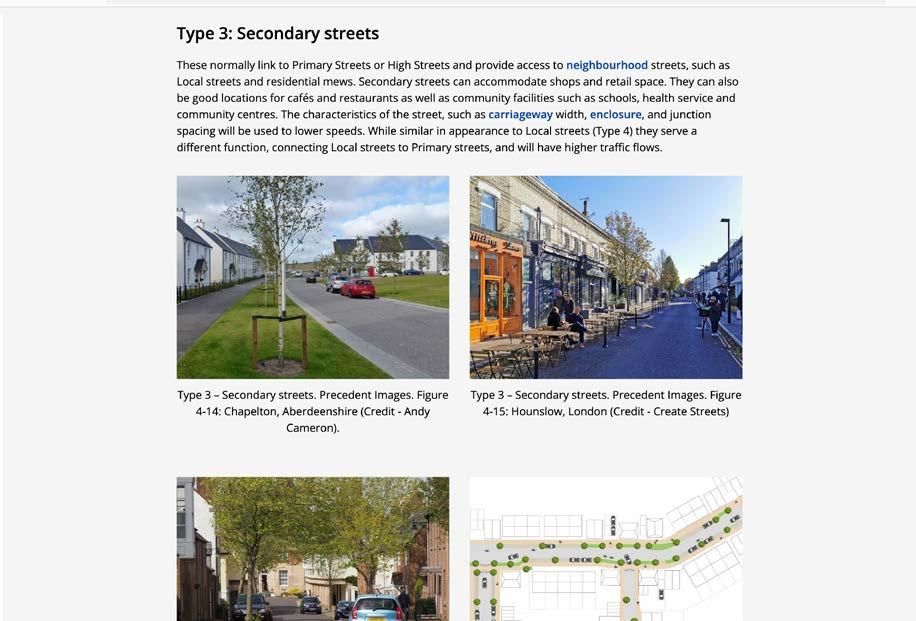

b. Developing authority-wide codes