134 On Oxos, Evros and Pharmaka Metallica: An Ancient Greek Perspective on Biotechnology for ‘New’ Pharmaceuticals (Fifth to Third Century bce)

Effie Photos-Jones

142 SPHAIRA

146 Sphaira: The World as Sphere

Vinzenz Brinkmann

156 A Statue of the Goddess of the Hunt as a Static Planetarium?

Vinzenz Brinkmann, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann

168 ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM

174 The Astonishing Antikythera Mechanism: Decoding an Ancient Greek Calculating Machine

Tony Freeth

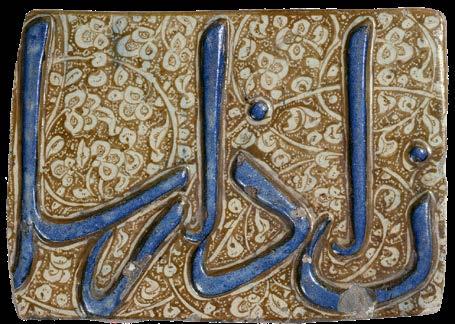

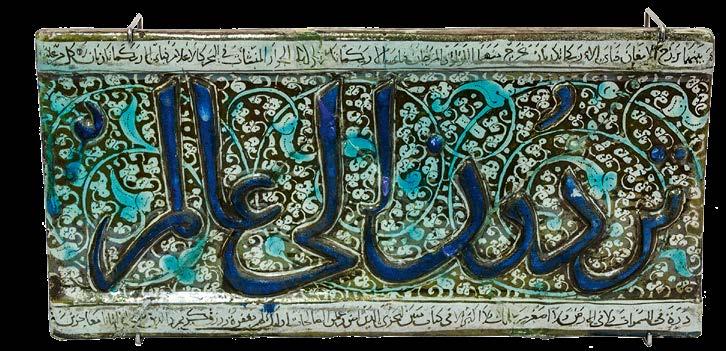

202 ARABIC-ISLAMIC CULTURAL SPHERE AND ASIA

214 The Golden Age of the Sciences in the Heyday of Islam, Including the Timurid Renaissance: A Brief Introduction

Vinzenz Brinkmann

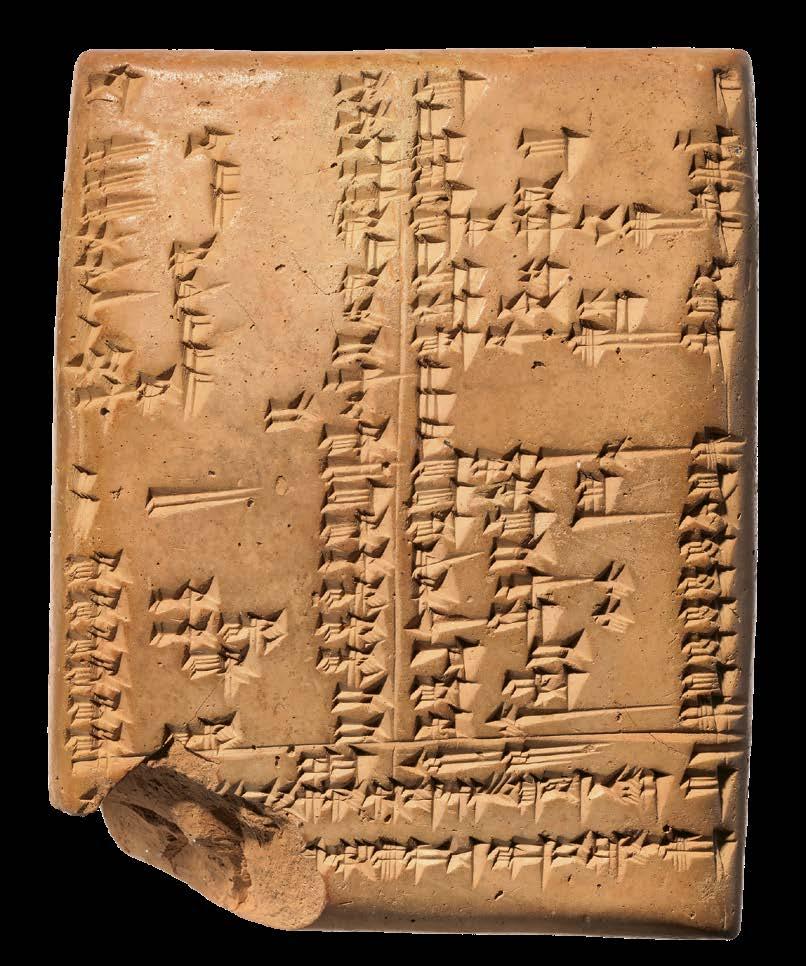

220 The Translation of Greek Heritage and the Development of Scientific Language in Arabic

Roshdi Rashed

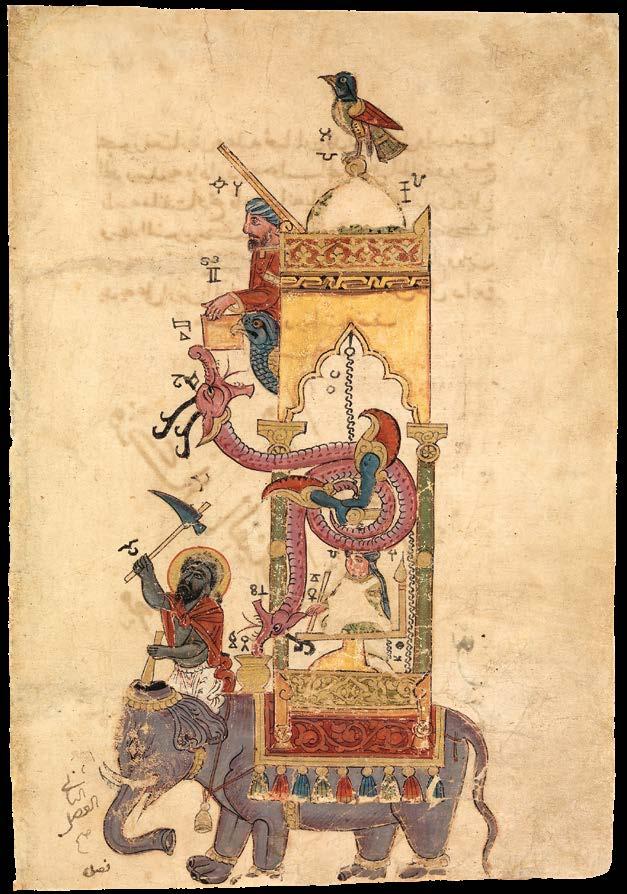

230 Automata in the Islamic World (Eighth to Thirteenth Century)

Martina Müller-Wiener

242 Knowledge in Ancient Asia: A Brief Insight

Vinzenz Brinkmann

246 EUROPEAN MODERN ERA

252 The Measuring of the World During the Modern Era in Europe and Its Dependence on Antiquity and the Arab-Islamic Cultural Sphere: A Brief Excursus

Vinzenz Brinkmann

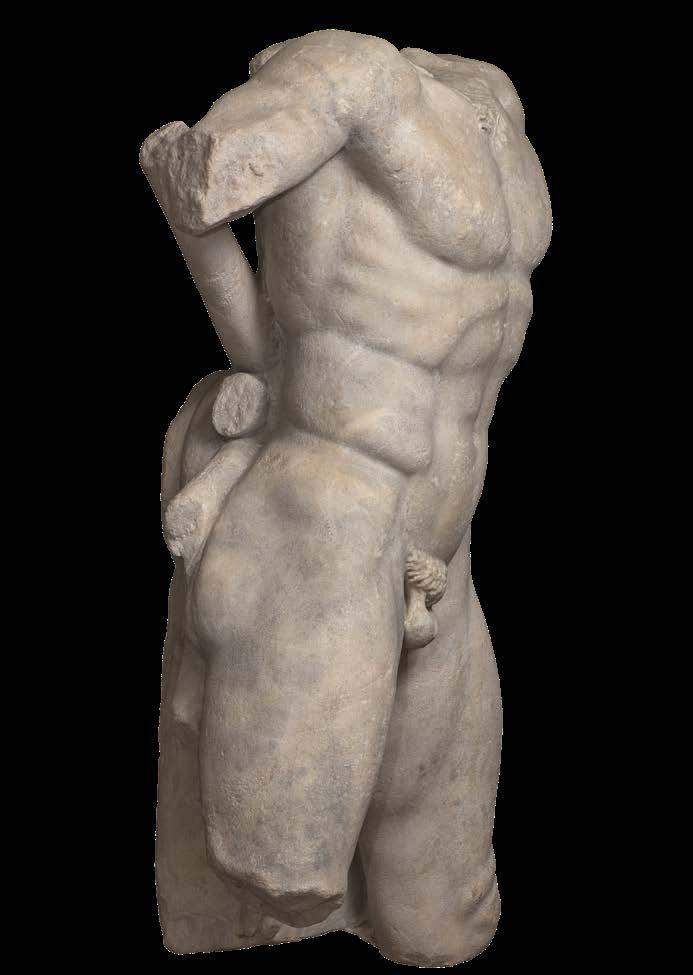

Marble statue of the goddess Athena, Roman replica of a Greek bronze original by the sculptor Myron, marble, 1st cent. ce Athena was the god-

dess of the arts and sciences and thus directly personifies the Greek concept techne, which refers to art and technology in equal measure. (Cat. no. 029)

How Our Future Was Invented: An Introduction to the Frankfurt Exhibition Machine Room of the Gods

Vinzenz BrinkmannClearly, we have some catching up to do. The importance of the natural sciences (exact sciences) and technology (engineering) for art has obviously been known to people of all eras … except in the twentieth century. Right up to the final years of the nineteenth century, there were pioneering publications on the history of the natural sciences and their significance for art. No one was bothered by the close relationship of technology and aesthetics, which was instead regarded as a matter of course, for example, in the ancient Orient, ancient Greece, and in the Golden Age of Islam. The Greek word techne and the Arabic word ṣināʿa are close to each other and unite both aspects seamlessly.

In the twentieth century, techne, which had always been understood as a unity, was wrongly split up. It is now time to close this rift in order to do justice to art and its history.

The German art historian Horst Bredekamp has not been the only one to call for this path to reconciliation, but he did so forty years ago in the context of an activity at the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung.1 In 2012, he underscored his conviction: ‘With regard to the history of technology, the same thing holds as for the history of art: in isolation, disciplines must sharpen their contours, but if they remain in it, they will atrophy as if in solitary confinement.’ 2

Whereas Bredekamp’s reflections mark a coup that remains limited to the modern era in Europe and more specifically to the aspect of the cabinet of curiosities (‘Kunstkammer’), the Frankfurt exhibition project Machine Room of the Gods spans a broader arc and is aware that, given the necessary brevity, this more comprehensive view is not possible without omissions and simplifications.

Under the title Aristoteles: Lehrer des Abendlandes (Aristotle: Teacher of the Occident), Munich-based publishing house C . H . Beck issued an important publication on the life and works of the Greek philosopher and natural scientist.3 Its subtitle, ‘teacher of the occident’ is laden with pathos and curtails the global significance of Aristotle, someone who was influ-

nant colour is artificial pigment Egyptian blue, which was manufactured in a complex chemical process.

(Cat. no. 013)

(Cat. no. 008)

enced by the thinking and research of the ancient Orient and who in his turn, particularly as a natural scientist, had an extraordinary, centuries-long impact, especially on the Arab and Persian cultural spheres. In the Christian West, which was somewhat hostile to science, the enlightened and scientific side of Aristotle was downplayed enormously, and as late as the thirteenth century professors at the Sorbonne who taught this side of Aristotle were condemned and excommunicated (the so-called Condemnations of Paris).4

The case of Aristotle is cause for reflection and perhaps adds lustre to the thesis that the intellectual achievements of ancient Greece are not so much a ‘European heritage’ as they are part of the Oriental world and are to be understood as a ‘global heritage’ on whose foundations that world was build and which, after the decline of the ancient Greek world, were absorbed by Arab-Islamic scholarship and forcefully pursued.

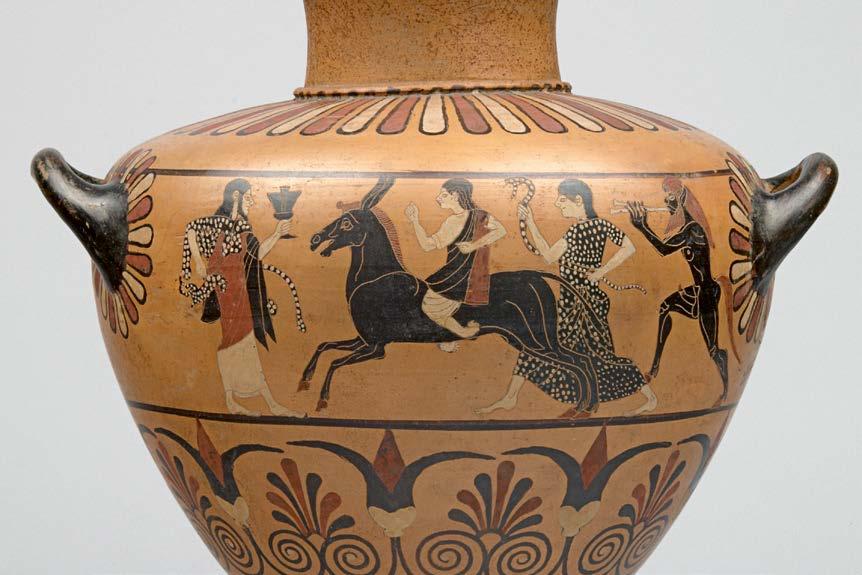

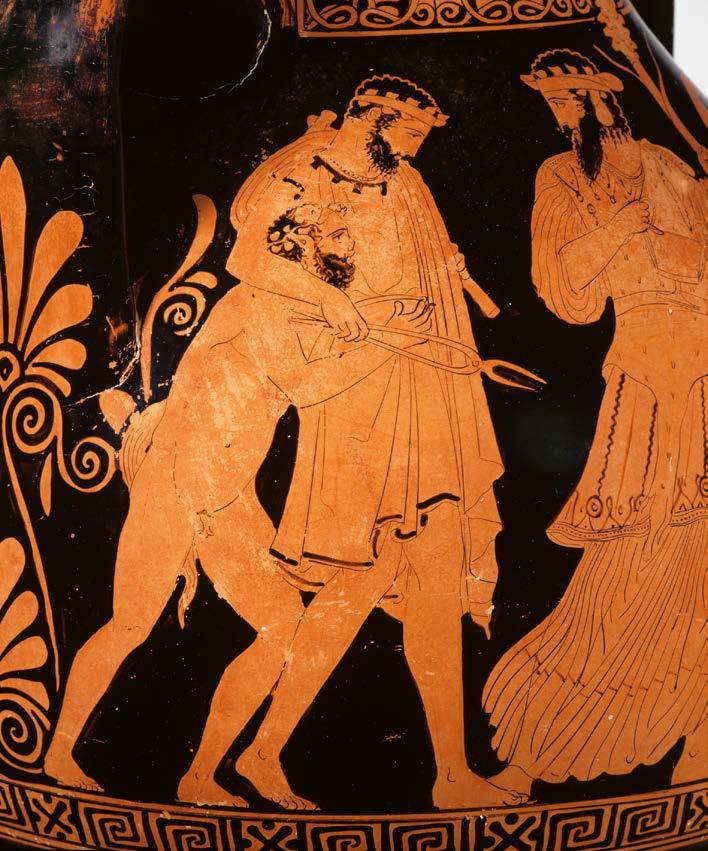

With its work on three aspects – that is, (a) fictive technology in ancient myth, (b) the international history of science across five millennia, and (c) mechanical animation in ancient, Islamic, and European art – the Frankfurt exhibition embeds into the existing collection of the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, which also covers a history of five millennia, and profits from the resulting dialogues that necessarily resulted.

A polychrome statuette in Frankfurt shows Ptah (fig. 3), the Memphite god of creation and precursor to Hephaestus and Vulcan; the important sarcophagus lids of Takait (fig. 4), on the other hand, reveal rich remnants of ‘Egyptian blue’, an extraordinarily successful product of Egyptian chemical research.

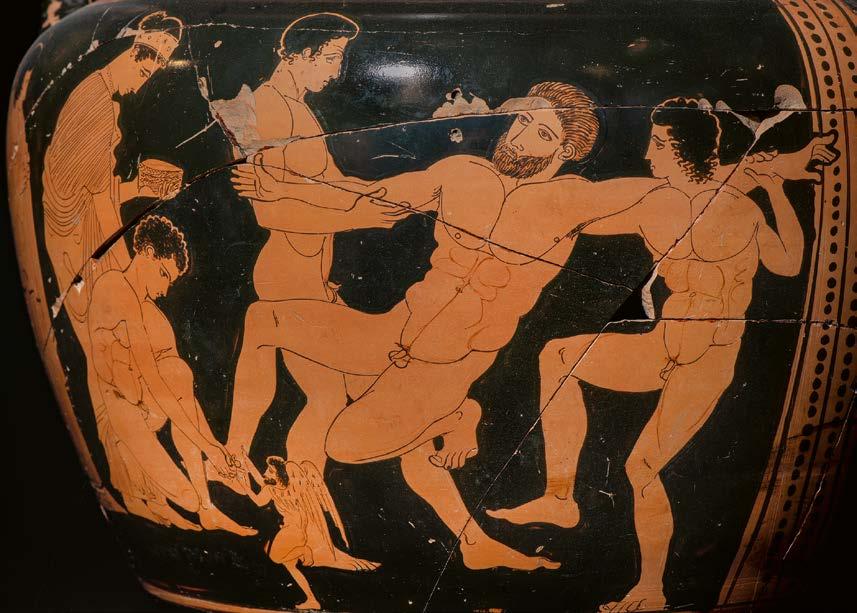

The famous Roman marble copy of the Athena by the bronze sculptor Myron, who was renowned not only for his formal achievements but also for developing a special alloy, depicts the goddess, who more than anyone else in Greek mythology stood for enlightenment, research, art and technology, at the moment she is discarding the diaulos, a technologically complex double-reed musical instrument that she had designed herself (fig. 2).

The Liebieghaus collection contains the only surviving large-format portrait of Alexander the Great, which was produced in a Greek workshop (fig. 5). It comes from Egypt, was made from local alabaster and shows a personality whose efforts to gain power profited from science in general and from his teacher Aristotle in particular. In this spirit, soon after Alexander’s burial in the city he had founded, the epochal research institution ‘Library

‘The Machine Room of the Gods’ at the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung in Frankfurt

of Alexandria’ was established. The historical figure of Alexander the Great was a positive narrative reference that permeated the collective memories of both Western and Eastern cultural spheres (Arabic: al-Iskandar al-kebir, Turkish: Büyük İskender).

As the German Pope Benedict XVI , a proven scholar of religion, aptly describes, the young Christian faith drew on the ethical convictions of the Greek thinkers. The great Fathers of the Church, who were sometimes familiar with pre-Christian philosophers and intellectuals, and of whom the Liebieghaus possesses impressive late medieval ‘portraits’ (fig. 6), found themselves in serious conflict. Augustine of Hippo (353–430 ce), for example, who before his change in faith had been devoted to the writings of the Roman legal scholar and historian Cicero (106–43 bce) and the Roman Neoplatonist Plotinus (205–270 ce), strove for a concept of truth and a concept of time while expressing decidedly anti-Judaist and anti-Semitic views (Tractatus adversus Judaeos), calling Jews ‘sinners’ and ‘stirred-up filth’ in his writings and advocating an anti-corporeal sexual ethic and eternal punishment in hell, thus laying the foundations for the ‘doctrine of original sin’ and the ‘doctrine of purgatory’.

The European medieval department of the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung contains a spectacular marble portrait of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (fig. 225). His efforts to get closer to the Arab world through language and research illustrate the cultural and intellectual gap between the late period of the Golden Age in the Arab-Islamic sphere and Europe, which closed itself off from free thinking for centuries.

With the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and Arab Andalusia knowledge of antiquity and Islam increasingly penetrated the Christian West. In the fifteenth century, the Italian Renaissance sought a direct connection to Greek antiquity. For example, the sculptor Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, known as Antico (1460–1528), presented his view of the ancient image of the god Apollo in the form of a bronze statuette now in the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt (fig. 7).

Antico’s contemporary Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) had been trained only as a painter but nevertheless strove to ‘re-enact’ the kind of polymath we encounter in antiquity and Islam. If we consider that Leonardo was concerned with outward appearances, it becomes understandable why many of his ‘technical drawings’, with which he included no explanatory texts, cannot be implemented. Rather, these images should be seen as conceptual designs that go far beyond what was feasible in his day. It sometimes seems as if, within his own lifetime, he wanted to catch up on all the scientific knowledge of antiquity and Islam for himself personally and

Portrait

Alexander

Great, Egyptian alabaster, Egypt, 150–50 bce. As a child, Alexander was perhaps taught by Aristotle, the most important Greek polymath. Alexander created a great

empire reaching from the Indus to the Adriatic coast. This was also achieved through the willingness to incorporate the numerous cultures of the empire’s territory.

(Cat. no. 031)

6 Portrait of Augustine of Hippo (354–430 ce), limewood, Worms, 1489–96. Augustine was one of the four great Church Fathers of Western Christianity. His writings, which document

his search for the truth but also report on original sin and belie his anti-Semitic attitude, were intended to serve as guidelines for the faithful.

(Cat. no. 072)

Apollo of Belvedere, Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, Italy, 1497–98, H. 41.3 cm, W. 22 cm, Frankfurt am Main, Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, inv. no. 1286. This bronze

statuette – partially gilded with silver inlay in the eyes – is, like with other versions, modelled on an ancient marble sculpture, the famous Apollo of the Vatican Belvedere.

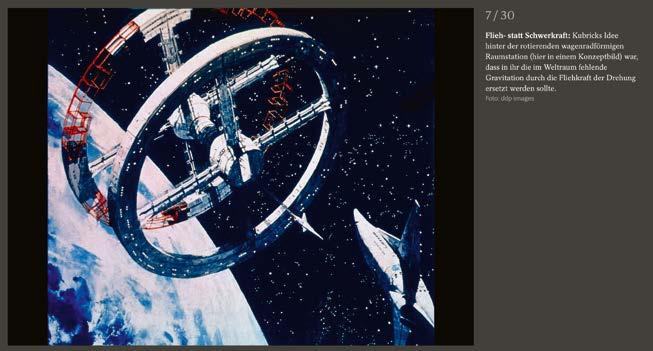

for a laggardly Europe which had fallen behind, and to develop further practical, in some cases visionary, scientific applications. For example, his diaries include a technical drawing of an automotive vehicle,5 which can be regarded as a simplified variant of the ancient automatic theatre of Hero of Alexandria, which even included axes set at ninety-degree angles that changed automatically.

A few years ago, the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung made the spectacular acquisition of a portrait bust of the polymath Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) by the Parisian sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1818) (fig. 8). In the tradition of Greek philosophy, Rousseau illuminated the role of humans in society and is now considered to have paved the way for the French Revolution, which opened up new latitude for the rational, scientific understanding of the world in the spirit of antiquity, of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad as an example of the Golden Age of Islam, and of the Italian Renaissance.

Current Activities

The exhibition Machine Room of the Gods: How Our Future Was Invented has benefited extraordinarily – thanks to the willingness of numerous colleagues and artists to collaborate – from the latest scientific and artistic achievements in the field of the history of science. Only thus was it possible to exhibit in Frankfurt the spectacular results of the French excavations of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s extravagant Roman palace complex with its large and luxurious banquet hall, which was driven by a rediscovered enormous mechanism like a kind of revolving stage under an artificial starry firmament. Only thus was it possible to bring to life in our exhibition the mechanical miracles described in detail by the Greek writer Hero. These include the completely automatic theatre which presents a tragic tale in several acts with lighting and sound effects, and the jet-propelled carousel of figures that presumably operates with cinema-like visual effects. Thrillingly, two extraordinarily detailed bronze statues of a child hunting a partridge could be tentatively reconstructed as elements of such a cinematographic zoetrope.

The contribution on the Antikythera Mechanism can be considered a world premiere; it was curated by Tony Freeth himself, and three rooms are dedicated to it. Research on this highly complex apparatus was advanced in recent months, so that the full understanding thus achieved can now be demonstrated for the first time on the basis of an elaborate multimedia presentation.

Bronze bust of JeanJacques Rousseau, Jean-Antoine Houdon, France, 1780. The scholar Rousseau (1712–78) argued that

the decline of man he diagnosed was based on the ‘progress’ of civilisation and technology. (Cat. no. 083)

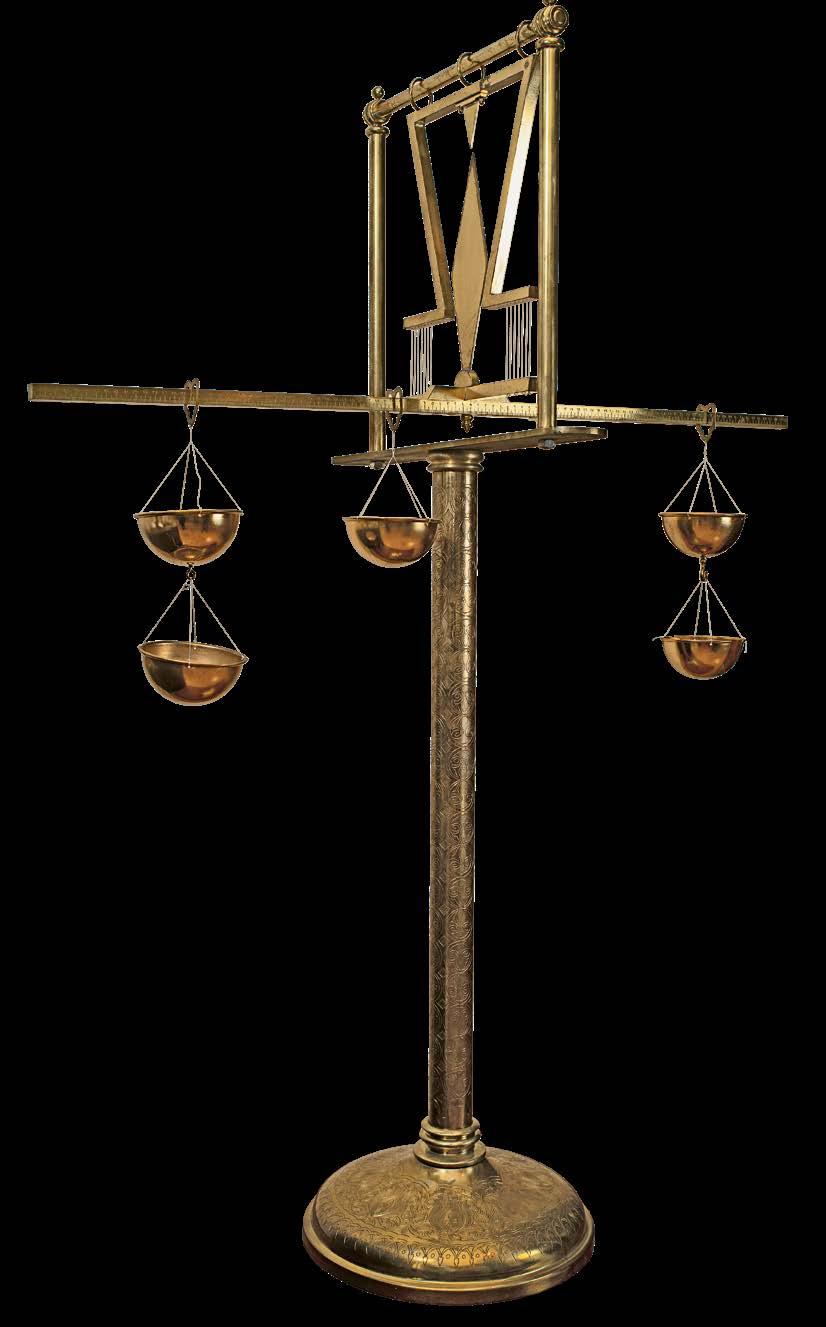

Thanks to the enormous achievements of the Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science under the direction of the late Fuat Sezgin, the Liebieghaus is able to display various models and reconstructions of scientific instruments illustrating the fabulous advances in research made during Islam’s Golden Age. These achievements are shown in the rooms of the Liebieghaus, where sculptures from the European Middle Ages are set up in order to evoke a dialogue between the somewhat anti-scientific Christian world and the more pro-scientific Islamic world.

A work by Jeff Koons titled Apollo Kithara represents another premiere, which on the one hand very deliberately takes up specific aspects of the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung’s research into the polychromy of statues of antiquity, while on the other hand also offers a contemporary response to the longing of antiquity and of Islam to breathe life into sculpture through robotic movement. Koons and the research team of the Liebieghaus changed ideas on this last aspect as well.

The Narrative and the Exhibition Graphics Realised by the Atelier Markgraph

Against the background of the matrix described above, the most important elements of the exhibition concept emerge: loans from Frankfurt, Germany, Italy, France, Greece, the United States, and so on, represent the substance of the narrative strand.

But it is the dense interweaving of graphic art and multimedia components, developed by the Atelier Markgraph of Frankfurt, that really connects the isolated strands, clarifies the interdependencies, and sharpens the eye for the theses developed in the exhibition.

1 Bredekamp 1993 and Bredekamp 1982, pp. 507–59.

Bredekamp evades the question of the extent to which the European Renaissance and the European Baroque took into account the writings of Philo of Byzantium and Hero of Alexandria. That enables him to construct an antithesis between static

antique sculpture and animated automata that probably never existed in that form.

2 Bredekamp 2012, p. 104.

3 Flashar 2015.

4 Grabher 2015.

5 Codex Atlanticus fol. 812r (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana).