JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER, MELBOURNE

Joan and Peter Clemenger’s passion for art and generous philanthropy to the arts over many decades is all the more remarkable given that neither came from families with an interest in visiting galleries and collecting. This is something they developed together as a couple, and it has been one of the hallmarks of their extraordinary lifelong partnership. However, rather than focus exclusively on developing their own collection, the Clemengers made the visionary – and at the time, ground-breaking – decision to share their love of art and the enrichment it gave them, through philanthropy, and particularly through their support of the National Gallery of Victoria, a relationship that now extends over 40 years.

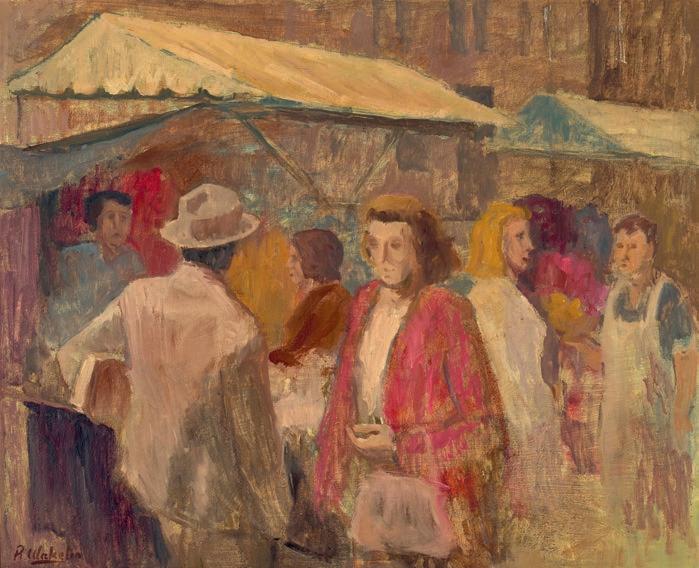

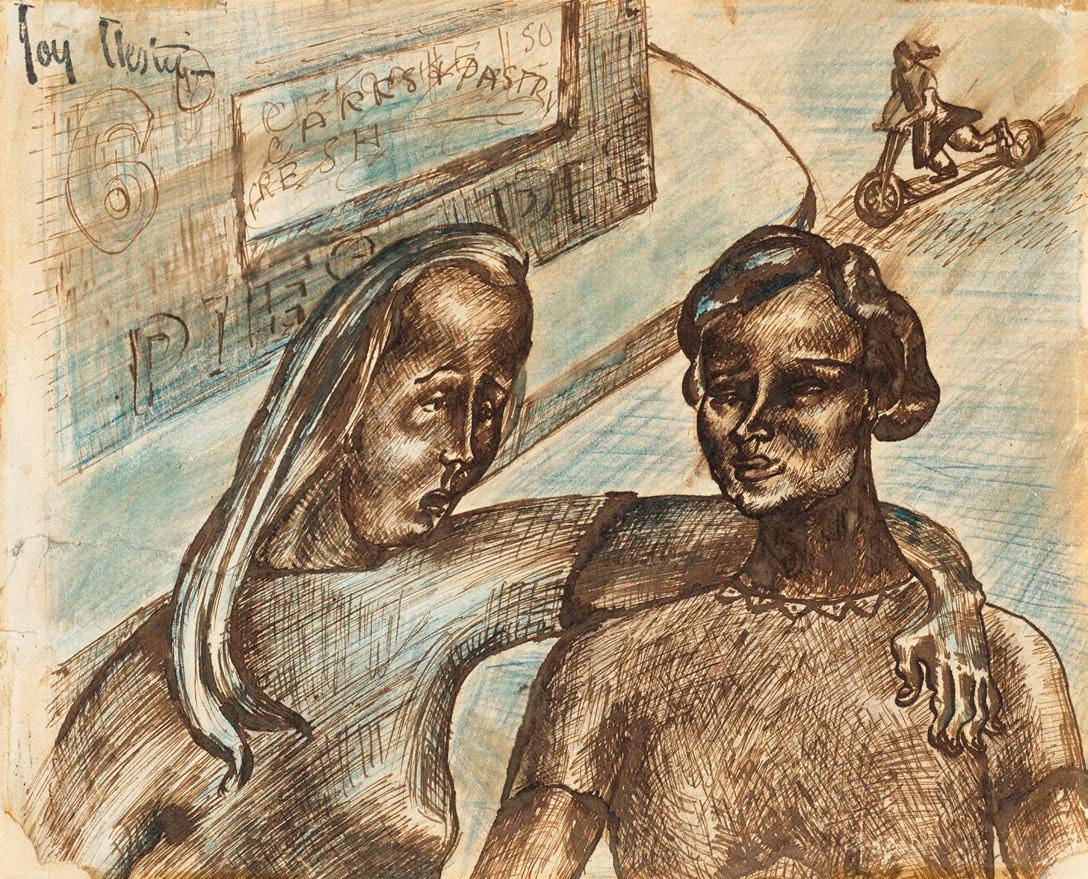

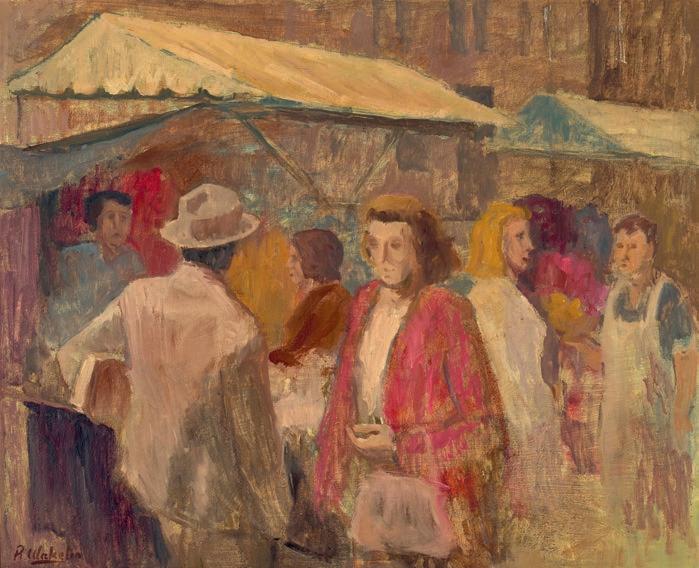

Joan and Peter met when Joan was working in the Collins Street studio of acclaimed Melbourne fashion and advertising photographer Athol Shmith, and the pair married in 1956. Peter had started working in advertising at the age of 16 and joined his father in establishing Clemenger Advertising just two years later. Today, Clemenger BBDO is the largest agency group in Australia. Not long after their marriage, Joan attended a Christie’s art appreciation course, which she loved. Visits to Melbourne’s small clutch of commercial galleries ensued, with Joan coming to know gallerists such as Joseph Brown, Max Hutchinson, Georges Mora, Anne Purves and Sweeney Reed.1 As Peter’s advertising business grew and he was increasingly required to travel overseas for work, their knowledge of art correspondingly expanded to include international modern and contemporary artists and dealers. In a story that has since become family lore, Joan once arrived at the reception of New York’s Chase Manhattan Bank and requested to see the Bank’s art collection. Such was Joan’s courage, determination, and bravura, that no further questions were asked, and she was subsequently taken on a private tour by David Rockefeller (1915 – 2017), the Bank’s chairman and chief executive at the time. As Jason Smith has so aptly described Joan: ‘She had a twinkle in her eye, a ready smile, and a fabulous laugh. But when she spoke, she meant business.’ 2

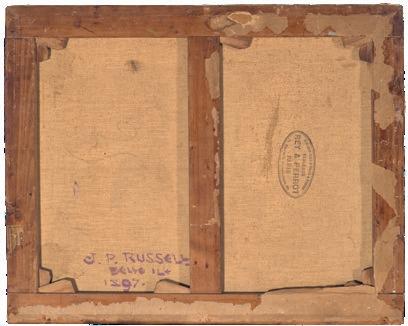

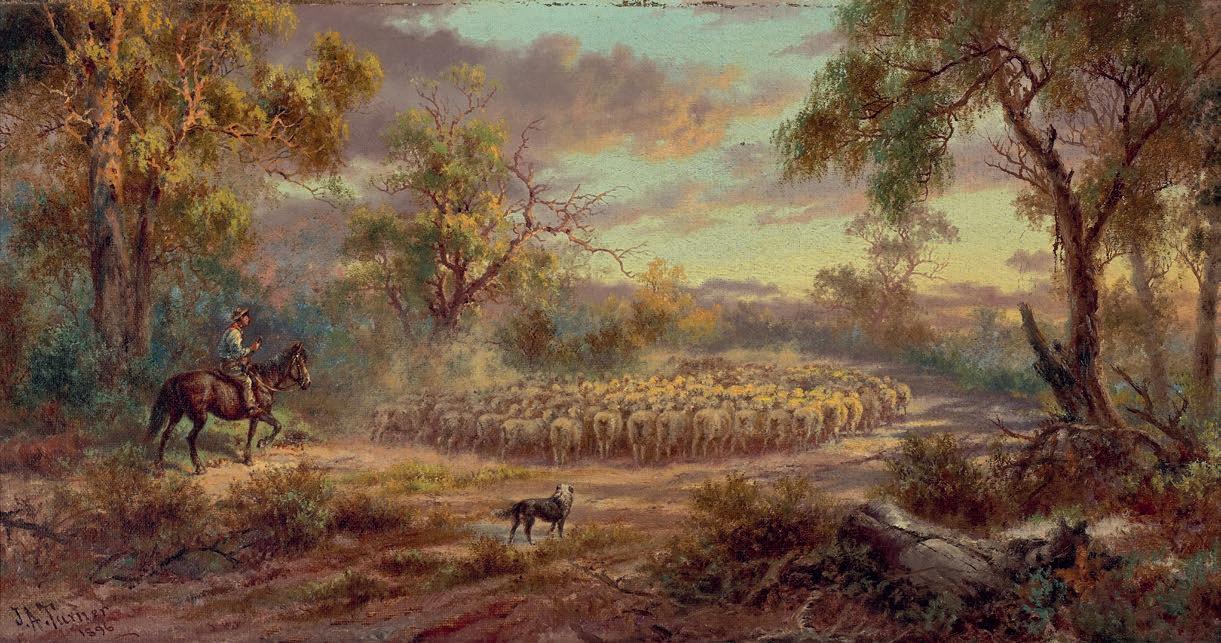

The Clemengers’ art collection started modestly, with an eight by six-inch Ray Crooke painting that was bought from gallerist Barry Stern for £25. This was followed by a group of small paintings by Thomas Gleghorn; a Lawrence Daws for $5; a Fred Williams work on paper, bought from Rudy Komon Gallery for $190, and then a small John Olsen purchased when Peter had ‘had about three sherries… and was feeling fairly relaxed’. Driven by personal response rather than by fashion or art world ‘favourites’, the couple lived with their growing collection and rarely sold works: ‘We’ve not had a plan’, admits Peter, ‘we are just happy with what we’ve got’. 3 Their first significant acquisition was an Arthur Boyd ‘Wimmera’ painting from Melbourne’s Australian Galleries, which was $1,600 – quite a jump from the price of earlier purchases, and quite a stretch for the young couple at the time. As this sale attests, several important works followed including Brett Whiteley’s magnificent South Coast after the Rain, 1984,

13

awarded the prestigious Wynne Prize for landscape painting by the Art Gallery of New South Wales; and Fred Williams’ sublime Landscape with Creek Bed, 1976 – 77, completed the same year as Williams became the first – and only – Australian artist to be honoured with a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

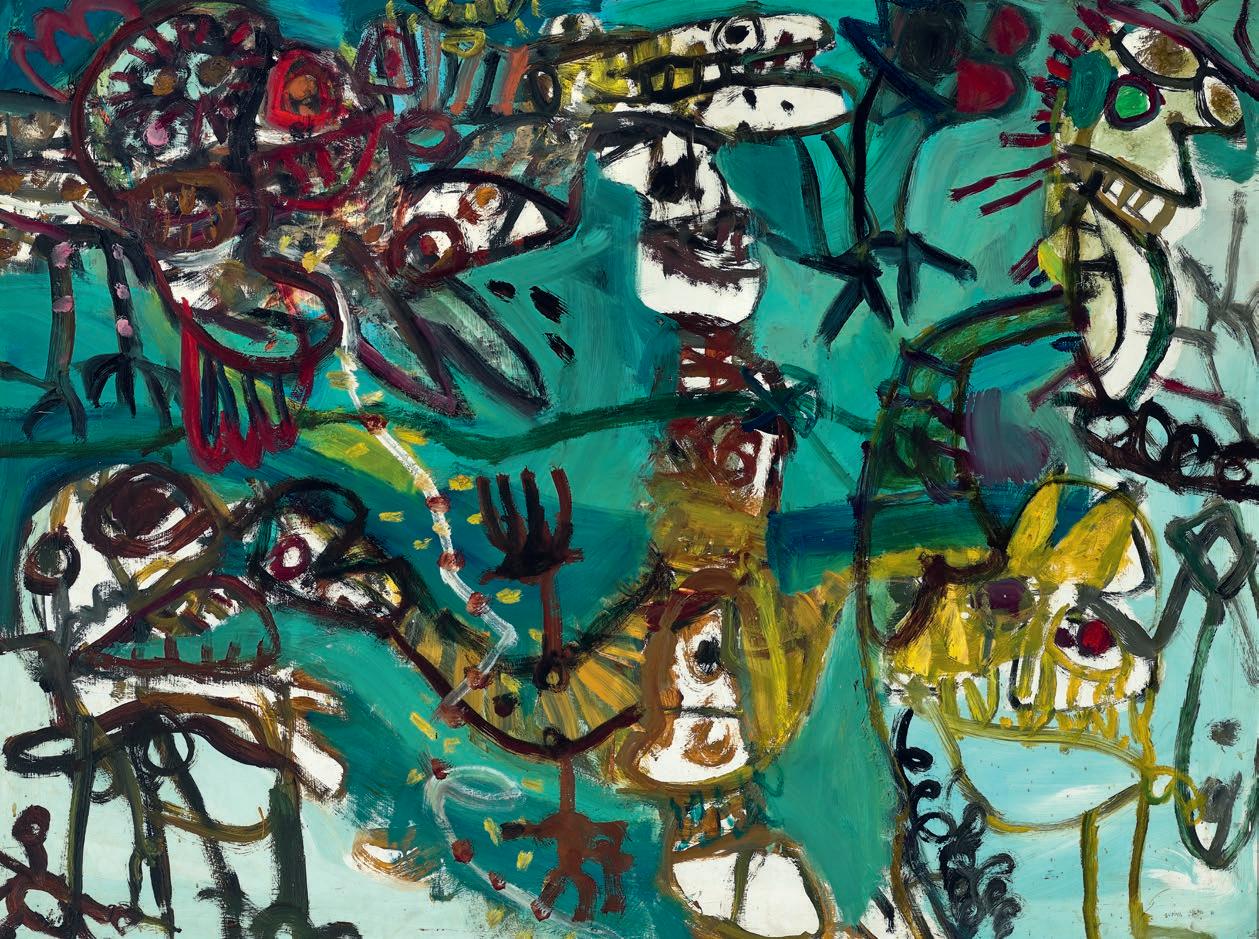

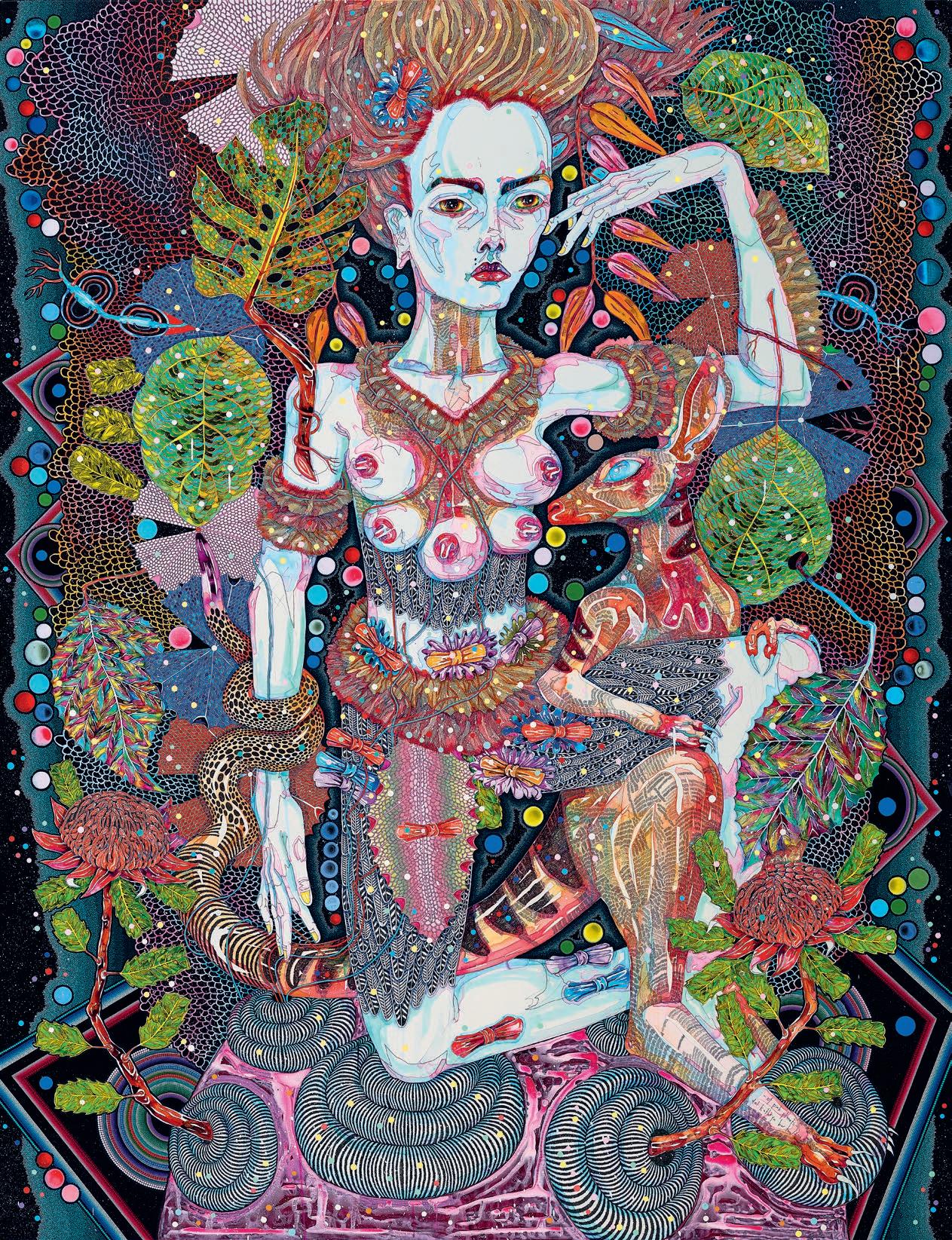

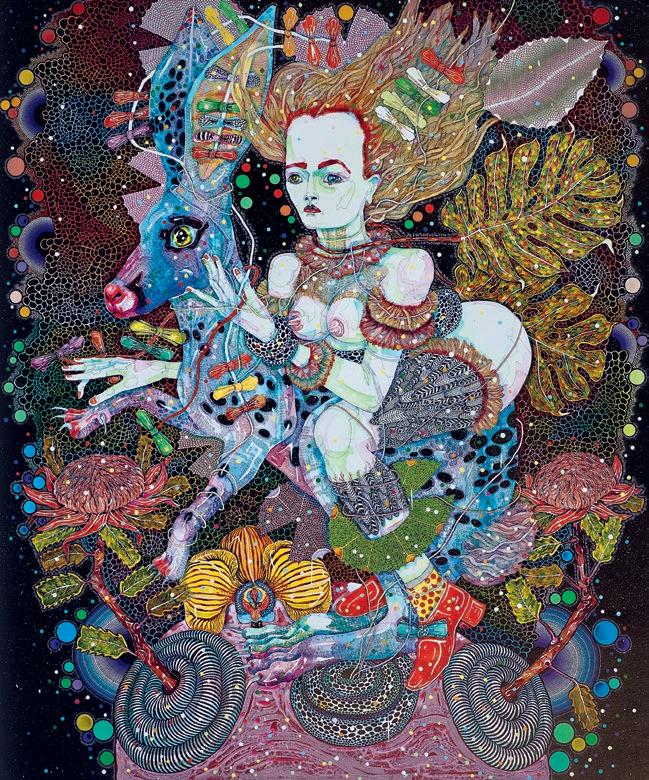

A major donation by the Clemengers to the NGV in 1991 was the impetus for the establishment of what was to become known as the Clemenger Contemporary Art Prize, a series of six triennial exhibitions (running from 1993 to 2009) which celebrated the contribution of Indigenous and non-Indigenous mid-career and senior contemporary Australian artists. Having had the pleasure of working on two iterations of this Prize in 2006 and 2009 as Curator of Contemporary Art, I came to understand and appreciate the Clemengers’ deep commitment to Australian art and artists, their generosity of spirit, and their extensive knowledge. This unique and important series was a collaboration between the Gallery’s curators and Joan and Peter, with the development of each exhibition unfolding over several years. Peter’s keen eye was largely tuned to management of the budget and to the exhibition collateral, signage, and promotion; with Joan acting, in each iteration, as one of Prize’s three judges.

It did not stop there. In 1999, Joan made a commitment to build upon the important legacy of the Gallery’s G H Michell (1976 – 1987) and Margaret Stewart Endowments (1987 – 1997), which supported the acquisition of emerging Australian artists working in all media. Thus, the Joan Clemenger Endowment was born. Over the course of the Endowment’s four-year term, Joan was closely involved in the acquisition process, visiting galleries with the curators, and attending Acquisitions Meetings. The price for works was capped at $5,000 to ensure that the fund was truly benefiting artists at the beginning of their professional careers, and to enable the purchase of a greater number of works. It is telling that many of the artists whose work was acquired through this fund – including David Rosetzky, Ricky Swallow and Louise Weaver, to name but a few, are now some of our most celebrated contemporary artists.

Given the benefits they derived from travel, and from seeing the world’s best museums, Joan and Peter also established the Clemenger Travel Grant – an application-based program that enabled the professional development of the Gallery’s curators, conservators, and other professional staff. I was fortunate to be a recipient of this grant and can vouch for the life- and career-boosting benefits of the five-week trip I was able to undertake, visiting museums and colleagues across the UK and North America. The grant has now been running for close to 20 years.

14

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

After the end of the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award, Joan and Peter’s support of acquisitions at the NGV broadened to include international contemporary art, but equally, they have also been quietly involved in the purchase of works across other collecting areas for decades. After Joan’s death in early 2022, Peter has continued the couple’s commitment to the NGV, ensuring that Joan’s legacy as a benefactor, art lover, and friend to artists continues through his involvement.

Yet the Clemengers’ benefaction is by no means exclusive, and alongside their incredible support of the NGV they fostered long term relationships with a range of arts organisations. Peter was a patron of the Melbourne International Arts Festival, the pair are Lifetime Patrons of the Melbourne Theatre Company, and through the Joan and Peter Clemenger Trust (established in 2001) they support the Australian Ballet to bring international artists and companies to Australia to tour. Searching for a major tourism and reinvigoration project for Melbourne in the early 1990s, Peter established (and funded) the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival and ran the organisation for nine years. It has since become one of the world’s top food and wine events and celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. Joan is a Fellow of Heide Museum of Modern Art and was central to the fundraising efforts that enabled the Museum to develop the 2012 exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Late Works and was also a supporter of a host of organisations ranging from Orchestra Victoria to Big Brother Big Sister and Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria. The Clemenger Trust has also funded medical research through its support of, amongst other organisations, the Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria, the Centre for Eye Research Australia, the Peter McCallum Cancer Foundation and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and has helped address the needs of vulnerable children, young people and families through its substantial support of Anglicare. 4

In 2015 Joan and Peter Clemenger scored a rare ‘double’ in the Australia Day Honours, each becoming Officers of the Order (AO) for their support of the visual and performing arts and for their philanthropic work. Peter’s response to this very public recognition was characteristically low-key: ‘I got a letter telling me about the award and thought that’s nice…Then I opened another letter and found Joan had the same. That was wonderful.’ 5

The author is grateful to Veronica Angelatos for the notes she took during her interview with Peter Clemenger at his Melbourne home on 26 May 2022, which have informed this piece.

1.

Shmith’s studio, in 1967. Max Hutchinson (1925 – 1999) was the founding director of Gallery A; Georges Mora (1913 – 1992) was the director of Tolarno Galleries; Anne Purves was the director, with husband Tam, of Australian Galleries, and Sweeney Reed (1945 – 1979) was the Director of Strines Gallery, and later, Sweeney Reed Gallery.

2. Smith J., speech notes for Joan Clemenger AO, Memorial Service, 5 April 2022. Jason Smith, also a Curator of Contemporary Art at the NGV from 1997 to 2007, worked on the 1999, 2003 and 2006 iterations of the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award.

3. Childs, K., ‘Portrait of a Patron’, Flight Deck , May 1993, p. 21 in ‘EXHIBITION: JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER TRIENNIAL EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN ART 1996 PART 1: APR 1993 – DEC 1994’, NGV RMU File G1111, accessed 29 June 2022

4. ‘Advertising Legend Peter Clemenger and Wife Joan Both Awarded AO in Australia Day Honours’, 26 January 2015, https://campaignbrief.com/ad-legendpeter-clemenger-and/?utm_source=pocket_mylist , accessed 23 July 2022

5. Money L., ‘Australia Day Honours: Ad Legend Clemenger and Wife Score The “Double”’, The Sydney Morning Herald , 23 January 2015, https://www.smh. com.au/national/australia-day-honours-ad-legend-clemenger-and-wife-score-the-double-20150123-12wu6a.htm l, accessed 23 July 2022

KELLY GELLATLY

15

Joseph Brown (1918 – 2009) opened Joseph Brown Gallery at 5 Collins Street, close to Athol

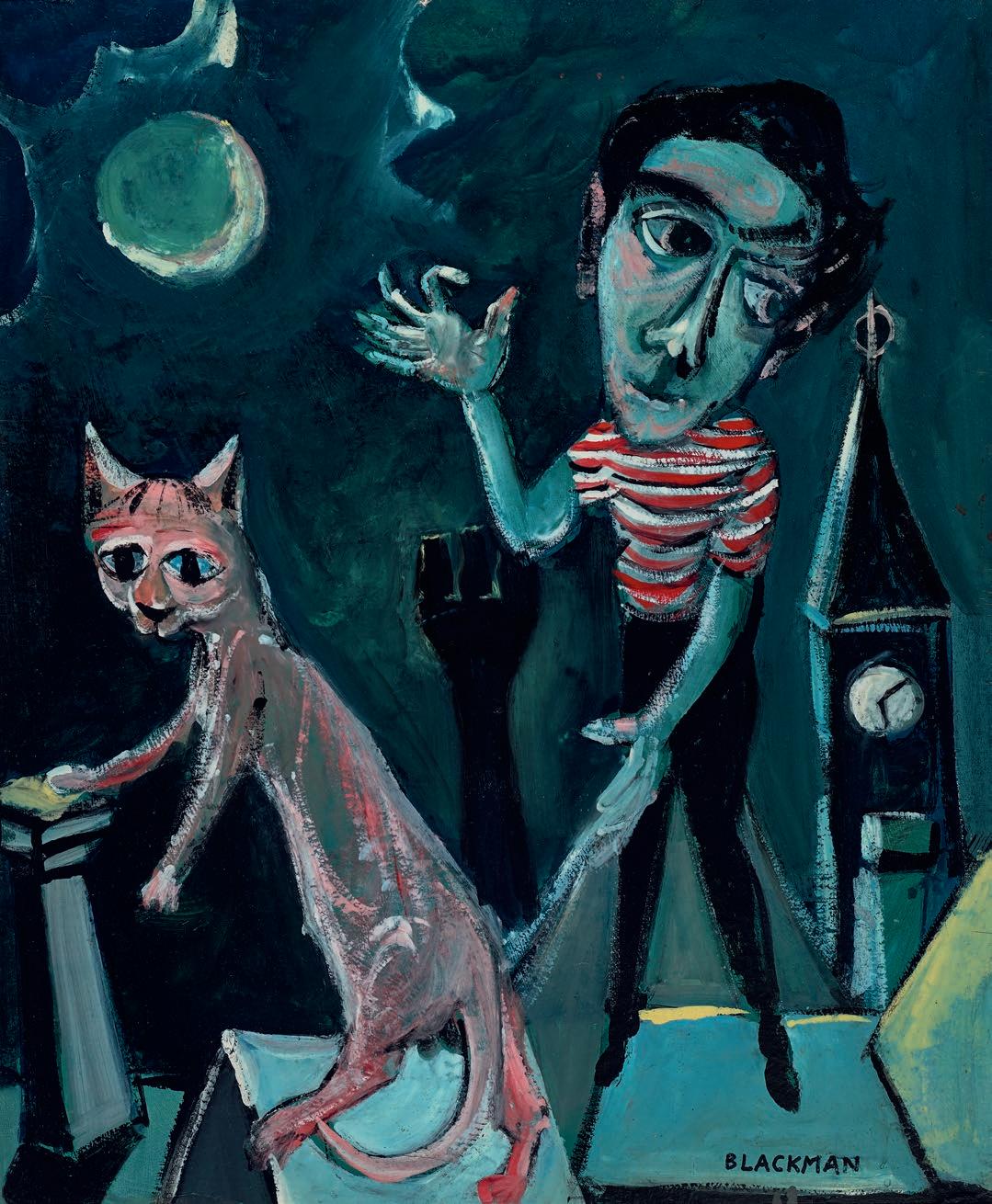

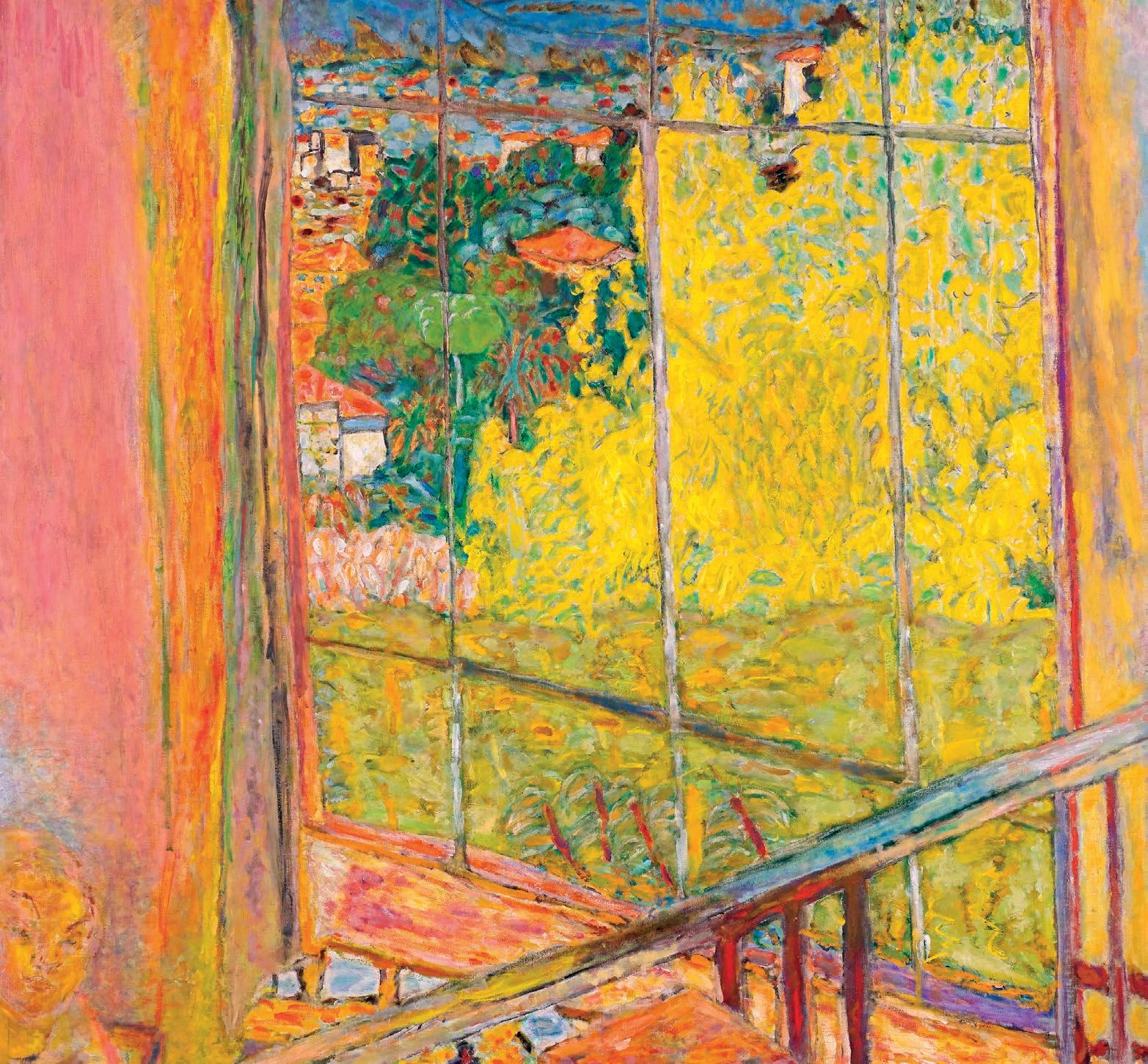

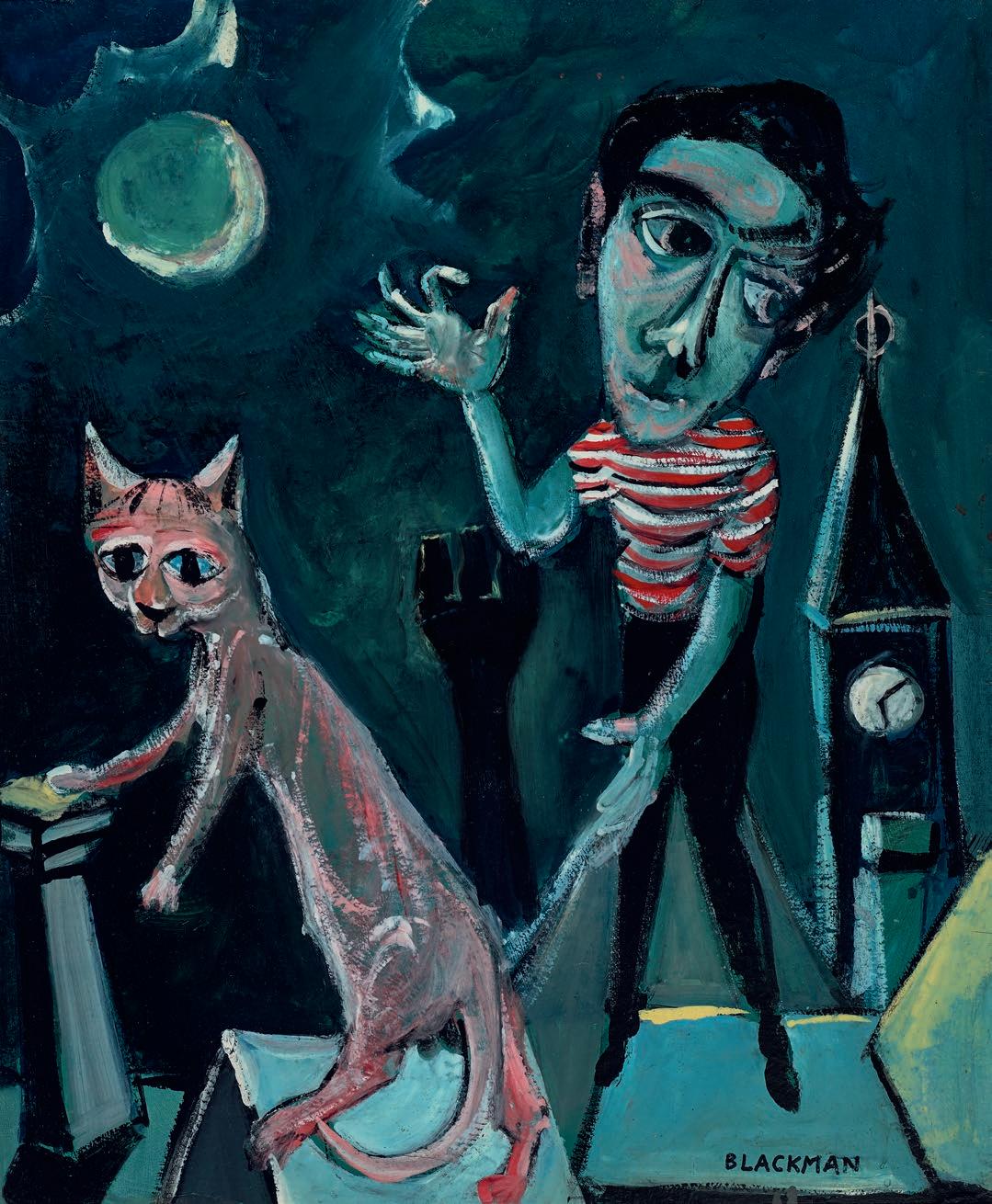

1 BRETT WHITELEY (1939 – 1992)

SOUTH COAST AFTER THE RAIN, 1984 oil and collage on canvas (with white oil on Perspex surface)

137.0 x 122.0 cm

signed upper left: brett whiteley dated and inscribed with title lower right: ‘the south coast’ June 1984 signed, dated and inscribed with title on artist's handwritten label verso: "THE SOUTH COAST AFTER RAIN" 1984 / 54" x 48"

/ oil + collage on canvas / BRETT WHITELEY / 8 REIBY PLACE / CIRCULAR QUAY

ESTIMATE: $1,500,000 – 2,000,000

PROVENANCE

Robin Gibson Gallery, Sydney

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in March 1985

EXHIBITED

Wynne Prize , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 15 December 1984 – 25 January 1985, cat. 84 [awarded Wynne Prize in 1984]

Brett Whiteley: Art & Life , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 16 September – 19 November 1995, touring exhibition to Darwin, Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne and Hobart, until 17 November 1996, cat. 100 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: Art and Life , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1995, pl. 104 (illus.), p. 232

Hilton, M., and Blundell, G., Whiteley: an unauthorised life , Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1996, p. 188

Hawley, J., ‘Brett Whiteley: The Art of the Warrior ’, Sydney Morning Herald Magazine , Sydney and

The Age, Good Weekend , Melbourne, 17 February 1990, p. 26

Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné , Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, cat. 160.84, vol. 4, p. 272 (illus.), vol. 7, p. 640

RELATED WORKS

Study for ‘The Great Australian Landscape’ , 1989 – 90, oil on canvas, 76.0 x 76.0 cm, private collection, Perth Byron Bay at Sunset , retitled South Coast Geographical, 1990 – 91, oil on canvas, 96.0 x 86.0 cm, private collection

16

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

17

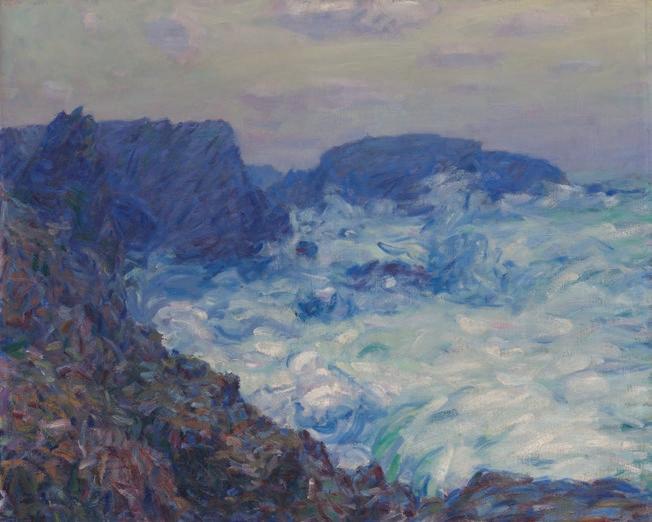

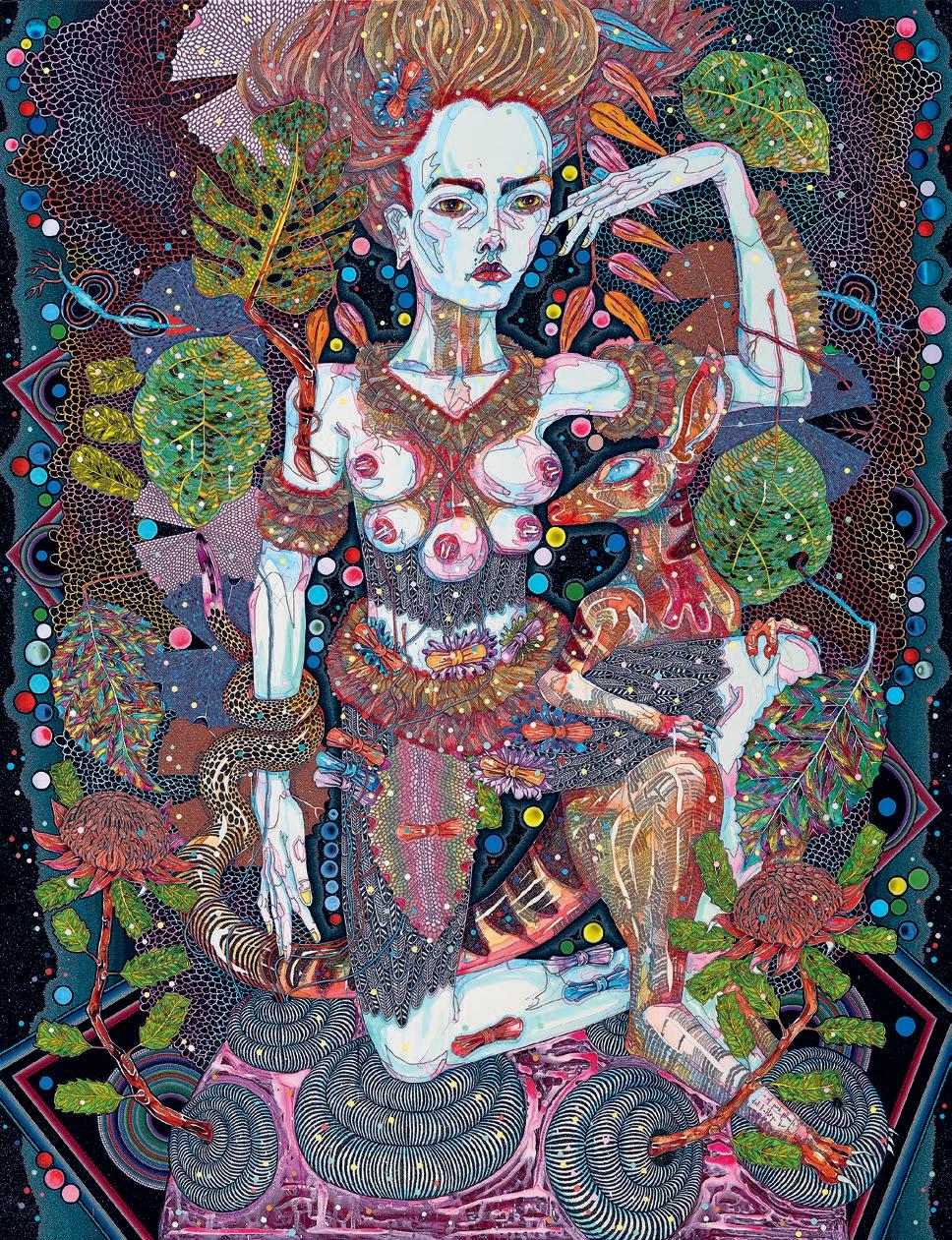

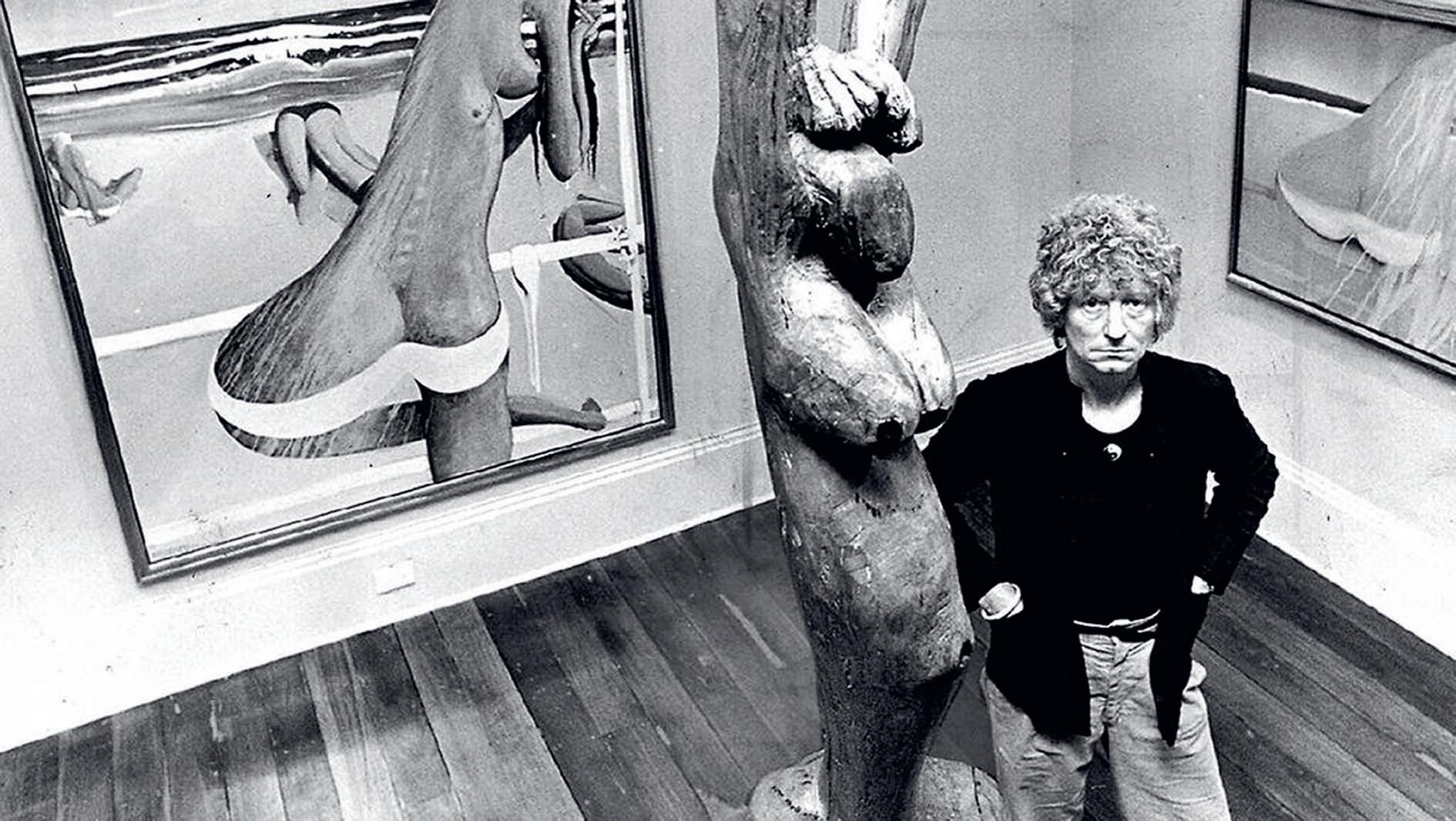

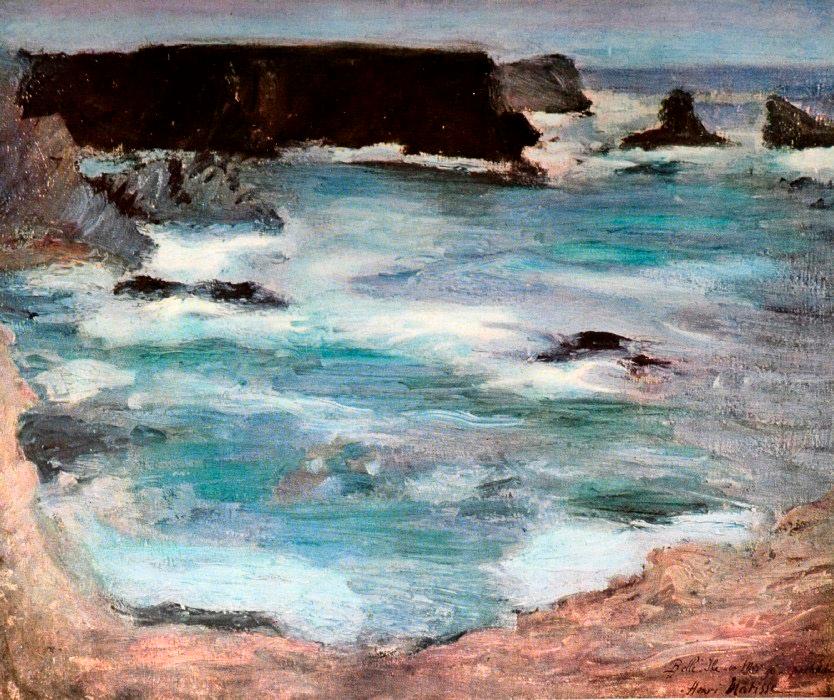

From his auspicious start as the youngest non-British artist ever to have a work acquired by London’s prestigious Tate Gallery1, Brett Whiteley’s artistic trajectory was nothing short of astounding. Hosting his first solo exhibition at Matthiesen Gallery, London in 1962 at the age of 22, the fiery, tousle-haired wunderkind quickly made a name for himself internationally as an urgent, flamboyantly talented artist. After launching himself on New York for a brief period of turbulence, Whiteley subsequently returned, upon the expiration of his American dream, to Sydney in late 1969 where, seduced by the enchanting siren of the city’s harbour, he would embark upon the sumptuous Lavender Bay tableaux universally considered to be the crowning achievement of his career. Significantly, within the decade he had won all three of Australia’s most coveted art awards – both the Archibald Prize for portraiture and Sulman Prize for genre painting in 1976; the Wynne Prize for landscape in 1977; and all three prizes again in 1978 (the only artist ever to be so honoured in the same year).

By the early eighties when the magnificent South Coast after the Rain, 1984 was unveiled at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and awarded the artist’s third Wynne Prize, Whiteley’s fame was at its peak. Yet lurking below such myriad accolades and the ostensible serenity of his art during this period was an increasingly torturous struggle with addiction – a self-destructive legacy borne from a visceral need to ‘test his gift’ that had now become inextricably intertwined with his prodigious creative efforts. Their marriage also flailing, in mid-1984 Brett and Wendy thus departed for England, determined to liberate themselves from the thrall of substance abuse. As the world now knows, after further attempts, Wendy would eventually survive, totally cleansed. For Brett however, it was too late and despite his best efforts over the intervening years, addiction would ultimately consume him, leading to his lonely death in a motel room at Thirroul on the south coast of New South Wales in 1992. 2

Which makes all the more remarkable the lyrical calm of this exquisite painting of a seaside village and shoreline beneath a velvety grey sky, created following Brett’s return to Australia from England in 1984. Bereft of angst or any trace of the psychologically grueling challenges plaguing his life at the time, indeed the work exudes a quietude that perhaps reflects the brief success of his treatment abroad. More

importantly, in a departure from the preceding complex panoramas that focused upon America, Australia and his own richly narcissistic ego, or his more recent suite of images inspired by Van Gogh in 1983 whose crudity raised the ire of critics, in South Coast after the Rain Whiteley showed that he was, underneath all the noise, a superb master of nuance and poise when he so chose.

We may sense, moreover, in this subtle masterpiece Whiteley’s love of Charles Baudelaire, the great French poet and critic, staring at a flat, boundless space of ocean beyond the ruck of humanity and its little, red-roofed houses below. Baudelaire had once recalled a childhood when his parents, hoping to rein in his wildness, sent him on an illconceived sea voyage, instigating the bitter-sweet phrase:

Quand partons-nous pour le bonheur? When shall we set sail for happiness? 3

Indeed, it was as if Whiteley channeled Baudelaire to address his own passionate, angry longing, impelled to seek balm beyond the tangled inlets of Longueville after his mother deserted the family to migrate to England in 1956. This he did, three years later, tracking her across oceans and striking gold abroad with the acclaim of a pop star.

When Brett and Wendy returned to Sydney in 1969 after a decade of phenomenal success, he immersed himself in a state of ecstasy at the sublime expanses of Lavender Bay, where they settled, with paintings of exquisite, Matisse-like scale and mood, that were precursors to South Coast after the Rain . These chimed with the end of Arthur Rimbaud’s poem Le Bateau Ivre, a poignant reminder – notwithstanding the poet’s theory of dérèglement and Baudelaire’s exhortation of drunkenness

– that innocence might have been the ultimate resistance to selfimmolation if only it was possible to bottle it:

If there is one water in Europe I want, it is the Black cold pool where into the scented twilight

A child squatting full of sadness launches

A boat as fragile as a butterfly in May 4

18

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

19

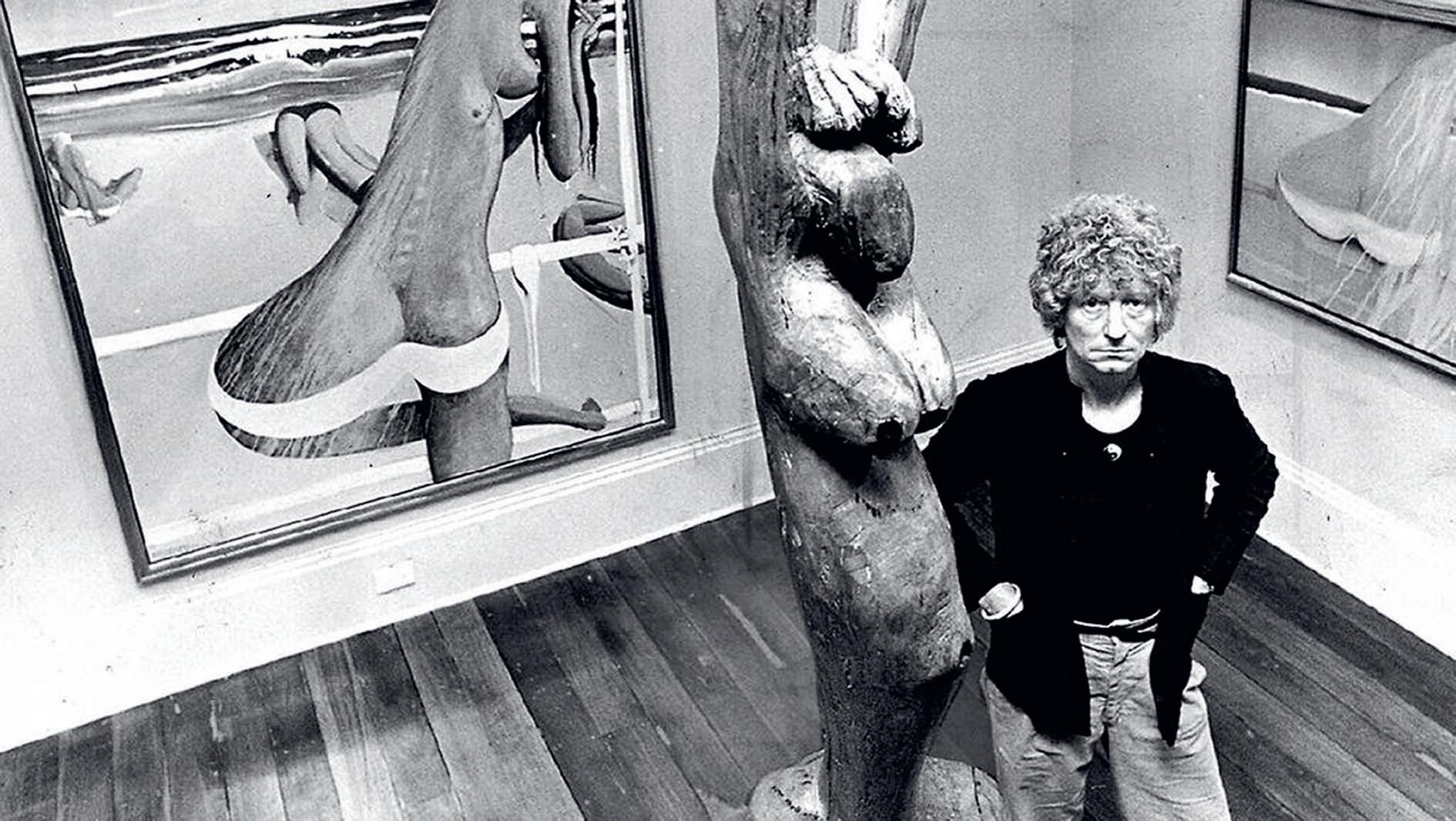

Brett Whiteley poses in front of his painting titled ‘The South Coast After the Rain’ which won the 1984 Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) in Sydney, New South Wales, 14 December 1984 photographer: Bob Finlayson / Newspix

To be sure however, those wonderfully eloquent Lavender Bay images also became mirrors of danger masked by sheer visual poetry, aided and abetted by a state of addiction, albeit cleverly bolstered by sections of shoreline, high horizons, window frames and balconies marshalling astute deployments of arabesque. And they counterpointed perfectly the sea and beach motifs Brett happily found along the coasts of New South Wales.

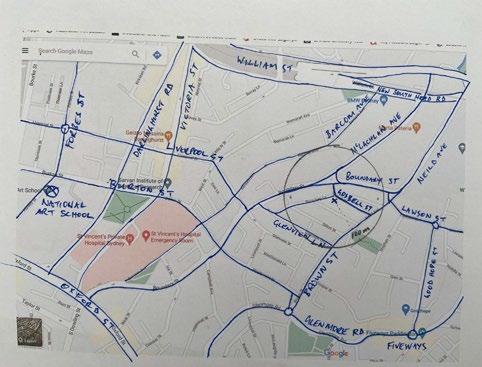

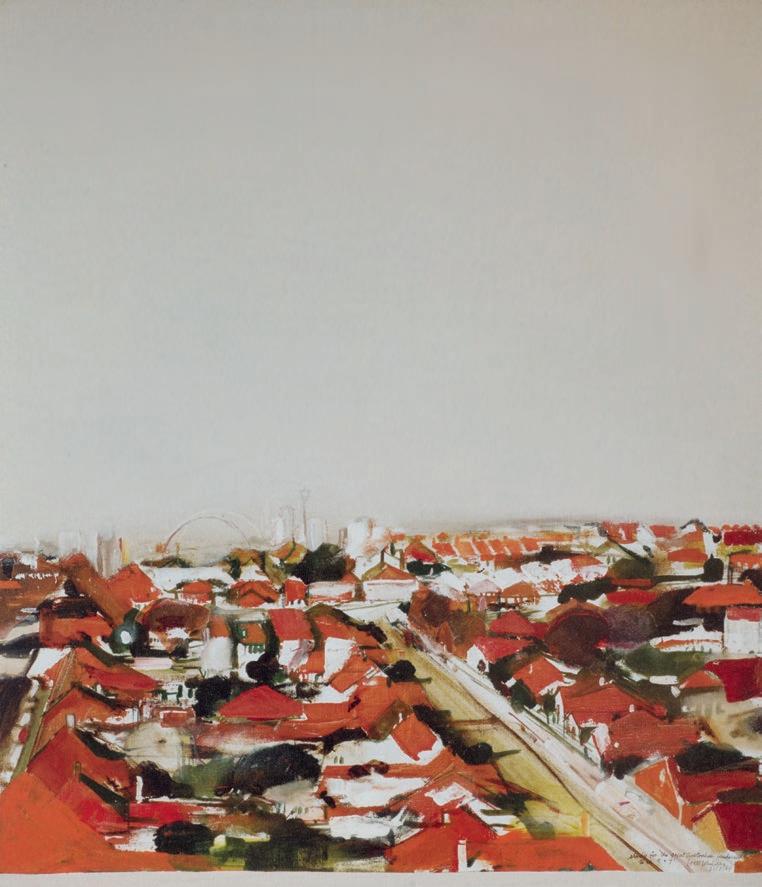

Whiteley’s geographical reach was astonishing, well beyond Sydney. Which raises the question of exactly where South Coast after the Rain was inspired and how it fitted within the artist’s ultimate intention to accumulate a vast collective image of Australia across the entire continent. It has been suggested that this particular composition was probably seen by the artist from the balcony of an apartment block on Kennedy’s Hill near Austinmer, looking across Thirroul towards Sandon Point headland with Wollongong lighthouse in the distance – the region

where for many years he had escaped from city angsts, relaxed, swam, and detoxed in solitude. Very close, in other words, to where his life was to end. 5

In her definitive catalogue raisonné, Kathie Sutherland avoids the problematic challenge of identifying exact locations with Whiteley’s landscapes, placing this painting within a broader context whereby topography was often turned on its head by the artist’s imaginative interventions. In other words, the motifs were nearly always departure points, like music being separated from the libretto:

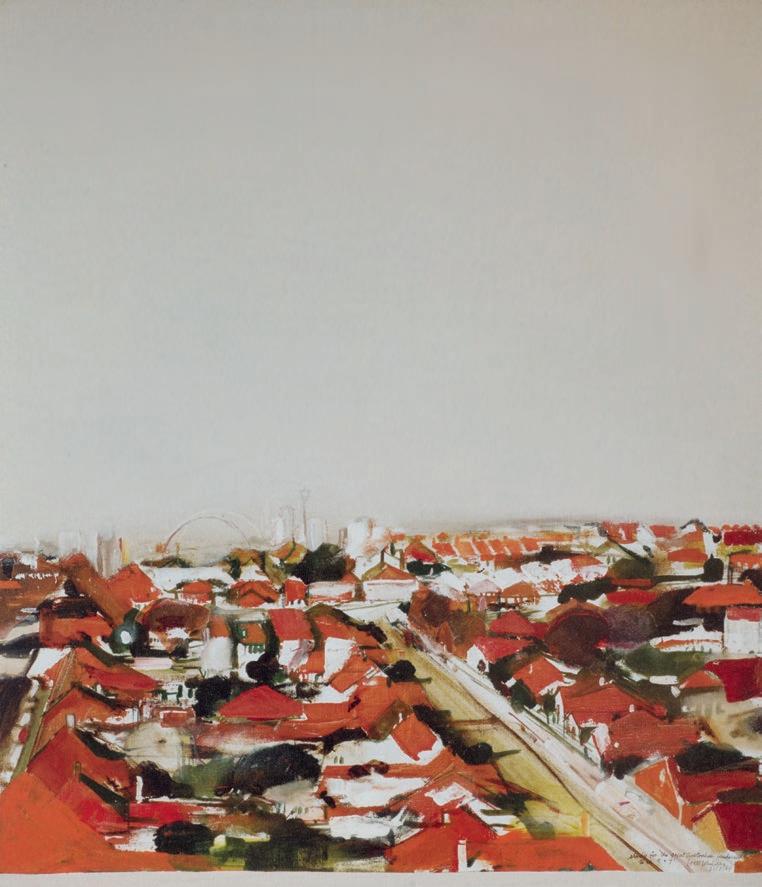

‘…Suburbia is another important component in the development of the theme on The Great Australian Landscape. The Suburbs, a large oil and a key work included in the 1970 exhibition [Bonython Art Gallery, Sydney, thence Australian Galleries, Melbourne], was repainted in 1982… It depicts an ordinary suburban house – a red tiled roof set behind a real

20

Brett Whiteley Red Roofs with Palm Trees , 1983 oil on canvas on hardboard 40.0 x 54.0 cm

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

Whiteley Estate © Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency

paling fence – looking out to a landscape dotted with more red-roofed bungalows and suburban vegetation. This idea continues to evolve over several decades, with variations on a theme that include Red roofs with Palm Trees (1983)… South Coast after the Rain (1984)… and Study for The Great Australian Landscape (c.1989)… Common to each painting is a palette dominated by reds, oranges and greens that describes the profile of the typical sprawling Australian urban landscape.’ 6

Whiteley himself spoke succinctly of his Great Australian Landscape project during the last two years of his life, expanding the concept way beyond the original idea of ten panels, as he declared in an interview with Andrew Olle in 1991: ‘…50 panels from Bondi to Uluru… through the blue suburbs, the red roofs, the city, the Blue Mountains, the bush, the outback and right through the red heart… 50 panels… to refer to the full political, historical and cultural levels of Australia.’ 7 Furthermore, Ashleigh Wilson’s biography of 2016 records a comment by Whiteley

about the overwhelming energy required to bring this project to fruition, and a fatalistic statement that if he was given only four years left to live, he would have to drop everything to get it done. 8

There had been a creative high in 1989, travelling to Paris with his girlfriend Janice Spencer, but when they returned to Sydney Brett was faced with the trauma of settling divorce with Wendy. Soon after, his relationship with Spencer began to disintegrate too and he felt his life ebbing towards a loneliness underscored by inability to stop using heroin. The end was nigh: ‘…the self-destructive side of me that wants to die… I have arrived at a point in my life where unless I revise, unless I mature, unless I shape up, unless I look at my character defects, unless I get a sobriety, I will spin out…’ 9

With its characteristic verve, sensuous colour and irreverent wit, South Coast after the Rain offers a consummate example of the singular vision

21

Brett Whiteley Study for ‘The Great Australian Landscape’ , 1984 oil and collage on canvas 105.5 x 91.0 cm Whiteley Estate © Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency

for which Whiteley remains so highly acclaimed. In the centre of the sky, floating on perspex above the canvas, are three small farewell streaks left by the retreating rain – a witty gesture by the artist signifying subtle denial of a binding rule of bonne peinture. He breaks the rule, but with Maurice Denis standing at his shoulder, he challenges us to realise that beneath those floating marks there is not an illusion of deep space but a painting with the full integrity of flatness.

The real music of this painting, however, remains the swathe of red and orange rooftops at the base of the composition, reflected in small flecks on the distant headlands. It is not easy to know how extensive such roofs were in the 1980s since Thirroul, once a thriving mining town with a local brick kiln, was soon to undergo dramatic change with demolition of miners’ cottages and tiled roofs as developers moved in to accommodate a new era of tourists and holiday apartments.10

What we do know for sure though is that Whiteley had already fallen in love with red roofs a decade earlier when he and Garry Shead absorbed themselves to obsession with D. H. Lawrence who had stayed several

weeks in Thirroul, where he wrote his iconic novel Kangaroo in 1922. In that book, Lawrence refers to the red roofs of Sydney Harbour appearing like a ‘burgeoning infection’.11 Notably, several of Whiteley’s paintings over his final decades bear witness to this obsession, including two predecessors to South Coast after the Rain : Sketch for the Red and Green of the Suburbs, 1979 which resembles a construct by Nicolas de Stael, and the highly minimalist Bondi , 1978 with its flat patches of red architectural shapes juxtaposed against an unmodulated field of celadon grey.

In the end however, aesthetics inevitably took precedence over topographical truth in his art, and as such, specifics about exactly where, when or how Whiteley’s genius found its expression no longer greatly matter. For with every brushed and ragging gesture he made, painting was never merely an act of description. Rather, it was the evocation of a dream, sometimes to travel elsewhere, through this, one of his most gently poetic elisions of land, sea and sky – a quiet masterpiece for the ages.

22

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

D.H. Lawrence (left) and Frieda Lawrence (third from left) with three British migrants they had met on the voyage out , (from left) Laura Forrester, Mrs Marchbanks and Mr Marchbanks, at “Wyewurk” in Thirroul, New South Wales , 1922 photographer: A.D. Forrester

Brett Whiteley in his studio, 1985 photographer unknown

Courtesy Mosman Daily, Sydney

1. Whiteley’s Untitled Red Painting , 1960 was purchased by the Tate Gallery from the groundbreaking exhibition, ‘Recent Australian Painting’, held at Whitechapel Gallery, London from June – July 1961. Whiteley was only twenty-one years old at the time of painting the work and significantly, the Tate record still stands today.

2. Details related to Whiteley’s entire life and career are comprehensively covered in Ashleigh Wilson’s biography, Brett Whiteley: Art Life and the Other Thing , Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2016. For this particular context see pp. 351 – 416

3. Baudelaire, C., Intimate Journals , Methuen, London, 1949, translated from the French by Christopher Isherwood, with an introduction by W. H. Auden. Statement in Squibs XI, p. 8

4. Baudelaire, C., Le Bateau Ivre (The Drunken Boat), translated from the French by Oliver Bernard in Collected Poems of Arthur Rimbaud , Anvil Press, London, 1962, p. 218

5. Organ, M., Brett Whiteley and Thirroul…Life and Death , 5 September 2019 , http:// thirroulbrettwhiteley.blogspot.com/, accessed June 2023. This useful blog contains exhaustive detail about Whiteley’s relationship to Thirroul from the early 1970s, including circumstances leading to the artist’s death on 11 June 1992.

6. Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné , Schwartz City, Melbourne, 2020, volume 7, pp. 41, 265

7. Whiteley in conversation with Andrew Olle in 1991, cited ibid., pp. 39, 43

8. Wilson, op. cit., p. 385

9. Whiteley cited ibid., p. 361

10. Organ, op. cit.

11. ibid.

BARRY PEARCE FUni SA

EMERITUS CURATOR OF AUSTRALIAN ART ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES

23

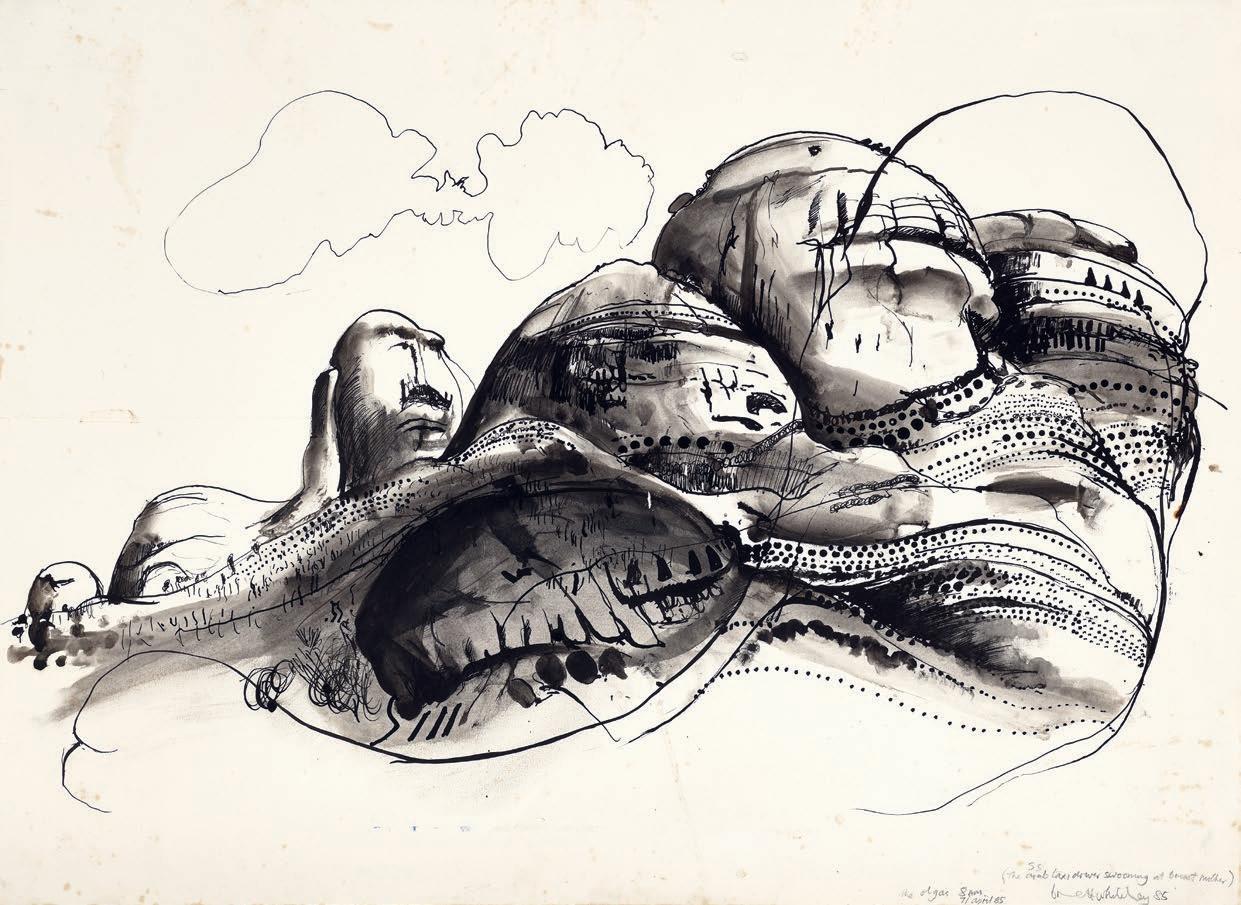

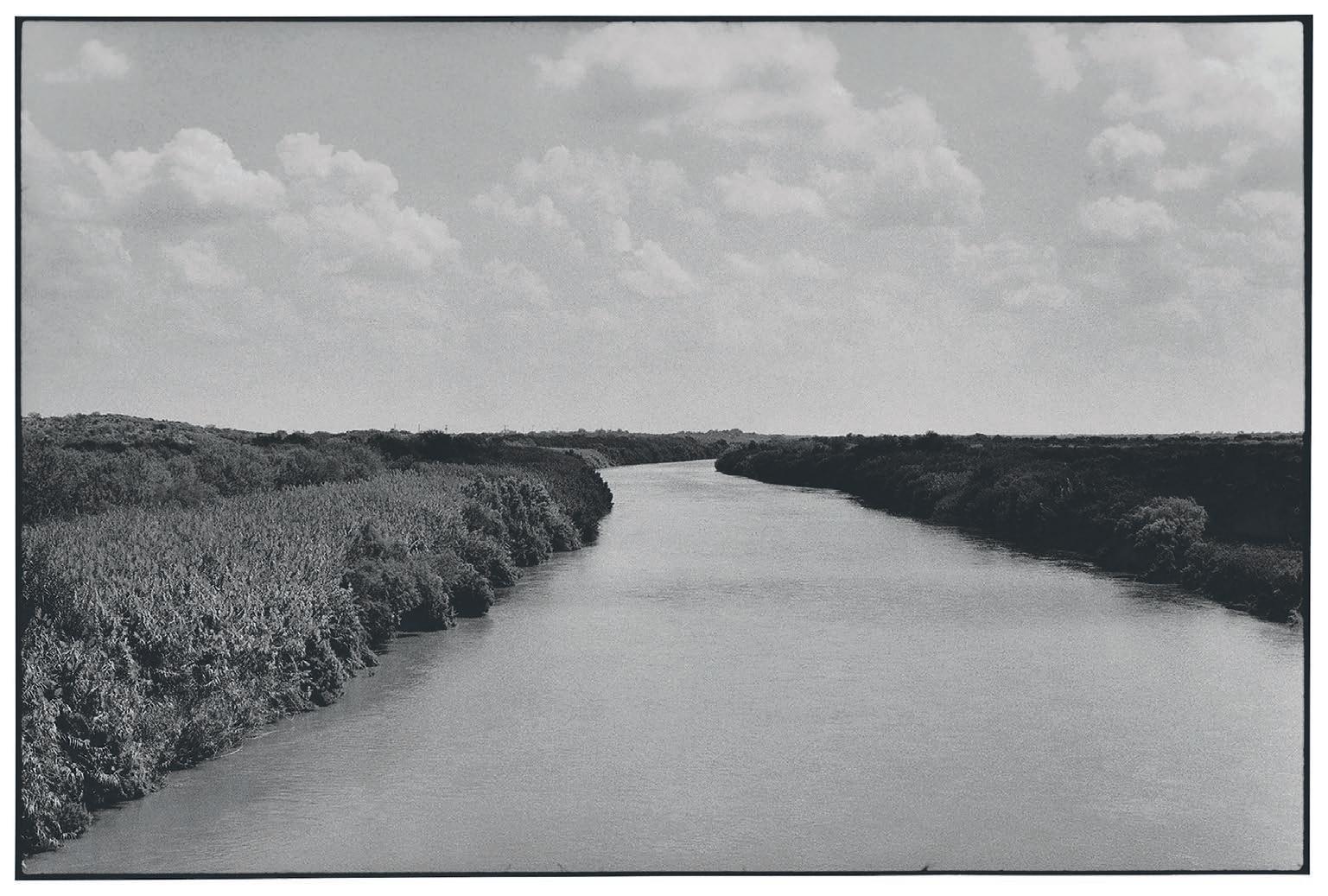

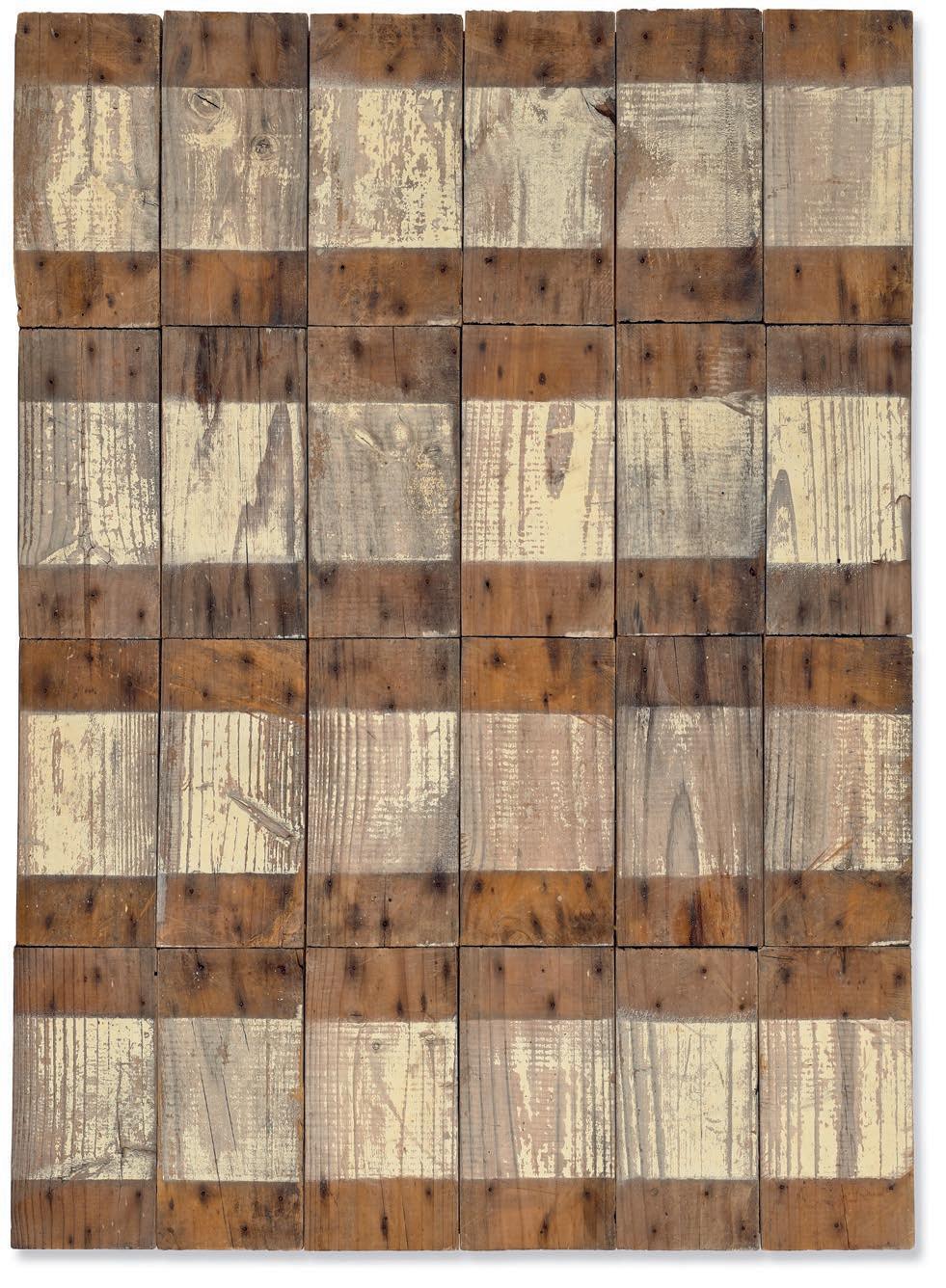

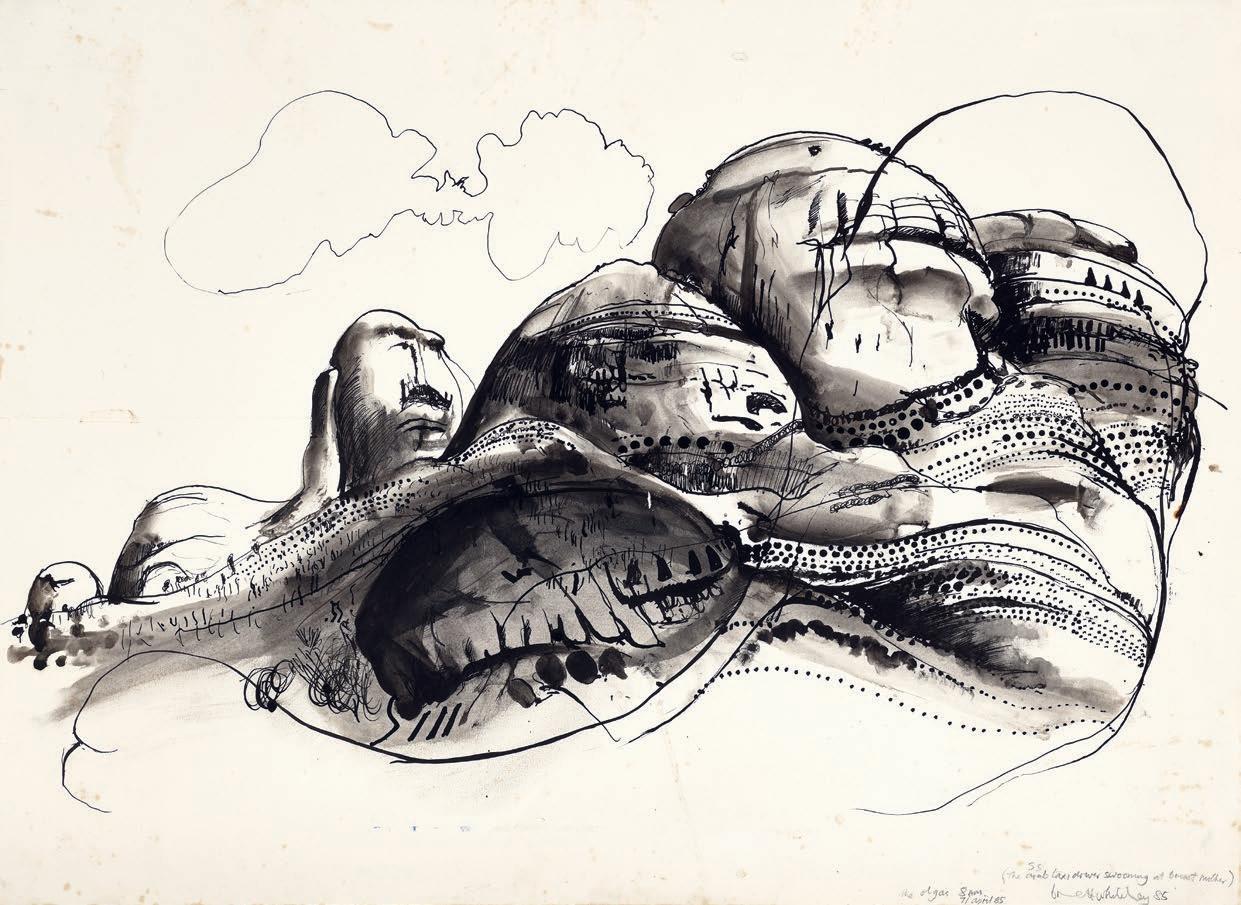

2 FRED WILLIAMS

(1927 – 1982)

LANDSCAPE WITH CREEK BED, 1976 – 77 oil on canvas 153.0 x 137.5 cm

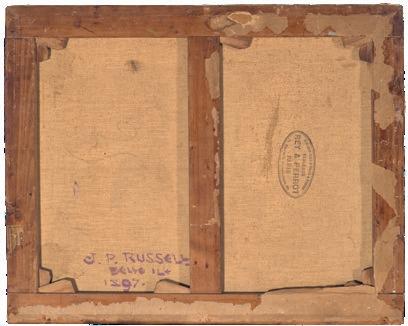

signed upper right: Fred Williams. bears inscription on label attached to stretcher bar verso: TWO PARTS / 1. / FRED WILLIAMS / "LANDSCAPE WITH CREEK BED"

ESTIMATE: $800,000 – 1,200,000

PROVENANCE

Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in April 1978

EXHIBITED

Fred Williams , Undercroft Gallery, University of Western Australia, Perth, 25 February – 12 March 1978; Contemporary Art Society Gallery, Adelaide, 15 March – 8 April 1978 and Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney, 29 April – 7 May 1978, cat. 10

RELATED WORK

Landscape with Creek Bed , 1976, oil on canvas, 153.0 x 137.5 cm, in the Janet Holmes à Court Collection, illus. in Hart, D., Fred Williams: Infinite Horizons , National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2011, p. 146

We are grateful to Lyn Williams for her assistance with this catalogue entry.

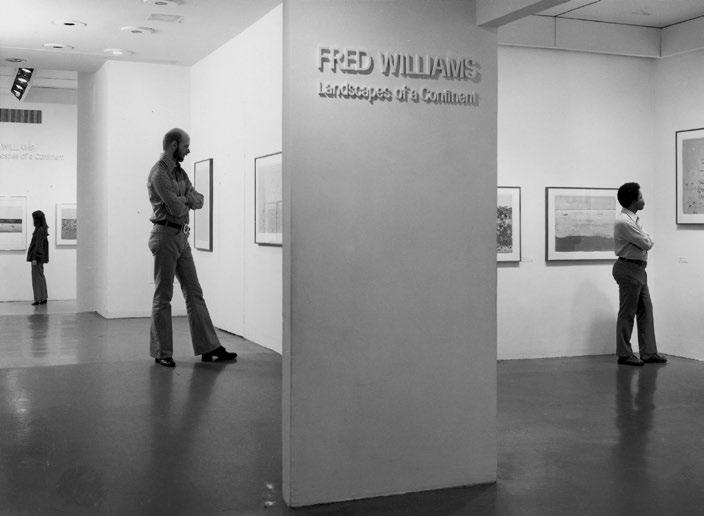

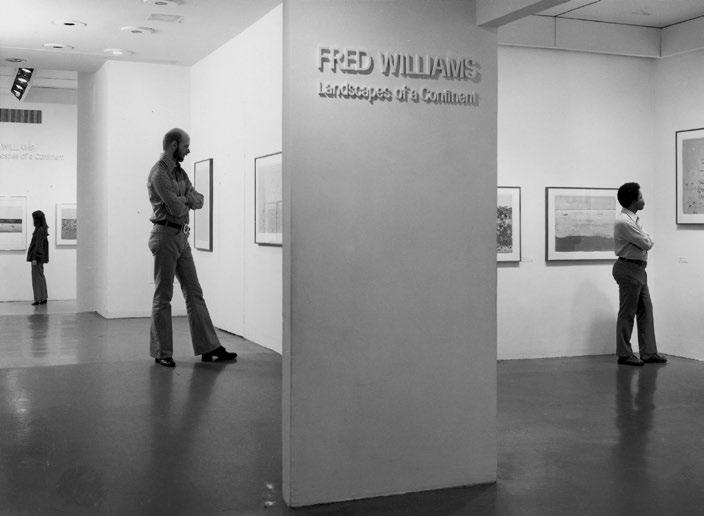

Visitors at the exhibition, “ Fred Williams: Landscapes of a Continent ”, 10 March – 8 May, 1977, Museum of Modern Art, New York

photographer: Kate Keller The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

24

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

25

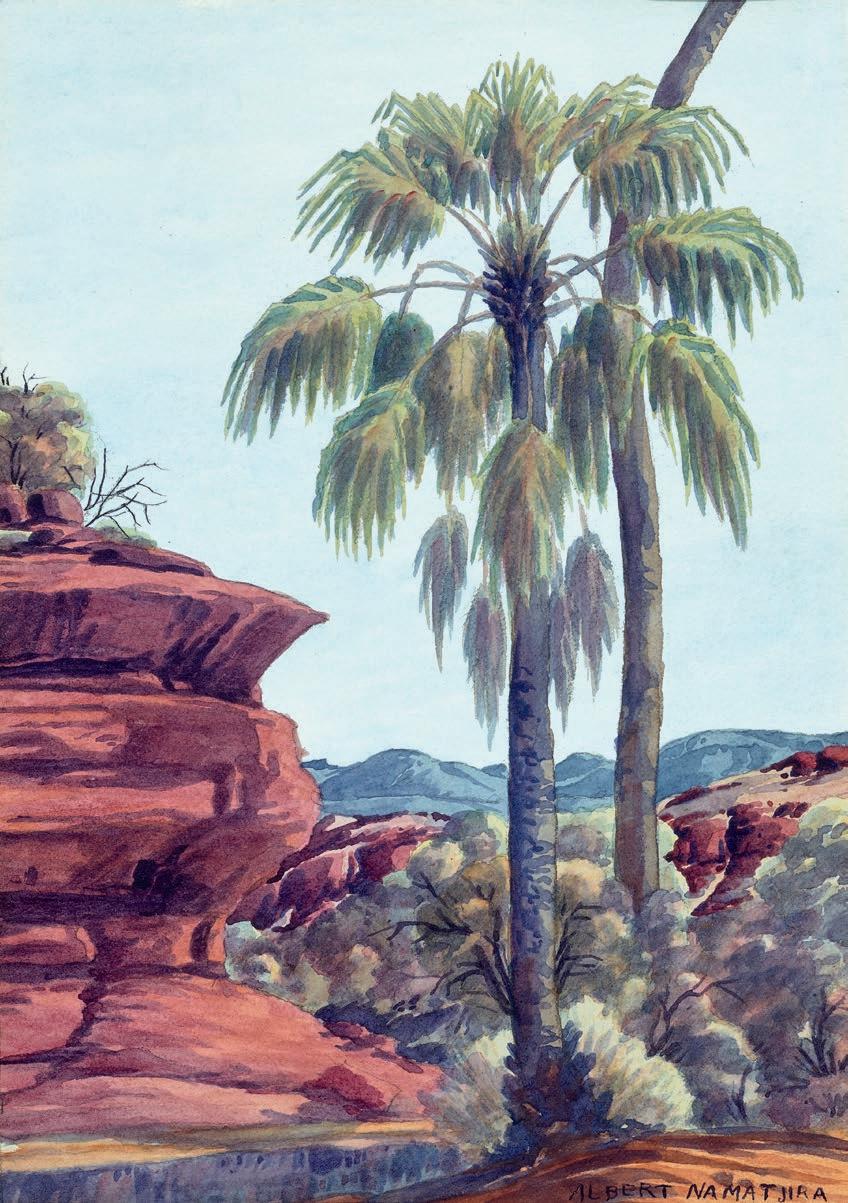

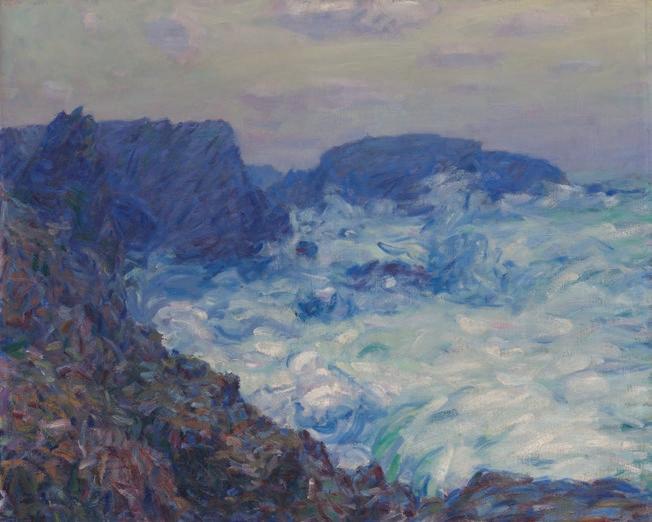

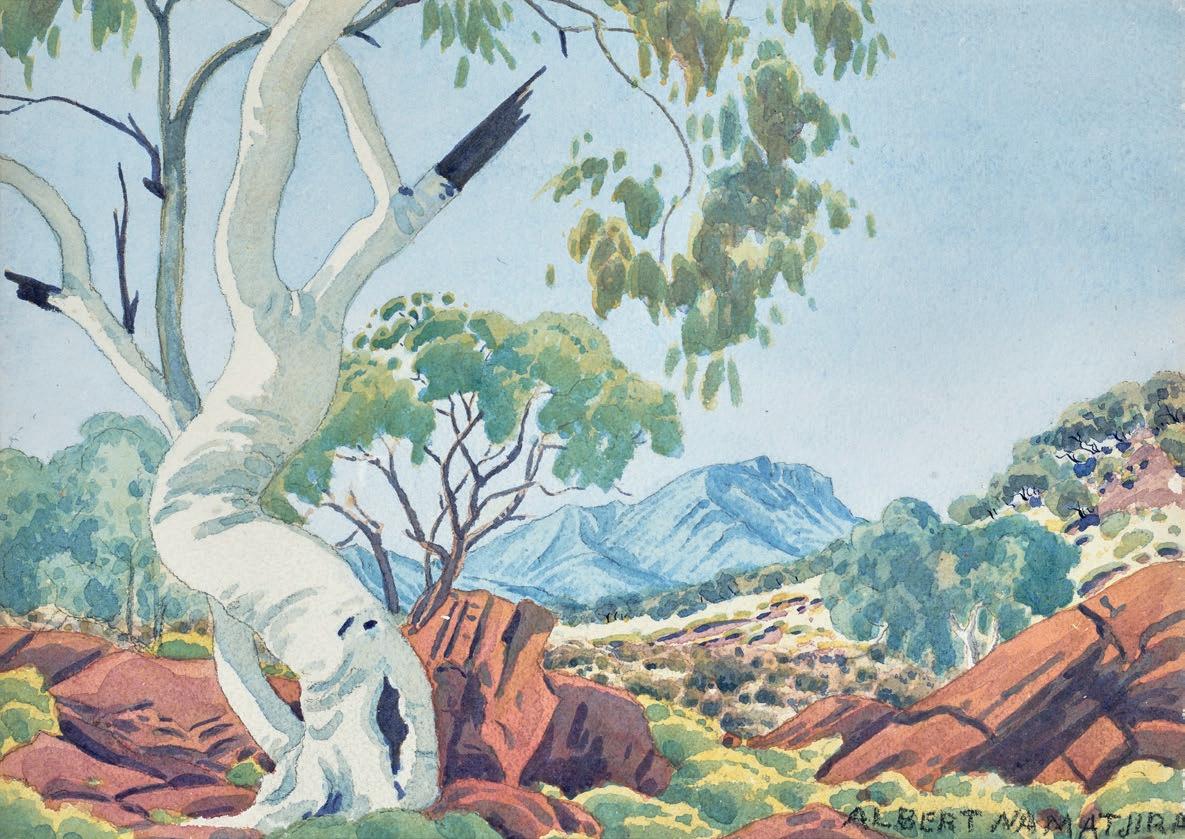

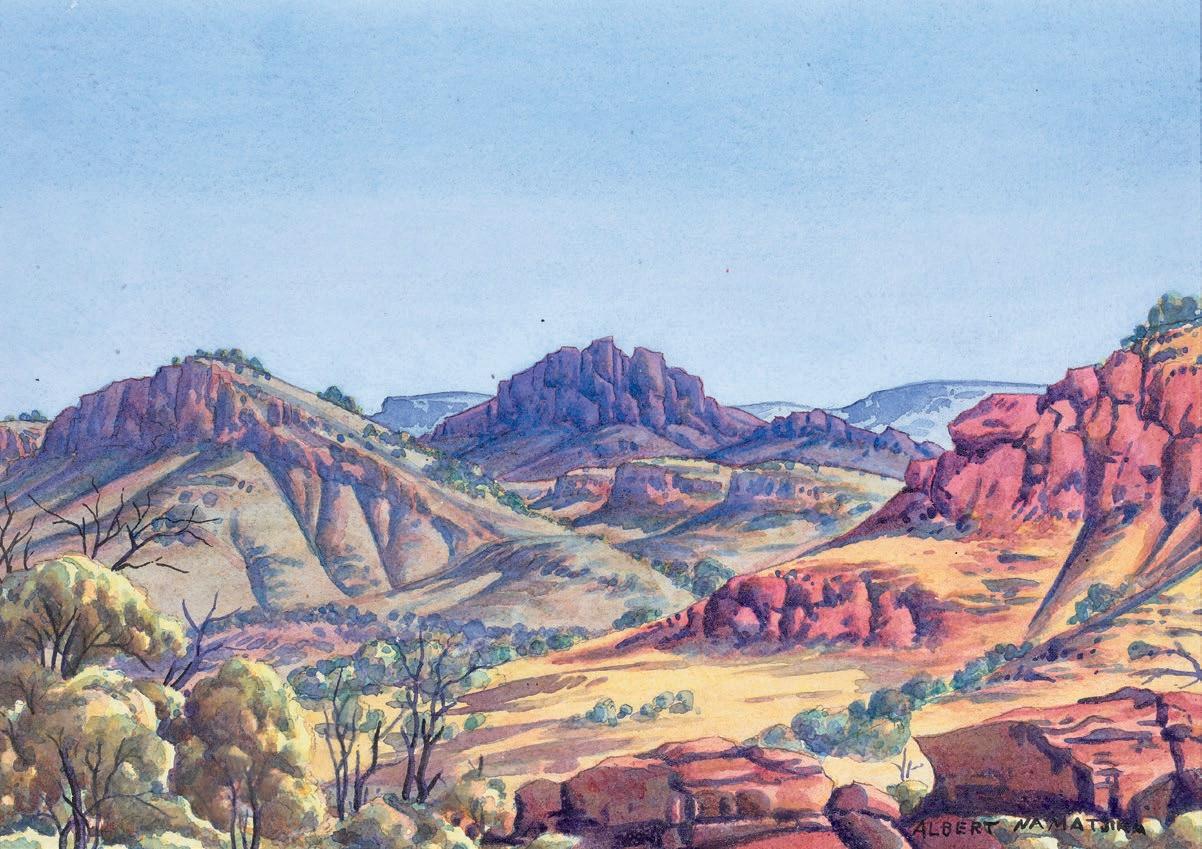

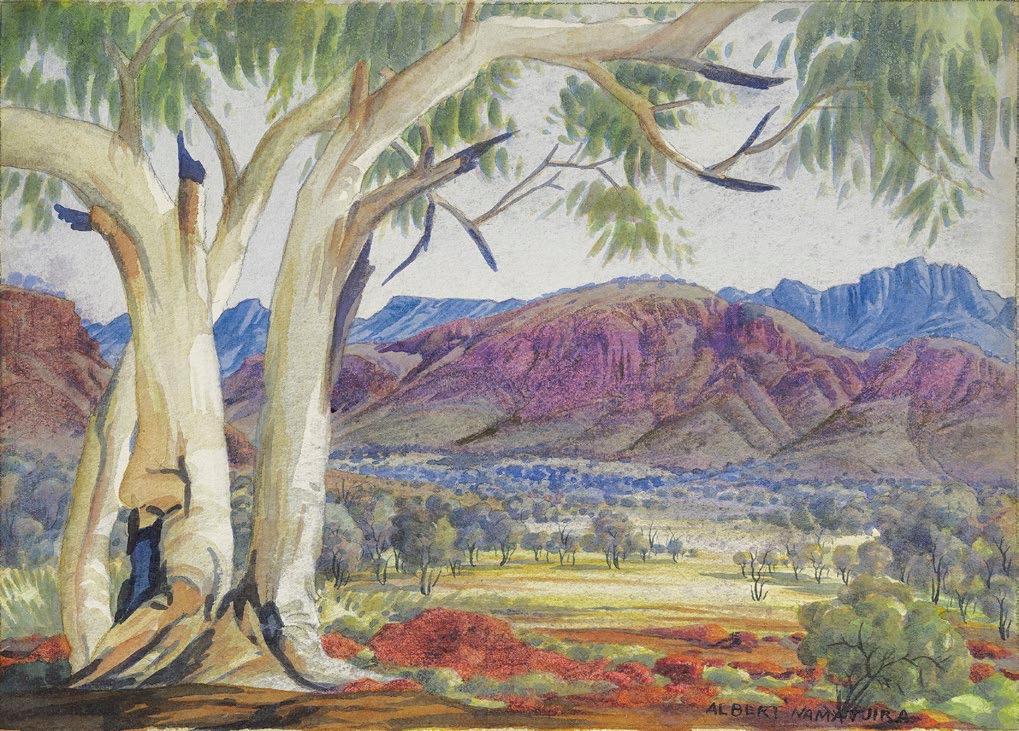

An invitation in 1975 to mount a solo exhibition of gouaches at the Museum of Modern Art in New York marked the beginning of an intensely productive period in Fred Williams’ career. He was the first Australian artist to be honoured in this way and the exhibition, which opened in March 1977, acknowledged the significance of his art and its unique vision of the landscape within a national context – both to audiences who were familiar with the country his paintings described, and beyond. Introducing the exhibition, the Director of MoMA’s Department of Drawings, William S. Lieberman, wrote: ‘Fred Williams knows Australia. He is not an artist who would disdain a gum tree. He is not a foreigner seeking to impose a natural paradise on some strange, exotic land. He is, however, a romantic artist and his approach to landscape is narrative. His images may at first seem abstract, but they in fact describe actual times and places… Fred Williams’s colours are those of the continent itself… Fred Williams’s vision is authentic.’1

In addition to international travel and an extensive program of exhibitions at home – including six solo shows presented across five states between 1975 – 78 – the second half of the 1970s saw the development of four major painting series. Continuing his well-honed practice of working directly from the landscape, Williams focussed in on particular geographical forms: pools of water (Kew Billabong); mountains (Kosciusko and Guthega); gorges (Werribee) and waterfalls. 2 Many of the sites he painted were in close proximity to his home, and the destinations of day trips made in the company of friends and fellow artists were frequently found in Williams’ copy of the newly-published edition of the Physiography of Victoria 3

The series of gorge paintings began in late 1975 following two sketching excursions to Werribee, a short distance south-west of Melbourne. The drama and varied features of the landscape obviously appealed to Williams, who returned early the following year, making a further eight visits to the area in just over two months, painting oil sketches as well as taking photographs, which he used as aide-mémoires . He worked in a different location each time – from Picnic Point, which offered a broad view over the cliffs to the dry creek bed and surrounding bush below, to Kelly’s Creek, where the perspective was closer and more intimate, noting in his diary, ‘These last three or four months have been the driest in fifty three years? so it has been a great opportunity to be doing the “Gorge” – visually it could not be seen under better conditions.’4 Williams also wrote, ‘It is quite fascinating to think of the You Yangs looking like a saw-tooth – & just a few miles away the “Gorge” doing the same thing in reverse.’ 5 This recognition of the connection between the geography of Werribee Gorge and the You Yangs – the subject of an important series of paintings produced the previous decade – provides an insight into the depth of Williams’ understanding and careful observation of the landscapes in which he worked.

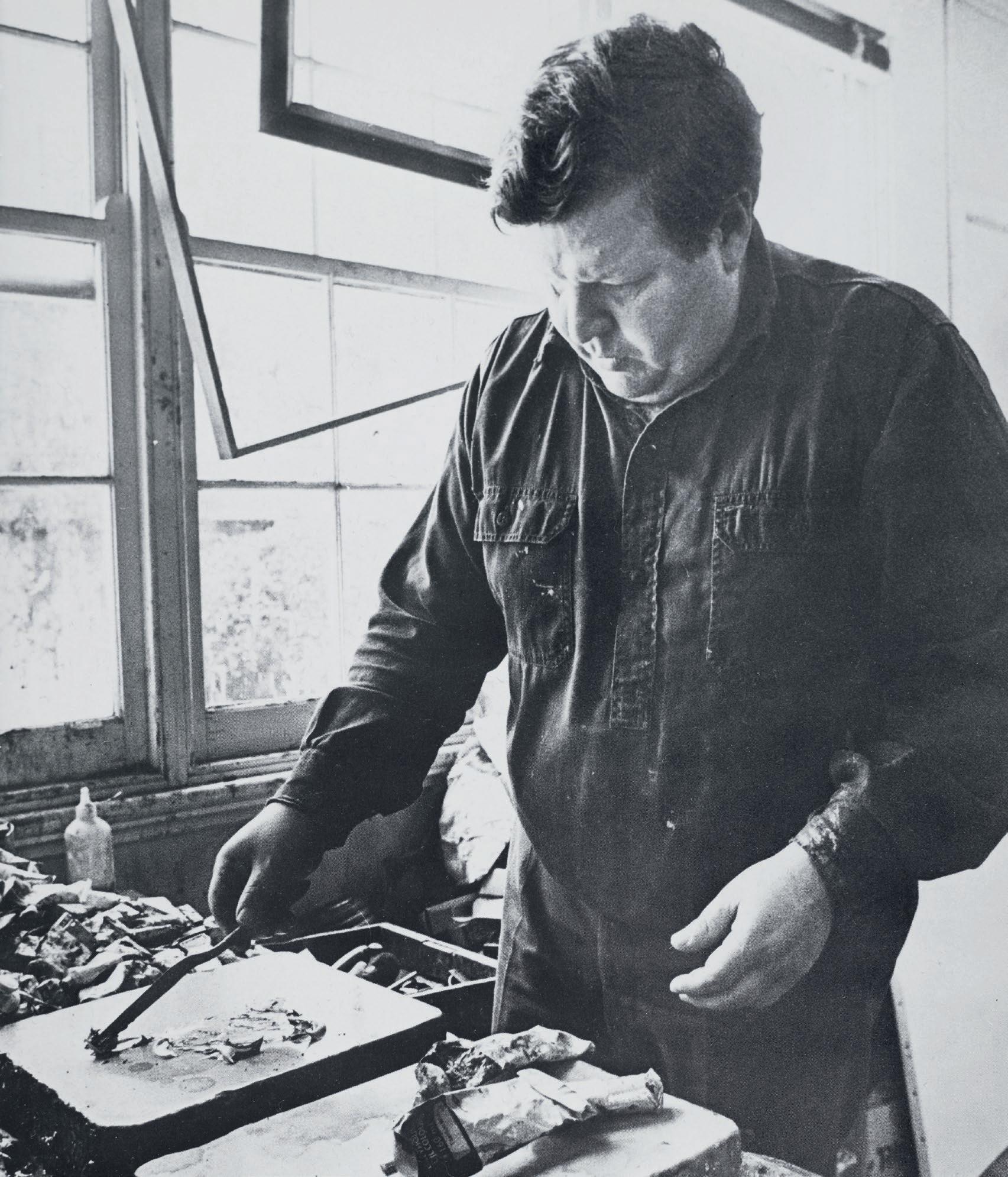

In making these paintings, Williams solidified the practice of beginning studio paintings soon after a sketching trip, while the visual and physical memory of the experience was still strong, and there was now little difference between what he termed the ‘outside’ paintings and the ‘inside’ works. Recording his excitement about this new aspect of the creative process, he wrote, ‘this is something of a milestone for me – to paint the sketch on the spot and then paint the picture!’ 6 Landscape with Creek Bed , 1976 – 77 is based on a painting Williams

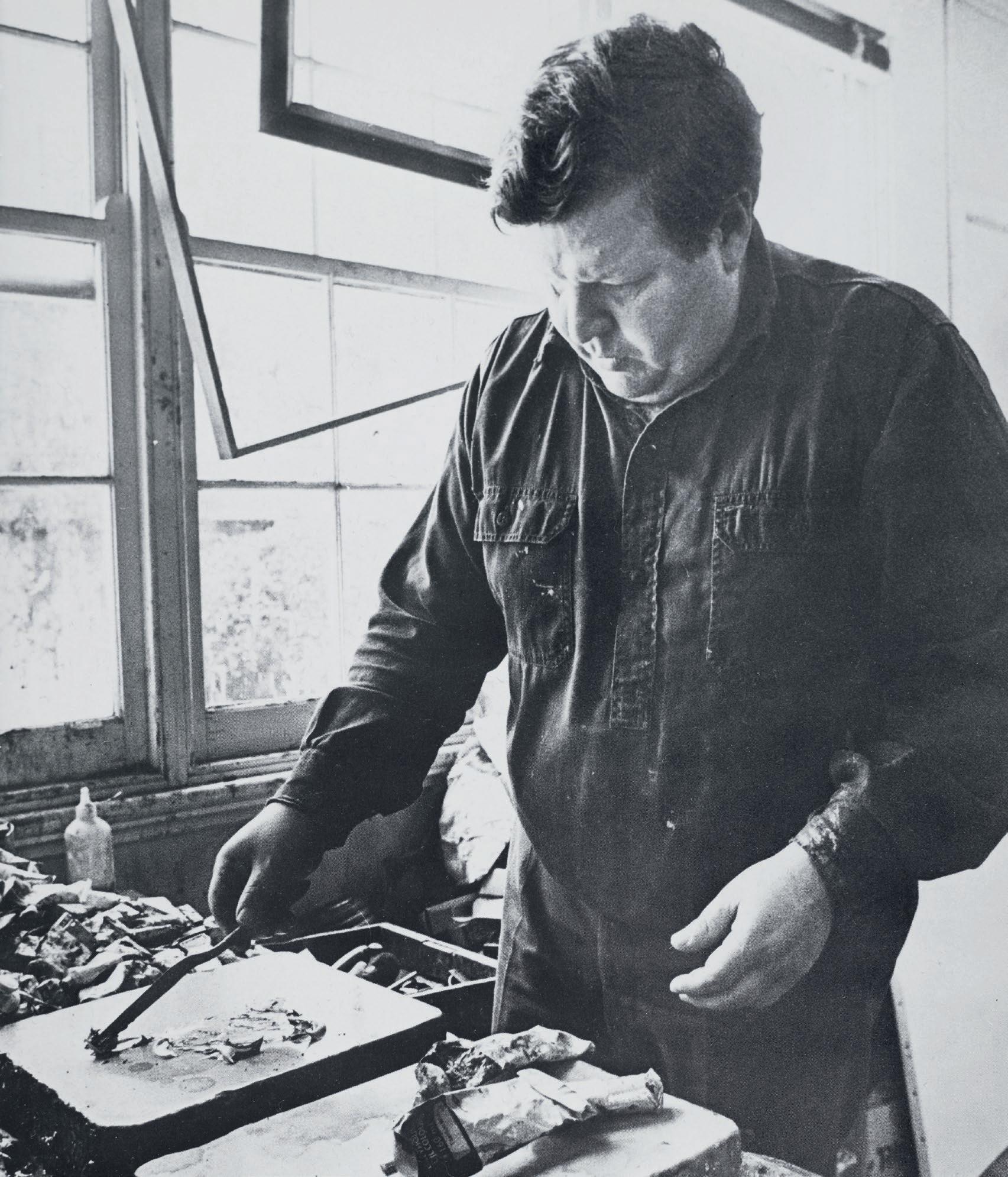

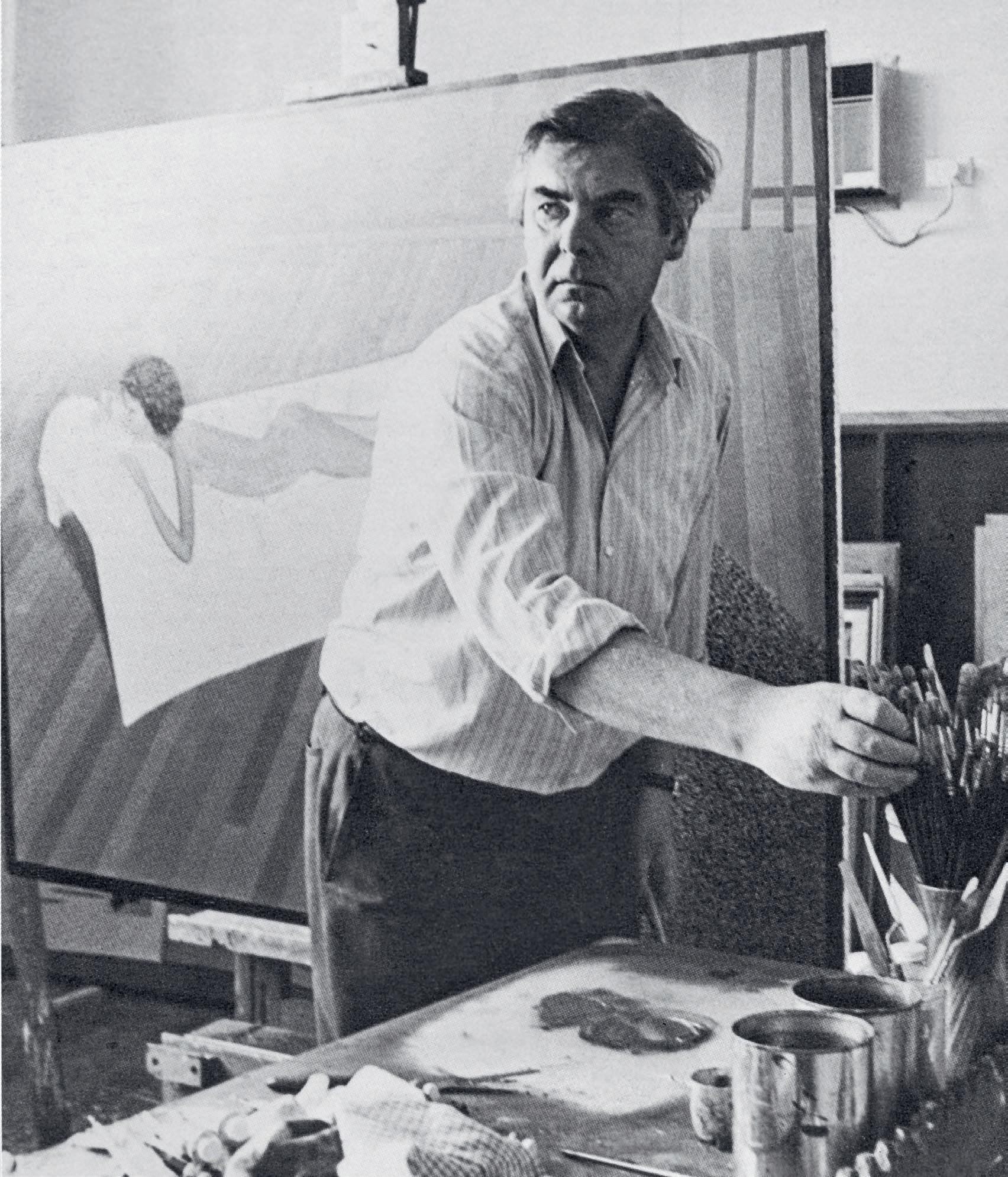

Opposite: Fred Williams photographer: Ernie McLintock © Ernie McLintock

26

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

182.3 x 152.2 cm

Tate, London

© Estate of Fred Williams / Copyright Agency

made at Kelly’s Creek in April 1976. He began working on it in the studio just three months later, and it was finished by June 1977. One of the consequences of this way of working is an immediacy in the application of paint which echoes marks made directly in front of the motif, as the hand directs the brush to record an impression of what the eye is seeing, capturing both the appearance and the feeling of the landscape. From all-over compositions like The River, Werribee Gorge , 1977 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) in which the river, seen from above, meanders through a densely treed area, to more sparse images like Dry Creek Bed, Werribee Gorge I , 1977 (Tate Gallery, London), it is the diversity of brushstrokes and a certain lightness of touch that prevails. When Landscape with Creek Bed was exhibited in a solo show at the Rudy Komon Gallery, Sydney, in April – May 1978, it was listed and displayed as a two-part work, although each canvas was sold separately. The other, closely related painting is in the Janet Holmes à Court Collection.7

Landscape with Creek Bed presents a veritable catalogue of painterly forms which are applied on top of a pale sandy ground. A black line defines the irregular path of the creek, dancing across the canvas and establishing a syncopated pictorial rhythm that reverberates throughout the painting. Thick vegetation across the top is described by a dense, richly textured band of loose, gestural brushstrokes interspersed with areas of paint that have been dabbed onto the canvas by splayed and flattened bristles of the brush. The composition opens up on either side of the creek with sparsely painted lines and characteristic dots, dashes and daubs defining the changing terrain and other observed features of the view. The bottom section of the painting is classic Williams –a series of delicate and yet energetic marks which, in their varied technique and colour, convincingly depict an open, sparsely vegetated landscape. His delight in the subject is palpable, as is the confidence of his gesture and mastery of his medium. Williams was a consummate colourist and while the first impression of this painting is one of muted

28

Fred Williams

Dry Creek Bed, Werribee Gorge I , 1977 oil on canvas

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

Fred Williams

The River, Werribee Gorge , 1977 oil on canvas

182.4 x 152.0 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

© Estate of Fred Williams / Copyright Agency

landscape tones, closer prolonged inspection reveals glimpses of brilliant colour – green, mauve and rich reds – that are such a distinctive feature of his work, and indeed, so typical of the experience of being in the Australian bush.

The Werribee Gorge paintings reveal the hand and imagination of a mature artist who is confident in his abilities and yet not content to rest on the successes of the past. Exploring new territory, both physically and artistically, Williams skilfully describes a specific location while at the time presenting a symbolic representation of the landscape which is imbued with a profound depth and emotional resonance. As Patrick McCaughey explained, ‘Each image forms a metaphor to focus the landscape and give it a new expressive power and purpose. Together, the series forms a new consciousness in Williams’s art… [reflecting] how much Williams wanted to combine inner compulsion and structural design and let them flow and be seen to flow from each other.’ 8

1. Lieberman, W. S., Fred Williams – Landscapes of a Continent , Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977, unpaginated.

2. See McCaughey, P., Fred Williams 1927 – 1982 , Murdoch Books, Sydney, revised edition, 1996, chapter 8

3. ibid., p. 290

4. Fred Williams Diary, 21 April 1976 cited in Mollison, J., A Singular Vision: The Art of Fred Williams , Australian National Gallery & Oxford University Press, Canberra, 1989, p. 205

5. Fred Williams Diary, 30 March 1976, ibid.

6. Fred Williams Diary, 30 April 1976 cited in Hart, D., Fred Williams: Infinite Horizons , National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2011, p. 148

7. See Hart, ibid., pp. 145 – 6

8. McCaughey, op. cit., p. 284

KIRSTY GRANT

29

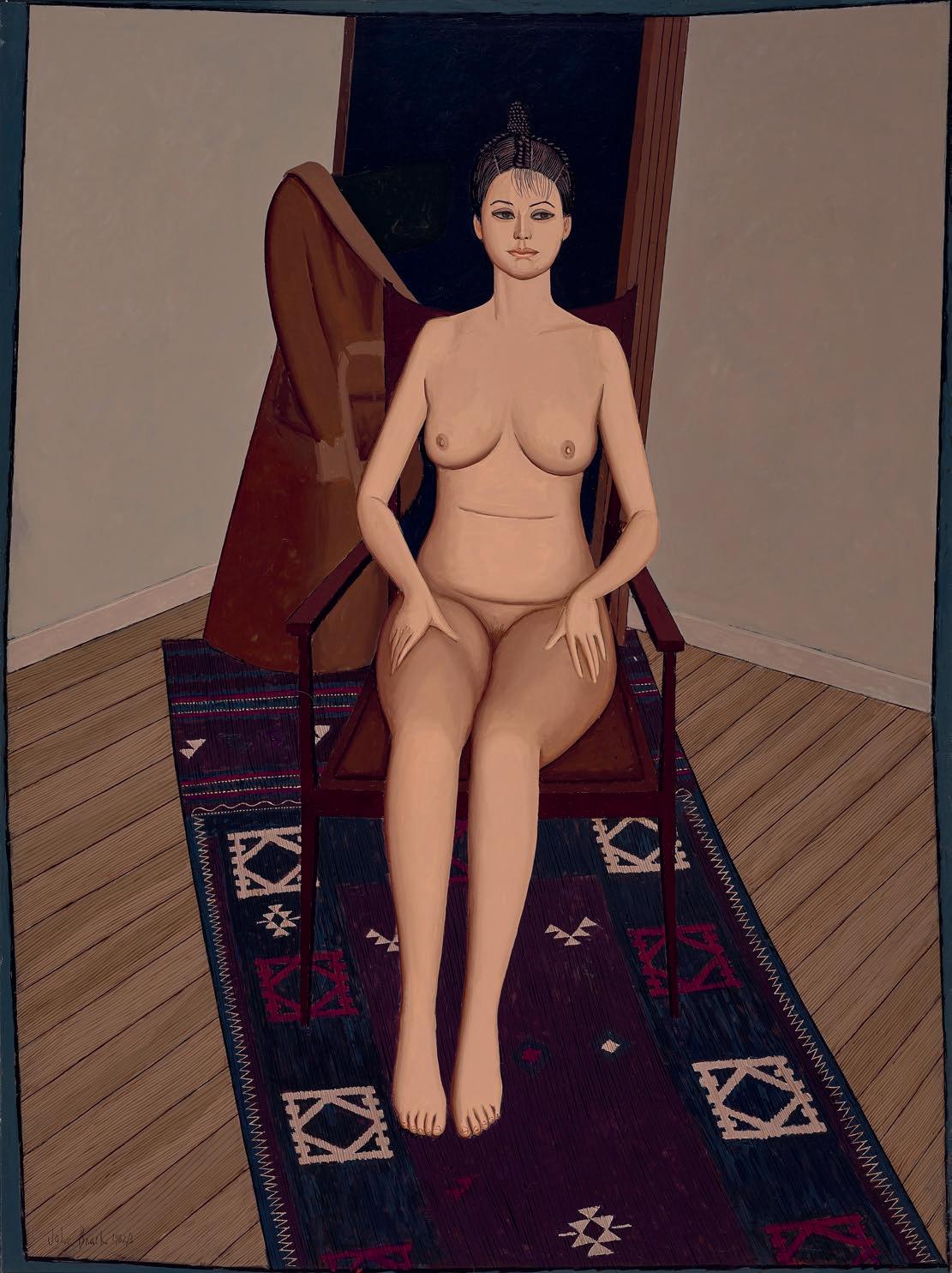

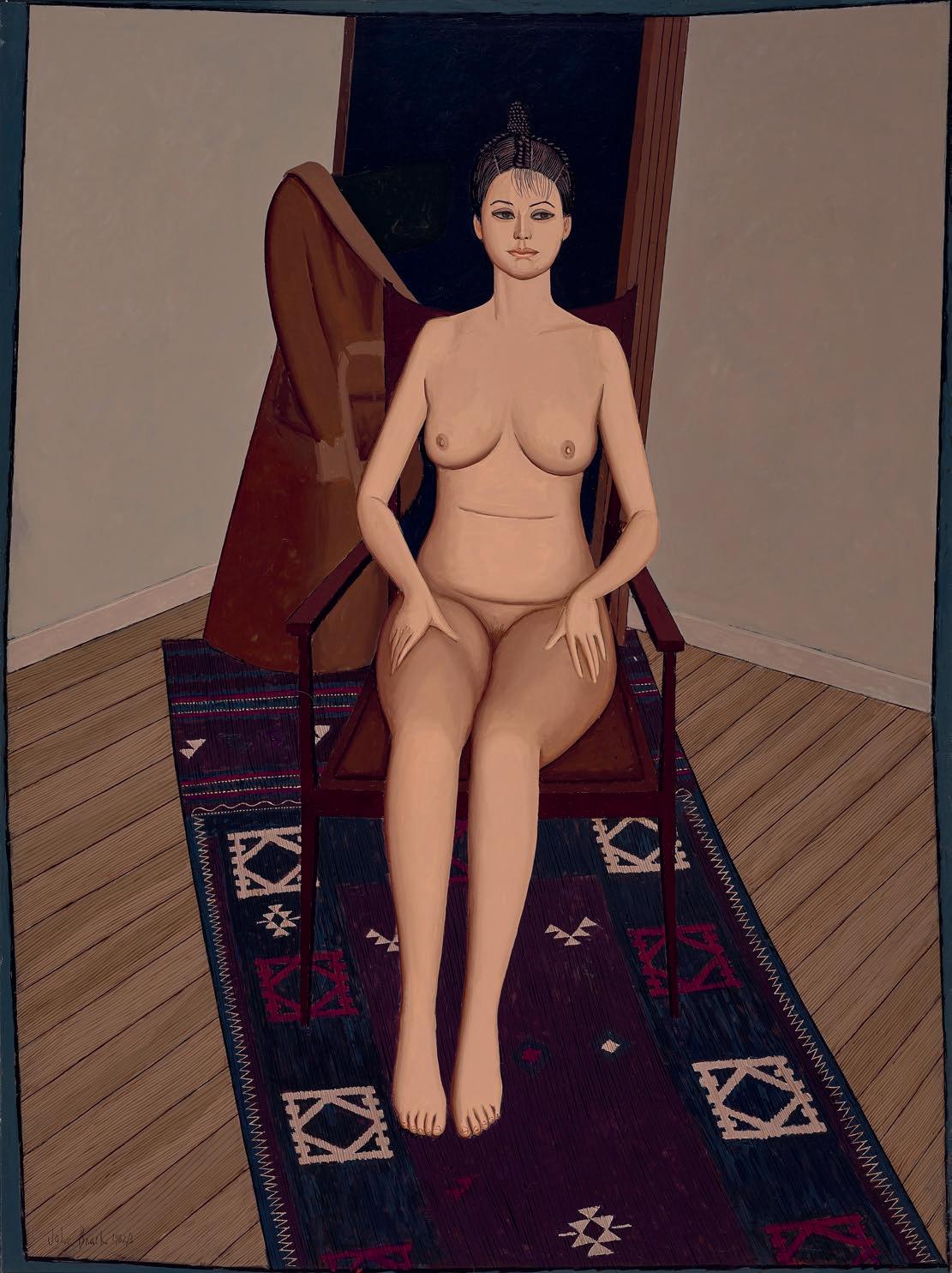

SEATED NUDE WITH SCREEN, 1982 – 83 oil on canvas

130.0 x 97.0 cm

signed and dated lower left: John Brack 1982/3

inscribed with title on artist's label attached verso: 'SEATED NUDE WITH SCREEN'

ESTIMATE: $500,000 – 700,000

PROVENANCE

Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1983

EXHIBITED

John Brack , Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 21 May – 11 June 1983, cat. 9

John Brack: A Retrospective Exhibition , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 10 December 1987 – 31 January 1988, cat. 105

The Nude in the Art of John Brack, McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park, Victoria, 17 December 2006 – 25 March 2007, cat. 15

John Brack Retrospective , The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, 24 April – 9 August 2009 and touring to Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2 October 2009 – 31 January 2010 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Lindsay, R., John Brack: A Retrospective Exhibition , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, pp. 73 (illus.), 134, 141 Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack , Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, vol. 1, p. 160, vol. 2, cat. o275, pp. 36, 171 (illus.)

Klepac, L., Australian Painters of the Twentieth Century, Beagle Press, Sydney, 2000, p. 168 (illus.)

Lindsay, R., The Nude in the Art of John Brack , McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park, Victoria, 2006 (illus., np)

Grant, K., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 187 (illus.), 225

30

3 JOHN BRACK (1920 – 1999)

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

31

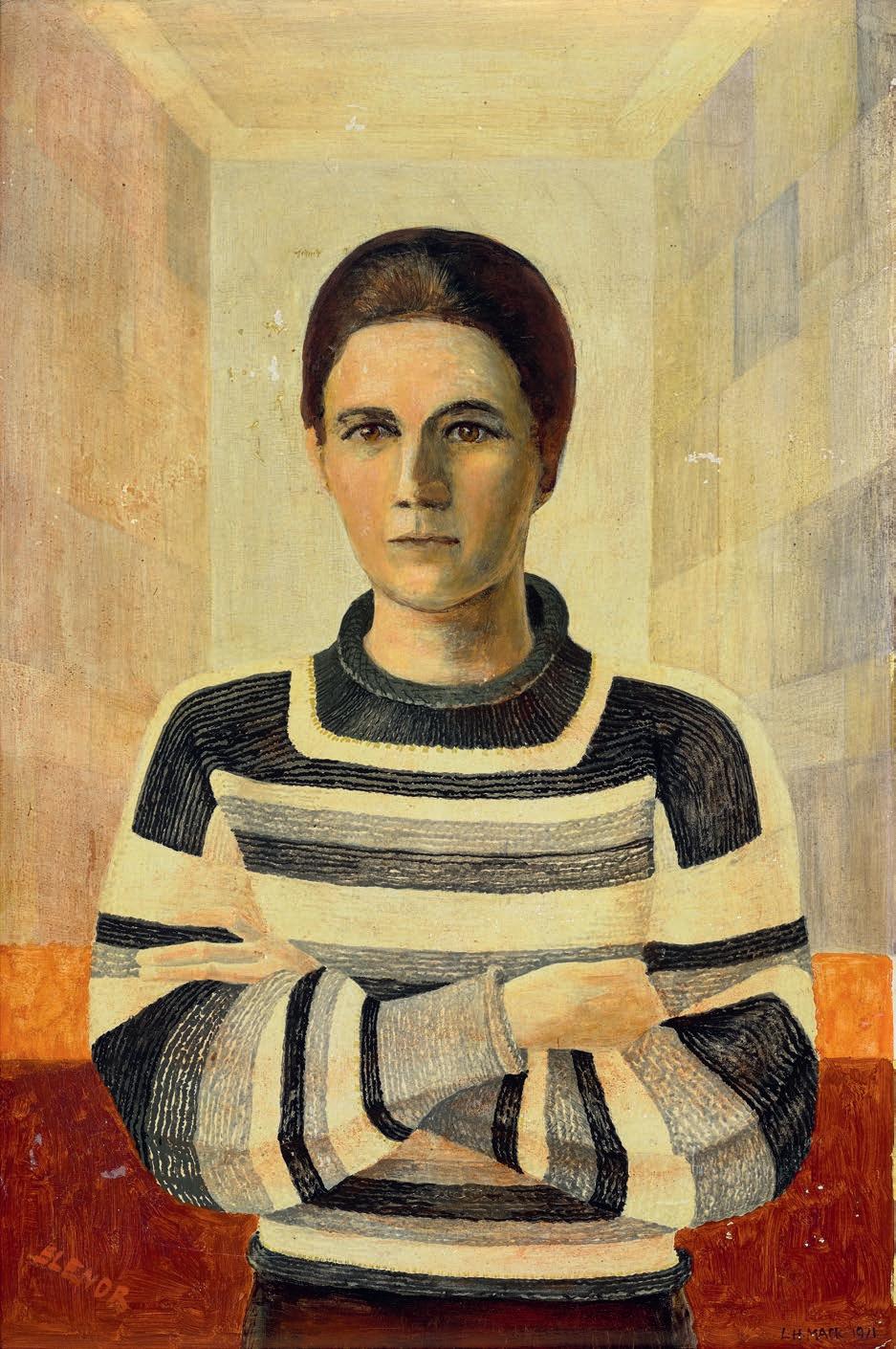

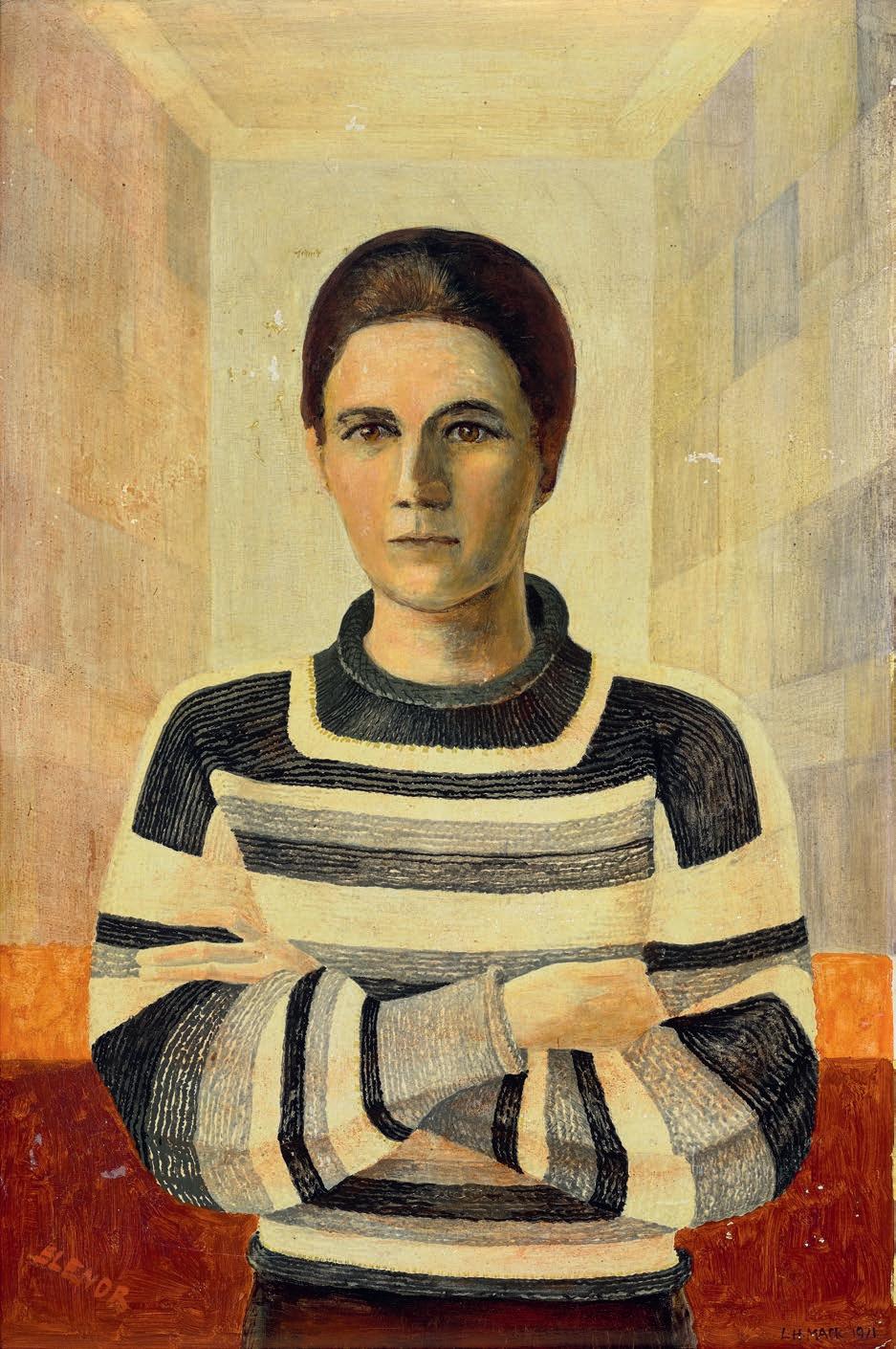

Like all artists of his generation, John Brack was well-versed in the history of Western art and it remained an essential touchstone throughout his career. A survey of his painting reveals references to significant historical works by artists as diverse as Boucher, Seurat and Buffet, which provided inspiration as he borrowed from earlier masters and challenge as he pitted himself against them. His iconic painting, The bar, 1954 (National Gallery of Victoria), for example, appropriates both the subject and composition of Édouard Manet’s famous depiction of A bar at the Folies-Berg è re , 1882 (Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London). In Brack’s characteristic way however, the PostImpressionist’s clever visual trick of depicting the scene in front of the barmaid reflected in a mirror is used to describe the subject as he witnessed it in 1950s Melbourne – a drab image of dour-faced workers who are urgently drinking their fill before the imminent early closing of the pub rather than the gay opulence of 1880s Paris.

Working within the traditional genres of painting, Brack explored the still-life, portraiture and the nude in his art. Landscape as a theme however, is largely absent from his oeuvre, and indeed, when his friend and fellow artist, Fred Williams, announced that he intended to make the Australian landscape the focus of his art, Brack was sceptical, doubting its relevance as a subject for contemporary painting. Always underlying Brack’s approach – and explaining his avoidance of landscape as a subject – was an enduring interest in the human condition. As he said,

‘What I paint most is what interests me most, that is, people; the Human Condition, in particular the effect on appearance of environment and behaviour… A large part of the motive… is the desire to understand, and if possible, to illuminate… My material is what lies nearest to hand, the people and the things I know best.’1

In the context of the nude, Brack described this focus on human nature in the following way: ‘When I paint a woman… I am not interested in how she looks sitting in the studio, but in how she looks at all times, in all lights, what she looked like before and what she is going to look like, what she thinks, hopes, believes, and dreams. The way the light falls and casts its shadows is merely… a hindrance unless it helps me to show these things.’ 2 Embarking on his first sustained series of paintings of the nude during the mid-1950s, Brack sought to test the development of his work through a return to the rigour and discipline of life drawing and placed an advertisement for a model in the newspaper. Questions about how he might make a new and meaningful contribution to the genre were answered by the single response he received, from a thin middle-aged woman whose appearance demanded a radically different approach that was far removed from the sensual nudes of earlier artists such as Rubens and Gauguin. Brack quickly realised that ‘there is absolutely nothing whatsoever erotic in an artist’s model unclothed in a suburban empty room’ 3, and produced a series of striking paintings including Nude in an armchair, 1957 (National Gallery

Opposite:

32

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

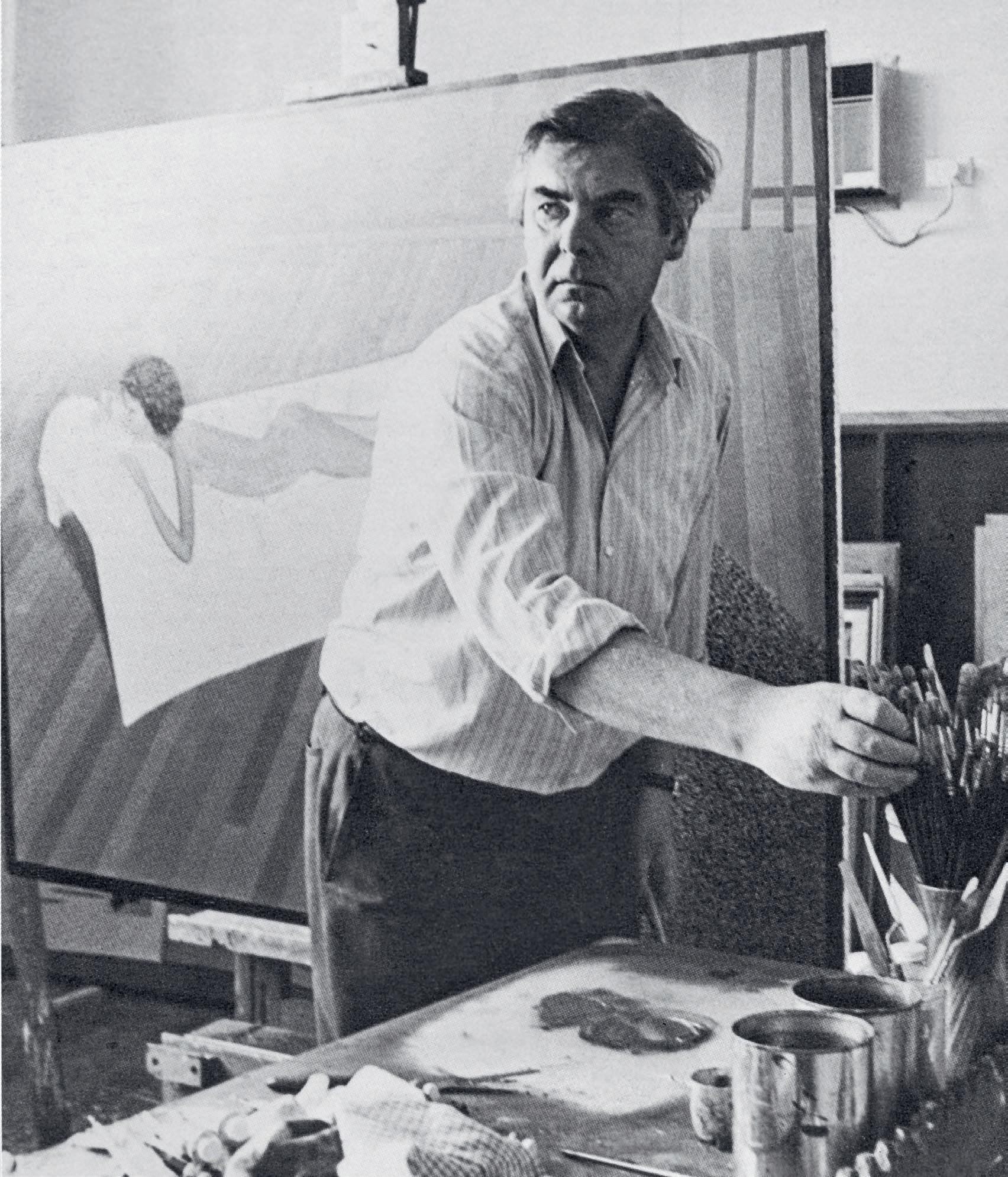

John Brack in his studio with easel and paint completing ‘Nude on shag rug 1976 – 77’, February 1977 photographer unknown

of Victoria) and The bathroom , 1957 (National Gallery of Australia), that boldly challenged expectations of the subject. While some lamented the skinny, sexless appearance of the model, art critic Alan McCulloch wrote that in pitting himself against tradition Brack had successfully demonstrated that ‘he [was] on all occasions master of the medium.’4

The nude returned as a major subject within Brack’s oeuvre during the 1970s and 80s and in these works a restrained sensuality and pleasure in depicting the female form is apparent. The contrast between the uncomfortable tension of the 1950s nudes and paintings like Seated nude with screen , 1982 – 83, where the subject looks out at the viewer completely at ease with her nakedness, seems to reflect the changes in social mores that had taken place in the intervening years and the increased informality of the late twentieth century. These differences might also point to the development of Brack’s own confidence and artistic maturity. In the mid-1950s he was at the beginning of his career

with a handful of solo exhibitions to his name, still defining his visual language and establishing his artistic persona. In 1968, with the help of a monthly stipend from his Sydney dealer Rudy Komon, Brack had resigned from his position as Head of the National Gallery School in Melbourne and for the first time in his life was able to paint fulltime. The ensuing decades witnessed regular solo exhibitions, private commissions, as well as other public affirmations of his art.

Like all of the nudes from this time, Seated nude with screen was painted in Brack’s studio and features its distinctive timber floorboards and unadorned walls, as well as a Persian carpet, which is rendered in characteristically intricate detail. Helen Brack interprets these carpets as symbolising the world of men and in the context of images where the subject is always female, this has a particular relevance. 5 In addition to highlighting what the artist perceived as the differences between the sexes, this pictorial device also illustrates the counterbalance they

34

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

Installation photograph from the retrospective John Brack , held at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, 2009

John Brack

Nude in an armchair, 1957 oil on canvas

127.6 x 107.4 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

© Helen Brack

provide each other.6 In this painting, the centrally-placed figure is prominent within the composition, and the all-over pale tone of her bare skin contrasts with the dark colours and decorative detail of the carpet. Brack has also paid particular attention to the model’s hair, carefully describing its elaborate braiding and the bun that is neatly coiled on top of her head. The model’s clothing often features in these paintings, discarded and casually draped nearby. Here, the figure’s overcoat –presumably hanging on a hook which is attached to the folded screen in the background – assumes a strangely anthropomorphic character and suggests the presence of another figure in the room. What ultimately prevails in this painting however, is what Patrick McCaughey astutely described as Brack’s ‘paramount… sense of observed reality.’ 7

Joan and Peter Clemenger purchased this painting from Brack’s 1983 exhibition at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne and, apart from being displayed in several subsequent museum exhibitions – including both

John Brack

The bathroom , 1957 oil on canvas

129.4 x 81.2 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

© Helen Brack

the 1987 and 2009 retrospectives at the National Gallery of Victoria – it has graced the walls of their home ever since. 8

1. Brack cited in Reed, J., New Painting 1952 – 62 , Longman, Melbourne, 1963, p. 19

2. Brack, H., ‘This Oeuvre – The Work Itself’, in Grant, K., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, p. 16

3. Brack, J., Interview, Australian Contemporary Art Archive, no. 1, Deakin University Media Production, 1980, transcript, p. 6

4. McCulloch, A., ‘Classical themes’, Herald , 13 November 1957, p. 29

5. See Lindsay, R., The Nude in the Art of John Brack , McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park, 2007, unpaginated

6. See Helen Brack cited in Gott, T., A Question of Balance: John Brack 1974 – 1994 , Heide Museum of Modern Art, Bulleen, 2000, p. 23

7. McCaughey, P., ‘The Complexity of John Brack’ in Lindsay, R., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, p. 9

8. See exhibition history noted above in the caption for this lot.

KIRSTY GRANT

35

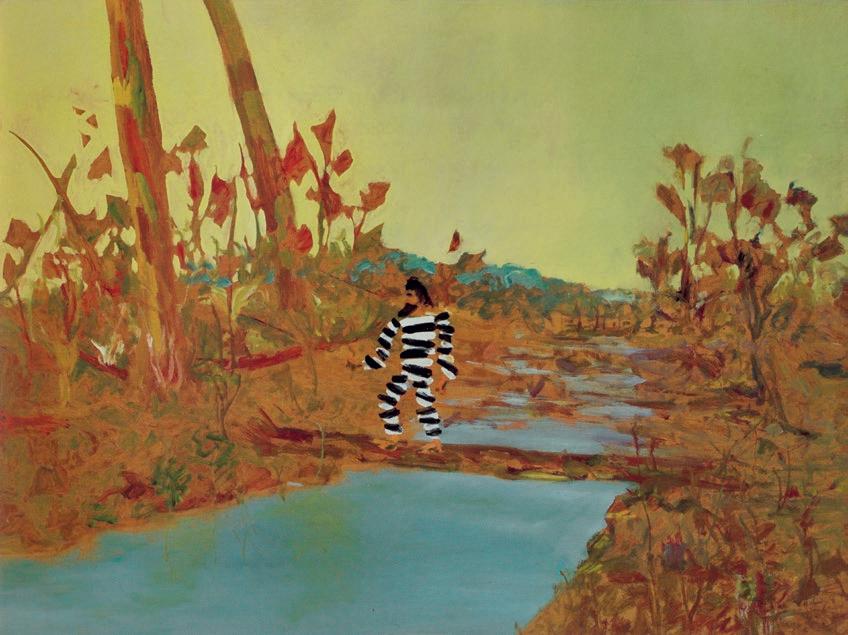

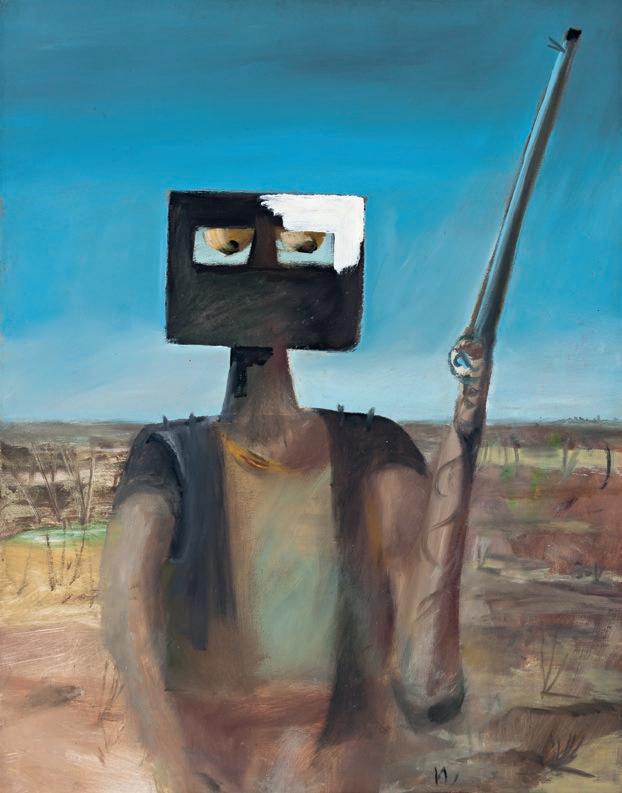

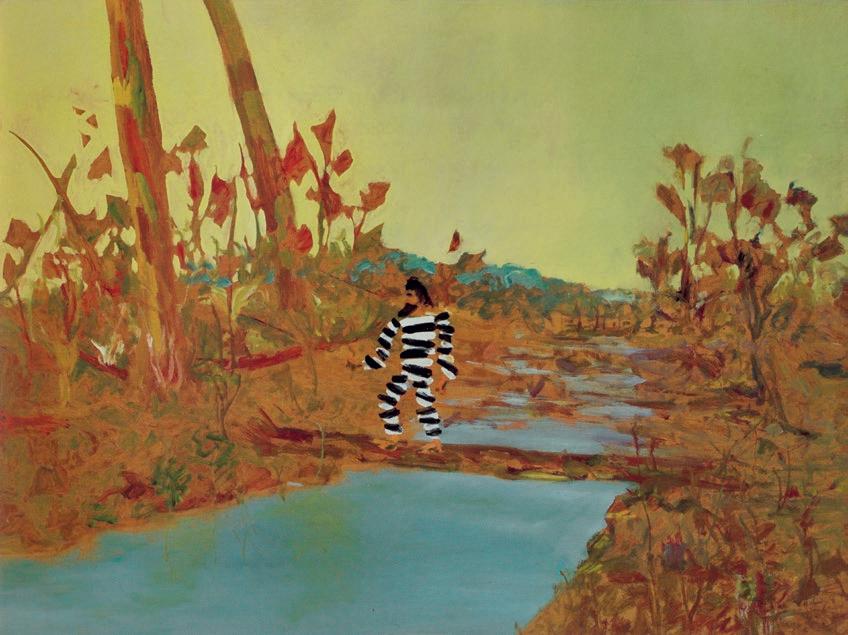

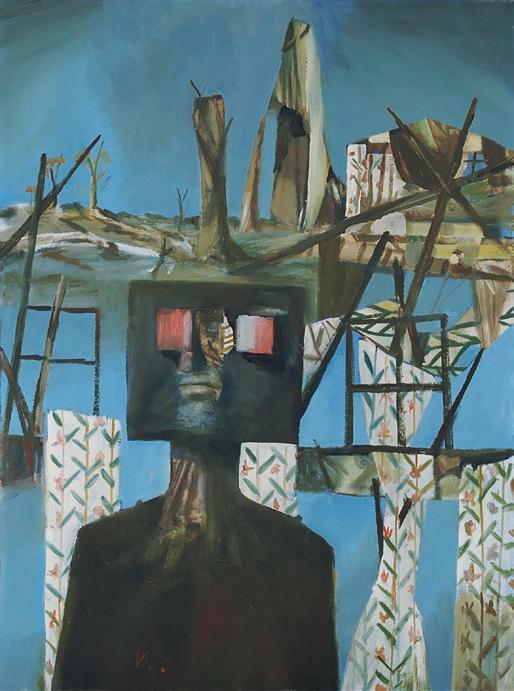

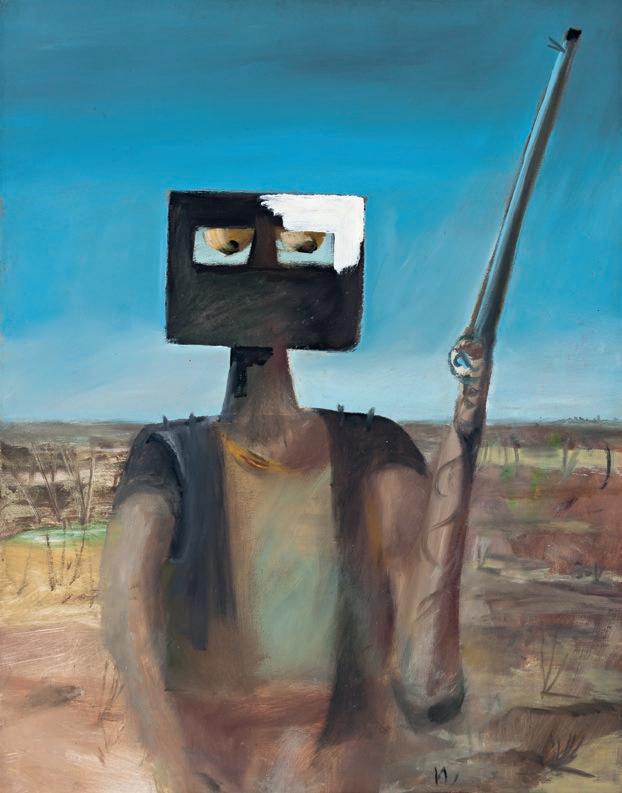

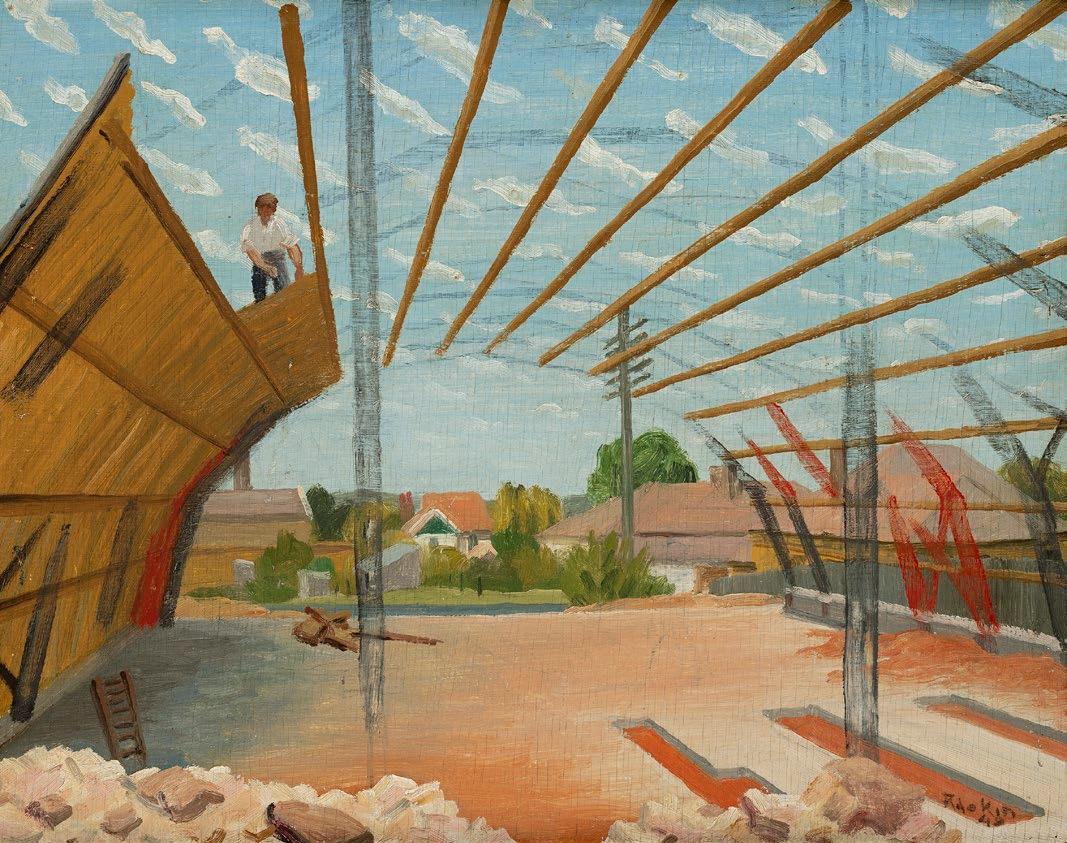

4 SIDNEY NOLAN (1917 – 1992) ESCAPED CONVICT, 1948 enamel paint on composition board 122.0 x 91.5 cm signed and dated lower right: 1-6-48 / Nolan

ESTIMATE: $650,000 – 850,000

PROVENANCE

Simon Sainsbury, London, by 1961

Terry Clune Galleries, Sydney

Victor Macallister, New South Wales, acquired from the above in 1964

Thence by descent

Private collection, Victoria

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in May 2010

EXHIBITED

Sidney Nolan: Queensland Outback Paintings, David Jones Art Gallery, Sydney, 8 – 22 March 1949, cat. 7 Sidney Nolan , Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, June – July 1957, cat. 18 (illus. in exhibition catalogue pl. VI)

Sidney Nolan: retrospective exhibition, Paintings from 1937 to 1967, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 13 September – 29 October 1967; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 22 November – 17 December 1967; Western Australian Art Gallery, Perth, 9 January – 4 February 1968, cat. 38 (label attached verso, as 'Convict')

Sidney Nolan: 102 works from the first fifteen years (1939 – 53), Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne, 25 July – 7 August 1979, cat. 58 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Collectable + Exceptional, The Director’s Choice 2010 , Gould Galleries, Melbourne, 6 May – 5 June 2010, cat. 2 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

LITERATURE

MacInnes, C., and Robertson, B., Sidney Nolan , Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, reprinted 1967, pl. 31 (illus.)

Artists of Australia, Adelaide, 1965

Osbourne, C., Masterpieces of Nolan , Thames and Hudson, London, 1975, cat. 3 (illus.)

Clark, J., Sidney Nolan: Landscapes and Legends , International Cultural Corporation of Australia, Sydney, 1987, p. 99

36

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

37

In 1947, Sidney Nolan made his escape from the cloying, claustrophobic world of Heide, and from the toxic symbiosis of his relationship with John and Sunday Reed.

The Templestowe cultural Camelot was falling apart. Max Harris had resigned from Reed and Harris and returned to Adelaide in September 1946. Albert Tucker went to Japan as an Allied Forces war artist in February 1947, and following the collapse of his marriage to Joy Hester, would leave again – for Europe – in September. Danila Vassilieff became a little detached following his marriage to Elizabeth Hamill in March. Hester eloped to Sydney with Gray Smith in April.

And in July, perhaps (ironically) inspired by the Reed’s enthusiastic accounts of their Sunshine State holiday in late 1946, Nolan flew off to Brisbane, famously leaving behind with Sunday the first series of his celebrated Ned Kelly paintings. There he was welcomed by the young Queensland poet Barrett Reid, a visitor to Heide during the previous summer, with whom he travelled even further north: to Bundaberg, Tamborine, Maryborough, and Fraser Island. Reid also introduced the painter to the city’s literary and artistic pocket avant-garde , and to the resources of the John Oxley Library, the local heritage collection of the State Library.

91.1 x 121.4 cm

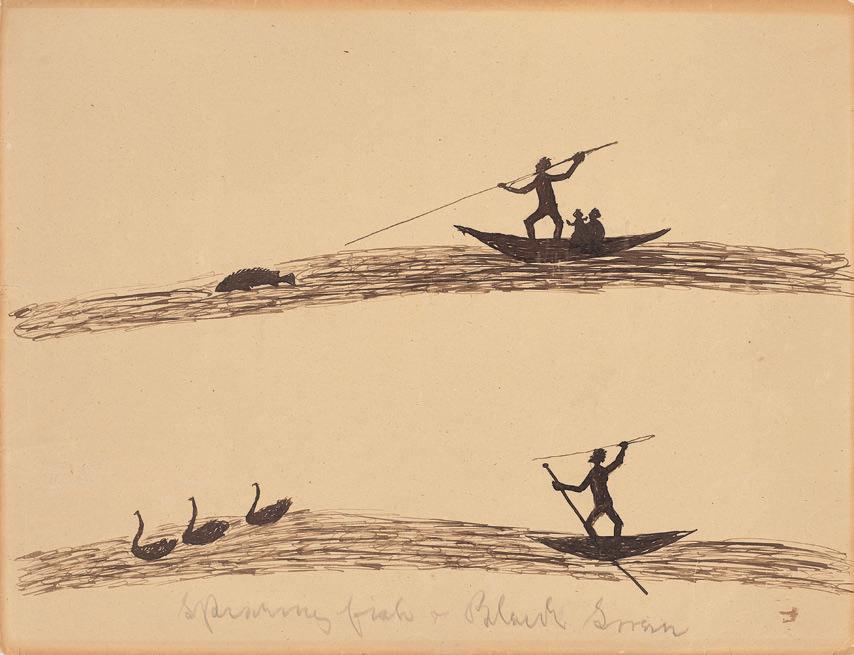

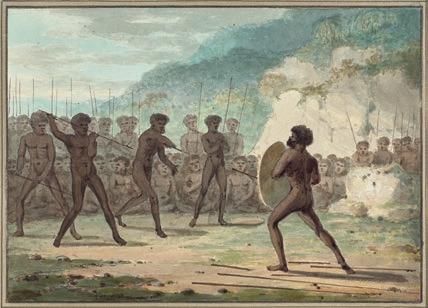

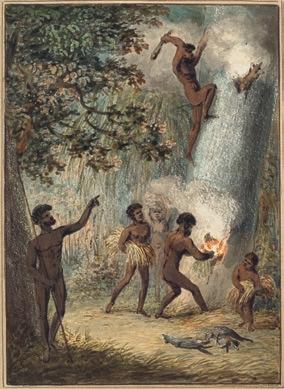

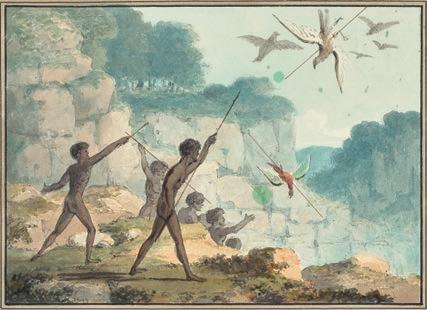

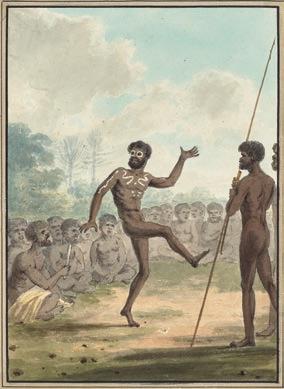

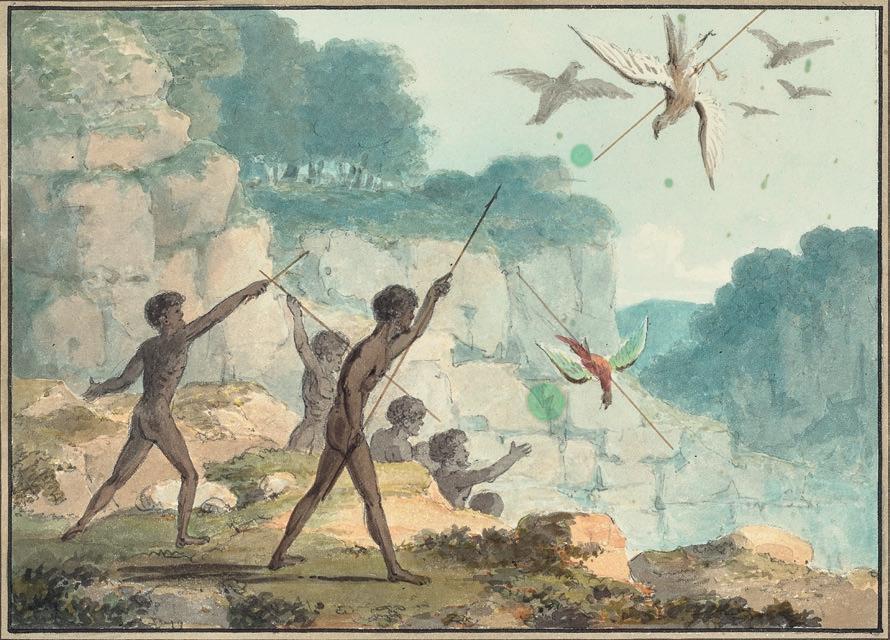

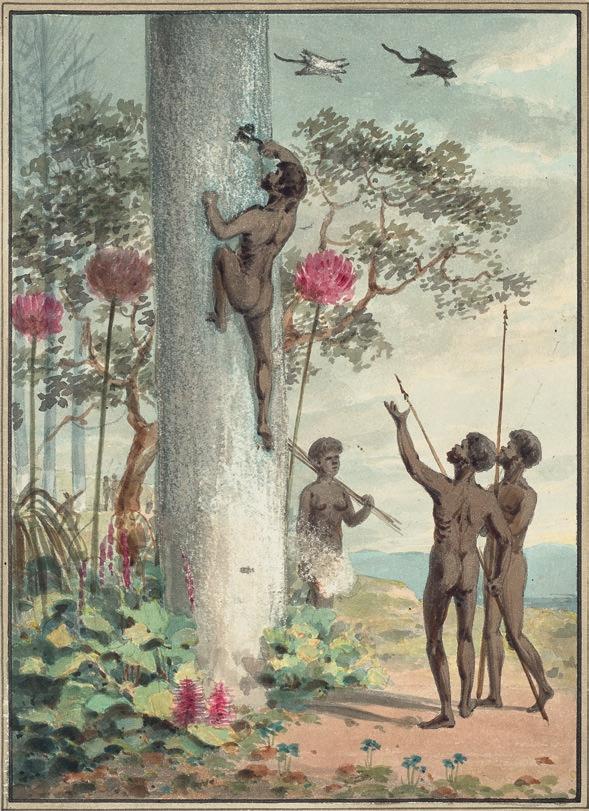

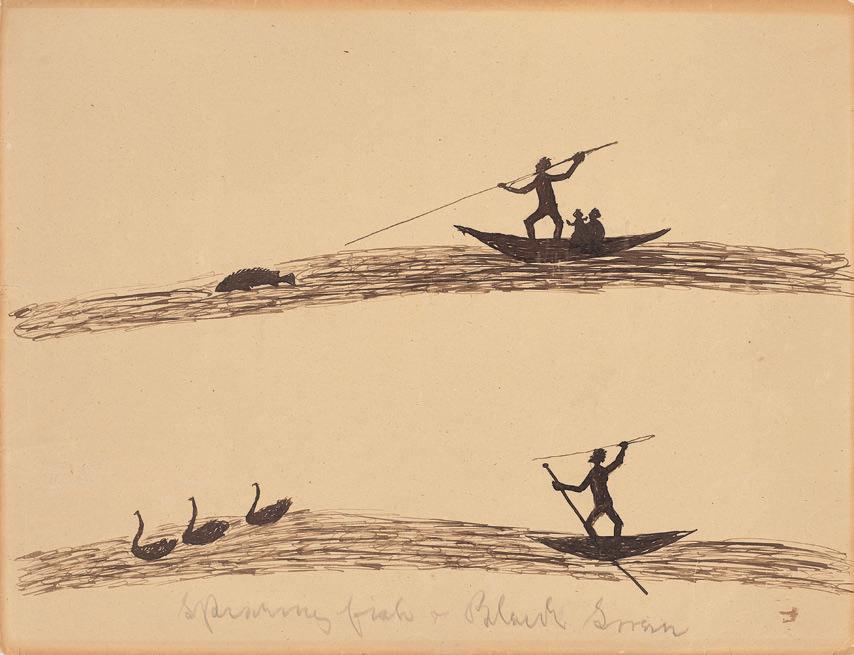

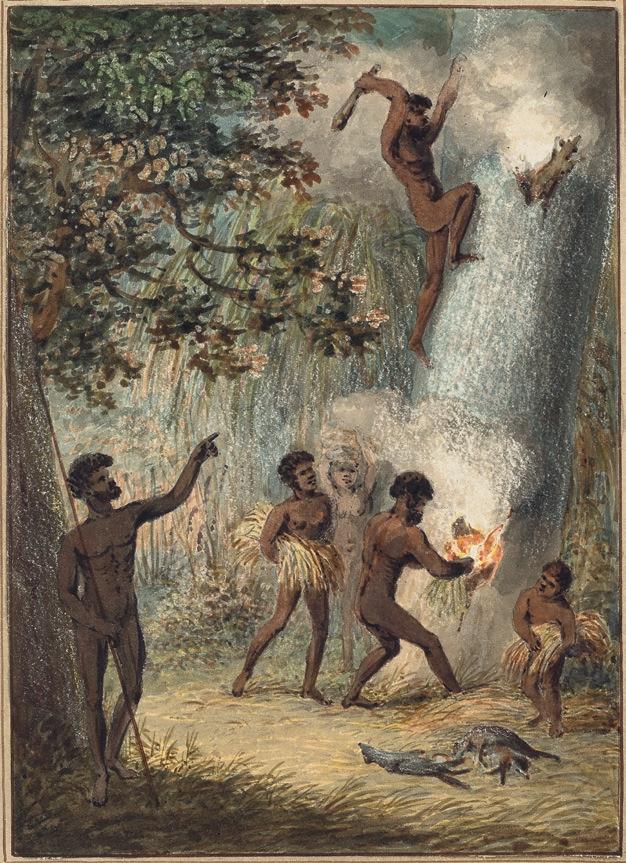

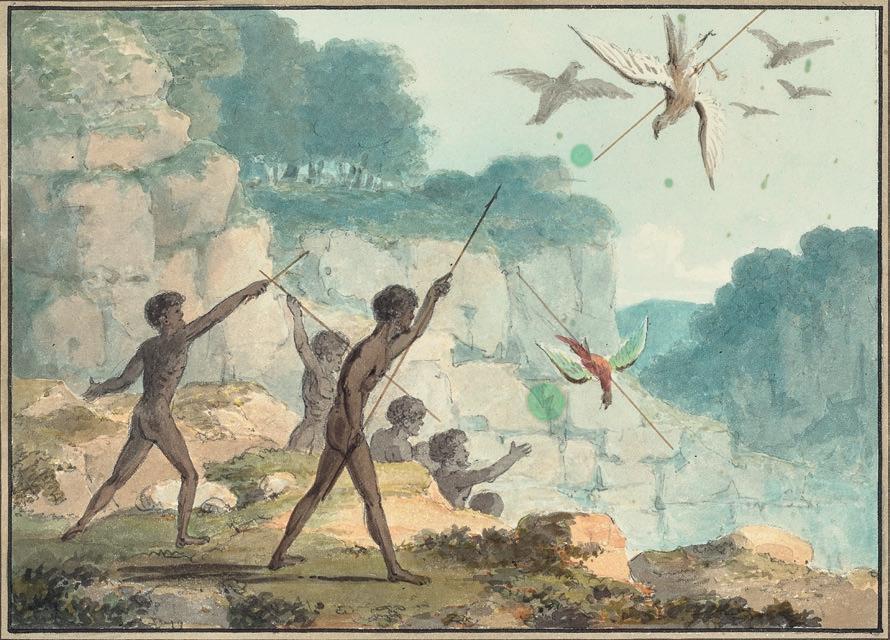

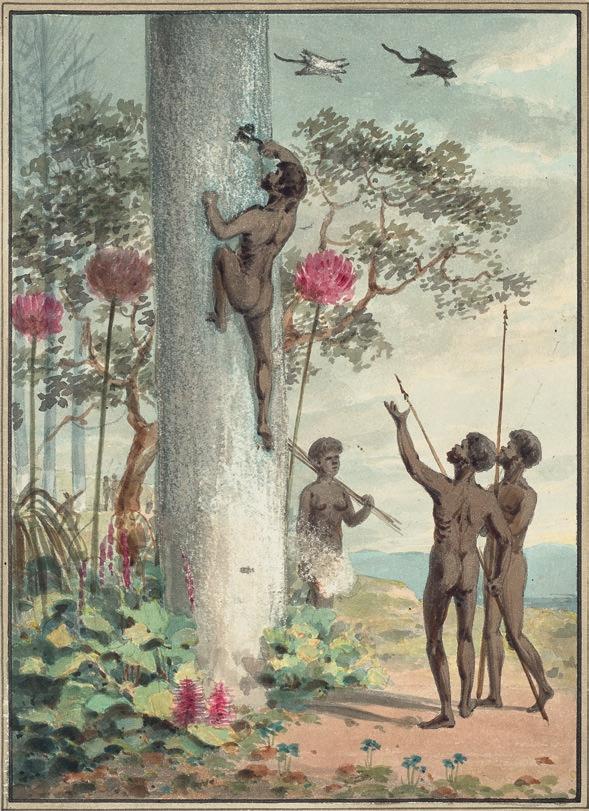

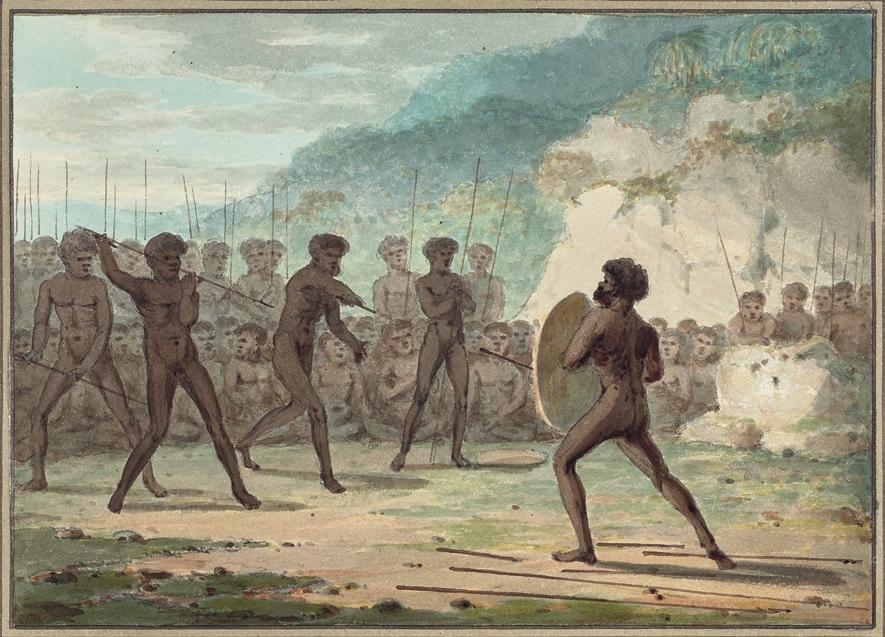

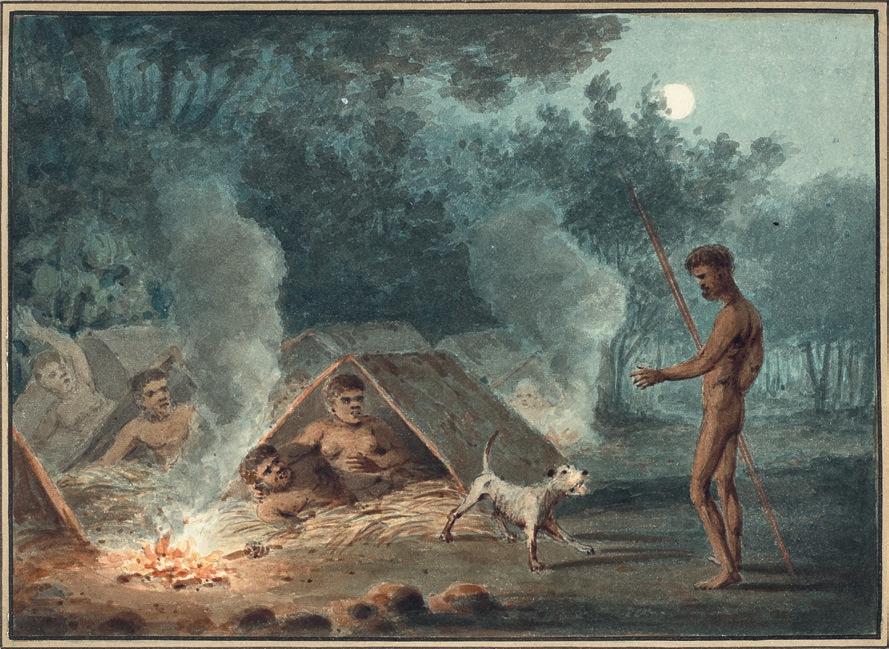

As he had with the Kelly story, Nolan discovered and delighted in the artistic potential of archival research. Initially interested in Lieutenant James Cook’s travels up the east coast of Australia in 1770, he eventually latched onto accounts of the wreck of the brig Stirling Castle on the Swain Reefs, north of K’gari/Fraser Island, in 1836. This pathetic and controversial colonial tale has been retold many times, but in 1947 the two key historical publications available to Nolan were John Curtis’s sensational version of 1838, ostensibly from Eliza Fraser’s own account, and a later and more empirically oriented history by Robert Gibbings, John Graham: convict (1937).1

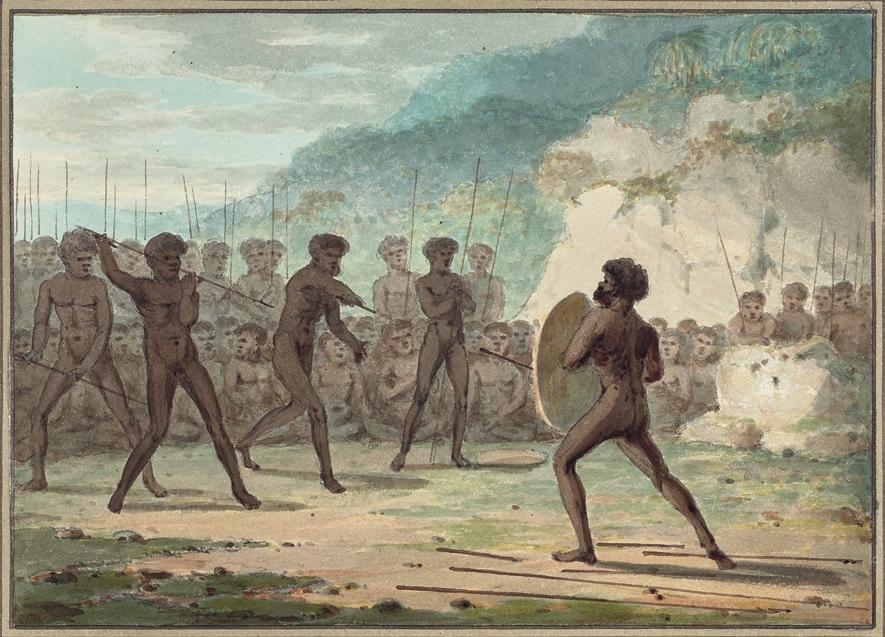

The Eliza Fraser story absorbed by Nolan can be briefly summarised as follows: the Stirling Castle , en route to Singapore under the command of James Fraser, was wrecked in a storm off the coast from present-day Rockhampton, with the survivors travelling south in the ship’s boats and landing on what was then called Great Sandy Island. There a number perished, some (including Captain Fraser) at the hands of local Butchulla people, but with the captain’s wife surviving. After two months of ‘captivity’, she was eventually ‘rescued’ from the natives and guided to ‘civilisation’ at Moreton Bay by an escaped convict, David Bracefell, on whose behalf she promised to speak to the authorities. However, once within sight of settlemen t she reneged on her promise, and Bracefell returned to the bush.

38

Sidney Nolan Escaped Convict , 1948 enamel paint on composition board

Private collection

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

© The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust / DACS / Copyright Agency

Sidney Nolan

Death of Captain Fraser, 1948

enamel paint on board

91.2 x 122.4 cm

Canberra Museum + Gallery, Canberra

© The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust / DACS / Copyright Agency

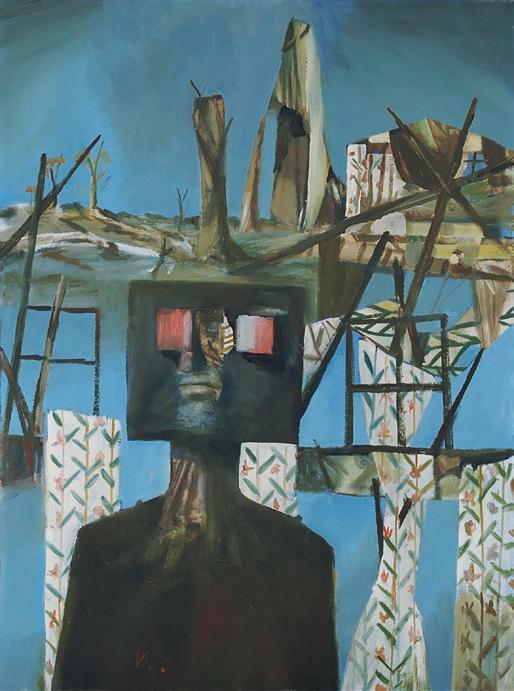

The following year, while now married to Cynthia Reed and comfortably settled in Sydney, Nolan evidently still felt keenly that he had suffered a comparable betrayal at the hands of Sunday Reed, and he completed a new series of paintings that had begun with Mrs Fraser, 1947 (Queensland Art Gallery I Gallery of Modern Art) and the Death of Captain Fraser, 1948 (Canberra Museum and Art Gallery), and included others such as the present work depicting the abandoned Bracefell alone in the bush.

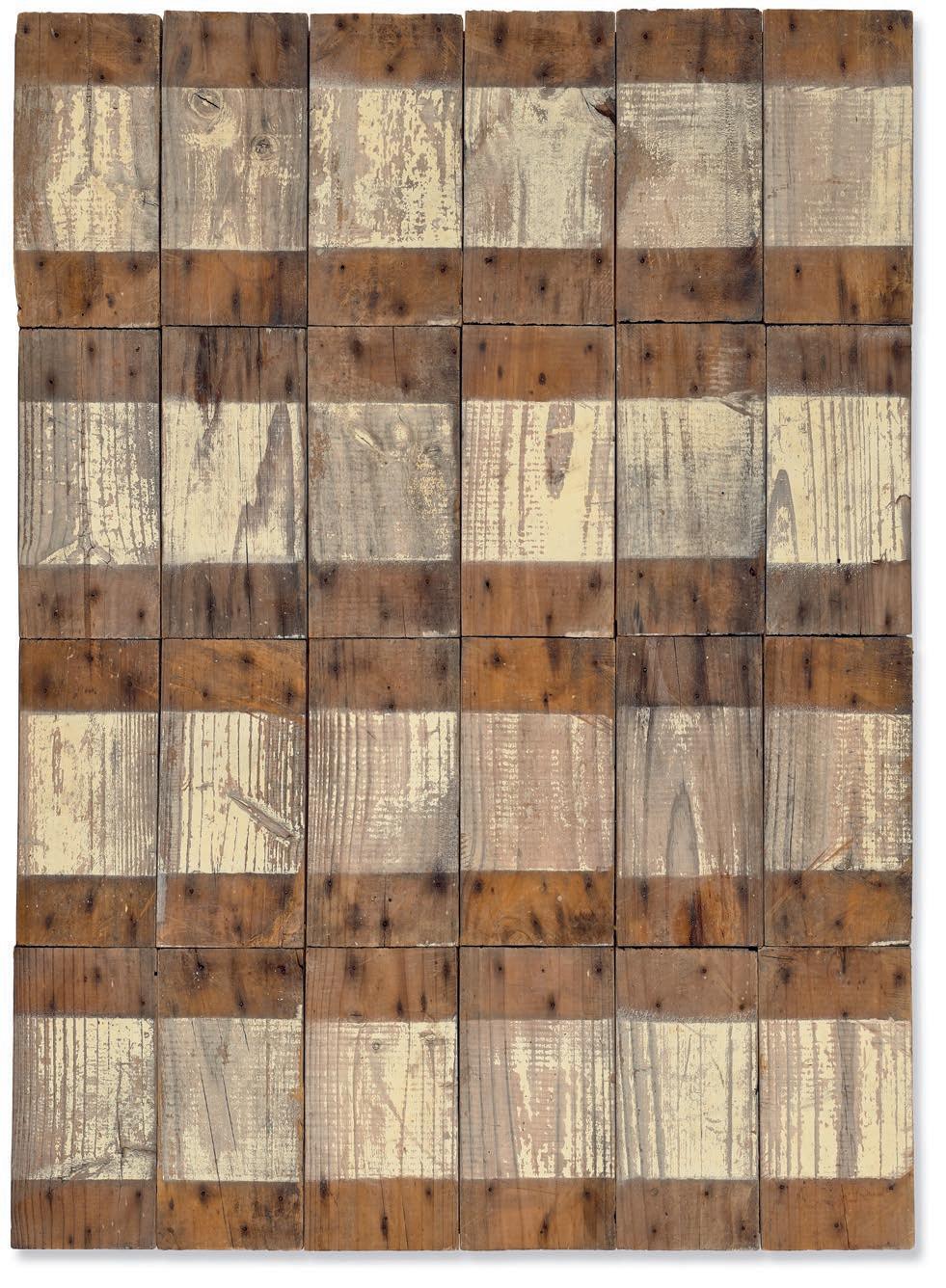

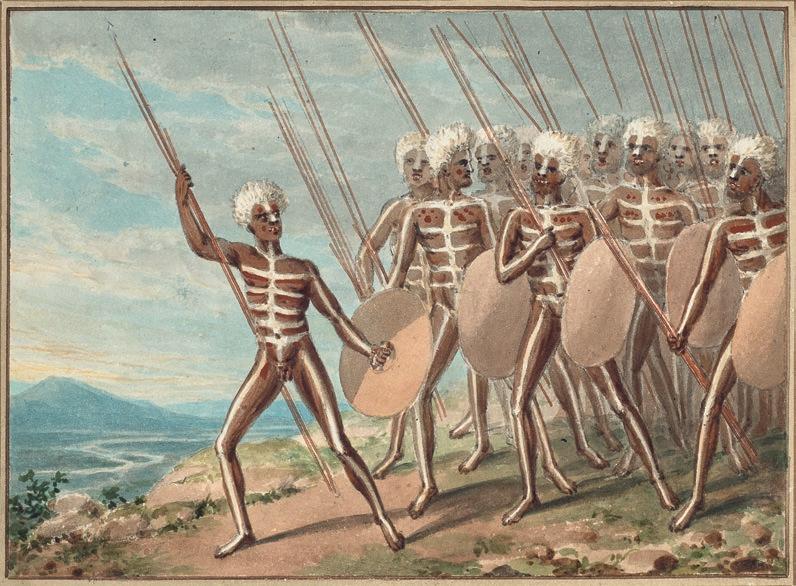

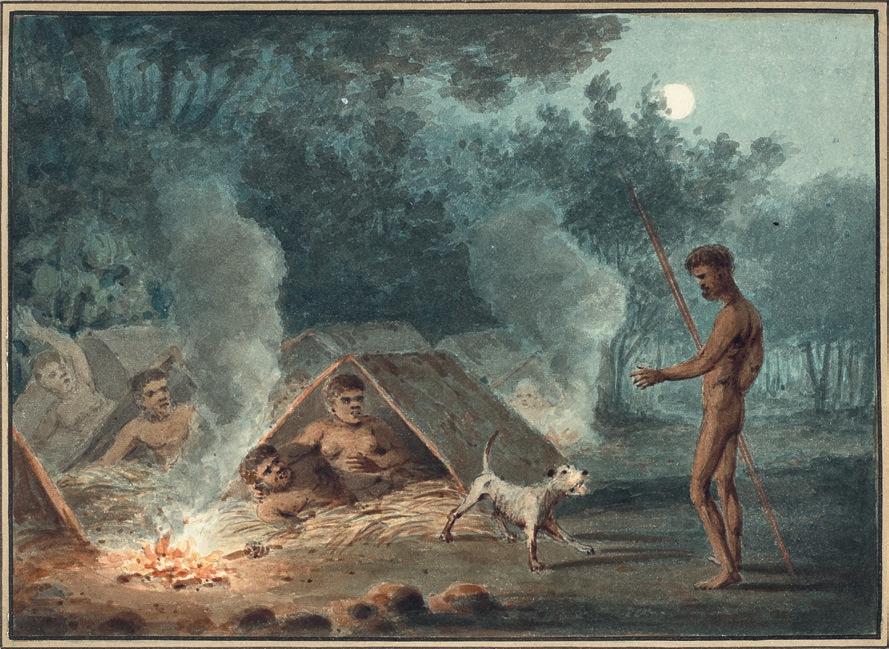

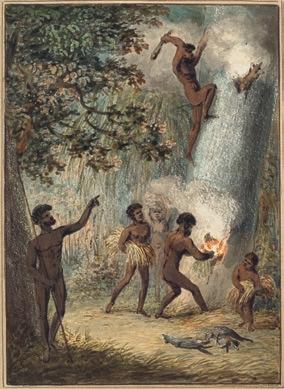

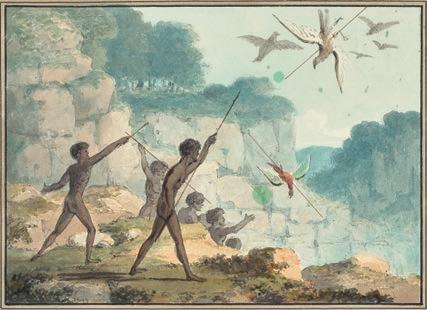

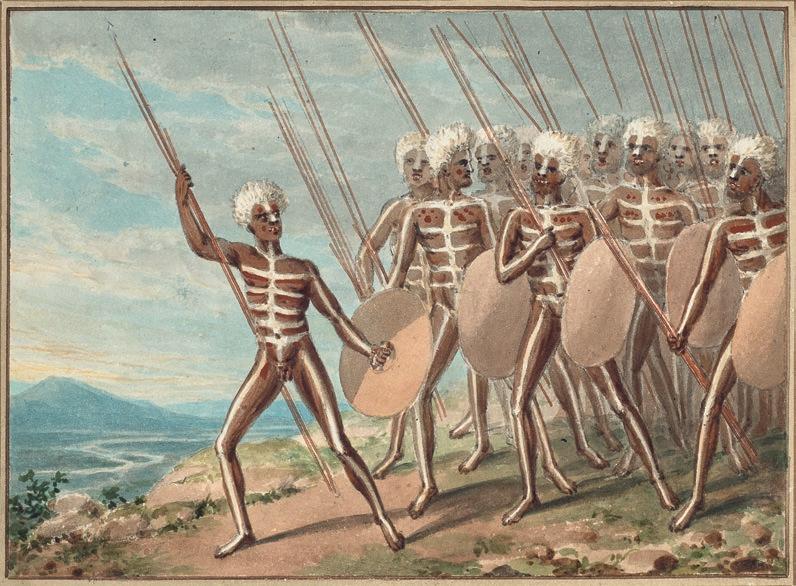

However, as so often since his army days in the Wimmera, Nolan’s narrative figuration is preceded by and fundamentally embedded in the dumb, haptic experience of landscape. From further travels, in northern Queensland, Nolan began in May with a sequence of pictures of the Gulf Country around Normanton, including (inter alia ) Windy Plain , 1948 (University of Western Australia); Carron Plains , 1948 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), and Blackboys , 1948 (private collection). The North Queensland dry sclerophyll landscape that occupies the bottom half of the present picture is as raw as it is rich; a desert plane of iron oxide red, ochre yellow, olive green and raw Masonite. Above the conventional-compositional-rule-breaking central horizon line is a flat, uninflected, cloudless, tropical dry season pale blue firmament, and where the sky meets the earth, Nolan describes the distant bush not by building up pigment over a flat ground, but by ‘cutting in’ around

suggestive tonal variations. This gives the foliage a tattered, fluttering, flag-like indeterminacy, suggestive of the shimmering, uncertain perception of a mirage, or of things seen at the edges of vision

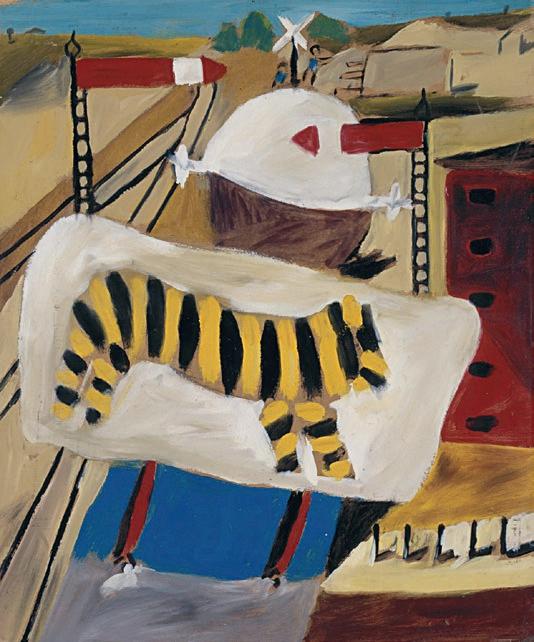

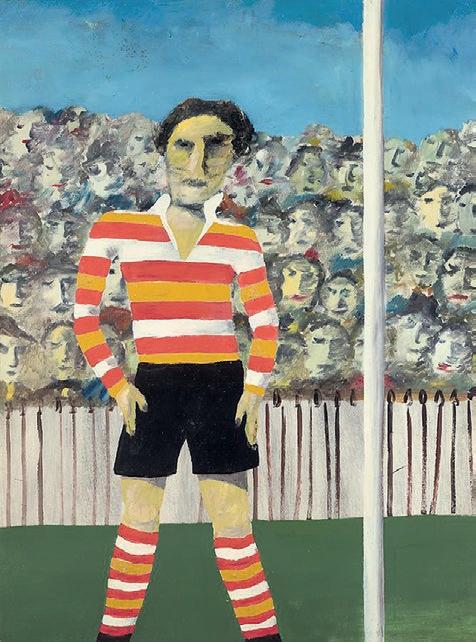

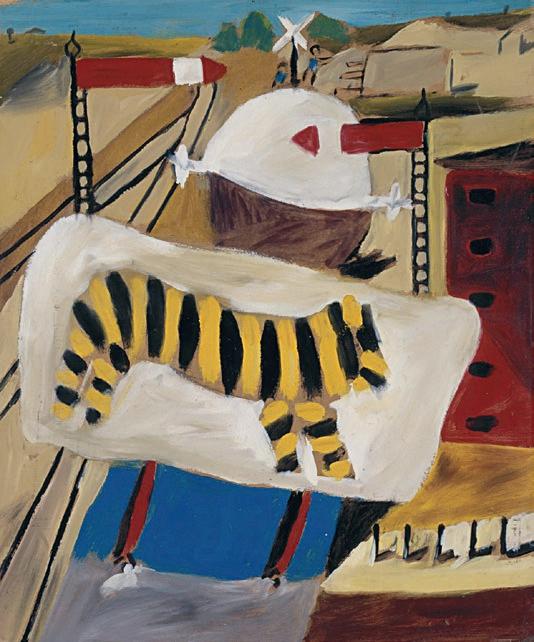

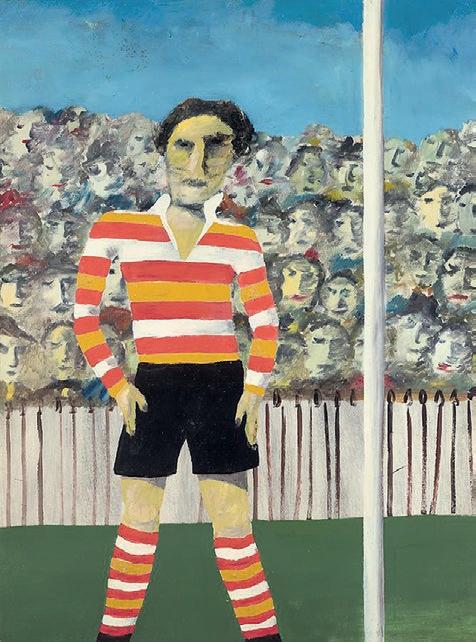

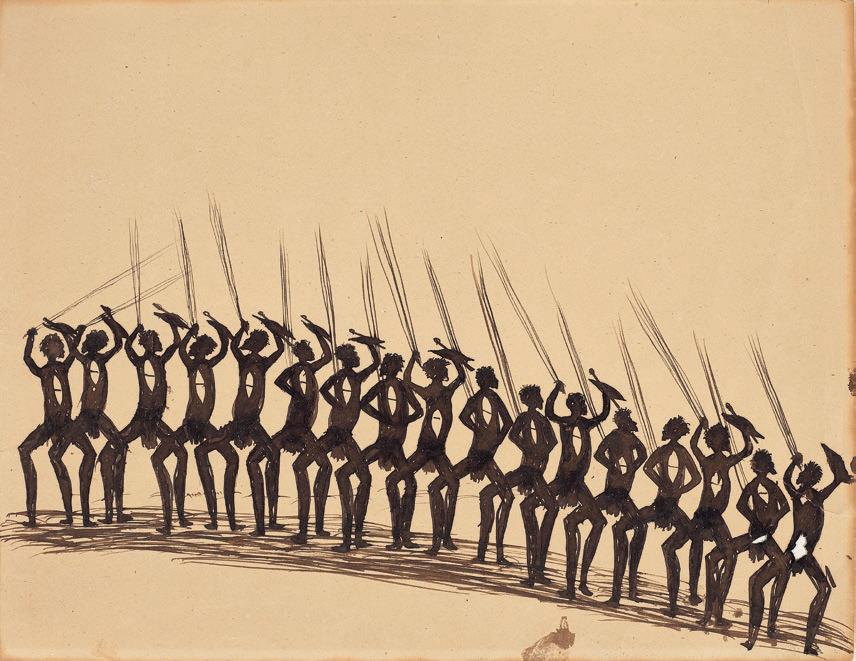

Then there is the prominent xanthorrhoea or grass tree, formerly commonly known to settler Australians as the ‘black boy’, a plant which produces black, spear-like ‘scapes’, rising from the crown of a green needle or pompom skirt at the top of its trunk. The foreground landscape in Escaped Convict is enlivened by detonations or compact cascades of these grass tree needles. The scapes which here pierce the empty sky flower in spring, or after fire, with white blossoms distributed spirally up the spike. Before the whole spike becomes sheathed in white, the emerging blooms can create a spotty, banded effect. For Nolan, this was honey; his precedent oeuvre is clotted with stripey incidents. There are heraldic bars in the early 1940 abstract monotypes, in the flags of Rimbaud Royalty, 1942 (Heide Museum of Modern Art); in the towel in Bathers , 1943 (Heide Museum of Modern Art); in the tiger stripes of the brand on the sack in Flour Lumper, 1943 (National Gallery of Victoria); in the football jumper of Footballer, 1946 (National Gallery of Victoria), and they recur in the drapery folds and columnar flutings of his designs for Sam Hughes’ Sydney University Dramatic Society production of Jean Cocteau’s Orph é e and Shakespeare’s Pericles later in the year. 2

39

And that is where the picture rested, until the addition of the inevitable mythic figure, Nolan’s ‘recurrent trope – the outsider set against an environment which resists occupation.’ 3 Building on the invented portraiture of his ‘colonial heads,’ a series painted towards the end of the Ned Kelly campaign of 1946-47, Nolan here drops an anonymous 19th century bearded head on top of a roughly-sketched zebra-striped convict figure. What Colin MacInnes calls the ‘skeletonic bars’4 of the prison uniform do not give us a body fully-modelled in space, but rather an abstract, a cypher, an almost-invisible man; as MacInnes puts it, ‘the figure is … insubstantial, almost like a vibration in the air, however palpable.’ 5 The background landscape can be perceived between the black and white bars, while the scape of the right-hand grass tree gives Bracefell both a spine and a hangman’s rope. Close examination even suggests some sort of continuity between the bands of Captain Fraser’s epaulettes in Death of Captain Fraser, and the striations of the convict uniform, and between the xanthorrhoea scapes and the Aboriginal spears that pierce Fraser’s body.

In Nolan’s desk diary for 24 March 1952 there is a rare, candid selfexploration, ‘one of [his] longest philosophical self-discussions.’ 6 Responding to Eric Bentley’s book The Cult of the Superman , and considering Ned Kelly, Burke and Wills and David Bracefell, the artist

admits that ‘the question is still open but apparently I am trying to formulate some conception of a colonial hero.’ 7 This key question would remain open for the rest of Nolan’s career.

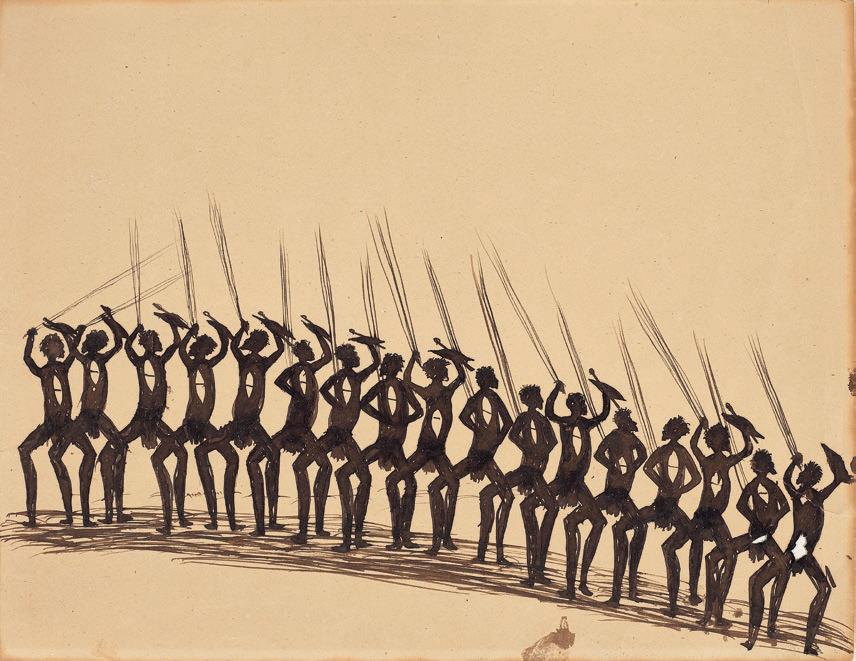

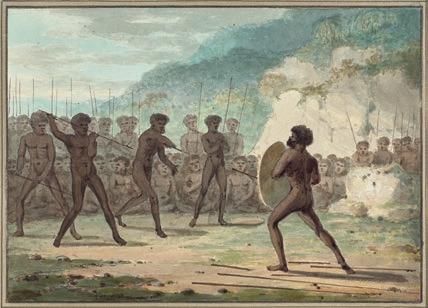

Another, more subliminal aspect of this work also bears mention: its relationship to First Nations culture.

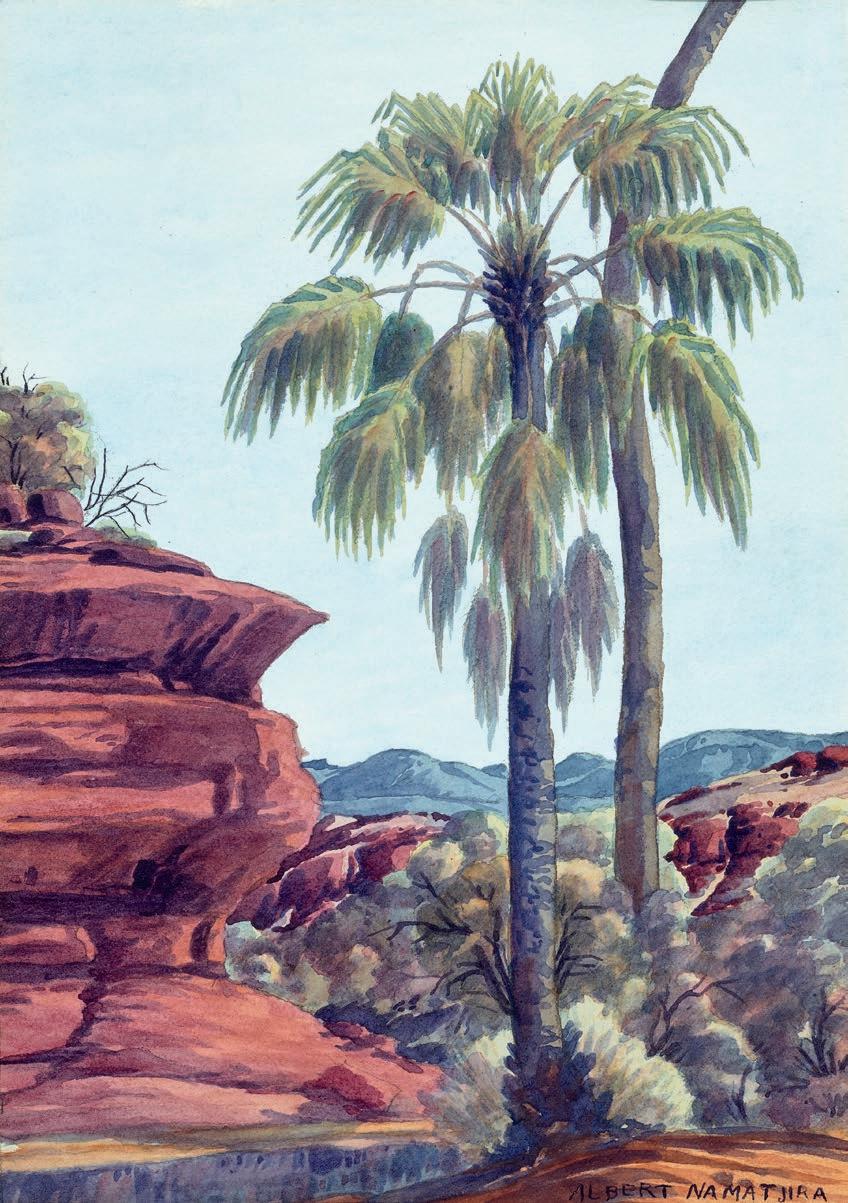

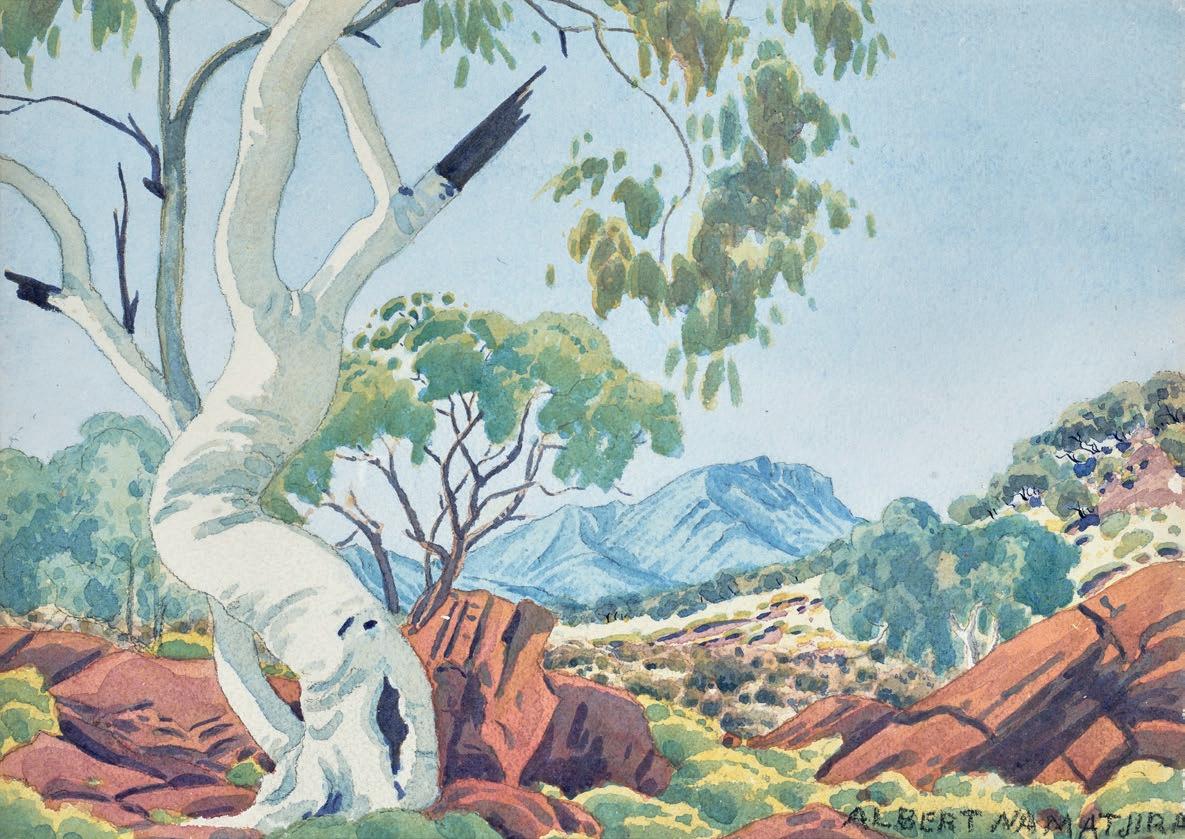

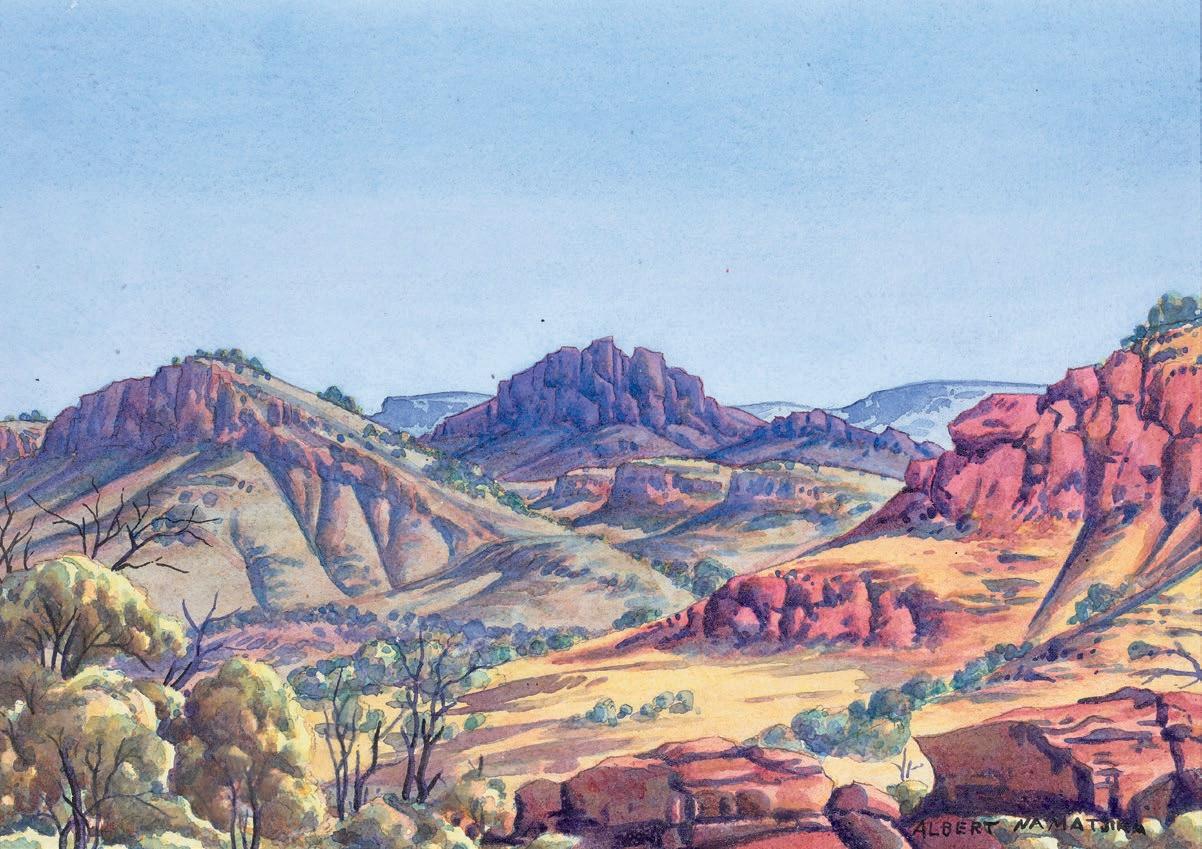

As Jane Clark observed in discussing Blackboys , ‘the trunks of the … grass trees are marked … like dreamtime Aboriginal warriors painted for a corroboree,’ 8 and it is interesting to note that the year after this work was painted, Nolan was quoted in the Telegraph as saying: ‘I am of the opinion that the Australian aboriginal is probably the best artist in the world. Recently we toured Central Australia, and the aboriginal art amazed me. The aborigine has a wonderful, dreaming philosophy which all Australian artists should have.’ 9 Carron Plains was illustrated 30 years later in Elwyn Lynn’s Sidney Nolan’s Australia , and his quotation from the artist about this work runs: ‘I wanted to grasp the idea of dry winds blowing through the trees, with the blackboys being trees or perhaps native boys; it’s a lyrical fantasy.’10 Moreover, while it may be anachronistic, it is nevertheless stimulating to consider the stripes of the xanthorrhoea and of Bracefell’s convict uniform as somehow coincident with those of Central Desert painting of the 1990s

40

Sidney Nolan Flour lumper, Dimboola , 1943 enamel paint on cardboard

75.5 × 63.5 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

© The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust / DACS / Copyright Agency

and 2000s: Turkey Tolson Tjupurulla’s eye-candy Straightening Spears works, or the awelye body paint designs of Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Minnie Pwerle.

Nolan’s Mrs Fraser series would be reiterated in sequences from 1957 and 1962, but its powerful ‘fusion of symbolism and reality’11 was first exhibited at David Jones’ Art Gallery, Sydney in March 1949.12 The exhibition Queensland Outback Paintings included both Mrs Fraser pictures and individual rural historical fantasies such as Dog and Duck Hotel (1948, private collection), Huggard’s Store , 1948, (University of Western Australia), and Little Dog Mine , 1948, (Holmes à Court collection, Perth). In many ways this was the show that marked the beginning of Nolan’s national success, recognition which would be cemented in the following year’s Exhibition of Central Australian Landscapes.13 Hal Missingham purchased two pictures for the Art Gallery of New South Wales, while the Sun ’s reviewer, Harry Tatlock Miller, declared that the work ‘makes an amazing impact and leaves an indelible impression … I can remember no exhibition by a contemporary Australian artist which with such seemingly disarming innocence of eye and hand, reveals so much individuality of vision. He gives us the sensation of seeing and knowing our own country, both its landscape and its legend, for the first time.’14

faithful narration of the dreadful sufferings of the crew, and the cruel murder of Captain Fraser by the savages… George Vertue, London, 1838; Gibbings, R.,, John Graham: convict , J. M. Dent & Sons, London, 1937. There was also an extensive retelling in Russell, H., Genesis of Queensland , Sydney, 1888. Later in the 20th century, Nolan’s friend the novelist Patrick White would publish a fictionalised account – White, P., A fringe of leaves, Jonathan Cape, London, 1976 – its original dust jacket reproducing Nolan’s Mrs Fraser and convict, 1962 – 64. The tale continues to fascinate; a postcolonial, trans-media reading can be found in Schaffer, K., In the wake of first contact: the Eliza Fraser stories, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, while more recently, Larissa Behrendt provides a developed First Nations perspective in Behrendt, L., Finding Eliza: power and colonial storytelling , Queensland University Press, St Lucia, 2016.

2. There may be another source for the striped spear: the St Andrew’s cross spider. As is already known (from his celebrated borrowing of an aerial view of Longreach for the Ned Kelly series’ The watch tower, 1947 (National Gallery of Australia), Nolan was a consumer of the Australian Geographical Society’s popular post-war pictorial magazine Walkabout. A close-up image of this eastern Australian arachnid, its web decorated with a zig-zag ‘X’ known as the ‘stablimentum’, appeared in the 1 April 1948 edition of Walkabout , p. 27 (photograph: Norman Laird)): see https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-739044803/view?partId=nla.obj739070666#page/n28/mode/1up accessed June 2023. In this image, the creature’s striped tapered legs resonate strongly with Nolan’s grass tree scapes.

3. Seear, L., ‘A wave to memory: Sydney Nolan Mrs Fraser ’, in Ewington, J., and Seear, L., (eds.), Brought to light: Australian art, 1850 – 1965: from the Queensland Art Gallery collection , Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1998, p. 202

4. MacInnes, C., Sidney Nolan , Thames and Hudson, London, 1961, p. 22

5. ibid., p. 88

6. Nolan cited in Underhill, N. (ed.), Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words, Viking, Melbourne, 2007, p. 22

7. Nolan, cited ibid. See also Bentley, E., The Cult of the Superman: a study of the idea of heroism in Carlyle and Nietzsche, with notes on other hero-worshippers of modern times , Robert Hale Ltd., London, 1947.

8. Clark, J., Sidney Nolan: Landscapes and Legends, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, Sydney, 1987, p. 99

9. ‘Aborigines “best artists”’, Daily Telegraph , 17 December 1949, p. 5

10. Lynn, E. (ed.), Sidney Nolan’s Australia , Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, p. 82

11. Haefliger, P., ‘Masterpieces of modern Australian art’, Sydney Morning Herald ,

2 November 1949, p. 2

12. An earlier exhibition of twelve Fraser Island pictures was shown at the Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, in February 1948, but this show largely comprised landscapes. It was not well received by local critics, who described the work as ‘meanderings in pictorial experiment’ and ‘blatant extremism’ (‘“Shock tactics” shock’, Courier-Mail , 18 February 1948, p. 2)

13. Central Australian Landscapes , David Jones’ Art Gallery, Sydney, March – April 1950

14. Tatlock Miller, H., ‘Amazing impact by Australian artist’, The Sun , Sydney,

8 March 1949, p. 8

41

1. Curtis, J., Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle, containing a

DR DAVID HANSEN

enamel

on composition

121.9

91.4 cm National

of Victoria, Melbourne

/ DACS / Copyright Agency

Sidney Nolan Footballer, 1946

paint

board

×

Gallery

© The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust

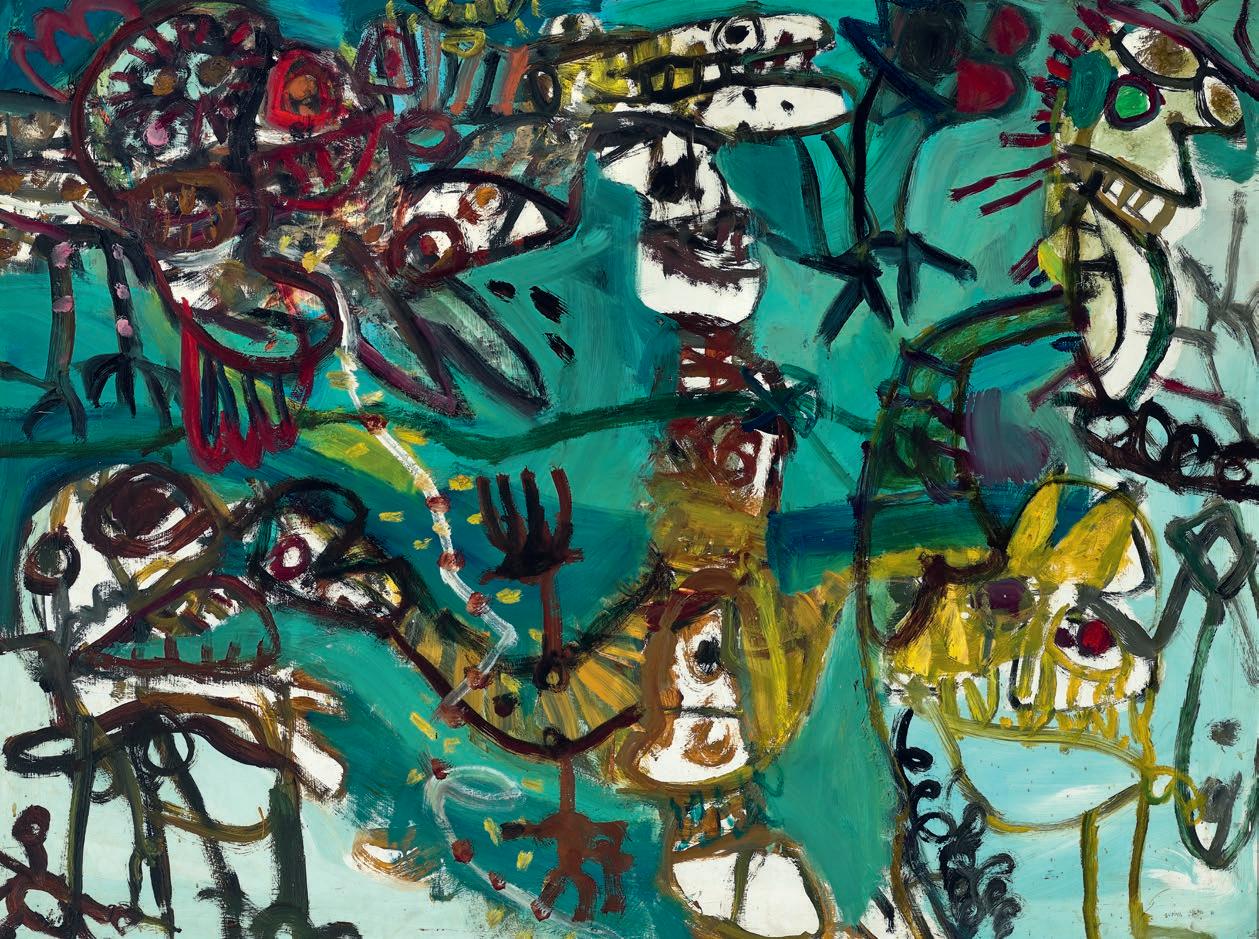

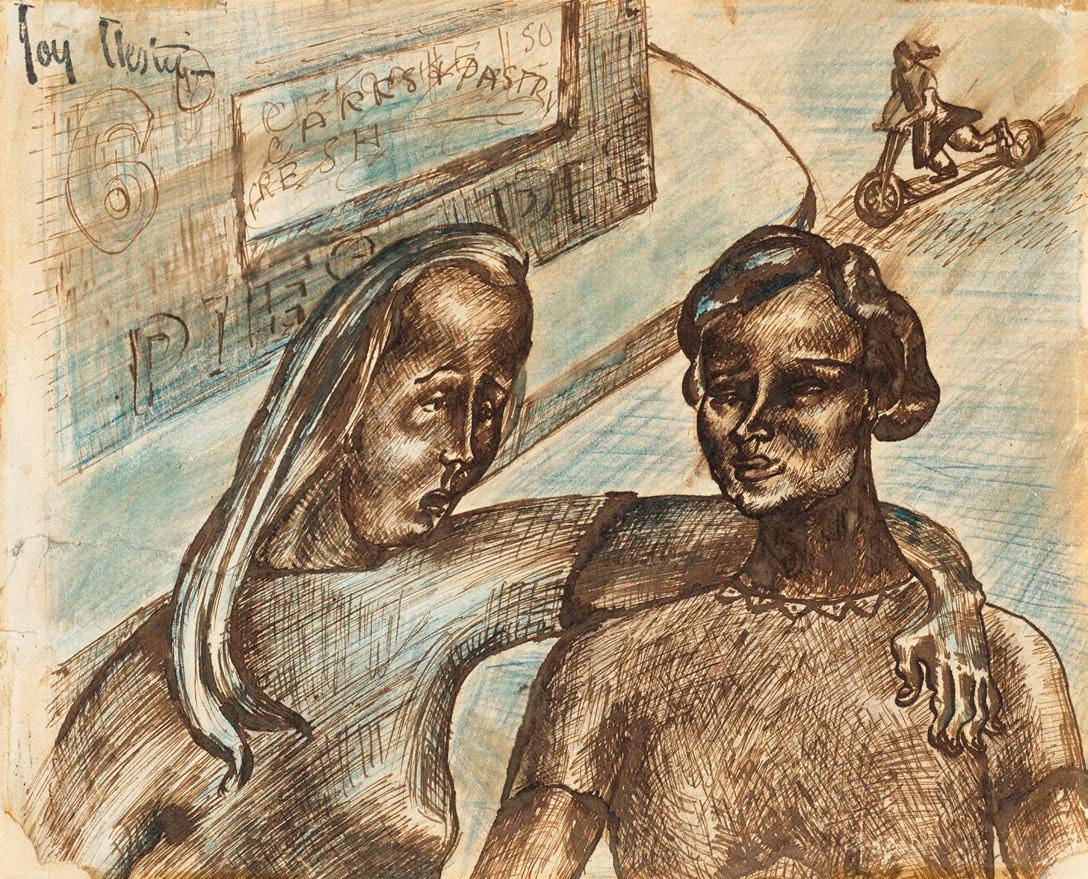

Important works from the KRONGOLD

Melbourne Lots 5 – 22

43 (detail ) SIDNEY NOLAN (1917 - 1992) EARLY MORNING TOWNSHIP, 1955

COLLECTION

44 COLLECTION OF HENRY KRONGOLD

HENRY KRONGOLD CBE AM (1909 – 2003)

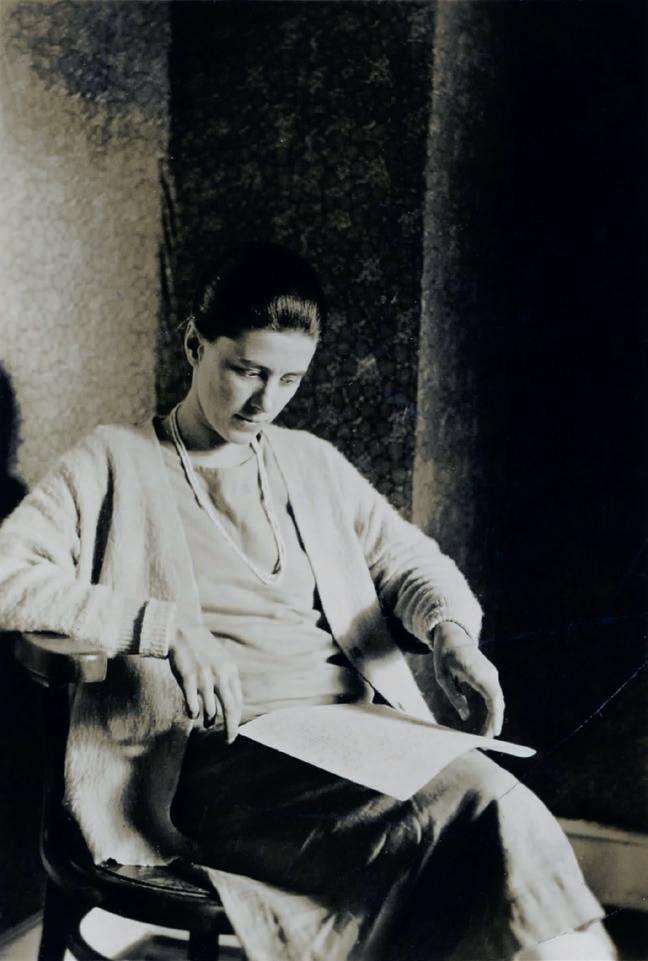

Born in Lodz Poland in 1909, Henry spent the first 3 decades of his life in Poland, across three cities within 120 kilometres of each other: Lodz, Warsaw, and Radom. By his thirtieth year, he was a bureaucrat working in an insurance office, but for a short period in 1927 had also studied painting at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts which nurtured in him the beginnings of what was to become a lifelong appreciation for art.

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Henry was plunged into the ordeal of war, soon worsened by the Nazi persecution of Jews. As the Germans swiftly swept aside the Polish front-line armies (in which Henry was fighting), he had no choice but to abandon all that was dear to him and frantically flee his homeland to avoid being captured as a prisoner of war. Thus, the next 18 months were spent escaping from the ravages of war – an epic, death-defying journey across Europe which saw him travel to Vladivostok and then Japan, before arriving in Melbourne on 27 June 1941.

In his early life in Australia, Henry worked as a manual labourer in the textile industry, learning English from fellow factory workers and through reading the poetry of Lord Byron. Shortly after settling in Australia, he met his future wife-to-be, Dinah, at the Café Lopata in Barkly Street, St Kilda; Dinah was born in Lomza, Poland, and had arrived in Australia with her parents some years earlier. The following year, the couple married on 12 December 1942 and would go on to share three sons together, Ronald, Dennis, and Paul. Throughout their life together, Henry and Dinah remained a loving devoted couple, with Dinah not only fully supporting Henry in all his business ventures and community duties, but also playing an active role in their many varied philanthropic pursuits which greatly enriched education, the arts, and numerous charitable causes.

Naturalised as an Australian citizen in 1947, Henry saw little prospect continuing as a manual labourer and thus, equipped with a vision, keen determination, and a sense of enterprise, he embarked upon the path to launching himself as one of the country’s most successful businessmen and entrepreneurs. From his first venture in 1946 when he and his brother Elek established an Iron Foundry, he subsequently became involved with larger businesses that ranged from importing textile machinery and retail lingerie to textile weaving, fabric wholesaling, and obtaining the Australian and New Zealand franchise to manufacture Schiaparelli hosiery at his Melbourne Charmaine Hosiery factory.

Significantly, in 1959 – 60 Henry joined a syndicate to establish Australian Wool Industries Ltd which involved constructing a plant for processing Australian greasy wool at Ashdod on Israel’s Mediterranean coast as a deliberate attempt to assist both Australia and Israel through exports and employment. During this period, Henry was also very involved in community affairs in his various roles on the Board of Governors of Mt Scopus College from 1958 to 1968 and the Victorian United Israel Appeal (as President from 1963 – 69, and Federal President from 1969 – 73). In later years, propelled by thoughts of lost business opportunities, life’s frailties and an awareness of his growing family and grandchildren now appearing, Henry turned his attention from

45

primarily Jewish fun draising activities to much larger commercial enterprises, including land development at Keilor (on the outskirts of Melbourne) and the Gold Coast, Queensland, together with the acquisition of major properties within the Melbourne CBD , and the acquisition of the iconic Mitchell House on the corner of Elizabeth and Lonsdale streets. In 1976, Henry also took full ownership and control of Capital Carpet Industries Pty Ltd, a large carpet manufacturer producing a significant share of Australia’s total carpet output.

Similarly, during these years, Henry’s charitable energy expanded from a primary focus within the Jewish community to a much broader, state-wide reach, as he and Dinah came to be recognised among the country’s most major philanthropists, particularly in the arts and education sectors. In 1972, Henry and Dinah made a very generous donation to Monash University for the construction of a new learning centre, built over four years, which was then known as The Dinah and Henry Krongold Centre for Exceptional Children. Subsequently, the building has transformed to become Monash Krongold Clinic, Krongold Services for Children and Krongold Research Programs. Henry and Dinah were also major sponsors to many charities, including the Epworth Medical Foundation; Cabrini Hospital; Scotch College Foundation; Mount Scopus College; The Victorian State Opera; United Israel Appeal, and Tel Aviv University.

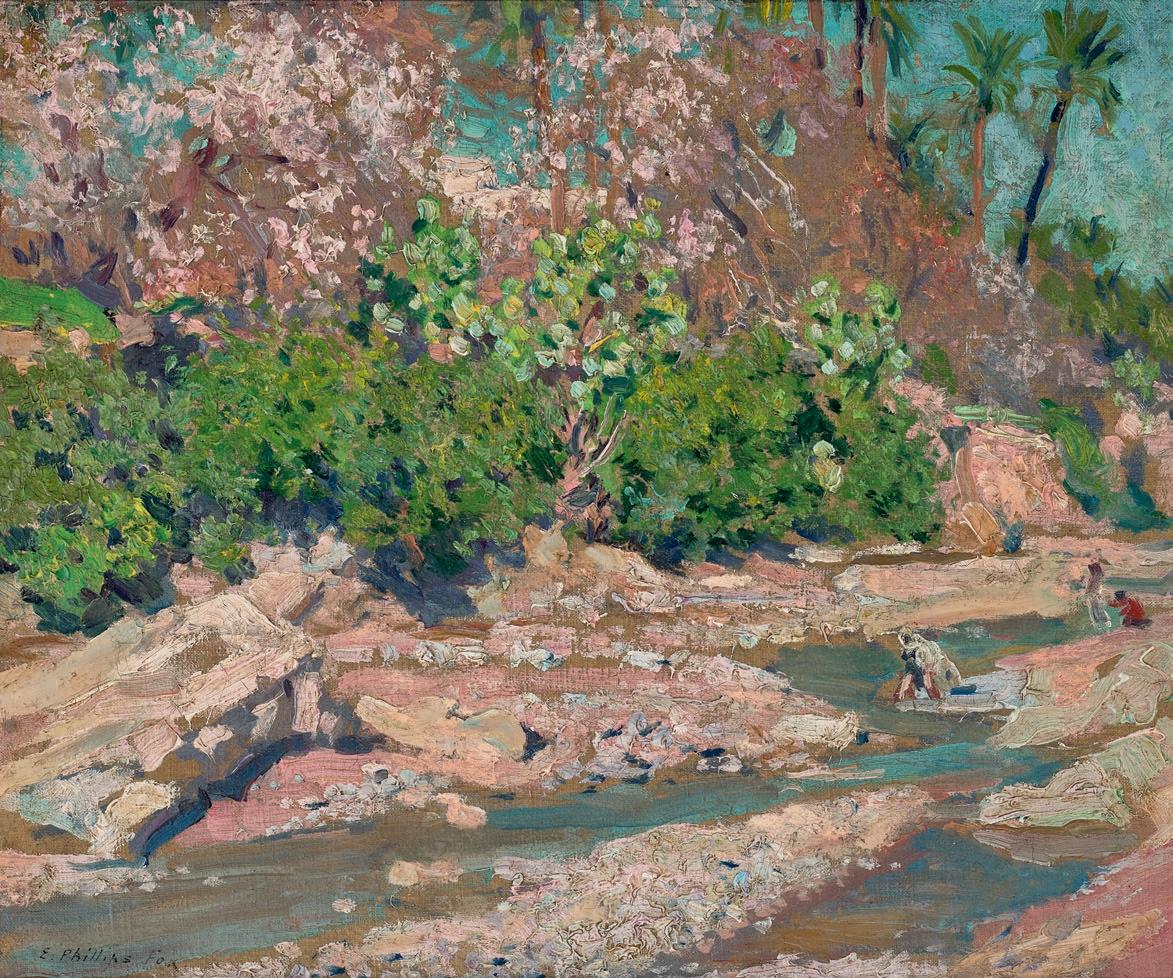

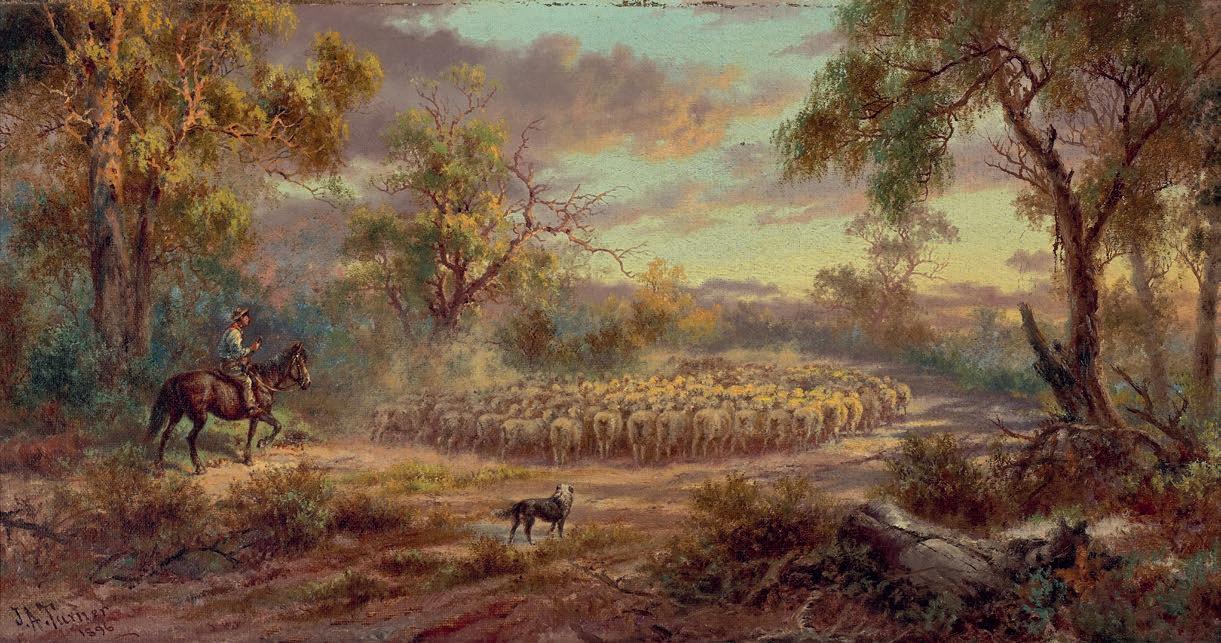

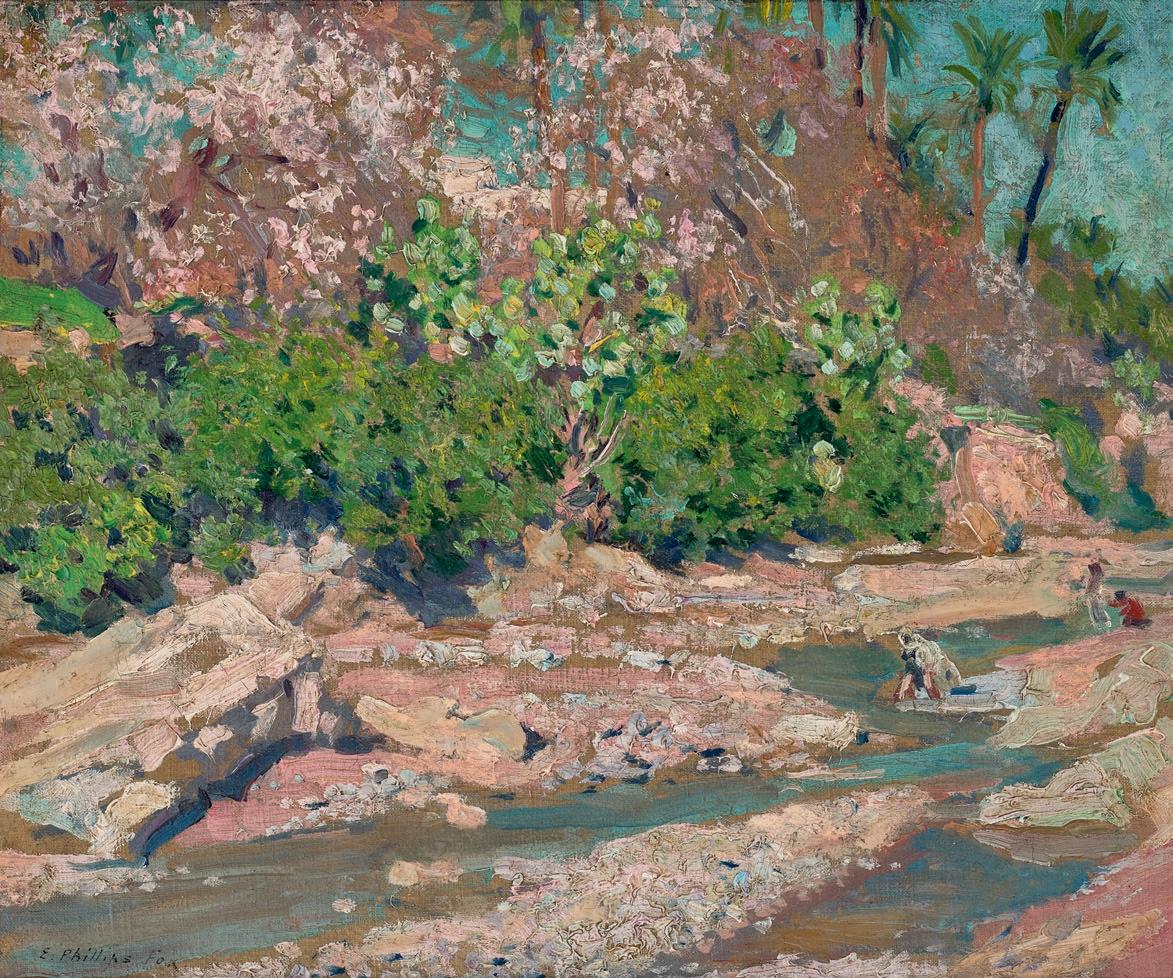

As his businesses flourished, Henry found more time to travel overseas where he and Dinah enjoyed many wonderful memories visiting art galleries and museums. The experience reignited Henry’s lifelong (but largely dormant) passion for art and thus, in 1976 the couple embarked upon creating their own collection of both European and Australian art. Initial acquisitions included a sensuous odalisque, Day Dreams by Tudor St George Tucker; Danila Vassilieff’s Street Scene, 1936; a pretty little McCubbin and the luminous Figures Beside the Creek, Stanwell Park , c.1914, by Australian impressionist painter, Emanuel Phillips Fox. Although very knowledgeable about European artists, in the early years Henry felt less conversant with Australian art and thus, enlisted the services of astute Melbourne art dealer, Dr Joseph Brown, to provide guidance and bid at auction on his behalf. Although Henry was not prepared to give Dr Brown carte blanche. There were a handful of occasions where he advised Dr Brown to ‘Go for your life!’ One such work was Sidney Nolan’s masterpiece from the Kelly series, Early Morning Township , 1955, which Henry felt he absolutely should have represented in his collection and accordingly he instructed Dr Brown to ‘Bid and be the last bidder!’

The same year as Henry began building his personal collection of art, he was also invited by Sir Rupert Hamer to join the board of the Art Foundation of Victoria Endowment Trust, established to assist the National Gallery of Victoria which was struggling at the time to compete in an art market of steeply rising prices exacerbated by inflation. During his tenure as Chairman from 1979 – 80, Henry negotiated and financed, with Dinah, the acquisition of Rupert Bunny’s magnificent portrait of Dame Nellie Melba by the Trust for the National Gallery of Victoria, together with two works by Rococo artist François Boucher, and a collection of over seventy works on paper by the greats of American art during the sixties and seventies.

46

COLLECTION OF HENRY KRONGOLD

During his lifetime Henry, was the recipient of many awards and honours in recognition of both his active community life and generous philanthropy. In 1978, he was appointed a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) ‘for outstanding service to the community and in particular to the Arts, young people and industry’, and in 1991, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from Monash University and became a Doctor of Humanities in Peace from the Albert Einstein International Academy Foundation for his peace-keeping work in Israel. While in 2002, he received a Doctor Philosophy Honoris Causa from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the same year was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM).

He is greatly honoured and respected by all who knew him.

SIDNEY HACK

47

Henry Krongold, Sir Gustav Nossal and the Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, on 27 October 1980 photographer: Terry Forrester

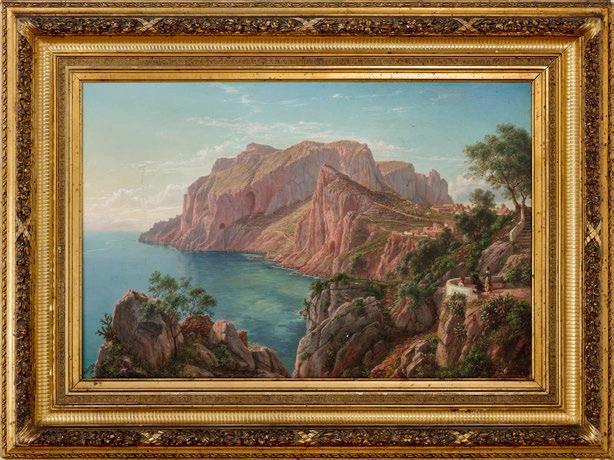

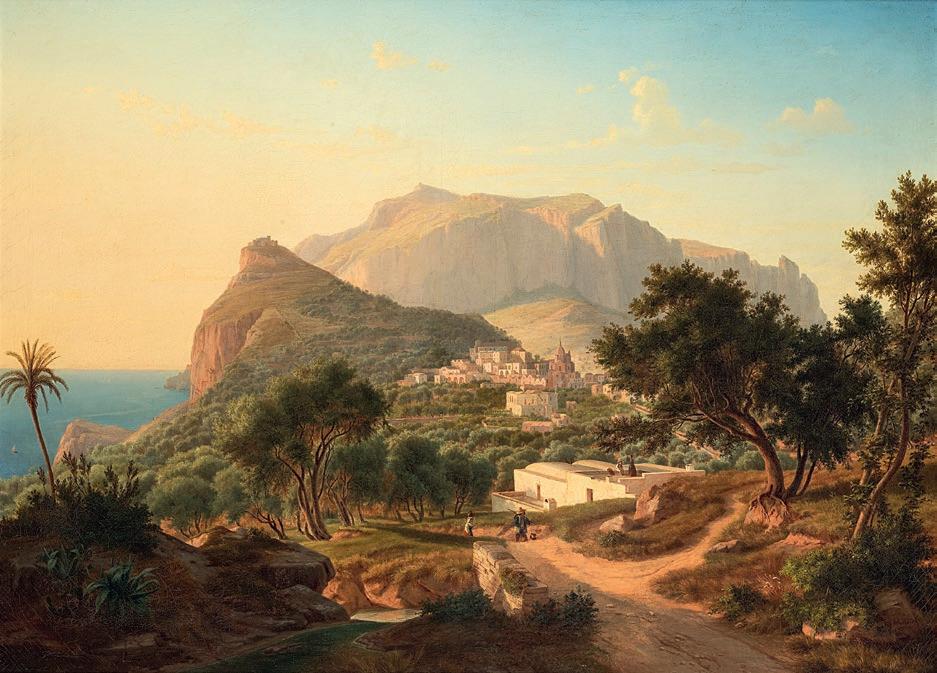

5 EUGENE VON GUÉRARD

(1811 – 1901)

VIEW OF CAPRI NEAR NAPLES, 1883 oil on canvas

48.0 x 72.0 cm

signed lower right: E. v. Guérard

inscribed on stretcher bar verso: View of Capri taken from the Punta di Tragara

ESTIMATE: $120,000 – 180,000

PROVENANCE

Fletcher’s Art Gallery, Melbourne

Thomas Shaw, Wooriwyrite, Victoria, acquired from the above in 1884

Thence by descent

Private collection

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 17 April 1989, lot 382

Henry Krongold, Melbourne

The Estate of Paul Krongold, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

Victoria Jubilee Exhibition, Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne, November 1884 – January 1885, cat. 185, lent by Thomas Shaw

Eugen von Guérard, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 7 June – 13 July 1980 and touring; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, August 1980; Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria, September – October 1980; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, November 1980 and National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, December 1980 – January 1981

LITERATURE

Letter von Guerard to James Smith, 28 May 1883, James Smith

Papers, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Letter von Guerard to James Smith, 24 May 1884, James Smith

Papers, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

Bruce, C., Eugen von Guérard , Australian National Gallery & Director’s Council, Canberra, 1980, p. 118 (illus.)

Bruce, C., Comstock, E., and McDonald, F., Eugene von Guérard: A German Romantic in the Antipodes , Alister

Taylor, Sydney, 1982, pl. 47, p. 162

RELATED WORKS

Capri 12 März 82 , pen and ink over pencil, Sketchbook XXXX, 1882, 1891, in the collection of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, DGB16 v. 17: 10

Sketchbook VI, 1835 & 1836, Capri, in the collection of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney DGB14, vol. 8.

Capri , pencil, 1 May 1838

Capri , pencil, 2 May 1838

Abendlandschaft von der Insel Capri , 1846, oil on canvas, 75.0 x 103.5 cm, private collection

View from the ruins of the Villa di Tiberio looking across to Punto di Campanella and Monte Solaro / View from the western part of the island of Capri from the temple of Tiberius , 1885, oil on canvas

Capri: A view of Marina Piccola with Point Faraglione in the distance , 1884/1885, oil on canvas

48

COLLECTION

OF HENRY KRONGOLD

49

Eugene von Guérard

Capri 12 March 1882.

Page 10 in Volume 17: Sketchbook XXXX, 1882, 1891 State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

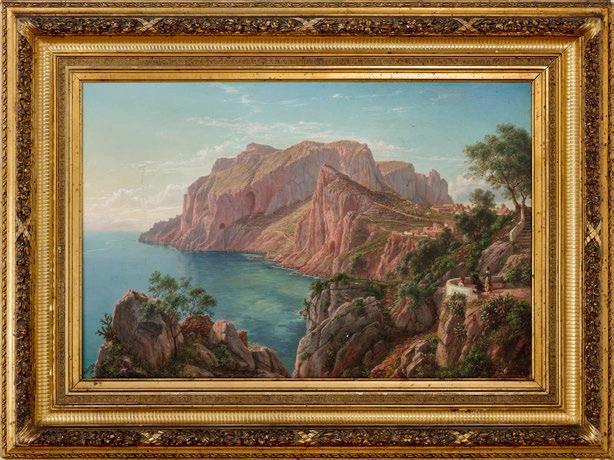

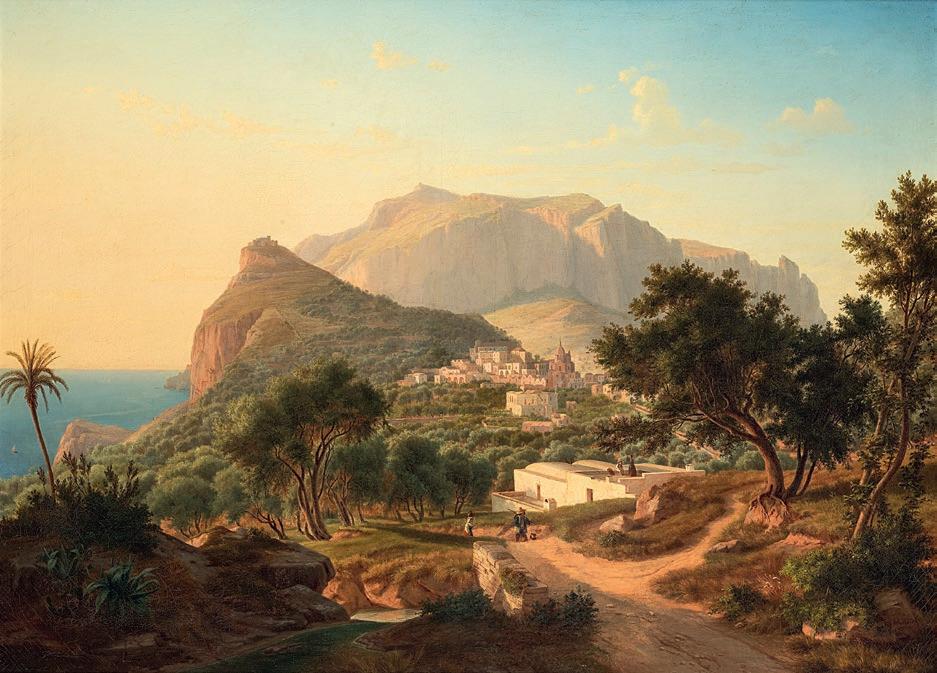

Eugene von Guérard, one of Australia’s greatest landscape painters, was captivated by the light and rugged beauty of the fabled island of Capri. He longed to share the magic of the place he had known so well in his youth with his wife Louise and their daughter Victoria and, on 26 February 1882, the von Guérard family sailed into the Bay of Naples in the ‘most magnificent sunshine’ and on a sea ‘as flat as spilt oil.’1 They stayed at the ‘new Hotel du Vesuve’ (the now legendary Grand Hotel Vesuvio) which, ‘although dearer is in a very beautiful position at Castel del Ovo.’ 2 It was not far from the Strada Piliero where von Guérard and his artist-father Bernard had lived in the mid-1830s. Von Guérard, Louise and Victoria spent almost a month in Naples visiting the ‘sights of the city and surroundings most worth seeing’ – including the mesmerisingly beautiful island of Capri, a place steeped in history and richly interwoven with literary and artistic associations. 3 On 12 March 1882, as they explored the island, von Guérard sketched the view from close to the vantage point of the present work. View of Capri near Naples , 1883 was painted the following year in his studio in Düsseldorf.

Von Guérard had first visited the island with his father in the summer of 1835. The ever-growing stream of northern painters and writers drawn to the island in the early nineteenth century included von Guérard’s associate, the influential Arnhem-born School of Posillipo painter, Anton

Sminck Pitloo. The young artist would also have been well aware of August Kopisch’s famed discovery of the Blue Grotto in 1826, and of the visits made by German and Scandinavian artists such as Ernst Fries, Leo von Klenze, Johann Christian Dahl, Franz Catel and Carl Morgenstern – all of whom were captivated by the light, intense colour and natural beauty of Capri. In May 1838, just before he left Naples for Düsseldorf to study at its famous Academy, von Guérard made a farewell visit to Capri. The luminous Abendlandschaft von der Insel Capri (Evening Landscape on the island of Capri) of 1846 – a work that attracted strong interest when it was presented by Deutscher and Hackett on 15 July 2020 – was based on two finely detailed, light and spacious drawings that date from the 1838 visit.

View of Capri near Naples portrays the same stretch of coastline as that in the 1846 painting – the view looking towards Monte Solaro and Anacapri from Capri. For the present composition, however, von Guérard positioned himself closer to the coast and further around and along the Marina Piccola. From this vantage point, on the Punta di Tragara, he could look directly across the water to the dramatic cliff formations that are the subject of the painting. Here the abstract forms of the island’s complex topography and the irregular surfaces of the spectacularly

50

COLLECTION OF HENRY KRONGOLD

Eugene von Guérard

Abendlandschaft von der Insel Capri , 1846 oil on canvas

75.0 x 103.5 cm

Private collection

eroded dolomite and limestone cliffs are emphasised by the contrasts between light and the shadow cast by the low rays of the setting sun.

Von Guérard’s lifetime fascination with – and knowledge of – geology is evident in his depiction of the worn limestone with its surface layers of volcanic ash and tufa, the exposed outcrops of rock along the ridgelines and the caverns eroded by rain and the action of the sea.

This stretch of the Capri coastline was already one of the most famous views on the island: here we share the experience of being there with a small party of tourists relaxing on the belvedere in the foreground on the right. Further along, the fourteenth century Carthusian Monastery, Certosa, sits at the top of a steep coastal cliff, and beyond it, famous landmarks of the township of Capri can be identified, notably the domed seventeenth-century church of San Stefano. Von Guérard knew the architecture and layout of the township of Capri well, having recorded it with minute precision in 1838: we are invited to take a virtual stroll into the town, or to share the awe of the tiny figures on the grassy ledge below the monastery as they take in the magnitude of the soaring rock walls bathed in the pink, almost crepuscular, light of a sunset slipping into evening. These minute and lively observations are integrated into a work of uplifting breadth, one based on strong compositional geometry and unified by light.

View of Capri near Naples was one of nine works that, in 1884, von Guérard sent to Melbourne to be sold by the successful Collins Street art dealer Alexander Fletcher. It quickly found a buyer in Thomas Shaw, whose Western District pastoral property, ‘Wooriwyrite’ near Camperdown, von Guérard had first visited and sketched in 1857. View of Capri near Naples was shown at the 1884 Victorian Jubilee Exhibition, on loan from Shaw.

Von Guérard remained captivated by the subject of Capri: he painted Capri: A view of Marina Piccola with Point Faraglione in the distance in late in 1884 or early 1885, and the beautiful, light-infused View from the ruins of the Villa di Tiberio looking across to Punto di Campanella and Monte Solaro in 1885.

3.

51

1. Von Guérard to Julius von Haast 14 April 1884. Haast Family Papers, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, in Darragh, T., & Pullin, R., Lieber Freund! Letters from Eugen von Guérard to Julius von Haast , Art Gallery of Ballarat, Ballarat, 2018, p. 56.

2. ibid.

ibid.

DR RUTH PULLIN

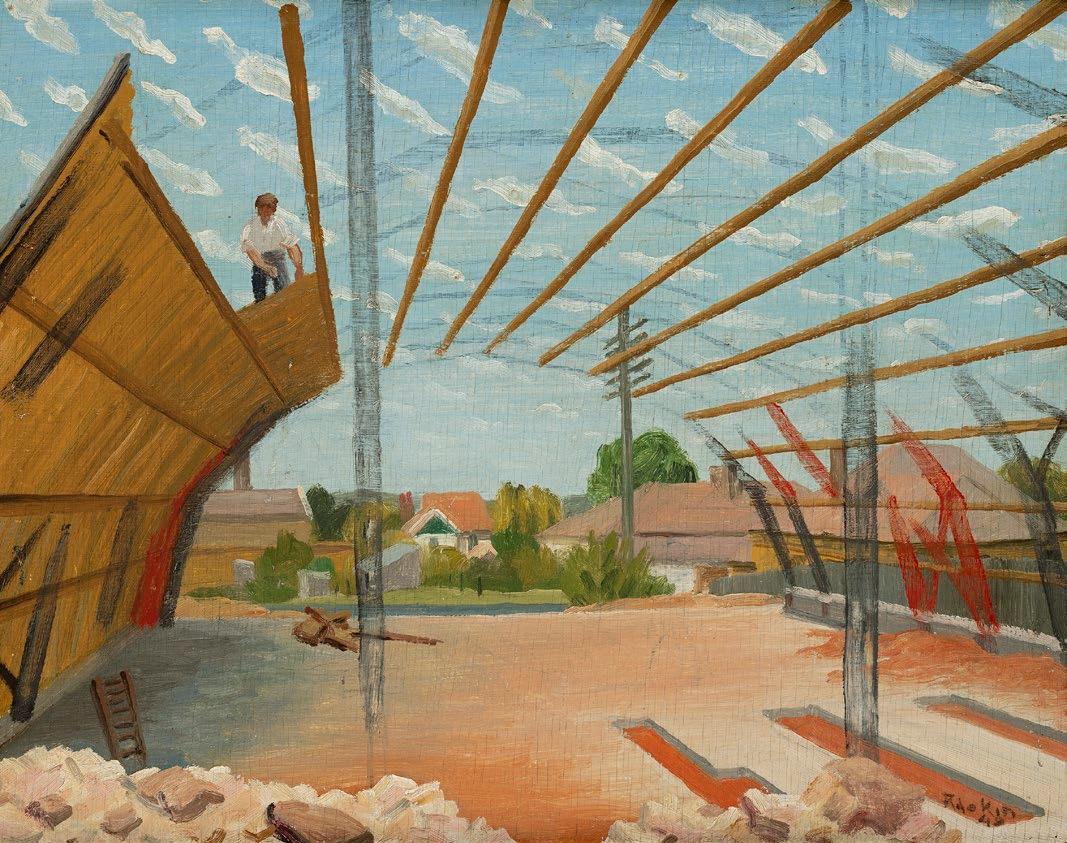

6 ARTHUR STREETON

(1867 – 1943)

ROUEN, FROM BON SECOURS, 1912

oil on canvas

51.0 x 77.0 cm

signed lower right: A. Streeton bears inscription on plaque attached to frame: Sir Arthur Streeton / “ROUEN, FROM BON SECOURS” / (c.1912)

ESTIMATE: $120,000 – 180,000

PROVENANCE

Sir Edward Hayward, Adelaide, by 1968

Private collection, Melbourne

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 19 August 1996, lot 147

Henry Krongold, Melbourne

The Estate of Paul Krongold, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

Arthur Streeton Exhibition , John Martin & Co. Ltd, Adelaide Festival of Arts, Adelaide, 6 – 23 March 1968, cat. 79 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Streeton, A., The Arthur Streeton Catalogue , Melbourne, 1935, cat. 482 or 483

RELATED WORKS

Rouen , 1912, watercolour on paper, 23.5 x 34.5 cm, private collection

Rouen , 1912, illus. in Ure Smith, S., The Art of Arthur Streeton , Special Number of Art in Australia, Angus & Robertson, Melbourne, 1919, pl. XXXIX

52

COLLECTION OF HENRY KRONGOLD

53

Boulogne , 1918

oil on canvas

91.8 x 153.0 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Arthur Streeton left Australia in January 1897, bound for London and eager to see the works of the great masters of European art, as well as those of his contemporary international peers. Writing to his friend Tom Roberts the following year, he declared, ‘[John Singer] Sargent is a perfect wonder … & 2 or 3 … are quite as fine as the great Rembrandt.’1 In a postscript to the letter, he wrote:

I feel convinced that my work hereafter will contain a larger idea & quality than before – After seeing Constable Turner Titian Watts & all the masters – I wish you & the Prof [Frederick McCubbin] could have a trip here – I think it’s necessary for ones work – I’m evolving & should I return I’d never paint Australia in exactly the same way – by Gad I’ll do one or two great things if I get out there again – I know more now - & would touch it more poetically 2