baby

WORDS ELIZABETH QUINN + CARRIE STEINGRUBER

Stop the Bleeding

i

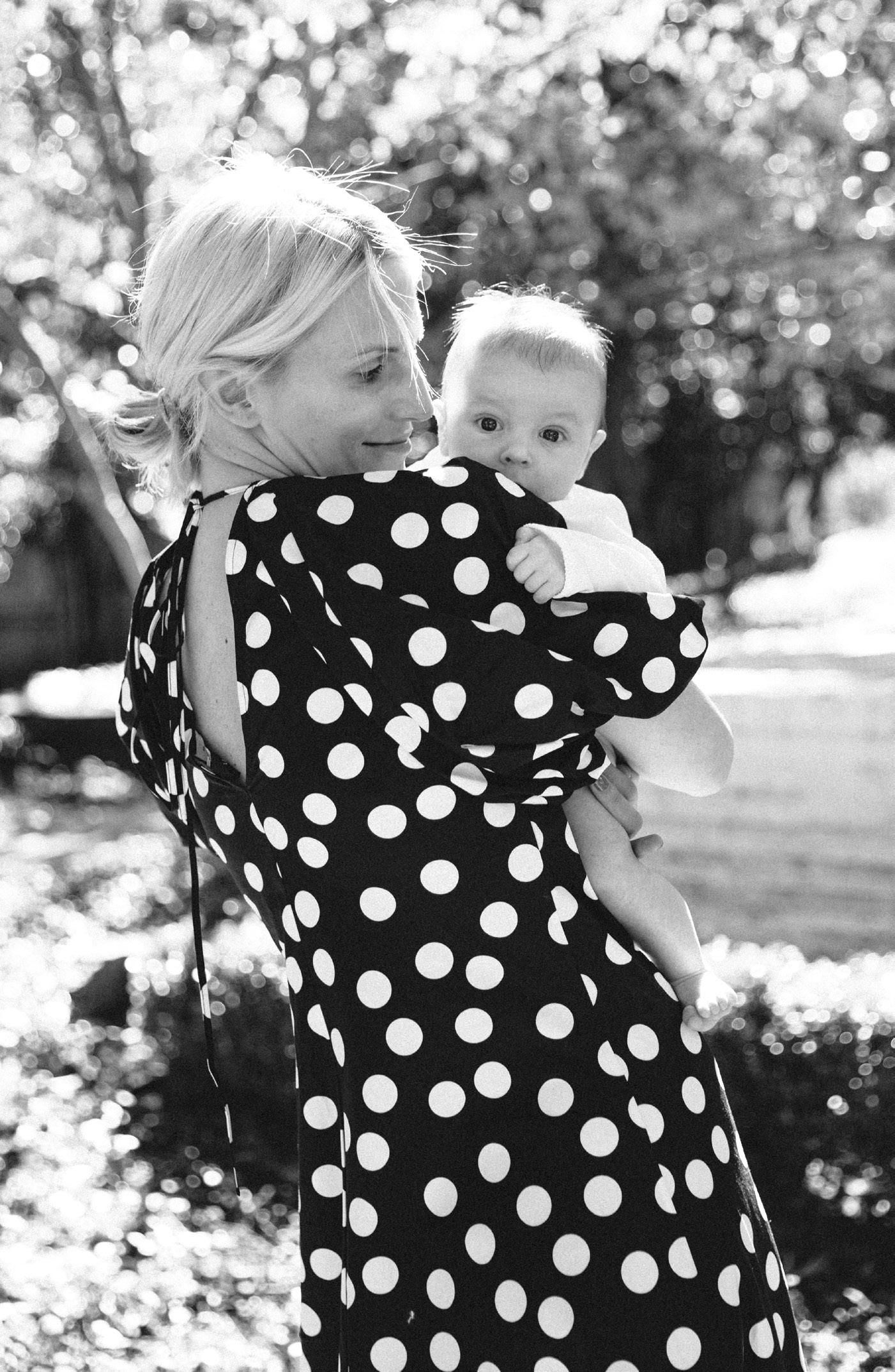

t was exactly one week after Kristen Kimmel’s healthy baby Kate was born. The in-laws were over; her husband, Tom Mathews, was making lunch. Earlier in the week, she had even taken the dogs for walks. Everything was fine. As Kimmel sat down to breastfeed her daughter, she felt some unusual cramping.

“They tell you that as your uterus continues to shrink, that [cramping] is normal, especially if you breastfeed,” says Kimmel, who lives in Dallas. So she didn’t think much of it. When she went to the bathroom, she noticed some clots in her pad—again, it’s normal to have spotting after giving birth … but there shouldn’t be large clots, and you shouldn’t go through pads quickly. As a safety precaution, Kimmel called her OBGYN, who told her to watch the bleeding and call back if it worsened. It did. Kimmel says within 20 minutes, she began feeling heavy and ran to the bathroom. When she looked behind her, she saw a trail of blood. “I passed a clot, but it was a clot the size of a softball,” she reveals. She called her OBGYN again, and this time, she was told to go straight to the office.

As Kimmel stood up to leave, she almost passed out. Her terrified husband helped her to the car, and they rushed to the doctor. How was it possible to be feeling perfectly fine one moment, and bleeding excessively the next? WHAT IS PPH?

One of the leading causes of maternal mortality is postpartum hemorrhage (PPH)—that is, if it’s left untreated. But only 3–5% of women experience PPH, says Dr. Brian Rinehart, director of the maternal high-risk program at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. What exactly is PPH? It’s defined as excess bleeding after delivering a baby—some professional organizations say 500 cubic centimeters (or 500 milliliters) after a vaginal birth or 1,000 cc after a C-section;

however, the World Health Organization suggests it is 1,000 cc or greater of blood loss in the first 24 hours. Rinehart explains that, ultimately, how much blood is too much will vary patient to patient. Then there’s also late or secondary PPH, the rarer form, which occurs after the first 24 hours. That’s what Kimmel experienced. There are three main reasons that PPH occurs: • uterine atony (when the uterus doesn’t contract after the baby is born) • lacerations (or tears) at birth • retained placenta or placenta fragments. We know the immediate causes of PPH, and research suggests that certain conditions (including placenta previa, overdistended uterus, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, obesity and having multiple babies) may increase the chances of PPH. But in the majority of cases, there are no underlying risk factors, says Rinehart—so technically, there’s no sure way to prevent it. “There is no magical dietary supplement or routine to make yourself healthier to avoid [PPH],” he says, adding that

“There is no magical dietary supplement or routine to make yourself healthier to avoid [PPH].” 28

baby | 2020

BLOOD DROP AND CRAMPING: NOUN PROJECT

what you need to know about PPH