15 minute read

Conceptual framework

Conceptual framework

Which theories form the basis of our concept? Which theories were used to answer the research question?

Advertisement

With the open-door policy of 1978 (Xiaobin, 2004), the region of Greater Bay Area underwent a swift economic restructuring, transforming from the agricultural sector to industrial, manufacturing and service-based economies subsequently. Through our research, we identified patterns of negative consequences caused by this economic drive in the region. The current development model based on efficiency and high profits is detrimental to people and the environment.

The project’s goal is to shape the transition from a profit-driven economy to a people-ecologic centric growth. It also addresses the demands on urban cores and the plethora of vulnerabilities that are plaguing GBA. A body of literature was studied to understand the region and resolve these challenges. This chapter explains the conceptual foundation of this transition. The foundation is mainly based on the following theories. Resilient thinking, Territories of

inhabitation, Transitioning people from passive actors to active agents of change, Knowledge distribution.

RESILIENCE BUILDING

While the market liberalisation in GBA led to high levels of employment and growth of urban centres, they have also contributed to negative consequences on the ecological systems like high levels of migration, loss of biodiversity, the disappearance of mangrove forests, water scarcity, air pollution and exposed millions of people to environmental hazards (Zhijia, 2015) (Chan et al., 2013). The inequalities in the region express themselves in stresses, unhealthy lifestyles and unjust claims over natural systems and territories (Lankao, 2011). These contribute to the growing environmental criticalities and social-economic vulnerabilities.

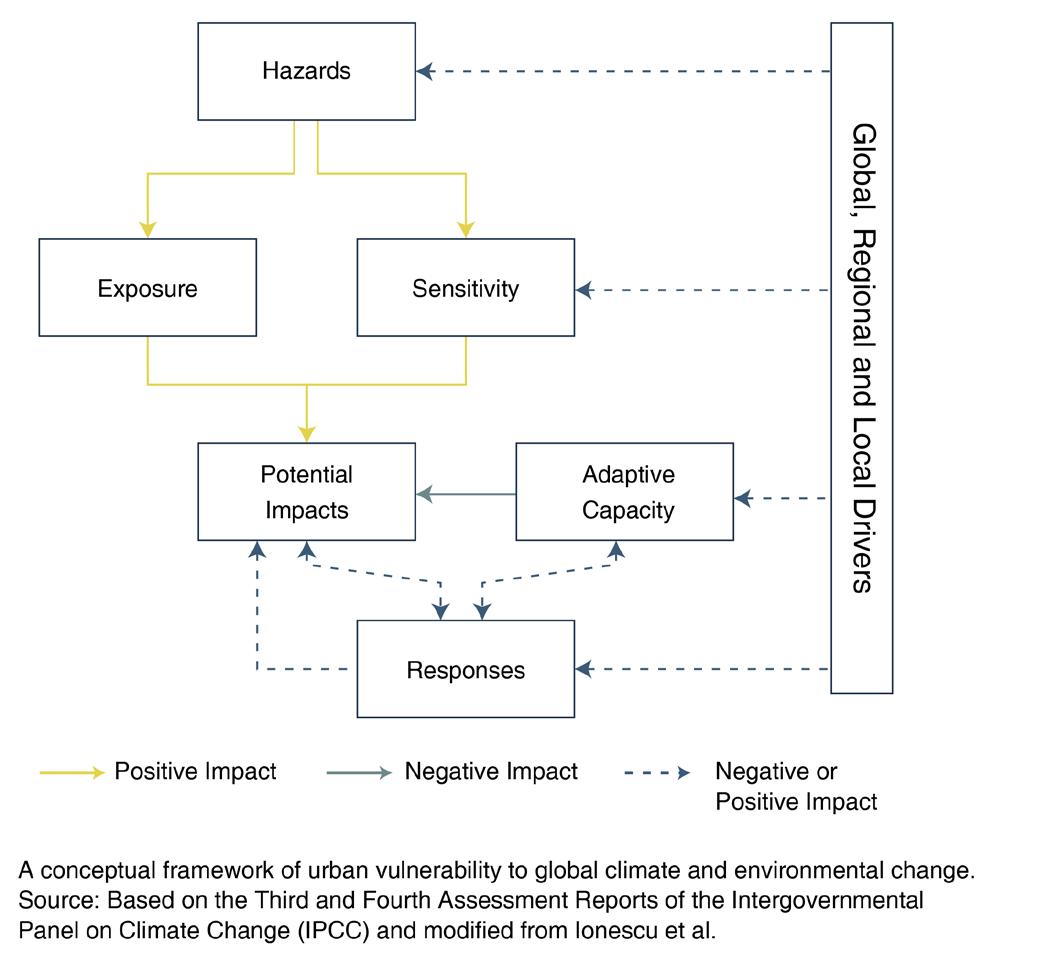

Vulnerability is the exposure of groups of people, individuals or systems to external or internal stresses. (Adger, 2000). Social vulnerability generally means disruption to livelihoods and loss of security. Stresses could be defined in both social and ecological terms. Social stresses could mean a lack of income and resources, civil strife, impending war and other factors (Chambers, 1989). Ecological stresses could mean potentially irreversible changes to the environment that might create an impact on human life that is dependent on it like flooding, heat strokes, droughts etc. Resilience increases the capacity to cope with stress and can be. considered a solution to deal with vulnerability.

Building resilience needs to be an integral component of climate adaptation, environmental management, regional economic development and strategic planning of the Greater Bay area to address the prevalent challenges. Resilience is broadly described as the capacity to bounce back (Davoudi, 2012). There are three broad classifications of this which are constantly overlapping: social, economic and

ecological resilience.

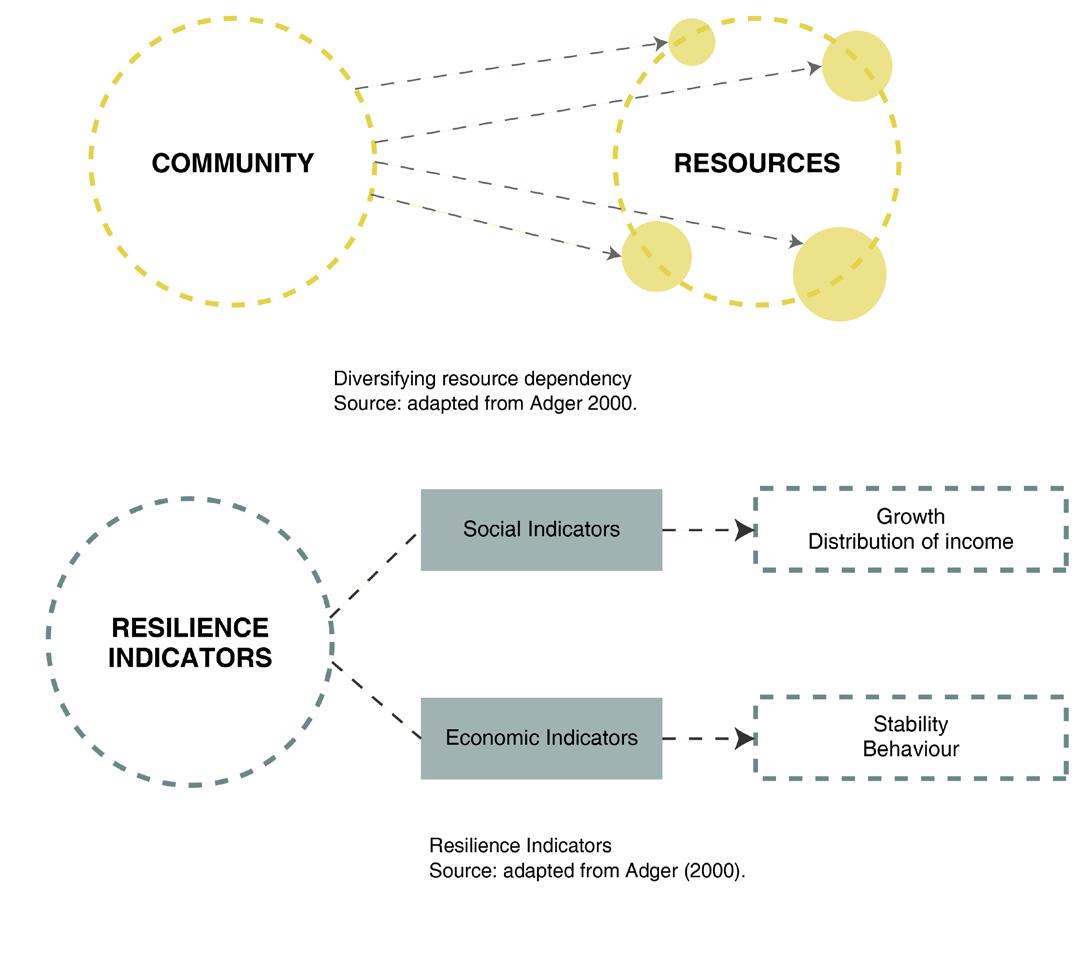

Social resilience can be defined as the ability of groups or communities to cope with external stresses and disturbances (Adger, 2000). These external factors could be social, political or environmental. Stresses can be characterised as disruptions towards communities, livelihoods and forced adaptation to the uncertain physical environments. In the region of GBA, the pervasive nature of growth often causes stresses that are related to economic and social situations like lack of income, poor health services, accessibility of natural resources (Chambers, 1989).

Human and ecological systems are interdependent, their resiliences are linked through the dependence of communities and their economic activities on ecosystems. The degree of these dependencies is uncertain and understood through historical, cultural and socio-political factors. In the region of GBA, the agrarian communities started giving up their land for the process of development. The new hard engineering strategies that came into place disrupted the natural balance of the region exposing these communities to greater threats of flooding.

Ecological resilience is buffer capacity or the ability of a system to absorb perturbations, or the magnitude of disturbance that can be absorbed before a system changes its structure by changing the variables and processes that control behaviour (Holling et al., 1995). The human intervention on ecosystems has historically suggested the inevitable decline in its resilience with technological lock-in and reductions in diversity (Holling & Sanderson, 1996).

The concept of resilience depends on other configurations of human-ecological dependencies which can have explicit spatial dimensions to this process (Adger,2000). These concepts; environmental criticalities and social vulnerabilities are distinct in how they can be used to define the state of certain complex systems. On an ecological front, the region is on the verge of reaching a critical condition where potentially irreversible changes may be experienced. The social vulnerability to this economic and environmental change should be studied or observed in relation to human-induced risks or natural hazards (Klein et al., 1998).

Resilience thinking includes studying the functioning of the system and not just the stability of its components (Pimm, 1984; Holling et al., 1995). It is also imperative to develop resilience to disturbances than resistance. To observe social resilience, we have to consider economic factors, institutions in power and demographic change. Diversifying resource dependencies of communities enhances resilience through stability and functioning and this is key to biodiversity conservation.

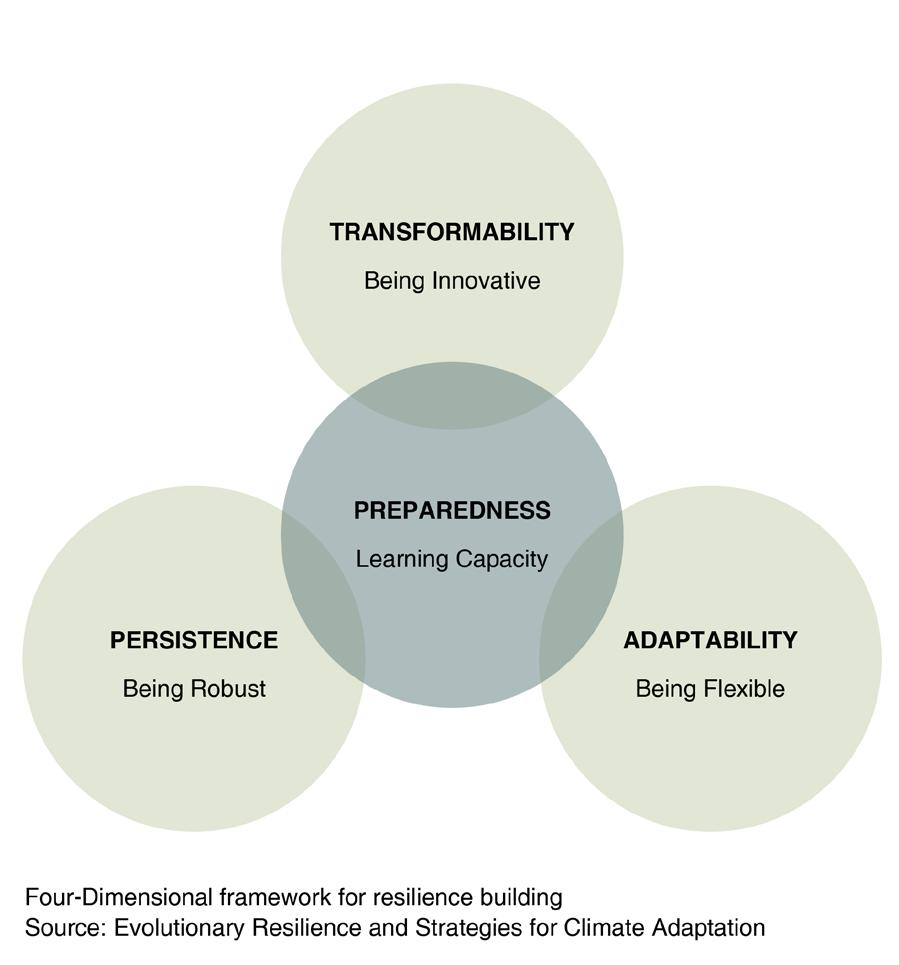

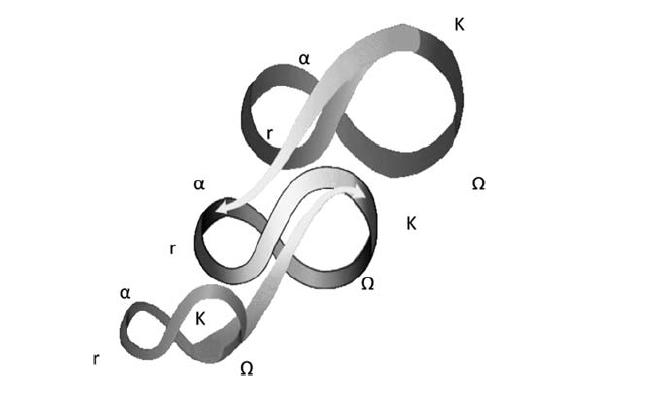

Resilience thinking has its limitations when applied to systems in continuous evolution. The idea that the stability domain to which the system has to return remains fixed over time is disputed (Scheffer, 2009). ‘Evolutionary resilience’ idealises not just the ability to ‘return to normalcy’ but the ability of complex systems to change, adapt or transform in response to stresses and strains (Carpenter et al., 2005). This method emphasises on persistence, change and unpredictability. The systems in this theory undergo four distinct phases of change called the adaptive cycle; The growth phase (r), conservation phase (k), creative destruction phase (Ω) and reorganisation phase (α). This kind of resilience thinking doesn’t allow for human interventions to break the cycles of persistence, adaptability and transformability across multiple scales and time frames in ecological (natural) systems (Davoudi, 2012a drawing on: Holling & Gunderson, 2002; Walker et al., 2004; Folke et al., 2010; see also, Galderisi et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2010). The changes in resilience will be anticipated and be dealt with through systems design and management.

Cities are living organisms that are vulnerable to change; resilience should be understood not as a static presence but a process to withstand these nonlinear unpredictable dynamics and patterns of abrupt changes. Urban centres cannot function independently and need ecosystems near and far to survive. These accessories lose their capacities to persist under constant demands. These multiple networks of systems need to be encouraged to build resilience by creating complex adaptive socio-ecological systems.

TERRITORIES OF INHABITATION

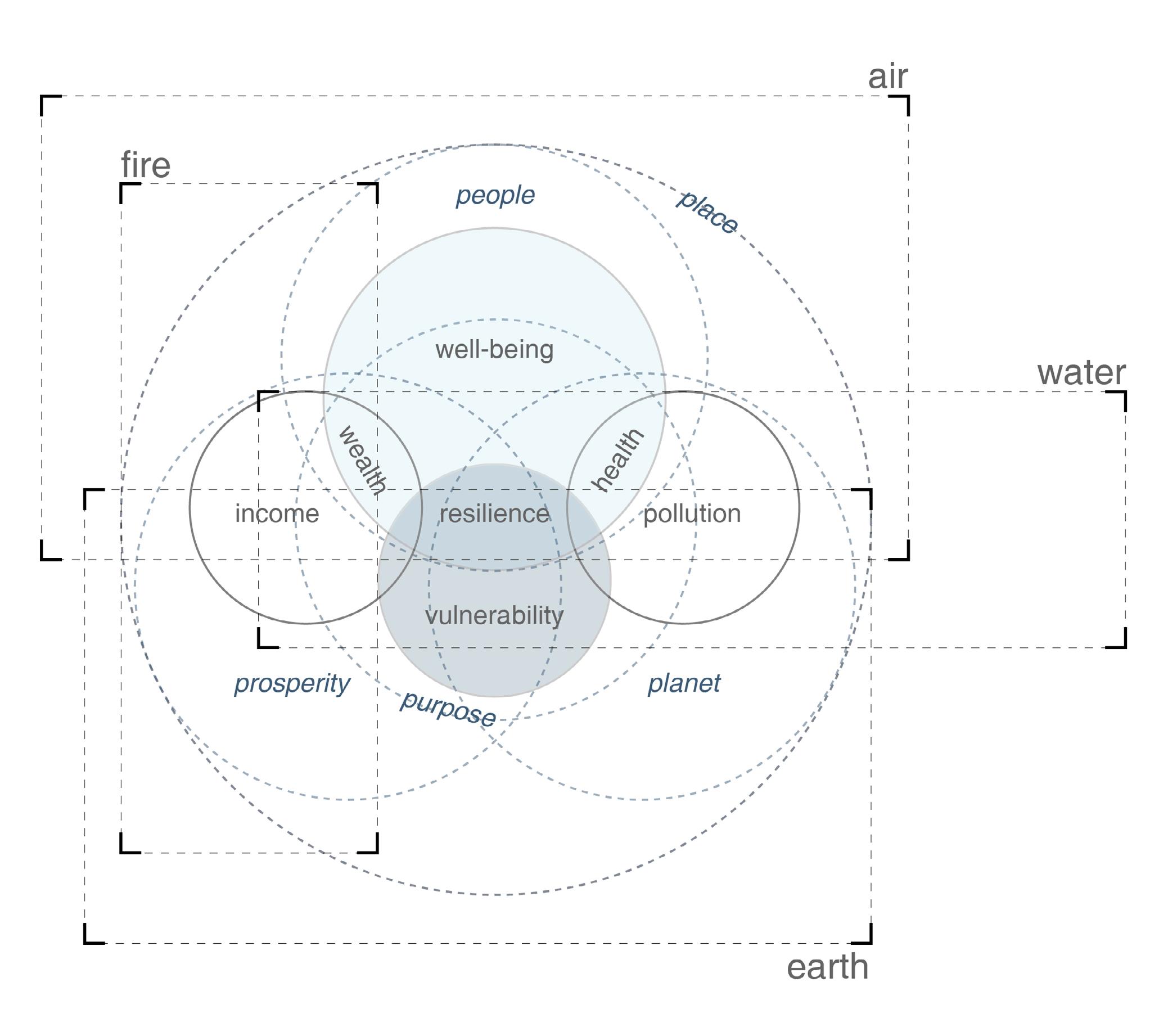

Our project explores the region of GBA through the lens of territories of inhabitation. The term ‘Territory’ refers to fire; economy, air, water and land. The transformation that was ignited by the fire created unequal and unfair accessibilities to these territories. The issue of access needs to be discussed with broad considerations of social, political and economic dimensions of urbanisation (Dougass.M, 1992). It is important to consider who has access to the clean air and water, who are the major pollutants of these territories and how access is monetised in the region of GBA. The perception of access by governments, the private sector and the citizens is also critical and multifold. The relationships between inhabitants and their territories depend on their economic and social background.

Due to the continuous economic activity in GBA, there were major changes to the environmental and social structures. Poverty remains a persistent feature of society at all levels of per capita income, including the highest. Along with it, accelerated economic growth brings its own forms of environmental crises, social dislocation and heightened social inequalities which the current market has not displayed any capacity or inclination to resolve (Mike Dougass, 1991). Even though alleviating poverty is seen as the main driving engine behind the economic restructuring, fair portions of such fruits of development are not obtained by the major sectors of the population (Midgley.J, 1984; 1995). There is a paradox of wanting to legitimise and redistribute economic fruits towards the masses and at the same time to encourage accumulation and serve class and corporate interest. This dichotomy is usually won by the interests of the few and makes the economy work for certain sectors of society.

These masses operate at different levels of vulnerability, and there are multiple factors to determine this based on the scale, context, economic and cultural backgrounds. These levels of vulnerability could be understood in terms of their access and entitlement to resources. The security of the agrarian societies i.e, the food producers and the farmers of the rural areas is linked

to their ability to cope with climate change and their claim on the land and water resources. The vulnerability and assurance of the daily wage migrant workers and unskilled professionals in urban areas are defined in terms of access to new learning opportunities that can aid in changing their life for good. The lack of access to clean water, air and sunlight especially for these workers living in cage homes and dormitories considerably reduces their resiliency and adaptive capacity by locking them in these unfortunate lifestyles.

The point of access to natural resources has been frequently contested raising issues about the impact of this lack of accessibility on environmental degradation of this region. When viewing environmental distress and poverty together, the major conclusion to be drawn is that the consequences of environmental deterioration fall heaviest on the poor (Cuentro et al.,1990). The natural resources of the region were used by the few actors through accumulation and competition. There is a divide in the way resources are accessed or granted to people or different economic strata.

Adger and Kelly pen down the term`architecture of entitlements’ to understand the relationship between patterns of access and social vulnerability and how these are constructed. These can be understood as manifestations of material entitlements at an individual level and assimilation of these claims at the community or population level. They are also studied at the institutional or the regional level, where these entitlements are formed, managed, contested and distributed among different groups of opposing interests.

PEOPLE AS AGENTS OF CHANGE

The management of these environmental resources has contriving rules that are often biased against the vulnerable (Eckstein.S, 1990). The poor concentrate near the new factories, live and work closely to polluting industries which lower their health considerably. They also witness a weakening in the social and political construct of their communities. This is amplified by the reluctance of governments to recognise indigenous socio-political networks and leadership (Dougass.M, 1992).

To address these grievances, two solutions are usually discussed. Either the government should extend the role more providing affirmative action or social programmes to address these issues or conversely, the market and the company should be looked at to provide solutions for maintaining their workers’ health. What has been consistently missing from the debate is the role of the social communities to organise themselves and promote self-management of resources and rights (Eric Hyman, 1990). Instances show that it is the poor who are the unconscious caretakers of the environment through the types of jobs generated by the blatant environmental disregard on the part of a fluent and elites.

In China, the top-down governance policies leave little to no decision making power to the people (Douglass.M,1992). However, instances across Asia have shown that smaller organisations functioning at a local scale could make significant changes to the ways of environmental and social management. Despite systems of iniquity in place, the poor or the vulnerable communities continue to settle in cities and are able to form communities and live in neighbourhoods that aid social stability.

Even with the government proving unable and unresponsive to acknowledge these gaps between communities and their access to environmental needs in most cases, especially in the low-income habitats, these vulnerable communities managed to get together and strategise broader national and international coalitions to invade and develop unused urban land, to build houses, deliver water, and engage in other environmental resource access and management activities (Mike Dougass, 1992).

Our project envisions similar interventions that would drive the notion of people becoming active agents of change instead of passive bystanders that are vulnerable to these negative consequences of change. Since social vulnerability can be linked to the pattern of access to these communities, it has to become an important framework in multiple scales of governance.

KNOWLEDGE ACCESS

Central to our vision for the Greater bay area is the assimilation and dispersion of knowledge. There was an intrigue to understand if knowledge can be considered a public good. Elinor Ostrom, in her book, Governing the commons, defines public goods along two axes, economic goods and units of exchange. Public goods are non-rivalrous and non-excludable (Rocco, 2020). New knowledge is generated constantly and is infinite. It isn’t reduced when someone consumes it and once given, can’t be taken away. However, the key issue with characterising knowledge as a public good is that it’s not free at the point of delivery. It is an excludable entity. Knowledge is highly privatised in the capitalist economy (Hirschman, 1977). Natural incentives exist to create private goods as accumulation seems to be the natural aspect of human character (Hirschman, 1977). ‘Knowledge Commons’, a concept which is half socialist utopian and half neoliberal is a belief that technology can enable the effective sharing of knowledge as a resource. The resources that can be shared and explored by all would then act as effective foundations for value creation (Hess & Ostrom, 2006). So to determine and drive knowledge as a public good, we needed to ascertain different forms of provision. Dispersion of knowledge and its just sharing requires the same tools that would support the creation of public goods. Especially, for an entire paradigm shift, these mandates and legislatures are of utmost importance.

In GBA, globalisation and economic restructuring, caused demographic and (Dickon, P. 1998) structural alterations. The process of globalisation generated negative effects on the employment of lowskilled workers (Xiaobin et al.,2004). The creation of mobile and flexible jobs caused negative effects on manual labourers. With the further transition from manufacturing to the service sector, people without professional knowledge are phased out of employment (Xiaobin et al.,2004). These vulnerable communities include middle-aged, unskilled female workers and youngsters with low educational level who couldn’t find suitable jobs for this.

The current trends of education in the Greater Bay Area is quite separate from local knowledge and historic practices. This

indigenous culture about the relationships between ecological systems and human systems have been lost in the process of development.

The current model of knowledge concentration needs to be diminished because it results in the accumulation of this resource in the hands of a few actors who would, in turn, control the extent of its impact. Distribution of knowledge creates greater benefits and enables the creation of even great value. Since the region’s future vision looks at a drastic shift that needs knowledge build-up and innovations, there is a need to establish new networks of knowledge dispersions. These public goods need to be resourced at a global level and mandated through legislation.

Knowledge and capacity building are some of the few solutions to bridge the gap of disparities and also provide opportunities for vulnerable communities to achieve a better quality of life. To engage all the citizens in this knowledge economy, the new developments should be organized in a way where opportunities for participation and engagement are maximised and a sustainable lifestyle becomes more obvious and easier to achieve (North & Nurse, 2014). For the creation of a synergetic network, the local potentials are identified and boosted through the dissemination of knowledge. This knowledge takes different forms at different scales and contexts to work holistically across the region.

For the unskilled labours and unemployed citizens in urban areas, it would be vocational training. For the farmers and rural citizens who are under threat of losing their land for development and external competition, it is about engaging in local economies that support this development and collaborating with them. It is also to develop different methods of farm production to make an efficient transformation in agricultural practices that can help the area address the issue of low land productivity. Localised economies do not mean independent actors, they still rely on each other and the overall region to develop synergies. They bring forward strong and integrated regions that complement each other in terms of functionality and identity and the local economies engage citizens to participate (North & Nurse, 2014).

Local methods of sustainability, resilience thinking need to be encouraged, propagated and integrated with the new technological advancements. In our proposal, knowledge becomes the new centrality that shifts the growth of this region.

CONCLUSION

Seemingly endless resources are exploited in the process of development drastically changing the existing natural systems. Urbanisation is a complex process that requires social, political and environmental changes. However, these very alterations in return caused high stresses and disturbances in natural and human systems leading to socio-ecological criticalities in the region of GBA. External disturbances with the lack of foresight and regard to the ecological systems also made this region increasingly vulnerable to environmental hazards and risks. People, on the other hand, were sidelined from the decision-making process leading to socio-economic vulnerabilities.

For the longest time, profit over prosperity and well-being drove the regional development of the GBA. As a result, the fragility of the interdependency of territories of inhabitation came under intense strain creating a dangerous precedent for the future. These territories are complex and bound by human systems. The human interventions, conscious or otherwise, have diminished the resilience of the region. Resilience thinking is crucial to building preparedness, persistence, adaptability and transformability of interdependent systems.

Building evolutionary resilience is a mutually dependent cross-system approach affecting both natural and human systems. Enabling people to become active agents of change can facilitate synergetic development to themselves, society and the environment. The silent stakeholders; the planet and the future generations should be acknowledged to maintain the region in a state of dynamic equilibrium where the three pillars; people, planet and prosperity balance each other out.