COMMON

Cover photo by: Sindre Deschington

© 2022 Photo I Students

© 2022 Danish School of Media and Journalism

Print: Ecograf Gruppen Printed in Aarhus, Denmark 2022

Special thanks to: Gitte Luk Søren Pagter Lars Prevelakis Bai

Thank you to all who shared stories for their trust and patience.

Photojournalism

Danish school of Media and Journalism

Becoming

Juha-Pekka Huotari

Ambassador against the odds Sonja Smalian Wonderland Disrupted Hilma Amanda Toivonen

The 1% that matters Biayna Mahari Perfection Gabi Broekema

Moving On Finn Winkler

Fighting Friends Ahmed Abd El-Gawad

Maani Ajorami Núria Sanz

Is anybody out there? Sindre Deschington

drowning within Mehbuba Mahzabeen Hasan

After years of searching for a place to sleep and getting in trouble with the law, Pino Paank is now living a life that suits him. The wounds have healed, but the scars keep him aware of the past being real.

by Juha-Pekka Huotari

by Juha-Pekka Huotari

Next to a patinated red brick building in the former industrial harbor of Sydhavnen, a group of middle-aged women are glancing around as if they are a bit lost. The yellow door of the building is pushed open, and a man wearing a long, brown trench coat and bright red loose jeans with blue suspenders steps out. He opens his army green military-style shoulder bag and takes out a pack of rolling tobacco, papers, and filter tips. With a swift move, he rolls a cigarette.

“Hello, my name is Pino, and I will be your guide to day” the man introduces himself and nudges his cap a bit higher.

He reaches into his pocket for a lighter. Inhale, ex hale, and a puff of smoke floats in the air. “I got evicted from my first apartment at the age of 18,” Pino starts to unravel his life story. “A guy who wasn’t a friend of mine thought it would be funny to start a fire in the middle of my living room. That was the start of my ten-year career as a couchsurfer.”

Pino Paank, 34, is one of the dozen guides taking people around the city of Aarhus, Denmark, and showing them what the city looks like from the per spective of the socially vulnerable. They are called Poverty Walks. Today, a group of women working closely with refugees and immigrants get to hear Pino.

Pino lived his first years on a small island called Fanø in the southwest of Denmark. He was his parents’ first child. After they got separated, Pino stayed with his mother. “I only have a few memories of my biological parents living together,” he says.

The North Sea coast and island life got left behind when Pino and his mother moved to Djursland, the east of Denmark. His mother found a new man, and Pino got two step-sisters. The relationship eventually ended, and Aarhus called for the single-parent family when his mother started studying.

Pino wasn’t the easiest teenager to handle for a single mom; he´s the first to admit that. At the age of 15, the situation escalated to the point that he was put into foster care. He talks with a sense of under standing about his mother’s decision to seek help.

“First, I was at boarding school and then was sent to a place for young troublemakers.”

On the edge of adulthood, he got his first taste of the criminal justice system. While staying in an institution that deals with young offenders and teenagers who cannot stay at home, he punched one of the employees.

The sun hits the edges of the brick building and makes a sharp-lined shadow behind the women in Sydhavnen. Bicyclists and cars drive by, and Pino reminds the group to look out for the road hogs as he leads them toward the city center. Every now and then, a friend or acquaintance wawes at Pino, and they quickly change a couple of words. “Pino is the best guide,” one of them shouts.

The walk continues into an alleyway behind the Aarhus police headquarters. The women gather around Pino as he puts out his cigarette with his fingers so he can light it up later. “I have had my fair share of clashes with the police and security guards,” he starts.

His first conviction was at the age of 17, and two were still to come for fighting with the police. Three times in jail and over 60 times arrested. “I stopped counting after that.” There is no pride nor too much regret in his voice. Things happened, and he took them as they came. A sense of bitterness can be read from how the authorities treat the socially vulnerable. “The police lack the understanding of how to deal with people living on the streets.”

Pino started telling his story on guided tours just before the covid pandemic hit the world. Once a week, people from different social classes get to walk in his shoes for a couple of hours. They listen carefully when Pino talks about his former drug use, shoplifting, and thoughts on how we could better support

the people on the outskirts of society. He received help when he least expected it; while serving his last sentence in jail.

A couple of seagulls scream and fly over the Aarhus river near a big department store. Pino leads the group through the crowd to a slightly calmer place and suggests that they can sit on the benches next to the canal. An elderly man stops to listen in on how you can couchsurf for almost a decade.

After getting evicted from his first apartment at 18, Pino had to find a roof over his head. Going back home to live with his mother wasn’t an option, so he started sleeping on friends’ and acquaintances’ couches. He built a network around him to have a place to sleep but sometimes was forced to lay his hat under the sky.

“It was a learning curve. I needed to make myself useful, clean a bit in the apartment, do the dishes, that sort of thing. And also stop being an asshole”, Pino refers to his former self.

A typical couchsurfer’s day is spent walking the long streets in the city, looking for a place to sleep the next night, and trying to stay out of trouble. And trouble usually finds you when you are trying to survive in the rain and cold, as Pino puts it.

After getting out of prison, Pino got a new beginning. In the midst of serving his sentence, he was offered an apartment. “I was angry at first because I counted on the system to fail me again, but this time it sur prised me.”

Living without a home for years leaves traces. Moving into a place of your own isn’t smooth sailing from there on; it takes time to adjust to a new situation. Many go back to the old habits because that is all they know. Pino still found himself sometimes on other people’s couches. “I couldn’t be alone because I had been staying with someone for so long. I was still spending much time on the streets,” he recalls.

After six years of living in a compact apartment close to the city centre, Pino feels privileged to actually have a place to call his own and invite people over. There are still things to learn and improve. First on the list is going through everything saved over the years and sorting the items on the bed, so he can finally sleep on it instead of the couch.

One person has been spending more time in Pino’s apartment than others. While volunteering at Skraldecaféen, which helps people in financial need with free food, he met a Ukrainian refugee, Nadia. The couple has been seeing each other since June.

“We are still trying to figure each other out because of the cultural and langue barrier. We communicate in English, but I teach her Danish every time we meet”, he grins softly.

Getting an early retirement has eased the transition of getting back to an everyday life. The opportunity to work some hours without it cutting into his pension is appreciated. Alongside the guided tours, Pino has another job collecting bottles and cans with a deposit from private companies and sorting them. “I really like my life now,” he says.

He stays in contact with his mother and step-sisters and dreams of paying his debt and buying a boat. The first plan is to sail the inner rivers of Germany.

The sun flares the Rainbow Panorama’s colours from the rooftop of Art Museum Aros. Pino checks his mo bile phone for the time as he leads the group to the last stop of the walk. “Now, it’s time for questions,” he says when the group reaches Mølleparken.

Pino hopes that the one thing that people take with them from his walks is that the next time they meet socially vulnerable persons, they will treat them as human beings. “It really hurts when people look straight through you. Sometimes a smile is enough.”

One hand raises, “Would you do anything differently if you had the chance?”

“Sure, I have some regrets and wish I hadn’t hurt others on the way. I have apologized to some people. But I wouldn’t do things differently. I went through all this to become who I am now”, Pino says.

Start-ups worldwide are researching how to harvest meat not from dead animals but as cell cultures in large tanks. Is the agricultural industry on the verge of the biggest revolution in its history? A German economics professor believes so.

by Sonja Smalian

When Professor Nick Lin-Hi drives his silver Tesla to the University of Vechta, he sees the elongated buildings ducking between the fields to the left and right of the country road. Rows of squat exhaust chimneys on the roof ridges reveal their use. Around 11 million chickens, 1.6 million pigs and 115.000 cattle stood in the stables of the Vechta district in 2021, all to satisfy people‘s appetite for animal flesh.

The region in Lower Saxony is a stronghold of con ventional livestock farming in Germany, with roughly every second euro earned coming from meat. It has evolved a highly efficient system involving everything from rearing animals to processing their meat. And it has made the people of the region prosperous. Nick Lin-Hi wonders how long this will last.

Start-ups worldwide, from Silicon Valley to Singapore, have long been working on cultivating meat in a Petri dish. So-called cultured or cell-based meat would enable animal protein production in controlled laboratory settings, independent of external factors such as climate or soil conditions.

Cultured meat promises a better environmental balance: significantly less land, water and feed con sumption, reduced emissions, less animal suffering, and, and, and - the list of possible improvements is long. And cultured meat also comes with the promise of rich, juicy profits.

The agricultural economy could soon experience the next big industrialisation push.

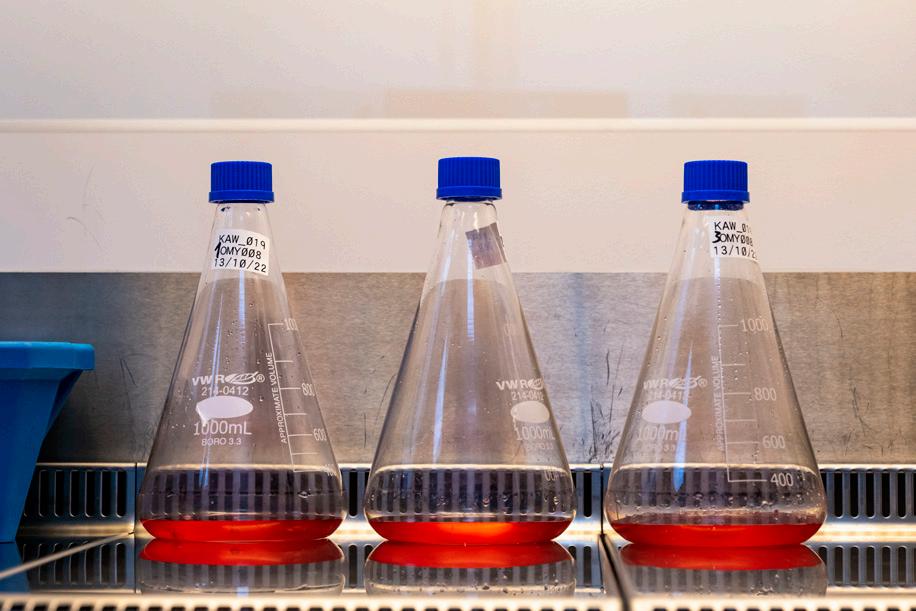

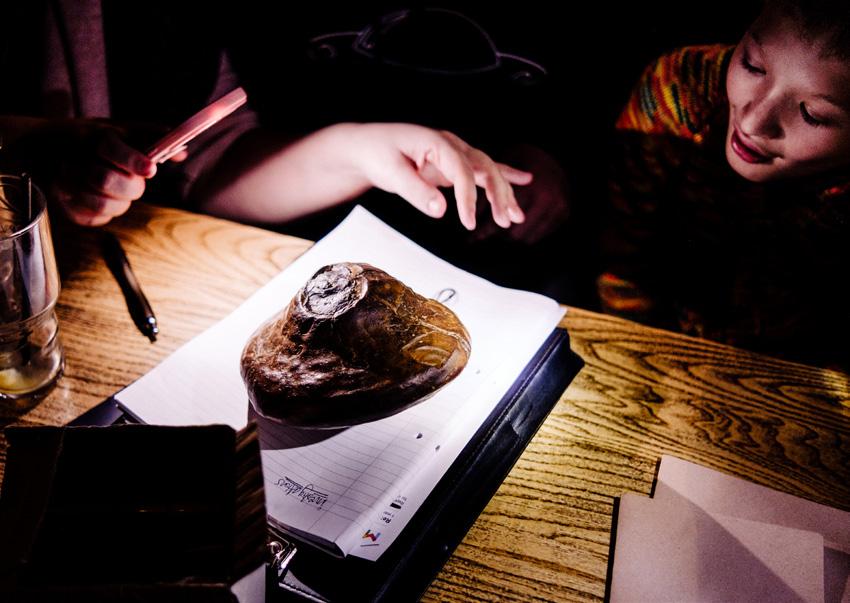

Pictures on the right page: Nick Lin-Hi visits the start-up Bluu Seafood in Lübeck, a city in Northern Germany. Founder Sebastian Rakers shows him cultured fish cells in a red colored nutrient solution.

“The new technology has the potential to be disrup tive. It could turn the rules of a market upside down within a very short time and destroy established value chains,” says Nick Lin-Hi, a researcher in economics and ethics who has been observing the development of cultured meat since 2017. He estimates that by the time it is ready for the market, it could be “very fast or take another ten years”.

Market maturity is a technical challenge over which the 42-year-old professor has no control. Instead, he is concerned with the social challenges: its acceptance by society.

He likes to describe this emerging technology as hu manity’s most incredible opportunity for sustainable development. But he worries that Germany, one of the world’s largest meat producers and exporters, carelessly let this opportunity slip away.

To ensure this does not happen, he has made it his mission to remove people’s fear of the new. And so the researcher travels to the university on a sunny Saturday afternoon for a two-hour TV interview. His hands cut through the air, adding visual exclamation marks to his answers to the reporter in the empty lecture hall.

The TV team has just returned from the USA. In Silicon Valley, they visited start-ups and tasted one of the still rare burger patties made from cultured meat from the experimental laboratory.

Now they want Lin-Hi to give them a German per spective on global developments. The professor from Vechta is considered the leading expert on this topic in Germany. He laughs when people say this and likes to answer: “After all, there is hardly anyone else who deals with the subject.”

Although climate change will make classical agricul ture in many regions impossible, while the demand for animal proteins will increase by 85 per cent by 2050, according to United Nations estimates. At the same time the world’s population will raise to nearly ten million. As a business economist, Lin-Hi also has an eye for the effects on the domestic industry. “It would be fatal for Germany if we didn’t play a part in this technology of the future right from the start,” says he. “We should consider that the last decade of classical livestock farming has already dawned.”

Such statements often lead to harsh criticism. On his mobile phone, Lin-Hi scrolls through the comments below a recent interview of his in a farming magazine.

“Prof. Lin-Hi, was he also the developer of the coronavirus?” he reads and rolls his eyes. Growing up in Hildesheim, his mother is German, and his father comes from Madagascar, he experiences racist innuendos from time to time. But, he says: “What dis tinguishes me is not my family background, but my different way of thinking”.

Many industry experts refuse to participate in de bates when “this professor from Vechta comes”. For this reason, he sometimes introduces himself as an “ambassador in the tradition of Till Eulenspiegel” when giving talks to farmers and cattle breeders. Through whimsical stories the historical joker wearing a jester‘s cap held up a mirror to the rulers and pointed out grievances. This verbal trick is supposed to protect him against personal attacks.

The fact that Lin-Hi does not hold mainstream opinions has characterised his career, but he isn’t a nutritional faith warrior. In his fridge, lactose-free milk in a Tetrapak stands next to milk fresh from the farm. Three hens in his garden deliver eggs, and Brussels sprouts grow in the small raised bed. The 42-year-old has been researching sustainability since 2004, when his doctoral advisor warned him that he was pursuing a niche topic. At the time it was nothing more than a green marketing trend.

Nevertheless, he concentrated on ethical issues in business from then on. As a result, his view has prevailed, greenwashing is no longer socially acceptable, and information on sustainability performance is now a mandatory part of the annual report. The new niche topic is cultured meat.

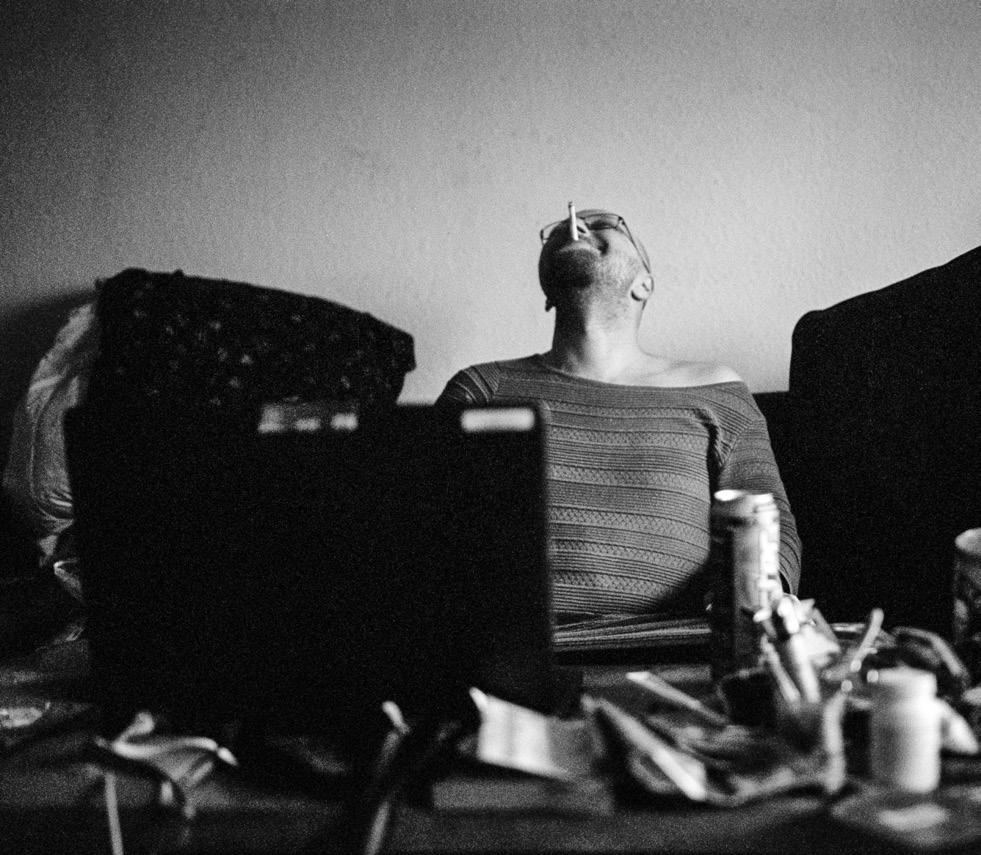

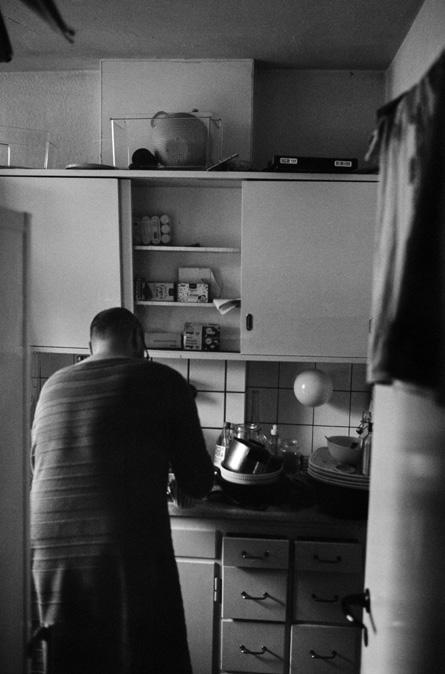

The compressed-down duvet on the bed in Lin-Hi’s study reveals that his night was very short. Seated at his laptop in his sweat pants, he takes a big sip from his tea cup, as he enters the last corrections into his latest research proposal. With his team of nine, Lin-Hi wants to find out what influences the acceptance of cultured meat.

From his small study, Lin-Hi looks into the garden. A wooden climbing frame supports a yellow slide and a red swing where his two daughters, three and seven years old, love to play. “I promised them that I would protect our earth,” he says. He knows that this requires a lot more than scientific publications. So he will continue his journey to spread the message in podcasts, interviews, talks and his column in the local newspaper.

by Hilma Amanda Toivonen

by Hilma Amanda Toivonen

”My guess is that the ground here will be quite full in less than an hour”, says Helene Paamand to her diving partner Katrine Larsen, as they prepare to jump in the autumn-cold water in full diving gear on the Øresund shore, a bit north of Copenhagen. She stuffs her hair strands once more tighter under a neoprene balaclava, to make sure that the visor doesn’t get wet on the inside.

Human activities are damaging the world’s oceans every day, by oil and gas drilling, industrial waste, pollution, and climate change. The ocean’s natural chemistry is changing, habitats destroyed and marine life killed all over the globe.

While humans are the ones causing the destruction, there are also some of us fighting it. Helene Paamand is one of those people. She is a 41-year-old diver living in Copenhagen, who is dedicating her life to cleaning up the ocean floor.

Helene goes diving at least once a week. She does two types of diving: On leisure-dives, as she calls them, she goes down usually by herself, and col lects one or two big bags of trash out of the ocean. Another type is a proper clean-up dive, done with at least one other person, and at times even with dozens of people. In these dives the amount of trash is much bigger.

The dark side of our take-away and single-use culture is laid before Helene’s eyes in a way few of us get to experience. Underwater she becomes a witness to animals getting entangled in trash and plastic ending up in the stomachs of animals, eventually causing them to slowly starve to death. For her, the way that we deal with our plastic is very scary.

“With a lot of themes regarding the environmental change, scientists know where the sort of tipping points are. With plastic pollution however, we really don’t know yet how it affects everything. But with what we can already observe – I’m thinking that this can’t be good”, Helene contemplates.

An architect’s deep dive

Helene’s life hasn’t always been this way. As a young adult she studied architecture, and by her early 20’s she already had a well-paid job in an agency in Denmark.

But then a holiday trip to Egypt changed everything. She ended up working for a local diving school. She worked indoors first, but the school soon offered her an education to become a diving instructor. The underwater world blew her mind: it felt like entering a wonderland.

“I wasn’t a very good diver to begin with, but I fell in love with the underwater world immediately. It is truly the closest to paradise we can get on this earth”, she says.

The planned couple of weeks eventually turned into almost 4 years of full-time diving instruction around the world. Life was beautiful, but already then, Helene saw the trash.

“I guess I was still in denial of it. In the most touristic areas, where I often worked, it was so dirty that I guess I felt powerless. I just didn’t know what to do or how could I make a difference.”

Helene’s top ten findings: cans, bottles, snack wrappers, cups, utensils, take-away containers, hygiene pads, fabrics, fishing gear & tyres.

A class of third graders at Sankt Joseph Søstrenes school, Copenhagen, is drowning Helene in an end less stream of eager questions. Their eyes sparkle as they all plan on being the fastest picker of their friend group after school.

Helene has just finished a two-hour presentation. She started off showing things that are easy for a kid to love: sea creatures, coral reefs, huge underwater forests. Slowly the presentation slid into photos of piles of trash, animals entangled, waters full of dirt. Destruction and ugliness.

Now some of the children are announcing that they will become pick-up divers, too.

“I want to be a bit tough with the children, challenge them to think. I believe they still have this mental tap open, that their parents’ generation has mostly closed. And honestly, I think kids of today are going to be really angry with their parents”, Helene says.

Helene does quite a lot of public speaking, because she feels that she has to.

“I see so many divers that have not opened their eyes to what’s going on. How could the ordinary people see it, if even the folks underwater don’t want to?”, she says.

”Would you have some bags for us? We need to start picking on our way home!”

After four years of instructing abroad Helene moved back to Denmark with her then-husband. The diving instruction had started to take a toll on her.

“I was surrounded by this immense beauty, but also struggled just to get by in life. The hours are long, work is very physical, and the pay is not good”, she recalls.

Helene started working half a year in Denmark, and then travel and dive another half a year. Life was good, but still she couldn’t ignore the fact that it felt empty. She didn’t really know why she was doing what she was doing.

Gradually she started to get more interested in the pollution of oceans.

The more she knew, the harder it was to ignore it. The more trash she picked up, the hungrier she became for picking. She trained her eyes; She started to see trash everywhere, and it became increasingly hard to leave it in the nature.

“I have developed this irresistible urge to get the trash up. I can’t even go for a walk with friends today without going crazy with picking. Luckily my good friends understand, they actually find it quite funny”, she laughs.

When Helene looks back at her life, it has never been exactly easy for her. From early on, she suffered from “clashes”, strong depressive periods that would always eventually pass. After moving back to Den mark, she sought therapy for the first time in her life. “Then somebody realized that actually in between those dark periods, I wasn’t only driving faster, I was driving like 170 kilometers an hour”, she explains.

She was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which was a relief after years of struggling.

The diagnosis and time have been healing and taught her to understand and listen more closely to her symptoms. Being underwater is also a kind of therapy. Even in her worst days, she will feel better after a dive.

“My lifestyle is also a survival strategy. There’s the aspect of taking responsibility for future generations, but it’s also a lot just about my own aspiration to sur vive. I think all humans have a basic need for a sense of belonging and purpose. It is easier for me to deal with this world and my head now that I have found that. It just happened to be here where I found mine, but I know it could have also well been somewhere else”, she reflects.

Helene’s lifestyle still has its dark sides. A lot of times Helene feels like an alien in what she calls the normal world.

“When you’re so deep into this, it’s easy to start hating a lot of how our society functions and how people act. It can get a bit heavy sometimes. But on the other hand, I have the clean-up-divers commu nity, in Denmark and globally, where I feel more at home than anywhere else.”

We are back at the windy Øresund shore. Almost two hours have now passed. The ground has been filled with piles of dirty, slimy, and smelly objects lifted up from the sea floor. All sorts of human-manufactured bits and pieces glimmer in the soft afternoon sun. Candy wrappers, bottles and cans, and a lot of pieces of which it’s hard to tell what object they have been a part of.

The cold is forcing Helene and Katrine out of the wa ter. Katrine is shaking of cold as she crawls back to the land.

“It is never because we would have finished the work, that we stop cleaning. Physiology comes in our way first: It gets too cold or we run out of oxygen. Other wise we could be in this exact same spot for another two hours and pick up the same amount of trash again. And then another two hours. This job never gets done!”

Helene is trying her best not to fall into despair. She tries to remind herself the same story she tells the kids at schools.

“When I was born in 1981, this sea was clean. The same year the first MacDonald’s opened in Copenhagen. I remember when Coca Cola went from glass to plastic, I must have been 10-11 years old. In uni versity we had to do a project about a coffee shop, and we had to travel all the way from Alborg to Co penhagen to find one. And even they certainly didn’t have take-away cups! We have created this massive change in such a short time. Because of that I want to believe we can make fast and radical changes into a better direction, too.”

Sikandar Siddique: to the elections and back againby Biayna Mahari

We leave the office of the Frie Grønne party at Christians borg Palace, residency of the Danish parliament, through a maze of small corridors, scary stairs and big glamorous halls, heading to the other side of the city for a voters meeting. But Sikandar has not had time to eat anything since early morning so we stop to pick up food. We enter the smallest room I’ve ever seen operating as a bistro. Immediately a bald man comes out of what is probably the backdoor. He hugs Sikandar as a very old friend, they chat a little and soon we are served food probably in a little bigger portion than usual and made with a little more love.

- I’ve been going to this place for 25 years, - Sikandar says when we leave, - and now the owner is selling it,- he adds sadly, and we jump back in the car so as not to be late for the meeting.

I don’t know the city very well but at some point I notice that the small bistro in Nørrebro wasn’t on our way and we made a detour to eat here.

The Nørrebro area in Copenhagen is where Sikhandar Siddique, the young leader of the Frie Grønne, was born and raised. Growing up in a family of Pakistani immigrants in one of the toughest neighborhoods of Copenhagen, Sikandar was raised thinking that politicians were special people and that people like him never get into politics. Despite that, his father, an active figure among minorities back then, dreamed of seeing Sikandar as a politician. With his active support and help, at the age of 19 Sikandar was elected to Copen hagen’s Citizens’ Representation for the Social Democrats. Now Sikandar calls that period of his life his “father’s project”.

- I hated that period so much,- he remembers,- people were trying to undermine me all the time. At some point I stopped and told myself I will never be going back to politics. But about 10 years later Sikandar changed his mind.

- I finished my education, I was working as a consultant, going to work in the morning, coming back home in the evening, and at some point I saw this routine become my life. Sikandar’s father taught him that one should live for the people, not for himself and try to make a difference, and Sikandar saw the opportunity of doing exactly that by going back to politics.

- I thought it’s not right that minorities don’t represent them selves and I decided to do that.

Before the TV debates later in the evening, there will be a meeting with the voters in Fælleshuset, a com munal house in Aalborg. The team arrives a little later than planned, as their electric car requires charging over and over again all the way. But being, as they call themselves, a climate-conscious party, brings the necessity of also being climate responsible.

The communal house gets filled very fast, everyone is listening with great interest, some looking at Sikandar with belief, others still want to be convinced. He is planting hope for the ones who didn’t believe in democracy, as Sikhandar’s personal assistant puts it. And looking at the eyes of these people, I understand what she means.

Political debates follow up the Friday prayer in the mosque in Nørrebro. Men of different ages and skin colors sit on the floor of a big hall listening to Sikandar and representatives from other parties. After finishing his speech, Sikandar stands up to leave, but people start approaching him from all sides of the big room. Sikandar not only spends time to patiently talk to every one and answer all the questions, he also he greets people, warmly accepting any hands reached out to him with both of his own big hands, as if accepting an important treasure. A beautiful gesture of respect. When I think about it I can’t get rid of one particular question: How could someone who even a few days before the elections, between TV debates, meetings with voters and outdoor activism, keeps driving to his childhood spots to eat, who praises any person who greets him, for whom respect and loyalty are not just empty words, how could someone like that leave the

political party he has been elected with to the parliament – Alternativet?

- I didn’t want to be a slave, - Sikandar says,- if I would go the elections with Alternativet and get into parlia ment, I would have to say and do whatever they would want me to. The party had a completely different ideology at the beginning, and then one day they decided to change the course, start to work close to the government, “drink coffee with the prime minister” as they said, and that was unacceptable for me. I entered pol itics to be in opposition, I was there to make changes.

After eight months of being a parliament member for Alternatives, Sikandar left the party and soon founded the new “Frie Grønne” party, with himself as a party leader, becoming the first muslim party leader in the history of Denmark.

I walk to the square in the neighborhood where Sikandar spent his childhood. You can see Sikhan dar’s posters here on nearly every tree, and another candidate’s posters hanging nearby are intentionally damaged. A few quarters away from here someone made a huge Sikandar’s portrait street art.

- He lives in people’s hearts,- Sikandar’s wife says. And you can clearly feel that if you walk with him. Wherever you are there will be a car that will stop on the other side of the street with people shouting out to him. There will be random passers-by who will just stop to hug him, there will be moments when you won’t understand whether he just met his close relative or someone he doesn’t know, who will vote for him in a few days, giving him the mandate to rep resent their rights as minorities, climate activists, or simply as Danish citizens who urge for change.

- Denmark is our society too, we want to be respected, we want to be part of the decision making, not only be tools to run the society. There are a lot of struc tures in society that suppress women, minorities, those are the same structures, they are a part of the system I’ve been fighting against.

At Danish National Radio it is the day of one of the most important TV debates. In this world of white collars you will easily recognize the Frie Grønne team when they enter the room filled with politicians. With their long hair, asymmetric clothes, dark painted nails, funny hand bands, and never a single suit, they look like a group of underdog superheroes that in the end of the movie will unexpectedly save the world. After long preparations with his team, Sikandar joins the other candidates on the stage. He greets all the participants, they chat a little before the debates go live. As natural as it seems, you can still feel tension. It’s hard to lose the feeling that he doesn’t belong here and even harder to identify whether what differs him is his origins, or the way he stands for his ideas.

- I get a lot of threats of all types because of my politics, because of my religion, -Sikandar tells me later, - at one point somebody was taking pictures of me and sending them to me saying that they would shoot me. I’m in constant contact with Danish intelli gent services, I carry an alarm button with me. I have never talked about it in public, as I never wanted to use this to my advantage in politics. After two hours the debates are over, the team leaves somewhat satisfied. Time to get ready for tomorrow.

Today is the last day when something can be changed. We start the morning in the parliament where Sikan dar is recording a speech. Depending on the results of the elections this can also be the last time he enters this hall, but that isn’t said loudly. Next on the agenda is thanking the volunteers for their work, and taking part in another debate.

It’s morning and we are at Sikandar’s apartment. The whole family is here, Sikandar’s parents, his wife and two kids. Sikandar picks up his passport and goes to vote together with his mom. The rest of the day is dedicated to political activism in the streets and basically waiting for the results. The prognosis is not very good but still everyone has a silent hope for a bit of magic. The exit polls say the magic didn’t happen. But when Sikandar enters the place where the Frie Grønne cel ebrate their election party, he is greeted as a Holly wood superstar. Sikandar gives a speech, spends a little time with his party members and dedicated team, even joins the rappers on stage in a small part

of a song dedicated to the Frie Grønne, and then just sneaks out to sit in a calm place and watch the results progress.

- Look at me, I’m not a parliament member,- Sikandar says, - I was 24 hours ago, and now I’m not anymore. A big smile appears on his face, he sits in an armchair in his cabinet, which is technically not his cabinet anymore, and almost looks happy. Sikandar’s political advisor is in front of the computer still looking at the map of Denmark and the small changing numbers and charts near it. Time is a little past midnight. The numbers aren’t final but it’s already obvious that Frie Grønne didn’t get into the parliament.

Mikail climbs over Sikander, laughing so loud and happy as only the smallest kids can laugh. Sikan dar’s mobile phone is on the sofa, trying to grab his attention constantly, but now he doesn’t hold it in his hands as every day before this. Instead he tickles Mikail, laughs with him, rises him high in the air while his dad and wife watch them admiringly from the other side of the room.

- For the past 4.5 years my mornings have been so hectic, and today - today there is nothing. There were a lot of calls of course, but there is nothing in my calendar, it’s empty...it’s so weird.

I ask Sikandar what his feelings are right now.

- I am sad that we didn’t pass, and thankful for all the votes we got, but also I feel a little relief. I have done so much during these years. I stood up against the establishment and did things that no one could ever imagine in the Danish parliament. I gave minorities a voice, I made Denmark talk about racism. Of course, I’m a bit disappointed, too, I’ve spent so much time raising my voice for minorities and they just didn’t go to vote.

- I cried, - Sikandar’s wife says, - politics is his pas sion, and I didn’t want him to lose, also it’s a great honor to be a Danish parliamentarian’s wife but I’m happy we will be able to spend more time together now.

- She has been such a great support for all these years, - Sikandar says looking at his wife lovingly. I’m asking Sikandar what his plans for the future are.

- A lot of people called and messaged me today wanting me to give them a guarantee that I won’t stop in politics. I told them that I won’t, but I need a break to spend time with my family, my kids, my father, at this point I’m very tired, very tired... We will participate in the next municipality elections and I think we will be in the next elections, but it’s in four years, and this one was only yesterday,- Sikandar smiles. The table is set, it’s time for dinner. Today Siddique family will eat “pilaf”, Sikandar’s favorite dish, cooked in his honor. Mikail runs out from the other room, jumps right on Sikandar and hugs him again as if he hasn’t seen him for days.

- He really missed him, - Sikandar’s wife says, admiring the dad who is finally at home.

by Gabi Broekema

by Gabi Broekema

At the age of 15, I was a stereotype. My looks made me fit perfectly as a young, innocent girl. Long blonde hair, blue eyes that popped against my fair complexion and my physique. Tiny, thin wrists, little to no fat on my body. I hadn’t started my period, and it showed. Flat chest and no curves on my hips. I was perfect this way, and I knew I had to keep it. I developed symptoms of anorexia and bulimia because I had to preserve my worth as a dancer; I had to stay in the mold I had put myself in.

My legs and hips were one of the first things that began to grow. I felt the weight bear down on my hips and found it harder and harder to do certain combi nations in ballet class. With each kick and jump, I felt my skin fold around my hips; I felt disgusting. I tried little ‘tips and tricks to lose weight fast,’ before I started throwing up; from those I developed habits that still haven’t gone away. One of the first ‘tricks’ I adopted was a wrist check. It is an irrational concept that you can tell if you are gaining weight or bloated based on if you can wrap your middle finger to thumb around your wrist. A young impressionable version of me took it as gospel. I still catch myself sometimes doing it subconsciously, mainly when I am nervous.

I can’t remember the first time I forced myself to vomit. Vomiting seemed easier to hide than not eating at all. I would pretend to go on a walk after eating which would lead me to the isolated bathrooms in the quiet unoccupied corners of my school. At first, I would only vomit if I ate a large meal or had something extra outside of my planned caloric intake. After my sister left for university, the occasional trip to the bathroom turned into me disappearing after a meal for thirty minutes to an hour. People must have noticed. I told a friend of mine about it. A boy with kind eyes. He would listen with an open mind in all our conversations. But I lied. I said I had dealt with the disorder before when in reality I had probably puked up the meal I had not four hours earlier. Nothing ever came from that conversation, and we stopped talking soon after.

I was living with my mother at the time, and when I told her, she asked if I wanted to see a doctor for it. I said no, knowing it would put a halt on life as I knew it. After that I can’t remember any other conver sations we had on the topic. I can’t even remember how the conversation we had, ended.

On Sundays I found ice cream was one of the best foods to throw up. Every weekend, the cafeteria would have an ice cream bar where you could build your own sundaes. Ice cream was smooth to go down, and nearly smoother to come back up. Any soft foods were best; yogurt with fruit but no granola, plain cream cheese on a blueberry bagel, or a glu ten-free muffin just to name a few of my staples. Protein bars were nice, only I felt as if my stomach absorbed them too fast. The act of throwing up had almost become a habit. Sticking my hands down my throat, to my gag reflex, pulling the slimy acidic goo that vaguely resembled what I had eaten nearly twenty minutes earlier back out of my system. The repeated actions forced my eyes to let tears flow that I hadn’t realized were there. It was my me-time. And for the majority of three years, I walked out of the bathroom with the lingering smell of the chemical cleaners and bile in my nose and an extra pep in my step, feeling lighter and better than if I had the best night’s sleep.

Like the flip of a light switch, I got out. Moved on. I didn’t have a pivotal moment where people found out then I got sent to a rehab facility like what happens in TV shows. I knew this lifestyle wasn’t safe, so when it became time for me to go to university, I took up a new career: photography. The strive for perfection hasn’t left my nervous system. It’s helped me learn to love photojournalism, a career where the idea of perfection is near as unattainable as dance. I would relapse every few months at first. Since there was no need to fulfill the visual aesthetic of a profes sional dancer, I was able to snap out of trying to throw up before I had the chance to make it a habit again, but I still hated my body. I continued dancing with my university’s dance company, but I never felt right in those classes. I hated looking at myself in the mirror during those times: if I had to look anywhere, I would stare directly into my eyes. They hadn’t changed.

I started exercising less and eating more. I felt my body change as I gained weight; I just let it happen. My mood shifted. I hated not only myself but most of the world around me. I struggled through my uni versity years, relapsing whenever I felt as if I wasn’t enough, or I ate too much. I would end up using my expert knowledge of my gag reflex to get copious amount of alcohol out of my body. Each late drunken night over a toilet would lead to a wave of guilt washing over me. I would end up in bed, feeling disconnected from my body, mind, thoughts, everything. Drifting into the empty nothing ness of sleep was the only thing that would keep me from shedding guilty tears.

There were also times I would vomit for no reason. This still happens. I eat and my body either imme diately convulses, rejecting the food or a creeping nausea slowly crescendos till I can’t see straight and after a trip to the bathroom I pass out in bed. These reactions scare me the most. I worry that my body is relapsing and falling into old patterns.

I’ve only recently started looking at my body in the mirror and not criticizing what I see. I know the rea son why, but not consciously. Maybe it’s because I learned there is much more to living my life than my physical form. Or maybe because I found comfort and joy in the hours I’ve spent alone, making myself laugh at the silliest of things. Or because I came to the realization that I decide who I am, not the com ments and criticisms of others. Probably a conglomeration of all three points got me to where I am today. I still struggle, but I accept my past as my own. In a messed-up way, I’m glad for living though my bulimia and anorexia. Living through my experiences built the woman I am today. I know accepting my body for its curves and soft spots is only one step out of hundreds I will take to squash the unhealthy habits that have become second nature to me.

The tiny blonde girl yearning for perfection through the eyes of others will never leave me. She will fade into the background, though.

by Finn Winkler

by Finn Winkler

Elvis Šerifović lost his legs to a rifle grenade when he was a child. Instead of turning bitter, he has found refuge in the challenges of the parasport sitting volleyball.

It is the first day of May in 1998. The civil war has been over for three years and the Šerifović family has returned to Srebrenik only recently after spending six years in Germany, seeking refuge from the horrors in their home country.

The day is a national holiday in Bosnia. The family has planned a trip up the mountain, to see their old house. Afterwards, they want to go to a party. But first, Elvis’ mother has to get something done. She tells Elvis and one of his cousins to wait for her by the car. “Don’t move“, she urges them. The boys are seven and eight. As soon as Elvis’ mother is gone, the cousin asks Elvis whether he wants to try some fruit. Elvis has not tasted this one yet. Elvis wants to try, so they will have to climb up a tree. Afterwards, they sit down beneath the tree to eat the fruit. Behind them, two policemen are talking. Some where near, there is a thing lying on the ground that is somehow shaped like a rocket. Decorated with a red

circle, it is made out of metal and white plastic and there is a screw on it. One of the officers walks over to the boys. He is a Bosnian Serb, but the children do not think about that. Elvis likes policemen, he is familiar with them: His uncle is on the police force, wearing the same uniform. This officer is different, though. He suggests that the boys play with the rocket. He tells them to loosen the screw on it. The cousin does as he is told. What the boys do not know, or maybe do not understand is this: The thing is a rifle grenade. The screw they have just loosened is the safety switch. The police man whispers something in his cousin’s ear that Elvis cannot understand. Then the policeman walks away. The cousin bangs on the red metal dot. Once. Twice. When he hits it for the third time, the grenade explodes. The detonation throws Elvis through the air.

Twenty-four years later Elvis is sitting behind the steering wheel of his blue Skoda, smoking an electric

cigarette. Being in his early thirties, he is a tall guy with the broad shoulders of a bouncer. His hair is short, his beard, too. The car speeds up as Elvis steps on the gas pedal with one of his prosthetics. He lost his legs on that day in May 1998, just like he lost his cousin. Now he is on his way to the training session of his sitting volleyball club. He is the team captain and also plays for the national team of Bosnia.

Sitting volleyball might sound comfortable, like something you can do while drinking coffee. But one should not be fooled by that, playing game can be intense. When the players want to block a ball, they often throw their whole body at it. The field is small, and the ball is fast. Thus the players have only a short time to react. Standing up is forbidden in sitting vol leyball and that makes having legs a disadvantage. It is not surprising that Bosnia is one of the leading nations in this sport. Its national team is one of the top ones worldwide. Many people in Bosnia lost their

limbs in the war, to landmines, but also to gunfire and bombs. Sitting volleyball has become a way for survivors to leave their houses again and connect with others struggling with similar issues.

Dusk has already fallen as Elvis drives his car out of town towards the mountains. From the radio come the wistful notes of a Bosnian pop-folk song. “If love is a sin,” the radio musician sings with some pathos, “then I am a sinner.” From the rear mirror, a small lucky charm is hanging. Beside it, Amir is sitting in the passenger seat. Amir is twenty years older than Elvis, but he feels the same age. And this despite the fact that he has gone through a lot, including being clinically dead. When Amir talks, his voice has a gentle sound to it. Elvis approached Amir to join his sitting volleyball team since he could see they shared the same burden: As a young soldier in the war, Amir lost his leg to a sniper. Now the two men meet every

day for coffee. On the back seat, Albin has joined them. He is a calm man with dark hair and a dark beard. Cancer robbed him of his left leg a year ago. Albin is still new to the team. It helps him in his coping process. The trio cheers and honks as they see a friend on the street, but they do not stop to say hello. They will see him in a few minutes anyway.

The car follows a small road up. It winds through growing hills, passes through several villages, and finally arrives in Štrepci.

Surrounded by deciduous woodland, Štrepci is a small village, located in the District of Brčko. It is somewhat hard to imagine that this picturesque land scape was one of the most important regions in the war. It lay in the “Serbian corridor,” a small stripe that connected the two halves of the Republika Srpska. Elvis parks the car in front of a school building.

On the wall, there is a painting of two little children playing in the sand. And there is a sentence written in Serbo-Croatian: “Not every student has to be an excellent teacher. But he can be a great man.” Almost every Tuesday and Thursday this school turns into the training gym for one of the best sitting volleyball teams in Bosnia: The “SDI Jedinstvo - Boće – Brčko.”

On the official premier league table, they rank as the second-best sitting volleyball team in the country. Currently, they are only topped by the leading team “OKI Fantomi.”

Elvis, Amir and Albin leave the car to take a bunch of sports backs from the trunk. Elvis leads them over a basketball court to a bench. He walks faster than the others, who need to rely on crutches. Elvis and Albin sit down, waiting. Others arrive, dropping in one after another, coming from all over the area.

Inside the gymnasium, Elvis undresses next to Amir. The two men quickly put on their jerseys. Usually, during training, they both play on the same team. This time though, they will play against each other. Elvis unmounts both of his prosthetics and starts warming up on the floor.

The gymnasium of Štrepci is a big hall, with a floor that is maybe not as good as parquet, but better than the rubber floors of other gyms: Those make it harder to move. Up on the wall, there is a banner with the words: “Sports association of the disabled: Jedinstvo - Boće – Brčko.” A small picture of a volleyball is painted on it in the Bosnian national colours, blue, white, and yellow.

A few of the other guys join Elvis. They start tossing a ball between them. The game is still relaxed, the men practice their blocking and rolling on the floor. As soon as the team is ready, the men start playing the real game. Amir’s half in their red jerseys has a good run today, making one point after another. They cheer over their victories. But after the training, all players come to the middle of the field and shake hands.

The next day, Amir and Elvis sit in the house of the Šerifović family. Elvis lives here with his wife Edina and his children, Enes and Medina. Enes is two years old, and Medina is only three months. Even though Elvis usually likes to wake up early, it took him longer this morning. He still is exhausted from the training the day before. When Amir leaves his crutches outside, he has to hop through the room. Enes makes happy noises of excitement and imitates him, making small jumps. Amir smiles and sits down on a sofa next to Elvis. Edina brings coffee and cake. The sun is shining through the windows, they talk about Amir’s grand children. The men rarely discuss what happened to them. Right now they focus on the following weekend, where there will be a match against the team KSO Iskra.

In the break up of Yugoslavia, a war took place in Bosnia and Herzegowina between 1992 and 1995. It started when the Serb population rejected the independence referendum held in the Yugoslav Republic.

In the years to come, Bosnian Muslims, Serbs, and Croats fought each other fiercely. Especially the Serb troops became notorious for committing brutal massacres, systematic mass rapes, and mortar shelling of civilian areas. The war was ended in 1995 by the Dayton Agreement. Between one and two hundred thousand people were killed and more than two million people were displaced, almost half of the country’s population.

Bosnia remains one of the most land mine-polluted countries in the world. And being divided into two big entities, it is infa mous for having an extremely complicated government system.

Source: Wikipedia

by Ahmed Abd El-Gawad

by Ahmed Abd El-Gawad

There are screens in every corner of the room and so many people that they can barely squeeze in. They all focus on a young man wearing a t-shirt with a Tekken logo, who is carrying a tablet with all of the competition results. He calls the players to play against each other and after each game he puts the match results on his tablet.

They all greet each other by fists before the game, showing respect for everyone in the room. Every screen and gaming device is busy.

The co-founder of Aarhus fighting gaming club is Michelle Sørensen. Along with other players from her Aarhus club, she is participating in the`official qualification for Scandinavian countries, which took place in Nørrebrohallen, Copenhagen, on October 29. Michelle is 28 years old and apart from being a gamer she is studying electrical engineering.

She was knocked out after 16 rounds in the competi tion but for Michelle the social aspect is more impor tant than the competitive one. In any competition she looks forward to meeting friends and she does not expect any victory because meeting friends for her is a first priority.

Michelle knows most of the players and she has been waiting for this day to meet her friends from other countries.

In 2017 five people met every two weeks to play Tek ken and they established the Fighting Game Commu nity Aarhus. The club was founded by a few people, but now they are more than 50 members. They meet every Wednesday at Dokk1 to play fighting games together, especially Tekken.

Michelle, who is a former employee at Dokk1, asked the head of the library for a space to meet and play every week. They got a small corner of the library, but they hope to have a private place soon so that they can store gaming consoles and screens. but still, they appreciate the support they have already had from the library.

In gaming, chilling time could be at home alone in front of the screen, but with friends it’s more interesting. Even if you lose, it’s still more fun. The club members meet every week at 4 pm and play, chill and laugh together. Everyone bring their own devices like Michelle, Usually she brings her Playstation and Arcade stick when playing at Dokk1.

The favorite character in Tekken7 for Michelle is Feng Wei, who fights using God Fist Style Chinese Martial Arts, a highly devastating and aggressive style that is equally athletic as it is powerful.

Tekken was not originally conceived as a fighting game. The project began as an internal Namco test case for animating 3D character models. As with many fighting games, players choose a character from a lineup and engage in hand-to-hand combat with an opponent. Traditional fighting games are usually played with buttons that correspond with the strength of the attack, such as strong punches or weak kicks. Tekken, however, dedicates a button to each of the four limbs of the fighter. The game play system includes blocks, throws, escapes, and ground fighting.

After the competition at Nørrebrohallen, they all gather in a gaming bar on Halmtorvet, Copenhagen. Michelle and her friends enjoy playing together, and it seems that they can’t stop. The best result for the club members was that they reached the quarterfinals of the tournament, but everyone was enjoying just being a part of the competition. For Michelle the hardest thing was watching close friends play ing against each other. She knows that one of them will always lose and be sad. But that is what it is like when you are fighting friends.

Victor and Aajo moved together from Greenland to Denmark in search of a better life. Three years on, they are still searching for a better life. Together.

Victor sleeps with his clothes on at the foster home. He doesn’t take off his hoodie, his trousers, or his socks. Sometimes, he runs away from that place.

From “maani ajorami”. When he cries, asking his mom to bring him back home, he repeats this term, which translates to “it is bad here”.

This is what Aajo, Victor’s mother, says about the way her son lives right now. Aajo Markussen decided to move to Denmark in 2019, concerned about the conditions of her son’s life in Greenland. What she wasn’t expecting was that she would end up living alone most of the time in this new country.

Being a 39-year-old single mother and a soon to be social education student, she moved from Ilulissat to Aalborg with her youngest child, Victor, a 13-year-old that was born with brain damage. It was only the two of them, but they were excited to start a new life together - a better life.

“My special kid”. This is how Aajo presents Victor to me, with a doubtful expression probably related to the wonder of whether I knew beforehand how her son is. They hug and he enjoys it in the most implicit way. A mix of dependance and teenage embarrass ment. He wants to be profoundly close to her, but people don’t need to know.

Victor is staying one week in the foster home, and one week at home with his mother. This week he is at home, in the small apartment that looks cozy and Danish, except for the relatively big picture hanging above the TV - a photography of the family’s home town back in Greenland. A Danish flag held from a stick lays on the TV table.

Aajo is happy about how fast she has been reached out to in Denmark.

“Since I got here, I have received a lot of help and attention”, she says. However, not all this help has come in the form she would have wished for. One year ago, Ajo says, Aalborg Kommune decided that Victor couldn’t live with her mother anymore.

According to Aajo, one of the social workers told her that she should sign the papers that give the permission to take her child into custody for some time, assuring her that she could resign from that at any moment, no attachment.

“They said it was a temporary thing, while I was looking for the right kind of help for Victor. I believed them, and after that, they didn’t let me get my kid back anymore. Now they ask me to do so many things and go through a long process before I can live again with my son.”

Victor and Aajo have been recieving the help of Najannguaq D. Christensen, a member of Mentor Immanuel, which is an organization that helps vulnerable Greenlanders living in Denmark. She has been advocating for Aajo and reminding her of her rights.

Najannguaq’s research for Aalborg Universitet shows that the rate of Greenlandic children put in out-ofhome care is twice as high as the rate for Danish kids.

Aajo wants to take her son back home again, not only because she misses him and is convinced that she

will be able to take good care of him, but also be cause she considers that the foster home Victor is staying at an unsafe place for him.

She shares that the place is mainly for teenagers, whereas Victor cognitively operates as a 3-year-old kid. Also, as she puts it, the interns at the foster home count with a wide range of handicaps such as ADHD, resulting in a very hard environment for Victor, who has to witness aggressive scenes.

In the beginning, mother and son could only see each other every other weekend or every other Thursday. But from December 1, Aajo will be allowed to stay with Victor for 10 days, and then have him out of home for 4 days.

To the question of whether she thinks she will be living with her son full time one day, Aajo answers that they are getting there progressively. Step by step. Slowly creating a new life together - a better life.

Nighttime coats the woods in a thick black veil. Far from traffic and people, Rendlesham Forest is a large woodland area on the south-east coast of England. The monotony of the dark foliage is only broken up by the occasional path and signage. In a small clearing, deep into the forest, stands a large diamond-shaped structure, made entirely out of metal. Even in the dark, the stars provide enough light to cast a light shadow underneath the objectit seems to be quietly hovering a few inches off the ground. It is the Rendlesham UFO.

The UFO is only a monument, raised to commemo rate a sighting that took place there in late December, 1980. Leutenant colonel Charles Halt of the U.S Air Force reported seeing a glowing metal object with coloured lights flying through the trees. A report was filed, but the British Ministry of Defence regarded it as a non-threat, and some still find Halt’s reports to be inaccurate and false. In 2010, Halt stated he still believed the event to be extraterrestrial in nature.

The subject of UFO’s has held a strong position in popular culture ever since the 1950’s. However, for some it is not just limited to the world of fiction - they strongly believe in the existence of UFO’s, and perhaps even extraterrestrial life. Amongst the believers are those who have had what’s called “experiences”; sightings, abductions, commu nications and even relationships with UFO’s and aliens. Over half the world’s population believes in the existence of intelligent life out somewhere in the universe - yet those who believe that such intelligences have made contact with Earth are branded as crazy, attention-seeking or mentally ill.

U.S Intelligence revealed last year that out of 144 UFO reports logged between 2004 and 2021, only one could be explained. But interest in UFO’s is not limited to the US - some databases report between 420 and 450 annual sightings in the UK. It is estimated that there are about 15 active UFO groups across the country. Are we not alone, after all? And perhaps more importantly: how do we treat those that believe we’re not?

Under the dim interior lights of a local pub, in between loud conversations and shouts directed at a televised football match, members of UFO Identified are holding one of their semi-regular meetings. The slightly sticky wooden table is occupied by pint glasses, documents and dark grey manila folders. After the meeting, they will head out to hold a “skywatch”an activity where they gather and observe the skies, in the hope of seeing something note-worthy.

Ash Ellis, a soft-spoken Mancunian, founded the group in 2020 to collect UFO sightings, compile research, and publish reports and articles. Their website shows a large amount of news articles where they’ve either featured themselves or helped out with data. Ash has always been interested in UFO’s - he reminisces back to his teenage years, when he would take all the books on UFO’s out from the school library and read them in a corner.

The group’s research maintains a critical eye, and does not accept every sighting as UFO-related. While 99% of the reports they receive are easily explained, they live for that one percent where there is no logical or scientific explanation. There are numerous Facebook groups filled with anecdotes, videos and pictures that adamantly claim to prove the existence of UFO’s. Most of the time these are easily explained, which some don’t take kindly to when pointed out.

“Some people believe anything, and then you’re the bad guy for saying they’re wrong”, Ash laments.

“People today are not expected to think for them selves.” Steve Yarwood is another member of UFO Identified, and has been researching UFOs for almost 50 years. His comment reflects an essential part of the group’s interest - challenging established truths and questioning widely accepted answers. Thinking for yourself is one of the most important aspects of UFO research.

After the meeting the group exit the heat and the loudness of the bar, and enter the cold and quiet of the outdoors. They head towards a small park area for their skywatch. Rain is pouring down, and a grey layer of clouds cover the darkening night sky, but this does not seem to dampen the group’s spirits. The group trudge across wet grass, and place their camping chairs in a straight line facing the river Mersey. With eyes fastened on the sky, the conversations from the bar continue. Some brought snacks, which they happily share.

The skywatch is more about being together and sharing stories than anything else. Having a UFO experience can be life changing, but it can also be difficult to talk about it openly. Knowing everyone believes makes it easier for the members to openly discuss and share their stories.

“I’ve just met these guys,” Ash says and points towards some newcomers, “but I could totally tell them all about my experience and not worry.”

On an early November morning in 1980, policeman Alan Godfrey was out checking on reports of cattle wandering around a local estate in the small town of Todmorden, half an hour by train north of Manchester. He looked up and saw a bright, diamond-shaped light above the road ahead. Suddenly the light dis appeared, and Alan found himself several meters further down the road. Looking at the clock, he saw that about thirty minutes had passed. Thirty minutes

which he could not account for. His story went around the world, covering the front of newspapers everywhere as Britain’s first UFO abduction case.

A grey layer of fog coats the hills surrounding Tod morden. It is a quiet town, with simple Neoclassi cal architecture. Right by the train station is a small second-hand bookshop, filled with everything from comics to rare art catalogues. The impressive col

lection is stacked in piles, stuck in between skewed shelves or placed on the floor. The overcast midday light leaks into dark corners, and in one of these corners sits shop owner and visual artist Colin Lyall.

Colin does not concern himself much with traditional research and evidence.

“There is no point looking for answers,” he says. “because there are no answers out there”.

To him, the personal accounts matter much more than evidence. Colin had his first sighting in 2016, seeing a metal object in the sky that stood com pletely still.

“It affected me deeply. I felt a connection, as if the object saw me as much as I saw it.”

Colin Lyall also hosts Todmorden’s now-famous monthly UFO-meets. The meetings are held on the first floor in a local pub, in a room overlooking the River Calder as it slithers out from underneath a bridge. A dusty black and white tiled floor precedes a small elevated stage, where regular live music and comedy shows are held. A pale light shines through deep red curtains. Picking up a stool, Colin sits down

in the middle of the empty room and looks around. People from near and far come to Colin’s meetings to share their stories without the fear of being ridiculed or judged. Everyone is welcome to these cathartic gatherings, even the most adamant skeptics. In a way, it is more akin to therapy than anything else. No wonder, as Colin is a licensed psychotherapist. “Some people have held on to their experiences for years, afraid to share them with anyone,” Colin says. He mentions one particular case, where a woman kept her encounter a secret for over 30 years, even from her close family.

Some say the pilgrimage to Todmorden is a calling - that they’re meant to be there, that they’re being sent there. The numbers vary, but usually 20-50 people come to these meetings. Colin sets no specific agenda or plan, but takes it as it comes - whatever comes through that door, he has to work with. With its open door policy, mixing skeptics with believers can sometimes cause friction. Colin says his role can often be that of a mediator: “Some say it’s the greatest feat of diplomacy ever achieved,” he laughs.

“If you start looking into it, you will never look at the world in the same way again,” says Dave Hodrien, before taking a bite of his chicken korma. It is late afternoon in a local pub, and he has just finished his talk at a UFO and paranormal-themed conference in Blackpool. He presented his organisation, Birming ham UFO Group, to an audience on the edge of their seats. Murmurs and low gasps spread across the room when he showed a video recording of an alleged abduction.

Dave is a data engineer during the day, doing his research during the late evening when his wife has gone to bed. He became a UFO investigator in 2007, and quickly rose through the ranks to become the group’s chairman in 2009. Whether people care or not does not matter to Dave, as he believes it goes over most people’s heads anyways.

What he doesn’t like is when people joke about it. He says some people have been deeply affected by their UFO-experiences.

“I’ve seen families torn apart by this,” he says. Other members of the group have lost their jobs after opening up about their experiences.

Finishing his drink, Dave exits the pub, heading out into the fading dusk light. He needs to get home, he has work in the morning. The dim fairy lights around the outdoor seating create small glowing orbs over his head as the wind blows. He stops to exchange a few words with some attendees from the conference before leaving. There is no doubt that Dave is keeping busy. But this is a labour of love, and he’s not plan ning on stopping anytime soon. “I’ll never grow tired,” he says.

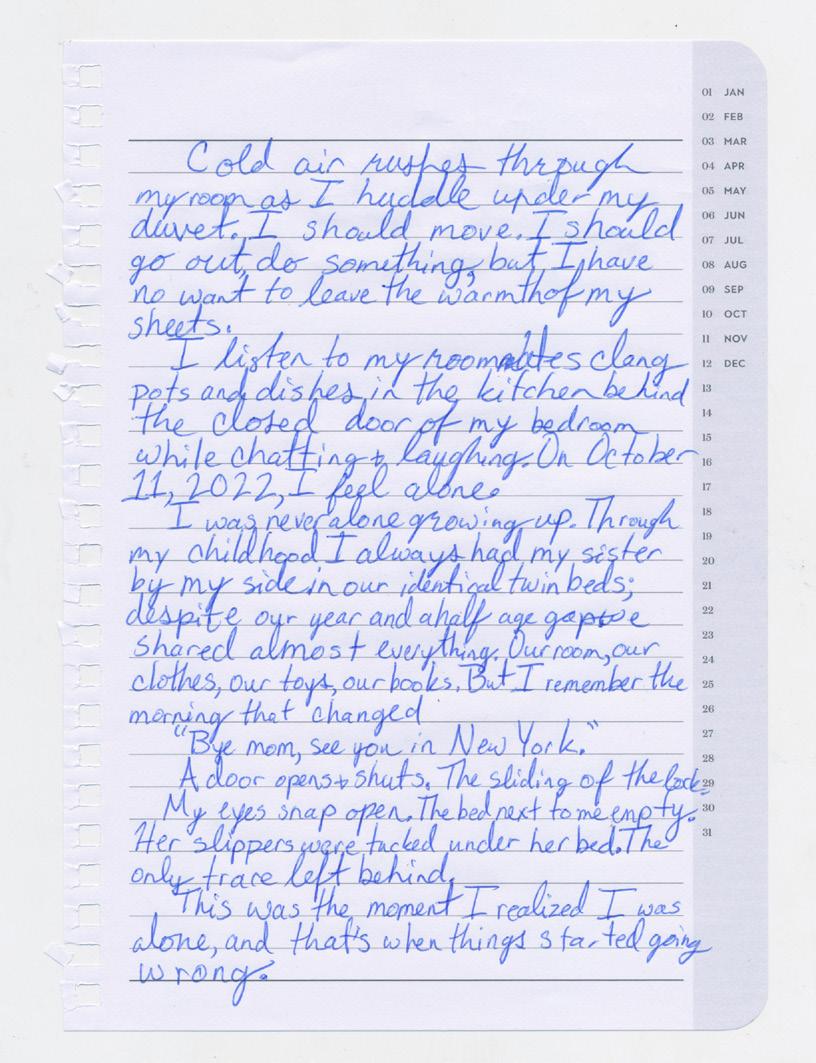

12.09.2022

The days are getting smaller. It’s getting colder. Everyone has been telling me it’s nothing compared to what’s coming in the next months. I hate that. I am coughing a little bit, have a sore throat. Hope it’s only because of the constant smoking, and not the weather. God, I hate it here. I’ll call Pavel in a bit, see what he’s been doing.

16.09.2022

Yup, it’s definitely the weather all right. Got fever now, too. Went out to Gellerup to find something to shoot, got back with nothing but a high temperature. Just my luck. And now my dormmates have thrown a party in the living room and it’s banging in my head. I just want to go out and scream at them to shut the hell up. But also wishing I could join them. I haven’t met all of them yet. But I don’t want them to feel weirded out by my sickness either. I don’t want to be a burden. If only they would keep it down a little bit! Can’t even go out to the kitchen to get some food. I don’t want them to see me like this. Will have to make with the chips that’s in the drawer.

21.09.2022

Just finished talking to Maa. She is so worried. I hate making her worry so much, especially when I am so far away. I wish she was here - I miss her, I miss her hugs, I miss her fussing over me, I miss her cooking. Haven’t had anything good to eat in days now. Have to pull myself together though, have to find the strength. We’re going to Copenhagen to morrow, and I don’t want to miss that at any cost.

28.09.2022

The fever is back. Haven’t left my room in a while. I hate this weather! What is it with the constant gloominess? Urgh! I miss my first month here when the sun was shining for most part of the day. It is so silent, all the time. The only sound is when someone comes in or goes out the front door. Sometimes I hear someone cooking in the kitchen, being all loud and happy. Can you give me some of your joy, ‘cause I just can’t take it anymore! I hate cooking with people around, so I normally wait till everyone else goes to sleep. Almost running out of food too, but that’ll have to wait.

03.10.2022

Everything is really taking a toll on me. The fever comes and goes, can’t even take antibiotics anymore. Already finished one course that first week, don’t want to run out in case I need them later. Missing classes too. Everything is piling up. Don’t even feel like getting up from bed anymore. What am I doing here? I just want to go home.

06.10.2022

Just woke up. It’s dark outside. What time is it? What day is it? Everything is just an endless conti nuity. Don’t feel like getting up. What’s the point of it anyway? Checked my phone. It’s almost three at night. When did I fall asleep? Didn’t even turn off the light. Even that dim yellow is so depressing! Friends are reaching out through texts, trying to figure out if I’m okay. Don’t feel like answering them. How can I explain to anyone what this empti ness feels like? I’ll just sleep some more.

10.10.2022

The sickness has left my body, but not my mind. Was talking to Pavel earlier. He told me to “snap out of it, get up and go out”. It’s truly unbelievable that after six years of our relationship, how he still doesn’t understand that I just can’t do that even if I want to! At one point of our conversation, I started crying and hung up. This void inside me is becoming unbearable now. I miss home, I miss my friends. I wish I could just get my hands on some weed. May be that would make me feel better, even if just for a little while. I have that bottle of wine though, probably will just finish the entire thing tonight instead. Don’t feel like eating anything anyway.

13.10.2022

Got the news today that Sami has passed away. It’s for the better, I know. But I can’t help but feel guilty for not being near Rafi and their parents right now. I called Pavel, told him to go see them.

I wish I was there though. Sami was my age, but he has suffered from Cerebral Palsy his entire life. Of course it’s for the better, not just for him but for his family, too. But then why am I feeling like this? I just can’t stop crying!

15.10.2022

Days have become weeks. Everything in my room stinks of smoke. Haven’t even opened the window in God knows how long. Today I have to go out and get some warmer clothes. I am so hungry right now, but I think I’ll eat out today. Maybe splurging a bit will take my mind off things. Yes, let’s give that a try. But first, I should take a shower.

18.10.2022

I have been drinking too much the past few weeks. I should stop. Is this how people turn to alcoholism? On the weekends I have been going out to shoot, trying and failing miserably, and then for the rest of the night sitting at a bar all alone and drinking till the last bus. But I have to stop now, it’s about time.

20.10.2022

It was sunny today, after days of constant gray. I decided to head out to the city center, and just roam around. Went by the harbour and sat by the water for a while. It made my day better. And then while heading back, I saw that the church was open for visitors, too. Went in and I was in an entirely different world. Wish someone was there to share the moment with. Oh well, it was nice nonetheless.

Depression or Major Depressive Disorder is the leading cause of disability in the world. An estimated 3.8% of the population worldwide (approx. 280 million) are affected by it, and is more frequent in women than in men. It lingers on for at least two consecutive weeks, and interferes severely with one’s everyday life. The most common symptoms of depression are sadness, loss of interest, change in appetite, sleeping disorder, fatigue, difficulty in concentration, rest lessness or slowness, feeling worthless and guilty, and thoughts of suicide. Having at least five of these symptoms qualifies for a diagnosis of depression. Fortunately, it is treatable with medication and therapies. There is no one reason for depression, however it is influenced by a complex interaction between genes and environment. Because the symptoms are intangible, it is hard to diagnose, and one can go on for years with their depression before seeking any kind of help or treatment.

I myself have suffered from depression almost my entire adult life. One month in at Aarhus, I started struggling with the bitter weather, caught fever and a cold and was bound all alone in my room for days on end in a foreign country. This is what triggered me, and bouts of depression have overwhelmed me for weeks since then. Unfortunately, depression is quite typical, especially in my home country Bangladesh, where more than sixty percent suffer from it. Only very rarely are these people being treated for it. Even though both my parents are doctors, they never gave any importance to it and expect me to “get over it” every time I start suffering. For me, it always helps talking and meeting the people close to me and going outdoors to places I like. But still it takes a while to overcome, and almost always takes a huge toll on me.

Top, left to right: Finn Winkler, Gabi Broekema, Juha-Pekka Huotari, Núria Sanz, Sindre Deschington

Bottom, left to right: Sonja Smalian, Hilma Amanda Toivonen, Biayna Mahari, Ahmed Abd El-Gawad, Mehbuba Mahzabeen Hasan