18 January 2024 - 25 August 2024

This publication was issued in conjunction with the exhibition Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather (18 January - 25 August 2024) curated by the DMU Museum, Leicester and in partnership with the Museum of Leathercraft, Northampton.

Copyright © 2024 De Montfort University.

All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced without the author’s permission.

The imagery for this publication was provided by Paul Read Photography and was designed by the DMU Museum. Printed and bound by DMU Print Services.

2

3

4 CONTENTS 6 FOREWORD Associate Professor, Enterprise Gillian Proctor 8 A LEGACY IN LEATHERCRAFT Museum of Leathercraft Objects Showcase 6 PEDAGOGY Dr Mary O’Neill 10 STUDENT SHOWCASE 22 FUTURE OF ARTIFACTS LIVE David Barrow, Director of Board of Trustees 30 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Associate Professor, Enterprise, Gillian Proctor

5

FOREWORD

GILLIAN PROCTOR

Associate Professor, Enterprise

Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather Project Instigator

6

The last decade has seen an exponential rise of interest in archival collections and their integration with contemporary design and art solutions.

Artifacts Live is a unique collaboration between the Museum of Leathercraft Northampton and De Montfort University Leicester to consider items of invaluable heritage. Their cultural, social, and aesthetic contributions, together with the traditions of hand manufactured skills long established within the leather industries, should be celebrated.

The aim was to devise proactive methodologies and achieve innovation.

Primarily a student-based initiative, the project incorporated research, sustainability and a focus on technologically directional solutions, which challenged conventions and presented new contemporary aesthetic outcomes.

The Museum of Leathercraft was founded in 1946 and has proven to be a remarkable repository of leather. The collection, which comprises of 30,000 objects, is a carefully selected representation of the leather industry. It spans across five millennia and showcases a treasure trove of internationally important items. The collection embodies the ‘last gasp’ of collecting culture which began with the 18th century Grand Tourist: fragments of the Dead Sea

scrolls, a rare 9th century Qu’ran, ancient Roman shoes, a 5,000-year-old Egyptian loincloth as well as items of Royal provenance going back to the 16th century.

It represents a wealth of social history, culture and inspiration to a variety of interests and covers decades of style, taste, aesthetic and technical emergence.

I initiated the idea for the ‘Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather’ project in response to a challenge to digitise the idiosyncrasies of the unique collections held by the Museum of Leathercraft.

Focusing on Fashion & Textiles and Arts, Design & Architecture courses, students were invited to apply to the project as an alternative to final year degree submissions.

Introducing an opportunity to combine specific research and approach methods, participants were asked to begin the project by working in pairs on a cross disciplinary basis. This professional practice challenge was intended to help students compare and consolidate research and initial interpretations of the artifacts. They were then asked to work independently and express their individualism.

Together with the DMU Museum Curator, Elizabeth Wheelband and the Museum of Leather Curator,

7

Graham Lampard, we chose twenty artifacts which reflected a wide range of heritage in leathercraft.

Students were asked to select two of these objects as inspiration and begin a systematic study of their application, including historic and cultural significance, and traditional crafting methods.

Additional support was delivered via Senior Lecturer Chris Wright in the Drawing Centre to inspire initial visual research, as well as realise concepts as they began to emerge.

Through their personal research, the students learned how to translate and emulate the various hand skilled techniques that were originally used to create the artifacts. They were enthusiastically supported by the excellent technical support staff across the ADH faculty and by Dr Mary O’Neill, Programme Leader for Fine Art.

The university is committed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, which was an essential factor to the project. Students were asked to consider end of life, deadstock, waste, offcuts and recycled leather via existing products, excluding exotic skins and faux leather as they were not deemed acceptable. The wider Leather Industry generously supported the project in donating or offering discounted real leather.

Our next visit was to Pittards, one of the UK’s longest established tanneries based in Yeovil, Somerset. Students were able to appreciate the heritage of the company as glove makers to royalty and later suppliers of gloves to the military. They Session delivered to students by,

Through the kind sponsorship of the Company of Leathersellers the students embarked on a leather tour in January 2023, beginning with a visit to Bill Amberg’s studio in London, the UK’s leading architectural and interior leather designer. This was an opportunity to see skilled, bespoke, leather production first-hand, showcasing a wide range of techniques using leather as a workable material.

8

Bianca Farbey of Walter Reginald

experienced the contemporary leather manufacture process attuned with the centuries old hand skilled techniques of stretching skins over wooden rollers.

The final stop was Mulberry, bespoke bag makers on the outskirts of Bath. Through their contemporary workshop directives, and rolling production lines, students were able to witness the entire process from design to manufacture and finish. Mulberry’s impressive restoration unit proved fascinating to all; its where existing Mulberry bags can be restored, revamped and repurposed in line with their sustainability drive.

The tour proved to be the inspirational launchpad to establish a team approach for research.

Utilising DMU’s workshops in industry leading technologies, students were to consider the outcomes of their pieces, whether they were to be worn, carried, or stand as an art piece. They had access to a range of technology available on campus including 3D printing and scanning, laser cutting, moulding, embossing, VR, photographic applications and more.

‘Artifactors’, as the student came to be known, were challenged to consider emerging product and wearable technologies inspired by their selected artifacts and research.

The individual creative solutions of the students alongside the original inspirational artifacts are showcased in the ‘Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather’ exhibition at the DMU Museum.

Over the duration of the exhibition, a series of leather related activities are hoped to go ahead such as ‘In Conversation’ industry talks, restoration roadshows in collaboration with the Leather Conservation Centre, skill-based leathercraft short courses, and events delivered in partnership with Leicester City Council supporting creative education of all levels and age groups. The history of leather is multi-cultural and we hope this exhibition and the subsequent outreach will invite the diverse communities of Leicester to

9

Leather samples showcased by Bianca Farbey of Walter Reginald

discover the world of leather.

The next stage for Artifacts Live is to continue promoting the project initiatives and explore potential commercial endeavours of the artifacts with the Northampton Museum and Arts Gallery, who will care for Museum of Leathercraft collection from January 2024.

Discussions to review how museum collections are made accessible, factual, innovative, inspirational and a standout will certainly evolve.

There is a growing demand for digital enhancement within the wider creative industries, youth culture, universities and museums, an area where DMU already has a significant lead. For example, the Knowledge Transfer Partnership scheme offers the opportunity to focus on artificial intelligence or virtual and augmented reality, securing the digital future of the collection.

As well as offering a non-invasive way to view the collection, digital technologies enable us to digitally restore objects and showcase how they once looked. This could generate new potential directives. For example, the Ham House leather wall panels within the collection could be digitally projected into their original location and inspire commercial routes to market and generate a revenue stream for the collection.

Artifacts Live featured in two papers at conferences in 2023. ‘Creative Encounters with Design Heritage’ was delivered by co-authors Museum Curator, Elizabeth Wheelband and Dr Mary O’Neill at the ELIA Academy, Evora, Portugal. ‘Shaking the Archives: Reconsidering the role of the Artefacts in Contemporary Society’ was delivered by myself and Dr Mary O’Neill at St Margaret’s University, Edinburgh.

Furthermore, Arts, Design & Architecture student Nik Trzcinowitcz collaborated with Dr Mary O’Neill to produce a film showcasing the Museum of Leathercraft, which provides a stunning and lasting memory of that stage in its story.

The Artifacts Live project has further exciting phases of development planned, expanding accessibility and showcasing this glorious insight into the life and works of leather.

There is far more to come.

Associate Professor, Enterprise, Gillian Proctor, Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather Project Instigator.

10

11

PEDAGOGY

DR MARY O'NEILL Associate Head of School of Art, Design and Architecture

DR MARY O'NEILL Associate Head of School of Art, Design and Architecture

12

In 2022, I assumed the role of Academic Lead for Artifacts Live: A Legacy of Leather. Our exploration into the world of leathercraft began with student visits to three distinct sites of leather production and utilization: Bill Amberg’s Studio, Pittards Tannery, and Mulberry’s factory. At Pittards, students gained valuable insights into the labour-intensive processes that transform raw hides into exquisite gloving leather. This experience shed light on why a by-product of the meat industry, often obtained inexpensively or even for free, can ascend to the status of a luxury material.

A visit to Bill Amberg’s Studio showcased the boundless creative potential of leather as a medium. From carving and shaping to moulding, painting, dyeing, bonding, and stitching, the studio illustrated the versatile artistic expressions achievable with leather. The final leg of our journey took us to Mulberry, where students witnessed a high-end production line and the meticulous refinement of a crafting process that culminates in the creation of iconic handbags.

Our engagement with the Museum of

13

Leathercraft objects at the DMU Museum, served as a pivotal point for the students. Their initial reactions mirrored our own awe when first encountering these artifacts. In a hushed silence, students navigated through the collection, initially uncertain where to focus their attention, only to gradually hone in on specific items, documenting their observations through notes and photographs.

The museum team, led by Elizabeth Wheelband and Steven Peachey, provided the students with a "handling session," imparting essential skills for conducting primary research in an archive or museum. This access, typically reserved for curators and researchers, empowered students to delve deep into the objects' social and historical

contexts, as well as the techniques employed in their production.

While the students were adept at visual research for their regular course projects, Artifacts Live demanded a heightened level of investigation. Over six months, the group cultivated sophisticated primary research skills. Technical research involved reverse engineering objects, discerning the traditional skills necessary for recreation, and exploring the potential application of new technological solutions to various techniques. The project not only broadened their understanding of leathercraft but also honed their abilities to conduct comprehensive and nuanced academic and creative research.

14

15

A LEGACY IN LEATHERCRAFT

MUSEUM OF LEATHERCRAFT

Objects Showcase

16

17

EGYPTIAN LOINCLOTH Thebes, Circa1500 BC

Dating as far back as 5000BC, the most common examples of leathercraft in Egypt are seen in shoes and sandals. However, leather was also used for clothing such as cloaks, caps and loincloths.

Leather loincloths became popular in Egypt in the New Kingdom (1550BC – 1069BC) and were typically worn by men – specifically

soldiers, craftsmen and captives. The purpose appears to have been to protect the wearer and his linen loincloth from excessive wear.

The examples on display here are thought to be made from gazelle hide.

18

19

SHADOW PUPPETS

Javanese, Unknown

Developed in the 10th century, shadow puppets are a traditional form of play originally found in the cultures of Java and Bali in Indonesia.

They use the shadows thrown by puppets against a translucent screen lit from behind.

This shadow puppet set represents a ship with rowers used in the show 'Wayang Kulit’ and is made with raw buffalo hide painted in gold and vibrant colours.

The medium of shadow puppetry is seemingly a metaphor for the human soul, where designs and colours symbolize the character’s inner qualities.

20

STRONG BOX

French, 15th century

A strong box, or forcer box, served as a secure container for storing valuables and featured a robust locking mechanism to deter theft.

Nobility, merchants, and individuals of means used strong boxes to safeguard currency, jewellry, legal papers, and other valuables.

This version is made of elaborate protective ironwork and covered with tooled leather.

21

GENTLEMANS' GAUNTLETS

English, 16th century

Gauntlets, or protective gloves, date back to ancient times. Initially designed for hand-to-hand combat, they evolved from simple leather to intricate metal constructions in the middle-ages.

As firearms emerged, gauntlets adapted to new weaponry and become ornate symbols of status.

By the 16th century, gloves were an expensive luxury item and were richly decorated with jewels, embroidery, lace and were event scented.

This pair is made with buckskin and embroidered with silver gilt thread and lined with plum coloured silk. Stylised flowers such as these were typical of English Renaissance art.

Gauntlets also played a role in social life as it was common to exchange a pair for payments, bribes or even gift as a token of love. Alternatively, if the wearer was to ‘throw down the gauntlet’ and toss a glove at an opponent during an altercation, it was a challenge to a duel.

22

23

24

MANDOLIN CASE

Possibly English, 17th century

A mandolin is a small stringed instrument which evolved from the lute and was brought to Europe in the 13th century. This case was shaped out of sheepskin to protect the instrument whilst travelling.

25

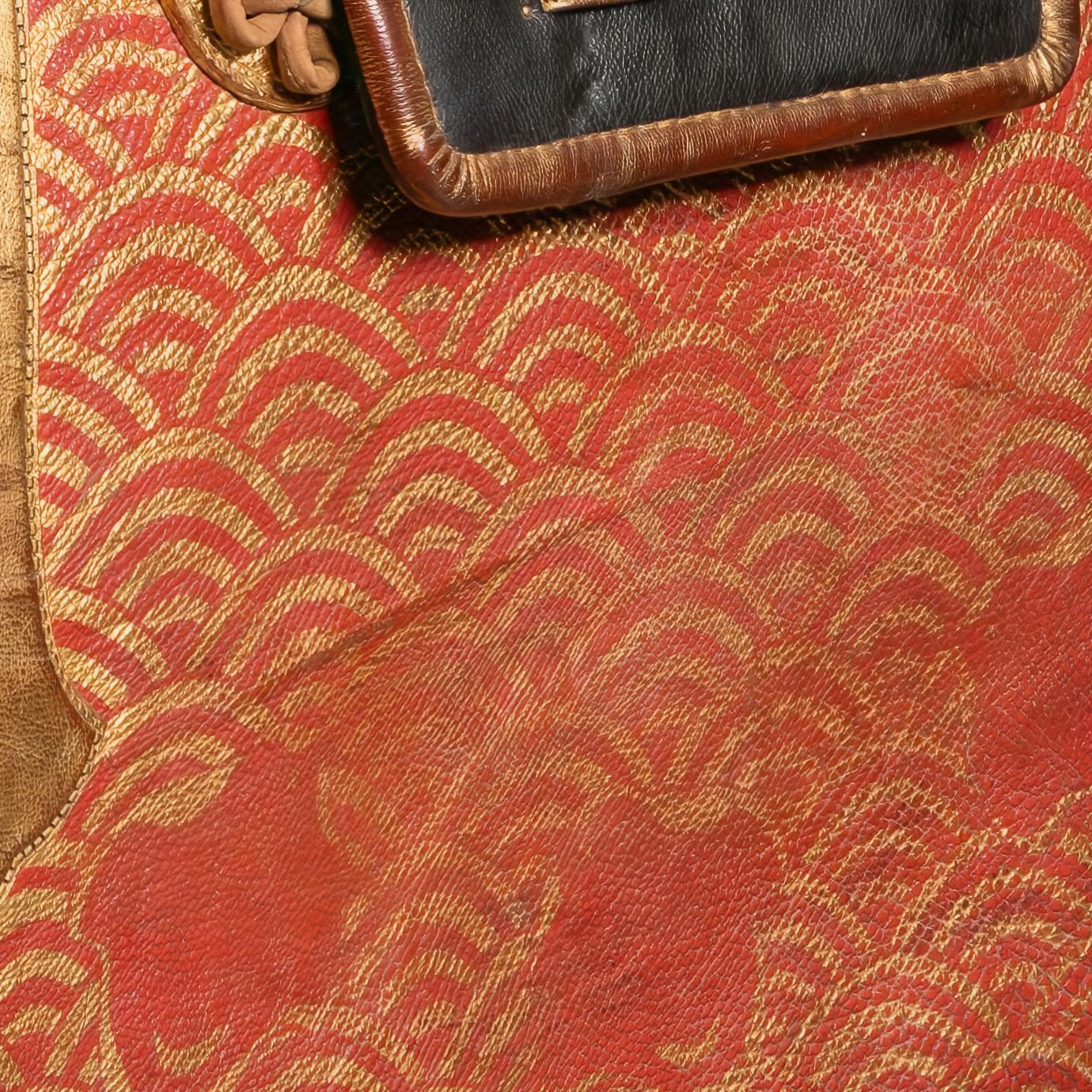

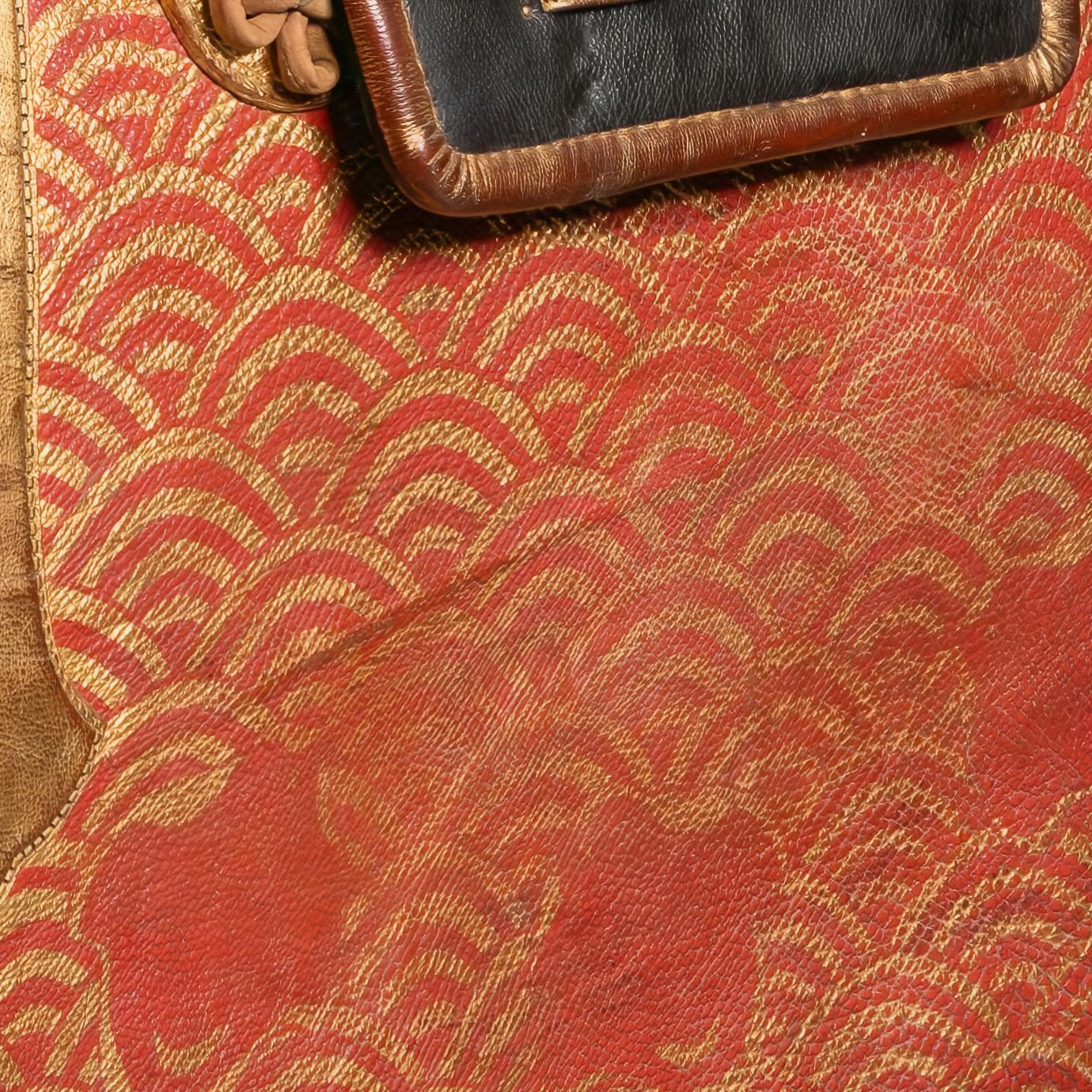

SAMURAI ARCHER SADDLE Japanese, 17th century

On horseback, the main weapon of a samurai warrior was the bow and this type of saddle, or Kura, provided a stable and comfortable platform for shooting arrows.

Kura were made using only four skilfully crafted pieces tied together with leather lacing and decorated with intricate designs.

This example is constructed using red lacquered wood and leather.

The sides are designed with the Seigaiha wave, an ancestral Japanese pattern. This first appeared in the 6th century to illustrate seas and oceans on maps, but later symbolised power.

By the 17th century, Kura were mostly ceremonial and highly decorated with coloured lacquers, intricate inlays and leatherwork.

26

27

WIG STAND

French, 18th century

From the late 1600s, wigs became an integral fashion accessory worn by both men and women in Europe. Symbolising status and sophistication, these elaborate hairpieces were crafted from human or horsehair and powdered to achieve a distinct, whitened appearance.

Although wigs are often associated with the flamboyance of aristocracy, they also served a practical purpose in a time where personal hygiene was challenging.

Varying in style, the wig industry thrived with wigmakers, known as peruke makers, creating intricate designs tailored to individual taste. This leather covered form was used by a mobile wigmaker and would have stored tools, pins and materials need for their work.

28

LANTERN

Unknown, 18th century

An early hand held torch, the lantern separates in two revealing an inner section with candle holder on a wood base covered in leather.

The leather handle would have helped to prevent the user burning their hand. This example features a hanging-loop suggesting it was fixed to a carriage.

29

DECORTATIVE BOX

Indian, 18th century

This box of strong Persian influence is made entirely of leather.

The outside is covered with a black goatskin leather and the inside is lined with red leather goatskin.

The pattern is made with a fine embroidery, possibly using goose quill.

30

31

FOLDED HAND FAN

French, 18 th century

In the 18th century, fans reached a high level of artistry and were made throughout Europe by dedicated craftsmen. Most were produced using silk or parchment and were decorated and painted by artists.

This one is unusual as it is parchment covered in chicken skin, with a classically painted design depicting scenes inspired by the Grand Tour.

Hand fans signified social standing, so the owner of this piece wanted to make a bold statement with such individuality.

Fans also had their own form of non-verbal communication, known as fan language. In a time where it was scandalous for an unmarried woman to speak with a man unchaperoned, fans were a discreet tool used to express feelings or signal intentions, allowing individuals to communicate subtly in a social setting.

32

33

VENETIAN GONDOLA CHAIR Italian, 18th century

This sculptural chair was made for carrying on a platform, with an eggshaped seat and splayed feet to help maintain stability.

The chair is covered with goatskin, silvered and painted with floral designs of Eastern influence and decorated with dramatic brass stud work.

34

35

POSTILLION BOOTS WITH SPATTERDASHES

English, 1790-1800

A Postillion was a man who rode one of the two horses that pulled a travelling coach.

Before the days of railways, ‘posting’ was the best method of transportation across England and the Continent.

Postillion’s wore a specially designed boot made of iron and tarred leather to prevent injury if a leg became caught between the two horses whilst riding.

Spatterdashes were leather accessories that covered footwear, the instep and ankle to protect from water and mud.

36

MOCCASINS

North America, 19th century

Moccasins are the footwear most often associated with Native American tribes indigenous to the North American region.

They traditionally refer to a shoe with a puckered u-shaped “vamp” over the instep and are often decorated with elaborate embroidery and beading.

Made from tanned deer, elk, or moose skin, soft sole moccasins, such as this pair, were common in the Eastern forests. They were flexible and constructed to protect the foot whilst allowing the wearer to feel the woodland ground.

37

HORSE HARNESS

Bavarian, 18th century

18th century horse furniture showcased the aesthetics of the time, combining functionality with an appreciation for design and craftmanship.

Military equine equipment often reflected the rank, social status and wealth of the rider, with

officers and cavalrymen adorning their horses with intricate decorations.

This ceremonial harness is made from maroon goatskin and ornamented with an elaborate plume and gilt fittings.

38

39

HAWK HOODS

Various Origins

Hide with green felt sides and base bound with red leather. Crest of red wool and feathers. German, 19th century

Red leather, probably goatskin with cut out pattern and silver tassel. Indian, date unknown

Brown calf leather and red felt with wool crest. English, 18/19th century

Falconry is an ancient sport that has been practiced since prehistoric times, with references dating from cave paintings.

It involves the training of a falcon using a combination of visual and verbal signals with the main purpose of hunting small wild game.

Hoods were used during training to keep the hawk calm and prevent distraction. They also trained them to understand it was time to hunt. 1.

40

1. 2. 3.

41

2.

3.

16TH LANCERS HELMET

British, Early 20 th century

The 16th Regiment was first formed in 1759 and has always been considered one of Britain's greatest cavalry regiments.

This helmet is their classic form of headdress and was adopted by the British Army in 1816.

Decorated with a pressed brass helmet plate and chin strap.

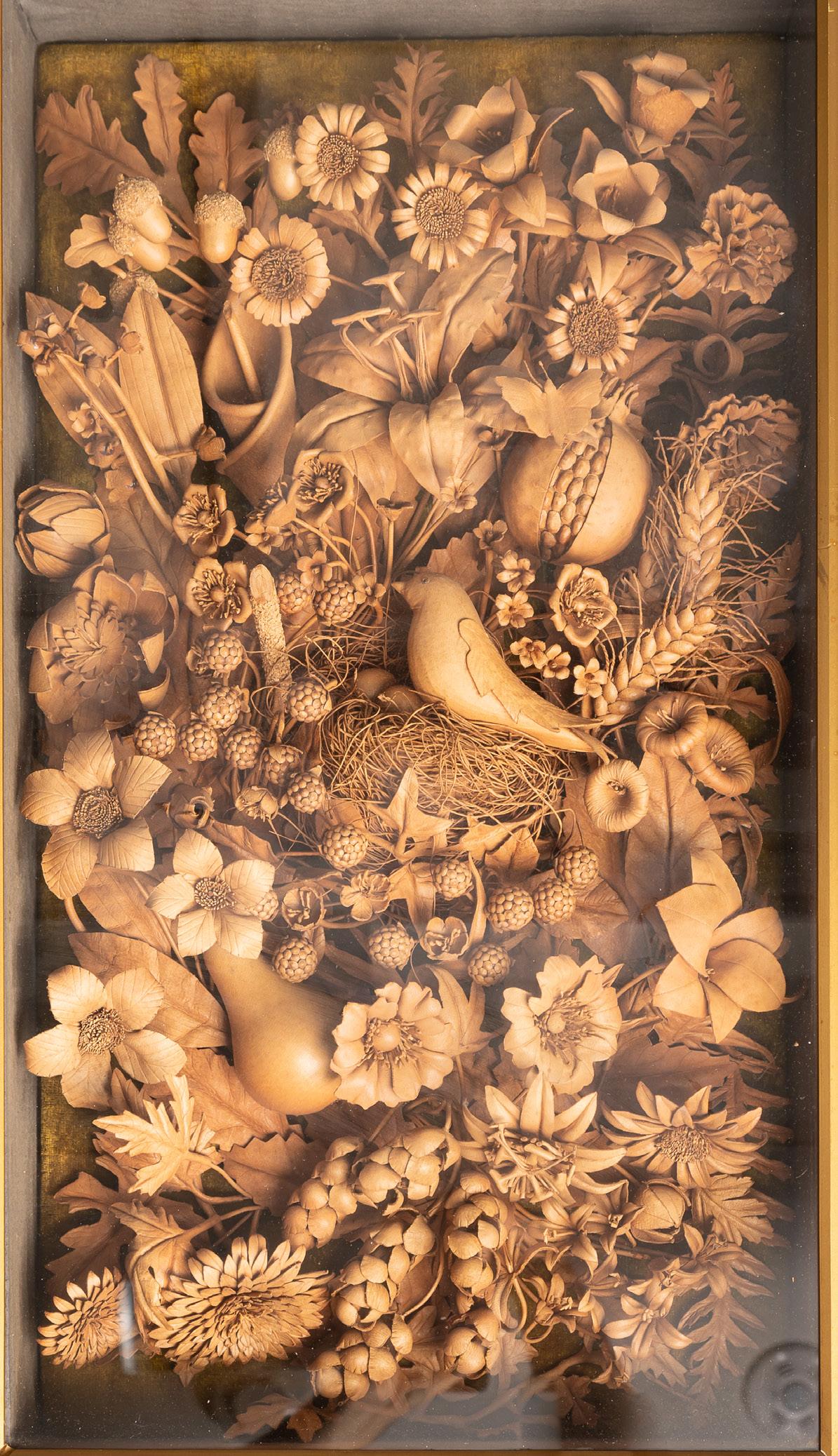

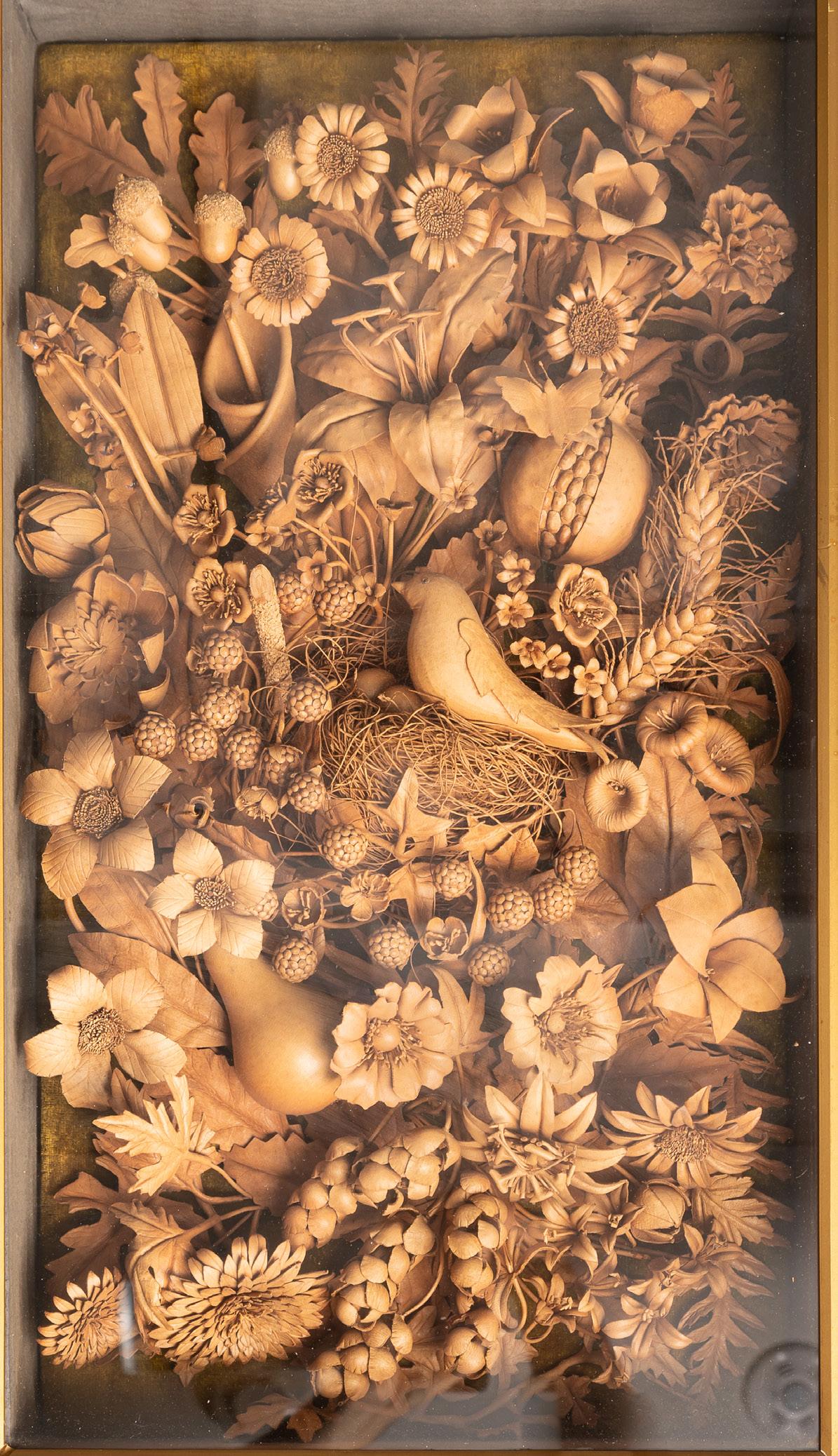

DIORAMA

English, Late 19 th century

Decorative and unique art piece expertly modelled in calf leather, featuring an intricate composition of flowers, foliage, fruit and birds.

43

DECORATIVE PANEL

Possibly French, 1850s

This decorative leather panel possibly originates from the French upholstery firm of Jean Michel Dulud, who often used historic styles which were particularly fashionable at the time.

The popular fan design with green background, polychrome flowers and gilt foliage first appeared during the 17th century and returned with the ornate trends of the Victorian period.

Although an unused sample, this embossed leather pattern would have been made for walls or for upholstery.

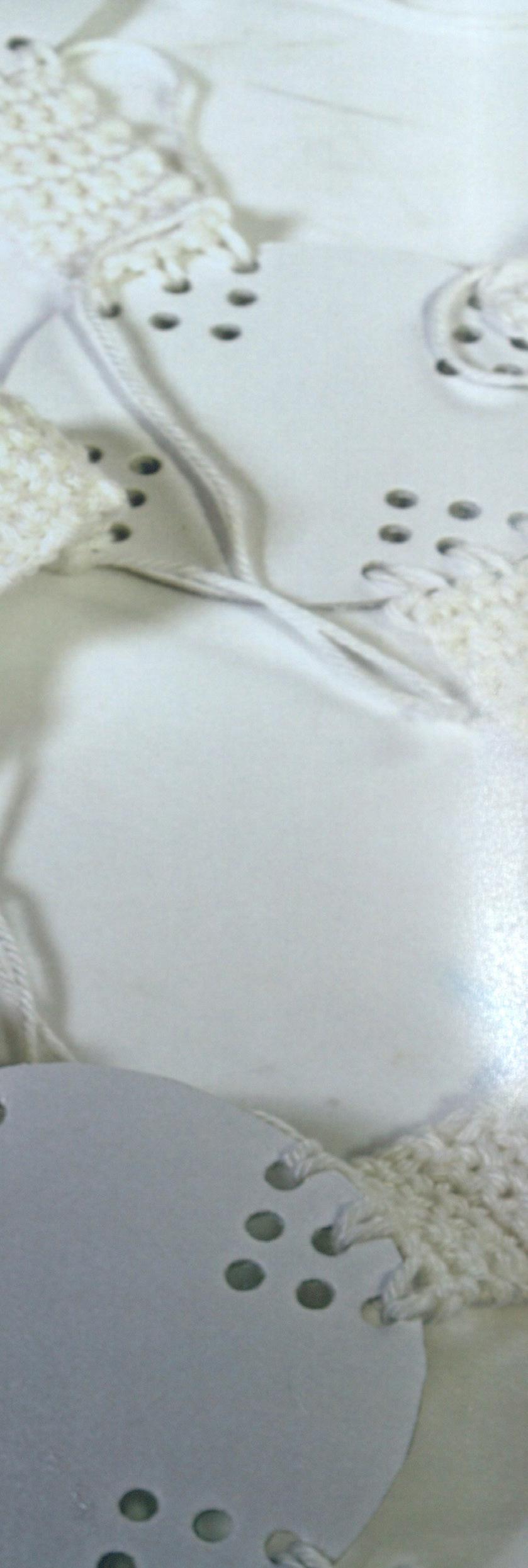

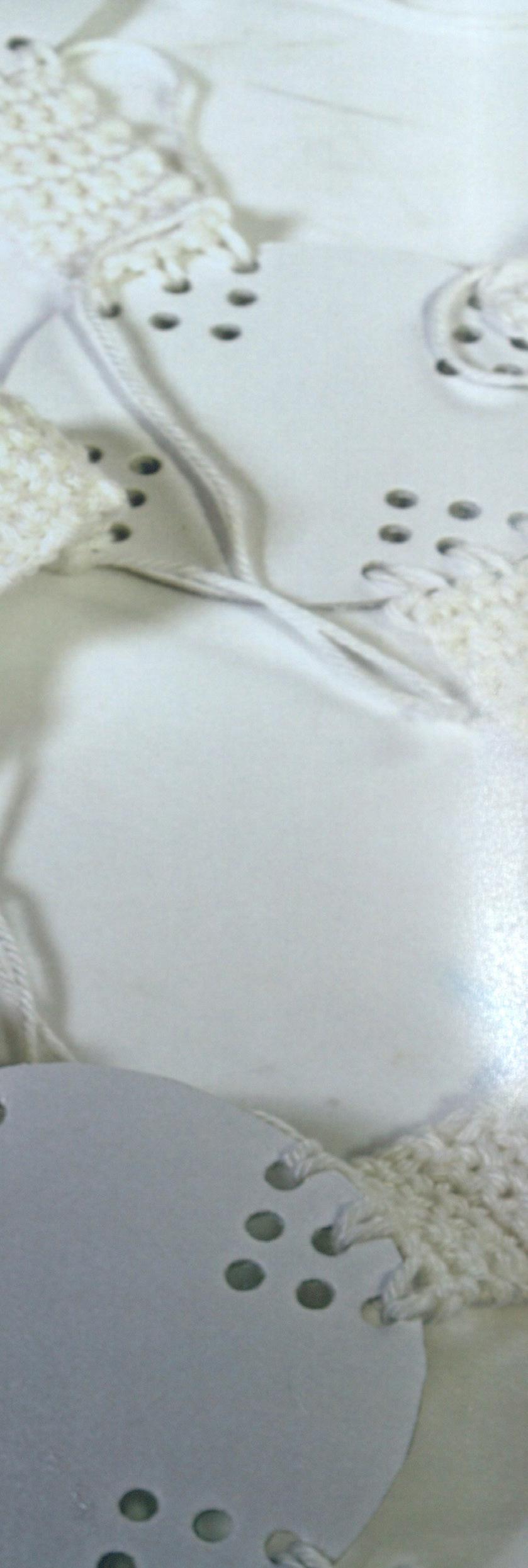

LADIES SAMPLE SHOE

Unknown, 1850

Women of the mid-19th century typically had two choices when it came to fashionable footwear, balletlike slippers or ankle boots.

Both types of shoes were made of soft, pliable textiles such as velvet or satin and had a flat, extremely thin leather sole.

As shoes were seldom seen under floor length skirts, they were usually made of a plain textile. However, evening boots were an exception and were sometimes made to match a specific gown.

This example has a cream brocade upper, trimmed with red tassel braids, blue brocade toecap and green suede heel.

45

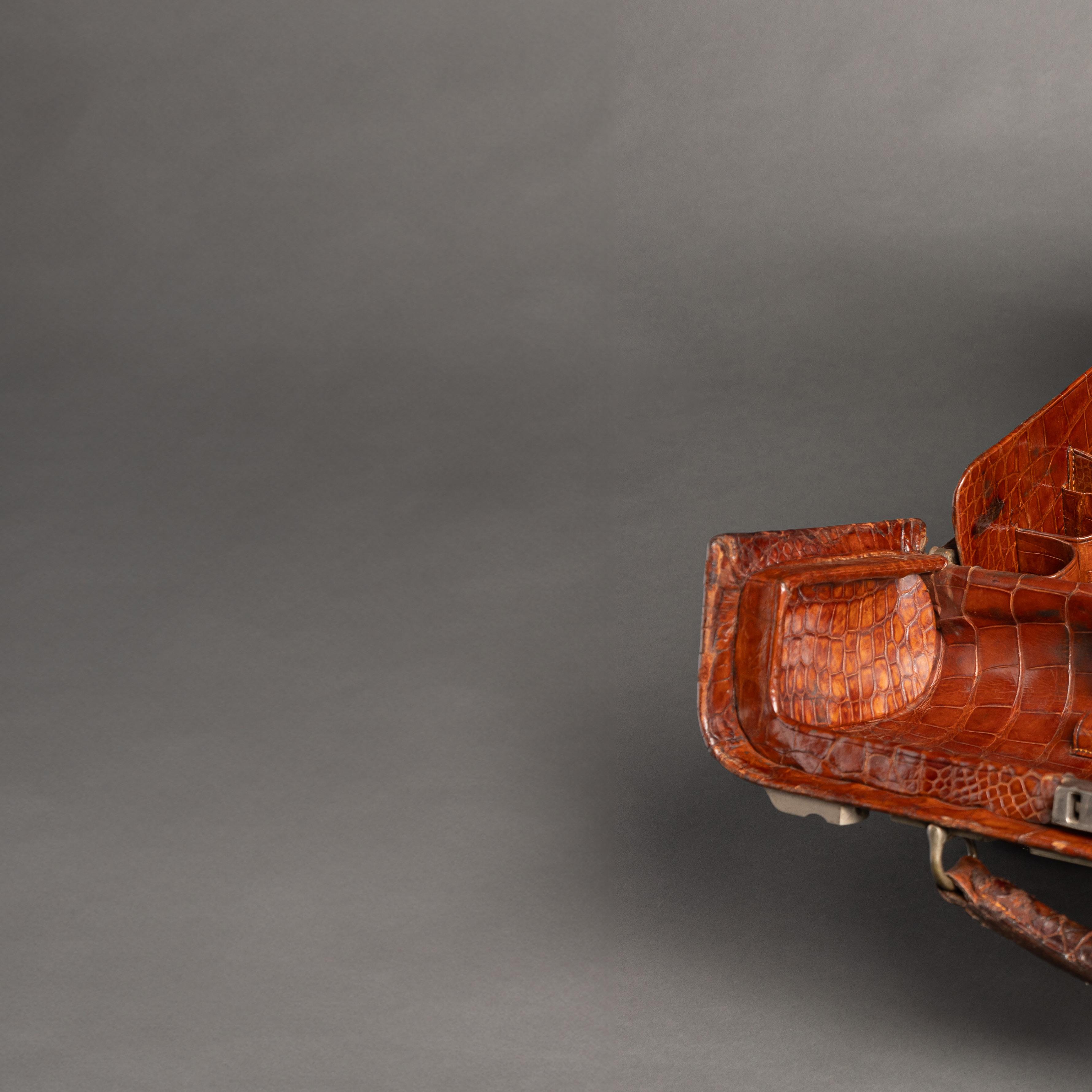

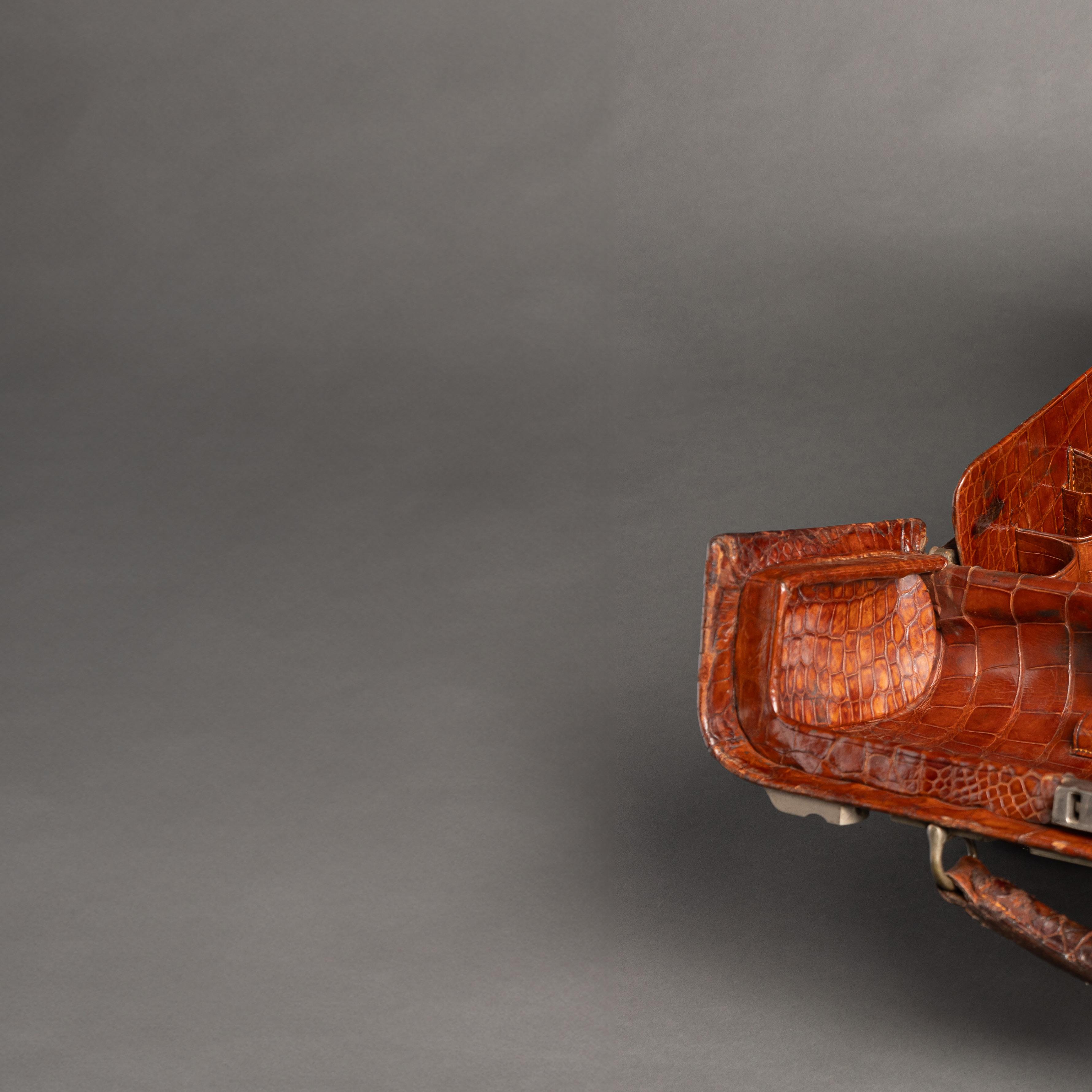

SURGEONS' MEDICAL CASE

English, 19 th century

A doctor’s kit bag was large, practical and organised to help deal with the range of conditions they would encounter daily.

In Victorian life, your local doctor would treat anything from a mild cold to an amputation.

This kit bag is made from crocodile leather and lined with pigskin.

46

47

FIRST WORLD WAR TRENCH COAT

British, 1914-1918

The term trench coat was first printed in a tailoring trade journal in 1916, referring to the outerwear garment made popular by the image of gallant military officers aiding the war effort.

The style was adapted from the revolutionary waterresistant coat created by Charles Mackintosh nearly 100 years earlier, with both Burberry and Aquascutum taking credit for inventing the new version in response to conditions faced in the trenches.

Utilitarian, functional and camouflaged, these pieces were designed to help the wearer survive the horrifying reality of life in the narrow, muddy ditches, open to the elements.

Typically made from gabardine, a worsted wool fabric waterproofed using lanolin, officers also purchased coats in other materials such as leather, like the example on display here.

Identifiable for their double-breasted and tailored style, each part of the military trench coat had a function. The belt was equipped with D-rings for hooking accessories such as binoculars, map cases, a sword, or a pistol, whilst the caped back encouraged water to drip off. The pockets were deep, the cuffs could be tightened, and the buttons at the neck helped protect from poison gas. Epaulettes on the shoulders indicated the rank of the wearer.

Civilians and foreign soldiers began wearing the coat as an act of patriotism, solidifying its popularity with the masses.

48

49

50

OPERA GLASSES

Unknown, 20th century

Also known as theatre binoculars, opera glasses are compact magnification devices usually used by audience members attending opera or theatre productions and other performance events.

Made of metal and glass with a leatherette cover for grip and concealed within a small carry case with mirror.

51

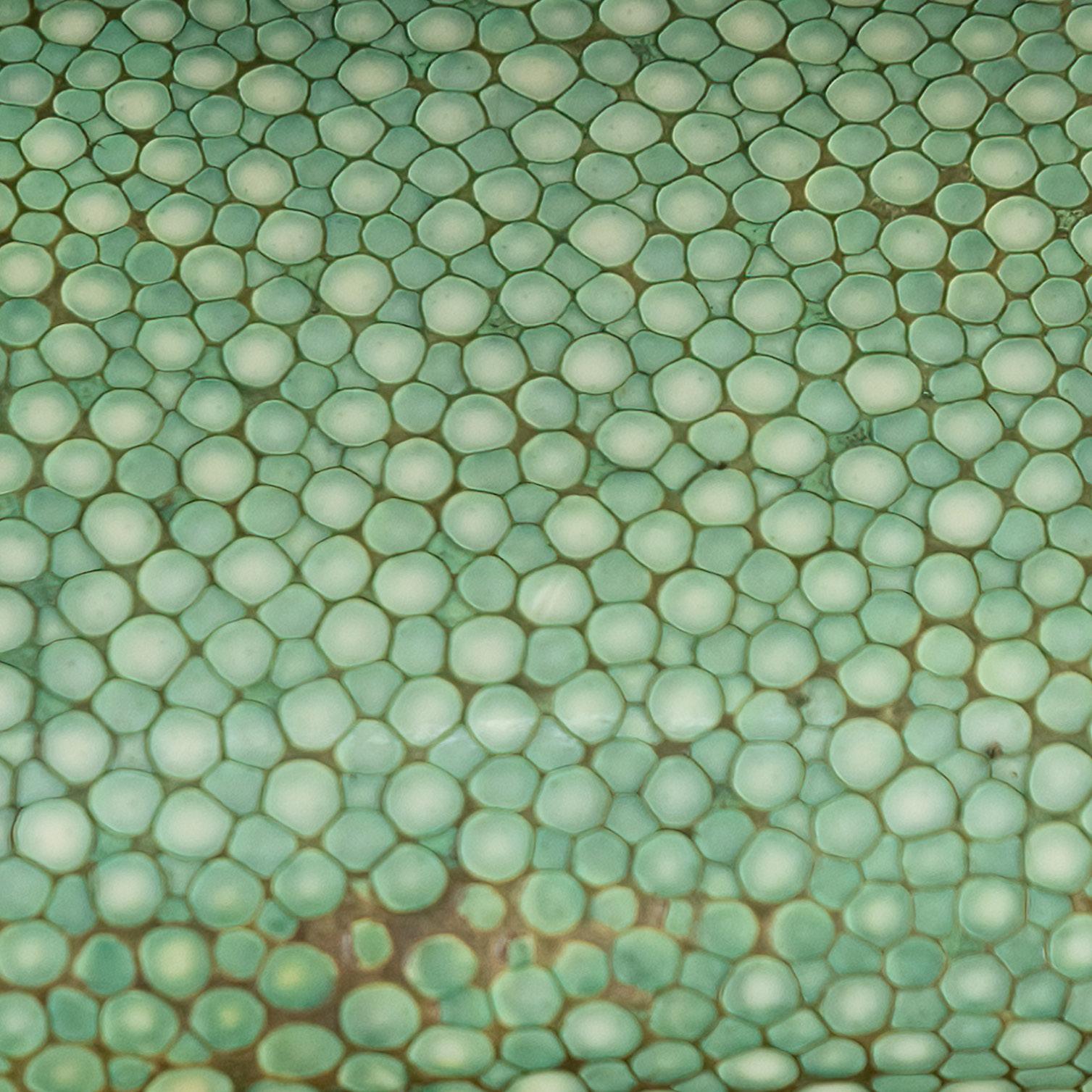

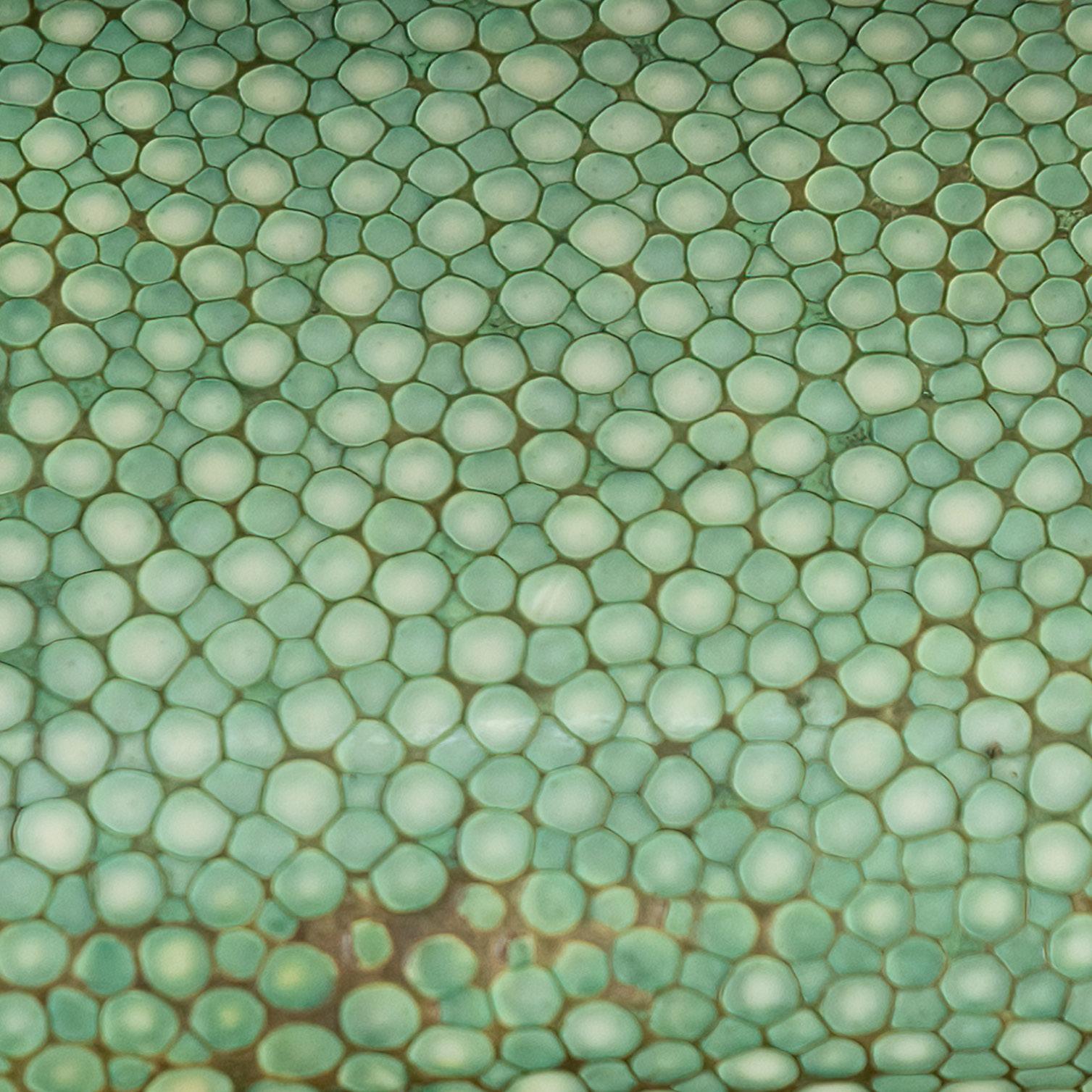

SPECTACLES CASE

French, 20th century

This spectacles case is made from shagreen, which is a natural hide typically made from shark, stingray or dogfish. Its beguiling texture is of leather-like softness punctuated by delicate dappled marks, which hints at its source.

Shagreen became popular in the Art Deco period where is was used for a variety of items from accessories to furniture.

52

53

STUDENT SHOWCASE

54

Ana Del Rio Mullarkey

Donghyeon Kim

Lucy Dollery

Mine Yeter

Martha Lavery

Olivia Bodak

‘Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather’ was developed by Gillian Proctor (Associate Professor of Enterprise) as an endeavour to preserve artisanal leathercraft for the next generation. The project celebrates the fusion of traditional craft skills with emerging technologies, encouraging future artists and designers to engage with leather.

The following work was produced by six talented students from the School of Art, Design & Architecture and Fashion & Textiles. Each individual was challenged to create innovative pieces inspired by a range of objects from the Museum of Leathercraft’s collection.

Each individual has incorporated their own unique perspective into developing creative design solutions, using both new and heritage-based skills.

Through further outreach, Artifacts Live aims to continue advocating for the importance of protecting traditional leather skills whilst supporting the evolution and sustainability of the wider industry.

55

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

ANA DEL RIO

Fashion Design BA (Hons) @anadelrio.studio

EL DOMINGO (SUNDAY)

Emanuel Ungaro, when he plunged his nose into fabrics said, “I caress it, smell it, listen to it. A piece of clothing should speak in so many ways.”

That is how I feel about leather.

As I hold it up to my face I am transported to another world; a world in which the rich tradition of leathercraft, one of mankind´s oldest traditions, is fused with innovation in contemporary pieces.

Artifacts Live helped to reinforce my desire to work with leather and the experience taught me so much.

My Spanish heritage was hugely influential in this collection as it was inspired by the quintessential Spanish Sunday traditions I enjoyed growing up in Madrid.

56

©Ana Del Rio, Feb 2023, in full or in part, all rights reserved

in full or in part, all rights reserved 57

©Ana Del Rio, Feb 2023,

However, whilst my work is personal, it is intended to evoke a collective revolutionary response for leather garments.

I want to encourage consumers to understand the value of leather and influence their choices by producing high-quality, innovative pieces, which can last and be loved for many lifetimes.

From the museum collection, I chose to work with the hand fan as I was drawn to the intricate cut-outs on the sticks. These are emulated in the cut-outs on the panels of my dress.

Fans have also been identifiable in Spanish culture since the 15th century gaining popularity in all aspects of social life and traditions.

The strong box inspired me to explore different 3D leathercraft techniques in order to recreate its raised surface aesthetic.

Conventionally, leather garments tend to have a smooth surfaces, whereas leather goods often

58

©Ana Del Rio, Feb 2023, in full or in part, all rights reserved

have surface techniques applied to them. My desire is to change this, one example being the development of a hand quilted technique applied on my jacket, thus creating a unique look.

In the future, I hope the “Ana Del Rio” brand is known for pushing the boundaries of leathercraft in fashion, creating a Leather Revolution.

Such innovation however, must be responsible. The leather used is either UK sourced deadstock to reduce its carbon footprint or waste scraps from DMU´s Footwear department. It is of the utmost importance to be sustainable in order to stem the tide of over-production and rapid consumption.

Designing and making this collection reassured me of how much I enjoy working with this natural material and how many possibilities leather offers in terms of garment and surface aesthetic.

full

in part, all rights reserved 59

©Ana Del Rio, Feb 2023,

in

or

DONGHYEON KIM

Fashion Design BA @raonbeat_liro PUPPETS IN THE CLUB

Leather has fuelled my exploration into innovative design, its allure and rebellious nature inspiring me to push creative boundaries.

Over the past year, I experimented with different types of leather and learned meticulous craftmanship, incorporating unconventional techniques, textures, and unexpected elements into my work.

Through Artifacts Live, I advanced my love of designing with leather and created garments that evoked profound emotional connections.

My work embodies LGBTQ culture and aims to challenge stereotypes, break barriers, and encourage dialogue on identity and self-expression.

Leather has been prominent and identifiable in the gay community since the 1950s, most likely emerging from the post WWII biker culture.

60

©Donghyeon Kim, 2023

61

©Donghyeon Kim, 2023

Puppets in the Club celebrates this scene and fuses leather with desire, fetishism, and the embodiment of a redefined male presence in the vibrant world of clubbing.

My collection is a personal reflection of my experience as a gay man, who found his identity in a context full of constraints. The use of the mask symbolises closeted people. It also incorporates elements that are seen as stereotypical within gay society; harnesses, for example.

Upon entering the gay club scene, I was confronted with a ubiquitous sight: men adorned in harnesses. Initially, this accessory held a symbolic meaning of freedom for me within the club's gay community. However, as time went on, the harnesses became overused and predictable, losing its original significance. It appeared as puppetry to me, manipulated and controlled by social trends, much like strings guiding a marionette's movements.

My project aims to break the notion that all gay men in a club setting conform to a singular fashion trend and targets those seeking fashionable outfits that allow them to express their individuality, personal style, and unique identities.

I was inspired by the Bavarian Horse Harness and the Japanese Saddle, as they best conveyed the message I wished to communicate. My collection explores the fusion both of these historic objects

©Donghyeon Kim, 2023

with a touch of metallic accents from the Indonesian Shadow Puppets.

Initially, I was drawn to the horse harness as it connected to the subject matter I wished to create. I gained additional inspiration from the intricate craftmanship of the saddle, focusing mostly on shape and structure. I then incorporated industrial elements like carabiners into the garment designs, which aims to introduce an edgy, unconventional aesthetic bringing my design to fruition.

By continuing to celebrate diversity and individuality within my work, I strive to contribute to a more inclusive fashion industry.

62

63

©Donghyeon Kim, 2023

LUCY DOLLERY

Fashion Textiles (Knitwear) BA

@lucydollerydesign

ARTISANAL HERITAGE

As I reflect on my involvement in the Artifacts Live project, I am filled with immense gratitude for the transformative journey it has offered. It was an extraordinary experience that left a lasting impact.

Over the past year, leathercraft evolved and flourished into a new passion of mine.

An unforgettable highlight was the enriching trip sponsored by the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers. We had the privilege of visiting esteemed locations such as Bill Amberg’s Studio in London, Pittards Tannery in Yeovil, and the Mulberry factory in Somerset. These experiences provided me with invaluable insights into the intricate processes of leather production and its versatile applications.

I was amazed by the knowledge gained, which laid a solid foundation for our upcoming endeavours.

Among the multitude of museum objects presented, I chose to explore the Samurai Saddle and Bavarian Horse Harness. Both pieces fascinated me with their structural designs and intricate decorative features, reflecting their ceremonial significance rather than purely functional purposes.

I delved into the visual aspects of these artifacts, dissecting their textures, patterns, and layers. This exploration led me to broaden my research into heritage and craft, recognising these ceremonial items as visual representations of a country’s culture and identity.

64

65

©Lucy Dollery, 2023

Having pursued a degree specialising in knit as a fashion textile designer, I sought to merge the worlds of leathercraft and knitting by experimenting with various techniques.

A meticulous handcrafted approach became integral to my creative process, as I wanted to ensure each piece showcased the beauty and skill behind the craft. This is something often overshadowed in today’s fast-paced society.

My collection focuses on preserving endangered craft techniques and aims to bridge the gap between heritage and modernity by reimagining traditional skills.

Notably, all the leather used in this project was sourced as deadstock, generously donated by industry professionals or left from previous students. This approach showcased how old materials can be transformed into new creations and contributes to a broader conversation about sustainability and conscious consumption.

Through my work, I hope to inspire people to appreciate the longevity of handmade items and preserve cultural heritage for future generations.

©Lucy Dollery, 2023

66

©Lucy Dollery, 2023

67

©Lucy Dollery, 2023

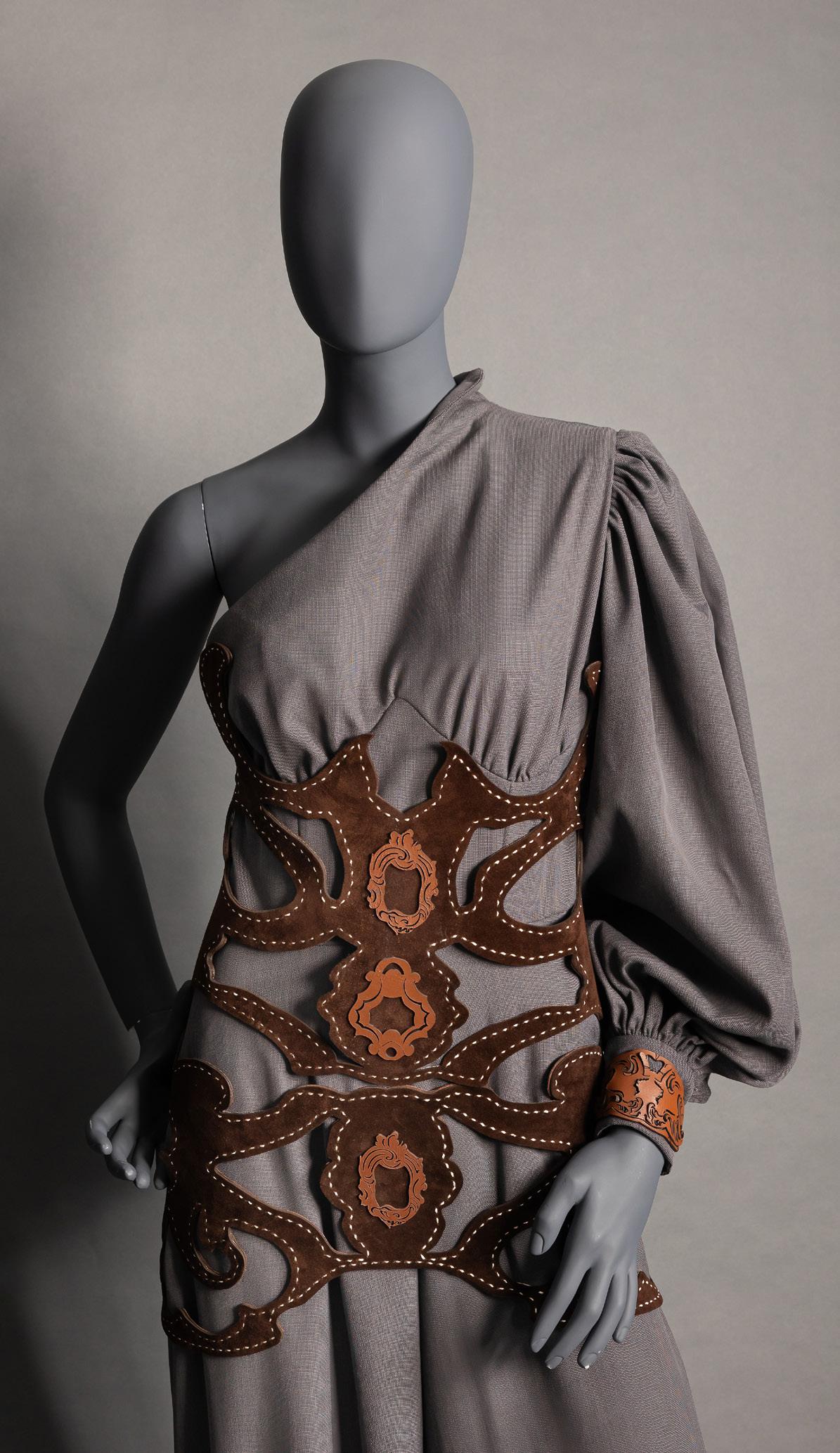

MINE YETER

Fashion Design BA

@mina_yeter EQUESTRIAN

The inspiration for my collection comes from my family, in particular my grandfather’s farm in the Besni Adiyaman province of Turkey.

This influence stemmed from the loose wool/cotton clothing worn by both men and women on the farm and I envisioned creating pieces that reflected a blend of functionality, modesty, and sophistication.

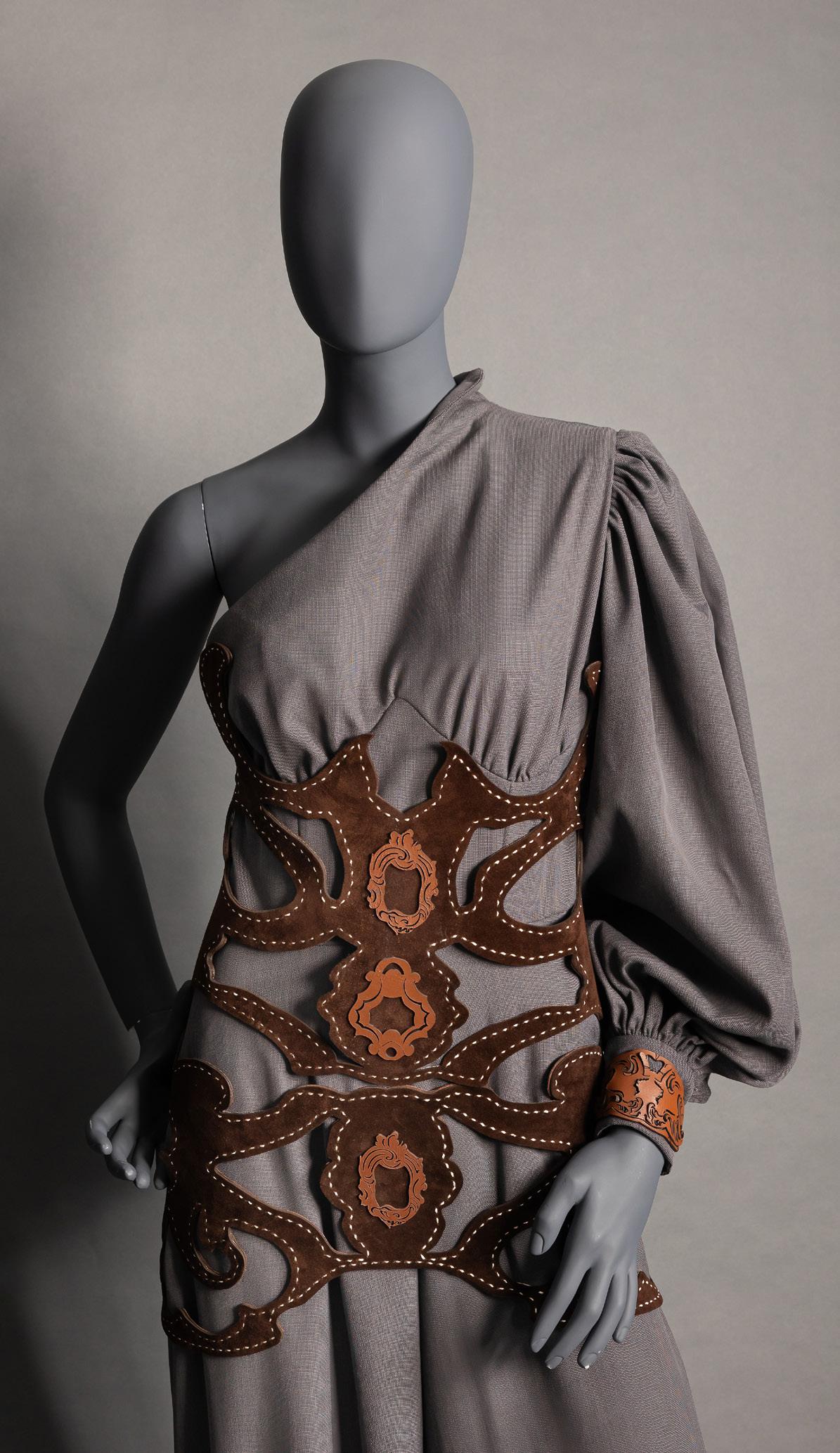

Embracing these elements, the silhouettes of my garments mirror the traditional farm styles, whilst the suede harness piece and delicate appliques add craft detailing and adorn the body as wearable art. These accessories were all stitched and polished by hand, a time consuming process that reminded me of my grandparents' patience as they wake up at 5:00am each morning to take care of their animals and maintain their saddlery.

In the eastern Turkish region, craftsmanship is revered - artistry passed down through generations. Walking through the local town and

68

©Mine Yeter, 2023

69

©Mine Yeter, 2023

watching the shop owners polish their goods ready to sell has always been a mesmerising activity of mine. This is something I wanted to incorporate into my own work.

Central to my vision was my grandad’s favourite animal on the farm, the horse.

I started researching into all things equestrian in the summer of 2022, delving into aspects like recreational horse riding, the royal ascot, military equestrian clothing and saddle making traditions.

When I entered the Artifacts Live project, I was immediately drawn to the Samurai Saddle and chose this historic piece as a source of inspiration for my project. I also noticed the incredible detailing in the Bavarian Horse Harness and wanted to explore incorporating this into women’s wear design.

The opportunity to use the historical artifacts has been a truly immersive experience as I have long valued the importance of art and craft. Having a family story that strongly relates to the artifacts pieces has brought a sense of ownership to my work.

70

©Mine Yeter, 2023

71

©Mine Yeter, 2023

MARTHA LAVERY

Fine Art BA

@marthalavery_artist

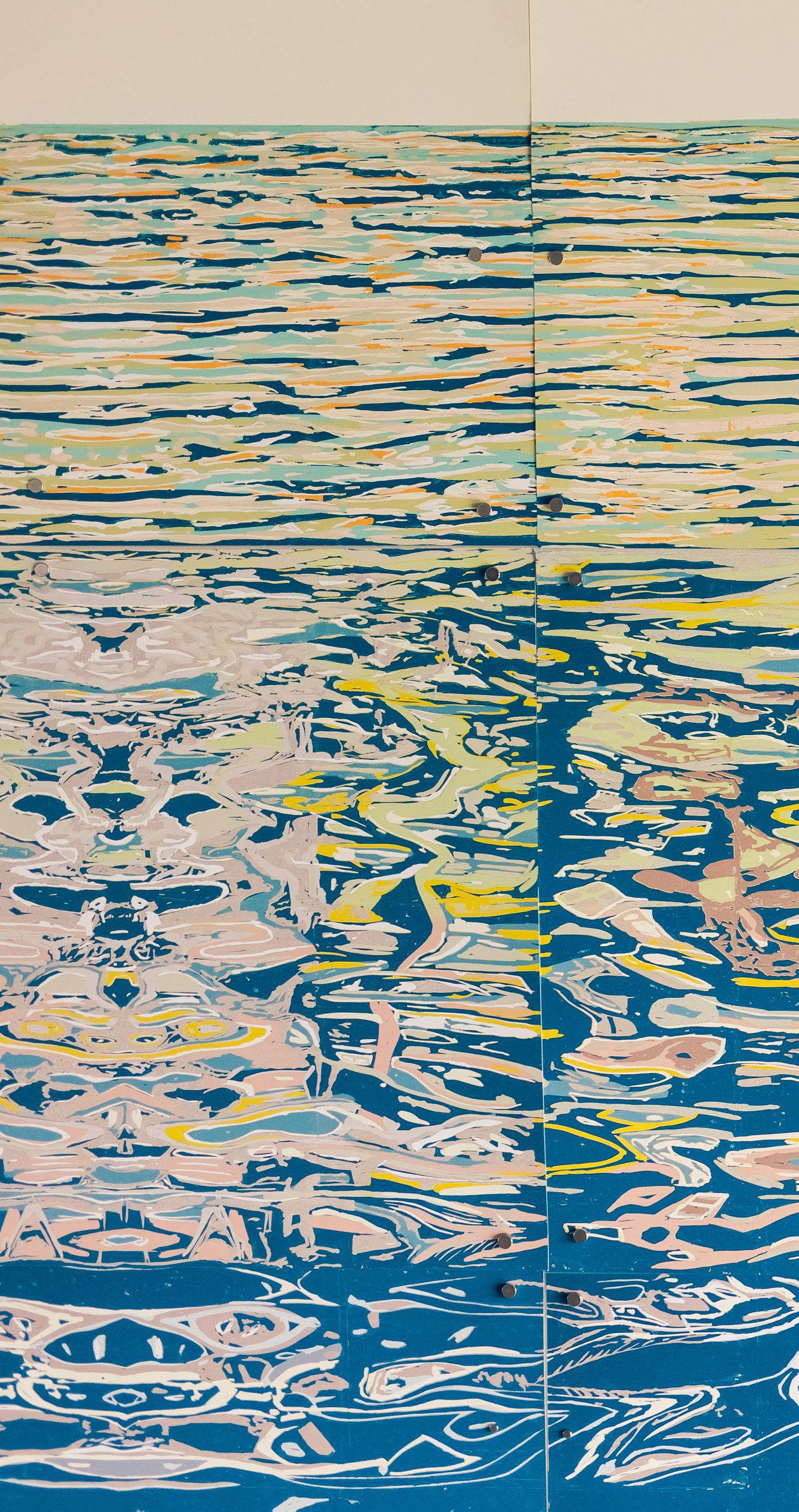

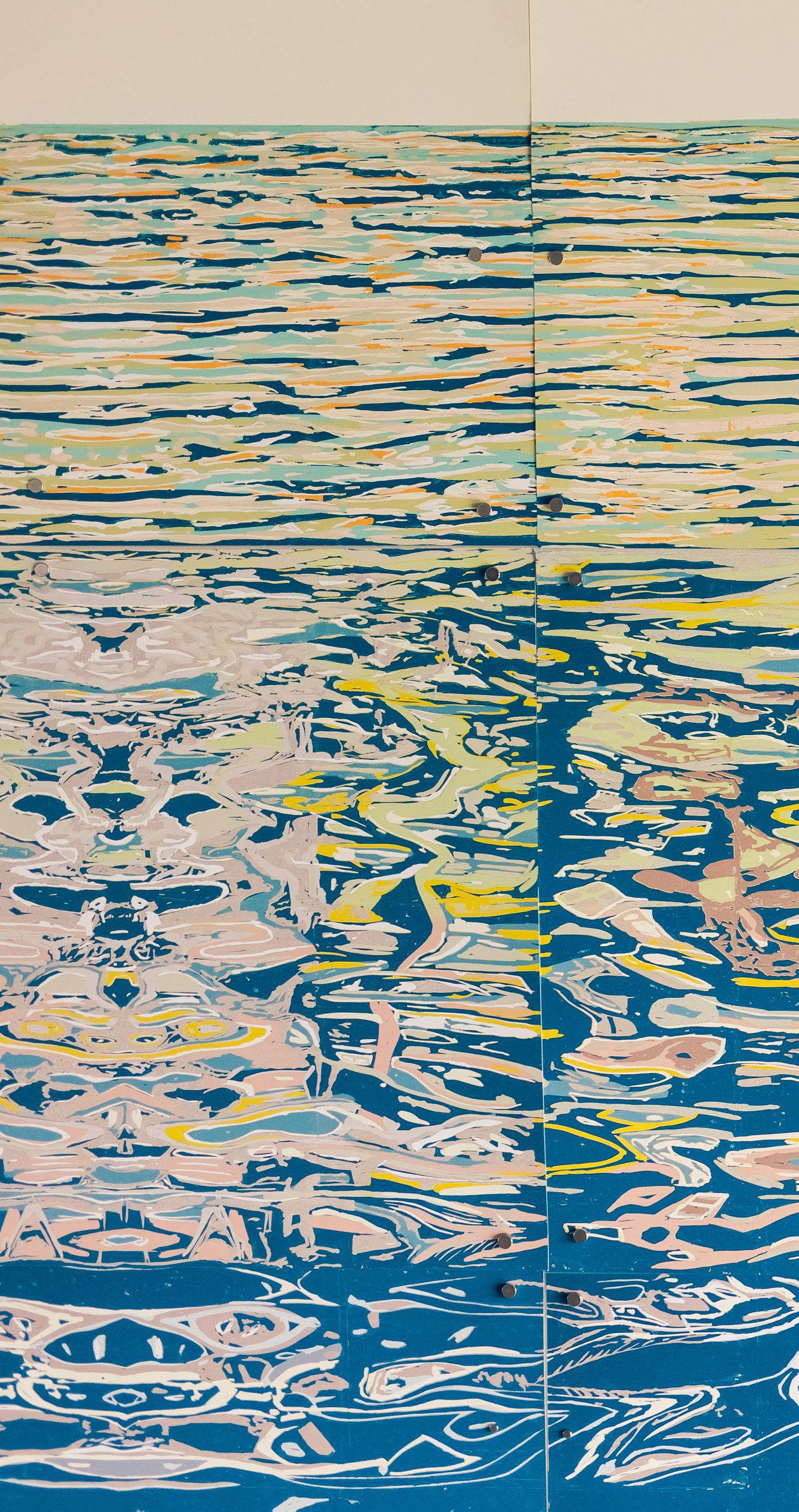

My work focuses on nature and the organic forms within it, particularly the sublimity of water and the abstract imagery created by light reflections.

This large-scale piece concentrates on the depths of water and the illusion of looking out onto the horizon, using symmetry in the style of a Kaleidoscope.

My final year project was initially inspired by my summer in the USA, a place where I was surrounded by water. I fell in love with the way the sun created different reflections on the surface at different times of the day, often creating stark contrasts.

Upon entering the Artifacts Live project, I was drawn to the gondola chair due to its connection with water, but also the beautiful curvature of the piece, which reminded me of a mythical creature emerging from the sea.

I was also intrigued by the 18th century decorative wall panel. I very much admired the symmetry of

72

©Martha Lavery, 2023

73

©Martha Lavery, 2023

the pattern, a technique I aimed to develop and incorporate into my own work.

Creating symmetry through art is challenging, however I was always encouraged to take risks throughout my degree and within Artifacts Live.

In fact, my favourite activity during the project was the 3D Flower Workshop delivered by local milliner Giulia Mio as it was an extremely detailed and delicate process, which I found inspiring and enjoyable.

As I specialise in printmaking, I wanted to incorporate this into my work and decided to create a raised relief surface onto leather.

I played with repetition by flipping images side-by-side to form a symmetrical appearance, and experimented with ways to include embossing and debossing. This technique goes back centuries and creates a sharp, crisp texture that is very appealing to the eye.

The art of embossing is producing raised patterns and shapes using a plate. For my work, I used reduction linocut to create layers of colour, tone and texture to build up the final image.

74

75

©Martha Lavery, 2023

OLIVIA BODAK

Contour Fashion Innovation MA @obodakk

Combining my specialisation of lingerie and corsetry with outerwear pieces, I chose to reimagine the timeless trench coat and set to challenge myself in terms of pattern cutting and construction. I studied the classic design and elevated my garment with a structural built-in corset at the waist.

At the start of the project, sustainability became my compass and I aligned my work with the UNSDG goal 12 of responsible consumption and production. I wanted my trench coat, crafted from durable leather and lined with pure habotai silk, to embody luxury whilst striving for zero waste.

Embellishments on my garment include 3D printed buttons made of biodegradable colour changing filament, a woven belt, boning channels and three-dimensional

76

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

77

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

cone structural sleeves; these used off-cuts of cow-hide leather, which echoed my commitment to sustainability.

From the artifacts, the Bavarian Horse Harness inspired me to incorporate multiple boning channels on the corset as well as the sleeves. The harness’ details, such as its flower-like shapes and woven texture, encouraged me to explore different techniques of weaving, pleating, and folding, which I applied on the sleeves and the belt of my trench coat.

With a passion for 3D printing, I also researched and explored different ways of combining long-lasting leather with innovative and eco-friendly additive

manufacturing. Through this, I developed a new and promising technique of 3D printing embellishments directly onto leather.

The second garment I created was corset blazer which features elements of 3D printing throughout, including the buttons, the pattern on the cuffs, and the epaulettes. The design of the embellishments is intended to mimic water movement and is inspired by the wave pattern found on the museum’s Japanese Samurai Saddle.

I discovered that the Seigaiha pattern symbolises power and resistance, and was drawn to it even more as I aim to empower women through my collections.

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

78

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

79

©Olivia Bodak, 2023

FUTURE OF THE COLLECTION

DAVID BARROW

Director of the Board of Trustees

Museum of Leathercraft

80

The Museum of Leathercraft has now closed its doors and has recently been transferred to the care of the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, which over the last few years has undergone a complete refurbishment and extension.

‘The Leathercraft Collection’, as it will now be known, will join Northampton’s world-famous Boot and Shoe Collection to create a unique shoe and leather resource centre which will become an internationally recognised collection of leather and its applications throughout the past thousands of years.

This move ensures the Leathercraft Collection a safe and secure future as part of Northampton’s Museum and art Gallery and over the next approximate 5 years will have its own gallery. In the interim, it will be available for loan, and accessible to researchers and leather lovers. This will offer a positive and directional future for all things leather and its heritage.

81

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is a pleasure to thank the following partners and individuals for their support with the development of the Artifacts Live: A Legacy in Leather exhibition.

FUNDING

The Leathersellers Company

DMU Development & Alumni Engagement

MUSEUM OF LEATHERCRAFT

David Barrow (Director of Board of Trustees)

Graham Lampard (Curator)

James Hawsksley (Curator)

MATERIAL AND VISITS

Abbey England

A Force

Bill Amberg

Billy Tannery

Dr. Martens

Giulia Mio Millinery

Mulberry

Pittards Tannery

Tusting

Walter Reginald

DMU

Gillian Proctor (Associate Professor of Enterprise)

Mary O’Neil (Associate Head and Programme Leader Fine Art)

Dr Rhianna Briars (RBI)

Christ Wright (Head of the Drawing Centre and Senior Lecturer)

Louisa Day (Deputy Director of Development & Engagement)

DMU Art and Design Technical Support Staff

Robert Harris (Graphic Interpretation)

James Birch (Museum Fit-out)

Curated by Elizabeth Wheelband (DMU Museum

Curator) and Steven Peachey (DMU Museum Assistant Curator)

Printed by the DMU Print Centre

82

83

DMU Museum

Hawthorn Building 00.34

The Newarke

Leicester LE2 7BY, UK

T: +44 (0)116 207 8729

E: museum@dmu.ac.uk

W: library.dmu.ac.uk/dmumuseum

84

DR MARY O'NEILL Associate Head of School of Art, Design and Architecture

DR MARY O'NEILL Associate Head of School of Art, Design and Architecture