156 Frank Walter To Capture a Soul

Frank Walter To Capture a Soul

Drawing Papers 15 6

Frank Walter To Capture a Soul

PL. 1

Green Sponge Flowering Trees, n.d.

PL. 1

Green Sponge Flowering Trees, n.d.

PL. 2

Untitled (View of sea through trees), n.d.

PL. 2

Untitled (View of sea through trees), n.d.

PL. 3

Untitled (Pink sky, green field), n.d.

PL. 3

Untitled (Pink sky, green field), n.d.

Director’s Foreword

When I became the Executive Director of The Drawing Center in late 2018, I came to the post with a short list of exhibitions that I hoped I could make happen here. One of my first and most pleasurable tasks was to sit down with Claire Gilman, our Chief Curator and a nine year veteran of the institution, to compare notes on our curatorial hopes and dreams. We were delighted to realize that both of us had listed the work on paper of Frank Walter (1926–2009), a lesserknown, self-taught artist from the island of Antigua, as a prime subject for an exhibition at The Drawing Center.

Six years later, Claire has achieved our shared desideratum with Frank Walter: To Capture a Soul. Working with Walter expert and fierce protector of his legacy, Barbara Paca, as well as with the Walter family and our matchless curatorial colleague, Isabella Kapur, Claire has brought together a wide array of Walter’s works on paper, ranging from drawings and gouaches to diagrams, charts, notebooks, and literary endeavors. With Barbara’s participation, she has created a wall of ephemera on the subject of Walter’s autobiography, a mixture of fact and fantasy that details the major themes in the artist’s life. This dreamscape sits at the center of an exhibition that features a dizzying array of subjects, mostly inspired by the natural world. Walter was an autodidact with deep expertise in subjects as varied as botany and genealogy; he also possessed sign-painting and carpentry skills, which he used in his artmaking. When he died in 2009, he left close to 10,000 objects and 50,000 pages of writing in his estate, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, recordings, notebooks, scripts, scores, manifestos, and even an opera. In other words, a world of which Walter was the creator and the king.

The small size of many of the objects in this exhibition belie the power that they contain, especially when seen in critical mass. Although this exhibition does not attempt to recreate the world that Walter built in several compounds on the islands of Domenica and subsequently Antigua, where he lived and worked for half a century (as did the display at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017), it offers our audience a comprehensive look at the breadth of his interests, his talent as an image maker, and his lyricism as a poet and a singer of songs.

It comes as no surprise to anyone who has experienced Walter’s visions and observations realized on paper that his work is enormously popular with fellow artists, whether they share with him a Caribbean connection, an all-encompassing world view, or a taste for waterfowl and palm trees. Josh Smith, an American painter, drawer, print and book maker, and lover of wonderful things ranging from guitars to paintings of the Florida Highwaymen, is more than a fan of Walter’s work. Smith has studied Walter’s work and visted his home and studio, but more importantly perhaps, he has been recognized by the older artist’s family as a soul in kinship with him. Asked by Claire to present a group of his own drawings in dialogue with Walter’s, Smith has provided nearly forty works on paper that sometimes share subject matter but always share a sense of wonder and fascination with nature with Walter, an artist he deeply relates to but never had the chance to meet.

On behalf of The Drawing Center, I thank everyone who has made this extraordinary double exhibition possible. Claire Gilman, our Chief Curator; Barbara Paca; the Walter family and foundation; Josh Smith and his partner Megan Lang; Marlene Zwirner and David Zwirner gallery. The Drawing Center extends its thanks as well to The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Sandra Wijnberg and Hugh Freund, Elena Bowes, Noel E.D. Kirnon, Frank Williams, and an anonymous donor for their crucial support of this project. This book, which documents and illuminates the exhibition project, was made possible by David Zwirner. We are honored and grateful for this contribution. I would like to conclude by thanking the staff and the board of The Drawing Center who so passionately and reliably create the conditions for curators to realize remarkable exhibitions like Frank Walter: To Capture a Soul.

—Laura Hoptman, Executive DirectorAcknowledgments

I would like to extend my gratitude to all the people who made the exhibition Frank Walter: To Capture a Soul possible. First and foremost, I must express my appreciation to and for Barbara Paca. Barbara is a force—of intelligence, generosity, and compassion— whose knowledge of Frank Walter’s life and work is unparalleled. Barbara was invaluable in helping me understand Walter’s complexity and genius. Sorting through Walter’s vast oeuvre would have been impossible without Barbara’s help as well as that of conservator Kenneth Milton, who took great care in ensuring each work was safe and ready to be appreciated to the best of its potential. Thomas Freund’s documentation of Walter’s environment was also essential in forming a complete picture of the artist. Thank you to the Walter family, and particularly Jule Walter, who lent from his personal collection, for allowing us the opportunity to share Walter’s artwork with our audience.

For their help in locating and bringing together the essential artworks by Walter out in the wider world my thanks go to Veronique Ansorge, James Green, and Burcu Ozler from David Zwirner; Florence Ingleby and Richard Ingleby of Ingleby Gallery; and Tom Parker from Hirschl & Adler. This exhibition would, of course, not have been realized without the contributions of our generous lenders: Elena Bowes, Alfred Giuffrida and Pamela Joyner, Brian Donnelly, Charles Struse, Jamila Willis and Courtney Willis Blair, Glenn Ligon, Glenstone, Robert Levy, M.D., James Kloppenburg, John Friedman, Joshua Rechnitz, Jule Walter, Pamela Thomas-Graham, Sarah Hogate Bacon, Suzanne McFayden, and those lenders who chose to remain anonymous. Each one of these individuals has contributed work that provides singular insight into Walter’s world.

My fellow contributors to this publication—Glenstone curator Mia Matthias, poet Vladimir Lucien, and painter and writer Lynette Yiadom-Boakye—have each crafted deeply thoughtful, illuminating entry points into Walter’s multifaceted creative universe.

Concurrently with To Capture a Soul, The Drawing Center presented the exhibition Josh Smith: Life Drawing, the artist’s homage to Frank Walter and evidence of a shared commitment to approaching subjects with curiosity and honest dedication. Life Drawing comprises nearly forty drawings (twenty are pictured in this volume) that span Smith’s career. Known for his vibrant paintings and prints ranging from abstractions to subjects such as leaves, fish, birds, grim reapers, and palm trees, Smith has also been making simple pen and pencil sketches of these subjects for more than two decades. Whereas Smith’s large-scale paintings and prints strike the viewer with their coloristic intensity and bold execution, the artist’s drawings are highly focused renderings that reflect his sensitivity to his media and his skill as a draftsman. In these modestly-scaled sketches of fish and fowl, fragments from life and evocations of death, Smith echoes Walter in creating a meditative world in which reality and the imagination are inextricably connected. It was a pleasure to work with Josh on this show and to share our mutual admiration for Walter. Thanks to Josh and to studio assistant Katie Hickman for their openness and enthusiasm in creating an exhibition that so wonderfully complements Walter’s. Josh’s drawings in this publication and in our galleries provide a vibrant contemporary counterpoint, keenly observed and made with a humble immediacy. Thanks also to Katie Priest and Marlene Zwirner at David Zwirner for their support and willingness to answer any and all questions.

Finally, I would like to thank my colleagues at The Drawing Center for approaching both exhibitions with their customary blend of professionalism, curiosity, and adaptability. Special thanks to Registrar Sarah Fogel for expertly navigating the numerous loan requests and conditions required for this show, as well as the complex installation demands. And, as always, a huge thank you to Curatorial Associate Isabella Kapur for keeping everything in order with her usual rigor, dedication, and persistence. Last but not least, I would like to thank our incredible Executive Director Laura Hoptman for her sustained support of these exhibitions, and all my curatorial endeavors, throughout our time together at The Drawing Center.

—Claire Gilman, Chief CuratorWelcome

18 If a drawing is an essay, then no one has been better suited for the task than polymath Frank Walter. And if there are curators in the contemporary art world with a gift for processing the immense breadth and intellectual impact of Walter’s achievements, few are better qualified than The Drawing Center’s Claire Gilman. It has been a pleasure collaborating with her in gaining an even deeper appreciation of Frank Walter. Following on the success of her Kahlil Gibran exhibition, Claire understands the relevance of spirituality as an artistic tool. She grasps the religious foundations of Walter’s art and how his drawings link together. Through her interpretation and dialogue with other art historians, artists, poets, and an artistic in-house conversation with Josh Smith, To Capture a Soul reveals Walter at his core—an exhibition as intentional as an altarpiece. Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye shares Walter’s gift for embracing atmosphere. In her art, arresting color combinations are simultaneously muted with somber tones in a minor key, thereby anchoring a calm acceptance of the things we cannot see. As with Walter, there is always more to her world than meets the eye. Her contribution to this volume is as insightful as her own painting. In 2022, after a long day of working on a Frank Walter exhibition at David Zwirner, Hilton Als looked up and with a long sigh stated that while Walter’s art is boundless, he is, at the end of the day, a poet. The St. Lucian poet Vladimir Lucien knows the Caribbean in this same way, and he pays homage to the miracle of Frank Walter. Glenstone’s curator and art historian Mia Matthias has been aware of Frank Walter from the beginning and adds dimension to this endeavor through her penetrating analysis of Walter’s life and work.

This exhibition and publication project allow you to travel as close to Frank Walter’s world as is achievable by creatives and scholars collaborating in an urban museum setting. In this context, one hopes that through the art, analysis, and archival materials, you will gain a unique understanding of Walter’s creative process.

—BarbaraPaca, Consulting

Curator,Frank Walter: To Capture a Soul

PL. 4

Untitled (Blue sky, blue sea), n.d.

PL. 4

Untitled (Blue sky, blue sea), n.d.

PL. 5

Untitled (Blue sea, pale blue-gray sky), n.d.

PL. 5

Untitled (Blue sea, pale blue-gray sky), n.d.

PL. 6

Untitled (Red and blue over pale blue), n.d.

PL. 6

Untitled (Red and blue over pale blue), n.d.

PL. 7

Untitled (Blue sky, gray sea, white horizon), n.d.

PL. 7

Untitled (Blue sky, gray sea, white horizon), n.d.

Creating Frank Walter

Mia MatthiasAt the end of this sentence, rain will begin.

At the rain’s edge, a sail.

Slowly the sail will lose sight of islands; into a mist will go the belief in harbours of an entire race.

—Derek Walcott1

A self-described poet, author, actor, composer, vocalist, and painter, Frank Walter worked tirelessly to perfect his crafts across mediums, proving himself to be a modern day renaissance man.2 At the time of his passing in 2009, Walter had produced over 50,000 pages of writing, 5,000 paintings, 1,000 drawings, 468 hours of recordings, and hundreds of sculptures—a testament to his unflagging dedication. The vast quantity of material is often diaristic, offering a glimpse into his shifting understanding of his environment, his sense of self, and his craft. Without ascribing meaning to the maker, it is important to consider Walter’s work within the context of the events of his life and the circumstances in which his works were created. Walter brought his own biography to the fore by dedicating a significant amount of time and effort to exploring—and in some cases, creating—his lineage and documenting the events of his life. Through his manuscripts, paintings, sculptures, and recordings, Walter wrote, drew, and painted his image of himself into existence.

1 Derek Walcott, “A Map of the World,” from Collected Poems 1948–1984 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/ poems/47662/map-of-the-new-world.

2 Francis A.W. Walter, “The Artists Exposition,” n.d., Frank Walter: A Retrospective (Frankfurt: Museum MMK für Moderne Kunst, 2020), 346.

Born in Horsford Hill, Antigua, in 1926, Walter grew up in a Caribbean society shaped by the ongoing violence of colonialism and the afterlife of slavery. In the early twentieth century, agriculture and the production of sugar made up a significant part of the island’s economy. Although slavery was abolished in 1833, the plantation system established by the British persisted. The island hierarchies echoed the colonial structures of the previous 200 years; white landowners held an unequal amount of wealth, power, and access to resources relative to the black population. In the context of this fraught history, hierarchies were established, with light complexions and proximity to Europe valued as markers of power.

It was against this backdrop that Walter came of age. Walter’s early life was marked by trials and tragedy. As a child, he lost his grandfather and his mother in quick succession. Following their deaths, his father abandoned the family, throwing them into economic turmoil. Walter and his siblings were taken in by their grandmother, Eliza Walter, and aunts, who would become important matriarchal figures in his life. Walter’s grandmother would enthrall the young artist with stories of their family lineage, including his ancestors who had traveled to Antigua from Germany and become prosperous landowners.3

Walter internalized this family history and was specifically drawn to his European ancestors, whom he saw as the landed gentry of the island. Eventually, he would disavow any African ancestry, and would invent a racial classification, Europoid, that he felt accurately described himself. Per his definition, Europoids were Europeans who had adapted to tropical environments with darker skin, though they were “sun kissed” as opposed to black. His proximity to whiteness, particularly European aristocracy, would become an ongoing focus for Walter and a recurring theme in his life and work.

Walter was assured throughout his childhood that he was different from the other Antiguan children. He was sent to Antigua Grammar School, an exclusive preparatory school where he excelled academically and was lauded for his aptitude for language, mathematics, and science. Walter’s academic and artistic abilities afforded him many opportunities to hone his craft. At twelve years

3 Barbara Paca, “The Last Universal Man,” from Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man 1926–2009 (Santa Fe: Radius Books, 2017). Paca’s biography serves as the foundation of this text, and I am grateful for her invaluable account of Walter’s life.

8

be UGLY than BAD BEAUTIFUL, n.d.

PL.old, he began apprenticing for his relatives in a woodshop where he made checkerboards, abacuses, and noisemakers, among other toys. The even grids of the painted checkerboards would eventually make their way into his paintings. Walter also learned to build furniture and coffins, working with numerous wood species, including mahogany, acacia, and lignum vitae. Later in life, Walter also created text-based drawings and paintings. His alphabet paintings were sold to tourists and offer a window into his unconventional essential references. For the letter “M,” Walter drew a lit match, depicting fire and heat through a rainbow, while for the letter “U,” Walter chose an urn, a decidedly somber reference considering the intended audience. Walter also produced signs for a variety of practical purposes, his hand-lettering ranging from careful looping scripts to blocks of geometric texts detailing business hours and job titles. On some of his signs, he took the liberty of using text to relay messages for his own purposes. One such sign reads “INTRODUCING THE NEW BREED” in stenciled black letters on a whimsical bubblegum pink background. Another features red hand-painted letters on white painted wood, declaring: “better be UGLY than BAD BEAUTIFUL” [PL. 8]. 4 Despite the direct nature of the lettering and format, Walter left room for interpretation. The signs offer a glimpse into what Walter considered important aphorisms—in both cases they allude to an awareness of how one might be perceived or understood. Through these apprenticeships and commissions, Walter learned to be methodical and systematic, carefully crafting objects and visuals that could be utilized by his community to structure and order their daily lives, from toys and furniture to the coffins in which they would be laid to rest. Walter proved himself to be a meticulous and rigorous maker, able to learn, create, and maintain structures. However, when he applied these learned logics to the world around him, he was met with skepticism and rejection.

As a child, Walter looked to the tiny island on which he and his family lived, and to the small population of Antigua, and asked his grandmother the ever-present question: “Where are the rest of us?”5 Walter turned to the past to find the answer. Walter’s ancestor, John Jacob Walter was born in 1767 in Markgroeningen, Germany. He would eventually move to Antigua where he owned several plantations. He had twelve children with Ann Bean, an Antiguan

4 Unless otherwise noted, all works are undated.

5 Frank Walter, autobiographical transcript (p. 29), quoted in Paca, The Last Universal Man, 247.

woman born to John Daniel Bean, a white man from Scotland, and Barbara, an enslaved black woman. John Jacob Walter and Ann Bean had twelve children. Two of their sons, Jacob Daniel Walter and Peter Philip Walter, would eventually assume positions as plantation owners, amassing wealth and power through the money and connections afforded to them by their father. Another son, George Christian Walter, had a son with Sarah Joseph, an enslaved woman. He raised the child, George, with his white wife. George would become Frank Walter’s great-grandfather. Between the lines of these bonds and histories passed down to Walter by his matriarchs are the brutal realities of slavery, sexual violence, and the implicit understanding that Barbara, Ann, and Sarah Joseph were constrained by captivity, and were not afforded choice or agency in the roles they played in this family history.6 In an ivory miniature made circa 1796, Ann Bean is depicted as a white woman. In portraits painted circa 1825, Jacob Daniel Walter and Peter Philip Walter are depicted as white men [FIGS. 1, 2]. These depictions not only allow the Walter family to become white with the passage of time, but it’s possible they also reflect the self-identification of the white-passing family that had to hold the contradiction of being both slave owners and the immediate descendants of the enslaved. Walter internalized these histories and understood himself to be European, particularly identifying with the German origins of his

6 See Joy James, “The Captive Maternal Is a Function, Not an Identity Marker,” Scalawag, April 28, 2023, https://scalawagmagazine.org/2023/04/captivematernal-joy-james/.

forefathers. At only twenty-two, Walter became the first non-white manager of a sugar plantation. Walter had an affinity for agriculture and demonstrated a deep and wide-ranging knowledge of flora, fauna, and plant systems. Though the plantation yielded its highest results in the five years after Walter joined, the position of overseer isolated the young artist. Walter endured virulent racism from the white plantation workers and understandable distrust from the black population. When offered a promotion, Walter rejected the opportunity, instead choosing to embark on a European Grand Tour in the tradition of his ancestors. In 1953, Walter traveled to England with his cousin, Eileen Gallwey. Upon their arrival in London, Walter and Gallwey were met by their cosmopolitan uncle, Carl Walter, who assessed the two before taking the light-complexioned Gallwey away to meet their family and leaving dark-skinned Walter alone in the middle of central London’s Tottenham Court Road. Walter proceeded to face extreme racism and poverty for almost eight years in Europe. He traveled England, Scotland, and Germany, cycling through menial jobs while also taking evening classes on chemistry, metallurgy, and physics. Walter dealt with a devastating loss when another cousin was murdered for dating a white woman in London. His mental health deteriorated as he grappled with the brutal reality of racism, and following bouts of delusions, paranoia, and hallucinations, Walter was briefly committed to a mental asylum. Walter’s self-portraits are an attempt to depict himself as he saw himself and reconcile the discrepancy between his expectations and experience. In a somber black-and-white self-portrait he paints himself in profile with a downcast gaze [FIG. 3]. He depicts his skin in a stark white, forgoing the subtleties of flesh tones in favor of a monochromatic portrait. Only in the outline of his eyes does he allow for a glimpse of black skin, suggesting a mask. Walter follows the logic established by his forefathers by painting himself as white, perhaps in the hopes that history would eventually acquiesce to his chosen vision of himself even if the present refused. Walter also established his place in the world through careful and meticulous genealogical charts in which he traced his ancestors back several centuries [PLS. 109–111]. These family trees feature an incredible amount of detail and care. Working in a fine script, Walter crosses time and continents as he creates the case for his existence. The overlap between enslavers and the enslaved often resulted in entire generations shrouded in secrecy. Following the deaths of the matriarchs who taught him these precarious histories, it is possible Walter felt obligated to preserve this knowledge, which

may have been considered illicit and therefore unspoken for the prior generations. Walter applied his exhaustive knowledge of classification systems and his methodical nature to documenting his family. Where he found gaps, he extrapolated, making leaps from his known family connections to European aristocracy ranging from King Charles II to Diana, Princess of Wales. The charts are Walter’s attempt to account for the silences and omissions in how he came to be, and to establish the inheritance of stature, titles, and power that he and his family were entitled to. Upon learning of young Walter’s prestigious position at the plantation, Walter’s grandmother told him: “Your great grandfather practically owned those estates…You are now only going to be a hired servant on what is really your own estate.”7 To account for his place in the world as he understood it, Walter used elaborate family trees, intricate drawings of crests, and portraits. Walter tirelessly applied the systems and logics that had been proven to work for those before him, but he was unprepared for the world’s contradictions.

Over the course of his life, Walter became well acquainted with isolation and solitude. In 1961, Walter was sent to live on the island of Dominica. His eccentricities were deemed a potential threat to the political aspirations of his cousin, George Walter. In Dominica, Walter named his mountaintop estate the Mount Olympus Industrial and Agricultural Estate. Walter described himself as having an almost prophetic connection to nature. In the thick, uncultivated

7 Frank Walter, autobiographical transcript (p. 430–431), quoted in Paca, 261.

PL. 9

Untitled (Whale with round eyes), n.d.

PL. 9

Untitled (Whale with round eyes), n.d.

PL. 10

Untitled (Woman in dress with big shoes), n.d.

PL. 10

Untitled (Woman in dress with big shoes), n.d.

PL. 11

Untitled (Woman in a short dress), n.d.

PL. 11

Untitled (Woman in a short dress), n.d.

PL. 12

Untitled (Two men boxing), n.d.

PL. 12

Untitled (Two men boxing), n.d.

rain forest of Mount Olympus, Walter would read the sounds of leaves to predict the approach of storms. To the artist, each species of tree, with their varying densities of wood and canopies, communicated in a different way. He not only survived but thrived in this untamed landscape, clearing much of the dense terrain by hand in a nearly impossible feat. Walter built a miniature train system that connected his remote mountaintop home to the nearest town, allowing for resources and supplies to be sent to him and his few neighbors. With significant time and effort, Walter transformed the estate into a desirable plot of land. He then began having repeated visions of people and snakes confiscating his oasis. Upon completing the clearing of the land, Walter was informed that the title to his estate had been transferred to a nearby plantation; his oasis had been lost.

The sculptures that Walter created in this period hearken back to his early days of woodworking. Unlike the thousands of paintings, writings, and materials Walter produced for public display and sale, he created his sculptures entirely for himself and never sold a sculpture. He considered them powerful spiritual talismans that accompanied him in his isolation. Untitled (Whale with round eyes) speaks to one of the few constants in his life: the ocean that surrounded him, threw storms at him, and brought him to new lands before bringing him home again [PL. 9]. In Untitled (Two men boxing) Walter used cutouts to articulate a looping mass of limbs and fists, demonstrating his ability to capture movement and dynamism in dense materials [PL. 12]. The sculptures are made of acacia and mahogany, hardy tropical species that Walter likely knew would outlast his own life.

In 1992, Walter moved to a rural area on Bailey’s Hill in Antigua, once again becoming his own primary companion in what would be his final home. In his autobiography, he wrote: “I had begun to lay tremendous stress on my reclusion. I wanted to be by myself for a while. I wanted a place far away from people.”8 Surrounded by thick brush, animals, and expansive views of the ocean and sky, Walter turned to his surroundings for inspiration, as he had done throughout his life. Walter’s landscape paintings depict the shifting modes of the craggy coast, the various phases of the sun, and the impenetrable horizon. These paintings vary in style; at times, Walter inserts himself staring out into the horizon, calling on the combination of melancholy and optimism characteristic of German

8 Frank Walter, autobiographical transcript (p. 3029), quoted in Paca.

PL. 13

Untitled (Yellow land, hot orange pink sky), n.d.

PL. 13

Untitled (Yellow land, hot orange pink sky), n.d.

PL. 14

Starfish on Beach, n.d.

PL. 14

Starfish on Beach, n.d.

Romanticism. In others, Walter employs the practical simplicity of his early sign works, flattening the landscape into geometric forms, as in the vivid bands of color in Untitled (Yellow land, hot orange pink sky) [PL. 13] and the soft, layered washes of color in Starfish on Beach [PL. 14].

In addition to landscape paintings depicting the natural environment, Walter turned to the cosmos and his ongoing love of science to produce abstractions. In Untitled (Heraldic dots), evenly measured circles climb the canvas creating a visual exploration of form and color [PL. 15]. MWG Milky Way Galaxy [PL. 16] is one in a series of six paintings that are “the only known paintings to survive from Walter’s Galactic category [of works], which is inspired by astrophysical mathematical concepts.”9 Walter depicted the galaxy and planetary systems using bands of color, letters, and radiating circles. These exemplary late abstractions are his least self-conscious works. The cosmological meditations are reminiscent of the work of the Swedish abstractionist Hilma af Klint. Like Walter, Klint used a scientific background—hers in cartography and anatomical drawings—and a deep reverence for the natural and spiritual world to produce drawings, paintings, and copious journals and texts. Both artists translated their visions and the unseen world into abstract artworks, sure of a future audience that would one day appreciate their work after lifetimes of rejection.

In his later years, Walter built on the knowledge amassed throughout his lifetime. He incorporated scientific concepts reminiscent of the diagrams he would have encountered in his studies and agricultural work. He returned to the skills learned in apprenticeships as a toymaker and sign maker. His paintings of the cosmos and scientific abstractions are unfettered; his focus is on his vision and his rich interior dialogue. His works made in isolation are less concerned with perception or translating his ideas for an unwilling audience. Through applying his learned logics and systems to the world, Walter had encountered compounded rejections. He learned that the world is full of contradictions, that race and power are neither logical nor scientific, and that the tools given to him were never intended to free or empower him. Eventually, Walter found relief from these contradictions in that which can never be fully known or harnessed: the cosmos, the natural world, the passage of time, and his own mind.

9 Paca, “The Last Universal Man,” 311.

PL. 15

Untitled (Heraldic dots), n.d.

PL. 15

Untitled (Heraldic dots), n.d.

PL. 16

MWG Milky Way Galaxy, n.d.

PL. 16

MWG Milky Way Galaxy, n.d.

Death and the Universe

Francis A.W. Walter ANTIGUA. w I. 23:3:1994

I should like to know

What our universe would be like

When one shall die the inevitable death. Should death be the eternal oblivion. Yet, what relieving sleep doth show, Is somewhat like a lowland dike, That keeps away the consciousness of faith: There we care not whether battles are lost or won!

Now I am awake and conscious, And my inner eyes are fully tuned to optics, I am moved to awesome wander, Whether in dreaming, life being there remote, That life, which doth continue, is more efficacious, Producing finer images pleasant, or for ghoulish tricks: Yet in the ether, capable of comedy, or life’s tragic plunder. As in temporal sleep, within there life does float.

War and peace, comedy and tragedy, Following the living human soul, Whether in the sleep of death, or temporal sleep: We are too, inescapable from life, and sleep and death, from universe. Whether the soul is bodily bound or free, Like our planet’s polarise from pole to pole, Yet still a binding force our lives, does keep, Whether like hurricanes, we strike, or do disperse

A storm we think is dead, Oftener does rest in a pacific mood, Still bounded, yet by a greater volume

So are we bounded by our body, or dispersed, Compressed in body, the tangent makes us hear, And to realize so many another sentiment of evil or of good, Yet in life’s temporal sleep we bloom, Whether by images, life we enjoy, or are coerced.

By dream or meditation, Both of a body’s temporal moments, I am obliged by what I may perceive, That life is so continuous, That is somehow sees by body, or by spirit done, The single life in body or spirit gives consents, The body giving consent to spirit to be free, to enjoy or grieve, Even as the bodied spirit magnifies its seeing such to discuss.

The dead knows not that it is dead. For still the spirit live in meditation or in dreaming Else lives the spirit in temporal oblivion, Only to resort alternatively, to temporal awares, We know from surgery, practised or well read, What the human bodied spirit, the soul doth bring Taking itself from the unconscious to the conscious station. So from the subconscious to its blatant consciousness, a mortal cares. [P.1]

Often a patient may observe a surgeon, Extracting organs from one’s self, Fully conscious of what could be a painful act, Except that the organ’s tissues are put to sleep, or death Yet lives that organ and the rest of organs, the act being done While the extraction of the damaged organ makes another shelf As the conscious section of the body knows the fact. The entire body with life and spirit had not lost faith.

Should a surgered organ be not extracted, But sleeps unconsciously to be repaired, There it is temporal death oblivious, While still the conscious members could have narrated, All that were seen and felt and yet not feared. Yet could in horror or relief the surgery discuss Whether the feeling was relief’s delight or by the operation aggravated.

Who knows what arguments

A life could raise,

After a surgeon doth clinically state, The possibility of rigor mortis, so issued a certificate of death? With all the sciences on life, giving such consents? So epitaphs are written upon which posterity may gaze, There a spirit for its body makes there no claim, however great, Yet the world still mourns the greats whose spirits with body had lost faith.

So often in dreams and meditation, I myself, have seen astounding beauty, That to record by art, such aesthetic seeings, Impertinence should soon die, Leaving me clear channel, to have done.

To perform my artistry, trying to capture such infinity. Yet I return to fully conscious life a bodied human being. Realising the uncapturable however hard I bodily could try.

A window into everlasting life, May be quite carefully cut, So peeping through with clean spiritual eyes

The heart is told the more said overture, That the bodied spirit hears of in banal strife, The errors we bodily are conscious of are blinders of our free spirits immortal because of mortal’s rut.

Dream on and meditate, and when achieving life’s perfection, Pray that we do not reciprocate humanity: life’s everlasting joys in spirits we could assure.

PL. 18

Istiophorus platypterus, Indian Swordfish, n.d.

PL. 18

Istiophorus platypterus, Indian Swordfish, n.d.

PL. 19

Untitled (Bird standing on one leg), n.d.

PL. 19

Untitled (Bird standing on one leg), n.d.

PL. 20 White Bird, c. 1975

PL. 20 White Bird, c. 1975

PL. 21

Untitled (Sea bird catching fish), n.d.

PL. 21

Untitled (Sea bird catching fish), n.d.

PL. 22

Untitled (Birds in flight), n.d.

PL. 22

Untitled (Birds in flight), n.d.

PL. 23

Untitled (Bird in profile), n.d.

PL. 23

Untitled (Bird in profile), n.d.

PL. 24

Untitled (Striped fish), n.d.

PL. 24

Untitled (Striped fish), n.d.

PL. 25

Untitled (Flying fish), n.d.

PL. 25

Untitled (Flying fish), n.d.

PL. 26

Untitled (Bird in flight), n.d.

PL. 26

Untitled (Bird in flight), n.d.

PL. 27

Caranx stellatus, Blue Corevalley, n.d.

PL. 27

Caranx stellatus, Blue Corevalley, n.d.

PL. 28 Fish, n.d.

PL. 28 Fish, n.d.

29

Untitled (Grid of eighteen goats, dogs, and cats), n.d.

PL. PL. 30 Nag, n.d.

PL. 30 Nag, n.d.

PL. 31 Match, n.d.

PL. 31 Match, n.d.

PL. 32 Fish, n.d.

PL. 32 Fish, n.d.

PL. 33 Vat, n.d.

PL. 33 Vat, n.d.

PL. 34

Untitled (Bird in flight), n.d.

PL. 34

Untitled (Bird in flight), n.d.

To Capture a Soul

Claire GilmanUpon his death, Frank Walter (1926–2009) left behind an enormous body of work including 5,000 paintings, 1,000 drawings, 600 sculptures, 2,000 photographs, 468 hours of recordings, and a 50,000-page archive. The exhibition that is documented in this volume, Frank Walter: To Capture a Soul, includes examples of all these media, the sheer diversity testament to Walter’s relentless urge to discover, record, and recreate the world around him. In this sense, Walter was shaped by a drawing impulse—what scholar David Rosand describes as an open-ended, exploratory drive rooted in “ambivalence,” “a tentative probing,” and “a skepticism in search of assurance.”1 If, simply put, painting aims to establish an allover, holistic compositional space, drawing is always incomplete; it looks outwards, gesturing away from and beyond itself. Quoting Michelangelo scholar Charles de Tolnay, Rosand observes: “Not yet completely liberated from its creator, nor from matter…[drawing] reveals an embryonic world…Half matter, half spirit, the drawing is for us a symbol of the world in formation.”2

This need to articulate the world and his place in it motivated Walter throughout his life, as Mia Matthias outlines so cogently in the preceding essay. A child of the colonial system descended from both white plantation owners of Germanic ancestry and enslaved individuals of African descent, Walter went to Europe in search of his origins in the late 1950s and returned newly cognizant of racial prejudice and economic injustice. Although Walter had always been artistically inclined, having taken drawing classes in Antigua

1 David Rosand, Drawing Acts: Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2002), 1–2.

2 Rosand, 20.

as a child and having apprenticed in his relatives’ woodshop as a teenager, it was after returning from his European tour in the early ’60s and setting up a home first in Dominica and later in Antigua that he began to draw and paint in earnest. He found solace by exercising his imagination through creating elaborate genealogical charts tracing credible and fictitious ancestors over centuries and by studying his environment.

In the latter pursuit, it is instructive to consider the words of fellow Caribbean poet Derek Walcott who has described his generation’s task after “the withdrawal of empire” as the founding of their identity from ground zero: “For imagination and body to move with original instinct, we must begin again from the bush,” he observed in his 1970 essay “What the Twilight Says.” The excolonized had been deprived of any history to call their own and were thus in the paradoxically advantageous position of being “reduced once more to learning, to a rendering of things through groping mnemonic fingers.” In this way, Walcott explains, “a new theatre could be made, with a delight that comes in roundly naming its object.”3 This is the reward that comes from “our own painful, strenuous looking.” Only “the learning of looking, could find meaning in the life around us, only our own strenuous hearing, the hearing of our hearing, could make sense of the sounds we made.”4 The goal according to Walcott was to create a new world out of the natural canvas before them. “There is a force of exultation, a celebration of luck, when a writer finds himself a witness to the early morning of a culture that is defining itself, branch by branch, leaf by leaf, in that self-defining dawn.”5

Walter’s work is also about looking: looking as a way of understanding and looking as a way of founding, with observation and imagination inextricably linked. Walter’s compositions echo Walcott’s as, leaf by leaf and branch by branch, he explores the downy softness of the cottonwood tree [PL. 119] and the pink-andgreen clusters of the Dombeya [PL. 120]; or, among his many views of birds, the elegant bearing of the white egret [PL. 35] and the proud, open stance of the Antiguan cormorant [PL. 36]. With Walter, we

3 Derek Walcott, “What the Twilight Says” (1970), in What the Twilight Says: Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 23.

4 Walcott, “What the Twilight Says,” 9.

5 Derek Walcott, “The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory” (Nobel lecture, 1992), in What the Twilight Says: Essays, 79.

PL. 35

Untitled (White bird on top of building), n.d.

PL. 35

Untitled (White bird on top of building), n.d.

PL. 36

Coastal Scene with Boat, Cliffs, and Shorebird, n.d.

PL. 36

Coastal Scene with Boat, Cliffs, and Shorebird, n.d.

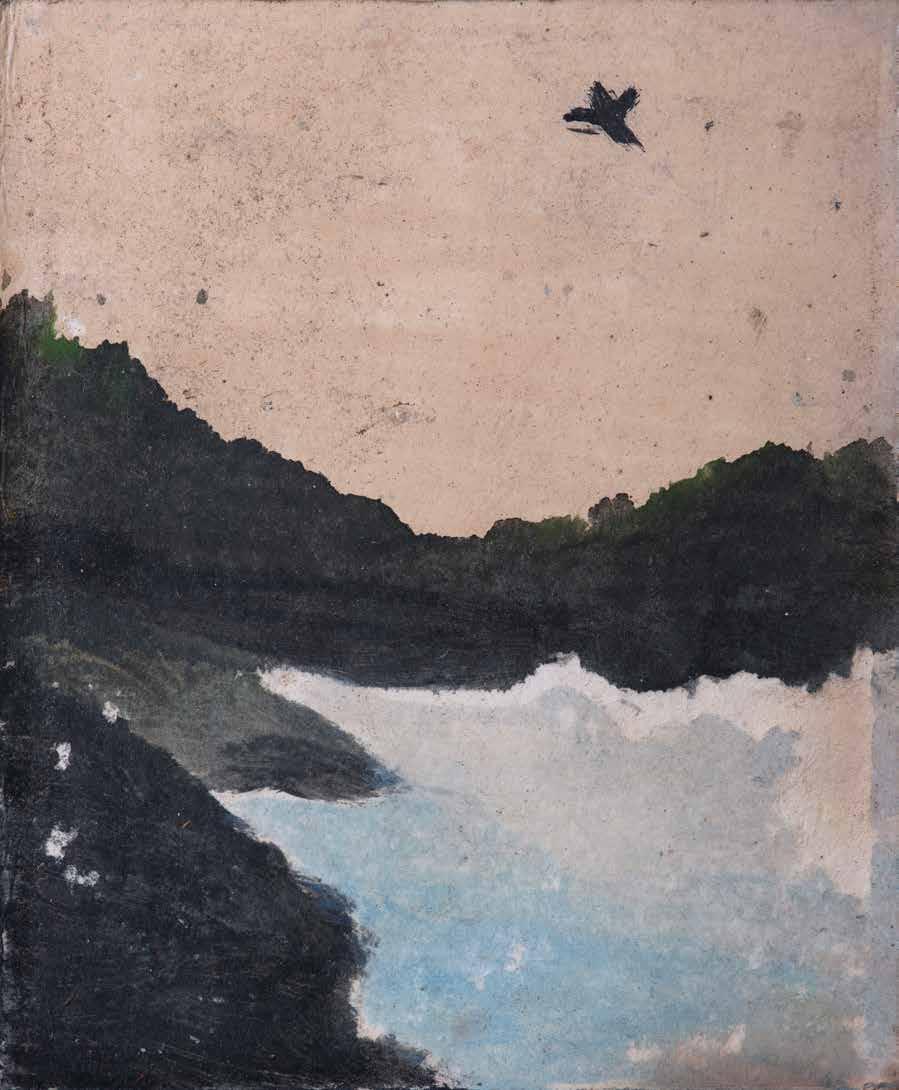

observe now close-up as though standing on a neighboring rooftop to the aforementioned egret perched majestically on his black spindly leg; now from a distance, witness to a flock of birds swooping through the pink night sky from behind a rocky outgrowth [PL. 82]. Horizon lines are everywhere in Walter’s compositions as he shows us how the world bends, curves, and changes before our watchful eye. In Coastal Scene with Boat, Cliffs, and Shorebird, striped, purpleand-blue sea becomes striped, purple-and-blue sky [PL. 36]. Our perspective mingles with that of the cormorant who, his back to us, surveys the sea, and we wonder, who is the protagonist here? This emphasis on frame and perspective is nowhere so evident as in the spool series, compositions executed on the back of circular disks composed of a composite material such as might have been used to insulate car doors or provide support for the bottom of straw baskets. As image supports, these disks resemble portholes or viewing lenses yielding both distant, abstract vistas and close-up views. Often, Walter guides us. In Untitled (Crescent moon) [PL. 37], for example, we peer across the surface of the moon into a black expanse, while, having come down to earth in Untitled (View of trees through open window) [PL. 38], we look over and through a gridded fence at a tree silhouetted against the night sky.

According to scholar and Walter biographer Barbara Paca, when Walter was out sketching, he was received with both awe and fear by his fellow islanders. It was like he could capture your soul, they said. His sketches of birds and animals and people are at once utterly unassuming and at the same time achingly precise. Isolated studies or fragments come together across his diverse body of work to build a universe. With pencil or pen, he expresses the fishiness of a fish through its pursed lips and puffed belly [PL. 27] or the craneniness of a crane with its angular limbs and crooked step [PL. 19]. Here, a fish is shown from multiple angles rising up and dipping down as fish do [PL. 25]; there, barking dogs chase sheep in a chaotic, tumbling herd [PL. 46]. White Bird is so paired down that it is less an image of a specific creature than a portrait of the essence of flight, beak and wings and tail extending across its gray ground in perfect harmony [PL. 20]. For a time, in St. John’s, Antigua, Walter operated a photo booth where he took photographs, made hand-painted signs, and sold small drawings and paintings. A staple of the booth were his alphabet cards, which he drew, photocopied, and hand-colored in multiple variations. “F” for fish and “D” for dog, naturally, but also, “N” for nag, “V” for villa, and “J” for justice. This is the world according to Walter, broken down, classified, and made digestible.

PL.37 Untitled (Crescent moon), n.d.

PL.37 Untitled (Crescent moon), n.d.

And yet, part and parcel of Walter’s world is the way in which things escape our grasp. There is something achingly elusive about Walter’s drawings and paintings, a sense of longing that also runs throughout his written meditations on art and nature. On the sunset:

I try to write, but would a sketch complete, To find that I have ventured in conceit, To catch the sunset splendid in display; Ah soon! To find that eve’ must pass away…. To catch a thought to match that errant thing, That passes faster than a bird on wing.6

On life’s beauty:

So often in dreams and meditation I myself, have seen astounding beauty, That to record by art, such aesthetic seeings, Impertinence should soon die, Leaving me clear channel, to have done. To perform my artistry, trying to capture such infinity.7

What is art’s role in this? Somewhat cryptically, Walter observes:

Just what one sees is what one sees, And seeing art is also having it and hearing it. Someone by nothing is not prone to find an ease, Nothing is seeing something yet not having a bit.

Seeing a work of art is already having.8

It seems that for Walter, seeing is the closest thing to having that is available to us if we understand “having” to mean a non-possessive form of appreciation. Put differently, for Walter, seeing is the most profound way we can connect with the world since it is the mode wherein things are acknowledged but left untouched, like the white bird framed in solitary flight or Walter’s myriad trees which, seen

6 Frank Walter, “My Abode,” unpublished manuscript, February 19, 1963.

7 Frank Walter, “Death and the Universe,” unpublished manuscript, March 23, 1994.

8 Frank Walter, “The Solace of Solitude,” unpublished manuscript, March 29, 1994.

PL. 38

Untitled (View of trees through open window), n.d.

PL. 38

Untitled (View of trees through open window), n.d.

flowering in unique shades of pink and blue and yellow, are infinite and unrepeatable.

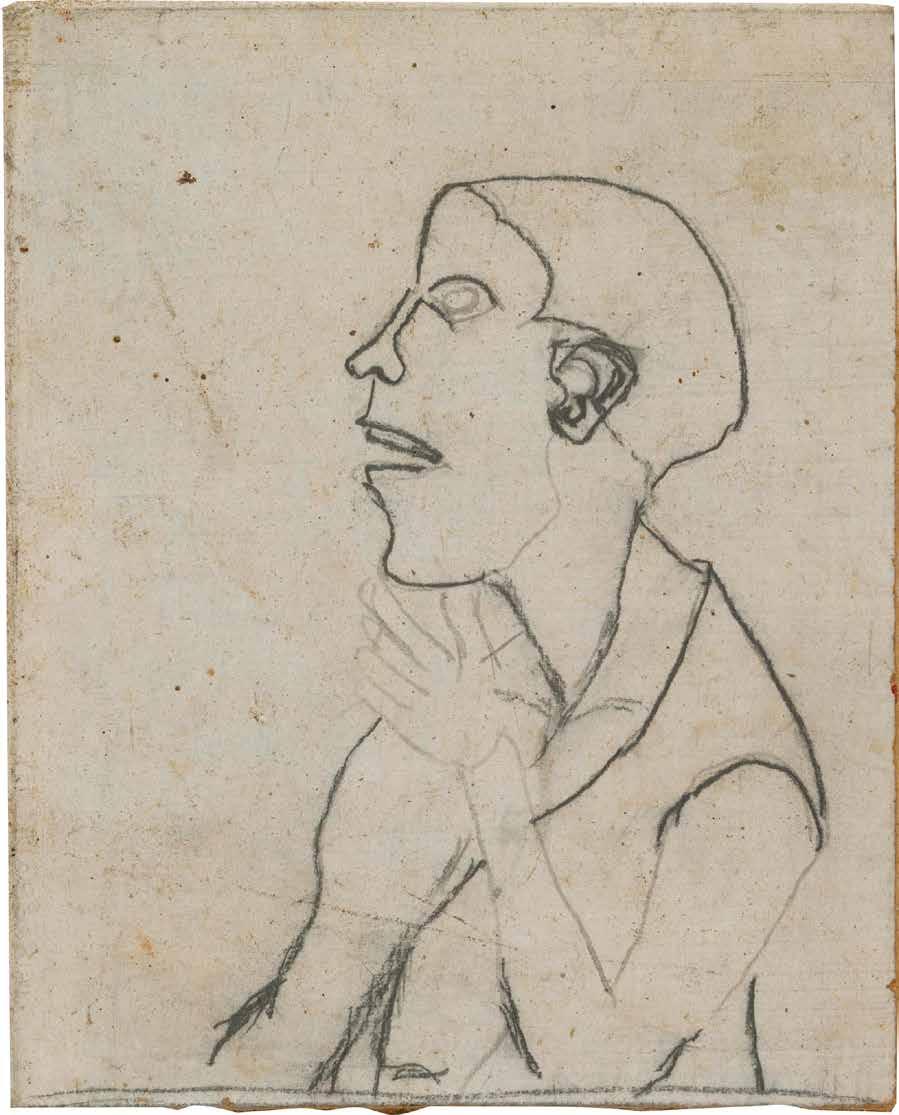

Hilton Als has written that Walter was “awkward with the human form…as if he couldn’t get his hands to see what he saw.”9 This is true. Indeed, this awkwardness is an essential part of Walter’s worldview—this inability to grasp, this melding of reality and the imagination. Take for instance Untitled (Man in profile), a delicate pencil contour drawing of a youth in profile [PL. 39]. The boy looks out with upturned face and open mouth, his faintly-drawn hand resting gently against his chin; he looks as though he is reaching for the beyond. Defined against the cream-colored cardboard by heavy pencil outline, he resembles a kind of Byzantine saint, his frozen, hieratic posture and sightless gaze evidence of a world that is defined as much by spirit as by flesh. The pencil portrait Untitled (African woman with bare breasts) achieves a related affect by different means [PL. 40]. Here, the figure is a maelstrom of movement, her breasts and cheeks swept up in a play of fluid, uncontainable lines.

Walter was a deeply spiritual person and it is impossible to separate his veneration for nature and the world around him from his veneration for God. Walter had many names for God or rather, for the characteristics that he saw as defining God—expansiveness, sublimity, mysticism, and intangibility—characteristics he also associated with his own dreams, the subconscious, his selfdiagnosed schizophrenia, and what he termed the “fourth dimension.” These spaces/phenomena were connected for him in the way they introduced realms beyond the everyday even as he aligned notions of intangibility and sublimity with the beauty he saw in nature. “I began to see balls of light project themselves from my eyes, in pulses, as beautiful as the Rainbow,” he intones in his autobiography.10 Elsewhere, he likens the fourth dimension to the expansiveness of a sea “wherein swims the fish,” concluding that there is no “doubt / That we are vaster than we feel or hear or shout.”11

“I had stretched my imagination beyond reality in my scientific and artistic dreamings,” Walter observed, an expansion that takes

9 Hilton Als, “Water Music: Discovering Frank Walter,” June 2, 2022, David Zwirner website, https://assets.davidzwirner.com/v7/_assets_/davidzwirner/ exhibitions/2022/by-land-air-home-and-sea-the-world-of-frank-walter/watermusic_discovering-frank-walter-by-hilton-als.pdf?func=proxy.

10 Frank Walter, autobiographical transcript (p. 2835), in Frank Walter: Music of the Spheres (Edinburgh: Ingleby / London: Anomie Publishing, 2021), 162.

11 Frank Walter, “The Fourth Dimension,” unpublished manuscript, July 16, 1990.

PL. 39

Untitled (Man in profile), n.d.

PL. 39

Untitled (Man in profile), n.d.

PL. 40

Untitled (African woman with bare breasts), n.d.

PL. 40

Untitled (African woman with bare breasts), n.d.

visual form in Walter’s dialogue with abstraction, both across his body of work and in individual images.12 For example, in the Antiguan landscape Untitled (View of sea through trees) [PL. 2], the trees part to reveal a sea whose waves are nothing but thick strokes of paint barely distinguishable from the light blue sky above while, in Green Sponge Flowering Trees [PL. 1], the texture of sea and sky are reversed with the trees offering a peek-a-boo view into a pinkand-blue colorscape beyond. Similarly, we witness an abstracting across images. The “errant” sun was a favorite subject of Walter’s and, although not intended as a series, together these works tell a story. From an oil-on-photograph in which a red sun sits high atop a mountain [PL. 41], to a painted Polaroid depicting the sun descending behind the trees [PL. 42], to one in which its red crest is barely visible above a landscape of striated blue, yellow, and green [PL. 132], Walter reveals the sun’s dissolution both figuratively and literally. These compositions resonate with Untitled (Yellow land, hot orange pink sky) [PL. 13] an entirely abstract composition that could just as well be titled “Study in Yellow and Orange.” Here, sun and sky create a Rothkoesque landscape, while a small black circle dances along the horizon—the last vestige perhaps of physical presence. In Walter’s studies we know we are looking at sun and sea and land, and yet we also feel, with poet Vladimir Lucien, that, “None of this is real, neither the evening or anything I can say about it. All of it is still just a suggestion of something / other.”13

Walter gave expression to what this other might look like in his galactic series, abstract compositions consisting of geometric shapes like circles, crescents, and stars in bold, opaque colors against flat grounds. MWG Milky Way Galaxy [PL. 16] is one of six paintings in Walter’s Milky Way series in which he envisions the orbit of the planets in golden yellows and deep blacks, while Untitled [PL. 136] is one of three images illustrating Walter’s ideas about nuclear fusion and psycho-geometries that he had researched during the hours he spent in libraries in the UK and Germany. While a visual departure from his studies of the world around him, these images constitute an extension of Walter’s investment in close observation; seeing is for him as much an act of mind as of body. Indeed, this is something he references in his autobiography when he describes processing

12 Frank Walter, autobiographical manuscript (p. 2530), in Barbara Paca, Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man, 1926–2009 (Santa Fe: Radius Books, 2017), 280. 13 Vladimir Lucien, see page 158 in this volume.

PL. 41

Untitled (Red sun, black mountain, gray sea), n.d.

PL. 41

Untitled (Red sun, black mountain, gray sea), n.d.

PL. 42 Red Sun, n.d.

PL. 42 Red Sun, n.d.

the world through his mind’s eye. In his writing and his art, Walter understands true sight along with Derek Walcott as a way of seeing anew, as if for the first time. In the words of Kerry-Jane Wallart, for Walcott, poetry is “a means to restitute the shock and wonder of the self in front of the world, and of itself.”14 This is true of Walter’s painting and drawing as well.

14 Kerry-Jane Wallart, “Derek Walcott’s Another Life, or Writing the Self into a Distance,” Commonwealth Essays and Studies 29, vol. 1 (Autumn 2006): https:// doi.org/10.4000/ces.9593.

PL. 43 Goat, n.d.

PL. 43 Goat, n.d.

PL. 44

Untitled (Work horse), n.d

PL. 44

Untitled (Work horse), n.d

PL. 45 Untitled, n.d.

PL. 45 Untitled, n.d.

PL. 46

Untitled (Dogs), n.d.

PL. 46

Untitled (Dogs), n.d.

PL. 47

Untitled (Dog and bird), n.d.

PL. 47

Untitled (Dog and bird), n.d.

PL. 48

Untitled (Dog and pup), n.d.

PL. 48

Untitled (Dog and pup), n.d.

PL. 49

Untitled (Longhorn cattle), n.d.

PL. 49

Untitled (Longhorn cattle), n.d.

PL. 50 Untitled, n.d.

PL. 50 Untitled, n.d.

PL. 51

Untitled (Seated dog), n.d.

PL. 51

Untitled (Seated dog), n.d.

PL. 52

Untitled (Cat and mouse), n.d.

PL. 52

Untitled (Cat and mouse), n.d.

PL. 53

Untitled (Cat with long whiskers), n.d.

PL. 53

Untitled (Cat with long whiskers), n.d.

A Buzzard, a Hawk, and a Shrike

Lynette Yiadom-BoakyeThe Black Buzzard knew better than to ask awkward questions of sinister strangers, On unfamiliar heathland, On a dark early evening, In late January.

His companion, the Harris Hawk was, in contrast, a hapless creature, overly sociable and given to Pointless banter, blunt inquiry, and Overfamiliarity. All of the time. Regardless of whom and Immaterial of where.

The Shrike, a foreign visitor on winter migration, whom neither of the birds knew at all well, Perched on a branch nearby. He was polite but measured. Content to sit quietly in their company. A mild-mannered bird, the Shrike managed a few pleasantries, short observations, and one word responses. He would laugh or smile softly as and when necessary. But never more than that.

The Black Buzzard, always adept at reading the proverbial room and knowing that this was not the time for controversial musings (the foreign guest being a stranger to them) struck up a suitably banal conversation about the weather.

“It’s too cold. I should have gone away,” he murmured thoughtfully.

“Hmm, yes, it is quite cold,” agreed the Shrike in his unusual and clipped East European accent.

The Harris Hawk, who was known to lack tact and social grace, said to the Shrike, almost accusingly, “So tell us about yourself. We don’t know you, but your reputation precedes you!”

He nudged the Black Buzzard and winked at the Shrike conspiratorially.

The Black Buzzard cringed.

The Shrike bristled slightly, a little taken aback. Shrikes do not care for directness in conversation.

“Not much to tell,” he shrugged and smiled. And then fell silent, shrinking into himself a little.

The Black Buzzard tried to steer the conversation back to safer ground.

“I wonder if we’ll have snow, but perhaps it’s too cold,” he said, a little louder than necessary.

“Mmmm, yes. Maybe,” said the Shrike. And fell silent.

The Harris Hawk ignored them and pressed on with his agenda.

“Come on now, don’t be shy! I’ve heard ALL about you…bit of a dark horse, eh?”

He leaned in to the Shrike, who was a small and diminutive creature in comparison to the tall, muscular Black Buzzard and the fit and imposing Harris Hawk.

The Shrike looked down with unease.

“Err…not really. Just, you know, surviving like everyone else.” And once again, he fell silent.

Untitled (Scotland with white river and trees and two birds in flight), n.d.

PL. 54 PL. 55

Goats Crossing a Forest Road, n.d.

PL. 55

Goats Crossing a Forest Road, n.d.

PL. 56

Untitled (Black and white cow), n.d.

PL. 56

Untitled (Black and white cow), n.d.

The Black Buzzard cut in.

“What’s the weather like for you at home?” he asked the Shrike softly.

The Shrike brightened. “Much colder than here. That’s the reason I came here. Not much to eat over there at this time of year.” He looked like he had more to say, but he caught himself. And fell silent.

“Ah yes! Speaking of which,” started the Harris Hawk, sensing an opening in the conversation, “Don’t they call you the Butcherbird of the Balkans?”

The Black Buzzard shot the Harris Hawk a look of sharp dismay, shaking his head.

The Shrike smiled coldly at the Harris Hawk and steadied his breath before answering emptily, “I couldn’t possibly comment on what they call me, whoever ‘they’ may be.”

The Black Buzzard piped up once more, “Exactly! And why would you? We can’t control public perception…”

The Harris Hawk scoffed at the Black Buzzard. “Pah! It’s a bit more than that though isn’t it? I mean, you and I, as Buzzard and Hawk, are recognized as birds of prey. People expect a degree of menace, of predatory behavior, the whiff of death follows us everywhere. Swooping in and taking a small field mammal. Killing it quickly and eating it. Minimal violence. All in the name of survival. We keep it swift and painless because we need to eat.”

The Shrike looked at both birds with a deadpan incredulity and said, “Yes. So do I.”

There was a frost to his tone that took the Black Buzzard aback. How could a creature so small and sweet-looking exude such effortless malice?

The Harris Hawk hadn’t finished. “Oh, no you don’t! You’re vicious, you pick up your prey, impale it on the nearest thorn or wire fence, and then sit and watch it die in agony. That, my friend, is not at all like us. That counts as cruel and unusual, not survival!”

The Shrike shuffled uneasily and looked to the Black Buzzard for support before retraining his eyes on the Harris Hawk. They were hard, cold, blue-black eyes.

“It’s my feet you see,” began the Shrike in his soft but deep and monotonous tone. “They’re not very strong. You see, I can’t hold my prey down long enough to incapacitate it. So, you see, I need to erm…find other means to hold it, you see?” The apologetic note was through inflection rather than warmth.

The Black Buzzard spoke before the Harris Hawk could respond. “Yes, of course friend. That makes perfect sense. Of course, you kill in the way that you do as a matter of necessity. So you don’t take pleasure in it, do you?”

The Shrike shook his head very slowly, almost imperceptibly, and smiled. “Not at all,” he said.

The Black Buzzard felt a chill once again. He knew that he didn’t entirely believe the Shrike.

The Harris Hawk, unmoved by the Shrike’s explanation, went on, “No, I saw you. Earlier, over there.” He motioned to a barbed-wire fence in the distance.

The Shrike looked over at the fence and then fixed his eyes back on the Harris Hawk. His earlier, more nervous demeanor had been replaced by a stillness, as though keen to conserve his energy.

“Where?” he asked the Harris Hawk without any urgency.

“You know where, that fence over there. You had a small bird, a Robin!” The Harris Hawk was agitated.

“When?” asked the Shrike, still unconcerned.

“You know when! Lunchtime! You had a Robin, and you impaled him on that sharp piece of wire, I saw you!”

The Shrike continued to stare blankly at the Harris Hawk.

PL. 57

Untitled (Scotland with white river and trees), n.d.

PL. 57

Untitled (Scotland with white river and trees), n.d.

The Harris Hawk turned to the Black Buzzard, hoping for corroboration. “He impaled that little bird and watched him die. He sang as he watched him. What type of bird sings to his dying prey?”

The Black Buzzard tried to conceal his distaste at the Harris Hawk’s recollection of what he had witnessed. Looking back at the Shrike, he tried to reconcile the appearance of the diminutive bird with the homicidal maniac of the Harris Hawk’s account. The Shrike shrugged lightly. He said nothing.

“Go on, admit it!” urged the Harris Hawk.

The Shrike shuffled sideways on the branch, looking down at his weak little feet as a reminder and then back up at the Black Buzzard. He fixed his hard black eyes back on the Harris Hawk.

Silent for a time.

And then he began to sing.

The Shrike sang a song so transcendent the Black Buzzard felt sure that his heart might burst.

The Shrike sang a song so beautiful that all the birds on the heath fell silent to listen in wonder.

The Shrike sang a song so sweet it sliced the twilight shade asunder.

The Shrike sang a song so heartbreaking that the Harris Hawk stared, beak wide open, mesmerized.

When the Shrike finished his song, allowing the last few notes to melt and drift heavenwards, the Harris Hawk coughed, cleared his throat, and shook the melody from his intoxicated head.

“That was…” said the Black Buzzard, “that was divine.”

The Shrike, bashful, smiled down at his weak little feet and said nothing.

“Yes, well,” said the Harris Hawk, “That’s how you trap them, isn’t it?! Lure them in with sweet song, impale them on a spike, and watch them die!”

“Now steady on,” said the Black Buzzard in stern rebuke, “I think you’ve made your point. That’s quite enough of that.”

The Shrike smiled and shook his head regretfully. “It’s ok,” he said to the Black Buzzard. “He’s entitled to his opinion. Can’t convince everyone. Enjoy your evening, it’s been nice talking to you. Good night.” The Shrike flew away in the direction of some brambles near an old barn below.

“Good riddance!” the Harris Hawk called after him.

The Black Buzzard turned to him. “Did you need to be so rude to him? He was embarrassed.”

“What about the Robin?” shrieked the Harris Hawk. “Dying a slow and undignified death? What about his embarrassment?”

“We all kill to eat,” said the Black Buzzard. “Are we really that much better? Can we really take the moral high ground on this?”

The Harris Hawk sighed impatiently. “For the umpteenth time, my dear brother Buzzard, we are not psychopaths, whereas our sweet little friend the Shrike is a psychopath. Killing is the main objective for him, food is a mere byproduct.”

The Black Buzzard was too tired to argue further. He was too wise of a bird not to know when he couldn’t win.

He was tired, and it was late, so he excused himself, bade the Harris Hawk goodnight, and flew off to bed.

The Harris Hawk, quietly triumphant and utterly unrepentant, settled down for the night.

The Black Buzzard woke with a start the next morning. It was late, around 7:30. An audible commotion from the heath below had roused him. He flew down to see what was happening. Perching on the low bough of a tree at the edge of the heath, he could see a party of birds gathered around a circular clearing in the grass. Looking

PL. 58

Untitled (Lavender sunset meadow), n.d.

PL. 58

Untitled (Lavender sunset meadow), n.d.

PL. 59

Fence with Fish and Birds, n.d.

PL. 59

Fence with Fish and Birds, n.d.

more closely, he could see a metal rod coming out of the ground. At the base of it was the skewered body of the Harris Hawk, a long trickle of blood leading away and pooling nearby. Stiff with rigor, he was long dead.

All of the birds were perplexed. So many aspects of the scene were strange. The apparent staging.

The fact that it was unlikely a suicide. And even less likely an accident.

The birds agreed that the method of killing matched that of the Shrike, but that it could not have been him because he was far too small and his little feet were far too feeble. Furthermore, he was a bird of prey who only killed to eat, and the body of the Harris Hawk was intact.

The Black Buzzard watched and listened and said nothing.

The Black Buzzard knew better than to share his hypotheses, so he kept them to himself.

The Black Buzzard was smart enough to know that there was no such thing as a coincidence. Not like this.

As the birds stood around, deep in speculation, only the Black Buzzard noticed the familiar, sweet, and mesmeric song of the Shrike trickling softly from a treetop above.

PL. 60 Green Water Hurricane Sky, n.d.

PL. 60 Green Water Hurricane Sky, n.d.

PL. 61

Untitled (After seeding), n.d.

PL. 61

Untitled (After seeding), n.d.

PL. 62

Untitled (Shark), n.d.

PL. 62

Untitled (Shark), n.d.

Untitled (Dog and wolf-like animals), n.d.

PL. 63 PL. 64

Untitled (Man milking a cow), n.d.

PL. 64

Untitled (Man milking a cow), n.d.

PL. 65

Untitled (Man on beach with bats), n.d.

PL. 65

Untitled (Man on beach with bats), n.d.

PL. 66

Untitled (Three buzzards), n.d.

PL. 66

Untitled (Three buzzards), n.d.

PL.67

Untitled (Black bird in tree), n.d.

PL.67

Untitled (Black bird in tree), n.d.

PL. 68

Untitled (Coconut tree), n.d.

PL. 68

Untitled (Coconut tree), n.d.

PL. 69

Untitled (Blue and pink sky, green land), n.d.

PL. 69

Untitled (Blue and pink sky, green land), n.d.

PL. 70

Untitled (All of god for me), n.d.

PL. 70

Untitled (All of god for me), n.d.

Frank Walter’s Constellation

Barbara PacaI The Power of Frank Walter’s Drawings as Essays

Frank Walter was prolific because he had to be. He was an artist.

He was spontaneous. He understood the sophistication of simplicity. Artists are drawn to him because they too crave immediacy.

—Jules Walter, Sr.

Frank Walter’s closest kin and childhood friend, ninety-fiveyear-old actor and raconteur Jules Walter, Sr., translates his cousin’s artistic masterpieces as layers of awareness that expand and contract the viewer’s mind with an unimaginable breadth of subject matter—breaking all rules of geography and smashing sound and time barriers.

There is a direct connection between seventeenth-century herbariums and Frank Walter’s palm studies, drawings, and paintings. As one of the most promising students ever to attend the Antiguan Grammar School, Walter flourished under the guidance of Headmaster Gilbert Auchinleck, particularly in horticulture and Latin. Jules recounts Auchinleck’s romantic stories of how earlynineteenth-century planter Dr. Willis Freeman sought a better world by importing the stately Phoenix reclinata (date palm) to Antigua. At the same time, Freeman was also dreaming about bringing camels to the island to assist in the sugar industry. Imbued with a nostalgic idea of Freeman, Walter added truth by documenting the sophisticated growth patterns of the palms, thereby revealing a serious level of study and bringing you to the climate where they flourish. In their tall silhouetted form, Walter’s palms elevate

PL. 71

Untitled (Man swimming in red trunks), n.d.

PL. 71

Untitled (Man swimming in red trunks), n.d.

the viewer, his visual essays on these monocots making you gaze upwards toward the sky.

As with many artists, drawing was a form of relaxation and at the same time stimulating for Walter. He had a gift for extracting unspoken elements of his portrait sitters to the point of discomfort— some felt he was getting too close to their soul. Dominica is a place where people harbor strong spiritual beliefs, and many who knew Frank Walter from his time there from 1961 to 1968 regarded him as a “supernatural,” stating that when studiously making a sketch of a person he had an uncanny ability to express every detail and gain control over their spiritual being. Among the elders, there is a belief that he carried “magic” in his sketchbooks. They cited how he would climb up into the forest, felling trees on his property using not an axe, but incantations from his red notebooks.

Always sketching, it was as though Walter’s hand had to keep moving in order to fulfill a continuous and spontaneous artistic desire. He had to maintain this coordinated effort through simultaneously composing, writing, recording, carving, sculpting, and painting.

Walter’s art is concurrently featured in Paris at the Bourse de Commerce’s Le monde comme il va (The World as It Goes), a group exhibition of works from the Pinault Collection curated by Jean-Marie Gallais. This famous quote by Voltaire is used here to express “the acute awareness of the present.” Gallais provokes the visitor into thinking through this paradox, placing Walter among Martin Kippenberger, Marlene Dumas, and Peter Doig in a long chamber with Walter’s three portraits in direct dialogue with Doig’s monumental Pelican (Stag). In an earlier exhibition, Gallais first established a dynamic tension between Doig and Walter by engaging Doig’s epic Orange Canoe with a set of nineteen of Walter’s miniature Polaroid paintings (each 8 x 10 cm). Gallais organized five sets of triptychs—and at roughly the center, one tiny image of a ruckenfigur of Walter cradled in the spreading branches of a tree. In this assemblage, Walter challenges the vast scale of Orange Canoe, and a shared profound silence and power connects the work of these two artists.

Peter Doig and Frank Walter’s lines also intersect through a painterly awareness of their shared origins. Rendezvous Bay remains a Walter property to this day, but it comprised the Doig plantation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Set just inland from the long expanse of pure white sandy beach at Rendezvous Bay are the Doig ruins, with eighteenth-century stone structures scattered close

PL. 72

Untitled (Young Castro), n.d.

PL. 72

Untitled (Young Castro), n.d.

(Enslaved woman), c. 1982

PL. 73 Untitledto the beach. The foundations of an old sugar mill and a domestic dwelling structure survive in this unlikely spot. Centuries overlap in this surreal landscape, as uphill from the sugar mill lies buried in the slopes the last unexcavated Arawak site in Antigua, which dates to circa 250 AD. The set of four Frank Walter landscapes in Peter Doig’s personal collection tell us all we need to know about Rendezvous Bay and Walter’s natural world—during the day but more at night— and speak of a shared history made more compelling through their connection on an unconscious level [PLS. 74–77].

II Josh Smith and Frank Walter’s Ghost

Frank Walter was able to capture the sound in his paintings. The way things move in Antiguan nature.

The sound is very distinctive—the way that vegetation rubs together. He got that into his paintings, which is a miracle.

—Josh Smith, Antigua, January 2024

When Josh Smith entered Frank Walter’s world, he got it immediately. According to Smith, a studio doesn’t need walls–it needs to be a safe place. And during Walter’s lifetime, this was almost always his privileged environment. For Smith, the experience of Walter’s studio actually begins when you enter his property: “The moment you step off the dirt road and onto the stone at the entrance to the hill.” The site is only accessible via foot, which according to Josh makes it all the more spiritual, as one must climb upward, crossing onto a narrow path edged with plumes of grass that leads up to Walter’s house and studio platform. Beyond that, the circuitry of paths leading up to his relation’s house and the long path leading down to Rendezvous Bay were also integral pieces of Walter’s daily meditation and studio experience.

Smith recognized that Frank Walter’s world was carefully designed, calibrated by the genius of an engineer and designer who understood the spatial requirements of one person. As a solitary being Walter was obsessed with refining the dimensions of the rooms and the spring of the floor for himself and no one else. And as for his art studio, why should he build a roof over the space? Indeed, who needs walls? The world that Smith found himself colliding with was in a state of decay—it had already begun to fade with the passing of Frank Walter fifteen years ago. However, for Smith, Walter’s spirit remains—evident via the smell of wood, the small scale of the chambers, the interlinking of interior worlds set in sharp contrast to

PL. 74

Landscape Series, Scotland (Sea, Cliffs, and White Birds), n.d.

PL. 74

Landscape Series, Scotland (Sea, Cliffs, and White Birds), n.d.

PL. 75

Landscape Series, Scotland (Black Bird with Cliffs and Obelisk), c. 1968–76

PL. 75

Landscape Series, Scotland (Black Bird with Cliffs and Obelisk), c. 1968–76

PL. 76

Landscape Series, Scotland (Bay and Bird), n.d.

PL. 76

Landscape Series, Scotland (Bay and Bird), n.d.

PL. 77

Landscape Series, Scotland (Beach with Birds), n.d.

PL. 77

Landscape Series, Scotland (Beach with Birds), n.d.

expansive landscapes that span the width of the sea, illuminated at night by distant stars and galaxies.

Living amidst a profusion of found objects (some regarded as trash by others) is artistic lifeblood to both Smith and Walter, and we see this in all aspects of their work. In Frank Walter’s 1993 poem included in this volume, “The Kindness of the Sea,” he writes about his delight as a beachcomber gathering driftwood and seashells for his own artistic creations. As with Smith, everything within Walter’s reach had potential as a work of art, even if it appeared like chaos to others. As with Walter, Smith needs to surround himself with materials, admittedly to the point of what might be perceived as insurmountable clutter. For Smith, everything is in perfect order, and the worst thing would be for someone to try to “clean” his space. Smith understands that for Walter, as a polymath, this spiderweb of apparent disorganization must have been extreme and always in critical balance, micro-managed in his absolute solitude.

As preparation for his artistic conversation with Walter at The Drawing Center, Josh Smith spent time in Antigua with his partner, artist Megan Lang. Lang, too, possesses incredible insight into Walter and was immediately aware of the way in which the natural world and its acoustics strike one from all angles when on his property. She noted how Walter’s work plays with the intensely intimate scale of his interior spaces contrasted with the vast landscapes just beyond his doorstep and also how it showcases the rustic charm unique to Antigua—desiccated window frames and eighteenth-century stone arches—brilliantly repurposed as framing devices for many of his landscape paintings.

Beyond a shared sensitivity and thoughtful approach to art, sketches and paintings of palms are seen throughout the work of Smith and Walter; they both explore the unlikely shape and quick growth pattern of these lanky monocots. Similarly, their haunting visions of otherworldly ghouls has an arresting immediacy, and we are made urgently aware of the need to reconcile these visions in our own head. Hovering somewhere above the stylistic similarities is a sense of humility and preoccupation with finding the truth at all costs. Smith and Walter seem connected through their relentless search for the essentials. The elements of what it means to be a true artist is revealed as their work meets on this higher level.

PL. 78

Untitled (Purple nocturne with chartreuse foliage), n.d.

PL. 78

Untitled (Purple nocturne with chartreuse foliage), n.d.

Artists gravitate to the mystery and the naked creativity of Frank Walter.

He wasn’t a landscape artist. He wasn’t an abstract artist. He was uncategorizable.

He was probably fighting with himself about that.

—Josh Smith, Antigua, January 2024

In the 2017 Venice Biennale catalog, neurosurgeon Caitlin Hoffman wrote about Walter as an artist who suffered not from madness, but from genius. She commended his vigilance in staying close to his work; as well as his family who made it possible for him to live in solitude in a pristine environment. Walter was a polymath and experienced the kind of background noise that geniuses have to let out when they live in their heads at all times. The connection to Princeton’s John Nash, legendary for his breakthrough work in mathematics and game theory, is made clear in the installation of Walter’s manuscripts in the To Capture a Soul exhibition, a tapestry that reveals how Walter’s mind toggled through multiple thought processes.

On a superficial level, Walter’s environment always struck me as a welcome relief from tourist shops and tiki bars. On a deeper plane, Walter’s austere world was one where chatter was eliminated, and centuries collided in an unforgettable way. There is no way to recreate Walter’s environment because it was that pure and all-encompassing and true to the old Antigua. With its almost clandestine inward-looking chambers and profound connection to place, Frank Walter’s studio and home read as a roadside shrine. Walking into his home and studio always felt like entering a stage set from another time, and during the years I visited him on the hill there was always a sense of slowing down and never wanting to leave. Memories of his world are reminiscent of photographs from the nineteenth century, when hospitality was imbued with civility, intimacy, long bouts of silence, and a quiet pride.

Josh Smith: Life Drawing

I’m a painter and an admirer of the work of Frank Walter. I’ve assembled here a selection of drawings and three prints. Most of the drawings I make are small. A lot of the work was drawn on torn paper leftover from printmaking. I keep stacks of this paper around and draw sometimes when I have to sit somewhere for a while. The drawings in this group range from the late 1990s to now. There are not very many because I did not want to overwhelm the situation. With Frank Walter’s work all around, this scale makes more sense. Pared down, the selection represents some favorite subjects: palm trees, horses, grim reapers, animals, cityscapes, fish, and boats—all of which have worked their way into my paintings. Drawing anything repeatedly is how rhythm is found, nurtured, and expelled. Working like this is either building up towards a painting or coming back down after working. Drawing is a therapeutic luxury. Yes, the drawings are sketchy, but this is how it is. Everything I make references the next thing I’m going to make. Therefore everything is both a sketch and a completed work. That’s what I discovered assembling this show.

JOSH SMITH

10 / 11

Both: Untitled, 2018–19

1

Untitled, c. 1999

Marker and graphite on paper

7 3/4 x 12 inches (19.7 x 30.5 cm)

2

Untitled, 1999 Charcoal on paper

5 3/4 x 7 1/2 inches (14.6 x 19.1 cm)

3

Untitled, 2013–23 Graphite on paper

5 1/4 x 4 1/2 inches (13.3 x 11.4 cm)

4

Untitled, 2022 Monotype on Rives BFK

40 1/4 x 57 1/2 inches (102.2 x 146.1 cm)

5

Untitled, 1996 Ink on paper

5 1/4 x 5 1/2 inches (13.3 x 14 cm)

6

Untitled, 1996

Graphite and driveway sealer on paper 4 1/2 x 7 inches (11.4 x 17.8 cm)

7

Untitled, 2016

Marker and watercolor on paper

6 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches (16.5 x 14 cm)

8

Untitled, 2007