Ways of Seeing

Three

Three

Jack Shear

Arlene Shechet

Jarrett Earnest

Introduction by Claire Gilman

I never attended a curatorial studies program, but my long and enormously enjoyable studies in the history of art have taught me that meaning is made in exhibitions of art that doesn’t talk back (drawings, for example) through juxtaposition. Art history, after all, is an Enlightenment discipline, born in an eighteenthcentury Europe inspired by the logical minds of scientists and philosophers who believed that answers to all questions could be found through collection, classification, comparison, and contrast. For art aficionados two hundred years ago, as now, a fundamental way to understand a work of art derives from analyzing what it looks like and what it does not look like. More recent additions to this canonical intellectual scaffolding include historical context, the biography of the artist, who is looking at the work, and significantly, who has chosen and arranged it for viewing. As a curator, I have clung to the belief that meaning can be made—arguments concerning the periodization of our history of visual culture, the relative value of an individual work of art as opposed to another, etc.—through the arrangements of works of art in a gallery. Exhibitions for me are not unlike essays that argue the point of view of the curator, just as an academic paper is the vehicle for the apercus of its author. When the artist and drawing collector Jack Shear agreed to lend his collection of more than a thousand drawings to The Drawing Center for an exhibition, we were naturally thrilled at the prospect of presenting works by Ingres, Cezanne, Seurat, Picasso, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Julie Mehretu, and many other major artists. But inspired by Jack’s well-known interest in non-canonical displays of his collection and his devotion to teaching through a handson relationship to great art, the team at TDC thought to use the opportunity to conduct a real-time experiment in curatorship. We

decided that our exhibition of Jack’s collection would unfold in three distinct iterations. Three different sets of eyes and minds would each create an exhibition using the raw material of Jack’s superb group of drawings dating from the Renaissance to the present. Jack, the collector, would hang the first take; Arlene Shechet, a sculptor and gray eminence in the New York art community, would present the second; and Jarrett Earnest, an art historian and queer theorist, would execute the third. In addition, a fourth member of this team, the great critic, writer, curator, and appreciator of the arts writ large, Hilton Als, was asked to “curate” a group of ten writers, each of whom would write about several works in the collection—texts that we would publish as a literary version of the exhibition.

Under the able direction of TDC’s Chief Curator, Claire Gilman, assisted by Curatorial Associate, Isabella Kapur, and the redoubtable Mary Anne Lee of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, The Drawing Center played host to three remarkable displays of more than two hundred drawings in total. Although none of us knew what to expect, the results of our experiment, documented in this volume along with statements from the three curators as well as Claire on behalf of The Drawing Center, were fascinating, even revealing. Although there was some overlap in the works they selected, each curator created a distinct exhibition, hanging drawings in very different ways based on form, content, provenance, color, and simple idiosyncrasy. With each fresh juxtaposition, new meanings were derived, new details were noticed, and new contexts were created, even for some of the most canonical images by the most well-known artists.

On behalf of The Drawing Center and the hundreds of delighted visitors our institution welcomed over the past four months, we thank Jack for his enormously generous gesture of bringing a portion of his collection to The Drawing Center for the public to enjoy. Thanks also go to The Drawing Center team, led by Claire Gilman, who worked tirelessly and joyfully to make this experiment a reality. Jack is widely admired not only as a drawing connoisseur of the first water, but as a catalyst for new scholarship and new ideas in the discipline of drawing. Those who recognize this are legion, and some of them were key in helping TDC make the exhibition a reality. Our gratitude goes to Kathy and Richard Fuld, Agnes Gund, the Low Road Foundation, Matthew Marks, Christie’s, Emily Rauh Pulitzer, Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Pace Gallery, whose donations made all the difference. Finally, it is my pleasure to single out Frances Beatty Adler, an art historian, collector, art dealer and

drawing enthusiast who is also one of our longest serving board members. It was Frances who insisted on taking some of us to see Jack’s collection in situ at his studio upstate, and it was her idea to embrace Jack’s offer to make a show with it. Thank you, Frances, for your passion.

It has been an honor and a pleasure to work with our four guest curators: Arlene Shechet, Jarrett Earnest, Hilton Als, and Jack himself. How lucky we were to have had the chance of showcasing your visions through the language of great drawing! Ways of Seeing: Three Takes on the Jack Shear Collection is surely one of those projects that could only happen at The Drawing Center, and we are so proud to have had the chance to do it with all of you.

—Laura Hoptman, Executive DirectorIn Ways of Seeing, John Berger’s timeless reflection on the power of images, the British art critic, painter, and author succinctly explains the complex relationship between seeing and understanding: “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.”1

According to Berger, this is in part because looking is an active choice that is dependent on the changing world around us. “We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are.”2 As a result, images themselves change, their “story” fluctuating according to the circumstances surrounding their reception. “The meaning of an image is changed according to what one sees immediately beside it or what comes immediately after it. Such authority as it retains, is distributed over the whole context in which it appears.”3 Taking this one step further in Bento’s Sketchbook, an exquisite rumination on drawing interspersed with aphorisms by “Bento” Spinoza, Berger quotes the philosopher: “The more an image is joined with many other things, the more often it flourishes.”4 This is particularly true, it would seem, when the images in question are drawings, drawing being an art form that, according to Berger, is fundamentally open and extensive rather than closed and contained. It is “a manner of searching”; “a form of probing”; and, generally, impelled by an

1 John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Company and Penguin Books, 1972), 1.

2 Berger, Ways of Seeing, 3.

3 Berger, Ways of Seeing, 29.

4 Berger, Bento’s Sketchbook (New York, Pantheon Books, 2011), 65.

“imaginative movement” both on the part of the author and the viewer who perceives it.5

Berger’s reflections are the inspiration for Ways of Seeing: Three Takes on the Jack Shear Drawing Collection, a three-part exhibition focusing on the rich collection of drawings that artist, curator, and collector Jack Shear has built over the past half-decade. Shear’s interest in the artist as collector is longstanding. In 1999, he co-organized Drawn from Artists’ Collections at The Drawing Center, an exhibition that highlighted the personal, often idiosyncratic way in which artists collect the work of their peers and forbearers. To date, Shear’s collection consists of nearly one thousand drawings dating from the sixteenth century to the present, and includes contributions by such diverse figures as Edgar Degas, Kazimir Malevich, Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel, Stanley Whitney, Eugène Delacroix, Alice Neel, Pablo Picasso, Vija Celmins, Lee Bontecou, David Hockney, Tom of Finland, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Robert Gober, Jan Toorop, Elaine de Kooning, and Walter Price, among many others. In his studio in upstate New York, Shear has adopted an eccentric approach to hanging his collection, placing works alongside, directly on top of, and abutting other works on the basis of intuited visual affinities regardless of context or historical accuracy. Describing his hanging method, Shear has likened the installation process to working with the alphabet, in that, in putting drawings together, you see things that you wouldn’t see otherwise. He has also likened collecting to approaching artists as though seeing their work for the first time.6

Ways of Seeing: Three Takes on the Jack Shear Drawing Collection foregrounds Shear’s intuitive approach by staging three distinct curatorial interpretations of the collection. Over the course of the exhibition’s fifteen-week run, Shear himself, the artist Arlene Shechet, and the critic and curator Jarrett Earnest each presented an exhibition chosen from Shear’s holdings. In each case, the curators had free rein to choose the works on view and to decide the way in which these works were displayed and amplified. The results were extraordinary as much for what remained the same between each iteration as for what differed. Shear set the tone bringing his singular approach to his installation at The Drawing Center and creating thoughtful constellations whose meaning unfolded in time. From the beginning, Shear was adamant that there be no wall labels thus

placing the onus on the viewer to look first and seek information second. His emphasis on the power of looking stripped of anecdote was reinforced by his anchor image, David Hockney’s Man Drawing from 1965, in which a man confronts a blank wall on which he draws lines of different lengths and thicknesses, testament to drawing laid bare.

Both Shechet and Earnest followed Shear in leaving the galleries free of information. Like Shear, Shechet took a personal approach, bringing her perspective as a sculptor to bear on the space of The Drawing Center by installing hand-carved wooden benches to connect the center of the room with the walls hung with drawings. Her intervention created a three-dimensional drawing in itself, within which visitors could gather to reflect and repose. Inspired by Giorgio Morandi—whose still-lifes Shechet has described as meditations on the interrelationship of all things—Shechet hand painted the walls in grayish hues, providing a varied ground within which the drawings read like incidents in a landscape, offering moments of connectivity and intimacy.

Finally, Earnest took the fundamentals of drawing as his starting point, organizing his installation around two drawings: one by Henri Michaux and the other by Vija Celmins. Beginning with Michaux, the viewer followed a path of drawings along the south wall, moving from openness to precision. Beginning with Celmins, visitors journeyed along the north wall from clarity and containment to the dissolution of the mark into the surface. To reinforce these complimentary paths, Earnest split the gallery in half, painting the walls in inverse gradients of dark and light gray. In the rear gallery, color was the guiding principle, with yellow and purple walls providing an intentional ground.

Taken together, the three installations brought Berger’s words to life, revealing in real time the role of personal vision in the presentation and reception of art. It was wonderful to see old friends from previous installations hung in new contexts (of the two hundred plus drawings shown over the course of fifteen weeks, fifty-nine drawings appeared in two takes, while three were in all three takes) and equally enlightening to give up trying to recall what had been on view before and simply relish new relationships and encounters. Ultimately, Ways of Seeing offered a testament to the uncontainable power of drawing, reinforcing the fundamental truth that interpretations of art are always, at their core, impacted by our own sensibilities and experiences, and that the way in which we see is ongoing and ever-changing.

To Jack, Arlene, and Jarrett, I extend my heartfelt gratitude. What a powerful experience this has been. Thank you Jack for allowing us to show your work and for permitting us to invite others to offer their takes on the astounding, eclectic, wide-ranging collection you have put together with deep attention and love. Thank you Arlene and Jarrett for being so enthusiastic about this project from the start and for giving it your all every step of the way. The three of you indeed taught us new ways of seeing and demonstrated the power of drawing to move us over and over again.

My gratitude also extends to a number of individuals who supported this exhibition in various ways. Thanks to Frank Appio, Adam Boese, Allison Wucher, and above all, Mary Anne Lee, from the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, for ensuring that putting together this exhibition was a smooth and enjoyable experience. Thanks also to Cassandra Smith, Head of Collections and Exhibitions, and Carter Foster, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, at the Blanton Museum of Art; and to Prithi Gowda, Emily Brownawell, and Cara Kuball from Arlene Shechet’s studio. Finally, a huge thanks to Frances Beatty Adler for encouraging us to travel to Spencertown and to Alex Adler for being our very knowledgeable chauffeur.

At The Drawing Center, the entire staff deserves my appreciation. Thank you especially Isabella Kapur, Curatorial Associate, for once again displaying her extraordinary research and organizational skills, and Joanna Ahlberg for navigating this complex two-part publication with enthusiasm, insight, and grace.

Finally, I would like to extend my gratitude to The Drawing Center’s Board of Directors as well as the funders whose support was fundamental to the creation of this exhibition and the accompanying publications: Kathy and Richard Fuld, Agnes Gund, the Low Road Foundation, Matthew Marks, Christie’s, Emily Rauh Pulitzer, Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, and Pace Gallery.

Ways of Seeing: Three Takes on the Jack Shear Drawing Collection is about vision—about looking and seeing. This exhibition is composed of 132 drawings ranging in date from the sixteenth century to the present.

There are many strategies for the way an artist approaches a drawing: how to make marks and how to respond to a blank sheet of paper. Here, on the title wall, is a David Hockney drawing called Man Drawing from 1965. If you look closely, you can see that the man— probably Hockney himself—is experimenting with different kinds of lines and line-making. This idea of an artist confronting the blank page is the touchstone of this exhibition.

When I came into The Drawing Center to install this show, I didn’t know exactly how I would configure the exhibition, only that I would anchor the main gallery space with one group of images depicting the male form and another group depicting the female form. Initially, I brought twice the number of drawings we actually installed, so I had many options to work with in the galleries. I wanted the installation to respond directly to the walls and the space.

When I install an exhibition of my drawings collection, I like to have the art handlers hold the frames in place so I can compose the space visually in a process that is like creating a collage on the wall. The approach is similar to Matisse’s when, at the end of his life, he would direct his assistants to put pieces of color paper on the wall. I play with the composition until my eye tells me it’s right. Ellsworth

[Kelly] was often asked: “How do you know when an artwork is finished?” He would say, “When you aren’t able to make any other choices.” This is how I recognize that an installation is complete and that I’ve arrived at the best way for the objects to hang together on the wall.

At first, this installation might appear to be a traditional Victorian, salon-style hang, yet as one spends more time in front of the works, the juxtapositions come into focus and the stories begin to unfold. The groupings are like sentences or an alphabet. An installation creates a word or a story when you put the images together in a particular way.

To encourage seeing over knowing, this exhibition does not include any wall labels identifying the artworks. Without labels, it is fascinating to see which drawings visitors respond to and ask about. It has nothing to do with how famous the artist is or the particulars of the artist’s identity but rather a visceral reaction.

In fact, I’ve dissuaded visitors from walking through the installation with checklists or guides. I want viewers to use their eyes to see if they hate a piece or love a piece. Maybe they recognize the artist, maybe they don’t, but by looking first and reading later you create a truer, more memorable visual story. Your experience of the works changes what you know about a drawing or an artist and vice versa—what you know about a drawing or an artist changes your experience of the work.

Now to the drawings—this first wall is a tribute to artists who have passed away this past year: Christo, Robert Bechtle, and Susan Rothenberg as well as Barry Le Va, whose work is in the back gallery. While each work on paper is interesting in itself, when you connect them physically, they become interdependent, making the groupings more dynamic. It brings the works alive in a new and different way. Installing works so that their frames touch is an unusual strategy for exhibition making. To me, the forced connection between works based on their placement creates connections that are meaningful and visually exciting.

This next wall includes both famous and lesser-known artists. To the far left is a watercolor by LA artist Aaron Morse, and at the far right is an Andy Warhol Skull next to an amazing Charles Demuth still life. Demuth is probably one of the greatest watercolorists in the pantheon of American artists. This is a work you need to study up close to see how he applied the watercolor: to appreciate what he left untouched and what he chose to focus on. I juxtapose it with the Warhol to create a meditation on death, or vanitas. Placing the skull next to these ripe fruits and flowers that are going to wither and die creates a different narrative from what you would have if the drawings were viewed separately. In this group, I also make a connection between Rashid Johnson and Cy Twombly. There’s a quality to Johnson’s mark making that is reminiscent of Twombly’s later work. Twombly moves from discrete marks to big rhythmic gestures—and I see that with Rashid Johnson as well. Next to the Twombly is a work by Julie Mehretu, who is known for dense and layered compositions. This drawing on Mylar is like an explosion or a manifestation of energy.

As we move to the neighboring wall—which is primarily a wall of abstraction—we have Brice Marden, Sol LeWitt, Jasper Johns, and Agnes Martin. The Jasper Johns, which is also on Mylar, has a kind of grid that sits over its subject. When you look closely, there are drips across the image, which you can tell are very controlled: they come

up from the bottom, the side, and down from the top of the paper. It is a beautiful surface and masterful use of material.

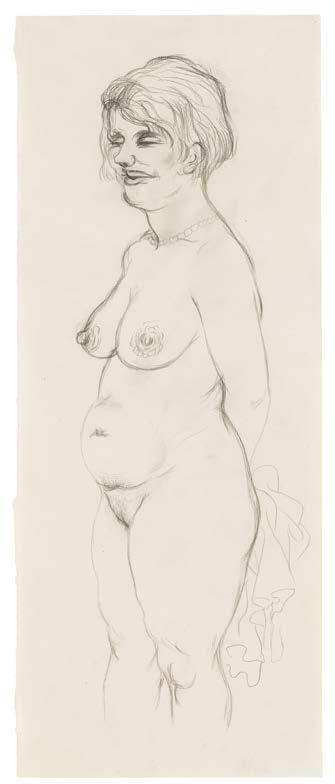

Following from there, we have a group of works that are hung with the tops of the frames touching. These portraits, which represent various interpretations of the female form, range in date from a beautiful eighteenth-century drawing by François Boucher to the most contemporary piece in the group, which is by Chris Ofili from 2005.

A particular love of mine and highlight of the collection are Pre-Raphaelite artists and those influenced by the brotherhood. Drawings from this group are well represented in this installation and include a Edward Burne-Jones and a Simeon Solomon as well as a piece by one of the only female artists associated with the PreRaphaelites, Mary Evelyn De Morgan, about whom I only recently learned.

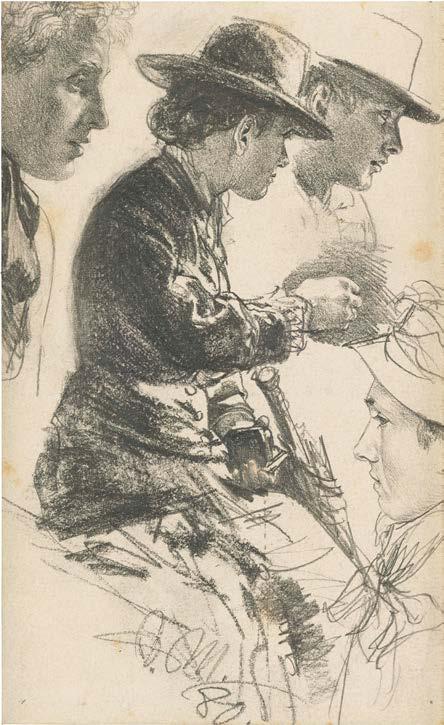

To the left of the De Morgan is an 1880s study of a seated lady with a hat by Adolf von Menzel. You can see how incredibly articulated it is on the one hand and at the same time, in the lower left, the marks become almost like an Abstract Expressionist drawing.

JS 437 Evelyn De Morgan, The Light Shineth in the Darkness and the Darkness Comprehended It Not, c. 1895

JS 437 Evelyn De Morgan, The Light Shineth in the Darkness and the Darkness Comprehended It Not, c. 1895

JS041 Pablo Picasso, La fille de la Marquise de Villarrautia (The Daughter of the Marquise de Villarrautia), 1918.

JS041 Pablo Picasso, La fille de la Marquise de Villarrautia (The Daughter of the Marquise de Villarrautia), 1918.

There is also a Roy Lichtenstein from 1963 that depicts a woman on the phone saying, “Oh Jeff…I love you too…but....” It’s a beautiful example of an early Lichtenstein, and it’s a great, great drawing. I had the honor of knowing him personally, which makes it even more special.

Last year, when I hung the exhibition Drawn: From the Collection of Jack Shear at the Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas, I also included a portrait by Picasso from 1918 in the female group, which will be included in Take Three of Ways of Seeing in Jarrett Earnest’s installation. The drawing was made about ten years after Picasso developed Cubism with Braque. With this piece, Picasso reminds us that he can draw in a formal, essentially academic way, almost as if he were referencing Ingres when he made it (he probably was).

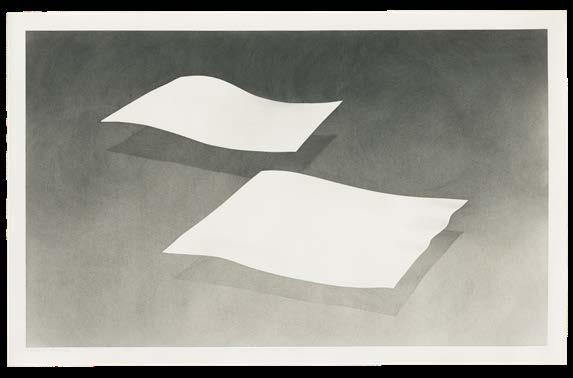

Next, we have a group of drawings by Blinky Palermo, Vija Celmins, Lee Lozano, Lee Bontecou, Stella Snead, Sean Ryan, and Ed Ruscha. The Ruscha is called Two Sheets with Whisky Stains. It’s a perfect drawing for a works on paper collector: two sheets of blank white paper on a sheet of paper.

JS052 Ed Ruscha, Two Sheets with Whisky Stains, 1973

JS052 Ed Ruscha, Two Sheets with Whisky Stains, 1973

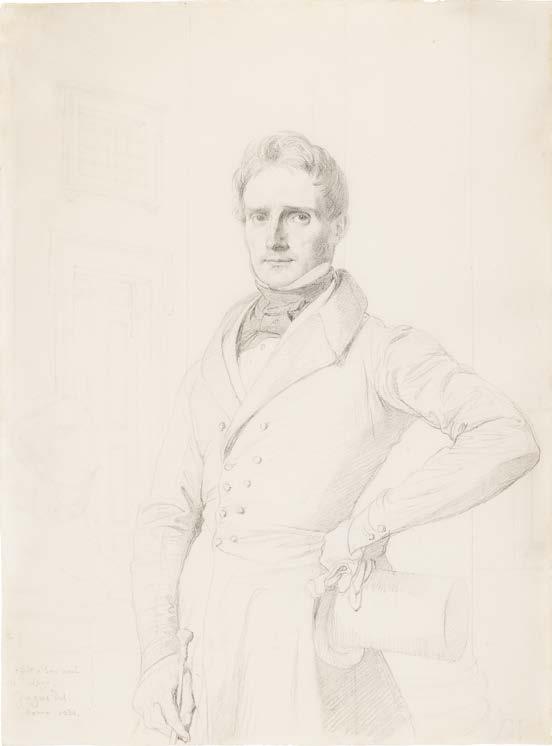

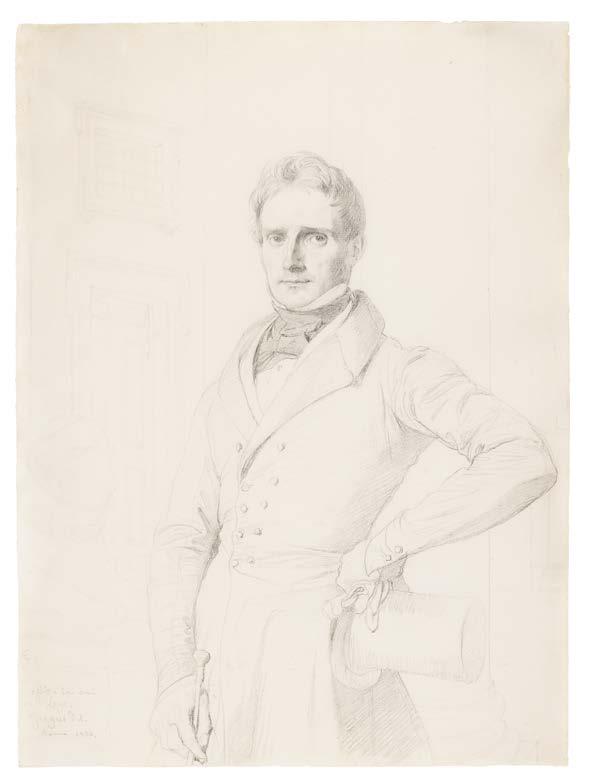

Now let’s move to a wall that features depictions of the male form. These drawings appear installed as if they were sitting on a shelf with the frames aligned at the bottom instead of the top. Perhaps the most famous drawing on this wall, or the one that most people respond to, is the portrait of Alexis-René Le Go by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres from 1836. Le Go served as Ingres’s secretary when he was director of the French Academy in Rome. The portrait depicts Le Go in front of the loggia at the Villa Medici in Rome, which remains home to the French Academy to this day. When I hung this series at the Blanton Museum, I also included a Marsden Hartley Self-Portrait from 1908 in which he looks really pained (his work is in the back room at The Drawing Center). He never thought he was attractive, and he hated self-portrait drawings, but this one is close to my heart. Next to the Hartley is this beautiful Giovanni Battista Piazzetta from around 1715. Piazzetta was one of the first Italian artists who made drawings that were intended to sell. He understood that drawings have as much emotional impact as paintings.

JS075 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836.

JS075 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836.

JS145 Marsden Hartley, Self-portrait #11, c. 1908

JS145 Marsden Hartley, Self-portrait #11, c. 1908

JS021 Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, A nude youth sprawled on his back, upon a bank, lying on a standard..., c. 1720

JS021 Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, A nude youth sprawled on his back, upon a bank, lying on a standard..., c. 1720

In the second gallery, I created a wall of predominantly blackand-white abstraction, which includes pieces by Richard Tinkler Hermann Nitsch, Barnett Newman, Minoru Onoda, Joe Yetto, Gerhard Richter, Donald Judd, and David Smith. To give the illusion that the group could go on forever, I installed the works all the way to the corner edges of the wall. Here, as throughout, the installations aim to create a stimulating and often unexpected dialogue between disparate works—across geography, subject matter, and time. As Picasso said, “I do not seek, I find.”

I’ve always collected. Even as a child, growing up in California, I had rock collections and bottle collections and a doorknob collection. I bought my first daguerreotype when I was 15 or 16 from a little shop that had twenty or so for sale. They were five dollars each, so I decided to buy five. The owner was dumbfounded: who is this teenager spending his money on daguerreotypes? I think he was pleased though, because he charged me twenty dollars for the five, giving me one for free. Daguerreotypes are printed on silver and often presented in small cases that have gold frames with glass inside. The cases themselves can be beautiful, and it is magical when you open them to reveal the image on silver. I went back to that same shop a couple of months later to buy the rest of the daguerreotypes, but they had all been sold. The owner told me that an old lady bought

the rest of them, threw out the daguerreotypes, and put pictures of her cats and dogs in the frames.

That experience started me on the path to collecting the way that you tend to think about collecting historically—in the same voracious way others have put together great collections, whether it’s drawings, paintings, sculpture, furniture, design, books, or anything else. There’s a hunger for acquiring that most people don’t have, or don’t want to have—collectors are often insatiable.

Ultimately, it’s really about the pleasure of seeing, the pleasure of looking.

Works in the Exhibition

David Hockney

Man Drawing, 1965

Black ink on paper

10 x 12 1/2 inches (25.4 x 31.8 cm)

Christo

Packed Public Building (Project for Allied Chemical Tower, No. 1 Times Square in NYC), 1968

Graphite, wax crayon, charcoal, brush, and gray wash on paper

28 x 22 inches (71.1 x 55.9 cm)

Robert Bechtle

RB on De Haro Street, 2004

Charcoal on paper

12 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches (31.8 x 31.8 cm)

Susan Rothenberg

Untitled, 1979

Acrylic, vinyl paint, color pencil, and graphite on paper

23 x 19 inches (58.4 x 48.3 cm)

Richard Tuttle

No. 83 Two Black Lines, Three Grey Dots, 1973

Ink and watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 6 inches (22.2 x 15.2 cm)

Alexander Calder

Three in the Middle, 1931

Black ink and transparent watercolor on paper

30 1/2 x 22 5/8 inches (77.5 x 57.5 cm)

Larry Poons

Untitled, c. 1961

Pencil on graph paper

8 1/4 x 11 inches (21 x 28 cm)

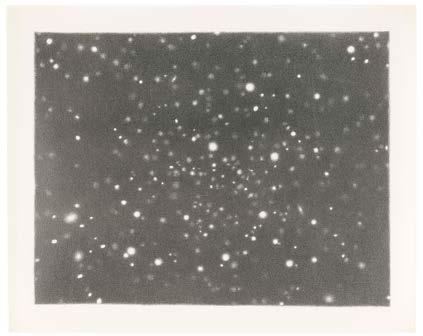

Fred Tomaselli

Ursa Major (May 12, 1991), 1991

Opaque watercolor and white chalk on paper

8 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches (21 x 28.6 cm)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Roger Freeing Angelica, c. 1830s

Pencil on tracing paper, squared in pencil

18 7/8 x 15 inches (47.7 x 38.2 cm)

Sigmar Polke

Ohne Title (Umarmung), [Untitled (Embrace)], 1963

Ballpoint pen on paper

11 5/8 x 8 1/4 inches (29.5 x 21 cm)

Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri)

Angelica and Medoro, c. 1640

Brown ink on paper

10 x 11 1/2 inches (25.4 x 29.2 cm)

Carlo Maria Mariani

Eliadi, 1981

Pencil on paper

19 x 14 inches (48.3 x 35.6 cm)

Léon Spilliaert

L’élévation, 1910

Pencil, ink wash, and brush on paper

11 15/16 x 7 11/16 inches (30.3 x 19.5 cm)

Bernard Boutet de Monvel

Erotic Scene, 1940

Pencil on paper

21 5/16 x 18 7/16 inches (54.2 x 46.8 cm)

Tom Knechtel

Working Drawing #1 for “Servant of Two

Masters”, c. 1993

Graphite on paper

16 1/2 x 13 3/4 inches (41.9 x 34.9 cm)

Raymond Pettibon

No Title (Whatever death means), 1990 Brown ink and transparent watercolor on paper

17 3/4 x 13 1/2 inches (45.1 x 34.3 cm)

Unknown (Indian School)

Sikh, n.d.

Pencil with gouache highlights on paper

6 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches (15.9 x 7.9 cm)

Walter Price

Scarecrow, 2020

Graphite, gel pen, Scotch tape, burned paper, colored pencil, and Sharpie on manila tagboard paper

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836

Graphite on paper

11 7/8 x 8 3/4 inches (30.2 x 22.2 cm)

Tom of Finland (Touko Laaksonen)

Untitled, 1980

Graphite on paper

12 x 8 7/8 inches (30.5 x 22.5 cm)

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

A nude youth sprawled on his back, upon a bank, lying on a standard..., c. 1720 Black and white chalk on paper

20 x 15 inches (50.8 x 38.1 cm)

Robert Corless

Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1963

Pencil and collage on paper

11 x 9 inches (27.9 x 22.9 cm)

Elaine de Kooning

Portrait of Bill, 1950

Brown ink on paper

8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

Chris Ofili

Afromuses (Couple), 2005

Watercolor and pencil on paper, one of a pair on facing walls

19 x 12 1/2 inches (48.3 x 31.8 cm)

Henri Matisse

Marocain, mi corps (Moroccan, Bust Length), 1912–13

Graphite on paper

10 x 7 1/2 inches (25.4 x 19.1 cm)

R. Crumb

R. CRUMB by R. CRUMB, 2020

Pen, ink, and white paint on paper

11 3/4 x 8 7/8 inches (29.8 x 22.5 cm)

Paul Thek

Self-Portrait, c. 1969

Graphite on paper

10 5/8 x 7 3/4 inches (27 x 19.7 cm)

Otto Greiner

Back View of a Standing Male Nude, 1896 Black and red chalk and opaque watercolor on paper

18 1/8 x 11 3/8 inches (46 x 28.9 cm)

Blinky Palermo

Komposition weiss-weiss (Composition White-White), 1966

Graphite and tape on paper

11 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches (29.8 x 21 cm)

Lee Lozano

No Title, 1964

Graphite on paper

12 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches (32.4 x 21.6 cm)

Vija Celmins

Galaxy (Hydra), 1974

Graphite on acrylic ground on paper

12 x 14 7/8 inches (30.5 x 37.8 cm)

Lee Bontecou

Untitled, 1968

Soot, graphite, opaque watercolor, and white chalk on paper

28 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches (72.4 x 57.2 cm)

Stella Snead

Untitled, c. 1940s

Ink on paper

11 x 13 3/4 inches (27.9 x 34.9 cm)

Sean Ryan

Untitled, 2020-21

Silverpoint on paper

11 x 15 inches (27.9 x 38.1 cm)

Ed Ruscha

Two Sheets with Whisky Stains, 1973

Gunpowder and Scotch whisky on paper

14 9/16 x 22 13/16 inches (37 x 57.9 cm)

Bruce Conner

UNTITLED: JUNE 4, 1965, 83 FRANCIS ST., BROOKLINE, MA, 1965, 1999

Black ink on paper

19 7/8 x 9 1/4 inches (50.5 x 23.5 cm)

Robert Delaunay

La Tour Eiffel (The Eiffel Tower), 1911

Brown ink and graphite on paper

18 1/4 x 15 1/4 inches (46.4 x 38.7 cm)

Anne-Louis

Girodet de Roussy-Trioson

Héro et Léandre, c. 1800

Pen, brush, brown ink, ink wash, and white gouache on blue paper

8 5/8 x 7 1/8 inches (21.9 x 18.1 cm)

Georges Seurat

An Evening, Gravelines, 1890

Conté crayon on paper

9 3/8 x 12 3/8 inches (23.8 x 31.4 cm)

François André Vincent

Arria and Paetus, c. 1784

Brown and black ink, black and red chalk on paper

16 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches (41.3 x 50.2 cm)

Fernand Legér

Etude pour “La Gare” (Study for “The Train Station”), 1918

Graphite on paper

9 1/2 x 13 5/8 inches (24.1 x 34.6 cm)

Georges Braque

La Guitare (The Guitar), 1919

Charcoal, pencil, and crayon on paper

10 5/8 x 8 inches (27 x 20.3 cm)

Eugene Delacroix

St. Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women, 1852–54

Pastel on paper

7 1/8 x 10 3/8 inches (18.1 x 26.4 cm)

Théodore Rousseau

Landscape in the Auvergne, c. 1830

Graphite and opaque watercolor on paper

11 1/2 x 8 3/4 inches (29.2 x 22.2 cm)

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

The Forum with the Temple of Venus in Rome, 1825

Graphite on paper

6 3/4 x 13 5/8 inches (17.1 x 34.6 cm)

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

Study for Doux Pays, 19th Century Black crayon and watercolor on paper

7 3/4 x 12 1/8 inches (19.7 x 30.8 cm)

Jacques Quesnel

Time Fighting Youth, c. 1588

Pen and brown ink

19 1/4 x 15 1/4 inches (48.9 x 38.7 cm)

Walter Sickert

Portrait of Carolina in A Shawl, c. 1904

Charcoal with white chalk on gray paper

16 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches (41.9 x 24.8 cm)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Reclining Female Nude, c. 1915

Graphite on paper

12 3/16 x 18 9/16 inches (31 x 47.1 cm)

Jim Nutt

Untitled, 2005

Graphite on paper

15 x 14 inches (38.1 x 35.6 cm)

John D. Graham

Head of a Young Woman, 1944

Silverpoint and graphite on paper

9 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches (24.1 x 24.1 cm)

Chris Ofili

Afromuses (Couple), 2005

Watercolor and graphite on paper, one of a pair on facing walls

19 x 12 1/4 inches (48.3 x 31.1 cm)

Adolph Friedrich

Erdmann von Menzel

Studie einer sitzenden Dame mit Hut, Schirm und Geldbörse (Study of a Seated Woman with a Hat, Umbrella and Coin Purse), 1880

Graphite on paper

8 x 5 inches (20.3 x 12.7 cm)

Evelyn De Morgan

The Light Shineth in the Darkness and the Darkness Comprehended It Not, c. 1895 Black and gold chalk with graphite on paper

25 x 17 1/2 inches (63.5 x 44.5 cm)

François Boucher

Head of a Young Woman, c. 1754

Black and white chalk on paper

13 7/8 x 9 7/8 inches (35.2 x 25.1 cm)

Roy Lichtenstein

Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But...(Study), 1964

Colored pencil and graphite on paper

5 3/4 x 5 5/8 inches (14.6 x 14.3 cm)

Oskar Kokoschka

Reclining Female Nude, c. 1911–12

Charcoal and crayon on paper

12 1/2 x 16 11/16 inches (31.8 x 42.4 cm)

Edward Coley Burne-Jones

S. Mary Magdalene the Morning of the Resurrection, 1886

Graphite on paper

12 x 7 inches (30.5 x 17.8 cm)

Simeon Solomon

Queen Esther Hearing the News of the Intended Massacre of the Jews, 1860

Pen and ink with some lead white on paper main sheet with three narrow additions laid to board

11 1/4 x 13 3/4 inches (28.6 x 34.9 cm)

Jean Arp

Untitled, 1918–20

Collage and paint on paper

13 3/4 x 13 inches (34.9 x 33 cm)

Joan Miró

Métamorphoses (Metamorphosis), 1936

Black ink, watercolor, charcoal, collage, and decal on paper

18 7/8 x 25 1/4 inches (47.9 x 64.1 cm)

Anne Ryan

M1044D#183, c. 1950

Collage on cardboard

7 1/2 x 6 inches (19.1 x 15.2 cm)

James Rosenquist

Study for Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Collage, color pencil, and graphite on paper

11 1/4 x 13 1/16 inches (28.6 x 33.2 cm)

Kurt Schwitters

für Herrn Dr. Bode (For the Gentleman Dr. Bode), 1924

Collage on artist mount

13 9/16 x 10 7/8 inches (34.4 x 27.6 cm)

Joe Brainard

Infant of Prague with Flowers, 1966

Gouache and collage on paper

14 x 11 inches (35.6 x 27.9 cm)

Terry Winters

Untitled, 2018

Graphite on paper

8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

Unknown (Indian School)

Tantric Drawing, c. 2000

Gouache and/or pigment and ink on paper

11 1/4 x 5 1/2 inches (28.6 x 14 cm)

Kalu Ram

Chart of 56 Shaligrams, n.d. Ink and gouache on paper with collage

28 x 21 inches (71.1 x 53.3 cm)

Jasper Johns

Untitled, 2015 Black ink on plastic

30 x 27 inches (76.2 x 68.6 cm)

Sol LeWitt

Red Grid, Yellow Circles, Black Arcs from Four Sides and Blue Arcs from Four Corners, 1972

Ink and graphite on paper

17 x 17 inches (43.2 x 43.2 cm)

Agnes Martin

Untitled, c. 1975

Transparent watercolor, black ink, and graphite on paper

9 x 9 inches (22.9 x 22.9 cm)

Brice Marden

Untitled, 1971

Graphite on paper

28 7/8 x 20 3/4 inches (73.3 x 52.7 cm)

Aaron Morse

Wilderness, 2000

Watercolor on paper

15 1/2 x 21 3/4 inches (39.4 x 55.2 cm)

Rashid Johnson

Untitled Anxious Red Drawing, 2020

Oil on cotton rag

30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Cy Twombly

Untitled, 1959–63

Pencil, ink, and crayon on paper

19 3/4 x 27 1/2 inches (50.2 x 69.9 cm)

Julie Mehretu

Untitled, 2000

Ink and colored pencil on vellum laid on paper

19 x 24 inches (48.3 x 61 cm)

Charles Demuth

Fruit and Flower, c. 1925

Opaque and transparent watercolor and graphite on paper

12 x 18 inches (30.5 x 45.7 cm)

Andy Warhol

Skull, c. 1976

Graphite on paper

20 1/2 x 28 inches (52.1 x 71.1 cm)

Pablo Picasso

Étude pour “Déjeuner sur l’herbe” II

(Study for “Luncheon on the Grass” II), 1962

Graphite on paper

10 5/8 x 13 7/8 inches (27 x 35.2 cm)

Bruce Nauman

A Rose Has No Teeth / Lead or bronze

plaque to be attached / to a tree in the woods so that it will / be grown over, 1966

Graphite on paper

18 7/8 x 24 inches (47.9 x 61 cm)

Claes Oldenburg

Drainpipe Study, 1967

Opaque and transparent watercolor and crayon on paper

30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

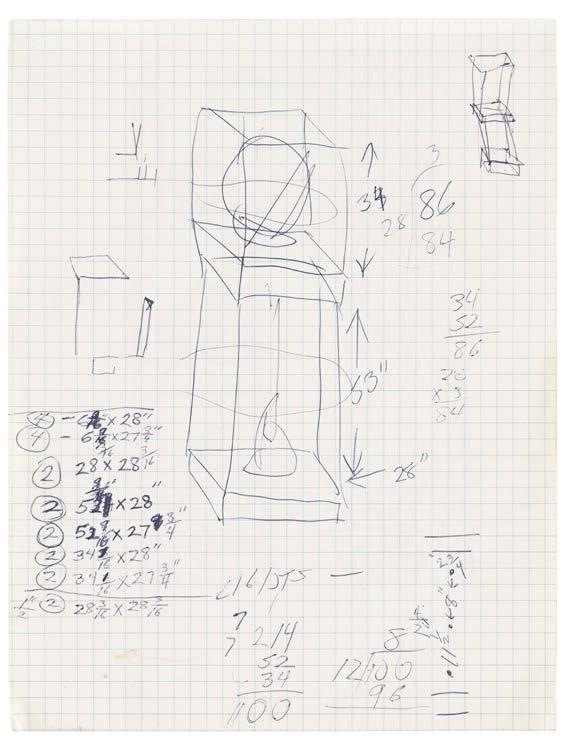

Robert Morris

Study for 4” Interlocking Brass Rings, 1968

Opaque and transparent watercolor and graphite on graph paper

25 3/4 x 30 1/2 inches (65.4 x 77.5 cm)

Pavel Tchelitchew

Portrait of Charles Henry Ford, c. 1940 Brown and blue ink on paper

11 3/4 x 7 7/8 inches (29.8 x 20 cm)

Mark Tobey

Lights, 1954

Tempera on Japan mounted on card

8 1/2 x 17 3/4 inches (21.6 x 45.1 cm)

Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri)

Lucretia, c. 1638

Pen and brown ink

5 11/16 x 4 13/16 inches (14.4 x 12.2 cm)

Odilon Redon

La Terrible (The Terrible One), c. 1871

Charcoal and black chalk on paper

16 3/4 x 13 1/4 inches (42.5 x 33.7 cm)

Alice Neel

Requiem, 1928

Watercolor on paper

9 x 12 inches (22.9 x 30.5 cm)

Edvard Munch

Blødende hjerte (Bleeding Heart), c. 1898

Crayon and opaque and transparent

watercolor on paper

9 7/8 x 14 1/8 inches (25.1 x 35.9 cm)

Günter Brus

Die rote Tödin, 1981

Pastel and graphite on packing paper

47 7/8 x 31 1/2 inches (121.6 x 80 cm)

Ellsworth Kelly

Blue Cut Out, 1962

Gouache on paper on paper cutout

12 1/8 x 9 inches (30.8 x 22.9 cm)

Joaquín Torres-García

Composición (Composition), 1930

Black ink and graphite on paper

5 1/4 x 3 1/2 inches (13.3 x 8.9 cm)

Albert Oehlen

Untitled, 2009

Black ink, graphite, plastic, and collage on paper

11 3/4 x 10 3/4 inches (29.8 x 27.3 cm)

Fred Sandback

Untitled 3/11/74, 1974

Pastel on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.4 x 73.7 cm)

Dorothy Dehner

Family Group 1, 1954

Ink on paper

23 1/4 x 35 inches (59 x 88.9 cm)

Barry Le Va

Untitled (Animated Perspective), 1981–82

Black ink, acrylic, and graphite on paper

22 1/4 x 13 inches (56.5 x 33 cm)

Torkwase Dyson

Sing, 2020

Gouache and ink on paper

16 x 12 inches (40.6 x 30.5 cm)

Joel Shapiro

Untitled, 1978

Charcoal on paper

18 x 18 inches (45.7 x 45.7 cm)

Willem de Kooning

Figure on a Beach, 1958

Black ink on paper

17 x 14 inches (43.2 x 35.6 cm)

Richard Serra

C.C. XI, 1983–84

Oilstick on paper

38 x 52 inches (96.5 x 132.1 cm)

Terry Winters

Untitled, 2011

Graphite on paper

19 7/8 x 25 1/2 inches (50.5 x 64.8 cm)

Richard Tinkler

Book 5, Vol. 1, Page 7 - (1,2,1,2,1,2), 2020

Color ink on paper

23 1/4 x 17 3/4 inches (59.1 x 45.1 cm)

Hermman Nitsch

Untitled, 1973

Black ink and graphite on paper

11 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches (29.8 x 21 cm)

Barnett Newman

Untitled, 1960

Black ink on paper

14 x 10 inches (35.6 x 25.4 cm)

Minoru Onoda

Untitled, 1962

Ink on paper

13 3/4 x 10 5/8 inches (34.9 x 27 cm)

Joe Yetto

Untitled, 2010

Charcoal on paper

29 1/2 x 41 1/2 inches (74.9 x 105.4 cm)

Gerhard Richter

Abstract VII 91, 1991

Ink on paper

9 1/4 x 13 inches (23.5 x 33 cm)

© Gerhard Richter 2021

Donald Judd

Plywood Angled Boxes, #280, 1976

Graphite on paper

22 3/4 x 31 inches (57.8 x 78.7 cm)

David Smith

Untitled, 1955

Egg ink and tempera on paper

17 3/4 x 22 1/2 inches (45.1 x 57.2 cm)

Gordon Matta-Clark

Untitled (Arrows), 1973–74

Graphite on paper

17 1/2 x 23 1/2 inches (44.5 x 59.7 cm)

Andy Warhol

Mao, 1973

Graphite on paper

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm)

Marsden Hartley

Self-portrait #11, c. 1908

Black crayon on paper

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Philip Guston

Head and Smoke, 1974

Black ink on paper

18 7/8 x 23 5/8 inches (47.9 x 60 cm)

Patrick Lee

Deadly Friends (Bubba), 2009

Graphite on paper

36 x 24 inches (91.4 x 61 cm)

Jasper Johns

Handprint, 1964

Oil on paper

20 5/16 x 17 1/4 inches (51.6 x 43.8 cm)

Robert Rauschenberg

Untitled, 1965

Solvent transfer, graphite, crayon, watercolor, and paint on paper

14 1/8 x 20 inches (35.9 x 50.8 cm)

Vija Celmins

Untitled (Ocean), 2014

Charcoal on acrylic ground on paper

15 1/4 x 18 1/2 inches (39 x 47 cm)

Nancy Grossman

Sketch #1 for Bound, 1975

Lithographic crayon and wash on coated paper

29 x 19 1/2 inches (73.7 x 49.5 cm)

Nancy Spero

The Bomb, 1966

Gouache and ink on paper

16 1/2 × 22 inches (41.9 × 55.9 cm)

George Grosz

Stammgäste (Regular Guests), 1915

Black ink on paper

12 5/8 x 8 1/16 inches (32.1 x 20.5 cm)

Max Beckmann

Entkleidetes Café, 1944

Ink and india ink on paper

10 5/8 x 14 1/2 inches (27 x 36.8 cm)

Julian Schnabel

Untitled (Automatic 6:30-8:30, 4.9. E - 68), c. 1980

Blue ink and graphite on paper

16 x 13 inches (40.6 x 33 cm)

Francis Picabia

Transparence (Transparency), c. 1930–33

Pencil, color pencil, and ink on paper

14 1/4 x 12 1/4 inches (36.2 x 31.1 cm)

Georg Baselitz

Der neue Typ (The New Type), 1966–67 Charcoal, watercolor, and graphite on paper

24 x 17 inches (61 x 43.2 cm)

Jan Toorop

Meditatie (Meditation), 1921 Black crayon on paper

11 3/8 x 9 inches (28.9 x 22.9 cm)

Fernand Khnopff

Study for The Blood of Medusa, 1898 Graphite, crayon, and collage on wove paper

8 3/8 x 6 3/8 inches (21.3 x 16.2 cm)

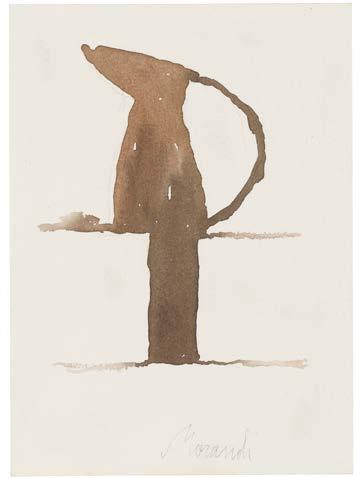

Giorgio Morandi

Natura Morta (Still Life), 1959

Watercolor on paper

9 1/4 x 6 3/4 inches (23.5 x 17.1 cm)

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas

A Study of a Young Boy with his Arms Raised about his Head, Preparatory for ‘Young Spartans Excercising’, c. 1860 Graphite on paper

14 x 8 3/4 inches (35.6 x 22.2 cm)

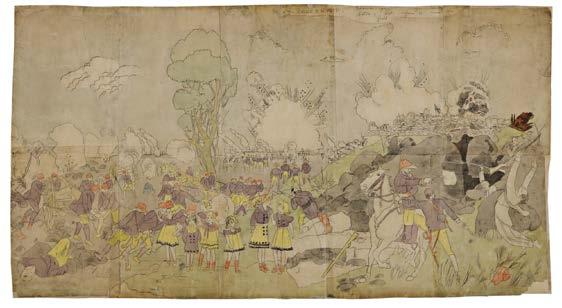

Hashimoto Sadahide (Utagawa Sadahide)

The Opposing Forces Ford a River Towards Troop in Formation on Bank (Preparatory drawing for a triptych of a battle scene), c. 1847–48

Black ink on paper

15 x 19 1/2 inches (38.1 x 49.5 cm)

Kim Jones

Untitled, 1996 Pencil on paper

25 x 38 inches (63.5 x 96.5 cm)

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

The miraculous draught of Ruggiero and Alcina (Orlando furioso, VII, 32), c. 1780–85

Black chalk with opaque and transparent watercolor on paper

15 7/8 x 10 1/4 inches (40.3 x 26 cm)

André Masson

Sémiramis et le Minotaure (Semiramis and the Minotaur), 1940 Black ink on paper

18 3/4 x 24 5/8 inches (47.6 x 62.5 cm)

Kota School, North India, Rajasthan Tiger Hunt with Elephants, late 19th Century Black ink, opaque and transparent watercolor, and red chalk on paper

20 1/2 x 18 7/8 inches (52.1 x 47.9 cm)

Arlene Shechet

Arlene Shechet

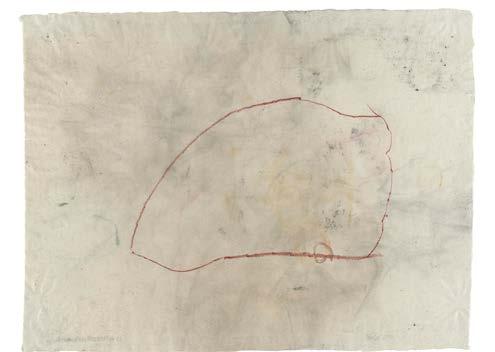

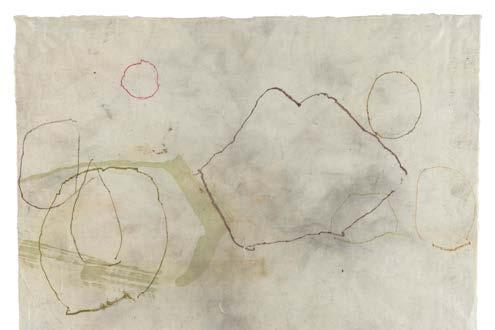

Drawings present unmediated evidence of the artist’s hand and mind. They stem from an intimate practice whose tools and materials are limited. They are essentially records of the body: of being alive. As surfaces that bear the rawest marks of one’s hand, drawings are by nature intimate objects that remind us of the important of touch. Since I conceived this show at the height of a pandemic that necessitated isolation from others, this issue of touch had double weight for me. I knew the drawings alone could stimulate an awareness of one’s body. But as a sculptor, I also knew the importance of space in shaping a viewing experience. How and where one stands in relation to an artwork is integral to how that artwork inherits meaning: how it is seen. Pulling out the drawings’ greatest potential meant connecting them to something outside of their own contours while allowing each one to independently hold its own. I wanted to play with the traditional viewing height and distance that one experiences in a gallery and have the room accommodate various body positions, inviting people to linger, have conversations, and possibly even sit together after months of being apart.

In contrast to the intimacy of the drawings, the space of The Drawing Center has a large central volume that can feel cavernous. As a sculptor, I was sensitive to this. Creating horizontal lines to fill the space and reach out to the walls would knit the room together. What could those lines be? Low-lying sculptures that would not interfere with viewing the drawings but would enhance the pleasure of experiencing the art. This connective tissue would eventually take the form of a quartet of hand-carved benches made from single logs of white oak. The massive nature of those bestial logs anchored and grounded the space and also provided a canvas

for me to carve my own lines that played off those of the works in Jack Shear’s collection. These horizontal structures also spoke to the fluted columns (the architectural equivalent of trees) in the main gallery of The Drawing Center. From a functional point of view, and given that the show opened as winter descended on New York, the benches gave people a place to gather and spend time with the work and with each other. [FIG. X]

In planning the show, I realized I needed to paint as well as carve. Seeing a show of Giorgio Morandi’s paintings at David Zwirner gallery made me conscious of space in a new way: all the forms are compacted, enclosed, grounded. He eliminated the space between the vessels and created a divided ground for them to live in. I wanted to carry this sensation to The Drawing Center, creating a space that would hold you close while looking and make you completely aware of your own presence [FIG X].

FIG JS275 Giorgio Morandi, Natura Morta, 1959.

FIG JS275 Giorgio Morandi, Natura Morta, 1959.

I took note of Morandi’s use of the horizon line to divide his compositions. Inspired, I decided to hand paint the lower register of the walls, dividing them into two unequal areas using lightly modulated earth tones, in order to create a palette and texture that could hold and unite the disparate elements of the show. I wanted to create a kind of architectural landscape on the walls within which I could play with the hanging of the artworks. The paint was brushed on by hand so that the color was not opaque or uniform, conveying the feeling of human touch. Morandi’s touch is so potent, and this same impression was reflected on the walls with brighter patches where the paint is thinner and the white wall shows through—the uneven work of the hand lending an overall dynamism.

Drawings reveal the imperfection of being human, complete with a wobbly hand that exerts irregular pressure across a surface. In a few drawing selections and placements, I pulled this unevenness out explicitly. The Jim Nutt Oh Look! and Look at this! drawings (1975), for instance, accentuate the painted line’s wonkiness as the crooked edge of the pages seem to extend directly into and onto the wall [FIGS X, X]. Throughout the show, I wanted to initiate a back-and-forth between looking closely at the interior of a drawing and then zooming out, seeing its relationship to the overall design of the room. In a room of such size, orchestrating this balance between different ways of looking and moving through the space was the challenge. Ideally, the drawings and architecture would create a constellation, where all the elements subliminally fire away, leading your eye and body through the space.

A curator may say I approached this whole project backwards, working first with the space and second with the objects in the space. But I see it more as a dance than a hierarchy or a fixed order of procedures. I follow this kind of improvisational logic in the studio and all other public spaces in which I’ve curated or created artwork. I am always guided by the materials at hand rather than some predetermined will I have for them—and as a sculptor, my materials necessarily involve the work’s final environment, not only the stuff in my studio. In this way, I saw myself in service to both the drawings and the specificity of The Drawing Center as a site for hanging them, knowing I wanted to create a completely integrated experience of them both. If I was successful, the drawings would stand as autonomous artworks and at the same time create a rhythm throughout the room, inviting a new way of moving and seeing for everyone who encountered them.

FIG X, X JS340, 341

Top: Jim Nutt, Oh Look!, 1975 / Bottom: Jim Nutt, Look at this!, 1975

FIG X, X JS340, 341

Top: Jim Nutt, Oh Look!, 1975 / Bottom: Jim Nutt, Look at this!, 1975

The hanging process was necessarily action-oriented, since it all happened in two days. I intentionally came with more drawings than would fit, and I began spacing them out by hanging one piece on one wall and letting that dictate what came next. I quickly discovered that the process of hanging these drawings was the same process as making art and specifically the same as making my sculptures. It’s a 360-degree mentality, based on circulating around the object as it comes into being, dealing with all angles at once. It’s the opposite of linear thinking: working from the center outward. This happens not only when producing a single sculpture, but also when working on six or seven sculptures at a time, making moves on each piece, which over time develops a language across the whole group. The relationships unfold in real time. On some level I already knew this, but the experience of diving in at The Drawing Center—taking a leap of faith in the materials’ capacity to create new meaning—confirmed this. As the only artist in the triad of curators, I found myself using the same techniques and strategies I use every day in the studio.

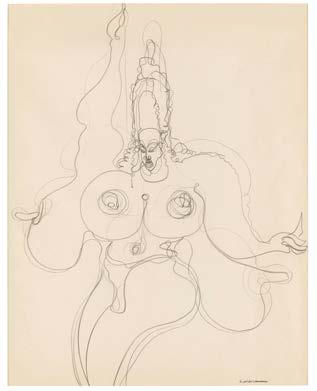

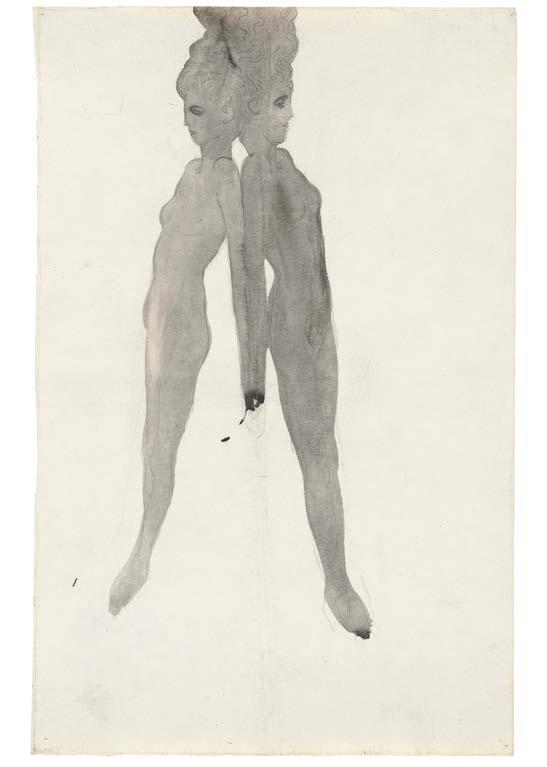

In this spirit, I placed Gaston Lachaise’s Dancing Female Nude with Headdress (n.d.) as the centerpiece of the back room, letting

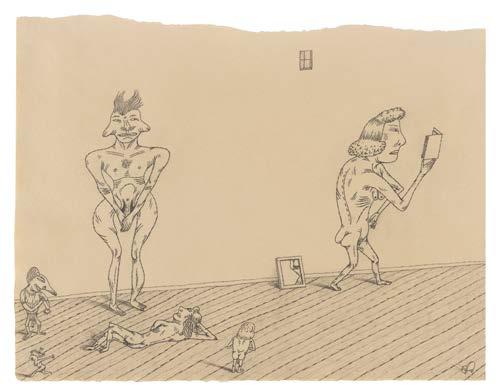

JS050 George Grosz, Stehender Akt (Standing Nude), c. 1927–28.

JS050 George Grosz, Stehender Akt (Standing Nude), c. 1927–28.

JS075 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836.

JS075 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836.

it dictate what followed around it [FIG X]. The figure’s breasts read to me like eyes, and from this unfolded the concept of a portrait gallery of sorts. While I did not generally select drawings based on their subject matter, in this room I instinctually developed a hanging strategy based loosely around this idea. All the drawings are hung so that the sitter’s eyes are at the same height. An imaginary line is thus drawn by their gaze—all except one, the fantastic Stehender Akt (Standing Nude, 1927–28) by George Grosz [FIG X] at the center, flanked on either side by “proper” men—Ingres’s contrite Portrait of AlexisRené Le Go (1836) [FIG X] and Raphael Soyer’s intent Self Portrait and My Father (n.d.) [FIG X]. The portraits are bookmarked on either side

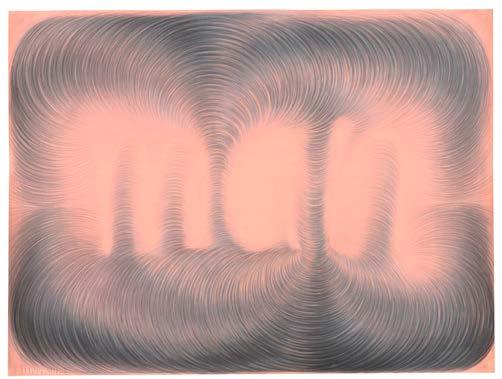

JS533 Kinke Kooi, Man, 2001

JS534 Kinke Kooi, Woman, 2001

by reclining nudes and the incredible pencil drawings by Kinke Kooi that read “Woman” and “Man” [FIG X, X]. The symmetry created by this array of drawings was another way of organizing the space—and also a way to play with the idiosyncrasies of Jack’s collection. I loved discovering this range and a few outliers in what I thought I knew about an artist’s oeuvre.

This back room also posed a unique spatial problem. It is a narrow space, penetrated at its center by an uncomfortably bulky column. A problem is a great thing for an artist, though, usually prompting some idea that ends up defining the work. So I played into it, positioning the bench so that the obnoxious column literally “pushes” its center out, turning its formerly straight edge into a jagged one. This created a privileged viewing seat, a perch from which one could address the wall of sitters—specifically Lachaise’s “queen,” positioned directly in front of the makeshift throne. The

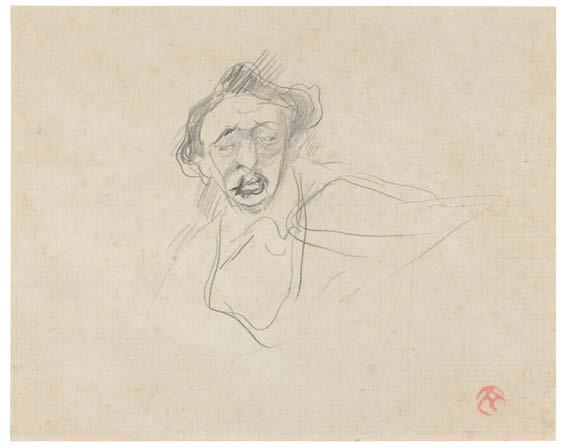

JS538 Léon Spilliaert, L’élévation (The Elevation), 1910

JS538 Léon Spilliaert, L’élévation (The Elevation), 1910

room is full of real personages and opens the notion of what a portrait can be.

Even though a hanging formula took shape in this back space, this is not how I approached the curatorial mandate in general. Like in the process of artmaking, I did not begin with rules, but instead let the drawings speak to me over the course of repeated viewings. It took six months before I even grasped the full breadth of the collection and another eighteen months of coming and going from the collection, pulling out connections between the works. It was a slow burn. Many of the connections were about gesture and mark, not “subject matter” per se. Ray Yoshida’s untitled graphic drawing of parting curtains [FIG XJS276] played off the amorphous strokes of Léon Spilliaert’s L’elevation, which looks like legs parting [FIG X, X]. Further down the wall, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’s drawing, St. Radegonde Taking the Veil, activates the same gesture but in

an explicitly religious context [FIG X]. And finally, Degas’s literal depiction of legs, Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (c. 1859–60) [Edgar Degas] placed on the register below, makes the gesture even more lucid but never pins it down as one thing—it is still always about the act of drawing. On the opposite wall, Delacroix leads to Darger, which leads to Jim Nutt—a string of artists covering a wide swath of art history and with seemingly oppositional focuses and intentions, yet who are connected by the act of drawing, the act of sitting down and making a mark. What connects Jim Nutt to Cy Twombly is not what they depict, but how they draw: that same nervous but sure hand. In making selections, I kept specific meaning from overriding the general attitude of what a drawing is and how the marks are made. [FIG X, X, X]

The benches further amplified my overall curatorial strategy. I conceived of them as both a place for sitting and a way to bind together the room. The connection is made through color but also through scale as the top register of the painted wall is the exact width of the benches. Of course, a viewer would not be specifically aware of this measurement but might subconsciously start to tie the planes together, essentially “flipping” the floor up to the wall and the wall down to the floor. The two registers complicate the notion of an “ideal” viewing height and a single horizon line. Standing upright, positioned close to the wall, the beige line meets the eye at a height of X inches. But sitting down and viewed from afar, the lower register is the one more related to the body, creating a second horizon line.

JS199 Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Left Hand, n.d.

JS199 Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Left Hand, n.d.

JS144 Eugene Delacroix, St. Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women, 1852–54.

JS066 Henry Darger, At Cedernine. Vivian girls ... battle, but refuse to leave the field (recto) At Anna Miria. One of the Vivian girls Violet takes up afternoon sentry duty and frustrates a number of Glandelinian sharp shooters be her own swift and good accuracy of shooting (verso), c.1940–1960.

Nearly all the works hang low in the room, hugging this second, lower register—like a handrail supporting one’s body weight. I imagined the benches to be like logs or tree trunks that had fallen in the forest: nature’s most ingenious, ad hoc form of seating. As such, my carving intervention was actually quite minimal. I left the rawness of the wood intact, making sure that the brutish nature of the outdoors was not lost. I used a range of tools—some creating deep grooves, others shallow—so that every mark was distinct; yet the wood was not completely “tamed” by my hand. I conceived of its surface as yet another kind of drawing mark in the room. I also wanted all sides of the logs to be available for sitting, so I rounded the ends and created divots along the horizontal edges to suggest a seat. This did away with the front/back dichotomy of manufactured benches, allowing a person to reposition oneself along the log in any number of ways. [FIG X]

The benches were made from single, gargantuan trunks of white oak, which were dried for many months. This drying process is a bit like glazing in that there is a necessary surrender to the unknowns of chemistry and physics. While I can always predict how

the glazes might chemically react, I ultimately rescind control once the clay enters the kiln and is subjected to heat. In the case of white oak, which I have worked with for many years, I knew its general behavior of checking (expanding and cracking) during the drying process and had a premonition that long, straight lines would form as the wood expanded and contracted. But I could never know how this would play out exactly. I took joy in witnessing the wood making its own drawing as it cracked. Once I positioned the logs in the room, they created three bold, horizontal strokes, perpendicular to the columns, almost but not quite abutting them. Their straight fissures played off the more curvilinear contours in the floor’s finished planks, and of course the marks across each sheet of paper. Beyond the mark-making, I was drawn to the material synchrony of wood being the precursor to paper. While they are completely distinct in scale from what is on the walls, the logs created another kind of drawing—initiated by me but beyond my control.

I sensed a similar attitude of minimal intervention in the way Jack has approached his collection. Most of the drawings he has amassed have had past lives and previous owners who framed them and then lived with them. Regardless of condition, Jack has kept most of those frames intact, understanding their relationship to the drawing as a marriage—the drawing and frame: a single complete object. Toulouse-Lautrec’s Le Violiniste Dancla, for instance, with its nervous, sinewy line, feels intimately related to the peeling frame it sits in [FIG X]. This element was one of the great surprises I experienced while hanging, as my primary encounter with the drawings did not take their frames into account. During my visits to Jack’s collection, I took iPhone photos of the works, which I then printed and moved around like playing cards. The scale and condition of the frames were lost in this process, so it was only in the final stage of hanging that they became full objects to me again.

Likewise, I could not know until late in my own process how (or if) Jack’s installation would set the stage for mine. When I walked through his show, I experienced the drawings as autonomous objects—free from the conventional labels that would have placed each work in a certain time period or with a particular artist. Unhampered by art historical tradition, he gave himself permission to “DJ” the drawings according to some other visual logic. I embraced that attitude in my installation but made it more spatial. I felt compelled to deal equally with the architecture and the drawings so that all the elements—the walls, the floors, the columns, the drawings—would be experienced as an inevitable choreography, each

JS564 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Le Violiniste Dancla (The Violinist Dancla), n.d.

JS564 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Le Violiniste Dancla (The Violinist Dancla), n.d.

part inseparable from the next, much like the original frame is to the drawing it holds.

In the end, as Hilton Als suggests in his essay in the first volume of this publication, it’s all about love. Over and again, I fell in love with each piece I hung and so many others. Each of these artworks, one way or another, is about life with love, and the collection itself is now more alive than ever, having been seen and jostled by the three of us and swooned over by those who visited the shows at The Drawing Center or turned the pages of this book.

Works in the Exhibition

Giorgio Morandi

Natura Morta, 1959

Watercolor on paper

9 1/4 x 6 3/4 inches (23.5 x 17.1 cm)

Arthur G Dove

Wednesday Snow, 1933

Watercolor and charcoal on paper

7 x 5 inches (17.8 x 12.7 cm)

Richard Tuttle

No. 83 Two Black Lines, Three Grey Dots, 1973

Ink and watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 6 inches (22.2 x 15.2 cm)

Lee Bontecou

Untitled, 1968

Soot, graphite with opaque watercolor, and white chalk on paper

28 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches (72.4 x 57.2 cm)

Al Taylor

Untitled, 1990

Ink, color pencil, and white-out on paper

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Robert Gober

Untitled, 2017

Graphite and color pencil on vellum

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Christo

4 Store Fronts (Project for H1 and H2), 2000

Wax crayon, graphite, pastel, enamel paint, and charcoal on paper

8 x 8 inches (20.3 x 20.3 cm)

Frank Stella

Marquis de Portago, 1960

Graphite and aluminum paint on graph

paper

17 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches (44.5 x 57.2 cm)

© 2021 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Stanley Whitney

Untitled, 2020

Crayon and graphite on Japanese paper

12 1/2 x 17 inches (31.8 x 43.2 cm)

Kazimir Malevich

Suprematist Composition, c. 1915

Charcoal on paper

6 1/2 x 4 1/2 inches (16.5 x 11.4 cm)

Georges Braque

La Guitare (The Guitar), 1919

Charcoal, pencil, and crayon on paper

10 5/8 x 8 inches (27 x 20.3 cm)

Gustav Klimt

Female Nude Opening a Curtain: Further Study in The Left Margin, c. 1898

Graphite on lined paper

7 1/2 x 4 3/4 inches (19 x 12 cm)

Barnett Newman

Untitled, 1960

Black ink on paper

14 x 10 inches (35.6 x 25.4 cm)

Brice Marden

Card Drawings, (Counting) #6, 1982 Ink and silkscreen on card

6 x 5 7/8 inches (15.2 x 14.9 cm)

© 2021 Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fred Tomaselli

Ursa Major (May 12, 1991), 1991

Opaque watercolor and white chalk on paper

8 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches (21 x 28.6 cm)

Kazimir Malevich

Composition, 3k, 1915

Pencil on squared paper

4 3/8 x 6 3/8 inches (11.1 x 16.2 cm)

Gordon Matta-Clark

Untitled (Arrows), 1973–1974

Graphite on paper

17 1/2 x 23 1/2 inches (44.5 x 59.7 cm)

Mark Tobey Lights, 1954

Tempera on Japan mounted on card

8 1/2 x 17 3/4 inches (21.6 x 45.1 cm)

Brice Marden

Untitled, 1972–1973

Ink on paper

11 5/8 x 7 7/8 inches (29.5 x 20 cm)

© 2021 Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alexander Calder Three in the Middle, 1931

Black ink and transparent watercolor on paper

30 1/2 x 22 5/8 inches (77.5 x 57.5 cm)

Edvard Munch

Blødende hjerte (Bleeding Heart), c. 1898

Crayon and opaque and transparent

watercolor on paper

9 7/8 x 14 1/8 inches (25.1 x 35.9 cm)

Susan Rothenberg

Untitled, 1979

Acrylic, vinyl paint, color pencil, and graphite on paper

23 x 19 inches (58.4 x 48.3 cm)

Nancy Spero

The Bomb, 1966

Gouache and ink on paper

16 1/2 × 22 inches (41.9 × 55.9 cm)

Elizabeth Murray

Alliances, 1988

Black ink and color pencil on paper

10 1/2 x 8 1/8 inches (26.7 x 20.6 cm)

Barry Le Va

Parts to Sections/ in 3 different perspectives, 1981

Pencil on vellum with clear tape 14 x 11 inches (35.6 x 28 cm)

Richard Artschwager

Door Window Table Basket Mirror Rug #10, 1974

Graphite and ink on paper

22 3/4 x 31 1/4 inches (57.8 x 79.4 cm)

Unknown, (Indian School)

Tantric Drawing, n.d.

Gouache and/or pigment and ink on paper

9 1/2 x 8 3/4 inches (24.1 x 22.2 cm)

George Grosz

Sex Appeal, 1929

Graphite on paper

23 5/8 x 18 1/4 inches (60.1 x 46 cm)

Saul Steinberg

Untitled (Two Women Talking), c.1995

Ink on paper

11 x 13 3/4 inches (27.9 x 34.9 cm)

David Park

Two Figures, 1958

Double-sided ink on paper

10 7/8 x 8 1/2 inches (27.6 x 21.6 cm)

Ray Yoshida

Untitled, c. 1972

Felt-tipped color pen on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

Léon Spilliaert

L’élévation (The Elevation), 1910

Pencil, ink wash, and brush on paper

11 15/16 x 7 11/16 inches (30.3 x 19.5 cm)

Edgar Degas

Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale”

(Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”), c. 1859–1860

Graphite on laid paper

14 1/8 x 9 1/8 inches (35.9 x 23.2 cm)

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

St. Radegonde Taking the Veil, n.d.

Charcoal and stump on paper

26 1/4 x 18 5/8 inches (66.7 x 47.3 cm)

Joseph E. Yoakum

Soe River, Dadeville, Missouri, c. 1960–70

Transparent watercolor and ballpoint

pen on paper

8 x 10 inches (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

Edward Burne-Jones

S. Mary Magdalene the Morning of the Resurrection, 1886

Graphite on paper

12 x 7 inches (30.5 x 17.8 cm)

Valentine Cameron Prinsep

Study of a Young Girl, Late 19th Century

Pencil on paper

9 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches (24.8 x 21 cm)

Edward Burne Jones

A Head of a Knight from “The Briar Wood”, 1874

White and black chalk on buff paper laid down on canvas

12 5/8 x 13 inches (32 x 33cm)

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

Left Hand, n.d.

Graphite on Paper

4.5 x 8.25 inches (11.4 x 21 cm)

Simeon Solomon

The Annunciation, 1884

Pencil with stump on paper

14 7/8 x 21 7/8 inches (37.8 x 55.6 cm)

Bernard Boutet de Monvel

Untitled (Woman Looking to Her Right), c.1930

Graphite on paper

20 x 14 1/2 inches (50.8 x 36.8 cm)

Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel

Studie einer sitzenden Dame mit Hut, Schirm und Geldbörse (Study of a Seated Woman with a Hat, Umbrella and Coin Purse), 1880

Graphite on paper

8 x 5 inches (20.3 x 12.7 cm)

Jan Toorop

Meditatie (Meditation), 1921

Black crayon on paper

11 3/8 x 9 inches (28.9 x 22.9 cm)

Georges Seurat

Le griffon altéré (The Thirsty Griffon), 1875–1876

Pencil on paper mounted on board

8 1/16 x 9 9/16 inches (20.5 x 24.3 cm)

Leon Golub

Untitled (Head with Wavy Hair), 1963

Sanguine on vellum

23 1/2 X 18 1/2 inches (59.7 x 47 cm)

Jean Cocteau

The Souvenir, 1933

Ink and wash on paper

8 x 5 1/2 inches (20.3 x 14 cm)

Sigmar Polke

Untitled, 1968

Graphite on paper

8 1/2 x 5 3/4 inches (21.6 x 14.6 cm)

Fred Sandback

Untitled 3/11/74, 1974

Pastel on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.4 x 73.7 cm)

Utagawa Yoshitsuya

The Yotsuya Ghost Story / The Tale of the Hag of Adachi Moor, 1846–1848

Black and blue ink on rice paper with additions

14 3/4 x 21 11/16 inches (37.5 x 55.1 cm)

Bernard Boutet de Monvel

Erotic Scene, 1940

Pencil on paper

21 5/16 x 18 7/16 inches (54.2 x 46.8 cm)

George Grosz

Stammgäste (Regular Guests), 1915

Black ink on paper

12 5/8 x 8 1/16 inches (32.1 x 20.5 cm)

Odilon Redon

Colloque, c. 1880s

Graphite on paper

9 5/16 x 11 13/16 inches (23.6 x 29.9 cm)

Aristide Maillol

Daphne and Chloe Playing, n.d.

Pencil on paper tipped to a paper mount

5 3/8 x 3 1/2 inches (13.7 x 8.9 cm)

Max Beckmann

Entkleidetes Café, 1944

Ink and India ink on paper

10 5/8 x 14 1/2 inches (27 x 36.8 cm)

Eugene Delacroix

St. Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women, 1852–54

Pastel on paper

7 1/8 x 10 3/8 inches (18.1 x 26.4 cm)

Henry Darger

At Cedernine. Vivian girls ... battle, but refuse to leave the field (recto) At Anna Miria. One of the Vivian girls Violet takes up afternoon sentry duty and frustrates a number of Glandelinian sharp shooters be her own swift and good accuracy of shooting (verso), c.1940–1960

Watercolor, carbon tracing, and graphite on 3 joined sheets of paper

23 x 42 1/4 inches (58.4 x 107.3 cm)

Cy Twombly

Untitled, 1959–1963

Pencil, ink, and crayon on paper

19 3/4 x 27 1/2 inches (50.2 x 69.9 cm)

Jim Nutt Oh Look!, 1975

Graphite on paper

10 1/2 x 12 7/8 inches (26.7 x 32.7 cm)

Jim Nutt Look at this!, 1975

Graphite on paper

10 1/2 x 12 7/8 inches (26.7 x 32.7 cm)

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

Study for Doux Pays, 19th Century Black crayon and watercolor on paper

7 3/4 x 12 1/8 inches (19.7 x 30.8 cm)

Hans Bellmer

Untitled, c. 1955

Chinese ink wash and pencil on paper

11 3/4 x 10 5/8 inches (29.8 x 27 cm)

Auguste Rodin

Female Figure Squatting, Seen From the Front, c. 1900

Graphite on paper

11 5/8 x 7 5/8 inches (29.5 x 19.4 cm)

Ed Ruscha

Two Sheets with Whisky Stains, 1973

Gunpowder and Scotch whisky on paper

14 9/16 x 22 13/16 inches (37 x 57.9 cm)

Kurt Schwitters

Two Stones In Rhythm, 1947

Pencil on paper

7 7/8 x 5 1/4 inches (19.9 x 13.3 cm)

Robert Morris

Untitled (Magnetic Field), 1964

Graphite on paper

10 3/4 x 13 inches (27.3 x 33 cm)

Lee Lozano

No Title, 1964

Graphite on paper

12 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches (32.4 x 21.6 cm)

Salvador Dalí

Untitled, 1930s

Black ink and graphite on paper

10 x 6 1/2 inches (25.4 x 16.5 cm)

Larry Poons

Untitled, c. 1961

Pencil on graph paper

8 1/4 x 11 inches (21 x 28 cm)

Ellsworth Kelly

Blue Cut Out, 1962

Gouache on paper on paper cutout

12 1/8 x 9 inches (30.8 x 22.9 cm)

Robert Morris

Study for 4" Interlocking Brass Rings, 1968

Opaque and transparent watercolor and graphite on graph paper

25 3/4 x 30 1/2 inches (65.4 x 77.5 cm)

Agnes Martin

Untitled, c. 1960s

Ink and graphite on paper

8 1/16 x 8 15/16 inches

Agnes Martin

The Great Rose of Evening, 1962

Ink on paper

8 3/4 x 8 3/4 inches (22.2 x 22.2 cm)

Agnes Martin

Untitled, c. 1975

Transparent watercolor, black ink, and graphite on paper

9 x 9 inches (22.9 x 22.9 cm)

Kinke Kooi

Man, 2001

Acrylic paint, pencil, and color pencil on paper

21 1/4 x 28 1/2 inches (54 x 72.4 cm)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Reclining Female Nude, c.1915

Graphite on paper

12 3/16 x 18 9/16 inches (31 x 47.1 cm)

Elaine de Kooning

Portrait of Bill, 1950

Brown ink on paper

8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

Robert Corless

Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1963

Pencil and collage on paper

11 x 9 inches (27.9 x 22.9 cm)

Sigmar Polke

Ohne Title (Umarmung), [Untitled

(Embrace)], 1963

Ballpoint pen on paper

11 5/8 x 8 1/4 inches (29.5 x 21 cm)

Pascal Adolphe-Jean

Dagnan-Bouveret

Head of Apollo, 1901

Pencil and pastel on paper

21 9/16 x 18 3/8 inches (54.8 x 46.7 cm)

R. Crumb

R. CRUMB by R. CRUMB, 2020

Pen, ink, and white paint on paper

11 3/4 x 8 7/8 inches (29.8 x 22.5 cm)

Paul Thek

Self-Portrait, c. 1969

Graphite on paper

10 5/8 x 7 3/4 inches (27 x 19.7 cm)

Marsden Hartley

Self-portrait #11, c. 1908

Black crayon on paper

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Adolph Friedrich

Erdmann von Menzel

Head of a Man, 1886

Graphite, stumping, and watercolor on paper

Ferdinand Hodler

Georges Navazza, 1916

Pencil on paper, squared

15 3/4 x 12 3/8 inches (40 x 31.4 cm)

Gaston Lachaise

Dancing Female Nude with Headdress, n.d.

Pencil on paper

23 1/2 x 18 1/2 inches (59.7 x 47 cm)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Portrait of Alexis-René Le Go, 1836

Graphite on paper

11 7/8 x 8 3/4 inches (30.2 x 22.2 cm)

George Grosz

Stehender Akt (Standing Nude), c. 1927–28

Graphite on paper

23 5/16 x 9 5/16 inches (59.2 x 23.7 cm)

Raphael Soyer

Self Portrait and My Father, n.d.

Pencil on paper

10 3/4 x 8 inches (27.3 x 20.3 cm)

François Boucher

Head of a Young Woman, c. 1754

Black and white chalk on paper

13 7/8 x 9 7/8 inches (35.2 x 25.1 cm)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Le Violiniste Dancla (The Violinist Dancla), n.d.

Pencil on paper

7 x 8 1/2 inches (17.8 x 21.6 cm)

Henri Matisse

Marocain, mi corps (Morrocan, Bust), 1912–13

Graphite on paper

10 x 7 1/2 inches (25.4 x 19.1 cm)

Walt Kuhn

Study of a Clown, 1932

Graphite on paper, with an ink drawing of a woman on the verso crossed out with a red crayon

15 1/2 x 10 1/4 inches (39.4 x 26 cm)

John. D. Graham

Head of a Young Woman, 1944

Silverpoint and graphite on paper

9 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches (24.1 x 24.1 cm)

Odilon Redon

La Terrible (The Terrible One), c. 1871

Charcoal and black chalk on paper

16 3/4 x 13 1/4 inches (42.5 x 33.7 cm)

Oskar Kokoschka

Reclining Female Nude, c. 1911–12

Charcoal and crayon on paper

12 1/2 x 16 11/16 inches (31.8 x 42.4 cm)

Kenneth Price

African Lover, 1982

Graphite on paper

9 1/4 x 8 1/2 inches (23.5 x 21.6 cm)

Kinke Kooi

Woman, 2001

Color pencil on paper

24 x 30 1/2 inches (61 x 77.5 cm)

George Grosz

Er will nicht stehen (He Doesn’t Want to Stand), 1929

Graphite on paper

18 1/8 x 23 5/8 inches (46 x 60 cm)

© 2021 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

George Grosz

Erotische Szene (Erotic Scene), c. 1939 Oil, watercolor, and charcoal on paper

18 1/8 x 23 1/4 inches (46 x 59.3 cm)

Roy Lichtenstein

Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But...(Study), 1964

Color pencil and graphite on paper

5 3/4 x 5 5/8 inches (14.6 x 14.3 cm)

Take

State of Emergence

Take

State of Emergence

On long drives the landscape changes subtly. A hundred miles on a flat highway makes me notice how the clouds overhead cast tectonic shifts of light and dark over the land and the way the asphalt road is a line, a gesture unfurling toward the horizon. When the music is good, I can’t shake the sense that I’m watching an incredibly good, unbelievably slow movie. Though the experience is better than a movie, because without characters or plot, my thoughts and feelings are allowed to wander, unfolding like the scenery. It’s a mental space good for working stuff out, meditative but also productive in an undirected way. The music becomes a medium I’m suspended in, moving through time and space; the lyrics, the melodic structure, the specifics of phrasing—the things I usually enjoy in the back of my mind suddenly gush forward.

I’m always looking for an excuse to hop in my car and get out of New York City, so when I was invited to visit Jack Shear in Chatham, New York, on the premise of working on an exhibition of works from his collection, I was happy to get two-and-a-half hours of thinking done on the Taconic State Parkway. On a drab mid-winter morning the drive itself was uneventful—perfection. I was listening to Björk’s Homogenic (1997), an album I’ve heard a lot over the years, but this time it felt like a fucking revelation. By the second song, “Jóga,” the lush strings start to swell, undergirded by a strange irregular rhythm, the unexpected setting for her extraordinary voice, singing: Emotional landscapes / they puzzle me / confuse / then the riddle gets solved / and you push me up to this… which reenacts sonically what it describes lyrically. Eliding and expanding an interior life with the vistas of the world, “Jóga” is an environment more than a pop song. It perfectly captured the experience of interiority, being in a car alone with my thoughts and speeding down the road looking

at barren trees and gray skies. Things can click together like that, unexpectedly, when you’re ready..

I arrived at the elegant complex of buildings tucked into the trees that were Ellsworth Kelly’s painting studios until his death in 2015. Shear, Kelly’s longtime partner, is currently using some of the space there to store and display the extraordinary collection of drawings he has been putting together since Kelly’s passing. The idea, as Shear explained it to me, is to assemble the most interesting group of drawings he can find—rare, unusual, unbelievably expensive—and then donate it to a teaching collection or university that could otherwise never afford to bring these works together. Shear is interested in giving young artists and historians the opportunity to study them firsthand. I was especially intrigued when he told me that, in addition to indulging his own eccentric interests, he also buys drawings by artists he doesn’t necessarily “like” if he thinks the work is good and that it embodies something unique or important about drawing.