The Way He Sees It: KAWS’s Collection and Expanding the Definition of a Great Work of Art

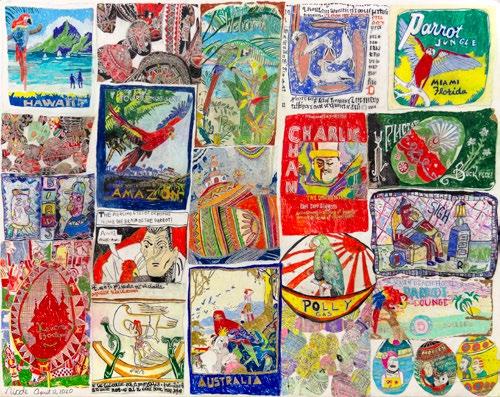

Describing Brian Donnelly’s astonishing collection of thousands of works of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art, the art historian Thomas Crow asserts that it is an argument for “an alternative fine art tradition,” not merely an accumulation of objects.1 Indeed, the ambitious challenge to broaden the definition of great drawing to include graffiti sketches, comics, and illustrations—as well as the work of artists who are self-taught, neurodivergent, or have been otherwise overlooked or dismissed by the fine art establishment—is surprisingly met in The Way I See It, an exhibition of more than 350 works on paper chosen by Donnelly himself from his vast collection compiled over nearly twenty-five years of eager, inspired looking.

Donnelly is an artist who works under the pseudonym KAWS, and there is little doubt that his profession has had a profound impact on what he has chosen to collect. The inverse is also true: what Donnelly loves and has chosen to collect has had a significant impact on the kind of art KAWS has made over the course of a wildly successful career. After studying illustration at the School of Visual Arts in New York, an experience that he loved because it was a “trade school,”2 KAWS made a name for himself first as a graffiti artist whose tags morphed into intentional interventions on publicly-situated advertising on billboards and bus shelters. These performative acts of public drawing introduced KAWS’s signature vocabulary that starred a cohort of adorable but existentially burdened figures with Xs over their eyes, making them look like they were sleeping—or dead. These figures, which now appear in paintings

1 Thomas Crow, “Family Ties: The Characters of KAWS,” in Thomas Crow, Dan Nadel, Clare Lilley, KAWS (New York: Phaidon Press, 2023), 66.

2 Dan Nadel, “Dan Nadel in Conversation with KAWS,” in Crow et al., KAWS (New York: Phaidon Press, 2023), 12.

and as monumental sculpture, collectibles, and motifs on products continue to be popular internationally, making KAWS among the best-known visual artists on the planet—a position earned by working outside the conventional art world establishment and without the benefit of blue chip galleries, museums, or high-profile experts celebrating his artistic bona fides.

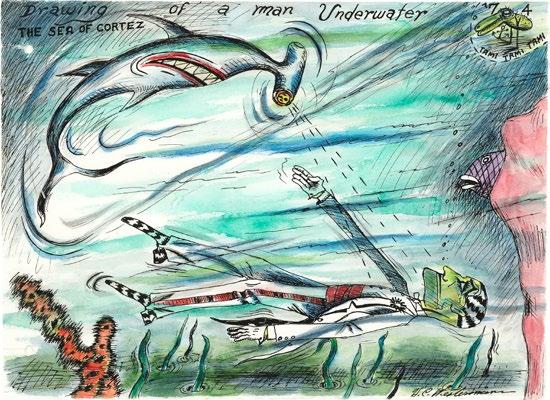

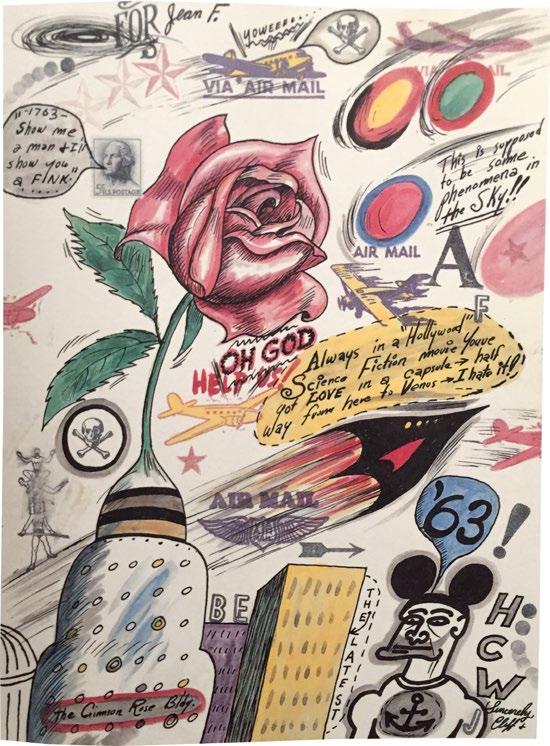

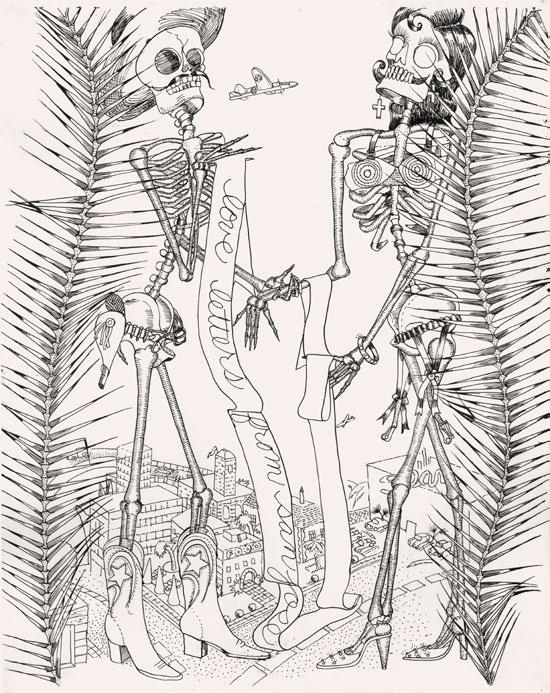

The connection between KAWS’s production as an artist and his collection is not straightforward, but both his artistic practice and his collecting one seem bent on changing the aesthetic rules for the creation and reception of contemporary art. “I feel like we grew up on a model of what a visual artist can be,” he confided to Dan Nadel in an interview published in 2023, “I don’t think it needs to end there. I feel that there could be more.”3 That “more” resides in KAWS’s collection, a veritable garden of masterpieces by well-known and unknown artists. The collection features areas of depth: holdings of works by Peter Saul, H.C. Westermann, Helen Rae, and Susan Te Kahurangi King run in the high double digits. The collection also includes entire archives: “black books” of sketches by some of the best-known American graffiti writers and the artistic estate of Rae are two examples. He has amassed equally comprehensive and impressive groups of drawings by historically significant selftaught maestros like Martín Ramírez, Adolf Wölfli, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, and Henry Darger, a group that is counterbalanced by holdings in drawings by canonical artists like Pablo Picasso, Willem de Kooning, and contemporary artists like Dana Schutz. When asked about the variety represented in his trove he gnomically commented, “I do like playing with systems.”4

KAWS’s career has successfully bridged the gap between sotermed commercial art and fine art, a stubborn gulf in contemporary American culture that still upholds a hierarchy created by museums and academics in the business of constructing stories of innovation, influence, and progress in visual art that function like mathematics problems always producing a logical, better result. A traditional art museum display is built on “hierarchies of value” presented as “natural truths.”5 In reality though, hierarchies that prize, for example, art by educated Europeans over self-taught ones or objects created to be looked at rather than utilized are social constructions

3 Nadel, 20.

4 Ibid., 40.

5 Susan M. Pearce, On Collecting: An Investigation into Collecting in the European Tradition (New York: Routledge, 1995), 141.

Laura Hoptman

created by a ruling culture to shore up its values.6

KAWS’s career has challenged and to some extent bested the hegemonic lens of the institutional art world in part because of the international popularity of everything he makes, whether it is a painting or a collectible doll. The content of his collection likewise implicitly questions the gate-keeping power of the art institution. Going a step further—after obliterating barriers to the inclusion of socalled “commercial art” as well as artists working outside of cultural centers who have not trained as artists—the collection radically expands our understanding of what constitutes a work of art in the largest sense. It should come as no surprise that by broadening the fine art lens to include genius in a whole host of creative genres, a flood of artists who are women, people of color, neurodivergent, disabled, and elderly become part of this new artistic pantheon.

While the most obvious thread that ties a collection together is the collector’s personal taste, there are commonalities of form and strategy that visually connect artists in a collection that includes work by both Abstract Expressionist hero de Kooning and self-taught, deaf, non-verbal artist Helen Rae. Crow succinctly summarizes the connection between the diverse works in KAWS’s collection as “figurative work friendly to vernacular forms,”7 a helpful description though it subtly privileges the generic fine art phrase “figurative work” by designating it as the generative form that describes a supposedly fine art “unfriendly” cohort of underground comix, graffiti writing, and the like. Carlo McCormick, the impresario and critic of record of the wildly eclectic East Village art scene in New York in the 1980s, has a more nuanced take. Noting that KAWS himself cannot be altogether accurately labeled “an artist who does commercial art,” he emphasizes that he is not “a commercial artist who does fine art” either.8 In McCormick’s eyes, KAWS’s oeuvre is decidedly hybrid, functioning in both accessible commercial markets including fashion, skate culture, popular music, toys and collectibles, and in fine art precincts in major cities around the globe. The same can be said for the art that he has amassed.

KAWS has neatly identified the divide between these two areas as a matter of “distribution,”9 but there is also an issue of reception.

6 Pearce, 141.

7 Crow, 66.

8 Carlo McCormick, “KAWS’ World,” Paper Magazine 30, no. 3: November 2013.

9 Ibid. KAWS remarked to McCormick that “distribution” explained the difference between fine art and commercial art.

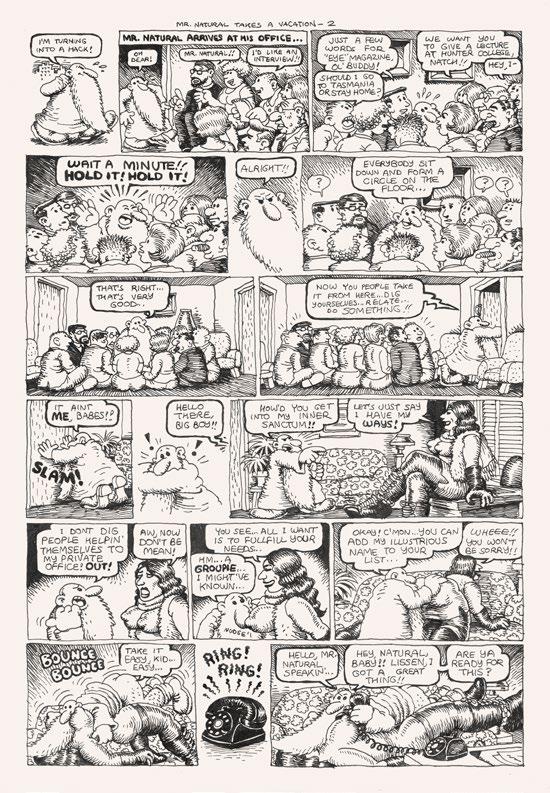

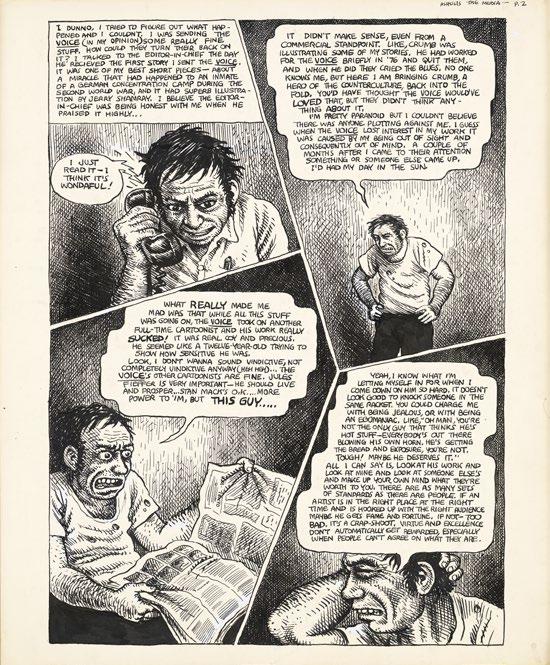

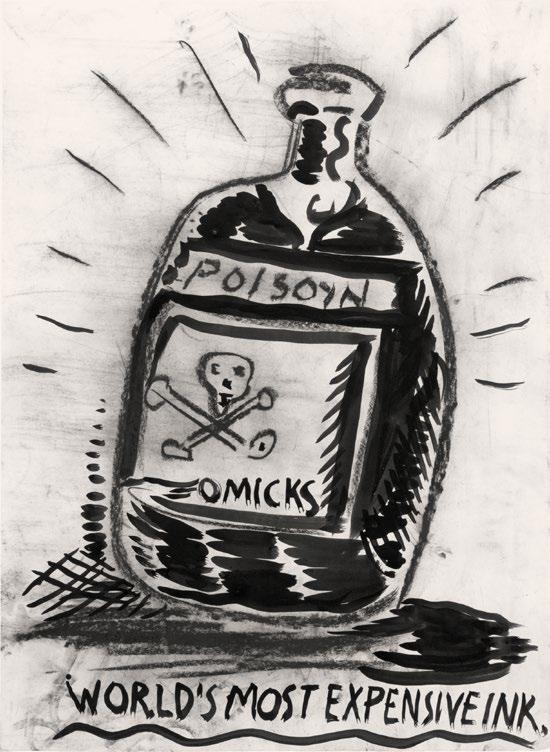

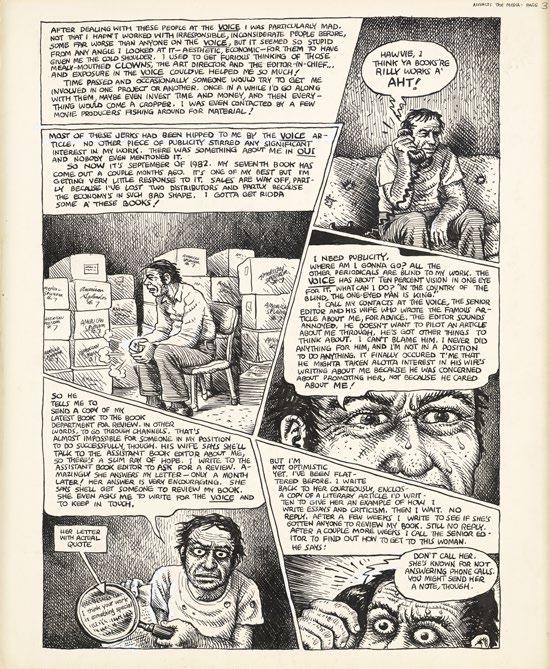

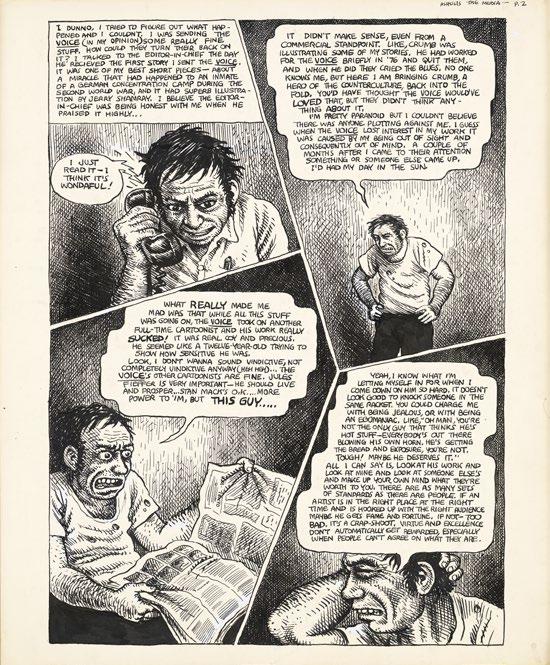

However accessible digital media has made images of objects, the audience for KAWS’s figurines and T-shirts still very likely differs from those who covet the paintings and sculptures he exhibits in galleries. It is in this divide that KAWS’s collection does its radical work. Many drawings featured in The Way I See It have standing in both the world of popular arts and in the art museum. In fact, KAWS’s first purchase of a work of art from an art gallery was a drawing by the Los Angeles-bred, New York-based artist Raymond Pettibon.10 Beginning in the 1970s, Pettibon has deployed a blackand-white pen-and-ink drawing style directly inspired by comic strips. Gleefully stealing characters from comic books and animation from 1950s and ’60s America like Gumby and Vavoom, the screaming character from the Felix the Cat comics, Pettibon chooses to draw individual scenes—as opposed to narrative comic-strip sequences— which he initially self-published in zines or gave to his musician brother to use as cover art on his bands’ albums. Each drawing is captioned, but the statements cribbed by Pettibon come from entirely different kinds of sources than typically found in comics, including European philosophical essays, novels, and historical epigrams. Within each Pettibon is a clash of sources that makes his work neither comics nor so-called “fine art” drawing. They are hybrids or, more interestingly, bridges between two cultural worlds that might flirt with one another while keeping their distance. More daring than the comic appropriations of Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings or the riffs on commerce that are Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes—both of which created their frissons by dragging bits of mass culture into high art domains—Pettibon’s drawings refuse both contexts of high and low, a radical position to take in a field based on taxonomies. KAWS is resistant to the idea of defining his own practice within specific categories. As he commented in a recent interview about his own work, “People tend to make categories for everything. I don’t consciously stay within a category. Works have their presence and speak to you in different ways, and I don’t need to fully understand it to take time to appreciate it.” This is also true for his collection. “There isn’t one type of work that I am drawn to,” he emphasized recently in a discussion about the art he buys, “it’s dozens!”11 The most obvious connection is that all of the works in the show are more or less figurative. With the exception of the sublime quasi abstract

10 Too intimidated to walk into a major art gallery, Donnelly actually purchased the work from an online viewing room.

11 KAWS, unpublished interview with the author, June 12, 2024.

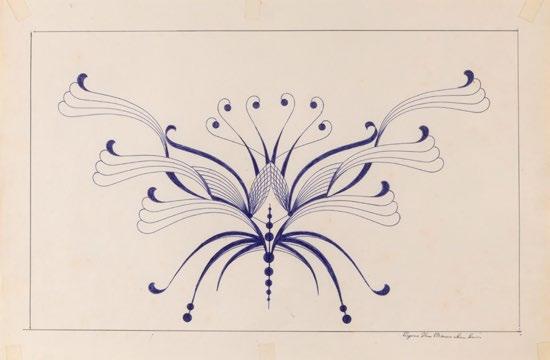

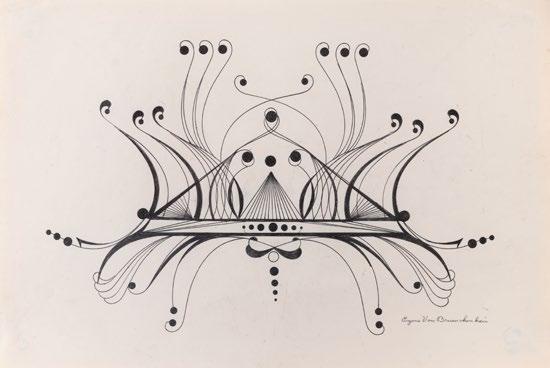

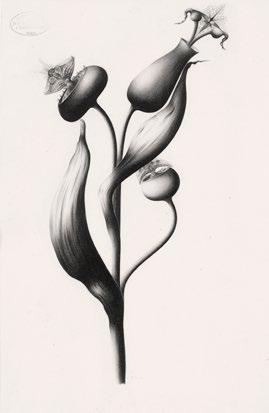

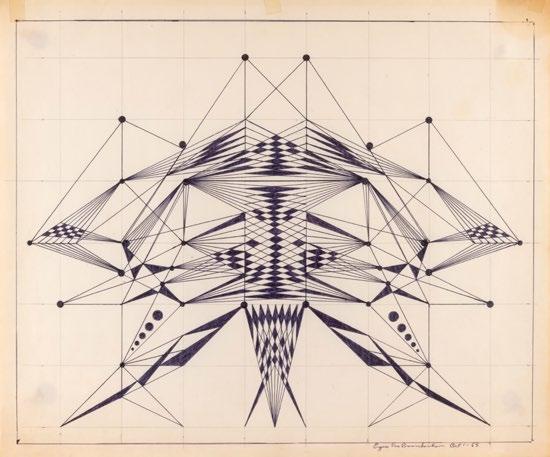

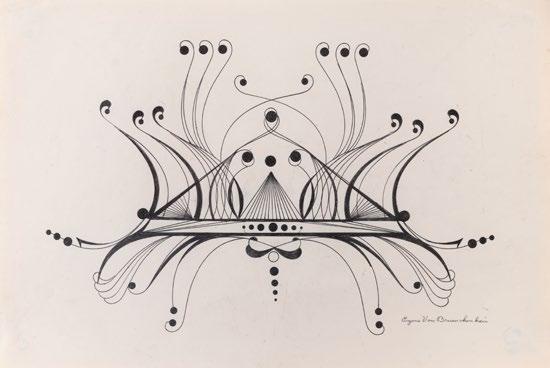

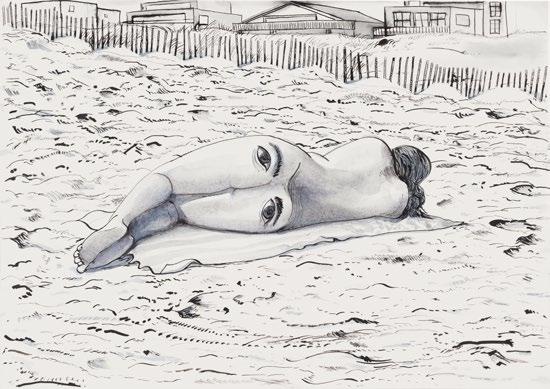

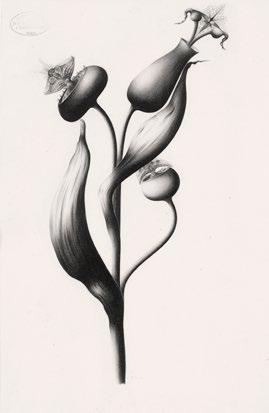

floral pen drawings by Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910–1983), a self-taught Milwaukeean who called himself a “Freelance Artist— Poet and Sculptor—Innovator—Arrow maker and Plant man—Bone artifacts constructor—Photographer and Architect—Philosopher,” figuration reigns. As does a preference for the graphic—sharp lines, bright colors, eye-catching compositions. Realism, Photorealism, and even trompe l’oeil are everywhere in the collection, a testament to a compiler’s taste for skillful draftsmanship. This ability to draw with hyper-accurate, eye-fooling realism is what Crow calls the kind of “defiant skills” that qualify “for inclusion in KAWS’ pantheon.”12

“Defiant” is a telling adjective for an art historian like Crow, whose expertise ranges from nineteenth-century Impressionism to the work of Andy Warhol, because it speaks to a clear agitation against the status quo, which in this case is the European modernist tradition. As the admittedly bracing teleology of Euro-American art history tells us, once a credible facsimile of three dimensions was achieved on a twodimensional surface—first through the use of perspective and oil paint and subsequently with the invention of the photograph in the early nineteenth century, art “advanced” through innovations in form, building towards total non-objectivity. To certain idealists, art was on a trajectory to unleash itself from what we know in order to pursue the broader mystery of existence, not through imitation, but through the imagination. At mid twentieth century, the European continent lay in actual ruins, but it was also ideologically bifurcated by two of the victorious countries at odds with one another: the United States and the U.S.S.R. In culture, the United States flooded Western Europe with money, movies, and material aid, but the American government, partnering with major museums, also organized art exhibitions of abstract painting—artworks that were larger and more unruly than the domestic-scaled geometries of the remnants of the ateliers of the School of Paris and that, most importantly, told no stories beyond those implied through color and gesture. Whether or not governmentsponsored exhibitions like the retrospective of the paintings of Jackson Pollock, which swept through major European capitals in 1957, two years after the artist’s death, had a government-sponsored political impetus at the time has been excavated only in retrospect,13

12 Crow, 52.

13 See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983); Eva Cockcroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” Artforum, Summer 1974; and other scholarship on the intervention into visual culture by the government in midcentury America.

but by the end of World War II artistic styles in Europe and the United States were deeply politicized. Social (or Socialist) Realism had been adopted as the state style of the Soviet Union in 1934, while in Nazi Germany, Hitler and his henchmen began a campaign against abstraction, labeling it a “degenerate” product of Judaism, Communism, or both. Fascism was defeated, but for some the taint of totalitarian politics stuck to the language of realism in Europe. The new American abstraction then, aided by enthusiastic US propaganda, seemed to present an antidote to the hectoring readability of Social Realist murals and monuments. Paintings by Pollock or Mark Rothko or Franz Kline were full of emotion and formal incident, but they existed on a plane reserved for art, divorced from daily life and the realpolitik of the burgeoning Cold War.

It seems simplistic to argue that by the mid-1950s in the United States and in Europe, a great deal of figuration was categorized as either an indication of Communist sympathies or reactionary ones. But the assertion is no less true for being obvious. This tension between high and low, elite taste and the popular kind played out in the United States as well. The most popular artist in America at midcentury was the hyperrealist painter of rural America, Andrew Wyeth, but high art institutions and critics mostly ignored him. Though purchased by major museums for astonishing sums for the time, Wyeth’s paintings were hung in museum hallways or not at all, as their existence contradicted the triumphant story of modernist abstraction being concocted by American cultural institutions like The Museum of Modern Art. In art magazines, Wyeth’s work was gleefully pitted against Pollock’s paintings as a fight between the reactionary and the avant-garde, the full-throated defense of Wyeth by Abstract Expressionist painter and Artnews critic Elaine de Kooning notwithstanding.14

Skipping seventy years to the first two decades of the new millennium, we find ourselves surrounded by contemporary artists working in myriad styles and diverse materials. Stylistic ideology seems to have been drowned in joyful eclecticism, as staunchly modernist institutions cede wall space not necessarily to Wyeth (perhaps a bridge too far?), but to Alice Neel, T.C. Cannon, Kerry James Marshall, Henry Taylor, and Salman Toor. In the contemporary

14 See “Andrew Wyeth Paints a Picture,” Artnews 49, no. 1 (March 1950): 38–41, 54–56. Wyeth did turn out to be an artist of the political right wing, a position that he signaled publicly by declining an invitation to the White House by John F. Kennedy and later accepting one from Richard Nixon.

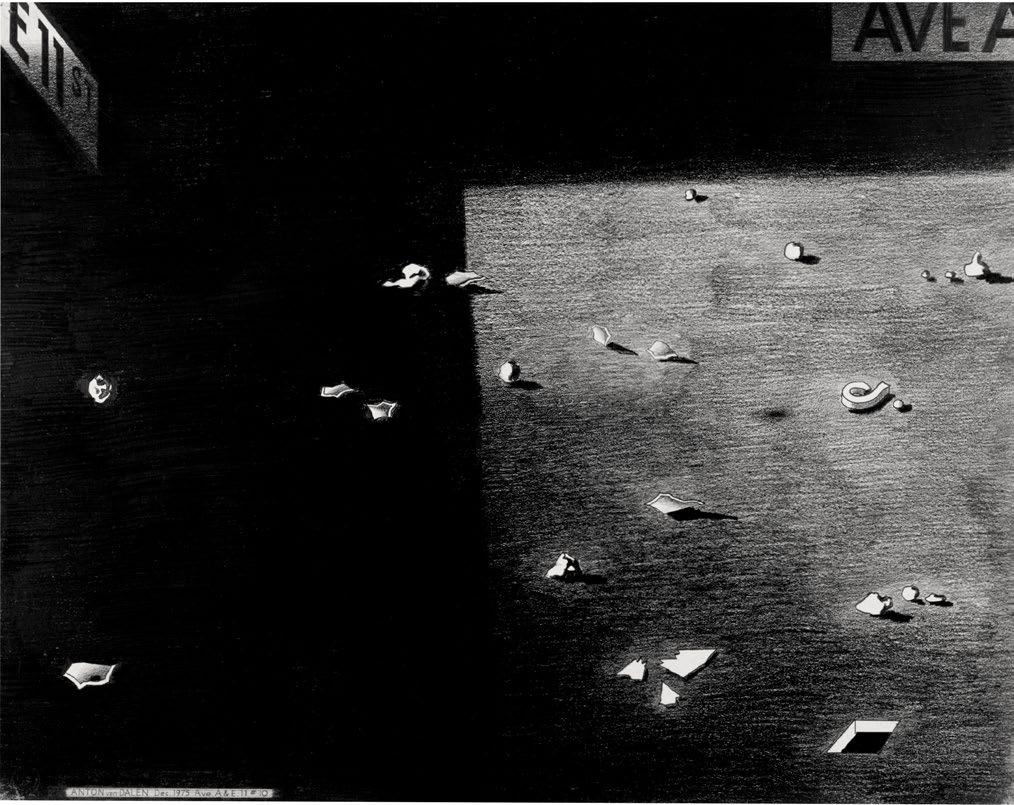

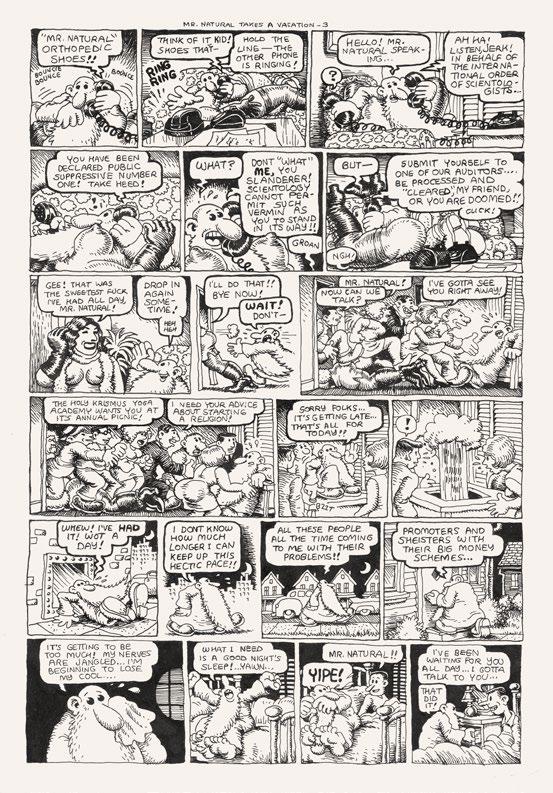

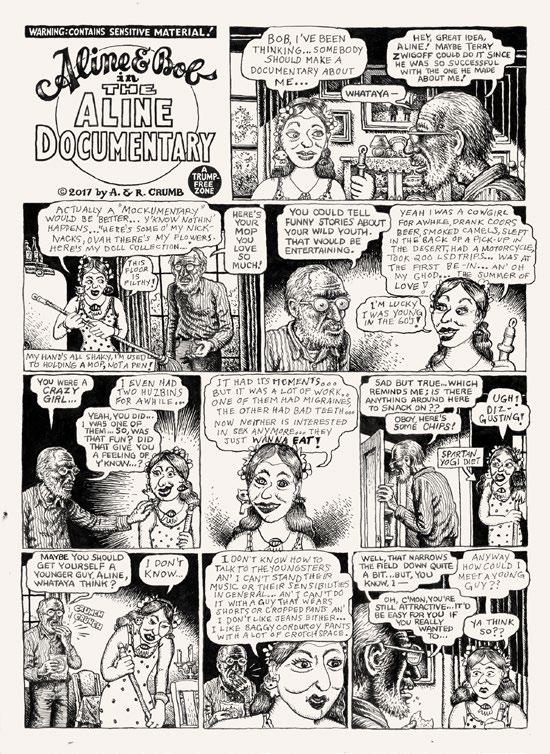

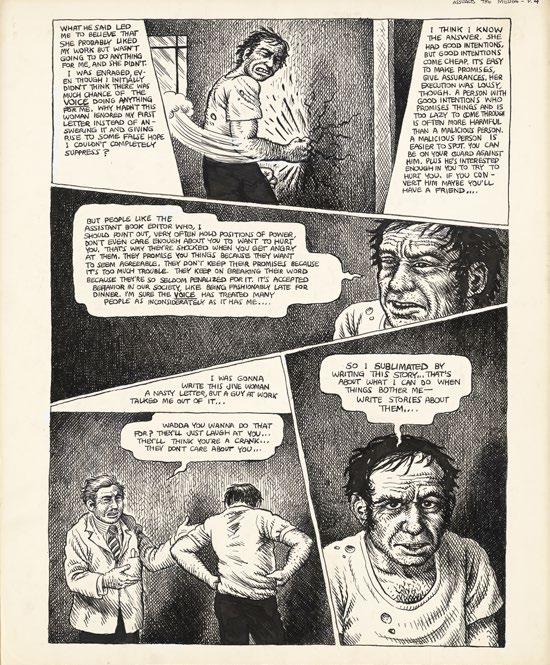

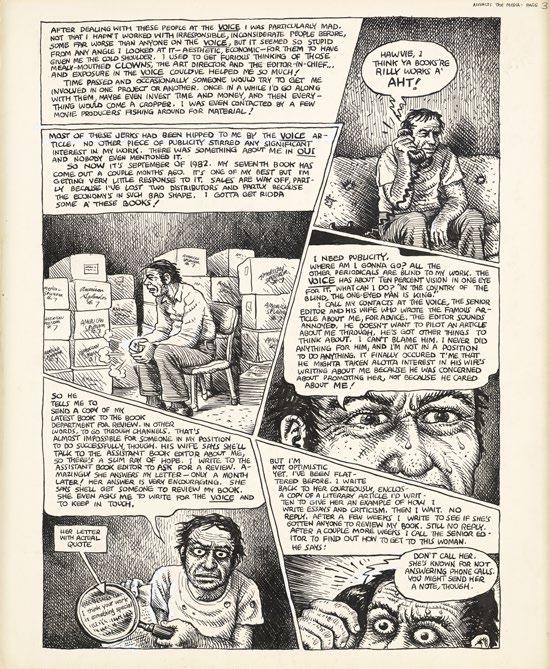

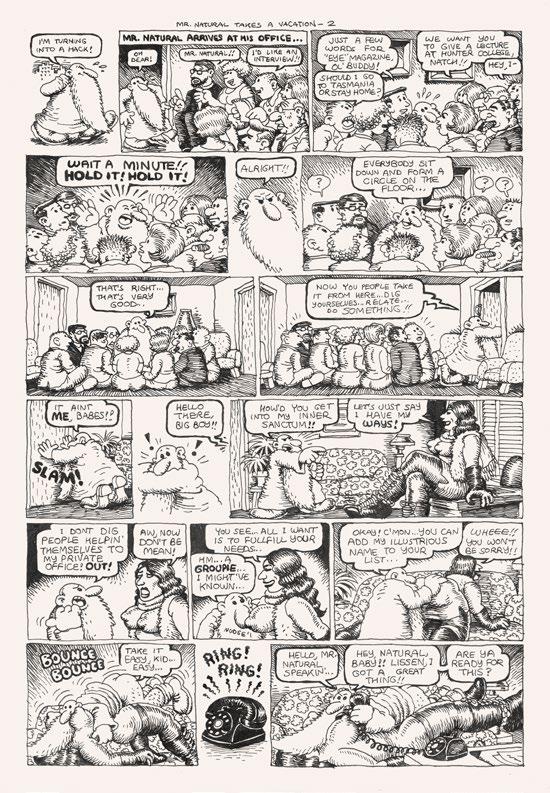

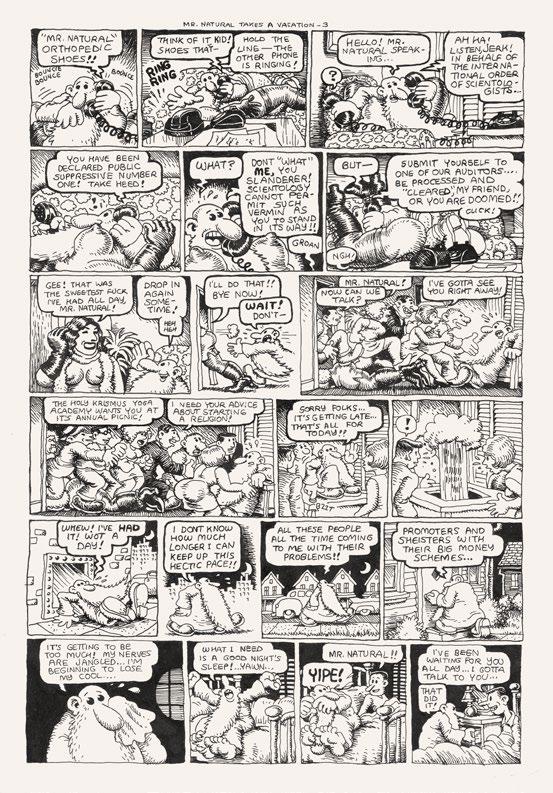

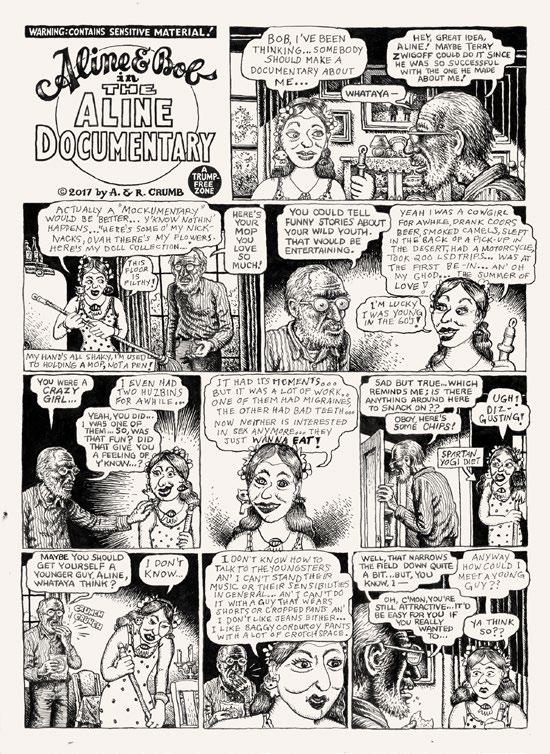

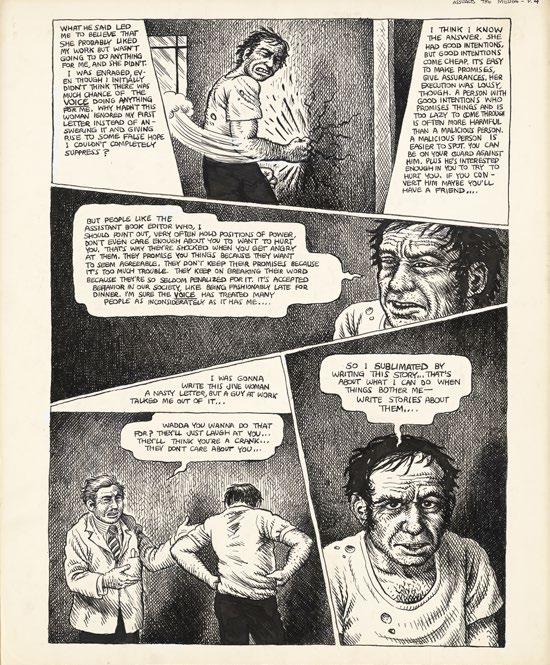

discourse in Europe and America in the 2020s, figuration has shed its reactionary/radical political connotations, but unspoken taboos barring “popular” art forms like comics, illustrations, and graffiti writing from art museums and galleries showing contemporary art by trained artists still remain. Some of the greatest drawings of the twentieth century were produced by self-taught artists like Martín Ramírez (1895–1963), comic book creators like R. Crumb (b. 1943), and graffiti writers like Lee Quiñones (b. 1960), and it is this kind of work that KAWS delights in, celebrates, and collects with scholarly diligence. The proof ultimately lies with what we see with our own eyes. Most of us know a great drawing when we see it, and in The Way I See It, we encounter hundreds of them, from Hilma af Klint’s (1862–1944) vision of an aurora to Anton van Dalen’s (1938–2024) shadowy East Village street scenes.

In a comprehensive study of the social history of collecting, the British academic Susan Pearce defines a collection as “a group of objects, brought together with intention and sharing a common identity of some kind, which is regarded by its owner as, in some sense, special or set apart.”15 Sets of objects organized obsessively, collections are “an act of the imagination…”16 and a “metaphor intended to create meanings which help to make individual identity and each individual’s view of the world.”17 Pearce makes the argument that the idea of collecting is at base an act of preservation and ordering; in other words, a modern way of figuring things out, born of the belief that making sense of vast data sets is a hedge against the chaos and mystery of the world around us. “The establishment of a patterned system into which all the diversity of nature could be fitted chimed in at once with the deist theory of the Enlightenment, and the corresponding modernist belief that the physical process of material observation and measurement by a rational man could result in objective knowledge and truth,” she writes.18 For Pearce, collecting is a perfect example of a kind of vertical mapping of history that privileges a single storyline of innovation and progress, discoverable through quasi-scientific acts of taxonomy. If one buys that the act of collecting itself is an expression of a modern view of human progress, then KAWS’s accumulation of thousands of artworks is one of the many views of culture we can

15 Pearce, 159.

16 Ibid., 21.

17 Ibid., 72.

18 Ibid., 124.

enjoy now that modernism has gotten out of the way. In Pearce’s view, it might not be a collection at all as in sum it creates not a roadmap to the stars, but a horizontal landscape without visible borders of vastly different kinds of creativity on paper.

“Collections can be used to construct a world which is closer to things as we would like them to be, and the colloquial use of ‘things’ in a phrase such as this is revealing. We can use them as a material dialogue between ‘I’ and ‘me,’ and so create a way of working out an intentional inscription on the world,” Pearce writes.19 KAWS reveals that for him, collecting is much more than a pleasurable hobby. “It’s like food,” he told Dan Nadel. “It’s like energy. It’s what keeps me thinking.” He continues, “I guess that collecting is like having skin in the game.”20 This admission is as close as KAWS gets to revealing that there is a purpose to all of this acquisition. Taken as a whole, the artists in KAWS’s collection create “an alternative fine-art tradition to which [KAWS] could imagine belonging.”21 While the KAWS collection proposes a broader, more inclusive history of draftsmanship, at the same time it creates a rich context for the artwork by artists whose work has rarely been featured on museum or gallery walls. “The objects I collect are what I’ve gravitated towards my whole life, and how I felt my whole life,” he commented to Nadel, concluding however that, “I still feel outside.”22

Crow argues that KAWS’s all-encompassing art project plus his collecting “add up to a persuasively alternative history of recent art that supplants the faltering textbook versions still holding sway over young artists,”23 even as the collection does “not demonstrate knowledge.”24 It is knowledge. This is borne out in KAWS’s carefully assembled groups of things, some of which we have never seen before; many, we never considered under the rubric of art. The Way I See It offers an entirely new body of information that has the potential to alter the landscape of the known world of contemporary visual culture. It is neither a roadmap nor a lens but rather a welcoming entrance to a broader, more scintillating, more nuanced, more diverse universe of human creativity whose only boundary is the human vision that has discovered it.

19 Ibid., 176.

20 Nadel, 43.

21 Crow, 66.

22 Nadel, 41.

23 Crow, 52.

24 Pearce, 111.

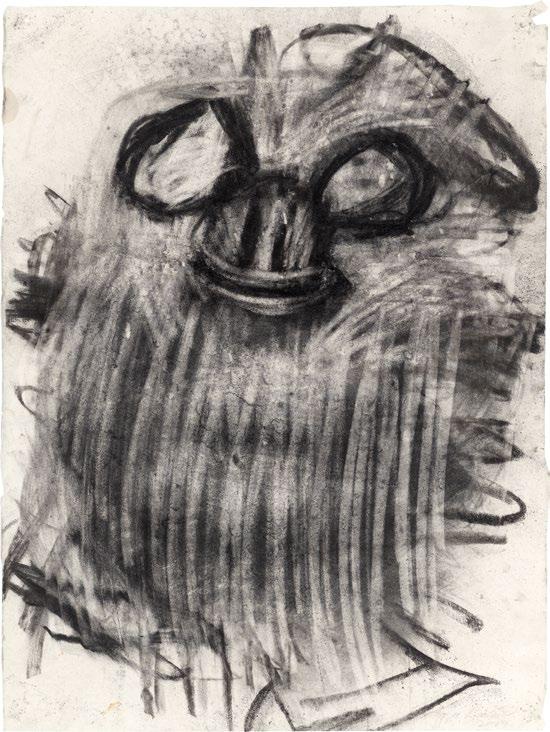

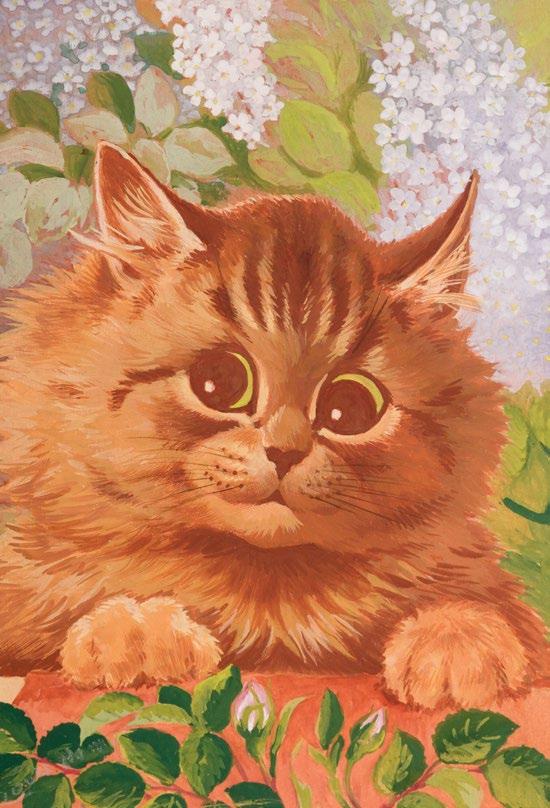

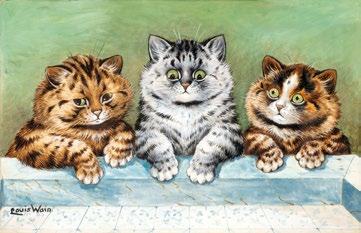

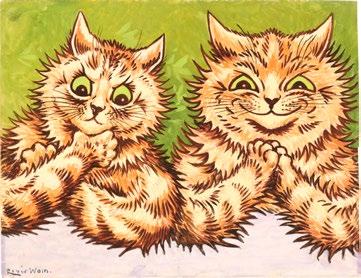

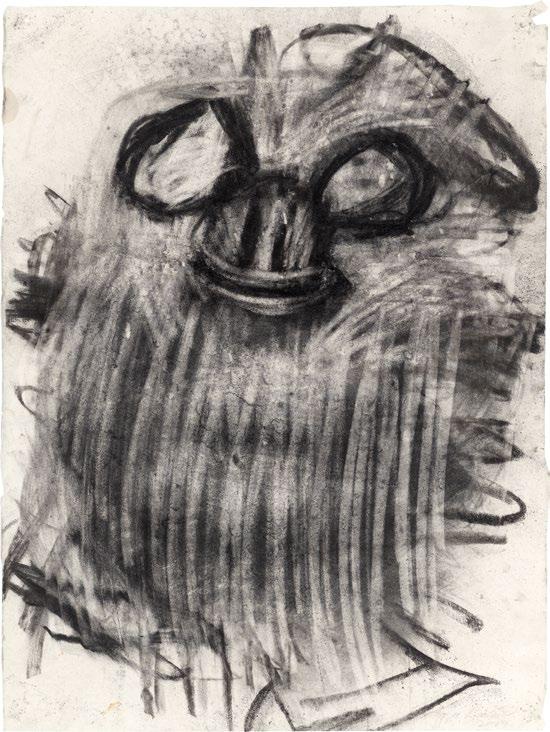

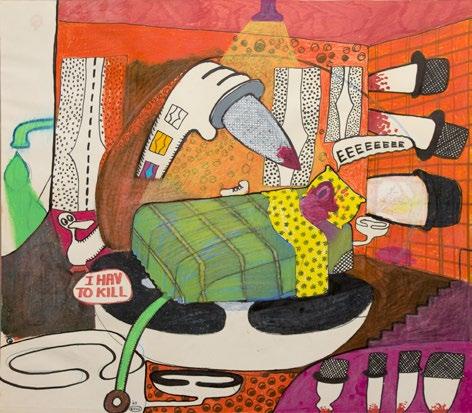

Brooklyn native Joyce Pensato (1941–2019) gained recognition relatively late in her career, participating in group exhibitions starting around 1993 and receiving her first solo exhibition in 2007 at sixty-six years old. As a young woman, Pensato studied at the Art Students League in New York and then the New York Studio School, where she enrolled in 1973 and remained as a resident for several years after she graduated. She started making still-life drawings of pop culture detritus found on the street and in thrift shops while at the Studio School, the first being a charcoal drawing of a life-size Batman cardboard cutout. However, she considered her Abstract Expressionist landscape paintings the primary part of her artistic production at the time. In the 1990s, Pensato decided to abandon colorful oil painting and began to translate her charcoal figures into black, white, and silver enamel paintings. Her subjects include icons of American popular culture, from Muppets to Disney characters, The Simpsons, and superheroes, as well as her own character, The Juicer, rendered so they vibrate with menace and emotion. —IK

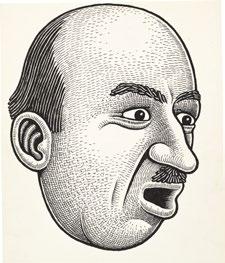

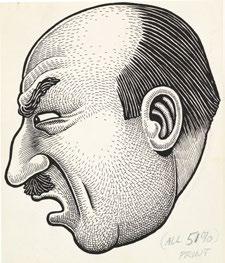

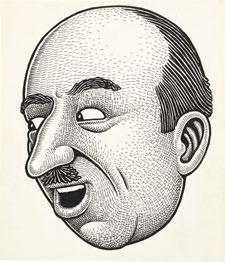

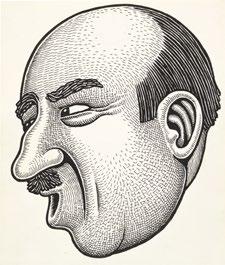

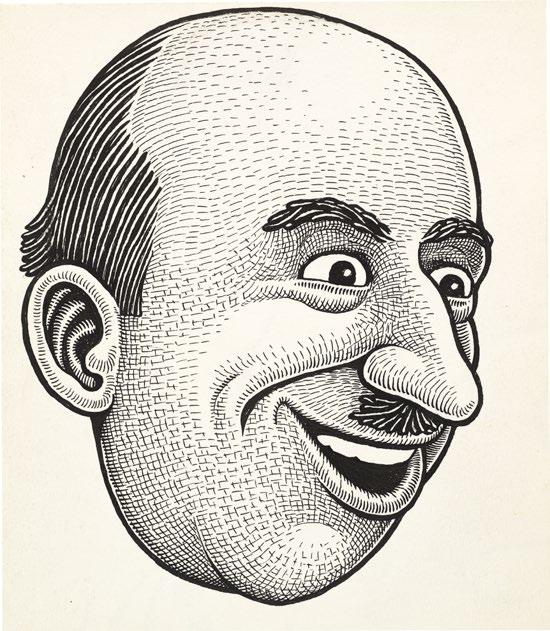

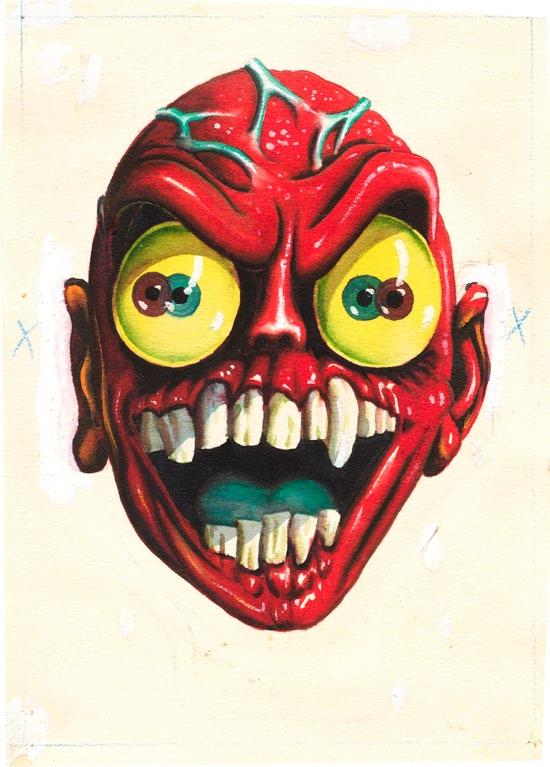

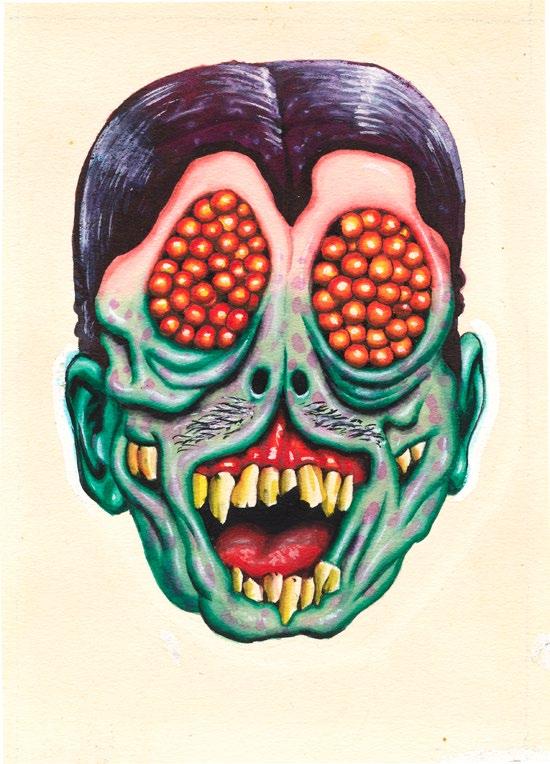

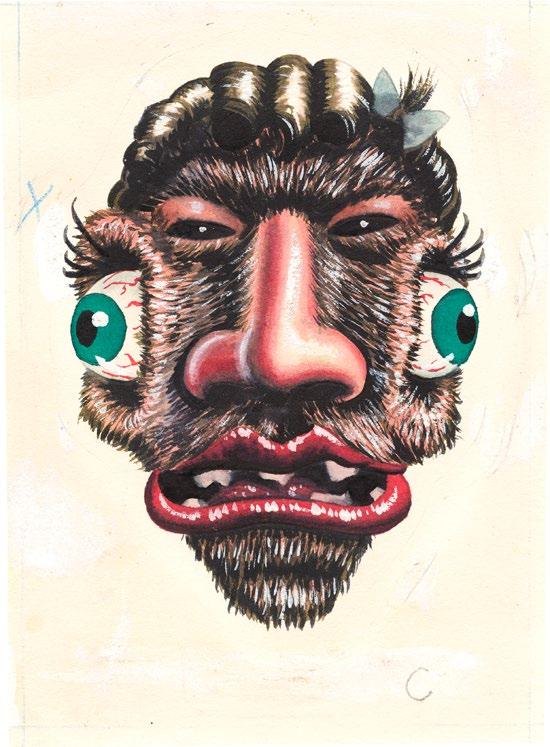

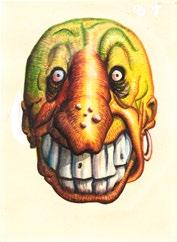

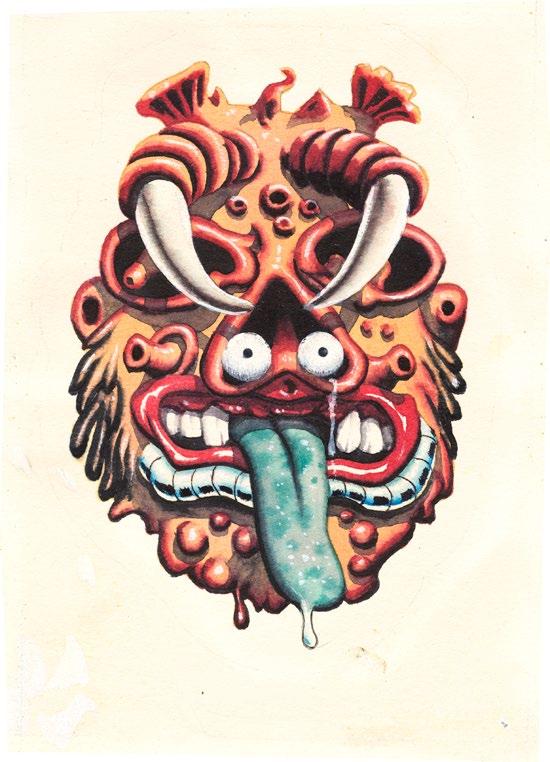

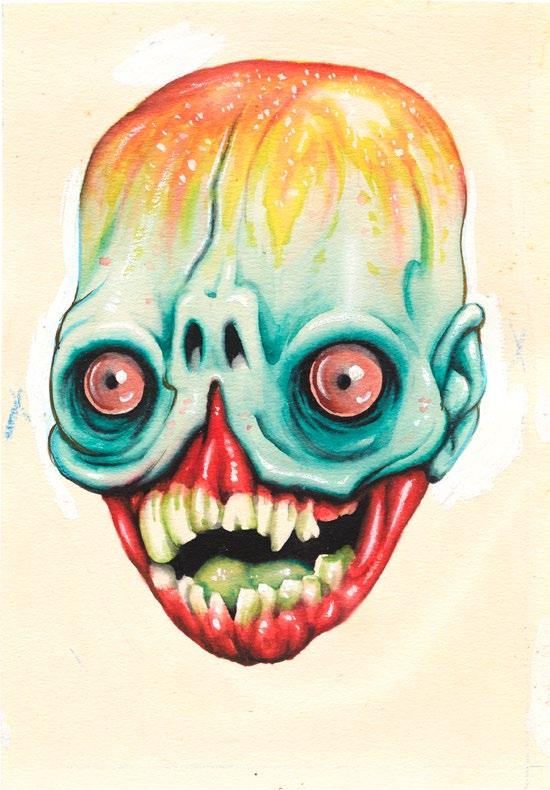

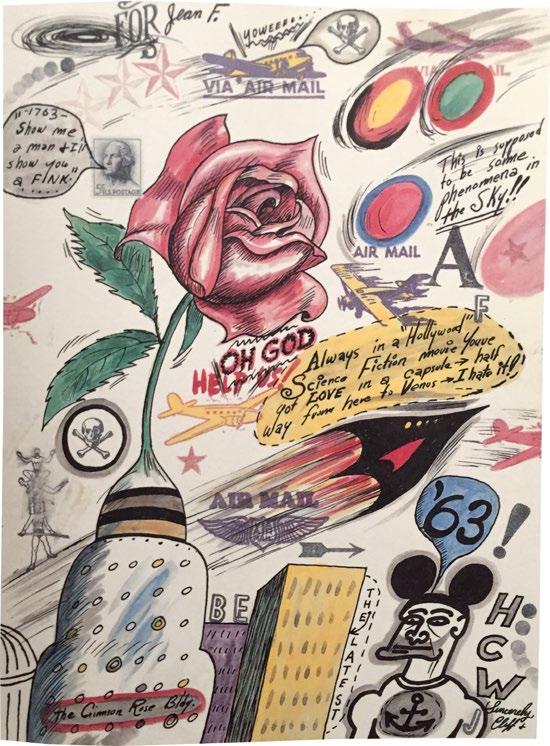

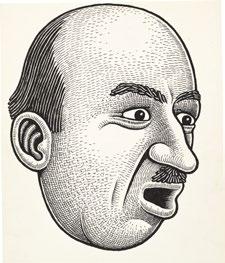

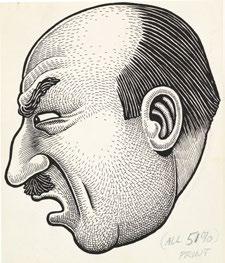

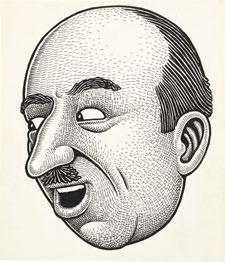

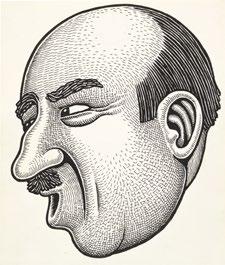

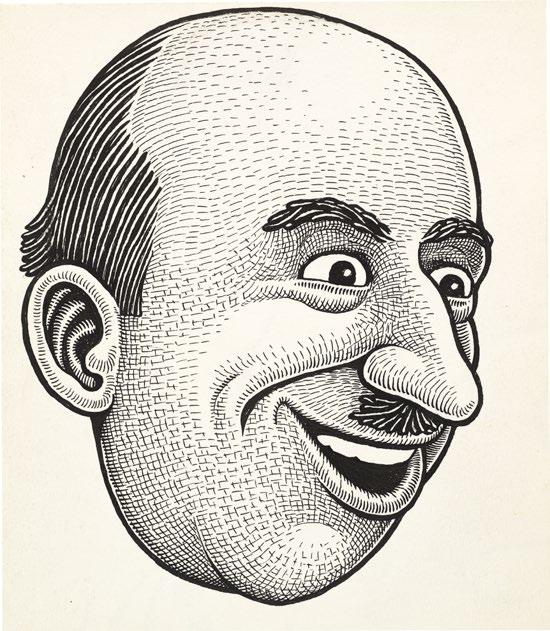

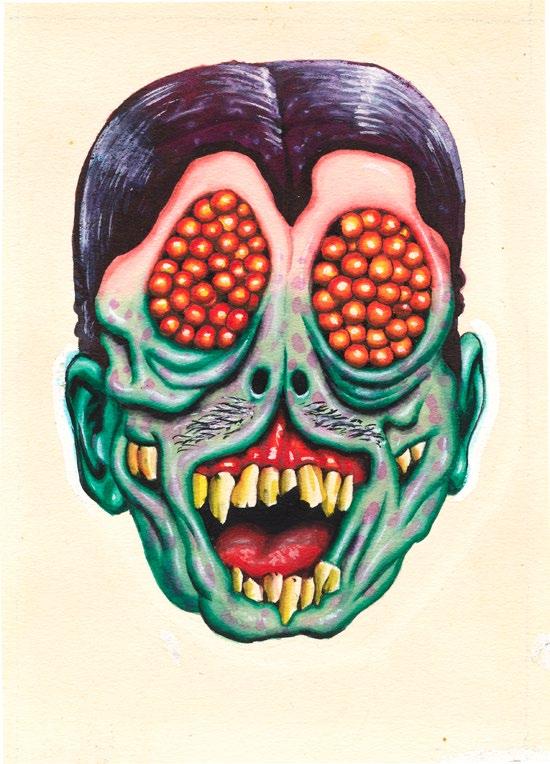

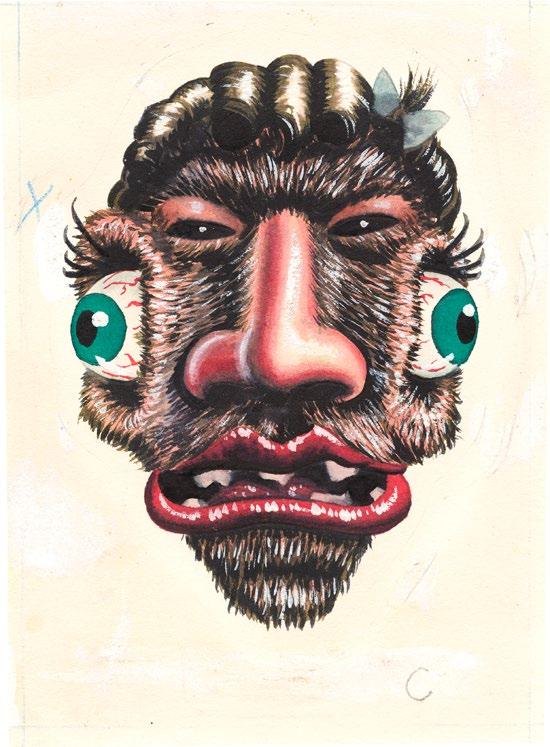

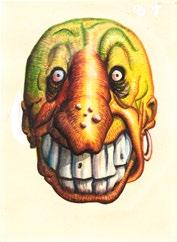

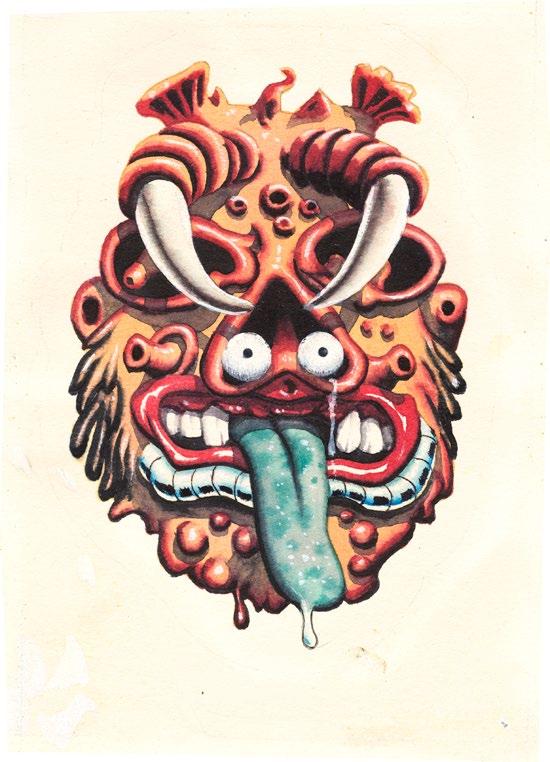

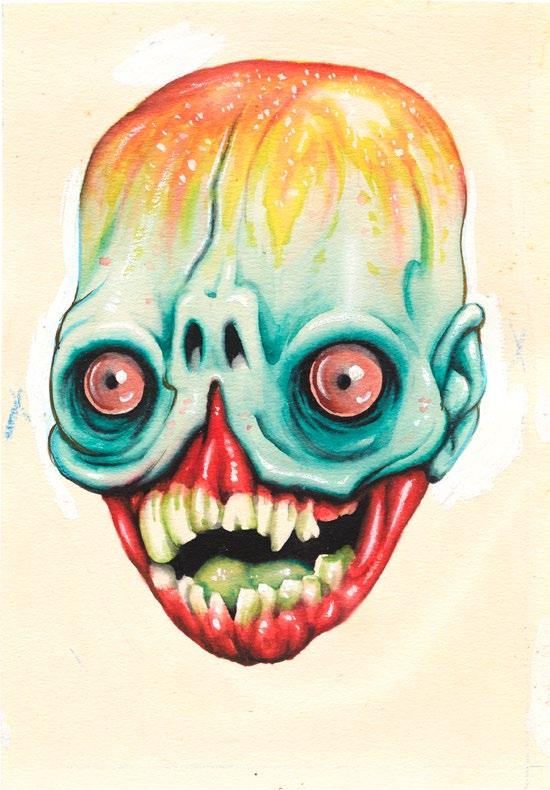

American cartoonist and illustrator Basil Wolverton (1909–1978) is best known for his grotesques and monsters, which have graced Mad magazine, Timely Comics (the proto-Marvel Comics), Stan Lee’s Atlas Comics, and cards and posters for the Topps Company. Wolverton was born in Oregon, where he lived and worked his entire life, choosing to mail his work to publishers rather than relocating to a publishing center like New York. He sold his first cartoon in 1926 and his first comic strip in 1929 to America's Humor Magazine and the Independent Syndicate of New York respectively, but remained unpublished until 1938, when he published a science fiction comic story called Spacehawks in Circus, The Comic Riot. In 1946, Wolverton submitted the winning entry to a contest run by the Li’l Abner comic—to design the character Lena Hyena, the ugliest woman in the world—surpassing about 500,000 other submissions

and gaining a larger audience for his work. He subsequently contributed grotesque faces to Mad magazine, including the famous cover of issue 11 parodying Life Magazine ’s “Beautiful Girl of the Month” feature. In 1966, Wolverton collaborated with Norman Saunders and Wally Wood on the Make Your Own Name Stickers series, and in 1968 he created the Ugly HangUps series of posters, both for the Topps Company. While his career primarily comprised humor and horror comics and cartoons, after becoming a born-again Christian and follower of radio cult Radio Church of God in 1943, Wolverton undertook a project to illustrate every chapter of the Old Testament, which was published from 1958 to 1969. Wolverton’s warped faces and distinctive hatching style influenced future generations of comic artists including R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman, and he was given an honorary Eisner Award in 2000. —IK

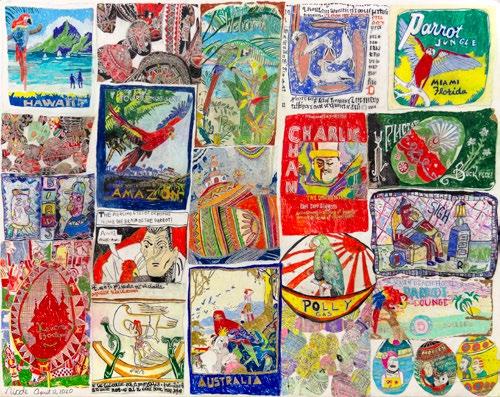

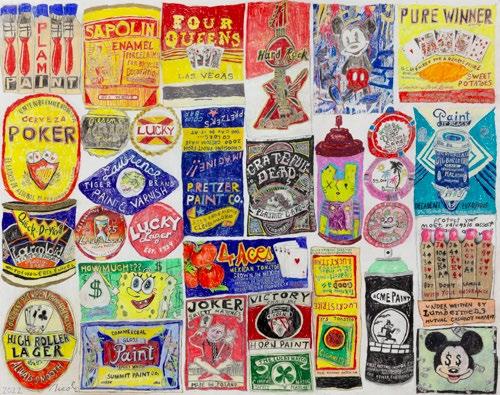

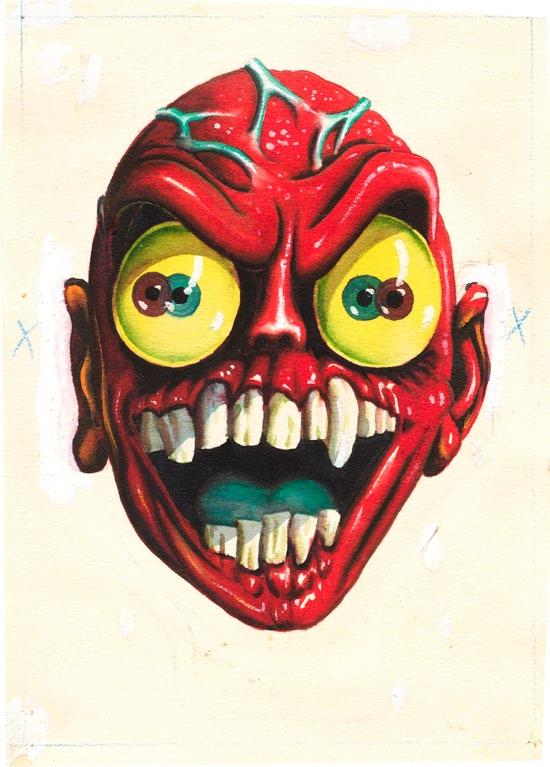

Illustrator Norman Saunders (1907–1989) is best known as a painter of midcentury pulp magazine and novel covers, and for his work with the Topps Company, which produced, most notably, Bazooka Joe and Garbage Pail Kids. Saunders spent his early life in Minnesota, eventually taking art courses at the Federal Schools Inc. of Minneapolis. He began working as an artist for local publisher Fawcett Publication in 1927, primarily creating pulp magazine covers. In 1934, Saunders relocated to New York City, attending classes at the Grand Central School of Art where he studied under well-known American painter and former WWI artist-correspondent Harvey Dunn. Throughout the 1930s and ’40s Saunders created pulp illustrations for magazines that ranged in genre from detective stories to romance, fantasy, horror, Westerns, and more. When pulp magazines began to fall out of fashion, Saunders switched to illustrating pulp book covers, and in 1958 he began to draw for the Topps Company. He contributed to a number of products at Topps including the Mars Attacks cards, Batman cards, Wacky Packages cards, and the Make Your Own Name Stickers for which he collaborated with Basil Wolverton and Wally Wood. —IK

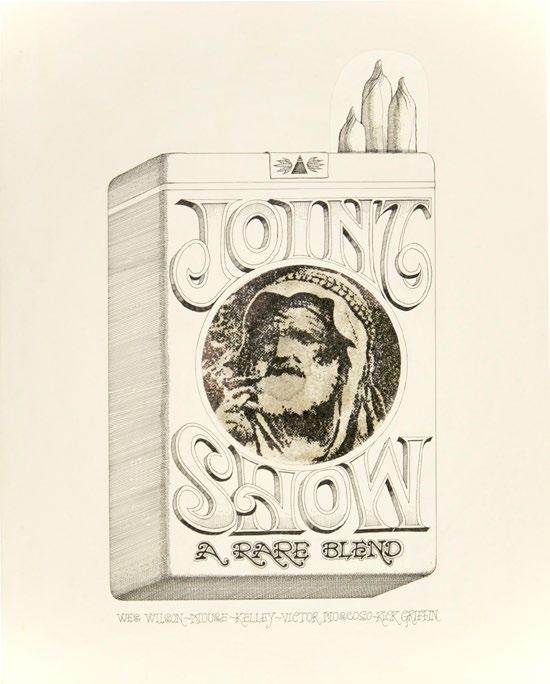

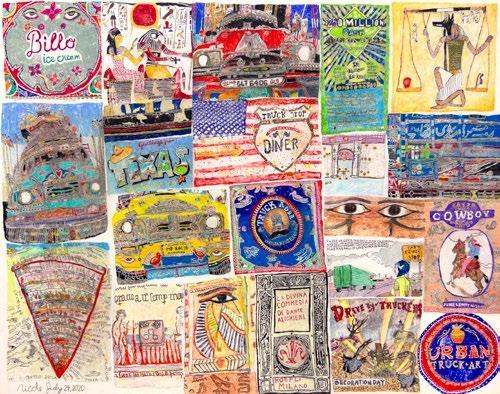

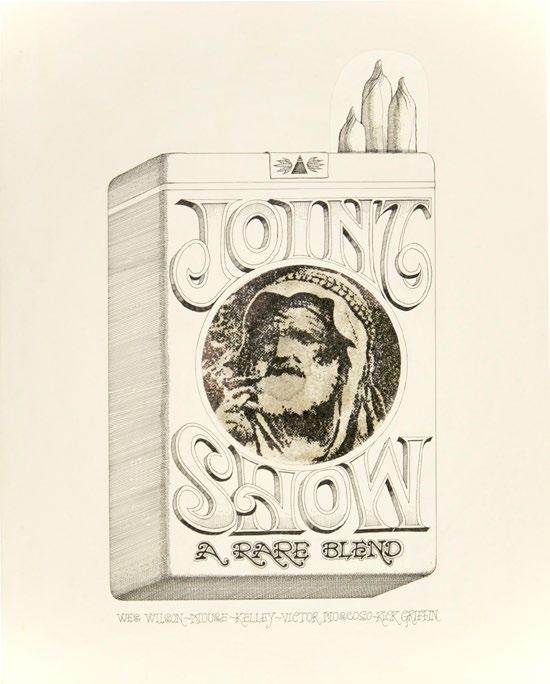

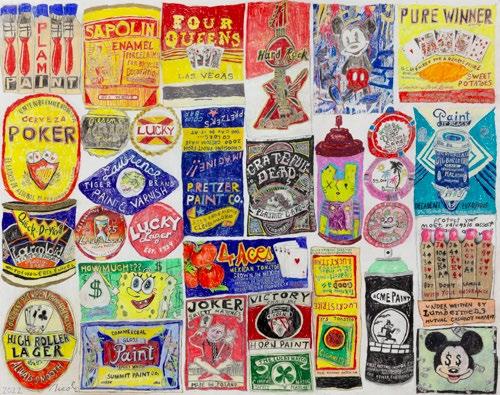

Wally Wood (1927–1981) was an artist immersed in the midcentury comic industry. He is best known for his work on the early issues of Marvel’s Daredevil, for his designs for Mars Attacks, for T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents published by Tower Comics, and for being one of the early contributors to Mad. Wood joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1944, serving for three years during and immediately after World War II before moving to New York, where, with the help of the G.I. Bill, he attended classes in lettering, anatomy, and drawing at Hogarth School for Cartoonists & Illustrators, now the School of Visual Arts (SVA). Entering the New York comic industry in the late 1940s, Wood worked with comic and pulp magazine publishers in a range of genres, including humor, science fiction, and horror, eventually also contributing drawings to men’s magazines like Playboy. Wood began working with the Topps Company in 1962, contributing designs to card series including Mars Attacks, Ugly Stickers, Crazy Little Comics, Nasty Notes, and the Make Your Own Name Stickers alongside fellow artists. —IK PLS. 12–23

Saunders, Basil Wolverton, and Wally Wood

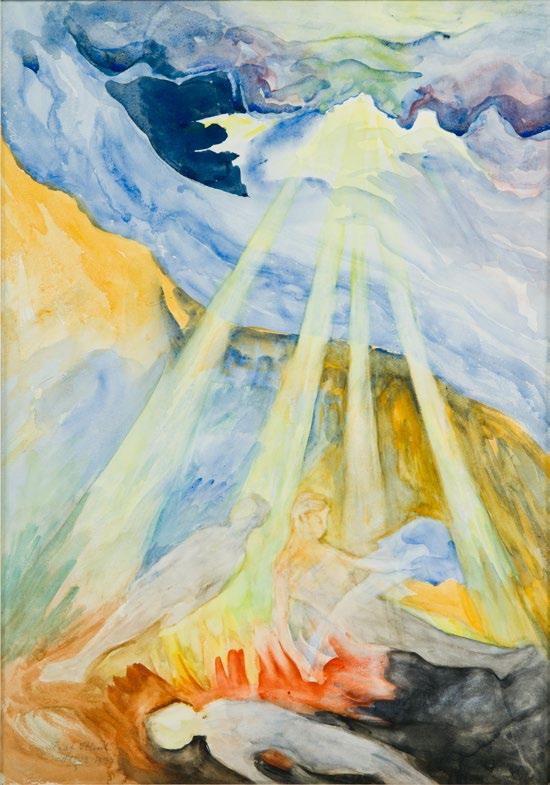

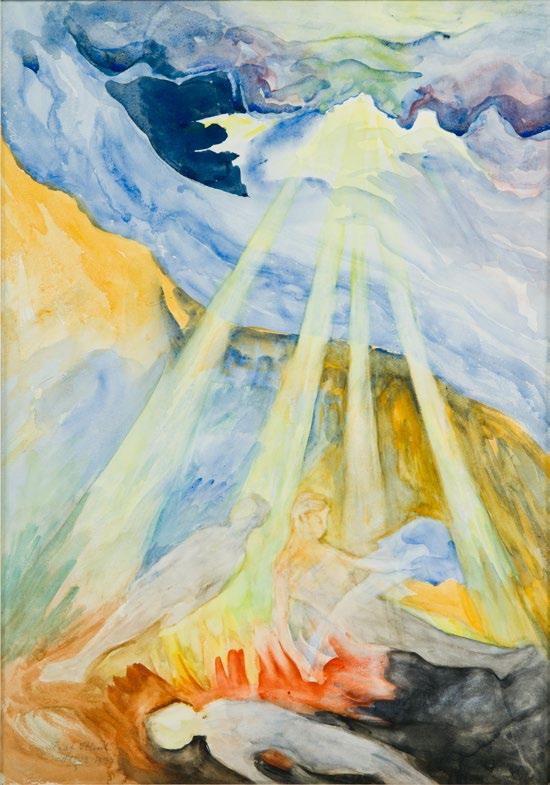

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was a pioneering Swedish artist, considered by some as Europe’s first abstract painter, predating Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian. Born in Stockholm, she graduated from the Royal Academy of Arts in 1887, initially painting landscapes, portraits, and botanical subjects. Her secretive exploration of abstract art began in 1906, influenced by spiritualism and the occult, particularly through her weekly seances with “The Five,” a group of female artists. Af Klint’s work took a dramatic turn after receiving a commission from an entity named Amaliel in 1904, which led to her creation of The Paintings for the Temple series, a collection of 193 works completed between 1906 and 1915. These vibrant, largescale paintings feature a complex lexicon of symbols that include spirals (representing evolution), “U” (denoting the spiritual world), “W” (for matter), and concentric circles (for unity). Despite her groundbreaking work, af Klint remained largely unknown during her lifetime. She stipulated in her will that her work should not be exhibited until twenty years after her death. It was not until the 1986 exhibition The Spiritual in Art in Los Angeles that her contributions began to receive wider recognition.

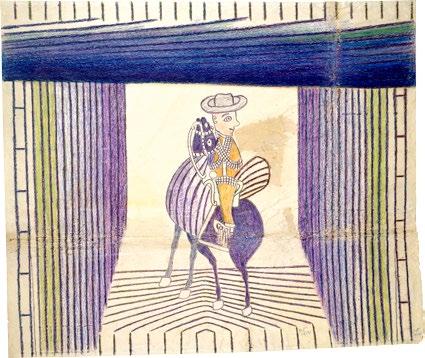

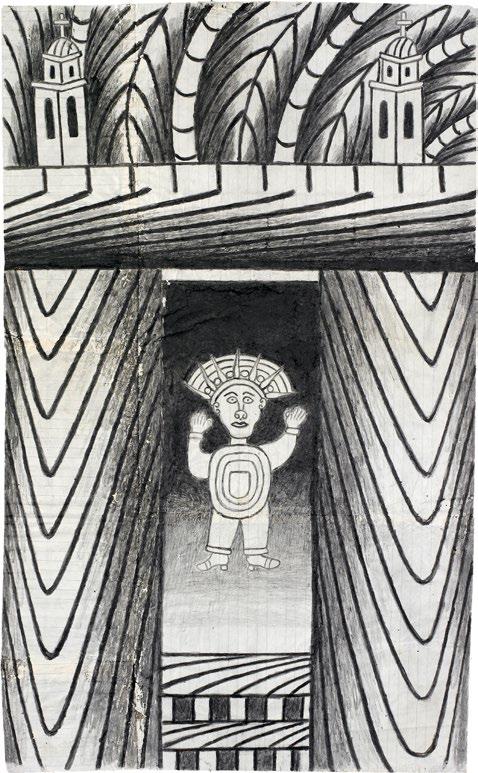

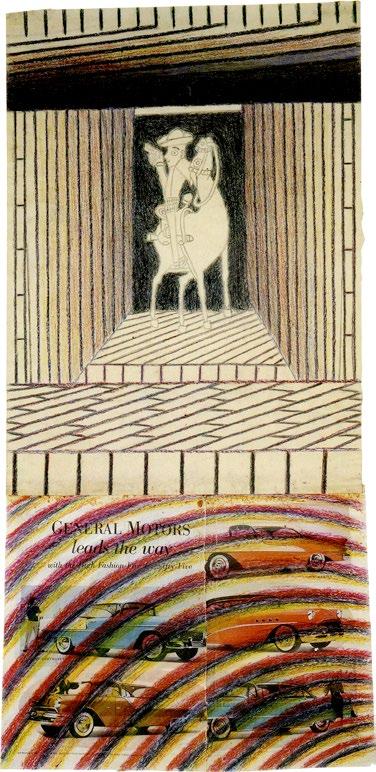

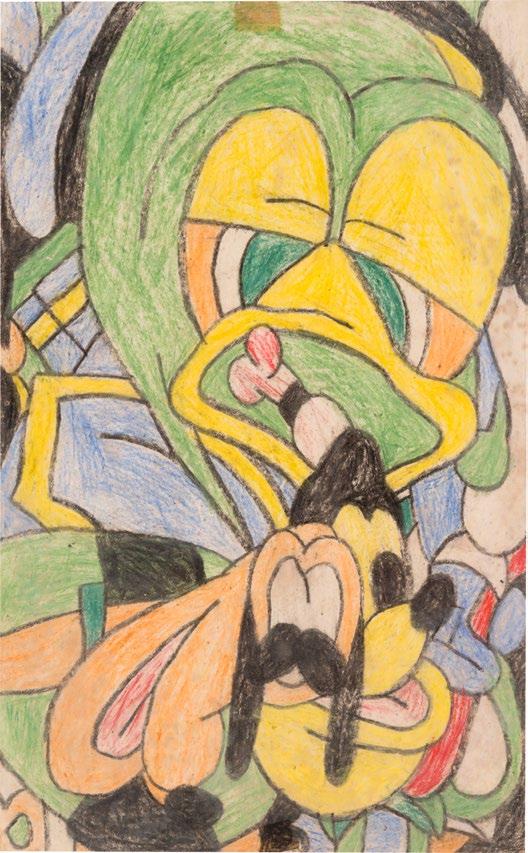

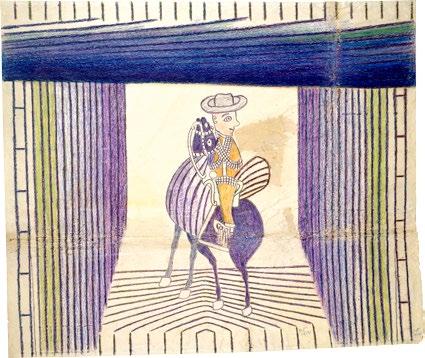

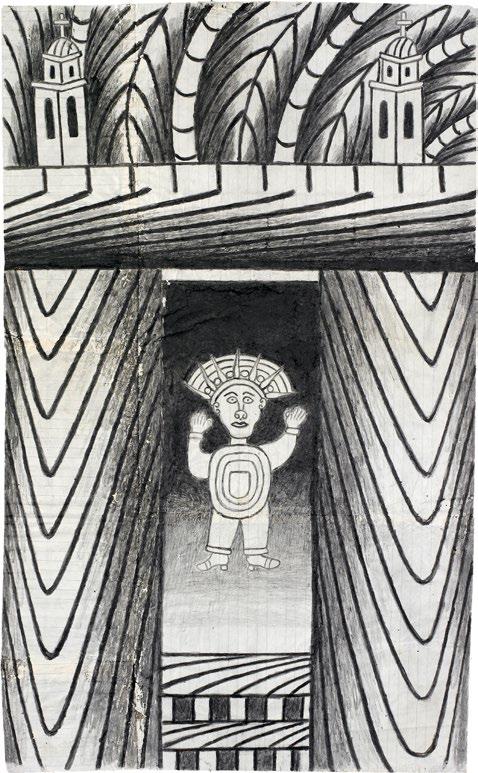

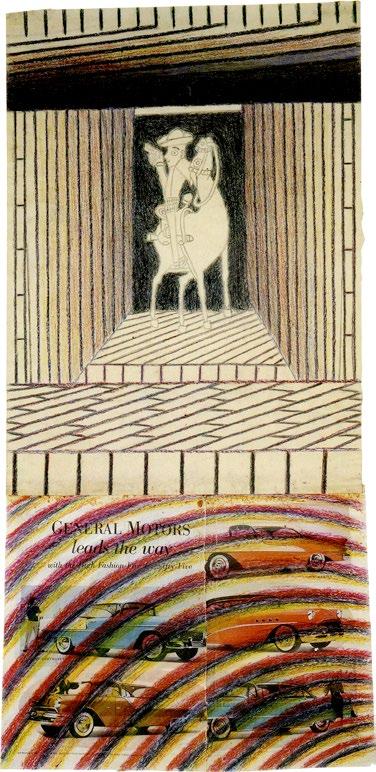

Martín Ramírez (1895–1963) left Mexico for the United States in 1925, hoping to find work to support his wife and four children. Settling in California, Ramírez worked on railroads. The letters he sent home to his family, who remained in Mexico, included drawings in the margins, but the bulk of his extant artistic production is dated later, picking up in 1948. Three years into the Great Depression, Ramírez, along with many of his peers, lost his job and was forced into homelessness. This situation, exacerbated by a breakdown in communication between Ramírez and California authorities, led to his incarceration in 1931, followed by diagnoses of manic depression and, later, catatonic schizophrenia. Ramírez was transferred between several hospitals in Northern California, finally landing in DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, California, in 1948. During this time, Ramírez began to create art with hospital supplies, including sheets of operating paper, masticated newspaper, paper bags, and mashed potatoes used to paste multiple sheets of paper together. At DeWitt State Hospital, psychologist Tarmo Pasto began saving and archiving Ramírez’s work. The artist created about 300 drawings between 1948 and his death in 1963, usually pulling from his past experiences as subject matter. His caballeros and churches take their appearances from those in Ramírez’s home state of Jalisco, Mexico, while trains and mountains reference his time as a railroad worker. —IK

PL. 25

Untitled (Caballero), c. 1950

Crayon, graphite, and collage on paper

49 x 44 1/2 inches (124.5 x 113 cm)

PL. 26

Untitled (Horse and Rider), 1954

Pencil, color pencil, collage, and crayon on paper

26 1/8 x 30 1/8 inches (66.3 x 76.5 cm)

PL. 27

Untitled (Trains and Tunnels), 1954

Pencil, color pencil, crayon, and watercolor on paper

36 x 41 1/4 inches (91.4 x 104.8 cm)

PL. 28

Untitled (Horse and Rider), 1954

Gouache, color pencil, and graphite on paper

33 1/8 x 23 15/16 inches (84 x 60.8 cm)

PL. 29

Untitled (Aztec), c. 1960–63

Gouache and graphite on pieced paper

24 1/2 x 15 inches (62.2 x 38.1 cm)

PL. 30

Untitled (Horse and Rider), c. 1950

Color pencil, crayon, and collage on paper

37 x 17 1/2 inches (94 x 44.4 cm)

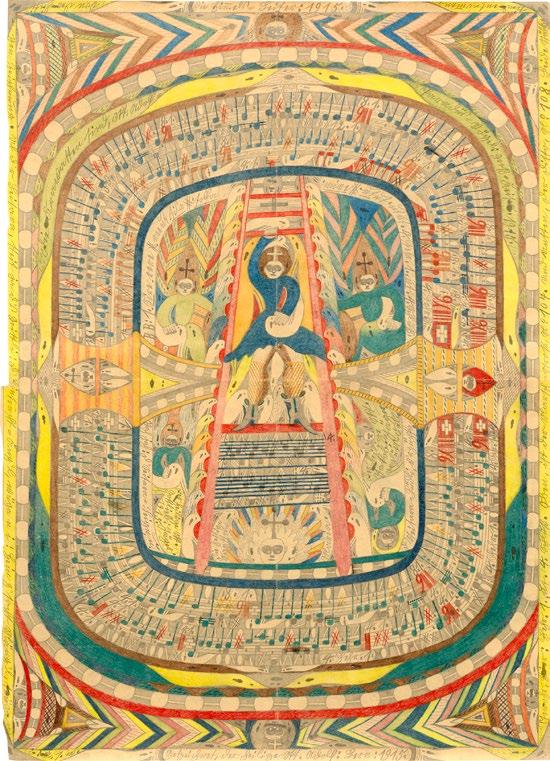

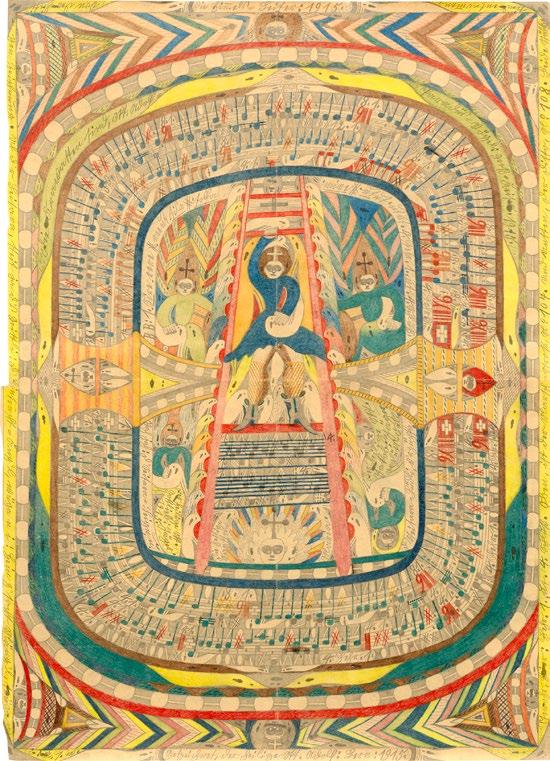

Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930) was a Swiss artist who began drawing in 1904 during his incarceration at the Waldau Clinic, a psychiatric facility in Bern. While at Waldau (1895 until his death in 1930), Wölfli created a series of over 25,000 autobiographical drawings and collages in addition to a collection of smaller works that he called “bread art” because he sold them in order to purchase art supplies. In the artist’s forty-five volumes of work, he utilized decorative borders, saturated color, poetry, and musical composition to recount a fanciful version of his life. Wölfli was orphaned at ten, after which he entered the Swiss foster system. Indentured as a farm laborer while still a child, he continued to work on farms while in the foster system, finally able to leave when he was eighteen. He became a handyman upon moving to Bern, where he was incarcerated twice for child abuse before being institutionalized at Waldau for a similar crime at age thirty-five. At Waldau, Wölfli exhibited violent behavior that subsided somewhat when he drew. Interested in the effect that artmaking had on Wölfli, psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler, who worked at the facility, wrote a study based on Wölfli, entitled “Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler” (A mentally ill person as artist), which had the added effect of documenting and sharing the artist’s work. —IK

PL. 31

Genanttes Heimwesen, Probsten=Loch Blatt aus Heft N° 13, 1915

Graphite and color pencil on newsprint 28

PL. 32

Blatt aus Heft no. 13, c. 1916

Graphite and color pencil on paper

39 x 28 inches (99 x 71.1 cm)

PL. 33

Die Himmels Leiter, 1915

Graphite and color pencil on paper

39 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches (99.7 x 71.7 cm)

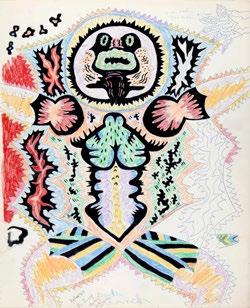

Yuichiro Ukai (1995–) creates dense compositions layering yōkai, animals and insects, characters from anime and manga, characters from Western cartoons, skeletons, dinosaurs, and imagery from Japanese epics into dense tapestries of color and pattern on the page. Often made on large sheets of brown paper, these drawings frequently repeat the same forms over and over, even across multiple panels, alluding to a narrative that travels right to left across several drawings. After graduating high school in 2014, Ukai joined Atelier Yamanami in Shiga Prefecture, an art workshop and living facility founded in 1986 to provide space, resources, and training to artists with mental and physical disabilities. The artist splits his time between Atelier Yamanami and his work as a custodian. Ukai’s drawings were first exhibited in 2018 at Harvard University Asia Center in Massachusetts, and in 2020 one of his works was acquired by the American Folk Art Museum. —IK

PL. 34

Untitled, 2022

Marker, ink, and color pencil on cardboard

28 3/4 x 32 1/2 inches (73 x 82.5 cm)

PL. 35

Untitled (No. 61), 2023

Color pencil, marker, oil pastel, and ink on cardboard

29 x 32 1/2 inches (73.6 x 82.5 cm)

PL. 36

Untitled (No. 62), 2023

Color pencil, marker, oil pastel, and ink on cardboard

29 x 32 1/2 inches (73.6 x 82.5 cm)

PL. 37

Untitled (No. 60), 2023

Color pencil, marker, oil pastel, and ink on cardboard

29 x 32 1/2 inches (73.6 x 82.5 cm)

Though she had been creating them since 1990, Helen Rae’s (1938–2021) vibrant, stylish color pencil and graphite reimaginings of fashion spreads from the pages of magazines like Vogue were not exhibited until 2015. Rae began drawing in 1990, when her mother enrolled her in First Street Gallery and Art Center, a Californiabased art establishment for adults with developmental disabilities. Drawing continuously for the rest of her life, Rae created a body of work that reinterprets the quiet, sleek images of the fashion world with warped, emotive forms, flattened spaces, and patches of bold pattern. Following her first solo exhibition at The Good Luck Gallery in 2015, which sold out the night it opened, interest in Rae’s work greatly increased. Her drawings have since appeared in exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, and Paris as well as in Scotland, Belgium, and Japan. —IK

PL. 38

Untitled (June 7, 2019), 2019

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 39

Untitled (January 2, 2015), 2015

Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

PL. 40

Untitled (December 13, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 1/4 x 18 1/4 inches (61.6 x 46.3 cm)

PL. 41

Untitled (July 9, 2010), 2010

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 42

Untitled (March 6, 2019), 2019

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 43

Untitled (June 25, 2019), 2019

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 44

Untitled (February 2, 2010), 2010

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 45

Untitled (July 6, 2015), 2015 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 46

Untitled (January 18, 2008), 2008 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 47

Untitled (March 4, 2013), 2013 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 48

Untitled (June 29, 2009), 2009

Oil pastel, color pencil, and graphite on paper

23 5/8 x 17 3/4 inches (60 x 45 cm)

PL. 49

Untitled (June 25, 2012), 2012

Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

PL. 50

Untitled (March 4, 2020), 2020

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 1/4 x 18 inches (61.6 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 51

Untitled (December 19, 2013), 2013 Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

PL. 52

Untitled (March 6, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 53

Untitled (June 28, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 54

Untitled (December 6, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 55

Untitled (January 23, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 56

Untitled (May 16, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 57

Untitled (July 12, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 58

Untitled (October 25, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 59

Untitled (June 19, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 60

Untitled (August 22, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 61

Untitled (October 11, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 62

Untitled (March 10, 2010), 2010

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 1/4 x 18 inches (61.6 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 63

Untitled (April 28, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 64

Untitled (July 13, 2007), 2007

Mixed media on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 65

Untitled (January 19, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 66

Untitled (October 22, 2014), 2014

Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

PL. 67

Untitled (December 22, 2017), 2017

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 68

Untitled (July 22, 2009), 2009

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 69

Untitled (March 1, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 70

Untitled (May 24, 2018), 2018

Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 71

Untitled (July 29, 2014), 2014 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 72

Untitled (December 15, 2014), 2014

Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

PL. 73

Untitled (January 24, 2020), 2020 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 1/4 x 18 1/4 inches (61.6 x 46.3 cm)

PL. 74

Untitled (December 21, 2016), 2016 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 75

Untitled (January 30, 2014), 2014 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 76

Untitled (November 18, 2014), 2014 Color pencil on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 77

Untitled (April 2, 2010), 2010 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 78

Untitled (July 21, 2008), 2008 Color pencil on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 79

Untitled (August 8, 2019), 2019 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 80

Untitled (August 8, 2017), 2017 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 81

Untitled (April 11, 2019), 2019 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 82

Untitled (January 11, 2013), 2013 Color pencil and graphite on paper 24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 83

Untitled (March 27, 2015), 2015 Oil pastels, color pencil, and graphite on paper

23 5/8 x 17 3/4 inches (60 x 45 cm)

PL. 84

Untitled (February 13, 2020), 2020 Color pencil and graphite on paper

24 x 18 inches (61 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 85

Untitled (December 3, 2014), 2014 Color pencil and graphite on paper

23 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches (59.7 x 44.4 cm)

Top (from left): PLS. 41, 42

Bottom (from left): PLS. 43, 44

Top (from left): PLS. 54, 55, 56

Middle (from left): PLS. 57, 58, 59

Bottom (from left): PLS. 60, 61, 62

Top (from left): PLS. 45, 46, 47

Middle (from left): PLS. 48, 49, 50

Bottom (from left): PLS. 51, 52, 53

Top (from left): PLS. 64, 65, 66

Middle (from left): PLS. 67, 68, 69

Bottom (from left): PLS. 70, 71, 72

Top (from left): PLS. 82, 83

Bottom (from left): PLS. 84, 85

Top (from left): PLS. 73, 74, 75

Middle (from left): PLS. 76, 77, 78

Bottom (from left): PLS. 79, 80, 81

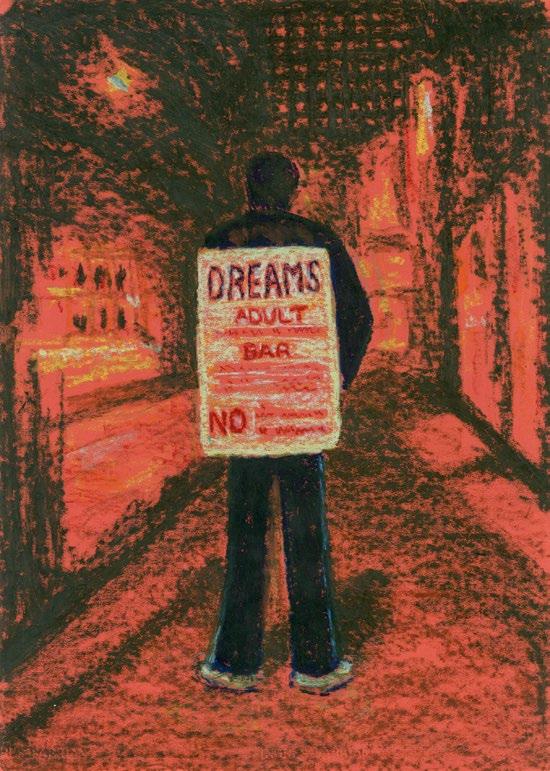

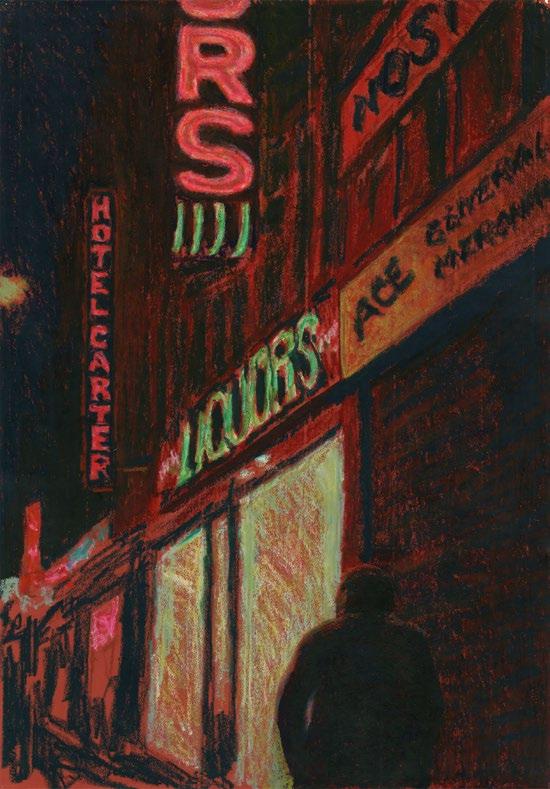

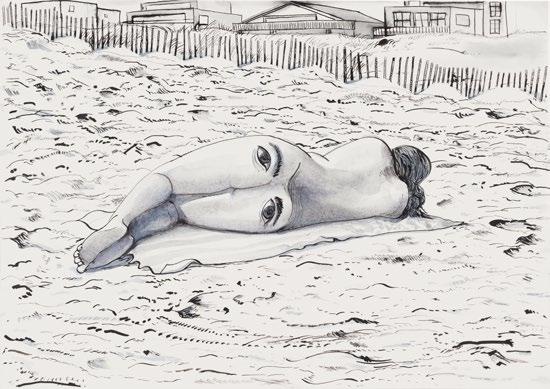

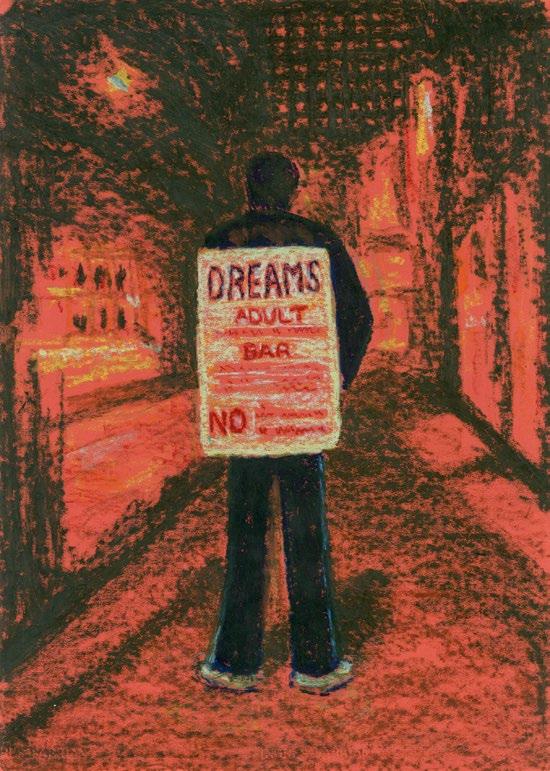

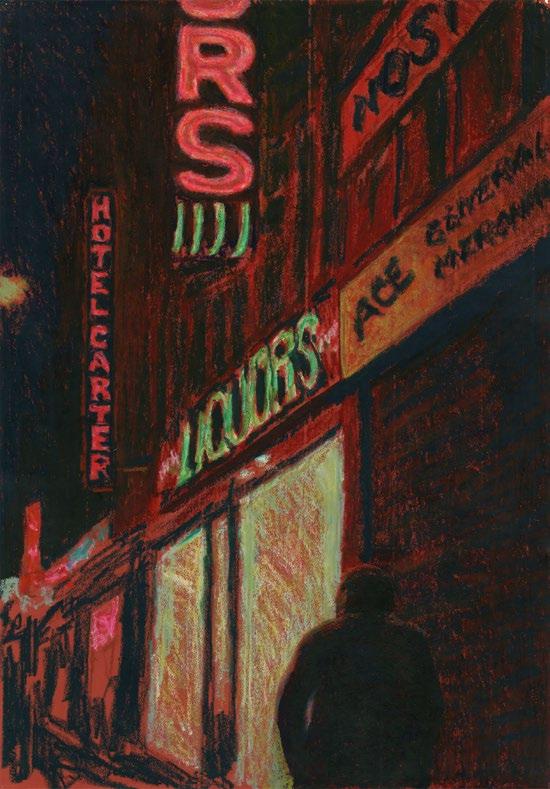

The Chicago-born artist Jane Dickson (1952–) is known for her evocative paintings, drawings, and prints that delve into the psychogeography of American culture. Dickson's artistic journey was shaped by late-1970s punk and alternative counterculture in New York, where she was active in artist collectives like Fashion Moda and Collaborative Projects Inc. (Colab), which staged the landmark Real Estate Show and The Times Square Show in 1980. In 1978, Dickson responded to a wanted ad in The New York Times for an “artist…willing to learn computers,” which led to her employment as the nighttime programmer of Spectacolor, the first electronic billboard at One Times Square. She used the opportunity to pioneer some of the first widely-seen digital art and animations of the time as well as to curate projects by her friends and colleagues, including Jenny Holzer, Keith Haring, and David Hammons. Dickson’s cinematic and fluorescent depictions of Times Square—where she lived in a loft on 43rd Street for nearly three decades—feature motels, strip clubs, sex shops, and late-night diners irradiated by the surrounding neon signs and colossal marquees, offering a powerful and penetrating commentary on American values and social strata.

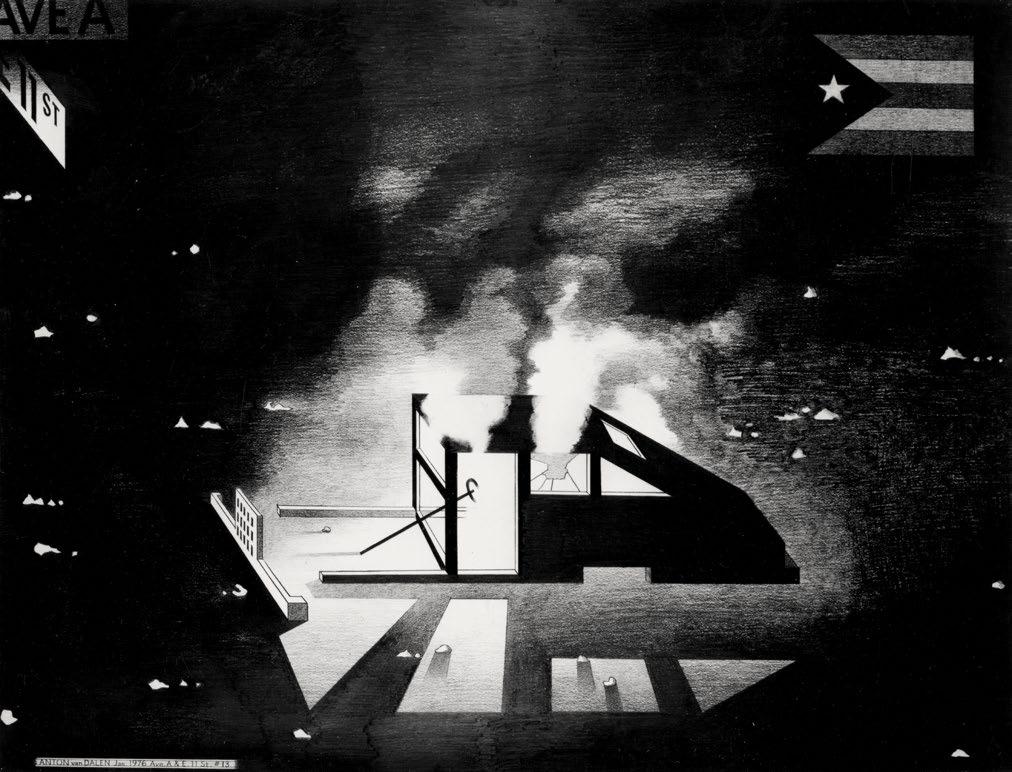

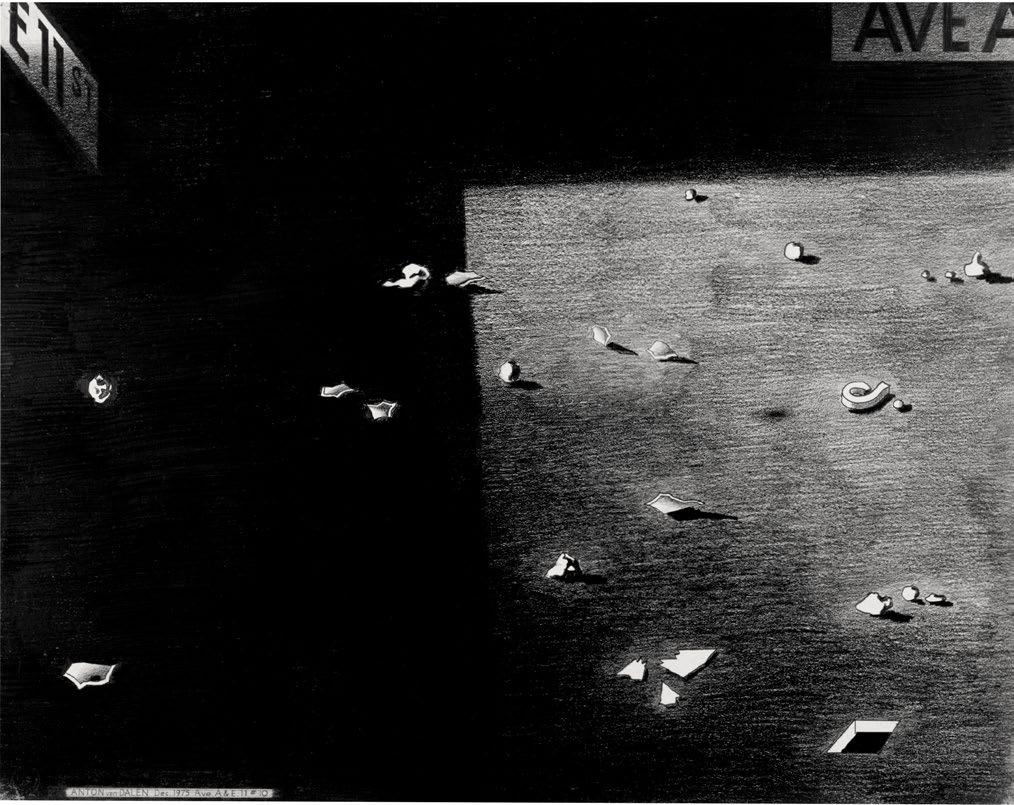

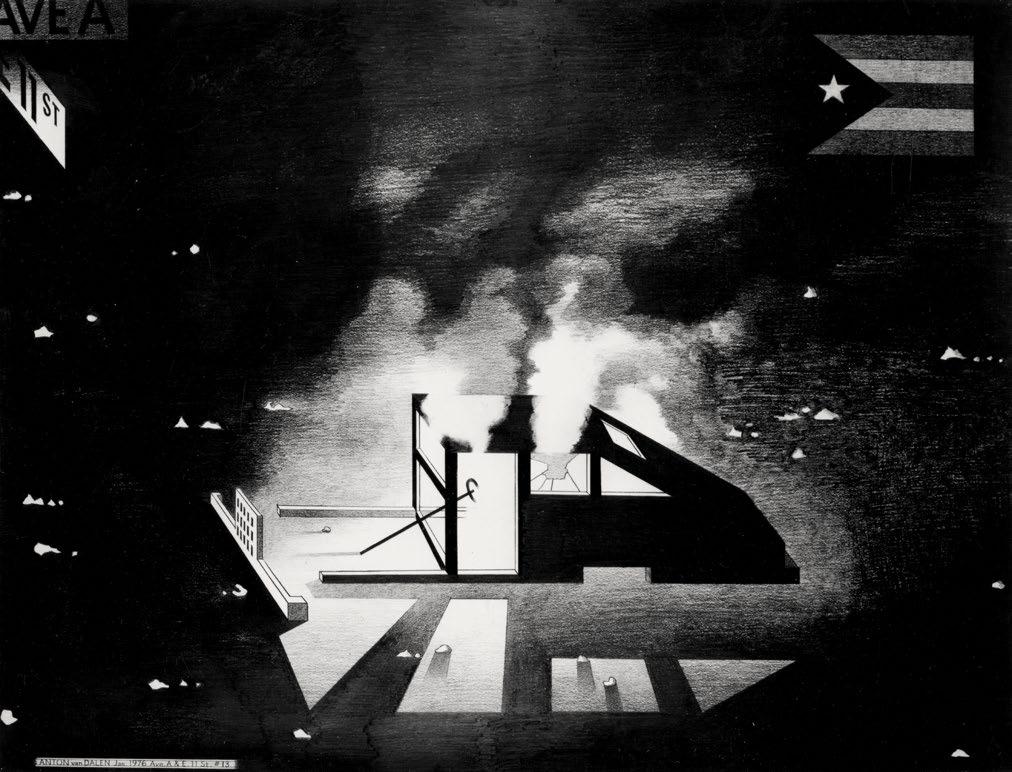

Anton van Dalen’s (1945–2024) career spanned decades and continents and was marked by a deep engagement with urban culture and activism. Born in the Netherlands, van Dalen studied at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, where he was influenced by the political upheavals of the late 1960s and developed a keen interest in social issues and artistic expression as means of protest. In 1969, van Dalen moved to New York City and became immersed in the Lower East Side’s vibrant avant-garde art movement. His early works often incorporated themes of urban decay, identity, and community, reflecting the gritty reality of the city amidst social and political turmoil. His distinctive style merges bold contrasts, intricate patterns, and symbolic imagery drawn from mythology, folklore, and urban life. Central to his work is a fascination with the human psyche and the intersections of culture, history, and personal identity. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, van Dalen’s art evolved alongside his activism. He cofounded Collaborative Projects Inc. (Colab), a pioneering artist collective that challenged traditional art practices and advocated for social change. Van Dalen’s contributions to Colab's groundbreaking exhibitions, such as The Times Square Show, held in a shuttered massage parlor in 1980, cemented his reputation as a boundary-pushing artist unafraid to confront societal norms. —RD

PL. 89

Alpha y Omega with Dog, 1977

Graphite on paper

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm)

PL. 90

Abandoned Car with Dog and TV, 1977

Graphite on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.4 x 73.7 cm)

PL. 91

Night Synagogue and Stripped Car, 1976

Graphite on paper

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

PL. 92

Car, Jesus Saves and P.R. Flag, 1982

Graphite on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.4 x 73.7 cm)

PL. 93

Street Debris on Sidewalk, 1975

Graphite on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.42 x 73.66 cm)

PL. 94

Street Debris, In and Out of Shadow, 1975

Graphite on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.42 x 73.66 cm)

PL. 95

Ave. A & E. 11 St #13, 1976

Graphite on paper

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

Above (from top): PLS. 90, 91

Above (from top): PLS. 92, 93

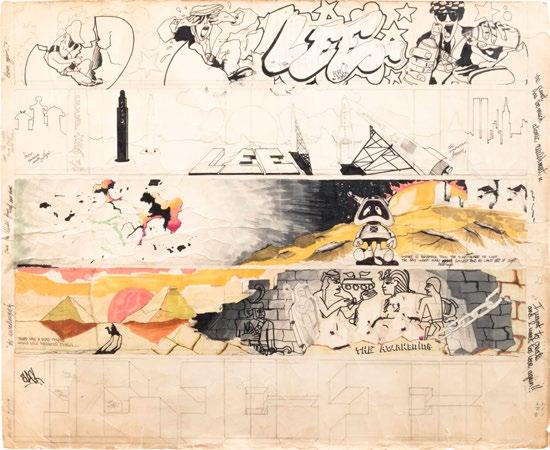

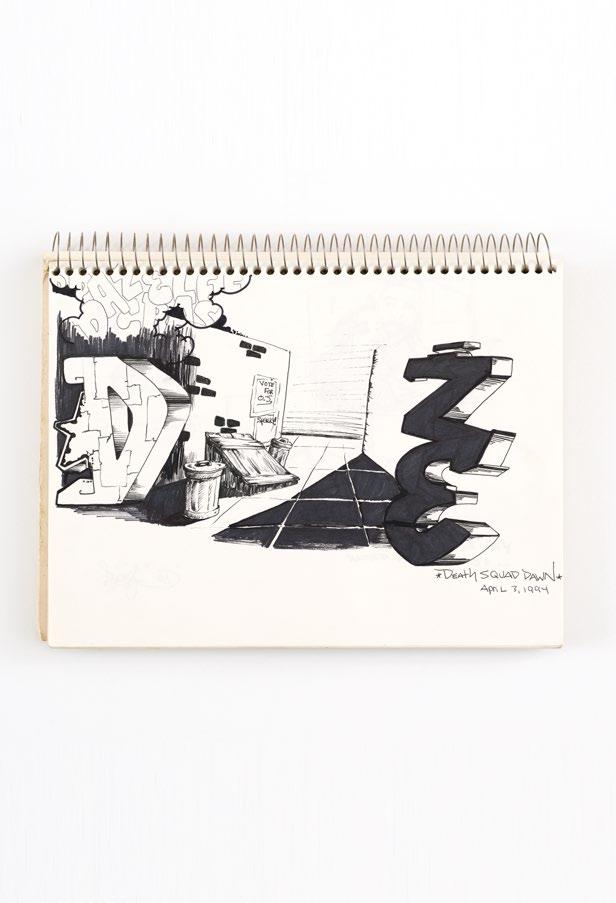

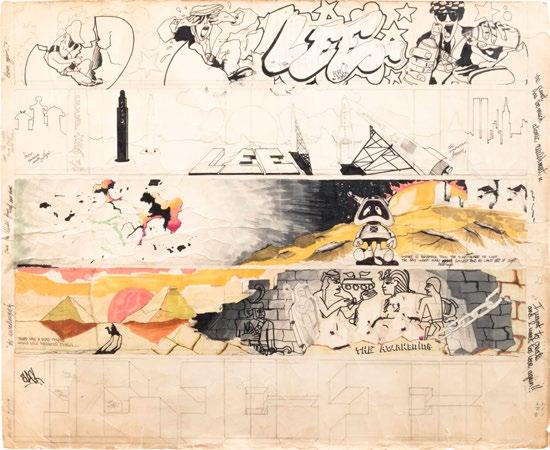

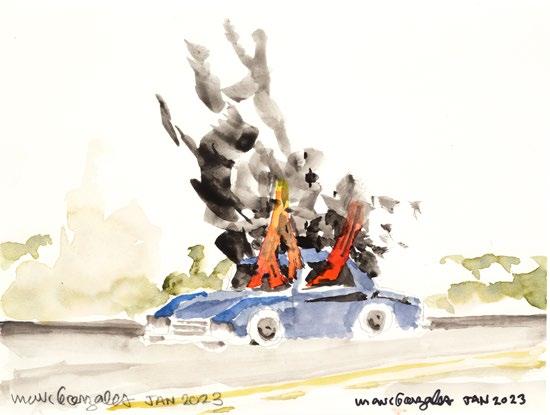

Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, Lee Quiñones (1960–) grew up on New York’s Lower East Side at the dawn of the New York graffiti movement and began painting subway cars at thirteen years old. By the end of the 1970s, he had painted over a hundred subway cars, including covering an entire ten-car train with his crew the Fabulous 5ive, and had gained a reputation as one of the pioneers of New York graffiti writing. Quiñones was also one of the first artists to bring subway writing out of the subway: he created a handball court mural, Howard the Duck, in 1978 and began making work with spray paint on canvas around the same time. By 1980, Quiñones had shown his spray-painted canvases at home and abroad, most notably in the pivotal Times Square Show. This collaborative, communitybased stepping stone in the early careers of over a hundred artists also included the work of JeanMichel Basquiat, Keith Haring, David Hammons, and Kiki Smith, among many others. Quiñones was interested in introducing narrative and characters into his paintings, adding to the artist’s name that typically made up the bulk of a subway writer’s compositions.

“Lee,” the artist’s middle name and moniker of choice, is short and easy to write quickly, which allowed Quiñones to both cover subway cars quickly and devote more time to the other elements in his pieces. —IK

PL. 96

Heart Break, 1978

Alcohol marker and ink on Strathmore drawing pad paper

12 x 18 inches (30.5 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 97

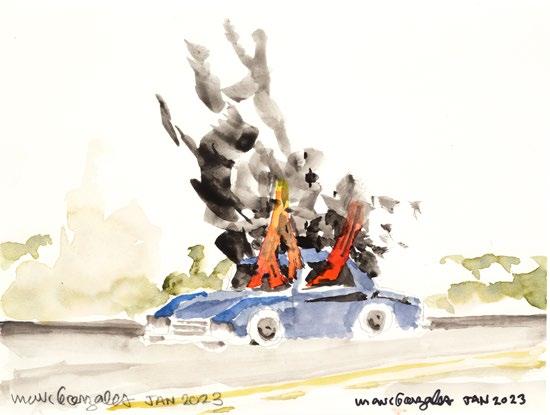

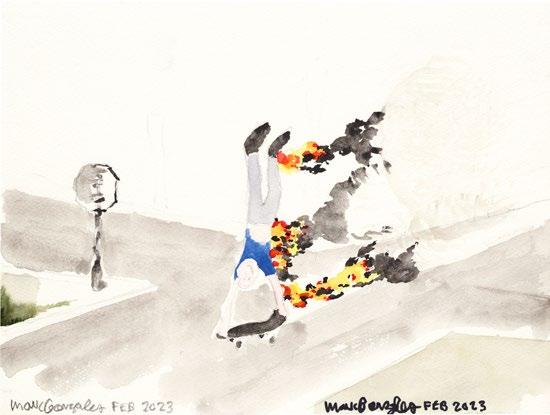

Hot Rod from Hell (The Fabulous 5), 1977

Alcohol marker and ink on Strathmore drawing pad paper

12 x 18 inches (30.5 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 98

Hagar the Horrible, 1978

Alcohol marker and spray paint on Strathmore drawing pad paper

12 x 18 inches (30.5 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 99

War of the Worlds, 1976

Alcohol marker and Buffalo water marker on pad paper

13 3/4 x 43 3/4 inches (34.9 x 111.1 cm)

PL. 100

Silent Thunder (Whole Car), 1984

Alcohol marker and pencil on paper

4 1/4 x 28 1/2 inches (10.8 x 72.4 cm)

PL. 101

Lee Has Quit, 1977

Alcohol marker and Buffalo water marker on card stock

9 x 22 inches (55.9 x 22.9 cm)

PL. 102

One Million B.C., 1977

Alcohol marker on folder card stock

8 3/4 x 29 1/2 inches (22.2 x 74.9 cm)

PL. 103

Subway Car Montage, 1981

Alcohol marker and pencil on paper

26 5/16 x 32 1/4 x 1 1/2 inches (66.8 x 81.9 x 3.8 cm)

PL. 104

Subway Car Montage, Study #2, 1980–1983

Alcohol marker, pencil, ink on illustration board

22 1/2 x 28 1/2 inches (57.2 x 72.4 cm)

PL. 105

Battlestar Galactica, 1979

Alcohol marker on Strathmore drawing pad paper

21 1/4 x 28 inches (54 x 71.1 cm)

PL. 106

Fabulous Ave, 1977

Alcohol marker and ink on Bristol paper

11 3/4 x 18 inches (45.7 x 29.8 cm)

Above (from top): PLS. 97, 98

Above (from top): PLS. 99, 100, 101, 102

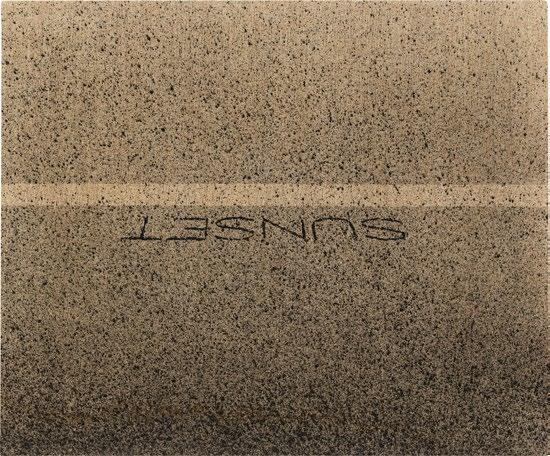

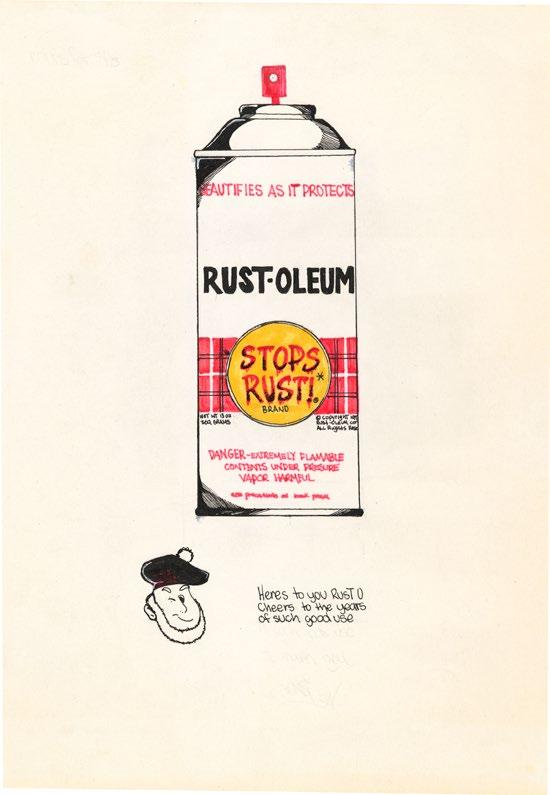

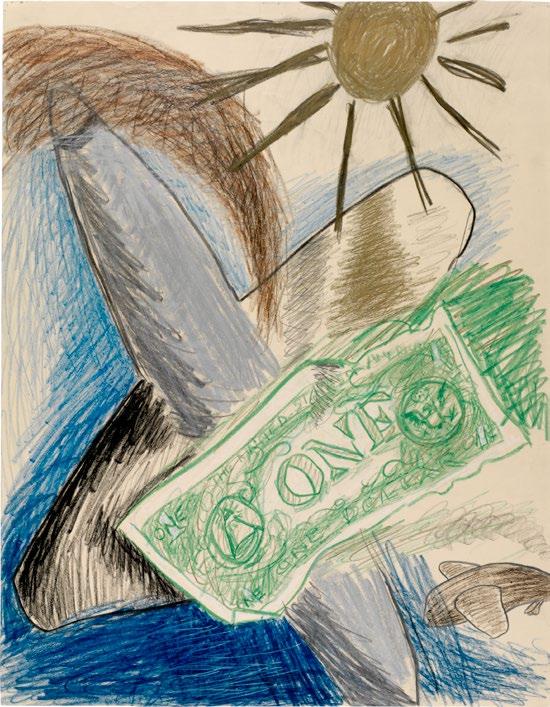

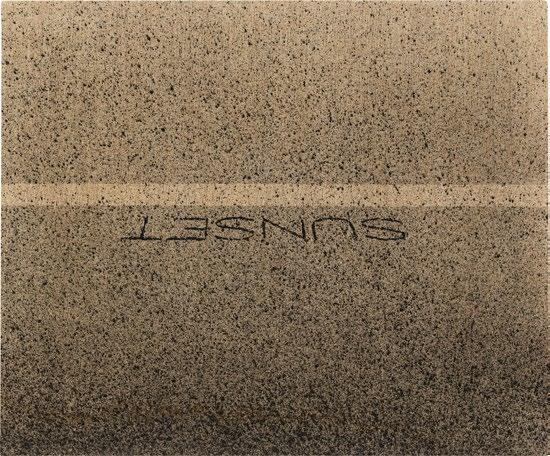

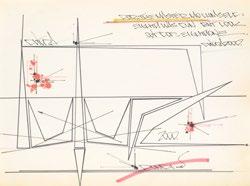

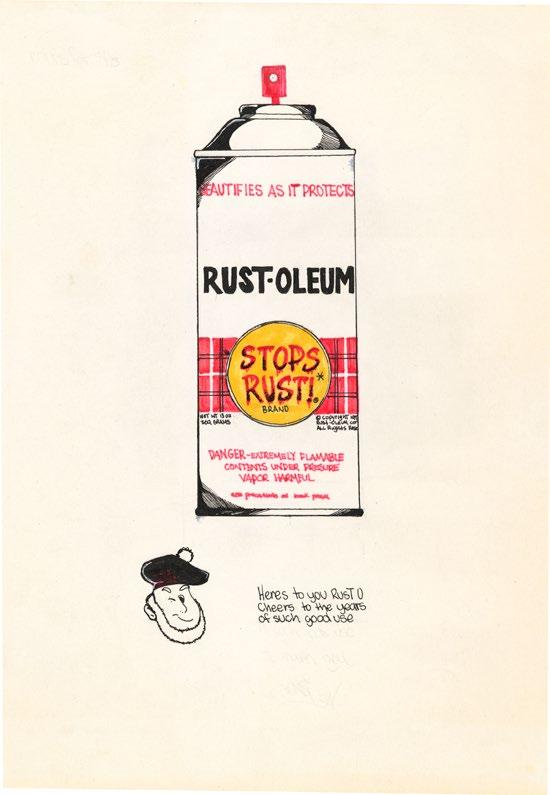

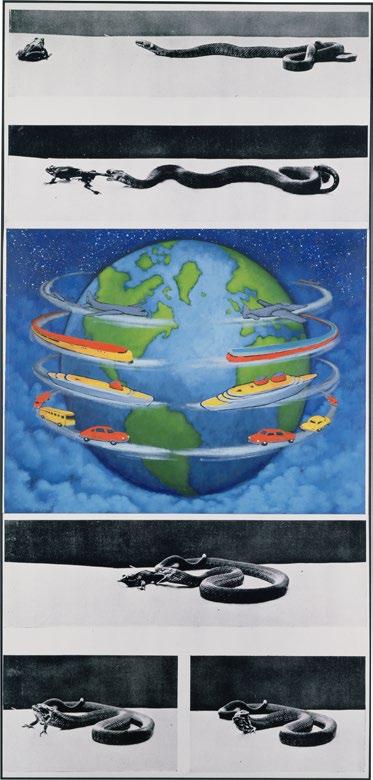

The career of artist Ed Ruscha (1937–) spans six decades and is characterized by work that deftly presents the mundane, from places to phrases, for deeper consideration. As a student at Chouinard Art Institute, Ruscha soaked in the influence of earlier movements like Dadaism and Surrealism, letting them inform his own recontextualization of the everyday. After graduating in 1960, he worked for advertising agencies, where communication, graphics, text, typography, and meaning were all part of his daily consideration. Much of Ruscha’s work is text-based, rendering phrases and even his own name with a directness that forces the viewer to understand the artwork as an object as well as the meaning, or lack thereof, built into common vernacular. Ruscha’s career has encompassed drawing, painting, photography, art books, prints, film, and installation. In these works he has reflected on logos, the gasoline stations of Route 66, mountains, tires, and the American flag. The artist lives and works in Los Angeles. —IK

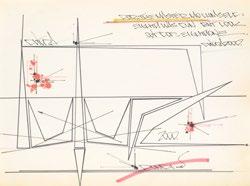

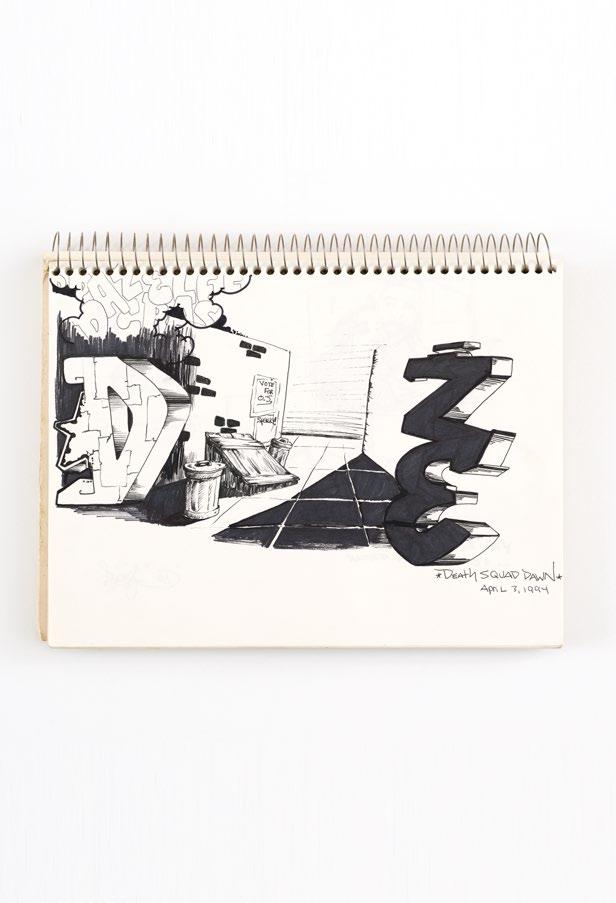

Born Leonard Hilton McGurr (1955–) in New York City, FUTURA 2000 (also known as FUTURA) is a trailblazer in graffiti art, emerging as a prominent figure in the late 1970s. His early work was marked by a fascination with abstraction and futurism, enduring elements that would become central to his artistic identity. A pivotal moment in his career came in 1980 when he, along with graffiti artist DONDI, visited a Bronx train yard to bomb the side of an entire train car in a piece that he titled Break. This iconic mural, characterized by its dynamic and non-representational forms, set a new standard in graffiti art by focusing on fluid shapes and abstract compositions, unlike conventional text-based graffiti. In the early 1980s, FUTURA began exhibiting in galleries such as Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery and Tony Shafrazi Gallery, alongside contemporaries that included Keith Haring, RAMMELLZEE, DONDI, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. He also expanded into music, designing the iconic cover for The Clash’s single “This is Radio Clash” and performing live art during the band’s Combat Rock tour. As street culture evolved in the 1990s, FUTURA embraced commercial collaborations with brands like Supreme and Louis Vuitton, and he continues today as a dynamic force in both the art and fashion worlds. —RD

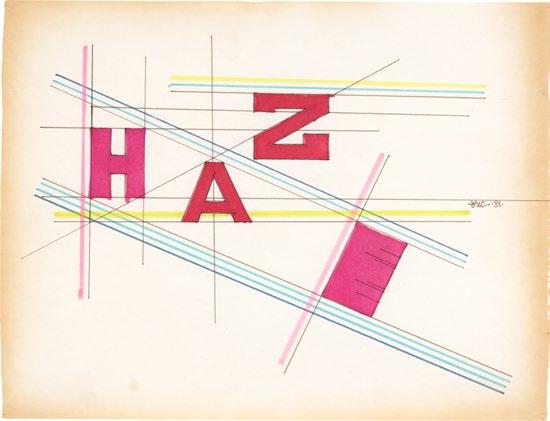

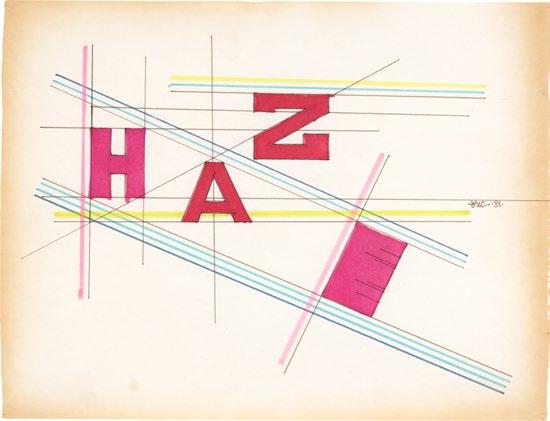

Born and raised in New York City, Eric Haze (1961–) has worked across the mediums of graffiti, street art, and graphic design for over forty years, playing a crucial role in defining the visual language of hip-hop during its formative years. Haze first exhibited his work in 1974 as part of the pioneering graffiti collective The Soul Artists, of which he was a founding member. He went on to show alongside Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat in the early 1980s. Transitioning from fine art to commercial art in the mid-1980s, Haze became a leading graphic designer for the burgeoning hip-hop movement, crafting nowcelebrated logos—including the iconic emblems for Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys—and album covers that defined the aesthetic of an era. —RD

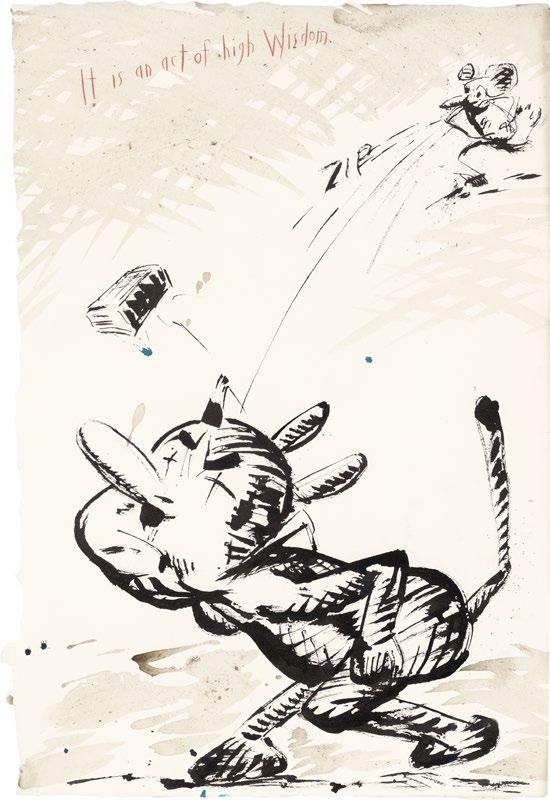

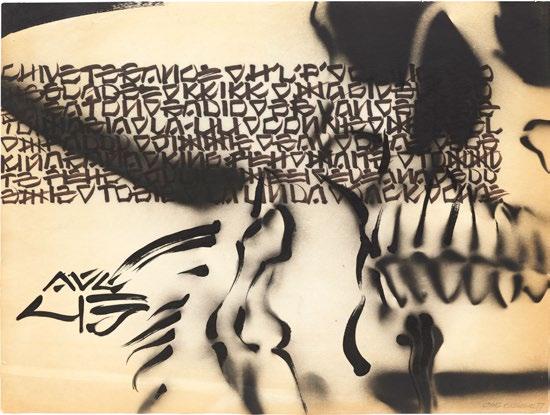

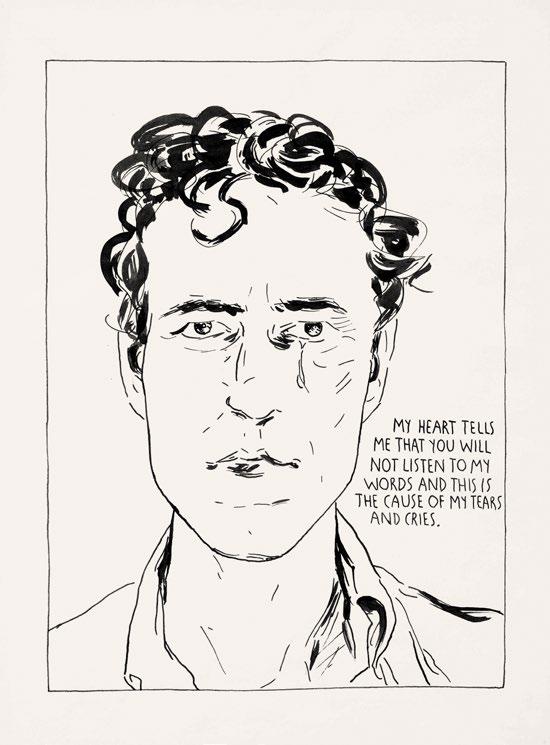

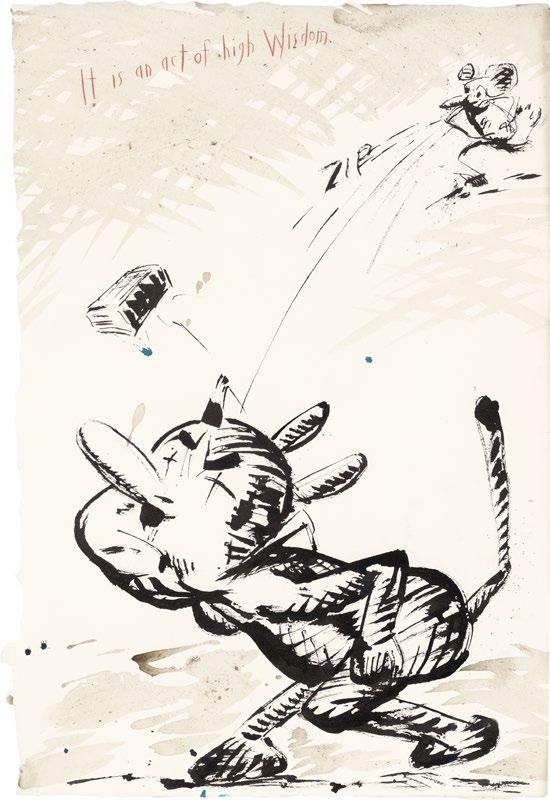

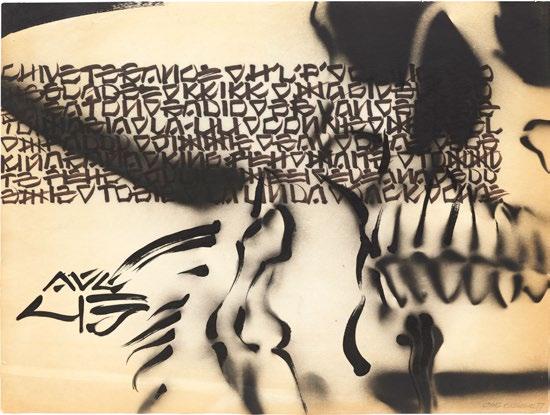

RAMMELLZEE (1960–2010) started train writing on the New York subways at just nine years old, going by the name Stimulation Assassination: Tagmaster Killer. By nineteen, he had decided to legally change his name to RAMM:ELL:ZEE. Letters and language were central to how RAMMELLZEE approached his career as an artist, musician, fashion designer, performer, and philosopher. He viewed subway writing, hip-hop, rap, and the related art forms emerging at the time as part of a cultural whole that waged war on the white supremacy built into the fabric of the United States. RAMMELLZEE created his own vocabulary to define the “works of war” he created with his peers. He described much of his work as “Gothic Futurism,” alluding to the ability of both medieval illuminated manuscripts and graffiti writing to abstract, expand, and

recontextualize letters previously thought to have a static and narrow meaning. The term also referenced RAMMELLZEE’s desire to create work that enacted a new kind of future while being made in a time that he believed had regressed in many ways to something archaic (“gothic”) when it came to inequity and control exerted by those in power. As a musician and lyricist in addition to a graffiti writer, RAMMELLZEE—in collaboration with K-Rob, Al Diaz, and Jean-Michel Basquiat—created the foundational ten-minute rap track “Beat Bop” in 1983. He also appeared in Wild Style and Style Wars, two early and influential films about the burgeoning culture of hip-hop and graffiti writing, and he became known for creating rich ensembles from discarded materials found on the street and in the subways. —IK

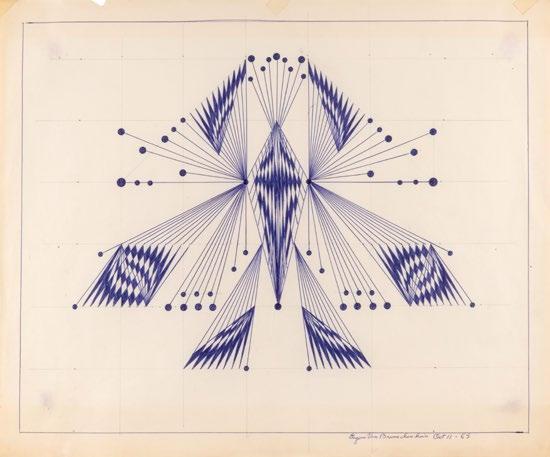

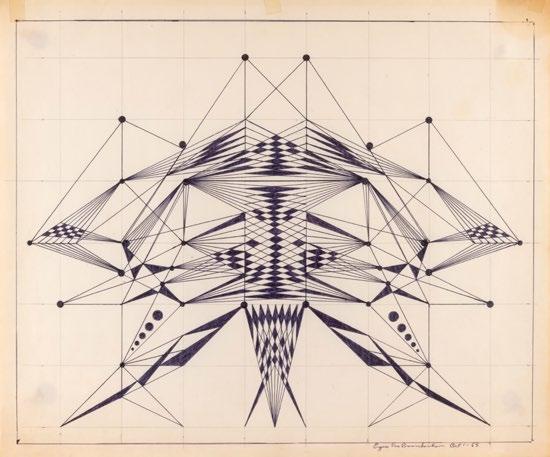

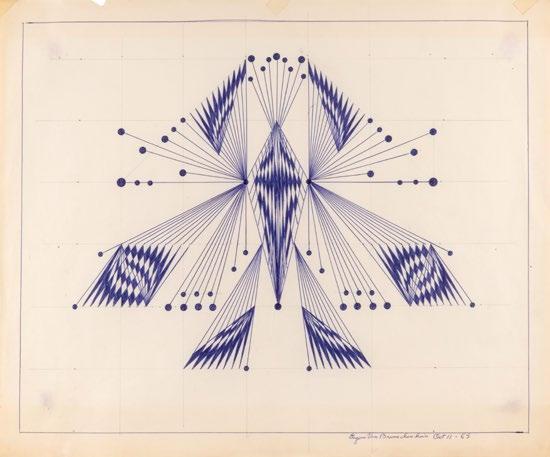

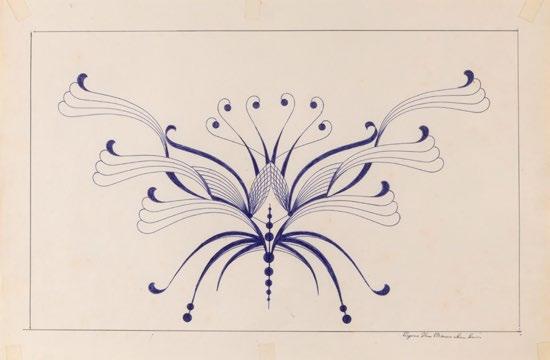

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910–1983) described himself as a “Freelance Artist—Poet and Sculptor—Innovator—Arrow maker and Plant man—Bone artifacts constructor—Photographer and Architect—Philosopher.” Born in Wisconsin, the artist spent most of his life working in a bakery and making art during his free hours. Like many self-taught artists, Von Bruenchenhein made use of the materials that were readily available to him. He is known for his twisting towers of poultry bones; unfurling vessels made of pinched clay leaves baked in his coal oven; vibrant paintings on the corrugated cardboard or Masonite he brought home from the bakery, on which pigment is layered and scratched into with combs, bits of paper, brushes made from his wife’s hair, and other tools; and floral pinup photographs of his wife Marie. From 1954 to 1964, Von Bruenchenhein averaged one painting a day, blending his horticultural knowledge with the anxiety brought on by the nuclear age into scenes both apocalyptic and alien. In the 1960s, following his retirement, Von Bruenchenhein began to create ballpoint-pen drawings—crisp monochromatic translations of the same organic scrolling and architectural forms that grace his other works. By the time of his death, Von Bruenchenhein had filled his home with several thousand artworks, which finally gained recognition in the late 1980s after the artist’s friend Daniel Nycz brought them to the attention of the Milwaukee Art Museum. —IK

PL. 114

Untitled, 1965

Ballpoint pen on paper

14 3/4 x 17 3/4 inches (37.46 x 45 cm)

PL. 115

Untitled, c. 1965

Ballpoint pen on paper

11 3/4 x 17 3/4 inches (29.84 x 45 cm)

PL. 116

Untitled, c. 1965

Ballpoint pen on paper

15 x 18 inches (38 x 45.7 cm)

PL. 117

Untitled, c. 1965

Ballpoint pen on paper

12 x 17 3/4 inches (30.48 x 45 cm)

Artist, rapper, and dancer PHASE 2 (1955–2015) was a pioneer of style writing and hip-hop culture in 1970s New York. Born in Manhattan, Michael Lawrence Marrow grew up primarily in the South Bronx, entering the world of “style writing”—painting train cars with an energetic marriage of text and image—in October of 1971 and taking on the name PHASE 2. He is credited with introducing many of the styles that would become staples for fellow writers, complete with his own names for each form: “softies” (bubble letters), “phasemagorical phantasmic” (bubble letters with stars), “squish luscious” (energetic streaked and squished bubble letters), and “bubble cloud” (bubble letters surrounded by clouds) as well as interconnected loops and arrows. By 1975, PHASE 2 transitioned from writing on subway cars to paper and canvas, beginning to create party fliers in a style he dubbed “funky nous deco” that referenced Jack Kirby comics, the work of Romare Bearden, and Art Deco marquees. Engaging in multiple forms of creative expression, he was also a founding member of the b-boy crew New York City Breakers, a rapper, a DJ, and an art director and writer for the magazine IGTimes. —IK

120

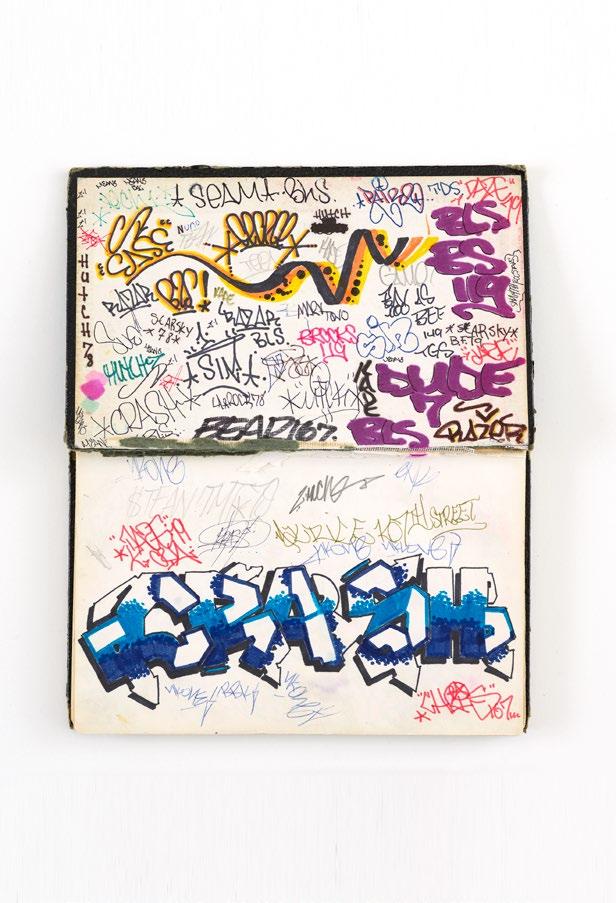

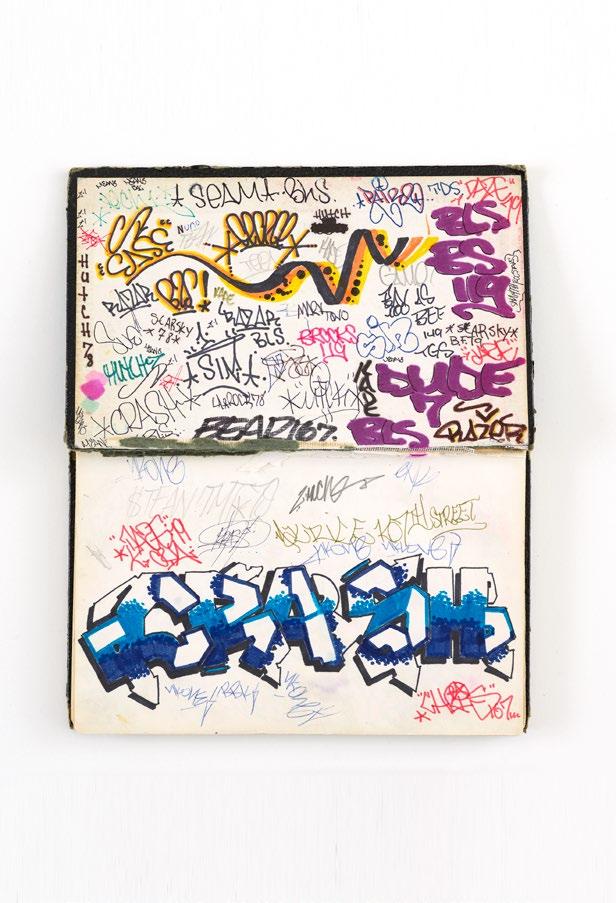

DONDI, born Donald Joseph White (1961–1998), was a seminal figure in the graffiti art movement of the 1970s and ’80s long before “street art” entered the mainstream lexicon. Nicknamed “DONDI” in childhood, he grew up in East New York, Brooklyn, where his early fascination with drawing led him to explore graffiti as both an art form and a means of navigating neighborhood boundaries. By the mid-1970s, DONDI had joined the graffiti crew TOP (The Odd Partners), quickly gaining renown for his meticulous technique and distinctive style. His ability to blend soft colors with precise lettering set him apart, making his work instantly recognizable across the boroughs and beyond. DONDI’s artistic evolution mirrored New York’s changing landscape; as downtown galleries began to embrace graffiti in the early 1980s, he emerged as one of the movement's pioneers, showcasing his work in prestigious venues both locally and internationally. Despite graffiti's ephemeral nature, with many pieces lost to time or city cleanup efforts, DONDI's legacy— following his death at the age of thirty-seven from complications related to AIDS—endures through iconic photographs and sketches that captured the essence of his art. —RD

PL. 120

Untitled (Black book), c. 1981

Mixed media

6 x 7 7/8 inches (15.2 x 20 cm)

PL. 121

Untitled (for Duck Rock), c. 1983

Ink on paper

12 1/4 x 17 inches (31.1 x 43.1 cm)

PL. 122

Untitled, 1983

Graphite and ink on paper

7 1/4 x 12 inches (18.4 x 30.5 cm)

PL. 123

Untitled (D-5), 1994

Ink, color pencil, graphite, and collage on paper

19 x 15 inches (48.3 x 38.1 cm)

PL. 124

Untitled (Sketchbook), 1984–86

Mixed media

5 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches (14 x 21.6 cm)

PL. 125

Untitled (Sketchbook), 1978

Mixed media

9 x 11 inches (22.8 x 27.9 cm)

PL. 126

Untitled (Black book), 1980–81

Mixed media

11 x 16 1/2 inches (27.9 x 16.5 cm)

PL. 127

Untitled (Black book), 1982

Mixed media

11 x 8 3/8 inches (27.9 x 21.2 cm)

PL. 128

Untitled, 1978

Graphite on paper

8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

PL. 129

Untitled, n.d.

Mixed media on paper

7 7/8 x 10 3/8 inches (20 x 26.3 cm)

PL. 130

Untitled, n.d. Ink on paper

7 7/8 x 10 1/2 inches (20 x 26.7 cm)

PL. 131

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite and ink on paper

8 1/8 x 10 3/4 inches (20.6 x 27.3 cm)

PL. 132

Untitled, 1981

Mixed media on paper

8 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches (21.6 x 19 cm)

PL. 133

Untitled, 1981

Mixed media on paper

9 1/2 x 6 1/2 inches (24.1 x 16.5 cm)

PL. 134

Children of the Grave!, 1985

Watercolor and ink on paper

20 7/8 x 29 5/16 inches (53 x 74.5 cm)

Above (from top): PLS. 126, 127

Above (from top): PLS. 130, 131

BLADE , a Bronx native born in 1957 as Steven Ogburn, first began graffiti writing on buses and mail trucks in 1971. In 1972, fellow artist Hondo 1 brought BLADE to the Baychester lay-up (an above-ground site where trains are parked) in the Bronx, and he painted his first subway car. Over the next decade or so, BLADE painted over 5,000 train cars, collaborating on his final car with SEEN in 1984. BLADE has been called the King of Trains and the King of Graffiti for his prolific work and his place as a pioneer of New York graffiti culture. His innovative bubble-letter style, continuous reinvention of his own name, bright color palettes, and abstract designs became a source of inspiration for the writers who came after him. Following his final train car piece in the early 1980s, BLADE transitioned into working on paper and canvas. He had his first solo exhibition in Europe in 1981, was included in almost all the early exhibitions on graffiti in the early to mid-1980s, and has since exhibited extensively throughout the United States and Europe. —IK

PL. 135

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

9 11/16 x 7 5/16 inches (24.6 x 18.6 cm)

PL. 136

In and Out (Train Study), 1980

Graphite on paper

5 15/16 x 8 3/4 inches (15 x 22.2 cm)

PL. 137

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

4 1/2 x 4 inches (11.4 x 10.2 cm)

PL. 138

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

8 13/16 x 5 7/8 inches (22.4 x 14.9 cm)

PL. 139

Untitled, 1978

Graphite on paper

5 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches (14.6 x 24.1 cm)

PL. 140

Untitled, 1978

Mixed media on paper

5 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches (14.6 x 24.1 cm)

PL. 141

Untitled, 1978

Graphite and marker on paper

5 13/16 x 9 1/2 inches (14.8 x 24.1 cm)

PL. 142

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

6 x 10 1/16 inches (15.2 x 25.5 cm)

PL. 143

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

4 7/8 x 7 3/4 inches (12.4 x 19.7 cm)

PL. 144

Untitled, 1978

Graphite on paper

5 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches (14.6 x 24.1 cm)

PL. 145

Untitled (Black book), 1978

Mixed media

6 x 10 inches (15.2 x 24.5 cm)

PL. 146

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite on paper

6 3/16 x 9 11/16 inches (17.3 x 24.6 cm)

PL. 147

Untitled, n.d.

Graphite and ink on paper, in 2 parts

5 7/8 x 17 3/8 inches (14.9 x 44.1 cm)

Above (from top): PLS. 139, 140, 141

Above (from top): PLS. 142, 143, 144

Above (top): PL. 147

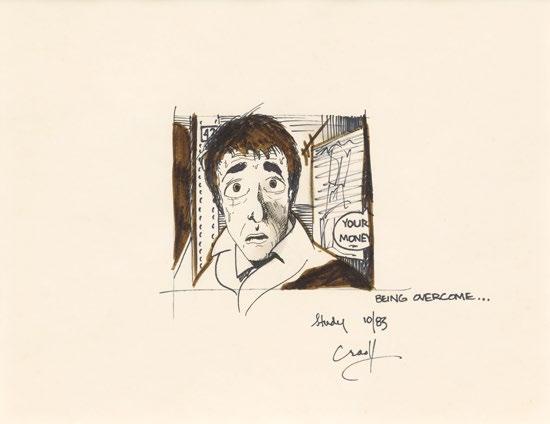

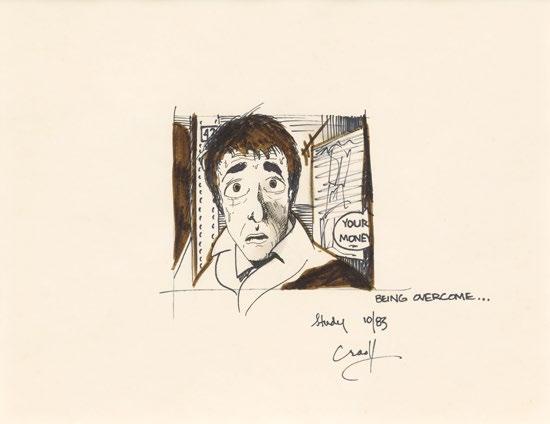

A Bronx native, CRASH (1961–) began making his mark in the world of graffiti at the age of thirteen, following older teens to train yards and “bombing” subway cars with tags. Adopting the name “CRASH” after a school computer mishap, his tag—characterized by its vivid colors, intricate designs, and a distinctive blend of cartoon-like imagery and abstract forms—quickly became recognizable across New York City. In 1980, CRASH transitioned from the train yards to the art galleries, curating the pivotal Graffiti Art Success for America at the Bronx gallery Fashion Moda (1980), an exhibition that featured artists such as FUTURA 2000, Fab 5 Freddy, and Lee Quiñones. This landmark show propelled graffiti into the mainstream art world and cemented the then nineteen-yearold CRASH’s pioneering role in the movement. His work quickly gained popularity across Europe, America, and Asia, leading to numerous exhibitions in museums and galleries worldwide. —RD

Above (from top): PL. 152, 153

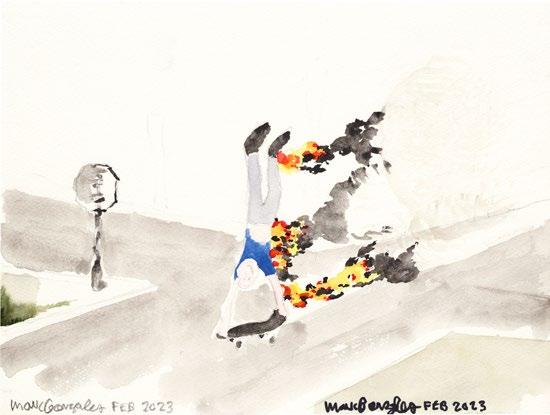

Lifelong New Yorker Christopher Ellis (1962–) began tagging subway trains as DAZE starting in 1976 while still a student at the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan. In the early 1980s, he began a gradual shift from graffiti writing to studio work, creating innovative aerosol paintings on canvas that merged figurative elements with expressive abstract forms. A painting on newsprint, tagged in collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, was among his earliest studio works and was first exhibited in the legendary Mudd Club exhibition Beyond Words (1981) curated by FUTURA 2000 and Fab 5 Freddy. This was closely followed by his first solo exhibition at Fashion Moda, an alternative art space located in a South Bronx storefront. DAZE’s early inspirations range from Marvel comics and graphic illustrations by underground comix artist R. Crumb, to work by urban visionary artist Martin Wong and first-generation graffiti pioneers that include BLADE and PHASE 2. DAZE has also created public art projects alongside artists Lee Quiñones and CRASH, including a 1995 design for a train station in Hannover, Germany. DAZE continues to live and work in New York City. —RD

PL. 156 Untitled (Black book), 1994

PL. 157 Untitled (Black book), 1982

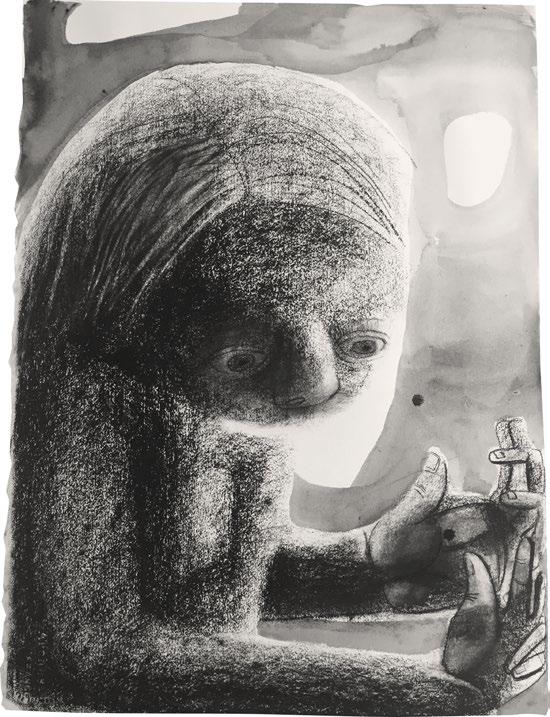

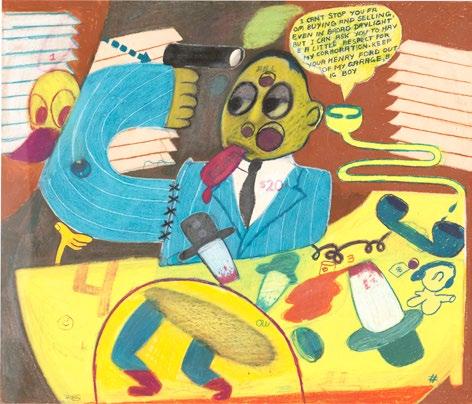

Mike Kelley was a visionary contemporary artist whose work explored a wide range of mediums, including performance, installation, drawing, assemblage, painting, video, photography, sound works, text, and sculpture. Born in 1954 in Detroit, Michigan, Kelley grew up as the youngest of four children in a working-class Catholic family. He studied at the University of Michigan and later at the California Institute of the Arts, where he was mentored by the conceptual artist John Baldessari and the experimental filmmaker Tony Oursler. He first gained prominence in the 1980s with provocative and often sardonic pieces that combined high art with elements of punk rock and underground culture. In his series Garbage Drawings, Kelley engaged with themes of societal waste and the overlooked aspects of everyday life by isolating fragments of garbage piles from the American WWII comic series Sad Sack. In 1992, he began teaching at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design. Kelley lived and worked in Los Angeles for almost forty years until his death in 2012. —RD

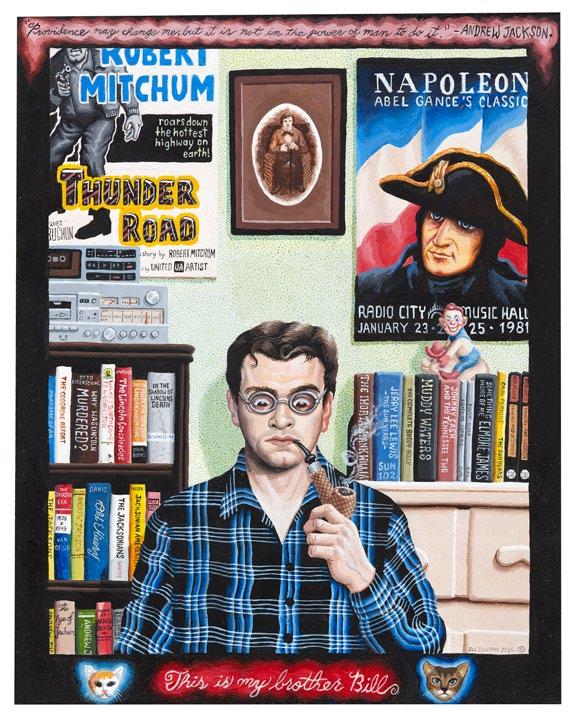

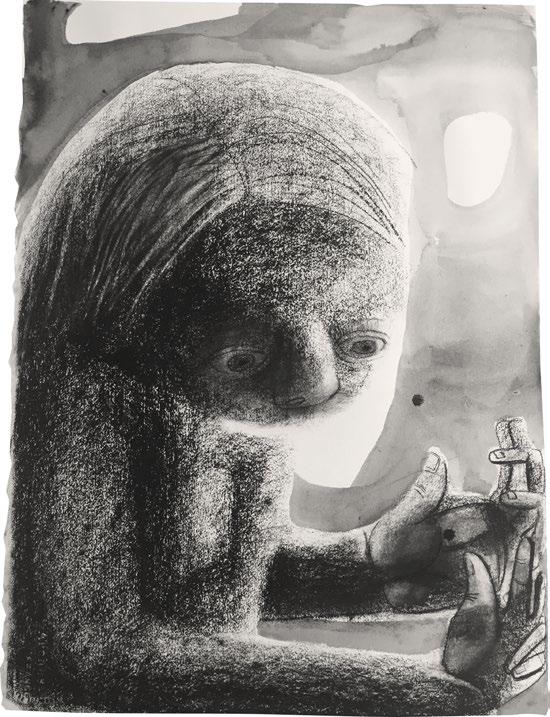

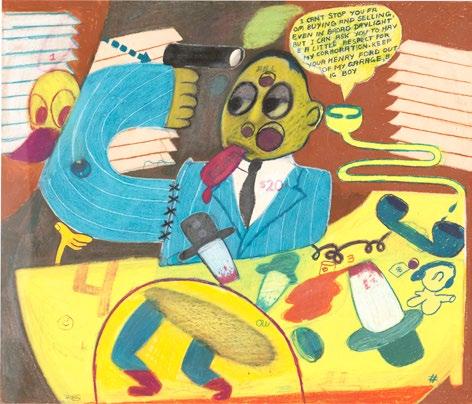

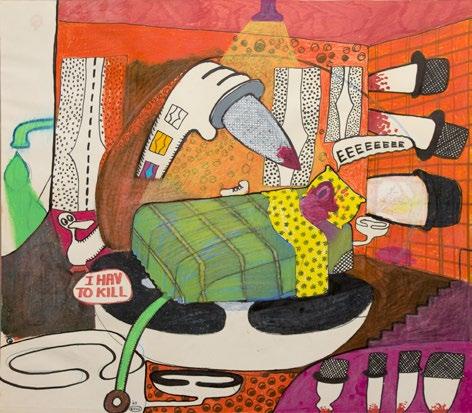

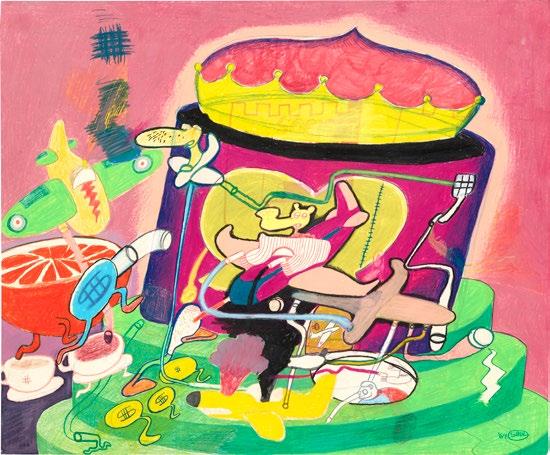

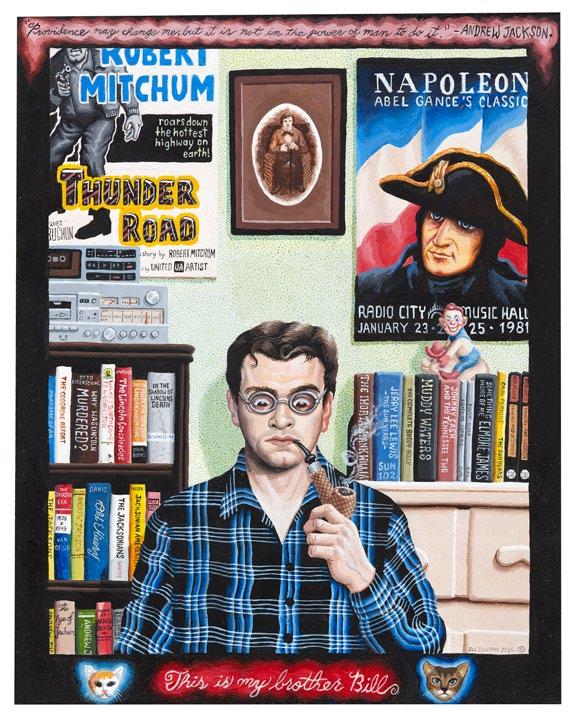

Joe Coleman (1955–) is a New York-based painter, writer, and performer whose career spans four decades. He gained early acclaim as a member of the punk band Steel Tips during the 1970s and with his transgressive performance art in the 1980s as well as his work in underground comix, including the graphic novel The Mystery of Woolverine Woo-Bait (1982). His primary focus eventually shifted to his meticulously crafted paintings, created with jeweler’s lenses and a single-hair brush, and often requiring years to complete. Incorporating numerous smaller scenes and symbolic elements within a single work, these macabre portraits explore the grim aspects of human nature and society, delving into themes of violence, mortality, and the grotesque. An avid collector, Coleman has amassed an eclectic collection in his private museum, the Odditorium, which houses sideshow objects, wax figures, crime artifacts, and religious works that explore the darker side of the American psyche. —RD

PL. 159

Henry Darger, 1998

Acrylic on panel 24 1/4 x 30 1/2 inches (61.6 x

PL. 160

The Holy Saint Adolf II [Adolf Wölfli], 1995 Acrylic on panel 34 x 28 inches (86.4 x 71.1 cm)

PL. 161

This is My Brother Bill, 1986

Acrylic on panel

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

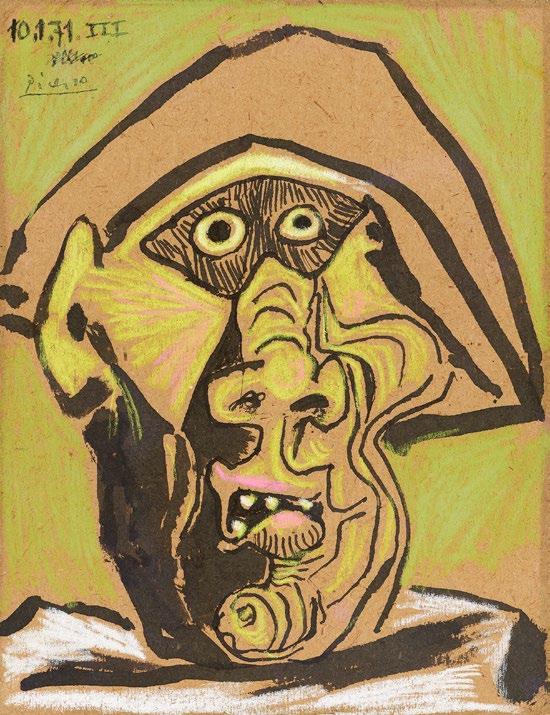

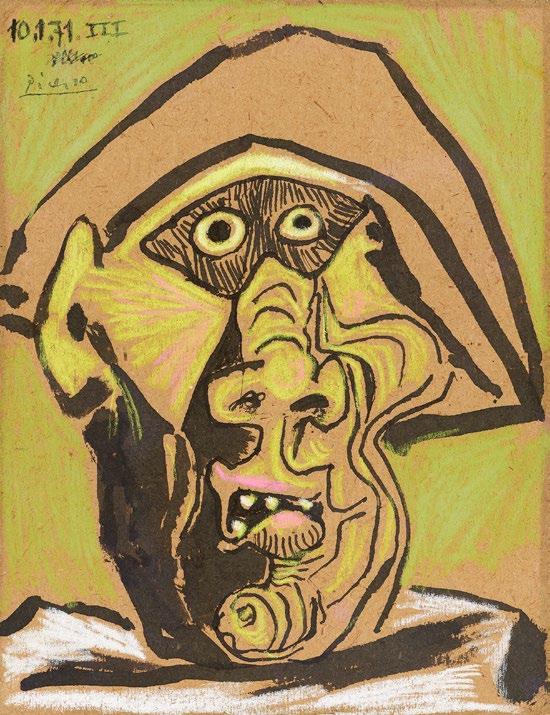

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) is best known as a Cubist innovator, though his work spans several of the major art movements of the late-nineteenth and earlytwentieth centuries. Picasso produced over 20,000 artworks that trace both the political and artistic trajectory of the time, from his early blue period, defined by sullen expressionistic images of poverty and despair; to his Cubist explorations in the early 1910s, fragmenting and reconstituting subjects to compress multiple times and views into one two-dimensional image; to his neoclassical works of the 1920s; to a foray into Surrealism later in the decade; and to visual commentaries as the Spanish Civil War gave way to World War II. Among the themes that appeared throughout Picasso’s career were friends and lovers, musicians, mythological subjects, bulls, fauns, war, and Harlequins like the one included in this presentation. Finding success within the art world during his lifetime, Picasso used the money he earned as an artist in part to amass his own collection of works by other artists. —IK

PL. 162

Tête d'Arlequin Masqué (Head of a Harlequin in a Mask), 1971 Ink and pastel on cardboard 11 1/8 x 8 1/2 inches (28.2 x 21.6 cm)

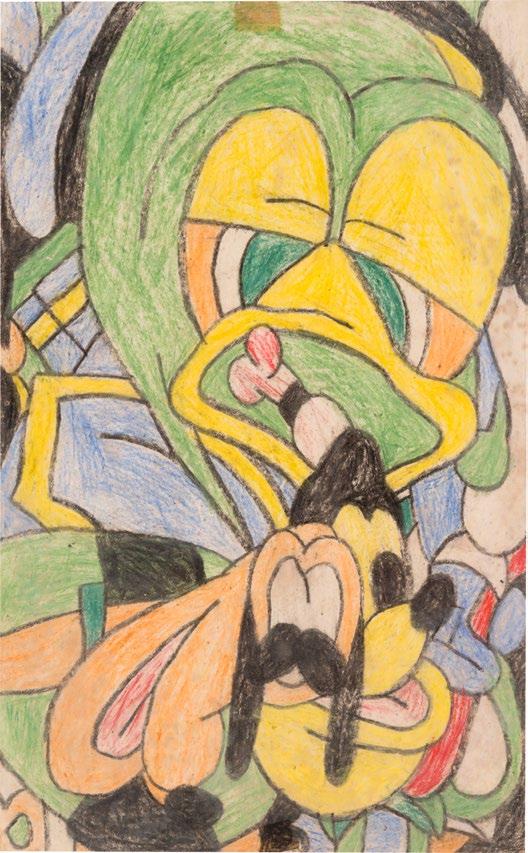

Jim Nutt (1938–) began his career with a series of exhibitions between 1966 and 1969, alongside the five other members of the midcentury Chicago-based exhibition group the Hairy Who: Jim Falconer, Art Green, Suellen Rocca, Karl Wirsum, and Gladys Nilsson, who married Nutt in 1961. Initially, however, Nutt had studied architecture at Washington University of St. Louis, where a figure drawing class sparked his interest in drawing and painting. Moving to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Nutt graduated in 1965, joining a small group of like-minded artists known for their colorful, graphic figurative works inspired by comics as much as by fine art. Nutt’s paintings, drawings, and prints are linear, geometric images of figures in rude, slapstick, or surreal situations, while others are portraits of flattened, stylized faces gazing out at the viewer. In some of his works he reverse paints on Plexiglas or builds custom frames to contextualize the work; in others he allows fine pencil lines and delicate shading on paper to define his singular characters. Nutt still lives and works in Chicago. —IK

PL. 163

Boop, c. 1968–69

Acrylic on acrylic in artist’s frame

18 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 1 1/8 inches (47 x 36.8 x 2.9 cm)

PL. 164

Drawing for Pug, 1990

Pencil on gray laid paper

12 3/4 x 12 3/4 inches (32.4 x 32.4 cm)

PL. 165

Twixt, 1996

Graphite on paper

17 x 11 1/4 inches (43.2 x 28.6 cm)

PL. 166

Is this the right way?, 1979

Graphite and color pencil on paper

11 x 13 inches (27.9 x 33 cm)

PL. 167

Really!? (thump thump), 1986

Color pencil on paper

14 x 16 inches (35.6 x 40.6 cm)

PL. 168 an absolute, 1983

Color pencil on paper

9 15/16 x 17 1/4 inches (25.2 x 43.8 cm)

PL. 169

Quick Twittle Twittle, 1978

Color pencil on paper

10 3/4 x 9 1/8 inches (27.3 x 23.2 cm)

Above (from top): PLS. 166, 167

Above (from top): PLS. 168, 169

Julie Curtiss (1982–) is a mixedmedia artist whose paintings, sculptures, and works on paper explore the interplay between nature and culture through reimagined female archetypes. Using Surrealist stratagems of picture-making, including close-cropped compositions and exaggerated, cartoon-like forms, Curtiss mines her subjects from everyday life to create drawings that are at once fantastical, precise, and cinematic. Central to her work is the fragmented female body, depicted through symbols of stereotyped femininity—such as long nails or high heels—deployed in an exploration of identity, perception, and the hidden complexities of human experience. Influenced by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French painting, the Chicago Imagists, pop imagery, and Japanese comics and manga, Curtiss’s work is marked by a vivid color palette and a grotesque sense of the uncanny. Born and raised in Paris, France, she studied at the École des BeauxArts. After graduating, Curtiss moved to Japan for a year, then relocated to Brooklyn, where she worked in the studios of Jeff Koons and KAWS. —RD

PL. 170

Gator, 2022

Gouache, watercolor, and acrylic on paper

9 x 12 1/4 inches (22.8 x 31 cm)

Like her fellow Chicago Imagists, Gladys Nilsson (1940–) creates distorted, graphic figurative artwork defined by confident lines and liberal use of color, and rooted in both modernism and comics. Nilsson, along with husband Jim Nutt, was part of the group known as the Hairy Who, formed in 1965 as a means for all its members, newly graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, to draw more attention to their work. Nilsson, who grew up in Chicago, visited the Art Institute of Chicago as a child, before attending the school in the early 1960s and eventually returning as a professor for over twenty-five years. While Nilsson has traditionally rendered scenes in pencil and watercolor—or on Plexiglas, also popular with other members of the Hairy Who— she has also increasingly introduced collage into her body of work, yeilding more opportunity to play with scale and distortions of her characters and their surroundings. —IK

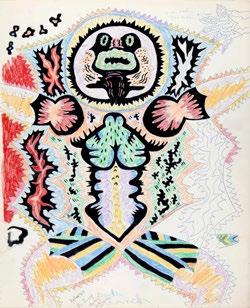

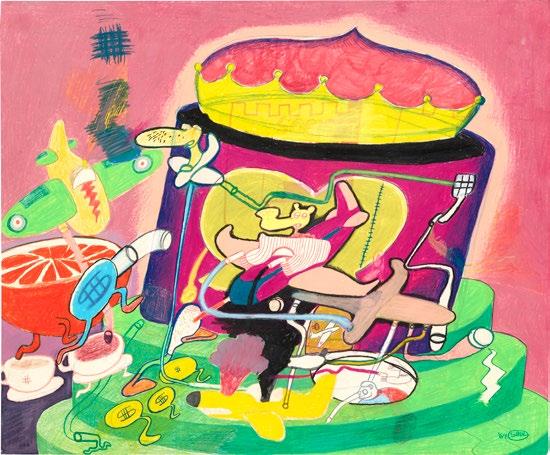

One of six artists who made up the Chicago-based exhibition group the Hairy Who, Karl Wirsum (1939–2021) created vibrant figurative work in a bold graphic style. Initially interested in becoming a cartoonist, Wirsum attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), graduating in 1961 as a fine artist. Wirsum and fellow SAIC students formed the Hairy Who in order to collectively increase the impact of their work, recognizing commonalities among their colorful compositions populated by exaggerated bodies and assertive line work. Wirsum’s art maintained some of his earlier comic influences but also made reference to Surrealism, Dadaism, Japanese woodblock prints, ancient Mesoamerican art, Paul Klee, Matisse, and SAIC instructor Ray Yoshida. In colors ranging from neon to primary, sometimes blocked or inscribed on a black background, Wirsum created frontfacing figures vibrating with energy. Among his subjects are musicians like those he encountered growing up on the South Side of Chicago, robotic and alien humanoids, demons, and creatures with segmented and contorted bodies. Wirsum first exhibited in 1966 with the Hairy Who and held his first solo exhibition a year later at Marjorie Dell Gallery, also in Chicago. —IK

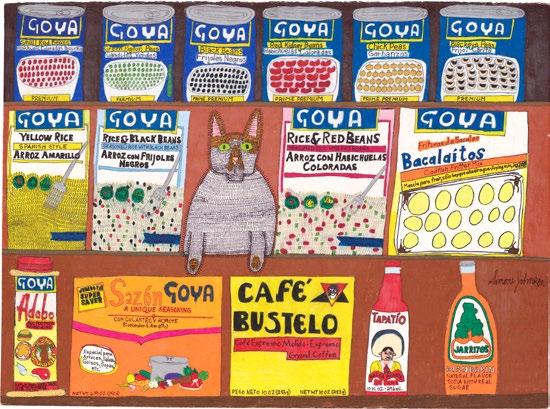

PL. 172

Untitled (Study for Show Girl series), 1969 Ink on paper

30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

PL. 173

Untitled (Study for the painting Screamin’ J. Hawkins), 1968

India ink, ballpoint pen, and color pencil on paper

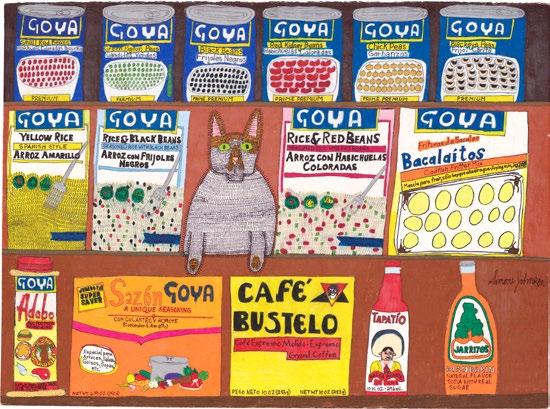

Growing up in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, Larissa De Jesús Negrón (1994–) watched her aunt draw from an early age. Inspired by this and by the prints of Salvador Dalí works that her father kept around the home, De Jesús Negrón began art classes at nine years old. Now living and working in Queens, New York, she creates works that express a nostalgia for home, an interest in Surrealism, and the play of interiority and exteriority that defines her life in the city. De Jesús Negrón’s work has been described as Neo-Surrealism, taking cues from René Margritte, David Salle, Louise Bourgeois, Frida Kahlo, and Salvador Dalí in creating introspective images using a blend of airbrush and oil painting. Objects of mundanity are common in her work: bathroom furniture, frames, and windows serve as portals into different realities. Water, including tears, is also a constant, acting as a surface for literal and figurative reflection. —IK

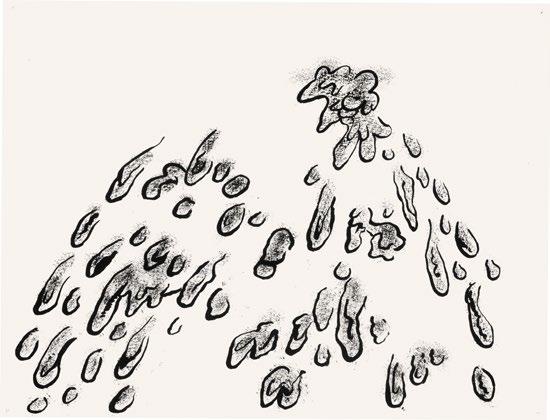

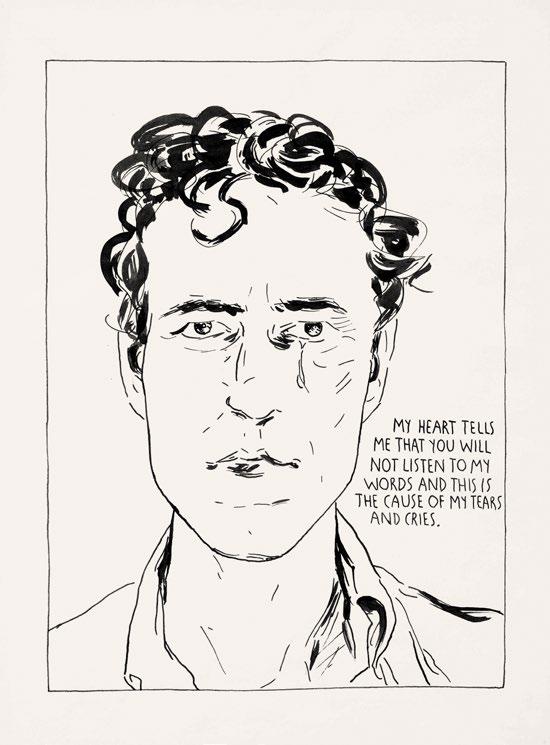

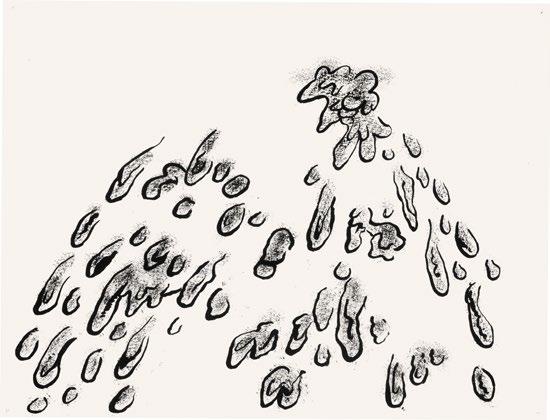

Born in Atlantic City in 1978, Julia Chiang studied studio art and art history at New York University, graduating in 2000. Originally drawn to the tactile nature of ceramics, Chiang began painting around 2011, first experimenting with watercolor and gouache on paper. Even as the artist moved from three to two dimensions, her interest in the material nature of her work remained. Her large, vibrant canvases are consumed by repeated forms, each with minute variation that reveals the nature of the paint and makes the composition breathe like an organism. In some works, Chiang includes enigmatic phrases— fragments of letter sign-offs and platitudes made up of the same leaf and teardrop shapes or spelled with slowly melting Ring Pops nailed directly to the wall. Chiang lives and works in Brooklyn. —IK

PL. 175 Not Feeling So Good, 2011

Gouache on paper

20 x 15 inches (50.8 x 38.1 cm)

Ana Benaroya (1986–) is a New York City-born, Jersey City-based artist known for her dynamic and provocative works that challenge conventional notions of femininity and desire. Her robust, muscular female figures defy traditional gender expectations and highlight a unique female gaze, portraying women in powerful, assertive roles. These figures, adorned with exaggerated musculature and striking, offbeat colors, explore themes of female desire and queer sensibility. Benaroya draws inspiration from various sources, including the graphic styles of superhero comics and artists like Peter Saul. As Benaroya has articulated, her aim is to create passionate depictions of female nudes from her own perspective, contributing to a richer, more inclusive visual language in contemporary art. Benaroya holds a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art (2008) and an MFA in Painting from Yale University (2019). —RD

PL. 176

Til Dawn, 2020

Marker and ink on Arches paper in artist’s frame

15 x 11 inches (38.1 x 27.9 cm)

PL. 177

In A Whirlpool, I’m Loving You, 2021 India ink and marker on two sheets of cut paper

14 x 22 inches (35.56 x 55.88 cm)

PL. 178

From Dusk, 2020

Marker and ink on Arches paper in artist’s frame

15 x 11 inches (38.1 x 27.9 cm)

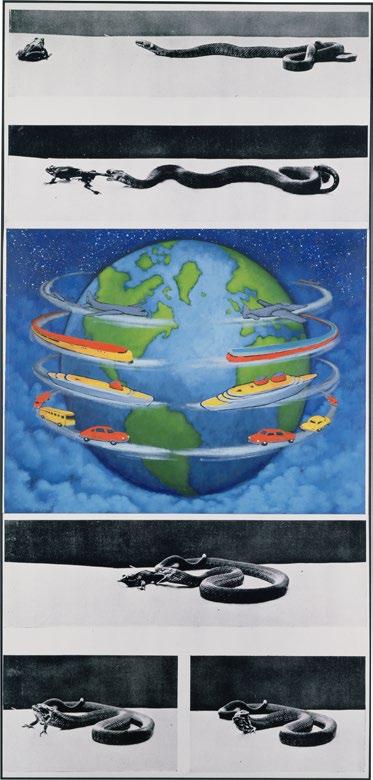

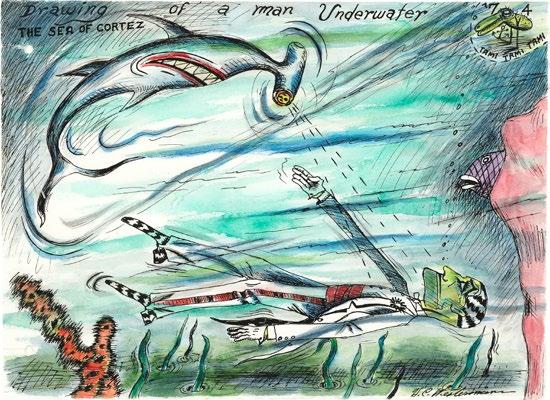

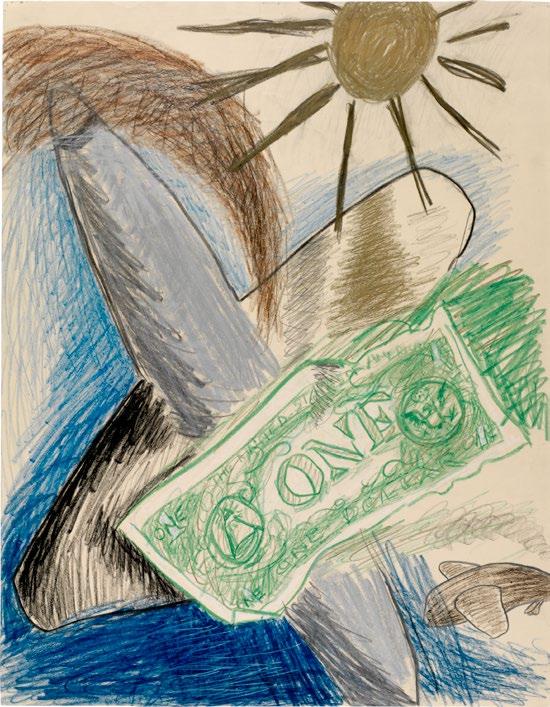

David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) used his wide-ranging artistic tool kit—drawing, music, painting, film, collage, photography, spray paint and stencils, and writing—to express affection, rage, desire, and sharp observations about the injustices of the world. During the first decade of his life, spent with his abusive father in suburban Michigan, Wojnarowicz retreated to the woods to play with the critters—snakes, bugs, and frogs—that would later recur in his work. In the mid-1960s, when the artist and his siblings moved to their mother’s home in New York, where they were largely unsupervised, he wandered through downtown Manhattan, engaging in sex work while attending the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan. Soon after he turned seventeen, he was living on the street and in a halfway house. Wojnarowicz met photographer Peter Hujar in 1980, forming a bond with his fellow artist that would result in a brief affair and a much longer companionship, collaboration, and mentorship. With encouragement from Hujar, Wojnarowicz began

to place more emphasis on his visual art, embracing the drawings and paintings he had begun making alongside his writing. Common motifs in Wojnarowicz’s work include ants swarming like warmongering bands of people; solitary and vulnerable frogs; the number twenty-three, a reference to the average number of chromosomal pairs found in humans; downtown New York and its denizens; cruel quotes from politicians who refused to recognize the crisis of AIDS and the humanity of the queer community; cowboys and buffalo; fires and explosions; maps; and sexual imagery. As the 1980s continued Wojnarowicz became a regular at East Village galleries, and in 1985 his work was included in the Whitney Biennial. Following Peter Hujar’s death from AIDS related complications in 1987 and his own diagnosis not long after, Wojnarowicz—already accustomed to laying bare the hatred and cruelty towards difference structured into society and law—began to create somber works that meditated on death. —IK

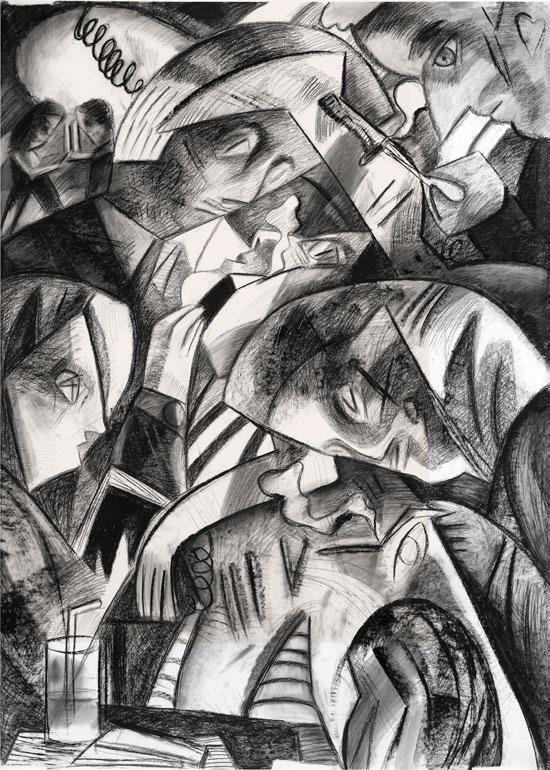

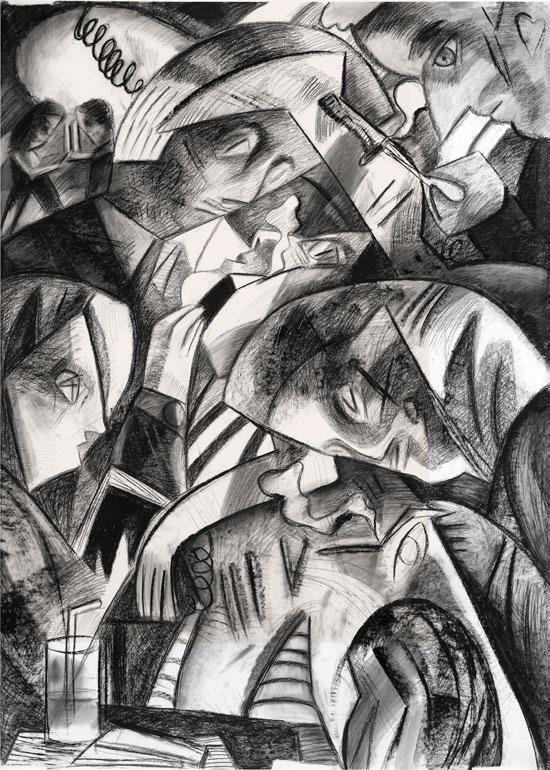

George Condo’s (1957–) works are populated by figures who range from grotesque, often built from fragmented and repeated body parts, to cartoonish. These imaginary portraits channel the artist’s longstanding interest in art history into what he calls “artificial realism,” a kind of reconstruction of abstraction into realism. Condo began drawing at an early age, progressing from YMCA art classes as a child in New Hampshire to music theory and art history studies at the University of Massachusetts. After graduating from college in the late 1970s, Condo briefly moved to Boston, where he played in a punk band, and in December of 1979 he moved to New York City, encouraged by fellow artist JeanMichel Basquiat and the flourishing downtown art scene. While in New York, Condo painted for Andy Warhol in the Factory and made his own work as well. His first solo exhibition was held in 1983 at Ulrike Kantor Gallery in Los Angeles, and Condo has shown his work extensively in the United States and abroad since—including at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019 and in retrospectives at The Phillips Collection in Washington D.C.; Louisiana Museum in Humlebæk, Denmark; the New Museum in New York; and the Museum of Modern Art in Salzburg, Austria. Condo moved to Paris in 1985 and remained there for a decade before returning to New York, where he lives and works today. —RD

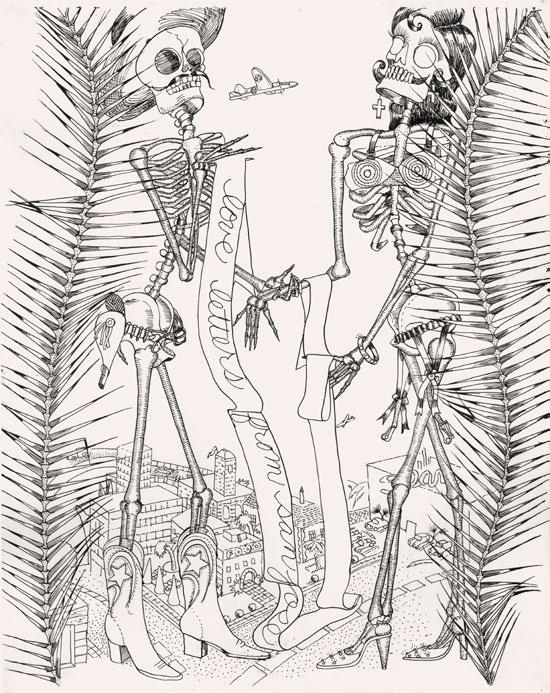

A groundbreaking figure in Abstract Expressionism, Willem de Kooning was born in 1904 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, into a workingclass family. His early talent for art led him to an apprenticeship with a design firm and night school at the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts and Techniques. In 1926, de Kooning immigrated to the United States. Settling in New York City in 1927, he quickly became involved in the art world, befriending notable artists like Stuart Davis and Arshile Gorky. During the Great Depression, de Kooning worked for the Works Progress Administration, which solidified his commitment to painting. By the late 1940s, he and contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko became central figures in the Abstract Expressionist movement. His 1948 solo exhibition at the Charles Egan Gallery marked his rise to prominence. De Kooning constantly explored new styles, refusing to adhere to a single artistic approach. In the 1970s, he began to experiment with sculpture, creating Clamdigger—for which this charcoal drawing serves as a preparatory sketch—in 1972. Inspired by shellfish diggers in Montauk, Long Island, this drawing brims with rapid, energetic marks and expressionistic whorls, highlighting de Kooning’s unique commitment to both abstraction and figuration. De Kooning completed his final painting in 1991 and passed away in 1997. —RD

PL. 181

Untitled (Clamdigger), c. 1970