Featured in this Issue

Student Awarded 2022 Children’s International Peace Prize EARCOS 52nd Leadership Conference Theme: “Together Again” Cover Story Preparing a School Community for DEIJB Work Through Developing Social and Emotional Competencies

EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL A Link to Educational Excellence in East Asia WINTER 2023

EARCOS

The

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Andrew Davies, President (International School Bangkok)

Stephen Cathers, Vice President (International School Suva)

Rami Madani, Treasurer (International School of Kuala Lumpur)

Margaret Alvarez, Past President (Director Emeritus ISS International School, Singapore)

Saburo Kagei (St. Mary’s International School)

Barry Sutherland (American International School Vietnam)

Laurie McLellan (Nanjing International School)

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou)

Elsa H. Donohue (Vientiane International School)

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School)

Andrew Hoover (ex officio), Office of Overseas Schools REO

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Elaine Repatacodo, ELC Program Coordinator

Giselle Sison, ETC Program Coordinator

Ver Castro, Membership & I.T. Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Webmaster, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator

Robert Sonny Viray, Accountant

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Assistant

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

In this Issue

2 Welcome

Message from the Executive Director

4 Press Release

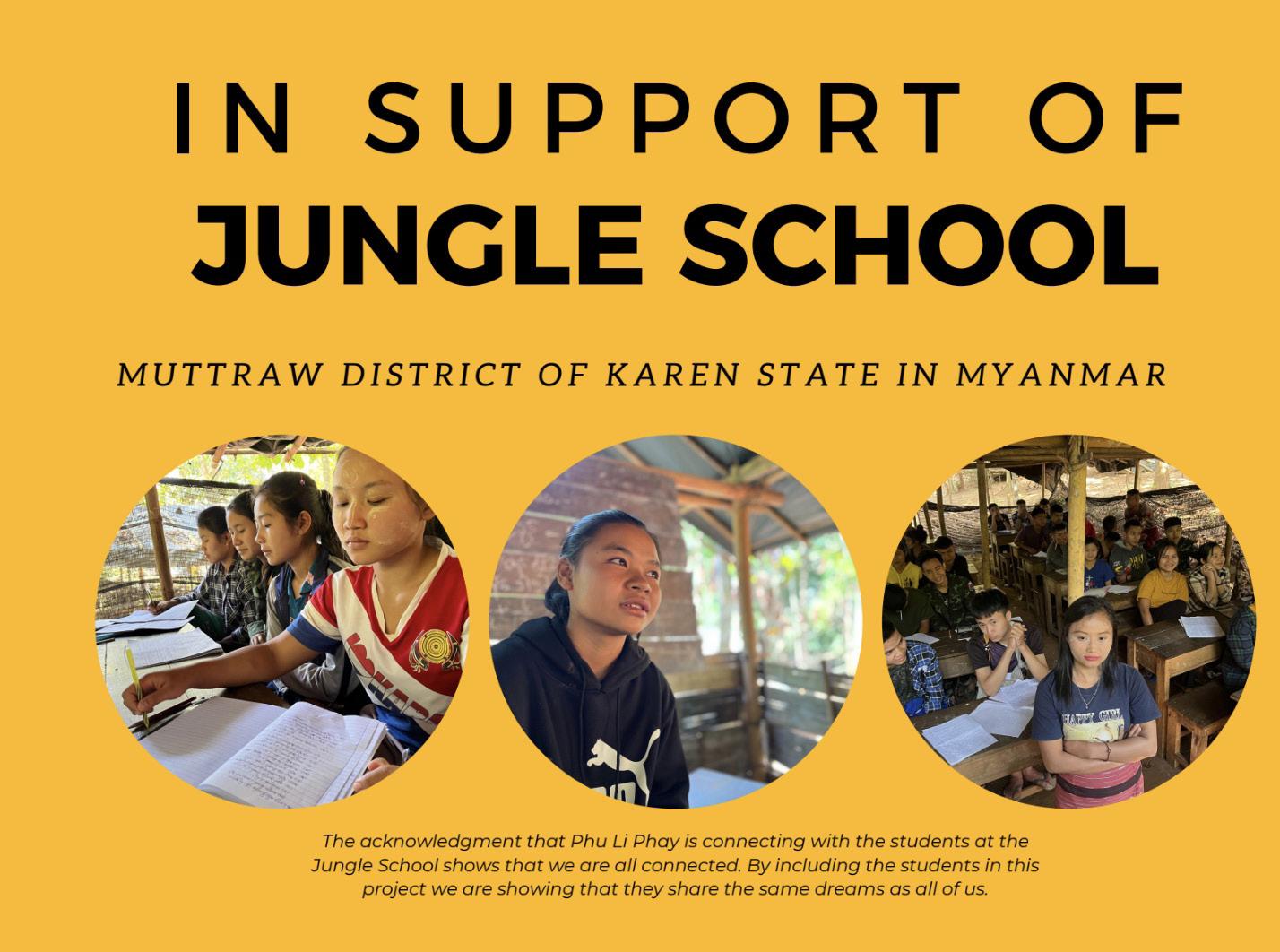

- EARCOS Student Awarded 2022 Children’s International Peace Prize

6 EARCOS Leadership Conference 2022 “Together Again”

10 EdThought

- Can we, please, shelve the traditional strategic plan now?

- Getting Started as an Instructional Coach

18 Cover Story

- Preparing a School Community for DEIJB Work Through Developing Social and Emotional Competencies

22 Curriculum

- Embracing Diversity through Differentiation

- Instructional Techniques within STEM Education

- Translanguaging and Linguistic Diversity: Practices for the International Classroom

- Beyond Rubrics and Ratings: Cultivating Agency and Coaching Teachers to Excellence With the Danielson Framework for Teaching

- Collaborating with Room to Fail

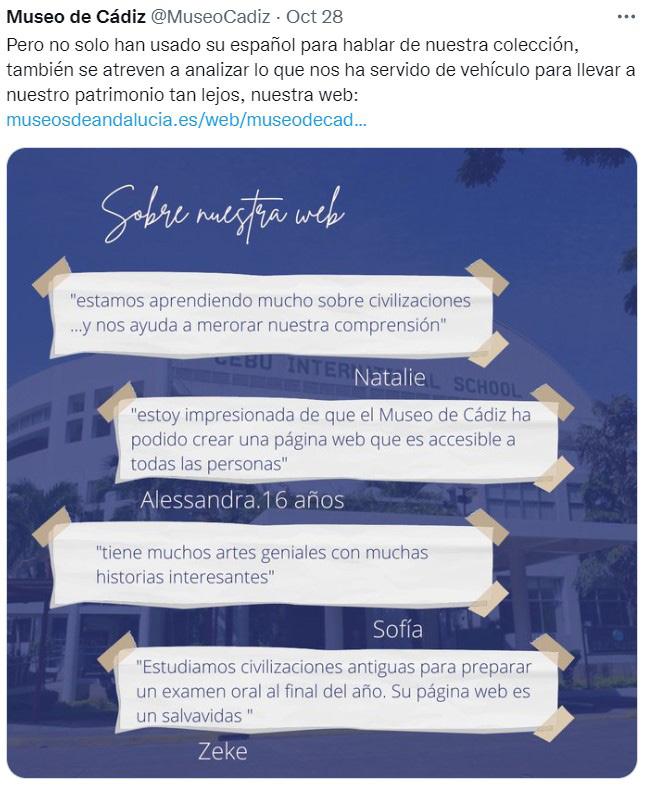

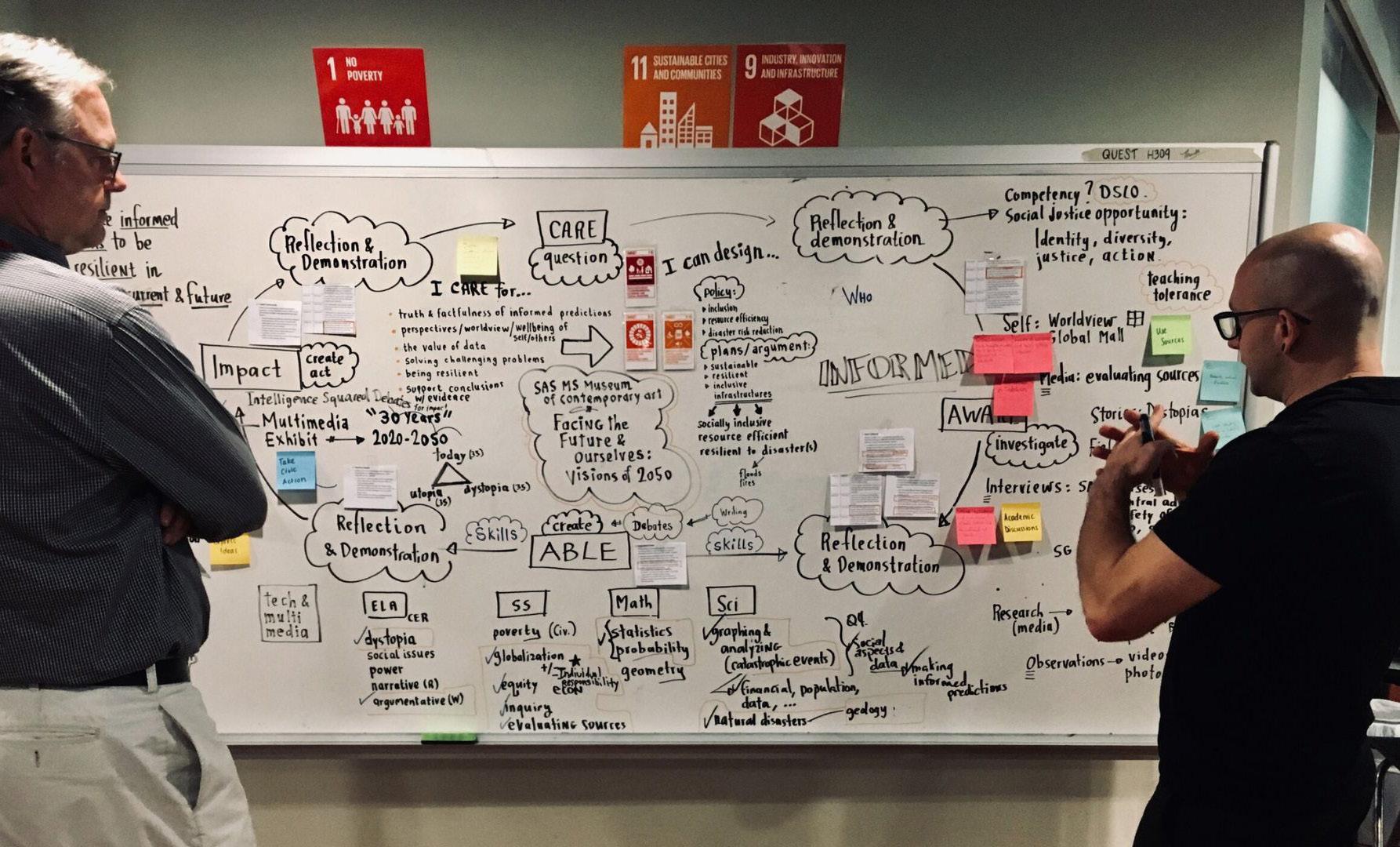

- Opening DORS: A Collaborative Learning Project

- Students at The International School Yangon Make an iMPACT

- Literary Gourmands Teaching genre to improve students’ literary response and enjoyment

- Salinometers in Seconds

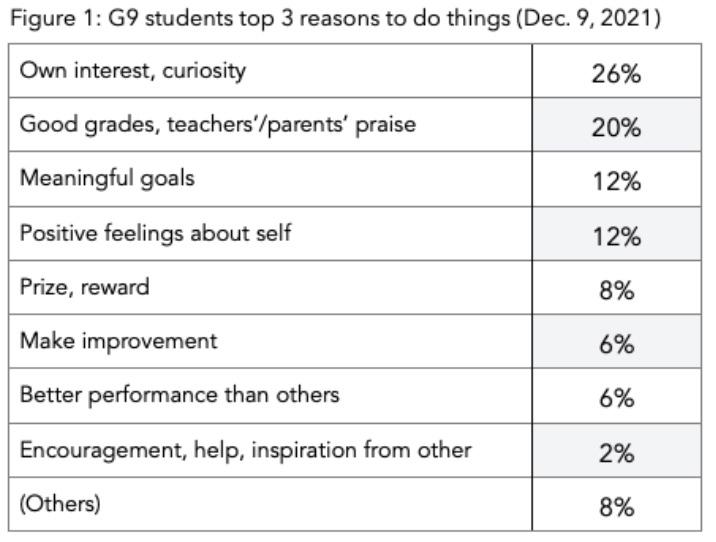

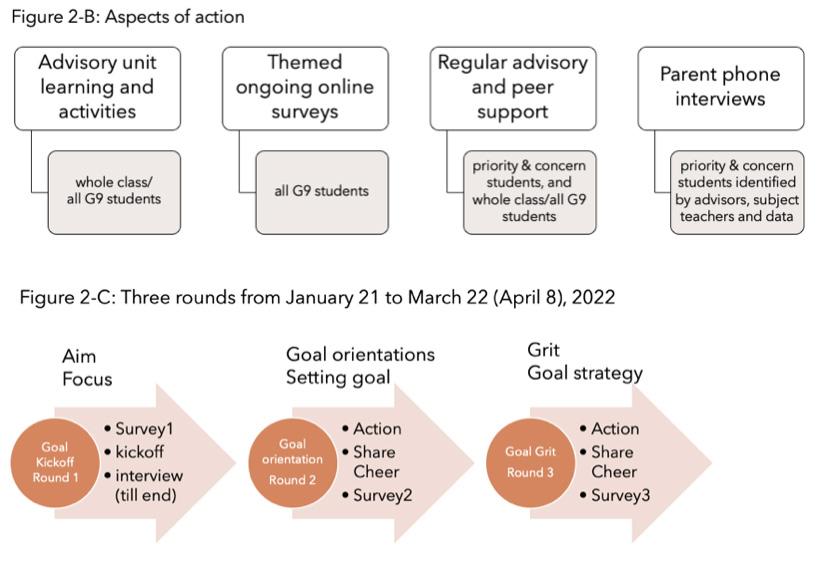

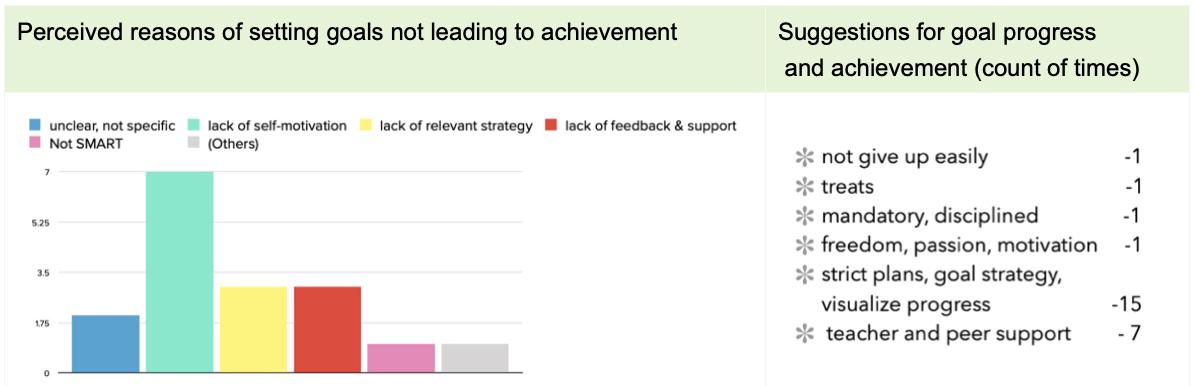

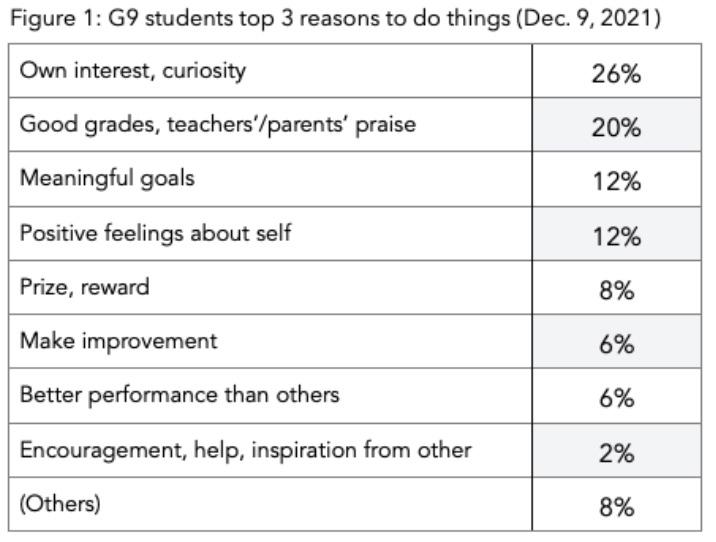

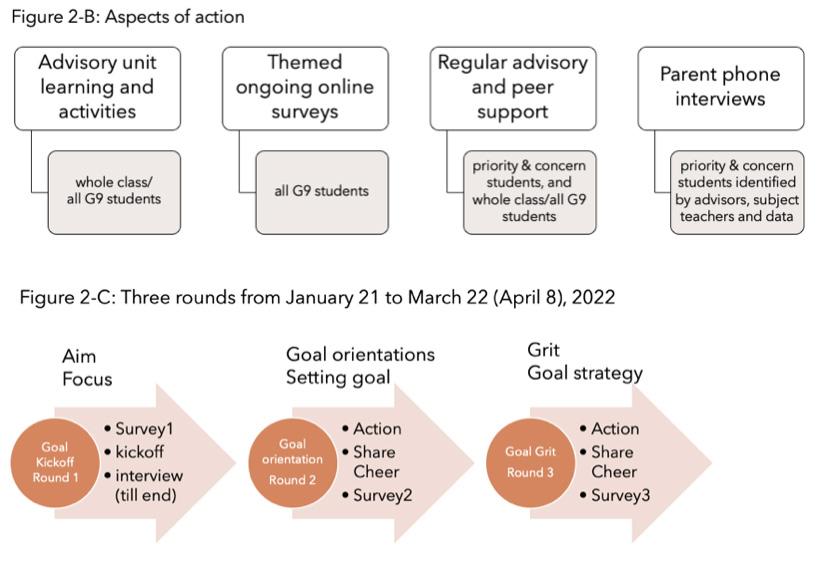

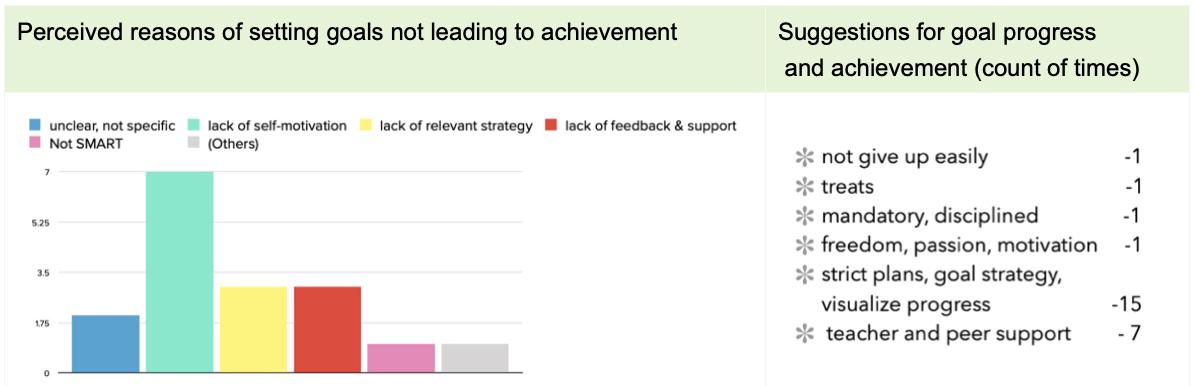

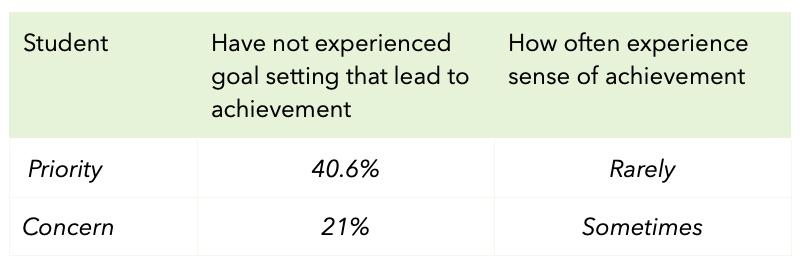

50 Wellbeing: Formative data and ongoing student goal support for wellbeing 54

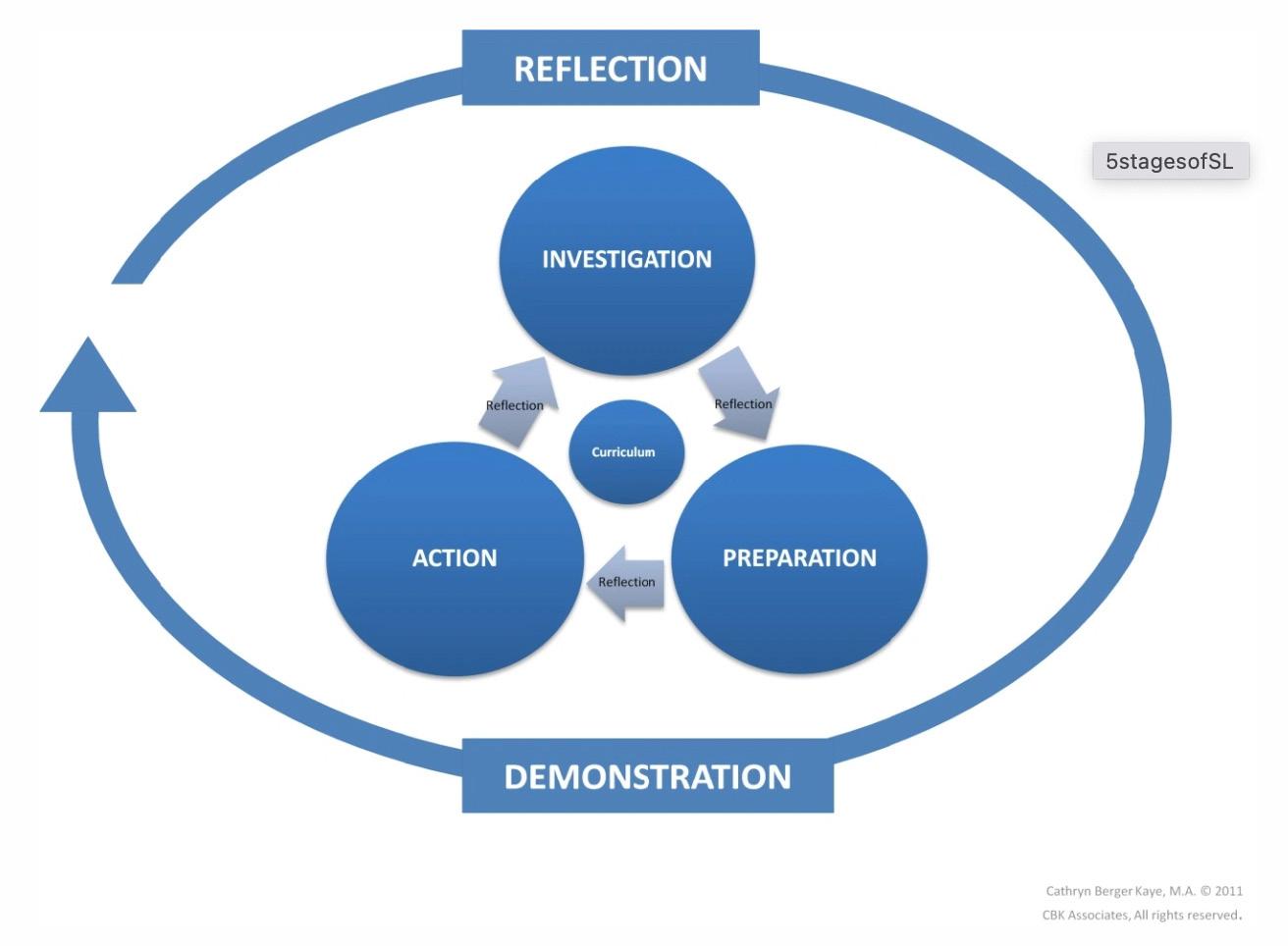

Service Learning

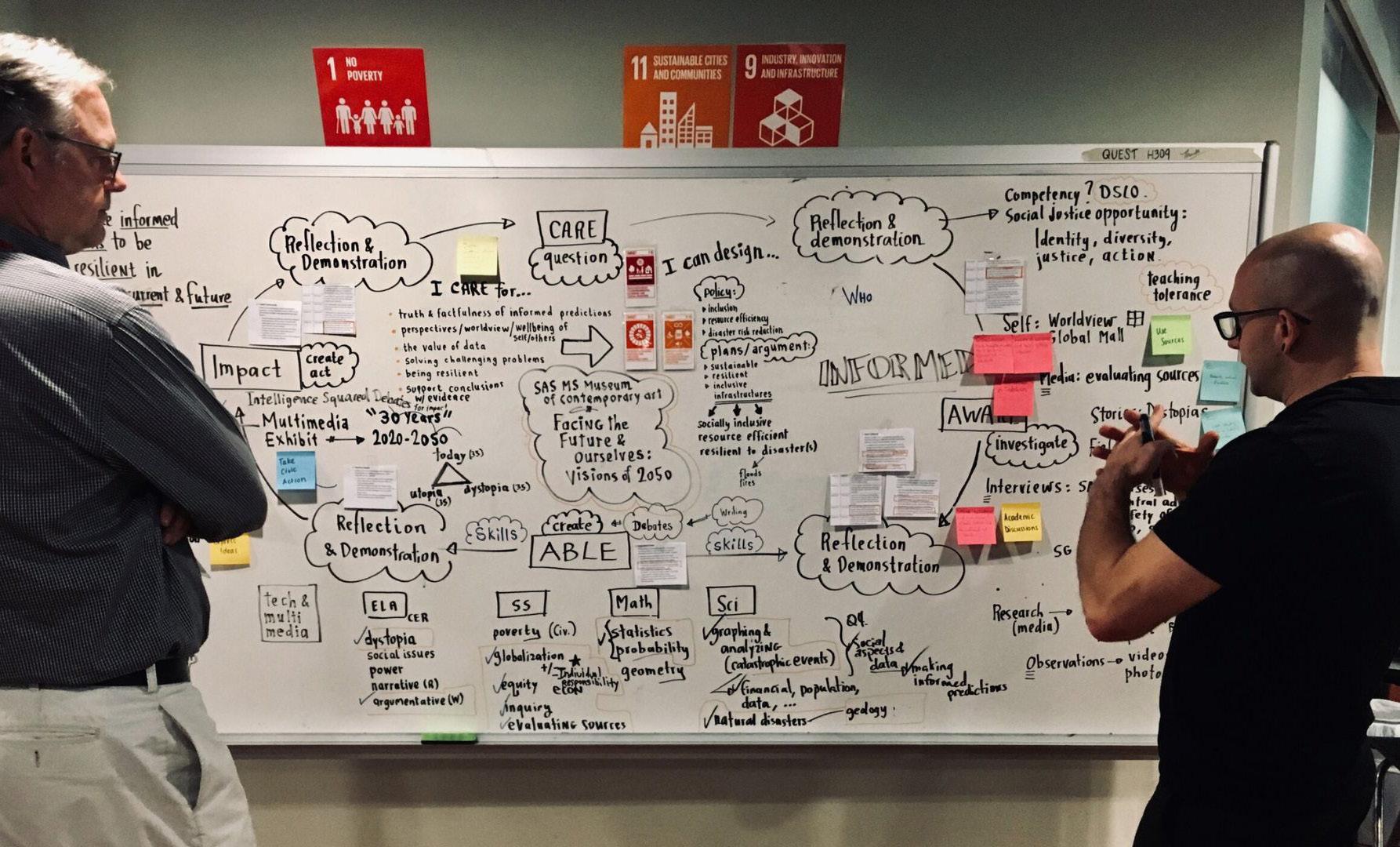

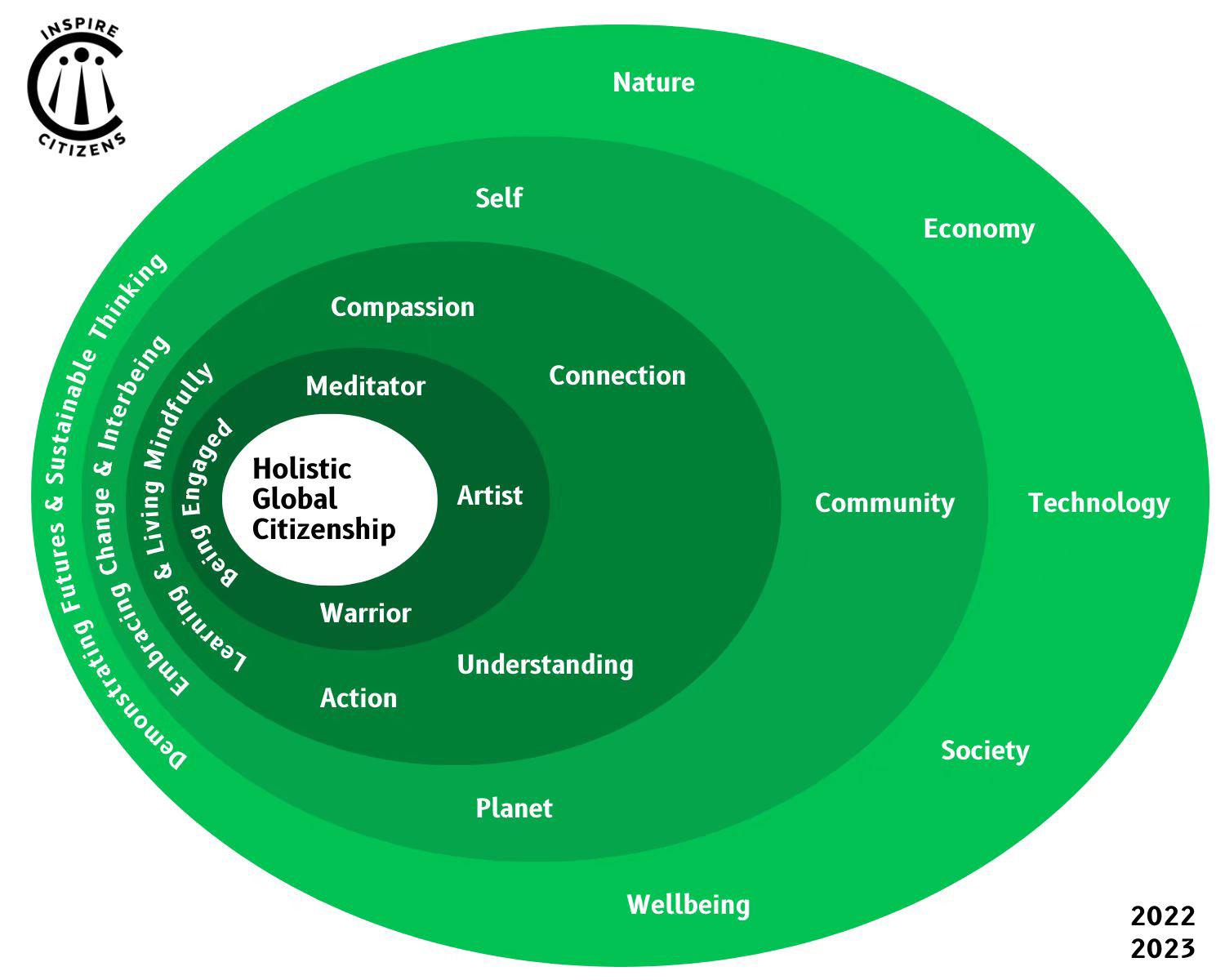

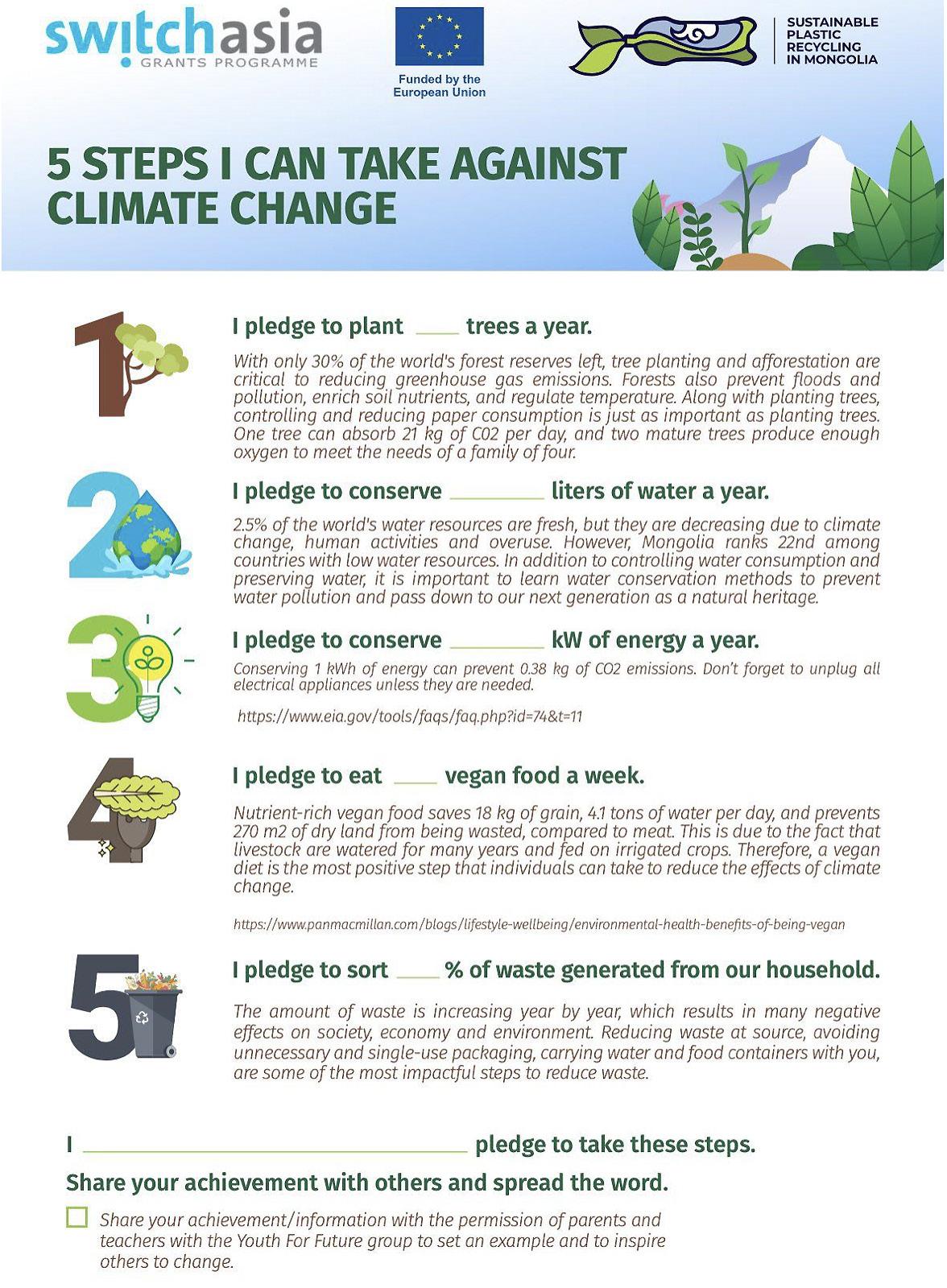

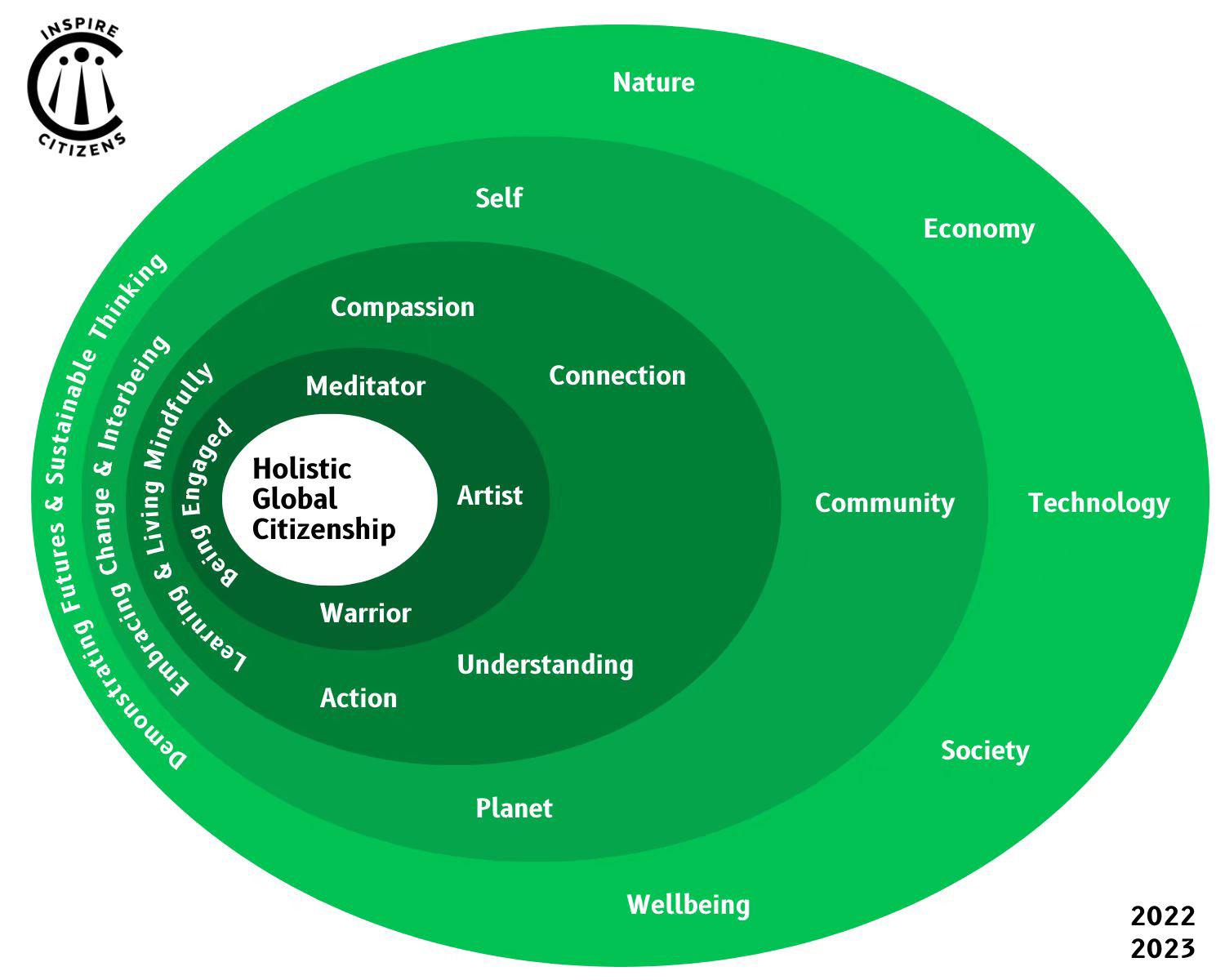

- Inspire Citizens: Whole School Models for Global Citizenship Transformation

- Christian Academy in Japan

- Building a Bridge Across Borderlands

- Need Journals: A Tool For Seeding the Service Learning Cycle

- Grade 3 Service Trips: Developing “pitch-in” attitudes and an appreciation for the natural world

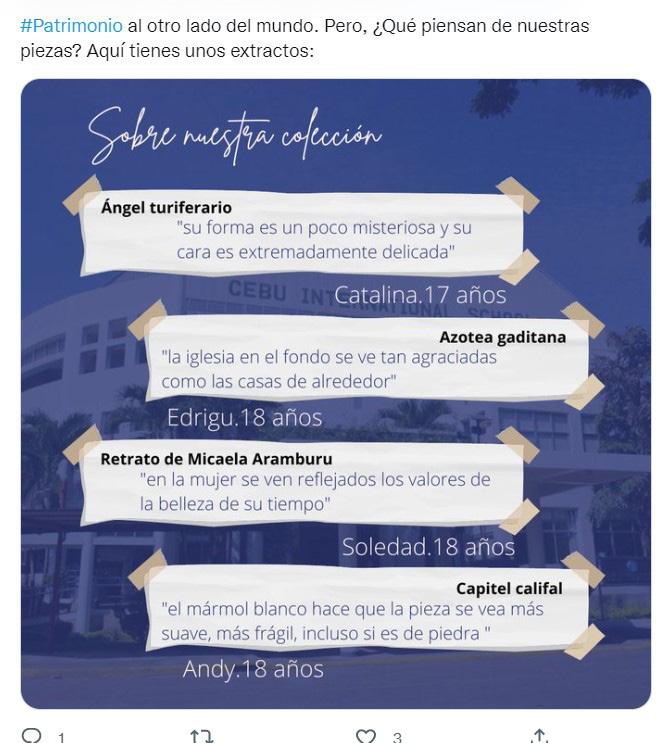

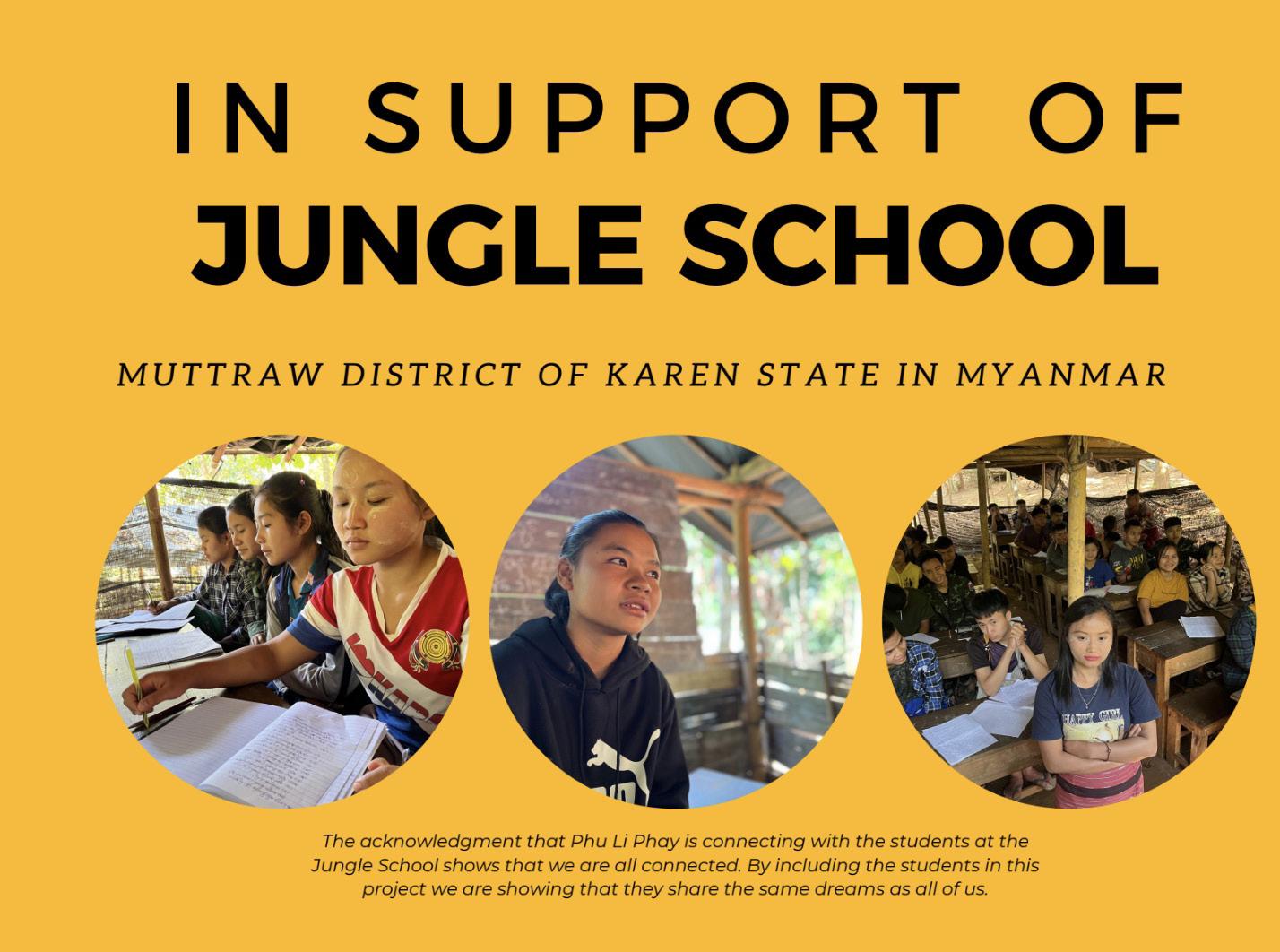

- Developing Partnerships: from Local to Global

66 Building a Bibliography of Our Schools

68

69

Green & Sustainable: Composting at The International School of Yangon (ISY)

Global Citizen Community Service Grant

- Go Green

- Made to Change: Obstacles to Opportunities

69

Student Writing: Far Beyond Your Physical Borders

71 Action Research

- How Does Differentiated Instruction Enhance the Inclusiveness of Math Classrooms? —an Approach to Address Linguistic and Neuro-Diversity

- Student College Readiness: Empowering Students Futures

76 Poetry

77 Press Release

- International School of Busan, Green Flag Award

- SENIA celebrates 20 years

- Concordia Environmental Science students meet GIZ energy expert

81 Campus Development: Mont’Kiara New Futsal Court 82

Middle School Art Gallery

Winter 2023 Issue 1

Message from the Executive Director

Eye on the Prize

As educators, we carry an incredible responsibility for building bridges to the future. This is good work, important work, and it is best suited for those who are fueled by a deep sense of optimism. There are days, and I am sure you have them as well, when my optimism is threatened by a never-ending cycle of bad news. From hate crimes and inexplicable wars, to catastrophic climate events, to the horrors of poverty and starvation, to crimes against children, to ongoing threats to democracy and freedom--being hopeful about the future requires a huge dollop of optimism if not a spoonful of naivete. And yet, every so often something remarkable appears and you realize that, yes, there is an abundance of good in the world, and every reason to be hopeful.

I certainly felt that was the case last autumn when I was contacted about Rena Kawasaki, a 17-year-old student at EARCOS member school Osaka International School of Kwansei Gakuin. Ms. Kawasaki was awarded the Children’s International Peace Prize for 2022 for her groundbreaking work in the pursuit of a better world. (Please see the article on the following pages for more about this extraordinary story).

To be clear, the Children’s International Peace Prize is comparable in significance to the Nobel Peace Prize—but for young people. It is in the upper stratosphere when it comes to awards for people of any age. Past winners include an array of truly remarkable young people, including at least two who have become global household names—Greta Thunberg and Malala Yousafzai. Rena Kawasaki is in the very, very best of company! She was selected from a dynamic cohort of 175 applicants from 46 nations. When you consider just what so many young people are achieving in their efforts to address the challenges facing humanity, you cannot help but become filled with optimism and humility.

I know our readers will join me in congratulating and celebrating Rena’s achievements and the recognition she has received. We must also offer very special congratulations to her teacher and advisor, Jennifer Henbest de Calvillo—and to the Osaka International School of Kwansei Gakuin--for supporting Rena’s development and efforts. I would encourage you to take a moment to visit the website about her project, Earth Guardians Japan, which Rena founded when she was only 14 years old!

The acclaim that Rena has received reflects upon her family, her teachers and the culture of the school where she has learned and grown. It also reflects a growing commitment by schools across our region, to embrace the voices of the young people who grace our school communities. As the Netherlands-based KidsRights organization that sponsors the prize explains:

We ensure that children are being heard. Together with children, we ask global attention for their power as changemakers and children’s rights issues. Also, we empower children as positive and resilient changemakers. We act with children, amplifying and accelerating their actions in their communities and beyond.

Rena Kawasaki’s message to all of us in EARCOS is loud and clear: we must continue and expand ways to listen to the voices of our schools’ most valuable resources—our students—in their efforts to reshape the world—their world. Amid today’s turmoil and the steady stream of discouraging news, the voices of our students, and their vision of what is possible, are indeed sweet, sweet music.

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

2 EARCOS Triannual Journal

TEACHERS' CONFERENCE 2023 M A R C H 2 3 - 2 5 , 2 0 2 3 S U T E R A H A R B O U R H O T E L K O T A K I N A B A L U , M A L A Y S I A V i s i t w w w . e a r c o s . o r g / e t c 2 0 2 3 1 8 t h A N N U A L E A R C O S STRANDS Literacy / Reading ESL Early Childhood Technology Special Needs Children's Authors Modern Languages Child Protection Counselors General Education Media Technology/Libraries

CEO

Zero

Michelle

Winner Creator and CEO of Social Thinking

Author of Teaching Life Save the date

Cathy

Jennifer

Klein

Ramirez

HT E M E : C REATING A CU L T U RE OFCARE

|

| Poet | Advocate

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Nicholas Carlisle

for

Bully

Garcia

Todd Shy

GUEST SPEAKERS Susie Boss Greg Curtis Sarah Park Dahlen Stephen Holmes Lee Ann Jung

Berger Kaye

D.

Lori Langer de

Russell Lehmann Marc Tyler Nobleman Jon Nordmeyer Stephen Shore Ying Chu & Huali Xiong Matt Harris & Sian Jorgensen

Russell Lehmann Speaker

Writer

PRESS RELEASE

EARCOS Student

Awarded 2022 Children’s International Peace Prize: What we dream–

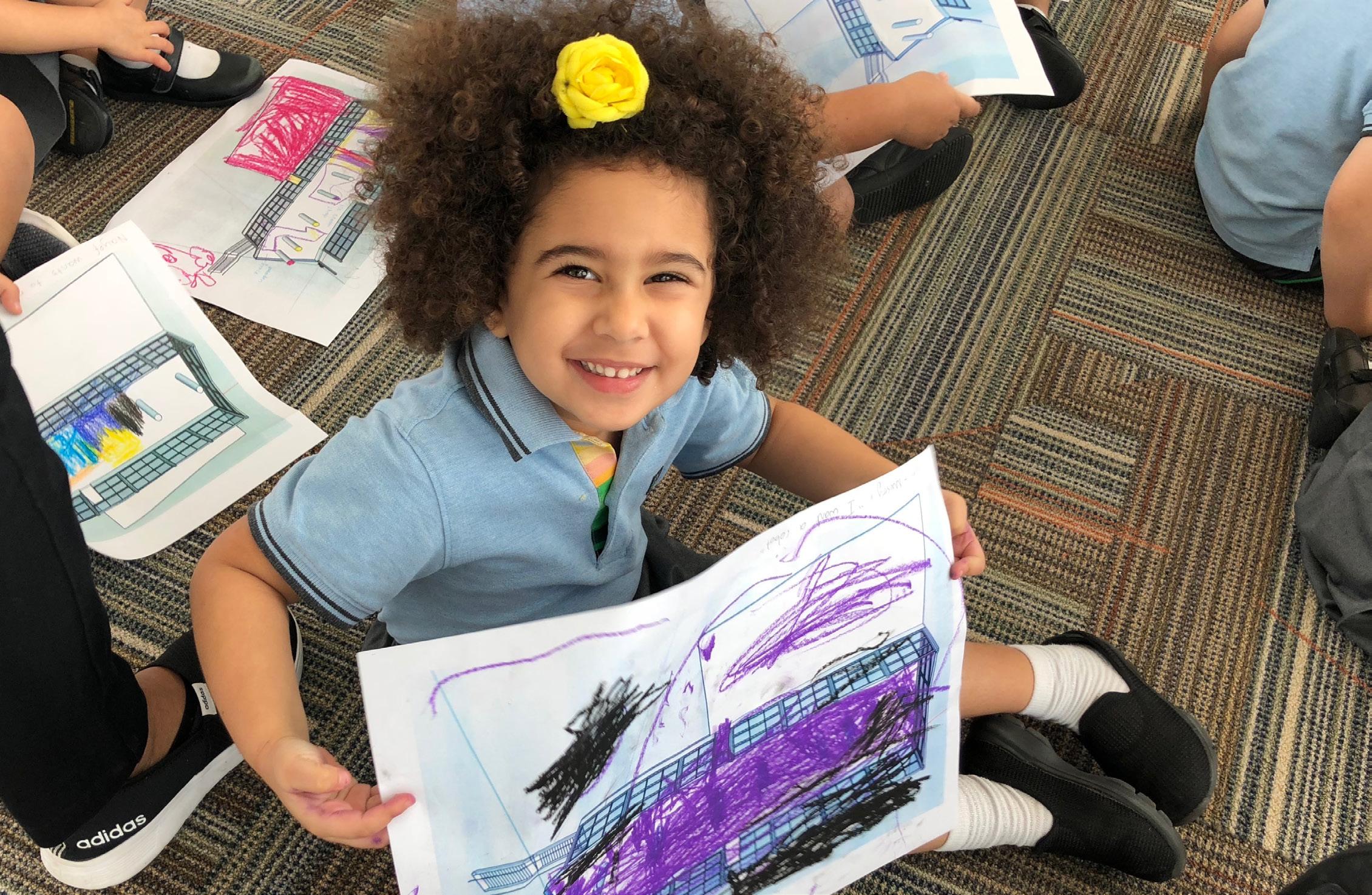

As educators we hope to see connections in learning, service and leadership grow in all our students as they mature. We might ask our students to reflect on: What their learning is for? How do they learn to be better people through their education? How do they find ways to access all areas of the curriculum? How do they find their passion and use this passion to help others? How do educators, schools and communities help them stand up and have a voice, to speak for what is right? How do they know what is fundamentally right? How can they dream for a better future and take action in this world?

Rena Kawasaki is a young girl of 17, who answered these questions and lives her dreams through action.

By Jennifer Henbest de Calvillo

She has been at our international school (Osaka International School of Kwansei Gakuin) since Kindergarten. Throughout her education she has proved what action and service can do to get youth involved in public service and improve the lives of future generations. She is an advocate for the voiceless and a role model to jumpstart youth action in Japan and internationally. We saw her on several TV programs, watched her become Euglena’s youngest ever CFO (Chief Future Officer) a leading youth advocate for a bio-fuel company in Japan. She has worked with Youth Summits, Polichats, University political groups. She is precocious, inclusive and a hardworking leader for U18 and “Let’s Talk to a Politician”. She is a recent winner of the prestigious Rise scholarship (run by Rhodes Trust and Schmidt Futures).

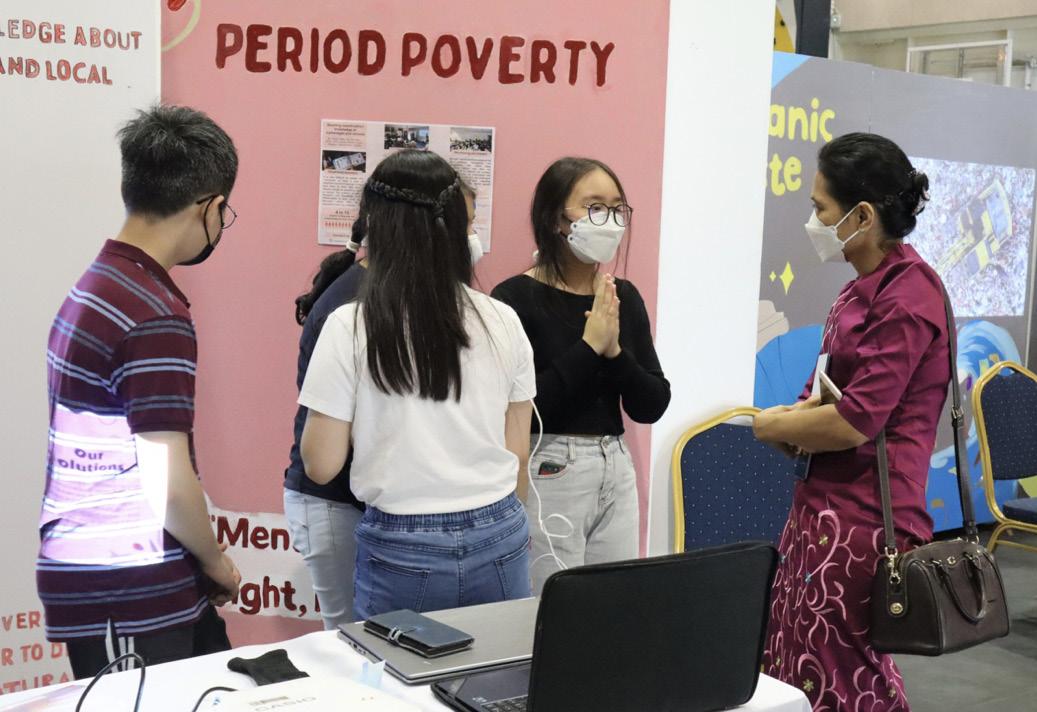

Rena and her friend Tanishka Murthy started Earth Guardians Japan, an organization that created connections regionally and internationally connecting kids in conversations about what they want to see happen in the world. One of the ways this was achieved was by connecting schools and local political representatives through virtual meetings. Earth Guardians used online platforms to help kids to connect and encouraged young Japanese to become more involved in politics, having a more direct say in their future through government interaction. Rena is officially working with the Japanese

when we think of a better future.

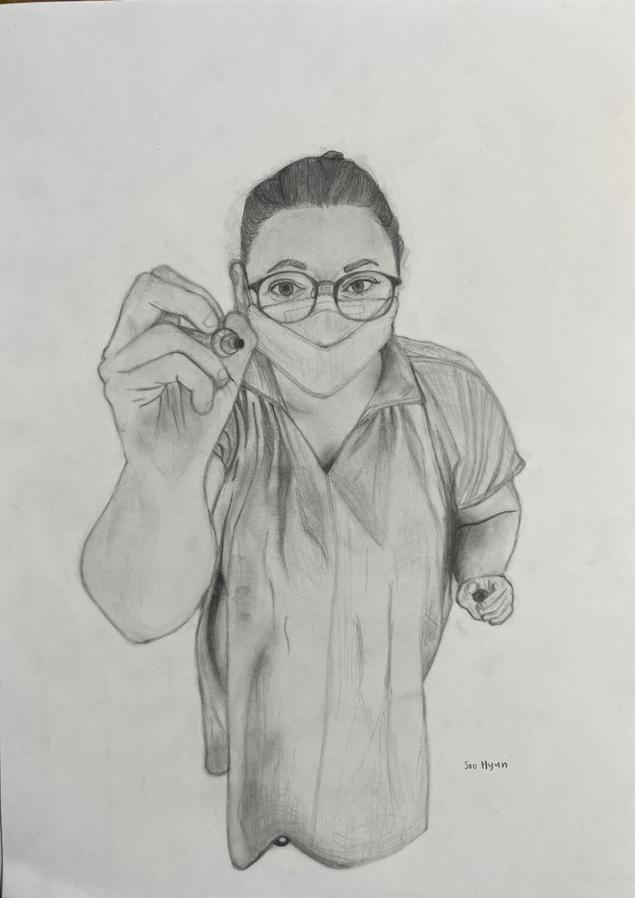

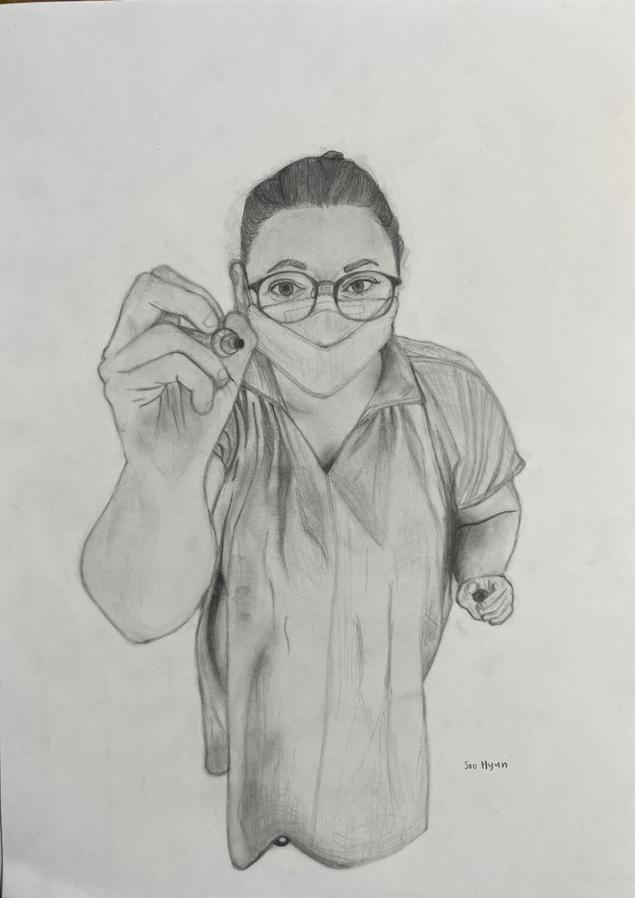

KidsRights director, previous winners Nav Agarwal, Tawakkol Karman, Rena Kawasaki, Netherlands Princess, previous winner Chaeli, and Tutu’s daughter.

4 EARCOS Triannual Journal

government ministry of environment to include the voice of young people in governmental operations. Tokyo’s government approached her to advise their team on reforming the city to be more sustainable.

This has led to her inclusion within the government’s major Tokyo Bay Environmental Social Governance infrastructure project. Rena is now working on the Tokyo eSG Project, which looks for future urban development aimed at creating a sustainable city. The future of Tokyo must combine nature and convenience projecting into the next 100 years. This will affect over 37 million people in the region. Rena also participated in the ‘Niihama project’, where she collaborated and created a QR code that would ensure that younger people’s voices are incorporated into government ideas. This was adopted by the Mayor and will impact the entire population of the city of Niihama. Rena’s ultimate goal is not only to ensure her generation has better opportunities, but that future generations have them too.

Rena recently won the esteemed International Children’s Peace Prize in the Netherlands. One could compare it to getting a Nobel peace prize for children. The prize was launched by KidsRights during the 2005 World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Rome, chaired by Mikhail Gorbachev. Since then, the prize has been presented annually by a Nobel Peace Laureate.

It comes with large prize money 100,000 euros to be used for her self directed projects, and a scholarship fund for herself and her siblings. Rena, her family and me (as the educator who nominated her) were flown to The Hague for the ceremony. Not only did she meet previous prize winners like Nav Agarwal And Chaeli Mycroft and their families but we had the opportunity to talk about One Step Greener founded by Nav and his brother Vihaan and receive a copy of Chaeli’s new book “Unapologetically Able”. Rena had the opportunity to meet and speak with the princess of the Netherlands and Desmond Tutu’s daughter as

the head of the Tutu scholarship fund. Rena also had the distinct honor to be handed the prize by Nobel Laureate Tawakkol Karman

The KidsRights Expert Committee selected Rena as a winner from 175 nominations with entries from 46 countries world wide. Rena has gained an important platform through which she encourages youth to speak and have a voice for public service. She inspires young people in Japan and across the planet to be risk takers and stand up for what they believe could help others in the future.

At our school we start educating about kids rights and the rights of the child in our PYP program in Grade 3/4. Rena is an advocate for right number

12. Children have the right to give their opinions freely on issues that affect them. Adults should listen and take children seriously. The Rights of the Child are an integral part of our curriculum and many other international schools in the EARCOS region. Our schools are filled with changemakers like Rena who thrive with support and numerous opportunities that educators can help provide.

During the filming for the Children’s International Peace Prize, Rena spoke eloquently about her cooperative adventure. She spoke about working together with various groups in her journey to change society for the better. One of Rena”s outstanding gifts is her ability to work in new collaborative groups. She spoke how none of this could be done alone. Her determination and ability to inspire youth in Japan has resulted in her being a spokesperson for youth all around the world.

Marc Dullaert, Founder and Chair of the KidsRights Foundation said: “Rena is an extraordinary pioneer in her country, ensuring the voices of young people are heard and converting this into tangible impact and better opportunities for both her generation and future generations. Education and the environment are of paramount importance to Rena and are topics she sets high on the agenda, in a unique way, in her society and globally.”

The International Children’s Peace Prize highlights the remarkable achievements of youth fighting bravely for children’s rights across the world. Previous winners include March for our Lives Initiators, Malala Yousafzai and Greta Thunberg. Kids Rights also has a board called State of Youth, and opportunities for clubs and organizations through a chapter of young people to apply for grants and work towards their dreams.

You can nominate someone in your school for the Children’s International Peace Prize until March 1, 2023.

As educators we can facilitate, support and encourage our students to take action for a better world. Our future depends on us working and acting together.

Winter 2023 Issue 5

Rena Kawasaki recipient of the 2022 International Children’s Peace Prize with Jennifer Henbest de Calvillo.

The 52nd EARCOS Leadership Conference, ELC, seemed a long time coming. The planning began in 2019 for 2020, and then again for 2021. The delay of course was due to the Covid pandemic. Then finally, with the theme of “Together Again”, the 52nd ELC became a reality from October 26-29 at the beautiful Shangri-La Hotel in Bangkok, Thailand. This year’s conference hosted 860 school board trustees, heads of school, principals, directors of learning, athletic directors, business managers, admissions officers, and Associate members from the EARCOS region and worldwide.

EARCOS Leadership Conference 2022

“Together Again”

By Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Each day of the conference opened with a plenary session highlighted by a keynote talk by an outstanding educational thinker and practitioner. The opening day also included an additional afternoon keynote. Dr. Michael Thompson, noted author and school psychologist opened day one sharing his experiences working with adolescent boys. Julie Jungalwala and Julie Stern shared their expertise during the afternoon keynote of day one. Tim Jarvis, who retraced a portion of Earnest Shackleton’s heroic escape from Antarctica stressed the role of endurance in all that we endeavor led off the second day. Our day three keynote was presented by Homa Tavangar, author of Growing

Up Global. She shared her strategies for surviving and thriving as global learners.

In addition to the exceptional keynote speakers, the 3-day conference offered over 140 workshop sessions on board governance, intercultural leadership, child protection, assessment, curriculum, DEIJ, admissions and marketing, and school change. The conference provided excellent learning experiences and abundant opportunities for networking. Both the opening night reception and the closing reception were well attended. The food, as always, was superb, the band was terrific, and the camaraderie was special.

During the Annual General Meeting (AGM), five new members were elected to the Board of Trustees to replace retiring and term-limited trustees. Newly elected members are Dr. James Dalziel, NIST International School, Thailand, Karrie Dietz, Stamford American School, Hong Kong, Gerald Donovan, North Jakarta Intercultural School, Indonesia, Dr.Jim Gerhard, Seoul International School, Korea, and Dr. Greg Hedger, International School Yangon, Myanmar. Those leaving the board in April are Andy Davies, President, Steve Cathers, Vice President, Saburo Kagei, Secretary, Laurie McLellan, and Barry Sutherland.

6 EARCOS Triannual Journal

We applaud these retiring trustees for their outstanding leadership and guidance during their terms.

Once again the staff of the Shangri-La treated our delegates as VIPs. Our sincere thanks go to Urasa Nicrothanon and her people for their outstanding service and hospitality.

Thank you to all those who attended ELC 2022. We invite you to join us again next year when ELC 2023 will be held once again at the lovely Shangri-La Hotel, Bangkok, from October 26-28, 2023.

Winter 2023 Issue 7

EDTHOUGHT Can we, please, shelve the traditional strategic plan now?

By Greg Curtis Author and Consultant

Picture walking into your school, picking up the thick, dusty binder marked “Strategic Plan: 2018- 2023”, leafing through its ponderous pages and muttering, “Yup, nailed it!” Tough to imagine, isn’t it?

Our traditional way of operating, at a strategic level, has not had a significant positive effect on learning. The efforts that have gone into change initiatives have not, by and large, been commensurate with the expectations of real change in the classroom. We have been very busy, but the effects are often underwhelming. (Curtis, 2018)

I won’t spend a lot of time outlining the reasons why traditional, static strategic plans are not helpful tools . . . most of us know this by now. They tend to keep schools and its people very busy, even if in isolated bursts. But we should not confuse busyness with progress. In fact, busyness is often the enemy of meaningful progress.

Also, they become painfully dated very quickly. As Henry Mintzburg wrote almost 30 years ago, traditional strategic planning falls prey to “the Fallacy of Prediction”.

According to the premises of strategic planning, the world is supposed to hold still while a plan is being developed and then stay on the predicted course while that plan is being implemented. (Mintzberg, 1994)

This “Phallacy of Prediction” is something that Mintzburg and others have expressed frequently. If there is one thing that the past 3 years have brought into stark relief, it’s that we truly are living in a VUCA world (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous). It’s not just a buzzword. Are our traditional strategic plans equipped to handle this? Have they ever been?

The purpose of this article is not to simply malign the traditional strategic plan; they have been falling out of favour in the business and educational sectors for quite a long time. However, some schools may be happy with their traditional strategic plans and that’s great. The purpose of this article is not to tear down “the old plan”, but to investigate a more agile, future-focused, and on-going process.

I would like to explore an alternative move to “rolling” strategic thinking and agile planning as an alternative. As Mintzberg also states, “Strategic planning isn’t strategic thinking. One is analysis, and the other is synthesis.” (Mintzberg, 1994). Strategic thinking is at the heart of the shift from fixed plans to “rolling” strategic processes.

10 EARCOS Triannual Journal

A Strategic plan . . . Strategic thinking . . .

Is a product Is a process

Is completed as a task, whether isolated or participatory Is initiated as part of a larger shift towards engagement, a future focus and ideation

Seeks to define, delineate and “freeze” everything in one place

Is usually assessed as to whether the boxes have been checked and all of the actions contained carried out

Is usually spearheaded by committees who work to carry out implementation plans

Is seldom truly strategic, with many operational issues mixed in

Seeks to be a catalyst for ongoing engagement in thoughtful and iterative exploration and design

Is usually assessed as to whether clear mission-critical learning goals and desired transformations are being achieved

Is usually guided by design teams seeking ways to effectively achieve learning goals in a modern and fluid context

Is always strategic if the focus remains on the achievement of mission-critical goals for learning and, thereby, achievement of mission

Rarely, if ever, changes over its life span Is always being developed and, by definition, is agile

Usually focuses on fixing perceived deficits in past or current practice

Is future-focused and directed towards creating new solutions and opportunities

In order for a rolling strategic process to have a positive transformative effect, it is helpful to keep the following characteristics in mind.

Create “future first” mindset and process

• Most traditional strategic planning processes begin with a close analysis of the present state of the organization. Perhaps a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) may explore the surrounding landscape somewhat, but we usually begin our process firmly rooted in the present as if everything was going to remain the same in the future. We often use the strategic planning process as a way to “fix” that which we currently judge as “broken”. This is all rear-view mirror stuff.

• Strategic thinking should begin not with an analysis of where we are, but an inquiry into where the world of our students may be headed. We need to build a knowledge base about the potential future they will inhabit, through processes such as Futures Thinking, to better understand what we need to do to help them to thrive and contribute in their lives. We need to envision a desired destination years ahead to set our sights on the real goal . . . only then can we look at where we currently are and design ways to move from the present towards the future.

Anchor long-term strategic thinking in concrete and stable strategic goals for learning

• Fixed-term strategic plans tend to be static. Once they are written, they are rarely revised based on progress and appropriate evidence with a frequency that would be considered “agile”.

• A rolling strategic process needs to be anchored in long-term goals for learning. These are usually identified through Futures

Thinking processes (see above) and consolidated into a desired future destination for the community. This helps to keep us from jumping to the how without clarity on the what, a flaw I often see lead to untethered and unproductive busyness in schools.

Focus on Impacts, not Inputs and Outputs

• My Input-Output-Impactô framework is an attempt to help differentiated between means and ends.

The Input-Output-Impactô Framework (Curtis, 2016)

• The traditional strategic plan tends to focus on Inputs and Outputs, often without a clear connection to what these are designed to achieve (our mission through Impacts). Without goal clarity, how can we design appropriate responses to achieve them? How will we know if we have been successful? Static strategic plans trap us in a seemingly never-ending Input-Output loop, often without achieving anything truly important.

• Often, a traditional strategic plan measures its success against itself – Did we do all of the things we said we would do? This is simply a measure of implementation, not the a measure of the achievement of strategic goal.

We may measure inputs and outputs by the completion of action steps and implementation plans. The achievement of desired impacts, however, should be evidenced through the artifacts and products of student learning. The measure of success is not that we did the work, but that students learned and can demonstrate their growth and achievement related to stated Impacts. (Curtis, 2018)

Initiate processes that are highly participatory and lead to desired shifts

in culture

• Strategic plans are usually devised through a contained and fixed process over a relatively short timeframe (picture the “strategic planning committee retreat”, if you will). Everything decided via this limited process then becomes fixed and is usually passed on to various committees to implement, often in isolation.

• Strategic thinking is on-going and engages multiple groups in designing the best systems and solutions in order to achieve the desired destination for its students. The process is iterative and cyclical, giving many opportunities for real engagement

Winter 2023 Issue 11

and contribution. It is not a document handed to committees, but more of a relay race where the baton is passed to various collaborative teams at various times to carry for a lap of on on-going journey.

Engaging productively with Complexity

• Dated methods of strategic planning treat the future as if it were linked to the present through logical, linear relationships. “If we simply do A, B and C, then D will result.” However, the future does not unfold in a linear process. Traditional plans also often overlook culture as an important element to cultivate in order to achieve success. Most of us will have experienced the fall-out from neglecting culture at some point in our careers.

• Schools are complex ecosystems made up of many interacting systems. As such, linear causality should not be relied upon. Complex environments are nonlinear and require a different way of thinking to help ensure that the desired changes come to the surface as “emergent properties”. A rolling process is more attuned to complexity and better suited to massaging various elements of the overall complex environment, including culture, to help bring about desired change.

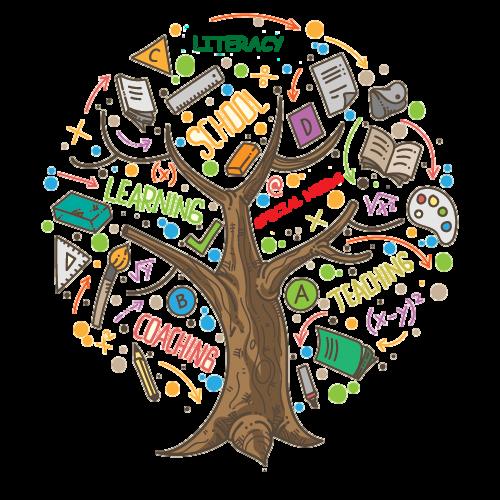

Initiate

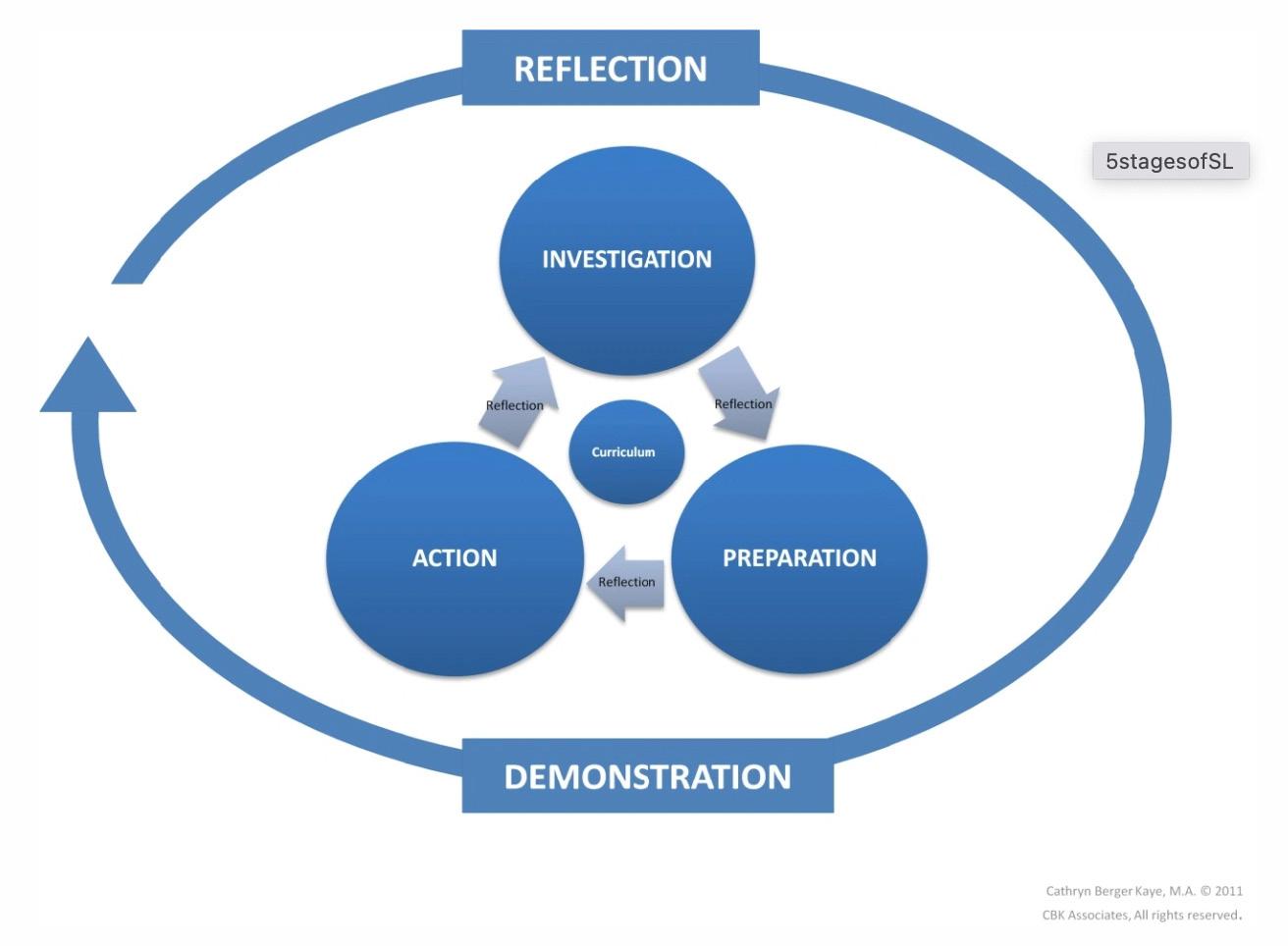

and sustain a cyclical process

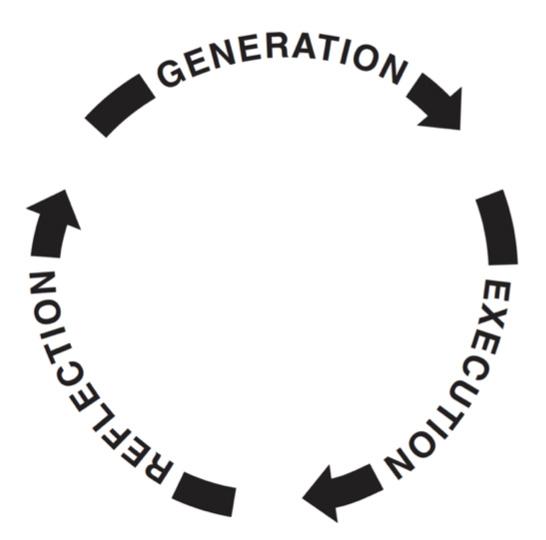

• Rolling strategic processes are not one-time events. They epitomize a new way for the organization to engage and function in an on-going and iterative manner. It requires a cyclical process to keep things moving in productive and consistent ways. Below is a simple illustration of such a cycle.

future design and implementation efforts. Finally, a true reflection stage, based in the interpretation of appropriate evidence, allows us to keep learning and refining.

Guided by process roadmaps

• While dealing with adaptive strategies in complex environments may not be linear, we still need to establish stages and benchmarks within the process. Whereas traditional plans often deal with each initiative as an isolated set of tasks, rolling processes need to function with multiple processes happening simultaneously and across different systems or workstreams.

• Roadmapping provides a way to orchestrate the Inputs and Outputs of different teams across different projects at various stages of the rolling cycle. It helps us to be more strategic in our thinking and to connect the dots across various teams, projects, and phases. It is a “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” scenario.

Most educators understand that traditional, fixed-term strategic plans are not adequate to help schools truly move forward in agile and resilient ways. And yet, many struggle to accept an alternative to the static plan while continuing to follow at model that is flawed and hoping for the best. This is a large topic to address in a relatively brief article. I hope these thoughts helped to introduce some concrete ways in which strategic thinking and rolling strategic process differ and can support on-going improvement now and for our future.

Sources

Curtis, G. (2018). Moving beyond busy: Focusing School change on why, what, and how. Solution Tree Press.

McTighe, J., & Curtis, G. (2018). Leading modern learning: A blueprint for Vision-Driven Schools, Second Edition. Solution Tree Press and ASCD.

Mintzberg, H. (2014, August 1). The fall and rise of Strategic Planning. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://hbr.org/1994/01/the-fall-and-rise-of-strategic-planning

Sample of a Rolling Strategic Process (Curtis, 2018)

• The advantage of such a cycle is that various design processes and initiatives can exist at various stages of the process. Each stage has its own characteristics, goals, and processes. This helps to tie things together and keep our thinking, design, and implementation agile. It also allows us to learn from experience and allow this collective experience to influence current and

About the Author

Greg Curtis is an author and consultant collaborating with schools on school change efforts including strategic processes. He can be reached at Greg@gregcurtis-consulting.ca

The Power of Digital Storytelling

Presented by: LeeAnne Lavender Saturday, January 28, 2023 9:00 - 10:00 AM HKT visit website

12 EARCOS Triannual Journal

• Start and manage a school

• Supply a school

• Recruit teachers

• Recruit school leaders

• Streamline accounting and finance functions

• Learn through professional development (PD)

• Support diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ)

full

International

See where ISS can take you and your school

International Schools Services (ISS) provides you with the

range of services necessary to deliver an outstanding global education: Explore upcoming job fair and PD opportunities at ISS.edu/events Find more at ISS.edu #ISSedu

Winter 2023 Issue 13

Getting Started as an Instructional Coach

By Kim Cofino

In a previous article I shared big picture visioning steps to build a thriving coaching program at your school. Having those long term plans in place to develop a coaching program is the first step, but once you are hired as a coach, and once you have coaches in your school community, how do you start making those plans into reality?

Over the past eight years of working with coaches and school leaders to develop coaching programs in schools around the world, the number one question I get asked is: “Now that I have the job, how do I get started as a coach? Where do I start? What do I do to begin to build a coaching culture? And how can I make an impact as just one coach in a school?”

When making the transition from a classroom role to a coaching role, there are so many different new responsibilities, and you need to transition your perspective from the micro view of one classroom or department to a whole division or whole school. Although you’re still focusing on improving student learning, you’re now looking at it through the lens of teacher professional growth.

In my work with coaches in The Coach Certificate and Mentorship Program (and based on my own personal experience as a coach for over a decade in international schools), I have found that the following 10 steps will start the ball rolling and enable you to see where you’re able to make the biggest impact so you can adapt, adjust and refine from there. This is not the only way to get started, but it’s worked for many coaches, and if you’re feeling like something is not moving in the right direction, you may find that you need to bring in one of these elements.

Step 1: Focus on building relationships Relationships are the foundation of everything: build them with teachers, with your school leaders, with support staff, with department heads. When you move into a coaching role, you no longer have the luxury of “only” working with the people on your team or in your department. As a coach, you need to think about how you will connect with all stakeholders in the school community. Being proactive and strategic about how you build these relationships, document the conversations and connections that you have, and continue to cultivate them is essential.

So many future coaching cycles, or great parent connections, or new school initiatives can begin because you spent time cultivating relationships with all stakeholders. As Joellen Killion says: “All models of coaching are valuable. Coaching light is coaching for relationships. Coaching heavy is coaching for results. Results can build relationships just as relationships can build results.” (Cofino, 2020)

Step 2: Be intentional about being visible

It can be easy for teachers to develop a perception that coaching is a “desk job” or “mini admin”. To counteract that misconception, be intentional about being visible. Be where teachers are: in their classrooms, on duty, in the staff lounge, the lunch room, in team meetings (if you can). Help them see that you’re part of the school community every day. This will go a long way towards building relationships as well.

EDTHOUGHT

14 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Recently presented at the EARCOS Leadership Conference 2022 in Bangkok, Thailand

With my clients in The Coach Certificate and Mentorship Program

we often talk about specific strategies to be intentional with your time to ensure that visibility is structured into your day as a coach. Focusing on a small strategy like this can have a big impact (as my own coach often says “small hinges open big doors”).

Step 3: Make a mindset shift

One of the potentially challenging parts of becoming a coach is realizing that you were not hired to create “mini me’s”. Even if you are an expert in your field and you were doing amazing things in your classroom prior to becoming a coach, the goal is not to create an “army of you” (sorry, Bjork). Coaching is about listening & supporting others growth (not “fixing” or making everyone just like you.

The beautiful thing about making this mindshift is that you’re no longer hung up on the outcome of coaching conversations. You are walking the path with the teacher, but you don’t need to be personally invested in the specific journey it takes to get there (as long as student and teacher safety are assured). You can be a thought-partner and an idea inspirer without holding attachment to which ideas get adopted. This is about teacher growth not compliance.

Step 4: Take time to articulate your vision or philosophy

Because we all have our own preconceived notions of what coaching means, it’s essential to define what it means in this context, for this school, at this point in time. Taking the time to clarify what your vision for coaching is will help you not only align with your school leader, but also be consistent in your communication with coachees.

Once you have your own vision clarified, clearly define your role & align with your school leader so you’re both working towards (and expecting) the same outcomes. In my work with coaches and school leaders around the world, the majority of any potential issues with coaches or a coaching program stems from a lack of clarity around the role, it’s intention, purpose and expectations. If you can come to alignment early on with your school leaders, you will prevent much of those potential “downstream” challenges.

To quote my coaching superhero, Joellen Killion again: “If I can describe it with specificity, it is far more likely to be achieved, than if I don’t have the capacity to be specific. More time on the what what what, and less time on the how. We do that backwards in schools. We spend a lot of time on the how without clarity on the what.” (Cofino, 2022).

Step 5: Use a needs assessment to determine your services

As coaches, we likely have ideas for the kind of support we would like to provide teachers. However, you’re far more likely to see teachers coming to you for coaching if you start by uncovering exactly what they think they need support with, as well as the language they use to describe it.

When you start communicating your services to teachers, be sure to include the outcome of the needs assessment so that you are directly targeting your teacher’s perceived needs. You can always include more than what they identified, but when you give teachers what they ask for, they will be more likely to seek you out for support.

Another advantage of conducting a needs assessment first is that

you will be able to tell how teachers describe the support they would like. As a coach, you may have more specific language to describe the work you do, but if this vocabulary isn’t how teachers describe it, they might not recognize it as the support they feel they need.

In my work with the Phoenixville Area School District in the US, conducting a needs assessment was a huge turning point for their coaching program. Several years later, their team has since doubled in size and their coaching program is flourishing. As K12 Instructional Coach, Ashley Martin, mentioned on a #coachbetter podcast conversation with me: “It’s been amazing to think back to where it started and to see the layers adding on as we grew. It all started with the needs assessment that we did with you in The Coach.” (Cofino, 2020)

Aligning your services and language to what teachers recognize they need, and how they describe it, is the first step in helping teachers see working with you as a valuable investment of their time.

Step 6: Actively & consistently communicate your role Once you know what teachers believe they need, you can create a coaching menu to communicate your services, in the language of your teachers. Many coaches change up their coaching menu on a regular basis to help teachers recognize all the different valuable services they provide. The key here is to consistently communicate your role to your teachers as regularly as you can (without overwhelming them).

Teachers are busy, and they may not see the value of investing their time in coaching unless they can clearly see how that time will be spent, and that there will be a tangible positive impact in their classroom. The more you can do to provide clarity around the work you do, the easier it is for teachers to “say yes” to coaching.

Step 7: Recognize that not everyone is ready for coaching (yet) As much as you may want to work with every teacher, or any specific teacher, coaching is an invitational practice. Compulsory coaching usually does not work out well. As a coach, your goal should be to create an environment where teachers feel comfortable and invested in their professional growth, so there is a willingness to take risks, try new things and invite someone else into their classroom.

As Diane Sweeny said in her #coachbetter interview: “If we set goals for student learning, we’re sending a message that I’m here to be a partner. The type of goal you start with can really mitigate against reluctance. It can’t be an external agenda put on a teacher by someone else.” (Cofino, 2020). Ultimately, coaching requires vulnerability, and vulnerability requires trust. Which is why this article started with building relationships first.

Step 8: Support teachers in sharing their successes

In order to spread the great work that coaching supports, it’s essential to both track the work that you’re doing and share it. However, not everyone likes to share, or to be celebrated publicly, it’s worth finding a variety of ways to celebrate the accomplishments of your coachees.

You may find that teachers appreciate being mentioned in your weekly newsletter or podcast, or that they prefer to speak for them-

Winter 2023 Issue 15

selves in a faculty meeting or on a PD day, or maybe just asking one coachee to connect with another teacher in the department to share their experience with you is just right. Develop a variety of strategies that work in your community to share success stories so you can build momentum around coaching.

Sharing also has a side benefit of helping teachers see that coaching is for everyone, and gives them specific people to talk to about their experiences coaching.The goal is that you, as the coach, are not the only person in the community talking about coaching and how impactful it can be.

Step 9: Seek feedback regularly & take action

In order to continually grow and improve, it’s important to seek feedback on your practice. There are many ways to collect this kind of data, you can:

• Conduct surveys (annually, and after specific events or experiences)

• Ask for feedback at the end of a coaching session (I like the question: “What was most helpful for you today?”)

• Touch base with department heads and other school leaders to see what they’re hearing

The key is, as Jordan Benedict said in our #coachbetter podcast conversation: “The goal with data is to start measuring and start taking action. The questions don’t have to be perfect at the start. You can fine tune your actions over time.” (Cofino, 2019). You only need one data point to move forward!

Step 10: Track your time & focus on what makes the most impact Along with tracking the work you’re doing in an effort to share coaching success, it’s important to track your time to help you focus on what type of work makes the most impact in your school community.

For most of my clients in The Coach, one of the key “aha moments” is understanding the different types of coaching (or coaching stances) that we can be doing. We follow Laura Lipton’s model of the Continuum of Practice: Consulting, Collaborating and Coaching (most other coaching researchers have a very similar breakdown, but with different labels), and most coaches can benefit from tracking the amount of time and impact based on the different stances they take.

As Laura said in our #coachbetter podcast conversation: “Colleagues want you to be consulting. In order to create commitment and ownership, it’s a dance. Don’t discount the value of the information of the consultant, because it is a resource. To transition to coaching, offer chunks of information with the opportunity to process.” (Cofino, 2020).

If you are aware of coaching stances, and tracking your time based

on the work that you do, you’ll be able to work towards transitioning your conversations to deeper coaching over time.

Bonus: Share coaching data

As you are tracking your time to measure your impact, make sure you’re also sharing this data with the wider school community & specifically school leadership. Because coaching is a non-teaching position, often with little to no classroom time, it is an easy position to cut. When things are going well, it can be harder to realize the impact that having a position like coaching can make. Be intentional about tracking and sharing this data with decision makes so they recognize the value you bring to the school community.

Working Towards Clarity & Consistency

Instructional coaching is a hugely valuable and influential position for schools, but it’s complicated and complex to get it right. Here in the EARCOS region, we see these positions come and go due to a lack of clarity and consistency in both vision and implementation. Hopefully these articles will start a dialogue about the positive impact coaching can have in our region so we can begin to see these positions have more longevity, along with clearer expectations and implementation. If you’re interested in being part of that conversation, please let me know!

References

Cofino, K. (Host). (2022, Jan 26). What Makes Coaching Work with Joellen Killion (146). [Audio podcast episode]. In #coachbetter. Eduro Learning. https://coachbetter.tv/episode-146/

Cofino, K. (Host). (2019, Aug 7). Measuring Your Impact as an Instructional Coach with Jordan Benedict (47). [Audio podcast episode]. In #coachbetter. Eduro Learning. https://coachbetter.tv/episode-47/

Cofino, K. (Host). (2022, Nov 2). Building an Intentional Coaching Program with the PASD Team (178). [Audio podcast episode]. In #coachbetter. Eduro Learning. https://coachbetter.tv/episode-178/

Cofino, K. (Host). (2022, Jan 12). How to Coach Reluctant Teachers with Diane Sweeney (144). [Audio podcast episode]. In #coachbetter. Eduro Learning. https://coachbetter.tv/episode-144/

Cofino, K. (Host). (2022, Feb 23). The Continuum of Practice for Instructional Coaches with Laura Lipton (150). [Audio podcast episode]. In #coachbetter. Eduro Learning. https://coachbetter.tv/episode-150/

About the Author

Kim Cofino recently presented at the EARCOS Leadership Conference 2022 in Bangkok, Thailand and at past Teachers’ Conferences. She can be contacted at mscofino@gmail.com

Can We Finally Shelve the “Strategic Plan”?

Presented by: Greg Curtis Saturday, February 4, 2023 9:00 AM HKT visit website

16 EARCOS Triannual Journal

inclusive leadership program

L E A D I N G F O R E Q U I T Y I N I N T E R N A T I O N A L S C H O O L S

P R O G R A M O V E R V I E W

T h e p u r p o s e o f t h i s 1 8 - m o n t h , E A R C O S - s p o n s o r e d p r o g r a m i s t o b u i l d d e e p u n d e r s t a n d i n g a n d s k i l l s i n t e a c h i n g a n e u r o d i v e r s e p o p u l a t i o n T h e i n t e n t i s f o r s c h o o l l e a d e r s a n d t e a c h e r l e a d e r s , i n t u r n , t o d e v e l o p s u c h s t r o n g f a c u l t y c a p a c i t y a n d c o l l e c t i v e s e l fe f f i c a c y i n t h e i r s c h o o l s t h a t t h e r e i s n o l o n g e r a q u e s t i o n o f w h e t h e r a w i d e r d i v e r s i t y o f n e e d s c a n b e m e t w i t h i n t h e s c h o o l

T h e p r o g r a m o f f e rs a s h a r e d u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f t h e p r a c t i c e s , s y s t e m s , a n d s t r u c t u r e s n e e d e d t o f a c i l i t a t e a s c h o o l c o m m u n i t y v i s i o n t h a t v a l u e s i n c l u s i o n a n d s e e s t h e b e n e f i t s f o r a l l s t u d e n t s T h e c o u r s e s c h a l l e n g e t h i n k i n g a r o u n d w h a t n e u r o d i v e r s i t y m e a n s a n d f a c u l t y i d e n t i t y a s i n c l u s i v e e d u c a t o r s . P a r t i c i p a n t s l e a r n t o d e v e l o p t i e r e d s y s t e m s o f s u p p o r t , i m p l e m e n t u n i v e r s a l d e s i g n f o r l e a r n i n g , d e s i g n i n t e r v e n t i o n , m ea s u r e p r o g r e s s , s u p p o r t m e t a c o g n i t i o n a n d e m o t i o n a l r e g u l a t i o n , a n d h o w t o c o a c h a n d l e a d i n c l u s i v e p r a c t i c e s .

W e w a n t p a r t i c i p a n t s t o l e a v e p r e p a r e d a n d e n t h u s i a s t i c t o l e a d s c h o o l s c o u r a g e o u s l y t o d e s i g n i n s t r u c t i o n " t o t h e e d g e s " i n a w a y t h a t e l e v a t e s o u t c o m e s f o r e v e r y s t u d e n t i n t h e s c h o o l . T h e g o a l o f i n c l u s i v e , u n i v e r s a l l y - d e s i g n e d s c h o o l s i s t o p r e p a r e n o t o n l y e x p e r t s i n c o n t e n t , b u t a l s o e x pe r t l e a r n e r s , w h o e n g a g e i n t e n t i o n a l l y i n l e a r n i n g , s e t t h e i r o w n g o a l s , a n d k n o w h o w t o t a k e c h a r g e o f t h e i r o w n l e a r n i n g - - i n s c h o o l , a n d i n l i f e b e y o n d s c h o o l .

D E L I V E R Y

E a c h c o u r s e i n c l u d e s a c o m b i n a t i o n o f l i v e f a c i l i t a t i o n a n d s e l fp a c e d , o n l i n e l e a r n i n g F o u r o f t h e c o u r s e s a r e h y b r i d , w i t h a p o r t i o n o f t h e c o u r s e t a u g h t i n p e r s o n a t a n E A R C O S c o n f e r e n c e o r a s a w e e k e n d w o r k s h o p . T h e r e m a i n i n g f o u r c o u r s e s a r e e n t i r e l y o n l i n e C o u r s e s c a n b e t a k e n i n d i v i d u a l l y , b u t r e g i s t r a t i o n p r e f e r e n c e i s g i v e n t o t h o s e e n r o l l i n g i n t h e f u l l p r o g r a m

M A S T E R ' S D E G R E E O P T I O N

P a r t i c i p a n t s c a n t a k e c o u r s e w o r k f o r p r o f e s s i o n a l d e v e l o p m e n t o n l y , o r f o r a M a s t e r o f A r t s i n T e a c h e r L e a d e r s h i p f r o m S a n D i e g o S t a t e U n i v e r s i t y M a s t e r ' s s t u d e n t s t a k e a n a d d i t i o n a l 3 c o u r s e s o n l i n e , a n d d e v e l o p a c a p s t o n e p o r t f o l i o ( i n l i e u o f a t h e s i s ) G r a d u a t i o n i s a t t h e c o n c l u s i o n o f t h e s u m m e r 2 0 2 4 s e m e s t e r .

T U I T I O N

T h e f e e f o r t h e p r o g r a m o f 8 c o u r s e s i s $ 5 2 0 0 f o r E A R C O S m e m b e r s , p a i d a t $ 6 5 0 p e r c o u r s e ( $ 7 5 0 f o r n o n - m e m b e r s ) T h e a d d i t i o n a l f e e f o r t h o s e i n t h e S D S U m a s t e r ' s p r o g r a m i s $ 6 , 3 7 8

S C H E D U L E

C O U R S E 1 : M a r c h 2 0 2 3 * U n i v e r s a l D e s i g n f o r L e a r n i n g - r e p e a t e d M a y 2 0 2 3 o n l i n e

C O U R S E 2 : J u n e 2 0 2 3 M u l t i - T i e r e d S y s t e m s o f S u p p o r t & R T I

C O U R S E 3 : J u l y 2 0 2 3 T e a m i n g w i t h F a m i l i e s

C O U R S E 4 : O c t o b e r 2 0 2 3 * M a s t e r y A s s e s s m e n t & G r a d i n g

C O U R S E 5 : J a n u a r y 2 0 2 4 * F r o m G o a l s t o G r o w t h

C O U R S E 6 : M a r c h 2 0 2 4 * C o m p a s s i o n a t e C l a s s r o o m s

C O U R S E 7 : M a y 2 0 2 4 C o a c h i n g & C o n s u l t a t i o n i n I n c l u s i v e S c h o o l s

C O U R S E 8 : J u n e 2 0 2 4 O r g a n i z a t i o n a l C h a n g e f o r E q u i t y & I n c l u s i o n

R E C O G N I T I O N : O c t o b e r 2 0 2 4 i n p e r s o n d u r i n g t h e E A R C O S f a l l l e a d e r s h i p c o n f e r e n c e

C O N T A C T S : T o r e g i s t e r f o r t h e p r o g r a m , c o n t a c t F o r q u e s t i o n s a b o u t t h e p r o g r a m , c o n t a c t M e l a n i e M e z i c k a t m e l a n i e @ l e a d i n c l u s i o n . o r g .

* denotes hybrid in-person and online delivery of the course

Winter 2023 Issue 17

Lee Ann Jung,PhD, is founder of Lead Inclusion, Clinical Professor at San Diego State University, and a consultant to schools worldwide.

REGISTER NOW! CLICK HERE

Preparing a School Community for DEIJB Work Through Developing Social and Emotional Competencies

By Amy Marsh Garden International School

Diversity, equity, inclusion, justice and belonging (DEIJB) is a prominent topic of discussion in schools worldwide, and momentum has been gathering as awareness of the need for this work grows. Following the Black Lives Matter movement, numerous books and publications have highlighted the structural racism that continues to exist across the globe. International schools are under the spotlight as data emerges showing the inequities in hiring practices and recruitment. Colonial roots need to be reckoned with as schools consider their values and place in the world.

DEIJB work is difficult: it can be confrontational as organisations and individuals are forced to consider their biases and behaviours. But it is necessary. There are wonderful organisations supporting schools with DEIJB work and plenty of advice within networks. Many schools and organisations are approaching this work through the lens of Belonging, to allow all members of a community to be included in the work, as we can all contribute to the idea of creating a sense of belonging. The book Belonging: The Key to Transforming and Maintaining Diversity, Inclusion and Equality at Work by Sue Unerman, Kathryn Jacobs and Mark Edwards, states the following as one of the prerequisites for everyone feeling they belong in their workplace:

“Organizations should train their people to develop their emotional intelligence and empathy, their self-awareness and their awareness of others. Individuals must also take responsibility to behave in an emotionally intelligent way”

Here I talk about some of the SEL (Social and Emotional Learning) work that schools can do to prepare their staff to hear the voices of marginalised groups in their communities, and help forge a sense of belonging for all.

Social and Emotional Learning

SEL is defined by CASEL (the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning) as the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions.

COVER STORY DEIJ

18 EARCOS Triannual Journal

There are five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision making. These are the competencies that we as educators try to instil in students. The biggest gap in SEL instruction is modelling, as adults continually model their own behaviours to children, whether they want to or not!

Adult SEL

There has been research over the last 25 years into the impact of teacher behaviours on student outcomes, with the oft-cited The Prosocial Classroom (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009) proposing a model of implementation in the classroom to support the development of these skills. Jennings and Greenberg also describe the characteristics of socially and emotionally competent teachers, and these are very useful to consider when looking at DEIJB work:

• Self Awareness: the ability to recognize your own thoughts, patterns, behaviours, motivations, strengths and weaknesses.

• Social Awareness: knowing how your emotions affect interactions with others and recognize emotions in others.

• Culturally Sensitive: the ability to see and understand different perspectives as a result of our cultural backgrounds and biases.

• Prosocial behaviours: understanding how your decisions will affect others and taking into account multiple factors when determining actions.

• Managing Emotions: the ability to regulate your own emotions in healthy ways to facilitate positive outcomes.

For organisations looking to develop adult SEL competencies, these five areas provide a good framework. Here I will outline some basic skills to consider in these areas, but this is just a starting point. Each of these characteristics could, and should, be explored in depth in order to make this work meaningful and purposeful.

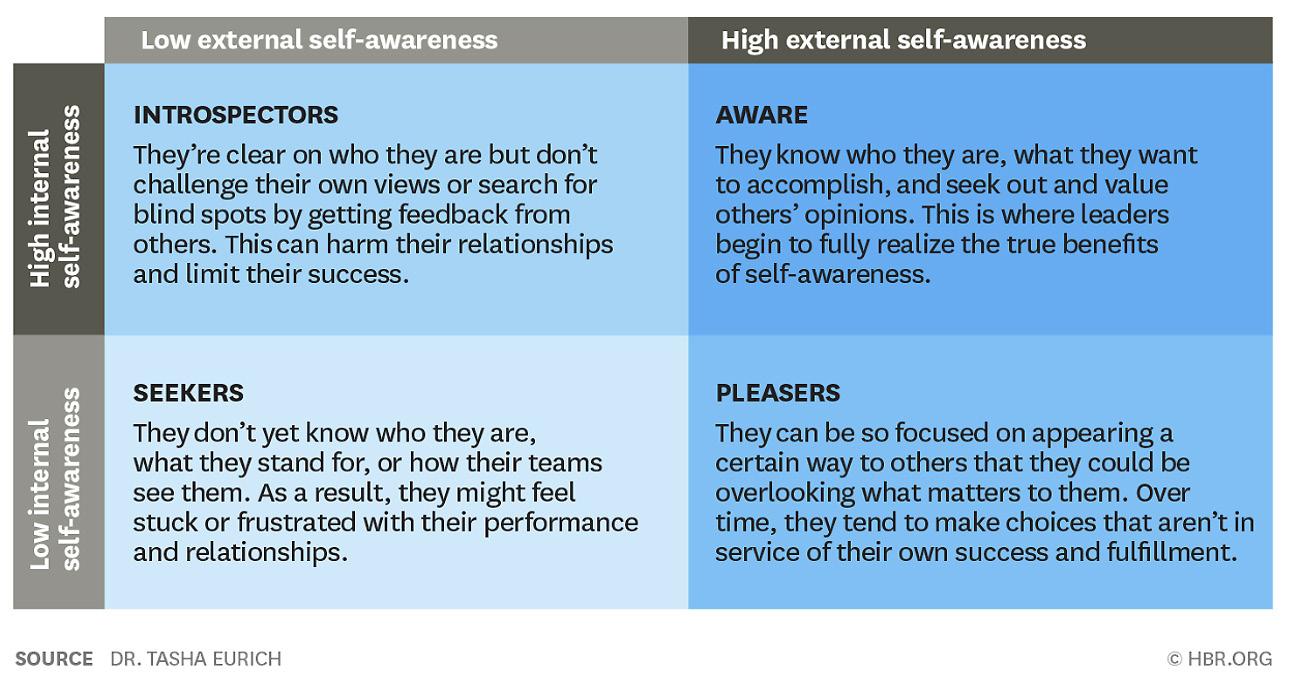

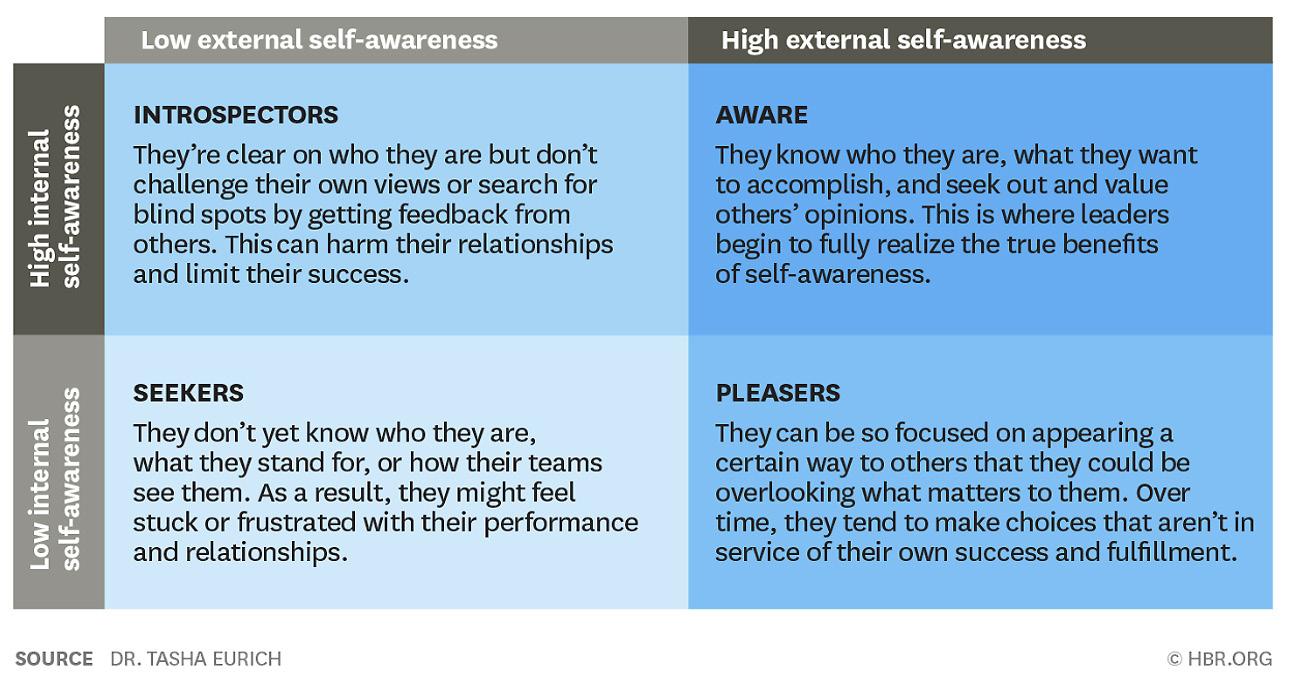

Self Awareness

Self awareness is the starting point for SEL work: it is highly unlikely you can consider how your emotions are affecting interactions with others if you don’t recognise your own emotions in reaction to situations. Dr Tasha Eurich has written extensively on self-awareness, including the distinction between internal and external. Her book, Insight, gives a good foundation in this competency and describes constructive ways to self-reflect rather than ruminating. Spending time reflecting on your own self-awareness and gaining feedback from others can help us recognise our biases and motivations, which will be important for DEIJB work.

Social Awareness

Being socially aware means being able to listen and take the perspective of others. This includes being able to recognise emotions. Listening skills are key to being able to interpret verbal and non-verbal cues to recognise what is not being said. The book Difficult Conversations also highlights the importance of understanding your own identity (part of self-awareness) in being able to truly listen to others, and outlines three conversations which are happening in every difficult conversation. These consist of:

1. The ‘what happened’ conversation which takes up mostif not all - of the time, discussing who did/said/meant what.

2. The feelings conversation: what emotion is each person experiencing?

3. The identity conversation: what internal debate is caused by the conversation and how does it relate to the selfconcept each person has?

Each of these can be explored in detail to help us to develop more social awareness in reading other people, but also in understanding how our own emotions can impact others.

Culturally Sensitive

As schools are faced with tackling inequity surrounding race and nationality, awareness of cultural differences and working interculturally has increased. Systemic discrimination is at the heart of DEIJB work, and many schools have started to take measures to look at their curricular offerings, and representation of their student body in the materials they use to teach. During this work, if the aim is the ability to see and understand different perspectives as a result of our cultural backgrounds and biases, then we need to be aware of ourselves to begin with. We also need to be aware of alternative perspectives and different identities.

Winter 2023 Issue 19

Examples of the types of learning teachers can do include looking at different cultures (such as using work by authors such as Erin Meyer, The Culture Map) and finding ways to authentically listen to the marginalised voices in their communities (for example, using an approach such as Street Data: A Next-Generational Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation by Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan).

Prosocial Behaviours

In order to give all students a voice in an equitable classroom, it is important for teachers to model respectful behaviour and communication across cultural differences. This does not require the teacher to be an expert, but to exhibit humility in trying to understand cultural norms. To understand how your decisions will affect others it can be as simple as asking them, and preferably inviting a diverse group of people into any planning so that different perspectives are recognised and accounted for. It is very hard to see how your behaviour would affect somebody else if you have no background information about their norms. Diversity is recognised as a strength in organisations (eg How Diversity Makes us Smarter) and a useful analogy from Susan Scott’s book, Fierce Conversations, is the idea of each person standing on a different stripe of a beach ball and only seeing their colour. Without hearing each viewpoint, you can’t zoom out and see all of the different colours. In the classroom, teachers who develop strong relationships with students by listening to their lived experiences provide a foundation for effective learning and respectful interactions.

Managing Emotions

DEIJB work requires listening to difficult truths and acknowledging individual responsibility in perpetuating injustice and inequity. It can be hard to manage our own emotions when acknowledging systemic injustice requires you to acknowledge the ways in which you have benefitted unfairly from the system. This leads people to defend their position and take a stance which is counterproductive to moving forwards with transparency. In Minal Bopaiah’s book, Equity, she talks about the potential pitfalls of provocative language. Unifying a community through highlighting similarities and interdependence can allow for a lowering of defensive barriers and an openness to understanding inequity. She highlights that using blanket statements about privilege as a result of race can be counterproductive:

“because they assume a knowledge of the system or privilege that most people don’t have. If we want to make such statements we must first explain the how behind them... You need to explain the causal links between ways of thinking and the results you see in our organisations and the world around us.”

This links back to the other competencies: to understand other people’s emotional reactions we need to develop a cultural understanding of their lived experience through our listening skills and social awareness. To manage our own emotions on hearing those experiences we need to understand our own identity and the triggers that cause an emotional reaction in ourselves so that we can become cognizant of those and develop ways to manage them.

So Where to Start?

Self-awareness is key, as all other work relies on an understanding of ourselves and our role in interactions and systems. However, DEIJB work is ultimately about understanding others. Organisations shouldn’t try to move too quickly because of the potential for staff to react defensively (and ultimately set back progress) if understanding has not been built up sufficiently for positive engagement. This is where SEL comes in and the foundational work that has to be done. Of course, in any organisation there will be individuals who are far ahead in this work and can move forward, but you want to be able to bring everybody along on the journey to avoid issues down the line.

Encouraging all staff to engage with self-awareness and managing their own behaviours can be a good place to start. One way could be to choose a small practice for people to focus on, such as recognising and labelling emotions (other examples in the article: SEL for Adults), and building from there. Those who are further ahead in this work could be working on clear communication strategies to help others understand those causal links between implicit biases and institutional practices. School leadership must be part of driving this work, and joining a collective who are on the same journey can be helpful in sharing reflections and practical support in enacting institutional change to address inequities in the system.

SEL work is just the start of the process; once you have listened to individuals and recognised the bias in your organisation you do need to take steps to address it. This is not a quick undertaking. There will be points at which this feels difficult, frustrating, and overwhelming; but by keeping coming back to why you are doing this, planning for incremental change over a period of time, and by having a supportive network, significant change is possible.

Biography

Jennings, Patricia & Greenberg, Mark. The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to child and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research. 491 (2009).

Eurich, Tasha, (2017). Insight (New York: Crown Business, 2017).

20 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Unerman, Sue, Jacobs, Kathryn & Edwards, Mark. Belonging: The Key to Transforming and Maintaining Diversity, Inclusion and Equality at Work (USA: Bloomsbury, 2022).

Stone, Douglas, Patton, Bruce & Heen, Sheila. Difficult Conversations, How to Discuss What Matters Most (UK: Penguin, 2021).

Meyer, Erin. The Culture Map, (UK: Hachette, 2014).

Safir, Shane & Dugan, Jamila. Street Data: A Next- Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. (USA: Corwin Press, 2021).

Phillips, Katherine. How Diversity Makes us Smarter (Scientific American, 2014).

Scott, Susan. Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success in Work and in Life, One Conversation at a Time. (UK: Hachette, 2011).

Bopaiah, Minal. Equity (USA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021).

About the Author Amy Marsh is the Director of Professional Learning at Garden International School.

SCAN to learn more Courses Online That Fit Any Schedule & Time Zone The University of Nebraska does not discriminate based upon any protected status. Please see go.unl.edu/nondiscrimination. 2208.014 AP® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, the University of Nebraska High School. U.S. diploma Accredited, college-preparatory program 100+ core, elective, AP®, dual enrollment & NCAA-approved courses Open enrollment Self-paced, independent study Responsive staff highschool.nebraska.edu/earcos (402) 472-3388 Winter 2023 Issue 21

Embracing Diversity through Differentiation

By Amin Bin Abu Bakar MYP Science & DP Physics Teacher International School of Nanshan Shenzhen

By Amin Bin Abu Bakar MYP Science & DP Physics Teacher International School of Nanshan Shenzhen

Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction (DI) is one of the strategies I use to create an inclusive environment for diverse learners in my classes. As a trainee teacher in Singapore, I did not recall encountering DI during my initial training. However, we were introduced to the concept of multiple intelligences that Howard Gardner popularized. As Gardner (2000) noted, intelligence tests are just the “tip of the cognitive iceberg” (p. 11). This infers that many aspects of intelligence remain to be addressed. DI is one way I can acknowledge the various spheres of intelligence and cater to the diversity of my learners. I was first introduced to DI during a professional development course I attended as a beginning teacher in Singapore. Initially, I was intimidated by it as I thought I had to create individual lessons for each student in my classes. In Singapore, a typical classroom could reach 33 students in the late 2000s. It was only through experience and interactions with more experienced teachers that I learned that DI could be further chunked into four aspects. Tomlinson (2014) identified them as (1) Content, (2) Process, (3) Product, and (4) Affect / Environment. This was a massive revelation to me as this meant I could focus on specific aspects of DI, and it was no longer as overwhelming as before.

Getting to know your students

For DI to be effective, I must first get to know my students. I always hold Theodore Roosevelt’s quote - People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care - close to me. By getting to know my student’s readiness, interests, and learner profile, as recommended by Tomlison (2014), I will be able to plan better. At the same time, I would set up my classroom to appeal to students as suggested by (McFarland-McDaniels, n.d.). I do this by decorating my Physics laboratory with students’ work. This serves a two-fold purpose; it helps improve the laboratory’s aesthetic and gives students a sense of pride to see their best work displayed. Since my laboratory has fixed benches, I am unable to rearrange the bench-

CURRICULUM

22 EARCOS Triannual Journal

es. Thankfully the laboratory has been designed to accommodate group work and other differentiated activities like activity centers and flexible grouping. Once I have gotten to know my students and arranged my classroom’s physical layout, I address the other three aspects identified by Tomlison (2014) earlier. Taylor (2014) refers to them as the “what” (content), “how” (process), and “evidence” (product).

Differentiating Content

When I first started, I was confused about how to differentiate content since the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Program (DP) Physics had prescribed learning outcomes that I needed to cover. Tomlison (2014) reminded teachers that differentiating the content doesn’t mean that the learning goals are changed but rather how these contents are shared with the students. In my case for Physics, there are times when I am in front of the class explaining certain concepts to them. I make use of other modes of content delivery as well. When I am physically in class, I can get my students to carry out experiments to verify or infer certain Physics principles. When I was teaching remotely, I used simulations to allow them to explore physics principles at their own pace.

Differentiating Process

For “process”, I use several strategies. One of them is through the use of flexible grouping. I find that students learn better when they collaborate. What I do is to have students of varying abilities to be in the same group. Sometimes, students understand their peers’ explanations better than their teachers. This could perhaps be attributed to generational gaps. I also usually combine flexible grouping with another strategy which is the use of Activity Centers. I find that Activity Centers help learners who tend to learn experientially. Estes (2004) shared that experiential learning allows learners to leverage their experiences to construct new understandings. Thus Activity Centers will enable individual students to build their own approach to understanding the concept to be shared.

Differentiating Product

Finally, for “product”, IB encourages students to develop their learner profile attributes. And one of these attributes is “communicators”. This attribute encourages students to use different forms of communication. For instance, in Criterion D of MYP Sci-

ence. I allow my students to come up with their own ways of reflecting on the impacts of Science. I have had students submit essays, animations, videos, and PowerPoint presentations, amongst others. While this might seem trivial, as a teacher, it is exciting to see what the students have in store for you at the end of the task. I have been blown away by moving videos edited by my students. It was a timely reminder that students might not be able to express themselves well in a medium of our choosing. Instead, allowing them to choose their product can remove the barriers to fully expressing themselves.

Conclusion

In conclusion, teachers should familiarize themselves with differentiated instructions as each student in the class is unique. Once DI has been chunked, it is not as intimidating as it seems. It makes learning more personal as students get the opportunity to showcase their individuality.

References

Estes, C. A. (2004). Promoting student-centered learning in experiential education. Journal of Experiential Education, 27(2), 141160.

Gardner, H. E. (2000). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. ProQuest Ebook Central

McCarthy, J. (2015). 3 Ways to Plan for Diverse Learners: What Teachers Do. McFarland-McDaniels, M. (n.d.). How to organize a classroom for diverse learners. Classroom.

Taylor, B.K. (2015). Content, process, and product: Modeling differentiated instruction. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 51(1), 13-17.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014).The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. ProQuest Ebook Central

About the Author

Amin is originally from Singapore. He graduated from Nanyang Technological University with a Bachelor of Science degree, majoring in Physics and minoring in Chemistry.

Chika’s Test for divisibility by 7, patterning and coding

Presented by: Ron Lancaster Saturday, February 11, 2023 9:00 AM HKT visit website

Winter 2023 Issue 23

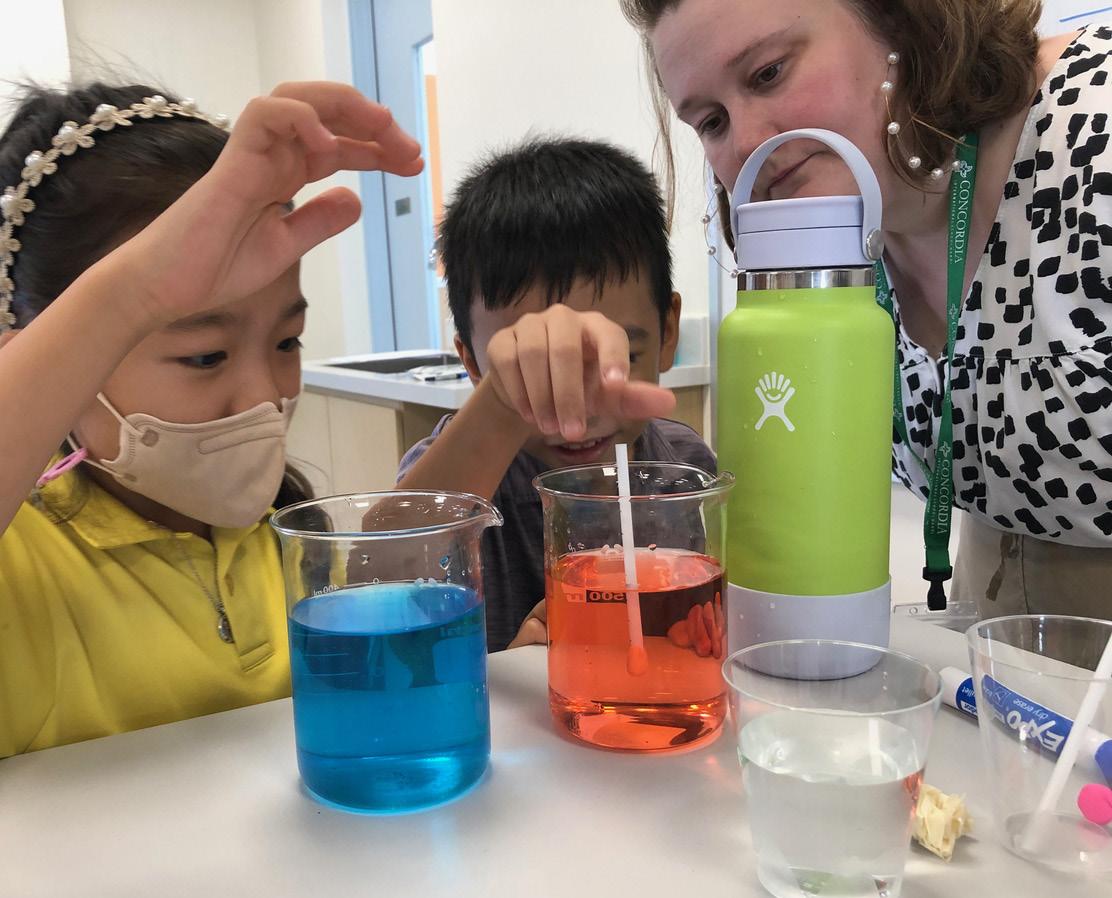

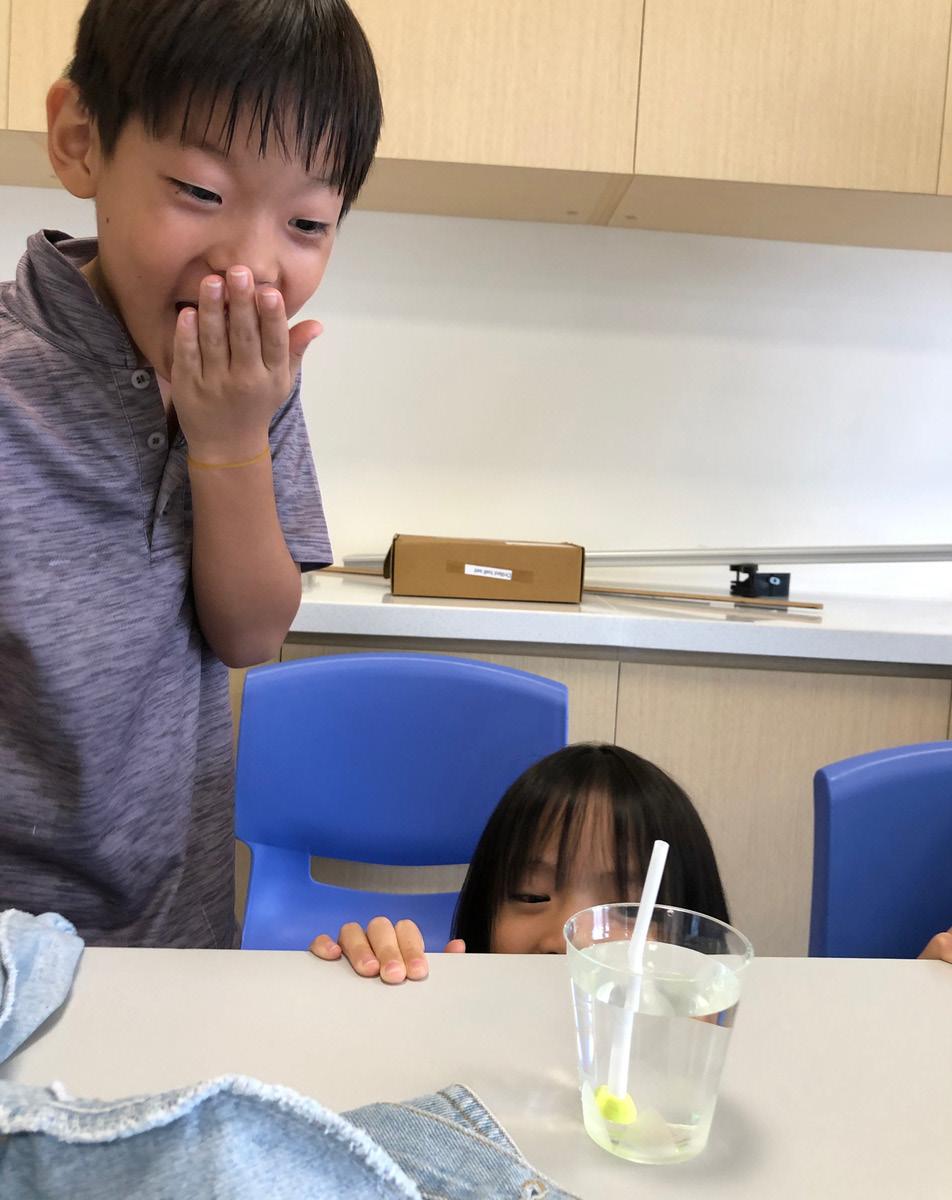

CURRICULUM Instructional Techniques within STEM Education

By Samuel Lee Mao Hua MYP/DP Chemistry Teacher International School of Nanshan Shenzhen

By Samuel Lee Mao Hua MYP/DP Chemistry Teacher International School of Nanshan Shenzhen

Introduction

The STEM’s aims (Morrison, 2006) are focused on cultivating passion, interest, ability to apply STEM-related knowledge and cultivating creativity, and problem-solving skills within the STEM area, i.e. Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics and in recent years arts were also included to become STEAM. The IB Learner’s Profile encourages values that aim to cultivate for their students to learn in general and in facing various challenges in life and is not focused on STEM discipline.

However, certain values that STEMs incorporate are similar to what the IB Learner’s profile (IBO, n.d.) aims to cultivate which essentially shows the trans-disciplinary nature of VALUES. The approaches to learning (ATL, n.d.) promoted by the IBO in the context of teaching and learning also helps to realize the IB Learner’s Profile through the following skills,

• Thinking skills

• Self-Management skills

• Social Skills

• Research Skills

• Communication skills

The virtues within the IB learner profile are intrinsic values that are universal and will apply across any situation such as students’ academia, living experiences and career. As an IB Chemistry teacher and where Chemistry is considered an experiential science, what amazed me with the values of STEM is that alike the IB pedagogy used in the approaches to learning, it emphasizes the importance of application, innovation, and synthesis of knowledge rather than just recalling of knowledge.

We need to see that we are in an age where knowledge is no longer for the privileged but open to all, hence as teachers, we are no longer the sole authority of the content that we are teaching (in my case Chemistry). There is a paradigm shift in our role as “depositors of knowledge” to become “facilitators of learning” (Alam, 2013).

Instructional Models of STEM

There are many instructional models to help teachers who often find difficulties to deliver/relate their knowledge to students and most of the instructional strategies that I have attempted in my past 10 years being an international school teacher were recommended by Bouchrika (n.d.) in the following,

• Gagne’s Nine Events of instruction

• Bloom’s taxonomy

• ADDIE model

24 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Out of which my favourite would be the Gagne’s Nine Events of instruction. However, in recent years, Bybee et al. (2006) proposed the 5E model which is also in one way or another similar to other models of instruction but specifically designed in interest for the teaching of STEM. In my opinion, all the instructional models available to us ultimately attempt to help the teacher to create a positive learning environment so that students can understand, accept, accommodate and apply knowledge learnt in class (Bouchrika, n.d., p. 1).

Firstly, the 5E model helps students to develop ownership of their learning progress through participating and engaging in lesson activities (Empowering students: The 5e model explained, n.d.). The role of the teacher is transformed from the sole authority of knowledge to a facilitator who is just there to help when there are issues during learning, this shifts the responsibility from the teacher to the student in constructing his/her knowledge through experiential learning where the learners engage, explores, explain, elaborate and evaluates.

For example in the video, the learners are given opportunities at each stage in modifying to reach their assessment objectives - for the Car, and we can see that these learners were trying to engage, explore, explain to assimilate and accommodate knowledge into their existing schemata (Lee & Kwon, 2001).

The second advantage would be to develop teamwork, communication skills and problem-solving skills. In the video, we can see that students collaborate to investigate how their model failed to work and shared ideas to troubleshoot and solve issues that went wrong. In the process, they learn how to listen to one another, respect differing points of view and critically analyse to select the best possible approach to solve the problem. In the 21st century where knowledge is readily abundant, it is not about what we know but rather how we use knowledge to solve issues and to progress as a society

One disadvantage of this model according to Pham (2014) is that he cannot provide immediate help when he witnesses students committing “stupid mistakes” since allowing mistakes to happen is part and parcel of the learning experience. Furthermore, this can lead to the “construction of wrong knowledge” and if not acknowledged and realised at an early stage will lead to disastrous results if the student goes on to apply “wrong knowledge”.

This model is helpful for an inquiry-based approach, particularly for IBDP teachers in guiding the Group 4 internal assessment and the extended essay.

• Engagement: Teachers assess students’ knowledge and get them to interested through a context. Similar to Gagne’s nine events of instruction as described by Wong (2018)

• Exploration: Students explore the topic. Materials used for exploration can be prepared by either students or teachers. Teacher to facilitate discussion and exploration.