The EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL

Featured in this Issue

Research

An Empirical Evaluation of Adolescent Anxiety and Depression in International Schools: Findings and Implications

Board Roles

Board & Member Roles & Responsibilities

Action Research

Engaging Host Country National Teachers

Green & Sustainable

Regenerative Education: Teaching and Learning that Heals and Restores

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School), President

James Dalziel (NIST International School), Vice President

Jim Gerhard (Seoul International School), Secretary

Rami Madani (International School of Kuala Lumpur), Treasurer

Gregory Hedger (The International School Yangon), WASC Representative

Karrie Dietz (Australian International School Singapore)

Matthew Parr (Nagoya International School)

Marta Medved Krajnovic (Western Academy of Beijing)

Maya Nelson (Jakarta Intercultural School)

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou), Past President

Margaret Alvarez (WASC), Ex-Officio

Andrew Hoover (Office of Overseas Schools, REO, East Asia Pacific)

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Maica Cruz, Events Coordinator

Ver Castro, Membership & I.T. Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator, Webmaster

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Staff

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

Global Citizenship Award Curious Kids: Igniting Passion for Lifelong STEM Learning in China By Suah Lee Elevating Your Persuasion: A Debate Workshop By Hayoon Jeong (Julie) H.E.R (Health. Equity. Respect) By JiaJia Khwanchanok Paka-Akaralerdkul

Executive Director’s Message

A very warm welcome the winter issue of the EARCOS Tri-annual Journal. All of us at EARCOS send you our very best wishes for a happy and healthy start to 2025.

In this issue you will find a rich collection of articles that embrace so many of the topics that concern all of us in international education today. From the power of service learning to the growing and uncertain impact of AI, to inclusion and neurodiversity, to the never-to-beunder-estimated importance of good governance, there is so much to consider in this issue of ET. And, as is always the case, the articles in this issue underscore the rich talents and diversity that define the educators in the EARCOS region. I thank each of them for their contributions to this issue.

I would like to direct your attention to the lead article in this issue, An Empirical Evaluation of Adolescent Anxiety and Depression in International Schools by James Rosow, Karly Knopf and Sean Truman.

For the past five years, our region has enjoyed a special partnership with the Truman Group, clinical psychologists who have led extensive, confidential conversations with small groups of school leaders and cohorts of counselors across this region. Launched in the early days of the pandemic, the Truman Cohorts have been among the most important initiatives EARCOS has ever undertaken. We are especially grateful for the grants and logistical support we have received each year from the Office of Overseas Schools to make the program thrive.

In addition to supporting cohorts of counselors and school leaders, the Truman Group has also shared numerous dynamic presentations at our conferences. Furthermore, the insights and partnership they provided at the Heads’ Institute in Luang Prabang several years ago continues to impact many of our schools. And now, in this issue of the EARCOS Journal, you will find a white paper from the Truman Group on the study they conducted on student social and emotional well-being in a selection of EARCOS schools. It merits your careful attention.

The Truman Group research team used the word ‘alarming’ to describe their findings. This was due to the surprisingly large and unexpected number of international school students who reported serious levels of isolation, stress, anxiety and depression. We must all heed the warnings within the study. Clearly, based on their findings (and so many instances many of you have reported in the past several years), international educators need to re-think what we do and don’t do to ensure that all students are seen and given the support they need to live balanced, happy and emotionally healthy lives. This is of course, far easier said than done.

There is a diverse and unsavory cocktail of forces impacting the mental and emotional health of international students in grades 9-12 today. Much of what the Truman study found mirrors other recent reports on adolescent mental health. A 2023 US government report from the

Surgeon General noted that more than half of teen girls felt ‘persistently sad or hopeless.’ It is no minor observation that television watching has supplanted conversation in homes everywhere—often family members watch television in separate rooms. Isolation and loneliness, even within the family setting, has become far too common. And, there is good reason for the increasing number of schools that have established policies to reduce the use of cell phones during the school day. These omnipresent devices have contributed significantly to the isolation young people experience, as Derek Thompson explained in a recent Atlantic cover article.

The typical person is awake for about 900 minutes a day. …[T]eenagers spend, on average, about 270 minutes on weekdays and 380 minutes on weekends gazing into their screens. By this account, screens occupy more than 30 percent of their waking life. (Thompson, D. The Anti-Social Century. The Atlantic, February 2025: 30).

Screentime is not really a social occasion, no matter the term social media. There are other issues as well, not the least of which is an on-line ‘bullying culture’ which is a separate and disturbing topic in and of itself.

There are no magical programs that you can just take off the shelf to resolve the social and emotional issues confronting students today. There are, however, directions to be considered, several of which are suggested in the Truman paper. These include the need to provide supplemental clinical training for school counselors and other key staff members. The study also makes clear that students must be provided with more opportunities to exercise and play and—yes--to sleep. Again, easier said than done as these suggestions fly in the face of the status quo of what school days are ‘expected’ to offer.

It is our hope in sharing this research with you that it will spark thoughtful conversations across our schools about the changing realities and rising challenges in emotional well-being that all young people entrusted to our care face today. What is your school doing—or considering doing—to help students counter the complexities of growing up in today’s hyper-paced, overscheduled, device filled world?

Please consider this your invitation to share your thoughts and initiatives on this vital topic in the next issue of ET. Manuscripts should be submitted by April 1, 2025.

With all best wishes,

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

STRANDS

Physical Education/Wellness/Health

Visual Arts

Film

Design Technology

Robotics

Performing Arts: - Choral Music - Dance - Drama - Strings - Band Technology

General Education Topics

PRECONFERENCES

TieCare Congratulates the Purple Community Fund for winning the 2023 Krajczar Humanitarian Award.

Mark Tomaszewski, President of TieCare International, gave the below comments at the EARCOS Fall Leadership Conference in Bangkok in October in recognition of the Purple Community Fund receiving the 2024 Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award 2023.

The EARCOS Conference is like entering the home of Dr. Krajczar and his wife, Sherry, and his children, Josh and Morgan.

Open doors, open minds, open bar.

Familiar faces, friends, free food. Some people say that EARCOS isn’t the same since Dr. K. left us to fend for ourselves in 2019. We don’ t see him walking the exhibit floor, ringing his bell to get people inside the conference and breakout rooms. Shaking hands with everyone and somehow being able to recall everyone’s name.

But one thing hasn’t changed at EARCOS: the belief espoused by Dr. K to care for others.

The underserved, the underprivileged, the underdogs.

Dick was the epitome of the underdog. The scrawny American high school football player who left Pennsylvania for Wyoming for the only college who wanted him to play on their team.

Fast forward to many years of teaching and leadership in international education with assignments in Afghanistan, Syria, Jordan, Kuala Lumpur, the Philippines, and his many years with AAIE and EARCOS. The back of Dick’s proverbial baseball card was quite impressive.

tiecare.com | info@tiecare.com

As a leading provider of employee benefits for international educators, TieCare was fortunate to have a long-time association with Dick. We weren’t just an EARCOS exhibitor; we were his insurance company for many years, including at the end. We were his customer, finding the best sponsorship opportunities for the mutual benefit of both EARCOS and TieCare. In return, Dick was always our friend and supporter. When the chance to sponsor an award in Dick’s honor became available, the boss of TieCare couldn’t say “yes” fast enough. That boss, of course, was me.

While Dr. K is no longer with us, the TieCare team is thrilled to help keep his memory alive.

So, to honor the legacy of Dr. K, we are proud and honored to present the 2024 Richard Krajczar Humanitarian Award to Ruth McLellan and Amy Lucas on behalf of Purple Community Fund in collaboration with St. Joesph’s Institution International.

Mark Tomaszewski President, TieCare International

Ruth McLellan and Amy Lucas of the Purple Community Fund accept the Krajczar Humanitarian Award from Mark Tomaszewski and Dr. Edward Greene, Executive Director of EARCOS.

Josh Krajczar, Dick’s son, and Mrs. Sherry Krajczar joined the presentation of the Humanitarian Award at the EARCOS Fall Leadership Conference in Bangkok.

Click here to read the full article about this year’s Humanitarian Award winner. Learn more about the Purple Community Fund at www.p-c-f.org

An Empirical Evaluation of Adolescent Anxiety and Depression in International Schools: Findings and Implications

By James Rosow, PhD, LP, Karly Knopf, BS, Susan Bernstein, MBA, & Sean Truman, PhD, LP

Contents

• Background

• Research Objectives

• Research Design

• Key Findings

o Anxiety & Depression

o Suicidal Ideation

o Gender Differences

o School Stress & Support

o Sleep & Exercise

• Research Implications

• Future Research

• Limitations

• References

• Appendix

Background

Over the past fifteen years, a wide range of studies have found that the number of young people suffering from impaired anxiety and depression is increasing at an alarming rate. This pattern of findings has emerged from both nationally representative data in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024) as well as from international studies. Racine et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 136 studies from around the world and found that 20 to 25% of young people report impaired symptoms of anxiety and/or depression.

Recent clinical and anecdotal evidence also supports these findings. The demand for mental health care is high, and insurance claims for mental health care are significant drivers of healthcare costs. A report from a large provider of health insurance for international schools conveyed that the cost of mental health claims has tripled since 2019 (GBG, personal communication, October 2023). This demand has stretched community-based support worldwide. At the Truman Group, we have seen a steady rise in young people with anxiety disorders and depression referred to our practice for treatment.

In addition to providing clinical care, our group also consults with school counselors around the world. Over the last six years we have run a program that provides consultation groups to international school counselors. Last year nearly 200 counselors participated in these consult groups, and they, too, reported increasing numbers of students impaired by anxiety and mood dysregulation. Parents and educators have also been affected by this change and they are uncertain about how to respond to the mental health needs of young people in their communities.

In the fall of 2023, in partnership with seven international schools, we undertook a research initiative with two broad aims: to better understand the exceptionally high levels of anxiety and depression we have been seeing among international school students, and to help determine what we, as clinicians, educators, and parents, can do to help young people feel better and function more effectively. To date, there has been little empirical research that has focused on these issues in the international school community, and this study is an initial effort to address this gap in knowledge.

Research Design

Between September and December 2023, the Truman Group fielded a web-based survey to students in grades 9-12 across seven international schools in Southeast Asia (see appendix for list of partner schools). Participants were administered the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to measure symptoms of depression and anxiety. These two instruments are well-established, reliable and valid measures that have been used for decades in clinical applications and research. In addition to completing the two inventories, participants were asked to provide demographic information and information about:

• Number of schools attended

• Years lived in their current location

• Lifetime number of moves

• Hours slept the previous night

• How many times they looked at their phone after going to bed

• Amount of exercise they engaged in over the last week

• Number of friends in person and online

• Number of hours spent on social media per day

• School stress

Research Findings

Anxiety & Depression

Respondent ratings on both the BDI and the STAI were elevated. On the BDI, 8% of students scored in the Severe range, and 21% scored in the Moderate range, both of which signify depressive symptoms that are of clinical concern (see Figure 1). Anxiety scores were even more notable, with 61% of students reporting High Anxiety, a rate that is entirely unexpected in a normal school population (see Figure 2). In short, large numbers of students in the international school community appear to be managing clinically impairing symptoms on a daily basis.

While the depression scores among our sample were high, they reflect similar rates of depression found in other studies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). The level of anxiety reported by our sample, however, was alarming, with more than half of students scoring in the highest category of risk for anxiety on the STAI. The magnitude of this finding is striking and suggests that we have not fully appreciated the level of anxiety students chronically experience.

Suicidal Ideation

Two items on the BDI solicit information about thoughts of death and suicidal ideation, and given the importance of these items, we looked at them individually (see Table 1). Students reported thoughts of death and suicidal ideation at very high levels, with nearly a third of the student sample indicating thoughts about death and/or suicide. That rate is unexpected and very high. Estimates in the general population for the lifetime prevalence of suicidal thoughts is 15% (Strashny et al., 2023). More concerning is that 5% of students reported that they either wanted to kill themselves, or that they would kill themselves if they had the chance. These findings point toward the urgent need to define and develop a different approach into how we talk with and work with young people, in general, and regarding mental health specifically.

Gender Differences

Several gender differences emerged from the analyses (see Table 2). Girls had higher BDI scores than boys, and gender-nonconforming students reported the highest levels of anxiety, depression and school stress of all groups. Gender nonconforming students also described feeling the lowest level of support at school. These findings are consistent with a range of other studies that show girls to be at higher risk for depression, and gender nonconforming students to be at a very high risk for a range of emotional problems.

Table 2

Mean Anxiety, Depression, Support and School Stress by Gender

School Stress & Support

School stress was positively correlated with both anxiety and depression measures, where students who perceived higher levels of school stress scored higher on the BDI and STAI. Notably, student ratings of school support were negatively correlated with anxiety and depression, which indicates that, as the perception of school support goes up, anxiety and depression ratings go down. These findings highlight the centrality of students’ experience at school as it affects their emotional state.

Table 3

Student Correlational Analyses with STAI and BDI Scores

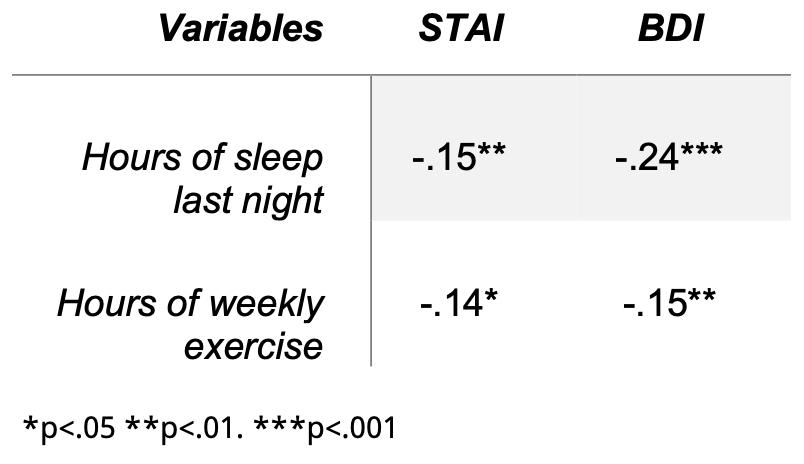

Sleep & Exercise

Another important finding concerns sleep and exercise. Getting more sleep and exercise were both related to lower ratings of anxiety and depression. This fact indicates the importance of these activities as mitigating factors for mental health and overall well-being. Stated simply, the more that young people sleep and move their bodies, the better they feel emotionally.

Table 4

Student Correlational Analyses with STAI and BDI Scores

Social Support

Historically we have believed that people who have more friends benefit from the social support that moderates difficult life circumstances. However, in our study there was no significant relation between the number of in-person friends students report having and anxiety and depression scores. Moreover, students who reported having more online friends reported having higher levels of anxiety. This finding suggests two possible interpretations – that managing online friendships can be stress-inducing for young people, and/or that young people today are less equipped to benefit from in-person interpersonal relationships.

Table 5

Student Correlational Analyses with STAI and BDI Scores

Number of Schools

Finally, students who attended more schools had higher ratings of depression on the BDI. This finding isn’t surprising, as multiple disruptions in a school setting would be expected to be disruptive to mood.

Table 5

Student Correlational Analyses with STAI and BDI Scores

It is worth noting that we expected to see several variables affect each other that did not emerge in our analyses. The number of times students reported looking at their phones after going to bed, and the number of hours they reported using social media per day were not related to either BDI or STAI ratings. This finding (or lack thereof) suggests that the relationship between technology and the use of social media is more complex than many believe, and that the drivers of emotional vulnerability are likely multifactorial.

Research Implications

The levels of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation reported by the students who participated in this study are concerning and point to several implications for schools. First, an effort should be made to identify students struggling with disrupted mood and evaluate them for risk. We recommend that school counseling staff stratify students into one of three risk categories (Low, Medium and High), follow up with higher-risk individuals consistently and, when appropriate, refer them for outside care. A subset of the highest-risk group may not be able to safely remain in school, potentially requiring more intensive clinical intervention and an incremental return to school once they are well enough to return to campus.

Second, given the limited mental health resources available in many international communities, we recommend supplemental clinical training for school counselors and other key staff members to help fill in the care gap. School counselors need to be able distinguish between students who are profoundly disrupted and those who can manage themselves within a school environment. In addition, maintaining clear lines of responsibility, consistent record-keeping and effective communication are critical to supporting students effectively.

We suggest that schools develop a dedicated response team

composed of counseling staff and a senior administrator to manage the needs of highly distressed and emotionally disrupted students.

Third, a number of controllable factors help mitigate symptomatology. Students who get more sleep, who exercise more and who experience higher levels of support at school report feeling less depressed and anxious. This provides guidance for ways that schools can globally encourage students to care for themselves more effectively.

Another simple, but compelling finding that schools can use to good effect is that when students sleep more, they experience greater levels of support at school. It appears that being sleep “nourished” leads to a more clear-headed interpretation of what is helpful and supportive to students.

Fourth, school support is central to the ways in which students experience their time at school. School support (and students’ ability to use it effectively) is a means of reducing impairing anxiety and depression in students. More work is required to define what types of support are active in this process, so that schools can better design interventions that will effectively bolster student function.

Finally, while a subset of students will likely always struggle with high anxiety, the fact that 61% of our sample scored at the highest level of risk on the STAI is remarkable. We are of the mind that students are increasingly sensitive to their emotional states, so much so that normative experiences that should not cause an anxiety response (but could make a young person worried, sad, angry, disappointed

or frustrated) are misattributed as anxiety. When individuals think of their experience as pathological, the misattribution becomes self-limiting, reduces resilience, and perpetuates itself over time. Distinguishing between students who are oversensitive to changes in emotional state and students who have diagnosable disorders that require care is increasingly important, and schools will need help developing systems that distinguish between the two.

Future Research

Subsequent studies with larger samples across more schools will improve the reliability of our findings and help develop new lines of investigation. We plan to extend this work and hope to partner with more international school communities to broaden our data collection. Additional research is required to investigate what components of school support are most active and powerful, so that schools can strategically and proactively develop programming that will support students effectively.

More investigation is also needed to understand how and why inperson friendships did not appear to affect ratings of anxiety or depression. Equally important is the finding that online friends were related to increased anxiety, which suggests that the kinds of relationships young people characterize as friendships appear to convey emotional risks instead of benefits. Understanding how young people derive benefit from friendship is central to understanding these issues. It is unclear if these findings are the result of experiences that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether they are technology or social media-driven, or if there are other factors at play. All these issues should be investigated further.

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of this study and its findings. Primarily, because participation was voluntary, sample bias may skew our findings. Second, while we were pleased that seven schools participated in the student, a larger sample size would make the data more reliable. We consider this study to be a starting point and would like to continue to work to investigate how living internationally affects young people.

References

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, July 12). Household Pulse Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved on July 18, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mentalhealth.htm

Racine, N., McArthur, B., Cooke, J., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19. A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr, 175(11), 1142-1150. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Strashny, A., Cairns, C., Ashman, J. J., (2023) Emergency department visits with suicidal ideation: United States, 2016–2020. NCHS Data Brief, (463). https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:125704

Appendix

Partner Schools

• American International School Guangzhou

• Canggu Community School

• International School of Myanmar

• International School of Phnom Penh

• Seoul International School

• The International School Yangon

• Vientiane International School

Advancing Excellence in Global Education

Comprehensive Support

We work in partnership with schools through personalized support and by providing resources, training and access to networks that lead to successful accreditation outcomes

Worldwide Recognition

Graduates from WASCaccredited schools are welcomed by universities worldwide, including Harvard, Stanford, and Yale, as well as Cambridge, Oxford, NUS, and the University of Melbourne.

Proven Excellence

WASC accreditation signals a commitment to delivering high-quality education, empowering schools to stand out and provide an exceptional learning experience

The Accrediting Commission for Schools, Western Association of Schools and Colleges (ACS WASC), is a globally recognized accrediting body dedicated to advancing and validating the quality of education in schools worldwide

Join the thousands of schools worldwide that trust ACS WASC to elevate their standards, unlock global opportunities, and prepare students for a boundless future Take the next step in putting your school on the world map of education

Three-Part Series (Part 2)

Board & Member Roles & Responsibilities

By Kristi Williams

Building on the foundational understanding of governance from our first article, it is now essential to break down the board’s specific roles and responsibilities. The board is not just a governing body, but a strategic entity that ensures a school’s future stability and growth. In this article, we will dive into the key responsibilities of a school board—setting direction, managing fiduciary risks, and overseeing management— to highlight how these tasks align with the board’s ultimate goal: ensuring that the school can continue to fulfill its mission in an ever-changing global landscape.

Board’s Role

The fundamental role of a board is to safeguard the mission and vision of the school and to secure its future.

The board as a whole is the decision-making body that sets strategy and oversees management. The board is tasked with actively shaping the strategic direction, ensuring financial sustainability, and supporting the effective management of the school.

• 90% of the board’s focus is on the future and ensuring the sustainability and success of the school in 3+ years.

• 10% of the board’s focus is supporting, collaborating and nurturing the Head of School to be effective and successful for the students and school today and for the next 2-3 years.

Board Responsibilities

The responsibilities of the board can be categorized into three primary areas:

1. Setting the direction

2. Managing fiduciary risk

3. Overseeing management

1. Setting the Direction

Setting the strategic direction of the school is one of the most critical responsibilities of the board and answers two key questions: 1) Are we doing what we promised? 2) Where should we go?

In setting the direction of the school the board has two responsibilities:

A. Develop, support and represent the mission and vision of the school: What are we promising our community and are we delivering on our promise?

B. Develop long-term strategic targets: Where should we go?

What are we promising?

The mission and vision of a school are fundamental guiding principles that define the school’s purpose, goals, and aspirations. A vision statement is the bigger objective that the school aspires to achieve. It is meant to be aspirational and inspirational. A mission statement is a promise to your students, families and community. It’s a statement of what the school provides students.

The board is responsible for reviewing and monitoring the mission to ensure that the school is delivering on its promise..

For example, using the following generic school mission, the board needs to look at what the school is promising and how to measure progress.

“To provide a transformative and inclusive educational experience that fosters academic excellence, cultural understanding, and global citizenship. We strive to equip students with the skills and values needed to thrive in an interconnected world.”

This mission is promises to:

• foster academic excellence, cultural understanding and global citizenship

• equip students with skills and values needed to thrive.

Boards should be asking:

i. How do we know the school fosters academic excellence, cultural understanding and global citizenship? What is the school offering/ doing to make this happen? How do we measure the growth of cultural understanding?

ii. What skills are we equipping our students with? What skills are needed to thrive?

Highly effective boards act as the custodian of the school’s mission and vision. At independent international schools, Boards don’t represent parents or the association but represent the mission and the vision of the school, protecting and preserving the core values and principles that the school stands for. Boards do this by ensuring that all decisions and actions are consistent with these foundational elements and are moving the school forward toward long-term strategic targets.

Where should we go?

Highly effective boards also devote their time to continuously engaging in long-term, strategic thinking and discussions that explore new opportunities and anticipate future challenges.

In setting direction, the board’s role is to:

• Develop Strategic Targets: In collaboration with leadership, the board develops long-term strategic targets. Targets are typically longer-term, spanning three to five+ years. The board works to identify key areas for growth and improvement, and what the school can be in 5-10 years.

• Ensure Mission and Vision Alignment: The board ensures that the strategic targets align with the school’s mission and vision.

• Provide Resource Allocation: The board manages financial oversight to ensure funding for the strategic targets. This involves multiyear financial and budget planning and potentially looking at additional resource generation.

• Monitor Progress: The board monitors the implementation of a strategic plan through regular reviews and assessments. This involves tracking progress against defined metrics, evaluating the effectiveness of initiatives, and ensuring that the school stays on track to achieve its strategic goals.

2. Managing Fiduciary Risk

Effective governance includes comprehensive fiduciary strategies that ensure the school will exist for 5, 10 and 20 years. The fiduciary role of the board is a key responsibility that involves acting in the best interest of the school, ensuring its financial, legal, ethical, and reputational health, and safeguarding its assets.

The fiduciary responsibilities of the board include

• Developing comprehensive governance policies, board accountability and ensuring comprehensive school policies and procedures are in place.

• Providing sound financial oversight for long-term stability including responsible budget building, diversifying revenue streams, managing financial reserves and capital funds and safeguarding assets.

• Managing Reputational & Ethical Risk, includes maintaining high operational and academic standards, ensuring there is a crisis management plan in place and ensuring clear and transparent communication channels between the school and all stakeholders.

• Managing Legal Risk, this includes ensuring the leadership and school have adequate legal representation for local, regional, and international guidance.

3. Overseeing Management

It is the board’s responsibility to ensure that the school has the right people, structures, policies, and processes in place to fulfill the mission and to reach strategic targets.

Management oversight involves a few key activities:

• Hiring and if necessary firing the Head of School/Director

The board is responsible for hiring a qualified Head of School/ Director who aligns with the school’s mission and vision and moves the school forward.

• Performance Assessment

The board conducts an annual assessment of the Head of School/ Director’s performance. This involves collaboratively setting clear performance expectations toward policy implementation, reaching strategic targets and living the mission.

• Supporting Head of School/Director

The board must provide ongoing support to the Head of School/ Director, including overseeing the well-being of the Head/Director and his/her family, professional development opportunities other resources he/she needs to succeed and continued public support.

• Giving Space

The board needs to provide space for the Head/Director to lead the school and manage operations, allowing the Head/Director to get the right people, structures and policies in place to move the school forward.

Board Member Role and Responsibilities

The board as a whole has the authority and responsibility to set strategies, make decisions and perform oversight. The board speaks with one voice, and no individual board member has any authority. While the board sets the strategic direction and makes overarching decisions for the school, board members play a vital role in supporting these efforts through their specific duties and contributions.

A board member’s role is to research, discuss, debate, bring their own perspectives and make recommendations that will serve the school’s longevity and sustainability. Board members serve through participating on committees and serving as board officer.

Board committees are where the work of the board should be happening. Board committees bring recommendations to the full board as a whole to make decisions, approve, or adopt.

Highly effective Board members:

• Commit to the Role of Board Board members need to fully understand and commit to the role of the board – which is to ensure the long-term stability of the school. The board’s focus is a minimum of 3 years in the future and the goal is to ensure/grow/build a school for students in 3+ years. The focus of the board is not about “fixing” the school for current students and individual board members need to understand this and fully commit to this understanding.

• Contribute to Committee Work

The work of the board is done in committees. Committees are typically focused on areas such as finance, governance, strategic planning, development, and Head of School/Director search.

• Become a Board Officer

Volunteering more time and focus as a Board Officer. Board Officers take the lead to facilitate board operations, decision-making, accountability and team building.

• Advocate and Represent

Board members function as ambassadors for the school within the community and beyond, promoting the school’s mission and vision, building relationships with stakeholders, and advocating for the school’s interests.

In conclusion, the role of an international school board is multifaceted, extending far beyond the operational oversight to include the strategic guidance that ensures the school’s long-term sustainability. By effectively setting strategic direction, managing fiduciary risks, and providing oversight of school management, boards lay the groundwork for sustained success. However, this success depends not just on the work of the board as a whole, but on the commitment of each individual member to fulfill their responsibilities with integrity and accountability.

In the next article, we will delve into strategies to grow and sustain the board and how to remain accountable.

About the Author

Kristi Williams is a recognized leader in partnering with international and independent schools and non-profit organizations to empower boards, leaders, and teams.

Kristi specializes in empowering boards to optimize governance, shape policy, and develop board members’ capacities to make an impact. Her experience in strategic planning ensures boards and schools are equipped for success and stability in today’s dynamic environment. Kristi is a Board Governance Trainer authorized by the US State Department Office of Overseas Schools and a CIS Affiliated Consultant

Email: Williams.kristi@gmail.com | LinkedIn

International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (ICMEC) Level 1

Presented by: Debbie Downes

Tuesday, January 17, 22, & 31 2025

The Coaching Mindset: Working Better Together

Presented by: Kim Cofino

Saturday, January 25, 2025

>> Reserve your slot now. click here

Explore comprehensive ISS services for the dynamic transformation of international education

• Learn with professional development

• Recruit school leaders and teachers

• Start and manage a school

• Supply a school

• Streamline accounting and finance

• Cultivate diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and belonging

Plus, visit ISS.edu/events to save your place at job fairs, register for PD courses, and stay current on key topics affecting educators like AI and ed tech.

Get started at ISS.edu #ISSedu

When the Mission Wanders: How to Bring Your School Back on Track (Again)

By Lianne Dominguez

Post-accreditation visits always leave me reflecting. This time, I’ve been turning over a big question: How do schools stay true to their mission, and what happens when they lose sight of it? Missiondriven leadership and school development are at the heart of what I do, and it got me thinking—what do you do when your mission feels more like a decorative plaque than a driving force?

Interestingly, this isn’t just my reflection. Many educators and leaders I’ve met have shared the same concern. Let’s be honest: running a school is chaotic. Between the meetings, lesson plans, extracurricular activities, emails (so. many. emails.), and never-ending to-do lists, it’s easy for the big picture—your school’s mission—to slip into the background. Maybe it’s gathering dust on a wall, or maybe it’s being tossed around in staff meetings like a motivational soundbite. But is it alive in the everyday decisions, actions, and culture of your school?

If you’re nodding along because your school’s mission feels more like a distant memory than a living, breathing force, don’t worry.You’re not alone, and all is not lost. No matter how far you’ve drifted, there are practical steps you can take to realign your school with its mission and regain that sense of purpose.

Here’s my take and lessons I've learned from all the "greats" out there on how to move forward when your school seems to have lost its way—and how to do it without drowning in fear or overwhelm.

1. Take a Hard, Honest Look

Before you can course-correct, you need to admit that you’re off course. Gather your leadership team and reflect:

• Is our mission clear to us?

• Are we living it in our decisions, programs, and culture?

• Does it show up in how we communicate, teach, and interact with our community?

This can be a tough pill to swallow, especially if the answer is “not really.” But acknowledging the gap between your mission and reality is the first—and most important—step. And hey, admitting it is way better than pretending everything’s fine while the ship sinks.

2. Bring Your Team on Board

Your school’s mission isn’t something you, as a leader, can fix alone. It’s a collective effort that requires buy-in from staff, students, and families. Start with your team:

• Host a candid meeting (or series of meetings) to talk about the mission. Be real about where you are versus where you want to be.

• Ask for input—how do staff see the mission? What’s working? What feels out of sync?

• Remind everyone why they’re here. Chances are, most educators chose this profession because they care deeply about making a difference. Connecting back to that “why” can be a powerful motivator.

Be prepared for some grumbles. Change is hard, and admitting you’re off track can feel uncomfortable. But vulnerability is key to moving forward.

3. Break the Mission Down into Actions

One of the reasons missions end up on the walls instead of in the work is that they feel huge and abstract. Take yours and translate it into clear, actionable goals. For example:

• Mission: “To nurture every student’s potential.”

• Actionable Goals: Regularly review how students are supported academically, emotionally, and socially. Create more opportunities for student voice.

By breaking it down into practical steps, you make it easier for your staff to weave the mission into their daily work.

4. Involve Your Students and Families

Your school’s mission doesn’t just belong to the leadership team—it belongs to the whole community. Open the conversation to students and families:

• Host forums or focus groups to hear their perspectives on the mission.

• Share your goals for realignment and invite feedback.

• Give students ownership of the mission by connecting it to their learning and leadership opportunities.

You’ll be surprised how insightful and inspiring their contributions can be. Plus, it builds trust and a sense of shared responsibility.

5. Celebrate Small Wins

Reconnecting with your mission isn’t a one-and-done project—it’s a journey. To keep your team energized, celebrate progress along the way:

• A staff member who leads a great initiative that embodies the mission? Highlight it.

• A student project that reflects your values? Showcase it.

• A new tradition that aligns with your mission? Make it a big deal.

These moments remind everyone that the mission is more than just words—it’s alive and evolving.

6. Don’t

Be Afraid to Rewrite the Mission

Sometimes, the problem isn’t that you’ve strayed from your mission—it’s that your mission doesn’t fully fit who you are anymore. Schools grow, change, and evolve, and it’s okay for your mission to do the same.

• Revisit your mission with your leadership team and community. Does it still reflect your school’s identity and aspirations?

• If not, refine it. Make it meaningful, relevant, and achievable.

• Once you’ve refreshed it, make it a focal point in your school’s culture.

7. Lead with Vulnerability and Humor

As a leader, you set the tone for how your school approaches this process. If you’re overwhelmed or defensive, your team will pick up on it. Instead, be vulnerable. Say things like:

• “I know we’ve drifted, but we’re going to bring it back, step by step.”

• “No school is perfect, but we have the heart and the talent to realign.”

• “Let’s face it—this mission has been more wall art than action plan lately, but we’re fixing that!”

Humor and humility can go a long way in keeping morale up and getting everyone on board.

Hope is Not Lost

Losing sight of your school’s mission isn’t the end—it’s an opportunity to pause, reflect, and rebuild. Every great school has moments of doubt or drift, but the best ones don’t give up. They face the challenge head-on, leaning into their community, their purpose, and their potential.

So if you’re feeling overwhelmed or unsure about how to bring your school back in alignment with its mission, don’t lose hope. There’s a path forward. It won’t be perfect, it won’t be fast, but it will be worth it. And when you get there, your school will be stronger, more focused, and more authentic than ever.

If you’ve made it this far, you care deeply about your school and the people in it. And that’s the most important ingredient in making your mission a reality. You’ve got this.

About the Author

Lianne Dominguez is the SS Deputy Head at Haileybury Astana Kazakhstan. A Thought Leader in Human-centered School Leadership, Student Well-being,Teaching and Learning, and Education Innovation

Teaching Students to Think Like Historians

National History Day program honors Matt Elms from Singapore American School

By Suzie Boss

Matt Elms, a middle school social studies teacher at Singapore American School, has been named Teacher of the Year by National History Day (NHD), recognizing his longtime efforts to promote the nonprofit program among international schools. NHD sponsors an annual competition that engages as many as half a million students from grades 6-12 to take on the role of historian and have their work judged by professionals.

Elms presented a popular session at the EARCOS Teachers Conference in March, where he shared strategies for engaging students in the research, analysis, and writing that goes into successful projects. I also had a chance to talk with him about his efforts to promote the program internationally. Here are the highlights of our conversation.

Photo credit: Matt Elms, https://nhd.org/en/

How did you get started with National History Day?

I started in 1995 when I was teaching in Washington State. My kids needed a challenge—something to give them a reason to invest in academics. Later, when I came to Singapore American School, I started NHD as an after-school program. Now it’s a class. Students can choose to take NHD or more traditional social studies in 8th grade.

How has the program grown internationally?

Growth takes time and requires teacher experience with the program. With colleagues at other international schools, we started an affiliate program that has become NHD International. [Matt is the coordinator.] We’ve had students enter from South Africa, Finland, Canada, Turkey, across Southeast Asia—really, from all around the world. We’re seeing teachers across the region who can support students to produce quality projects.

What do students learn through the program?

It’s about the reading, the writing, and the research that goes into a project. This is structured academic writing—whether students decide to produce a paper, exhibit, website, documentary, or performance. They have to pick a topic that relates to the annual contest theme. They have to cite and annotate their sources. They understand the difference between a statement of fact and analysis. They learn to revise and improve their work with feedback. They learn how to connect with mentors and experts.

What are some of your teaching strategies?

My job is to make sure their arguments, thesis statements, evidence, and layout of their project are in alignment. I teach students document analysis and have them use old-school notebooks. Even though they all have computers, the act of writing things down physically

EARCOS UPCOMING EVENTS

The Imperfect Leader: On Becoming & Belonging

Presented by: Liz Cho

Saturday, February 8, 2025

helps them use previous lessons as a resource. I offer mini-lessons on specific topics when I see a few students struggling.

What has helped you improve your craft?

Summer workshops at Columbia University changed the ballgame for me as a writing teacher and project manager. And I’ve learned lessons from experience—sometimes hard lessons, when projects didn’t go so well. Working with colleagues and instructional coaches at my school, and listening to other National History Day teachers, have guided my thinking when creating lessons.

What advice can you offer other schools?

International schools use different models. NHD can be offered as an after-school program, but it’s hard to provide students with the support they need when it’s an activity. The advantage of offering NHD as a class is time—time to teach document analysis, time to write and revise essays, time and space for kids to think. NHD is not just about the projects; it’s about the learning process.

You need to have others in your school on board. I work with the English teachers so we know what each other is doing. I keep the curriculum department informed so they can bring ideas to me. The librarian provides books that students need and offers quiet space for students to conduct videoconferences with experts. My administration supports me throughout the process. The SAS Foundation has provided funding. Success takes a whole community.

How about parents?

You have to have open communication with parents. They need to know that NHD is hard, very hard! They also need to know that not all kids will win, even if they put all their effort into their project. Those experiences are important in life.

Registration for NHD International opens in January for the 2025 NHD with virtual judging for international schools starting in late February. Students who reach the finals will compete in College Park, Maryland, in June. The NHD Theme for 2025 is Rights and Responsibilities in History. More information, including extensive resources for teachers, is available from NHD.org.

Session IV: Common misconceptions, mistakes and pitfalls in implementation

Presented by: Dr. Ying Chu

Thursday, February 13, 2025

>> Reserve your slot now. click here

Recess for All: Creating an Inclusive Playground Experience

By Logan Grove Marketing Specialist

Concordia International School Hanoi

At our school, we believe that recess is more than just a break from classes; it’s a crucial part of how our students grow and learn. That’s why we started our “Recess for All” initiative, which aims to make sure every student can join in on the fun, feeling comfortable and included.

We want every child to have the chance to participate in activities they enjoy, whether that’s a competitive game of soccer or an exciting round of hide-and-go-seek. Our playground is filled with options that cater to all interests and abilities. Whether students prefer team sports or solo play, we encourage them to explore what makes them happy. We also mix things up with some structured activities led by teachers, while still allowing plenty of time for unstructured play. Inclusivity is at the heart of our approach. We often remind our students that everyone is included and that saying “You can’t play” is simply not allowed. Instead, we invite everyone to join in whatever game they choose.

Taking care of our shared resources is another important lesson we teach. We encourage students to borrow toys and games, take care of them, and return them in good condition. Our motto is simple:

“We borrow it. We take care of it. We return it.” This helps instill a sense of responsibility and respect for the playground.

“The addition of new toys has encouraged students to play together, fostering stronger connections and friendships while developing essential social skills like sharing, cooperation, teamwork, and problem-solving. The wider variety of toys has made students more active and engaged.

The selection caters to diverse interests—some students enjoy physical play with bikes and scooters, while others prefer calmer, creative activities like drawing with sidewalk chalk or using sand toys. Additionally, students can use their imagination to invent their own games with the equipment. This diverse range of toys ensures that all students can enjoy recess, regardless of their interests or abilities.”

- Ms. Louise Graham, Reception Teacher

We provide a range of toys in our play spaces to appeal to different tastes.

Fair play is also essential in our recess philosophy. We emphasize respect for one another, taking turns, and playing safely. Following the rules not only makes games more enjoyable but also helps everyone feel valued and included. If something goes missing, we teach students to tell an adult right away so we can find it together.

So why is recess so important? It turns out that taking a break to play outside can actually improve learning! Studies show that recess enhances classroom engagement, reduces disruptive behavior, lowers stress levels, and boosts memory and concentration. Plus, it helps students discover physical activities they enjoy, which can lead to lifelong habits of staying active.

development by giving kids opportunities to practice self-awareness and relationship skills while making responsible decisions. The playground truly becomes a space where social-emotional learning happens naturally.

“Our elementary school uses a conscious discipline approach that lends itself to students and teachers using common, respectful language for problem-solving during playtimes. Students are learning to communicate in a way that fosters self-confidence and respect for others, even when they have differing ideas and opinions. The result is a playground culture that encourages communication, self-regulation, and empathy, empowering students to navigate challenges with kindness and understanding.” - Mrs. Emily Turner-Williams, Reception Teacher

Over the past couple of years, we’ve made some exciting changes to enhance our recess experience even further. We’ve added more toys and games, especially for our indoor play spaces. This year, we’ve introduced new tricycles and even set up a little gas station for imaginative play! In the spirit of giving back to our community, we donated old equipment while bringing in fresh new items for everyone to enjoy.

Recess is vital for teaching kids not just about physical activity but also about social skills and responsibility. By creating an inclusive environment where every child feels welcome to participate, we’re helping our students develop into well-rounded individuals ready for whatever comes next. Let’s keep promoting active play and inclusivity on our playgrounds!

Recess should be inclusive, and we encourage children to play together and work together Recess also supports social-emotional

Engaging Host Country National Teachers

By Robert Preston Williams, PhD & Jayson W. Richardson, PhD

Little research has been done on host country national teachers who work in international schools. Instead, existing research has primarily focused on expatriates (Bunnell & Poole, 2023). Our previous investigations revealed stratification between host country nationals and expatriates (see Williams & Richardson, 2023). As such, we talked with 12 Vietnamese host country national teachers across three international schools in Vietnam to better understand their lived experiences. The themes from those interviews are explored below.

Challenges of Being a Host Country National in an International School

The host country nationals reported feeling less valued than expatriates, which created teaching challenges. According to participants, the emphasis of their international school’s curriculum was English-based subjects taught by expatriate teachers. As host country nationals taught host country studies in the local language, this did not align with parents’ motivations for sending their children to an international school. Additionally, administrators, who were also expatriates, did not understand the local language and rarely visited host country nationals’ classrooms. As a result, host country nationals felt disrespected by parents and ignored by administrators.

One participant said, “You’re less important than foreigners,” which has upset her since she

began her career in international schools. She went on to say, “Oh my God, I would cry many times” because of how students’ parents treated her. Another participant gave reasons why parents preferred expatriates to host country nationals:

The parents like people with white skin and yellow hair. Parents admire people from developed countries. They have white skin and yellow hair, and they’re big and tall.

Parents perceived host country studies as a necessary annoyance. According to one participant, the parents in her international school “don’t really want their kids to speak Vietnamese and to learn Vietnamese,” but Vietnamese language instruction is required due to government mandates. Parents requested that their children transfer out of host country studies in favor of “more popular” subjects. Because students with foreign passports were not required to take host country studies, they had time to take other subjects, which caused frustration among parents, a frustration which they directed toward host country national teachers.

Participants brought up parent-teacher conferences as a prime example of when they felt disrespected by parents. One participant recounted the disappointed looks on parents’ faces when they discovered their child’s homeroom teacher was a host country national. An-

other participant described teaching the same students for over five years, only to be ignored by parents during parent-teacher conferences year after year.

Participants also reported feeling ignored by their administrators. They discussed feeling like administrators did not care what was happening in their classroom.There was little oversight and no feedback from administrators because they did not speak the language of instruction. When asked about administrators’ support, one participant said it is “a very sad thing because they don’t care.” Participants also spoke of receiving less instructional time than other subjects, and they struggled to meet the mandated government curriculum when given the bare minimum teaching time.

Host Country Nationals’ Interactions with Expatriates

Discussions with host country nationals revealed that interactions with expatriates happen in formal settings, such as collaboration time and pre-arranged meetings. For participants, these interactions felt transactional rather than relational. Participants described how interactions only focused on work where expatriates put no effort into learning about host country nationals’ personal lives. Since English was the de facto language of formal meetings, participants felt disadvantaged when sharing ideas. Host country nationals discussed how they remained silent in meetings rather

than deal with the struggles of speaking English. “We just don’t talk because we are afraid that people will laugh at us,” said one participant. While there were minimal interactions outside of formal settings, the participants recognized the value expatriates placed on their personal relationships in international schools.

Due to limited informal interactions, host country nationals felt disadvantaged in comparison to expatriates when trying to build strong relationships with administrators. One participant reflected on the principal’s interactions with expatriate teachers.

Whenever they see each other, they talk a lot, they spend a lot of time talking. But for me, when I see the leadership, when I say hello to her, she just passes by.

Participants believed strong relationships were a factor in expatriates receiving promotions over host country nationals.

Because expatriates were transient, participants avoided building relationships with them. Host country nationals had long tenures in their international schools and spent time building relationships with each other. On the other hand, expatriate teachers worked for a few years and then moved on. In the past, one participant tried building relationships with expatriates but no longer tries because:

We’ll build memorable experiences together and then goodbye. Then I feel a big loss, like people die because they never see each other again.

Feelings about Split Benefits Structure

We found mixed feelings about the differences in benefits between host country nationals and expatriates. Participants understood why expatriates receive better benefits than host country nationals. As one participant said, expatriates “have to work far from their home; they have to move to another country to work.” Participants recognized hardships associated with moving overseas and understood that expatriates received higher salaries due to their limited supply.

Participants did not understand why the gap between benefits was so large and cited that the gap has grown more prominent over time. One participant said, “I do not understand why the gap is so huge. We teach in the same school, share the same responsibilities, and do the same tasks.” When describing the gap, participants used words such as “sadness,” “disappointed,” “depressed,” “angry,” “frustrated,” and “unfair.”

For example, participants were confused about why host country nationals received fewer sick days than expatriate teachers. They also did not understand why their children were not allowed to attend the international school for free when expatriates received this benefit. When participants reported these concerns to human resources, they were told that host country nationals have a degree from the host country which is considered less valuable, and teachers are paid according to their passport.

Moving Forward

In our discussions with host country nationals, suggestions for improving their working conditions emerged. Leaders of international schools can address many of the issues discussed by participants in this study.

• Teaching and learning. Participants expressed frustration with having little to no access to teaching assistants in their classrooms. Because expatriates use teaching assistants for translation, administrators might assume that host country national teachers can do this independently. However, host country nationals stressed that they are still language teachers and need support with differentiated instruction.

• Curriculum development. Host country nationals had little support from their curriculum coordinator, who only focused on English-based subjects. One participant said teaching her subject was challenging because she could not see the curriculum “vertically and horizontally across the grade level.”

• Leadership opportunities. Participants reiterated that they did not get proper feedback on their teaching practice and would like to receive feedback from a department leader who is a host country national. Participants also called for leadership to be shared among expatriates and host country nationals so the latter could help the former understand the local culture and maintain the host country’s heritage. Participants’ motivation for leadership positions was not higher salaries or power but rather representation.

• Opportunities for collaboration. School leaders might create opportunities for interactions with host country national nationals and expatriates. Leaders can model this behavior by directly engaging more deeply with host country nationals to build strong relationships. Given the long tenure of host country nationals, there is likely institutional knowledge that leadership can tap into. Given the recent trend of more students from the

local population attending international schools (Bunnell, 2019), host country nationals could act as a bridge between these students and expatriate teachers.

• ‘Equalize’ benefits. Participants recognized why expatriate teachers receive higher salaries than host country nationals but were more upset about their benefits package being dramatically less. Changes may need to happen externally via accreditation bodies such as the Council of International Schools to ensure equity among host country nationals and expatriates. As more international schools commit to diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ), it would behoove school leaders to include host country nationals.

References

Bunnell, T. (2019). International school and education in the new era: Emerging issues. Emerald.

Bunnell, T., &Poole, A. (2023). International schools in China and teacher turnover: The need for a more nuanced approach towards precarity reflecting agency. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 43(2),463-478. doi: https://doi.org /10.1080/02188791.2021.1940840

Williams, R. P., & Richardson J. W. (2023). Using social network analysis to compare Vietnamese and expatriate teachers’ interactions within Vietnam’s growing international schools. Vietnam Journal of Education, 7(3), 276-287. https://doi. org/10.52296/vje.2023.302

About the Authors

Robert Preston Williams, PhD has been teaching in international schools for over 12 years in China, Costa Rica, South Korea, and Vietnam. He joined YK Pao School in 2024 and teaches in the IB Diploma Program. His research focuses on international teachers, international school growth, educational leadership, and social network analysis.

Jayson W. Richardson, PhD is a professor of educational leadership at William & Mary in the United States. He teaches research methods, educational leadership, foundations of educational leadership, and technology leadership. His research focuses on digital technologies and their impact on school leadership, transformation, innovation, and the student experience. His primary interest is exploring how school administrators lead deeper learning, innovative schools that prepare future-ready students.

UWCSEA’s Path to a More Streamlined and Personalised Admissions Enquiry Experience

By Lucie Snape, Head of Marketing & Communications, United World College South East Asia and Maryanne Lechleiter, Principal Consultant at the Maryanne Lechleiter Consulting Group

The Opportunity

U

nited World College of South East Asia (UWCSEA) is a leading international school in Singapore. It became the second global member of the UWC Movement in 1971 when it was opened by Singapore’s Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, as Singapore International School (SIS). In 1975, SIS was renamed United World College of South East Asia, and it has since grown into a K–12 international school with close to 6,000 students and more than 1,200 staff across two campuses.

Throughout the school year, UWCSEA Admissions engages prospective families through various channels, including inquiry management, campus tours, overseas visits, online webinars, and in-person Open Day events. The team processes thousands of applications each year, with the College community welcoming hundreds of new families every August and a smaller number in January.

With the prospective family experience central to operations, an opportunity arose to enhance the current processes and systems to improve the family experience while increasing back-end efficiencies through both technology and better data management. A key focus was to maintain “the human connection”, identified as essential to any proposed solution.

The Approach

The UWCSEA Marketing and Communications team and Maryanne Lechleiter, engaged and collaborated with key stakeholders across the college to develop a long-term strategy for streamlining Admissions inquiries. In simple terms, the project involved three key steps:

1. Identify pain points.

2. Address “low-hanging fruit.”

3. Plan and build for longevity and scale.

These steps corresponded to the three phases of the project:

• Phase 1: Enquiry Management Automation

• Phase 2: API Development and Implementation

• Phase 3: Enrolment and Communication Management Strategy This article focuses on Phase 1: Enquiry Management Automation,

which addressed a “low-hanging fruit pain point” for both Admissions and families.

The Execution

We began by holding discussions that helped us create a comprehensive wish list of criteria, categorised by stakeholder groups. We defined our success by determining what each group should know, think, and feel throughout their interactions and job functions.

We put ourselves in the family’s shoes, asking what we would want to experience from the college if making an inquiry. What would make us feel “seen”? What barriers might exist? We analysed Admissions survey data and compiled our understanding of the prospective parent experience.

We then considered the challenge from the College’s perspective, focusing on what our Admissions Officers (AOs) need to perform their roles effectively, and what the MarComms team needs to nurture families through the admissions pipeline.

We spent many hours discussing the current enquiry management process, identifying challenges, auditing existing content, and defining how we wanted to segment our audiences.

Key challenges identified included manual responses, a lack of personalisation, and difficulty tracking inquiries. The team also recognised content gaps and the need for better audience segmentation.

The outcome was a strategy to revamp the inquiry management process by removing manual responses at the first touchpoint and creating an automated, multi-level framework of emails with personalised content designed to:

• Provide families with an immediate response to their queries.

• Create a trackable contact record in the CRM system.

• Encourage families to share more about themselves, allowing for greater relevance and connection as they progress through their admissions journey.

To achieve our goals, we began by changing how families can make an admissions enquiry at the college. We removed the linked email address and updated the admissions inquiry form on the website to include specific questions, enabling immediate audience segmentation.

The team utilized the “thank you” page to delve deeper into the family’s preferences, particularly their interests, by asking them questions about their interests. While this step is optional, we found that 66% of families completed the form immediately, and 38% of those who did not complete it initially did so after receiving an automated email reminder.

One of the most significant changes we made was to the format of the inquiry response email. We crafted personalised, visually appealing emails that organised information in an easy-to-consume format, allowing recipients to either skim the content or explore topics of interest in more detail.

The email response configurations are prioritised and categorised by the order in which they are delivered, with four levels available to families, ranging from general inquiries to specific interests and learning needs.

In total, there are 31 different email response configurations. A family may receive several emails depending on their choices, and the team determined that it would be a better experience to receive multiple, topic-specific emails rather than one lengthy message.

All the information provided in these emails is available on the College website, however, this approach delivers the relevant information quickly and directly to the user’s inbox, saving them time and effort.

The entire process is managed via workflows set up in Hubspot and triggered by responses on the inquiry forms, which then branch accordingly. Setting up these workflows was complex and required extensive testing and iteration. Together, the MarComms and Admissions teams conducted rigorous testing, running different scenarios and combinations of responses to ensure the accuracy of the workflows before launch.

The final step before launching was to train the AO’s on the new process and its impact on their work. By integrating the enquiry form data with the Admissions system, we began to form a more complete picture of the prospective family and student’s interests, allowing AO’s to share more relevant information about the College with their assigned families. This speaks to the human connection that is central to the UWCSEA Admissions experience.

The Results (so far)

Since launching earlier this year, we have measured results based on two key factors: families’ engagement with the Admissions inquiry content, and the increased efficiency of the Admissions Team in managing the inquiry process.

The data is favourable and supports our first KPI; families are interacting with the forms and engaging with the content. In just under five months, 2,509 inquiries were submitted and initially managed by our automated process, with an email open rate of 82%. Our 13 workflows were deployed over 16,000 times, as families could be enrolled in multiple workflows depending on their form submissions.

Phase One is just the beginning of this three-phase project and we will continue to refine our strategy and explore new ways to engage prospective families while tracking the success of our efforts. We look forward to sharing more on this exciting project with you.

AI IN EDUCATION: A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON TRANSFORMATIVE POTENTIAL

By Dr. Rolly Alfonso-Maiquez Director of Educational Technology & Innovation and Data Protection Officer

VERSO International School, Bangkok, Thailand

Transformative AI Applications in Education

During a recent summer holiday, I ventured outside of traditional routine tourism by creating my own "expert tourist guide GPT" using OpenAI's technology. Through careful and iterative nuanced prompting and fact-checking, I developed AI-curated walking tours that led me to discover hidden gems such as Melk in Austria, Esztergom and Kiskunfélegyháza in Hungary and Trenčín in Slovakia. These AI-guided adventures revealed cultural narratives I might have missed had I chosen to follow the usual touristy routes. This experience inspired me to think differently about AI's possibilities in the world of education.

While myriad online discussions and webinars often center on AI's obvious applications such as automated assessments and adaptive learning, my travel experiences highlighted its potential to uncover deeper, transformative possibilities. Following are eight key areas where I believe AI is positioned to revolutionize education:

1. Evolution of Creativity

At VERSO International School, our "IM-PERMANENCE" art exhibition demonstrated AI's impact on creativity. In the project, our high school students collaborated with AI to create mixed media artworks exploring philosophical concepts through descriptive phenomenological deep dives. This unconventional project challenged traditional notions of creativity, showing how AI can serve as both a tool and a creative partner. Students learned to navigate a new creative landscape where human imagination and machine capabilities intertwined, leading to innovative expressions that may not have been possible through traditional media alone.

2. Enhancing Student Success

AI is revolutionizing student support through comprehensive monitoring and intervention systems that catch struggling students before they fall through the cracks. These systems identify patterns in academic performance, attendance and engagement that might signal various challenges - from learning difficulties and neurodiversity to social-emotional needs. Unlike traditional support systems that rely on formal diagnosis, AI may be designed to detect subtle indicators across multiple domains, track changes in writing patterns that might indicate emotional stress, analyze social interactions that suggest developing anxiety, or identify specific learning challenges. This proactive approach enables targeted support before issues develop further, creating a more inclusive environment for all students.

3. Redefining Academic Integrity

As AI writing tools become more sophisticated, the line between assistance and cheating gets blurry.This evolution requires shifting from content memorization to critical thinking and practical knowledge application. Schools should develop new frameworks for academic integrity that acknowledge AI's role while maintaining high standards for original thinking, teaching students to use AI responsibly and understanding the difference between enhancement and dependence.

“As we navigate these transformative areas, we will need to be attentive and present in guiding AI integration thoughtfully and ethically, keeping learner well-being on high focus”

4. Classroom Transformation