Celebrating the Abundance of Local Foods in Southern Wisconsin

Celebrating the Abundance of Local Foods in Southern Wisconsin

46

FALL 2021

American Wine Project • Soup’s On • Food Justice • Gathering Together

At Veridian Homes, quality isn’t just a word. It’s our mission.

And it’s evident in every nook and cranny of our homes. We only build with the best Earth-friendly materials available. We only work with individuals who take pride in the craftsmanship of homebuilding. Yes, we sweat each and every detail. The end result: award-winning homes built with expert craftsmanship and the finest green materials. That’s Quality 360. That’s a Veridian home.

WEB:

DESIGN STUDIO: 6801 South Towne Drive, Madison, WI, 53713

VeridianHomes.com PH: 608.226.3000

Photos of the Acacia Ridge furnished model.

resilience

“[A resilient local food system] looks like the people who eat food. It recognizes their cultural needs and how that translates to health and happiness. There is not just one food story, there are as many as there are cultures and communities and they should all be respected and valued.” — HEDI RUDD

NOTABLE EDIBLES by Emma Waldinger

RECIPE INDEX

NOURISH Home Sweet Sorghum by Laura Poe Mathes

THE EYE OF PROVIDENCE by Amy Wulz

HUNGER HAS NO HOME HERE Community Action Coalition Fights for Food Security by Emily McCluhan

FOODWAYS Uncanny Repercussions by Hannah Wente

SOURCING RESILIENCE by Jonnah Perkins

COOK AT HOME Bowls of Nourishment by Lauren Rudersdorf

CONNECTION & COMMUNITY: BACK ON THE MENU by Marissa DeGroot

RETHINKING HUNGER Why Feeding Those in Need Must Focus on Nourishment by Joy Manning

Enos Farm. Photo by Ray + Kelly Photography

Cover: Roasted Cherry Tomato & Fennel Soup. Photo by Sunny Frantz. Dishware from The Mulberry Pottery. Table linens from Convivio in Spring Green. See page 37 for the recipe!

6

11

12

15

20

26

30

35

42

46

54

57

SUPPORTERS

LAST BITE

Above:

FALL 2021 • ISSUE

46

MARISSA DEGROOT

Marissa is a freelance writer, graphic designer and fur baby mom. She never thought she would end up on a farm but now can’t imagine her life not living and working on Vitruvian, her husband’s organic vegetable and mushroom farm in McFarland. Marissa loves a good story, great food and random animal facts. Did you know a group of wombats is called a wisdom?

SUNNY FRANTZ

Sunny is an editorial and commercial photographer with a studio on the west side of Madison where she lives with her husband, their two kids and a tiny dog. She specializes in food and product photography and loves the opportunity it gives her to connect with the many wonderful businesses and entrepreneurs in Madison.

TRACY HARRIS

Tracy is a graphic designer and photographer from Madison. A polymath at heart, she dabbles in various arenas of makery including cooking and baking, sewing and knitting, painting and collage, and has a soft spot in her heart for film photography. When she’s not busy making things, she enjoys travel, good food and drinks, gardening and live music.

EMILY MCCLUHAN

Emily is a Madison-based writer, runner, volunteer and dog mom. Her contributions to regional publications in Michigan, Montana and Wisconsin over the last 20 years provide an outlet for her insatiable curiosity and passion for telling the stories that open our eyes and connect to our everyday lives.

NICOLE PEASLEE

Nicole is a graphic designer, photographer and artist from Madison. She enjoys being a cat mom, going on long walks and listening to podcasts, watercolor painting, and spending time with friends and family. She is also a co-founder of New Fashioned Sobriety, an alcohol-free community based in Madison which hosts monthly meetups and events.

JONNAH PERKINS

Jonnah is a writer, farmer, food activist and competitive athlete based in southern Wisconsin. After over a decade of organic agriculture, Jonnah’s passion for local food has spilled into hunting, fishing and foraging to experience the richest spectrum of emotions in her pursuit of localism. Her curiosity is focused on the intersection of environmentalism, food procurement and adventure. @_.jonnah, jonnahperkins.com

ODESSA PIPER

Odessa is the founder of L’Etoile in Madison. She is a mentor to Taliesin’s Food Artisan Immersion Program, and Consulting Chef to the Savanna Institute.

LAURA POE MATHES

Laura is a registered dietician in private practice, focused on healing with real foods and herbs. She loves to spread knowledge and enthusiasm for great food, and teach traditional cooking and fermentation classes around the region. Originally from Missouri, Laura lives in Viroqua and now understands why cheese curds are a thing. She also loves to canoe, drink coffee and watch stand-up comedy.

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren Langtim

PUBLISHERS

Christy McKenzie

Cricket Redman

BUSINESS MANAGER

Christy McKenzie

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Cricket Redman

LAYOUT Nicole Peaslee

COPY EDITOR

Andrea Debbink

CULINARY ADVISOR

Christy McKenzie

SOCIAL & DIGITAL PRODUCER

Lauren Rudersdorf

ADVERTISING, SPONSORSHIPS & EVENTS Lauren Rudersdorf laurenr@ediblemadison.com

CONTACT US

Edible Madison 4313 Somerset Lane Madison, WI 53711 hello@ediblemadison.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Subscription are available beginning at $35 annually. Learn more at ediblemadison.com/subscribe

We want to hear your comments and ideas. To write to the editor, use the mailing address above or email hello@ediblemadison.com.

Edible Madison is published quarterly by Forager Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used without written permission by the publisher. ©2021. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our sincere apologies and notify us. Thank you.

VISIT US ONLINE AT EDIBLE MADISON.COM

2 • FALL 2021 CONTRIBUTORS

LAUREN RUDERSDORF

Lauren owns and operates Raleigh’s Hillside Farm outside of Evansville with her husband Kyle. Together they manage ten acres for their growing CSA and hemp businesses. When she’s not out in the fields, Lauren shares seasonal recipes on her blog The Leek & The Carrot

EMMA WALDINGER

Emma (she/her) is a writer, grower and maker based in Madison. She cherishes warm summer memories spent at her grandparents’ hobby farm and harvesting from her family’s backyard vegetable garden. These experiences have been the catalyst for her fascination with the intersections between art, ecology, agriculture and good food. When she’s not dreaming of the perfect cake, Emma helps to produce community events at Pasture and Plenty.

HANNAH WENTE

Hannah grew up as a 4-H kid on the shores of Lake Michigan. She is a freelance writer and graphic designer based in Madison. In her previous role as communications director for REAP Food Group, she helped launch the new statewide Farm Fresh Atlas project and supported farm-to-school and farm-to-business efforts. When she’s not gardening, cooking or baking, you can find her playing ultimate frisbee or paddling the nearest lake.

AMY WULZ

Amy has worked in the wine industry for the last 10 years. She is a WSET Level II Wines Graduate with Distinction, a Certified Wine Steward, and a Certified Specialist of Wine candidate with the Society of Wine Educators. She has worked as a tasting consultant, wine tasting associate and Wine Educator.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 3 Sign up for our monthly newsletter The Beet to get the latest news and offerings at EDIBLEMADISON.COM Keep up with us between issues on instagram @ediblemadison on facebook /ediblemadison on twitter @EdibleMadison

1 2 3 September is Eat Local Month at Willy Street Co op , and Co op members can save big on local products. Save up to $50 on local product sales, PLUS every day in September, Load Up On Local and take 10% off all local products in your cart — including sale items! — when you buy at least $50 worth of local products. From vegetables to milk to meat to bodycare to prepared foods and more, you have plenty of local products to choose from! LOAD UP ON LOCAL willy street co op Look for the purple tags, which tell you it’s local! Everyone Welcome! www.willystreet.coop WILLY EAST: 1221 Williamson St., Madison, WI WILLY WEST: 6825 University Ave., Middleton, WI WILLY NORTH: 2817 N Sherman Ave., Madison, WI Not a member? Not a problem! Become one today for $10 and start getting the benefits of Co op Ownership.

Fall may have more devotees than any other season, for obvious reasons. The trees put on a colorful show. The cooling weather is bittersweet—a welcome break from the heat of summer, and yet we cherish each nice day even more because we know those days are numbered as fall fades into winter. Oh, and then there’s the whole fall harvest thing—at no other time of year can we appreciate the earth’s bounty so well!

In this season of bounty, we also want to take time to reflect on our food system and how it works (or doesn’t work) for everyone in our region.

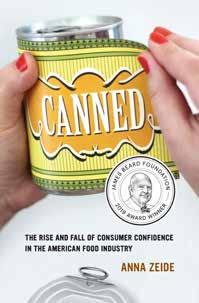

Our intent for this issue is to focus on food justice. In the following pages you’ll find fresh perspectives on the state of our food system from a variety of food justice leaders within our community (p. 9) , as well as an in-depth look at Community Action Coalition’s work in the world of food insecurity in south central Wisconsin (p. 20). Also, Hannah Wente interviews Dr. Anna Zeide, a food studies professor who received her Ph.D. from UW–Madison and won a James Beard Award in 2019 for her book, Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry (p. 26).

As the busy summer winds down, we’re looking forward to embracing cooler nights and cozier meals. To that end, Lauren Rudersdorf has gathered an all-star collection of soup and stew recipes to help us welcome the changing season (p. 35). Also, don’t miss the beautiful bread from some of our favorite local bakers paired with each bowl of comfort. As we all know, the right hunk of bread can take a bowl of soup and turn it into a big, satisfying meal.

Our bread obsession continues in Last Bite at the back of the magazine, which spotlights Madison Sourdough (p. 57). If you live in the Madison area and haven’t experienced a slice of Madison Sourdough fresh from the toaster and smothered in an indecent amount of butter, I’m not sure what to say to you. It may be time to reevaluate your priorities in life. We are on this earth for such a short time! Put this magazine down right now and go get yourself a loaf.

Let’s dig in!

Lauren Langtim Managing Editor

P.S. As always, we welcome your thoughts and feedback. Drop us a line at hello@ediblemadison.com.

4 • FALL 2021

A portion of the proceeds from the event will benefit Community Action Coalition of South Central Wisconsin

More information at ediblemadison.com/celebratefall

Get every issue of mailed right to your door!

Join a community of eaters who are passionate about the health of our foodshed. Your donation supports your local food system.

Join a community of eaters who are passionate about the health of our foodshed. Your donation supports your local food system.

Get every issue of mailed right to your door!

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 5

We’re savin g you a seat! Please join us to toast the Fall Issue of at American Wine Project 802 Ridge Street, Mineral Point Saturday September 25, 4-7pm Sandwiches and cheese plates available for pre-order from Fromagination

Doing the Work Leaders

in Food Justice

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed deep fissures in our food systems from the global scale to the local. Now, with a greater public awareness of the iniquities and challenges with the food supply chain from seed to kitchen, pivotal strides for food justice are within reach— if we take this opportunity to deepen our commitment to our local foodscapes and champion the work and local voices for change.

George Reistad Business Development Specialist, Food Systems for the City of Madison

Donale Richards

Founder of Madtown Food Services and UrbanPonics, Associate Policy Director at the Michael Fields Agricultural Institute

We asked leaders in local food work to share their thoughts on the food system and their role in it. To start the conversation, we invited Madison-based policy maker George Reistad (GR) and entrepreneur Donale Richards (DR) to reflect on the current state of our food system as it adapts to this post-pandemic landscape. For the full version of their conversation and more from each leader, check out ediblemadison.com

GR: I think the current food system is in a state of flux at all levels. The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare some of the issues that have long persisted within the food system, mainly the rigidity of key components of the system like supply chains and distribution, the capacity limits of storage (especially cold storage), and the ability (or inability) to re-adapt and process food meant for wholesale to serve households in need.

DR: The food system, whether you look at it locally or globally, is broken and it has been well before COVID-19. It just happens that people are now understanding what their food system looks like and what their role is. To be resilient, it’s critical to educate folks on their local food system, like who grows your food, who processes your food, where are your local markets, and how does your money impact how new businesses navigate their place in the local economy.

GR: It is heartening to see organizations and institutions take note of these problems during the pandemic and invest, mobilize and adapt accordingly. The attention being given to these issues at the highest levels of government—through funding opportunities from the USDA and other pertinent agencies—as well as philanthropic organizations at the national, state and local level suggest to me that if and when we find ourselves in another societal calamity, our boots-on-theground organizations will have access to more resources that enable them to serve more residents.

Hedi Rudd

Deputy Director of South Madison Programs, Rooted rootedwi.org

“Locally and nationally, we are starting to see a lifting up and an unearthing of the history of food in America and the ways that BIPOC people have flavored our palate, taught us to grow and prepare food, and how they are sustaining our system currently.”

Helen Sarakinos

Executive Director, REAP Food Group reapfoodgroup.org

“I think we’ve spent a lot of time in Wisconsin thinking about sustainable food systems. But it’s time to invest in making our food system more just...we have a responsibility as an organization to let our historically marginalized community partners voice what they need and then work to help them resource their solutions.”

Elena Terry

Founder and Executive Chef, Wild Bearies wildbearies.org

“There is a deeper connection to our foods when you know who produces them, who cares for them, and who advocates for them.”

Mariela Quesada Centeno

Cooperative Manager, Roots4Change Cooperative roots4change.coop/en/farm-to-families-fund

“Seeing the health disparities and the social disparities and the financial disparities and the labor disparities that our sisters and brothers are facing while they are harvesting, milking, producing, cooking, cleaning and consuming the food that not only this state, but that this country consumes, was striking, but it was not a surprise. The Latino labor force has been used as a commodity for years in this country.”

6 • FALL 2021

NOTABLE EDIBLES EMMA WALDINGER

Jeanette Burlingame

Program Manager, Community Hunger Solutions community-hunger-solutions.org

“Understanding that food justice won’t be achieved through free food distribution alone, CHS plans long-term projects around supporting existing systems and creating new ones that work to find solutions to food access issues.”

Chris Brockel

Project Coordinator, Healthy Food for All hffadane.org

“It is truly unconscionable that, in a foodrich city surrounded by prime agriculture, we should have any issues with access.”

WHAT THESE FOOD LEADERS LOVE TO EAT

Foods from the South Madison Farmers Market, TradeRoots, Artemis Provisions & Cheese, M&J Jamaican Kitch’n, Café Costa Rica, Mishqui, Les Délices de Awa, Ahan, Finca Coffee, El Sabor de Puebla. —

Food made by local people who honor their cultures. — Hedi Rudd

The ones that people have put their heart into... farmers markets, small businesses, and local producers. — Elena Terry

Watercress pulled out of a cold running spring in late winter and then tossed into a wonderful peppery salad. — Chris Brockel

Language to Empower

A Food Justice Glossary

Foodways are the habits and practices of a people, region or historical period relating to the production and consumption of food.

Food security/access is the physical, social and economic access to food that meets a person or community’s dietary needs at all times.

Food apartheid From New York-based farmer and food justice leader Karen Washington, food apartheid is the social inequalities that make healthy, culturally-appropriate food inaccessible to certain communities.

Food justice recognizes that hunger, diet-related illnesses, poor agricultural working conditions, and limited access to fresh, culturally-relevant foods disproportionately affect marginalized groups.

Food agency empowers an individual or a community to navigate their physical, social and economic environment to confidently source and prepare food that meets their cultural and dietary needs.

Food sovereignty is a group or community’s right to define their own food and agriculture systems, and as it relates to Indigenous peoples, the right to protect culturally-relevant ecosystems, seeds and food procurement practices.

Resilience as it relates to the food system is the supply chain’s ability to respond and recover from disturbances to the pathways that connect producers and consumers.

Supercharge! Food Microgreens and anything grown by Robert Pierce. — George Reistad

Donale Richards

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 7

Keep Your Table Colorful When the Weather Cools

Carrie Sedlak, Executive Director at FairShare CSA Coalition, suggests participating in a late-season or storage CSA share to squeeze the last drop of summer out of your cool weather cooking:

“Signing up to be a fall or winter CSA member—or both!—is a meaningful way to support our local farmers throughout the entire year. And it means that you get to bring fresh, tasty and nutritious local produce to your doorstep all the way through January! There is nothing like cooking a holiday feast with 100% local veggies. The flavor and concept is beyond compare. We are fortunate to have a great number of talented organic CSA farmers serving our region and this is one of the easiest and most enjoyable ways to make a direct connection to the farmers and the delicious fruits of their labor.”

Find the late-season share that best fits your taste by exploring FairShare’s Farm Search tool: csacoalition.org/farm-search Need some culinary inspiration for your hibernation bounty? Check out our website for hearty recipes to keep you warm when the chill sets in: ediblemadison.com/recipes

Fall storage share from Winterfell Acres.

8 • FALL 2021

GARVER FEED MILL • 3241 GARVER GREEN, MADISON

and

a

at

Learn about Ayurveda

book

retreat

KOSASPA.COM retreat for resilience

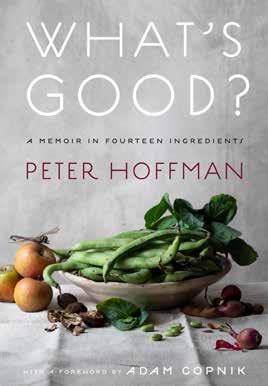

BOOK REVIEW: WHAT’S GOOD? A MEMOIR IN FOURTEEN INGREDIENTS

BY PETER HOFFMAN by Odessa Piper

BY PETER HOFFMAN by Odessa Piper

“Organic” can apply to the growing of relationships as well as vegetables. Peter Hoffman lays it out like he’s happy to be prepping dinner with us; the stories are riveting and the meal will be fabulous. We follow his rise from a callow cook who becomes a wise chef, able to sustain a groundbreaking restaurant in NYC for two decades, writing op-eds in the The New York Times along the way. As for the cooking, there’s a lot more than 14 ingredients that shine in Hoffman’s lens. When he explains the full life cycle of a plant, you come to understand how to unleash the trace miracles of taste in your own ingredients.

Hoffman’s deep knowledge of markets and farms applies easily to our own markets in Dane County and the Driftless region. Indeed, his colorful stories of struggle and restaurant dramas will seem eerily familiar to food-besotted Madison.

olbrichgleam.org

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 9

ART IN A NEW LIGHT Artists from around the country (and beyond!) illuminate the Gardens after dark with site-specific light installations that swing, fly, flutter, and float! While exploring this year’s exhibit, you can step into the world of infinity and

the

to unlock the rainbow.

Don’t delay! Get your tickets today! Advanced timed tickets are required.

Exhibit Viewings September 1–October 30 Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays & Saturdays 7:30–10:30 pm in September 6:30–10:30 pm in October Last admission issued at 10 pm. Shine Bright — Volunteer! Looking for a fun, easy volunteer opportunity in the evening? Connect with Marty to learn more: mpetillo@cityofmadison.com

Peter Hoffman, author of What’s Good?

learn

secret

olbrichgleam.org

10 • FALL 2021 >> while-you-wait sharpening of knives, scissors, and garden tools any day but Sunday 3236 B University Avenue, Madison, WI 53705 · www.wisconsincutlery.com

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 11 FALL 2021 RECIPE INDEX SWEET Sorghum Bread Pudding ...... 14 SAVORY Carotene Spirit ............. 36 Roasted Cherry Tomato & Fennel Soup ............. 37 Cranberry Bean Stew ........ 38 Roasted Squash Soup ........ 40 WANT MORE FALL RECIPES? HOP ONLINE AT EDIBLEMADISON.COM/RECIPES and sign up for our monthly E-Newsletter Roasted Beet Sandwich with Fennel Salad & Feta from Lauren Rudersdorf Roasted Butternut Squash with Maple Chipotle Butter Roasted Carmen Pepper Pimento Grilled Cheese Maple Pumpkin Cobbler Heirloom Apple Pie

Home Sweet Sorghum

NOURISH LAURA POE MATHES

So many wonderful foods come from Wisconsin, which is a huge part of what makes living here so special and desirable. While we have plenty of local fare to offer—dairy, of course, meats, vegetables, fruits, grains and nuts, Wisconsin also produces several whole-food, natural sweeteners. Most folks are familiar with our abundant maple syrup and ambrosial honey, but a third sweetener can be found here: sorghum molasses. Also known as sorghum syrup, this liquid sweetener may be more obscure than its locally produced cousins, maple syrup and honey, but it is every bit as delicious. Sorghum syrup is more prevalent in southern cuisine, so as a Missouri girl turned Wisconsinite, I was so pleased to learn that not only can I buy it here, there are even some brands that are grown and produced locally! I want to shine a little light on this sticky sweet nectar and spread the word of this amazing local natural sweetener.

Sorghum is a grain-like grass that can be used for making foods for human consumption, or it can be used as feed for animals and even ethanol production. One variety, also known as milo, is grown for its seed. Milo is used as a grain for cooking, often turned into flour and used in gluten-free baking products as a substitute for wheat. Another variety of sorghum is called sweet sorghum, which is the plant the sweetener is made from. Sorghum grows in warm, dry climates, such as the southeast and plains regions of the US, but can be grown in some parts of Wisconsin, with certain varieties such as Sugar Drip and Rox Orange working better in our shorter growing season.

It is important to acknowledge where many foods originated and how they arrived in our region, in addition to celebrating and appreciating them as part of our current local food offerings. Sorghum is not native to the US, but originally came here from Africa following slave trade routes, along with other valued crops like peanuts, rice, sesame seeds, black-eyed peas

and okra. Sorghum grew in popularity as a sweetener in the 1860s when the Civil War disrupted trade and cut off the sugarcane supply from the Carribean, leading Americans to produce their own sweeteners. Sorghum eventually became part of Southern food culture in the United States, and we can now enjoy it in our neck of the woods as well.

While sorghum syrup is not as common as it once was, there are some areas of the country where syrup production continues today. The molasses you are likely familiar with is the byproduct of making granulated sugar from sugar cane, but sorghum molasses is made in its own unique way. In the fall, when the sorghum is ripe and ready to harvest, the stalks, also known as canes, are cut and pressed using a roller mill to extract the sweet juice inside; this is traditionally done with horses or mules to turn the mill. This juice is then cooked down, until it is thick and dark. When ready, the syrup has an appearance and consistency much like molasses made from sugar cane. Smaller-scale producers and Amish communities often still use traditional methods using livestock and wood-fire to make sorghum syrup, but larger businesses will often use modernized processes and equipment like those used in commercial maple syrup production. Either way, the result is delicious.

Sorghum molasses can be used much like cane sugar-based molasses or maple syrup in cooking. On the sweet side, it goes beautifully in cookies (hello, chewy molasses cookies!), sweet breads, homemade granola, candies, and pies like shoofly pie, or drizzled on biscuits, pancakes, waffles, oatmeal, sweet potatoes or baked apples. In savory dishes, sorghum can be used to add a bit of sweetness to sauces like BBQ sauce, marinades and glazes for meats, baked beans, and savory breads like cornbread or pumpernickel. Anywhere you might use molasses or other liquid sweeteners, you can typically use sorghum syrup

12 • FALL 2021

instead. Sorghum molasses has a stronger flavor and is slightly less sweet than some other sweeteners, so be careful if trying to swap this one-for-one with other sweeteners and use it to taste.

I like to use this sweetener not only because it is locally-produced and has an earthy, delicious flavor, but also because it has a high mineral content and can actually provide some nutrients along with its sweetness. Sorghum syrup, similar to maple syrup, provides antioxidants and minerals like iron, zinc, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus and potassium. While it is still sugar and is best consumed in moderation, it does have the extra benefit of some nutrition.

Like so many other great foods grown in Wisconsin, I recommend checking your area farmers markets,

Amish stores or other independent retailers that offer local food items, such as food co-ops, to get your hands on some sorghum molasses. Most brands available in the area are small producers that can be found at farmers markets or roadside stands, such as the tasty nectar from Down Home Farm in Viroqua. Rolling Hills Sorghum out of Elkhart Lake is the biggest sorghum producer in Wisconsin and can be found at many local food retailers. Even Old Sugar Distillery in Madison is getting in on the action. They use Wisconsin sorghum to make their Queen Jennie whiskey, so even your favorite cocktail can be turned local—here I come, sorghum whiskey old fashioned! Whether in your favorite beverage or autumn comfort food, get cozied up this season with some local sorghum syrup.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 13

Interested in exploring more about sorghum? 18 SEPTEMBER SORGHUM FEST 2021 9am - 4pm | Free Admission Savanna Oaks Community Center Columbus, WI 53925 Learn more about sorghum, see sorghum processing, sample sorghum treats while exploring crafts, antiques and inflatables for children.

Sorghum Bread Pudding

Bread pudding is comfort food at its finest, and my version showcases a variety of foods produced right here in Wisconsin. Drizzle with a splash of cream to serve and pair it with a hot cup of coffee for breakfast or have as a dessert on a cool fall evening. Just be sure to use highquality sourdough bread—local bakeries I’m loving right now include Origin Breads, Madison Sourdough, One Love, and Rhythm Bakery—to make this the best bread pudding you’ve ever had.

serves 8 prep time: 20 minutes cook time: 60 minutes

INGREDIENTS

8 eggs

1½ cups whole milk

½ cup heavy cream

4 tablespoons butter, melted

1/3 cup sorghum molasses, plus extra for drizzling

2–4 tablespoons maple syrup, adjust to your sweetness preference

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

½ teaspoon sea salt

1 tablespoon cinnamon

¼ teaspoon each: nutmeg and allspice

1 loaf day-old sourdough bread (use a crusty hearthstyle loaf if you can find it), cut into 2” cubes

½ cup dried cranberries, cherries or raisins

1 cup chopped hazelnuts (can substitute walnuts, almonds or pecans)

DIRECTIONS

1. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. Grease a 9x13 baking dish with butter.

2. In a large bowl, whisk together the eggs, milk, cream, butter, sorghum, vanilla, sea salt, cinnamon, nutmeg and allspice. Whisk until well combined.

3. Add the cubed bread to the egg batter and stir well. Let sit for 30–60 minutes to soak up the batter a bit.

4. Fold in the dried fruit and nuts to evenly incorporate. Pour the mixture into the prepared pan. Cover with foil and bake for 45 minutes. Uncover and bake for 15 more minutes until the top becomes golden and a bit crispy.

5. Remove the bread pudding from the oven and drizzle it with a bit more sorghum and a pinch of sea salt. Let sit 10–15 minutes before serving; I recommend serving warm for the best flavor and texture, but this can be served the next day too.

14 • FALL 2021

Photo by Sunny Frantz

the eye of providence

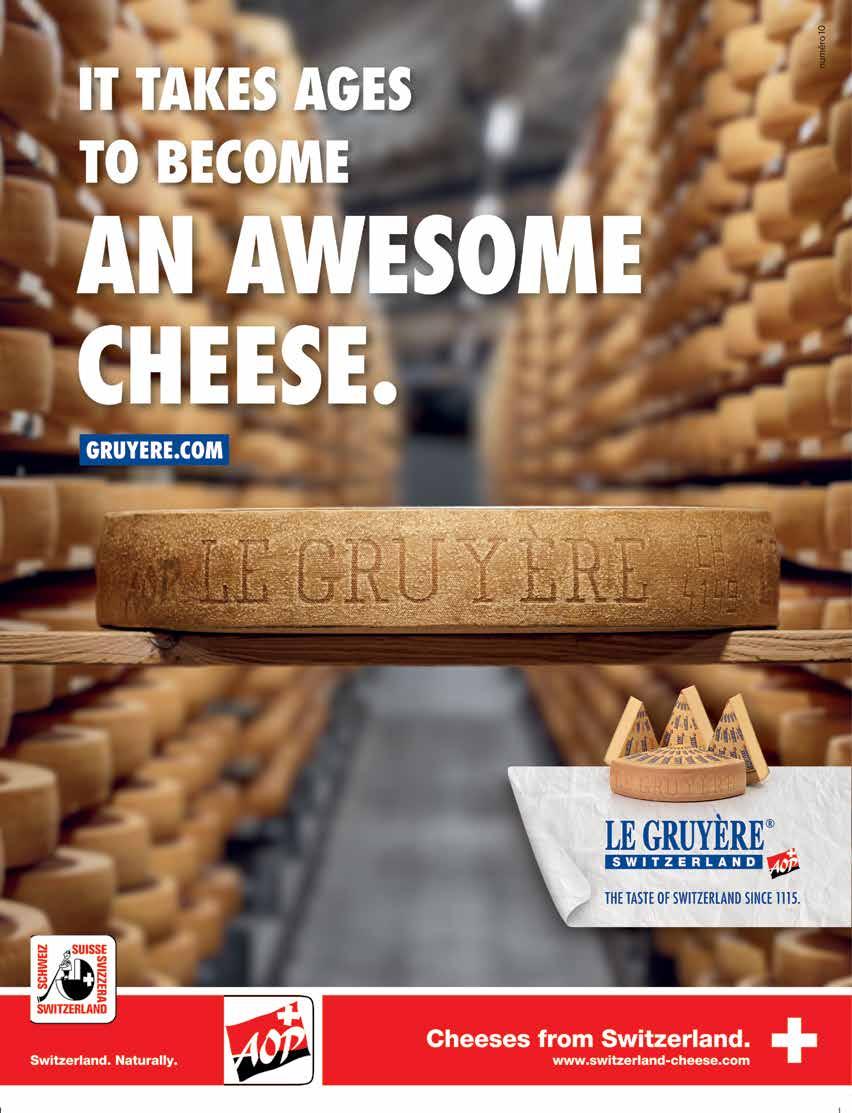

American Wine Project Winery and Tasting Room opens in Mineral Point

by Amy Wulz

by Amy Wulz

Fall is not only harvest time for local farms and orchards, it’s also the busiest season for the region’s vineyards. Despite the challenges of growing wine grapes in Wisconsin’s climate, viticulture and wine-making have a 175-year history in the state. Today’s winemakers, however, have more options than their predecessors thanks to newer hybrid varieties that can withstand harsh Midwestern winters. Although hybrid grapes have their own wine-making complexities, they are nonetheless, very tasty. With wine-making knowledge and innovative technologies also evolving, the overall quality of these wines has greatly improved. In the 1970s and ‘80s, a few dedicated growers including Elmer Swenson developed cultivars such as St. Croix, St. Pepin and Brianna, which were co-developed with University of Minnesota. In the past few years, the University of Minnesota has released more promising grape varietals including

Frontenac, La Crescent, Marquette and Frontenac Gris, and spurred more interest in wine-making in the upper Midwest.

Erin Rasmussen is a winemaker who has made it her personal mission to showcase lesser-known Midwest hybrid varietal wines at her new Mineral Point winery, American Wine Project. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin–Madison with a degree in music, Erin earned her advanced degree in Viticulture and Enology from Lincoln University in New Zealand. Then she spent 10 years working as a winemaker in New Zealand, Napa and Sonoma California for wineries such as Larkmead and Gallo. During a trip to field taste during pinot harvest in Napa, Erin was invited to sample some “interesting new varietals from the Midwest” at a nearby winery. At first taste she was immediately inspired and realized that she could make interesting wines closer to home.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 15

Photo by Tracy Harris

16 • FALL 2021

Above left: Erin Rasmussen, AWP founder and winemaker. Above right: Erin describes the business’s logo, the symbol known as the “Eye of Providence,” as “very American.” She says “it represents the unknown and encourages us to be curious and to experiment. After all, every time you make wine, it’s an experiment. Opposite page: The winery offers tastings of their available wines alongside signature spritzers made with one of their two piquettes in one of the seating areas inside the winery.

Photos by Tracy Harris

She returned to her Wisconsin roots in 2017 to take on the challenge of making cold-climate wines. “I really feel in the upper Midwest there are things we can do in winemaking that the West Coast winemakers can’t,” Erin says “It’s also important to appreciate the hybrid grapes for their uniqueness and not compare them to European varietals. They are capable of making delicious, complex and age-worthy wines.”

Erin doesn’t currently own her own vineyard, but it’s part of her 5-year plan. “The Driftless region is the front door to great grape-growing,” Erin explains. She currently purchases grapes from several growers around the Midwest for her winery, including a few in the Driftless region. American Wine Project currently has 12 wines available for tasting, by the glass or by the bottle, with two new wines planned for the 2021 harvest. Each of the artistic labels, from flamingos to fly-fishing, displays what Erin hopes “primes you for what’s inside the bottle and takes you on a journey with the wine.” A couple titles hint at her musical talents. Erin describes the business’s logo, the symbol known as the “Eye of Providence,” as “very American.” She says “it represents the unknown and encourages us to be curious and to experiment. After all, every time you make wine, it’s an experiment.”

A basket press is used during the pressing stage of the wine making process, which is a true labor of love. This type of winepress is used to extract juice from crushed grapes during wine-making and although more time-consuming, it is a gentler process, extracting less of the bitter compounds from red grape skins, therefore resulting in a softer wine. Erin prefers low intervention in the cellars to craft wines in a dry style. “I want the fruit to tell its own story.” The wines complete a second fermentation to soften the tart acids that are common in hybrid grapes, then age in oak barrels to become rounder and softer.

Wine flights (small samples of different wines) are chosen at the counter then taken to your seat to enjoy at your own pace. Erin hopes you contemplate the wines and interact with others around you. “Talk about the wines and create memories.” Erin plans to be a familiar face in the tasting area, greeting guests and sharing her passion for winemaking and the Wisconsin experience.

In choosing wines, Erin says if you’re uncomfortable with Wisconsin wines, try Sympathetic Magic made from 100% Marquette grapes, and for those looking for something European, taste the Sound of Memory, an earthy flavored Marechal Foch wine. If you prefer something that goes down easy, she recommends the Ancestral Petillant Naturel with its delicate sparkling style made from Brianna grapes, but if you’re a trendsetter, she advises you dive into the Light Verse White Piquette with its rustic savory quality and tongue prickling tartness. She claims the 2020 vintage made some great wines. Her passion is contagious and it’s evident as she talks about her wines. AWP will also carry some interesting local beers and serve a curated selection of food pairings. “We want to have something for everyone,” Erin adds.

The winery building, once used as an industrial arts shop for the local high school, then a garden nursery, has been transformed again through significant renovations while retaining its industrial vibe. The tasting room has high ceilings and cement floors, both on Erin’s must-have list when searching for a home for her new winery. The exposed ductwork, natural wood accents and large windows that invite the light inside give the space an inviting and organic feel. There are a variety of seating options, a cozy wall fireplace, and a stocked library shelf for curious readers, making this a great destination for a solo date with your journal or a birthday party with friends. “My goal is to make it comfortable, relaxing and welcoming for everyone. I want people to come and hang out. I guess it’s

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 17

a community space gussied up as a winery” she chuckles. “Being able to enjoy the winery and taste our wines during all four seasons of the year will be a classic Wisconsin experience.”

The winery’s large outside patio is filled with umbrella-clad tables and a shady arbor waiting for those who’d like to taste or sip outdoors. Erin encourages you to wander the garden with wine in hand to explore the restored flower beds and native plantings that line the pond. Paths wind through the expansive garden with lawn chairs and benches just inviting you to linger. Lawn games are set up and ready to make your visit a family-friendly event. Tours are also available by appointment.

The efficient and knowledgeable staff, led by Anna Freundle, Hospitality and Tasting Room Manager, are there to ensure the best experience possible for visitors. AWP is also a family affair. Erin’s dad, Dave Rasmussen, plays the roles of business consultant, accountant and “Head Carpenter”at the winery, alongside his day-gig as a president of a software company in Madison. Erin’s mom, Mary, wrote a USDA grant in collaboration with the City of Mineral Point to secure federal funding to support the business. She also reigns as “Garden Manager,” maintaining and beautifying the gardens surrounding the winery. She’s always happy to have an extra set of hands—if you have a green thumb, check out the benefits of their Garden Club.

Erin’s commitment to the community is evident through her thoughtful renovations and uses of her new winery space. Her innovative spirit, hard work and enthusiasm has created a welcoming winery space and many delicious wines for all to enjoy. American Wine Project should be on everyone’s list to visit.

— Erin Rasmussen

18 • FALL 2021

“The Driftless region is the front door to great grape-growing.”

Clockwise from above: The grounds and gardens include a small pond with benches, picnic tables on the patio, native gardens to wander and plenty of space for bocce, cornhole and picnic blankets for lingering while you taste the wines.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 19

Hunger Has No Home Here

COMMUNITY ACTION COALITION FIGHTS FOR FOOD SECURITY

by Emily McCluhan

Dawn Bradshaw never thought she would be homeless, but in 2011 when the landlord of her Madison apartment sold the building, she struggled to find an affordable alternative that would also allow her 105-pound dog. She moved into a camper on a friend’s property in Reedsburg and tackled the daunting task of figuring out what services could help her stay on her feet. Facing the embarrassment and stigma that shrouds food insecurity, she stepped into a food pantry for the first time.

Photo by Nicole Peaslee

Photo by Nicole Peaslee

“It takes so much energy to walk into a food pantry. I kept thinking that this can’t be for me; this isn’t how it’s supposed to be,” Bradshaw says.

She was part of the more than 10% of Dane County residents struggling for their next meal in 2011, a number that declined to around 8% in 2019 then jumped back to 10% during the pandemic in 2020, as those who were one paycheck away from going hungry began losing jobs.

Now, as the Food Security Program Director for Community Action Coalition (CAC) for South Central Wisconsin, Bradshaw says that time in her life pushed her to this place to help others.

Bradshaw explains that the CAC fits in the middle of the food security supply chain. As a food bank, the CAC receives or purchases bulk and packaged food from food wholesalers like Certco, food retailers like Festival Foods, and restaurants like Panera, Ian’s Pizza and the Great Dane. The food is then distributed for free to food pantries, shelters, meal programs, senior housing and more.

Started in 1966 as the Community Action Commission of Dane County and the City of Madison, the group added Jefferson County in 1992 and Waukesha County in 1996. CAC is one of 16 agencies that are part of the Wisconsin Community Action Program Association (WISCAP). The program focuses on all aspects of anti-poverty services, from food and housing security, to health and wellness education and financial literacy.

“As a food bank we have a larger purchasing power since we’re buying in larger quantities,” Bradshaw says. “As opposed to a food pantry or meal program that may only be buying for 300 people. That’s one reason we offer all of our services for free to our network—it helps the programs we work with focus on providing food to those who need it instead of purchasing it.”

She notes that not every food bank is structured the same way. For example, CAC serves three counties with all food offered at zero cost. Second Harvest of South Central Wisconsin—also a food bank—serves 16 counties as part of Feeding America, the country’s largest network of food banks, and charges pantries a nominal fee.

Also, no food bank or pantry can charge those in need for the food they receive. However, food banks can charge the pantries and meal programs that receive food a maintenance fee of up to 19 cents per pound for collecting, storing and distributing the food. According to its website, about 30% of Second Harvest’s food distributed to its partner agencies do not incur shared maintenance fees.

CAC relies on funding from federal grants, United Way–Dane County and private donations to waive all fees for its nearly 60 partner sites in Dane County, plus various locations in Waukesha and Jefferson County. Thirty-nine of those sites

have the tools or knowledge to choose food for their specific populations,” says Bradshaw. “I try to reinforce with the groups we work with that they need to choose foods based on who they are serving, not their own likes and dislikes.”

pounds just from retail food stores like Festival.

“Yes, sometimes it’s a little banged up, but it’s important to know that while some of the perishable food might be past its sell date, it’s not past the use by date,” says Bradshaw. “Some people think we’re kind of a garbage disposal, but our volunteers and staff always make sure that we’re providing food that we ourselves would eat. We want to make sure that there’s dignity involved.”

in Dane County are part of The Emergency Food Assistance Program, or TEFAP, funded by the USDA. CAC is the administrator of this program for south central Wisconsin.

“TEFAP supplements the diets of low-income Americans by providing shelf-stable food at no cost,” says Bradshaw. CAC receives from five to seven truckloads of food from the USDA each month and distributes it to their network of pantries and programs. TEFAP funds also pay the salaries of the small staff of eight at CAC.

Since the food comes from the USDA, Bradshaw says it’s 100% American-produced, but it comes with extra layers of regulations related to storage, employee and volunteer training, and how quickly the food is distributed.

The sites themselves have to make sure there is food available at all times at no cost to recipients since it is for emergency situations. And while it would be easy to box up meals to move the product faster, Bradshaw says that TEFAP is very clear about giving folks a choice in what they receive.

“They’re trying to remove the stigma of going to a food pantry and just taking what you’re given. They want to make sure it feels more like grocery shopping,” she says.

The other goal of providing choice is to reduce waste. If an item goes in a box that a recipient doesn’t want, it often goes in the trash or comes back as a donation. By allowing volunteers or staff from partner sites to choose what they stock their shelves with, the hope is that waste is reduced. And given that many households that face food insecurity are minorities (18.7% in the Black community and 28% of Latinos live in poverty across the U.S.), CAC is putting a focus on making available what Bradshaw calls “culturally competent” food choices.

“Everyone that does this work is doing it for the right reasons, but sometimes they don’t

Besides the truckloads of food received for TEFAP, CAC also has a team of over 50 volunteers called Gleaners that handle food recovery. Most food banks rely on food recovery from grocery stores, restaurants and local businesses to stock their shelves, and CAC is no different. However, Bradshaw says that most of the food recovery by the Gleaners is delivered directly to non-TEFAP locations in their network like YWCA, St. Vincent de Paul and the Salvation Army. Last year CAC recovered over 25,000 pounds of food from restaurants and businesses, and over 247,000

Getting all of this food out the door and onto pantry shelves or into meal program kitchens is the responsibility of Catie Badsing, Sustainable Food System Coordinator at CAC. She coordinates two teams of two that work every day to deliver to pantries and shelters across the threecounty area. A few larger pantries may get two truckloads in a day, while other smaller locations like churches or community centers are loaded onto one truck.

In addition to a complex distribution network for TEFAP locations and large pantries, CAC also opens its warehouse doors to smaller locations like The Beacon and Badger Rock Neighborhood Center.

The Double Dollars program offers a dollar for dollar match for all SNAP transactions up to $25 per market day at eight markets within Dane County—more information about this program is available at cacscw.org/services/food-security/double-dollars

22 • FALL 2021

“It takes so much energy to walk into a food pantry. I kept thinking that this can’t be for me; this isn’t how it’s supposed to be…”

Kipp Thomas, culinary program director at Badger Rock, says that coming from the restaurant business, he had no idea that organizations like CAC existed.

“When I started here five years ago, I didn’t know that you could go to a place and they have food that is donated or they purchased it, and they give it to you for free,” says Thomas.

The partnership with CAC grew from Thomas receiving food from CAC to prepare for the monthly family nights at Badger Rock, to a full pantry program during the pandemic.

“As the numbers [of COVID-19 cases] started rising and schools went virtual, we began to realize that students who rely on meals at school may not be getting any meals at all. So we started brainstorming and asking our families what they needed,” says Thomas. Then they turned to CAC.

Typically, Thomas could choose from a specific area of food designated for locations that aren’t part of TEFAP at CAC. Due to an increase in donated and gleaned foods at the food bank, Bradshaw was able to offer him free supplies from the non-TEFAP free food bank. Thomas drove away with a Suburban packed with meat, produce and other pantry items that were overflowing at CAC because of the disruption in the food supply chain during the pandemic.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 23

Photo courtesy of CAC

MORE AT WWW.EMBARKMAPLE.COM

Find us at the Westside Community Market, Madison Farmers Unite, and Dane County Farmers Market, or shop online at honeybeebakery.org

LEARN

Thomas and his team got to work setting up a full pantry at Badger Rock, inventorying their items and allowing families to choose what they wanted in their bags.

“We started with 37 families a week and it trickled up to close to 100 families every week,” says Thomas. “I felt so privileged to have that relationship with CAC; we couldn’t have done it without them.”

Thomas happily shows his gratitude by using the kitchen space at Badger Rock to help CAC repackage bulk food items that are sourced from farmers and wholesalers, or to turn single food components into prepared meals.

From the start to the end of the food security supply chain, organizations like CAC also help individuals and families navigate the applications and requirements for programs like FoodShare, Wisconsin’s federally-funded food assistance program, formerly known as food stamps. CAC takes it a step further and also manages the Double Dollars program, which allows money withdrawn at area farmers markets by FoodShare participants to be matched by CAC, up to $25 for use at that market.

“I love the Double Dollars program. It gets people to go to farmers markets that wouldn’t normally go because they think they can’t afford it,” says Bradshaw. “It benefits everyone, including the vendors. Our low-income folks feel like they’re part of the neighborhood community, plus they have access to fresh fruits and vegetables.”

After the market season, Willy St. Co-op offers the Double Dollars program and helps fund the program through the reusable bag credits offered in their Madison stores. Bradshaw says these monetary donations are the best way to help the CAC.

24 • FALL 2021

CAC staff receiving one of two semi-truckloads of food provided by the federal government for distribution to partnering food pantries across three counties at no cost to pantries or participants.

Photos by Nicole Peaslee

“Food insecurity is deeply personal, and impacts an entire community. Our Food Bank supports local efforts to make sure everyone can access free food with dignity. No one should go hungry in the wealthiest country in the world.”

Bradshaw says she is inspired everyday by her team—most of whom have used the services the CAC supports—as they work tirelessly everyday to help reduce poverty and hunger.

“Food insecurity is deeply personal, and impacts an entire community. Our Food Bank supports local efforts to make sure everyone can access free food with dignity. No one should go hungry in the wealthiest country in the world,” says Amber Duddy, Executive Director.

If you are interested in supporting the work of CAC of South Central Wisconsin, please visit CACSW.org to learn more.

HOME + LIFESTYLE

Thoughtfully considered goods for your everyday. 1925 Monroe St, Madison I gooddayshop.net

BRISBANE HOUSE

Community meals with local chefs Community gardens Family field trips, workshops, and youth garden classes Organic vegetables And so much more! Join us at 502

and at the

for: Visit our website and follow us on

&

to learn more about our work in food, land & learning.

accommodations

rootedwi.org

Troy Drive

Badger Rock Neighborhood Center

Facebook

Instagram

On 18 acres in Arena, Wisconsin On the National Register of Historic Places Historic

now accepting reservations for fall 2021 at airbnb.com/h/brisbanehouse Built in 1868

by Hannah Wente

uncanny repercussions

A Q & A with author and food historian Dr. Anna Zeide

Dr. Anna Zeide is an associate professor of food history at Virginia Tech and she received her PhD from UW-Madison. Her book, Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry, won a James Beard Award in 2019. Lobbying, advertising and experimentation in the canning industry paved the way for processed foods, and understanding the origins of our modern food system could pave the way for food justice today. The way we produce, preserve, distribute and eat food was altered with the rise of canned foods—enabling Americans to eat without ties to season and land. Taking a look back at the story of canned food can help us move forward in building sustainable and equitable foodways.

26 • FALL 2021

FOODWAYS

Hannah Wente: Why is food history important?

Dr. Anna Zeide: A lot of the issues in the current food system are rooted a century or more in the past. There have been a lot of ill-fated attempts, both in the past and present, to change the way people eat for health or environmental reasons, with a real ignorance of how much food matters emotionally, historically and culturally. Food history gives us that sensitivity and awareness to the situational reasons that diets are the way that they are.

HW: Why write about canning?

AZ: My parents are both Russian-Jewish immigrants. I grew up in a small town in Arkansas on 25 acres of woods. And although my family didn’t do home canning, my dad grew a lot of his own food in our garden and my parents did not use American processed foods. My friends had Doritos, Kool-Aid and other brand-name foods that were so present in the ‘80s and ‘90s when I was growing up, and we didn’t really eat those. I grew up very aware of the way food is a marker of culture, identity and insider-outsider status, especially in a town with very few immigrant families. What we eat reflects where we come from. Those early traditions shaped my sense of why food matters and why food choice matters.

My family interest in food led me to write about food history. As I was trying to find a topic within food history, I started to notice that a lot of the biggest food companies today started as canning companies. The story of the canning industry shows how much food production is tied to all other aspects of our culture and economy—you pull one string and everything unravels.

HW: For a first-time reader of your book Canned, what are the key ideas you hope they uncover?

AZ: Looking at the canning industry helps us recognize that taken-for-granted objects like cans of food have such deep histories. Everything we consume, touch, interact

with is the product of lots of people’s time, effort and intentional manipulation. Only through these efforts has canned food become something that we can ignore. Public health officials, marketing specialists, consumer activist groups and industry professionals have all worked together at different times to make it so when we pick up a can or other packaged food off the grocery store shelf, it seems like a really simple act.

My book can also help people understand the role of trade organizations, coalitions across different companies, which otherwise don’t get a lot of attention. The National Canners Association became the Grocery Manufacturers Association, which is one of the major food lobbies today. Because grocery stores drive a lot of demand for production, this group ends up having a lot of power.

HW: Can you talk about the unique relationship between military food and civilian food?

AZ: The U.S. Army stimulated and developed relationships with canners, beginning in the Civil War and peaking during World War II. You had this buildup of infrastructure to support canned and processed food for the war effort and an increase in demand from returning soldiers. A lot of processed foods, including energy bars, instant coffee and TV dinners, got their start as military foods.

HW: You mention the opaque can in your book and people being wary of its contents. What parallels does the rise of canning have with the rise of processed foods?

AZ: The can emerged in the early 19th century when most people still had a real physical tangible connection to food— whether they were growing their own food, getting it from neighbors, or going to local markets. They would evaluate the freshness of the vegetables, meat or bread based on how it smelled, looked and felt. Then food was put in this standardized, hard-walled opaque can. Your senses were no longer involved in the process of experiencing and evaluating food. Instead, all of the cans looked the same and the contents were invisible until you went home and opened it.

Often new innovations require a big marketing push in order for people to say,

“Okay, this thing I never thought of being necessary, is.” By the 1930s, you have the rise of advertising, marketing sciences and branding as a central factor in how people choose their food. Canners were at the forefront of creating national brands and marketing campaigns. These techniques taught consumers to buy based not on that individual experience, but on the trust of the brand name.

That brand name was then associated with other values at the time. From purity—a major push at the turn of the 20th century—to convenience a little later, to “taste of your childhood” and using kids in advertising, all of these were valuable tools in building a market for an industry that was so unfamiliar. I argue that the relationships canners built with collaborators— marketing experts, scientists, public health officials, bacteriologists, university extension agencies and agricultural experiment stations—were the foundation for the processed food products and ways of eating today.

HW: How did the canning industry overcome initial public hesitancy to create a literal, store-bought household staple? How was the industry able to shift how we eat, from growing and preserving one’s own food to buying food at a store that someone else grew?

AZ: By the early 20th century, you have the rise of germ theory and the ability of scientists to point to things under the microscope that were spoiling food and causing sickness. Canners got in on this rising value and acceptance of scientific expertise as a marker of what we trust. At the same time, you had the rise of the federal government. Prior to the Civil War, the federal government had a small role to play in people’s daily lives. The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act is one of the first major examples of a government’s interference in people’s daily lives. The canners promoted and benefited from regulation.

Canned food was emerging as a part of, and maybe emblematic of, a broader sensory

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 27

overload mode of the late 19th century where everything was changing. Cities were growing, railroads were emerging, and communication technologies like the telephone and telegraph were speeding everything up. Canned food fit into that.

HW: How do canned foods help and hinder food justice?

AZ: Industrial food may mean less work for individuals in their homes, but more work for agricultural and factory laborers— the labor is displaced and unseen. Corporations, for whom the bottom line is the major concern, will always make choices that are better for the financial interest of their stockholders, without much attention to public health, worker welfare or environmental problems. Unless, that is, consumers make their voices heard. Food companies are public-facing and consumers buy food products every day. The companies want to appease consumers, on a deep or surface level. We need to keep fighting at the level of our own food practices, and also recognize food as inherently political. Pay attention to state, local and national food policies. Pushing for food to be a platform in national conversations is necessary.

HW: For many, canned food became an unsung hero of the COVID-19 pandemic. People were stocking up on canned food and toilet paper. Any thoughts on what role it can play today and in the future?

AZ: Canned food becomes a go-to when people are prepping for the pandemic or other emergencies. It’s clear that the preservation capabilities of canned food are unmatched. Canned food is really critical to talk about when building local food systems. Especially in places with shorter growing seasons like Wisconsin, eating locally year-round requires food preservation. I think canned food can also be a great way to prevent food waste. During the pandemic, we saw food rotting in fields and people pouring out milk

that was supposed to be in schools. If we had nimble canning apparatuses to help preserve and prevent food waste at the production end, that could be really transformative.

In the Depression era, there were many small-scale canneries located in communities where people could bring large portions of their own foods or garden products to be industrially canned and then people could bring those cans home with them. That’s a cool model—something in between commercial and home canning.

HW: The canning industry drove change in terms of food marketing and lobbying, not necessarily good change, but change nonetheless. Could it be used as a force for good in terms of food justice? You talked about the number of people involved with producing canned food—if there were fair labor practices and fair wages for those workers, could that drive a lot of change in the food industry?

AZ: I think there’s a role that canned food, whether at the individual home level or community level, can play into the future. The way that processed food industries are so influential and embedded in the federal government lobby, grocery stores, and food banks, they do command a lot of connection, power, and control that limit food access and create food injustices. If canning companies saw themselves as more centrally responsible as citizens and not just as corporations they could have enormous positive influence.

Interested in more from this author?

Acquired Tastes: Stories about the Origins of Modern Food is a book of essays on food from the 1880s to 1930s available from MIT Press. It features an essay by Dr. Anna Zeide about Marion Harland, a famous domestic advisor and cookbook author who became a spokeswoman for the canning industry. Look for Dr. Zeide’s new book U.S. History in 15 Foods on shelves in early 2023. She uses iconic foods like milk and condensed milk to illuminate everything from the American Revolution to the Cold War.

28 • FALL 2021

Les Délices de Awa

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 29 Chai Tea Latte 2 tsp Chai tea from Telsaan Tea 1 cup Hot Water 1 cup Milk (warm) 1 Tbsp Rock Sugar Ingredients: Directions: Steep tea in boiling hot water for 3-5 minutes. Strain out the tea leaves. Stir in sugar. Add warm frothy milk. Makes one 16oz serving. Visit us in downtown Mount Horeb or shop online at telsaan.com FB: Food Junkies IG: @foodjunkies365 An eclectic catering service that is serious about good eats. Chef Angela offers a wide variety of menus for you and your crew!

Junkies Catering

Food

A ONE woman business specializing in West African cuisine! Order from Chef Awa for dinner, catering or find her products in local stores. Lesdelicesdeawa.com FB: Les Délices de Awa

FB/IG: JustVeggiez A hopping vegan restaurant & catering service. Chef James shares healthier version of your favorite foods, available for pick up or delivery. JustVeggiez

JustVeggiez.com

sourcing resilience

by Jonnah Perkins

by Jonnah Perkins

Southwestern Wisconsin is known for its patchwork of small farms and craft producers. This is part of the idyllic appeal of the Driftless region. But most of the agricultural economy is still based on food and commodities being imported and exported from the state. While the marketing of food sells us the idea of local sourcing, it is increasingly challenging to understand how our food reaches us.

For Marie and Matt Raboin, owners of Mount Horeb restaurant and cidery Brix Cider, sourcing over 90% of their food from regional producers isn’t only a personal mission, it gives the Raboins a framework on which to curate their menu and cider selection. What Brix offers is so starkly seasonal that it unpretentiously teaches the customer what grows in this regional radius and when.

Orcharding is an historic agricultural tradition in Wisconsin, but with our inconsistent weather, growing apples in the state is a nuanced art. Even though an apple may be delicious, it can have imperfections that make it hard to sell by today’s standard of fruit beauty. Marie and Matt offer local orchards an outlet for their second-quality apples that would otherwise be a loss for the farm. Harvesting from over 25 orchards, including their own, the Raboins see the imperfection as a way to add depth to their small-batch ciders. The harvest from each orchard offers unique characteristics and varieties of apples. This diversity creates the opportunity to get creative with other ingredients the landscape has to offer to play off the flavor profile of each harvest. “I don’t know of many cideries that have been as experimental as we have. We’ve focused

on locally sourced ingredients and we’ve made ciders with saskatoon, currants, elderberries, elderflowers, honey, maple syrup, tart cherries, plums, pears, seaberries, wild bergamot, chile peppers, pumpkin, black cherry, raspberry, black raspberry, blackberry, gin botanicals, basil, and I’m sure I’m forgetting some,” Matt says as he lists off the ways he and Marie have been creative with their cider-making over the years. “We couldn’t do this if we were trying to recreate the same cider each time.”

The care and intention that the Raboins put towards their sourcing doesn’t stop with their cider production. In April 2020, when the couple was faced with hard decisions about how to move through the pandemic, they felt a deep commitment to their farm partners but knew they couldn’t keep the kitchen open. In an all-nighter brainstorm session, Matt and Marie decided they would offer a grocery delivery service to homes in the Mount Horeb area. Essentially, they would keep ordering from their farms and producers, but instead of cooking, they would drop off custom orders throughout the community. This model worked so well that they continue to feature a makeshift grocery store in the restaurant even now that the kitchen is open at full tilt.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 31

Photos by Kelly Kendall Studios

“I don’t know of many cideries that have been as experimental as we have. We’ve focused on locally sourced ingredients...”

“Local sourcing in general does take some effort,” says Marie. But she sees this as an extension of her commitment to her regional foodshed and the farmers with whom she has developed personal relationships. “I know the farmers, they’re my friends. It’s also awesome to write your friends checks. If you’re going to write out a bunch of checks each week, why do it to someone you don’t know and send the money who knows where?”

While the purpose of creating circular economic strength in southwestern Wisconsin is at the core of Brix Cider, the Raboins want this energy to go beyond their own business. This year Brix Cider was awarded a three-year grant through the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service to put structure around the hyper-localized food sourcing model they have created. The grant opportunity has given Matt and Marie the resources to build a team of partners from UW–Madison to create local sourcing impact analysis and outreach events, as well as to work with a local media company to develop a series of short films that illustrate the depth of their farmer-restaurant relationships.

In the food production and service industry ecosystem, scaling up and streamlining the way people eat and drink continues to move toward consolidation of supply chains. What Brix Cider has shown is that the key to stability isn’t knowing what will be on the menu next month, it’s knowing that you’ve got your neighbor’s back and they’ve got yours.

32 • FALL 2021

Left: Marie and Matt Raboin with their two children. Above: Apple harvesting is a family affair for the Raboins. Below: Brix Cider tasting flight made with apples from participating orchards.

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 33 HOURS: Thursday 12-5 pm Friday & Saturday 12-8 pm Sunday 12-5 pm JOIN US FOR A TOUR & TASTING! 30940 OAK RIDGE DRIVE, MUSCODA, WI 608 - 647 - 6600 WILDHILLSWINERY.COM From our vineyard to your table, we infuse every glass of Wild Hills Wine and Cider with the beauty of the Driftless and the home we love. Local = 100 mile radius Viroqua, WI 609 North Main Street • open daily • www.viroquafood.coop Bringing 200+ local producers and community members together since 1995! Local = 100-mile radius

34 • FALL 2021 REAL FOOD. REAL LOCAL. FARM-TO FREEZER stock up on frozen favorites COOK FRESH weekly meal kit delivery and pick-up CURBSIDE PICK-UP order from our menu online (air-fives included) 2433 University Avenue | pastureandplenty.com We are grateful for the opportunity to help you eat well, support local farmers and makers, and protect local jobs. Supporting a strong, resilient local food system is critical for our community’s health and it nourishes you too. PIZZA AL FRESCO HOST YOUR NEXT EVENT WITH CASUAL CUISINE FROM OUR MOBILE PIZZA OVEN

As the days get shorter and the nights cooler, there is no better way to celebrate autumn than with a veggie-packed bowl of soup or stew served in a hand-thrown bowl alongside a slice of locally baked sourdough. Grab a storage share from a local farm (see p. 8 for some inspiration) and spend the next couple months with a ladle full of goodness.

LAUREN RUDERSDORF COOK AT HOME

Carotene Spirit

This recipe offers a new way to enjoy the wholesomeness of golden beets by teasing the natural sweetness out of them. This delightful soup can charm even beet skeptics into devouring a bowl of savory liquid sunshine.

Serves 6-8

Prep time: 15 minutes

Cook time: 1 hour, 30 minutes

INGREDIENTS

4–6 medium-sized golden beets, unpeeled

3 tablespoons olive or sunflower oil, divided

1 medium yellow or white onion, finely chopped

2–3 carrots, finely chopped

2 stalks celery, finely chopped

4–6 medium-sized potatoes (preferably Yukon Gold, but any potatoes will do), cut into ¼-inch cubes

1–2 turnips, cut into ¼-inch cubes

1 small celeriac, cut into ¼-inch cubes

4–5 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon kosher salt, plus more to taste

2 teaspoons black pepper, plus more to taste

2 teaspoons finely chopped fresh parsley, divided

2 teaspoons finely chopped fresh basil

1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh thyme

4 cups water

2 tablespoons lemon juice

Lemon wedges, optional Yogurt, optional

DIRECTIONS

1. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F.

2. Trim and scrub the beets. Coat them with 1 tablespoon of oil and place them whole into a roasting pan with about ½ inch of water. Cover the pan with foil and bake at 400 degrees until the beets are easy to pierce with a fork, about 40–60 minutes.

3. While the beets roast, heat the remaining 2 tablespoons of oil in a Dutch oven or large stock pot over medium heat. Add the onion, carrot and celery. Sauté until the onions begin to turn transparent, about 10 minutes.

4. Add the potatoes, turnips, celeriac, garlic, salt, pepper, basil, thyme and 1 teaspoon of the parsley. Continue to sauté until all the vegetables begin to brown. Add the water and cover; lower heat so the soup maintains a very gentle simmer.

5. Periodically check to see if the beets are tender. Once they are done, remove the beets from the oven and allow them to cool until they are cool enough to hold in your hand. Peel and chop the beets into bitesized pieces. Add to the simmering soup. Season with additional salt and pepper to taste.

6. Once all the vegetables are at the desired level of tenderness, remove the soup from heat and add the lemon juice.

7. Serve warm. Sprinkle bowls with the remaining 1 teaspoon of parsley. Garnish with lemon wedges and/or top with a dollop of yogurt.

Recipe by David Pedersen of Soups I Did It Again

Roasted Cherry Tomato & Fennel Soup

If you’re a home gardener or CSA member, late September is the time that you would be perfectly happy to never see another cherry tomato. With consistent harvests and unbelievable bounty, these treats of summer become a bit mundane by the start of fall. My trick: roast a bunch and turn them into the easiest tomato soup ever (or freeze bags to make this soup over winter). For an extra touch of end-of-summer joy, use sungolds (or another yellow cherry tomato).

Serves 4

Prep time: 5 minutes

Cook time: 1 hour, 15 minutes

INGREDIENTS

1/4 cup olive oil, divided 10 cups cherry tomatoes

1 large yellow onion, quartered

1 1/2 teaspoons kosher salt, divided

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 large fennel 4 cups chicken stock

1/3 cup heavy cream

DIRECTIONS

1. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F.

2. On a large baking sheet, drizzle 2 tablespoons of olive oil. Add cherry tomatoes to the pan in a single layer. Nestle in onion and sprinkle with 1 teaspoon salt and the pepper.

3. Place tomatoes in the oven and roast until the tops are well browned, about 40 minutes.

4. Remove fronds and stalks from the fennel, reserving 1/4 cup of the leaves for stirring into the soup at the end. Cut your fennel bulb in half, remove the core, and thinly slice.

5. In a large stock pot, heat remaining 2 tablespoons of olive oil over medium heat. Add the fennel and remaining 1/2 teaspoon salt. Sauté until softened and fragrant, about 10 minutes.

6. Add tomatoes to the stock pot when they are finished roasting along with the chicken stock. Bring to a boil, reduce to a simmer and cook gently for 10 minutes over low heat.

7. Remove from heat and allow to cool for 10 minutes. Stir in the heavy cream and reserved fennel fronds. Leave the soup chunky or puree with an immersion blender if you prefer a smooth soup.

8. Serve warm with toasted ciabatta slathered in ricotta, salt and garlic powder (optional).

EDIBLEMADISON.COM 37

Recipe by Lauren Rudersdorf Raleigh’s Hillside Farm and The Leek & The Carrot

Photos by Sunny Frantz. Dishware from The Mulberry Pottery . Table linens from Convivio in Spring Green.

Cranberry Bean Stew

Pig farmers and farm-to-table zero-waste caterers Erin Crooks Lynch and Jeremy Lynch of Enos Farms in Spring Green aim to strengthen the local food economy by cooking meals for others just like this Cranberry Bean Stew. The recipe is flexible enough to incorporate whatever the season dictates and relies upon local food producers.

Serves 6-8

Prep time: 15 minutes active / 12 hours inactive

Cook time: 1 hour 30 minutes

INGREDIENTS

1 pound dried cranberry beans

2 bay leaves

5 garlic cloves, divided

1/4 teaspoon red pepper flakes

1 sprig of fresh rosemary or a few sprigs of fresh thyme

2 tablespoons sunflower oil (or olive oil)

1 medium onion, chopped

1/2 cup or 3 ounces guanciale (aka jowl bacon), or bacon or pancetta, diced

2 teaspoons kosher salt, plus more to taste

2 cups (roughly) roasted and chopped tomatoes (or 14.5-16oz canned tomatoes)

Black pepper, to taste

Freshly chopped parsley, optional

Freshly grated hard cheese (such as Pecorino or Parmesan), optional

Fresh bread, optional

DIRECTIONS

1. Rinse beans, checking for pebbles and debris. Soak beans in cold water for 10-12 hours. After soaking, drain and rinse the beans.

2. Add the beans to a large pot and cover with 1 inch of cold water. Add the bay leaves, 2 peeled garlic cloves, red pepper flakes, and rosemary or thyme. Bring to a boil over high heat. Once boiling, reduce the heat to a light simmer. Simmer for 45-60 minutes or until tender.

3. While the beans cook, prepare the rest of the ingredients. In a large skillet, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the onion and cook until fragrant, but not browned, about 10 minutes. Mince the remaining 3 cloves of garlic and add them to the pan along with the guanciale. Sauté until the garlic is fragrant and the guanciale is crisp, about 10 minutes.

4. After the beans have simmered for about 30 minutes, taste a forkful. They should taste about halfway as tender as you’d prefer them to be. Add 2 teaspoons of salt to the pot and stir.

5. As soon as the garlic starts to brown, add 1 cup of the bean cooking liquid and 1½ cups of almostcooked cranberry beans to the pan. Smash the beans in the liquid to make a thick base. Add the tomatoes and their liquid and bring to a simmer. Lower heat so a very gentle simmer is maintained. Stir and add salt and pepper to taste.

6. Once the beans are just tender but not yet mushy, drain off the remaining bean liquid and add the beans to the guanciale mixture. Simmer the soup for an additional 20 minutes. Simmer longer if you need to reduce some of the liquid, or add more liquid (water or stock) if it gets too dry.

7. Sprinkle with fresh herbs and grated cheese. Serve with fresh bread.

38 • FALL 2021

Recipe by Erin Crooks Lynch of Eno Farms

Roasted Squash Soup

Sardine co-owner and chef John Gadau is a master of simple, pureed, flavor-packed soups and this recipe is no exception. Roasted, caramelized butternut squash meets savory spices, brown sugar and apple cider vinegar for a bowl of warmth you can’t stop slurping.

Serves 4–6

Prep time: 10 minutes

Cook time: 1 hour, 45 minutes

INGREDIENTS

6 tablespoons olive oil, divided

1 large butternut squash, cut in half, seeds removed

1 teaspoon kosher salt, divided, plus more to taste

1/4 teaspoon pepper, plus more to taste

4 tablespoons butter, cut into cubes

1/2 medium onion, chopped

2 celery stalks, chopped

2 carrots, chopped

1 bay leaf

3 sprigs fresh thyme

½ teaspoon cinnamon

¼ teaspoon nutmeg

⅛ teaspoon ground cloves

7 cups chicken stock

½ cup heavy cream

¼ cup cider vinegar

¼ cup brown sugar

Chile oil

Prosciutto ribbons

Creme fraiche, optional

DIRECTIONS

1. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F.

2. Grease a large roasting pan or casserole dish with 1 tablespoon of olive oil. Place the squash skin side down and season with ½ teaspoon salt and pepper. Place the butter cubes on top of the squash and cook until the squash is soft and caramelized on top, about 50 minutes.

3. Let the squash cool and scoop out the flesh. Discard the squash skin.

4. In a large pot, heat the remaining olive oil over medium heat. Add the onion, celery and carrots. Cook until softened, about 5 minutes. Add bay leaf, thyme, cinnamon, nutmeg, ground cloves and remaining ½ teaspoon salt. Cook for 1 minute.

5. Add chicken stock, cream and roasted squash to the pot. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer and cook over low heat for 30–35 minutes, stirring periodically to prevent burning on the bottom of the pot.

6. Take the pot off the heat. Remove the bay leaf and thyme sprigs. Ladle the soup into a blender and blend until smooth. Transfer blended soup into a clean pot. Reheat and add cider vinegar and brown sugar. Season to taste with salt and pepper.