NO. 1 SPRING 2022 Member of Edible Communities edible Maritimes

Home Sweet Home

the land ~ the sea ~ the people ~ the food

Hollandaise Sauce

Stovetop: In top of double boiler, whisk together butter, egg yolks, lemon juice and cayenne pepper. Cook over simmering water, stirring constantly until thickened, 10 to 12 minutes.

Microwave: In 4-cup (1 L) glass measure, whisk butter, egg yolks, lemon juice and cayenne pepper. Gradually add melted butter into yolk mixture, whisking constantly. Microwave on Medium (50% power) until sauce thickens, 30 seconds to 1 minute. Whisk halfway through and at end of cooking to produce a smooth sauce. Serve warm.

Eggs

Stovetop Poaching Method: Fill saucepan with 3 inches (8 cm) of water. Add a splash of vinegar. Heat until water simmers. Break cold egg into small dish or saucer.

Classic Eggs Benedict

Makes 8 servings

• Water

• Vinegar

• 8 eggs

• 4 whole wheat English muffins, split and toasted

• 8 slices lean back bacon

Hollandaise Sauce

• 1/2 cup (125 mL) butter, melted

• 3 egg yolks

• 1 tbsp (15 mL)lemon juice

• Pinch cayenne pepper or dry mustard

Holding dish just above water, gently slip egg in, one at a time. Simmer until whites are set and yolks are cooked as desired, 3 to 5 minutes. Remove eggs with slotted spoon and drain well.

Microwave Poaching Method: Pour 1/3 cup (75 mL) water into small deep bowl. Bring to boil on High (100% power). Break eggs, one at a time, and slip into water. Pierce yolk membranes with fork. Cover with plastic wrap, leaving small steam vent. Cook until whites are set and yolk are cooked as desired, 40 to 60 seconds. Let stand, covered, for 1 minute. Remove eggs from bowl and drain well on paper towel.

Top each English muffin half with slice of back bacon, a poached egg and 2 tbsp (30 mL) Hollandaise sauce.

Enjoy!

nsegg.ca eggspei.ca nbegg.ca

in your province for great recipes and more.

Be a good egg! Start your day with a Maritime egg...

Visit the Egg Farmers

May 19 - 22, 2022 St

paddlefestnb.ca

Andrews, NB

Photo by Steadii Creative

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4 HELLO FROM US

5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

6 SPRING BITES

Wild leeks & Simon Thibault's oignons salées

9 IN THE KITCHEN

An interview with chef and restaurant owner Suni Ferreira

15 IT'S SIMPLE, IT'S HARD WORK

Mark and Victoria McGuire make a life as bean-to-bar chocolate makers in a small town by the sea

23 SALT SORCERY ON THE SOUTH SHORE

Kim Kelly and Onya Hogan-Finlay distill the essence of the place

30 IN THE GARDEN

Mark Ellands and Dawn-Marie Matheson on a community-based garden initiative and resilience

35 ON THE SHORE

A conversation with Shane Gills about hard work and quality of life

39 A SWEET FINISH

Alice Burdick puts spring rhubarb in a cloud

40 THE LAST WORD

Wild rice in Wabanaki territory

hello from us

The old adage ‘you can never go home’ suggests our memories of home are simply that – just memories, a place we can't actually return to. We know this isn’t true. A pea pod picked fresh from the garden takes us back to granny's garden, red licorice to that epic road trip. Sitting down around the table with our kids to enjoy a favourite dish, snacking on some of mom’s fruitcake, baking some Snow family molasses cookies, or stopping to share a sandwich on the beach with our dog, we are transported back through time just as we are at home in the present. Food is home. Whether we’re gathering around a grand table or grabbing a quick snack on the road, we are home.

In this issue, our first of edible Maritimes, we bring you stories of people who are making this place their home – and the centrality of food in that process for each of them. From a chef who learned she was a chef through the support of her new community, to a couple who leaned into a passion and found themselves in a small town by the sea, and another who honed in on their relationship with their island home and discovered a new path... from a gardener excited to grow food for his neighbours and a shellfish harvester who found the perfect balance at home. All of these stories and the recipes in this issue highlight the deep connection between food and home, between this place and its people.

The stories in these pages are the stories of the land, the sea, the people, and the food. It’s that simple – and each quarter we will bring you these stories. Thank you for picking up this first issue of edible Maritimes and for joining us as we set out on this food adventure.

Sara & Dave

edible Maritimes

the land ~ the sea ~ the people ~ the food

CO-EDITORS & DESIGNERS

Sara & Dave Snow

CONTRIBUTORS

Hannah Arsenault, Cecelia Brooks, Alice Burdick, Mark Ellands, Suni Ferreira, Onya Hogan-Finlay, Shane Gillis, Chris Googoo, Kim Kelly, Dawn-Marie Matheson, Mark McGuire, Victoria McGuire, Simon Thibault, Kate Walchuk

EDITORIAL CONSULTANT

Jennifer Campbell

THANK YOU

To our children, their partners, our family and friends, and all of you for cheering us on and for coming along for the ride. Special thanks to Tara Simpson and Laurie Kizik for sharing tips and wisdom at every stage.

SUBSCRIBE

edible Maritimes is published 4 times per year + 1 special issue.

Subscriptions are $28 and available at ediblemaritimes.ca.

FIND US ONLINE ediblemaritimes.ca instagram.com/ediblemaritimes

CONTACT US hello@ediblemaritimes.ca

Edible Maritimes

506-639-3117

PUBLISHERS

Sara & Dave Snow

Steadii Creative Inc

No part of this publication may be used without written permission by the publisher. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our sincere apologies and notify us. Thank you, © 2022 Steadii Creative Inc. All rights reserved.

Edible Maritimes is printed in Canada on paper made of material from well-managed, FSC®-certified forests, from recycled materical and other controlled sources.

Please reuse and redistribute this magazine - read it again and again or pass it on!

4 edible MARITIMES

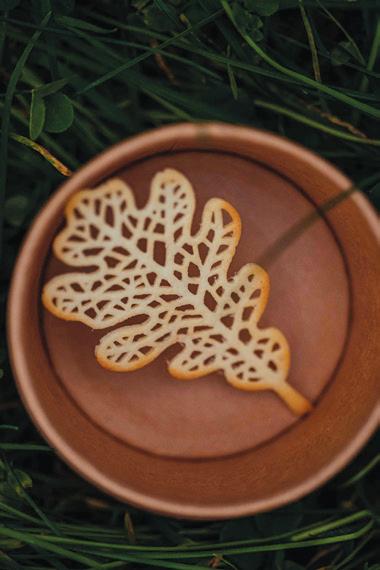

On the cover: Cacao beans with McGuire Chocolate Co chocolate. Photo by Dave Snow.

Kistm ~k wenju’su’n

this apple * is edible

We respectfully acknowledge that we are in Wabanaki territory, on the unsurrendered and unceded traditional lands of the Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. This territory is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship which the Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725 recognizing Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy title. We stand with them in their efforts for land and water protection and restoration, and for cultural healing and recovery.

edible maritimes

*Literally weju’su’n translates as the ‘French man’s apple’ as the Mi’kmaq did not have apples. Thank you to Chris Googoo, Ulnooweg Indigenous Communities Foundation, for this Mi’kmaq translation of ‘edible’.

*Literally weju’su’n translates as the ‘French man’s apple’ as the Mi’kmaq did not have apples. Thank you to Chris Googoo, Ulnooweg Indigenous Communities Foundation, for this Mi’kmaq translation of ‘edible’.

Unfiltered Dry Ciders.

Traditionally crafted without the addition of sugar and sulphites.

www.kingstoncre

Kingston, NB

Spring 2022 7

Oignons salées / Salted green onions

Simon Thibault's recipe is the perfect way to preserve a little springtime.

A green onion plucked fresh from the garden, sprinkled with a little salt... imagine preserving that bright flavour well beyond springtime.

Salting onions and other greens is an age-old tradition among Acadian communities. Oignons salées (salted spring onions, green onions or scallions) or herbes salées (salted summer savoury, thyme, chives and other herbs) can be found in many pantries throughout Acadie.

In his book, Pantry and Palate: Remembering and Rediscovering Acadian Food, Simon Thibault suggests there is no real 'recipe' for salted green onions because, as he writes, "everyone just made it in their homes." Read on, however, and he points out that there is a process. It may vary across families and regions but there is a process. The simplicity of Thibault's approach captures the essence of oniony springtime so perfectly.

We recommend reading Thibault's recipe, for yourself, in his gorgeous book. Like all of the recipes he shares, his oignons salées recipe is imbued with rich cultural heritage, family tradition and a sense of place. You'll also find some sage salting advice from his father.

To make Thibault's Oignons salées / Salted green onions you will need:

Green onions (cleaned and roots removed)

Large-grained salt/kosher salt

Mason jars

Thibault's technique: Chop green onions and mix with enough salt so that the onions are covered. Mix well and repeat with the same amount of salt. Let the onion-salt mixture sit overnight in a cool place.

The next day, add more salt – so that the onions are covered in crystals of salt once again. Pack them into Mason jars and store for up to a year.

Thibault recommends adding oignons salées to "soups, stews, dumplings, rappie pies, fricot or anywhere you need a salty or oniony kick." For an added twist, we suggest trying his recipe with wild leeks. If you are lucky enough to happen upon a few wild leeks this spring, mix them in with your green onions or try salting them on their own.

Simon Thibault's Pantry and Palate: Remembering and Rediscovering Acadian Food is as much a cultural history as it is a beautiful cookbook – a beautiful gift for yourself or the chef in your life.

Simon Thibault is a journalist, food writer, editor, and radio producer based out of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

8 edible MARITIMES

The art of Suni

Weaving the tapestry of spice and community: an interview with chef and restaurant owner Suni Ferreira

in the kitchen

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

When Suni Ferreira and her family left Sri Lanka 12 years ago they had $400 and the bags they could carry. Ferreira didn’t realize it then but she also brought with her a gift, one she now shares with hundreds of people every week from her café in Lunenburg.

While Lamprai & Spice is a one-woman business, Ferreira will tell you it would not be possible without the love and support of her community. She might tell you ‘it takes a village’.

We first heard of Lamprai & Spice from some friends further down the coast. For them, a day trip to Lunenburg is often topped off with Suni’s delicious take-out. One rainy day, we stood in line, waiting in anticipation to go inside and place our order. As the line grew longer, cheers of joy wafted out the door and we knew we were in for something delicious.

Inside, we were greeted by the warm smell of curry, and Ferreira's friendly call from the kitchen. She and her food radiate warmth.

Ferreira’s story is one of community – here in the Maritimes and in Sri Lanka. Until twelve years ago, Suni had spent most of her life in Sri Lanka. Her father was from Sri Lanka. Her mother had spent most of her childhood there after Ferreira’s

Lamprai & Spice is full of warmth. Suni Ferreira greets everyone who walks into her Sri Lankan café like an old friend.

grandfather had set out from Nova Scotia for what was then Ceylon. It was the 1950s and he set off with his young family and a fishing boat. Years later, her mother met her father and they moved to Canada. Ferreira was born in Nova Scotia but her family returned to Sri Lanka when she was still a girl. For a time, there was relative peace in parts of the country but under the threat of growing civil war Ferreira’s family returned to Nova Scotia. Ferreira attended teachers’ college, but it wasn’t long before her heart called her back to Sri Lanka. She married there and she and her husband dedicated their lives to aid work.

Not long after Ferreira gave birth to their son, the tsunami of 2004 hit Sri Lanka. For the next eight years, through battles and ceasefires, peace talks and bombings, Ferreira and her husband helped villagers rebuild their lives. Sri Lanka’s war was declared over in 2009 but in the few months leading up to that declaration tensions mounted and all foreign aid workers were advised to leave. Ferreira and her family had to leave their home and their work, their friends and their community, and board a plane for Nova Scotia.

When we sat down to speak with Ferreira, she talked of how food and community have intertwined her life in Sri Lanka with her new life as a chef on the South Shore. The following is a portion of that conversation.

in the kitchen 10 edible MARITIMES

edible Maritimes: What was it like for you having to leave Sri Lanka and return to Nova Scotia so suddenly?

Suni Ferreira: My mum was here at the time, so it was kind of like coming to my second home. But for a few years, to be honest, I had lost myself. Doing aid work – during the war –my outlook on life had changed. When you’re serving during war time you don’t have time to think about anything, your adrenaline is high and you’re just moving and meeting people’s needs all of the time. It’s just wake up, jump up, hit the floor and go. That was our life for years.

When I arrived in Nova Scotia, I spent a few years just cooking for my friends while working part-time at a daycare. My friends offered to pay me for the cooking, but that is not how we do things in Sri Lanka. One day, one of my friends took me to the Lunenburg Farmers' Market. I remember walking in and my heart was beating so fast I thought ‘Wow, I just love this place.’ I felt a sense of community there that I was used to from

suitcases. Doing aid work, we didn’t make a salary. We arrived here at 42 years old and we had to start right at the bottom. So $35 for me was a lot at the time.

I then found out that I had to have certain equipment that I couldn’t afford, so I got a job at a restaurant in Bridgewater, where we live. I went in and said “I’m a mom and I can cook, can you hire me?” They invited me for a working interview and gave me a big bucket of chicken to cut. I was cutting away and I was very nervous and halfway through my shift, the chef said “Suni you’ve got good knife skills – we’d like to hire you.”

With that job, I was able to raise the money to get the equipment I needed to get started at the farmers' market. I

Spring 2022 11

From her small kitchen, Ferreira serves up everything from Pulled Pork Curries, Pillawoos Fried Chicken, Cilantro Chicken Curry, and Creamy Butter Chicken to Dahl, Pappadams, Fragrant Yellow Rice, Creamy Potato Carrot Curry and Cucumber Raita to Vanilla Cream Eclairs, Chocolate Cake, Coconut Carrot Cake and more.

So one day, as I was coming in to Lunenburg, I saw this little place for rent. I thought it would be too expensive, but I called. The lady who answered asked if I was Suni from the market. She said “I love your food!” and offered to talk to her boss about the space. He wasn’t too sure about it being a restaurant – it had been a consignment store and a pet store. But he said “we’ll give you a chance, Suni".

At that point, I said to myself, “You better just jump in and see what happens.”

From the very first day, I had a crowd come in and I’ve never worried about finances from that point. I can pay my bills, my rent and everything.

EM: Where did you learn how to cook?

SF: We had been doing aid work in the mountains for eight years when the 2004 tsunami hit Sri Lanka. When that happened, the terrorists laid down their arms and the government laid

little bits here and there, we decided to take a whole village and build it up again. You see, when the tsunami hit all of the fishing boats were washed out into the ocean and their nets and everything. For the fishermen, that was their livelihood and they lost everything. So we helped rebuild homes; we helped buy boats and nets.

I spent a lot of time with the ladies and the children. Because I was Canadian, there were areas that were viewed as too risky for me to travel into. If anything were to happen to me, it could become an international incident. So I stayed in the village with the ladies and the children. To build a bridge, I said, “Take me to your kitchen." They taught me how to cook and they were patient with me. They would laugh with me when I did something wrong and it was just such a wonderful time. I went there to help them but it was the reverse – they helped me. They taught me so much about how to cook, and about hospitality in Sri Lankan culture. They had very little but they would give you everything. This has been a very big lesson for me.

12 edible MARITIMES

Suni posts her menu on her facebook page. She serves up her curries and desserts until she's run out, which is always.

just depending on which ingredient you add more or less of. Cooking with spices is like making a tapestry, it’s like art. Every time I have my pot in front of me – now I do have a lot of my recipes – but in creating a dish it is like an art. Some spices you add for flavour and some you add for colour – it’s all about the balance.

EM: Do you have a favourite thing to cook?

SF: Honestly, I love baking cakes. I always say if I could do it all over again I would have gone to baking school. I just love it. So that’s why you’ll get my curries but you also get my cakes. A little historical fact – Sri Lanka was colonized by the British, the Dutch, and the Portuguese so embedded in the culture are the cakes and the scones. Baking is embedded in the culture and four o’clock is tea time or the unions go on strike.

EM: Would you say cooking has brought you community?

SF: Yes, and my community has brought me cooking. When my husband and l left Sri Lanka we struggled. There were so many people we had to leave and we could no longer help them. There are people we’ll never see again. Some are gone because of the war. It’s very hard to find the words. It was very sad.

If you asked me then if I would be doing what I’m doing now I wouldn’t have believed you. I’ve traveled many places in the world but being with the community in Lunenburg – they’ve given me such love and acceptance and that has been part of my healing. To move forward in life and to know I did the best I could. They’ve given me that push to move forward. They come in and they are so excited. Some of them dance in and then they talk to each other on their way out about how excited they are. This makes me so happy.

I am only what I am because of the people that are around me. When you’re loved it’s easy to give back love. When I arrived here twelve years ago, I was like a tiny little broken seed or plant and you give what you have and other people water it and nurture it and it grows into something beautiful. I want to be that for other people in my life. It worked for me and I am really grateful for that. Ferreira's chocolate

Suni’s Sri Lankan curry-making guide

by Suni Ferreira

The best way to make curry, is to create it. Simply defined, curry is a "spiced sauce", but its depth and complexity lie in how you combine your ingredients. A Thai, Indian, Malaysian or Sri Lankan curry will have its own unique flavour, and each region or household its own lovingly guarded 'curry code'. It has taken me over 25 years to perfect my curry. The following is my guide. I hope you find this useful for making your own delicious curries at home.

Step 1 – the spices:

The most important flavour-building step – and the ingredients are ultimately up to you. Those with stars (*) are required for an authentic Sri Lankan curry. Add small quantities first and adjust as you develop your recipes. In a skillet, briefly on medium-high heat, add a couple of tablespoons of canola, vegetable or coconut oil (do not use olive oil) and add your spices in the order listed below.

Cinnamon sticks*

Brown mustard seeds

Fenugreek seeds

Chilli flakes

Onions and garlic*

Fresh ginger

Lemongrass

Curry leaves (or padang leaves)*

Ground black pepper*

Chilli powder*

Turmeric powder*

Roasted curry leaf powder*

Reduce heat to medium-low and sauté the mixture to release the flavours; add your choice of chicken, beef, pork or lamb. Add salt to taste and toss.

Step 2 – the sour:

In addition to enhancing flavour, this step helps to tenderize the poultry or meat in your curry. Add a dash of pure white vinegar* or tamarind paste. Chopped fresh tomatoes can be added at this stage, to your taste. Cover and simmer on low heat until the protein is fully cooked. I prefer not to add water at this step as I find meats and chicken release enough liquid of their own. A quick toss or two while it simmers is all that is needed.

Step 3 – the sweet:

Nothing is complete without the sweet. Add coconut milk* (or coconut cream for a thicker curry). Turn up the heat to medium-high and cook until your curry has reached its required consistency. For garnishes I like to use freshly chopped cilantro and/or mint leaves (especially for my beef, chicken and favourite lamb curries). Developing your own curry takes time as you experiment with different amounts of each spice, of the sour and the sweet. Enjoy the process!

Spring 2022 13

cake (photo by Suni Ferreira)

OCTOBER 1–2, 2022 | DENVER, CO

Join thought leaders, writers, innovators, and industry experts in Denver as we celebrate 20 years of telling the story of local food and explore the ideas, challenges and changes that will shape our food communities in the next decade and beyond. For more information, visit edibleinstitute.com

Edible is pleased to announce Dr. Temple Grandin as our keynote speaker for this year’s Institute.

Dr. Grandin is a scientist whose ground-breaking work in animal behavior has helped shape standards of excellence for the humane treatment of animals around the world.

14 edible

MARITIMES

It's simple... it's hard work

Making a life as bean-to-bar chocolate-makers in a small town by the sea

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

It's early morning on Water Street in Saint Andrews, N.B.. The sky hints at sunrise as streetlamps drip their light down into the puddles from last night's rain. Most shop windows are still dark.

Down the street, warm light pours out of and all around the McGuire Chocolate Company. Through the windows, movement suggests the work of the day is well under way. While many of us are still in bed or just pulling on a sweater to take the dog outside, bread bakers and chocolate-makers are already hard at it. The work that goes into all of the food we eat starts early. As bean-to-bar chocolate-makers Mark and Victoria McGuire point out, it never really stops.

Victoria swings open the shop door and the aromas of chocolate- and bread-making float out into the rain-soaked street. She cranks open the awning in anticipation of the day’s sunshine and the sky brightens a little.

Inside, past the quiet hum of the espresso machine and the shelves of beautifully wrapped chocolate, Mark is crushing pecans for one of today’s ice cream flavours while chef-intraining, Ella, arranges loaves of bread in the oven before turning her attention to waffle cones.

“Our focus on chocolate, bread, and ice cream,” Mark explains, “comes out of an alignment with one of our core values about food – simplicity. Chocolate is simple. It’s the process behind it that makes it special. Bread is the same – flour, water, yeast, salt.”

While the ingredients may be simple, the elements that make premium bean-to-bar chocolate highlight the complexity and the hard work behind it. Ask Mark what goes into making McGuire chocolate so good and he begins with the bean. “It starts with the origin of the cacao,” Mark states. “Where the beans come from matters.”

Kakaw, as the Maya refer to it, originated in South America and was first cultivated more than 5000 years ago. Later introduced to Central America and Mexico, it is now grown around the world. Time spent in Mexico, where cacao is ubiquitous, sparked Mark’s interest in chocolate-making. From that initial spark, he and Victoria have grown their bean-to-bar chocolatemaking into an award-winning company.

Bean-to-bar chocolate-makers produce chocolate directly from the cacao bean, highlighting the origin of the bean. Many makers, the McGuires included, engage directly with cacao farmers or with distributors who trade fairly with farmers. “The

Previous page: Victoria and Mark McGuire in front of their shop

Top: Victoria prepping for the early morning rush

Middle: Homemade waffle cones cooling

Bottom: Mark crushes pecans for one of today's flavours

Right: A view down Water Street

Page 18: Chocolate in a melanger (top) and loaves of bread just out of the oven (bottom)

16 edible MARITIMES

craft bean-to-bar chocolate industry is just over 20 years old,” Mark points out. “It’s the relationships between farmers and distributors that have made it possible.”

Most of the world’s cacao – over 90 per cent of it – is grown on small family farms (often fewer than seven acres) in some of the most remote places, underlining the importance of the origin of the beans and relationships with farmers. Not only do trade relationships support farmers, they help bean-to-bar chocolate makers source the quality cacao they need for their craft. The chocolate in McGuire’s signature ice cream, hot chocolate and house brownies is made with beans from one particular farm in Costa Rica. Mark and Victoria got to know these farmers while visiting the country. “It’s nice when you can buy directly from farmers,” Mark says. “But this isn’t common and it’s not always easy.”

Fermenting flavour… and plans

When Mark bought his first bag of beans in Oaxaca, Mexico, he befriended a chocolate-maker in a market, who offered some instruction and loaned him a grinder. “It was, essentially, a meat-grinder,” Mark remembers. “I ground the beans just

as he’d told me to do, and oh I got chocolate. But it wasn’t satisfying,” he says with a grimace, “I needed to learn more.” Mark brought his sack of cacao back to Calgary, packed up his car, and spent the summer travelling through British Columbia and Washington State. That sack of cacao? It was right there with him, in the passenger seat. Living on the road, he snacked on the raw cacao, made raw cacao brownies and puzzled over chocolate-making.

He returned to Calgary full of questions, looking for chocolatemakers. He found none, but he did find Bernard Callebaut, a fourth-generation chocolatier. Mark convinced Callebaut to hire him and, for the next few months, learned invaluable lessons about the chocolate business, quality and flavour. He was ready to put his own plan into motion.

“Bean-to-bar chocolate was very grassroots at the time, but there were a couple of suppliers selling small quantities of beans from different places around the world,” Mark explains. “I chose 10 origins and decided I’d prepare them all the same way. It took me months, but that’s what I did and they were all incredibly different. I thought ‘This is cool, this is what I want to do.’”

Spring 2022 17

18 edible MARITIMES

Just like any good plan, cacao needs time to ferment. Controlled fermentation encourages micro-organisms to break down the pulp around the bean and shape its flavour. To be effective, fermentation must happen just after the pods are harvested. When the McGuires source cacao for their chocolate, they consider fermentation crucial. Their Costa Rican supplier ferments on his farm. Their Tanzanian supplier is a distributor who ferments on site, collecting beans from individual farmers and paying them a living wage. While highlighting the importance of fair-trade relationships, fermentation also makes bean-to-bar chocolate special.

Roasting beans and taking notes

Slow-roasting cacao brings out the flavours that fermentation has helped establish. Walk into the McGuire Chocolate Company, when the roasting has just begun, and you may not know roasting is underway. Later on in the roast, as Mark explains, "the beans burst forth brownie aromas." As the roasting continues, you might catch earthy tones, nuttier notes, or the subtle aromas of stone fruits.

“Assessing the taste profiles of the beans is one of the best parts of the process,” Victoria says. “We take a lot of notes before, during, and after the roast.” Mark and Victoria pay close attention to every detail, in everything they do. This may be one of the secrets to their success in business and in life. The care and hard work they put into every step is evident as soon as you walk into their café, and it comes through in every bar, every loaf of bread and each scoop of ice cream. When Mark started out, he was making chocolate at night while working IT contracts by day. “It was time- consuming,” he explains, “I was basically living in a bare apartment, just my chocolate equipment and kitchen.”

In the midst of all of this, Mark met Victoria online. Victoria had recently moved to Calgary from Ontario, and taken on a new job. “She made me laugh,” Mark recalls with a smile. The stars soon aligned and they planned to meet in-person. That night, having recently acquired a television to watch the coinciding Summer Olympics and the Blue Jays playoff season, and up to his elbows in chocolate-making, Mark nearly lost track of time. But he wasn’t going to miss this date. He showed up covered in chocolate with one of his single-origin chocolate bars in hand. “I wasn’t a ‘chocolate person’ when we met,” Victoria explains, “but Mark’s passion for chocolate was infectious.”

on the side. Their cat, Hank, the silent partner in the business, became the face of their popular Hank series and they began looking for ways to grow their business. “I never considered chocolate a hobby,” Mark points out. “From the beginning, this was a business and we wanted to scale,” he explains. “We were looking across the country for somewhere we could afford to make chocolate and have a good quality of life.”

“We were thinking maybe a bed and breakfast,” Victoria adds. “Chocolate-making is a 24/7 job and this would allow us to work where we live.” As they searched for a property, Victoria was experimenting with bread-making and Mark was exploring ice cream, to complement their chocolate- making. It wasn’t until a property on the West Coast fell through and a small shop space on the East Coast became available that their plans finally came together. The East Coast wouldn’t be new for Mark – he was born in Saint John and grew up in Nova Scotia – but Saint Andrews was new for both of them.

Just months before the pandemic hit, Mark and Victoria welcomed their first son into the world and moved across the country. They transformed their empty shop space on Water Street into a beautiful small batch bean-to-bar chocolatemaking factory, ice creamery, and café, and they moved in upstairs. Over the past two years they have welcomed their second son into the world -- all the while establishing their café in the heart of town, and their chocolate company as the largest bean-to-bar producer in the Maritimes.

Slow and steady

Chocolate-making at this scale does require efficiencies. It was during the initial process of twisting and separating shells in his apartment kitchen that Mark realized the importance of having the right equipment. Take winnowing for example – the process of removing the shells from the cacao nibs… “I was spending hours separating shells,” Mark explains, “when I read this blog where this guy took his tray of cracked cacao outside and let the wind blow the shells away. I thought ‘No way!’” he laughs. “I have to control the process. I need efficiency.”

Victoria joined Mark and together they started selling their small batch chocolate in Calgary. People liked it and for the first few years, they continued with their day jobs, producing chocolate

The McGuires invested in equipment that provides those needed efficiencies, but this doesn’t always mean things are done quickly. When it comes to grinding beans and finishing their chocolate, they are happy to take their time. They run their stone melangers (grinders) for up to seven days, while they make adjustments, calibrate temperatures, and take notes. Mark explains, “this is when the flavour really comes together – from the roast, the fermentation, the origin. If you walk in at the beginning, it’s intense and then it becomes smoother. You can grind more efficiently and do it in a day and get a smooth

Spring 2022 19

consistency, but the flavours will be intense and all over the place.” So they take their time to do it right. In addition to single origin bars, the McGuires create limited release varieties sometimes with unexpected ingredients – think bourbon, peanut butter, banana or sourdough bread.

Living simply, living well

As Mark brews a cup of coffee for the first customer of the day, they chat about today’s bread – a classic sourdough with a honey golden crust. Some of the loaves are already spoken for, by folks who called the day before. It’s no secret that McGuire bread is some of the best for miles around. The McGuire Chocolate Company has quickly become a vital part of the community just as the community has become an important part of the McGuires’ lives.

When Mark and Victoria made the move to Saint Andrews they did so with simplicity in mind. They wanted to live where they work. Hank joined them, of course, and can often be spotted wandering around town. (It is rumoured he comes from a long line of seafaring cats.) They invited Mark’s mom to join them. She helps with the business and in caring for her two grandsons. Victoria’s parents soon followed, drawn by the appeal of this place by the sea.

Mark and Victoria have chosen a town that has a simplicity that is characteristic of many communities in the Maritimes, where everything you need is close at hand, and if it’s not, you'll find those with the creativity and ingenuity to make it happen. The McGuires depend on and contribute to the community of local producers and artisans here in town and in the Maritimes, just as they rely on a supply chain that supports small-scale cacao farms around the world. They serve coffee from local roasteries in mugs made by local potters and they include regional ingredients such as sea salt and lavender in their recipes. Saint Andrews is also home to the NBCC’s renowned culinary and hospitality programs. Emma, their chef-in-training, is a current student of the culinary program and they hire other college students in part-time positions, providing valuable hands-on learning experience.

The sidewalk outside is bustling. Someone comes in for a loaf of bread, a latte, and a peanut butter square. Another customer chooses a bar of chocolate while another reads aloud from today’s list of ice cream flavours: “Irish Campfire, Strawberry Cheesecake, Orange Coconut.”

Victoria emerges from the kitchen with a large tray of freshly pressed chocolate ready to be wrapped. “Unwrapped, our bars all look identical,” Mark explains, “You can have 15 different origins with different fermentations, origins, roasts but they all look the same. We didn’t want to dress the chocolate up - it should speak for itself.” To communicate how special the chocolate is, they will wrap each bar with beautifully designed packaging featuring art by Canadian artists.

The McGuires break off a few pieces of chocolate, stamped with their logo, for us to taste. “One of the ways to taste chocolate is to let it melt in your mouth. Let the flavours hit you in waves,” they suggest.

In smooth peaks and valleys.

Simply delicious.

20 edible MARITIMES

Above: First coffees of the day and a fresh batch in the Hank series of chocolate.

Right: Early morning at McGuire's and a limited release bar.

Chocolate Syrup by The

McGuires

Ingredients:

2/3 cup (180g) cane sugar

2/3 cup (150g) water

¾ cup (120g) single origin dark chocolate*

1 1/2 tablespoons salted butter

Make:

Bring sugar and water to a gentle boil. Remove from heat and add butter. When water cools to below 60 degrees Celsius add chocolate and whisk vigorously until smooth.

Suggested Use Drizzle over ice cream.

Storage

Store in a glass jar in the fridge. Reheat or enjoy cold or room temperature.

*We use a 67% Costa Rican chocolate with a cocoa-forward and nutty flavour profile.

Spring 2022 21

St Andrews, NB

Purveyors of organic local whole foods

Purveyors of organic local whole foods

h

Prepared take-away foods made daily

Prepared take-away foods made daily

Spices, grains and supplements

Spices, grains and supplements ,

Fresh seafood and charcuterie

Fresh seafood and charcuterie

Locally grown produce and owers

Locally grown produce and owers

Baked goods and sweet treats

Baked goods and sweet treats

Teas, co ee and more

Teas, co ee and more

Charcuteries

Canard, Veau

LA FERME LA FERME du DDIAMANT IAMANT The Spice Box St Andrews 579 Route 945, St-André-Leblanc, NB, 506 532-5579 Green Pig Market Salisbury Cielo Glamping Haut Shippagan NB Co_Pain bakery Moncton NB Marche au Corner Cap-Pele NB

Farmers Market Fredericton Farmers Market BEVERAGE CO. www.rabbittownbev.com

salmon

Route 172

NB 506-755-1203 274 Route 175, Pennfield, NB 506-755-2992

premier

batch hot sauce brand

Find these brands, and more, at the Spice Box:

Traditionnelles Françaises

de lait, Saucisson, Jambon, Pâté et Galantine

Dieppe

Premium smoked

420

Saint George,

Canada's

small

spicyboys.ca

,

,

, ,

, h

,

,

,

,

171 Water Street 3 506-529-8520 spiceboxcomestibles

h h

Salt sorcery on the South Shore

OK Sea Salt distills the essence of the place with its small-scale, sustainable solar-evaporation saltworks.

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

Whips of wind and waves of salt water run circles around islands all along the coast of Nova Scotia, as if casting rings of protection around their inhabitants or invoking a little magic with the tides. Onya Hogan-Finlay and Kim Kelly draw on this salty magic as they build their small-scale solar evaporation saltworks in the LaHave Islands.

Hogan-Finlay and Kelly are no strangers to magic, but salt harvesting was not on their radar when they set course for eastern shores. Moving from Los Angeles back to the East Coast was based on a gut feeling. Hogan-Finlay had grown up spending summers with family along the Miramichi in New Brunswick and Kelly was born in Massachusetts. Despite their eastern roots, choosing to build a life here meant taking a giant leap.

Hogan-Finlay and Kelly had been living and working in Los Angeles. Their paths first crossed years before their L.A. story was written. As a Concordia University grad, Hogan-Finlay was one of the founding members and curators of projet Mobilivre-Bookmobile project. The Bookmobile project was a mobile exhibit that disseminated art publications across Canada and the United States in a vintage airstream trailer. The Bookmobile stopped at schools, colleges, festivals and galleries

to give students and community members the opportunity to explore artists’ publications and zines. Despite never having met in person, it just so happened Kelly’s zine was featured in the Bookmobile’s collection that Hogan-Finlay helped curate. Their paths crossed again in California when the two artists met at a show and fell in love.

As an interdisciplinary artist, the vibrant arts community of L.A. provided Hogan-Finlay the opportunity to work as a teaching artist, facilitating hands-on learning with students of all ages in community arts settings and at UCLA. For Kelly, California was a place to balance her academic training in Landscape Horticulture at Oakland’s Merritt College with her creative background and passion for wild food foraging. She owned and operated Woodward Gardens – a landscape design company that specialized in native Californian plants and drought-tolerant lawn conversion. They were both part of expansive creative and urban queer communities, but they found themselves in search of a place where they could work with the natural world more directly. They had a vision of themselves as farmers and found themselves looking eastward. Finding land would not be enough, they wanted community as well. “We flew out for an informal research trip in 2018 to check out some towns in Atlantic Canada,” explains Hogan-

24 edible MARITIMES

Kim Kelly and Onya Hogan-Finlay with a fresh batch of their sea salt ready to pack up for lucky customers.

Finlay, “On that trip we made a point to connect with folks in the queer community and artists, too. We were both drawn to Nova Scotia and landed in Halifax in 2019.”

They rented an apartment in the city and continued their search for their new home. When a sweet house near the water in Lunenburg County became available they couldn’t pass it up. This perfect house sat on a rock with plenty of sun exposure, tons of wind and the salty ocean just metres away, but it would take further research to determine how to thrive in this setting.

“When we first arrived in the province, salt-making was not on the list,” Kelly explains, “We knew we wanted to support ourselves in a way that harmonized with nature rather than harm it.”

“It was clear that farming veggies on an acre of rock was not in the cards for us and that we would need to work with the landscape,” Hogan-Finlay adds, “so Kim did some research and started experimenting with the salt water that surrounds. One day we filled a cauldron with sea water, boiled it down and marveled at the delicate salt crystals that formed.”

They soon set out on a path to be sea salt farmers with the goal

of building a small carbon footprint production facility.

Around the world, and for millennia, humans have sustainably harvested salt from the sea – to season their food, trade as currency, cast for protection and mark special occasions. On the West Coast of Scotland, the Blackthorn Scottish Sea Salt company draws seawater up into tall towers. From there, the seawater slowly trickles down through piles of thorns while the wind helps evaporate the water, leaving a salty brine. The Kona Sea Salt company in Hawaii pumps deep sea water into the long tunnels of its enclosed solar evaporation system, using the sun to dry its salt all year long. On the West Coast’s Salt Spring Island, the Salt Spring Sea Salt company focuses on fleur de sel – the pyramid-shaped crystals that rise to the top during evaporation – recreating the conditions for these crystals and producing a fleur de sel that rivals the best in France. Here on the East Coast, there are several sea salt farmers who use sustainable methods, some of whom rely largely on solar evaporation.

In the Spring of 2021, Kelly and Hogan-Finlay launched their saltworks in their backyard, where they are prototyping sustainable solar evaporation techniques. OK Sea Salt’s smallscale production process relies on the sun, the sea, the moon,

Spring 2022 25

Above left: Prepping for a sea salt tasting in the sun. Above right: OK Sea Salt's solar ovens.

and the wind – as well as the hard work, creative vision and enthusiasm the couple put into its new company.

“We only collect water during high tide, at the full moon,” Kelly explains, “when there is the greatest water exchange. This kind of imparts a mystical quality. We really tune in to the moon and tides here.” At the full moon, the pair collects buckets of salt water to fill pans in solar ovens. These solar ovens are similar to the cold-frames used by gardeners. OK Sea Salt’s solar ovens serve a similar purpose – housing trays of salt water in frames of concentrated sunshine. In these ovens, evaporation typically takes four weeks. In the colder months, evaporation is slow and the water sometimes freezes. Hogan-Finlay suggests that this freezing can be helpful, “sort of like when maple sap runs and then freezes – through the process of brine rejection, the pure water freezes on the top and the saltier water settles at the bottom of the bucket.”

“Freezing salt water can help make up for the faster evaporation that you get in the warmer summer months,” Kelly adds, “and it’s a fun way to be outside in the winter.”

To impart a range of flavours to their salts, they add foraged plants such as lovage, spruce tips and wild cranberry in salt blends and place sweet fern leaves within the cold frames to naturally deter pests from the salt pans. Once they’ve harvested the culinary grade salt from their solar oven pans, HoganFinlay and Kelly collect the crystallized bittern – a byproduct of the process. This bittern solution is higher in magnesium

and not a recommended finishing salt. Hogan-Finlay and Kelly then infuse the crystallized bittern with wild roses and bayberry leaf, along with magical properties, to create their limited edition Ritual Salt, which has become a favourite for many of their customers and one that Kelly and Hogan-Finlay use in their own witchy practice. This kind of creativity and product innovation get these two salt farmers excited about the possibilities of sustainable sea salt production.

For Kelly and Hogan-Finlay, sustainability is not simply about living in balance with their environment, it is about community. They are members of the nearby LaHave Islands Marine Museum and speak with gratitude about their neighbours –their friend down the road who cooks for all the seniors on the island, the queer couple that does sea salt recipe-testing for them, the fisherman who flies a rainbow flag, seemingly in solidarity, the rural artists, farmers and other sea salt harvesters in the region and the purveyors of goods along the South Shore, including Ploughman’s Lunch and The Seaberry, that are just as strong on social advocacy as they are on providing quality goods. These two shops are among many in the region that now carry OK Sea Salt and they say their customers are thrilled to have a locally produced sea sea salt option. OK Sea Salt can also be found in shops as far away as California as people seek more sustainable alternatives made in North America. In return, Hogan-Finlay and Kelly give back to their community as creators, entrepreneurs and empowered, inspired role models for other queer creatives, small business owners and farmers all along the East Coast – and everywhere for that matter.

26 edible MARITIMES

Hogan-Finlay and Kelly at work at their home/ saltworks.

Sitting on Hogan-Finlay and Kelly's deck in the bright sun, with the shore just metres away, you can’t help but feel as if you are in the middle of the ocean. And you are, just about. Their saltworks sits about one third of the way down the South Shore coast of Nova Scotia from Halifax. It’s tethered to a tombolo (a sandy isthmus of beach), along the way to other tiny islands that go by names such as Bell and Rabbit, The Squam and Hirtle. A paddle from their shore and out through Wolfe Gut will take you to Tumblin Island and Wolfe Island to spots on Cape LaHave Island where you can pull up your kayak and stop for a picnic.

It was on a bright sunny day that Kelly and Hogan-Finlay surprised us with their inaugural OK Sea Salt salt tasting. We sat around a table as bird song mingled with the ocean breeze, the swoop of a hawk from above and the sound of fishers on the dock. We sipped local brew, as they grilled homegrown peppers, sliced watermelon, apples and tomatoes, and perfect hard-boiled eggs. We chose from natural, lovage and spruce tip sea salt varieties, sprinkling one after the other on those peppers and watermelon, tomatoes and eggs. We dipped apple in honey and sprinkled salt again.

Sea salt tasting with OK Sea Salt

There really is nothing on earth that compares with the simple beauty of hand-harvested sea salt, cured with wild lovage, sprinkled on a slice of watermelon, or tomato or an apple dipped in honey.

Hogan-Finlay describes sea salt as “the distilled essence of a place," and it truly is.

Spring 2022 27

Soft pretzels with OK Sea Salt

by Kate Walchuk, Sea salt recipe creator and tester

by Kate Walchuk, Sea salt recipe creator and tester

A soft chewy pretzel with a toasty crisp crust showcases the salty essence of the sea just perfectly.

Step 1

Mix:

1 1/2 cups warm water

1 tablespoon table salt

1 tablespoon sugar

Then add

1 packet active dry yeast

Let rest until yeast starts to foam (5 min)

Step 2

Add:

4 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

2 tablespoons olive oil (or your oil of choice)

Mix thoroughly until a dough forms. Remove dough for a moment, drizzle about 1 tablespoon more oil into the bowl to prevent sticking. Cover bowl with a wet tea towel or plastic wrap and let rise in warm place for 1 hour.

Step 3

Preheat oven to 425 F

Cut dough into 12 pieces (cut dough in half over and over until you get 12).

Roll into thin ropes (approximately 20-24 inches long) and form pretzel shapes by first laying it in a horseshoe shape. Cross the ends over each other once and then again. Take those ends and flip up to form

a pretzel shape pressing gently to connect. (There are lots of helpful videos online demonstrating this technique.)

Step 4

Add 1/3 cup baking soda to a large pot of water. Bring to a boil on the stovetop. Gently lift each pretzel into the water and let it boil 30 seconds per side. I can fit three pretzels into the pot at a time. This is the step that results in a chewy pretzel with a nice bit of browning on the outside.

Step 5

Transfer pretzels to a baking sheet. Brush with an egg wash. I just use the yolk because it gives them a nice colour.

Sprinkle with OK Sea Salt and bake for 8-12 minutes until browned.

Enjoy!

Ploughman's Lunch in West Dublin, N.S.

Photo: Steadii Creative

Ploughman's Lunch in West Dublin, N.S.

Photo: Steadii Creative

In the north west corner of Malpeque Bay, PEI, sits a horseshoeshaped island called Lennox Island, home to the Lennox Island Mi’kmaq First Nation. Their ancestors have lived in this region for 10,000 years.

Top left and right: rows of greens growing sheltered in the greenhouse from the late winter snow outside.

Bottom left, Mark Ellands waters tomato plants.

Words: Sara Snow

Photos: Hannah Arsenault

30 edible MARITIMES

Growing resilience

The Lennox Island Mi'kmaq First Nation Greenhouse and Gardens

Building a sustainable community-based food system begins with planting seeds, but takes so much more. In 2019, Ulnooweg Education Centre's Digital Mi'kmaq program launched its Community Garden and Food Security Project across five partner communities. Through this initiative, Lennox Island Mi'kmaq First Nation has established the Lennox Island Greenhouse and Gardens. Two years into the project, Mark Ellands, Greenhouse Manager, and Dawn Matheson, Ulnooweg’s Food Security Project Co-ordinator, reflect on the process of establishing a community garden initiative and what it will take to grow a successful community food program.

"One of the most important things about this project," Ellands explains, "is that everyone has access to sustainable healthy food. People don't have to drive 45 minutes into town, they can come here." In the large greenhouse and in the adjacent garden of raised beds, Ellands and his team grow tomatoes, greens of all sorts including kale and bok choy, beans, cucumbers and more. Once plants are ready to harvest, Ellands focuses on getting community members to consider the greenhouse as their first stop for food. "People choose food options they're familiar with. Or they'll wait until they're going into town to get other supplies to get their cucumbers or tomatoes then." To be successful, Elland says, buy-in from the community is important.

“Now that the greenhouses and gardens are in across our participating communities,” Matheson explains, “Sustaining it will depend on community participation and all of our communities are working on that, focusing on communication and education.”

Ellands shares garden news on the community Facebook page. Community members can visit the greenhouse to collect or harvest their own vegetables, or purchase them at the community shop. Through the summer of 2021, the garden team hosted groups of Elders as well as the Lennox Island Youth Gardening Program. The Daycare and Summer Health Camp children planted, watered and harvested carrots, cucumbers, beans, and pumpkins. "This was the first time these kids had the opportunity to harvest their own pumpkins, to grow them from seed. They were excited about that," Elland explains.

Ulnooweg launched its Community Garden and Food Security Project to help address the increasing food insecurity across Indigenous communities. While the industrialization

and centralization of food production may have brought some efficiencies to food processes around the world, they have effectively separated people and communities from the production of that food, thereby reducing community knowledge and experience. Add to this climate change, the growing fragility of food supply chains around the world and our collective reliance on long-distance shipping, and access to quality food becomes ever more difficult. For Indigenous communities around the world, these issues only exacerbate the deleterious ways in which colonization has resulted in the near loss of traditional food access and knowledge.

Food security is widely recognized as dependent on four factors: availability, access, utilization, and stability. While Lennox Island has a sustainable commercial and traditional fishery, the greenhouse and gardens project adds a needed layer of food availability and access for the residents. Utilization, as both Ellands and Matheson point out, is the hurdle. "It often comes down to knowing what to do with whatever it is you're growing,” Matheson explains. "You might have a greenhouse full of amazing kale, but if no one knows what to do with kale, it’s not going anywhere."

"You can hand someone some bok choy and green onions," Ellands adds, "but these are not necessarily helpful if you don't know what to do with them."

Ellands is working with community leaders to find ways to increase the usability and the convenience of the greenhouse and garden harvests. One strategy is to provide recipes along with the greenhouse foods in the community shop. Another is to continue growing their education programs. "To be successful," Ellands suggests, "we need to be well-integrated in the community."

When asked what she feels is most important about Ulnooweg's Community Garden and Food Security Project, Matheson explains: "It's all about building resilience. Food is the centre of any community and the more we bring food back to our communities the more resilient we will be."

As the greenhouse manager, Ellands is excited to be growing food in his community and to be part of this growing initiative as it transforms.

in the garden Spring 2022 31

Lennox Island inspired bok choy & salmon with wild rice

A simple way to bring together locally-grown and wild harvested ingredients

Ingredients

1 cup wild rice (uncooked)

4 cups water

2 salmon fillets

Olive oil

1 or 2 heads of bok choy (depending on size)

Salt and ground pepper to taste

1 lemon, optional

Red chilli flakes

4 ounces of white wine

Wild rice

Rinse 1 cup of rice in cold water. In a medium-sized sauce pan, add to pot with 4 cups of water. Bring to a boil and reduce heat. Place cover on pot and gently boil for 30 minutes. Turn off the heat and let stand in pot with cover on for another 30 minutes. Drain any excess water.

Salmon

When rice is nearly ready turn barbecue on high. Drizzle olive on the salmon fillets and rub. Sprinkle with salt and pepper. Slice two thick lemon slices. When barbecue is ready place salmon (skin-side down) on the grill and place lemon slices on the grill as well.

After 5 minutes, turn lemon slices over.

After 10 minutes gently turn salmon over and grill the top for 2 minutes.

Remove salmon and lemon slices and let them sit while you prepare the bok choy.

Bok choy

Rinse bok choy in cold water and pat dry with a clean tea towel. Chop ends off the heads of bok choy so its sections fall away easily.

Heat frying pan (cast iron skillet works very nicely) and add a tablespoon of olive oil. On medium heat add the cooked wild rice. Add a 4 ounce splash of white wine and place the bok choy on top of the rice. Add chilli flakes and a pinch of sea salt and cover to steam. After 4 minutes remove pan from heat.

Serve rice and bok choy topped with salmon and lemon. Enjoy!

Recipe and photos: Dave Snow

32 edible MARITIMES

Spring 2022 33 wabanakitreespirit.com wabanakitreespirit@gmail.com 506-461-6806 Inspired strategies for enduring brands www.steadiicreative.ca OCTOBER 24-30, 2022 WOLFVILLE, NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA Get your fill of films, dinners, culinary events and workshops Subscribe ediblemaritimes.ca

34 edible Advertise with us ediblemaritimes.ca Farm

1707 Grafton St Halifax (902) 444-3844 305-40 Alderney Dr Dartmouth (902) 466-3100 9

to Table

Gillis Mussels

on the shore

A conversation with Shane Gillis about the perfect scale for a quality of life.

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

Oyster and mussel growers are fastidious. Shane Gillis and his crew sort through their oysters one by one, assessing size, cleaning them and taking them back out. "It takes a few hours to sort and then we put them back out in the water. They always get put back out unless we’re selling that day," says Jason Kennedy.

In these images, Shane Gillis and his crew (Jason Kennedy, Logan Hickey and Kelsey Kennedy) have just brought in some of their oyster crop for sorting and cleaning. This is a process that happens many times over an oyster's life, encouraging its growth and quality.

"In this round, we’re washing and sorting them. In the next round, we make sure none of them go out as doubles," Gillis explains. "Oysters like to grow in size columns. The little ones won’t feed as well if they’re in with big ones, so we sort them all by size. If we put the little ones with each other they’ll grow better. These bigger ones are about three years old.”

Shane Gillis didn't grow up in a fishing family. Many in his family, he points out with a laugh, didn't even like to be on the water. There was a fear of it. What drew Gillis to mussel- and oyster-farming was a combination of timing and a passion for the hard work and rewards of a farming life.

Back in the day, Gillis explains, "Everybody in P.E.I. would go to Alberta to work, so I did that for awhile. Alberta and then Venezuela with the same company. I did that for two years, but decided it wasn't for me." Gillis returned at the age of 19 and got a job on mussel farm.

Gillis grew up in a farming family, raising cattle, chickens, pigs, growing on and working the land. He describes a similarity between working the land and shellfish farming. "When I got into mussels, it took me back to farming. Taking something and watching it grow then to see it on the table – this is what I like. And the lifestyle is a lot like farming. You wake up every morning and check your crops. There are storms that will throw you backwards, then there will be conditions that will be great for your crops."

Gillis liked mussel farming. "The more work you put into it, the more you get out of it and this always appealed to me. I just wanted to work more than anything." So he did and when his friend decided to get out of the business, Gillis bought him out. "At the time," he explains, "it

Gillis Mussels Done Right

When Shane Gillis serves you his mussels, you'll become a mussel lover even if you weren't.

4 stalks celery

1 large onion

4 cloves of garlic

3 carrots

2 pounds of mussels (fresh with a little ocean water)

White wine to taste

Splash of Montreal Steak Spice BBQ sauce

Salt to taste

The method:

Finely dice celery, onion, garlic and carrots. In a large heavy-bottomed pot add water, vegetables and mussels. Bring to a boil on medium-high heat. Add white wine, bbq sauce and salt.

Cover and let steam for 5 minutes until the mussels open.

wasn't hard to get a lease, there were so many acreages then and the only way now is to buy someone out. Back then, people wanted to get out of mussels."

Gillis now raises mussels and oysters most of the year, taking winter months to run his snow plow business. He keeps his business small-scale, enjoying the quality of life he and his family have. "I am one of the smaller growers. I usually run two boats with nine guys. There used to be about 200 growers my size, but over the last 10 or 15 years a lot of guys have been getting out of it. The plants buy them out. And there are a few large independent growers."

Gillis and his wife, Crystal, have two sons in their 20s who have chosen to stay on the island, not drawn away as Gillis's generation was. "Out West used to be the place where you could log a ton of hours, put your head down, make some money. But it's not quite the same. And there are a lot of opportunities on the island. People are crying out for workers now." Gillis's sons haven't joined his crew, choosing work in construction and carpentry.

Small-scale has enabled Gillis and his team to ride the wave of the pandemic fairly well. "Sales did go down at the beginning, which meant we had a lot of oysters here with nowhere to go. As business comes back we’re seeing more demand. It will take a bit of time to catch up that’s for sure, but we will."

Serve mussels by scooping the shells and some broth into bowls. The finely-diced vegetables will fill the shells so that each one is a shell-full of goodness. A little of the broth in the bowl goes well with some fresh bread.

Spring 2022 37

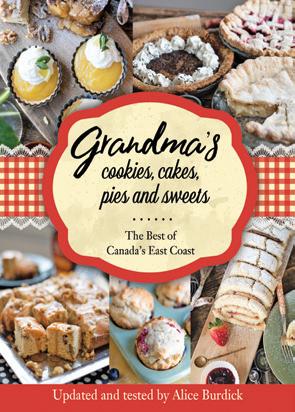

Rhubarb Cloud Pie

Alice Burdick shares her sweet take on one of spring's most delightful offerings. The following is an excerpt from her cookbook: Grandma's cookies, cakes, pies and sweets: The best of Canada's East Coast.

This is a wonderful combination of textures and flavours. The tartness and softness of local rhubarb is balanced by the sweetness and fluffiness of the meringue, with the added delight of the caramelization from the oven. This is a recipe that can come together quite quickly at the right time of year. If you keep rhubarb in your garden, you’ll find it thrives in our climate and comes back year after year with little care or attention. This is a fabulous spring recipe to make the most of the freshly sprouting stalks.

Pastry for single crust 9-inch (23-cm) pie

Filling

3 cups (750 mL) rhubarb, chopped

2 tablespoons (30 mL) all-purpose flour

1 cup (250 mL) granulated sugar

Pinch of salt

3 egg yolks

1 cup (250 mL) light cream (12% mf)

Method

Preheat oven to 375°F (190°C). Set aside a 9-inch (23-cm) pie plate.

Roll out the bottom crust on a lightly floured counter to a 12-

inch (30-cm) circle, then fit into the pie plate, crimping the edges. Place the chopped rhubarb into the pie crust. Whisk together the flour, 1 cup (250 mL) of the sugar, the salt, egg yolks and cream. Pour this mixture on top of the rhubarb.

Bake for 50 to 60 minutes, until the pie crust is browned and the filling is set. Remove from the oven.

Meringue

3 egg whites

1/4 cup (60 mL) granulated sugar

1/4 teaspoon (1 mL) cream of tartar

While the pie cools slightly, place the egg whites in a bowl. Using a handheld electric mixer, beat the whites until they form soft peaks, then add the 1/4 cup (60 mL) sugar and the cream of tartar. Continue to beat until the egg whites form stiff peaks.

Spread the meringue over the filling and return the pie to the oven and bake until the meringue is golden brown, around 10 more minutes. Serve slightly warm.

Yield: 8 servings

Spring 2022 39

Alice Burdick lives in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia where she is a poet, writer and town councillor. Her Grandma's cookies, cakes, pies and sweets: The best of Canada's East Coast is filled classic East Coast recipes and more.

a sweet finish

Explore a world of local food through the magazines and websites of Edible Communities. We’ll introduce you to the chefs, farmers, brewers, home cooks and others who inspire and sustain local flavors across the US and Canada. ediblecommunities.com Stay up to the minute on all things edible: edible brooklyn ISS UE T H E Drinks Celebrating the Abundance of Local Foods, Season Season edible Cape Cod edible COLUMBUS HAWAIIAN ISLANDS edible INLAND NORTHWEST edible 'tis the season edible manhattan Celebrating the harvest of Marin, Napa and Sonoma counties, season by season MARIN & WINE COUNTRY edible Spring 2020 the land the sea ~ the people ~ the food edible M aritimes

42 edible MARITIMES algonquinresort.com 506-529-8823 Escape. Experience. Enjoy. Located in the stunning, charming town of St. Andrews-by-the-Sea, the Algonquin is the perfect holiday retreat for families and couples and it’s an ideal location for those special celebrations. With incredible dining, a wonderful spa, an award-winning golf course, and in one of North America’s most historic towns, the Algonquin o ers an unparalleled experience.

*Literally weju’su’n translates as the ‘French man’s apple’ as the Mi’kmaq did not have apples. Thank you to Chris Googoo, Ulnooweg Indigenous Communities Foundation, for this Mi’kmaq translation of ‘edible’.

*Literally weju’su’n translates as the ‘French man’s apple’ as the Mi’kmaq did not have apples. Thank you to Chris Googoo, Ulnooweg Indigenous Communities Foundation, for this Mi’kmaq translation of ‘edible’.

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

by Kate Walchuk, Sea salt recipe creator and tester

by Kate Walchuk, Sea salt recipe creator and tester