We’re on a mission to prove that sustainably sourced, local cannabis creates thriving communities and a resilient planet.

We’re on a mission to prove that sustainably sourced, local cannabis creates thriving communities and a resilient planet.

Switzerland. Naturally.

Elevate your next wine pairing with LE GRUYÈRE® AOP , made for over 900 years from the purest cow’s milk in the Swiss Alps. Gruyère AOP’s nutty complexity sings with Chardonnay, boosts a Beaujolais, and perfects a Pinot Noir. For more information and some great recipes and pairing ideas, visit us at gruyere.com. Cheeses from Switzerland. www.cheesesfromswitzerland.com

When the temperature dropped right after Election Day, I thought it was the perfect time to test al fresco winter dining and try to figure out how we were all going to make it through the next few months.

My first foray was Friday happy hour at an outdoor patio just as the sun went down and the breeze came up from the ocean. Ouch! The metal chairs were ice cold and my denim jacket was not enough to keep me warm, even with a cozy knit scarf. A full-bodied pinot noir helped a bit, but not enough to stay out there for a second round.

The next night, I went out better prepared. Bundled in a down jacket and boots, my husband and I grabbed a sidewalk table for an early dinner. It was 51° F but the outdoor heaters worked well, the host appeared with furry blankets for our laps and we heartily enjoyed the best meal we’ve had since the pandemic began. Sure takeout is fine and helps local eateries stay in business, but there is nothing like the full restaurant experience, even on a wintry evening…outdoors.

We are lucky to live in a place with relatively mild winters, but even so, restaurants around the Monterey Bay are scrambling to make it through the upcoming months by offering comfortable winterized outdoor dining and food to go. That’s the scoop reporter Mark C. Anderson got when he talked with chefs and restaurateurs for his story Surviving Winter (page 31).

Though the pandemic has been front and center all year, we also tackle other important food topics in this issue, like what to do about all that plastic covering local farm fields, in Sarah Wood’s story Plasticulture (page 54); and we uncover a surprising secret about organic strawberries in our story Strawberry Fields Forever (page 48) by Jamie Collins and Kathryn McKenzie.

We introduce you to three entrepreneurs on the verge of making it big in the local food and drink world. Jessica Tunis urges us to make foraging for mussels an annual wintertime family tradition. Raúl Nava offers a lesson in amaro, the traditional Italian digestivo that is making something of a comeback and he shares what the pros are drinking right now. And, of course, we have lots of fun recipes to try at home.

We hope this edition of Edible Monterey Bay brings some joy to your holidays and year-end celebrations as we close the books on 2020, a truly memorable year!

One lesson of 2020 has been that we all spend way too much time online, so we invite you to unplug and sit back in a comfy chair with your beverage of choice to enjoy the luxury and pleasure of our beautifully produced print magazine.

Our sincere thanks to all our wonderful advertising partners, who have stuck with us through this very difficult year and make our work possible. To them and all our readers, we wish you a very happy and healthy new year!

EDITOR AND PUBLISHER

Deborah Luhrman deborah@ediblemontereybay.com 831.600.8281

FOUNDERS Sarah Wood and Rob Fisher

COPY EDITOR Doresa Banning

LAYOUT & DESIGN Matthew Freeman and Tina Bossy-Freeman

AD DESIGNERS Bigfish Smallpond Design Savanna Leigh • Zephyr Pfotenhauer

CONTRIBUTORS

Mark C. Anderson • Crystal Birns • Jamie

Collins • The Curated Feast • Margaux Gibbons

Diane Gsell • Coline LeConte • Michelle

Magdalena • Anina Marcus • Kathryn McKenzie

Raúl Nava • Laura Ness • Zephyr Pfotenhauer

Patrick Tregenza • Jessica Tunis • Amber Turpin Sarah Wood

ADVERTISING SALES

ads@ediblemontereybay.com • 831.600.8281 Shelby Lambert shelby@ediblemontereybay.com Kate Robbins kate@ediblemontereybay.com Aga Simpson aga@ediblemontereybay.com Penny Ellis penny@ediblemontereybay.com

DISTRIBUTION MANAGER

Mick Freeman • 831.419.2975

CONTACT US:

Edible Monterey Bay P.O. Box 487 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 ediblemontereybay.com 831.600.8281 info@ediblemontereybay.com

Edible Monterey Bay is published quarterly. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used without written permission of the publisher. Subscriptions are $28 per year at ediblemontereybay.com. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our apologies and notify us. We also welcome letters to the above address. Thank you.

Deborah Luhrman Publisher

Hollister woman puts wellness first with her extensive line of fermented foods

BY KATHRYN MCKENZIE PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRYSTAL BIRNSMary Risavi had been making her own fermented food concoctions for years and always looked for ways to make them healthier. Yet the Hollister resident didn’t think of it as more than a hobby until demand boomed. “Then I realized it was an actual business,” she says.

Under her brand name Wise Goat Organics, she’s been helping people develop healthier digestive systems—and doing it deliciously.

“Give me any vegetable and I can ferment it,” says Risavi with a laugh, noting that her product line at any given moment depends on what produce is available, and “what I’m craving.” Nut butters, elderberry syrup, green tea matcha, soups and bone broths, numerous sauerkrauts and even fermented potato salad are all part of the changing lineup. Her most popular items are fermented salsa and vegan kimchi— an in-demand item because kimchi is typically made with fish sauce, a non-vegan ingredient.

You’ll find her foods on the shelves of independent markets like Star Market in Salinas and Elroy’s Fine Foods in Monterey, which carries Wise Goat’s Almond Butter with Lion’s Mane Mushroom, another of Risavi’s most sought-after products. The addition of the unusual ingre-

dient is “because it is a mild mushroom that complements almond butter well, and has a wide range of benefits including cognitive function and immune system support,” Risavi explains.

For the winter months, she plans to debut fermented cranberry relish, Christmas sauerkraut and a detox kraut that includes black Spanish radish, which supports healthy digestion.

Her business has been especially brisk since the pandemic began in March as people have sought ways to stay well. Risavi says, “There’s been an uptick in the demand for health products…I’ve just seen everything shift that way.”

Wise Goat sauerkrauts and gut tonics have developed a cult following at farmers’ markets in the San Francisco Bay Area and other locations around the Monterey Bay, including Lolla in San Juan Bautista and Bertuccio’s in Hollister. The products are also available in a provisions store inside The Smoke Point, the barbecue restaurant that Risavi and Michelin-starred chef Jarad Gallagher started in November in San Juan Bautista. And naturally, some of her foods are served up as sides at the restaurant.

Nut butters, elderberry syrup, green tea matcha, soups and bone broths, numerous sauerkrauts and even fermented potato salad are all part of the changing lineup.

Her creations are all organic and nutrient dense, and the way she prepares them dovetails with a philosophy informed by her studies in traditional Chinese medicine. Risavi earned a master’s in TCM from Five Branches University, and as a nutritional therapy practitioner, follows these teachings in developing her products.

The name of her company comes from observing her own pet goats. Risavi says that contrary to the traditional view that goats are eating machines that devour indiscriminately, they are very particular about what they nibble on, even down to a specific part of a plant. She also noticed that their eating habits vary with the time of day, the season and any health problems they are experiencing.

Humans can learn a lot from goats in this way, says Risavi, and she is also doing what she can to educate her customers about keeping themselves healthy by carefully choosing what they eat.

Consuming foods that contain live cultures helps build a healthier gut, says Risavi, leading to improved digestion and overall health as gut microbes then can extract nutrients from food more efficiently. Trillions of these bacteria live within us, in what scientists call the gut microbiome, and in general, the more diversity you have in this internal population, the better the effects. Fermented products also work to keep body systems in balance, and more importantly, “keep people regular,” adds Risavi.

The entrepreneur first became intrigued by fermenting while working for the Heirloom Organics farm in Hollister, and as she learned more about Chinese medicine, realized that these types of foods are vital for optimal health.

Fermenting is a time-honored way to preserve foods for the winter season, but it also fits neatly into the TCM belief that all foods should be “cooked” in some fashion before entering the body. “It eases the burden on your digestive system,” says Risavi, pointing out that fermenting is a kind of pre-digestive process that also has the advantage of preserving all the nutrients in that food.

It’s also critical to use organic produce grown by farmers who put their hands into the soil and care about the land, she adds, explaining that this increases the chi, or life force, of the fruits and vegetables. “If you remove the human aspect

from farming, there’s no love put into the food,” she says. “If it is done with love, the chi of the food increases.”

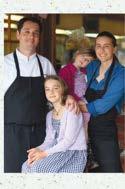

Her product line is so varied that it’s astonishing that Risavi does all this herself, along with two part-time helpers. “She is the hardestworking person I know,” says Gallagher, her business partner and father of their 3-year-old daughter Elsie.

When Risavi first started fermenting, she realized that the way that most people did it was not optimal for best results. Instead of using plastic or metal containers that can leach undesirable chemicals into her mixtures, she opts for glass crocks, and keeps them airtight for an anaerobic ferment—made without oxygen.

To preserve nutrients and probiotic bacteria, she makes sure that the cooking temperature never exceeds 68 degrees Fahrenheit, so that the culture remains live. Her products are also lighter in salt and sugar whenever possible.

Risavi does all processing in a facility she built out of a shipping container, at the ranch where she and Gallagher live and raise their daughter together. Although separated in their personal lives, Risavi says that they function beautifully as business partners and co-parents.

Becoming a parent re-defined what she’s doing with Wise Goat. “I’ve really gotten to know many of my customers personally,” says Risavi, with many of those devotees coming back week after week to farmers’ markets in San Francisco, Palo Alto and other Bay Area locations. “Since becoming a mother, I’ve put a special emphasis on mother and child health.”

Surprisingly, kids (including Elsie) are some of the biggest fans of her pungent and sour foods. “If you introduce those flavors first, that’s what they’ll prefer.”

Santa Cruz native Kathryn McKenzie, who now lives on a Christmas tree farm in North Monterey County, writes for numerous publications and websites. She recently co-authored the book Humbled: How California's Monterey Bay Escaped Industrial Ruin.

Wise Goat Organics wisegoatorganics.com info@wisegoatorganics.com

BY LAURA NESS PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRYSTAL BIRNS

Paula Grainger harvests rose hips from her home garden.

BY LAURA NESS PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRYSTAL BIRNS

Paula Grainger harvests rose hips from her home garden.

She says every herb garden should start with calendula (shown above), chamomile and lemon balm.

Santa Cruz herbalist Paula Grainger believes deeply in the power of herbs to improve overall physical and mental wellbeing. And do we ever need that now. Our ability to cope is stretched, sometimes beyond previously explored limits. Alcohol, anti-depressants and sedatives may not provide optimal solutions; sometimes, ancient herbal remedies are the best choice.

“It is so important to practice self-care at stressful times like these,” says Grainger, who was born and raised in England. “The simple act of brewing oneself a cup of herbal tea can be transformative.”

Nature abounds with herbal treasures, just waiting to be rediscovered. “The line between medicinal herbs and healthy foods is quite close. They are all plants, after all, so there is a huge potential for improved health and wellness, as well as alleviation of chronic physical and psychological conditions using herbs,” she says.

For Grainger, who has been busier than ever since COVID, her path to herbalism began in childhood. “My mother and grandmother were both keen gardeners,” she says. “Britain has a long tradition of herbal healers and I was always fascinated by the idea of plants as medicine.” After realizing in her 30s that being an herbalist was a vocation, she earned a degree in herbal medicine from London’s University of Westminster.

She is here on the Central Coast due to an act of nature, in particular, a volcano. She and her husband and young son were visiting California in 2010 when a massive volcanic eruption in Iceland forced them to delay their return to England. “We found ourselves stranded in Santa Cruz

on a road trip up Highway 1. And we loved it! We ended up being here for nearly two weeks, instead of two nights!”

They ended up falling in love with Santa Cruz, moved here the following year and became citizens in 2019.

In the U.S., Grainger’s profession is termed a clinical herbalist. In England, she was a medical herbalist and permitted to write prescriptions from her apothecary Lemon Balm, named for one of her favorite herbs.

Like a prism, her craft has many facets and thus she has many roles. First, she is a gardener, growing more than 100 herbs that can be put to use in teas, powders, tinctures, balms, lotions and massage oils. Next, she is an herbal wellness consultant, a combination of sympathetic listener, life coach, therapist and herbalist. Third, as a botanical skin care specialist, a byproduct of a lifetime of dealing with her own finicky derma, she always looks for the right combinations of oils and herbs to soothe and heal. Fourth, as a fan of fragrance, she concocts tinctures that uplift and delight. Fifth, she avidly develops new recipes, honing her love of flavors and cooking to help nourish. Last, and perhaps most important, she is a teacher, sharing her love and knowledge of plants in classes and workshops.

Grainger recently published a book called Adaptogens: Harness The Power of Superherbs to Reduce Stress & Restore Calm, in which she cites ancient favorites and their benefits, including ashwaganda (thyroid support, energy), eleuthero, (reduces jet lag, combats altitude sickness),

Grainger has also written a book on therapeutic herbal teas called Infuse.

ginseng (endocrine support, lowers cholesterol, stimulates blood flow), rhodiola (heart support, helps stamina, fibromyalgia, seasonal depression) and schisandra (improves liver function, boosts mood, regulates lung function). These have been employed in Ayurvedic and other ancient traditions for thousands of years.

“Adaptogens are a wonderful group of herbs which, in essence, help the body to deal with the effects of stress. They are the superheroes of the herbal world,” says Grainger. Renowned for their ability to increase stamina, prevent adrenal imbalance, strengthen the immune system, deal with chemo and lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol, each of these storied herbs is given a chapter in her book in which she explains their purpose and how best to use them.

This is not to say there’s no room for Western medicine in your healthcare repertoire. “There is unquestionably an important place for manufactured drugs in healthcare and they save many lives,” notes Grainger. “I do think herbal remedies are underutilized. In general they tend to be milder and more ‘balancing’ in their actions and they invariably have far fewer potential side effects. Thankfully, this community is very open to embracing natural medicine as part of an overall approach to wellness. It’s not uncommon to have doctors here refer patients to an herbalist.”

One way to promote self-care is to cultivate plants. “At a minimum, grow chamomile, calendula and lemon balm,” she says. Lemon balm tea is great to drink in the wintertime, as it is an antiviral that also calms digestion and lifts mood on dark days. Also plant sage, which helps fight infections, and incorporate turmeric in cooking, as it lowers inflammation, supports good liver function and may help fight cancer.

Grainger launched The English Herbalist botanical skincare line in 2014, which includes First Aid Salve made with rosemary, plantain,

calendula and yarrow, luxurious facial serum oil and whipped body butter made with high quality shea and cocoa butters, coconut oil and golden jojoba oil.

She creates personalized regimens for her clients, including customblended teas, but if you want some quick remedies, she recommends her After Dinner tea for supporting good digestion. Another, Happy Tea, as the name suggests, is a blend to lift spirits and alleviate stress. People also love her Bright Skin blend, which incorporates herbs traditionally used to cleanse the system and improve skin health.

What she loves about being an herbalist is that she works to promote wellness, rather than treat specific medical conditions. “I see people with all kinds of things going on—women’s hormonal issues, including menopause and fertility issues, digestive complaints, stress, anxiety and sleep, skin conditions.”

Fortunately, there’s an herb for that.

We asked her what some of the best non-herbal immune system boosters are for the winter months.

Get outdoors daily. Exercise. Meditate. Eat healthy. “Get into some cold water every day,” she adds. “Use herbs, including adaptogens, and lifestyle techniques to manage stress and get enough sleep.”

Laura Ness is a longtime wine journalist who contributes regularly to Edible Monterey Bay, Spirited, Los Gatos Magazine and Wine Industry Network, sharing stories of the intriguing characters who inhabit the world of wine and food.

The English Herbalist paulagrainger.com lemonbalmonline@mac.com

Courtesy Paula Grainger

Courtesy Paula Grainger

This recipe uses codonopsis and ashwaganda for a gentle adaptogenic boost, but use whichever herb powders you like best, and add a few handfuls of goji berries to up the adaptogenic ante. As well as in granola, Grainger recommends using dried herbs and adaptogen powders in teas, smoothies and soups.

Preheat the oven to 340° F. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

Combine the oats, nuts and seeds in a large bowl. Sprinkle with salt. Set aside.

Put the coconut oil and maple syrup in a small saucepan, set over low heat and melt them together. Then stir in the cinnamon, codonopsis and ashwaganda powders.

Spread the mixture evenly over the prepared baking tray. Bake for 25–35 minutes. Stir the mixture 2 or 3 times and keep checking it, because if the granola burns, it will taste bitter. It should be light toasty brown and smell delicious when ready. Set aside to cool and crisp up.

Transfer cooled mixture to a clean bowl and stir in the raisins and chopped dried apple. Store in an airtight container for up to 1 month. Serve with milk or yogurt, or just enjoy handfuls straight from the jar. Makes 1 pound 9 ounces.

powder 1 teaspoon ashwaganda powder ½ cup raisins ¼ cup dried apple rings, chopped

Pour the liquid ingredients onto the dry ones and combine using a couple of wooden spoons or, if you don’t mind getting sticky, your hands.

BY MARK C. ANDERSON PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELLE MAGDALENA

BY MARK C. ANDERSON PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELLE MAGDALENA

The turning point was…pain points. Aptos entrepreneur John Spagnola visited various restaurants and talked with bartenders and beverage directors about the anguish they experience in procuring quality spirits.

But that wasn’t the original plan. He started with an idea for an app to let consumers customize a spirit to their specs, craft a label and have it sent to their home. The app never happened; it turns out it’s illegal for producers to sell directly to anyone without a liquor license.

But what ultimately did emerge could disrupt the liquor industry—and has already revolutionized the spirits program for a range of restaurants in and around Santa Cruz.

Spagnola pivoted from people to places and started doing his rounds. Bar pros liked the idea of a customizable and branded bottle, but their complaints proved even more compelling. Good quality spirits are hard to find at a reasonable price. Certain minimums are required for delivery and/or discounts from distributors. Costs for things like shipping and tax can be hidden. And the games distributors play—requiring purchases of less desirable spirits in order to access nicer whiskey options, for instance—get old quickly.

“Every bar had their own horror story,” says Spagnola, now CEO of 2-year-old startup Ublendit Spirits. “It got me thinking, ‘Can we have a customer service experience that’s all about what the bars want?’”

That is what he and Ublendit have achieved. By slowly vetting all the options for the purest base spirits on the market, including super-proof ethanol, from big and experienced producers like J.B. Thome and Midwest Grain Products, or MGP, the Ublendit team has an affordable starting product, Spagnola explains. By proofing down with hyper-distilled water, applying proprietary recipes and (potentially) barrel aging at their own distillery, they make

world.

it their own. By cutting out the middleman and working directly with restaurants and bars, they have been able to sidestep the chunky distributor markup and focus on client needs.

Today, partner businesses can taste and select from the dozens of gins, rums, whiskeys, vodkas and more in Ublendit’s portfolio, or create something unique, then design a label. Printing, graphic design, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) approvals and legal consulting are included. Required purchase minimums are not.

Suddenly partners like Hula’s, Back Nine, Kianti’s and Britannia Arms are among those that have their own branded bottles. Barkeeps can rep their own stuff, businesses enjoy better margins and customers save a buck.

“Restaurants get something they can be proud of, and if they sell one drink, it pays for the bottle,” Spagnola says. “We don’t worry about a sales pitch, we drop off the product and prices, and let them taste. They feel like we’re on their side.”

Jason Cichon is bar manager at The Catalyst Club, an early adopter. He worked with Ublendit developers on a popular Catalyst Vodka with a light cucumber-kiwi-red clover flavor. “Hanging out in the lab coat designing liquor from the ground up is a playground for any bar manager,” he says. “They made the whole process very involved and fun.”

Ublendit’s first customer might be its biggest believer. After 47 years in the industry across 14 night clubs, personality-plus Chuck Oliver owns Number 1 Broadway in Los Gatos. In non-pandemic times, he reverses a timeworn bar tradition: He graduates clients from back-shelf bottles to his well brand, Chuck Oliver Vodka, using blind taste tests. (He stocks a total of six different Ublendit spirits under his own label.) Oliver estimates he’s done 200 three-way tests, versus Grey Goose and Tito’s, and his namesake has won 180 times.

“I’ve been in this business a long time,” he says. “It’s a no-brainer to have your own spirit.”

So why hasn’t someone tried the Ublendit

model before?

“That’s what I’ve asked a lot,” Spagnola says. He acknowledges the compliance arena—getting labels and ABVs exactly right, braving exhaustive TTB audits—can be terrifying.

“Old-school guys say we can’t keep up, that we’re going to switch our model, that we can’t do so many different choices,” he says, “but if Amazon can have 2 trillion [products], we can have a couple thousand.”

Despite the worldwide—and ongoing— state of crisis for restaurant and bar businesses, Ublendit has been setting records, with 50,000 bottles shipped in July. The day I initially spoke with its team, they were buying the first of two 3,000-gallon stainless-steel

“We were trying to make a product that was approachable and distinct— we were very intentional stylistically.”

holding tanks and an automated bottling line. A new facility is deep into the planning stages; it could potentially make Ublendit a 28,000-square-foot anchor tenant of a buzzedabout mixed use building in Scotts Valley.

Part of that growth is the evolution of Ublendit’s own brands, including Santa Cruz-inspired Westside Water whiskey. Like so many of Ublendit’s developments, it emerged from restaurant requests: Buyers wanted a blended whiskey that could compete with mainstream brands and save them cash. Ublendit’s development team, led by JP Ditkowsky and Tyler Derheim and informed by a lot of bartender taste tests, spent seven months tinkering with the formula.

“We were trying to make a product that was approachable and distinct—we were very intentional stylistically,” Ditkowsky says. “The final blend came together harmoniously.”

Ublendit’s first house brand, Hideout Vodka, got its start when Spagnola and his sales team approached Grocery Outlet about an exclusive product. While initially skeptical, immediate popularity—1,000 cases sold in two weeks—meant Grocery Outlet’s liquor buyer had a hit on their hands. Ublendit has since reached an agreement to add Hideout peach, mandarin orange, vanilla and raspberry vodkas (and to sell Hideout outside of GO, albeit always at a higher price).

At the start of the pandemic shelter-inplace orders, I noticed GO began stocking this new vodka with a grizzly on it for $6.99. My bunker’s bar didn’t have vodka, so I figured: What was there to lose?

Sure enough, it blew me away: A perfectly defensible, even above average, fifth of vodka, for a fraction of the price of inferior spirits. When I found out it was made locally, all the better.

In other words, Ublendit Spirits spoke for itself. Which is something a lot of people are starting to hear.

Mark C. Anderson is a roving writer, editor and entrepreneur loosely based in Monterey County. Follow and/or reach him on Twitter and Instagram via @MontereyMCA.

Ublendit Spirits ublendit.com westsidewaterwhiskey.com 831.227.6375

I distinctly remember falling in love with kiwifruit. It was the summer of 1989 and I was on a road trip in a camper with my best friend Mindy and my aunt and uncle. We were headed up the coast from Los Angeles to Canada and I remember every time we stopped to gather provisions, I bought loads of kiwis. I ate them obsessively while we played gin rummy, bracing myself on the curves of Highway 1 while looking out the window at the dramatic coastline. This is also when I fell in love with Big Sur and the Central Coast. I credit the vitamins and sugar in those kiwis for helping me beat my friend in countless card games during our long trek.

Surprisingly, kiwis have more vitamin C than an orange per cup. Just one cup of kiwifruit has 276% of our necessary vitamin C, which boosts our immune system to ward off colds and flu. Too bad sailors didn’t know about kiwis when they suffered from scurvy; they could have loaded up on the long storing, tasty fruits instead of eating lemons! Kiwis have a lot of fiber and an important enzyme that helps digest proteins called protease. If you eat a couple each day, they will also help reduce blood clotting and fat in the bloodstream.

Kiwifruit is native to China and dates back to the 12th century. It was originally called Chinese gooseberry—yet oddly it is not actually in the gooseberry family. Over time, plants migrated to New Zealand, leading to the beginning of commercial cultivation in the early 20th century when both American and British soldiers became fond of the fruit. By the 1950s kiwis began to be exported to Great Britain and California. But it was during The Cold War and the name Chinese gooseberry was

not going to help market this exciting, new fruit. The name was briefly changed to “melonettes” but shippers quickly realized that name wasn’t going to work either, because both melons and berries had high import tariffs. Brainstorming ensued at a New Zealand marketing firm leading to the name kiwifruit and that became the official name in 1959 in a nod to the place it became popular. Kiwi is a type of bird, but also a common nickname for people from New Zealand.

Currently China produces half of the world’s kiwifruit, Italy the second most and New Zealand the third. The U.S. has about 8,000 acres in production, with most of the kiwi farms in California. The world currently produces about 170,000 acres, equal to an estimated 1.7 million tons of kiwifruit.

Actinidia deliciosa, the fuzzy light brown kiwi we are used to eating, are the size of a large chicken egg and have black edible seeds within their striking green flesh. However, New Zealand kiwi grower-shipper Zespri offers a “sun gold” yellow kiwi that is much sweeter, and will be introducing a red fleshed variety, described as having “berry-tinged flavor.” However, all have fuzzy skin.

There are also smooth-skinned “hardy” kiwis, Actinidia arguta and Actinidia kolomikta, which can survive temperatures down to 10 degrees. These cousins to the common fuzzy kiwi are the size of a grape and can be eaten whole. The plant, grown in the Pacific Northwest, is more of a bush than a vine, and looks completely different than its kiwi cousin. Hardy kiwis have become a novelty, and are now being marketed as “kiwi berries.” There is also a rare hardy kiwi with red skin that Rare Fruit Grower groups are propagating, however it is not yet available commercially.

For planting, pick a site that has full sun, is protected from the wind and has well-drained soil. Kiwis do well on drip irrigation and like to be kept moist, however soil needs to be well draining because they are susceptible to root rot. Both female and male plants are needed to produce fruit, so for every eight females you will need one male plant for even pollination. Plants will need to be spaced 10–15 feet apart as they grow vigorously and produce heavy fruit—up to 100 pounds per vine. A sturdy T-bar trellis system is required and it needs to be tall enough to be able to walk under to harvest the hanging fruits.

Even though kiwis reach their full size around August, you must wait to harvest the vines until the seeds have turned black. By late October through mid-November the fruit will have developed enough sugar content to be harvested. But at harvest they are still hard and inedible until they further ripen off the vine. Sugar content goes from 4% at harvest to 15% when ripe. Kiwis will also ripen on the vine, but farmers take the crop off all at once and store it until they sell it. In this way, kiwifruit are a great crop to store, sell and eat all winter long.

In the winter, plant a cover crop between the rows and turn it under in the spring. Kiwis take about four years to grow a full crop, although you will get a few fruit before then. In the spring, summer and fall, apply a well-balanced, organic pellet fertilizer.

Kiwis need to be pruned heavily (70% off the vine) each December to let in light to ripen the fruit and keep diseases and fungus away. Fruit forms on new growth, so it is important to cut off old growth to stimulate the new.

Four Sisters Farm grows two acres of certified organic kiwis, along with specialty greens and flowers in Aromas. Nancy and Robin Gammons named their farm Four Sisters after the four daughters they had within six years in the 1970s. Robin’s father planted the original orchard on their property in 1986 after reading that kiwis were the exciting, up-and-coming specialty crop that would grow well in their microclimate. Yields in earlier years were up to 40,000 pounds a season, but they still harvest from this orchard. After 30 years in production, the kiwi vines continue to produce a crop that would make Robin’s dad proud, but closer to 14,000 pounds per acre. Four Sisters Farm kiwis are sold at three farmers’ markets—Downtown Santa Cruz, Berkeley and Ferry Plaza in San Francisco. Nancy says originally kiwis were overplanted in California, as people learned about the interesting new fruit. Farmers thought they would make a lot of money on kiwis and then found out differently. For Four Sisters, however, it is a great crop going into fall and winter when its other crops are finishing up. They start harvesting in the beginning of November and sell them all winter until they run out, usually in April. One of the Gammons daughters is interested in farming and as Nancy says, “One out of four isn’t bad!” Her daughter Jill grows

I love kiwis on fruit tarts. I once peeled, sliced and dipped them in melted chocolate and froze them for a tasty treat. I have made delicious kiwi lime curd and a kiwi chutney, and included kiwis in a fresh salsa. Try mixing chopped kiwis with mangos, papaya and fresh mint, and placing on top of a fish dish or simply eat on top of yogurt.

There are many ways to skin a kiwi, if you will. I learned the easiest method from a child I babysat long ago. Cut in half and scoop with a spoon. You can also cut off both of the ends and remove the skin gently by pushing a spoon inside along the inside of the peel until the round chunk of kiwi falls out. This is the easiest way to get the whole kiwi out to slice it prettily for tarts, and makes quick work of peeling. I asked Nancy of Four Sisters Farm how she cuts and eats her kiwi fruit and she said she eats them like an apple, fuzz and all! I was surprised at her response, and thought her hard core, but then what farmer isn’t?

I wondered if there were any benefits to eating the skin and it turns out kiwi skin has 50% more fiber than the fruit itself. The skin contains pectic polysaccharides that retain water and form a gel which is good for your gut. It also has cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, which add bulk and facilitate efficient digestion. So go ahead and slice the kiwis thinly with the skin attached to be sure to reap all the benefits. Or throw them in a blender, skin and all, to make a fabulous smoothie—your stomach will thank you!

Jamie Collins is the owner of Serendipity Farms and attends all of the Santa Cruz Community Farmers’ Markets, where you can find her fresh organic fruit, vegetables and nutrient-dense prepared food items.

5 kiwis, peeled and chopped 1 cup whipping cream ¾ cup sweetened condensed milk 1 teaspoon vanilla

Peel, chop and freeze kiwis.

Whip whipping cream and combine with condensed milk. Add frozen chopped kiwi.

Place in a metal brownie pan or loaf pan, and place in the freezer. Stir after it begins to freeze. Eat after it’s frozen. Enjoy! Serves 4.

Courtesy Nancy Gammons, Four Sisters Farm

There’s something sweet about living in the Monterey Bay area. Could it be the multitude of beekeepers and the local honey their hives produce? Here are some of our favorite healthy, therapeutic and delicious local honeys. Try them all! (clockwise from top right) Poison Oak Blossom Honey, The Honey Ladies (Watsonville); Orange Honey Crème, Malabar Trading (Santa Cruz); Sage Honey, Eichorn’s Country Flat Farm (Big Sur); Bee Pollen, Post Street Farm (Santa Cruz); Big Sur Wild Honey, Bonny Doon Farm (Santa Cruz); California Wildflower Honey, Carmel Honey Company (Carmel); Scotts Valley Honey, Santa Cruz Bee Company (Santa Cruz); Honeycomb, Post Street Farm (Santa Cruz).

What will it take for restaurants to make it through these uncertain COVID times?

BY MARK C. ANDERSON PHOTOGRAPHY BY COLINE LECONTEAttractive parklets in Pacific Grove provide outdoor shelter for winter diners.

Business is good. That’s not a misprint.

That was one of the unanticipated takeaways that emerged as Edible Monterey Bay spoke with a swath of chefs and restaurant owners to learn what they’re doing and how they’re feeling as winter with COVID descends.

To be clear, business is only improving for a fraction of restaurants in the Monterey Bay area. Still, those success stories exist.

Some restaurant pros have closed restaurants, some have opened new spots and at least one has both closed and opened places. Some are cautiously optimistic, some are mad, some are bitter. Many are sad, plenty are scared and several are upset.

Every single one proved reflective. While they may not know where this crisis is taking the local industry, they are weighing why they do what they do more than ever.

Carolyn Rudolph, co-owner of Santa Cruz institution Charlie Hong Kong, is among them.

“Serving people healthy food is our spiritual practice,” she says. “When you’re under stress, you need healthy food.”

As this went to press, her chefs were scrambling their annual farmworker feed at Lakeside Organic Gardens—which supplies CHK a full ton of chard monthly—and unloading all the spicy Dan's noodles with bok choy, cabbage, broccoli and coconut peanut sauce that the workers could want.

Meanwhile Rudolph, et al. were remodeling long-ignored takeout windows at the former Frosty Freeze to streamline to-go orders, with vegetable art painted on the sidewalk to remind eaters of safe distances.

Since most of its business is takeout, its pricing easy on shrinking budgets and its patio welcoming for outdoor dining, Charlie Hong Kong was well-equipped to survive when COVID came crashing into town. But as important as its practical preparedness might’ve been, so too is its philosophical approach.

“It’s possible to view adversity as an opportunity,” Rudolph says, “to look at it with curiosity, [asking] ‘What’s happening here? What does this mean? What can we offer?’”

The Pocket debuted in Carmel on one of the more difficult dates in modern history: March 19, 2020. After 15 long months of construction to overhaul the former Christopher’s—and after assembling a decorated team of restaurant lifers—chef/co-owner Federico Rusciano held a soft opening for his restaurant then abruptly had to close it.

Even with eight decades of collective experience between co-owner Kent Ipsen and himself, Rusciano was caught flat-footed. He describes April and May as “sleepless.”

“There is really no comparison to any other scenario that Kent

and I have witnessed before,” he says. “The most surreal thing was to see a dream fade away…and it was terrifying for a new business, considering the huge investment in the property.”

As soon as they were allowed to open for al fresco dining, they pounced on the opportunity with expanded hours, an all-day menu with reduced price points and spaced outdoor seating that added heaters, maximized the patio and captured street parking spaces. They’re currently adding an awning and a custom windscreen to make the patio more hospitable for winter, while building a seasonal menu with items like black truffle gnocchi and bucatini carbonara.

“We adapted quickly, and we’ve been lucky to be busy,” Rusciano says.

Owner-operator Ted Burke and crew at the Shadowbrook in Capitola are applying expanded hours themselves—it now opens at noon rather than 4pm—and embracing new technology (on top of constant sanitizing of the property and the iconic cable car that shuttles visitors down to the riverside destination). A new time clock scans employee hands and temperature when they punch in and flags any for bacteria or fevers.

Loyal patrons remain a lifeline, but he’d love more leadership from

Gov. Gavin Newsom. “He has color codes, but no metric and no goal to get back to normalcy,” Burke says.

Patrice Boyle identifies. She directs La Posta and Soif Restaurant + Wine Shop in Santa Cruz.

“Restaurants and small businesses are basically left on their own to make decisions,” she says. “There’s not really a lot of guidance from the city, county or state, and certainly nothing from the federal government.”

She considers retiring, daily, only to renew her enthusiasm by observing her staffers. “What this has brought home more than anything is how great the people are who work with me,” she says. “Many of my cooks have been with us for 15 years—that’s a long time in dog years, and longer in restaurant years. I want to stay here for them.”

Her number one request of government: grant restaurants some security by guaranteeing sidewalk and parking lot dining will be fee free and around long enough to merit the investment of enhancing the experience. San Francisco works as a model, as it’s done away with permit fees for outdoor café tables and chairs, parklets for outdoor dining and display merchandise for retailers through mid-April 2022.

“Small businesses have moved heaven and earth to survive this

“We’re still doing what we love to do, only now it’s in people’s living rooms rather than our restaurant.”

pandemic,” said San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin, when his ordinance passed unanimously. “The city has done everything we can to accommodate small business while keeping transmission rates low.”

Chef-partner Ben Spungin has figured out a way to diagnose who’s really into Alta Bakery’s candied ginger scones and chocolate chip banana bread, runaway crowd favorites for the newish Old Monterey spot.

“When they hear we’ve sold out and leave immediately,” he says. “That’s one way we know they love them.”

That enthusiasm applies to the wider restaurant, where the retailoriented, counter-service approach has kept Alta doing brisk commerce, with a boost from to-go dinners introduced quickly in response to COVID closures. Revenue records have been a monthly occurrence, per partner Kirk Probasco.

“What we do at Alta is really simple food, easy preparation, a nice job using fresh food,” Spungin says. “That’s what I think people want. They don’t want overdone or overly complex.”

That style will guide adjacent sister spot Cella, which is to open, with a bistro concept driven entirely by seasons, by the end of the year, with dinner six nights a week and Sunday brunch.

“We want it to be a neighborhood restaurant, super casual, featuring fresh foods and an ever-changing menu,” Spungin says. He envisions a few appetizers, a small raw section, limited entrées like a burger, a pasta, a chicken plate, a darker meat creation featuring duck, lamb or steak, and a fish dish, plus some sides.

Ample outdoor space built around the comely gardens at the Cooper Molera Adobe will remain crucial.

“I can’t stress enough how magical Cooper Molera is,” Probasco says. “There’s a reason John Cooper chose that property 200 years ago: The property chose him.”

Probasco adds that he’s concerned for restaurants without outdoor options and the industry in general.

“It’s intense, as well as scary-making,” he says. “Newsom is going to be pressured into opening more indoor dining in Monterey County sooner or later. Otherwise a lot of places will fail this winter.”

Across the bay, Home restaurant is experiencing a similar boom thanks to circumstance, collaboration and outdoor dining.

“The space we have could not have been more suitable to the pandemic,” says chef/owner Brad Briske.

He has a point. With twothirds of an acre given to garden and patio, outdoor dining rules have made Home an inviting option, with tables 12 feet apart on the lawn, under citrus trees and alongside the chicken coop.

But the suitability extends to other aspects. Combining his wife/co-owner Linda Ritten’s background in farmers’ markets and his in whole-hog butchery, they’ve doubled down on pre-made market offerings like freshly extruded pastas, sausages, grass-fed beef bolognese and Fogline Farm chicken liver pâté. Buying in bulk and maximizing yield, it turns out, is good business. (They’re doing farmers’ markets in Downtown Santa Cruz on Wednesdays, Westside Santa Cruz on Saturdays and Live Oak on Sundays.)

“There’s profit there for us and customers get to buy things they’ve never been able to buy before,” Briske says.

With Briske managing all the restaurant ordering, kitchen duties and more, and his wife running the front of the house, they were able to scale tasks economically in ways operations with more overhead can’t. Kitchen staff has grown to support more butchery. Furniture donations from other restaurants, garden upgrades and chicken coop construction have all happened. Next up is a roof for the driveway that will allow a dramatic uptick in people served.

“I’m working more than I ever have, but it’s insane how much we’ve upgraded in the pandemic, how much it’s grown and how much better it’s gotten,” Briske says. “It’s not possible without restaurant people and those in our life who want us to succeed.”

At popular Poppy Hall in Pacific Grove, chef Phil Wojtowicz is doing his own reframing of the restaurant game.

“We’re still doing what we love to do, only now it’s in people’s living rooms rather than our restaurant,” he says. “Fun dining, not fine dining, has always been our thing.”

Much of that is built on the spiritual scaffolding Charlie Hong Kong’s Carolyn Rudolph described.

“This is our whole life,” Wojtowicz says. “We cook, we’re good with food. That’s the whole point. We’re not doing cartwheels because we’re making it [in tough times]. We are doing it because that’s what we do.”

Other restaurants are using the slowdown to reimagine their identities; Cult Taco in downtown Monterey is going vegan, along with its coastal California-Oaxaca fare, Pearl Hour in New Monterey has blossomed into a coffee shop-tavern concept and longtime industry leader Dory Ford has taken the moment to rethink everything.

He closed his restaurant and mothballed his pioneering Aqua Terra private event outfit last February—before most of his peers realized what was about to happen.

“I used to work nights, weekends, holidays,” he says. “Now I don’t. I have an opportunity to really open my eyes. It’s a paradigm shift. [COVID-19] has made a lot of people really re-think.”

After he abdicated Point Pinos Grill, the city of Pacific Grove published a request for fresh proposals to take over the space.

In the end, restaurateur Tamie Aceves earned the lease. In the last six months she 1) helped lead the campaign for Pacific Grove Al Fresco and its polarizing outdoor dining COVID response; 2) shut down her popular cafe-restaurant Crema; 3) saw her catering business bottom out; 4) became a founding member of the Pacific Grove Restaurant Association; 5) opened Lucy’s on Lighthouse gourmet hot dog/dessert restaurant; 6) started planning for Point Pinos; and 7) slowly started re-introducing micro-events at The Holly Farm in Carmel Valley.

So she’s a poster business person for the WTF-is-happening, let’s-dothis, panic-inducing pandemic times. When asked how she’d sum up the last five months, her voice catches.

“It’s been really hard,” she says. “My team gives so much.”

But her focus sweeps from the rearview to the road ahead, with plans for brunch, lunch and a 3–7pm happy hour at her new venture, The Grill at Point Pinos—borrowing from Crema hits, a “fun California yacht club feel,” and golfer-centric grab-and-go fare—along with new 7am coffee hours and community-building activities at Lucy’s, plus ambitions for P.G.’s upstart restaurant association to find new solutions to deal with the pandemic.

Which is encouraging. Because if there’s a solitary takeaway from the expanding months of tragedy and unraveling, it’s that we’ll need new solutions to keep appearing on the menu.

“The most surreal thing was to see a dream fade away…and it was terrifying for a new business, considering the huge investment in the property.”Chef/co-owner Federico Rusciano pours wine for a couple at The Pocket in Carmel, while a server at Home delivers a salad and to-go orders await pickup.

Their shells are the color of midnight and deep water, but wild California mussels (Mytilus californiensis) are found at the Pacific shore, in rocky intertidal areas of the open coast. Their elongated shells, bristled with barnacles and beard, hide a delicate, succulent orange flesh that needs nothing more than a little steaming to prepare. Imagine a fire on the beach and a cast iron Dutch oven. There is a crusty loaf, a simple white wine, garlic sauce and the mussels in a basket, clacking softly against one another, gathered from the intersection of sea and stone.

We’ve always loved foraging and eating outdoors, but in these times especially, there is almost no more pleasurable way to pass the afternoon than on the beach with a small group of friends, gathering and preparing a simple wild meal. The brisk air whisks the aerosols away, and a crackling hardwood fire warms cold fingers, stiff from prying shellfish from the rocks. Roll up your pant legs, consult the tide book and remember never to turn your back to the ocean. Mussel season is here.

The old adage that mussels should only be harvested in months spelled with an R is a false one, at least for our climate and ecosystem. The warm water currents that can lead to red tides are often still present here in September and October, so the mussel season is officially closed from May 31–Oct. 31, to reduce the likelihood of shellfish poisoning. (See sidebar for more details.) Once you’ve checked the calendar and called the biotoxin monitoring hotline to check in, you’ll need a fishing license, available for the day or for the entire year, at sporting goods and marine supply stores. Keep it on your person at all times while foraging or fishing; the fines for non-compliance are steep.

An individual is permitted to gather up to 10 pounds of mussels a day with a fishing license, so a scale may be in order, but few other tools are permitted, as California law requires mussels to be gathered by hand; no crowbars, trowels, or other tools are allowed. Thick leather gloves can protect the hands, but may also reduce dexterity as you pluck the choicest morsels from their rocky beds. Any low tide—up to +0.5—will suffice to gather mussels, though the lower the tide,

the larger the mussels may be. Still, bigger isn’t always better; a huge 8-inch mussel may have a rubbery texture, while a more diminutive but still hefty 4-inch mussel approaches the divine. Being filter feeders, mussels may contain a fair bit of sand, and mussels closer to the sandy seafloor will contain more than those harvested a foot or two higher.

After you harvest them, keep the mussels cool in a bucket of clean seawater. Some folks like to take the mussels home and soak them overnight in cold water, allowing them to flush out most of the sand or grit from their digestive tracts by the next day. That’s all well and good, but if you want to cook them on the beach that day, there are other tricks to use. We harvest into a basket, then clean the mussels one by one and drop them into a bucket of fresh seawater after they are cleaned. Even a 30-minute soak in the water is often enough to get the mussels to open up and expel a bit of their grit. Use a stiff bristled brush, or even a sharp scraping stone or knife, to remove the tough beard from the outside of the mussels, then drop them into the water to stay cool while you clean the others. Discard any with cracked shells or open shells that do not close when tapped.

Wait a while, build a good fire, pop open a beer or sip some cool sauvignon blanc. When the coals are nice and hot, gather seawater from beyond the foaming waves, where it should have no suspended sand particles. If you are unsure how much grit might be suspended in the water, you can always gather it in a container and allow it to settle, then carefully pour off the clear water into the cooking vessel. Rake a bed of hot coals off to the side, but keep a bit of wood burning nearby to replenish the coals if needed.

Next, set a Dutch oven over the coals and fill it with a few inches of clean seawater. Drop in a steamer basket, so that there is space between the bottom of the pot and the basket. When the water has reached a hard boil, drop the mussels in, a dozen or so at a time, and add a few slices of lemon. Steam the mussels over rapidly boiling water for 7–10 minutes. As they cook, the shells will open and any remaining sand should slip beneath the bottom of the steamer basket. The roiling foam of the boiling water rinses them clean.

Slurp the mussels straight out of their shells or place them in a bowl and drizzle with white wine and garlic sauce. If you make the sauce at home and keep it in a thermos, you can avoid having to cook anything else on the beach! Handle each shell individually and savor the meeting of elements. Mop up excess sauce with a hunk of sourdough, if desired.

Jessica Tunis lives in the Santa Cruz Mountains and spends her time tending gardens, telling stories and cultivating adventure and good food in wild places.

The old adage that mussels should only be harvested in months spelled with an R is a false one.

Recipe courtesy Jessica Tunis

2 cups dry white wine

3 large shallots, finely chopped

4 cloves garlic, finely chopped

½ teaspoon sea salt

¼ teaspoon fresh ground pepper, plus more to taste

3 tablespoons fresh thyme, stems removed and minced

¼ cup fresh flat-leaf parsley, finely chopped

1/3 cup butter, cut into pieces

In a heavy bottomed pan over medium heat, combine the wine, shallots, garlic, salt and pepper, and simmer for 5 minutes. Stir in the herbs and butter. To enjoy on the beach, immediately pour into a thermos to keep the sauce warm. Pour over mussels or use as a dipping sauce. Serves 4–6.

Foraging at low tide near Pigeon Point.

In our area, mussels should generally be harvested only from November–April; the rest of the season is off limits. That’s because of the seasonal nature of red tides that sometimes beset our coastal waters. Red tides get their name from a natural, cyclical overgrowth of a category of phytoplankton known as dinoflagellates, the microscopic masses of which, when in full bloom, can stain the seawater with a reddish hue that is not always visible to the naked eye.

Red tides can be caused by several different species, and some (but not all) of these phytoplankton produce toxins that can be absorbed by filter feeders like shellfish. These toxins, if ingested, can cause serious illness, amnesia, paralysis and even death. The conditions that cause these blooms are carefully monitored and it is always a good idea, before harvesting mussels or any other seafood, to check the latest information regarding current seafood health advisories and quarantines.

The California Department of Public Health maintains a toll-free number that makes it easy to keep tabs on any current outbreaks of shellfish poisoning. As the climate warms, we may see more red tides in our future, so don’t assume that because of the calendar date, everything is good to go. Call 1-800-553-4133 to confirm your safety before doing any coastal foraging.

In these challenging economic times, many worthwhile charitable organizations find themselves in a precarious financial position. Meanwhile, they are experiencing unprecedented demand, especially those charities that provide basic needs like food and shelter.

Thankfully, new, unique provisions in the tax code have been implemented in response to the COVID-19 crisis, creating more incentives for giving. You may be able to better leverage your donations with tax-smart strategies. So, if you’re able to extend your generosity during this time of increased need, it may be an opportune year to make contributions to charity.

In 2020, the standard deduction is $12,400 for a single tax filer or $24,800 for a married couple filing a joint return (even more for those age 65 or over). Your itemized deductions would need to exceed those levels to benefit from itemizing. Those who don’t typically itemize are not able to deduct charitable contributions from their taxes. However, on your 2020 tax return, you will be allowed to deduct up to $300 in cash contributions to qualified charities even if you choose the standard deduction.

If you do itemize deductions and plan on giving large gifts, you can now claim a deduction valued

at up to 100 percent of your adjusted gross income (AGI) for charitable contributions, due to a unique provision for 2020. Previously, the tax rules prevented you from claiming a deduction that exceeded 60 percent of your AGI in a single year. If your financial circumstances put you in a position to make substantial gifts, this is the most favorable year, from a tax perspective, to do so.

Another special provision for 2020 allows individuals subject to Required Minimum Distributions from IRAs and workplace retirement plans to forego those distributions. If you don’t need to draw from your IRA to meet your income needs for this year, you still have an opportunity to put the funds that would have been RMD dollars to use as a charitable contribution. The most tax-efficient way to do so is with a Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD). In this way, you may contribute to charitable organizations up to $100,000 per year. With a QCD, if you are 70.5 years or older, funds are distributed directly to the charity from your IRA so you don’t have to claim the income before making the contribution. That is a tax-saving strategy you can use whether you itemize deductions or claim the standard deduction.

Given the current economic challenges, your circumstances today and your financial future may require careful re-assessment. Your charitable giving strategy should be incorporated into a review of your comprehensive financial plan. Check with your financial advisor and tax professional as you consider your options for giving in 2020 and beyond.

Erik Cormier is a Financial Advisor with Cormier Financial Partners, a private wealth advisory practice with Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc. He specializes in feebased financial planning and asset management strategies and has 13 years of experience in the financial services industry. To contact him, email Erik.Cormier@ampf.com or call 408-472-0757. Registered office address is 522 Ramona St, Palo Alto, CA 94301.

Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc. and its affiliates do not offer tax or legal advice. Consumers should consult with their tax advisor or attorney regarding their specific situation.

Investment advisory products and services are made available through Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc., a registered investment adviser.

Ameriprise Financial Services, LLC. Member FINRA and SIPC.

© 2020 Ameriprise Financial, Inc. All rights reserved.

Legal File #3059209

Bartender Francis Verrall showcases the bittersweet Italian digestivo at Pacific Grove’s Mezzaluna

BY RAÚL NAVA PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARGAUX GIBBONS

BY RAÚL NAVA PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARGAUX GIBBONS

Watching the regulars at Pacific Grove’s Mezzaluna Pasteria & Mozzarella Bar reveals a ritual.

After enjoying chef-owner Soerke Peters’ menu of Italian-inspired charcuterie and pastas, diners enlist the services of head bartender Francis Verrall. After speaking together in hushed tones, Verrall returns to the bar and pensively peruses the shelves. He unscrews the cap of one bottle, takes a whiff and returns it to the shelf. He inspects another and another, but puts them both back. Finally, his eyes perk up. He brings a bottle to the bar and pours its sepia solution into a delicate tulipshaped glass.

A bouquet of aromas begins to blossom. One sip tantalizes the palate. A smack of sugar and bright floral notes lands first, then builds to bitter orange peel and licorice. Luscious cola and molasses linger at the finish.

The beautiful Back to Black cocktail combines bitter and smoky flavors.

On the next page, Francis Verrall, who was born in England, tended bar in Brooklyn and Manhattan for 10 years before moving to Pacific Grove.

What is this mysterious elixir? Amaro.

Amaro (or amari, plural) is a class of Italian bittersweet herbal liqueurs, the origin of which dates back more than 200 years. It starts with a neutral base (either a spirit or wine) infused with a variety of botanicals—herbs and flowers, citrus and bark, seeds and spices. Every amaro recipe is distinct, a proprietary secret passed down through generations of distillers, its flavors reflective of the terroir of the region where it’s crafted. In southern Italy, where citrus groves are abundant, amari tend toward the sweeter side. In the north, amari carry fragrant, herbaceous notes from the flora growing in the shadow of the Alps.

Amaro was first created for medicinal purposes, and—like many spirits—owes its origin to medieval monks. Tending the garden, they had an intimate knowledge of local botany, which proved instrumental in crafting restorative tonics. The earliest amari served as digestive aids to settle the stomach after a meal. (At the time, poor preservation of food led to many ailments and natural herbs brought soothing relief.)

Growing demand in the 19th century pivoted production of amaro from the church to commercial operations, giving rise to the amaro we know today. Sugar became an integral part of the recipe to soften the bitter herbs, making it more palatable—and popular—as an after-dinner drink, or digestivo. With their medicinal applications, many amari remained legal during Prohibition, often with a doctor’s prescription. After World War II, amaro shed its reputation as a solely curative concoction and became something to sip and savor simply for pleasure.

Amaro surged in popularity over the past decade. The obligatory bottle or two used to sit obscured behind more popular spirits, but now bars in major cities proudly spotlight their bitter boozes for eager customers. Verrall recognizes bartenders helped foster this newfound appreciation for amaro in the United States. “Diners ask, ‘Oh, what do you like?’ and we answer, ‘Amaro.’” On their recommendation, Americans are discovering the bitter Italian favorite.

“I think people are more adventurous these days,” observes Verrall. “People’s tastes are changing, especially with bitter things.” He cites diners’ appetite for bitter chocolate, bitter greens, bitter beer and bitter cocktails.

Verrall takes pride in his role as amaro ambassador and steward for the storied history of the bitter beverage. He’s not just awakening palates to new bittersweet flavors, he’s often helping diners rediscover family

traditions. “With the connection Monterey has to Italy, I’ve seen a lot of younger people interested in amaro because their grandparents drank it,” he says. “They want to try it because it’s part of their heritage.”

Verrall stocks what’s likely the largest selection of amari in Monterey County. Mezzaluna’s bar boasts 35 amaro options and Verrall aspires to grow the collection even further to 50. “You find something you love and really go for it. I’d like to be known for having a crazy selection of amaro.”

He’s quick to remind that amaro isn’t a singular spirit, but a spectrum of styles. “Amari come in so many different flavors.”

Light amari—Meletti, Nonino and Montenegro—are citrus forward and make for easy sipping, while others—Averna and Lucano—have a bit more body to them with darker color and more alcohol. Herbs dominate Bràulio and other Alpine amari, while vegetables lend bitter notes to Cynar, made from artichokes.

Others may be smoky, like rabarbaros made with dried Chinese rhubarb, and evoke comparisons to mezcal or Scotch. Fernets are brawny versions with higher proof and bold notes. This style enjoys celebrity status now thanks to the Fernet-Branca brand, a bartender favorite (see sidebar page 46).

Amaro translates to “bitter” in Italian, but don’t confuse amari with bitters. Bitters—like Angostura or Peychaud’s—are intense tinctures of alcohol and botanicals that accent a beverage, but amari are milder (and, unlike bitters, potable) thanks to lower alcohol by volume and the addition of sugar.

There’s a whole world of bitter liqueurs beyond amaro too. Herbaceous German Jägermeister and Underberg appear similar in taste and appearance, but fall under their own classification. On bar shelves, amari often sit alongside Italian aperitivo spirits—Aperol, Campari and such— but Italian traditions do distinguish the two.

There’s no strict rule, but aperitivi tilt toward tart citrus to awaken the palate before a meal while amari slant sweeter as the meal’s final flourish. However, many aperitivi share the same bitter ingredients as amari and many low-alcohol amari are increasingly popular in pre-dinner spritz cocktails. A more reliable distinction? Aperitivo spirits are usually lighter in both color and alcohol content and they’re usually served mixed (not neat).

Unlike Champagne or Prosecco, amaro production doesn’t enjoy protected status. The growing popularity of amari has inspired many domestic interpretations from distilleries across the U.S. Verrall notes many new and inventive options from distilleries coast to coast. “Italian amaro? Those guys have been making amaro for hundreds of years from an old family recipe. American amari are still so young and people are trying different stuff.”

Pineapple Amaro from Minnesota’s Heirloom Liqueurs spins a tropical twist with sweet pineapple that softens the bitter blow. Falcon Spirits’ Fernet Francisco is a homegrown take on the city’s beloved Fernet-Branca—the other San Francisco treat. Amaro Angeleno from Ventura Spirits in southern California celebrates citrus in a spirit it cheekily calls a “Caliamaro.” Don Ciccio & Figli of Washington, D.C. transports family liqueur traditions from the Amalfi Coast to America with its C3 Carciofo that riffs on the classic Cynar.

When choosing selections for Mezzaluna, Verrall prioritizes quality over quantity. He’s

careful to sample and scrutinize each prospective addition. He has curated the list purposefully to assemble a diverse assortment. “I’ve got a selection of fernet styles, more Alpine styles, lighter and medium-bodied amari, more citrus-driven amari—I have something for everybody.”

Asked to select an amaro for a diner, Verrall is methodical, much like a sommelier recommending a bottle of wine. He asks questions to gauge a diner’s palate before offering a suggestion.

For novices, Verrall recommends Meletti, which is Mezzaluna’s top-selling amaro. “It’s really approachable, a lighter style amaro,” he explains. Notes of violet, saffron and caramel balance its gentle bitterness.

Amaro enthusiasts will recognize many of the storied brands from Italy at Mezzaluna. “When I started out, I had the ones that I knew that many people were familiar with. As time has gone on, I’m trying to find more small-distribution amari you can’t necessarily find in your local liquor store.”

What’s his personal pick? “I like something that’s balanced. I tend to go for more Alpine amari.” Bràulio—made with 13 fresh herbs including gentian, juniper, peppermint, star anise, wormwood and yarrow—is his favorite. But Verrall emphasizes there’s room for all amari, of course. “That’s what I like personally, but I appreciate all amaro flavors, really.”

Raúl Nava is a freelance writer covering dining and restaurants across the Central Coast. His favorite amaro is Cynar. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram: @offthemenu831.

Where to Buy Amaro

Want to try a taste of amaro? These local restaurants and bars have standout selections to enjoy neat or served in cocktails.

515 Kitchen & Cocktails

515 Cedar St., Santa Cruz 831-425-5051, 515santacruz.com

Mentone

174 Aptos Village Way, Aptos 831-708-4040, mentonerestaurant.com (Full bottles also available for retail purchase)

Mezzaluna Pasteria & Mozzarella Bar 1188 Forest Ave., Pacific Grove 831-372-5325, mezzalunapasteria.com

Pearl Hour

214 Lighthouse Ave., Monterey 831-657-9447, pearlhour.com (Full bottles also available for retail purchase and delivery)

Looking to stock some amaro for your home bar? Try one of these local liquor stores.

Deer Park Wine & Spirits

783 Rio Del Mar Blvd., Ste. 27, Aptos 831-688-1228, deerparkwines.com

41st Avenue Liquor 2155 41st Ave., Capitola 831-475-5117

Pacific Grove Bottle Shop 1112 Forest Ave., Ste. 5105, Pacific Grove 831-372-6091

Shopper’s Corner 622 Soquel Ave., Santa Cruz 831-423-1398, shopperscorner.com

Bitters & Bottles in South San Francisco also offers a diverse selection of amari for shipping within California. Order online at bittersandbottles.com.

Coast of Gold is a cocktail made with California amaro.

Amaro is so bitter that it wasn’t often used in classic cocktails. Some—like the Hanky Panky and Toronto—do include petite portions of Fernet-Branca. But these days, bartenders increasingly incorporate amari into socalled new classics, often substituting amaro for sweet vermouth with alluring results. Try your hand at these favorite cocktails from Mezzaluna’s head bartender Francis Verrall.

The best-selling amaro cocktail at Mezzaluna, it originated at Bourbon & Branch in San Francisco and uses Averna instead of sweet vermouth—a groundbreaking move when it was created in 2005.

2 ounces rye whiskey (we use Rittenhouse)

1 ounce Averna

3 dashes Angostura bitters

Add ingredients to a mixing glass with ice. Stir until well chilled. Strain into a Nick and Nora martini glass or coupe. Express an orange twist over the drink and discard. Garnish with a Luxardo maraschino cherry on a pick. Makes 1 drink.

This Negroni riff is a marriage of some of Verrall’s favorite flavors—smoke, bitterness, peppermint and coffee. It makes a perfect after-dinner tipple.

1 ounce mezcal (we use Ilegal Mezcal Joven)

1 ounce Campari

½ ounce Branca Menta

½ ounce Mr Black coffee liqueur

Add ingredients to a mixing glass with ice. Stir until well chilled. Strain into a double old fashioned glass over a large rock. (We get our ice from Revolution Craft Ice in Santa Cruz.)

Express an orange peel over the drink and discard. Garnish with a slice of dehydrated orange. Makes 1 drink.

Inspired by the modern classic cocktail, the Gold Rush, this is a tribute to the Gold Coast of California, where this amaro is made.

1 ounce bourbon (we use Michter’s)

1 ounce Amaro Angeleno

¾ ounce ginger turmeric-infused honey syrup (recipe on ediblemontereybay.com )

½ ounce fresh lemon juice

Add ingredients to shaker with ice. Shake until chilled. Double strain into a coupe glass and garnish with a dehydrated lemon wheel. Makes 1 drink.

Courtesy Francis Verrall, head bartender, Mezzaluna Pasteria & Mozzarella Bar in Pacific GroveThe amaro Fernet-Branca enjoys cult status among bartenders. “It’s like a brotherhood,” says Manny Hernández, bar manager at Barceloneta. “It’s a secret code.” Ordering a shot of Branca at the bar—nicknamed the “bartender’s handshake”—signals that you know life is bitter and better for it.

For Cameron Delgado and Georgette Flores, managers at 515 Kitchen & Cocktails, a Fernet shot symbolizes solidarity. “There’s ritual and camaraderie to a shot amongst friends,” explains Delgado, while Flores emphasizes Fernet-Branca’s unspoken bond between bartenders. “You can’t help but feel like those who request a round of Fernet know.”

The exact recipe for the potent potion remains a trade secret of 27 herbs and aromatics, but is said to likely contain aloe ferox, chamomile, gentian, myrrh, peppermint and saffron. (The distillery also makes a mintier and sweeter sister, Branca Menta.) Fernet-Branca has high alcohol, low sugar and, unlike most other amari, is aged in the barrel for a year. “I think it’s tasty, but it’s definitely not everyone’s preference,” says Jason Strich, bar director at Mentone.

So what’s the appeal of the bitingly bitter herbal liqueur? “We taste so many things throughout the night, making sure every cocktail is tasting right. We want to get hit in the face with flavor and bitterness,” muses Katie Blandin, owner of Pearl Hour. “And a lot of the herbs in amaro are stimulating.” Verrall agrees that a shot of Fernet-Branca energizes and rejuvenates. “It gives you a little oomph, a little boost, for sure.”

Shooting Fernet-Branca does upend tradition, which dictates amaro be slowly savored at the end of the evening. “Our Italian brethren think us Americans foolish to be slamming Fernet-Branca—though I have been known to indulge in this ritual on occasion,” says Anthony Vitacca, spiritsmith at Montrio Bistro.

But Fernet-Branca isn’t the only bitter beverage enjoyed behind the bar. Local bartenders reveal their favorite amari for sipping after their shifts.

Katie Blandin, Pearl Hour Liquore Delle Sirene Canto Amaro is my current favorite. It’s light and golden with Christmas spices like cinnamon and ginger. I really like it because it’s made by a woman. And it’s a beautiful amaro that caught my palate.

Jevana Bouquin Cynar 70 for 50/50 sipping preparations. I like mine with a sweet-leaning, cocktail-appropriate mezcal like Banhez Ensemble or Del Maguey VIDA.

Georgette Flores, 515 Kitchen & Cocktails When I first tried Amaro Montenegro, all the stars aligned for me. The velvety vanilla notes hit first, rolling out the red carpet for a whimsical transition into some beautiful citrus. It was a wonderful experience that I still haven’t forgotten.

Manny Hernández, Barceloneta I really love Fernet-Branca. It means friendship, like part of a celebration after a long shift.

Kelly Kuhn I really like Lucano.

Josh Perry, Carmel Valley Ranch I’d have to go with Amaro Montenegro.

Alice South, Hula’s Island Grill Amaro CioCiaro. It’s a great mild bitter amaro that’s great neat, and makes a killer Black Manhattan.

Jason Strich, Mentone My go-to amaro for sipping is Bràulio, sipped neat or with a little bit of mezcal in there as well.

Brandon Torres, Soif Restaurant + Wine Bar I would definitely go with Amaro Montenegro for my favorite. Italian-style amari are always more profound with flavor, and have higher notes of citrus and light elements that come together in cocktails.

Anthony Vitacca, Montrio Bistro My favorite amaro at the moment is Lo-Fi Gentian Amaro. It’s a lighter style amaro with cinchona bark, hibiscus, ginger, grapefruit, rosewood and orange peel.

James Wall, Alvarado Street Brewery & Grill One of my absolute favorites is Foro. I also like using Cardamaro and Cynar in cocktails.

Daniel Watson, Cantinetta Luca To drink straight, Meletti in a chilled whisky glass, twist of lemon and discard so you’re left with a lovely lemon aroma that doesn’t interfere with the amaro too much.

The Black Manhattan is made with Averna and rye.

It is no easy task to get everyone on the same page when it comes to making changes in organic agriculture. It has been a particularly trying experience for Dr. Lisa Bunin, who has spent the last seven years working to make sure organic strawberries are really organic—from the roots up.

Although consumers see certified organic strawberries for sale at the grocery store and in farmers’ markets, the truth is that the vast majority of them are grown from conventional, non-organic transplants, also called starts. These starts are grown in chemical-fumigated soil, and synthetic chemicals are also used for subsequent disease and pest control of the crop throughout the growing season, as they send out the shoots that will be sold as starts.

Most organic strawberry farmers have been buying non-organic starts simply because there are few alternatives. If organic starts are not commercially available—which they have not been in the amounts and varieties needed to supply all the certified organic strawberry farmers— then growers are allowed to use non-organic plants and still comply with the USDA’s National Organic Program.

The strawberry industry has long been grappling with the noxious chemicals traditionally used in growing, and Bunin knew that 1.3 million pounds of toxic and ozone-depleting pesticides could be eliminated each year if organic farmers would switch to using organic strawberry starts.

“If you care about how food is grown, these pesticides are bad for wildlife, for water, for the environment,” she says. “These are gnarly chemicals. They are not the ones you want in your community or near a school.”

The strawberry problem nagged at Bunin, who has spent decades diving into vital environmental issues, particularly around making ag-

riculture more eco-friendly.

While living in Europe, she worked for Greenpeace International and was inspired to study how industrial production systems impact humans and the environment. She served as a delegate to the United Nations’ London Convention on Marine Dumping, where she partnered with governments and non-governmental organizations to successfully stop the worldwide burning of toxic waste at sea.

In the late 1980s, Bunin was responsible for helping bring the first U.S.-grown organic cotton to market, an important step forward in shifting cotton production away from conventional practices. Locally, she was instrumental in securing Santa Cruz County’s moratorium on growing GMO crops in 2006, and she sits on the board of directors of the nonprofit educational organization, EcoFarm.

While policy director for the nonprofit Center for Food Safety, she focused on the organic strawberry dilemma and organized the Organic Strawberry Fields Forever project. Her goal: to wean organic growers off conventional transplants.

“I wanted to bring all stakeholders in the organic industry along,” says Bunin, which meant getting not only farmers on board, but also the nurseries that supply strawberry starts. “That way, there would be no going back once the organic strawberry industry started its transition.”