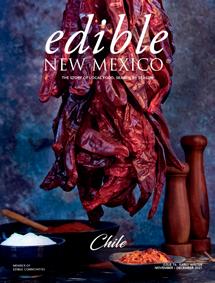

edible NEW MEXICO

THE STORY OF LOCAL FOOD, SEASON BY SEASON

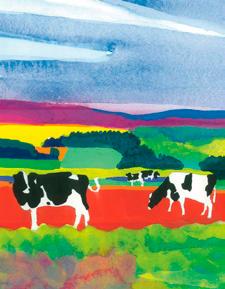

The year is 2023. The scene is territory known by many names, some of them closely guarded secrets. These lands have changed hands many times, and even today, disputes in ownership persist—not only in fact but in possibility. Like the Bedouin lands of North Africa, these deserts and dunes have stood in for distant planets, alien terrain. Less evident to outsiders is the remarkable biodiversity of these lands, and the tenacity of their inhabitants. Among them are many who believe the earth has a future.

The stories in this issue of edible New Mexico are no more science fiction than the view from your window, but, like the artwork of Indigenous Futurism, these are stories where time bends. They are stories where la milpa, as the practice of intercropping squash, beans, and corn is known in Mexico and Central America, is more than a historical practice. These stories of the Three Sisters—a term said to come from the Haudenosaunee people—are stories in the present tense, stories where the past refracts the future.

In these pages, Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers shares a love letter to beans that is also a song of praise for her centenarian grandfather, whose bean adventures have sustained him throughout his life. Cassidy Tawse-Garcia threads narratives of corn and place through the intimate ritual of a very contemporary cup of atole. And in exploring local stories of squash, leticia gonzales reflects on the ways human relationships—with food, and one another—transcend our lifetimes. This is true, as we learn from Moises Gonzales, of wild food gathering traditions too.

The practice of storytelling may seem anchored in the past, but, like planting trees and saving seeds, it is rooted in a commitment to the future. Perhaps nothing better illustrates this than our dispatch from Alexandria Bipatnath. Writing from the Navajo Nation, she introduces a Diné-owned company producing organic food for the little ones poised to inherit the world.

PUBLISHERS

Bite Size Media, LLC Stephanie and Walt Cameron

EDITOR

Briana Olson ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Space

COPY EDITORS

Marie Landau and Margaret Marti DESIGN AND LAYOUT Stephanie Cameron

PHOTO EDITOR Stephanie Cameron EVENT COORDINATOR Natalie Donnelly

VIDEO PRODUCER Walt Cameron

SALES AND MARKETING

Kate Collins, Melinda Esquibel, Gina Riccobono, and Karen Wine

PUBLISHING ASSISTANT Cristina Grumblatt

CONTACT US

Mailing Address: 3301-R Coors Boulevard NW #152, Albuquerque, NM 87120 info@ediblenm.com ediblenm.com

SUBSCRIBE ∙ LETTERS

EDIBLENM.COM

We welcome your letters. Write to us at the address above, or email us at INFO@EDIBLENM.COM

Susanna Space, Associate EditorBite Size Media, LLC publishes edible New Mexico six times a year. We distribute throughout New Mexico and nationally by subscription.

Subscriptions are $32 annually. Subscribe online at ediblenm.com/subscribe

No part of this publication may be used without the written permission of the publisher.

© 2023 All rights reserved.

Alexandria Bipatnath is Anishinaabe and Guyanese from Toronto, Canada. She is a clinical integrative nutritionist and chef who specializes in First Nation fusion foods. Bipatnath founded The Wholesome Conscious in 2018, which began as a catering company and now offers a wide variety of services.

Stephanie Cameron was raised in Albuquerque and earned a degree in fine arts at the University of New Mexico. Cameron is the art director, head photographer, recipe tester, marketing guru, publisher, and owner of edible New Mexico and The Bite.

Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers lives in Valencia County with her husband, Larry, and daughter, Tachi’Bah. She owns Silver Moon Studio in Bosque Farms.

leticia gonzales lives and works in Santa Fe.

Moises Gonzales is an associate professor of urban design at the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of New Mexico. He is the co-editor of the book Nación Genízara: Ethnogenesis, Place, and Identity in New Mexico (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). He is a danzante of the Matachín and Comanche traditions of the Sandia Mountain communities.

Briana Olson is a writer and the editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She lives in Albuquerque.

Susanna Space, a writer and twenty-year resident of Santa Fe, is the associate editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. When she’s not covering the local food scene, she writes essays about topics including animal rights, meteors, and the cultural history of the Southwest.

Cassidy A. Tawse-Garcia is a storyteller, cook, and PhD student in human-environment geography at the University of New Mexico. She lives in Albuquerque with her cat, Ham, and six chickens. She is the owner of Masa Madrina, a pop-up food project.

Marisa Thompson is New Mexico State University’s extension service urban horticulture specialist. In addition to landscape mulches and tomatoes, her research interests include abiotic plant stressors like wind, cold, heat, drought, and soil compaction. She writes a weekly gardening column, Southwest Yard & Garden, which is published in newspapers and magazines across the state. Readers can access the column archives and other hort-related resources at desertblooms.nmsu.edu. Find her on social media @NMdesertblooms.

An edible Local Hero is an exceptional individual, business, or organization making a positive impact on New Mexico's food systems. These honorees nurture our communities through food, service, and socially and environmentally sustainable business practices. Edible New Mexico readers nominate and vote for their favorite local chefs, growers, artisans, advocates, and other food professionals in two dozen categories. (Winners of the Olla and Spotlight Awards are nominated by readers and selected by the edible team.) In each issue of edible, we feature interviews with a handful of the winners, allowing us to get better acquainted with them and the important work they do. Please join us in thanking these Local Heroes for being at the forefront of New Mexico's local food movement.

Photos by Stephanie Cameron

Photos by Stephanie Cameron

Chef Ray Naranjo, a Native American with roots from both the ancient Puebloans of the Southwest and the Three Fire Tribes of the Great Lakes, believes in the preservation of the foodways and ancestral knowledge of his people and strives to continue on this path. With the use of modern and ancestral cooking techniques, he pushes the limits of what is known, unknown, and forgotten about the Indigenous food culture of North America. Chef Ray

earned a degree in culinary arts and has more than twenty-five years of experience in the modern restaurant industry, working in kitchens in exclusive hotel and casino resorts in the Southwest and wearing titles ranging from executive chef to food and beverage director. Chef Ray has also been presented with several awards in New Mexican cuisine, with a focus on the chiles of New Mexico.

Visit the new Farm Shop Norte for a unique Los Poblanos shopping experience in downtown Santa Fe. One block north of the Santa Fe Plaza, Farm Shop Norte is housed in a renovated 1935 gas station and farm supply store. This one-of-a-kind environment is a destination for shopping Los Poblanos’ signature lavender products, botanical gin, and Farm Foods, alongside curated objects for the home, and New Mexico wine and spirits. Adjacent, Bar Norte is an intimate space to enjoy a cocktail made with Los Poblanos Botanical Spirits and enjoy a light tasting menu. NOW OPEN 201 Washington Ave., Santa Fe | Tuesdays through Saturdays, 11am - 7pm | LOSPOBLANOS.COM

Farm Shop at Town & Ranch (downtown Albuquerque) 1318 4th Street NW

Farm Shop (Los Ranchos de Albuquerque) 4803 Rio Grande Boulevard NW

In the Tewa language, manko is the verb for “come and eat.”

The end product of what is Manko is a career of refining both street food as well as fine dining dishes that fuse the original ingredients of the Americas with modern technology and the cooking of the present. A reversal of colonization.

How has your food truck menu changed and developed over the course of your first year in business? Is there a particular dish that has especially resonated with customers?

Our menu has developed to meet high-pace needs as well as having enough diversity to please a crowd. Our green chile smashburger is made with free-range buffalo and wrapped in a tortilla. Our turkey sandwich is finished with cactus fruit syrup.

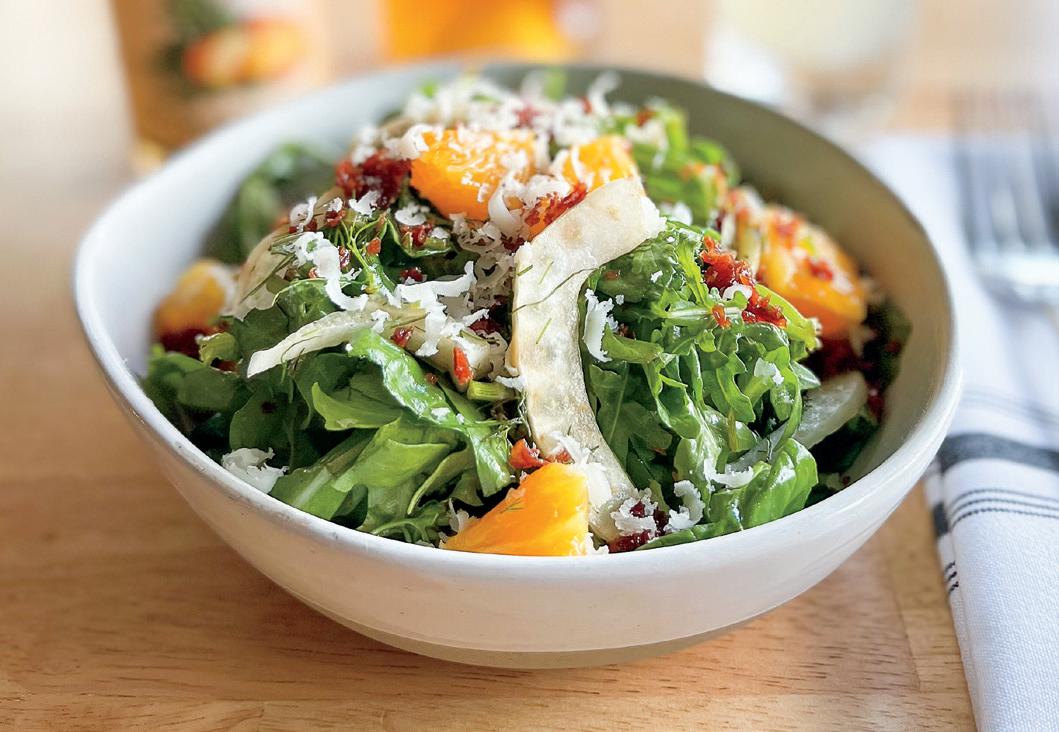

Our new salad is one of significance. Even the name is a hidden meaning—Berries Bird Seed Salad—Berries being the rez nickname for Manko co-owner Nathana Bird. This salad is also the missing link to connecting us to our past and connecting the food truck to my food journey as a chef. With ingredients like popped amaranth and popped quinoa, we can tell the story of our connections between the ancient world and today.

Top: Finishing a Cactus Tempura Turkey Sandwich with cactus fruit syrup. Bottom left: Ray Naranjo with his son Ethan Naranjo. Bottom right: Berries Bird Seed Salad.

We offer free-range bison products from Beck & Bulow and try our best to source the rest of our menu items locally.

You often collaborate with other chefs, whether at events catered by Manko or with the Intimate Indigenous Experiences you hosted while at Indian Pueblo Kitchen. Are there any upcoming collaborations readers should know about?

Collaborations for Native chefs are important to develop what is now surfacing as modern Native American cuisine, and foster healthy competition to challenge our creativity to push this cuisine as far as possible. We have an upcoming collaboration with Chef Crystal Wahpepeh of Wahpepah’s Kitchen in Oakland, California.

Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

Thanks for this awesome opportunity. Follow us on Instagram or Facebook to check in on our location, as we plan to do plenty of traveling in 2023.

instagram.com/chef_ray_naranjo

Twelve years living and working in Los Angeles. More than a decade in New York City. And a vacation in New Mexico! Kristina Hayden Bustamante says she knew after a few days that she’d be back. In that time, she has honed her love of wine and is now the wine director and

sommelier at The Compound, the only surviving Alexander Girard–designed restaurant anywhere and a keystone of Santa Fe’s Canyon Road. “I have always felt that it is a real honor to be included so intimately in my guests’ dining experience.” In her parallel world, “On my

days off,” she says, “I am absolutely obsessed with tea. I have been for many years and have toyed with the idea of studying it in depth.”

What is your philosophy around pairing wine with food, and how does that apply at The Compound?

I wholeheartedly believe that the successful pairing of food and wine can elevate the dining experience to an entirely different level. Our menu changes seasonally and I am always looking for new and unusual wines to complement the menu. If a guest wants the full wine pairing experience, I am prepared to give that to them, but ultimately I believe in drinking what you will most enjoy. It is my job to ask the relevant questions and determine what the guest is looking for.

Would you describe your approach in your selections as more instinctual or more intellectual? More art or science?

All of the above. I am fortunate to have a talent for analyzing and assessing wines not only for quality but for maximum enjoyability, and a big part of it is purely instinctual to me. That being said, there is a never-ending pursuit of information and exploration that comes with my job. I create and build a wine list as if I am writing down a story that I am trying to tell; it needs to be told seamlessly and without any plot holes. I have also done this for quite a while, and with age comes experience. I have been given the opportunity to taste a lot of wine in my day, and each great wine comes with a memory to be reexamined and reflected on. I suppose they are each like a piece of art.

Before coming to Santa Fe, you were a sommelier in Southern California. How is New Mexico wine culture different? What’s special about doing what you do in New Mexico?

I would say that there is very little difference. So many of our guests, both local and from out of town, come with a very sophisticated appreciation of wine. They are well traveled and incredibly adven-

turous. I am also seeing a real demand for natural or biodynamically farmed wines. This is great and it keeps me on my toes. New Mexico makes some pretty stellar wines and has for a long while, and I have made a point of trying to schedule some trips to local wineries so I can really understand what is happening here. I would love to start a local wine section on our list and am really taking the time to explore so I can introduce them to my guests with the care that they deserve. The Compound is an institution in Santa Fe. What’s it like to play such an important role in the experience of those who dine there? How do you balance the preferences of your longtime customers with people newer to the city?

Santa Fe is a special place and I cherish my longtime regular guests. Many have been coming to The Compound for decades. One of the most awesome things, though, about being back in New Mexico is seeing a subtle shift in our guest demographic. I am sure that most people have noticed the influx of young people who have come to Santa Fe during the pandemic. These new guests have changed the way our dining room looks on any given night and they have become our friends and neighbors. Sometimes they come in for the architecture and the art by Alexander Girard, but they always return for the exceptional food and the warmth they receive when they are dining here. Santa Fe is definitely having a moment and I hope that it continues. New Mexico is irresistible!

When it comes to wine, do you have a current personal favorite among vintners or regions?

As far as having a favorite vintner or region, not really. I try not to drink the same thing more than a few times, no matter how much I may love it. I would be seriously behind the eight ball if I didn’t push myself to constantly try new things and explore more obscure regions and winemakers. I am crazy about Corsica right now.

La Montañita Co-op–Nob Hill & Rio Grande

Lowe’s Market on Lomas

Moses Kountry Natural Foods Silver Street Market

Triangle Market in Sandia Crest Lovelace Main Hospital Heart Hospital of New Mexico Sandia National Labs

UPC at UNM

UNM Hospital in La Cocina Cafeteria

Presbyterian Rust Hospital - Rio Rancho INTEL

Nusenda Corporate Office

Presbyterian Cooper Center

UNM Campus - Mercado, SRC, Cafe Lobo

SANTA FE

La Montañita Co-op Kaunes Market

Eldorado Supermart at the Agora Christus St Vincent Hospital Pojoaque SuperMarket

LOS ALAMOS

Los Alamos Cooperative Market

Los Alamos National Laboratory

ESPAÑOLA

Center Market

Presbyterian Hospital TAOS

Cid’s Market

GALLUP

La Montañita Co-op SOCORRO

NMTECH - Fire and Ice Cafe

by Stephanie Cameron

by Stephanie Cameron

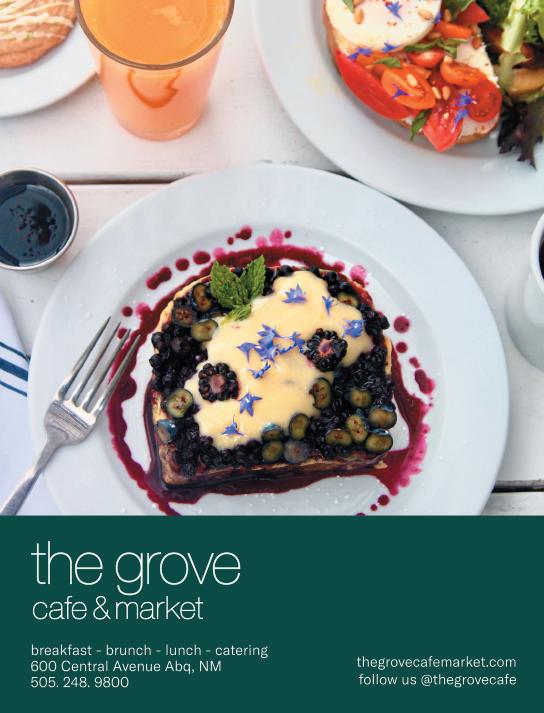

“When I began daydreaming of a coffee shop, I was longing for a place where we could meet up with friends, neighbors, coworkers throughout the day—a place that wasn’t work or home, where I could gain a greater sense of community,” says Pilar Westell, owner of Zendo Coffee in downtown Albuquerque. Established in 2013, Zendo provides expertly crafted coffee and showcases the finest food venues from across the city in its burritos and sweet treat offerings. Zendo also provides a platform for local talent in its rotating monthly

art shows. Now, as from the start, “Our passion is providing a space for people to get to know one another and to enjoy the many nuances of coffee in a warm and welcoming place,” Westell says.

Describe the process of creating a perfect coffee drink, from bean to glass.

In creating the perfect coffee drink, there are quite a few essential elements. Perfectly roasted beans are a must-have. High-quality filtered

water, dialed-in espresso, and steamed milk all combine to make a perfect coffee drink.

Your menu also includes quite a few tea drinks and other elixirs. What’s your favorite warm non-coffee beverage?

We have many teas, both caffeinated and caffeine free, on our menu. One of our favorites is our Golden Milk, a turmeric-andginger-based drink that is blended with honey and any milk or nonmilk option and topped with local bee pollen. It’s great for inflammation and keeping your immune system strong.

What went into building community and creating the gathering space that is Zendo?

My vision for Zendo has always been based on getting everyone together to really get to know one another. Because we live in such a digitalized world, I felt like something was missing. The concept of the third space—one that is different from home or work—was very important to me. And I felt like we needed more of that in downtown Albuquerque. A place where you could go and always run into an old friend, or meet someone new and be able to feel like a part of something bigger. A community. And that is exactly what has happened at Zendo. People meet each other, work together, and support one another, all while getting to drink the most delicious coffee in town. What does it take to be an incredible barista? In times like these, how do you maintain a loyal, capable staff?

I have the most incredible staff. They are why Zendo is such a success. They care deeply about providing quality drinks, while at the same time holding space for each and every person who walks in the door. We try to provide the kind of experience where each and every person who comes for coffee gets an experience that carries them throughout

the rest of their day. We are dedicated as a crew to providing the utmost hospitality while fostering a never-ending sense of community. And everyone on our small team brings something special to the table. Collectively, we are always trying to elevate what we are doing with coffee. But most importantly, I think each one of the folks working at Zendo is dedicated to making our customers feel welcome, seen, and important to the community at large. Everyone works well together, is invested in each other’s success, and is incredibly supportive of one another. That’s the most important part of being here. I’m constantly humbled by all the people I work with. We show up and work hard but also take care of one another. Zendo is such a success because I have the best staff around.

How do you decide which artist(s) to feature?

We feature a new local artist every single month. Our space lends itself to showing art really well because of our white brick walls and all the natural light. The best part is we have such a diverse clientele that people from all walks of life get to enjoy the art, and the art gets to be shown to many different people from all over. Currently, we accept digital submissions for shows and then work on hanging things that we feel align well with our space and vision.

Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

We are incredibly humbled by the support everyone has given us over the years and just want everyone to know how proud we are of how we have grown. We couldn’t be where we are today without such amazing community support.

413 Second Street SW, Albuquerque, 505-926-1636, zendocoffee.com

“Community to us is everybody,” says John Haas, whose passion for food led him to serve as M’tucci’s executive chef for nine years. Now a partner and the company’s president, he is driven by seeing the success of others around him. Haas is most proud of the amazing talent that M’tucci’s calls its work family. His goal with food is to create approachable and familiar dishes built around clean, vibrant, seasonal flavors. Many of the dishes are inspired by his time with Italian-born chefs in the Midwest and Italy, as well as creative interpretations of classic dishes and flavor profiles.

Why Italian? And for someone considering their first meal at any M’tucci’s location, what distinguishes each of your four restaurants?

Italian is something that Jeff Spiegel, M’tucci’s cofounder, felt there was an opportunity for in Albuquerque. I had spent most of the previous ten years preparing Italian cuisine, which made it something that we could quickly agree on. We also believe strongly in the community table and how meals can bring people together. In our minds, few cultures represent that better than Italian culture.

Each location has its own unique identity built around the community that surrounds it. However, there are noticeable common threads. Our “welcome home” style of service, the local neighborhood feel in our bars, and the fact that 25 to 33 percent of the menu can be experienced at every location. It’s fun to look back and see the progression of our company from the first location (M’tucci’s Italian) to our newest (M’tucci’s Bar Roma).

Talk about your salumi and sausages. What is their role on your menus? How do you decide when to use M’tucci’s house-cured meats and when to source from Italy or elsewhere?

From day one, we have worked hard to develop a food program where we can basically say “if you ate it here, we made it here.” However, there are exceptions where we don’t feel we’ve perfected some recipes and we must make the decision to either source it or exclude it from our menu. Our goal is to make everything in-house, but not at the price of serving a subpar product. With these old-world techniques, especially salumi, it can take months or years for us to perfect. It’s in those moments that we will source something until we think we’ve created a superior product.

To take it in the other direction, what is one of your favorite vegetarian dishes? What’s key to building texture and flavor without meat? Dare to offer any opinions on “meat analogues,” a.k.a. fake meat?

If I’m choosing from our menu, it’s undoubtedly eggplant parmesan. I think it’s such a comforting dish and I think the version we serve is just exceptional. I don’t feel there’s really a different approach to vegetarian food. All food is built around a basic premise for me: layered flavors, vibrant and distinguishable flavor profiles, texture, a balance of sweetness and acidity, technical execution, and some degree of approachability.

As far as “meat analogues,” and this may not be the most popular answer, but there is little interest in them among our chef team. We believe in bringing in foods that aren’t processed or preprepared, and it’s safe to say that developing our own versions [of meat analogues] has never been discussed. We’d rather focus on how to balance a dish with the raw ingredients we work with than change our approach to our culinary identity.

Do you have a favorite aromatic? Where do you source it?

Good question. As simple as I like to keep things in life, there is never a simple answer for me; I don’t have a favorite aromatic, but I have favorite combinations of aromatics. Many of them don’t make their way into our restaurants because they don’t fit along the lines of Italian cuisine. One of my favorite more common combinations is garlic, anchovy, olive oil, and tomato.

How do you balance managing night after night of service with cultivating new ideas and growth among your team? Did you start with a vision of giving ownership to motivated staff members, or did that develop over time?

I don’t think it’s so much about balancing it all because it’s not really a balancing act when it’s so intertwined with your approach toward people. If you’re fully committed to the growth of your team, I believe you will discuss and involve them in the process of cultivating new ideas so they can start to align themselves with your thought process. It was always part of our plan and something Jeff and I were in complete agreement on. The value of having a core group of partners who are career focused and committed to the same goal is immeasurable. It was something we felt was instrumental to achieving our longterm vision. I think it’s also important to point out the big difference between giving and earning. Every partner in our company has gone above and beyond the highest expectations to earn their ownership.

Funnily enough, this is a current hot-button topic for us. In the past, probably too many people. In the near future, a very select few (who will remain anonymous for their own protection) will build the playlists.

Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

If you love our restaurants, you should reach out to us about catering. It’s one of M’tucci’s largest focuses going into 2023 and, secretly, probably one of the things we are most exceptional at. We really just love to throw a party, whether it’s in our restaurant or at the place of your choice.

Multiple locations in Albuquerque, mtuccis.com

What’s your favorite tree?

Is it the magnolia you napped under on a hot summer day on vacation in Madrid? Is it the live oak that Edgar Allen Poe wrote about while stationed in your hometown? Or the shrubby fig tree outside your grandmother’s kitchen window? Is it the one that creates your favorite flower, or the one that harbors your favorite birds? Or is it the one currently shading your car in the driveway? Perhaps you have a favorite species of tree, like the cottonwoods in the Rio Grande bosque or the bigtooth maples in the Manzano Mountains.

My answer is a resounding “yes” to all of these.

But selecting a tree for your yard now is about finding your future favorite tree, not replicating a favorite from the past. You’ll never fall in love and grow old

together if your new tree isn’t healthy. And it will thrive into maturity only if it is well suited to your landscape conditions.

Cold hardiness, heat hardiness, drought tolerance, and size are all primary considerations when drafting a wish list and strategizing care in the long term. And the long term is what we’re growing for—not only for our future selves but so that the next resident inherits a healthy tree they can maintain, one that might even become their kid’s childhood favorite.

(Sidenote spoiler alert for those seeking a fast-growing tree: very generally, trees that grow fast die young. With so much energy spent on aboveground growth, less is spent on healthy roots, sturdy limbs, or a strong immune system.)

In terms of tree requirements, cold hardiness may be the most straightforward. Just about every landscape plant species and variety has an established USDA plant hardiness rating that is readily googleable, if not listed on the nursery tag. To find the USDA plant hardiness zone for your area, visit planthardiness.ars.usda.gov. If the tree you’re considering is cold hardy down to the same zone in your yard or lower, you can rest assured that the likeliness of a frosty death is extremely low. So a bigtooth maple (Acer grandidentatum), cold hardy down to zone 4, will be just fine after a rough January in the City Different. But blue palo verde (Parkinsonia florida) is documented to be cold hardy only down to zone 8 (10°F to 20°F), so this tree that’s common in Tucson and becoming more common in El Paso is not expected to withstand the cold temperatures experienced in an average Santa Fe winter.

Heat hardiness isn’t quite as clear, but has become extremely important. By 2050 (less than thirty years away!), high temperatures in the Albuquerque area are expected to resemble the current highs in Las Cruces or El Paso, and by the end of the century (less than eighty years away), they’ll be closer to the highs currently experienced in Tucson. For trees and other perennial plants to live and thrive as long as possible, we need to consider how cold hardy they are this decade and how heat hardy they will be in the warmer decades to come. Handily, two recent reports created by folks at The Nature Conservancy, New Mexico State Forestry, and a host of other local collaborators dig into recommended climate-ready trees for the Albuquerque area and the five climate zones of New Mexico (both reports can be found on the Tree New Mexico website, treenm.org/ partners-and-resources/some-recommended-trees-for-planting).

Now let’s touch on the question of size. “Right tree, right place” is not just a mantra of arborists worldwide—it is the mantra. Considering how big a tree will be at maturity is crucial. The bigger the tree,

the bigger the necessary canopy and rooting area. Without sufficient lateral root room, trees become stressed. With stress comes a compromised immune system and a higher susceptibility to all sorts of insect and disease pressures.

On top of size, space, and hardiness, when people ask me, “What’s the best tree for my yard?” the following questions jump to mind.

How do you plan to water the area surrounding this new tree? Unfortunately, in our warming world and lasting drought, even desert plants native to our region require supplemental irrigation as they become established, and thereafter. So a watering method and plan are a must. This doesn’t have to be a fancy irrigation system; irrigating the entire root area and beyond can be done with a garden hose or even a five-gallon bucket. If you have both, drill small holes in the bottom of the bucket so that water dribbles out slowly after being filled, then move the bucket a few times around the tree canopy dripline to be sure the roots are saturated in all directions. As a general rule, water to a depth of about two feet and allow the soil to dry out between soaks so roots have access to oxygen. A thick layer of plant-based mulch will help maintain soil moisture levels. A minimum mulch depth of four inches is also optimal for the control of many annual weeds in the soil seed bank.

How attached are you to only planting a tree? Even if your niche is small, a cluster of smaller or medium-sized plants offers diversity, both aesthetically and ecologically. Instead of a huge single tree, consider a small climate-ready tree, a compact shrub, three small ornamental grasses, and a few perennial flowers, all grouped together.

How often do you walk by? And who else might enjoy it?

Dramatic fall foliage displays make the Texas red oak (Quercus buckleyi) and Chinese pistache (Pistacia chinensis) great showpiece trees when placed in highly visible areas, seen from inside your home or out. If this is a spot you and your family pass frequently or will sit under, consider something that attracts hummingbirds, like a desert willow (Chilopsis linearis). Female New Mexico olive trees (Forestiera neomexicana) provide berries for backyard birds, and the bright yellow fall color is beautiful too. Speaking of color, in early spring, when most of the other trees are still dormant, the pinky-purple flowers of redbuds (Cercis species) are extraordinary. If you plant one that’s visible to neighbors, be sure to remember the variety, because they will want to know.

Which native plants could you incorporate into this area? Native species offer a wealth of ecosystem services for beneficial insects, birds, and other fun wildlife. Resources abound. The Native Plant Society of New Mexico website (npsnm.org) offers helpful lists with plant descriptions and tips for urban landscapes. The New Mexico State University Extension publication Perennial Plants for Pollinators (pubs.nmsu.edu/_h/H182.pdf) suggests flowering plants that attract native bees. And Valle de Oro’s ABQ Backyard Refuge Program offers ideas for native trees as well as other plants.

How long have you lived there? It wasn’t until after six months at my new house, when the windy season hit, that my front entryway became a gathering spot for leaf litter and random lightweight trash, mostly Doritos and Funyuns bags. My point is that it’s good to get to know your space and how you want to use it before making decisions you might regret. If I had planted roses by my front door, like I originally planned, I’d be quarreling with thorny stems each time I tried to clean up.

Do you need this tree to provide shade? And, if so, do you have enough room? Remember the arborists’ mantra? In a smaller space, you might be better off with a shade structure adorned with beautiful climbing vines. Of course, growing trees for shade is worth the time it takes to get there. But in a restricted area, there’s not enough rooting space to support a large shade tree. And remember what stress from root restrictions invites? Secondary problems like pests and diseases.

Deciding on the tree species is the big first step toward a long, lasting friendship. The next steps include choosing healthy specimens at a nursery, avoiding common planting mistakes and soil problems, and strategizing care. Find links to all of these topics by searching my blog for the word edible (nmsudesertblooms.blogspot.com).

You’re not alone on this landscaping journey. Reach out to local experts if you need help along the way.

I wonder what my new favorite tree will be. As author Lorene Edwards Forkner said, “Planting trees means you believe in tomorrow.”

Afganski pomegranate in Los Lunas.

NMSU Extension Publication: Trees and Shrubs for Beneficial Insects in Central New Mexico, Guide H-177, pubs.nmsu.edu/_h/H177.pdf

505 Outside by Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority: 505outside.com

Valle de Oro’s ABQ Backyard Refuge Program: friendsofvalledeoro.org/abq-backyard-refuge

Santa Fe Native Plant Project: sfemg.org/santa-fe-native-plant-project

NMSU Extension Master Gardener County Chapters: mastergardeners.nmsu.edu/chapters.html

Check out your local botanical gardens, nurseries, and garden centers too!

Keep in mind that every plant list has some drawbacks or, at least, constraints. Long lists can be cumbersome, but short lists often limit species diversity, which is important for healthy ecosystems. And, sadly, few lists give priority to native species. Whittle down a shorter wish list of your own—one that includes native species cross-referenced on multiple local resource lists.

With my background in culinary arts and nutrition, I was instantly intrigued by the idea of a Navajo-owned family business in Shiprock, producing organic neeshjhizhii (steamed dried corn) from Navajo white corn—for babies! Bidii Baby Foods specializes in creating greater access to traditional foods in the early childhood years. This baby food company can be enjoyed by the whole family, with their finely ground corn being a staple breakfast food.

Zachariah Ben, a sixth-generation Diné farmer, and his wife, Mary Ben, a first-generation American from Hungary, founded Bidii Baby Foods in 2021. Their farming journey began on fields that hadn’t been farmed for more than twenty-five years, where Zachariah and Mary began implementing traditional Diné farming practices. Without the use of pesticides or insecticides, their crop is completely organic. Once harvested, the corn is placed in an underground oven,

where it is pressure- and steam-cooked for twelve hours. Once it’s taken out, it’s dehydrated and shelled; some is kept whole and some is finely ground. When it’s ready to be eaten, the finely ground corn is rehydrated with water or milk, while the whole-kernel corn can be added into soups and stews, paired with mutton, bison, or beef— staple foods for the Navajo people.

After hearing Zachariah explain both their harvesting and preparation processes, I was even more excited to sample their cereal, which is prepared by boiling with water or milk at a 1:4 ratio, much as oatmeal is prepared. My tastebuds were jumping with joy when I had a spoonful of their Neeshjhizhii Doo Nayizi Bi’taa’Niił (Navajo dried steamed corn and squash cereal) last November. With its smoky and nutty aromatic notes, I caught myself fondly recalling childhood memories of being elated with a cob of corn in hand. Bidii Baby Foods is an

agriculture cooperative incorporated and registered with the Navajo Nation. “This was the example [of forming a cooperative] that we wanted to set,” said Zachariah.

It all started when Mary met Zachariah on another farm in Shiprock, where the two later had their son. Bidii Baby Foods was conceived with the goal to provide highly nutritious and accessible food not only for their son but on the Navajo Nation as well.

“It was our son’s first taste of that food that put away all worries,” Zachariah said. “It instilled in us the power of parenting to say that we’re on the right course and this is the course we want to take. These are the types of resources we want for the rest of our families. When we fed it to our son, he loved it! He was taking in all that time and effort that we put into the field. Going out there and irrigating and triumphing [on] hot days. All the discipline and love that is implemented into the seeds, to where and how you grow, just nurturing, caring, and loving that farm is what your child is tasting during harvest season. That’s the type of food we need, especially nowadays.”

Zachariah shared that their business approach isn’t for capitalistic gain but rather to share their personal story and how it has nourished their son’s mind, body, and spirit. “He doesn’t crave processed foods. He craves steamed corn. That’s the type of reaction we want from the rest of our community, [and we thought,] why don’t we make that available, and it just snowballed from there.” Bidii Baby Foods, which can be ordered online, has seasonal blends with other traditional ingredients mixed into their finely ground steamed corn cereals, such as amaranth and squash, all grown organically on Zachariah and Mary’s farming plots. They also have bison jerky sourced from the Brownotter Buffalo Ranch, a Native American–owned and –operated company in South Dakota—a tasty snack for the whole family to enjoy.

It’s “40 percent non-Native, 60 percent Indigenous,” Zachariah said enthusiastically when I asked what their customer demographics look like. “Everybody loves it. They love the growing practices and methods we implement into it.” I began thinking about my own community, the Anishinaabe Ojibwe peoples, and manoomin—one of our people’s first foods, also known as wild rice—and how it’s the first food you eat as an infant and the last food consumed just before you pass. I asked Zachariah if the Diné people have a similar type of ritual with eating food in this way. Smiling, he began sharing about the Diné Yébîchai ceremonies. “In [this] ceremony, we have twenty-four different foods, from wild spinach, carrots, onions, [and] parsley [to] corn of all colors. They’re cooked in different ways—from a tamale to a kneel-down bread, or pureed down. You take it in small portions, and you communally share that with the others who are participating. The medicine man sings to awaken the masks and [they] are fed those first foods to begin the ceremony,” said Zachariah. “This is what we’ve started to do with our son. Showing him those first foods by going out to forage and to see what type of seasons and elevations they grow in. He’s so small but he understands, and he’ll let you know he understands because he partakes in those activities. And that’s the type of relationship that we have and what we want to share. It starts with the farm because that’s the foundation for life.”

The Bidii Baby Foods farm has been a place of healing, education, and knowledge sharing, not only within Zachariah’s family but with and for the community at large. I’m looking forward to visiting the farm to help them plant in spring, and I encourage both our Indigenous and nonIndigenous community members to volunteer at the farm during their planting, growing, and harvesting seasons, supporting their incredible efforts in making traditional foods more accessible.

@bidiibabyfoods, bidiibabyfoods.org

Today local salt is not sold commercially or even at local farmers markets, but my annual trips to gather native salt have become an important cultural practice. It’s one of the many wild food harvesting traditions without which New Mexican cuisine would taste less vibrant. Some of the most common local wild food favorites that come to mind are quelites (wild spinach) and asparago (wild asparagus), which grow along acequias throughout New Mexico and have

long been harvested by the Pueblo, Genízaro, and Hispano communities. I have been fortunate to live in the village of Carnuel, located in the Cañon de Carnue Land Grant, also known as Tijeras Canyon, where my family has been for centuries. Growing up, I was fortunate to be exposed to the food gathering practices of my Genízaro community—practices that were influenced by our Apache ancestors who have occupied these lands for generations, and also by geography.

Beginning in the eighteenth century, Genízaro settlements were established by the Spanish to provide defensible communities on the frontier of New Spain. The strategic planning of these new towns located them on the high-mountain borderlands between the Pueblo and Hispano settlements along the Middle Rio Grande Valley and the Ute, Diné, Apache, and Comanche territories. They were vital to the ability of the Spanish to sustain a presence in what is now New Mexico. The term Genízaro designated North American Indians of mixed tribal derivation living in servitude, who could earn their freedom (and acquire land) by participating in the formation of communities such as Abiquiu, Carnue(l), Ranchos de Taos, Truchas, Trampas, Las Huertas (Placitas), and San Miguel del Vado on the Pecos. In my village of Carnuel, it is certain that N’de Apache food gathering practices influenced east Sandia wild food harvesting practices because access to irrigation was very limited.

As a child, I heard stories from my grandfather about the annual trips for salt gathering that took place near the historic Salinas Pueblo Missions east of Quarai and Abo. Salt has been a fundamental food source since the beginning of human settlement, and for centuries Pueblo communities have harvested salt at Zuni Salt Lake, along the Canadian River basin of northeastern New Mexico, and at the Salinas Basin. I was taught that among the Genízaro communities, sometimes known as comancheros, salt gathered from the Salinas was not only used for flavor and food preparation but also for trade and preservation of game. Historically, men from the Sandia Mountain villages would leave on the buffalo hunts in late September and not return until around Christmastime. While on the plains, they used salt to preserve meat as well as to cure buffalo hides for clothing. The Genízaro communities also traded large quantities of salt with the Comanche. Salt was so valuable that the Comanche traded it for cap-

tive children and women, who were then sold and traded in the slave markets of New Mexico. Today local salt has lost its market value, but its nuanced flavor can’t be matched even by the higher-quality commercial culinary salts.

Tijeras Canyon, known as Cañon de Carnue before the arrival of the Americans, has been home to a Tiwa Pueblo, Faraon Apaches, and later the Genízaro land grant community, all of whom have utilized edible plant gathering practices. Carnue derives from the Tiwa word carna, which means “badger place,” and the cañon is host to a wide range of wild edible plants. Of all the communities who have lived here, the N’de Apache were probably the most dependent on edible plant gathering, which helped them to evade capture by the US government. They gathered the well-known piñon, along with nopal, tuna de nopal, verdolagas, cholla cactus buds and blossoms, capulin (wild chokecherry), and cota. The flavors contained in these edible plants can accent and complement common local recipes.

So how do these gathered foods come together in recipes?

Today it’s rare to see a nopal tortilla or a blue corn–nopal tortilla served in a local restaurant; however, this was commonplace in Genízaro or Apache communities. Still common in parts of Mexico today, nopales, roasted, dried, and ground into a masa, can be an excellent alternative to the traditional corn tortilla. Mixed with blue cornmeal, this provides a whole new range of possibilities. During the monsoon season, the Sandia foothills offer endless opportunities to harvest one of the best-tasting microgreens known to the human palate: verdolagas, or wild purslane. Rich in minerals and Omega-3 fatty acids, verdolagas adds a richness to salads in addition to traditional dishes. Dried and preserved in canning jars, it can be added as an herb to beans and posole, bringing a nuanced flavor that I can’t imagine beans being without.

Prickly pear is another local food that is slowly making its way back into New Mexican cooking. Harvested wild in early fall, prickly pear, made into juices, jams, wine, and syrup, provides a wide range of new possibilities and compositions. My go-to after a newly gathered harvest of prickly pear is to top off my blue corn atole with roasted piñon nuts and prickly pear syrup. Cholla buds and blossoms, which can be gathered in late spring, are another local favorite. Steamed or baked, the buds taste like asparagus and artichoke hearts. It’s remarkable that this plant has been forgotten as an edible delicacy in the Southwest. Fresh cholla blossoms are a delicate and delicious addition to green salads as well as sautéed vegetable dishes. Cota, also called Indian tea, grows in front of my home in Carnuel and is one of my favorite summer teas. This drink is still seen at many homes during feast day meals at local Pueblos.

Edible food gathering practices in New Mexico have begun to gain more visibility with the growing movement to decolonize food. The importance of understanding traditional edible food gathering practices is to recognize the contribution of Indigenous peoples to local food traditions—and to recognize the nuanced flavors and the wonderful knowledge embedded in these gathered foods.

I make my annual pilgrimage to gather local salt in the spring. The salt I gather is used for my own cooking and traded among some of my Pueblo friends for traditional varieties of beans, squash, and cornmeal. For me, the way local salt enhances New Mexico cuisine is unsurpassed.

And I can’t imagine a holiday meal without a gifted bottle of homemade capulin wine—made from chokecherries harvested right in my mountain community.

By tapping into Indigenous food groups and local, traditional farming practices and diversifying our diets, we’re not just enabling a healthier lifestyle that is sustainable, but we’re also reclaiming a food system that is holistic, ethical, and that is restorative to the planet.

—Louise Mabulo, Founder of The Cacao Project and UN Young ChampionTaking inspiration from YouTuber Christina Ng, a.k.a. East Meets Kitchen, I wanted this edition of Cooking Fresh to reflect an awareness of the Native ingredients I have chosen to highlight—the Three Sisters—corn, squash, and beans. In her video series Native American Recipes, Ng honors the recipes she shares by learning the history of the ingredients to better understand the food she is making. I took the same approach, combing the internet and diving into some beautiful cookbooks by Sean Sherman, Lois Ellen Frank, Roxanne Swentzell, and Freddie Bitsoie to foster an appreciation and knowledge of traditional Native foods. They are among the many Native American chefs working to reclaim their cuisines—and sometimes to reinvent them. While many Native American dishes have been absorbed into what we see today as American cuisine, environmental scientist Mariah Gladstone of Indigikitchen reminds us that Native foods aren’t only a part of the past but an essential and exciting aspect of the future.

There are many variations of the following recipes, each with adjustments to ingredients available in a given tribal region, often passed down for generations by Native ancestors. I don’t take credit for any of these recipes; I found versions that appealed to my palate, and tested, tasted, and adapted them for ingredients I could find in New Mexico during the winter. Each dish has seasonal possibilities. From summer squash to winter squash and fresh corn off the cob to dried hominy and chicos, there are many ways to make these dishes throughout the year, but all are rooted in the Three Sisters. While these ingredients and these dishes have limitless possibilities, and rising Native chefs fuse culinary traditions as often as all chefs, I wanted to select recipes that profile these staples that have so deeply shaped what we see today as New Mexican cuisine. I also committed, as much as possible, to making these recipes without colonial ingredients: wheat flour, dairy, cane sugar, or products from domesticated animals.

These basic formulas are simple recipes for completing the more complex recipes that follow. All of them can stand on their own or be added as side dishes to a meal. Making a pot of beans on Sunday that can be used in a variety of ways is a great jump on meal prep for the week.

Cook 2 cups (1 pound) of beans (pinto, Anasazi, or bolita) in 6 cups of water on the high setting of a slow cooker for 6–8 hours. Salt, to taste. Alternatively, beans can be simmered on the stove top for 6–8 hours if soaked overnight

beforehand. If cooking tepary beans, reduce cooking time to 1 1/2–2 hours.

Note: You can substitute canned beans instead of homecooked beans in most recipes, but home-cooked beans will always have better texture and flavor. Dried beans should always be cooked within a year, for freshness.

THE MATH:

• 1 (15-ounce) can of beans = 1 1/2 cups of cooked beans

• 1 cup dry beans = 3 cups of cooked beans, drained

• 1 pound of dry beans = 6 cups of cooked beans, drained

Makes 3 cups

Cook 1 cup of chicos in 6 cups of water for 6–8 hours in a slow cooker. Salt, to taste.

Makes 2 cups

Mix 1/2 cup roasted blue corn flour or blue cornmeal and 1 teaspoon juniper ash together with a whisk until evenly distributed. Set aside. Place 2 cups of cold water in a pot and add the flour mixture before placing the pot on the stovetop, whisking together until smooth. Cook over medium heat until sputtering begins, and then turn to low heat; keep stirring continuously for about 10–15 minutes as the mush thickens up. Serve with fresh or dried berries, seeds, nuts, and/or maple syrup.

Makes 4–6 cups

Don’t toss your corncobs! Put them in a freezer bag until you are ready to make corn stock. Place 6 corncobs in a large pot and cover with water by 1 inch. Bring to a boil and then turn the heat down to simmer. Partially cover and let the stock reduce until it tastes like corn, about 1 hour. Discard the cobs and store the corn stock in an airtight container in the refrigerator or freezer.

Coat the bottom of a skillet with sunflower oil, heat until shimmering, then add sage or oregano leaves in a single layer. Watch them closely—it only takes about 30 seconds or so for them to crisp up—then remove them with a slotted spoon. Put them on a plate lined with paper towels, then transfer to a serving plate. Sprinkle immediately with salt, to taste.

Many recipes use bacon or ham hocks to flavor their beans, but sticking with the basic bean recipe, we impart smokiness with the chicos and some fat with the bison tallow, and then we add the spice of chile—a match made in heaven.

2 tablespoons bison tallow (or sunflower oil)

1 small sweet onion, diced

1 tablespoon red chile powder

3–4 cups cooked beans (see recipe, page 41)

2 cups cooked chicos (see recipe above)

1 1/4 cup vegetable broth (this can be liquid from cooking the beans, or broth)

Salt and pepper, to taste

Add bison tallow to dutch oven over medium heat. Add onion and cook until caramelized, about 10 minutes. Stir in the chile powder to the onions and continue to cook for 2 minutes.

Add broth slowly to deglaze the bottom of the pot. Place cooked beans and cooked chicos into the pot and simmer for 15 minutes—season with salt and pepper, to taste.

Roasted squash seeds are great for eating by the handful and are perfect toppings for salads, soups, or roasted squash.

1 cup squash seeds (any winter squash variety)

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon melted bison tallow (or sunflower oil)

Separate seeds from the stringy flesh, rinse them thoroughly in a colander, and pick away any excess flesh clinging to the seeds. Spread the seeds in an even layer on paper towels and allow them to dry completely—30 minutes to several hours. Dry seeds roast better.*

Preheat oven to 275°F. In a bowl, toss seeds with bison tallow and salt. Place seeds on a parchment-lined baking sheet. Bake until the seeds turn golden, about 15–20 minutes. Wait at least 5 minutes for the seeds to cool; they get crispier the longer they cool. Store in an airtight container at room temperature.

*Note: After seeds dry, they can be stored in an airtight container until enough are collected for cooking.

First developed in Mesoamerica over three thousand years ago, nixtamalization is a way of processing dried corn. Soaking and steeping maize in an alkaline agent (calcium hydroxide, commonly known as lime) is called nixtamalization—a process that strips off the corn kernel’s outer layer, making it easier to grind, increasing its nutritional quality, and improving its aroma and flavor.

I adapted Sean Sherman’s Missouri Pozole and used De Colores Farms & Foods hominy nixtamal kit for this recipe. Allow 8 hours to prepare the hominy using the kit. You can substitute the nixtamal kit for 2 cups of dried hominy soaked overnight. If using the hominy nixtamal kit, I recommend longer cooking time (90 minutes) in the first step of the instructions. While preparing the squash, save the seeds and make roasted squash seeds for a garnish; see recipe on page 42.

1 pound hominy nixtamal kit, prepared following instructions

1 small butternut squash, peeled and cut into 1/2-inch cubes (about 4 cups)

1 tablespoon fresh sage, chopped

1 teaspoon red chile powder

6 cups corn stock (see recipe, page 42) or water

1/4 cup masa flour mixed with 1/2 cup water

1 tablespoon maple syrup or more, to taste

1 batch roasted squash seeds (see recipe, page 42)

1 batch fried sage (see recipe, page 42)

Salt, to taste

Over medium heat, combine corn stock and hominy in a large stockpot. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for about 30 minutes, until hominy is al dente. (Note that cooking time may vary depending on the source and age of your hominy.) Add remaining ingredients—squash, red chile, and sage— and cook at a simmer until squash is tender, about 25 minutes. Slowly stir in the masa flour/water mixture and continue simmering until thickened. Season, to taste, with maple syrup and salt. Garnish with roasted squash seeds and fried sage.

Makes 8 bean cakes

Eat these alone as snacks, on top of salad greens, with eggs, or topped with grilled squash. I use bolita beans in this recipe because they are creamy in texture and a little sweeter than pinto beans.

2 cups cooked beans (all liquid should be drained off) 1 1/2 teaspoons fresh sage leaves, chopped 1 duck egg (or 1 extra-large chicken egg)

1/4 cup chopped shallot 1/8 teaspoon salt 1/8 teaspoon crushed juniper berries, dried 1/8 teaspoon dried sumac 1/4 cup corn flour, plus 1 tablespoon for dusting 3–4 tablespoons sunflower oil

In a food processor, pulse together all ingredients to make a rough dough. Using your hands (moistened with water), form dough into 3-inch patties that are 1/2-inch thick. Dust with corn flour and set aside.

Add oil to a skillet and heat on medium. Cook bean patties in batches until golden brown, approximately 5–7 minutes per side.

Freddie Bitsoie exchanges the open fire for a stovetop grill in this simple-to-execute squash dish. This recipe would work with any kind of winter squash except spaghetti squash.

1/4 cup sunflower oil 1 tablespoon agave nectar 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoon pepper 1/2 shallot, diced 1 tablespoon fresh sage leaves, chopped 1 butternut squash peeled, seeded, halved, and cut into 1/4-inch slices Sumac for garnish

Mix oil, agave, salt, pepper, shallot, and sage in a large bowl. Add squash to the bowl and stir to coat. Heat a grill pan on high heat. When the pan is hot, cook squash for 3 minutes on each side. Sprinkle with sumac.

Sean Sherman uses tepary beans in this recipe, but they can sometimes be challenging to source, so I substituted another bean long cultivated in the Southwest—Anasazi beans.

6 cups cooked Anasazi beans

1 cup reserved liquid from cooking beans (or broth)

1 tablespoon sunflower oil

1/2 small yellow onion, thinly sliced

3 tablespoons agave nectar

1 tablespoon red chile powder, plus more for garnish

1 teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

2 teaspoons whole fresh oregano leaves

In a large, deep skillet, heat the oil over medium heat. Add onion and sauté until translucent, about 4 minutes. Add cooked beans, reserved bean cooking liquid, agave, and chile powder. Cook, stirring occasionally, until liquid has reduced to a glaze, about 10 minutes. Season with salt, to taste, and garnish with additional chile powder and oregano leaves.

indigikitchen.com sioux-chef.com napi.navajopride.com flowerhill.institute toastedsisterpodcast.com @EastMeetsKitchen on YouTube

The Pueblo Food Experience edited by Roxanne Swentzell and Patricia M. Perea

The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen by Sean Sherman with Beth Dooley

New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian by Freddie Bitsoie and James O. Fraioli

Foods of the Southwest Indian Nations: Traditional and Contemporary Native American Recipes [A Cookbook] by Lois Ellen Frank

Manko, food truck around the state Yapopup, a popup in Ohkay Owingeh and beyond Red Mesa Cuisine, catering in Santa Fe Juniper Coffee + Eatery, Farmington Itality Plant Based Foods, Albuquerque Indian Pueblo Kitchen, Albuquerque El Roi Cafe, Albuquerque

RODRIGUEZ S&J FARM’S Anasazi, black, bolita, and pinto beans have unique flavors and textures that you don’t find with commodity beans. The farm, located in El Guique, also carries chicos, posole, and chile powder. You can find them at the Santa Fe Farmers’ Market year-round or purchase their products through New Mexico Harvest.

BECK AND BULOW’S bison tallow adds a punch of smoky flavor to beans and other dishes that typically use bacon. Find their tallow at their storefront in Santa Fe or buy online at beckandbulow.com for delivery or pickup.

DE COLORES FARMS & FOODS' nixtamal kits include June corn, food-grade cal (lime), and instructions on the tradition of nixtamalization. The nixtamal can then be ground for fresh tortillas, used in pozole, and much more. De Colores is located in Berino, and their products can be sourced through New Mexico Harvest.

SHIMA’ juniper ash is made the slow Navajo way with junipers from the Chuska Mountains near Fort Defiance. Juniper ash is a traditional addition to blue corn bread, tortillas, and pancakes. This hard-to-find food adds a distinctive flavor, makes corn bread a deep blue, and raises the level of nutrients: calcium, zinc, iron, and magnesium. Shima’ juniper ash can be sourced through 4Kinship at their storefront in Santa Fe or online at 4kinship.com

Chicos are dried kernels of sweet corn, traditionally roasted in an horno. Once rehydrated, they taste like the sweetest roasted summer corn you’ve ever had— intensified. They are listed on Slow Food USA’s Ark of Taste, a catalog of outstandingly delicious traditional foods in danger of extinction. Chicos usually are available at farmers markets and other local sources around New Mexico in the fall and early winter, but they go fast. We source ours from Rodriguez

S&J Farm or Schwebach Farm. New Mexico Products Curated by edible Photo by Stephanie Cameron SPONSORED

SPONSORED

Recipe

8

and photo by Stephanie Cameron

and photo by Stephanie Cameron

Filling

1 1/2 cups cooked butternut squash*

1/4 cup pure maple syrup

1 tablespoon light brown sugar

2 1/4 teaspoons arrowroot starch (or cornstarch)

1/2 tablespoon ground cinnamon

1/4 cup butter, room temperature

1 egg

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

1/8 cup warm water

Tart Crust

3/4 cup blue cornmeal**

3/4 cup yellow cornmeal, fine grain

3 tablespoons sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon anise seed, lightly crushed

1/2 cup cold butter, diced

1 egg yolk, beaten

1/3 cup ice water, or more as needed

To make the crust, whisk dry ingredients together. Cut in butter until crumbly. Add egg yolk and stir with a fork. Add ice water

and stir until the mixture holds together when squeezed. Form into a ball, flatten into a disk, and chill for at least 2 hours or up to a day ahead of time. Bring to room temperature before using. Combine all filling ingredients in a high-powered blender or food processor and blend on medium speed for about 3–4 minutes until batter is smooth.

Preheat oven to 350°F. Press and shape dough into a 9-inch tart pan. Parbake by placing tart shell on a sheet pan and bake for 10 minutes. Remove crust from the oven.

Pour the filling into tart crust. Bake for 50 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Cool tart on a wire rack for 15–30 minutes. Serve with toppings of choice.

*Note: To cook butternut squash, preheat oven to 350°F and cut squash in half, removing seeds completely. Add 2–3 cups of water to a large ceramic baking dish. Poke holes around the squash with a fork and place squash in the dish, flesh side up. Bake for 60–90 minutes, until a fork easily pierces the flesh. Let the squash cool for about 20 minutes before peeling the skin off. Puree squash in a food processor or blender until smooth. Store in an airtight container in refrigerator until needed.

**Sourcing note: La Montañita Co-op carries Tamaya Blue Corn and Tamaya Yellow Corn in their bulk section.

Beans. Yes, they can be noisy, but they’re also resilient, humble, diverse, and, well, they are tough as hell. In short: beans are the food of the people.

Have you ever walked into a home after a long day at school or work and been greeted by the smell of a pot of beans? I have—in the cabin where I was raised. In my nana’s yellow kitchen. In my best friend’s house, where her mother used a micaceous pot to cook them. In my first studio apartment in college. At my first house with a boyfriend. In the camper I lived in when everything went wrong. In the home I now share with my husband and children.

This is my love letter to beans.

Since I was born, the smell of boiling beans has filled every room I have ever gone home to, all across the Southwest.

Beans, which have now become a family of over four hundred cultivated varieties, were domesticated on Turtle Island so long ago that they have become a part of our Indigenous peoples’ creation stories. They are sacred. In one cup of cooked pinto beans, the human body receives 15.41 grams of protein, 15.39 grams of fiber, 85.5 milligrams of magnesium, 745.56 milligrams of potassium, 251.37 milligrams phosphorus, 78.66 milligrams calcium, and 244.53 calories, according to University of Rochester Medical Center.

First grown in the highlands and lowlands of Mexico and then in the Andes, the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) is indigenous to the Americas and is considered the mother of almost all modern beans, including snap beans, dry beans, and shell beans. Of at least seventy wild species in the Phaseolus genus, all native to the Americas, three others were domesticated long ago: lima beans, runner beans, and

tepary beans. Other types of legumes, such as chickpeas, lentils, and fava beans (Vicia faba), have been cultivated in Europe, Asia, and Africa for thousands of years.

When times were hard, and they’ve been plenty hard, beans have kept me alive—home-cooked, canned, or refried. I learned this from my ancestors’ survival. It’s imprinted in my DNA. You won’t die so long as there are a few beans on hand.

My father is a sixth-generation cattle rancher. When I had my daughter, I had trouble with my milk supply. He told me a story about how he had dry mama cows, so he started giving them beans. After a bean feast, they made milk like never before, so I started eating beans like crazy.

During my pregnancy, plagued by twenty-four-hour morning sickness for seven months, my unborn daughter and I survived on bean and cheese burritos. When my baby started eating solid food, who would feed her a bowl of mashed beans first became a competition. My mother won. It was a moment, because beans aren’t just food, they’re family.

There is no scent more nurturing, no flavor more life affirming, than that of a fresh pot of beans. Pintos, limas, Anasazis, Hopi string beans, scarlet runners—it doesn’t matter the kind, color, or language, every pot of dry beans boils with life.

I have a list of the scents that take me home, and among them are the St. Ives lotion my nana wore; the fragrance of sawdust, gasoline, and coffee that is my father; the aroma of the first monsoon rain carving into an arroyo; and an afternoon room greeting me with the smell of beans.

Water is life, but beans are its heartbeat. Beans are heroic. Beans are a thumbprint of our evolution on earth. Beans transcend class, culture, and time.

Opposite page: Collection of beans from Pete Daniel’s bean bank.

Water is life, but beans are its heartbeat. Beans are heroic. Beans are a thumbprint of our evolution on earth. Beans transcend class, culture, and time. They are not just a part of Indigenous survival; they have become part of our global survival. Little stinky ambassadors—how can you not love that?—wrapped in a tortilla and smothered in chile and cheese! Ay!

But seriously, could the Allied forces have had the strength to win World War II if not for the fuel of beans? Pinto beans that were cultivated in places like Estancia, Moriarty, and Mountainair. I want to believe that beans were a factor in all of our major triumphs, from the Pueblo Revolt to surviving Bosque Redondo, to me graduating college and having my first baby.

My first job was cleaning the beans. We lived in a two-room cabin that my parents had built by hand on the family ranch. The kitchen table was a butcher-block slab of wood on top of tall stumps. Despite its magnitude, it was something I associated with softness. It was smooth from meals prepared—the flour and Crisco of hundreds of tortillas, sugar cookies, and biscuits—and if I pressed my nail into its surface I could leave my own mark.

This was my perch, illuminated with the afternoon light that came in through miles of undisturbed ranchland onto the table where dinner would begin with me, the bean cleaner. Scattering a thin layer of pinto beans in front of me, I sifted through them, one by one, meticulously separating out the hard dirt clumps. I was

vigilant in determining whether or not a bean met my qualifications before going in the pot.

It was the early nineties, but we didn’t have electricity. Mom cooked dinner on an antique propane stove built in the early 1900s. I loved the sound of the pressure cooker rattling and steaming, the smell of beans in the air signaling the nearness of satisfaction, of fullness. Beans, chile, tortillas, and elk sustained us through every season, and, along with warmth made from burning wood, protected our family against cold, hunger, and the outside world.

Throughout my childhood, I never knew my grandfather not to spend his summer nights in a hammock, strung between the walnut trees, so he could be alert to chase elk out of his garden. This garden was paradise, situated between the Frisco River and the Gila Wilderness. It was a garden that could feed a family. Some beans, like pintos, bolitas, and teparies, are suitable for dryland farming, and although big farms such as Ness Farms in Estancia, Schwebach Farm in Moriarty, and the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry in Farmington rely on drip and sprinkler irrigation, many Hopi and other growers still use dryland methods.

But Earnest Daniel, aka Grandpa Pete, had his own way of doing things. In the spring, Grandpa put his beans in dampened Mason jars that he slept with at night to keep warm. These were varieties he had collected all across the West, and some he had developed himself. After the harvest, he would sit at the kitchen table and lovingly admire his beans, each one beautiful and unique, in vibrant reds and purples, yellows and blacks, selecting the best of the best to store away for the years to come.

Grandpa turned one hundred in 2022. We attribute his longevity to a steady diet of beans. Unfortunately, he isn’t able to tell me about his adventures in beaning anymore, but my mother helps fill in the gaps.

“Beans were Dad’s passion. He grew them, crossbred them, and played with them for years,” my mother, Rebecca Daniel, tells me. “He came up with all sorts of colors and shapes and types of beans. He was interested in this yellow bean that he called ‘Indian Woman Yellow.’ He had gotten it in Montana and said the Native Americans in Montana grew it for a shell bean.”

Grandpa was fascinated by this little yellow bean, which he said was grown all over the West by Indigenous people. Then he got his hands on a book about the Indigenous Rarámuri people of Mexico, also known as the Tarahumara, and learned about their farming ways.

“He wanted to go to the Sierra Madres and meet the Tarahumara to see if he could get that yellow bean from them to cross with the one from Montana, so as to strengthen the genetics,” my mama tells me. And so in 1999, she and my grandpa, who was seventy-seven at the time, along with their friend Jay Scott, caught a bus from Juárez to the city of Chihuahua. From there they took a train to the top of the Sierra Madres to a village where they were able to hire a cab driver.

“This guy took us in a cab for miles and miles out across the mountains through the woods,” remembers my mother. “I was just

holding my breath that this cab wouldn’t break down or blow a tire or whatever because we were out in the middle of nowhere on this dirt road in the mountains. At the end of the road, there was a trading post, and when we got there all these Tarahumara men were sitting outside, smoking rolled cigarettes.”

At the trading post, they told the men about their bean journey, and, says my mother, “the locals pulled out all their seeds and gave my grandpa some big purple-speckled beans, a big white bean, and others, including the Indian Woman Yellow bean.”

“He brought home quite a stash of seeds and grew them. The Indian Woman Yellow bean had a particularly great flavor,” says my mother. “I really liked it, but he was never able to grow it in abundance to where I could have a lot to cook. Mostly he was doing it for seed, and he’s got quite a seed bank of beans.”

I remember dinners with my mother’s parents. They always involved a bowl of Grandpa’s beans, which began in all shapes and colors and ended up in a tasty soup, made tastier with freshly canned bread-and-butter pickles and some pepper jack cheese.

Grandpa irrigated his beans and the rest of his garden from a natural spring, a mile or more away in the Gila Wilderness. In his garden, he made pathways canopied with trailing beans, blooming in different colors. The big purple beans Grandpa was given by the Rarámuris bloomed brilliant scarlet and drew in every pollinator around. Today I’ve seen them labeled the scarlet runner bean, and sold in specialty bean shops like Rancho Gordo. But in Grandpa’s day, no one was growing beans like his.

In his seed bank is another unusual bean that looks like an Anasazi bean except it’s black and white rather than maroon and white. I’ve seen it called a vaquero bean and referred to as a cousin of the classic Anasazi bean, which Grandpa also grew. This particular bean was given to him by a friend who discovered it in a cave ruin, most likely left over from the Mimbres people who inhabited southern New Mexico from the tenth to the twelfth century, according to anthropologists.

As I sort through a bag of my grandpa’s beans, I’m captivated by the way each bean is unique, and yet how each one bears a slight resemblance to the others. Being close to twenty years old now, the vibrant purple beans he received from the Rarámuris have turned a color so deep as to be black, yet I can still see traces of purple in some of their descendants. I find incredible little beans with markings like those on Anasazi and yellow eye beans that also bear patterns of the larger scarlet runner beans and Hopi string beans. I’m told it is unusual for a common bean like the Anasazi to cross with a runner bean, yet it happened in my grandpa’s garden. Beans have been a survival food for so long, and I envision them feeding people into the future, persevering through changing conditions in the land. In other ancestral Puebloan and Mimbres ruins where beans have been found, they weren’t thousands of years old but were rather the wild descendants of beans grown in those ancient times. They, like people, carry the resilient DNA that keeps them adaptable, dependable, and one of our closest plant allies.

My father dropped me off at her house each morning cocooned in a white bedspread with pink flowers she bought for me. Nana could still carry me then. I was small, and she was healthy. As her goddaughter, she claimed me as what she always wanted but never had: a girl. Most mornings, I uncurled my limbs, wiped the sleep from my eyes, and wandered through the small house toward her smells. Cinnamon pinched in coffee, tomatoes stewing in rice, and holy water. Most often I would find her standing at the stove, presiding over her kingdom—frijol her court, Jesus her advisor. After a kiss and the Lord’s Prayer, she would serve me a floral china mug filled with milky-warm atole—the blue corn porridge of her homeland.

In a 1987 travel article from the New York Times, Susan Benner wrote of blue corn, “The colors and textures seemed as Southwestern as adobe. . . . That night I felt as if I were eating earth—not dirt, but food that was somehow connected to the richness of earth.” While much has changed in land and agriculture since the year that article was published, Benner’s testament of blue corn’s relation with place remains true today.

blue corn, are dried, roasted, often nixtamalized (treated with an alkali), and prepared in various forms of flours, meals, posole (hominy), and chicos. They’re used to make foods such as Hopi piki bread (a thin-layered oven bread), tortillas, pancakes, and porridge. This porridge is what the Hopi call wataca, the Diné (Navajo) call mush, Puebloan people call chaquehue, and what I learned from my godmother as atole, a word that comes from Nahuatl. The blue corn kernels are roasted prior to milling, giving the hot cereal a nutty, earthy flavor. In its simplest form, atole is a porridge of toasted ground cornmeal, water, and sometimes salt or sweetener, often thin enough to drink, but other times thick like polenta.

To understand the cultural place blue corn mush holds in the American Southwest is to understand the movement of peoples and seeds across space and time. The domestication of maize began nine or ten thousand years ago in what is now southern Mexico and Guatemala. Over time, corn spread across the Americas with the movement of Indigenous peoples. Ancestral Puebloans began to establish semipermanent settlements where they could cultivate corn as early as 2000 BCE. The need for corn to be cultivated in rows led to advances in irrigation techniques, like ditches for rainwater runoff, starting around 250 CE.

Maize ( Zea mays ) can be grouped into two broad categories: that harvested young (usually sweet corn) and eaten fresh, and that harvested mature (including field corn, flint corn, and flour corn) and eaten dry. Flour and flint varieties of corn, such as

When the first Spanish colonizers came into contact with Puebloan and Hopi peoples around 1540 CE, they had been cultivating and tending to corn—including blue corn—beans, and squash in a symbiotic relationship with the lands, each other, and nonhuman

Like the corn dances of the Pueblo peoples along the Rio Grande or the Hopi origin story, blue corn is a weaving of culture, spirit, and practice, a process that cannot be fully understood on a timetable. For those who cultivate it, who know it intimately, the spirit of blue corn’s connection to place may be enough.

relations for hundreds of generations. These first Spanish colonizers reported seeing Native people spreading cornmeal around their doorways to ward off the conquistadores. The Spanish most likely also witnessed Hopi peoples harvesting, drying, storing, decobbing, roasting, and grinding their corn into wataca, in a fashion similar to what they do today.

Hispano settlers claimed land along the Rio Grande and its tributaries. They adopted Native farming and irrigation practices while integrating methods for arid agriculture learned from the Moors, who brought acequia systems to the Sierra Nevada of southern Spain from North Africa in the eighth century. Thus, atole is an adaptation of Indigenous foodways and ways of knowing that includes the cultural building of acequia communities we see today.

Johnson is ultimately concerned with the “revitalization of the American Indian food system.” For him, this is the process of elevating Indigenous ways of knowing as a “value system and culture that allows us to bounce back.” That is to say, for Johnson, corn, especially blue corn, is not merely a food; it represents “humility, patience, and endurance” in the face of cultural and climate threats.