ADVANCES IN UROLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS AND IMAGING

The prevalence of kidney stones is increasing worldwide, and it is estimated that the recurrence rate is 50% (1).

Reduced urinary volume due to insufficient fluid intake or excessive loss of them represents one of the most crucial risk factors (2).

A meta-analysis on the role of fluid intake in the secondary prevention of urolithiasis concluded that a high total intake of fluids to achieve a urine volume of more than 2.0 to 2.5 L/day reduces the risk of stone recurrence (3).

Ultimately, adequate fluid intake is the most important nutritional measure to prevent stone recurrence, regardless of their composition (2). It should be emphasized that in the course of renal colic, oral hydration should not be forced and should be kept normal (4).

Water should preferably be of low fixed residue and are to be avoided the waters rich in sodium (5).

Mineral waters, based on total salt content in milligrams after evaporation of 1 liter of dried mineral water at 180°C (dry residue) can be classified as (6):

• very low mineral content waters,

• waters with low mineral content,

• waters with medium mineral content,

• highly mineralized waters.

Lauretana mineral water from the Biella Prealps (Piedmont) is very light, with little sodium and a slightly acidic pH, in addition, the search for insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, nematicides, acaricides, algaecides, rodenticides has been found to be negative (7).

Lauretana mineral water, as it is low in sodium, has no contraindications in subjects with high blood pressure (8), and finds, moreover, a precise indication in cases where adequate and correct water intake for the prevention of urinary stones, particularly in metabolically predisposed individuals and in the prevention of recurrences after treatment (9).

1. Siener R. Nutrition and Kidney Stone Disease. Nutrients. 2021 Jun 3;13(6):1917.

2. Siener, R.; Hesse, A. Fluid intake and epidemiology of urolithiasis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, S47–S51.

3. Fink HA, Akornor JW, Garimella PS, et al. Diet, fluid, or supplements for secondary prevention of nephrolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Urol. 2009; 56: 72-80.

4. Hernhard Hess. Renal colic. In The Stone Hand Book. Edizioni Scripta Manent, Milano 2013.

5. Zanasi A. Guida all’uso ragionato delle acque minerali. Giugno 1999.

6. Decreto Legislativo numero 105 del 25 gennaio 1992.

7. Claudio Medana, Dipartimento Di Biotecnologie Molecolari e Scienze per la Salute - Università di Torino. 12.12. 2023.

8. Prof. Dott. Giancarlo Levra. Scuola di specializzazione in Idrologia Medica -Università degli Studi di Pisa.

9. Dott. Marco Laudi Direttore U.O. di Urologia Ospedale Mauriziano Umberto I Torino.

Pietro Cazzola (Pathologyst), Milan (Italy)

Donatella Tedeschi (Pathologyst), Milano (Italy)

Ahmed Hashim, London (Great Britain)

Ali Tamer, Cairo (Egypt)

Benatta Mahmoud, Oran (Algeria)

Bhatti Kamran Hassan, Alkhor (Qatar)

Cheng Liang, Indianapolis (USA)

Fragkiadis Evangelos, Athens (Greece)

Gül Abdullah, Bursa (Turkey)

Jaffry Syed, Galway (Ireland)

Kastner Christof, Cambridge (Great Britain)

Lopez-Beltran Antonio, Lisbon (Portugal)

Salomon George, Hamburg (Germany)

Waltz Joachen, Marseille (France)

Wijkstra Hessel, Eindhoven (Netherlands)

“Advances in Urological Diagnosis and Imaging” (AUDI) has the purpose of promoting, sharing and favorite technical-scientific research on echography and imaging diagnosis, in diagnostic and terapeutical field of Urology, Andrology and Nefrology. AUDI publishes original articles, reviews, case reports, position papers, guidelines, editorials, abstracts and meeting proceedings.

AUDI is Open Access at www.issuu.com

Why Open Access? Because it shares science at your finger tips with no payment. It is a new approach to medical literature, offering accessible information to all readers, becoming a fundamental tool, improving innovation, efficiency and interaction among scientists.

COPYRIGHT

Papers are accepted for publication with the understanding that no substantial part has been, or will be published elsewhere. By submitting a manuscript, the authors agree that the copyright is transferred to the publisher if and when the article is accepted for publication. The copyright covers the exclusive rights to reproduce and distribute the article, including reprints, photographic reproduction and translation. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher.

ADVERTISING

For details on media opportunities within this journal please contact Mrs. Donatella Tedeschi, MD at +39 0270608060

1 Urine retention in a woman with a Skene gland abscess

Konstantinos Stamatiou, Marios Ioannou, Georgios Valassis, Alexandros Bleibel, Giorgos Simatos

4 The AUA/SUFU Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Overactive Bladder (2024)

7 2023 Canadian Urological Association guideline: Genetic testing in prostate cancer

9 The management of urinary calculi: the role of the General Practitioner

Edizioni Scripta Manent s.n.c.

Via Melchiorre Gioia 41/A - 20124 Milano, Italy

Tel. +39 0270608060

Registrazione: Tribunale di Milano n. 19 del 17/01/2018

e-mail: info@edizioniscriptamanent.eu web: www.edizioniscriptamanent.it

or

Direttore Responsabile: Pietro Cazzola

Direzione Marketing e PR: Donatella Tedeschi

Comunicazione e Media: Ruben Cazzola

Grafica e Impaginazione: Maria Isola

Affari Legali: Avv. Loredana Talia (MI)

Urology

Department, Tzaneio General Hospital, Piraeus, Greece.SUMMARY

Urinary retention related to obstructive causes is uncommon in women. In this article, we present a rare case of urinary retention in a woman due to urethral obstruction by an abscessed gland of Skene. Case outline A 40-year-old woman presented inability to urinate, and vaginal edema. The external opening of the urethra was not visible due to a firm, round mass on the upper vaginal wall. Systemic antibiotic administration was administered

Urinary retention is uncommon in women. In fact, due to the absence of a sufficient number of relevant studies, the etiology and epidemiology are not sufficiently clarified (1). There are numerous causes that are broadly categorized into inflammatory, pharmacogenic, neurogenic, anatomical, myopathic and functional (2). In contrast to urinary retention in men, purely obstructive causes are rare (3). In this article we present a rare case of urinary retention in a woman due to the urethral obstruction by an abscessed gland of Skene .

A 40-year-old woman is presented with symptoms of lower urinary tract infection and inability to urinate. Antecedent by a month of dyspareunia and vaginal edema. Apart of a history of recurrent urinary tract infections and recurrent upper vaginal wall edema nothing else was reported. In the clinical examination, enlarged urinary bladder is palpated suprapubically, while the renal areas are free of pain under percussion and deep palpitation. The residual urine in the posturinary examination were 310 ml. The external orifice of the urethra was not visible and a firm round mass

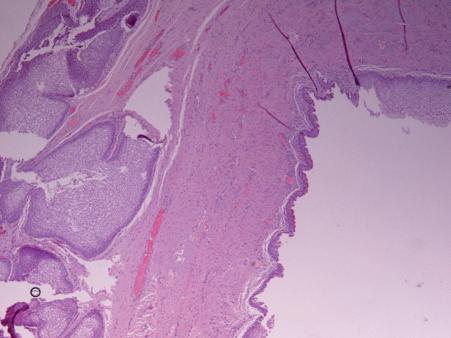

before surgical removal. Histological examination of the removed mass confirmed the diagnosis of a cyst lined by metaplastic squamous epithelium and pseudostratified columnar epithelium. Patient regained the ability to urinate after the removal of catheter.

Key words: urinary retention; paraurethral cysts; paraurethral abscess; Skene gland abscess.

appeared on the upper vaginal wall. A bladder catheter was placed and oral antibiotics were given. As a second step procedure an ultrasound examination and urethrocystoscopy were performed followed by surgical excision.

Histological examination of the removed mass confirmed the diagnosis of cyst lined by metaplastic squamous and pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

The Skene glands are bilateral paraurethral glands located in the lower part of the peripheral urethra. They are lined by stratified squamous epithelium due to their origin from the urogenital sinus. Their role is to secrete a mucus that helps in lubricating the urethra (4). Obstruction of the ducts leads to the formation of paraurethral cysts. These cysts are usually presented as small, cystic masses, laterally and below the urethra. Although the etiology of pore obstruction is unknown, paraurethral cysts occur exclusively as a result of chronic inflammation of the Skene glands and are associated with sexual contact. Typically, Skene gland disorders are rare during the prepubertal period and cysts and abscesses usually occur in the third or fourth decade of life (5).

The pathological picture of the case presented here is typical of chronic and recurrent inflammatory process. The cysts are usually asymptomatic and are found randomly on clinical examination as a palpable or visible mass. On the contrary, abscesses have a loud clinical picture that includes local pain, dyspareunia and purulent secretion. Urinary retention has been associated with benign tumors (paraurethral leiomyomas) in several cases (6), but only one case of urinary retention caused by Skene gland abscess has been reported so far (7). The differential diagnosis includes the displaced Bartholin gland and the urethral diverticulum.

Ultrasound and urethroscopy can be helpful in diagnosis . In more severe cases, MRI is typical: the cysts of the Skene gland appear as round or oval lesions, lateral to the urethra, near the external urethral meatus. The management of paraurethral cysts is controversial. Large, symptomatic cysts may require surgical excision or marsupialization, usually with excellent results. Large cysts may also require needle aspiration in the presence of an overlying infection. In the case we report the second-step procedure had excellent results and there was no recurrence one month after the exclusion.

K. Stamatiou, M. Ioannou, G. Valassis, A. Bleibel, G. Simatos

pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

1. Stamatiou K, Elnagar M. Urinary Retention in Women. Hellenic Urology. 2014; 26(2);24-36.

2. Dougherty JM, Rawla P. Female Urinary Retention. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. (Jan 2020). 22.

3. Stamatiou K. Urinary retention due to benign tumor of the bladder neck in a woman; a rare case of papillary cystitis. Urologia. 2013; 80(1);83-85.

4. Skene A. The anatomy and pathology of two important glands of the female urethra. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children. 1880; 13;265–70.

5. Sharifiaghdas F, Daneshpajooh A, Mirzaei M. Paraurethral cyst in adult women: experience with 85 cases. Urol J. 2014; 11(5);1896-9.

6. Maeda K, Wada A, Kageyama S, et al. A Female Paraurethral Leiomyoma Causing Urinary Retention: A Case Report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2015; 61(11): 455-8.

inflammation.

7. Stovall TG, Muram D, Long DM. Paraurethral cyst as an unusual cause of acute urinary retention. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1989; 34 (6);423-5.

authors contr I but I ons

All Authors whose names appear on the submission.

1. Made substantial contributions to the conception of the paper;

2. Drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content;

3. Approved the version to be published.

C orresponden C e Konstantinos Stamatiou, MD 2 Salepoula str. 18536 Piraeus, Greece E-mail: stamatiouk@gmail.com

1 https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/idiopathic-overactive-bladder

This AUA guideline is provided free of use to the general public for academic and research purposes.

Cameron AP, Chung DE, Dielubanza EJ, et al. The AUA/SUFU guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic overactive bladder. J Urol. Published online April 23, 2024.

This is a brief summary to help younger colleagues.

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as “ urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology”.

Some other definitions:

Urgency is defined as the “complaint of a sudden, compelling desire to pass urine which is difficult to defer”. Urgency is considered the hallmark symptom of OAB;

Increased daytime Urinary Frequency is defined as the “complaint that micturition occurs more frequently during waking hours than deemed normal”. Traditionally, up to seven micturition episodes during waking hours has been considered normal, but this number is highly variable based upon hours of sleep, fluid intake, comorbid medical conditions, and other factors.

Nocturia is the “complaint of interruption of sleep one or more times because of the need to micturate. Each void is preceded and followed by sleep”. Like daytime frequency,

nocturia is a multifactorial symptom which is often due to factors unrelated to OAB (e.g., excessive nighttime urine production, fluid intake before bed).

UUI (Urgent Urinary Incontinence) is the “complaint of involuntary leakage of urine associated with urgency (i.e., a sudden compelling desire to void)”.

In population-based studies, OAB prevalence rates range from 7% to 27% in men, and 9% to 43% in women. OAB symptom prevalence and severity tend to increase with age.

Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of OAB is bothersome urgency which may be accompanied by UUI. Often, symptoms of urinary frequency (both daytime and nighttime) are also reported and support a diagnosis of OAB.It is common for patients to have suffered with their symptoms for an extended time before seeking medical advice.

A diagnosis of nocturnal polyuria (i.e., the production of greater than 20% to 33% of total 24-hour urine output during the period of sleep) is largely age-dependent: >20% for younger individuals and >33% for elderly individuals. Nocturnal voids associated with nocturnal polyuria are frequently normal or large volume as opposed to the small volume voids commonly observed in nocturia associated with OAB. Sleep disturbances, vascular and/ or cardiac disease, and other medical conditions are often associated with nocturnal polyuria.

OAB can be distinguished from other conditions, such as excess fluid intake (more than eight glasses of water per day), with a frequency-volume chart (i.e., a voiding diary). If the patient has urinary frequency because of the high intake volume with normal or large volume voids, then the patient most likely does not have OAB. This can be managed with education and fluid intake management.

Overactive Bladder Treatment Options

Incontinence Management Strategies

Behavioral Therapies

Optimization of Comorbidities

Non-invasive Therapies

Pharmacologic Therapies

Minimally invasive Therapies

Invasive Therapies

Indwelling Catheters

The clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) shares the symptoms of urinary frequency and urgency, with or without UUI; however, bladder and/or pelvic pain, including dyspareunia, is a crucial component of this diagnosis.

Other conditions can contribute to OAB symptoms and should be diagnosed since their treatment can improve OAB symptoms. For example, in the patient transitioning through menopause, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) can be a contributing factor to urgency and incontinence symptoms.There is some evidence for symptom improvement with the use of vaginal (but not systemic) estrogen. Similarly, UTI can have similar symptoms as OAB, but generally is acute in onset, of shorter duration, and accompanied by other clues such as dysuria, or suprapubic discomfort and resolved with antibiotics. LUTS related to neurological conditions such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis are considered neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD) and not idiopathic OAB.

Products to better cope with or tolerate urinary incontinence. These do not treat or prevent incontinence, rather they reduce adverse sequalae of incontinence, such as urine dermatitis

Actions that patients with OAB can perform at home to directly address and improve their OAB symptoms. Can be supported by education or training but are driven by the patient

Medical conditions known to affect the severity of OAB that can be treated or managed

Treatments provided by a nurse or allied health professional that may involve practice or treatments at home

Prescription medications that are taken to directly treat bladder symptoms

Treatments that are procedural or surgical but with low risk of complication or adverse events

Surgical treatments that have higher risks of complications or adverse events

Any urinary catheter left in the bladder as a method to treat incontinence

Diapering, pads, liners, absorbent underwear, barrier creams, external urine collection system, condom catheters

Timed voiding, urgency suppression, fluid management, bladder irritant (caffeine, alcohol) avoidance

BPH, constipation, diuretic use, obesity, diabetes mellitus, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, pelvic organ prolapse, tobacco abuse

Pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, electromagnetic therapy

Beta-3 agonists, antimuscarinic medications

Botulinum toxin injection of bladder, sacral neuromodulation, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, acupuncture, implantable tibial nerve stimulation

Urinary diversion, bladder augmentation cystoplasty

Indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheters

Patients with prostates experience OAB nearly as often as those without, but due to the common misconception that all voiding symptoms are attributable to the prostate, they are often underdiagnosed and undertreated for their symptoms. While some patients with prostates experience symptoms of both benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and OAB, others have OAB alone and would benefit from diagnosis specific treatment.

The term “refractory OAB” is used in the urologic literature, but there is no clear definition of what this means. A patient can be refractory to behavioral changes, pelvic floor muscle training, pharmacotherapy, or other modalities. Some studies have used “refractory OAB” to mean refractory to two oral medications for OAB.

Cognitive dysfunction with anticholinergic medication

The role of anticholinergics in the treatment of overactive bladder

Pedro BlascoHernández

Urology Service

HU de Valme Seville (ES)

Cognitive impairments are a possible result of the long-term use of anticholinergics in the treatment of OAB. This increased impairment of cognitive function is associated with a higher likelihood of developing new-onset dementia, particularly in elderly patients or those with a pre-existing mild cognitive disorder that may be unknown to both the patient and their caretakers. All healthcare professionals involved in OAB treatment need to keep this cognitive impairment in mind, especially because of the impact it can have on a patient’s quality of life. In patient-centered care, a shared decision-making process can help improve patient adherence to treatment and healthcare related results.

1 Rendon RA, Selvarajah S, Wyatt AW, et al. 2023 Canadian Urological Association guideline: Genetic testing in prostate cancer Can Urol Assoc J 2023;17(10):314-25.

Genetic testing in prostate cancer (PCa) is becoming standard of care, as it can provide key information for clinical management, as well as offering crucial insights into familial cancer risk. Knowledge of genetic alterations present in prostate tumors offers prognostic insight and can aid with therapeutic decision-making.

In addition, PCa can be hereditary, and patients with PCa may carry germline (inherited) gene alterations that affect their risk of additional cancers.

Identification of germline gene alterations in PCa patients provides an opportunity for cascade testing in family members, opening up avenues for cancer prevention and early diagnosis in family members who may also carry the same germline gene alterations.

1. Germline testing should be performed in prostate cancer patients with metastatic disease.

2. In the context of localized prostate cancer, germline testing should be performed in the following patients:

a. Those with a positive family history of prostate or related cancers (most commonly breast, ovarian, colorectal, and endometrial cancers; occasionally pancreatic, upper tract urothelial, stomach, small bowel, and brain cancers; rarely melanoma);

b. Tthose with a personal history of related cancers (most commonly colorectal cancer; occasionally pancreatic, upper tract urothelial, stomach, small bowel, brain, and male breast cancers; rarely melanoma);

c. Those with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry;

d. Those with high risk or very high-risk disease (Gleason score 8 or higher, clinical stage T3a or

T3b or higher, or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) higher than 20 ng/ml);

e. Those with ductal, intraductal, or cribriform histology.

3. Germline testing should be performed in patients with actionable or potentially actionable variants identified with tumor testing to determine whether the variant is germline in origin, to inform future cancer risk, and to initiate cascade testing in family members.

4. Germline testing may be performed at any time after a patient is diagnosed with prostate cancer but is ideally performed as soon as the patient is determined to be a candidate for testing (Good practice point).

5. Genomic profiling of the tumor should be performed in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) to inform the selection of therapy.

6. Genomic profiling of the tumor should be performed in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) and patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer prior (nmCRPC) to progressing to mCRPC.

7. The minimum set of genes for germline testing in patients with prostate cancer who meet criteria for germline testing should include ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, EPCAM (large deletions), HOXB13, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2, TP53 , and RAD51D. Additional genes may be important depending on the clinical context considering the patient’s personal and family history.

8. The minimum set of genes for genomic profiling of the tumor in patients with prostate cancer who meet criteria for tumor testing should include BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM; however, tumor testing panels should be aligned with germline testing panels as much as possible and ideally would also include CHEK2, EPCAM (large deletions), HOXB13, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2,TP53, and RAD51D.

CDK12 may also be included for prognostic purposes. Additional genes may be included for research purposes, prognostic purposes, or inclusion of patients in clinical trials.

9. All patients with de novo metastatic prostate cancer should have a biopsy performed so that tissue is available for next-generation sequencing, to determine candidacy for PARP inhibitors in the future.The biopsy should be performed as early as possible relative to the start of therapy, without compromising the care of the patient.

10. A tiered approach is recommended for the choice of specimen for genomic profiling of the tumor:

a. The first choice of specimen is an archival primary or archival metastatic tumor biopsy.

b. If archival tissue is not available or testing fails, alternate choices are a contemporary metastatic tumor biopsy or “liquid biopsy” for testing of plasma-derived ctDNA.There are advantages and disadvantages to both options.

Urinary stones are a very common disease that causes patients to suffer due to its painful symptoms and the repeated surgical procedures necessary to remove stones from the urinary tract. In some cases it can cause renal failure and, albeit rarely, mortality.

A panel composed of general practitioners (GPs) and academic and hospital clinicians expert in the treatment of urinary stones met with the aim of identifying the activities that require the participation of the GP in the management process of the kidney stone patient.

E pid E miology of urolithiasis in i taly

In Italy the prevalence of urinary calculi ranges between 1.7 and 7.5%; the prevalence was higher in males (4.53% versus 3.78%).

Higher rates of presentations for renal colic were observed when temperature was > 27°C and relative humidity > 45%

Renal colic occurs with a circadian rhythm which has a peak in the early morning and a minimum in the afternoon. Some studies have demonstrated the correlation between urinary stones and some chronic diseases such as arterial hypertension and osteoporosis

rEcurrEncE

Urinary calculi tend to recur. After 7 years from the first stone episode 27% of patients presented one or more recurrent episodes.

Urinary stones are classified according to:

• Etiology and composition,

• Site,

• Size,

• Radiological characteristics.

According to etiology they can be divided into:

• Stones from infectious causes (UTI),

• Stones from non-infectious causes,

• Stones from genetic defects,

• Drug-related stones (allopurinol, ceftriaxone, quinolones, sulfonamides, acetazolamide, topiramate, furosemide, laxatives, excess of vitamin D or calcium supplements between meals).

Calcium oxalate stones are the most common. The main metabolic abnormalities associated with calcium oxalate stones are:

• Hypercalciuria (30-60%),

• Hyperoxaluria (26-67%),

• Hyperuricosuria (15-46%),

• Hypomagnesiuria (7-23%) and

• Hypocitraturia (5-29%).

Calcium phosphate stones can present as carbonate apatite which can be associated with urinary tract infections (UTI) or brushite which crystallizes in the presence of high concentrations of calcium and phosphate, regardless of UTI. Possible causes of calcium phosphate stones include hyperparathyroidism, renal tubular acidosis, and UTIs.

Calcium stones can be secondary to some specific pathologies including primary hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, primary hyperoxaluria, enteric hyperoxaluria, distal renal tubular acidosis.

Uric acid stones account for 10% of kidney stones and have a high risk of recurrence. They are mainly caused by undue low urinary pH, decreased excretion of ammonia in the urine (e.g. gout), increased endogenous production of acids (e.g. metabolic syndrome) or increased loss of bases (diarrhoea). Another risk factor is hyperuricosuria, secondary to dietary excess (high dietary intake of animal proteins), excessive endogenous production, myeloproliferative disorders, gout, drug intake (in particular chemotherapy, thiazides and loop diuretics) and tumor cell lysis or catabolic processes.

Ammonium urate stones are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all forms of kidney stones, and are associated with UTI or intestinal malabsorption, hypokalemia, and malnutrition.

Size of urinary stones is crucial for treatment planning. It is usually expressed according to the largest diameter and stratified in the following groups: up to 5 mm, 5-10 mm, 10-20 mm and larger than 20 mm. The size of the stones should be considered in association with stone location, presence and degree of hydronephrosis, clinical symptoms and signs.

According to their anatomical location stones can be classified as:

• Kidney stones,

• Ureteral stones,

• Bladder stones.

Renal stones can be further divided as upper, middle or lower caliceal stones and renal pelvic stones; ureteral stones as proximal, mid or distal ureteral stones. Different locations, in association with the other characteristics of urinary stones, require different therapeutic approaches. Stone location is associated with specific clinical presentation requiring a differential diagnosis.

Urinary stones can also be classified according to their radiodensity at plain abdomen X-ray (Rx) as radiopaque or radiolucent. Radiolucent are not demonstrated on X-ray.

Calcium oxalate dihydrate (COD) Cystine

Calcium phosphate

Non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) can be also used to classify stones according to their density, measured in Hounsfield units (HU).

Weakly radio-opaque and radio-lucent stones at X-ray can be well demonstrated on non-enhanced CT.

Urinary stones can present with different symptoms and signs.

Renal colic is a characterized by acute flank pain, often radiating to the groin, and associated with hematuria and dysuria.

Microhematuria and episodes of urinary tract infection associated with chronic low back pain and/or evening fever can also be associated with kidney stones. Asymptomatic urinary stones can be diagnosed during investigations for other pathologies.

The GP has a role in initial diagnosis and monitoring of patients with renal colic, management of analgesic therapy and prevention of obstructive and infectious complications.

The initial step is pain treatment: the first choice are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); opioids are more frequently associated with side effect as vomiting and stunning, and risk of dependence; antispasmodics are not suitable.

If pain is not controlled, the GP must advise access to the emergency room for further diagnostic investigations. Analgesic therapy has to be monitored in order to prevent digestive complications of NSAIDs (gastroprotection).

When pain is associated with fever , the GP should administer parenteral antibiotics plus antipyretics.

After the resolution of the acute symptomatology, the patient with ureteral calculi can be followed up with a treatment aimed at the spontaneous stone passage. The GP has a role in the management of expulsive and analgesic therapy and in the prevention of obstructive and infectious complications. Obstructive and infectious complications are renal failure, pyelonephritis, and urosepsis.

A moderate increase in water intake should be suggested. Observation or medical expulsive therapy should not be prolonged beyond 4 weeks.

Patients should be informed of off-label use of alphablockers (especially in young men and in women where use is not justified by concomitant benign prostatic hyperplasia) and of the side effects of alpha-blockers (anejaculation for tamsulosin and silodosin, syncope).

Uric acid stones can be dissolved with chemolytic therapy. Pure uric acid stones can be suspected in case of age onset > 50 years, male sex, and diabetes mellitus. Uric acid composition can be predicted from stone radiodensity on CT (HU < 500) and low urine pH values (pH < 5.2). Demonstration of the stone on ultrasound in the absence of radiopaque images on the abdominal X-ray may be an alternative to CT.

Undersaturation of the urine with respect to uric acid causes the dissolution of uric acid stones and can be achieved by alkalizing the urine with citrate or bicarbonate, increasing urine volume and reducing the excretion of uric acid (allopurinol).

The oral chemolytic treatment of pure uric acid stones with oral administration of alkalizing agents can be performed on the recommendation of the urologist or

nephrologist (or directly from the GP). The GP has a very important role in increasing treatment compliance and follow-up. The success of the therapy depends on the patient›s compliance which can be increased with self-measurement of urine pH several times a day and weekly checks to evaluate the diary of pH values and urine volumes. Stone size should be monitored frequently (every two weeks) until the stone has dissolved. Treatment should be ended after three months if the stone has not reduced in size.

The modern treatment of urinary stones is based on extracorporeal or endoscopic lithotripsy. Stone fragments are eliminated through the urinary tract or suctioned through endoscopic instruments. The GP must be aware of the complications that can arise in the post-operative period in the patient undergoing lithotripsy. The main complications are represented by infections/sepsis, obstruction of the urinary tract (hydronephrosis), and hemorrhage (for percutaneous lithotripsy).

Urinary calculi in pregnancy are a rare event which nevertheless requires careful management to avoid damage to the mother and the unborn child. Ultrasonography is the first-line method of diagnostic imaging in pregnant women. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a secondline procedure used to define the level of the obstruction and to visualize the stones.

Radiography and CT, due to the use of ionizing radiation, should be avoided

The recommended initial treatment is conservative with hydration and analgesics, if necessary, with the addition of antibiotics (56), since in 75% of cases there is a resolution of the symptoms and in 40-80% spontaneous expulsion. In symptomatic cases refractory to medical therapy or in the presence of infection or persistent obstruction, it is advisable to place a double J stent or alternatively a nephrostomy, under local anesthesia and if possible, under ultrasound control. However, both the stent and the nephrostomy are a potential risk of infection, and require periodic replacements, especially if the placement is performed in the first or second trimester of pregnancy. Therefore, some authors suggest performing a first-line rigid or flexible ureteroscopy as an effective procedure not burdened by obstetric complications. Despite the studies performed on some cell lines, the effects of shock waves on the fetus are not fully known at present and therefore shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) is not indicated during pregnancy and the reported cases generally refer to accidental treatments.

The GP has a role in patient monitoring, in the prevention of obstructive and infectious complications and in the management of analgesic therapy. The choice of analgesic therapy must be careful, avoiding NSAIDs, which are associated with pulmonary hypertension and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and codeine Paracetamol is an option (category B according to the FDA) for analgesic and antipyretic treatment. Morphine must be used in low doses and for limited periods of time (category C).

Beta-lactam antibiotics and fosfomycin are generally considered safe and effective in pregnancy. The use of fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines is not recommended.

gEnEral

All patients with kidney stones should follow general prophylaxis measures in order to reduce the risk of recurrence. General measures can be associated with a targeted pharmacological treatment based on the chemical-physical analysis of the stone in patients classified as high risk.

The GP has an important role in advising on an adequate diet and lifestyle.

A constant intake of at least 2.5-3 liters of liquids per day should be recommended to guarantee a diuresis of at least 2.5 liters of clear urine in 24 hours. The patient should prefer water intake.

Consumption of soda and sugary drinks is associated with a higher risk of urinary stones, while the intake of water, coffee, tea, beer, wine and orange juice are associated with a lower risk of urinary stones. The patient must be instructed to consume a varied and balanced diet, following the recommendations of Mediterranean diet.

Should be recommended:

• Increased intake of fruit and vegetables, at least 5 servings a day (alkaline content of the vegetarian diet increases the urinary pH)

• Avoiding intake of foods high in oxalate and vitamin C (especially in patients who show high oxalate excretion)

• Limiting the intake of animal proteins (maximum 0.81 g/kg of body weight)(as they favor hypocitraturia, lowering of urinary pH, hyperoxaluria and hyperuricuria)

• Not limiting calcium intake but ensure an intake at least equal to the daily calcium requirement of 1000-

1200 mg per day (to promote the formation of non-absorbable calcium-oxalate salts in the intestinal lumen and reduce intestinal absorption of oxalate)

• Not exceeding 3-5 g of sodium per day (as a higher intake is associated with increased calcium excretion, reduced citrate excretion and greater risk of sodium urate crystal formation)

• Limiting the intake of foods rich in purines (no more than 500 mg/day) in patients with hyperuricuric calcium oxalate and uric acid stones.

Adequate physical activity should be recommended. For adults over the age of 18, at least 150 minutes of moderateintensity physical activity per week, especially walking, cycling, or playing a sport at a non-competitive level is recommended.

Finally, the maintenance of a normal body mass index, i.e. less than 30 kg/m2 and correct control of blood pressure with systolic blood pressure values below 135 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure values below 85 mm Hg must be recommended.

In patients at high risk of recurrence, drug therapy should be considered.

Alkaline citrates (5-12 g per day) in case of calcium oxalate or uric acid stones.

Thiazide diuretics at a dosage of between 25 and 50 mg per day in case of oxalate and/or calcium phosphate stones (monitoring blood pressure, advising the execution of a densitometric examination and of periodic dermatological visits.

Magnesium at a dosage between (200 and 400 mg per day) in case of calcium oxalate stones associated with hypomagnesiuria or enteric hyperoxaluria (taking care not to induce diarrhea).

Allopurinol (100-300 mg/day) in case of uric acid or calcium oxalate stones associated with hyperuricemia/hyperuricuria or of ammonium urate stones (alternatively febuxostat at 80-120 mg/day).

Calcium supplements (up to 2000 mg) 20 minutes before meals in case of enteric hyperoxaluria, to reduce intestinal absorption of oxalate.

Tiopronine (800 and 2000 mg per day) in case of cystine stones, to reduce the urinary excretion of cystine, in combination with alkalizing citrates to increase the solubility of cystine (as a second-line drug to reduce the excretion of cystine, captopril at a dose between 75 and 150 mg).