10 minute read

AI IN CONSTRUCTION

An effective tool in trained hands

By Jay Summach, Key Account Manager, Amii (Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute)

Advertisement

Daily it seems, a new story makes the rounds about a computer doing a thing that nobody expected a non-human to be able to do — not in 2023, at least. A while ago, it was self-driving cars and computers winning game shows. Now, the conversation has swung towards large language models like ChatGPT and the bewildering range of home, school, and work tasks that they’re poised to retire from human to-do lists.

From 2015 to 2018, I served the ECA as director of education. During that time, I got to know hundreds of Edmontonarea companies that deliver world-class construction services and products. Our city has played a prominent role in the evolution of the global architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry over the last 100 years — and that’s evident in the high number of international companies that originated and continue to be headquartered here.

Today, I’m a key account manager with Amii, the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute. To the same extent that Edmonton is a construction town, Edmonton is an artificial intelligence town. Amii started 20 years ago with four founding researchers at the University of Alberta. Since then, thanks to partnerships with industry and strategic investment from the Alberta and federal governments, Amii has emerged as a global powerhouse in machine learning. Today, Amii funds the work of over 30 research fellows, plus a not-for-profit corporation of 75 specialists in putting machine learning to work for the industry.

My purpose in this article is to share what I see happening at the intersection of artificial intelligence (AI) and construction. The University of Alberta’s Construction Innovation Centre (CIC) offers a glimpse of where the construction industry is headed. There, collaborative teams of researchers, students, and industry partners are unlocking new methodologies, new tools, new materials, and new insights that will augment the capacity and competitive advantage of Canadian construction companies. More often than not, AI has a pivotal role to play in where we’re headed.

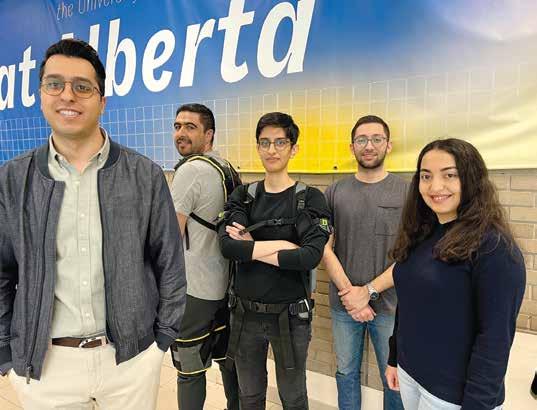

Dr. Ali Golabchi and members of the research team who are evaluating construction exoskeletons. These worn devices use elastomeric bands and springs to store or transfer energy from the user’s movements. Golabchi’s team applies sensors to collect data from test users — including range of motion, muscle activation, and user experience. This kind of data can be used to predict whether a particular kind of exoskeleton will reduce user fatigue in a particular worksite situation.

Before I introduce you to some of the projects underway at the CIC, here’s a short primer on what we mean by “artificial intelligence” and “machine learning”.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) AND MACHINE LEARNING (ML)

Artificial Intelligence refers to technology that can do things that, formerly, only a human could do. A smart speaker can understand what you’re saying, play the song you asked for, and follow it up with another song that you’ll probably like… that’s AI at work. AI is at work in most of our devices these days: it populates our social media feeds, it filters the spam from our inboxes, it suggests a faster route to our destination, etc.

AI came together as a science over 70 years ago at the intersection of computer science, mathematics, and philosophy. In 1950, Alan Turing published a paper titled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, in which he asks the question, “can computers think?” His key intuition was that if human intelligence comes from combining experience and reason, and if a computer has access to experience (that is, data) and reason (encoded as software), then computers ought to be able to “imitate” human intelligence. Turing was right — and 70 years later, it’s becoming tougher to distinguish the imitation from the real thing.

Machine learning (ML) is one kind of AI.

It refers to algorithmic methods — that is, sequences of step-by-step calculations — that enable computers to find and model the patterns in data, and to improve the models without the help of a human programmer. Decades of progress, on multiple fronts, have brought AI/ML to their current moment of breakthrough potential:

• Computer hardware is more powerful than ever, and simultaneously more affordable;

• Sensors have been developed to capture every conceivable kind of data, in increasingly fine detail;

• The amount of data stored on and off the Internet has grown to billions of gigabytes, representing an unprecedented repository of ‘experience’ for AI systems to learn from;

• New and improved methods of ML are enabling computers to tackle increasingly complex and creative tasks;

• Natural language processing (NLP) models like ChatGPT have made ML systems vastly more accessible to both technical and non-technical users.

Prediction Machines

Notwithstanding the fact that ML is being applied to a wide range of use cases, every ML model does essentially the same thing: it “predicts” the answer to one question. Simply put, an ML model is a “prediction machine”, to borrow the title of an excellent book by Agrawal, Goldfarb, and Gans.

Dr. Roberto Monroy is developing a platform for robotic sorting of plastics for recycling. Some aspects of the robot workflow are guided by computer vision. However, sorting must also be informed by the chemical composition of objects. Therefore, Dr. Monroy is working to integrate computer vision with infrared spectroscopy.

A lot of the workplace tasks that you perform include some element of “prediction”, in the sense of choosing a particular action because you predict that it will have a desirable outcome. Your ability to make good predictions comes from your training and experience. The more alternatives and outcomes you have been exposed to, the more accurate your predictions become.

Construction expertise is teeming with predictions. What fee should you quote for delivering this scope? How should you adjust the concrete mix, given the air temperature and humidity? Which laydown will minimize the need for reshuffling? Which design will optimize for requirements, cost to build, and cost to operate? Where is a safety incident likely to occur, and what action should you take to avoid it?

A ML model can lower the cost and greatly improve the accuracy and speed of predictions, especially in situations where the prediction must weigh multiple factors. As such, a good ML model can be an insightful, reliable, and cost-effective tool for the human who is ultimately responsible for decisionmaking. But before this can happen, two things must be true: the ML model must be developed around a single, precise question; and the model must be trained on a large volume of high-quality data that enables it to answer that question.

Everything Starts With Data

Dr. Ali Golabchi is associate director of the CIC. I ask whether there is one thing — above all — holding the construction industry back from leveraging ML technology. “Data,” he says. “There are lots of opportunities to collect data, and we aren’t doing it. On the other hand, the data we do collect is unorganized, inconsistent, or separated in silos — so that data goes unused. Managing data in a dynamic, complicated industry like construction is much tougher than it is in a controlled environment like manufacturing.”

Before a ML model can offer reliable predictions, it must be trained on relevant data, and a lot of it. A company can’t just summon data from thin air, if they haven’t collected it in advance. Sometimes, relevant data sets can be bought or simulated, but there are costs and limitations to what is possible. Depending on the predictions that a company has in mind, it can take months before the data is in place to begin training a ML model. But companies don’t have to do it on their own.

“To really make a difference, there has to be consistency in [data] formats and a willingness to share and work together. No single company can tackle this on their own,” Golabchi says. “That’s where an organization like the CIC can help. We can bring together industry expertise, industry data, industry funding, and government funding to support research that benefits everybody.”

Safety management is one of those activities where construction companies collect a lot of data. But by and large, that data goes unused because it is so *difficult* to use.

“Companies keep incident data in thousands of reports, but rarely analyze these to learn and prevent future incidents,” says Dr. Lianne Lefsrud, who co-leads a CIC project analyzing the influence and interrelationships of leading indicators in safety incidents. “We over-rely on our sight to identify hazards, and over-estimate our cognitive ability to understand them all.”

Lefsrud’s team pooled 15,000 incident reports contributed by industrial construction partners. Their initial challenge was to develop ML models capable of extracting and categorizing the information stored in the reports. That wasn’t a straightforward task. Although companies collect similar information in their incident forms, the forms themselves are highly variable in their formats, completeness, and accuracy. Some companies input their safety reports into well-structured digital forms; while other companies diarize information with pen and paper. Lefsrud’s team had to develop an automated system to deal with it all.

Once Lefsrud’s team was able to identify the leading indicators described in incident reports, they were able to get down to discovering patterns in the data.

“It’s never one thing that goes wrong, it’s three to five things,” she says. “You have a congested site, work at height, changing weather, and 40 per cent new workers on site.” The long-term goal of the project is a safety management platform that merges historical data with present conditions, to predict the likelihood and severity of hazards — and to recommend mitigations.

“We want to be able to tell a construction company ‘you have four things that are flagging, so take special care’,” says Lefsrud. “A superintendent with 20 years of experience will know this intuitively. But with the turnover in construction companies, that implicit knowledge is not necessarily in people’s heads. We need to translate that implicit experience into an early-warning system.”

Generative Ai

Whereas Dr. Lefsrud is using ML to make predictions based on worksite indicators, Dr. Ying Hei Chui and Dr. Qipei

Mei are applying ML to design decisions for prefabricated wood buildings.

“If a building component is going to be fabricated by a robot,” says Chui, “It may need to be designed differently, to make it easier for the robot to produce the component efficiently.”

Mei elaborates, “Design decisions have to be made at a very early stage, and cannot be changed without affecting the whole manufacturing process. We’re using AI to generate design options that consider later stages.”

But as is the case for safety managers, who are bombarded with more factors to consider than any human can reasonably manage, building designers must weigh myriad considerations.

“There are so many factors to consider,” says Chui. “You can’t just look at structural requirements and the cost of material. There’s manufacturing time. Installation time. Operational efficiency. You have to treat these things holistically at the design phase.”

Mei explains, “Currently, there’s a lot of back-and-forth between design and manufacturing. We’re trying to improve that link, to reduce the amount of backand-forth.”

Chui and Mei don’t see AI as sidelining humans in the design process. Here, as in many industry applications of AI/ML, the goal is a “human in the loop” system where ML augments human expertise.

“It isn’t easy to have structural design taken over fully by AI at this point,” says Mei. “Life and safety are at stake. But AI can assist human engineers, exploring many more design options than a human has time to complete.”

This Is A Great Time To Get Started

AI and ML are already delivering value for early adopters across the construction industry — particularly in areas like procurement, contract management, supply chain management, office process optimization, and in closed environments like manufacturing and research. But industry scans published over the last few years unanimously agree that construction lags behind other industries in taking advantage of AI. The moral of the story is that no company needs to feel like they’ve missed the boat. If you’re just beginning to explore where AI might lend you a competitive advantage, you’re in good company.

For companies that are new to thinking about AI, training is the essential first step. Speaking from his experience as an innovation enabler, Golabchi says “there has to be buy-in from top management, down through supervisors and workers… everyone needs to see the value in transformation.”

A 2023 article in the Harvard Business Review (HBR) reports that 80 per cent of Fortune 1000 executives cite “cultural impediments, not technology” as the greatest roadblock to their AI initiatives. In other words, if your C-suite, management, and field teams aren’t aligned on evolving into a data-driven business, it probably isn’t going to happen. (See Randy Bean, “Has progress on data, analytics, and AI stalled at your company?” HBR Jan. 30, 2023)

Amii offers a condensed ‘crash course’ to introduce your technical and nontechnical staff to the fundamentals of translating business opportunities into ML questions. The course is delivered in two half-day sessions, and led by one of our ML educators. Learn more and register at amii.ca/training.

Eventually, you’ll need to take carefully considered steps from dreaming to planning to doing. It’s wise to have an ML partner with industry experience who can help you identify a high-value, low-risk first project, so that you can build momentum and buy-in for your subsequent ML initiatives. You’ll also need to decide whether it makes the most sense to buy an off-the-shelf ML solution, or to partner with an ML vendor or organization like the CIC, or to leverage the project and expert coaching to develop your in-house ML capacity.

Amii specializes in the third approach, but there are pros and cons to all three options.

LET’S TALK!

Bit by bit, machine learning will transform the ways that construction projects are tendered, planned, designed, and delivered. There’s a technology pun in that last sentence, in case you missed it. If this article has piqued your interest, or convinced you that this is a good time to start a conversation, Edmonton is home to many qualified partners who can get you underway on your ML journey.

Learn more and get involved with Amii by visiting amii.ca, or by reaching out to me at jay.summach@amii.ca.

Learn more and get involved with the Construction Innovation Centre by visiting constructioncic.ca. u