6 minute read

Going Deeper

In Shift Lab 1.0 we learned from feedback that we might have fostered too much of a polite atmosphere, which hindered going deeper and sparking personal transformation. In Shift Lab 2.0 there were a number of tools we used to go deeper.

Indigenous Traditions iyiniw ihtwâwina

One of the important ways for going deeper was through Shift Lab steward Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse sharing Indigenous traditions. This included sitting together, listening more deeply to each other, feasting together and strengthening relationships. There was no set tool or method to follow for this, but we made space and centred these moments throughout the lab. Jodi also introduced the lab participants to going out on the land to recognize the interconnections in systems, pick berries together and carry questions together.

ispihteyihtakwan kakiskisihk ekwa kahâhkameyihtamihk kâkînakatamakoyahkik aniki kitaniskotapaninawak.

*It is important to remember and practice the ways of our ancestors.

Theory U

Another way we explored supporting teams going deeper was through the Theory U framework, developed by Otto Scharmer. This framework describes the journey of changemakers as working through multiple phases of discovery, beginning with “downloading” their own mental models of a complex situation and then gaining increasing insight through conversations, experiences and research with others. This (ideally) results in an openness to the emergence of new ideas about how to address the challenge.

Downloading Past Patterns

Seeing with Fresh Eyes

Sensing from the Field

Letting Go

Adapted from Otto Scharmer

OPEN MIND

OPEN HEART

Performing Scaling and Internalizing

Prototyping Experimenting with the New

Crystallizing Vision and Intention

OPEN WILL

Letting Come

Presencing Shift Lab 2.0

connecting to source

4 Types of Conversations Tool

We utilized Otto Scharmer’s four types of conversations that support how we talk together to create deeper understanding and cultivate richer insights. The four types of conversations framework creates the conditions for this by structuring dialogue accordingly. We endeavored to weave these ways of going deeper throughout the process.

Generative Dialogue

• presencing, flow • time: slowing down • space: boundaries collapse • listening from one’s

Future Self • rule-generating

Talking Nice

• downloading • polite, cautious • listening = projecting • rule-reenacting

Reflexive Dialogue

• inquiry • I can change my view • empathic listening (from within the other self) • other = you • rule-reflecting

Talking Tough

• debate, clash • I am my point of view • listening = reloading • other = target • rule-revealing

We Sought Behaviour Change, Not Nice Transformational Experiences

How might we create anti-racism interventions that acknowledge everyone’s humanity and create behaviour change?

From our overarching question, you can see that we wanted to move the needle to making an actual impact. Ideally, we all want system behaviours to change at the root. But along the way we at least wanted to work towards ways people, groups, and organizations could more easily learn how they can change behaviours to be less racist. A common thing we heard in our early research was that one-off transformational diversity or anti-racism training is great, but too often people snap back to their “normal” modes and don’t shift behaviour over the long term. We wondered and wanted to experiment with how we might improve that, or at least uncover principles that can improve lasting behaviour change.

The COM-B Model of Behaviour Change

We used the COM-B model of behaviour change, which is based on a synthesis of 19+ public health behaviour change models summarized by Michie, Atkins and West in the book, The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. This UK-based approach proposes that the direction, depth and pace of any kind of behaviour change — whether it’s quitting smoking, wearing seatbelts or recycling more — is shaped by three factors: capability, motivation and opportunity.

Capability is defined as the individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned. It includes having the necessary knowledge and skills to act.

Motivation is defined as all those brain processes that energize and direct behaviour, not just goals and conscious decision-making. It includes habitual processes, emotional responding as well as analytical decision-making. The Behaviour Change Wheel breaks motivation down into reflective and automatic categories.

Opportunity is defined as all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it. It is primarily broken down into physical and social categories.

The participants of Shift Lab 2.0 were introduced to this framework, and then asked to consider how all three factors might be integrated into their behaviour-change interventions. Many also used it to manage expectations about the direction, depth and pace of behaviour change and the extent to which we are able to effectively address all three factors (e.g., an intervention that focuses only on capability will only be useful in situations where motivation and opportunity already exist). Restrictions

CAPABILITY Env ironmental Res tructur ing M o d el l i n g Psychological Automatic Physical

Education OPPORTUN I T Y Persuasi on I n c e n t iv isa t ion Social Physical MOTIVATION Training Enablement Coercion

Mayne, John. 2018. The COM-B Theory of Change Model. A Working Paper.

Behaviour-Change Nudging

We also explored how we might remix behaviour-change nudging into the prototypes to help with positive behaviour change. In the process, we created a deck of prompt cards (called our Shift Lab Behaviour Change card deck) with principles from behaviour change science. Teams used the cards to see how they might design ethical behaviour-change nudging into possible prototypes.

Types of nudges

“Nudges” are small changes in the environment or interactions that are easy and inexpensive to implement. These nudges are gleaned from the worlds of social psychology and marketing. Several different techniques exist for nudging, including defaults, social proof heuristics, and increasing the salience of the desired option.

A default option is the option an individual automatically receives if he or she does nothing. People are more likely to choose a particular option if it is the default option. For example, Daniel Pichert & Konstantinos Katsikopoulos noted in the Journal of Environmental Psychology that a greater number of people chose the renewable energy option for electricity when it was offered as the default option.

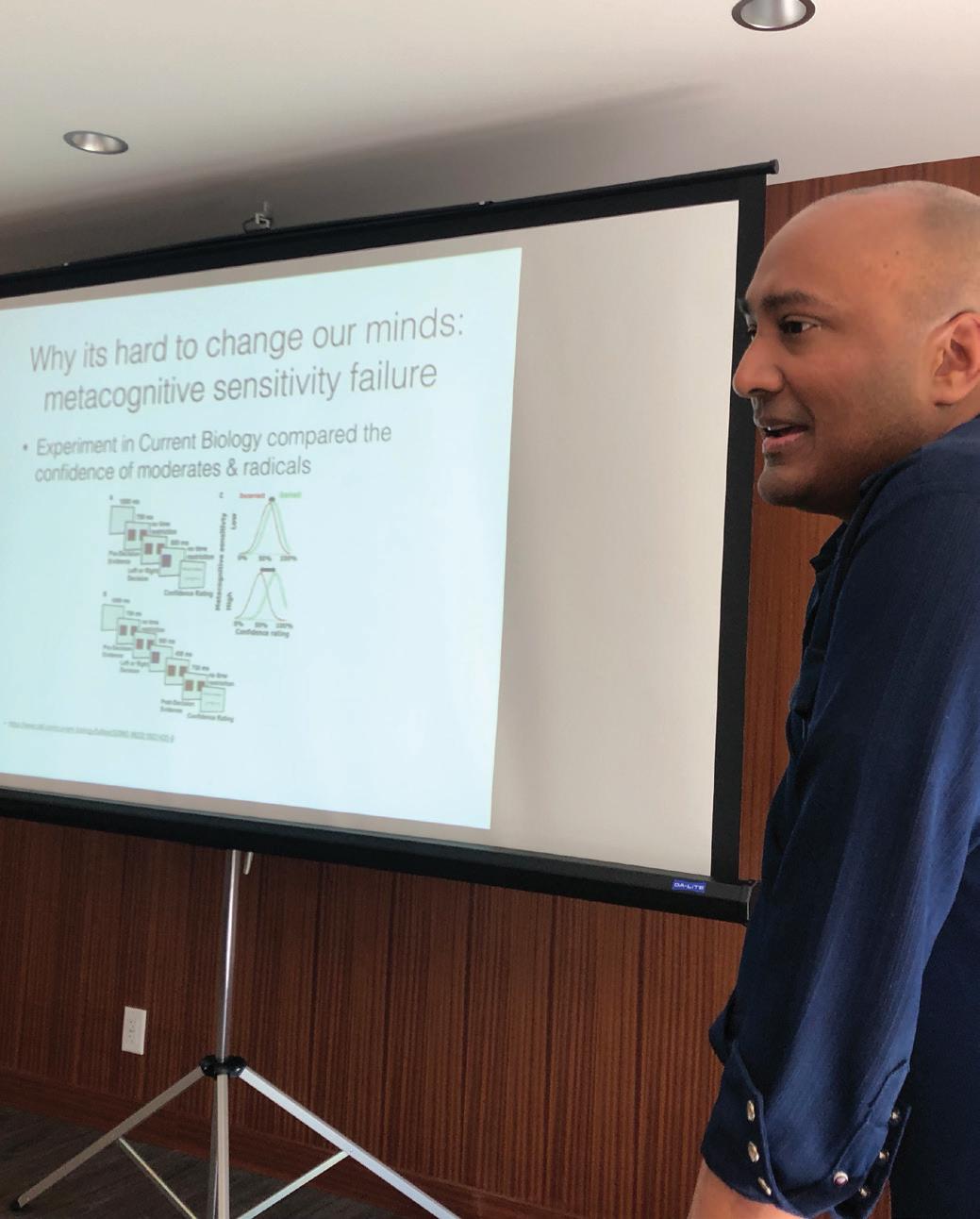

Steward Sameer Singh sharing insights on behaviour change science

A social proof heuristic refers to the tendency for individuals to look at the behaviour of other people to help guide their own behaviour. Studies have found some success in using social proof heuristics to nudge individuals to make healthier food choices. When an individual’s attention is drawn towards a particular option, that option will become more salient to the individual, and he or she will be more likely to choose that option. As an example, in snack shops at train stations in the Netherlands, consumers purchased more fruit and healthy snack options when they were relocated next to the cash register.

“The words ‘If people would just…’ are never a part of an effective social innovation. If your goal is to create social change through behaviour change, strong arguments will rarely suffice. You must also understand people’s behaviour and design solutions that disrupt their habits.” — Ben Weinlick on the MyCompass Planning Social Innovation

“A nudge, as we will use the term, is something that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.” — Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness_ by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein