CLASSICS

A Stolen Meeting (1988)

Estonian Psychedelic Animation from 1970s

What Happened to Andres Lapeteus (1966)

Documentaries by Andres Sööt

The Misadventures of the New Satan (1964)

Corrida (1982)

A Woman Heats the Sauna (1979)

Estonian Film Classics is a special edition of the Estonian Film magazine published by the Estonian Film Institute ISSN-2585-674X Estonian Film Institute Uus 3, 10111, Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 627 6060 E-mail: film@filmi.ee filmi.ee

The Estonian Film Institute’s Film Heritage Department manages all the films made in the legendary Tallinnfilm studio during the years 1941–2001. In this catalogue, we proudly present some of that great legacy – a carefully curated selection of five distinctive feature films, a selection of animated films, and documentaries by Andres Sööt.

A Stolen Meeting (1988) was the seventh and last film by director Leida Laius (1923–1996), completed on the threshold of Estonian re-independence and during the Singing Revolution in 1988. In addition to the fate of women, the film also highlights themes of rootlessness and migration.

Andreas Trossek, art historian and critic writes about psychedelic Pop Art influenced animated films made in 1970s Estonia. Within the official cinema circles of the Soviet Union, animation was mainly targeted towards toddlers, young children, and teenagers. In Estonia, on the other hand, the artists had clearly used child-oriented cartoons as a means of artistic expression, and experimented with the possibilities of the film medium in general, and these selected films appear as fragmented manifestations of post-Second World War youth culture that also filtered into the 'wrong side' of the Iron Curtain.

What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? (1966) is the first domestic film to try and analyse the heritage of the Stalinist personality cult, and its influence on communist society. What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? was a remarkable work that has successfully stood the test of time, and acquires more and more layers of meaning in our current conflicted atmosphere of the first half of the 21st Century.

Johannes Lõhmus introduces Andres Sööt, the master of Estonian docu-

mentary, whose sharp gaze has chronicled our life through good and bad, in the spins and swirls of history.

The Misadventures of the New Satan (1964) is co-directed by Jüri Müür and Grigori Kromanov. It’s a film where metaphysics and Estonian literary classics meet. The Misadventures of the New Satan is the last novel by Anton Hansen Tammsaare, the greatest writer of Estonian literature. By some miracle, this film with a deeply religious and philosophical subtext was shown all over the Soviet Union and became the first significant success in Estonian film history.

Corrida (1982), a psychological drama by Olav Neuland, reflects Estonian cinema in the beginning of the 1980s when the Soviet Empire started to show the first signs of deterioration.

Arvo Kruusement, one of the most beloved directors in Estonia whose feature film Spring has repeatedly been selected as the best feature film of all times in Estonia, released A Woman Heats the Sauna in 1979. In that period only films that reflected events that took place in either a historical or fictional past went into production. A Woman Heats the Sauna is a rare film that actually takes place in the present – in Soviet Estonia in the 1970s.

The seven articles in this booklet are all very different, both in content and style, introducing different films, but there is one thing that unites them all –Estonian culture and film history would not be the same without them. Enjoy the following in-depth texts, the films, and if you have any questions regarding Estonian film heritage, feel free to contact us at the Estonian Film Institute. EF

RAIN PÕDRA Head of Film Heritage Department

4 A Stolen Meeting

10 Pop Art in Animation

Classics Contents

16 What Happened to Andres Lapeteus A Downward Spiral

22 Documentaries by Andres Sööt A Man with a Movie Camera

28 The Misadventures of the New Satan The Satan Came to Earth

34 Corrida Love Island

40 A Woman Heats the Sauna A Genuine Reflection of an Era

Editors: Eda Koppel, Maria Ulfsak, Triinu Keedus, Sigrid Saag

Contributors: Johannes Lõhmus, Annika A. Koppel, Andreas Trossek, Tõnu Karjatse, Jaak Lõhmus

Translation: Tristan Priimägi, Lili Pilt, Maris Karjatse

Linguistic Editing: Paul Emmet

Design & Layout: Profimeedia

Printed by Reflekt

EF CLASSICS 3

A Stolen

CLASSICS

Meeting

The year 2023 saw the celebration of the 100th birthday of one of Estonia’s all-time greatest directors, Leida Laius. All of her films are considered classics in Estonian cinema. Annika A. Koppel analyses

Leida Laius’s last feature film, A Stolen Meeting

By Annika A.

Koppel Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

AStolen Meeting was the seventh and last film by director Leida Laius (1923–1996), completed on the threshold of Estonian re-independence and during the Singing Revolution in 1988. In addition to the fate of women, a recurring theme in Leida Laius’s films, the film also highlights themes of rootlessness and migration.

As several hundred thousand Russians had migrated and been resettled in Estonia during the Soviet occupation from 1944–1991, the film’s theme was painful and timely. But it wasn’t until the 1980s, when the Soviet regime started to weaken, that people began to speak about it openly. There was actually another film made by Tallinnfilm in 1988 that tackled the theme of migration – Peeter Urbla’s I Am Not a Tourist, I Live Here, which also addressed problems in society caused by massive immigration and lack of housing.

In A Stolen Meeting, Leida Laius continues to talk about children in orphanages, a theme familiar from her previous film Smile at Last (1985). In fact, she introduced this theme much earlier with her documentary films A Human Is Born (1975) and Childhood (1976). A Human Is Born shows a child’s birth, which is a special and happy event, but which also brought the director in contact with mothers who left their babies behind at the hospital. Childhood is a sad film about small children who spend days or even weeks away from their mothers and homes, whether in daycare or even overnight care. That is because there was a time when Soviet women had to return to work a few months after giving birth and had nowhere to leave their children. Director Leida Laius interviewed childcare workers who found that daycare and overnight care are no replacements for a mother. At the time, this was a bold

The protagonist, Valentina (Maria Klenskaja, on the right), is Russian but grew up in an Estonian orphanage so she doesn’t know where she’s from. On the picture with Marta Toomingas (Leida Rammo).

topic to tackle. Childhood was banned and left to gather dust on a shelf because it was critical of how hostile and inhumane the Soviet system was towards mothers and children. Taking this subject on reveals the director’s strongly socio-critical attitude.

THE SCRIPT, THE CONTEXT AND THE PROTAGONIST

The cast includes Estonian top actors(from the left) Kaie Mihkelson, Lembit Peterson, Sulev Luik, Maria Klenskaja.

The script for AStolenMeeting was written by Moscow playwright Maria Zvereva. It was initially supposed to be made in Moscow, but was put on hold and not considered suitable. But the significant social changes that were taking place made it possible to start talking about topics that were previously avoided, so it could be made by Tallinnfilm. Leida Laius was interested in the script

EF CLASSICS 6

CLASSICS

but, of course, it had to be adapted as it didn’t make sense to film it in Siberia, the original location for the events. The main character in the film, Valentina, is thus born in North-Eastern Estonia in the oil shale mining region where the largest number of Russians were resettled in Estonia.

The protagonist, Valentina (Maria Klenskaja), is Russian but grew up in an Estonian orphanage so she doesn’t know where she’s from. The film begins when she is released from prison in Russia and starts to look for her son. Valentina wants her child back. The thought of her son left behind in Estonia helped her survive the prison sentence. She embarks on a journey to find her son and win him back. Along the way, it becomes clear who she really is and where she comes from. The film explores not only her external journey but also her internal journey, and how society and her upbringing have influenced her. Valentina is both a victim and a culprit, but also a woman who longs for love and has a right to it like any other human being. But does she have any hope of finding it?

In the train as she is coming back from prison, Valentina meets an old acquaintance named Roma, whose life is probably even harder than Valentina’s. He suggests they keep going together but she has decided to find her son. Valentina wants to discard her old life just like her outdated clothes that find their way into a trashcan.

It turns out that Valentina’s son was adopted by an intelligent family of doctors in Tartu. Her son Jüri is played by Andres Kangur who provides a magnifi-

LEIDA LAIUS

was born March 26, 1923 in the village of Horoshevo near Kingissepp (formerly Jamburg) and died in 1996 in Tallinn.

1940 – Volunteered for the Red Army to work as a medic and librarian.

1950 – Graduated from the Estonian SSR State Institute of Theatre.

1951 – 1955 an actress at the V. Kingissepp Drama Theatre RAT.

1955 – Entered the directing program at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), which she successfully completed.

1960 – Began working at Tallinnfilm studio.

Filmography: 1962 short film From Evening to Morning, graduation film 1965 The Milkman of Mäeküla 1968 Werewolf 1973 Ukuaru

1979 The Master of Kõrboja 1985 Smile at Last with Arvo Iho 1988 A Stolen Meeting

Documentary Films: 1975 A Human is Born 1976 Childhood 1978 Tracks on Snow

Also the posters for A Stolen Meeting are quite remarkable. Both are designed by Estonian graphic designer Ülo Emmus.

cent performance. Jüri’s wisdom and understanding are on an adult level. Kangur must have been a remarkable child and he was great find for the director. Sulev Luik also plays a very interesting role as Uibo, the man who Valentina decides to seduce in a plan that ultimately fails. Her saddest encounter is with a former teacher, an old woman still living under Stalin’s portrait whose teaching has shaped young people. It turns out that Valentina ended up in prison not because of what she did but because of the actions of her son’s father. Perhaps she was complicit, but she remained silent and never had him arrested. Maybe because of her generosity or fear, or both.

There is a particularly sharp contrast in the film between the garish conditions in the mining region dorms where Valentina grew up and the doctor’s peaceful, cosy Estonian family home in Tartu. This emphasizes Valentina’s lack of roots. She has nowhere to go and no one to rely one. She is alone and doesn’t belong anywhere.

MARIA KLENSKAJA’S TRIUMPH

The ending of the film reflects all this emptiness, as Valentina understands that she has no opportunity to provide a home for Jüri and it’s better for the boy to

EF CLASSICS 7

grow up in a safe environment. So, she has to disappear. “Don’t write, I have no address.”

Valentina’s role was a challenging and excellent achievement for actress Maria Klenskaja. She is outwardly bold, sometimes pleasant, but then repulsive and inwardly tense and brittle, while remaining a woman who longs for love and understanding. She just doesn’t know how to be a mother, or how to behave, because she never experienced it and was never taught how. And, of course, society offers her no compassion or opportunities for development. Life is simply very harsh and tough towards her. Through her meetings with her son’s father, an old friend, a former teacher, and others, Valentina’s tragedy gradually emerges – even when life presents her with an opportunity, she is not capable of making the best of it and still goes down the path of habit that inevitably leads to problems. But as a person, she longs for love, warmth and a home. And her tragedy is her inability to achieve any of those things.

Maria Klenskaja plays the emotional tones and character’s internal development superbly. Her face reflects Valentina’s alternating hope and despair, weariness and enthusiasm, and she lies skilfully to achieve her goals, or simply out of habit.

Journalist and lecturer Aune Unt wrote this about the film: “Where do you find support if you have no

Ukuaru or Kõrboja1, if you don’t even where or how to create a home? Here, in the bleak industrial city where stunted and bare trees have been left to dry in the ground. These trees are a symbol that starts to form an unexpected and gruesome monument to Stalinism in the film: the buildings characteristic to the 1950s, rows of dry, stunted trees and Valentina approaching like a homeless cat. /…/ But this is Valentina’s home, the land of bleak orphanages and repulsive dorms where a trashy lifestyle and a migrant way of living and thinking know no national boundaries. Over time, the concept of home in a person either shrinks or becomes an obsessive delusion that eats away at them from the inside and drives them to steal.” .“2

Actress Maria Klenskaja has recalled: “After the film was completed, there was an actors’ festival in Kalinin. I was there at the beginning, translating the film. But then I got sick and had to leave. When Leida found out that I was going to receive the award for Best Actress, she called me in the morning and said, “You’re going.” I was in a play about Mary Poppins that was just about to premiere so I didn’t want to take the trip. But then Leida told me in a very specific tone of voice: “Remember, you are not going there to represent yourself, but Estonia!” The year was 1989. And when Lembit Ulfsak and I returned from the festival, then guess who was there to greet us? Of course, it was none other than Leida, herself, waiting at the airport with flowers.”3

Almost all of Leida Laius’s films stand out for the strong acting performances, and not only in the lead roles. She knew how to get both experienced actors as well as beginners or amateurs to play brilliantly in her films. Her own prior acting education probably helped her understand and work with actors. She went to study directing at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow at the age of 32, when she had already been working in the theatre. Actors have recalled how much Laius supported and appreci-

CLASSICS EF CLASSICS 8

Valentina's son Jüri is played by Andres Kangur who provides a magnificent performance.

Actress Maria Klenskaja (on the left) and director Leida Laius working on the set.

1 The farms found in Leida Laius’s previous films.

2 Aune Unt. “Leida Laiuse uus film”, Edasi 29. jaanuar 1989.

3 Annika Koppel. “Hilinenud kohtumine Leida Laiusega”, Elu Lood, talv 2014.

ated them, the attention she gave them and the work she did with them, which sometimes seemed unnecessary at the time. As young actors, they may not have been able to appreciate this approach as they were still struggling with themselves and their surroundings, but they later began to understand its importance. Leida Laius was a very thorough, dedicated and uncompromising director and she expected the same from others.

Maria Klenskaja has also recalled that Leida already had health problems during the shooting period for A Stolen Meeting because once when she went into Leida’s room, she saw a lot of pills scattered on the table. Leida wouldn’t let her talk about it so the crew knew nothing of her problems. But she took care of everyone else.

THE RECEPTION

A Stolen Meeting was received well in Estonia and internationally. Smile at Last already screened at the Créteil Film Festival, and A Stolen Meeting was also selected to screen there. There was discussion of organizing a retrospective of her work in France, but unfortunately Tallinnfilm did not have the funds to organize it. In addition to France, Laius also travelled to the United States with A Stolen Meeting for the Women in Film Festival held in Los Angeles where she received the Grand Prix – the Lilian Gish Award. These were important moments for Leida Laius as a director when there was a buzz around her and her work was highly appreciated. She was 65 years old at the time.

It’s sad that there wasn’t much else coming up for Laius after that. Even though Estonia’s re-independence and the period of great change also brought a lot of enthusiasm, the monetary reforms caused people to lose their savings, life was difficult, and there was a shortage of everything. Leida Laius did finally receive the Lifetime Achievement Award from the

National Cultural Fund in 1995, but she did not have much time to enjoy it as she passed away a year later.

In some ways, the themes of a woman’s life and development in Laius’s films are universal and comprehensible to people all around the world. Her work vividly reflects the development of Estonian film art. Laius was a strong player in the masculine film world of the time. Now, as women’s voices are being heard more and more, and work by women directors is appreciated, her work becomes even more relevant. We can be proud that Estonia had a director like Leida Laius during the difficult Soviet era, someone making films that stood the test of time despite her circumstances. All of her seven feature films and three documentaries are high quality works, some more than others. But her place in Estonian film history is secure and, over time, her artistic achievements will start to shine even brighter.

In 2012, Leida Laius’s film Smile at Last was restored and in 2023, a 4K version was made of A Stolen Meeting. The film was digitized from a 35mm film print, which is stored in the film archive of the National Archives. The restoration was made possible through the support of the European film archive association ACE (Association des Cinémathèques Européennes) programme A Season of Classic Films, which is part of the European Commission’s Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. EF

Legendary cinematographer Jüri Sillart in action.

Legendary cinematographer Jüri Sillart in action.

In some ways, the themes of a woman’s life and development in Laius’s films are universal and comprehensible to people all around the world .

CLASSICS POP

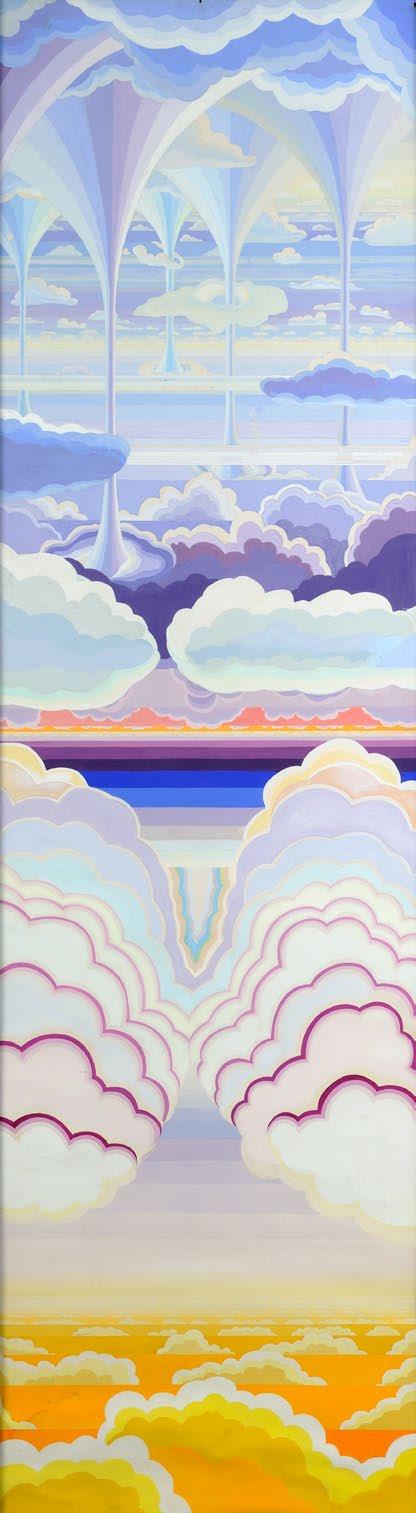

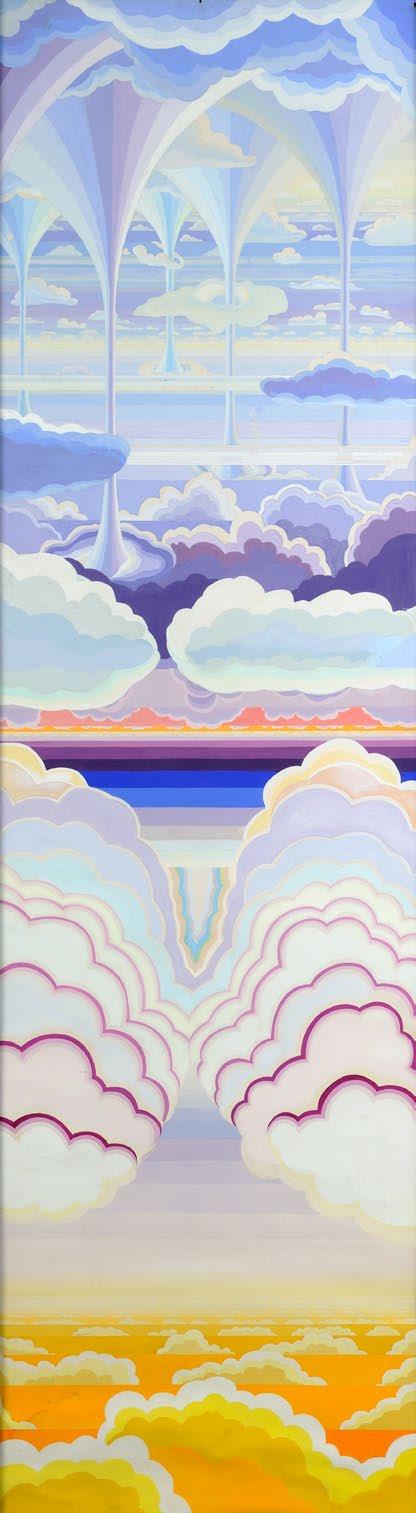

Backgrounds II for the animation The Flight (1973)

Artist Aili Vint

10

Photo by Stanislav Stepashko

/ The collection of Art Museum of Estonia

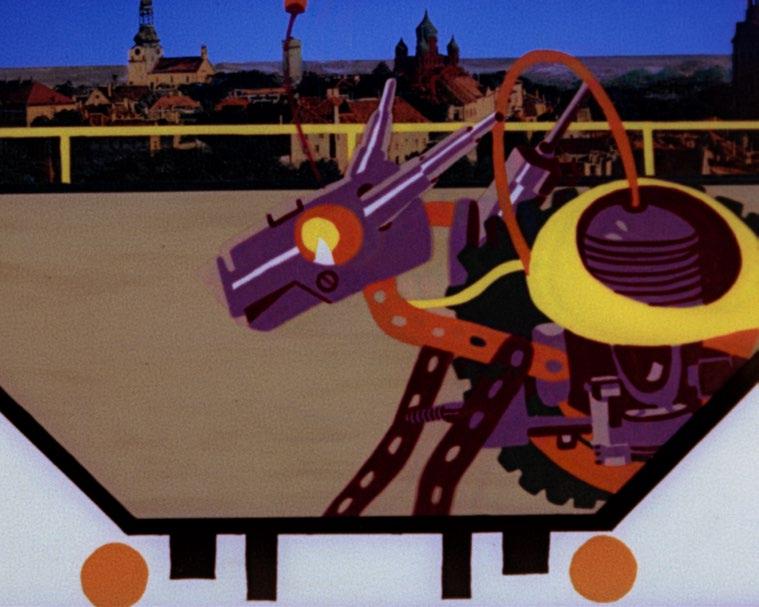

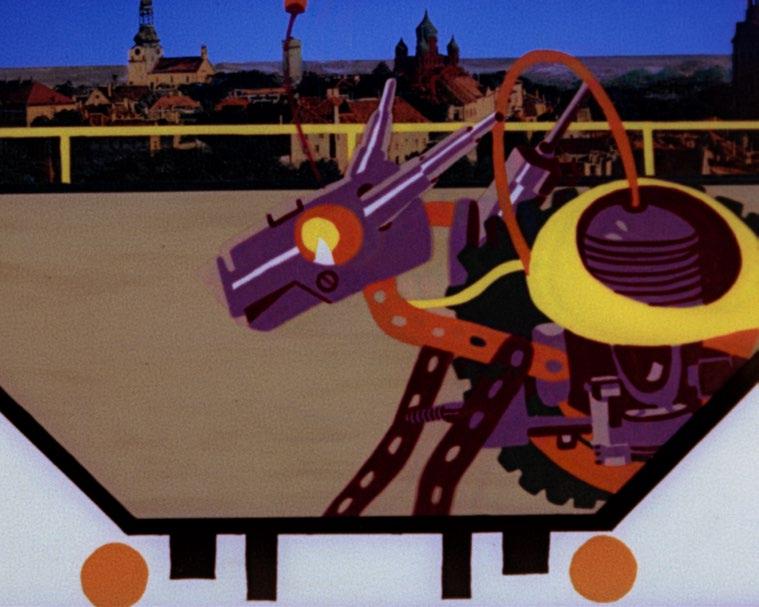

Avo Paistik, Vacuum Cleaner (1978)

Ando Keskküla, Rabbit (1976)

ART animation in

Andreas Trossek, art historian and critic, who works as editor-in-charge of Estonian art quarterly Kunst.ee, writes about psychedelic animation from Estonia.

By Andreas Trossek Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

By Andreas Trossek Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

When the Second World War ended, Estonians found themselves on the 'wrong side' of the Iron Cur-

tain, and no longer part of the free world. Surprisingly though, we can talk about a number of psychedelic Pop Art influenced animated films made in 1970s Tallinn.

Back then, Tallinnfilm was the main republic cinema production studio of the Estonian SSR, both funded and ideologically controlled by the Goskino, the USSR State Committee for Cinematography. Throughout the 1970s, a generation of Estonian neo-avant-garde artists who were influenced, among other things, by Pop Art (and also by The Beatles' famous

Yellow Submarine animated feature from 1968) were actively engaged in the process of making hand-drawn animated films. Although artists such as Aili Vint (b. 1941), Leonhard Lapin (1947–2022), Sirje Runge (b. 1950), Ando Keskküla (1950–2008), Rein Tammik (b. 1947), Priit Pärn (b. 1946) and also the background artist Kaarel Kurismaa (b. 1939) need no introduction in Estonia today, their first youth culture oriented experimentations in the field of animation have often been overlooked. However, it is clear that

EF CLASSICS 11

Rein Raamat, Colourbird (1974)

quite a few animations from the 1970s rightly belong to the art historical framework of Soviet Estonian Pop Art, or 'Soviet Pop' as this localized version of Pop Art is often referred to.

POP… POP? POP!

In the 1990s, when local art historians were finally able to make attempts to write an honest and de-Sovietized art history, a certain positive quality of 'Pop-likeness' emerged in their texts about postwar Estonian art. It enabled to present some Soviet-era artworks as atypical and put them in opposition to the dominant paradigm of Social Realism. In retrospect, the key-members of the artist groups ANK '64 (Tõnis Vint (1942–2019), Aili Vint (b. 1941), Jüri Arrak (1936–2022), Malle Leis (1940–2017) et al), Visarid (Kaljo Põllu (1934–2010), Rein Tammik et al) and SOUP '69 (Ando Keskküla, Andres Tolts (1949–2014), Leon-

hard Lapin et al) could be considered to be importers and modifiers of many focal trends of the 20th century art, such as Pop Art, Op Art and Conceptualism, which at that time, in the 1960s and 1970s when they were young art academy graduates, represented ideologically disapproved 'Western tendencies' within the cultural apparatuses of the Soviet Union. Quite many of those young artists were also connected with Tallinnfilm's cartoon animation unit, which was established in 1971 under the leadership of Rein Raamat (b. 1931), a professional portrait painter himself. It can even be suggested that hand-drawn animation became sort of a problem-free 'test site' for those artistic ideas that couldn't be fulfilled in the public/official art arena of the Estoni-

CLASSICS

EF CLASSICS 12

Pop flavoured and at times psychedelic imagery didn't cause too many problems with cinema authorities.

Rein Raamat, The Flight (1973)

Rein Raamat, The Flight (1973)

Rein Raamat, Colourbird (1974)

an SSR. Animation as a relatively peripheral field of cultural production functioned as a new and empty niche, which stood both between and outside the official hierarchies of 'high art' (i.e. Soviet Realism). Pop-flavoured and at times psychedelic imagery didn't cause too many problems with cinema authorities, which, on the other hand, would have been inevitable in the case of a public art exhibition.

As a result, instead of official exhibition spaces, a significant number of individual aesthetic programs loaded with Pop imagery and colourful psychedelic vibes were in fact successfully carried out in the public space, although in a rather peculiar media – in animation films that were officially targeted at children. These new and weird films were screened in local cinemas and later occasionally shown on television, embedding themselves into the minds of many children… and also art-loving young adults.

HOW TO MIX ART WITH ANIMATION

In 1972 Rein Raamat, a former feature film production designer at Tallinnfilm studio (and who, by the way, had also been engaged in the process of making the first Estonian puppet-film in 1958, Elbert Tuganov's (1920–2007) Little Peter's Dream), directed his first handdrawn animation. It was called The Water Carrier (1972). However, making humorous cartoons mostly for children was not exactly what Raamat wanted to do in the long run. He had a painter's diploma himself, and already the third release of the studio, entitled Flight (1973), featured trendy background art with Op and Pop references by the young painter Aili Vint (a member of ANK ´64).

The soundtrack of the film was created by Rein Rannap (b. 1953), a founder of the legendary Estonian rock group Ruja, and in hindsight Flight could indeed be interpreted also as a music video or an abstract promotional clip. It was as close as you could get to 'yellow-submarine-sque' aesthetics in

the Soviet Union at that time. The film proved to be successful, receiving an international festival award from Zagreb, and Raamat continued the pattern of hiring young ambitious artists in order to achieve a contemporary and upto-date visual effect.

Raamat's next film, Colourbird (1974), was, in contrast, somewhat a failure in the eyes of the film authorities in Tallinn because the artist-architect Leonhard Lapin (a member of SOUP '69) and his then-wife Sirje Lapin (now Runge) were more concerned with the rare possibility of exhibiting the aesthetics of Pop Art, rather than actually illustrating the storyline of the film. However, due to Raamat's cunning diplomacy, the film was approved in Moscow without problems – Estonian animation had simply acquired a good reputation. The rocking soundtrack was once again delivered by Rein Rannap.

To this day, it remains as a powerful testament of the fact that the hippie generation artists made no compromises – the result is rather schizophrenic to its core, falling between the categories of an experimental 'underground' art film and an educational short oriented for toddlers (teaching them primary colours). Colourbird was undoubtedly one of the most powerful manifestations of Pop Art aesthetics within the public space of the Estonian SSR in the early 1970s.

Raamat turned to less visually experimental solutions with the cartoons The Gothamites (1974) and A Romper (1976), which are noteworthy for their morally ambivalent types drawn up by Priit Pärn, already a celebrated caricaturist who later became highly regarded internationally in the world of animation. The background colours were by Kaarel Kurismaa, a pioneer of Estonian kinetic and sound art.

The new 'Pop Art paradigm' was continued in the directorial works of Ando Keskküla (also a member of SOUP '69), at the time a well-known young 'metaphysical realist' in official artistic circles whose paintings truly brought Hyperrealism or Photorealism to the Estonian SSR. A Pop Art influenced design by Rein Tammik (a member of Visarid) was openly expressed in Keskküla's The Story of the Bunny (1975), whereas Rabbit

EF CLASSICS 13

Ando Keskküla, Rabbit (1976)

Ando Keskküla, Rabbit (1976)

(1976) was visually a much more mechanically 'colder' mixture of Pop Art, Hyperrealism, and photography.

The music in the first film was composed by Rein Rannap once again, while the soundtrack for the second film was by Lepo Sumera (1950–2000), whose symphonic approach in the end of the films sounds rather psychedelic. In The Story of the Bunny, animated and documentary footage were fused together, so in the end the imagery 'jumps' from a cartoonish style into a photographic register. In Rabbit rotoscoping (the process of creating animated sequences by tracing over live-action footage frame by frame) was used. Thus it could be summarised that as a director, Keskküla was interested in the same effect that attracted him in (Photorealist) painting: a system in which the imaginary and real were put into a conflicting situation.

After Keskküla left animation for painting, Tammik gave another Pop Art/Hyperrealist look to Avo Paistik's Vacuum Cleaner (1978). The outcome was the second Esto -

nian hand-drawn animation that outraged Goskino, and it was forbidden to show it outside the Estonian SSR. The story is about a red (sic!) vacuum cleaner, which starts swallowing up or destroying everything around it, growing bigger by the minute. Rotoscopic aesthetics in combination with the (possible) political allegory proved to be too scary for a screening permit in other parts of the USSR. A year earlier, the directorial debut of Pärn, Is the Earth Round? (1977), was also limited to republic screens because it was deemed too pessimistic at Goskino.

Pärn as a caricaturist was influenced by Pop Art indirectly, yet thoroughly, and that is most visible in his artistic design for Paistik's Sunday (1977). As if in tandem with Pärn, Kurismaa was once again included as a colourist. In theory this film was a critical sci-fi collage on the topic of the future of consumer society, but in practice the outcome was much more ambivalent and 'yellow-submarine-sque'. According to the archive documents, the target

group of this animation was eventually limited, excluding young children (sic!).

The soundtrack of the film heavily borrowed from Pink Floyd's popular LP The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). This music got into the film, one could say, as a result of a 'work accident': the film's sound operator had recommended sampling Pink Floyd's music after the director refused to use the work by the contracted composer, but the film still had to be finished according to the deadline.

However, the most famous Estonian composer today, who actively worked in animation in the 1960s and 1970s, is undoubtedly Arvo Pärt (b. 1935). Mostly he composed soundtracks for puppet films, and a neat little Space Age puppet film Atomic and the Goons (1970) by Elbert Tuganov, serves as a good example of his early experimental style. But that's already another story, something completely different…

IN CONCLUSION

Within the official cinema circles of the Soviet Union, animation was mainly targeted towards toddlers, young children, and teenagers. Here, on the other hand, the artists had clearly used children-oriented cartoons as a means of artistic expression, and experimented with the possibilities of the film medium in general (while also alluding to works by sympathetic artists on the screen, adding another layer of inside-jokes), and this created a discrepancy.

Although undoubtedly the mechanisms of the Soviet film bureaucracy were more prominent in this context than the rules of Estonian art life, when we look back into the process of making these animations, one thing is clear: by gradually shifting our focus from film history to art history, the true value of Estonian Pop animation of the 1970s becomes apparent – these selected films appear as fragmented manifestations of post-Second World War youth culture that also filtered into the 'wrong side' of the Iron Curtain. EF

CLASSICS EF CLASSICS 14

These selected films appear as fragmented manifestations of post-II World War youth culture.

Avo Paistik, Sunday (1977)

Backgrounds I for the animation

The Flight (1973)

15

Avo Paistik, Sunday (1977)

Elbert Tuganov, Atomic and the Goons (1970)

Elbert Tuganov, Atomic and the Goons (1970)

Avo Paistik, Vacuum Cleaner (1978)

Photo by Stanislav Stepashko / The collection of Art Museum of Estonia

Artist Aili Vint

Downward SPIRAL

Johannes Lõhmus analyses the innovative aspects of Grigori Kromanov’s debut feature film What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? from 1966.

By Johannes Lõhmus Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? was pioneering in Estonian cinema history in several ways.

First, it was the debut feature film of Grigori Kromanov. Second, it was the first domestic film to try and analyse the heritage of the Stalinist personality cult, and its influence on communist society.

Third, never had an associative montage been used in this kind of manner before, tying different timelines together into a coherent whole. Fourth, a warning label was added to a film poster for the first time, giving it a 16+ rating, because of the abundant erotic undertones in the film. Fifth, the film perplexed the audience with the fact that Kromanov had decided to leave it open-ended and that was rarely done in Soviet cinema, because cinema was an instrument of propaganda and the message had to be as singular as possible. In its historical context, What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? was a remarkable work that has successfully stood the test of time, and acquires more and more layers of meaning in our current conflicted atmosphere of the first half of the 21st century.

In the following article, I will concentrate on the five aspects mentioned and hope to create some space for serious discussion about the place of this film in world cinema, amongst the films dealing with similar problems and themes, using similar stylistic means. As this kind of discussion can only take place after seeing the film, it is a pleasure to state that the Estonian Film Institute together with the National Archive’s film archive have recently restored the film digitally.

WHO WAS GRIGORI KROMANOV?

Grigori Kromanov (1926-1984) was an actor by profession who was forged into a director in Estonian Television. He was constantly at odds with the Soviet cultural policies because of his uncompromisingly thorough nature as an artist, and would therefore direct only five feature films during his career. But if there is a director worthy of a grandmaster’s title, it is Kromanov. The psychological depth of his characters, the scale of his shooting sets, and dedication to the intricacies of film directing allow us to position him side by side with Stanley Kubrick and David Lean, as their Soviet Estonian compatriot who shares their sensibilities and thematic concerns. All of them are joined together by a grandiose mindset, utmost thoroughness, and fearlessness to demand the near impossible to execute their vision.

Kromanov’s first film was The Misadventures of the New Satan (1964), co-directed with Jüri Müür, and heralded as the greatest Estonian film ever upon release.1 What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? (1966) was Kromanov’s first film where, as a director, he was solely responsible for the result. The Last Relic (1969), Diamonds for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1975) and Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (1979) followed suit. All his films were seen by millions of people all over the Soviet Union, they were distributed to dozens of countries abroad, proving Kromanov’s ability to address a wide and versatile audi-

ESTONIAN FILM 16

CLASSICS

1 Ivar Kosenkranius. "Film ja aeg". Tallinn. 1974. Lk. 85.

17

The role on Andres Lapeteus was played by popular theatre actor Einari Koppel.

CLASSICS

The communist ideological struggle was here applied to veterans of the Great Patriotic War, or World War II as it is known outside Russia – the most honourable men in the Soviet Union.

Jaan Saul wrote after the premiere in Sirp ja Vasar: “Lapeteus is a modern look at the recent past, a complicated, fresh past, the discussion about it is still ongoing, the effects and consequences are still being argued about, the evaluation and the exact formulation of the period is still in the phase of shaping and reshaping.” 2

The film gains most of its original character from Kromanov’s way of storytelling though, not the theme. The psychological drama unfurls simultaneously on several timelines, telling the story of the decline of a conformist man, up to the moment when his frontline comrades tell him something that the audience has become more and more aware of as the film progresses: “People don’t have a grudge against you, but they don’t love you much either”. The decline from a hopeful builder of communism to a troubled careerist is shown in a reverse turn of events.

THE TECHNICAL SIDE

ence with his films. These results could only be achieved by a few directors.

All this might not have come to be, if it weren’t for the film version of Paul Kuusberg’s 1963 novel “The Andres Lapeteus Case” that Kromanov, master of the psychological portrait, successfully brought to screen.

THEMES IN THE FILM

Paul Kuusberg could start on his novel about the disclosure of the Soviet personality cult only after the 20th Congress of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) in 1956, where Nikita Khrushchev held a speech in front of a closed hearing exposing and condemning the crimes of Stalin during his rule. The consequent book was well received in the climate of political thaw, and it attracted enough attention to be brought first to the stage in Vanemuine theatre in Tartu (premiered on the 21st of May 1964) and plans for the film version were set in motion at Tallinnfilm.

In essence, the theme of corruptive power wasn’t anything new in the cinema of Soviet Estonia: a film called Under One Roof had been released in 1962, about a power struggle in an ailing collective farm, and Traces in 1963, where the main character has an increasingly hard time remaining human and staying pure in the eyes of the party at the same time. But for the first time, these issues were brought to an urban environment in Lapeteus – to the streets of Tallinn, the capital of Soviet Estonia.

Ada Lundver plays Reet Lapeteus in the film. She is like like a breath of fresh air in the Soviet Estonian cinema –a woman who just wants to enjoy good life.

The intricacies of editing were pointed out in reviews by contemporaries like Mati Unt, Jaan Saul, Valdeko Tobro (“Kromanov uses mental-associative montage, the transitions from one episode to the next are meticulously planned, clean, graceful, and wholly logical at the same time.3”), as well as Eva Näripea, film scholar of the 21st century.4 Näripea’s work highlights the important role of the cinematographer Mihhail Dorovatovski in constructing the film’s meaning and creating

2 Jaan Saul. “Lapeteus ekraanil”. Sirp ja Vasar. 01.04.1966. 3 Valdeko Tobro. “Mis juhtus Andres Lapeteusega?”Noorte Hääl 24.03.1966.

2 Jaan Saul. “Lapeteus ekraanil”. Sirp ja Vasar. 01.04.1966. 3 Valdeko Tobro. “Mis juhtus Andres Lapeteusega?”Noorte Hääl 24.03.1966.

EF CLASSICS 18

4 Eva Näripea. Film, ruum ja narratiiv: “Mis juhtus Andres Lapeteusega?” ning “Viini postmark”. Kunstiteaduslikke uurimusi 15 (4), 2006.

What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? was generally well received by both the audiences and the critics.

WHAT HAPPENED TO ANDRES LAPETEUS?

Premiere: 21st of March, 1966, Kosmos cinema, Tallinn

Length: 92 minutes, black and white

Production company: Tallinnfilm

Shooting locations: Tallinn and Narva

Directed by Grigori Kromanov; cinematographer Mihhail Dorovatovski; production designer Linda Vernik; screenwriter Paul Kuusberg; composer Eino Tamberg; producer Virve Lunt.

Cast: Einari Koppel, Ada Lundver, Heino Mandri, Ita Ever, Kaljo Kiisk, Uno Loit, Rein Aren, Ants Eskola, etc.

Ita Ever plays Helvi Kaartna in the film. Her role could be described as one of the most legendary depictions of kindness in Estonian cinema.

metaphors in visual language, as well as associations with François Truffaut’s debut feature 400 Blows (1959), and the detective films of the 1940s-1950 by the likes of Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger, and Fritz Lang.

Just as important is the Neorealist approach chosen by Kromanov, ruling out the studio as a location and making sure that the film remains a faithful period piece of dirty times when no-one could be trusted, and a stained resumé could become an issue that led to expulsion from the communist party, or worse, a one-way ticket to a labour camp in Siberia.

This unpleasant and spooky atmosphere is a commendable joint effort from Kromanov, Dorovatovski, and production designer Linda Vernik. Luckily it helps to keep the film at just the right distance from the audience, working as a reminder of the times that are currently being monstrously revived just a few hundred kilometres east of Tallinn. The atmosphere of fear, snitching, snooping around, and grovelling is effectively opposed to rare positive characters, who, in the spirit of the times, are depicted by the last honest communists.

EF CLASSICS 19

It is worth paying attention to the details – the furniture, objects on a desk, the way glances are exchanged, how hands are used, and how all of this is presented to us on camera. What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? is a film made for discovering minute details, proof of a precisely thought-out author’s signature style that can be used to characterise all of Kromanov’s films.

WORK OF THE ACTORS

Every film’s success is dependent on casting, and thanks to Kromanov’s personal experience as an actor he was great at picking the players for his films. Kromanov’s interest in psychology is reflected in the way he matches the role with the actor. Although the critics ended up being quite harsh towards Einari Koppel who played Lapeteus – mainly because the emphasis of the film is different from Kuusberg’s book, where Lapeteus is a wholly positive character until the end –, Kromanov was clearly not interested in recreating the feeling of the novel. Instead, he changed the title and turned the spotlight on the moral decline of Lapeteus, so that everyone could make up their own mind which false decision was instrumental in the disintegration of this steadfast individual.

Everything seems so hopeful at first, when a company of war heroes return home from the front. Slick Haavik (Rein Aren) is ready to do anything to become a party functionary. Simple guy Pajuviidik (Kaljo Kiisk, the most prolific Estonian feature film director of all time) is an honest and funny man of many trades, but has penchant for alcohol and various rackets. Roogas (Uno Loit) is trustworthy and loyal, his biggest sin is a wife who fled to the West together with the Germans during the war, making him a suspicious element in the eyes of the governing power. Põdrus (Heino Mandri) is the voice of reason, a man of principle who gets crushed by the machine, because he is not

Grigori Kromanov is known as a director who was great at picking the actors for his films. Einari Koppel as Andres Lapeteus and iconic Ada Lundver as his wife Reet.

ready to go against his conscience. Helvi Kaartna (Ita Ever) is the only positive figure in this story, always true to herself, one of the most legendary depictions of kindness in Estonian cinema. Unfortunately, she has to use her kindness in the interest of the criminal political establishment.

Their opposites are Järven (Ants Eskola) – shaper of the post-war society, a dogmatic Stalinist, in both word and deed. A true embodiment of evil. And the wife of Andres Lapeteus, Reet (Ada Lundver), described by Mati Unt as a “provincial Marilyn”, who is a complete contradiction in the whole of Soviet Estonian cinema.

In Estonian cinema of the 1960s, she is the only character who simply wants to live well and enjoy life. It’s a concept that didn’t really fit the Soviet ideology, and is not shown in very good light here, but essentially, Reet is like a breath of fresh air and a complete departure from the Soviet Estonian film women with headscarves and buttoned-up cardigans. Her role

CLASSICS

EF CLASSICS 20

There were no open ends in the Soviet cinema. Evil was punished according to the party line, but now, suddenly Kromanov leaves it open.

THE WORDS OF THE DIRECTOR GRIGORI KROMANOV

before the beginning of the shoot, 1965: “The story of Andres Lapeteus grabs me personally. The story is current, and forces us to ask: who are we, what has happened, or is about to happen to us? The film has to be able to answer this. Can we remain truthful in every situation, even in small matters of life? Can we stay true to ourselves and always see our life goal?”

forces the Soviet cinemagoer to analyse conversations about rape, adultery, and deception. All three should be labelled amongst the things that “do not exist in Soviet Union”, but somehow these themes slipped into the film and became immortal thanks to Kromanov, hinting at their existence with its fair share of participants and victims in the vast USSR. Ada Lundver is magnificent as a bourgeois party hostess, and the house party scenes are certainly among the most memorable and entertaining in Estonian film history.

THE IMPORTANCE OF AN OPEN END

Legendary Estonian film critic Jaan Ruus has said: “There were no open ends in the Soviet cinema. Evil was punished according to the party line, but now, suddenly Kromanov leaves it open.”5

In this solution, we see the director’s boldness not to follow the usual tropes of his first film; and his attempt to lead the audience towards a more active cinema experience than was usually assumed. The biggest wonder of What Happened to Andres Lapeteus? lies in exactly that – trying to get the audience to think along. Although it is a film that glorifies the red principles of the red era to a degree, there is enough room between the lines for the viewers to piece the puzzle together themselves. It is an opportunity offered by only very few authors of Soviet cinema, and Kromanov is certainly among them. EF

The director Grigori Kromonov working on the set with the legendary actor Heino Mandri.

5 “Kaadris: “Mis juhtus Andres Lapeteusega?”” 10.02.2012.

CLASSICS

MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA

Johannes Lõhmus introduces Andres Sööt, the living legend of Estonian documentary, whose sharp gaze has chronicled our life through good and bad, in the spins and swirls of history.

By Johannes Lõhmus Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

Andres Sööt is the most prolific chronicler of Estonia’s recent history, and a living legend of documentary filmmaking, whose camera has recorded life from small islands and urban cafes in the 1960s, to the South Pole. In the 1970s, he added films to his portfolio about folkdance, Tallinn airport, and sailing. Around then, documentary portraits found their way into Sööt’s filmography, and his films about artists and simple people of the time have become priceless documents about the era. In the 1980s and 1990s, he continued portraying important cultural figures and made some chronicle docs about the collapse of the USSR that are essential to Estonian history.

All in all, he has made over 100 chronicles and 58 documentaries as a director, and a host of other notable films as cinematographer (Sööt prefers to call himself a cinematographer as well, not a director).

Andres Sööt was born on the 4th of February, 1934 in Paide, survived deportation to Siberia,

learned to become a railroad worker but listened to his heart and became a filmmaker instead, graduating from the Russian State University of Cinematography VGIK in 1962. In the beginning of the 1960s, Sööt worked in many Soviet film studios as a documentary cinematographer (as a director on some films too), in 1963–1972 he was in Tallinnfilm, in 19721980 in Eesti Telefilm, and then in Tallinnfilm again, until he was made redundant in 1994 when the film studio was dissolved after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Here is a brief account of his artistic achievements during all those years.

THE SIXTIES

Before his directorial debut, Sööt scored his first jackpot as a cinematographer being the man behind the camera of Valeria Anderson’s magnificent cinéma vérité industrial documentary Rocky Lullaby (1964). It’s a historical piece of work, because for the first time in Soviet Estonian cinema, a documentary was made

EF CLASSICS 23

Director Andres Sööt behind the scenes of Rocky Lullaby (1964).

CLASSICS

exciting interpretations of it. Seems like the bigger the distance between the film’s production date and current time, the bolder his hidden camera experiment about Tallinn café culture that mixes the poetry of Artur Alliksaar, cosmology, the Beatles, and Bach. Critic Tristan Priimägi has written: “511 Best Photos of Mars belongs among the best Estonian documentaries. A film that ages, but never gets old, and is being reborn time and time again.”3

without a voiceover. Usually, the voiceover was meant to strengthen the propagandist effect of the visuals, and the standard documentary format was a ten-minute short film with a lot of words but not much to say. Rocky Lullaby was something else, much thanks to Sööt’s contribution. From the reviews of the day: “Director Valeria Anderson has succeeded in fulfilling four main conditions, responsible for the birth of a good documentary. /--/ Fourth: unique style. Here, Anderson owes a lot to Andres Sööt who masters the specific demands of widescreen format very well.”1

This was followed by Sööt’s first author film Ruhnu (1965). A poetic ten-minute etude about the nature and people of Ruhnu island, described by film critic Valdeko Tobro in Tallinnfilm expert council as follows: “I would like to turn your attention to the reproaches that the whole island cannot be seen in the film. But it is not a travelogue but a mood piece. Its meaning is derived from experiencing the mood.”2 Seizing the mood and capturing ingeniously human moments have become Sööt’s trademarks throughout his career. His intuition as a documentarist, and the skill of being in the right place at the right time is unprecedented in Estonian cinema, and there is no one else who could reach a level of such genuineness, especially with the limited means offered by film stock.

With his third film 511 Best Photos of Mars (1968), Sööt’s level of generalization became truly universal. The film’s vibe is unique in the Soviet context – so much so, that every coming decade offers new and

From November 1968 to May 1969, Sööt and his co-director Mati Kask spent some time in the Antarctic, filming White Enderby Land (1969) and Ice Kingdom (1970), the first in black and white, and the other in colour, about life in the South Pole. The films were beautifully scored by Arvo Pärt, and both are among the most visually attractive Tallinnfilm documentary works of all time. No heroic pathos, just the picturesque snowy landscapes that have been exploited to the fullest in the interest of the films. These films have even been called “the most popular Estonian documentaries”, because the material that Sööt and Kask shot was exhaustively repeated in various nature shows of the Soviet Central Television station.4

This decade also featured The Secrets of Tallinn (1967) – one of the very few Estonian films in the city symphony genre, and probably the best, again relying heavily on Sööt’s abilities as a cinematographer.

THE SEVENTIES AND TWO HIT FILMS

While Andres Sööt directed all his early films in Tallinnfilm studio, he divided his attention between different studios in the 1970s, beginning his collaboration with Eesti Telefilm and Eesti Reklaamfilm (Estonian Advertising Film), plus works commissioned by the Ministry of Culture of the ESSR (Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic). The tempo intensified and thematic expansion was considerable: problem films about the stunted bodies of youth, extraordinary portraits of intriguing characters, recounts of important events, various aviation films, continuing expedition docs, this time to Canada, Africa, and the Northeast Passage. And probably the best film about filmmaking (A Dream, 1978).

We will take a closer look at two especially good films about life events, Midsummer’s Day (1978) and Wedding Pictures (1979).

In Midsummer’s Day, Sööt uses the hidden camera once again to chronicle the summer solstice celebration in Tallinn. Two film writers have captured the essence of Sööt’s observingly human style so well that it’s hard to add anything. Director Andres Maimik has written: “What makes Sööt’s Midsummer’s

1 Valdeko Tobro. “Sookollidest hällilauluni”. Sirp ja Vasar, 19. veebr 1965.

2 Riigiarhiiv ERA.R-1707.1.874

3 Tristan Priimägi. “101 Eesti filmi” (2020). Varrak. Tallinn. Lk. 53.

4 Tatjana Elmanovitš. “Andres Sööt, dokfilmi režissöör ja operaator”. Noorte Hääl, 23. juuli 1972.

511 Best Photos of Mars consists of a selection of cafe and "night club" visitor types from the late 1960s, where old ladies have not yet completely forgotten the bourgeois manners of the Republic of Estonia and soviet youth cannot enter a restaurant without a tie.

Midsummer's Day shows the emotional impoverishment of the townspeople, showing their loneliness and at the same time the exuberant state caused by alcohol in large crowds.

24

Ruhnu (1965)

Ruhnu (1965)

25

511 Best Photos of Mars (1968)

Ice Kingdom (1970)

Ice Kingdom (1970)

Midsummer's Day (1978)

Photos by Mati Kask & Andres Sööt

CLASSICS

Day timeless? The theme of the film – Soviet chaos, the everyday absurd and tacky kitsch have largely lost their social meaning, and at first glance, Midsummer’s Day shouldn’t offer much in the way of recognition or identification with today’s society or current issues. /—/ Midsummer’s Day’s tone is not pessimistic, although, logically, it should be. The characters are portrayed with pleasure and aplomb. Looking at them today, they rather resemble some aliens or Soviet cartoon characters than examples of the aggressively vulgar Homo Sovieticus.” 5

Tristan Priimägi has said: “Big Midsummer Day’s celebrations have been recorded in Pirita and Õismäe on two consecutive years. Seemingly they are not different from any mass events – lots of people, noise, and activities – but Sööt’s sensitive eye for detail singles out colourful and characteristic nuances in this mess of Babylon, turning feast into farce – a Soviet soft-version of Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.”.”6

Both writers have understood the essence of Sööt’s films – his warm sense of humour and non-judgemental look at life. Sööt creates an opportunity for everyone to judge the characters according to their own degree of depravity, while refraining from this himself as an author as much as possible.

Wedding Pictures from the next year is memorable too: we see two wedding parties in all of their pain and glory. Filmmaker Karol Ansip has successfully drawn a parallel between Wedding Pictures and Midsummer’s Day. “Wedding Pictures, much like Midsummer’s Day, shows peculiar contrasts: folk dances and games versus hot disco; a Soviet way of conducting business and Viru Valge vodka; Fassbinder-ish 1970s design and eternal human comedy.” 7

1980S AND 1990S

Sööt’s most noteworthy works of the next decades are Reporter (1981), Year of the Dragon (1988), Year of the Horse (1991), and Escape (1991).

Midsummer's Day tells about the celebration of Estonia's most important holidays in urban conditions. The film, recorded with a hidden camera, vividly depicts the change in the traditional content of Midsummer's Day.

Reporter is a journalistic portrait about hotshot radio reporter Feliks Leet, filmed with Sööt’s trademark warm humour. Reporter is different from the majority of Sööt’s works, because the author is forced to interfere with the events on the screen and we are presented with a rare opportunity to hear his voice asking questions. In a film about a radio reporter, whose main job is to ask questions and to talk a lot, this approach feels completely natural, although it probably doesn’t come naturally to Sööt himself.

Year of the Dragon and Year of the Horse are relevant because they freeze-frame a certain period in time; the final years and collapse of the Soviet Union from the perspective of a small nation whose eyes

6, 1997.

5 Jaan Ruus.” Kes teab, kuidas meidki naerma hakatakse. Uus põlvkond hindab vana kunsti” [Katkeid TPÜ kultuuriteaduskonna filmi-meedia eriala sisseastumistöödest A. Söödi "Jaanipäeva" (1978) teemal; üles kirjutanud Jaan Ruus]. Teater. Muusika. Kino, nr

6 Tristan Priimägi. “101 Eesti filmi” (2020). Varrak. Tallinn. Lk. 100.

5 Jaan Ruus.” Kes teab, kuidas meidki naerma hakatakse. Uus põlvkond hindab vana kunsti” [Katkeid TPÜ kultuuriteaduskonna filmi-meedia eriala sisseastumistöödest A. Söödi "Jaanipäeva" (1978) teemal; üles kirjutanud Jaan Ruus]. Teater. Muusika. Kino, nr

6 Tristan Priimägi. “101 Eesti filmi” (2020). Varrak. Tallinn. Lk. 100.

EF CLASSICS 26

7 Karol Ansip. “Aegumatu klassika läbi kahe sajandi II. Andres Söödi elu-ja loomelugu”. Teater. Muusika. Kino, nr 3, 2014.

Midsummer's Day (1978)

Midsummer's Day (1978)

Year of the Horse (1991)

have always been turned to the West. Year of the Dragon is rife with contradiction – “In the world of Year of the Dragon, grand and petty, serious and comical, noble and shallow, reality and illusion exist side by side here as equals”.8 It is the year 1987 and nationwide protests against mining phosphorite in Estonia grow into a dream of independence. A couple of years later this dream cannot be quashed by the wavering giant, i.e. the Soviet Union any longer, and Estonia can consider itself an independent state once again. These crucial events of 1987 have been captured by Sööt’s camera for all time. Year of the Horse takes place already in 1990 when the Soviet tanks are moving on Tallinn, but Estonians manage to make the Soviet Union recognize the sovereignty of Estonia without any human casualties. It is the year of becoming independent again.

Escape is a film that shows courage to address uncomfortable themes in an already more liberal climate. It is a story about Estonian boat refugees, fleeing to Sweden and Germany from the Soviet Army in 1943–1944. Many of them were forced to return to the USSR by Sweden once the war was over. A heartbreaking film about a topic that doesn’t probably have much traction in the liberal Nordic country.

In addition to the films mentioned, Sööt makes some of his most remarkable portraits about cultural figures in this decade and continues to film sports documentaries in his modest manner. Watching An-

1988 was an exceptional year in the life of Estonia. To everyone's surprise, the national flag and symbols were allowed to be used. Sööt's documentary tells the story of that year's events in Estonia.

dres Sööt’s documentaries as an Estonian, gives one a nice reassurance that even the fragile existence during the Soviet era has been depicted in a sort of benevolent and positive light by Sööt.

And positivity, not towards the authorities of the time who allowed him to make films, but a hopeful and human glance into the better future that reflects in the eyes, words, and deeds of his characters. Anyone, who is interested in the events of the past 60 years in the current NATO and European Union border state Estonia, might gain from searching out Andres Sööt’s films. These are a good starting point to gain a better understanding of our tiny nation, and where we come from. EF

must see films

by Andres Sööt

1. Rocky Lullaby (1964)

2. Ruhnu (1965)

3. Tallinn Secrets (1967)

4. 511 Best Photos of Mars (1968)

5. White Enderby Land (1969)

6. Midsummer’s Day (1978)

7. A Dream (1978)

8. Memory (1984)

9. Year of the Dragon (1988)

10. Year of the Horse (1991)

FILMMAKER VALENTIN KUIK ABOUT THE FILMS OF ANDRES SÖÖT IN SIRP JA VASAR:

“As a dedicated documentarist, Sööt strives for maximum truthfulness. His films are very individual in their authenticity, they are masterfully made and not altogether so simple. Sööt doesn’t use any explanatory or judgemental voiceover. Viewers who have gotten used to the stereotypes of “good” and “evil”, or keep looking for it, don’t find their way around in his world easily. Inevitably, one has to think along with the author, and join him in his attempts to find answers to all these universal but not simple questions”

8 Tiina Lokk. “Eesti tõsielufilmi suundumustest”. Teater. Muusika. Kino, nr 6, 1989.

Year of the Dragon (1988)

The Secrets of Tallinn (1967)

The Secrets of Tallinn (1967)

CLASSICS EF CLASSICS 28

Satan Came to Earth The

Johannes Lõhmus writes about The Misadventures of the New Satan, a film where metaphysics and Estonian literary classics meet.

By Johannes Lõhmus Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia

The Satan usually spends his time collecting the souls of the dead in Heaven, but suddenly everything changes for him. As he knocks on the gates of Heaven, it turns out that God has started to doubt humanity’s ability to become blessed, which endangers the previous agreements between Heaven and Hell, thus God may no longer send the souls of the sinful down to the Satan in Hell. The only way to maintain the status quo is for the Satan, himself, to go to earth as a human to prove that one can become blessed through work. This is the prologue for the film The Misadventures of the New Satan, co-directed by Jüri Müür and Grigori Kromanov, where Elmar Salulaht plays the scruffy-headed hulk of a Satan-Jürka who takes on the challenge of trying to become blessed among the humans, even when the Almighty, Himself, has personally cast doubt on the idea. The film was made in 1964 in Soviet Estonia where “the figure of the

Satan was one that generates fear in ideology. If there is no God, then there should also be no Satan, but suddenly the Satan appears in Estonia,” said the Estonian SSR Cinematography Committee Chairman Feliks Liivik when looking back on the era in 1990s independent Estonia.1 Indeed, the film’s release at the time was surprising since the period of 1959 to 1964 saw an active anti-religious campaign in the Soviet Union.

But by some miracle, this film with a deeply religious and philosophical subtext was shown all over the Soviet Union and became the first significant success in Estonian film history. The reason is probably the gravity of the original material, and the policy adopted at the Tallinnfilm Studio to bring more national literary adaptations to the screen, which, of course, does not guarantee the success of a film in and of itself.

THE MISADVENTURES OF THE NEW SATAN

Premiered on June 15, 1964 in Tallinn

Length 95 minutes, black and white

Production company: Tallinnfilm. Filmed at the Tallinnfilm and Lenfilm pavilions and the Moscow Popular Science Film Central Studio zoological base; outdoor locations in different parts of Estonia.

Directors: Jüri Müür and Grigori Kromanov; director of photography: Jüri Garshnek; production designer: Rein Raamat; scriptwriters: Jüri Müür and Gennadi Koleda; composer: Eino Tamberg; managing director: Veronika Bobossova. Cast: Elmar Salulaht, Ants Eskola, Astrid Lepa, Leida Rammo, Heino Mandri, Eili Sild, Jüri Järvet, Kaarel Karm and others.

First Tallinnfilm film to win the Grand Prix - Big Amber of the Film Festival of Baltic States, Belorussia and Moldavia (USSR).

29 EF CLASSICS

1 Kommentaare Eesti filmile: "Põrgupõhja uus Vanapagan" 28.04.1996.

The poster is designed by artist Martin Jurikson.

CLASSICS

Success requires the alignment of several favourable elements, but it all starts with the script and the director’s deep understanding of the opportunities afforded by the material.

THE ORIGINAL NOVEL AND PLACE IN ESTONIAN HISTORY

The Misadventures of the New Satan is the last novel by Anton Hansen Tammsaare, the greatest classic of Estonian literature. It was written in the summer of 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II when Europe trembled in fear of war and different ideologies clashed – capitalism against communism and national socialism. The work is considered to be the author’s most multi-layered novel as it contains political, folkloric, theological and intertextual layers,2 which become the basis for an exciting and original film.

The

film, which does justice

to the combination of satirical symbols and deeper meaning of the original work, premiered on June 15, 1964 and the leading film critic of the time, Valdeko Tobro, was full of praise: “Müür and Kromanov’s The Misadventures of the New Satan is the best Estonian film ever made. It lays the groundwork for the screen adaptations of not only Tammsaare’s work but also our other literary classics.”3 It is a film that is still written about 55 years after its premiere: “The Misadventures of the New Satan is the first total hit of Soviet Estonian film art and still often called one of the best Estonian films of all time.”4 But how was such an exceptional and original film even made?

THE SHOOTING AND THE EXTENSIVE PRODUCTION

In 1955, Estonian Jüri Müür went to Moscow to study feature film di-

recting at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) (where his course instructor was Aleksandr Dovzhenko). Only a couple years later, he was already infected with the Satan bug and got VGIK screenwriting student Gennadi Koleda involved to thoroughly work through the material and write many versions of the script. Müür had a definite plan to make his graduate film a full-length feature, and that it had to be The Misadventures of the New Satan (the script’s working title at the time was Earthbound). “Dovzhenko told us that you have to choose your first script like you choose your bride. I’ve also been eyeing my bride for the last four years,” said Jüri Müür at the VGIK Study Council where they were discussing producing the script together with Koleda on March 24, 1960.5

Unfortunately, the film was not given the green light at the time and Müür received his diploma for directing the film Men from the Fisherman’s Village (1961), which is also an important work in Estonian film history, as it is the first full-length feature film in So -

2 “Meie Tammsaare. Kohtumisraamat kirjanikuga”. Toimetanud Kadri Suurmäe, tõlkinud Kai Takkis. 2014.

3 Valdeko Tobro. “Alus on rajatud – mõttemõlgutusi esimese Tammsaare-filmi puhul”. Edasi, 28.06. 1964.

4 Tristan Priimägi. “101 Eesti Filmi”. Varrak. Tallinn. 2020. Lk. 33.

5 “Lavastaja Grigori Kromanov”. Koostanud Irena VeisaiteKromanova. Eesti Raamat, 1995. Lk. 518.

EF CLASSICS 30

6 “Lavastaja Grigori Kromanov”. Koostanud Irena VeisaiteKromanova. Eesti Raamat, 1995. Lk. 518.

Going to Earth as a human being, Satan is sure that through work it is possible to find bliss there. But his neighbor Clever Ants has his own plans...

Estonian theatre legend Ants Eskola, who portrayed Clever Ants, a role worthy of his talents7 and Heino Mandri and Kaarel Karm’s performances were even named the best supporting roles in Estonian cinema.8

The film’s production designer Rein Raamat remembers the shoot: “Grigori Kromanov was a director who was masterful in his work with actors. His background was in acting so he understood scenes and knew how to play them out through the performances. Kromanov always had a lot of rehearsals with the actors to get the characters working precisely. He also worked through the contrasts in the characters of the Satan and his wife and the Satan and Clever Ants. Once Kromanov had finished the prep work with the actors, Jüri Müür arrived on set and took over. Müür determined the technical di-

7 Õie Orav. Tallinnfilm I. Mängufilmid 1947-1976. Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, 2003, lk 312.

8 Valdeko Tobro. “Alus on rajatud –mõttemõlgutusi esimese Tammsaarefilmi puhul”. Edasi, 28.06.1964.

viet Estonia made with a creative crew composed entirely of Estonians. During the shooting period for the film, he met Grigori Kromanov, who was working as the second director whose job was to direct the actors. For a debut film, Men from the Fisherman’s Village was quite an achievement and, more importantly, it opened the door for Müür to start work on his passion project.

With The Misadventures of the New Satan, Müür and Kromanov were equals as director in the film hierarchy even though they still had quite different roles to play, which probably only benefited the film. Kromanov continued to focus on working with the actors, deliberately staging the dialogue scenes in an uncharacteristically static manner similar to other well-known directors of the same era like Ingmar Bergman or Luchino Visconti.6 The result finally gave

31

New Satan (Elmar Salulaht) and Clever Ants (Ants Eskola).

Also small roles in the film are played by top actors at the time. From the left: Ervin Abel, Einari Koppel, Hugo Laur.

CLASSICS

rection, the camera work and the lighting. The cooperation between the two directors worked as a nice symbiosis.”9

Most of the film was shot in real locations. The Satan’s farm was built in Suure-Jaani and the spectacular fire that takes place at the end was filmed for real. Together with the firefighters, the villagers and the film crew, there were about 200 people to manage on set, which was quite an achievement for the time, and for the two fairly inexperienced directors.

The gates of Heaven with their large scales where Peter and the Satan have their discussion on bliss in the prologue to the begin-

ning of the film had to be built in a studio. Since the set was so large, it wouldn’t fit into any sound stage in Tallinn, then they had to go to Leningrad (modern day St. Petersburg) and build it there. Cranes were holding the giant scales in place and the smoke used to create the atmosphere meant that a separate, metre-high barrier had to be built around the set so that their impression of heaven wouldn’t spill out into the rest of the pavilion. Production designer Rein Raamat had to decide the style for the gates and he went with gothic because of the style’s strong ties with religion.10

For the life-and-death struggle

between the Satan and the mother bear, they searched all over the Soviet Union for a suitable bear until they found one somewhere in the expanses of Russia. The bear cubs came from Tallinn Zoo, and all of the bear roaring we hear in the film are original recordings.

A TIMELESS AND RELEVANT PIECE

As a result of all the challenges faced and preparation done, a completely timeless film was made that talks of themes as relevant today as probably at any time, as long as the world still has a capitalist market economy and some form of currency in use. There has always been a danger of working one’s self to death but, today, an era striving more than ever to combine work, a lifestyle and self-realization at any cost possible, these topics are even more relevant than they were in the Estonia of the first half of the 20th century when Satan-Jürka roamed.

The film perfectly presents the absurdity of the situation where the Satan, usually associated with evil, seeks bliss, so he enslaves himself to the big banks, or to loan sharks, or to the embodiment of an inhuman boss, Clever Ants, who keeps raising the rent because that is how our people are supposedly able to live better, even

9 Elise Eimre. “Vastab Rein Raamat”. Teater. Muusika. Kino, märts 2021.

9 Elise Eimre. “Vastab Rein Raamat”. Teater. Muusika. Kino, märts 2021.

EF CLASSICS 32

10 Elise Eimre. “Vastab Rein Raamat”. Teater. Muusika. Kino, märts 2021.

“Let it burn, the money will come!” is the historically symptomatic attitude of the entire Western worldview that believes in endless economic growth and the reason why humanity and our planet are in danger of catching fire here in the 21st century.

The film with a deeply religious and philosophical subtext was shown all over the Soviet Union and became the first significant success in Estonian film history.

if that means the worker has to sell his worldly belongings and still ends up taking out another loan on top of it all.

There is an absurd atmosphere in The Misadventures of the New Satan, which is enhanced by the brilliant dialogue and excellent supporting roles that help to highlight the contrast between slowwitted Satan-Jürka’s benevolent, extra-terrestrial strength and Clever Ants’s boundless greed. The final phrase that slips from his lips at the end of the film: “Let it burn, the money will come!” is the historically symptomatic attitude of the entire Western worldview that believes in endless economic growth and the reason why humanity and our planet are in danger of catching fire here in the 21st century. It is exceptional how accurately a writer from a small country, and two film directors working together were able to put the confrontation between human greed and sincere benevolence unprotected against exploitation into such an effective, 95-minute, explosive form. EF

The cast and crew working on the set of The Misadventures of the New Satan.

“The film contains a lot of opposite polarities, such as happy versus unhappy and exploitation and the exploited, and, in the end, the book is really just telling us that we have to learn to lie in the right way. Just as there were no disabled people on screens at the time, there were no church pastors there either. They just didn’t

exist for the public. Russians, Jews and Estonians also didn’t exist for the public because there was one, Soviet people. But this film could refer to Tammsaare (and created nationalities and professions that didn’t exist before – ed.) and that was powerful!”

33

FILM CRITIC JAAN RUUS ABOUT THE MISADVENTURES OF THE NEW SATAN:

CLASSICS

Love Island

Tõnu Karjatse writes about Corrida, a psychological drama by Olav Neuland that reflects Estonian cinema in the beginning of the 1980s when the Soviet Empire began to show the first signs of deterioration.

By Tõnu Karjatse Photos by Estonian Film Institute & Film Archive of the National Archives of Estonia, Villu Reiman

Olav Neuland’s (1947–2005) Corrida from 1982 has the initial makings of a chamber drama – a lonely island, three people (or unequal love triangle), and a herd of animals. Man against wild nature, his urges, fears, and desires. Osvald Rass (Rein Aren), a man in his sixties, his wife Ragne (Rita Raave) who is about half his age and full of life, and her ex-lover Tarmo (Sulev Luik), have reached a decisive point in their lives where important choices need to be made. The isolation of a lonely island sets the characters face to face with each other, depriving them of social safety measures. It should help them to evolve eternally, but whatever they have brought to the island is of no help any longer. The rudimentary animality that manifests itself in various ways in this situation, strongly challenges the habitual rationale.

Director Olav Neuland wished to bring modern psychological drama to Estonian cinema with this Bergman-esque chamber piece. First, he introduces the customary dramaturgical stereotypes, and then tries to cancel those via themselves, as the story progresses. Teet Kallas’ initial novel of the same name the film is based on, proved to be an obstacle rather than an inspiration in this process, because instead of the moral and ethical development of the characters, we remember great acting work and seemingly endless wrestling with the bulls.

Every piece of art comes with its own temporal context that it inevitably expresses. Teet Kallas wrote the novel Corrida in 1979. Olav Neuland’s film was released in 1982. For Neuland, it was the second feature after the immensely popular Nest of Winds (1978), considered to be one of the landmarks of the so-called new wave of Estonian cinema, and a fresh generation of filmmakers and their first works in the end of the 1970s.

THE BEGINNING OF THE EIGHTIES

1982 was a good year for Estonian film in general, bringing Peeter Simm’s children’s adventure Arabella, Daughter of the Pirate, Peeter Urbla’s musical psycho-drama Schlager, Ago-Endrik Kerge’s drama Under the Black Roof, and Leo Karpin’s musical film Doppelgangers. The same year, Tiina Mägi made the socio-critical documentary Where Shall We Play Today? about the living environment of kids in Tallinn Old Town, and the struggle with careless Soviet bureaucracy. A year later came Nipernaadi by Kaljo Kiisk that definitely belongs among the evergreen classics, and Raul Tammet’s Sidewind, a sports film that has unfairly never received the praise it deserves. Taking into account some earlier titles like Dandelion Game (1977), a trilogy of short stories from then-beginners Peeter Simm, Peeter Urbla, and Toomas Tahvel, and Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel from 1979 by Grig-

EF CLASSICS 35

CLASSICS

CORRIDA

Premiere: 28.02.1983, Tallinn, Estonia Length: 84 minutes, colour

Production company: Tallinnfilm

Shooting locations: Tallinn, Tabasalu, Kuressaare, Saareküla

Screenwriter & director Olav

Neuland; cinematographer Arvo Iho; production designer Heikki Halla; composer Sven Grünberg, producer Raimund Felt. Cast: Rein Aren, Rita Raave, Sulev Luik, Vaino Vahing

ori Kromanov, it is safe to say that change of the decade 1970-1980 was the period when Estonian cinema attempted to break out of existing ideological boundaries.

In this historical and political context, Corrida can be considered a successful satirical allegory about the deterioration of power, a glimpse of hope, and the empty solutions, brought about solely by choices based on comfort. The film feels like a critique on conformism even today.

Corrida’s characters introduce several options for how this conflict plays out. Rein Aren, Rita Raave, and Sulev Luik, luminaries of the Estonian acting scene, allow the director to flesh out the intentions of the characters in Corrida. Osvald Rass enjoys the high position of the intellectual elite in Soviet society. He’s not a member of the party, but his writing is favourable in the eyes of the authorities. Osvald swiftly exploits the benefits available for the elite – he has a large apartment, access to rare goods, a sizable income, and the option to work in peace in the local residency. Osvald rents a small island meant for artist residencies, to work on his monography amongst the nature. This is his only goal, he doesn’t feel his position is in danger in any way. Besides, he is certain that the secluded island setting makes him even more irreplaceable for his young wife Ragne. But Ragne becomes bored as soon as they reach the island, the chamber of horrors set up in one of the adjacent farmhouses is enough to excite

OLAV NEULAND

was an Estonian film director and amateur pilot. He was born in 1947 and died in 2005 in a tragic plane accident.

Neuland studied acting in the Department of Theatre of the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre in Tallinn, and cultural education work in the Tallinn Pedagogical Institute. He continued his education in Moscow where he studied in the Higher Courses of Scriptwriters and Film Directors in 1976–1978. In 1969–1972 Neuland worked in Estonian Telefilm as 1st AD, and in 1973–1976 as a screenwriter, editor, and director. He was employed as a film director in Tallinnfilm in 1978-1988.

• His first documentary A Sound Rang in My Breast (1972) was also his graduating film. Neuland continued making documentaries until 1995. Three of his documentaries were dedicated to Estonian organs and organ players.