13 minute read

Aathma Nirmala Dious, Susan Writes to Papa

from Airport Road 11

Susan Writes to Papa Aathma Nirmala Dious

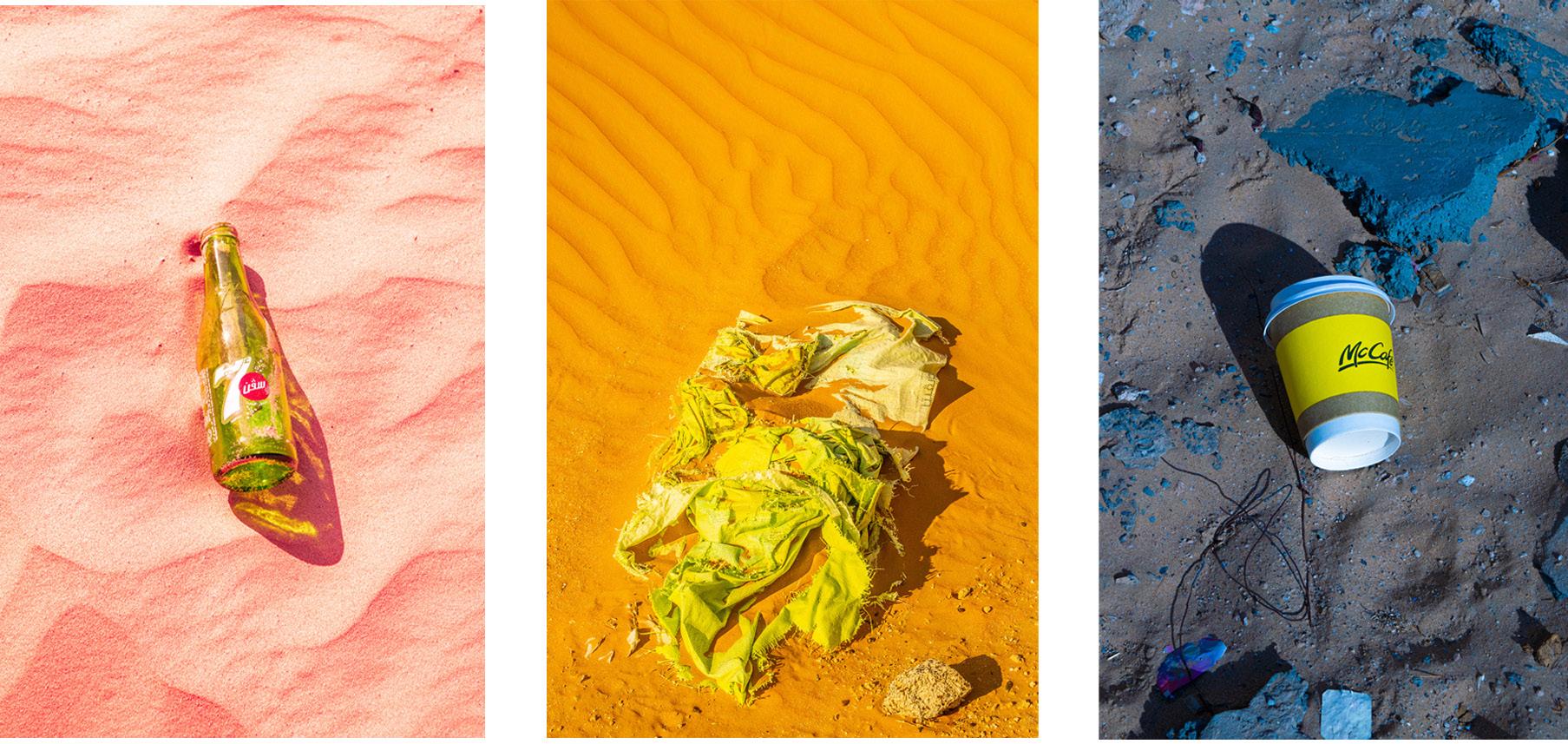

Susan has only known her Papa as a myth, growing up on folktales of his presence, the genre changing, ranging from cautionary tale to success story, depending which tongue of the people of Maruthadi it came from. Ammama, his mother, described him as a sensitive boy who daydreamed of lands beyond the sea outside their house. Amma described him with a silence, which was more accurate. However the end of all the stories were all the same. He was not here. He was in the Gulf, fathering a new set of buildings or pulling oil from the sand, sending money as the dutiful breadwinner should.

Papa left because money lenders searching for the money that is now Kochamma’s dowry came knocking with threats of taking the roof away. Papa prayed to God, Mother Mary, and Eshopa all in that precise order for help. In a dream, a pathemari came upon the shore of Maruthadi. Papa stepped on, confused and a thunderous voice that he guessed was the sea, Kadalamma herself, woke him in a sweat. When the sun rose, Papa heard the call from a pathemari that lulled men with the promise of dreams made of jewels and gold. In exchange, he would help build a new oasis for Arabis, made of concrete and glass from liquid gold in the Gulf, the new name for Persia.

A dream for a dream after all. A fair exchange.

Papa believed this Gulf that Ammama calls Persia is where he can change the future. The night before, Amma cried, putting his hand on her round belly.

“Swear on our child,” she told Papa, “that you won’t drown in their

quicksand promises or follow fool’s gold that you will come back to father them–”

He nodded solemnly. Susan’s Papa stepped upon the pathemari the next day, its belly pregnant with men with carbon copy contract dreams, carrying memorabilia of the family they left and Gods who they hoped would stay with them in foreign lands.

Two months after, neat envelopes of money came every month and the money lenders stopped trying to break down the door.

Susan looks at her dark wrist, adorned with a gold bracelet her Papa put on her toddler hand when he first came back, luggage now filled with gifts. There was a pretty green sari for Kochamma, a gold bangle for Ammama, a small bottle of whisky for Amma’s Papa, Pappachan (Arabis drink? No, they don’t, according to Amma, but the Vellakaran bosses from Britain do and Papa secretly got it from the same place). Amma got a gold ring and her little brother, baptized Jose but nicknamed Unnikuttan, although he came 9 months after that visit. When the sun glinted off the gold, Susan would stare at the bracelet, till she recalled a soft lullaby and a silhouette of a man by the door. Leaving or coming? Who knows? Was that even Papa? Who knows? * * * When Susan went to school for the first time, Ammama braided her black curls with new red ribbons, bought with gulf money. Amma tugged at her blue pinafore. “Listen, you should work hard. Papa wanted you to study. He said he’ll send over a doll if you study well.”

Ammama whispered just after Amma went to take her bag for her, that she should try becoming the doctor Amma wanted to be. It was years after when Susan learned Amma was married to Papa before she could

even try– Amma’s Papa, Susan’s Pappachan discovered an unread love letter between her 12th standard Malayalam textbook, slipped into her bag by Susan’s teacher George during class. Kuncheria, Pappachan, first trashed her to put the fear of God in her because a woman of God should not love but obey. Amma had no Amma to defend her. A month after she finished school, Papachan commanded that she would be married to Papa. On the wedding day in the church, Amma imagined the gold chains decorating her getting tighter and tighter around her. She wanted a stethoscope around her, not this! Pappachan’s quiet glare kept her from running into the sea, back to Kadalamma.

Papa did not know about George’s letter until three months after they married, when Kochamma heard it from Rosakutty, whose husband drank with Pappachan and then told Ammama. Papa came from his meeting with a gulf recruiter to see Ammama throwing clothes upon Amma, who was lying on the floor and weeping. He calmly picked her up, told Ammama to stop and took Amma to the safety of the bedroom. “He asked me and I told him. He actually did not care and then said we should not mention it again.” Amma ended the story with that.

Lucky, They all told Amma, all the time. Papa does not hit you. Papa is a man from a good Christian family, planning to go to the Gulf soon. He will bring Gold for you.

What they forgot to tell in the stories was how the Gulf, like Kadalamma on a bad day punishing the fishermen, swallowed men whole and did not return them. * * * “Why did Amma marry Papa?” Susan asked one night, lying next to Amma on the mat. The only thing Maruthadi’s tales did not have was a love story.

Amma turned to stare at her. Susan was still on her mat, expecting the usual silence.

“He had kind eyes, unlike the stone-blank ones the man that got me married did, and ears that actually listened.” Susan almost sat up if it was not for Amma’s hand on her belly, pressing her down. “Usually a man’s ego falls as easily and hurts as much as a ripe coconut falling on your foot after you kick the tree. Your Papa never had that. I never understood how. He said it was because he did not want to be like his Papa.”

She paused, stroking Susan’s hair. “He just yearned to give your Ammama a feast and a house that did not flood from the monsoons. However he mostly wanted to escape from his Papa, your Appapan, who loved the spirits more than the holy spirit he preached of.” Susan looked at Amma’s face and she could see a tear slowly play with the edge of Amma’s brown jaw. “That’s why he used to pray to God in Church and ask Kadalamma by the sea as he sat on the shore to take him and your Ammama somewhere far, somewhere safe. Your Appapan went to God too soon, just before I met him. I guess we both knew the pain fathers can inflict.”

Later, when only the moon was awake, Susan slowly slipped out and from her door looked at the sea, where her father was last seen. She wondered if fathers can inflict pain even if they were not here. * * * At the wise age of 8 years old, Susan would say yes.

Some of the other girls whispered that her Papa is not there and more bad whispers mimicking the evening talks of their families. She would see their Papas, Appas, Achas and Uppas pick the other girls and boys up after school, taking their bags, hoisting them on cycles and walking them

back. It’s okay. Susan just stared at the board when the girls whispered. Susan liked studying and learning about rhymes and letters and numbers. Laxmi Teacher always gave her three out of three stars drawn in her notebook. One month later, Amma came with a doll with white hair and ghostly blue eyes. “Papa is happy you are studying. I told him about the stars in your notebook.”

Unnikuttan whined about wanting a doll and Amma distracted him with a box of Quality Street chocolate. Susan smiled at the mention of Papa’s pride. Who cares what the other girls say–her Papa was real. The doll, now named Mary, sat beside her as she slowly made her way through a nursery rhyme. She will get more stars and maybe with enough stars, she can bring Papa back.

She whispered a silent wish for Papa to Kadalamma every time she walked on the beach to school, the sea calm in the morning fog. Fatima, her best friend walked with her but would only stand by because her Umma would not be happy at her asking anyone else but Allah for her Uppa, also in the Gulf. Hussain Ikka, older and more impatient than his little sister Fatima, would keep yelling their names till they started walking again. * * * When Susan’s writing got better, Amma suggested that she write a line in the letter about to be sent to Papa. She painstakingly drew the curls of her Malayalam to ask if he was okay and when he would come so she can show him her notebook and eat Unniyappam with him by the beach. Amma added more words of her own, folded the white paper covered in Camel Ink into a brown envelope and put a stamp with some old man on it.

In a month, with the envelope of money, came Papa’s reply. “Hello Susankutty. You write so well! Keep studying, okay? Papa will come when

the rains start. I am working hard so I can bring chocolates and more gifts for you. When I come, we will take your Amma and Unnikuttan with us to the beach, look at the stars above while we eat both the chocolate and unniyappam!”

Susan slowly read it out with the help of Amma. Later, Susan took her notebook out and slowly copied each letter out again and again in her notebook, exactly how Papa wrote it. Amma’s eyes watered and blinked a lot when she showed her the notebook. Did she not write it properly?

She kept the letter next to her that night.

“I want Papa.”

“Unnikuttan.”

“I WANT PAPA!”

Susan stood by Ammama, watching her Amma fumble at Unnikutttan’s request. Unnikuttan also goes to school now so now Susan walks with Fatima, Unnikuttan and Ikka. Fatima’s Uppa came today. Everyone saw Hussain Ikka yelling in joy and Fatima smiling as their Uppa took their bags. Susan and Unnikuttan waved goodbye to them and then stood in silence in front of the school, till Ammama came.

“Unnikuttan, please. I said I will come tomorrow to pick you up. Susan chechi and Fatima chechi and Hussain chetan all walk with you too.”

“Their Uppa came back. I want Papa.”

“Papa will come soon, Unni—”

“YOU ALWAYS SAY THAT. I HAVE NEVER SEEN HIM!” Unnikuttan stomped around Amma. “I WANT PAPA OR IS HE A GHOST LIKE THE BOYS SAY?”

“What? Who said that? Susan, did you hear this?”

All eyes on her now. Amma’s angered ones, Unnikuttan’s teary ones, and Ammama’s curious ones. Susan nodded. “They always say it to me and Fatima too.” She doubted they would say it about Fatima anymore. It was just her now.

Ammama sighed. “It must be that Rosakutty. She has a nose longer than what the Lord gave her.”

“Mummy, stop. I have to talk to the teacher about this. They cannot keep parroting their parents,” Amma snapped before slowly kneeling in front of Unnikuttan. “Now, Papa said he will come when the rains start–”

“That’s what he said last time too and he did not come last monsoon,” Susan blurted out. The letter, among many other similar letters, sat by her notebooks and Mary Doll, that now had brown hair from the dirt.

Unnikuttan turned back on Amma, glaring at her before bursting into tears and running out.

“Unnikuttan!” Amma ran after and caught him just before he left the new gate. “Come in! Now! There’s a storm coming–”

Looking up, Susan saw the dark clouds gather, then looked down at her brother struggle in her Amma’s arms, screaming for Papa. She could see

some of the neighbors pop their heads over the wall between the houses and their doors. houses and their doors. It was just her and her Amma, Ammama and Unnikuttan, and no Papa. Never Papa.

The sea’s waves were getting higher. She ran.

“Susankutty!” Ammama shouted but unlike Amma, she was slow due to her age and hurting knees.

Susan heard the wind whistle in her ears as her legs carried her to the beach. After a few heavy gasps of air, Susan poked her finger into the fine beige sand. She heard Thoma and Krishna say that if you wrote Kadalamma’s name in the sand, the sea will come to wash it away.

Her finger moved with practice to the letters, more fluent to her now from rewriting Papa’s letters and school. She stepped back to look at the word and waited. Thoma and Krishna, known pranksters, were lying for sure. Why would Kadalamma, the sea itself, listen to a child’s words in sand?

But before she could formulate an answer, water splashed her out of her thoughts and before she could move, the water went back and the letters were gone. Susan’s mouth dropped.

Not caring about her only school uniform, Susan knelt down, the wet sand grains scrapping her legs and dug her index finger back into the sand to write. Ka-da-l-A-mm-a, bri-ng Pa-pa ba-ck. She had to listen. How many wishes has Susan said to the horizon? How many stars has she gotten for her writing? He had to come, he had to come, he had to—

As soon as she finished the letters, a wave came. Susan did not see the wave. It did not just come to the words. Before she could process it, the

wave crashed onto her and the force flung her off her knees and salt water entered into her mouth.

Susan does not remember what happened after. She woke up coughing on her mat, with her Amma shaking her while screaming at her for going to the beach during a storm. Ammama started thanking the cross on the wall. Unnikuttan jumped on her, talking fast about how she had disappeared and how they found her on the shore, eyes closed, finger in the sand, the rain falling on her.

Kadalamma was so angry that night, she flooded all the houses and toppled all the boats, swallowing people left, right and center. For once, even the new house Susan’s Papa worked so hard in the Gulf for, did not stop the water from coming. The four of them did not sleep the whole night, trying to pick things off the watery floor.

Susan picked up her bag to put into the cupboard and one of Papa’s letters fell into the water. She pushed the bag in and scrambled for the letter. She was late. The water covered the letter, smearing the neat malayalam words her father wrote during his nights in the Gulf.

Her tears came in spite of all the blinking, and soon the teardrops joined the sea around Susan’s feet, the letter scrunched in her hand.

A man with a grey mustache in khaki pants and a blue shirt stood by the gate. It was three days after the storm. Susan was holding Unnikuttan’s hand, having just come back from school.

“Ah, you must be Susan and Jose.”

Unnikuttan looks at Susan. “Chechi, Who’s Jose?”

“It’s you, potta.” Susan slapped the back of his bald head before turning to the man. “Sorry, Uncle. We always call him Unnikuttan.”

The man smiled, but a sadness overcast it, confusing Susan. “Is your Amma home, Susankutty?”

Amma came out, answering his question, and shooed Susan and Unni back into the house.

Just as Susan removed her shoes, a shrill scream made her fall. She got up and turned to her Amma, falling to the ground, still screaming. The man stood, with a look Susan did not have the words to call.

Susan learned later the word for it was “guilt.” Kadalamma or God or neither of them sent him to deliver Papa’s last letter, which asked her to keep looking for stars. On the day Kadalamma raged at the shores of Maruthadi, Papa was swallowed into the Arabian sea at the shores of the Gulf, while in the pursuit of the oil that promised too much, like these letters. He will always remain a myth and no more stars would bring him back.