INSIDE

TAKING ON DIABETES:

GLOBAL COLLABORATIVE BRINGS HOPE

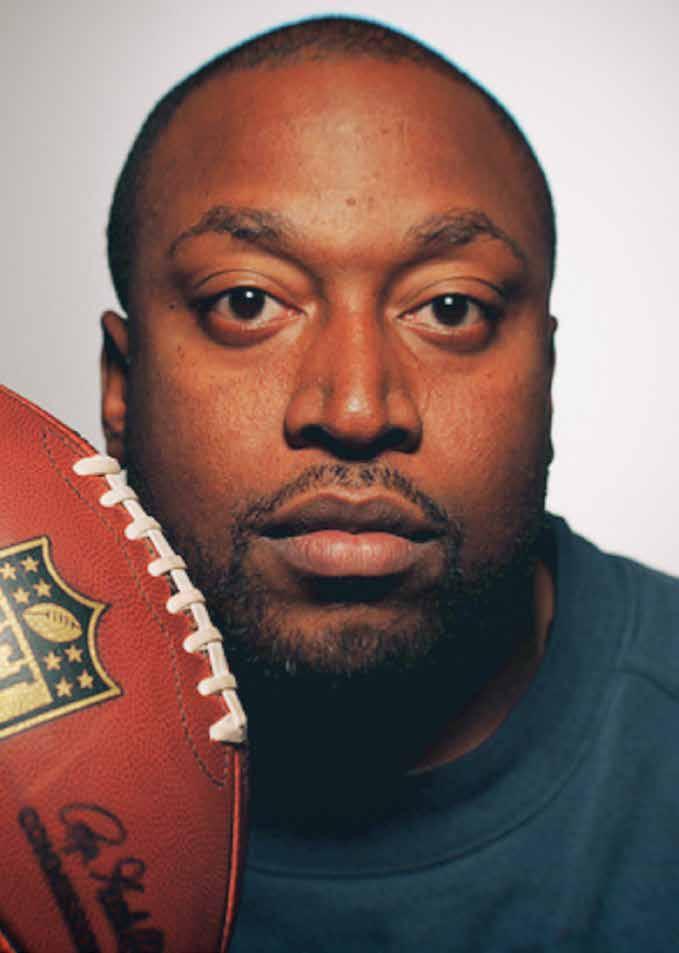

FORMER NFL

TIGHT END

MAKES A HEALTHY COMEBACK

HIGH TECH + HIGH TOUCH

Critical Care in the ICU

SUMMER 2023 12

TAKING ON DIABETES

An innovative global approach to reducing diabetes—a growing pandemic that affects more than a half-billion adults worldwide—is finding new ways to prevent, treat, and possibly eradicate it.

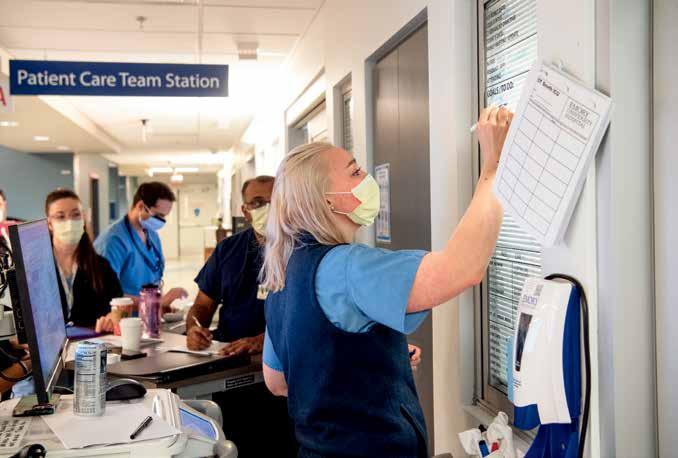

Emphasis on the Care 12

The Emory Critical Care Center is made up of 334 adult ICU beds and staffed by hundreds of care providers around the clock. They see the sickest of the sick, patients who need compassionate care as much as skilled medical interventions.

28

contents

WILD HEALING

“We have barely scratched the surface of the medicinal value of plants.”

—medical ethnobotanist

Cassandra Quave

3

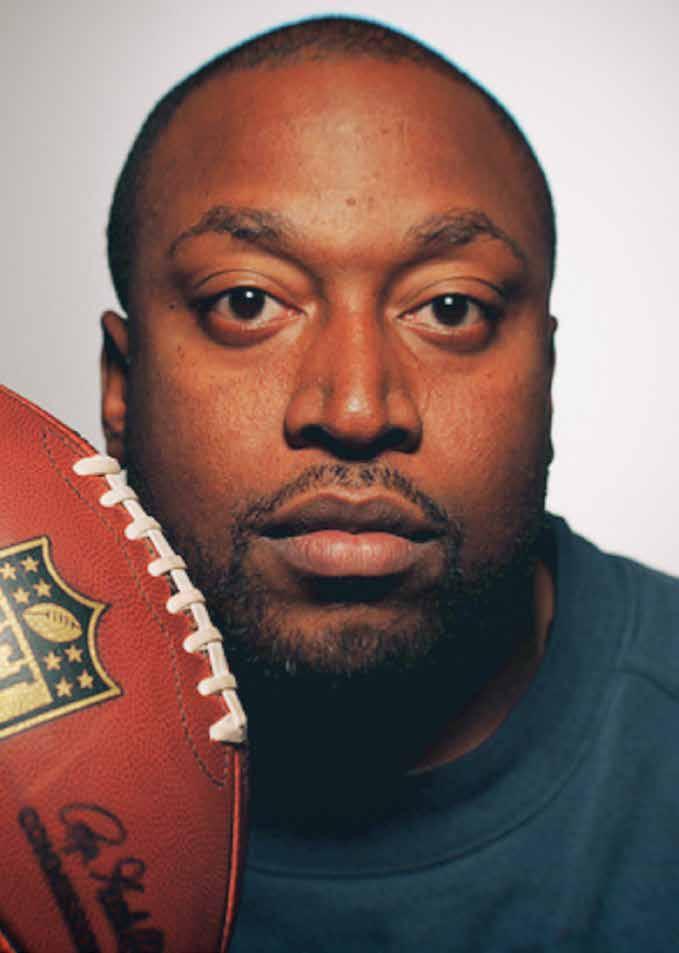

The Comeback 36

Former NFL tight end Alge Crumpler was struggling with his weight and overall health when a new team stepped in to help: a group of specialists from Emory Healthcare.

30

ILLUSTRATION CHARLIE LAYTON PHOTO COURTESY ALGE CRUMPLER

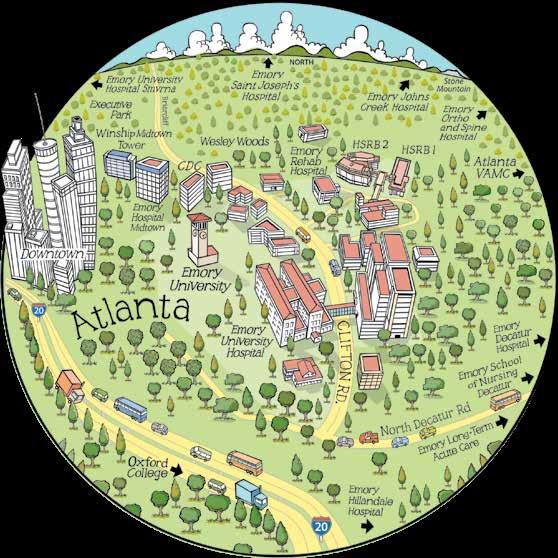

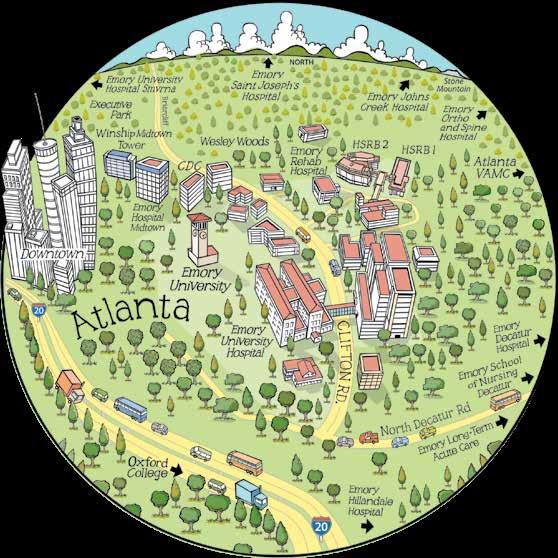

Multidisciplinary to its core, the new Health Sciences Research Building II brings together computationists, researchers, and core technologies to solve the biggest human health problems.

Addiction Center 10 Emory Healthcare partners with the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation to open the Emory Addiction Center.

the well

To Our Readers 4

A message from Ravi Thadhani, executive VP for health affairs, executive director of WHSC, vice chair of Emory Healthcare Board. The Well 5 Strength training. Bystander CPR. New Emory Healthcare CEO Joon Sup Lee. Childhood obesity. Boosting research. Emory Addiction Center. HAL S5301 finds a home.

Beyond the Bench 10 Collaborative research at Emory and other institutions is getting a boost from Georgia CTSA.

and more Policy Wise 46 Congressional action is essential to save millions of lives, says Carlos del Rio, interim dean and professor at Emory School of Medicine and president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Emory Brain Health Center and Georgia Public Broadcasting’s Emmy-winning news magazine, Your Fantastic Mind, has a new fifth season out. Take a look at www.pbs. org/show/your-fantastic-mind/.

Emory Health Digest

Ravi Thadhani Executive Vice President for Health Affairs, Emory University, Executive Director, Woodruff Health Sciences Center, Vice Chair of the Board, Emory Healthcare

Vincent Dollard Editor

Mary Loftus Managing Editor

Peta Westmaas Art Director

Jack Kearse Photography Director

Jim Auchmutey, Susan Carini, Jodie Guest, Carlos del Rio, Maureen McCarthy, Kenneth Murry, Martha Nolan, Beth Ann Swan Contributors

Stacey Jones Copy Editor

Rashmi Raveendran Editorial Intern

John Mills Senior Director, Online Communications

Stuart Turner Production Manager

Jarrett Epps Advertising Manager

Jennifer Checkner Executive Director of Content

Cover Illustration Paul Oakley

Emory Health Digest is published twice a year for patients, donors, friends, faculty, and staff of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center. © 2023 Emory University

Emory University is an equal opportunity/ equal access/affirmative action employer fully committed to achieving a diverse workforce and complies with all applicable federal and Georgia state laws, regulations, and executive orders regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action in its programs and activities. Emory University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, ethnic or national origin, gender, genetic information, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, or veteran’s status. Inquiries should be directed to the Office of Equity and Inclusion, 201 Dowman Drive, Administration Bldg, Atlanta, GA 30322. Telephone: 404-727-9867 (V) | 404-712-2049 (TDD).

23-EVPHA-EVPHA-0044

2 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST 10

contents

6

ILLUSTRATION DEAN ROHRER

MUST SEE TV

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

INNER VISION

REMEDY? Extracts from two common wild plants inhibit the virus that causes COVID-19, found an Emory study. In laboratory tests, extracts from the flowers of tall goldenrod and the rhizomes of the eagle fern blocked SARS-CoV-2 from entering human cells. Researchers warn it would be ineffective and potentially dangerous for people to try to treat themselves with the plants. “We’re working to identify, isolate, and scale up the molecules from the extracts,” says Cassandra Quave, senior author and associate professor in Emory’s Department of Dermatology and Center for the Study of Human Health.

NATURAL

A new door to innovation for patients

An important moment in the future of research at Emory occurred March 15 when a ribbon-cutting ceremony was held for the new Health Sciences Research Building II, the largest facility of its kind in Georgia.

The new eight-story, 350,000-squarefoot building will house more than 1,000 researchers, including 130 principal investigators, from a variety of specialties including pediatrics, biomedical engineering, oncology, cardiovascular medicine, vaccinology, radiology, and brain health.

Emory provides patients with exceptional treatment by world-class providers who have access to the most advanced therapies available, which are frequently designed and discovered right here by our own investigators. This link between patient care and scientific discovery and innovation attracts exceptional learners and differentiates Emory within Georgia and beyond, lessening disease burden, keeping people healthy, and preparing the next generation of care providers.

Our Health Sciences Research Building II is designed to strengthen that linkage; to inspire connectivity, collaboration, and innovation; to remove boundaries; and to invite cross-disciplinary research with access to some of the most sophisticated equipment available today.

I’m so proud of the incredible promise of this facility and the ways in which it will facilitate collaboration and collegiality in service to the greater good.

A deep thanks to all who support Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center in ways large and small. You are essential to our mission of improving the health of individuals and communities here and around the world, and pioneering new ways to treat and prevent disease.

Kind regards,

Ravi Thadhani

Please direct questions and comments to evphafeedback@emory.edu.

to our readers 4 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

Ravi Thadhani, Executive Vice President for Health Affairs, Emory University, Executive Director, Woodruff Health Sciences Center, and Vice Chair of the Board, Emory Healthcare

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

the well

Medical Fitness Association in 2017.

Georgia Barkers, a retired nurse whose career included service in the US Army Nurse Corps, has been a member of the Wellness Center for more than a decade. “I joined the Wellness Center in 2009 after I had my first hip surgery,” Barkers says. “Initially, I tried water aerobics, then I eventually wanted something more strenuous.”

Gray began incorporating the new strength training machines into Barkers’ twice-weekly one-hour workouts (photo below). Barkers credits the added challenge from the strength equipment with helping her achieve one of her primary fitness goals. “I’ve been trying to strengthen my right knee and hold off on replacement surgery,” she says.

The two bonded as Barkers began achieving her health goals. They learned they shared similar experiences as military veterans. “I love working out with Lisa because she provides encouragement,” says Barkers. “We set goals in our individualized training sessions.”

STRENGTH TRAINING PAYS DIVIDENDS

Strength training can help maintain and even improve overall health as we age. Benefits, particularly for older adults, include weight loss, mobility improvement, and muscle mass retention, which can improve stability and help delay or even avoid surgery or disability.

Thanks to the generosity of community members, patients, staff, and providers, the Wellness Center at Emory Decatur Hospital has made a significant investment of more than $73,000 in new strength equipment, which is already paying dividends for members and fitness coaches.

“Members love the new equipment and appreciate the update,” says Lisa Gray, Wellness Center group fitness coordinator and American Council on Exercise certified personal trainer.

The Wellness Center was the first medical fitness center in Georgia to be certified by the

Because lean muscle mass naturally diminishes with age, body fat percentage will increase over time if nothing is done to replace muscle. You can do strength training at home or at a gym by: lifting free weights; using your own body weight by doing squats, lunges, situps and pullups; using fitness machines; using resistance tubing or cable suspension.

Be sure to warm up for five to 10 minutes first, and use weights that tire your muscles after 12-15 repetitions. To give your muscles time to heal, rotate muscle groups. Aim for strength training for all major muscle groups at least two times a week.

For more information go to emoryhealthcare.org/ centers-programs/wellness-center/index.html for information about a free seven-day pass.

SUMMER 2023 5 age well

ILLUSTRATION

EHD

NEIL WEBB

THE WELLNESS CENTER is an 18,000-square-foot, fully equipped fitness facility with an indoor pool and indoor track on the campus of Emory Decatur Hospital.

PHOTO COURTESY OF EMORY HEALTHCARE

Save a life with CPR and your own two hands

Following a review of six years’ worth of national data collected by Emory University School of Medicine’s Cardiac Arrest Registry for Enhanced Survival (CARES), a diverse team of researchers found that Black and Hispanic people were significantly less likely than White people to receive potentially lifesaving bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during cardiac arrest. The study published October 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

The comprehensive analysis showed that Black and Hispanic individuals had 26% lower odds of receiving bystander CPR at home when compared with White individuals.

Those odds dropped significantly in instances of public cardiac arrest, where Black and Hispanic individuals had 37% lower odds of bystander CPR than White individuals going through the exact same emergency event.

The study examined CARES data gathered from 2013 to 2019, and builds upon previous scholarship into health equity and cardiac arrest in several ways, including the additional examination of neighborhood income level and racial and ethnic make-up where individuals originally collapsed.

Researchers discovered that the disparity

between response for Black and Hispanic individuals versus White individuals remained consistent regardless of neighborhood income level or racial and ethnic makeup and regardless of the type of public setting.

Bystander CPR can double or triple survival rates for those experiencing cardiac arrest.

The earlier CPR is administered (ideally in the first two minutes after a patient collapses), the better the outcome will be.

“As an emergency medicine physician, I know how incredibly important bystander CPR is for cardiac arrest patients,” says Bryan McNally, Emory professor of emergency medicine and executive director of CARES. “Our research team hopes this study will be a catalyst for change to help reduce racial and ethnic differences in cardiac resuscitation and improve outcomes for all communities.” McNally is co-author on the NEJM publication. EHD

Founded by Emory and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2004, CARES serves as a multicenter registry of people who have had nontraumatic, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the US. The registry is funded by the American Red Cross, the American Heart Association, and through state-based subscription fees.

6 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST care well

ILLUSTRATION LEMONO

“As an emergency medicine physician, I know how incredibly important bystander CPR is for cardiac arrest patients.”

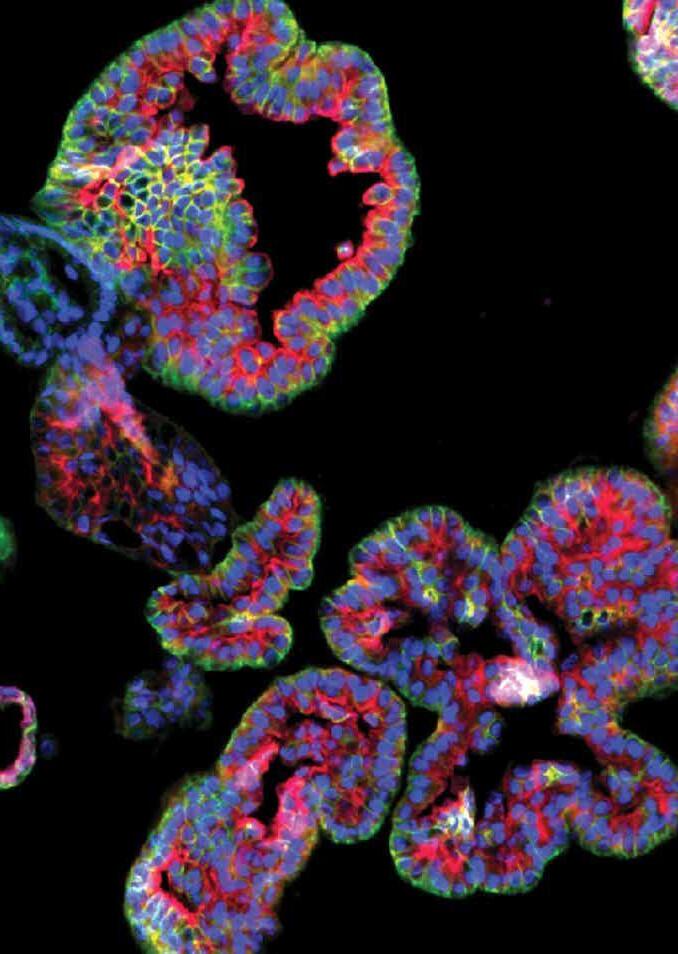

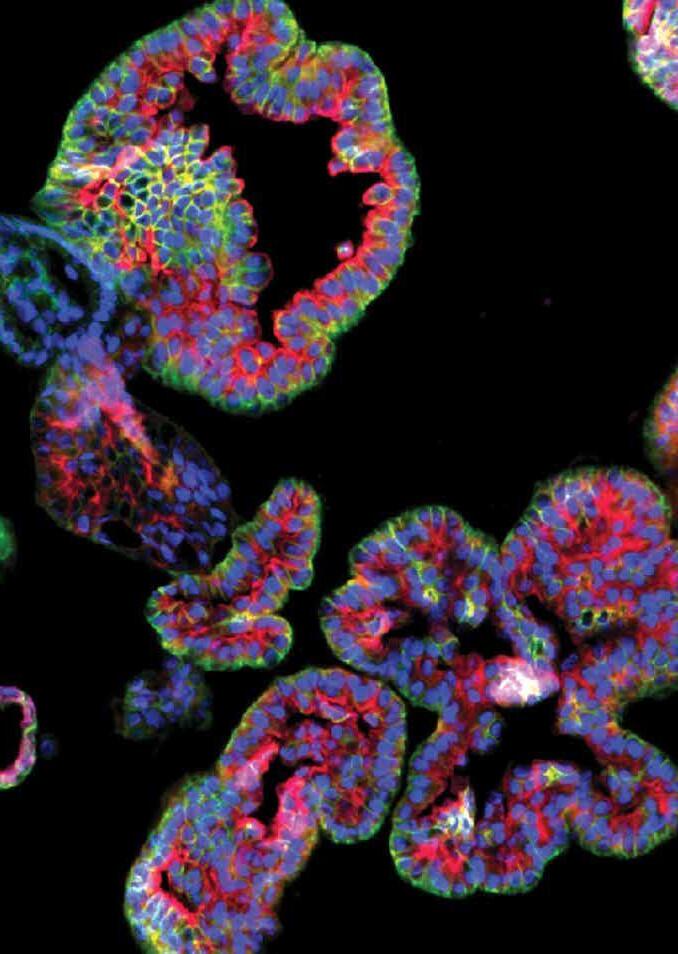

BENCH TO BEDSIDE

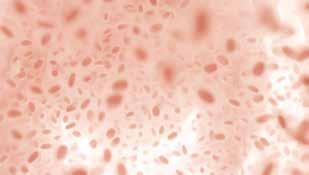

An award-winning image of human kidney organoids, which are being used to help develop new cancer therapies. The 3D cell culture models are established from patient-derived kidney tumor tissues. Researcher Vo BaoHan from Haydn Kissick’s lab in the Department of Urology, in collaboration with Emory’s Department of Chemistry, is using the organoids to test novel anticancer compounds.

SUMMER 2023 7

Micro photo by Vo BaoHan

“After several misdiagnoses from multiple providers, I was finally diagnosed with stage 3 ovarian cancer. I had treatment at Emory’s Winship Cancer Institute, and now I’m cancer free. I feel so fortunate, and that’s why I made a gift that supports cancer research—to help other women now and in the future.”

Diana Blair

Cancer Survivor, Benefactor

10 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

A

giftplanning.emory.edu

legacy of heart and mind.

• 404.727.8875

Joon Sup Lee to lead Emory Healthcare

After an extensive national search, Emory University announced that Joon Sup Lee has been named chief executive officer of Emory Healthcare, effective July 1.

As CEO, Lee will be responsible for overseeing the most comprehensive academic health system in Georgia with 11 hospitals, 250 provider locations, and more than 24,000 employees.

“Dr. Lee is an outstanding leader who is ambitious, talented, and prepared to serve our world-class health care enterprise on day one,” says Ravi Thadhani, who joined Emory in January as executive vice president for health affairs and vice chair of the Emory Healthcare Board of Directors. “He has tremen-

dous experience as an executive, and he also has a deep understanding of the patient perspective as well as the power of research to save and improve lives, developed during his time as a practicing cardiologist. He is poised to make great contributions and elevate Emory Healthcare.”

Lee served as the executive vice president at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and president of UPMC Physician Services, where he was responsible for 5,000 employed physicians and all clinically active faculty. His scope of work included physician services, quality of care, patient experience, patient access, and financial oversight of physician services. EHD

Childhood obesity starting earlier, more severe

Obesity in childhood and early adolescence can be linked to poor mental health and is often a precursor to chronic diseases in adulthood, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

A study published in Pediatrics and led by Rollins global health researcher Solveig Cunningham found that rates of new cases of obesity in elementary school are higher and are occurring earlier in childhood than even a decade earlier. The multidisciplinary Emory team includes co-senior authors Michael Kramer, K.M. Venkat Narayan, and postdoctoral fellow Rebecca Jones.

The researchers analyzed the ages children are most likely to develop obesity and which children are at highest risk. They compared data on children entering kindergarten in 1998 and in 2010 and followed them through fifth grade. The data are nationally representative, so findings can be generalized to children growing up in the United States.

Major findings include:

• Approximately 40 percent of today’s high school students and young adults experienced obesity or could be categorized as overweight before leaving primary school.

• Children born in the 2000s experienced rates of obesity at higher levels and at younger ages than children 12 years earlier, despite public health campaigns and interventions.

• Non-Black Hispanic kindergartners had a 29 percent higher incidence of developing obesity by fifth grade compared to non-Black Hispanic kindergartners 12 years earlier

• The risk of developing obesity in primary school among the most economically disadvantaged children increased by 15 percent.

Cunningham says, “For decades, we have seen the number of children with obesity increasing, despite extensive efforts from many parents and policymakers to improve children’s nutrition, physical activity, and living environments. Have these efforts worked? Is obesity finally receding? Our findings indicate that obesity must continue to be a public health priority.” EHD

SUMMER 2023 9 care well

ILLUSTRATION SAM FALCON

PHOTO COURTESY OF UPMC

NIH AWARD

ACCELERATING RESEARCH ACROSS GEORGIA

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has awarded $58.6 million over the next five years to the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance (Georgia CTSA) to continue its efforts to advance clinical and translational research to positively impact health in the state of Georgia and beyond. In addition, the Georgia CTSA will receive $15.1 million in institutional support from its academic partner institutions.

Georgia CTSA is a collaborative research alliance that includes Emory, Morehouse School of Medicine, Georgia Institute of Technology, the University of Georgia, and partners including Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

“We’re excited to continue this long-standing Georgia-wide partnership, providing an environment where clinical and translational research can flourish,” says David Stephens, vice president for

health affairs research in Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences and director of the Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory School of Medicine. EHD

The Georgia CTSA supported Emory vascular surgeon Olamide Alabi’s (left) research examining the quality of care for veterans with serious artery disease.

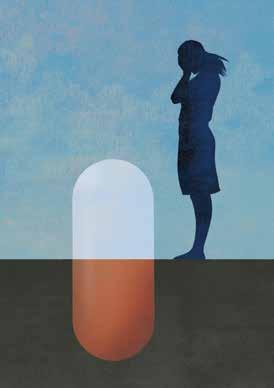

Emory Addiction Center Opens

Addiction Alliance of Georgia partners Emory Healthcare and the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation have opened the Emory Addiction Center.

The need is critical. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, more than 20 million people in the US have substance use disorder and more than 100,000 die of drug overdoses yearly.

The new center, on the campus of Emory University Hospital at Wesley Woods, offers outpatient and intensive outpatient addiction treatment to adults and adolescents older than 14 and specializes in treating individuals with dual addiction and psychiatric disorders.

Made possible by nearly $10 million in donations from public and private community partners, the center advances the Addiction Alliance of Georgia’s goal of confronting the state’s addiction and overdose epidemic through addiction-related clinical care, education, and research.

“We’re so grateful to all of the foundations and

individuals who made the vision of this new treatment center a reality,” says Justine Welsh, medical director of the Addiction Alliance of Georgia and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory School of Medicine. “Their generosity will help save and change lives in this time of tremendous need and for years to come.”

The center is run by Emory Healthcare with support from Hazelden Betty Ford, the nation’s leading nonprofit dedicated to people affected by substance use disorders. The treatment team includes addiction psychiatrists, child psychiatrists, addiction counselors, and psychologists.

Outpatient services include individual and group therapy as well as medication-assisted treatments and family support. Patients will be referred to Hazelden Betty Ford’s national system of care and other treatment centers when a higher, residential level of care is needed. EHD

10 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST treat well

ILLUSTRATION

DEAN ROHRER

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

HAL S5301 finds his forever home

Emory Nursing Learning Center first to employ robotic patient simulator with conversational speech

One of the most popular instructors at Emory’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing is a robot named HAL S5301. And, as an artificial-intelligence-powered patient simulator, he is leading the way for next-generation nursing education.

Gaumard Scientific, which specializes in simulation technology for health care education and training, manufactured and installed HAL S5301 at the Emory Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing’s new stateof-the-art simulation and learning center. This is the first commercial installation of HAL S5301.

Affectionately named “Emory HAL” by faculty and students, the simulator introduces several groundbreaking features including conversational speech enhanced by artificial intelligence, lifelike motor movement and computer-generated physiology that allows HAL to simulate stroke symptoms and other medical conditions.

“Because of Emory HAL’s engineering and artificial intelligence capabilities, he can process information and respond to learners much more organically during simulations,” said Mena Khan, director of operations for the School of Nursing simulation program. “Our students will be even better prepared for nursing care and leadership roles because of their work with Emory HAL.” EHD

SUMMER 2023 11

teach well

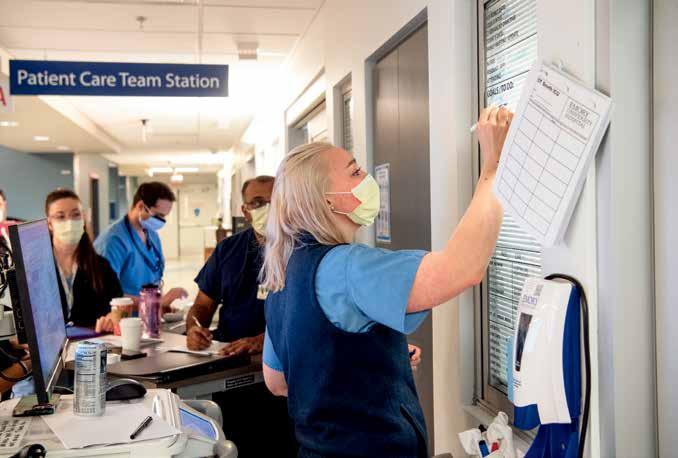

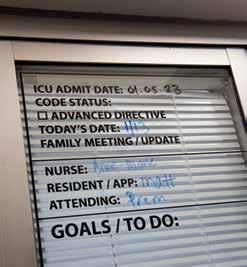

HIGH TECH + HIGH TOUCH

Critical Care in the ICU

By Vince

By Vince

“All I wanted was to take one more breath—one more unimpeded breath,” said Steven Johnson, a patient who was in Emory University Hospital’s 5E Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for more than three months. “That’s what I would have traded, because I knew I was going to die.”

Johnson’s journey to Emory began in Arkansas, where he and his wife, Arden, were visiting friends the weekend before Thanksgiving 2021. After testing positive for COVID-19, they decided to drive back home to Atlanta. Along the way, his condition worsened and shortly after arriving home, Arden sped to Emory University Hospital’s Emergency Department (ED).

“I was struggling to breathe,” he says. “When Arden dropped me off, she could not accompany me because of COVID, and I wasn’t sure I would see her again. I was immediately put into a special COVID room in the ED and promptly lost consciousness. I didn’t wake up until January 7.”

12 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

Dollard • ICU photos by Jack Kearse

SUMMER 2023 13

Johnson, 62, who works in supply chain sales, was an avid runner, didn’t have any preexisting conditions, and was vaccinated. Such are the vagaries of the COVID-19 virus that, for him, morphed into pneumonia. And while any ICU can be a scary place, Johnson’s story illustrates the value of a unified critical care system within an academic medical center.

Johnson made it through that harrowing infection and was one of several patients who spoke to participants and supporters at the Emory Critical Care Center’s “Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K” run in October 2022. The run honors the memory of Majesko, an Emory intensivist who worked in the Emory Critical Care Center.

a chance to acknowledge the care and love that I received from everyone I came in contact with in the ICU—from a medical science standpoint and from a caring standpoint.”

Steven Johnson

Joining Johnson at the 5K were other patients who were invited to share their experiences, and a common thread ran through their comments. Each pointed out that in the ICU, no matter the life-threatening issue that had put them there, the medical expertise, compassion, and thoughtfulness of the providers on every level helped pull them through.

“I am honored to be asked to speak here today,” Johnson told the assembled 5K participants on a bright and chilly morning at Emory’s Clairmont Campus field. “I’m glad I have

“Certainly, medical science saved my life,” said Johnson. “But caregiving is about so much more. The professionals in the ICU are like angels with advanced degrees. They have expansive medical knowledge and apply it with such a warm heart.”

In a later conversation, he described how one

14 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

ICU patient

“THE PROFESSIONALS IN THE ICU... HAVE EXPANSIVE MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE AND APPLY IT WITH SUCH A WARM HEART.”

Standardized

procedures across Emory’s ICUs ensure patients will receive consistent care and allow team members and specialists to work hand in hand.

day during his ICU stay, his children were able to come for a brief visit. “I was so happy to see them. And when they left, my emotions were all over the place,” he said. “I began sobbing, and Rose Gourdikian, one of the nurses, came in, sat down, and just held my hand. Didn’t say a word. The healing power of her presence was so important at that moment, it helped me regain perspective.”

A MULTIDIMENSIONAL CENTER

While the ECCC, is a “center,” that doesn’t quite define its diversity and expanse. The ECCC is currently comprised of 334 adult ICU beds. Seventy-nine faculty members and approximately 230 advanced practice providers (APPs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, provide care 24/7, 365 days a year, all working

with consistent standards of care, quality, and operational oversight.

Craig Coopersmith, director of the ECCC since 2018, notes that while the center treats the most complex medical cases, the entity itself also is complex and ever-growing.

“The ECCC is a unified system of intensivists and APPs,” he says. “Intensivists are physicians certified in critical care with backgrounds in pulmonary or internal medicine, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, surgery, or neurology. They work hand in hand with specialized Emory critical care nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, nutrition support specialists, patient care techs, and social workers to form the holistic team that takes care of ICU patients. We also consult other specialties such as infectious disease, renal, GI, and

SUMMER 2023 15

“CERTAINLY, MEDICAL SCIENCE SAVED MY LIFE BUT CAREGIVING IS ABOUT SO MUCH MORE. THE PROFESSIONALS IN THE ICU ARE LIKE ANGELS WITH ADVANCED DEGREES.”

cardiology for their expertise when necessary.”

So, how do we define the field of critical care? Timothy Buchman, founding director of the ECCC from 2009 to 2018, says, “We provide the right care right now. And you can extend that to any patient in critical care. If you were to write a job description for what we do,” he continues, “it would say that you’ll have an opportunity to work with people who are at their very worst, wracked by disease, looking death in the eye, and you’re going to do this every day, no matter how you feel.”

Buchman, currently professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Emory School of Medicine, came to Emory from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis after then–Executive Vice President for Health Affairs Fred Sanfilippo saw an opportunity for integrated critical care at Emory and reached out to him and other critical care specialists as advisers.

“Key drivers here at Emory were mortality rates,” says Sanfillipo, now director of the Emory-Georgia Tech Healthcare Innovation Program and Emory professor of pathology and laboratory

medicine as well as health policy and management. “There were varying standards from one ICU to the next, and mortality rates were not where they should have been.”

To address these issues, Sanfillipo set out to build a centralized critical care structure that would establish consistent standards of care for each ICU in the Emory Healthcare system. He tapped Buchman to serve as founding director.

“As was typical—and in many hospital systems still is—the model was department based,” says Coopersmith. “So, surgical ICUs report to the Department of Surgery, medical ICUs report to the Department of Medicine, and so on. The result is a system in which each hospital has different standards of care, and each ICU has different standards of care.”

Sandy Ockers, PA-C, a physician assistant who has worked in the ICU for 11 years, was one of the first two people trained in the ECCC nurse practitioner/physician assistant residency. When talking about the benefits of bringing Emory’s ICUs together, she gets right to the point.

16 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

The most complicated patient cases are seen in Emory’s ICUs, from cardiothoracic to neurological to cardiovascular, by a team of critical care specialists.

“Emory’s ICUs are still very different places. Each ICU has its specialty and is tailored to the population it serves,” she says. “However, when cardiac or neuro has overflow, any of our ICUs can care for these patients. Every ICU has access to ‘power plans’ for specific ICU diagnoses like sepsis and acute respiratory failure, which provide guidelines for treatment of these common conditions, so that no matter which ICU a patient is admitted to, that patient receives the ‘right care, right now’ until they can be transferred back to the specialty unit, if needed.”

Ockers also founded and played a lead role in organizing the 5K run, helping to recruit patients to share their stories. “We held our first run in 2018,” she says. “The run is designed to recognize providers, staff, and patients. And since we are all part of the ICU, the theme has been ‘I See You,’ to

celebrate the people who work so hard here, our patients, and their family members.”

One of those patients is Jody Holden, 35, of Cartersville, Georgia. Holden, a forklift driver at a carpet manufacturing facility, and his wife Abbie, both felt it was important to talk about their experience.

For a few days around New Year’s Eve 2021, Jody had complained of flu-like symptoms. On January 1, however, Abbie couldn’t wake him after he had complained of difficulty breathing throughout the night. A call to 911 brought him to the Piedmont/Cartersville Medical Center.

After he slipped in and out of consciousness for three days, Jody’s cousin, Tina Holden, lead advanced practice provider in the Emory Johns Creek Hospital ICU, recommended he be transferred to the Emory University Hospital COVID ICU on Clifton

SUMMER 2023 17

Sandy Ockers, PA-C

“EACH ICU HAS ITS SPECIALTY AND IS TAILORED TO THE POPULATION IT SERVES . . . BUT [EVERY] PATIENT RECEIVES THE RIGHT CARE RIGHT NOW.”

Road. Doctors and family members agreed, and he was transferred on January 3.

Tina Holden also reached out to Michael Connor, an ECCC attending physician and associate professor in Emory’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. He started Jody Holden on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, a machine that pumps and oxygenates a patient’s blood outside the body, allowing the heart and lungs to rest. Once Jody came off ECMO, he still needed a tracheostomy. Jody went home from EUH January 28 and the tracheostomy was removed March 23.

“When I tell this story,” says Abbie, “I talk about how wonderful everyone was. There were a few days when I was not in a good way The APPs and nurses worked hard to keep me informed since I couldn’t see Jody because of COVID. When he moved out of the

Emory critical care staff understand that seriously ill patients and their families need calm reassurance as well as skilled medical treatment.

ICU to a regular room, they spent hours teaching me how to take care of him when he got home. I want everyone on Unit 6 to know that they are amazing.” The ECCC continues to evolve. Coopersmith says, “At this point, we’re not a scrappy start-up anymore. We’ve grown astronomically, thanks to Tim Buchman and the 1,500 people who comprise this amazing team. We want to increase our world-class research footprint, and we want Emory Critical Care to be included in every discussion about the best ICUs in the world.”

Jody Holden, who continues to run his forklift on the third shift, says he’ll do his part to make that happen. “I’m not good at public speaking, but if I can ever help anyone, either a patient or a staff member, I am happy to talk with them. The doctors and nurses, their goal was to get me back to regular life. And now I am a better me thanks to them.” EHD

18 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

ECCC Director Craig Coopersmith

“WE WANT EMORY CRITICAL CARE TO BE INCLUDED IN EVERY DISCUSSION ABOUT THE BEST ICUs IN THE WORLD.”

Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K The ICU’s recognition event

The Emory Critical Care Center’s Alyssa Majesko 5K Run captures the heart and soul of its culture. First held in 2018 (and skipping 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic), the run is a tribute to the patients and providers of the ECCC.

“This event brings us together to recognize each other and to honor our patients, those who are still with us and those who are with us in memory,” says Craig Coopersmith, director of the center.

Sandy Ockers, PA, and a team from ECCC renamed the event in memory of Alyssa Majesko, a palliative care and intensive care attending physician who treated ICU patients at Emory Midtown and Grady Hospital.

Majesko, a talented physician and dedicated triathalete, was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2018 and died in the summer of 2021.

Majesko entered medicine via an unconventional path. She was a liberal arts major who enjoyed debating politics and literature, yet went into medicine with an interest in global health and women’s health disparities. She then fell in love with critical care medicine.

Majesko earned her MD from the University of Pittsburgh and continued her postgraduate training there, completing an internal medicine residency, then clinical

research and critical care fellowships.

She joined the Emory faculty as an assistant professor in the Division of Internal Medicine with board certifications in internal medicine, critical care, and palliative care medicine.

At this year’s event, her colleagues in the ECCC and Grady Critical Care, Michael Connor and Jenny Han, spoke of their love and respect for Alyssa Majesko.

“Alyssa was a bright light in this world,” says Connor. “She has left a deep legacy of love, joy, heroism, dedication, and strength.”

“In addition to being an exceptional physician, Alyssa was an endurance athlete who ran multiple marathons and several triathlons,” says Han. “She pursued everything with passion and high energy. She has inspired and taught me what it is to be a better physician and friend, and how to walk alongside someone going through chronic critical illness.”

Members of the Atlanta Triathlon Club also participated in the 2022 5K run. On their website is a tribute: “Alyssa was a long-time member of the Atlanta triathlon community. She was a fierce competitor, and she was always willing to lend a helping hand to a fellow athlete. Her energetic spirit and zeal for life were contagious.”

The 2023 Alyssa Majesko 5K Run/Walk is planned for September 30. EHD

SUMMER 2023 19

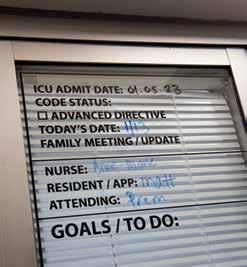

ICU WITH A VIEW: FUNCTION & FORM

By Mary Loftus • ICU photos by Jack Kearse

Traditionally, intensive care units have been intimidating institutional spaces with long, cloistered hallways, fluorescent lights, and small patient rooms jam-packed with monitors and machines. Patientswereofteninbedfortheduration oftheirstay.Visitorswerelimitedtospecific hoursand,eventhen,oftenoneatatime.The environmentwasdecidedlynotwarmand welcoming.

Buttimeshavechanged.Andjustascritical caremedicinehasevolved,healthcarearchitectsandmedicalplannersaredesigningICUs differentlyaswell,takingaperson-centeredapproachandapplyingevidence-baseddesign.

ICUpatients,forexample,havebenefited fromresearchshowingthatexposuretonatural

light cycles (day/night) lessens ICU delirium. A family area in patient rooms allows for caretaker support, vital to patient healing. And views of nature and greenery lower anxiety in patients, visitors, and staff.

Craig Jabaley, associate director of the Emory Critical Care Center and associate professor of anesthesiology, has worked with the Society of Critical Care Medicine on ICU design guidelines.

“There has been a shift from an illness-centered environment to one focused on ‘ICU liberation,’ ” which means getting folks through their critical illness to recovery, back to being contributing members of society,” says Jabaley.

20 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

“Historically, we were doing a good job of keeping people alive, sustaining organ function. But we were not doing as good a job in other areas such as preventing delirium, encouraging early mobility, and family engagement and empowerment.”

As these shifts occurred in critical care medicine, ICU design evolved to support the changes.

We spoke with several Emory Healthcare staff, from nurses to doctors to advanced practice providers who work in ICUs and have been involved in the planning, design, or remodeling of an intensive care unit recently.

The following are their thoughts on advances in ICU design.

MANY VOICES

An overwhelmingly positive advance, all agree, is that multiple stakeholders have been invited into the modern planning process, from ICU staff to patient advisers.

“The most important need from a physician standpoint,” says intensivist Michael Waldman, critical care specialist at Emory Healthcare, “is the ability to have more tech in the ICU and more advanced monitoring systems—basically, an ICU built to take on advances in care.”

Nurses echo that sentiment, saying that not only more space but thoughtful room layout is vital. “We’ve had to design for the changes in how we care for patients and for a tremendous number of new technologies,” says Toni Ash, a

SUMMER 2023 21

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

ICU DESIGN PRIORITIES

Touchstones such as clocks and day/date boards and a more homelike environment, all of which can lessen or prevent ICU delirium

Bigger patient rooms, wide well-lit hallways, and spaces for physical therapy, to enable patients to get up and moving with support as soon as possible

More expansive and creative storage to decrease clutter in rooms and hallways

A family zone inside each patient room with separate TV and sleeping area, private bathroom, and ample outlets for charging electronics

Direct sunlight into all rooms with large picture windows and solar blinds allowing for mostly natural light

Views of trees or greenery, calming art and distractions, and colors/ accents that create a feeling of hospitality and warmth

Visitor lounges on the unit with computer, refrigerator, and large screen TV

nurse with Emory Healthcare for four decades and unit director of a cardiovascular surgical ICU.

Ash recalls visiting a “cardboard city” model unit and room and the feedback from staff: “What is the best way to maneuver around the bed? If the doctor needs to intubate, do they come in from the right or left? We talked through every detail for hours.”

Clinical nurse specialist Mary Still says her team talked about the physical structure of patient rooms, how the monitor and all the equipment would flow together, the patient’s position, and the ability to turn the patient’s bed.

“We actually put someone in the bed and moved them around to see how it worked,” she says.

What most hospitals have found is that the more tech-laden ICUs have become, the more flexibility is provided by an articulated ceiling-mounted boom when possible.

“We do a lot of procedures in ICU patient rooms, so we wanted to get rid of the pain points we were having in our older ICUs and make sure it was easy and safe to do these procedures,”

says Dave Carpenter, physician assistant and codirector for quality and patient safety for the Emory Critical Care Center. “That means being able to get around the bed, good lighting, no tubes to trip over. In the new rooms, the way the booms are arranged, you can walk behind the bed quite easily.”

FAMILY CARE

Family and patient reps expressed a desire for comfortable sleeping areas and private bathrooms as well as places to work, study, or watch TV so they can “still carry on with part of their normal life,” says Still.

“Our older units had zero places for families. They were smaller rooms with just enough space for the patient and a nurse,” says Missy Anderson, assistant nurse manager of a cardiovascular surgical ICU.

“Now, families are welcomed in; there is a space for them to call their own. They are asked to participate in rounds, in conversations . . . there aren’t locked doors or us saying ‘No, you can’t come in right now.’ “

“It means a lot to families to have their own space, a sofa that

22 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

pulls out into a twin bed, capability to plug in their phones and computers, storage under the bed and in family lockers on the unit,” adds Stephanie Pieroni, unit nursing director of a surgical transplant ICU. “We put an extra chair in the room so a physician/provider could sit down and talk to family members eye to eye, for more of a connection. And most of the unit has a great view of the city through big picture windows.”

Staff appreciate the windows as well, she says. “Especially in the winter, you might come in to work when it’s dark and leave after it’s dark. It’s nice to see the change of scenery and light during the day.”

PATIENT ACUITY

have the line of sight we need to be able to care for them safely.”

Having ICU rooms all on one floor is helpful, says Rose White, ICU nursing unit director at Emory Hillandale Hospital, not only for patient safety but for staffing as well.

“Two different floors were hard to juggle,” she says. “One floor will allow a lot more efficiency. And we love having glass doors to the rooms, so we can see the patients at all times.”

COLLABORATION SPACE

The ICU is a more collaborative environment now, with intensive–care trained physicians, intensive–care trained advanced practice providers (APPs), highly subspecialized nurses for each type of ICU, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, nutrition support specialists, patient care technicians, social workers, and “an army of consultants.”

ICUs, then, must be designed in ways that facilitate this collaboration, with more open space, seating, computers, and areas for charting, teaching, and conversation.

“Nurses stations have a line of sight directly into patient rooms,” says Still. “They can observe the patient, see interactions with providers, and can tell when a crisis is going on. That enhances everyone’s comfort.“

“Nurses stations have a line of sight directly into patient rooms,” says Still. “They can observe the patient, see interactions with providers, and can tell when a crisis is going on. That enhances everyone’s comfort.“

Monitors are placed throughout the unit so vital signs are visible to all nurses taking care of patients. Personal protective equipment (PPE) closets are often just outside the rooms, stocked with gowns, gloves, masks, etc.

“We purposely did not put a nook or sitting area between patient rooms,” says Pieroni. “Now we can pair patients according to acuity and still

Separate rooms for medical students, residents, APPs, and family conferences right on the unit also are essential, as are break rooms and water stations.

Newer Emory Healthcare ICUs have included “relaxation rooms” with massage chairs for staff and access to an outside garden or roof terrace.

A few human touches nearly everyone mentions are dimmers for the lights at night to synch with patients’ circadian rhythms and keeping the unit as quiet as possible during sleep hours.

Finding a place for all the machinery and accessories needed in critical care remains a challenge, but many ICUs are leaning toward large, undefined storage spaces and creative storage solutions in patient rooms.

“We actually engage process engineers to help us figure out how to shoehorn all the things we need into the space we have,” says Jabaley. “I want the units to be flexible enough to accommodate patients and technologies 20 years into the future.” EHD

SUMMER 2023 23

Lifting All Boats

EMORY’S NEW EVP FOR HEALTH AFFAIRS PERSONIFIES SERVANT LEADERSHIP

By Martha Nolan

By Martha Nolan

If you want to meet Emory University’s new executive vice president for health affairs, you shouldn’t look for him in his office. Instead, you are more likely to find him striding across campus, visiting researchers in their labs, and walking the halls of hospitals and clinics. That’s how Ravi Thadhani gets to know the institutions he leads.

At Mass General Brigham, where he was chief academic officer and dean for faculty affairs at Harvard Medical School, Thadhani says he visited every square foot of the institution’s two and a half million square feet of research space. It was the best— and perhaps the only—way to truly understand the experiences, the challenges, and the mindset of the system’s physicians, nurses, researchers, care team members, and staff as well as to connect with them on a personal level.

“In his position, Ravi could have easily insisted people come to his office in the corporate headquarters,” says Seun Johnson-Akeju, anesthetist in chief at Massachusetts General Hospital. “Ravi has a way of personalizing meetings. He would often take meetings in everyone else’s offices across our different hospital and research campuses. He goes out of his way to make sure people around him are seen, heard, and valued.”

On the first of January, Thadhani assumed the role of executive vice president of health affairs as well as executive director of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center (WHSC) and vice chair of Emory Healthcare Board of Directors. He is a renowned researcher in kidney disease and preeclampsia—a serious blood pressure condition that can occur during pregnancy. His discoveries have made the

24 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

leap from bench to bedside. A test he developed to predict the onset of preeclampsia has been in use in Europe for years and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the US. Thadhani is a skilled administrative leader who has overseen the integration of research, education, and clinical functions at Mass General Brigham. He is also a committed mentor who has helped launch and support the careers of scores of younger researchers inside and outside of his specialty.

“Dr. Thadhani is a dynamic and innovative leader for Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center,” says Emory President Greg Fenves. “He has deep experience in delivering the highest quality health care, biomedical research, training health professionals, and serving the public to improve the health of all. He will inspire Emory’s talented doctors, nurses, frontline staff, faculty, and researchers to reach new heights of excellence. In his many years of academic health system leadership, he has never stopped his research and clinical work, which is a testament to his lifelong commitment to serving patients and improving community health.”

THE SEEDS OF A CAREER

Born in India and raised on Guam, Thadhani became interested in pursuing a career in medicine the way many do—by experiencing health problems within his family. “My mother was hospitalized almost every other month due to severe asthma,” says Thadhani. “I would go with her to the hospital, so I was exposed to that environment, and I became interested.”

Though neither of his parents finished high school, Thadhani was determined to pursue his education. And he did. With a loan from the government of Guam, he was able to attend the University of Notre Dame. He went on to get a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and a master of public health from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Over two college summer breaks, Thadhani worked as a de facto operating room scrub nurse at a Guam hospital. When several surgeons from the hospital mounted a mission trip to the Philippines, they asked Thadhani to join them. “They said, ‘We’re

not going to pay you. You’ll sleep outside in a hut. There is no power there save for a generator, and there are no cars,’ ” he says. “I said, ‘Sign me up.’ ” Both experiences solidified Thadhani’s desire to pursue a career in medicine. While he was in medical school, Thadhani’s father was diagnosed with kidney disease and subsequently underwent dialysis. Watching his father deal with the challenges of the progressive disease, he set his sights on specializing in nephrology—not just clinically but as a researcher as well. “I wanted to treat patients who were suffering from the same disease as my father,” says Thadhani. “But I also wanted to do research so I could figure out how to help people with kidney disease survive longer with a better quality of life.”

FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

Thadhani’s research into kidney disease has run the spectrum from basic science to animal studies to human clinical trials. The brass ring, however, has remained just out of reach. While advances in medications and treatment can delay the onset of dialysis, and while dialysis and transplantation extend the life spans of people with chronic kidney disease, Thadhani and others in the field have not yet been able to find the magic intervention to extend the life expectancy of people once they get on dialysis, which remains three to four years.

Thadhani’s many dialysis studies, while they have not yet yielded a breakthrough, have laid the foundation for future studies that may meet with more success. “It’s been a very humbling experience,” he says. “All the animal, observational, and human studies I have done have not been able to uncover an intervention to extend the lives of patients on dialysis. But everything we’ve learned during the process of those studies will inform future research. Hopefully, one day we will be able to crack the ceiling in making a difference in these patients’ lives.”

Though Thadhani selected kidney disease as the area of his research focus, another area caught his attention and became his true passion—preeclampsia. This disorder is characterized by high blood pressure in pregnant woman which, if untreated, can be fatal for both mother and baby. A common

SUMMER 2023 25

“He has deep experience in delivering the highest quality health care, biomedical research, training health professionals, and serving the public to improve the health of all.

Emory President Gregory L. Fenves

treatment for preeclampsia is delivering the baby early, a process that usually resolves the problem for the mother but can lead to myriad issues for the premature infant.

Thadhani became hooked when he discovered research into this area was noticeably lacking but in dire need.

Preeclampsia is the third highest cause of maternal mortality in the US, and it affects five percent to seven percent of pregnant women worldwide. Black women have a threefold to fivefold increase in risk of suffering from preeclampsia than White women. And women who have hypertension during pregnancy are more likely to get kidney disease in future years and more likely to undergo dialysis.

Compounding the problem, health care providers had no way to predict which pregnant women would develop preeclampsia. “A woman can appear completely normal and feel terrific and within 24 hours go into a coma,” says Thadhani.

So Thadhani and his colleagues set out to identify a marker that could predict the onset of preeclampia, and they found it. A protein released by the placenta serves as a harbinger for the condition, and that protein can be detected in the blood weeks before the patient falls ill. Thadhani and his colleagues licensed the technology, and it has been in wide use in Europe for more than seven years. A recent study of 1,000 women in the US showed the marker works equally well for women from diverse backgrounds, and the FDA has approved the technology as a standard test in US hospitals. “We look forward to this test becoming widely available in the US,” he says.

shown that this therapy can allow women to extend their pregnancies to 30 weeks or 32 weeks, keeping mother and baby safe. This therapy is being tested for approval in Europe and the US.

THE SERVANT LEADER

In his post as chief academic officer and dean for faculty affairs at Mass General Brigham, Thadhani oversaw the system’s research, education, and health delivery at its medical centers. In recent years, his focus has been on integrating the many disparate units—a task that requires both vision and tact.

“There are many talented and highly motivated professionals at Mass General Brigham, so efforts to change the way things have always been done can be difficult,” says Robert Higgins, president of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “But Ravi personifies the servant leader. He listens and provides valuable insight without necessarily telling people what they have to do but leading them toward it.”

“Ravi would often take meetings in everyone else’s offices across our different hospital and research campuses. He goes out of his way to make sure people around him are seen, heard, and valued.”

Within the research enterprise, Thadhani worked to get away from the practice of each hospital doing its own research and move toward a unified, and more successful, approach. “Instead of competing against each other for grants, we are now coming together, and in this way, we’ve been successful on another level,” says Thadhani. “For example, in the last year and a half we were able to get several post-acute sequelae COVID grants totaling $60 million primarily because we brought together research teams from across the system. If each unit would have applied separately, we would not have been competitive at the national level.”

Predicting preeclampsia is valuable. Preventing it would be even better. For this goal, Thadhani drew on his expertise in dialysis, a process in which the blood of a kidney disease patient is removed via a needle from the arm, run thought a filter to remove the wastes and toxins that have built up, and returned—filtered and cleansed—through a different needle. Thadhani devised a similar mechanism to remove just the offending protein from the blood. His studies have

Seun Johnson-Akeju, anesthetist in chief at Massachusetts General Hospital

Thadhani has brought the same unified approach in research administration, streamlining agreements that historically took three months to complete down to less than 30 days and reducing the turn-around time for grants from several weeks to a couple of days. He has consolidated vendor agreements across the system, saving hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars. And he has integrated the educational component, so the system’s 2,500 residents and fellows can float seamlessly between hospitals to get

26 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

the educational opportunities that best suit them.

He accomplished all of these feats by focusing on people rather than numbers. “When tasked with Mass General Brigham system integration priorities, Ravi’s approach was to bring teams together to develop shared patient-centric goals,” says Johnson-Akeju. “You left those meetings confident in his leadership and vision, and with the firm understanding that a rising tide was about to lift all our boats.”

EVERYONE NEEDS A CHAMPION

Over the course of his career, Thadhani has won numerous awards. He says, however, that he is most proud of awards won by the numerous scholars he has mentored. Indeed, his track record for mentorship is extensive, particularly among women and underrepresented staff, trainees, and faculty. Consider a recent, rather spur-of-the-moment dinner Johnson-Akeju threw for Thadhani prior to his departure from Mass General Brigham. “I called several people whom Ravi had mentored and invited them to an intimate dinner celebration,” he says. “Every one of them said yes, no questions asked, and some of them flew across the country to join us in Boston.”

Mentoring others comes naturally to Thadhani because he benefitted from generous mentors at various stages in his career.

Chief among them is his wife of 27 years, Valerie,

a primary care physician who has traded practicing medicine for teaching elementary school children with learning disabilities. “She has helped me understand empathy. She has helped me understand mental illness—she has experienced that in her family,” says Thadhani. “If someone were to ask me why I am where I am today, I would say it is my wife times ten.”

AIMING FOR THE NEXT LEVEL

When Thadhani joined Emory on January 1, he succeeded David Stephens, who served as interim executive vice president for health affairs beginning September 1, 2022. Stephens succeeded Jon Lewin, who had held the post since 2016.

Thadhani comes to Emory with a mandate. “What I heard from board members and leadership was a real desire to move to the next level,” he says. “This organization is aiming to be one of the premiere academic medical institutions in the country. The leadership team here is committed to making Emory a true national powerhouse.”

To reach that lofty goal, Thadhani will start by walking. “I will throw some granola bars in my backpack, put on my walking shoes, and go out to meet people where they are,” he says. “I’ll spend my first six to twelve months getting to know the special sauce that makes Emory what it is.” EHD

SUMMER SUMMER 2022 29 27

PHOTO JACK KEARSE

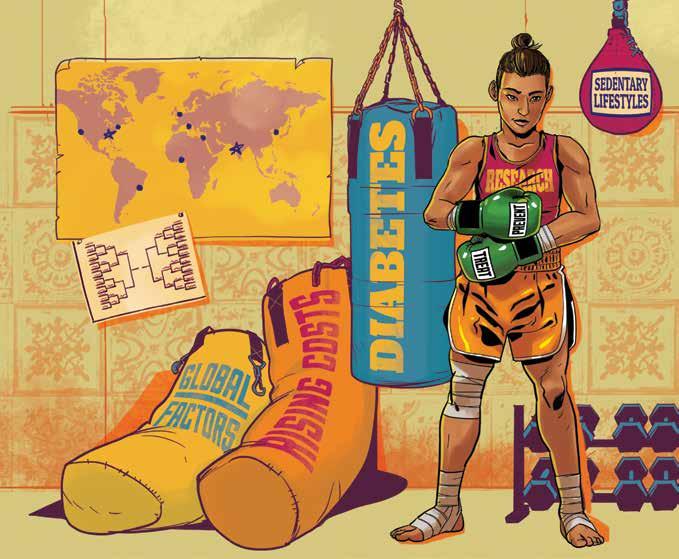

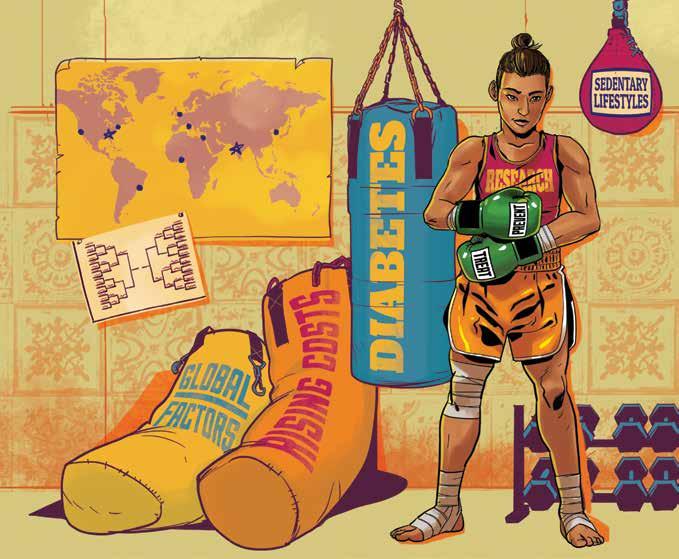

DEFEATING DIABETES

BY JIM AUCHMUTEY • ILLUSTRATIONS CHARLIE LAYTON

28 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

K.M. VENKAT NARAYAN HELPED WRITE THE PLAYBOOK FOR FIGHTING DIABETES at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It’s a familiar public health mantra—exercise, diet, weight control, and medication if necessary. So it stood to reason he would fall back on the advice he had created when Emory University recruited him to start the Global Diabetes Research Center at the Rollins School of Public Health some 15 years ago.

But in the center’s first project abroad in India, where Narayan was born and raised, he discovered that this prescription in fact didn’t work for everyone.

“My assumption at the time was that whatever we had learned in the United States and Europe would work elsewhere,” says Narayan, who serves as the Ruth and O. C. Hubert Chair in Global Health at Rollins. “I believed that we could extrapolate that knowledge in India or Africa or wherever. The sobering fact is that you cannot. I remember with great embarrassment some of the talks I gave in India from 2007 to 2009. I was proselytizing the role of obesity in

diabetes, which is what we did in the US, but we realized over time that we were dealing with something more complicated and possibly different.”

Many people in India were developing diabetes at earlier ages than patients in the US and without being particularly overweight. Diabetes, it appeared, was even more complicated than the worldwide authorities on the disease realized.

The center Narayan founded was set up to investigate and prevent one of the fastest-growing chronic diseases on the planet. More than half a billion adults have diabetes, and the International Diabetes Foundation projects that number will swell to three-quarters of a billion by 2030.

Diabetes is, in all regards, a noncommunicable pandemic—one that resides at the intersection of globalization, economics, and health care.

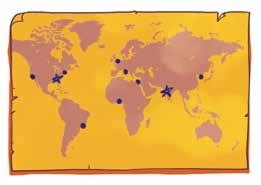

The center has grown with the problem, expanding from one researcher in 2008 to more than 150 faculty and staff members in 2022, spread across schools and departments at Emory as well as at partnerships institutions Georgia Tech and

SUMMER 2023 29

An innovative global approach to reducing diabetes—a growing pandemic that affects more than a half-billion adults worldwide—is opening new ways to prevent, treat, and potentially eradicate it.

K. M. Venkat Narayan is the co-director of the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center and Ruth and O.C. Hubert Chair in Global Health at Rollins.

the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. During that time, the center also has forged partnerships with eight major research universities and institutions total. And it now holds investigative partnerships in 21 countries on six continents, with an emphasis on research in South Asia and Africa.

“There are plenty of diabetes centers around the US, but we’re the only one with such a global focus,” says center co-director Mohammed K. Ali, William H. Foege Distinguished Professor of Global Health at Rollins.

Not that the center doesn’t address diabetes in Georgia. Far from it. With funding from the National Institutes of Health, the center founded the Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research with Georgia Tech and the Morehouse School of Medicine to investigate the role of health care equity in preventing and managing the disease.

“Georgia is in the middle of the diabetes belt,” Narayan says. “We have counties in the state where the life expectancy is as low as Mongolia or North Korea. What this means is that even though we have all this great science available, our delivery systems are lacking. We’re studying ways to narrow the gap and improve equity.”

In acknowledgement of the worldwide crisis—and the need for a more expanded role—Emory earlier this year gave the center an administrative promotion, realigning it to report directly to the Woodruff Health Sciences Center. The move gives it a more prominent place alongside the Winship Cancer Institute, the Emory Brain Health Center, and other efforts with a universi-

ty-wide footprint.

It also means the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center—as it’s now known—will receive greater funding and higher visibility.

“Through our global research so far, we’ve established that diabetes is a far more complex disease than originally thought, and that it affects different populations in very different ways,” says Jonathan Lewin, the former Woodruff Health Sciences executive vice president for health affairs. “By elevating the center, Emory can broaden its approach to understanding, preventing, managing, and ultimately curing a disease that affects hundreds of millions of people globally.”

Adds Narayan, “It gives us a path to widen our scope. There’s so much we still need to learn about the disease.”

One of the biggest mysteries is why diabetes presents such a different face in developing countries like India. The answer will almost certainly have implications for people in all countries—large and small, rich and poor.

LEADERS TRAIN FOR THE FIGHT

Venkat Narayan didn’t set out to study diabetes. Growing up in Bengaluru, in southern India, he didn’t think much about the disease during his youth in the 1960s because it seemed to afflict so few people.

After finishing medical school, Narayan moved to the United Kingdom for his clinical residency and grew interested in epidemiology. He took a tenured position at the National Health Service and a senior lectureship at the University of Aberdeen. He thought he and his wife,

30 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

Mohammed K. Ali “THERE ARE PLENTY OF DIABETES CENTERS AROUND THE US, BUT WE’RE THE ONLY ONE WITH SUCH A GLOBAL FOCUS.”

PHOTO KAY HINTON

Asha Krishnaswamy, a computer scientist, would live in Scotland for the rest of their lives.

But his career detoured after he co-wrote a paper about cardiovascular disease among Scots and its link to diabetes. The paper attracted attention, and he was invited to an international diabetes course in Cambridge, where he met many of the world’s leading experts on the disease.

One thing led to another, and Narayan soon found himself in the US working with the National Institutes of Health on a major investigation of diabetes among the Pima Indians of Arizona. That work, in turn, led him to Atlanta and the CDC, where he was hired to lead the diabetes branch and to help create a nationwide prevention and control program.

“There wasn’t a lot of diabetes intervention and prevention work being done before the 1990s,” he says. “The approach was, you either had it or you didn’t.”

The recognition of pre-diabetes—and the existence of a large population who could postpone or avoid the disease with lifestyle changes—at the CDC revolutionized the field. It showed that diabetes wasn’t an either/or proposition but a continuum that changes with age. And it was one of the biggest developments in diabetes research since the discovery of insulin, the hormone that regulates glucose, in a Toronto lab in 1921. Narayan and colleagues at the CDC also developed strategies and approaches for systemwide improvements in diabetes quality of care, something that has resulted in major declines in diabetes mortality and complications.

After a decade with the CDC through the early 2000s, Narayan came to Emory to head up the diabetes research center. In fact, in the beginning he pretty much was the center.

“We had little data and hardly any funding,” recalls one of his first hires, Solveig Cunningham, a professor of global health at Rollins who specializes in demographics and sociology. “One of the cool things about Venkat is the way he thinks outside the box. You would have expected him to bring in diabetes experts, but he wanted to bring in people with different skills and expertise and let them engage with diabetes. I had never worked with diabetes before I joined the center. All my work had been on childhood health.”

Another early recruit was Ali. Of South Asian descent, like Narayan, Ali is Pakistani but grew up in Africa, where his father moved as an expatriate. When he finished medical school in South Africa and won a Rhodes scholarship, Oxford University in the UK offered him two subjects for cardiovascular study—one focused on animals and the other centering on the links between obesity and diabetes.

He opted for the second, largely because of his family history. His mother was diabetic, and he had been overweight as a teenager.

“When I was 16, I was shorter and weighed 25 or 30 pounds more than I do now,” Ali says. “It was because of poor habits.”

During his time at Oxford, Ali heard a speaker from Atlanta, Jeffrey Koplan, a former CDC director who had become vice president for global

SUMMER 2023 31

health at Emory. He told the young Rhodes scholar about the diabetes research center Emory was starting and suggested he contact the founding director. Fourteen years later, Ali was named co-director of the center and Foege professor.

“We tinkered with our brand the first few years,” Ali says. “We weren’t sure how much we should stress the global aspect. We thought that might be a liability. But it was too important to our identity.”

As it turned out, that global focus led to some of the center’s most important discoveries.

NO BORDERS RESPECTED

During the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors and epidemiologists repeatedly emphasized that infectious diseases respect no borders. The same could be said of noninfectious chronic diseases. The forces of modernization that have driven the growth of diabetes—more sedentary lifestyles and an abundance of refined convenience foods, among others—don’t stop at borders either.

When the center began, Narayan says, diabetes research was grossly imbalanced. Low- and middle-income countries accounted for 80 percent of people with the disease worldwide, yet almost all the investigations had involved populations in richer countries in Europe and North America. There was a glaring need for broader and more diverse research.

The center focused on India, where Narayan had many contacts. It has since undertaken 24 research projects in the country, where diabetes has been growing at an alarming rate. The center works with long-term local research partners, careful to treat them as full collaborators.

“We have worked with Venkat and others at Emory for years,” says Nikhil Tandon, head of the endocrinology department at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. “The relationship is built on dialogue, understanding of local contexts and perspectives, and on occasion even agreeing to disagree. Communications are frank but built on logic and reason.”

The longest-running project is the CARRS Cohort—CARRS stands for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in South Asia—which has followed the health of 22,000 people in two Indian cities since 2010. Narayan thinks of it as a study of the natural history of diabetes and its complications. It’s more than four times larger than one of the best-known longitudinal studies in medical history, the Framingham Heart Study, which tracked 5,209 adults in Framingham, Mass., starting in 1948, and found that high blood pressure and cholesterol were risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

CARRS is already yielding a similarly significant realization about diabetes. It isn’t just two diseases: Type 1, the less prevalent variety that used to be known as juvenile diabetes; and Type 2, the more common condition associated with obesity and aging—what used to be known as adult-onset diabetes. Instead, it’s actually a spectrum of diseases or multiple phenotypes.

Narayan and others at the center first reached this insight by noticing that many people with diabetes in India were younger and not obese.

32 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

LOW- AND MIDDLEINCOME COUNTRIES ACCOUNTED FOR 80 PERCENT OF PEOPLE WITH THE DISEASE WORLDWIDE.

A DISEASE OF Staggering Impact

These statistics prove without a doubt that diabetes is a pandemic of epic proportions that affects hundreds of millions of lives every day in a variety of ways.

WORLDWIDE IMPACT

537

MILLION ADULTS HAVE DIABETES.

The number is projected to reach 643 million by the end of the decade.

THREE IN FOUR ADULTS with diabetes live in low- and middle-income countries.

ECONOMICS

IN THE UNITED STATES

11.3% of the nation’s population has diabetes.

That’s a 42% increase in the past 10 years.

48.8%

OF AMERICANS OVER 65 have diabetes or pre-diabetes.

The US has the highest diabetes rate among developed nations.

ETHNICITY

WHO HAS DIABETES?

$327

Diabetes is associated with BILLION A YEAR in direct health care expenditures and lost productivity in the US.

Worldwide, it represents 11.5% of all health resources globally.

Approximately

$966

BILLION ANNUALLY is spent on diabetes.

MORTALITY

Diabetes is the SEVENTH-LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH in the US. Worldwide, diabetes is associated with 6.7 MILLION DEATHS ANNUALLY.

14.5% of AMERICAN INDIANS AND ALASKA NATIVES

12.1% of NON-HISPANIC BLACKS

11.8% of HISPANICS

9.5% of NON-HISPANIC ASIANS

7.1% of NON-HISPANIC WHITES

EDUCATION

OF THOSE WHO HAVE DIABETES

13.4% didn’t finish high school

9.2% have a high school diploma

7.1% have some higher education

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Diabetes Association, International Diabetes Foundation

SUMMER 2023 33

“They didn’t really look like many of the people with diabetes you see in the US,” says Mary Beth Weber, an assistant professor of global health and epidemiology at Rollins who worked with one of the center’s prevention programs in India. “They looked like they didn’t need to lose weight.”

Narayan and his research partners theorized that they were seeing a new form of diabetes. In the West, most people develop the disease because their bodies, with age and obesity, grow resistant to the insulin their pancreas produces. In India, the researchers proposed, the problem was that the pancreas wasn’t producing enough insulin to begin with.

In essence, there were at least two forms of Type 2 diabetes: insulin-resistant and insulin-deficient. The question is why.

“This is the heart of where our research is going,” Narayan says. “There are a pair of clues so far. One is that 90 percent of the world missed the industrial revolution and is still recovering from many decades of relative undernourishment. Perhaps their bodies adapted for survival.”

The second clue? Narayan says that the endocrine part of the pancreases in India appear significantly smaller compared to the ones in Western countries. It’s possible they’re unable to secrete as much insulin. Narayan and colleagues like Rollins Assistant Professor Lisa Staimez are in the process of establishing a pancreatic biobank in India in collaboration with similar biobanks in the US.

Wherever the research leads, Narayan believes the US has as much to learn about diabetes from India as the other way around. Insulin-deficiency occurs in Americans as well, just not as often, and the new research can help in treating it.

“We also have a lot to learn about how to manage diabetes at scale and at a lower cost,” he says. “In India, they’re forced to manage diabetes at a fraction of the cost we do. Perhaps we could adapt parts of that system and deliver it to a population in, say, Georgia and save money.”

WINS AND LOSSES IN A COMPLEX BATTLE

The outlook for diabetes is getting both better and worse at the same time. Treatment and prevention of the disease is better than it has ever been. As a result, the death rate from diabetes has declined in developed countries in North America and Europe.

But, simultaneously, medical expenditures associated with the disease have risen.

Diabetes is notorious for causing health complications throughout the body, from vision and kidney failure to stroke, heart disease, and amputations. With so many debilitating consequences, it’s no surprise that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services says diabetes is the single biggest contributor to its rising costs.

The ominous news is that the diabetes pandemic will almost certainly get worse before it gets better. Projections show the disease afflicting a rising percentage of the global population for the foreseeable future.

“I wish I could say it’s leveling off

34 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

in the US, but I can’t,” Ali says. “We have all this information about how to prevent and mitigate diabetes, but we just haven’t been able to engage people to make enough of the changes they need to make. We’re not getting a shift in the broader population on obesity, and thus not on diabetes, either.”

The Emory Global Diabetes Research Center today studies diabetes on dual fronts: investigating the disease itself and exploring better ways to prevent and treat it.

It’s a wide-ranging approach that considers everything from health equity and access disparities to the effect of toxins and pollution on the pancreas.

“We are an ecosystem of interdisciplinary diabetes research that runs from basic science to epidemiology to clinical trials to translation sciences and health technology,” Narayan says.

One promising research frontier is the role of artificial intelligence (AI) and data mining. Joyce C. Ho, an associate professor of computer science, came to the center in 2017 to test whether data could improve prevention and treatment of a chronic disease.

“Amazon, Target, and Walmart can make good recommendations to individuals about products they might like to buy based on the information they gather online,” she says. “Why can’t we do the same thing when it comes to preventing diabetes? Why can’t we layer information about your environment and suggest better ways for you to eat and exercise. These social determinants of health are so important.”

Ho isn’t sure exactly how it will manifest, but she believes AI has the

potential to revolutionize the field. “When insulin was discovered 100 years ago,” she says, “it transformed diabetes care. AI could transform diabetes care as much as insulin. I could see it starting to happen in the next five years.”

Ali believes data mining could be just as transformative in allowing doctors to target diabetes treatment more precisely.

“The more layered information we process together, the better we’ll be able to match people with interventions that work for them,” say Ali. “This is a nascent science, and there are few actual trials, but we’ve seen enough to signal that it’s worth pursuing. And it doesn’t hurt that Emory is investing heavily in artificial intelligence.”

Like cancer, diabetes is a disease that was once thought of in monolithic and almost unapproachable terms. But as researchers’ thinking has been fine-tuned, the disease’s complexities may actually hold solutions for fighting it more precisely and effectively.

“It’s human nature to oversimplify things,” Ali says. “We did that with diabetes. But now that we know that it’s much more complicated, we’re not looking for a silver bullet that works for everyone. We’re looking for the bullet that works for you as an individual—this is precision medicine and precision public health.” EHD

SUMMER 2023 35

Joyce C. Ho

“WHEN INSULIN WAS DISCOVERED 100 YEARS AGO, IT TRANSFORMED DIABETES CARE. AI COULD TRANSFORM DIABETES CARE AS MUCH AS INSULIN.”

THE RENEWED LIFE AND TIMES OF ALGE CRUMPLER

BY MAUREEN MCCARTHY • PHOTOS COURTESY ALGE CRUMPLER

BY MAUREEN MCCARTHY • PHOTOS COURTESY ALGE CRUMPLER

AFOUR-TIME NFL ALL-PRO TIGHT END WITH A CAREER SPANNING A DECADE WITH THE FALCONS, PATRIOTS, TITANS AND JAGUARS, ALGE CRUMPLER WAS A LEGEND ON AND OFF THE FIELD.

Crumpler, 44, built a reputation as a leader at his position and a leader among his teammates. Like many elite athletes, he struggled to make the transition from the field to post-professional-play life. The dream of NFL glory, the support of teammates, and the help of pro trainers provide athletes with the structure to maintain peak physical shape. In particular, the regimented structure of the league is paramount in helping athletes maintain their laser-like focus with workouts, nutrition, and communication.

36 EMORY HEALTH DIGEST

SUMMER 2023 37

AFTER FOOTBALL, THERE WAS NO ROUTINE TO FOLLOW, NO POSITION TO COMPETE FOR, NO SUPER BOWL TO AIM FOR. CRUMPLER LOST THE MOTIVATION TO EXERCISE, AND FOOD BECAME HIS COMFORT.

Crumpler spent more than 20 years keeping his body in peak condition. He was at the top of his game throughout high school in Greenville, North Carolina, and college at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

After Crumpler got to the NFL, he was consistently taking part in highly structured training routines, with strong coaching and a support system to optimize his performance.

Life after professional sports

After football there was no routine to follow, no position for which to compete, no teammates to collaborate with, no Super Bowl to aim for. In short, he lost his motivation.

His body ached, he stopped exercising regularly, and food became his comfort.