26 minute read

Children and COVID

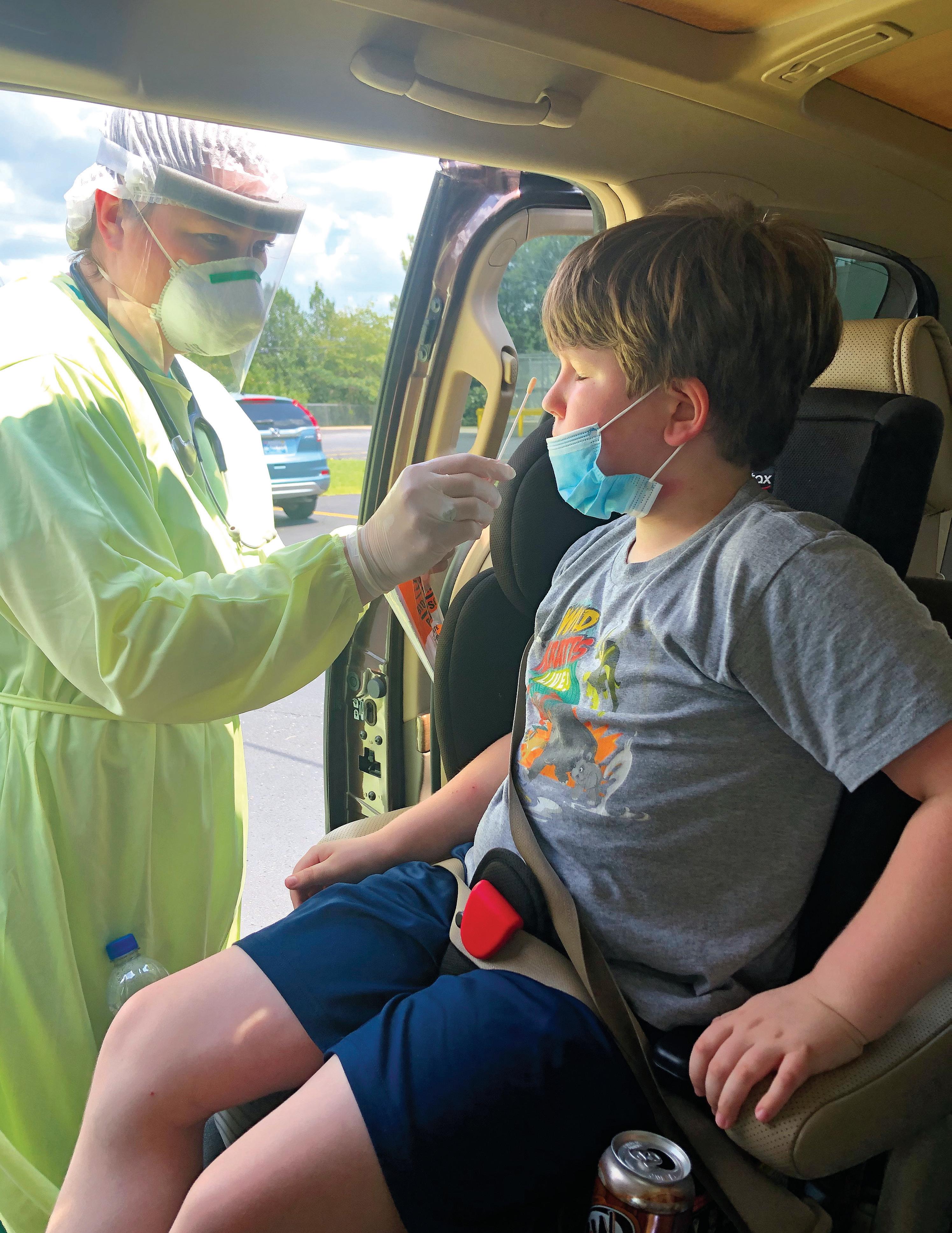

Sam Friday, 8, gets a COVID-19 test near his home in Alabama after experiencing troubling symptoms, including stomach and chest pains.

CHILDREN AND COVID-19

PEDIATRIC CASES OF THE NOVEL CORONAVIRUS RANGE FROM ASYMPTOMATIC TO A SERIOUS INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME. MORE IS BEING LEARNED WITH EACH NEW CASE.

BUT THE UNKNOWNS ARE STILL DAUNTING, FOR FAMILIES AND DOCTORS.

By Mary Loftus

Hannah Friday doesn’t want to hear anyone say, “Kids don’t get sick from COVID.” In fact, it infuriates her.

That’s because she watched her son Sam suffer intensely from the virus.

“To have an 8-year-old beg you to take him to the hospital …” she says, her voice trailing off.

Patrick and Hannah Friday, both Emory Candler School of Theology alumni and former missionaries, live in Birmingham, Alabama, with their twins, Sam and Clinton, where Patrick leads a United Methodist church and Hannah is an adjunct professor at Beeson Divinity School at Samford University.

At the end of June, they took their son to their local ER with a severe stomachache, pain in the area of his spleen, and severe pain in his chest (“He said it was 10 out of 10 pain, for at least a week”). He was also dragging one of his legs behind him.

Initially, Sam was given two diagnoses: indigestion and constipation. “I had done research and knew he had symptoms that children get with COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C),” says Hannah. “I’m in a high-risk group and so I asked that the whole family be tested. Everyone we called said no, we’re not going to test you, just assume you have it and quarantine.”

The Patricks had been extremely careful, isolating and masking, with Hannah going grocery shopping every two weeks and Patrick switching to “drive-in” services at church.

The pandemic hit home for Emory alumni Hannah and Patrick Friday and twin sons Clint and Sam (l-r, above, at Patrick’s church in Birmingham) when Hannah and Sam tested positive for the virus.

Sam “is our calm child, and if you looked at him, he looked healthy . . . but that wasn’t the case,” says his mom, Hannah Patrick, who also tested positive for COVID-19.

“We only took the kids out three times,” Hannah says, but at one of those gatherings—a family funeral held outside at a farm—she believes they were exposed to the virus.

On July 1, Sam’s test came back positive. They were told to isolate Sam from the rest of the family. Instead Hannah moved the boys into her room, with Sam sleeping on one side and Clint on the other.

“I couldn’t leave my 8-year-old son in his room and bring food to him,” Hannah says. “He was sleeping with me, I had him by my side.”

Finally, the entire family was tested, and this time Hannah tested positive for COVID-19 as well. “It was a relief to finally get the test and the results, actually.”

Hannah’s symptoms included a severe headache and chills that caused her to bundle up in heating pads and an electric blanket. She could feel the virus moving down into her lungs. “At my worst, I didn’t even have enough energy to walk outside,” says Hannah, who started intense self-care, including steam with eucalyptus, immune boosters, and over-the-counter medications. “I also had steroid inhalers and a nebulizer, as well as a pulse oximeter and blood pressure cuff at home.”

Patrick was worried and not sure what to do. “To see your child affected by COVID in such a mysterious way, and then your wife catches it,” he says. “It was pretty overwhelming.”

During the worst of his symptoms, Sam asked his parents, “Do you have to breathe in heaven?”

At the same time that her family was suffering, Hannah was seeing all the doubters on social media, people saying COVID was fake, children couldn’t get it, and there was no need for masks.

“No illness should be politicized,” she says. “I was actually questioned by people online, after we knew that Sam had it. I posted a photo of him in the hospital. People need to know it is real and children can get sick from it.”

COVID-RELATED SYNDROME

IN CHILDREN

Children can, indeed, get COVID-19, says Preeti Jaggi, associate professor of pediatric infectious diseases and a clinician at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. And while pediatric deaths from COVID are rare, and 94% of children’s cases are considered mild to moderate, some children can become seriously ill. Children with underlying medical conditions are particularly vulnerable.

“Kids can become ill from COVID requiring hospitalization, just not at the same rates as adults,” Jaggi says.

A subset of children who may have initially had very mild to undetectable illness can become critically ill. These are the ones suffering from COVID-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C.)

MIS-C is a condition where body parts can become inflamed, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal (GI) organs. As with the Fridays’ son Sam, one of the earliest symptoms can be GI distress, so the symptoms could be mistaken for a stomach bug, indigestion, or food poisoning.

“We do not yet know why some children develop MIS-C. MIS-C can be serious, even deadly, but most children who were diagnosed with this condition have gotten better with medical care,” reads the CDC site on MIS-C.

Symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, neck pain, a rash, bloodshot eyes, and feeling extremely tired.

“MIS-C was only identified on April 27, so basically clinical care and research started at the same time,” Jaggi says.

As well as caring for children with COVID and COVID-related illnesses at Emory Healthcare and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Jaggi and colleagues have been conducting studies as rapidly as they can collect data, hoping to find out more about pediatric transmission, manifestation, and treatments.

For example, in their study on “Burden of Illness in Households with SARS-CoV-2 Infected Children,” published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, they investigated the dynamics of illness among household members of SARS-CoV-2 infected children who received medical care (sample size was 32 children who had tested positive for COVID-19).

“We identified 144 household contacts: 58 children and 86 adults. Forty-six percent of household contacts developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 disease. Child-to-adult transmission was suspected in seven cases,” the authors said.

Jaggi has also been involved in studies to: n describe the similarities and differences in the evaluation and treatment of MIS-C at hospitals in the United States, in the absence of evidence-based therapies for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. n measure SARS-CoV-2 serologic responses in children hospitalized with MIS-C compared to COVID-19, Kawasaki disease, and other hospitalized pediatric controls.

“Understanding the epidemiology and clinical course of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and its temporal association with COVID-19 is important, given the clinical and public health implications of the syndrome,” says Jaggi, who has seen about 30 to 40 children diagnosed with MIS-C.

Some children’s blood serum was stored and they were diagnosed retrospectively, she says.

Jaggi has long had a research interest in Kawasaki disease, an inflammation of the blood vessels that usually affects children younger than 5. At first, she and many other experts thought that’s what they were seeing in children with this type of severe inflammation, but “they were older than the norm—most were over 5 years of age and the median age was 9.”

And, unlike the normal adult symptoms of COVID-19, Jaggi and her fellow clinicians were seeing children

s

who didn’t have respira- Fraternal twins Sam and Clint enjoy outside time tory symptoms or coughs, at home, where their family spent most of their time but presented with fever, isolating during the pandemic. gastrointestinal symptoms, and hypotension. “They were really sick, it was scary,” she says. “Some needed oxygen, their bellies were distended. There were cases of severe cardiac dysfunction.”

The belief now among the CDC and medical experts after studying cases nationwide, says Jaggi, is that MIS-C has two different phenotypes: “The first are children who do not test PCR-positive (by nasal or throat swab saliva tests) but are only identified through serologic testing, which probably means an old infection. While caring for young paThen there are the children who test positive tients with COVID-19, Emory from the swabs, and in that case, MIS-C overlaps and Children’s Healthcare with acute COVID.” pediatrician Preeti Jaggi and

Some adults experience a lot of inflammacolleagues also have been tion with COVID-19 as well, which is why the conducting research on how the virus affects children. -C was added to the diagnosis, meaning specifically multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

And MIS-C is, by definition, serious: a child must be sick enough to have stayed in the hospital in general for about 48 hours to earn the diagnosis.

There may even be lingering cardiac issues. “We are tracking everything in these kids,” Jaggi says. “We are carefully monitoring their follow-up with specialists, like cardiology, to make sure they don’t have long-term issues with their hearts.”

The Fridays’ pediatrician told Patrick and Hannah the same about Sam—that he might have lingering effects from the virus.

The Fridays met at Emory, graduated from Candler School of Theology in 1998, married in 2000, and later found out they were having twins. They named them after two United Methodist ministers and missionaries who died in an earthquake in Haiti—Samuel and Clinton.

The twins are in no way identical—Sam is larger and steady; Clint is smaller and more dramatic. Where one goes, they both go, says their mom.

So when Sam started complaining about his pain, his parents knew something serious was wrong. “He is our calm child and if you looked at him, he looked healthy. So even doctors were saying, ‘He’s fine, just take him home.’ But that wasn’t the case.”

Hannah and Patrick want to let other parents know that they need to be advocates for their children, especially with a new disease, like MIS-C, that even some of the medical workers they encountered had never heard of.

Hannah and Sam are feeling better, although they are both suffering some aftereffects. “My body has not quite regained its ability to regulate my temperature, and I am still having pretty severe joint pain,” she says. “Sam is starting to do a little exercise, including tennis practice.” After Hannah told people that she and Sam had COVID, and posted a picture of him at the hospital on social media, other people started writing to her to let her know they or their family member had it too, she says: “A month later, everyone knew someone who had it.” n

COVID-19 Helpers

A book to let children know ways they can help during the pandemic, by author Beth Bacon and illustrator Kary Lee, won the Emory Global Health Institute COVID-19 children’s eBook competition, along with a $10,000 prize. The contest, which was aimed at providing information for 6- to 9-year-olds, was proposed by Jeff Koplan, director of the institute and VP for Global Health at Emory, and inspired by his grandchildren’s questions. To view the winning and runner-up books, go to: links.emory.edu/covidkids.

COVID-19 HELPERS

by Beth Bacon and Kary Lee

The Paradox of COVID-Related Inflammation in Children

Measuring blood antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may distinguish children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a serious but rare complication, say researchers at the School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Children with MIS-C had significantly higher levels of antiviral antibodies—more than 10 times higher—compared with children with milder symptoms of COVID-19, the research team found. The results, published in the journal Pediatrics, could help doctors establish the diagnosis of MIS-C and figure out which children are likely to need extra anti-inflammatory treatments. Children with MIS-C often develop cardiac problems and low blood pressure, and require intensive care. The high antibody levels may represent an exaggerated immune response or a delayed complication of COVID-19, or a combination of both, says Christina Rostad, assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory and an infectious disease specialist at

Children’s. Senior author Preeti Jaggi, associate professor of pediatrics (infectious disease) at Emory School of Medicine and Children’s, says that “one of the challenges in interpreting these findings in children with MIS-C is that we do not know when they were actually infected with the virus. The rapid emergence of MIS-C has required physicians at Children’s and researchers at Emory to work collaboratively to quickly understand the clinical course of the disease, treatments, and pathophysiology and has required a huge team effort from clinicians and basic scientists.” Children’s physicians have continued to see cases of COVID-19, and more than 50 cases of MIS-C have met the definition of MIS-C requiring hospitalization, in the Children’s

Healthcare system. “These cases underscore the importance of all the efforts we are taking as a community to decrease transmission of this virus. By wearing a mask, washing your hands, and avoiding large gatherings, you may be saving someone’s life,” Rostad says.

Patients with MIS-C usually present with persistent fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and skin rashes, and severe cases have low blood pressure and shock, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How MIS-C develops remains mysterious. Recent reports have suggested that it arrives in a second wave of inflammation, after the initial viral infection. None of the children with MIS-C studied by the

Emory and Children’s researchers recalled having a previous fever or respiratory illness, even though they had high levels of antiviral antibodies. However, the majority tested negative for an active infection at the point of their hospitalization. The authors remark that it “seems paradoxical” that children without preceding symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Inflammation of eyes Inflammation of mouth

Swollen lymph nodes

Extremity swelling with redness, rash, skin peeling

Renal failure

Nausea, vomiting, and pain, diarrhea

Lab evidence of current or past infection with SARS-CoV-2

develop such intense immune responses. It may hint that although some children with active infections lack symptoms, they are still capable of developing robust immune responses. “These studies provide supportive evidence that MIS-C represents an aberrant immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children,” Rostad says. “However, the mechanisms of this disease process and the reasons some children develop symptoms while others don’t remain areas of active research.” When they first came to the hospital, children with MIS-C mainly displayed gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Several of them developed myocardial dysfunction with decreased ejection fraction—a measure of the heart’s ability to pump blood. All patients with MIS-C needed to be hospitalized in intensive care because of low blood pressure. Between March and May 2020, the researchers studied 10 children hospitalized with MIS-C, 10 with symptomatic COVID-19, five with Kawasaki disease, and four hospitalized “control cases.” Kawasaki disease is a pediatric inflammatory disease affecting blood vessels, including the coronary arteries, which shares some features with MIS-C. The average age of the children with MIS-C was 8.5 years. The time elapsed between symptom onset and antibody samples being taken varied, generally between zero and 20 days, with a few in the MIS-C group later than 20 days. The researchers used tests for antibodies against the receptor binding-domain Fever, headache, muscle aches, lethargy

Low blood oxygen, lung problems, chest pains

Inflammation of heart muscle, low blood pressure, sped-up heart beat (100+ per minute) Low platelet level in blood

“Making a COVID-19 vaccine is hard. Making

one for kids is

of the viral spike protein harder.” and the viral nucleocapsid protein using assays “We should not be leaving children developed in the laboratory of coauthor Jens behind in the warp-speed efforts, Wrammert, assistant and that’s clearly what we’re doing professor of microbiol- now,” says Evan Anderson, a pediatogy and immunology. ric infectious disease researcher at They also performed live-virus neutralization assays in the laboratoEmory. Along with colleagues at the National Institutes of Health, he’s ry of coauthor Mehul been developing a protocol to help Suthar, assistant profes- COVID-19 vaccine makers navigate sor of pediatrics. the process of pediatric trials and The children with MIS-C were treated with compare the results for different intravenous immuno- vaccines. “I think there’s an imperaglobulin (a mixture of tive to get off our derrières and get donated antibodies) going on doing careful trials.”—from and half received corticosteroids, a common Wired, 8.14.2020. anti-inflammatory medication. Some of the COVID-19 group were treated with antiviral or immunomodulatory drugs such as remdesivir (four) and convalescent plasma (two).

All the children with MIS-C eventually returned home. Two of the patients with symptomatic COVID-19 were being treated for leukemia and died due to their underlying disease.—Quinn Eastman

Ready, Set...Pivot SCHOOL OF MEDICINE RESEARCHERS REFOCUS TO ADDRESS COVID-19

By Quinn Eastman, Shannon McCaffrey, and Rajee Suri

n Photos Jack Kearse

Within weeks after the pandemic began, Emory School of Medicine researchers, working with colleagues from across the university and at partner institutions around the globe, mobilized their resources and expertise to address the largest infectious disease threat to humankind in more than 100 years: COVID-19. Some researchers began anew while others pivoted from their existing work to address the new coronavirus. These COVID-19 activities span the spectrum of the disease—from advancing understanding of the virus to coming up with quicker and more accurate tests to finding treatments and a vaccine. Emory’s work is well positioned to go from bench to bedside because of the breadth and interdisciplinary nature of its research; its numerous research centers and facilities, which include one of the world’s largest national primate centers; and its comprehensive health system, which is hosting clinical trials for the next lifesaving drug, therapeutic, and vaccine. School of Medicine COVID-19 research projects have received more than $91 million in federal grants in FY2020. Here is a sampling of the work in progress:

THE NETWORK Emory is helping to lead the new COVID-19 Prevention Trials Network (CoVPN), which centralizes efforts to protect against the coronavirus. The federally funded network is recruiting and enrolling thousands of volunteers to participate in the large-scale clinical testing of investigational vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. CoVPN links four existing clinical trial networks including the Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Consortium (IDCRC) based at Emory. INVESTIGATOR: David Stephens VACCINES Clinics at Emory and affiliates are playing a key role in testing one of the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates. Co-developed by scientists at Moderna and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), mRNA-1273 was the first investigational vaccine in widespread human trials in the US. Early results have been encouraging; studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine examining Phase 1 of the trial showed the vaccine was generally well tolerated and stimulated an immune response.

Monoclonal antibodies

Viral cell Monoclonal antibody

Antigen-protein on the cell that can cause the immune system to respond.

The monoclonal antibody locks onto the antigen. This can cause the immune system to attack the viral cell.

Including the CoVPN, Phase 3 is expected to enroll some 30,000 volunteers around the country, with hundreds taking part at three Atlanta clinics. INVESTIGATORS: Evan Anderson, Colleen Kelley, and Nadine Rouphael

Work is also under way on a home-grown vaccine candidate. Funded by a two-year grant from NIAID, the effort is aimed at taking Emory’s extensive research on an MVA vaccine for HIV and adapting it for the new coronavirus. MVA is a harmless version of a poxvirus with a proven record of prompting long-lasting antibody and T cell responses. MVA vaccines can be used in combination with other vaccines to enhance the immune system’s response. A trial in mice is complete, and nonhuman primate studies are in progress. INVESTIGATOR: Rama Amara

REPURPOSING DRUGS Could drugs already approved for one use be effective against COVID-19? Emory researchers are investigating drugs that have shown antiviral activity in cell culture for COVID-19 and in animals infected with MERS and SARS, coronaviruses similar to COVID-19. Since the drugs work at different points in the viral life cycle, they might work in combination with each other or with antivirals, like remdesivir. Other drugs being tested in novel cell culture assays may dampen the excessive immune response often seen in severely ill patients. All of these drugs are already on the market, widely available, and inexpensive. INVESTIGATORS: Rabindra Tirouvanzia, Joshy Jacob, Manoj Bhasin, Raymond Schinazi, Vikas Sukhatme

MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES Studies are also under way to gauge whether manufactured versions of infection-fighting antibodies are effective in protecting against and treating COVID-19. Produced in laboratories, these synthetic antibodies are known as monoclonal antibodies. The CoVPN is focused on monoclonal antibody testing efforts. Here are some of the trials being conducted at Emory: n A Regeneron–sponsored trial to test the effectiveness of a human monoclonal antibody cocktail. Emory is participating in two programs for REGN-COV2, which comprises two antibodies. One targets patients in the hospital with COVID-19, including those on ventilation; the other studies outpatients with the disease. n An Eli Lilly–sponsored trial is studying a monoclonal antibody candidate for treating

hospitalized, but noncritical, COVID patients. The drug candidate (LY-CoV555) is being tested in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients. In another trial, jointly funded by NIAID and Lilly, investigators will evaluate the same monoclonal for its ability to prevent moderate to severe COVID-19 in residents of nursing home and assisted-living facilities in Georgia. This statewide study is part of a larger, nationwide research project. n A NIAID-sponsored clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an experimental monoclonal antibody (LY-CoV555) in combination with an antiviral, remdesivir, for treating patients who have been hospitalized with mild to moderate COVID-19. n A study that will assess the efficacy and safety of the human monoclonal antibody, gimsilumab, in patients with lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19. Researchers have received a grant from Kinevant Sciences, which is part of the pharmaceutical that makes the drug compound. INVESTIGATORS:: Marshall Lyon, Nadine Rouphael, Sri Edupuganti, Michael Hart, Jens Wrammert, Carl Davis, Bradley Leshnower n Researchers are studying monoclonal antibodies from lampreys to better understand the new coronavirus. Lampreys are an ancient species of fish resembling eels and provide important clues for researchers about the evolution of our immune system and potential ways to fight new pathogens. The monoclonal antibodies produced by this project will be used for virus isolation and diagnosis and could support the work of other researchers to develop therapies. INVESTIGATORS: Max Cooper, Masayuki Hirano

THERAPEUTICS When the Food and Drug Administration this spring granted emergency–use authorization to use the drug remdesivir to treat COVID-19 patients, Emory shared in the good news. Emory is part of the Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Corsortium (IDCRC), and a global network of NIAID sites that tested the antiviral. Emory recruited more patients than any other site around the globe. Researchers are continuing to evaluate the longer-term impact of remdesivir, an experimental medication administered by infusion.

Emory is also taking part in the next iteration of the study, which combines remdesivir with baricitinib, an oral, anti-inflammatory drug already approved by the FDA for rheumatoid arthritis. The study will explore baricitinib’s ability to calm the hyper-inflammatory response (also called cytokine storm) that the novel coronavirus causes in the lungs and determine whether the drug is best used alone or in combination with remdesivir. INVESTIGATORS: Aneesh Mehta, Nadine Rouphael, Emory Vaccine Center Infectious Diseases faculty

Researchers have launched another trial with an immunomodulator called imatinib or nilotinib to limit hyperinflammatory responses characteristic of severe COVID-19 disease. INVESTIGATORS: Vincent Marconi, Nadine Rouphael, Ray Schinazi, Marshall Lyon, Daniel Kalman, Emory Infectious Diseases faculty

A research team is using low-dose radiation therapy (LD-RT) to treat COVID-19 patients to reduce the pulmonary inflammation that severely affects these patients and threatens their ability to breathe on their own. The first cohort in this Phase 1/2 trial will consist of five critically ill, hospitalized patients not currently on ventilators, and it is hoped that the LD-RT will reduce their risk of requiring mechanical ventilation. INVESTIGATORS: Mohammad Khan, Clayton Hess

Emory investigators are testing whether an anticancer drug can reduce lung inflammation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, possibly preventing the need for intubation and lowering

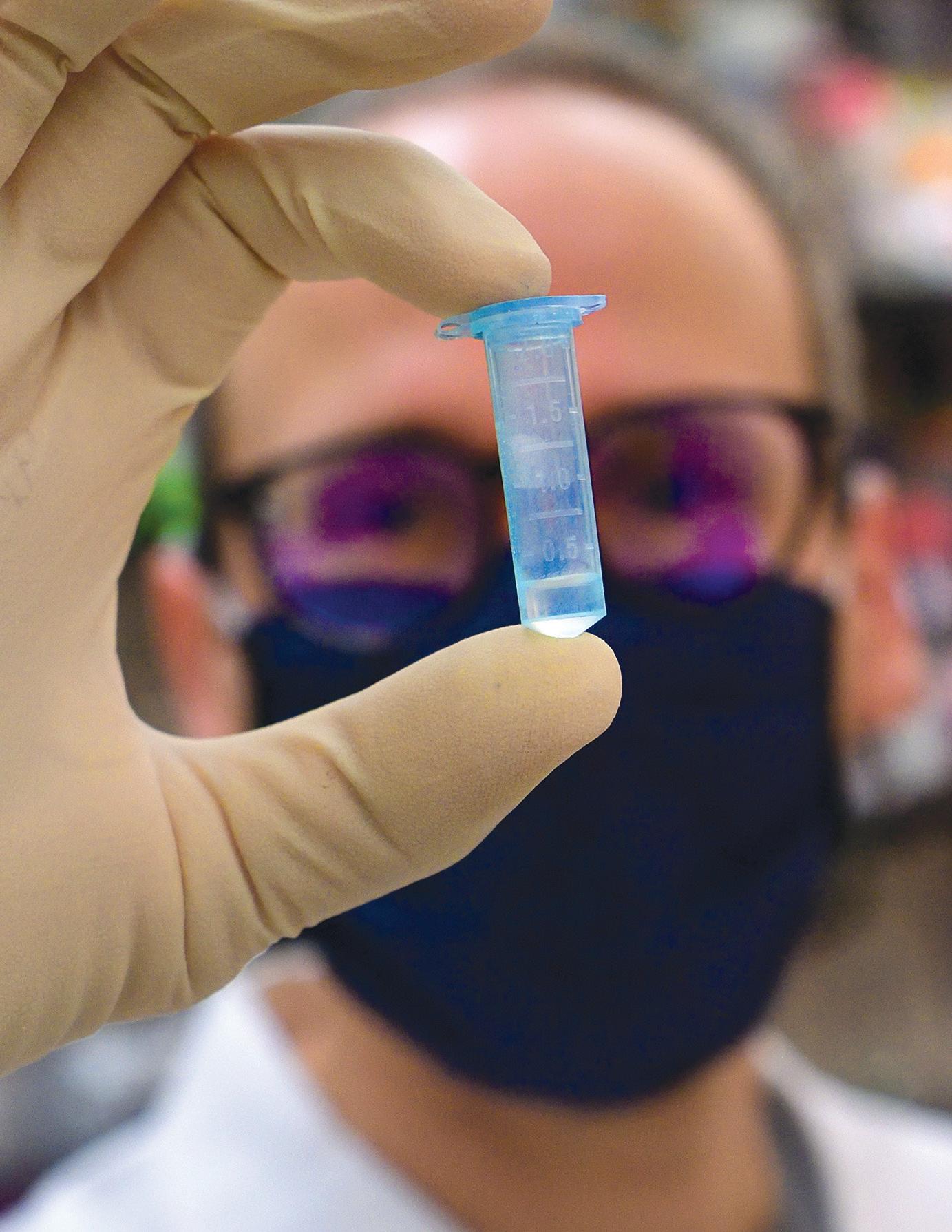

Studies will gauge whether monoclonal antibodies are effective against COVID-19.

Virus-neutralizing antibodies develop within days.

mortality. The drug is called duvelisib, and it was FDA-approved in 2018 for the treatment of a certain type of leukemia. This Phase 2 study is supported by duvelisib’s manufacturer, Verastem Oncology. The Emory team plans to recruit 40 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. INVESTIGATORS: Edmund Waller, Aneesh Mehta, Marshall Lyon

VIRUS-NEUTRALIZING ANTIBODIES Researchers at Emory have found that nearly all people hospitalized with COVID-19 develop virus-neutralizing antibodies within six days of testing positive. While most other studies on the topic have focused on the immune response after hospitalization, Emory used its biosafety level 3 laboratories to do the more time-consuming work of studying patients’ antibody response during hospitalization.

The study’s findings have implications for convalescent plasma therapy and vaccine development. Using this research, clinicians will evaluate the use of convalescent plasma with high levels of neutralizing antibodies as a treatment for the new coronavirus. The FDA has authorized emergency use of convalescent plasma therapy as an experimental treatment in clinical trials and for critically ill COVID-19 patients. INVESTIGATORS: John Roback, Sean Stowell, Colleen Kraft, Nadine Rouphael, Aneesh Mehta, Rafi Ahmed, Jens Wrammert, Mehul Suthar

Positive (sample positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies)

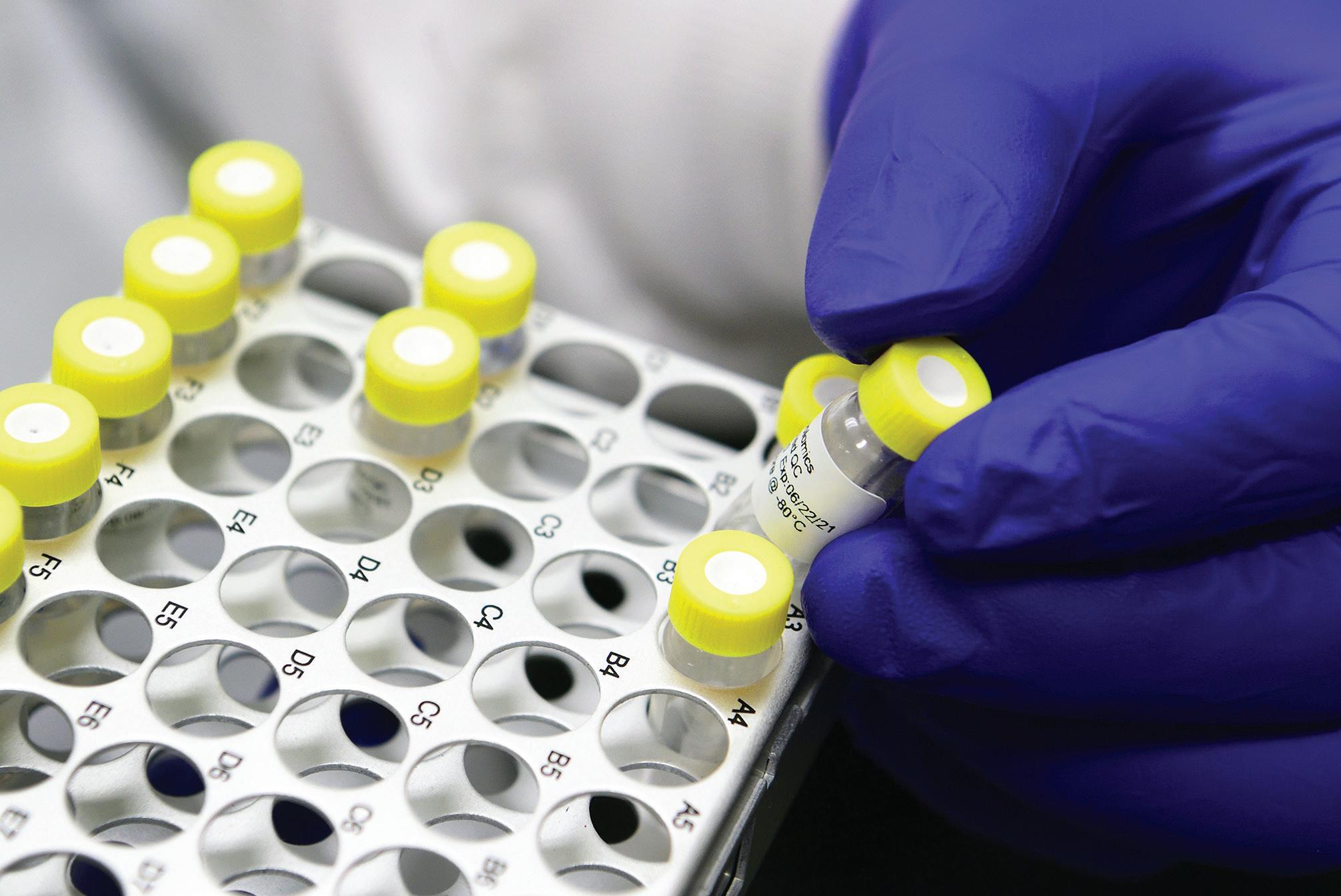

Emory is one of the sites selected by NIH to vet diagnostic COVID-19 tests.

three Atlanta institutions selected to vet the most promising diagnostic technology. Working with their counterparts Emory administered its first dose of the Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccine at the Hope at Children’s Healthcare Clinic of Emory Vaccine Center in mid-August. Hundreds of adult volunteers 18 and older of Atlanta and Georgia are enrolled at three clinics: Emory Children’s Clinic, the Hope Clinic, and Grady Health’s Institute of Technology, Ponce de Leon Center. Emory researchers will put the technologies through a competitive, rapid threeBLOOD CLOTTING phase selection process to identify the best Georgia is in the so-called stroke belt, a swath candidates for at-home and point-of-care COVID of Southern states where age-adjusted stroke -19 tests. The $31 million funding for this project mortality levels are high. So, COVID’s links to is the largest NIH grant Emory has received in a blood-clotting problems were particularly single budgetary year. INVESTIGATORS: Wilbur Lam, Greg worrisome. Emory researchers are leading Martin, and Oliver Brand a study to identify blood tests that can help Emory has developed a SARS-CoV-2 antibody determine which COVID-19 hospital patients are test to enhance disease detection. Antibody or seat the highest risk for developing blood clotting rological tests can help answer critical questions disorders that cause stroke, heart attack, or clots such as virus neutralization, disease progression in the lungs, legs, or arms. Preliminary studies in populations, exposure to the virus, and infechave showed that certain blood biomarkers can tion spread. Emory’s antibody test identifies the identify high-risk patients early and, with early exact type of antibody that prevents the COVID-19 use of blood thinning medications, prevent virus from connecting with and entering human clotting complications. Another study is look- cells, which allows physicians to better predict ing to understand why an enzyme that causes whether someone with a positive antibody clotting becomes dysregulated during the test result is likely to be protected from future course of the infection, which can be especially infection. Emory experts are also evaluating harmful to patients with pneumonia who are at devices that collect plasma samples from blood high risk for respiratory failure and require, in droplets—taken by a finger prick—which can be extreme cases, an artificial lung. INVESTIGATORS: Emory transported safely through the mail or by courier stroke, neurology, and heart and vascular researchers to Emory Medical Labs for the Emory antibody test. This innovation would combine “point-ofDIAGNOSTICS care” testing with the rigor of Emory’s antibody Millions of accurate, widely accessible COVID-19 test. To facilitate widespread antibody testing in tests in time for flu season—that’s the ambi- the state, a reliable device for at-home sample tious goal of a $1.5 billion National Institutes collection is important. INVESTIGATORS: Rafi Ahmed, John of Health (NIH) initiative. Emory is one of Roback, Mehul Suthar, Jens Wrammert

Hugs All Around

There are two kinds of days for my family during this time of staying home. The days I wake up, make the coffee, stir my 8- and 5-year-old daughters from their beds and get ready for another day of virtual school, Zoom calls with colleagues, finding something special to cook to raise everyone’s spirits, and making the best of a tough situation. These are the normal days within our abnormal times.

Then there are the days where my wife isn’t here. We are living through two weeks of those days right now. Those are the days I take care of the girls alone while waiting each day for an update from the medical front line. You see, my wife is an emergency physician at Grady Memorial Hospital, and we have decided that during and after her stints of shifts treating dozens of COVID-19 patients every day that she will stay elsewhere, alone, to keep us healthy—a double sacrifice.

Being the spouse of a health care worker in this pandemic is a mix of pride, worry, practical sacrifices, and a deep sense of powerlessness. She and her colleagues have volunteered for extra shifts, dealt with equipment shortages, and have worried about their own health while caring for others. I do my best to make sure the house runs smoothly, the kids’ hair is combed for our Facetime sessions with mom, and that we do our part to lessen her stress (clean bathrooms get us bonus points).

I’m reminded from these experiences that we never really know what our neighbors or friends are dealing with—I think about those who have watched loved ones from afar battle the virus, those who have health conditions we can’t see, and the kids, who know something is deeply wrong but don’t have the experience to put it into any context. I’m not sure I have a way to help them understand except to tell them how their mom is a hero and how we do our part to help by brushing our teeth, washing our hands, and keeping a good attitude even though story time is through the computer on those nights she is away.

The frontlines in this battle are not only the hospitals, but the grocery store lines, the UPS deliveries, the manufacturing plants of essential goods. I’ll be giving my frontline heroine a big hug in a couple of weeks when she returns home to us. I hope you’ll thank your frontline friend or family member today—and maybe their partner, too.

Emory alumnus Doug Shipman wrote about his spouse, Emory Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine Bijal Shah 06M, in mid-April for GPB’s “All Things Considered.”