SPRING/SUMMER 2022

THE

SPRING/SUMMER 2022

THE

Read more than two dozen ways Emory is making a difference on its campuses and around the world by innovating and investing in the future of our planet.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can amplify humanity’s worst flaws. Find out how Emory is working to make sure AI instead exemplifies our highest virtues.

Spanning decades of research, Emory scientists have played a critical role in developing 25 FDAapproved drugs that have helped save countless lives.

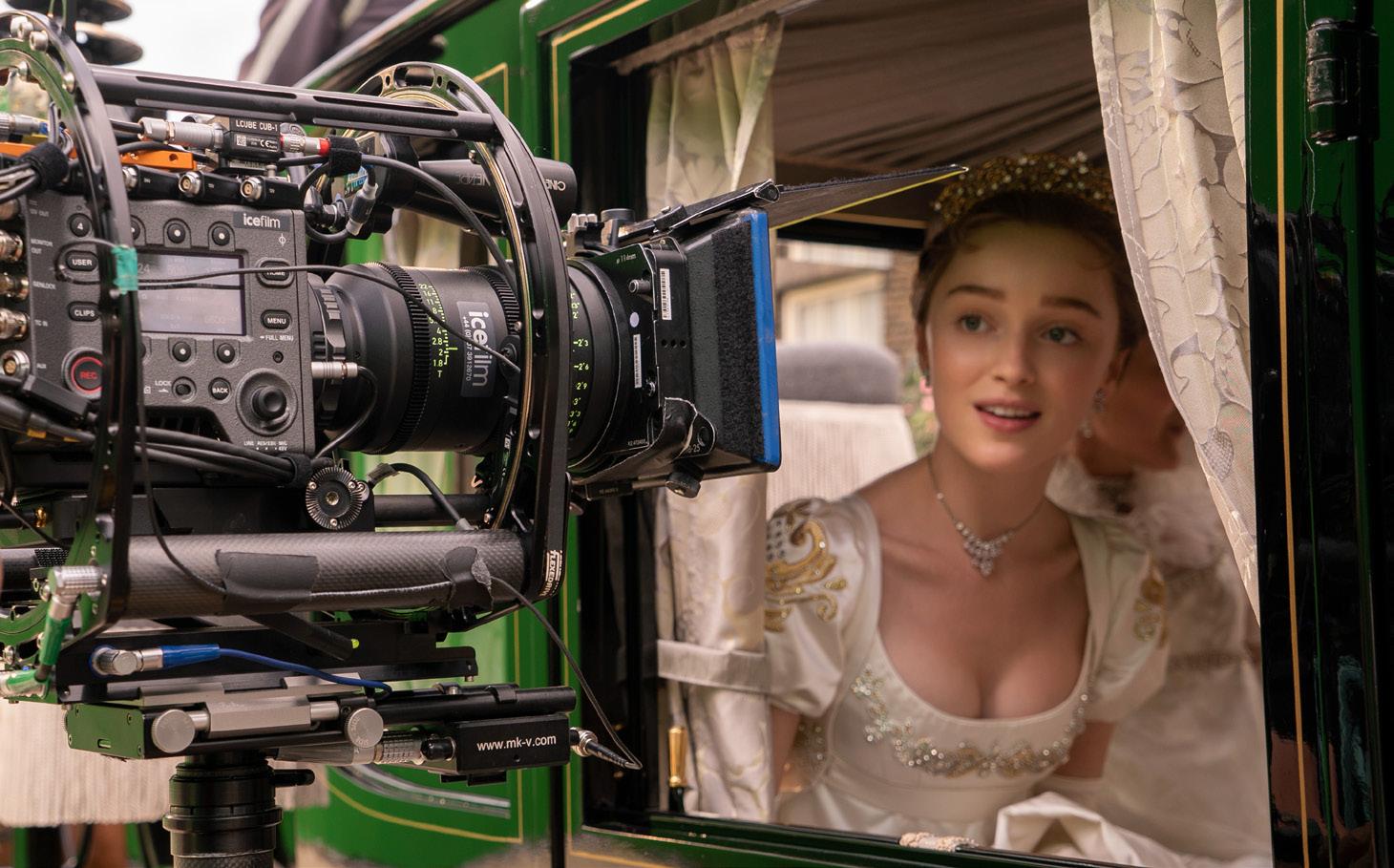

Find out how movies and TV shows are filmed on the university’s campuses, meet the alumnus behind Netflix’s Bridgerton, learn about Emory students forging their paths in filmmaking, and discover how big entertainment deals are made.

MORE 10 ON THE COVER: PAINTING BY SHARON LEE 23M USING WOMBO DREAM APP

Managing Editor

Roger Slavens

Executive Director of Content

Jennifer F. Checkner

Contributors

Jim Auchmutey, Carol Clark, Laura Douglas-Brown, April Hunt, Tony Rehagen, Kelundra Smith, Rajee Suri

Copy Editor

Jane Howell

Magazine Intern

Ellie Purinton 24C

Art Director

Elizabeth Hautau Karp

Creative Director, Publications

Peta Westmaas

Photography

Kay Hinton

Stephen Nowland

Production Manager

Stuart Turner

Interim VP, Communications and Marketing

Cameron Taylor University President

Gregory L. Fenves

EMORY MAGAZINE (ISSN 00136727) is published by Emory’s Division of Communications and Marketing. Nonprofit postage paid at 3900 Crown Rd. SE, Atlanta, Georgia, 30304; and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Advancement and Alumni Engagement Office of Data Management, 1762 Clifton Road, Suite 1400, Atlanta, Georgia 30322.

Emory Magazine is distributed free to alumni and friends of the university. Address changes may be emailed to eurec@emory. edu or sent to the Advancement and Alumni Engagement Office of Data Management, 1762 Clifton Road, Suite 1400, Atlanta, Georgia 30322. If you are an individual with a disability and wish to acquire this publication in an alternative format, please contact Managing Editor Roger Slavens (address above). No. 22-EU-EMAG-0059 ©2022, a publication of the Division of Communications and Marketing.

The comments and opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily represent those of Emory University or the staff of Emory Magazine.

the pandemic, our celebration was finally home, back to the traditional Commencement setting experienced by generations of Emory alumni.

Watching the procession of proud graduates, I saw the resilience and resolve that was required to adjust to lives upended by a pandemic. And yet, they adapted––learning both inside a classroom and on a laptop from home, discovering ways to connect with faculty and peers, and finding meaning in their experiences.

Seeing the joy that radiated from our new Emory alums, poised to launch their journeys, I reflected on everything that happened to create this day, across the past semester, the academic year, and throughout the disruptions of the past two years. And I was reminded of the determination of Emory faculty, staff, and students to keep the flame of our mission burning bright, to keep our university moving forward.

Emory University exists not only to create and share knowledge, but also to empower bold possibilities––discoveries that we can’t yet imagine, ideas that inspire progress, and breakthroughs designed to create a better world. In my time at Emory, I’ve seen that promise in so many ways:

• I saw it in the faces of dedicated public health faculty and students, who gathered earlier this year at the Rollins School of Public Health to learn about a landmark $100 million gift from the O. Wayne Rollins Foundation––the largest in the school’s history––to support faculty excellence and student flourishing.

to seeing our university provide an exceptional education that is within reach of all talented students, regardless of their backgrounds or financial resources.

That’s why, beginning this fall, Emory will eliminate need-based loans from the financial aid packages of domestic undergraduate students, replacing them with grants and scholarships. This will double the number of students eligible to receive loan-free financial aid, covering almost half of our undergraduate enrollment. The expanded Emory Advantage program will go far in reducing student debt, easing the transition from college to career for many.

Today, I’m looking across a Quad that is quiet and peaceful, the excitement of Commencement a recent memory, as the university takes a few moments to catch its breath. But it is a short break before we prepare for the next academic year, as we strive every day to achieve our promise and full potential.

For Emory graduates, the conclusion of their time on campus also marks a beginning, as each student––with heart and ambition––commences a lifetime of accomplishment, service, and impact.

Gregory L. Fenves President Emory University Curran as dean of the Rollins School of Public Health.

Curran as dean of the Rollins School of Public Health.

Emory has appointed M. Daniele Fallin as the new James W. Curran Dean of Public Health at the Rollins School of Public Health. She will join Emory July 1, 2022.

Fallin has most recently served as chair of the Department of Mental Health for the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and is the Sylvia and Harold Halpert Professor and Bloomberg Centennial Professor. She has held joint appointments in the Bloomberg School’s Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry. Fallin also has served as director of the Wendy Klag Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities and has led the center since its establishment by the Bloomberg School in 2013.

Fallin’s appointment follows an extensive international search. She succeeds James W. Curran, who joined the Rollins School of Public Health as dean and professor of epidemiology in 1995 following a twenty-five-year career at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rollins ranks No. 4 by US News & World Report among accredited schools and programs of public health and ranks No. 4 nationally for National Institutes of Health funding.

“The world is acutely aware of the importance of public health, and we have an opportunity to translate this awareness into action,” Fallin says. “I am thrilled to lead the Rollins School of Public Health at this critical time and excited about the impact we will continue to make.”

GARETH JAMES, DEAN GOIZUETA BUSINESS SCHOOL

Gareth James has been appointed dean of Emory’s Goizueta Business School. He will take up the deanship at the university on July 1, 2022. James comes to Emory from the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business, where he has served as deputy dean, E. Morgan Stanley Chair in Business Administration, and professor of data sciences and operations.

He describes himself as creative, mirthful, and optimistic. And he’s always ready to introduce others to rugby or cricket. He describes Goizueta students, faculty, and alumni as incredibly strong, truly cutting-edge, and passionate.

That’s why he’s so keen to begin his work at Goizueta, noting, “Emory and Goizueta have impressive ambitions to become even stronger institutions. I’m looking forward to working with President Gregory L. Fenves, Provost Ravi V. Bellamkonda, and our faculty, staff, and students to transform that ambition into a reality. I’m also excited to be at a school whose very name represents an important legacy for both Emory and the Atlanta region.”

James believes in building a strong leadership team, providing them with the resources and support they need, and then getting out of their way, so they are empowered to do their jobs. “People rise to the challenge when you demonstrate confidence in their abilities,” he says.

A statistician by training and a New Zealander by birth, James is an active scholar and a reknowned teacher who has won numerous awards in innovation and business education.

EVER.

Maya Caron 23B wants to be a doctor. Ben Damon 23Ox wants to impact policy. Rosseirys De La Rosa 22C wants to support her family. Every student comes to college with a dream.

At Emory University, financial aid programs help make these dreams a reality. Through Emory’s need-based aid— using scholarships, grants, and the Emory Advantage program—students can make the most of their time on campus.

This winter, Emory announced it will eliminate need-based loans as part of undergraduate students’ financial aid packages, replacing them with institutional grants and scholarships beginning this fall for the 2022–2023 academic year. This expansion of the Emory Advantage program will give more students the opportunity to graduate debt free, reflecting the university’s commitment to making an Emory education accessible to talented students regardless of their financial resources.

“For Emory to fulfill our mission of

serving humanity in all that we do, we are continuing to invest in making an Emory education affordable to talented students of all financial backgrounds,” says President Gregory L. Fenves. “By eliminating need-based loans for undergraduates, our students have the opportunity to earn their Emory degrees with less debt as they embark on their extraordinary journeys after graduation.”

For students such as Rosseirys De La Rosa, financial aid makes college possible. The senior from Lynn, Massachusetts, is majoring in anthropology and human biology with a minor in African American studies. Through a combination of the Emory University Grant (awarded to students with demonstrated need) and the Emory Advantage Loan Replacement Grant, along with federal aid, De La Rosa has been able to maximize her experience. Her sophomore year, she conducted research on the DNA of Indigenous peoples in Uruguay, inspiring her to want to pursue a PhD after graduation.

“Not having to worry about using my job to pay off loans, buy books and groceries — there is no way I could have healthily done that, get good grades and still be an active member of the Emory community without financial aid,” says De La Rosa. “I am forever grateful because not having to worry about my financials at school allowed me to do all these amazing things that have given me a well-rounded education at Emory.”

For Maya Caron, a junior from Deltona, Florida, 1915 Scholars has been a boon to her education. The program provides mentorship for first-generation college students, who often receive need-based aid, to help them get from admission to Commencement.

Caron says she had never heard of Emory before a high school counselor suggested she apply. With ambitions of being a doctor, Caron says she knew she didn’t want a lot of undergraduate debt because of the cost of medical school. Caron receives need-based scholarships and grants from Emory, as well as federal grants to help fund her education.

“Without financial aid, I would not have been able to attend Emory,” says Caron, who is a business major. “Then I’d have to take out loans for med school. That would be a big stressor.”

Being at Emory has allowed Caron a myriad of hands-on learning opportunities, most notably conducting research through the Emory College SIRE program. Under the tutelage of Miranda Moore, an assistant professor focusing on health care delivery in Emory School of Medicine, Caron researched patient perceptions of different primary care models.

She also worked as a certified medical assistant at a hospital during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and shadowed a physician’s assistant. She is currently studying for the MCAT and taking prerequisite courses for medical school. With her business education, she plans to open an internal medicine practice.

With the expansion of Emory Advantage to eliminate need-based loans as part of undergraduate students’ financial aid packages, the loans will be replaced with institutional grants and scholarships beginning this fall for the 2022–2023 academic year.

“Because Emory meets full financial need for our undergraduate students, we provide a pathway to help our students and their families make an Emory education affordable,” says John Leach, associate vice provost for enrollment and university financial aid. “Emory joins a handful of elite institutions in replacing need-based loans with grants—thus giving our undergraduate students the opportunity to graduate debt free.”

Students such as Ben Damon, a first-year student from Austin, Texas, benefit from this investment. Damon took a gap year before coming to Oxford College. He was drawn to Oxford for the strong liberal arts curriculum and close-knit community. A combination of Emory grants and scholarships, an Emory Advantage loan replacement grant, and federal aid made it possible.

“The college application process was stressful, but Emory was appealing to me because I’d heard good things about Atlanta and the academic profile fit what I was looking for,” says Damon. “I was looking for a collaborative environment and a strong foundation in liberal arts, so I didn’t have to make a decision about my major right away.”

Damon is on the philosophy, politics, and law track, and is considering law school or business school. In the

meantime, he is keeping busy as a first-year Student Government Association senator on the budget and health and wellness committees, treasurer of chess club, and events coordinator for Oxford’s ballroom dance organization.

Nearly 42 percent of Emory’s undergraduate student body receives need-based financial aid. Investing in more need-based aid reflects one of the tenets of the 2O36 campaign: student flourishing. As part of the campaign, the university is hoping to raise $750 million for student scholarships.

“Through the student flourishing initiative, we are making further investments to nurture the whole student and ensure both their professional and personal success,” says Provost Ravi V. Bellamkonda. “We realize that students’ financial well-being can impact their Emory experience, which is why we are making scholarships such a central and critical part of our 2O36 campaign. We are fulfilling our promise to make Emory more accessible for all families, regardless of their socioeconomic status.”

When students have their financial need fully met, they perform better in the classroom. They also gain greater freedom to participate in extracurricular activities, research, service-learning, and internship/externship opportunities that give them an edge upon graduation. It helps students discover their passions and figure out where they can make a difference in the world.

— Kelundra SmithAccording to the 2023 edition of US News & World Report’s “America’s Best Graduate Schools” guide, Emory’s graduate and professional schools and programs continue to rate among the best in the country. Here’s a look at the top rankings:

• The Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing master’s program ranks No. 2 in the nation. The school’s doctor of nursing practice program ranks No. 6.

• Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health ranks No. 4 in the nation.

• Goizueta Business School’s fulltime MBA program ranks No. 21, while its Evening MBA program No. 11 and its Executive MBA program No. 16.

• Emory School of Medicine ranks No. 22 nationally among research-oriented medical schools.

• Emory School of Law School ranks No. 30 in the nation.

• The Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering PhD program, a joint effort between Emory School of Medicine, Emory’s Laney Graduate School, and Georgia Tech, ranks No. 2 in the country.

Through the student flourishing initiative, we are making further investments to nurture the whole student and ensure both their professional and personal success.

—Provost Ravi V. BellamkondaEMORY GRADUATE AND PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS

Ajunior in Emory College of Arts and Sciences made her literary debut this past winter with a book heralded as both one of the “best” and “most anticipated” young adult novels of 2022. But you can be forgiven if You Truly Assumed—published by Inkyard Press, a young adult imprint of HarperCollins—wasn’t on your radar.

The Robert W. Woodruff Scholar from the Washington, D.C., area has kept her accomplishment close.

Laila Sabreen 23C didn’t bring up the book with the professor who oversaw her yearlong research into the portrayal of Black girlhood in Black women’s fiction—a question her novel addresses through the story of three Black Muslim teens who become friends after a terrorist attack heightens the Islamophobia they face.

Sabreen did discuss her writing with friends. But, after they recorded her signing her agent contract as a first-year student in the Raoul Hall lounge, most conversations centered on more traditional college chatter like weekend plans, classes, and exams.

“My writing was originally just for me,” Sabreen says. “Then I realized it could go somewhere a lot of stories don’t, with Black Muslim characters written by a Black Muslim author. I hope (the novel) makes space for more Black Muslim authors to write whatever story is authentic to them.”

Growing up, Sabreen always enjoyed reading and writing. She ran a book blog with her reviews during her first two years of high school, then shifted to writing as a way to express her feelings as she watched anti-Muslim sentiment grow following the 2016 election.

Even as author Adiba Jaigirdar helped her with the novel’s revisions and provided other support through Author Mentor Match during her senior year of high school, Sabreen expected her writing would remain private.

At Emory, she initially planned a pre-health neuroscience and behavioral biology major or a quantitative methods major focused on health care. Days before starting her first year on campus, she completed Emory’s STEM Pathways pre-orientation program for students from underrepresented groups interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. There, she cemented the close friendships that have marked her time at Emory. She told her friends she was a novelist in the same matter-of-fact way that others might describe a day as sunny, but it didn’t quite register.

“As STEM people, we didn’t really know what it meant to be a novelist other than it seemed serious to have an agent,” says junior Olivia Bautista 23C, a junior majoring in quantitative sciences with a concentration in biological anthropology. “Now I know Laila is always in the process of writing a novel, even

though she does all these other things at Emory.”

Though the pandemic ruptured Sabreen’s first year on campus, she has been active as both an executive board member with the Emory Black Student Alliance and as a tutor at the Emory Writing Center.

An introductory sociology class opened her eyes to analytical approaches to explaining how people interact with each other and the world around them. She declared a double major in English—literature, not creative writing— and sociology to explore that overlap.

“Working on the edits of my book made me more aware of what I was enjoying at Emory and gave me the confidence to follow that interest,” Sabreen says. “The writer in me is very interested in people’s motivations and what that means if I can create more realistic characters.”

When Sabreen reached out near the end of her first year to Meina Yates-Richard, an assistant professor of African American studies and English, it was not to discuss her own writing. Instead, she presented a reading list to begin the research she wanted Yates-Richard to guide. Sabreen is now submitting the resulting Scholarly Inquiry and Research Experience project to a peer-reviewed journal.

She also is expanding the project, focused on Black female authors in the twenty-

first century, to include authors from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries for her honors thesis. Her plan after that is a PhD in English literature.

“We met at least bimonthly, sometimes weekly, for an entire year, and she never mentioned [her novel]. Not one time,” Yates-Richard says. “Discovering Laila is an author makes such sense, though, because I can see her aligning herself with a specific tradition in African American literature

are overlooked in public understandings of Islam and marginalized within some Muslim communities.

“Laila’s engaging storytelling offers an important window into the multiple different ways Black Muslim girls and women negotiate their identities and experiences,” Deighton says.

To help readers, especially anyone unfamiliar with that intersectionality, students in Deighton’s class also created a readers’ guide for the novel. The guide included a glossary and chapter-by-chapter prompts, such as asking about Sabreen’s intentional use of

they are looking to read a book like Laila’s.”

It is also an exciting time to be Laila Sabreen, in both author and student form.

She had numerous book promotion events to attend to this spring, but she continued mentoring with Matriculate, helping low-income high schoolers navigate the college application process.

She also has begun digging in on her honors thesis and recently submitted her second novel. Written during the first book’s editing, the novel is an examination of grief and loss Sabreen wrote after the sudden death of a family member just before she came to Emory.

“A lot comes out in my writing. It’s my way of processing what I’m feeling and thinking,” she says.

Sabreen’s ties to the tradition of scholar-writers continued this spring, with You Truly Assumed being included in the cross-listed Muslim Women’s Storytelling course. Instructor Rose Deighton, a postdoctoral fellow in Emory’s Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, assigned the novel as the first text for the class. The unit paid particular attention to the ways Black Muslim women

slang and decision not to italicize Arabic words. Deighton will edit the guide, then give it to Little Shop of Stories, a local bookstore, to share with customers.

“As publishers recognize that more diverse stories need to be told, we’re seeing a lot more adults reading young adult novels now,” says store co-owner Diane Capriola. “It’s an exciting time to be a young adult bookseller. We have a lot more to offer readers when

Sabreen has told friends that a short story—part of an anthology due next year—was loosely inspired by her first semester on campus. She also drafted a third novel over winter break. That way she can focus on her favorite part of writing—the revision— while making time for her academic work.

“My interests change, so I want to be able to shift focus,” Sabreen says. “I want to reach as many people as I possibly can, when I’m ready.”

— April Hunt“ THE WRITER IN ME IS VERY INTERESTED IN PEOPLE’S MOTIVATIONS AND WHAT THAT MEANS IF I CAN CREATE MORE REALISTIC CHARACTERS. ”

whose depth comes from a grounding in research that fuels the imagination.”

Emory historian Deborah E. Lipstadt has been confirmed by the US Senate as special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, a position in the Department of State with the rank of ambassador.

Described by the White House as “a renowned scholar of the Holocaust and modern antisemitism,” Lipstadt is Dorot Professor of Modern Jewish History and Holocaust Studies in Emory’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies and the Department of Religion.

President Joe Biden announced Lipstadt’s nomination for the post July 30, 2021. On February 8, she testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which voted March 29 to approve her nomination. She was confirmed by the US Senate on a voice vote March 30.

“There is no person more qualified for this important role than Deborah Lipstadt,” says Emory President Gregory L. Fenves. “During a time when antisemitism is on the rise across the country and world, she is the leader our nation needs to help us overcome and transform hatred through her peerless knowledge, scholarship, and expertise.”

At her confirmation hearing, Lipstadt was introduced by Sen. Jacky Rosen of Nevada, who described her as “arguably the nation’s foremost expert on antisemitism and Holocaust denial, with over four decades of groundbreaking scholarship.”

Lipstadt noted the January 15 attack on a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, where a gunman held four people hostage. “Senators, this was no isolated incident. Increasingly, Jews have been singled out for slander, violence, and terrorism,” Lipstadt said. “Today’s rise in antisemitism is staggering. It is especially alarming that we witness such a surge less than eight decades after one out of three Jews on Earth was murdered.”

She praised the US government for recognizing “Jewhatred as a serious global challenge,” including by elevating the special envoy to the level of ambassador.

While she has taught about and studied antisemitism throughout her career, Lipstadt said that she has also “repeatedly confronted real world antisemitism” and listed three “life-changing” moments:

• In 1972, as a graduate student, she went to the Soviet Union to meet with Soviet Jews whose applications to go to Israel or the US were denied. They “spoke truth to tyranny and were profoundly liberated by doing so,” leaving Lipstadt “strengthened by them and acutely aware of democracy’s precious gift.”

• In 1996, while a professor at Emory, she was sued for libel in the UK by a Holocaust denier. While the years-long legal battle ended in a “resounding verdict” for Lipstadt and against antisemitism, she spent weeks in the courtroom “listening to a Hitler apologist spew Holocaust denial, antisemitism, and racism.”

• In 2021, Lipstadt served as an expert witness in the civil lawsuit against the organizers of the 2017 “Unite the Right” demonstration in Charlottesville, Virginia. “For those extremists, who came to Charlottesville ready to do battle, neo-Nazism, racism, and antisemitism are intimately intertwined,” she told the senators.

“As those episodes suggest, Jew-hatred can be found across the entire political spectrum,” she said.

Lipstadt will take a leave of absence from Emory to serve as special envoy. When her nomination was announced, she noted that should she be confirmed, “I will miss one thing: Being in the classroom with my Emory students.”

Valeda F. Dent has been selected as Emory University’s inaugural vice provost of libraries and museum, the Office of the Provost announced. In this newly formed position, Dent will work to unite Emory Libraries and the Michael C. Carlos Museum under a new leadership structure, working closely with the Office of the Provost and providing support in planning for the future of both areas—including advancing shared discovery and conservation of the university’s extraordinary collections while continuing to expand access, programming, and community engagement.

Dent comes to Emory from Hunter College of the City University of New York in New York City, where she serves as acting provost and vice president for academic affairs, as well as vice president for student success and learning innovation. Expected to formally take the role in July 2022, Dent has already begun to engage with Emory’s libraries and museum staff in a consultative way.

As a librarian who has consistently held leadership positions of increasing responsibility, Dent notes: “Leadership of today’s academic libraries and campus-based museums is anything but routine. These entities continue to evolve; thus, one’s ability to anticipate emerging trends and evaluate their potential is key.”

Among those movements? “The socialization of library and museum resources (open access), growing collections that support

social inclusion and justice, designing empirical models for demonstrating the value of the library and the museum, and emerging and entrepreneurial technology are all spaces where rich opportunities for dialogue and collaboration reside,” she says.

At Hunter College, Dent has served as co-chair of the Presidential Task Force for the Advancement of Racial Equity. Important to her work at Emory, Dent believes strongly in the role of the library and museum in civic outreach and has a deep understanding of libraries and museums as centers of community empowerment and civic responsibility.

Dent is an active scholar who travels, conducts and publishes

high-impact research, and presents globally. She has a robust and consistent record of scholarly achievement in the areas of chronic poverty and literacy, rural African libraries, and literacy culture development and is a Fulbright Scholar.

In her position at Emory, Dent will help shape the libraries’ and museum’s support of the student flourishing and AI.Humanity initiatives.

“Aligning teaching, learning, and research opportunities with the mission of Emory University can help build a community of caring, well-informed, and civically engaged students,” Dent says. “And the museum and libraries can all play a pivotal role.”

For the sixth consecutive year, Emory University has earned the distinction as a top producer nationally of students and alumni who receive US Fulbright Awards, according to rankings announced in February 2022. Emory had twelve recipients of the Fulbright Award teach or conduct research abroad during the 2021–2022 academic year. Emory has been a top-producing Fulbright research institution eight times in the past decade, with a total of 119 student Fulbright recipients.

emory-led study finds streptomycin used on crops negatively affects bumblebees.

AN ANTIBIOTIC SPRAYED ON ORCHARD CROPS to combat bacterial diseases slows the cognition of bumblebees and reduces their foraging efficiency, a recent laboratory study finds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B published the findings by scientists at Emory University and the University of Washington.

The research focuses on streptomycin, an antibiotic used increasingly in US agriculture during the past decade.

“No one has examined the potential impacts on pollinators of broadcast spraying of antibiotics in agriculture, despite their widespread use,” says Laura Avila, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow in Emory’s Department of Biology.

Seventy-five percent of the world’s food crops depend on pollination by at least one of more than one hundred thousand species of pollinators, including twenty thousand species of bees, as well as other insects and vertebrates like birds and bats. And yet, many of the insect pollinator species, particularly bees, face risks of extinction.

The current study was based on laboratory experiments using an upper-limit dietary exposure of streptomycin to bumblebees. It is not known whether wild bumblebees are affected by agricultural spraying of streptomycin, or whether they are exposed to the tested concentration in the field.

Funded by a US Department of Agricultural grant, the researchers will now conduct field studies where streptomycin is sprayed on fruit orchards. If a detrimental impact is found on bumblebees, the researchers hope to provide evidence to support recommendations for methods and policies that may better serve farmers.

Based on established evidence, the researchers hypothesize that the negative impact of streptomycin on bumblebees seen in the lab experiments may be due to the disruption of the insects’ microbiome.

“We know that antibiotics can deplete beneficial microbes, along with pathogens,” Avila says. “That’s true whether the consumers of the antibiotics are people, other animals, or insects.”—Carol Clark

Emory chemist Rong Ma 21G received a $150,000 Michelson Prize for her proposal to harness the mechanical processes of cells as a new approach in the long-running quest to develop cancer vaccines. Ma, who received a PhD from Emory in 2021, is a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Khalid Salaita, Emory professor of chemistry.

The Michelson Prizes: Next Generation Grants are annual awards to support young investigators who are “using disruptive concepts and inventive processes to significantly advance human immunology and vaccine and immunotherapy discovery research for major global diseases,” according to the Michelson Medical Research Foundation and the Human Vaccine Project, the organizations administering the awards.

Ma was one of three scientists selected through a rigorous global competition to receive a 2021 Michelson Prize for immunotherapy research.

“We need disruptive thinkers and doers who dare to change the trajectory of the world for the better,” says Gary Michelson, founder and co-chair of the Michelson Medical Research Foundation. “Yet promising young researchers too often lack the opportunities, resources, and freedom to explore their bold ideas. The pandemic has created additional roadblocks for many of them. With the Michelson Prizes, we aim to provide early-career investigators a vital boost for their forward-thinking approaches.”

“Rong Ma is a spectacular, highly motivated scientist,” Salaita says. “Sometimes I will tell her that a goal she sets is too lofty or difficult to pull off, but she will look back at me and say, ‘I want to do really big, difficult things.’ ”

“To find specific antigens on cancer cells for cancer vaccine development is extremely challenging, partly because of the ambiguity in predicting what antigens the body’s immune cells can recognize,” Ma says. “Many researchers are focused on using genetic sequencing techniques to find genetic mutations and predict tumor-specific antigens to achieve this goal.”

Ma’s proposal, however, is to use the mechanical forces transmitted by immune cells to antigens as a marker to identify and evaluate whether an antigen can trigger a potent immune response. If the method works in a mouse-model system, Ma explains, the long-range vision would be to isolate the immune cells that are mechanically active when recognizing cancer-specific antigens. The identified antigens and isolated immune cells could then be used to train the body to defend against cancer cells. Carol Clark

Three juniors in Emory College of Arts and Sciences have been named Goldwater Scholars for 2022, the fourth consecutive year that multiple students have won the nation’s top scholarship for undergraduates studying math, natural sciences, and engineering.

Anish “Max” Bagga 23C (mathematics and computer science), Noah Okada 23C (computer science and neurobiology), and Yena Woo 23C (chemistry) are among the 417 recipients chosen from more than 1,240 nominees from universities across the country. Emory has produced forty-five Goldwater Scholars since Congress established the program in 1986 to honor the work of the late Sen. Barry Goldwater. Each Goldwater Scholar will receive up to $7,500 per year for their studies, until they earn their undergraduate degrees.

Professor Darren Lenard Hutchinson was selected to lead the School of Law’s new Center for Civil Rights and Social Justice. The center will enhance the law school’s already rich focus on issues of civil rights, human rights, and social justice and will serve as a hub for interdisciplinary scholarship, research, teaching, evidence-based policy reform, and community outreach. The center was established in September, thanks to a transformative gift of $7 million from the Southern Company Foundation. Hutchinson is the law school’s inaugural John Lewis Chair for Civil Rights and Social Justice, which serves as a lasting tribute to the legacy of “good trouble” advocated by the late congressman.

Professor Hank Klibanoff and Gabrielle

Four Emory Healthcare hospitals have been named top Georgia and US hospitals, and one has been named a top global hospital, in Newsweek’s lists of the World’s Best Hospitals 2022. Emory hospitals took the top four spots in Georgia. Emory University Hospital was listed as the No. 1 hospital in Georgia, and it was the only Georgia hospital named in the top 250 global list, coming in at number 135 in the world. Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital was listed as the No. 2 hospital in the state. Emory Johns Creek Hospital took third place, while Emory University Hospital Midtown ranked fourth. All four hospitals placed among the top 300 hospitals in the country.

Dudley, instruction archivist in Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, were confirmed by the United States Senate to serve on the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board. Dudley and Klibanoff were nominated by President Joseph R. Biden in June 2021. The review board will examine records of unpunished, racially motivated murders of Black Americans from 1940 to 1980. Dudley is a founding member of the Atlanta Black Archives Alliance and has been working with civil rights collections for more than a decade. Klibanoff is the director of the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory and the creator and host of the Buried Truths podcast, which delves into the stories of unpunished racially motivated killings.

ILLUSTRATION BY CHARLES CHAISSON

ILLUSTRATION BY CHARLES CHAISSON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHEN NOWLAND

PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHEN NOWLAND

Artificial intelligence can amplify humanity’s worst flaws. Emory is working to make sure AI instead exemplifies our highest virtues.

Our fear of artificial intelligence long predates AI’s actual existence. People have a natural apprehension in the face of any technology designed to replace us in some capacity. And as soon as we created the computer—a box of chips and circuits that almost seemed to think on its own (hello, HAL-9000)—the collective countdown to the robot apocalypse has been steadily ticking away.

But while we’ve been bracing to resist our automaton overlords in some winner-take-all technological sci-fi battle, a funny thing happened: The smart machines quietly took over our lives without our really noticing. The invasion didn’t come from the labs of Terminators from Skynet or Agents from The Matrix; it took place in our pockets, in the grocery checkout line, on our roads, in our hospitals, and at the bank.

“We are in the middle of an AI revolution,” says Ravi V. Bellamkonda, Emory University’s provost and executive vice president for academic affairs. “We have a sense of it. But we’re not yet fully comprehending what it’s doing to us.”

Bellamkonda and his colleagues at Emory are among the first in higher education to dedicate themselves, across disciplines, to figuring out precisely the impact the rapid spread of AI is having on us—and how we can better harness its power.

For the most part, this technology comes in peace. It exists to help us and make our lives easier, whether it’s ensuring more precise diagnoses of diseases, driving us safely from place to place, monitoring the weather, entertaining us, or connecting

We are in the middle of an AI revolution.

. . . We have a sense of it. But we’re not yet fully comprehending what it’s doing to us.

— Ravi V. Bellamkonda, Emory University Provost

RAVI V. BELLAMKONDA, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs

us with each other. In fact, the real problem with AI isn’t the technology itself—it’s the human element. Because while true, autonomous artificial intelligence hasn’t been achieved (yet), the models of machine learning that have snuck into every facet of our lives are essentially algorithms created by humans, trained on datasets compiled and curated by humans, employed at the whims of humans, that produce results interpreted by humans. That means the use of AI is rife with human bias, greed, expectation, negligence, and opaqueness, and its output is subject to our reaction.

In fact, the emergence of AI presents an unprecedented test of our ethics and principles as a society. “Ethics is intrinsic to AI,” says Paul Root Wolpe, bioethicist and director of Emory’s Center for Ethics.

“If you think about the ethics of most things, the ethics are in how you use that thing. For instance, the ethics of organ transplantation is in asking ‘Should we perform the procedure?’ or ‘How should we go about it?’ Those are questions for the doctor—the person who develops the technology of organ transplantation may never have to ask that question,” Wolpe says.

“But AI makes decisions and because decisions have ethical implications, you can’t build algorithms without thinking about ethical outcomes.”

Of course, just because the scientists and engineers realize the implications of their creations doesn’t mean they are equipped to make those momentous decisions on their own, especially when some of their models will literally have life or death implications. These algorithms will do things like decide whether a spot on an Xray is a benign growth or a potentially life-threatening tumor, use facial recognition to identify potential suspects

in a crime, or use machine learning to determine who should qualify for a mortgage. Is it really better for society to have engineers working for private companies deciding what datasets most accurately represent the population? Is it even fair to place that burden on them? What is the alternative?

The answer might be the very thing we’ve already identified as AI’s key flaw—humanity. If the big-data technology is going to continue to take on more and more responsibility for making decisions in our lives—if AI is truly the cold, calculating brain of the future— then it’s up to us to provide the heart. And Bellamkonda and Wolpe are among the forward-thinking leaders who believe we can do that by incorporating the

humanities at every step of the process. One way to accomplish that is with existing ethics infrastructure. Ethics has long been a concern in medical science, for example, and there are many existing bioethics centers that are already handling AI-related questions in medicine.

At Emory, the Center for Ethics boasts a world-class bioethics program, but also includes ethicists with decades of experience tackling issues that extend far beyond medicine alone, such as business, law, and social justice—all realms that are being impacted by the emergence of machine learning.

“I’m a proponent of prophylactic ethics,” says Wolpe. “We need to

Continued on Page 19

Anant Madabhushi was ready for the next step in his career as a researcher and educator. He was already widely recognized as a pioneer in the emerging field of machine learning—specifically for medical imaging and computer-assisted diagnoses. He had authored more than 450 peer-reviewed publications and held over one hundred patents in AI, radiomics, computational pathology, and computer vision. He had even seen his name printed in major consumer publications such as Business Insider and Scientific American that spread the word about how algorithms he’s created have greatly improved the accuracy of diagnosing cancer.

But Madabhushi, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University, wanted more. He wanted to break out of the lab and share his specialized knowledge of AI with doctors and clinicians who could put it to use in health care systems and hospitals. “I felt it was critical that I translate these algorithms into the medical ecosystem,” says Madabhushi. “It was time to move and deploy this technology into the clinical workflow.”

About the time Madabhushi was feeling this pull, he was contacted by Ravi Bellamkonda, a longtime friend and colleague who had recently been named provost and executive vice president for academic affairs at Emory. Bellamkonda told Madabhushi about a new initiative he was launching, called AI.Humanity, that would transform Emory into a cross-disciplinary community that takes the study of AI out of the research setting and puts it front and center in the fields of health, social justice, philosophy, business, law, literature, the arts, and every other aspect of our lives that this technology touches—which is to say practically everything.

BY TONY REHAGENSimply put, the goal is to position Emory as a thought leader in this increasingly omnipresent field and, as the name indicates, put the humanity in machine learning and AI. “Emory wants to work to understand and influence the interface between this explosion of data and data-driven decisions and how we think of ourselves as people, our

A CLOSER LOOK AT EMORY’S COMMITMENT TO ITS AI.HUMANITY INITIATIVE.

society, our commerce, and our way of being,” says Bellamkonda. “Emory wants to make an investment and build that capacity.”

In practice, AI.Humanity is an investment in people—a hiring initiative that will add to Emory’s existing strengths by bringing in between sixty and seventy-five new faculty across multiple departments, embedding expertise in AI and machine learning throughout campus and creating a larger community for the sharing of ideas.

Madabhushi is one of the initiative’s first hires. In July, he will join the Emory School of Medicine, where he can leverage the university’s renowned resources in health sciences to employ his AI and bioengineering algorithms. At the same time, he will be able to tap the expertise of the Emory Center for Ethics, the School of Law, Goizueta Business School, the Department of Political Science, and other arts and sciences programs. Having access to both sides of campus will help him and other hires to address ethics, legality, commerce, social justice, and other issues that inevitably arise when this technology—trained on human data, employed by humans, and used on other humans—goes out into the world.

“I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about health disparities and addressing the issues of bias where we’ve discounted underrepresented and minority populations in the construction of these AI models,” says Madabhushi. “Health care costs are out of control, and one reason is because we have a number of therapies that are really expensive—and a lot of them don’t work for all populations. Sixty percent of cancer patients

are bankrupt. I’m coming at it from a technical standpoint. I’m excited to work with people who work on this from the financial, ethical, and legal perspectives.”

Ethics is going to be at the heart of this initiative centered on machine minds. The questions of “should we?” and “if so, how?” are inherent in any consideration of deploying AI and machine learning to human life. And Emory already has a globally recognized foothold in this arena through the Center for Ethics.

That ethics infrastructure will be augmented by the creation of the inaugural James W. Wagner Chair in Ethics, an endowed position named in honor of the former Emory president and with a special focus on artificial intelligence. An international search is already underway to find the right person to lead multidisciplinary reflections, conversations, and challenges involving AI as its uses expand across campus and throughout society. “We’re very excited about this initiative,” says Gari Clifford, chair of the Department of Biomedical Informatics in Emory School of Medicine. “Ethics is at the core of what we do here. It’s critical that we instill ethics and health equality into both our applied models and our teaching pedagogy.”

Provost Bellamkonda has also convened a task force of faculty drawn from across the campus. This panel will not only identify promising candidates to fill these new cross-disciplinary positions, but it will also facilitate and build awareness and a community around this initiative through educational programming and seminars for faculty and students alike. “It’s a significant investment, but it’s just a seed of a broader initiative,” says Tim Holbrook, vice provost for faculty af-

“

I’VE SPENT A LOT OF TIME THINKING ABOUT HEALTH DISPARITIES AND ADDRESSING THE ISSUES OF BIAS WHERE WE’VE DISCOUNTED UNDERREPRESENTED AND MINORITY POPULATIONS IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF THESE AI MODELS.

— ANANT MADABHUSHIAI VISIONARY Anant Madabhushi, incoming faculty member in biomedical engineering

fairs and co-convener of the task force. “Hopefully, it becomes self-propagating, and we continue to grow and bring in top-notch faculty to a more formal structure.”

Fellow task force leader Lanny S. Liebeskind, vice provost for strategic research initiatives, says he thinks the initiative will do more than just take advantage of Emory’s current strengths in health sciences, ethics, business, law, and liberal arts—by bringing in so many experts in AI and machine learning, it could also burnish the university’s credentials in other areas of study.

“Historically, we’ve had great success in, but haven’t necessarily been recognized for, things computational and computer science related,” says Liebeskind, who is also Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Chemistry. “Most everyone who gets hired will have very strong computational and data science expertise. You’re shifting Emory’s overall strengths in interesting ways.”

But Provost Bellamkonda emphasizes that AI.Humanity is not about moving away from Emory’s tradition in the humanities, nor is the initiative, in his opinion, inconsistent with the university’s liberal arts mission. AI is already incorporated into most facets of everyday life, and it is becoming a foundational area of study for higher education.

Ramnath K. Chellappa, associate dean and professor of information

systems and operations management for Goizueta Business School, says that while the development of AI methods and technologies falls squarely in the domain of hard sciences, their impact is felt throughout all areas of study. “Nowhere is it more evident than in the world of business where new models have emerged to personalize creation of content, services, and production,” Chellappa says. “Building a community around AI at Emory is great way to engage multiple perspectives and will have a significant impact on university-wide pedagogy.”

That’s why the initiative is not just about recruiting academics, faculty members, and renowned researchers to Emory. It’s also about the students, from undergrad to grad student to PhD candidate—in every college, school, major, and minor—being ready to not only enter, but also influence a world that is increasingly built around machine learning.

Through the initiative, the provost envisions not only a formal curriculum incorporating AI into multiple majors and minors, but also creating AI workshops, lectures, and library resources open to anyone on campus, for credit or not. “I would like to see AI-related topics be ubiquitous on campus,” says Provost Bellamkonda. “It’s important to prepare the leaders of tomorrow—and AI is both our today and our tomorrow.”

BUILDING A COMMUNITY AROUND AI AT EMORY IS A GREAT WAY TO ENGAGE MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES AND WILL HAVE A SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON UNIVERSITYWIDE PEDAGOGY.

— RAMNATH K.CHELLAPPA, ASSOCIATE DEAN AND PROFESSOR OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT FOR GOIZUETA BUSINESS SCHOOL

Continued from Page 15

think about the ethical implications of this AI before we put it in the field. The problem is this isn’t happening through a centralized entity, it’s happening through thousands of start-ups in dozens of industries all over the world. You have too much and too dispersed AI to centralize this thinking.”

Instead, these ethics centers could be used not only as review boards for big AI decisions, but also as training centers for people working in machine learning at research institutions, private companies, and government oversight agencies. “We’ve discussed developing an online certification program in AI ethics,” says John Banja, a professor of rehabilitation medicine and a medical ethicist at Emory. “There are already a lot of folks in the private sector who are concerned about the impacts of AI technologies and don’t want their work to be used in certain ways.”

A more grassroots—and potentially farther-reaching—way to tackle this problem might be to provide these statisticians, computer scientists, and engineers with students, teachers, and researchers across the humanities while they are still in school so they can collaborate in the design of AI moving forward.

At Emory, Provost Bellamkonda has launched a revolutionary initiative called AI.Humanity that seeks to build these partnerships by hiring between sixty and seventy-five new faculty across multiple departments, placing experts in AI and machine learning all over campus, and creating an intertwined community to advance AI-era education and the exchange of ideas.

“Our job as a liberal arts university is to think about what

Over nearly eighty years, artificial intelligence has advanced from the stuff of theory and science fiction to being stuffed into everyone’s pockets. Here are ten milestones that have ushered us to our ubiquitous AI reality.

1943

Alan Turing, godfather of computer science and artificial intelligence, conceives the Turing Test aimed at determining if a machine can exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human.

1955

Computer scientist John McCarthy coins the term artificial intelligence in advance of a conference at Dartmouth University where top scientists would debate the merits of rules-based programming versus the creation of artificial neural networks.

1981

Businesses start to buy into narrower applications of AI, with Digital Equipment Corporation deploying a so-called “expert system” that configures customer orders and saves the company millions of dollars annually.

2002

Autonomous vacuum cleaner Roomba from iRobot becomes the first commercially successful robot designed for use in the home, employing simple sensors and minimal processing power to perform a specialized task.

2011

Apple introduces Siri, a voice-controlled virtual assistant that puts ground-breaking AI into the pockets of iPhone users.

1950

Author and biochemist Isaac Asimov imagined the future of AI in his sci-fi novel I, Robot, and devised the Three Laws of Robotics designed to prevent our future sentient creations from turning on us.

1969

Shakey the Robot becomes the first mobile robot able to make decisions about its own actions by reasoning about its surroundings and building a spatial map of what it sees before moving.

1997

IBM supercomputer Deep Blue defeats world chess champion Garry Kasparov in a hyped battle between man and machine.

2005

Five autonomous vehicles complete the DARPA Grand Challenge off-road course, sparking major investment in self-driving technology by the likes of Waymo (Google), Tesla, and others.

2018

Self-driving cars finally (and legally) hit the road when Waymo launches its self-driving taxi service in Arizona.

this technology is doing to us,” says Bellamkonda. “We can’t have technologists just say: ‘I created this, I’m not responsible for it.’ This will be a profound change at Emory—an intentional decision to put AI specialists and technologists not in one place, but to embed them across business, chemistry, medicine, and other disciplines, just as you would with any resource.”

While the AI.Humanity initiative has just begun, there are already several projects at Emory that have shown the potential of bringing ethics and a wide range of disciplines to bear when developing, implementing, and responding to AI in different settings.

Let’s look at four Emory examples that might serve as models for conscientious progress as AI and machine learn-

ing become even more commonplace in our day-to-day lives. Perhaps putting the human heart in AI will not only lead to a more efficient, equitable, and effective deployment of this technology, but it might also give humanity better insight and more control when the machines really do take over.

FOR MANY PEOPLE WHO WORK IN THE HUMANITIES, the advent of the digital age—the continuous integration of computers, internet, and machine learning into their work and research— has been incidental, something they’ve

merely had to adapt to. For Emory’s Lauren Klein, it was the realization of her dream job.

Klein grew up a bookworm who was also fascinated with the Macintosh computer her mother had bought for the family. But she spent much of her career searching for a way to combine reading and computers. Then came the advent of digital humanities—the study of the use of computing and digital technologies in the humanities. Specifically, Klein keyed into the intersection of data science and American culture, with a focus on gender and race. She co-wrote a book, Data Feminism (MIT Press, 2020), a groundbreaking look at how intersectional feminism can chart a course to more equitable and ethical data science.

The book also presents examples of how to use the teachings of feminist theory to direct data science toward more equitable outcomes. “In the year 2022, it’s not news that algorithmic systems are biased,” says Klein, now an associate professor in the departments of English and Quantitative Theory and Methods (QTM). “Because they are trained data that comes from the world right now, they cannot help but reflect the biases that exist in the world now: sexism, racism, ableism. But feminism has all sorts of strategies for addressing bias that data scientists can use.”

Klein’s hire between the English department and QTM is an example of the cross-pollination designed to foster thoughtful collaboration of new technologies. “She’s bringing a humanistic critique of the AI space,” says Cliff Carrubba, department chair of QTM at Emory. “A social scientist would call that looking at the mechanism of data collection. Each area has an expertise. Humanists have depth of knowledge of

history and origins, and we can merge that expertise with other areas.”

In addition to her own research, which currently includes compiling an interactive history of data visualization from the 1700s to present, a quantitative analysis of abolitionism in the 1800s, and a dive into census numbers that failed to note “invisible labor,” or work that takes place in the home, Klein is also co-teaching a course at Emory called Introduction to Data Justice. The goal is to help students across disciplines come to grips with the concepts of bias, fairness, and discrimination in data science, and how they play out when the datasets are used to train AI.

“It’s a way of thinking historically and contextually about these models in a way that humanists are best trained to do,” says Klein. “It’s a necessary complement to the work of model development, and it’s thrilling to bring these areas together. To me, the most exciting work is interdisciplinary work.”

WHILE AI AND MACHINE LEARNING ARE RELATIVELY NEW TO MANY FIELDS, the idea of computers using data to help us make decisions has been in our hospitals for decades. As a result, once big data and neural networks came around, they were readily adopted into clinical workflow—especially in the realm of radiology.

At first, these algorithms could be relied upon to relieve and double-check the eyesight of radiologists who typically

spend eight to ten hours a day staring at images until so benumbed that they’re bound to miss something. Eventually they were used to automate things even well-rested humans aren’t very good at—like measuring whether a tumor has grown, the space between discs in the spine, or the amount of plaque built up in an artery. But eventually, the technology evolved to be able to scan an image and identify, classify, and even predict the outcome of disease. And that’s when the real problems arose.

For instance, Judy Gichoya, a multidisciplinary researcher in both informatics and interventional radiology, was part of a team that found that AI designed to read medical images like

Xrays and CT scans could incidentally also predict the patient’s self-reported race just by looking at the scan, even from corrupted or cropped images. Perhaps even more concerning: Gichoya and her team could not figure out how or why the algorithm could pinpoint the person’s race.

Regardless of why, the results of the study indicate that, if these systems are somehow able to discern a person’s racial background so easily and accurately, these deep learning models they were trained on weren’t deep enough. “We need to better understand the consequences of deploying these systems,” says Gichoya, assistant professor in the Division of Interventional Radiology and Informatics

at Emory. “The transparency is missing.”

She is now building a global network of AI researchers across disciplines (doctors, coders, scientists, etc.) who are concerned about bias in these systems and fairness in imaging. The self-described “AI Avengers” span six universities and three continents. Their goal is to build and provide diverse datasets to researchers and companies to better ensure that their systems work for everyone.

Meanwhile, her lab, the Healthcare Innovation and Translational Informatics Lab at Emory, which she co-leads with Hari Trivedi, has just released the EMory BrEast Imaging Dataset (EMBED), a racially diverse granular dataset of 3.5 million screening and diagnostic mammograms. This is one of the most diverse datasets for breast imaging ever compiled, representing 116,000 women divided equally between Black and white, in hopes of creating AI models that will better serve everyone.

“People think bias is always a bad thing,” says Gichoya. “It’s not. We just need to understand it and what it means for our patients.”

THERE HAS BEEN MUCH FOCUS ON WHAT TYPE OF DATA WE TRAIN THESE MACHINES on and how those algorithms work to produce actionable results. But then what? There’s a third part to this human-AI interface that is just as important as the first two—how humans and the larger systems we have in place react to this data.

“Causal mechanisms, the reason things happen, really matter,” says Carrubba. “At Emory, we have a community beyond machine learners from a variety of specializations—from statisticians to econometricians to formal theorists, with interests across the social sciences like law, businesses, and health—who can help us anticipate things like human response.”

One such person is Razieh Nabi, assistant professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Rollins School of Public Health. Nabi is conducting groundbreaking research in the realm of causal inference as it pertains to AI— identifying the underlying causes of an event or behavior that predictive models fail to account for. These causes can be challenged by factors like missing or censored values, error in measurement, and dependent data.

“Machine learning and prediction models are useful in many settings, but they shouldn’t be naively deployed in critical decision making,” says Nabi. “Take when clinicians need to find the best time to initiate treatment for patients with HIV. An evidence-based answer to this question must take into account the consequences of hypothetical interventions and get rid of spurious correlations between the treatment and outcome of interest, which machine learning algorithms cannot

Machine learning and prediction models are popular, but one issue that is really hot is algorithmic fairness— the idea that, despite the illusion that these algorithms are objective, they can actually perpetuate the biases that are in the data.

Razieh NabiRAZIEH NABI, assistant professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Rollins School of Public Health

do on their own. Furthermore, sometimes the full benefit of treatments is not realized, since patients often don’t fully adhere to the prescribed treatment plan, due to side effects or disinterest or forgetfulness. Causal inference provides us with the necessary machinery to properly tackle these kinds of challenges.”

Part of Nabi’s research has been motivated by the limitations of the methods proposed. For one example, there’s an emerging field of algorithmic fairness—the aforementioned idea that, despite the illusion that machine learning algorithms are objective, they can actually perpetuate the historical patterns of discrimination and biases reflected in the data, she says.

“In my opinion, AI and humans can complement each other well, but they can also reflect each other’s shortcomings,” Nabi says. “Algorithms rely on humans in every step of their development, from data collection and variable definition to how decisions and findings are placed into practice as policies. If you’re not using the training data carefully, it will be reflected poorly in the consequences.”

Nabi’s work combats these confounding variables by using statistical theory and graphical models to better illustrate the complete picture. “Graphical models tell the investigator what these mechanisms look like,” she says. “It’s a powerful tool when we want to know when and how we identify these confounding quantities.”

Her work is focused on health care, social justice, and public policy. But Nabi’s hope is that researchers will be able to better account for the human element when designing, applying, and interpreting the results of these predictive machine models across all fields.

OF COURSE, AS MACHINE LEARNING FINDS ITS WAY INTO THESE VARIOUS fields and daily interactions, there is an

overarching concern that goes hand in hand with the ethical considerations—how our use of AI impacts the law.

Kristin Johnson is the Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law at Emory’s School of Law. She is internationally known for her research focusing on digital assets and AI used in commercial transactions, and she has co-authored a forthcoming book about the ethical implications of machine learning and its place in a just society. “We’re looking at a number of ways that AI is altering how we apply and understand the law,” says Johnson. “It’s having a profound effect on our understanding of our Constitutional rights, competition law, and human rights.”

Johnson points out that, like most other professions and institutions, the justice system is experiencing a direct impact from this technology. This includes things like the use of predictive models to determine bail assessment, potential recidivism,

and eligibility for social benefits.

There are also the larger concerns of peoples’ rights when it comes to use of machine learning, particularly in regards to privacy when collecting the data on which these predictive models are trained. “We need to ensure this technology is adopted and applied in a way that is consistent with constitutional norms and protects the values those laws are intended to preserve,” she says.

But whether it’s our rights to protect our personal information or trying to negotiate a plea deal with a robot lawyer, Johnson echoes the concerns of her colleagues at Emory: Don’t forget the importance of the human element in the face of tranformational technological change.

“AI is limited in its ability to provide legal services,” she says, “because there remains a necessity for empathy and understanding that currently only humans bring to the profession.”

The Piedmont Project, the country’s LONGEST RUNNING FACULTY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM IN SUSTAINABILITY, was launched at Emory in 2001. For 21 years, Emory has developed the curriculum, led, and hosted this national program for the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE), supporting more than 600 educators from across the country—including over 250 Emory faculty members—to integrate sustainability into their curriculum.

EMORY UNIVERSITY RANKS No. 6 in the United States out of 853 schools surveyed in The Princeton Review’s 2022 Guide to Green Colleges based on 2019 data evaluated for administrative and academic excellence in sustainability.

Emory in 2021 earned a “GOLD” RATING IN THE SUSTAINABILITY TRACKING, ASSESSMENT, AND RATING SYSTEM (STARS) Report for leadership and innovation in sustainability from AASHE—the 4th time in a row it has achieved this honor.

THROUGH ITS LEADERSHIP ACROSS EMORY UNIVERSITY, Emory Healthcare, and in the Atlanta community, the Office of Sustainability Initiatives, Resilience, and Economic Inclusion (OSI) and its partners have made tremendous impacts, not only on our campus environments, but also in our classrooms, laboratories, and health care facilities. And what’s been implemented locally thrives out in the greater world wherever the university’s cutting-edge research—and its sustainability-minded alumni—have taken root.

Compiled by Roger Slavens and Ellie Purinton 24CTwo years ago, Emory signed a TRANSFORMATIVE SOLAR POWER AGREEMENT with Cherry Street Energy to install more than 15,000 solar panels on its campuses. These panels will generate approximately 10 percent of Emory’s peak energy requirements and reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions by about 4,300 metric tons.

6

A founding member of the SUSTAINABLE PURCHASING LEADERSHIP COUNCIL, Emory has helped create a shared, national platform for guiding, measuring, and recognizing leadership in sustainable purchasing.

LOFTY—BUT ATTAINABLE— SUSTAINABILITY GOALS for the university’s campuses include 45 percent carbon reduction by 2030 (from 2010 levels) and total carbon neutrality by 2050, 100 percent clean energy by 2035, 95 percent diversion of waste from landfills, and 50 percent reduction in the use of potable water, among many others.

In its most recent ranking, Business Insider placed Emory No. 20 AMONG UNIVERSITIES FOR STUDENTS WHO WANT TO CHANGE THE WORLD, with our sustainability leadership cited as a key factor.

WAYS EMORY IS MAKING A DIFFERENCE ON ITS CAMPUSES AND AROUND THE WORLD

BY INVESTING IN THE FUTURE OF OUR PLANET

Emory faculty have CREATED OR MODIFIED MORE THAN 400 COURSES IN 40 ACADEMIC DEPARTMENTS that are related to sustainability. Sixty-one percent of academic departments have sustainability course offerings.

Graduate students can work toward a MASTER’S DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT PRACTICE at Laney Graduate School and a MASTER’S DEGREE OF PUBLIC HEALTH IN ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH and CERTIFICATE IN CLIMATE AND HEALTH at the Rollins School of Public Health.

12.

Emory’s School of Medicine received the No. 1 RANKING ON THE PLANETARY HEALTH REPORT CARD by medical students and faculty covering 62 medical schools in the US, UK, Ireland, and Canada based on curriculum that incorporates climate change and operational leadership.

9.

The university has developed MINORS, CERTIFICATES, AND CONCENTRATIONS IN SUSTAINABILITY FOR BOTH UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE STUDENTS that teach students sustainability as an integrated concept. Undergrads can earn a SUSTAINABILITY MINOR IN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES OR A SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCES MINOR through Emory College’s Department of Environmental Sciences, or concentrate in environmental management through Goizueta Business School. They can also strengthen leadership skills while creating sustainable community change with the ETHICS AND SERVANT LEADERSHIP PROGRAM and the COMMUNITY BUILDING AND SOCIAL CHANGE MINOR. 10.

THE TURNER ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CLINIC and the ENVIRONMENTAL AND NATURAL RESOURCES LAW PROGRAM, directed by clinical professor of law Mindy Goldstein, train School of Law students to become sustainability leaders in environmental law.

13.

THE EMORY OXFORD ORGANIC FARM, located on the edge of Oxford Campus, was created in 2014 on eleven acres of land donated by an Emory alumnus. This interactive outdoor classroom gives students HANDS-ON EXPERIENCE IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE and provides fresh food for Emory’s campuses and the surrounding communities.

NINETY-FIVE PERCENT of Emory students report an INCREASE IN SUSTAINABILITY-RELATED KNOWLEDGE during their time learning at the university. But more important, 46 PERCENT of students say they INCREASED THEIR OWN SUSTAINABLE BEHAVIORS while at Emory.

Just months later in October 2021, the EMORY CLIMATE COALITION—comprised of three student groups— enlisted President Fenves, on behalf of the university community, to join the GLOBAL RACE TO ZERO, an initiative backed by higher ed institutions devoted to achieving ZERO CARBON EMISSIONS.

18.

Since its founding in 2006, the OSI has offered more than 170 INTERNSHIPS to Emory students who use research, data analysis, outreach, training, communications, and programmatic skills to integrate sustainability into all levels of the Emory enterprise.

Under the tutelage of associate professor of environmental sciences

Eri Saikawa, FOUR EMORY STUDENTS

Kaela Wilkinson 23C, Ryan Thorne

23G, Marlon Gant 23G, and Chiara Brust 23PH—had the incredible opportunity to share their voices on the world stage at the 2021 UN CLIMATE CHANGE CONFERENCE and gain invaluable experience as scholars and advocates for climate change solutions.

In June 2021, THE STUDENT-LED PLASTIC-FREE EMORY group worked with President Gregory L. Fenves to adopt a “BREAK FREE FROM PLASTICS PLEDGE” that commits the university to reduce its consumption of unnecessary single-use plastics. Co-founded by students Nithya Narayanaswamy 21Ox 23C and CJ O’Brien 21G, the group has built a broad coalition to collect data, engage the Emory community, and develop actionable solutions

At the same time, President Fenves also signed the SECOND NATURE CLIMATE LEADERSHIP NETWORK, joining 450 other universities and colleges that have agreed to take actionable and trackable steps toward REDUCING GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS.

This spring, OSI is launching its INAUGURAL POSTGRADUATE FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM and adding a new CLIMATE SOLUTIONS FELLOW and A SUSTAINABILITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE PROGRAMS FELLOW. Both will gain one full year of expertise and mentorship in these areas.

Emory’s RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY COLLABORATORY (RSC) is a THINK-AND-DO tank that leverages the collective expertise of corporate leaders, university faculty and staff, government, and community organizations and plugs into actionable projects that generate innovative solutions to sustainability and resilience challenges. RSC projects are first tested locally, exploring on-the-ground solutions that may be translatable and scalable to communities across the globe.

23.

21.

One RSC project led by professor Eri Saikawa involves SOIL TESTING IN WEST ATLANTA, where exposure to heavy metals and metalloids can cause serious health consequences and even death. Having found slag dumps and high levels of these contaminants in the soil, the project is working to INCREASE AWARENESS IN THE COMMUNITY while encouraging systematic testing and communityengaged remediation.

The WORKING FARMS FUND, a partnership between Emory and The Conservation Fund, has acquired farmland within 100 miles of Atlanta that helps PROTECT AND PROMOTE SMALL AND MID-SIZED FARMS surrounding the metro area while generating a resilient food supply. This land is leased to a new generation of farmers with a five- to 10-year path to ownership. In November 2021, Emory started receiving the first produce from these farms.

Last fall, Emory HOSTED LEADERS OF THE MUSCOGEE NATION and adopted an OFFICIAL LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT as early steps toward honoring the Indigenous peoples as the original inhabitants and stewards of the land on which Emory now sits. Important work still lies ahead to create a university community that is more inclusive of Native and Indigenous perspectives, learning, and scholarship, as well as to provide respectful stewardship of the land.

Join the Emory Alumni Environmental Network, which connects alumni who share an interest in preserving our environment. Led by alumni Mae Bowen 16C, Amy Hou

In 2020, Emory received a NATIONAL GRANT FROM THE EPA to establish an on-campus prototype for an ANAEROBIC DIGESTER This cutting-edge technology can turn food waste into biogas (renewable energy) and soil amendments (agricultural use).

THE WATERHUB AT EMORY is a WATER RECYCLING SYSTEM that uses eco-engineering processes to clean wastewater for future non-potable uses like heating and cooling buildings and flushing toilets. Installed in 2015, it was the first system of its kind in the US and now RECYCLES UP TO 400,000 GALLONS OF WATER DAILY.

15Ox 17C, and Taylor McNair 16B, the network provides learning experiences, networking events, and service opportunities year-round.

ITis a rare honor to meet someone whose life you have saved.

Emory drug hunters Dennis C. Liotta, Raymond F. Schinazi, and Woo-Baeg Choi, however, know the feeling. The drugs they developed for HIV—Epivir and Emtriva—have saved countless lives.

At conferences, in restaurants, those who are still here because of the work of these scientists, or love someone who is, often step forward to express their thanks. It doesn’t get old. How could it?

BYThough rightly celebrated for the magnitude of their discoveries, Schinazi and Liotta, who remain at Emory, rub elbows with a host of colleagues whose work is also groundbreaking. During the past two decades, Emory scientists and clinicians have developed medications to treat influenza, cancer, hepatitis, hemophilia, measles, heart disease, dry eye, hot flashes, and other disorders.

In that time, a brass bell outside the Emory Office of Technology Transfer (OTT) has gotten a workout. Whenever the office signs a deal to license an Emory researcher’s invention to a company wanting to develop it as a new product or drug, Todd Sherer—associate vice president for research and OTT’s executive director—rings the bell outside his office, and everyone within earshot applauds.

In 2013, Sherer sounded the bell for an obscure drug called EIDD-2801, which Emory scientist George Painter developed as a countermeasure against Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Painter later found that it worked against respiratory viruses such as influenza and, eventually, a disease

no one had heard of until two years ago: COVID-19.

EIDD-2801 evolved into molnupiravir, the first oral antiviral pill approved in the world to treat symptoms of the novel coronavirus that has killed more than five million people worldwide. The medication received Emergency Use Authorization from the US Food and Drug Administration on December 23, 2021, and its manufacturer, Merck, rushed to make the red capsules available to highrisk patients.

But none of that was foreseeable when Painter synthesized the precursor of the drug and Sherer clanged his bell. “It was but a glimmer in the eyes of us all,” Sherer says. “This is standard fare for universities, where discovery occurs years before success becomes obvious.”