A Dream Coming True in Midtown Atlanta

SUMMER 2023

Inside: FIRST FDA-APPROVED GVHD TREATMENT p. 24 SPOTLIGHTING WINSHIP’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS p. 19

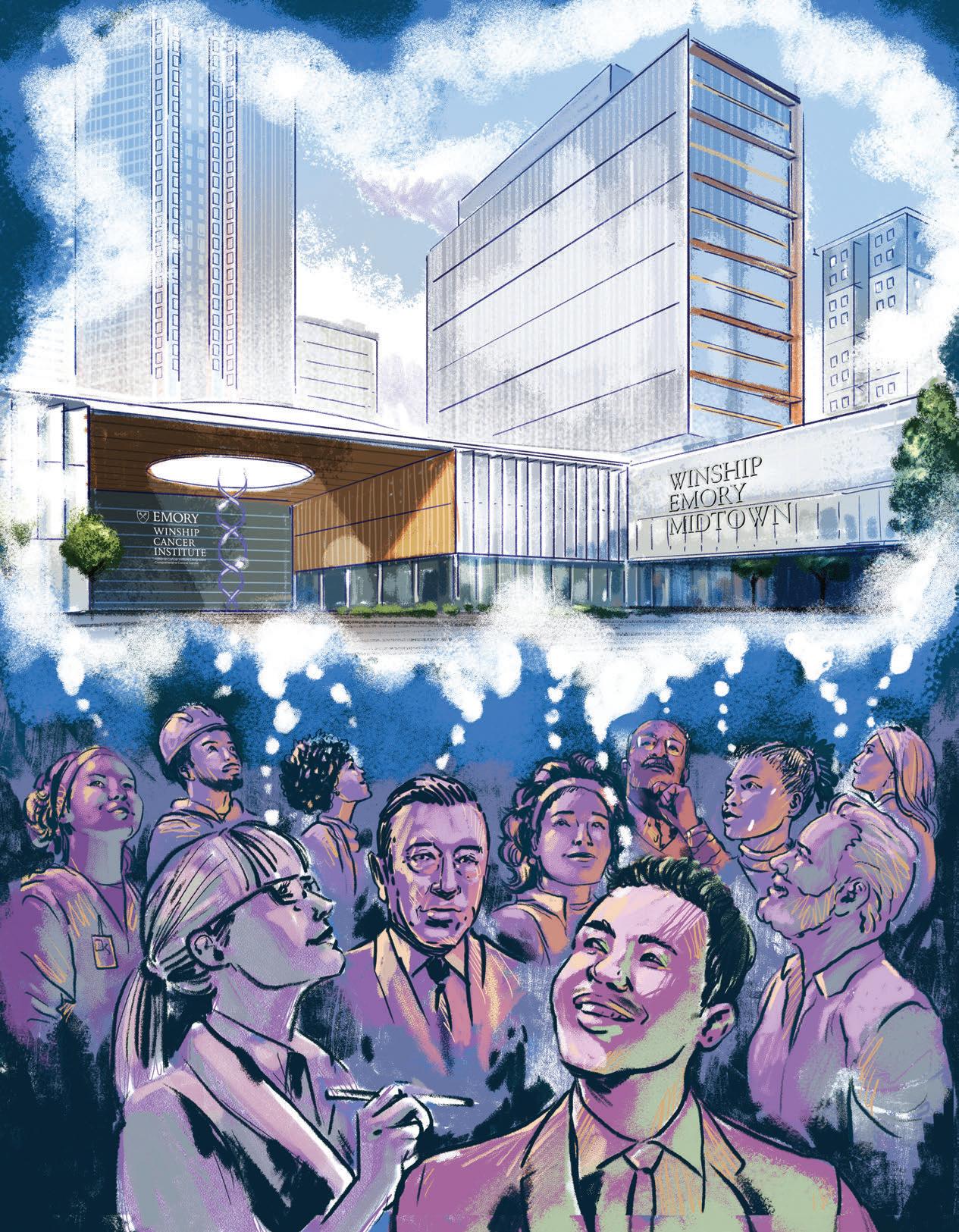

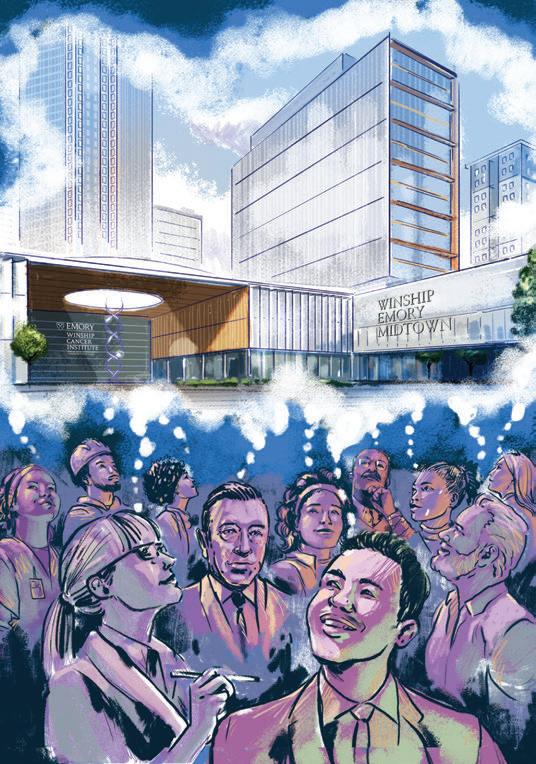

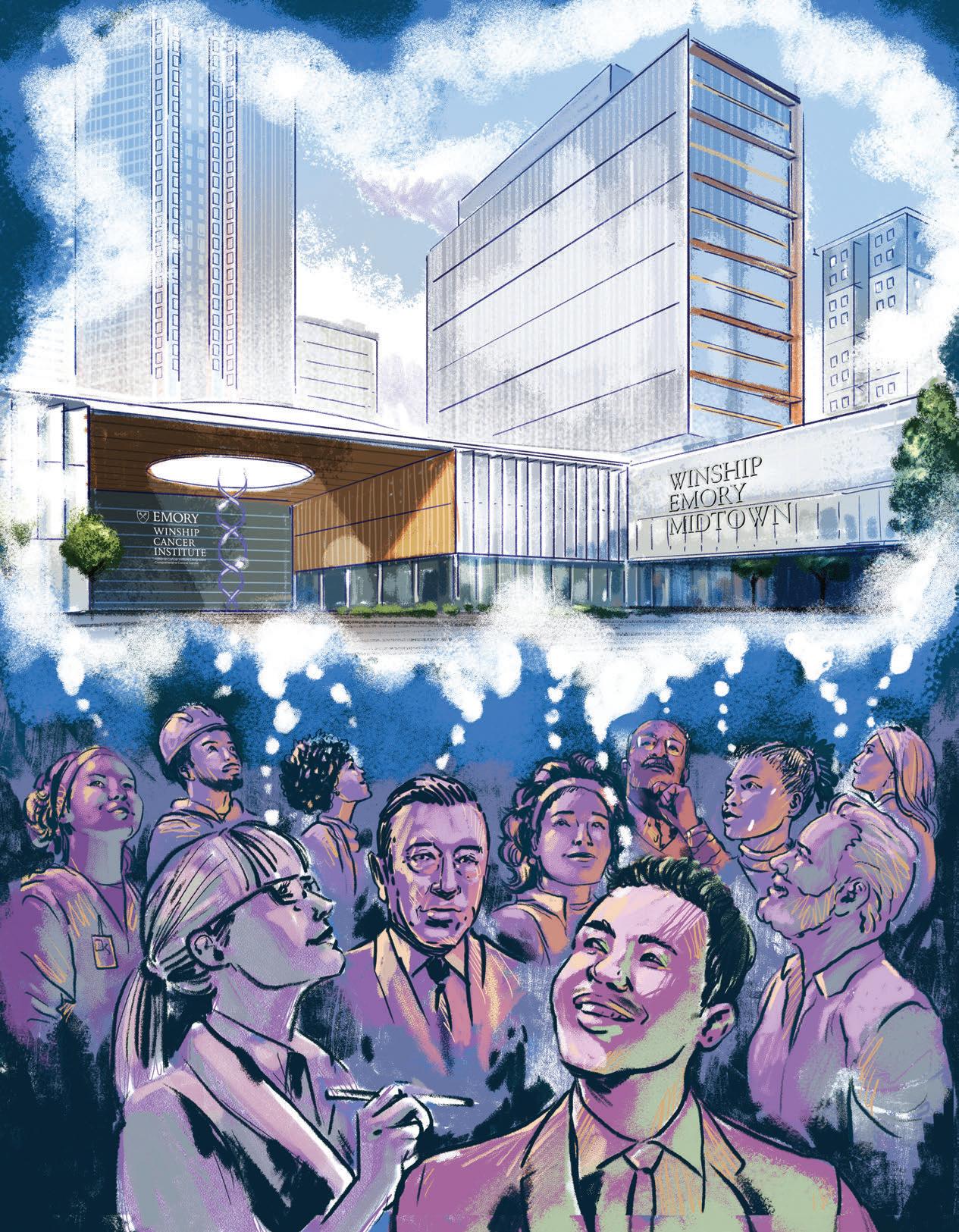

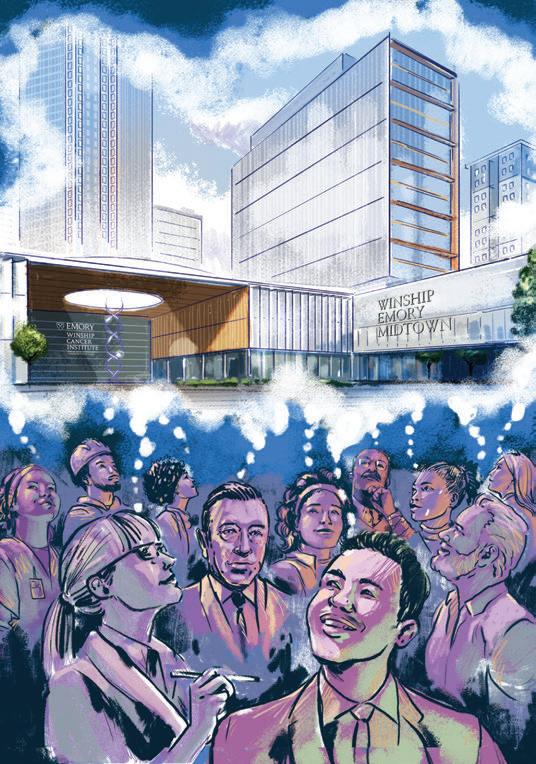

On the cover: A dream coming true

in Midtown Atlanta

Illustration by Charlie Layton

“I believe 100% there are patients I’m seeing in clinic right now who are alive because of abatacept.”

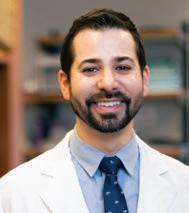

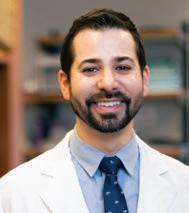

Benjamin K. Watkins, MD, director of the Global Oncology Program at the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, member of the Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Program at Winship Cancer Institute

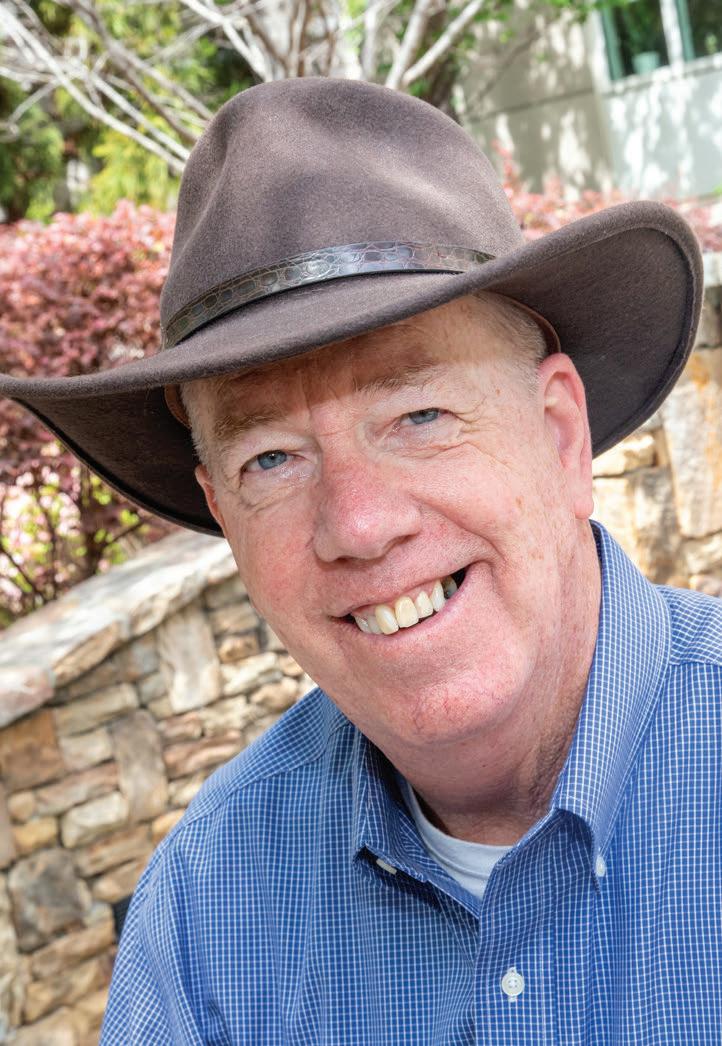

“I think that if things go as we hope with this concept, process and space, Emory will become the shining beacon on a hill for cancer care.”

6 24

Mark El-Deiry, MD, FACS, program lead

for

Winship’s Head and Neck Tumor Multidisciplinary Program

PHOTO BY JENNI GIRTMAN

From the Executive Director 2

In the News

Pioneering Perspective 3

Zachary S. Buchwald, MD, PhD

Could harnessing the body’s circadian rhythm strengthen cancer treatment?

Welcome to Winship 4

Four Scientists Who Have Changed the World of Cancer

Emory | Winship Magazine is published biannually by the communications office of Winship Cancer Institute, a part of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center of Emory University, emoryhealthsciences.org. Articles may be reprinted in full or in part if source is acknowledged. If you have story ideas or feedback, please contact john.manuel.andriote@emory.edu © Emory University

Winship Magazine | Summer 2023

Features A Dream Coming True in Midtown Atlanta 6

Mentors Pass Along Knowledge, Skills and Wisdom: Spotlight on Winship’s Education and Training Programs 19

Finding Joy: How Tapping Her Creativity Helped Kristen Chester Heal From Breast Cancer 20

Emory University is an equal opportunity/equal access/affirmative action employer fully committed to achieving a diverse workforce and complies with all federal and Georgia state laws, regulations and executive orders regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. Emory University does not discriminate on the basis of race, age, color, religion, national origin or ancestry, sex, gender, disability, veteran status, genetic information, sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression.

How Winship’s Research Led to the First FDA-Approved Treatment for Graft vs. Host Disease (GvHD) Prevention 24

Creating Legacies that Move Winship Forward 30

Inspiring Hope: Reshma Jagsi, MD, DPhil 32

Website: winshipcancer.emory.edu. To view past magazine issues, go to winshipcancer.emory.edu/magazine.

Editor: John-Manuel Andriote

Art Director: Marco Alarcón

Lead Photographer: Jack Kearse Production: Stuart Turner

22-EVPH-Winship-0015 20

ILLUSTRATION BY KEITH CHAMBERS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

3 19

PHOTO CREDIT: JENNI GIRTMAN

PHOTO BY JAVIER DE JESUS

WELCOME TO THE SUMMER 2023 ISSUE OF WINSHIP MAGAZINE. This issue comes at a very exciting time for Winship, with the inauguration of our magnificent new Winship at Emory Midtown facility in May 2023, and renewal of Winship’s status as a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in April 2023. In this issue, you will find written and visual snapshots that offer a glimpse into the ongoing work of Winship researchers, care providers and staff.

Each story and photo offers a look at the game-changing research of our scientists, the life-sustaining efforts of our clinicians and the career-shaping impact of our educational and training programs. Together they add up to a major effort here in the heart of Atlanta to advance us toward a world free of cancer.

We are extremely excited to announce the opening of Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown, our new 17-story oncology center in Midtown Atlanta. As our cover story makes clear, the new facility is like nothing ever seen or imagined. It represents the culmination of years of imagining what the patient-centered care model we

call “The Winship Way” would look like embodied in a major cancer care center. It is literally a dream come true for many of us, representing every facet of Winship’s community, who came together to share our visions of providing the absolute best cancer care anywhere.

Equally exciting is Winship’s renewed designation as a Comprehensive Cancer Center by the National Cancer Institute. We are pleased to be recognized among this elite group of centers across the country for conducting research into new treatments and cures, caring for people with cancer and preparing tomorrow’s physicians, nurses and other health care professionals to provide the best possible cancer care and work with communities across Georgia to reduce the burden of cancer. Among the other highlights of recent life here at Winship is the implementation of our new five-year strategic plan aimed at helping us fulfill Winship’s mission: To discover cures for cancer and inspire hope. The support of our donors, including generous endowments like the one from John and Cammie Rice featured in this issue, helps move Winship continually forward toward achieving our mission.

We continue to reach out and engage with partners in Atlanta and throughout Georgia, such as in the 2023 Georgia Cancer Summit held at the Georgia Tech Global Learning Center in Atlanta on January 31. “Advancing Cancer Health Equity through Innovation and Partnerships” was made possible by Winship’s collaboration with Georgia Cancer Control Consortium, Georgia CORE, the American Cancer Society, the Georgia Department of Public Health and others.

I hope you will enjoy the “snapshots” here of our ongoing work at Winship. As you read, please know that your support enables us to continue our efforts to improve the lives of those with cancer and those at risk for cancer. Thank you.

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCO

[ Winship Magazine | 2 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ] Winship | From the Executive Director

We’ve gained tremendous knowledge and momentum from discoveries that are changing the way cancer is prevented, detected and treated.

A

PHOTO CREDIT: STEPHEN NOWLAND

Could Harnessing the Body’s Circadian Rhythm Strengthen Cancer Treatment?

BY ZACHARY S. BUCHWALD, MD, PHD

FASCINATING RECENT BASIC SCIENCE RESEARCH HAS INVESTIGATED THE DIRECT IMPACT OF THE CIRCADIAN RHYTHM ON THE DEVELOPMENT AND PROGRESSION OF CANCER.

Circadian rhythm is a series of processes that occur cyclically during a 24-hour period and are controlled by biological clocks. These clocks are present in nearly every cell in our body, instructing them how to behave. White blood cells, for example, possess these internal clocks that command them to migrate to lymph nodes at a certain time and back to the blood at another time. This is a perpetual daily oscillation occurring throughout the life of the organism.

These cellular clocks can be entrained or influenced by exposure to light or other stimuli which can reset or disrupt the cellular circadian rhythm. Disruptions to this normal rhythm, from shift work or other stimuli, have been shown to increase the risk for certain diseases including obesity, diabetes and cancer.

A 2022 study published in the journal Nature showed that breast cancer is more likely to metas tasize at night. This effect appears to be influenced by the circadian nature of several steroid hormones. Another study in Nature demonstrated that the time of day a tumor is injected into a mouse dictates how rapidly that tumor grows and the overall immune response to the tumor.

These thought-provoking results suggest that cancer evolves ways to take advantage of the body’s natural circadian rhythm. They also beg the question: Can we leverage the circadian rhythm to improve cancer treatment outcomes?

This area of research, known as circadian medicine, works to harness the body’s natural rhythm to enhance treatment efficacy and/ or reduce its toxicity. Chronomodulation of cytotoxic chemotherapy–synchronizing it with the body’s circadian rhythm–was investigated by Dr. Francis Lévi of France in the late 1990s. He found that chronomodulation of three conventional chemotherapies (oxaliplatin, fluorouracil and folinic acid) improved outcomes and reduced side effects for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. This approach failed to gain significant traction as scientific trends moved in other

directions, including a focus on targeted therapy.

Cancer therapy has shifted in the intervening decades—in part, to drugs that stimulate the immune system, known generally as immunotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors—including ipilimumab (Yervoy), pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo)— have improved survival for many different types of cancer, including melanoma.

Given that white blood cells, the target of these immune checkpoint drugs, have an oscillatory circadian rhythm, my colleagues and I hypothesized that chronomodulation of immune checkpoint inhibitors may improve their efficacy. In our initial study, we focused on patients with metastatic melanoma (stage IV) who were treated at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, starting in 2012. In this retrospective analysis, we found that patients who received a larger percentage of their immunotherapy cycles earlier in the day had improved clinical outcomes, including longer survival. Similar results also have been seen in non-small cell lung cancer and metastatic kidney cancer.

These compelling results still need to be validated in a gold-standard randomized clinical trial. Funding for this next step has been challenging to secure, but progress is being made.

Currently, circadian medicine is still in its infancy. Our understanding of how anti-cancer drugs and other medications interact with the circadian rhythm is inadequate. Given the pace of research, however, we anticipate many exciting discoveries in the coming decades. w

Zachary S. Buchwald, MD, PhD, is assistant professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine and a Cancer Immunology researcher at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. His primary clinical focus is radiation and immunotherapy for cutaneous malignancies.

Zachary S. Buchwald, MD, PhD, is assistant professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine and a Cancer Immunology researcher at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. His primary clinical focus is radiation and immunotherapy for cutaneous malignancies.

(Illustration by Charlie Layton)

Photo: Jenni Girtman

[ Winship Magazine 3 | Summer 2023 ] Winship | In the News

PHOTOS BY: A. JACK KEARSE, B. JACK KEARSE, ILLUSTRATION BY KEITH CHAMBERS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY B PIONEERING PERSPECTIVE

WELCOME TO WINSHIP

Meet four of Winship’s outstanding research scientists whose day-to-day work is changing the game in important ways for people with cancer.

ANANT MADABHUSHI is a global leader in developing artificial intelligence to improve outcomes for individuals with cancer and other diseases. Madabhushi, PhD, FAIMBE, FIEEE, FNAI, is a professor in the Walter H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Biomedical Informatics (BMI) and Pathology at Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, as well as a Cancer Immunology researcher at Winship and a research health scientist at the Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Q: Why did you come to Winship?

A: Winship Cancer Institute is a top-ranked NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. As a cancer center, it is highly committed to clinical trials. While there is a significant amount of research ongoing in AI and oncology, there has been relatively little validation of these approaches in a prospective trial setting. It is clear that the culture at Winship is to help in the utility of these AI tools in a clinical decision support setting and developing prospective clinical trials that will include these tools.

I was looking for an environment where the focus was not just on cutting-edge and innovative research, which Winship has a lot of, but also a culture of deployment and translation of technologies, which was my main attraction in choosing to come to Winship.”

SUSAN C. MODESITT specializes in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies and leads Winship’s gynecologic oncology program. Modesitt, MD, FACOG, FACS, is the gynecologic team leader and chair of Winship’s Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee. She is director of the Gynecologic Oncology Division and the Leach/Hendee Professor in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine and is editorin-chief of Gynecologic Oncology Reports.

Q: Why did you come to Winship?

A: Emory has always had a special place in my heart as I was incredibly fortunate to have attended Emory College as a Woodruff scholar and compete as a varsity diver. That outstanding Emory education served as an amazing springboard into my subsequent medical career. As a bonus, at Emory I met my husband, Kacy Burnsed, who was also a Woodruff scholar and a Georgia native.

During the 30-plus years since graduation, we had always kept an eye out for potential opportunities, and I watched Winship Cancer Institute blossom into an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the last decade. It was clear that there was substantial and sustained institutional commitment to support the innovative and groundbreaking work in Winship. It was simply too good to pass up the chance to build a worldclass gynecologic oncology program at my alma mater that encompasses state-of-the-art clinical care, access to cancer trials for treatment and prevention, as well as training for the next generation of physicians to care for women with gynecologic malignancies. I am so excited about what the future holds for our patients as we continue to expand, especially with the opening of Winship at Emory Midtown in May.

[ Winship Magazine 4 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ] Winship | Welcome to Winship

B

IMAGE OF DR. MADABHUSHI AND DR. MODESITTPHOTO: JACK KEARSE

MEHMET ASIM BILEN is a board-certified medical oncologist actively involved in clinical research and patient care in the area of genitourinary cancers. Bilen, MD, directs Winship’s Genitourinary Medical Oncology Program and is a member of Winship’s Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program. He is associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Q. What insights have emerged from Winship’s Genitourinary Medical Oncology Program that have “changed the game” for one or more genitourinary cancers?

A: At the GU Med Onc group, one of our biggest goals is to bring new drugs and treatment options to our patients through clinical trials. We have several early phase and investigator-initiated trials within our group that will provide unique opportunities for our patients, such as investigating novel treatment combinations for kidney cancer, bladder cancer and prostate cancer that are leading toward FDA approval.

We are also using advanced imaging and novel technology to guide us in selecting treatment for our patients. We are including extensive correlative work to our clinical trials with our basic scientists, which allows for biomarker discovery and facilitates translational research, “bench to bedside and back to bench.” Ultimately, we are working on choosing the right treatment for the right patient to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity.

GREGORY B. LESINSKI oversees and directs the development and growth of Winship’s basic science activities across the cancer center’s four research programs. Lesinski, PhD, MPH, is Winship’s associate director for basic research and shared resources, co-director of the Translational GI Malignancy Program, and professor and vice chair for basic research in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Q: What insights have emerged from Winship’s basic research that have “changed the game” for cancer in some way?

A: The goal of the Translational GI Malignancy Program’s research is to enhance the ability of the immune system to recognize and eliminate pancreatic cancer. This disease has a high prevalence within the state of

Georgia, and its incidence is rising rapidly. Unless these tumors are caught early and surgically resected, they are typically very aggressive, and existing therapeutic approaches are, unfortunately, not effective for all patients.

At Winship, we have assembled a multidisciplinary team to study the biology of these tumors and test new therapeutic strategies that target the immune system. Using patient samples and technologies in the laboratory, our group has identified new ways by which pancreatic cancer shields itself from attack by the immune system and secretes other proteins, called cytokines, that render immunotherapy less effective in patients. In particular, we showed that one cytokine, known as interleukin-6 (IL-6), is produced in abundance by pancreatic tumors and can be blocked to enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy in pre-clinical studies.

These laboratory discoveries have led to a new first-in-human clinical trial at Winship, testing the combined blockade of IL-6 and immunotherapy targeting the PD-1 protein on immune cells for patients with pancreatic cancer. We are hopeful patients benefit from this treatment approach and that in using clinical samples from this trial, we are able to identify markers of response or resistance to therapy that can inform a new therapeutic approach in this aggressive cancer. w

[ Winship Magazine | 5 | Summer 2023 ] Winship | Welcome to Winship

-

IMAGE OF DR. BILEN

PHOTO: JENNI GIRTMAN; IMAGE OF DR. LESINSKI PHOTO: KAY HINTON

A

By John-Manuel Andriote

Illustration Charlie Layton

Designed by Marco Alarcón

Illustration Charlie Layton

Designed by Marco Alarcón

True

A Dream Coming

in Midtown Atlanta

The new full-service cancer facility is intended to give physical presence to the vision of the foundation’s namesake. As P. Russell Hardin, president of the Woodruff Foundation, explained at the November 15, 2019, groundbreaking for Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown “Mr. Woodruff fundamentally loved his hometown of Atlanta and wanted Atlantans and Georgians to have access to the best care in the world without traveling afar.”

With the funds available for a dearly held dream to become a reality, the next challenge was to define what, exactly, “the best care in the world” looks like in practice and in a physical space.

The “visioning” began by sorting out what Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University means when we describe the institute’s care model as “The Winship Way.”

for Cancer Research at Emory University School of Medicine, explains, “The Winship Way is integration of research into patient care to offer advanced therapies and technologies, teams of specialized experts collaborating to consult on treatment plans and coordinate care, and providing comprehensive care that encompasses the entire spectrum of a patient’s cancer experience, from risk reduction, early detection and diagnosis to treatment, rehabilitation and survivorship.”

Translating this care model into a physical space would require a process. “The process where people spent hours and hours, days, together talking about the care model,” says Ramalingam. First, he says they discussed what does an exceptional care model look like. Then they asked what is it going to take to deliver that care? And finally, they would consider what infrastructure would be needed to deliver that care. “Once you address that methodically,” Ramalingam says, “then you are better positioned to develop the infrastructure that incorporates the views of stakeholders on a continual basis.”

“The Winship Way is integration of research into patient care to offer advanced therapies and technologies, teams of specialized experts collaborating to consult on treatment plans and coordinate care, and providing comprehensive care that encompasses the entire spectrum of a patient’s cancer experience, from risk reduction, early detection and diagnosis to treatment, rehabilitation and survivorship.”

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCO, Winship Executive Director, Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair for Cancer Research, Emory University School of Medicine

“If we put what’s best for the patient as the guiding, central North, then the rest of it falls into place. And ultimately it will be better for care. It will be better for research. And I think it will be a better patient experience.”

[ Winship Magazine | 7 | Summer 2023 ]

The challenge from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation in providing Emory University with its largest-ever single donation of $200 million for a new oncology center was as clear as it was daunting: “Build something never seen or imagined.”

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCO, Winship’s executive director and the Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair

IMAGE OF DR. RAMALINGAMPHOTO: STEPHEN NOWLAND; IMAGE OF DR. LONIAL PHOTO: ANN WATSON

Sagar Lonial, MD, FACP, Winship’s chief medical officer; chair, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Emory University School of Medicine

Sagar Lonial, MD, FACP, Winship’s chief medical officer, professor and chair of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, was a central advisor in the visioning process. “Once we had clearly visualized what The Winship Way was about,” says Lonial, “we started to try and design the floors and the space to really support that care model, with less motion for the patient and more focus on them in the middle of the circle, if you will.”

Lonial says the first 10 or 11 iterations of what the space could look like were similar to typical hospitals, “nothing really unique.” Then groups of about 180 stakeholders from across Winship and Emory Healthcare—including patient advisors, nurses, physicians, pharmacists and other frontline users—were brought together to conceptualize the new space and were challenged to

think more about innovation. “And that’s what led us to what the current building design is,” says Lonial.

“Parts of the components of the care model that we’re talking about may exist in bits and pieces already,” says Ramalingam, “but they don’t all come together in the same facility. At Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown, with exceptional teams, we will be able to better integrate research into the care of patients with cancer. We will drive generation of new knowledge. We will elevate our care innovation to new heights, and we will meet the needs of the communities we serve through the expanded capabilities of this new center. And our vision is to bring this care model to all Winship care sites to best serve our patients and their families everywhere.”

[ Winship Magazine | 8 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN ENTRANCEPHOTO:

Drive-up entry to Winship at Emory Midtown, preparing for opening events May 1-3, 2023.

BATSON-COOK

Keeping patients at the center

Lonial says the “true North” for the project has been “what’s best for the patient.” He explains, “If we put what’s best for the patient as the guiding, central North, then the rest of it falls into place. And ultimately it will be better for care. It will be better for research. And I think it will be a better patient experience.”

For Nicole Bansavage, RN, MSN, OCN, Winship’s interim vice president of nursing and oncology specialty director for the Winship at Emory Midtown, giving patients a good experience means giving them easy access to clinical trials and bringing care to them instead of requiring them to move around to multiple places and buildings for each thing they require. “It’s very typical across the country that outpatient and inpatient care are not even in the same building, so there can be a disconnect between the two,” Bansavage says. “It’s our intention to bridge that gap between inpatient and outpatient cancer care.”

Bridging that gap is precisely why one of the most unique features of Winship at Emory Midtown is the building’s division into “care communities,” each one dedicated to a particular type of cancer. Researchers leading clinical trials related to a certain type of cancer work in the same space as doctors, nurses and other frontline staff caring for patients with that cancer. “When you typically think about cancer care,” says Lonial, “you think about the inpatient component and the outpatient components as separate. What this center tries to do is to unify them in a way that allows each care community to ultimately feel like a patient’s home-away-from-home. Meaning that they know the staff, they know the space. Everybody who is on those two floors is really

[ Winship Magazine | 9 | Summer 2023 ]

Nicole Bansavage, RN, MSN, OCN, interim vice president of nursing and oncology speciality director for Winship at Emory Midtown

Corridor of an inpatient unit

IMAGE OF NICOLE BANSAVAGEPHOTO: JACK KEARSE; IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN EXTERIORPHOTO BATSON COOK; IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN CORRIDORPHOTO: DAVE BURK © SOM

Exterior of Winship at Emory Midtown

focused on dealing with their specific kind of cancer, not just cancer in general.”

Another unique feature is bringing virtually all the services the patients need—from diagnostics and doctors’ appointments to infusions and support services—to them in one place, rather than their needing to go to multiple places. “The idea of one room for

everything really stemmed from patients describing lining up at each different place they had to go,” says Lonial, “and then having to check in, answer the same questions over and over again and go through the same drill no matter who they were talking to. This is a way to streamline that valuable patient time by creating one place where everybody comes to them, as opposed to their going to everybody else.”

“At Winship, we strive to turn science into hope for our patients. This new building facilitates this mission by connecting our innovative science with this new care model to improve patient care.”

Offering this kind of “one-stop shopping” is a major benefit for patients. David Hauenstein, co-chair of Winship’s Patient and Family Advisors and a steering committee member for the new Winship oncology center, says it’s “horribly disconcerting” for people undergoing cancer treatment to be required to navigate multiple check-ins and wait areas throughout a cancer care center. Recalling his late wife Julie’s experience during her own cancer treatment, he says, “You cannot overstate how important it is to just get them in, get them to sit down somewhere comfortable, do everything you need to do and then go home for the day.”

[ Winship Magazine | 10 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

David Hauenstein, co-chair, Winship’s Patient and Family Advisors

IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN LIVING

-

Living room in the outpatient care community

ROOM

PHOTO: BATSON-COOK; IMAGE OF DAVID HAUENSTEIN SELF-PORTRAIT; IMAGE OF DR. MARCUS -

PHOTO: KAY HINTON

Adam Marcus, PhD, Winship deputy director

Hauenstein also sees a huge benefit, for patients and Winship researchers, in the way researchers and patients are able to interact regularly in the care community spaces. “This new care model, and the building, is built around getting the researchers closer to the patients so they can be there, they can talk to patients, they can talk about new investigations that are going on. They can answer questions and enroll patients.” He adds that research is a distinctive feature of Winship versus community cancer treatment centers.

“At Winship, we strive to turn science into hope for our patients,” says Winship’s deputy director Adam Marcus, PhD, Winship 5K Research Professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “This new building facilitates this mission by connecting our innovative science with this new care model to improve patient care.”

“The care community concept is really where the joy and work for a practitioner intersects with the patient-centric experience.”

Mark El-Deiry, MD, FACS, program lead for the Head and Neck Tumor Multidisciplinary Program, associate professor, Department of Otolaryngology, Emory University School of Medicine

Mark El-Deiry, MD, FACS, Winship’s program lead for the Head and Neck Tumor Multidisciplinary Program and associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology at Emory University School of Medicine, was centrally involved in the visioning process. In part this was because he already had deep experience with putting The Winship Way into the practice and design of the Head and Neck Clinic he directs. El-Deiry advised on a wide variety of features, including how inpatient showers were designed and how to design the operating rooms and OR process.

[ Winship Magazine | 11 | Summer 2023 ]

Outpatient care suite

Two-story lounge in a care community IMAGE OF DR. EL-DEIRYPHOTO: JACK KEARSE; IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN OUTPATIENT SUITEPHOTO: BATSON-COOK

IMAGE OF CARE COMMUNITY LOUNGEPHOTO: DAVE BURK (C) SOM

El-Deiry says that everyone involved in the planning process asked, first and foremost, what could be done to make it easy for patients. He says the open floor plan, brightly lit rooms and comforting colors and wood textures are used deliberately “so when you walk in the room you’re not hit in the face with the fact that it’s an oncology treatment space.” Machines and monitors are hidden behind panels and doors. Processes and procedures are designed principally for patients’ comfort and convenience. El-Deiry says, “Those are things that really informed the vision of what the building could be.” He adds, “The care community concept is really where the joy and work for a practitioner intersects with the patient-centric experience.

Bradley C. Carthon, MD, PhD, echoes El-Deiry’s comments. Carthon is the section chief of hematology and oncology at Emory University Hospital Midtown and interim director of the Division of Medical Oncology in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “The new Winship at Emory Midtown center will allow us to focus on care of the patient in a way that hopefully best enhances their comfort and outcomes,” says Carthon. “This patient-centric approach truly allows for quick access to infusion, ancillary services and multidisciplinary collaboration. We are so excited to begin this endeavor for all of our patients.”

[ Winship Magazine | 12 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

Bradley C. Carthon, MD, PhD, section chief of hematology and oncology at Emory University Hospital Midtown and interim director of the Division of Medical Oncology in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine

Winship at Emory Midtown’s lobby

IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN LOBBY -

PHOTO: BATSON-COOK; IMAGE OF DR. CARTHONPHOTO: KAY HINTON

Looking up through the oculus of the motor court entryway

From drawing board to construction

Anthony Treu, principal and health care practice leader for Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill in New York City, the renowned architectural firm Emory chose to design Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown, recalls, “The original task was to design a care facility that had never been seen or imagined. For us, that was an opportunity that could not be squandered. We were going to find a way to help advance cancer care through design.”

“The original task was to design a care facility that had never been seen or imagined. For us, that was an opportunity that could not be squandered. We were going to find a way to help advance cancer care through design.”

Treu pointed out how unusual it was for a client to commit to such an ambitious goal. “A lot of institutions simply repeat what they or others have done in the past,” says Treu. “But Emory recognized the need to say, ‘We need to make health care better. We need to advance cancer care, and we cannot let this opportunity pass us by.’” He adds, “Many talk about doing it, but Emory has actually achieved it.”

Treu recalls the fun and engaging parts of the early design process, which brought together Emory and others from the project design team, including local design firm May Architecture and Batson-Cook Construction. “We would sit down in front of a table and have everybody collectively design the building themselves,” he says. “We even mocked up the entire building with cardboard in a warehouse, in what became ‘Cardboard City.’”

The result of the collaboration ultimately saved time and

[ Winship Magazine

13 | Summer 2023 ]

|

Anthony Treu, principal and health care practice leader, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

IMAGE OF ANTHONY TREUPHOTO: SOM; IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN EXTERIORPHOTO:

Exterior of Winship at Emory Midtown at dusk

BATSON-COOK

costs. “When we put things down on paper and shared it with the group,” says Treu, “it demonstrated how quickly we had reached consensus. This kind of design process creates an enduring product that minimizes the need for later changes.”

Lee Williams, Jr., project director for CBRE Healthcare—the world’s largest commercial real estate company, which Emory engaged to deliver Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown— describes the new facility as nothing short of “revolutionary.” He also speaks of the planning process leading up to the design and construction of the new building as rather revolutionary in its own way.

It was a “very ground-up process,” Williams says, and more organic—quite unlike what he called the common “guess-andcheck” method in which the architect will say, “Hey, do you like this one or do you like that one?” The extra engagement from the Cardboard City exercise paid dividends as construction was wrapping up. Williams says, “Typically, at that stage of the project you would expect users of the space to say, ‘I don’t like that wall’ or ‘Why is my nurses station over there?’ or something like that. We did not have to move one wall. That never happens. To see those folks walking through their space as it was beginning to come together and go, ‘This is exactly how I imagined it,’ was really cool.”

Williams, who describes himself as “a nuts-and-bolts construction guy” calls Winship at Emory Midtown “a once-in-acareer project.” He explains, “To be able to build an oncology

center for a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the middle of a major metropolitan area, for a client like Emory, and to be able to be involved from the beginning—it’s really hard to top.”

“To be able to build an oncology center for a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the middle of a major metropolitan area, for a client like Emory, and to be able to be involved from the beginning— it’s really hard to top.”

Lee Williams, Jr., project director, CBRE Healthcare

[ Winship Magazine | 14 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

IMAGE OF

Cafeteria lounge

LEE WILLIAMS, JRPHOTO: CBRE HEALTHCARE; IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN CAFETERIA LOUNGE PHOTO: BATSON-COOK

Treu puts it another way, “This is maybe a once-in-a-generation building,” he says. “I think this is going to fundamentally change the way people think about new building design for cancer care.”

Another amazing aspect of the dream coming true in Midtown Atlanta: The disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and global supply chains didn’t slow it down. “The project was on schedule and on budget,” says Williams, “something that I’m very, very proud of with everything the team has gone through.”

Innovations and innovative new uses throughout

The 17-story, 450,000-square-foot cancer care center is truly full-service and includes medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, infusions, diagnostics, imaging services, clinical trials, cardio-oncology, oncology rehabilitation, psychiatric oncology, integrative oncology, palliative and survivorship care—and many other support and wellness services. It features 80 inpatient beds in private rooms, up to 24 private care suites per outpatient floor, a fully dedicated central lab and pharmacy, a perioperative floor with six operating rooms, advanced radiology and radiation oncology equipment and an oncology immediate care center.

The center also features an attached parking garage for patients and visitors with options to self-park and valet park, a patient and family resource center, full-service cafeteria, Starbucks café, retail pharmacy, financial navigation offices and a boutique for patients—among other amenities.

Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown employs technologies and designed processes and spaces to improve workflow efficiencies and wayfinding. It uses real-time location system technology to help minimize patient wait time, and uses a wayfinding system that is connected to an app to help patients easily navigate the building.

One of the unique innovations aimed at saving nurses and other care providers time is actually an old invention put to efficient use in Winship at Emory Midtown. Ryan Haumschild, PharmD, MS, MBA, director of pharmacy services for Winship and Emory Healthcare, says his part of the visioning process was to conceive of a state-of-the-art pharmacy for the new cancer care center. The pharmacy is able to supply needed cancer medications—including radio-pharmaceuticals, investigational

[ Winship Magazine | 15 | Summer 2023 ]

Ryan Haumschild, PharmD, MS, MBA, director of pharmacy services for Winship and Emory Healthcare

IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN RADIATION THERAPY ROOMPHOTO: DAVE BURK © SOM; IMAGE OF RYAN HAUMSCHILDPHOTO: JACK

Radiation therapy room

KEARSE

agents and drugs that require unique sterile manipulation and compounding.

One of the challenges for the new pharmacy was how to transfer medications, which are sometimes short-stability and often high-cost drugs that require careful handling, to all 17 of the building’s floors. “You can’t use a pneumatic tube system that typically other pharmacies would utilize,” says Haumschild. “You have to utilize functionality that gently lifts medications up without compromising the integrity of the product, almost like its own elevator.”

Enter the dumbwaiter.

First used in the 1800s to transfer food or laundry from one floor of a house to another, the small freight elevators are used to move pharmaceuticals between floors of the facility. Each floor has pharmacy technicians in medication rooms where the dumbwaiter stops. “The technicians pull the drug off and then hand-deliver it to the nurse or the patient,” Haumschild explains. “That way the drug gets delivered to each floor without the nurse having to go down to a centralized pharmacy, letting them spend more time with their patients.”

facilities aren’t that meaningful if you don’t have the right people taking care of the patients. A facility, a physical structure, helps support what we want to do—but we can’t do it without great people.” She adds that it’s not only about what the building looks like, but “how we function together in the building to bring that vision forward.”

Marlena Murphy, a breast cancer survivor and advisor in the planning process, says the dumbwaiter is just one of the new facility’s time-savers. “One of the things that takes the longest is waiting on medication to be prepared,” says Murphy. She echoes Haumschild’s comments about the dumbwaiters, pointing out that they are convenient for the nurses and save time for patients. She says that another time-saving “comfort and convenience” is the attached parking garage. Murphy says, “The last thing a patient experiencing a cancer diagnosis wants to deal with is finding a parking space.”

“In the end, the best facilities aren’t that meaningful if you don’t have the right people taking care of the patients. A facility, a physical structure, helps support what we want to do—but we can’t do it without great people.”

The dumbwaiter is only one technical feature of the building aimed at making the most of everyone’s time. Which is precisely why Stacy L. Palmer, MBA, Winship’s vice president of cancer clinical administration and strategy, describes Winship at Emory Midtown as a “facilitator.” She explains, “In the end, the best

There are other technological features of the new facility to make treatment more manageable for patients. Karen D. Godette, MD, medical director of radiation oncology at Winship at Emory Midtown and associate professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, points to the care center’s new high-dose rate (HDR) operative suite—which allows targeted radiation in a tube or catheter to be delivered internally to the cancer, while sparing side effects to surrounding organs such as the bladder, rectum and bowel. “Once treatment is delivered,” says Godette, “no radiation remains in the body.” She adds that another new machine, the Halcyon linear accelerator, “allows us to treat more patients.” Godette explains that the Halcyon is excellent for head and neck malignancies and prostate cancer. “Treatment is delivered faster,” she says, “with more efficient workflow and high-quality image guidance.”

[ Winship Magazine | 16 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

Marlena Murphy, breast cancer survivor, was a patient advisor for the Winship at Emory Midtown project

IMAGE OF STACY PALMER PHOTO: KAY HINTON; IMAGE OF

Stacy L. Palmer, MBA, Winship vice president of cancer clinical administration and strategy

MARLENA MURPHY SELF-PORTRAIT

Helping a dream come true

Of course buildings and equipment need upkeep, employees need to be paid, and there is always the challenge of making sure the dream continues to come true for future patients. “We do require ongoing philanthropy,” says Palmer. “It’s not just for the building, but for what happens in the building and how the building can facilitate that and integrate our clinical and research and teaching missions.” She adds that philanthropy also “helps us figure out how we educate the community, how we educate underserved populations and how we participate as part of our community in reducing disparities.”

Emory University’s Advancement and Alumni Engagement team says that people are inspired by the care model and the cause it serves; they’re interested in a purpose. In the case of Winship at Emory Midtown, donors who have supported it say that they’re supporting an idea and movement in care. That was certainly the case with the generous gift from the Woodruff Foundation that set the dream in motion. Philanthropy allowed Winship to imagine big.

Sheryl Bluestein, vice president of operations for Winship Cancer Institute and Emory University Hospital Midtown, was involved from the very beginning of the planning efforts. “It was a dream back in 2010,” she says, “when we developed a business plan for a comprehensive center for cancer care on the Emory University Hospital Midtown campus. What was missing was the funding to make it a reality.” When Bluestein got a call telling her about the Woodruff Foundation gift, she says, “It was just that feeling of ‘Oh, my gosh, we can do this now. It’s no longer just a dream.’” Looking ahead as the building neared completion and readied for its May 2023 opening, Bluestein said, “Now that we’re talking about ribbon

“We fully anticipate people from beyond Atlanta, beyond Georgia, will come to take advantage of the excellent science that’s happening here and the caliber of physicians here.”

cuttings and moving into the building, it’s been more than 12 years in the making. But it was the Woodruff Foundation gift that allowed us to really make it happen.”

Bluestein expects to see even more people with cancer traveling to Atlanta for Winship’s quality care. “I think we’ll see that even more, given that the center is full-service with inpatient care and outpatient cancer care available in one single facility and designed with our patients at the center of specialized care teams. We fully anticipate people from beyond Atlanta, beyond Georgia, will come to take advantage of the excellent science that’s happening here and the caliber of physicians here.”

Ramalingam says of Winship at Emory Midtown, “I think it will be a new landmark for cancer care.” Becoming a partner in supporting that landmark for cancer care offers a chance for those looking to invest in helping to change cancer as we know it. “By looking at this facility, and the care that occurs there, people can give shape to their own vision of what exceptional care looks like— and partner with us in bringing to life that exceptional cancer care, and be part of this team.”

El-Deiry puts it this way. “I think that if things go as I hope with this concept, process and space, Emory will become the shining beacon on a hill for cancer care and will be well-positioned to have representatives from other academic centers come visit us and learn from us.” He adds, “This is a really unique opportunity for Emory as an institution to lead on the national stage. It is an exciting time to be here.” w

[ Winship Magazine | 17 | Summer 2023 ]

B

IMAGE OF SHERYL BLUESTEIN SELF-PORTRAIT; IMAGE OF INSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN ENTRYWAYPHOTO:

COOK

Sheryl Bluestein, vice president of operations, Winship Cancer Institute and Emory University Hospital Midtown

BATSON

Karen D. Godette, MD, medical director of radiation oncology at Winship at Emory Midtown and associate professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine

[ Winship Magazine | 18 winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

IMAGE OF WINSHIP AT EMORY MIDTOWN ENTRANCE PHOTO: BATSON-COOK

Exterior of Winship at Emory Midtown

Mentors pass along knowledge, skills and wisdom: Spotlight on Winship’s education and training programs

by JOHN-MANUEL ANDRIOTE

Jasmine Miller-Kleinhenz has worked with several mentors in her 12 years at Emory, beginning as one of the university’s first cohort of cancer biology students. She then participated in the R25-supported program at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University called Citizen Science: Health and Diversity, aimed at engaging citizens and middle school-aged students in science in a meaningful way so they could imagine themselves becoming scientists. Most recently, she became a postdoctoral fellow with a five-year K99 R0-0 grant.

“I’ve been really lucky to have people help guide me in how I select my mentors,” says Miller-Kleinhenz, PhD, NIH/NCI K99 Postdoctoral Fellow at Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, “which is part of it, making sure you have someone who is going to not just align with your aspirations, but align with your central framework of who you are. I’ve been lucky to find mentors who value what I value and are also really good scientists.”

The word “mentor” comes up frequently in conversations with the leaders of Winship’s various education and training programs aimed at building the knowledge and skills of new cancer researchers, physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals, college students and even middle school and high school students. Mentoring relationships are as central to the field of medicine as are apprenticeships to other crafts requiring highly refined skills and cultivated expertise.

prevention, care and education through the development of a training pipeline that provides a spectrum of learners with opportunities to participate in cancer research.

Mentorship is built in at every level of Winship’s education and training, says CRTEC’s Director Lawrence Boise, PhD, who is also Winship’s associate director for education and training and holds the R. Randall Rollins Chair in Oncology in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “There’s really no way to directly pay back the person who mentored you, so it’s very much a pay-it-forward environment,” says Boise.

U.S. News & World Report ranks Emory University among the Top 30 Best Global Universities for Oncology. “These are the world’s top universities for oncology, based on their research performance in the field,” says the magazine.

Paying it forward means contributing toward the continuation of the high-caliber research, treatment and education that comprise Winship’s tripartite mission. “Education really represents the intersection of everything that we do here,” says Adam Marcus, PhD, Winship’s deputy director and Winship 5K Research Professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. He explains that the CRTEC’s role is “to create a leadership pipeline that ensures mentorship and knowledge transfer.”

Marcus points out that Winship’s education and training efforts aren’t focused only on in-house education. “There’s also education to our middle schools,” he says, “with the idea of building a next generation of scientists and heath care providers. We’re always thinking about this pipeline to the future.”

Reaching more than 600 learners every year, Winship’s education and training opportunities are facilitated through the Cancer Research Training and Education Coordination Core (CRTEC). Winship CRTEC activities include graduate programs, K-12 programs, educational seminars, fellowship and mentorship programs. CRTEC promotes Winship’s goal to transform cancer research,

Training new physician-scientists

The Emory Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Program is dedicated to training the next generation of hematologists and oncologists who are skilled in providing compassionate

CONTINUED PAGE 26

[ Winship Magazine | 19 | Summer 2023 ]

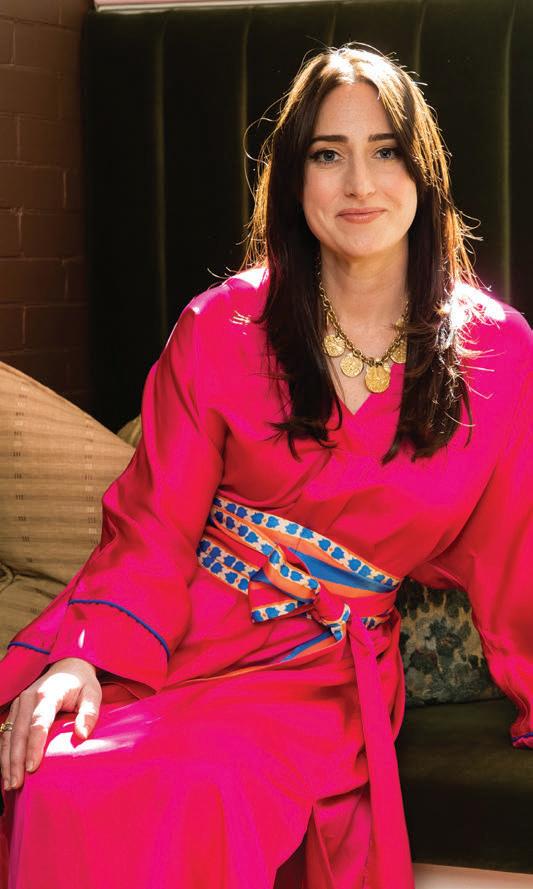

FINDING JOY: HOW TAPPING INTO HER CREATIVITY HELPED

KRISTEN CHESTER HEAL FROM BREAST CANCER

by PAM AUCHMUTEY

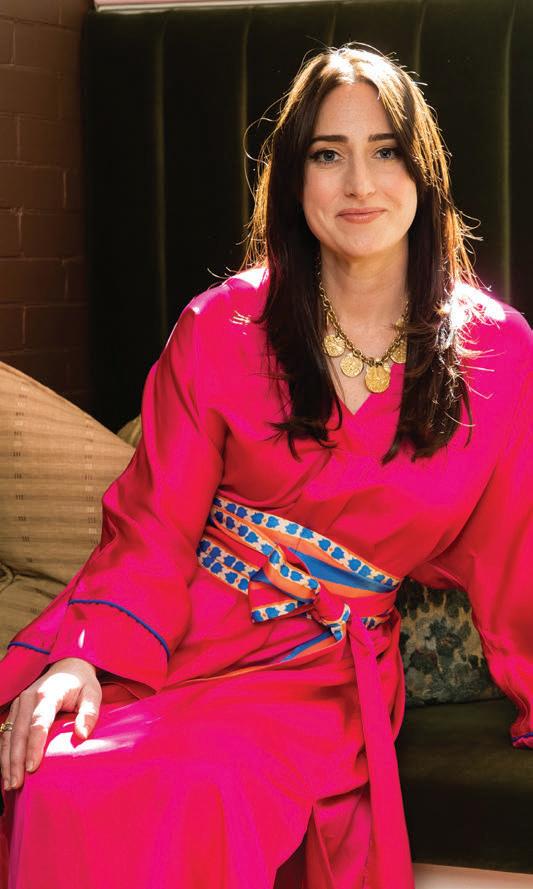

PHOTOS BY JENNI GIRTMAN

[ Winship Magazine | 20 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

Kristen Chester knows how to live colorfully and boldly. Other women can too, simply by becoming a Caftanista.

The exotic-sounding term evokes the lively spirit behind Casa Danu (pronounced DON-oo), the line of caftan clothing Chester created after being treated for breast cancer at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

Although Chester is by nature energetic and upbeat, she needed a huge pick-me-up following chemotherapy, a bilateral mastectomy and breast reconstructive surgery after she was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer while six months pregnant in January 2020. Her son Rowan was born safely in April.

Later that year, Chester was at home recovering from surgery when she caught a glimpse of herself in the mirror. “I didn’t recognize that person,” she says. “I was bloated, exhausted and had post-partum hair loss. I wore big shirts, big pants and stayed in bed for the most part.”

To complicate matters, Chester and her husband, son and parents, who had come from Los Angeles to help, were housebound because of COVID-19. She needed something to lift her spirits.

“I couldn’t change what happened to me physically,” she says. “I wanted something colorful and bright to wear that made me feel alive, luxurious and comfortable because I was recovering from surgery.”

The colorful flowing caftans of the 1960s and 1970s came to mind. “I joked about the idea with my sister, my parents and my friends,” she says. “I wished I was living the caftan life and having margaritas by the pool.”

[ Winship Magazine | 21 | Summer 2023 ]

PHOTO BY JACK KEARSE

Mahvish Junaldi was 39 years old when she was diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma (stage 3) of the left breast.

Courtney Conroy was diagnosed at 37 years old with hormone-positive breast cancer (stage 2).

“I couldn’t change what happened to me physically,” she says. “I wanted something colorful and bright to wear that made me feel alive, luxurious and comfortable because I was recovering from surgery.”

Kristen Chester

From searching to sketching

She searched online for something comfortable and stylish to wear. The vintage caftans offered for sale needed mending, while the new styles were expensive or poorly and unethically made. She began roughing out some ideas and, on a whim, took an online course in fashion sketching—a talent far afield from her career in leadership development consulting.

In spring 2021, Chester spent a week in the hospital recovering from more breast implant surgery. Tired of watching TV and reading books, she turned to her laptop to research how to start a clothing line and found Factory45, a business incubator for fashion entrepreneurs.

Chester applied and was accepted into the next class. Her online lessons covered all the basics —fabric sourcing, dyeing and printing, finding production partners, marketing and fashion photography. She decided to source her fashion line in Los Angeles, where she grew up and where her first photo session took place in her parents’ backyard.

Choosing a name for her Casa Danu fashion line was a necessary and joyful exercise. “Casa” (house) embodies Chester’s love of Italy and part of her family lineage. “Danu” (the name of a Celtic goddess) echoes her English, Irish and Scottish ancestry.

“I wanted a name that reflected a divine feminine power,” says Chester. “The goddess Danu represents strength, protection and

creation. She was the one who kept calling to me — Danu, Danu, Danu!”

The new entrepreneur launched her first collection, La Dolce Vita, in June 2022. Her sold-out collection included a caftan, blouse and pants made of a silky, eco-friendly fabric in a bold print and bright solid colors. Her next collection launched this June.

A healing journey

“Casa Danu has been such a big part of my healing journey,” says Chester. “Before I had breast cancer and my son was born, I was a workaholic. I did very well in my job, but I was depressed and had a lot of anxiety. Having a son and tapping into my creative side has really helped me heal and see a lot of life and beauty around me that I didn’t see before.”

She has a strong support system to guide her. When Chester learned she had breast cancer, she was alone on a business trip in Mexico, just as normal life was shutting down because of COVID-19. Her husband, Tim, and her parents scrambled to get her on a flight back to Atlanta to begin her cancer treatment with breast oncologist Jane Lowe Meisel, MD, a physician with Winship’s Glenn Family Breast Center, Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics researcher at Winship and associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Chester had 10 weekly rounds of chemotherapy. About halfway through, she took a two-week break to induce her son five weeks

[ Winship Magazine | 22 winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

Kristen Chester was 34 years old and pregnant when she was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer.

early. Rowan was born healthy and stayed in the NICU just two days before going home. Happy and relieved, Chester resumed chemotherapy, followed by her surgeries.

Cases like Chester’s are rare. Breast cancer affects about one in 3,000 pregnant women in their thirties, according to the National Cancer Institute. Meisel has treated five or six pregnant women during her eight years of practice at Winship. Research data show that treating these women with chemotherapy drugs is safe beginning with the second trimester of pregnancy, after a baby’s organs have formed.

Family support is especially important for these women. “Patients know that when they embark on cancer treatment during pregnancy, it’s going to be a big deal,” says Meisel. “Kristen had an incredible spouse, a wonderful mother and a network of people ready to lift her up.”

Chester had a known family history of breast cancer. Her mother, aunt and sister carry the ATM breast cancer gene. Her mother is a breast cancer survivor, and her grandmother and great-grandmother died of the disease.

Given the odds, Chester did everything she was supposed to do. Through genetic testing, she learned she did not have the ATM gene or the BRCA mutation associated with triple negative breast cancer. And she had her first mammogram in her early thirties. In light of her family history, how did Chester come to have triple negative breast cancer?

“When there’s a strong family history of breast cancer, including different types, you start to suspect there may be something in

that family that we just don’t know enough about to test for and identify yet,” says Meisel. “Though other family members potentially could be at higher risk, you can’t always quantify it with a genetic diagnosis. The best approach is to screen these women closely and think about how to reduce their risk.”

Meisel says Chester’s positive attitude during her breast cancer treatment was a major factor in her recovery. “Quite often,” she explains, “people find meaning in their cancer experience, and that’s what Kristen has done. She found something she needed and that other cancer survivors could benefit from. She developed a talent she didn’t know she had to create Casa Danu.” She adds, “What Kristen has done is just magnificent.” w

[ Winship Magazine | 23 Summer 2023 ]

Deyanna Respress was 42 years old when she was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer.

“Kristen had an incredible spouse, a wonderful mother and a network of people ready to lift her up.”

Jane Lowe Meisel, MD

HOW WINSHIP’S RESEARCH LED TO THE FIRST FDA-APPROVED TREATMENT FOR GRAFT VS. HOST DISEASE (GVHD) PREVENTION

by KIRA GOLDENBERG

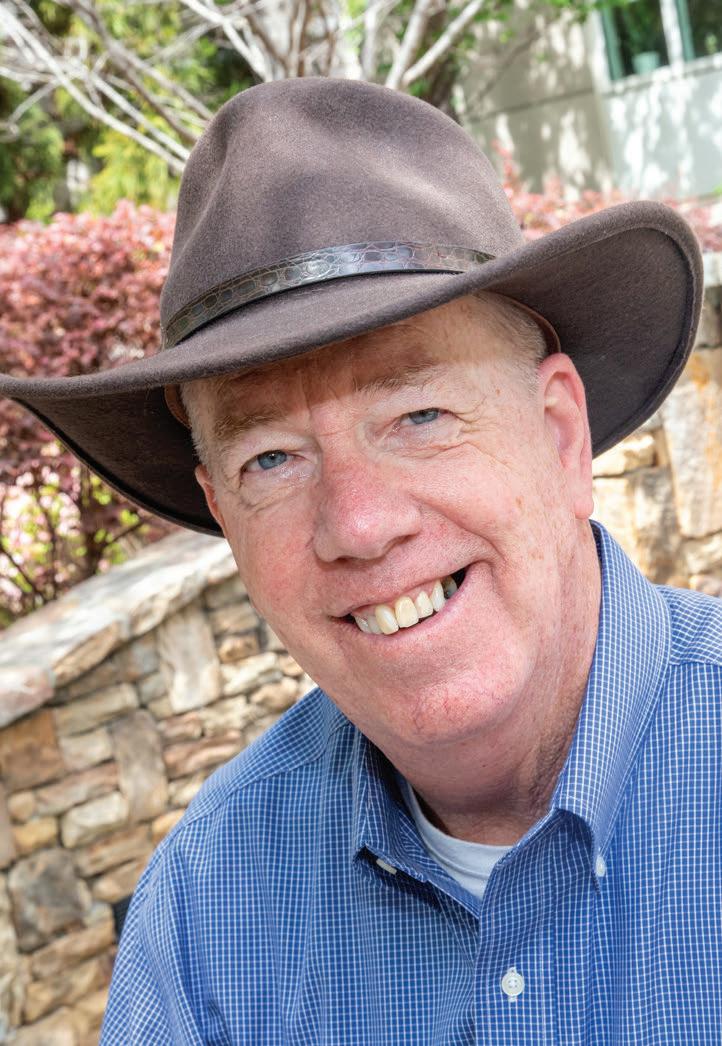

By the spring of 2015, 64-year-old Ronnie Redd had been dealing for years with a hazardously low blood platelet count. Transfusions and medication regimens just wouldn’t stabilize them for long. Finally, his local doctor urged Redd to seek an outside opinion. “I’m going to be honest with you,” Redd recalls his doctor saying. “I need some help. I want you to go to Emory, and let’s see if they can figure out what’s going on.”

The team at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University soon diagnosed Redd with myelodysplastic syndrome, a type of cancer in which a patient’s bone marrow no longer produces normal amounts of healthy blood cells.

That’s how Redd ended up in the office of Amelia Langston, MD, director of Winship’s Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplant Program and medical director of Winship’s Cancer Network, Winship 5K Research Professor and executive vice chair of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. A bone marrow transplant specialist, Langston treats patients with leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome and other blood cancers.

“I looked over all your records,” Redd recalls Langston as saying to him at their first meeting. She explained why a stem cell transplant was his best treatment option. He added, “She looked me square in the face, and she said, ‘I want you to understand one thing: I might kill you.’”

Eight years later, Redd is still very much alive, thanks to a successful transplant that included enrollment in a clinical trial for abatacept, a drug Emory researchers hypothesized would decrease incidents of graft versus host disease (GVHD), a sometimes-fatal transplant side effect where donor stem cells attack the patient.

Emory researchers led the phase II trial, following a smaller in-house grant-funded pilot trial that showed abatacept was safe to use in patients. The bigger trial looked at transplant patients receiving stem cells from poorly matched donors, which increases the chance the body will reject the newly infused cells.

When treated with abatacept, about 7% of completely unmatched patients developed life-threatening GVHD; without abatacept, more than twice that number developed GVHD. The numbers were even starker with slightly better, but still poorly matched, donors: 2% developed severe GVHD with abatacept; 30% without it.

The trial results were so significant that the FDA in late 2021 approved abatacept for acute GVHD prevention—the first drug ever approved for this use.

“Homegrown work”

“This was a dramatic effect any way you wanted to slice and dice it,” says Langston. “It’s always really gratifying when you work on something and it actually turns out to lead to something new that’s good for our patients.”

While the study enrolled patients from multiple hospitals around the country, it was led by Emory researchers. The largest cohort of participating patients, about a third of them, were cared for at Winship or the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

“This is very much homegrown work,” says Muna Qayed, MD, MsCR, director of the Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Children’sAflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Cancer Immunology researcher at Winship and associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine. It began in the research lab of former Winship

[ Winship Magazine | 24 | winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

IMAGE OF RONNIE REDDPHOTO: JENNI GIRTMAN

Ronnie Redd

investigator and Children’s faculty member Leslie S. Kean, MD, PhD, now director of the Stem Cell Transplant Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Qayed, who joined the multidisciplinary research team as a fellow, is a section chief carrying the work forward.

It was important to the doctors involved to keep the work based at Winship and Children’s, because they are ever-mindful that their medical center is based in a majority-Black community. Due to a complex host of factors, including a primarily white national donor registry, Black patients have the highest transplant complication rates.

“Our patients are considerably less likely to find a perfect match,” says Langston. Black people have about a 23% chance of finding a suitable donor on the registry, compared to about 77% for white people. Abatacept “was a big effect in a group of patients we expect are going to have a harder time with their transplant and have a higher risk that they’re going to die,” Langston says.

Indeed, transplants are arduous and risky even under the best possible circumstances. They involve a lengthy, isolated hospital stay to eliminate a patient’s own diseased bone marrow through high-dose chemotherapy, transplanting donor cells to replace them and then rebuilding immune system capacity. “While it is curative and

lifesaving for a number of different types of diseases, it also carries a lot of toxicity,” says Benjamin K. Watkins, MD, director of the Global Oncology Program at the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics researcher at Winship and associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine. “It’s an intense process to go through and, unfortunately, many patients don’t survive it.”

This means that any place in the process where doctors can minimize the things that can go wrong along the way, such as GVHD, will improve survival rates. “I believe 100% there are patients I’m seeing in clinic right now who are alive because of abatacept,” Watkins says.

An “incredibly fruitful partnership”

One factor that made the abatacept study’s results so powerful was its inclusion of both pediatric and adult transplant patients.

“It was very deliberate on our part,” says Langston, “that we wanted children to be part of this so that if this became standard practice, whether the FDA endorsed it or not, we had data to say whether it was safe and effective not only in adults but also safe and effective in kids.”

Opening the study to children as young as six years old was not an

automatic decision. In fact, youths are often excluded from new drug trials to protect them from unknown outcomes. But the partnership between Winship and CHOA researchers helped make sure all ages were represented.

“GVHD is equally as devastating in kids as it is in adults,” says Qayed. “Whenever we can represent pediatrics within these clinical trials, it speeds up the translation for these findings into the pediatric fields.”

The partnership went deeper than the participant population. The two institutions provided pharmacy support for the entire trial, and both places worked to support the data collection. And the relationships forged during years of intense collaboration created an environment conducive to mentorship, allowing younger clinicians like Qayed and Watkins to grow into more senior roles as their careers progressed.

Now, they are mentoring another generation of rookie researchers as the team builds on abatacept’s FDA approval with ongoing research that explores its potential uses in and beyond transplant.

“This was one of those classic benchto-bedside stories that really started here at Emory,” Langston says. “It’s just been an incredibly fruitful partnership.”

Redd, now retired, is living proof. While there’s no way to tell for sure whether he would have developed GVHD without abatacept, taking it helped ensure his survival.

Redd says the last time he saw Langston, she asked him, “How are you doing?’” He replied, “I’m doing fine; I pretty much do anything I want.’” To which he says she responded, “You do realize this is as good as it gets?”

“I do realize how blessed I am,” he continues. “It was the first time I’d ever been to Emory in my life, and I’ve got nothing but praise for everybody at Emory and their work, and their care.” w

[ Winship Magazine | 25 | Summer 2023 ]

IMAGE OF DRS. QAYED,

DE

WATKINS AND LANGSTON PHOTO: JAVIER

JESUS

Muna Qayed, MD, MsCR, Benjamin K. Watkins, MD, and Amelia Langston, MD

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 19 care to a diverse population of patients and who will be leaders in cutting-edge clinical and/or translational research.

Winship hematologist Martha Arellano, MD, professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, has been the fellowship program’s director since 2015. She notes that first-year fellows are paired with a “faculty buddy” who is a sort of “life mentor.” Next, as fellows move into their research-focused second year, they are paired with a research mentor. “The success of all of us really depends on the mentorship that is provided,” Arellano says.

Preparing the providers

The Department of Radiation Oncology, part of Emory University School of Medicine and Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, is committed to conducting cutting-edge research, delivering high-quality cancer care and training tomorrow’s physicians, medical physicists and radiation therapy professionals.

The department’s residency program for physicians—its 16 residents make it the fifth-largest radiation oncology residency program in the United States—follows completion of a one-year internship in internal medicine. The program prepares residents for radiation oncology-certifying examinations given by the American Board of Radiology. Residents master treatment procedures taught by faculty members at the Emory Proton Therapy Center. Residents also train at two affiliated locations, Grady Memorial Hospital and Atlanta VA Medical Center.

“One of the key strengths of the program is that our trainees have access to a very wide breadth and depth of training experience with the varied Winship cancer treatment facilities,” says Pretesh R. Patel, MD, who was program director until his recent appointment as the department’s vice chair for clinical operations. “The breadth and depth of the training is really unparalleled,” he says. “It sets our residents up very well to be successful for passing their board exams.”

Caring for a diverse population of patients is central to training the program’s now-17 fellows. Arellano, who was a fellow at Emory herself, says that something distinctive about Winship’s fellowship program is the opportunity it provides fellows to be trained in serving a very diverse population in Atlanta, where half the population are from racial minority groups. “At the end of the day,” she says, “what we’re doing is training those fellows to be excellent at taking care of all patients, no matter what walk of life they come from.” This is part of what Arellano calls the “art” of medicine, tailoring the approach to each patient as an individual.

Arellano says the fellowship program allows fellows to tailor their own education to their respective interests and professional goals. If they want to during their fellowship, fellows can pursue a master’s of science in clinical research or a certificate in translational research. “In general,” Arellano says, “one-third of the fellows pursue careers in community oncology or private practice careers. About two-thirds pursue academic careers in NCIdesignated Cancer Centers as clinical investigators or translational scientists.”

The Department of Radiation Oncology also offers a three-year training program accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Medical Physics Educational Programs (CAMPEP). Twentynine experienced board-certified radiation oncology physicists supervise the program at Emory University School of Medicine. It aims to provide comprehensive, structured education and training in a clinical environment that will prepare residents for certification by the American Board of Radiology in Therapeutic

[ Winship Magazine | 26 winshipcancer.emory.edu ]

C Around Winship IMAGE OF DR. ARELLANO WITH FORMER FELLOWSPHOTO: JAVIER DE JESUS IMAGE OF THE RADIATION ONCOLOGIST WITH RESIDENTS IN THE PROTON TREATMENT ROOM PHOTO: JENNI GIRTMAN

Emory Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Program director Martha Arellano, MD, with former fellows

Pretesh R. Patel, MD, former director of the Radiation Oncology Fellowship Program, with former fellows

Radiological Physics, and for a professional career in radiation oncology physics.

Anees Dhabaan, PhD, professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology, is the founder and director of the Medical Physics Residency Program. He explains that the three-year program includes a first year dedicated to research and two years spent in clinical training in medical physics—basically, he says, arranging “a complex geometry of treatments.” Medical physics includes three branches: nuclear medicine, diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy. There are nine residents in the program—three in the first research year and six in clinic at any given time. Each resident will go through eight three-month rotations before they graduate, each one at a different location and focused on different disease sites and using different treatment modalities.

Medical physicists plan and simulate radiation-related treatment, and provide quality assurance and patient safety for the doctors. For example, Dhabaan explains, treatment with proton therapy using the linear accelerator—a massive machine that accelerates electrons that are then concentrated into a pencil-size laser beam—requires first collecting data, including the characteristics of the beam’s penetration, how far and wide it will be, how much it’s going to be in the patient and when it’s going to exit their body. All the information is fed into a computer to generate a simulation showing the expected outcomes if something is done a particular way. “We train our residents to be as precise as possible,” Dhabaan says. “When they go in the field, I sleep very well because I know their patients are safe with them.”

Within Emory University Medical School’s Department of Surgery, the Division of Surgical Oncology offers two fellowship programs to train future surgical oncologists. Mentorship is key to both programs. The one-year Emory Breast Oncology Fellowship teaches two fellows a year—who already have completed a general surgery residency—evidence-based clinical care and encourages inquiry with a research-focused approach. “Mentorship is the cornerstone of surgical training,” says the fellowship’s director Cletus A. Arciero, MD, MS, FSSO, FACS, professor of surgery and chief of breast surgical oncology. He notes that what distinguishes the fellowship is its multidisciplinary approach to care. Arciero says, “This multidisciplinary approach pulls together all of the oncologic specialties, along with pathology and radiology, and then applies the overlay of clinical trials research and application, which is a crucial aspect of our weekly breast tumor boards.”

When it welcomes its first two residents in August, the twoyear Complex Surgical Oncology Fellowship will emphasize excellence in surgical training, intellectual curiosity in research, teamwork with oncologic care providers and appreciation for the art and science of compassionate care of patients with cancer.. The

fellowship’s director, Maria C. Russell, MD, Winship’s chief quality officer and professor in the Division of Surgical Oncology, says the fellowship will be distinctive in its emphasis on personalized medicine. “Cancer care must be individualized,” she says, “not only to the patient’s tumor type, stage and molecular makeup, but also must consider personal factors unique to that patient’s social situation, performance status and personal beliefs so that every patient’s care plan is specifically tailored to them.” Russell also stresses the vital role of mentorship. She explains, “A combination of assigned advisors and organic mentorship from our dedicated faculty will set our fellows up for success from a clinical, research and administrative perspective as they move into their attending career.”

A new nurse residency program for oncology

“I’m very passionate about nurses,” says Leslie Landon, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, Winship’s director of nursing education. “They go into nursing because they want to provide great care. I feel like my role is making sure that we have the things in place so they are confident that they are providing great care.” She says that if there is an unmet learning gap, “not only will our quality of care go down—which is not acceptable—but also their satisfaction with their role will go down because they have very high standards.

[ Winship Magazine 27 | Summer 2023 ]

Around Winship IMAGE OF ONCOLOGY NURSESPHOTO: STEPHEN NOWLAND

That’s who we hire. And to retain those people, we have to meet their learning needs.”

One way Winship is seeking to meet its nurses’ education and training needs is through a new nurse residency program for oncology. “We’ve never had this,” says Landon. “It’s enterprise-wide, so it will be for any new graduate coming in. Any inpatient unit or Winship ambulatory department nurses will come to this residency program, as well as experienced nurses who are new to oncology.”

Landon says the residency is a hybrid, using evidence-based, constantly updated training modules from the Oncology Nursing Society. Over the course of the residency year, one eight-hour class and six four-hour classes will be combined with in-person patient care. There is a class at the six-month mark to debrief because, Landon says, that’s “when people think their leaders have more confidence in them—and they have less confidence in themselves because they realize what they don’t know.” Another class at 12 months will focus on professional development. “Yes, you have your RN license, and thank goodness school is done. But we want to bring you to the next level and get you oncology nursing certified.” Passing an exam at the two-year mark will do just that.

Educating the community about cancer

Too often when someone thinks of community outreach and engagement (COE)—an activity required of all NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers—they think of health fairs or other awareness-raising activities such as screening or smoking cessation programs. Those are important, but they alone aren’t enough.

“There needs to be follow-up,” explains Theresa Wicklin Gillespie, PhD, MA, BSN, FAAN, Winship’s associate director

for community outreach and engagement and professor in the Department of Surgery at Emory University School of Medicine. “Because if all we needed to do was stand in front of the grocery store and say, ‘Hey, you need to get screened for breast cancer,’ or ‘Hey, you with the cigarette in your mouth, you need to stop smoking,’ we would all be 120 pounds and eating great, no one would be smoking and we’d all be riding bicycles to work.” She adds, “It just doesn’t work that way. It’s a stepwise process, and education and awareness can be a first step.”

The next step is gathering information, such as how many people actually got a cancer screening, enrolled in a smoking cessation program or showed up to get the HPV vaccine. Gillespie says Winship’s COE has been partnering with people across the state and funds “embedded staff,” who run the programs, navigate people to their screening appointments and make sure they get into the smoking cessation program. Winship also has developed an online database, Your Connection to Early Detection, of all the facilities in Georgia that offer free or low-cost cancer screenings.

Another COE initiative is the curriculum for community education that Gillespie and Adam Marcus, PhD, are developing. Funded by an NIH Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA), it uses cancer and other big data to bring cancer research to life in a practical, real-life way for middle school girls in under-resourced schools who are interested in STEM careers. Using real data from their own communities, the students have to go beyond merely analyzing the problem to make feasible action plans for addressing it. The final step is to share their proposed solution with people in their communities, who might say something like, “That seems like a clever solution, but here’s why it won’t work.” Gillespie says this feedback is helpful for the students. She says it also shows that cancer is “not an academic problem, but a real problem in their own backyard.”

Introducing high school students to the clinic and lab