DROUGHT DIMINISHES

For first since since 2019, no part of NE Oregon is in drought

Storms drive away the drought

Farmers, ranchers optimistic about water supply

BY JAYSON JACOBY | BAKER CITY HERALD

BAKER CITY — Curtis Martin was pleased to see pools of water where he had never seen them before. He just hopes the water doesn’t start moving.

Martin, a cattle rancher who lives near North Powder, is more accustomed to worrying about a shortage of water than a surplus.

The grazing land he owns in the Cow Valley area of northern Malheur County, along Highway 26 between Ironside and Brogan, is far more often desiccated than it is moist.

But a series of snowstorms in early February, followed by a thaw later in the month, spawned the ponds that Martin saw during a visit to his range ground in early March.

The standing water raises the prospect for a lush crop of grass that Martin’s cattle — and the herds that dozens of other ranchers depend on across the region — can munch on this spring and summer.

The reason his optimism is tinged with concern has to do with fire.

In July 2024 the Cow Valley fire, an arson-caused blaze that remains under investigation, spread across 133,490 acres in northern Malheur County, propelled by gusty winds.

“If it rains like it can, that’s just great. But the stars have to line up.”

— Mark Ward, Baker Valley farmer

Martin, who grew up in the area, graduated from Vale High School in 1973 and owns about 6,000 acres around Cow Valley, used a bulldozer to carve firelines that saved his family’s 50-year-old cabin from the flames.

Although he appreciates the snow, which should soak into the ground and help scorched grasslands recover, Martin fears that heavy rain this spring, especially if combined with high temperatures that rapidly melt snow at higher elevations, could lead to flash floods that scour soil off steep slopes.

“My biggest concern for my property is warm weather,” Martin said on March 5. “We could lose a lot of soil to erosion.”

He said the places where the fire burned hottest are especially vulnerable.

Those areas, with little or no vegetation on the surface, or roots below ground, have little resistance to moving water.

Martin estimated that 80% to 85% of his grazing land burned, with the severity ranging from light to extreme.

In places the fire killed everything, including the relatively deep roots of the native Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass that made the area so valuable for livestock grazing.

On the positive side of the ledger, Martin said that if the spring weather is benevolent, with occasional rain but no extended downpours, the recovery of burned land should get something of a jumpstart.

November 2024 was wetter than usual across Northeastern Oregon.

And the rain fell before the ground was frozen, so the water percolated into the soil.

Most of January was dry, but the early February storms piled a prodigious mountain snowpack, a primary source of water, including for irrigation.

Periodic storms continued into early April, keeping the snowpack well above average across most of Northeastern Oregon.

“It’s looking great,” Martin said.

A center-pivot sprinkler in the Baker Valley with the snowy Elkhorn Mountains in the background on March 31, 2025. Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald

Reprieve from drought

Martin isn’t alone in noticing the unusually saturated situation in Cow Valley and elsewhere.

Mark Bennett, who with his wife, Patti, owns a cattle ranch near Unity, in southern Baker County, frequently drives Highway 26 to Vale, a route that passes through Cow Valley.

What drew Bennett’s eye — and provoked a chuckle or two — is the highway bridge over Cow Creek.

Bennett, a former Baker County commissioner, said in more than 40 years of living nearby he’s rarely seen any water in this stream — and then the flow was a trickle rather than a torrent.

But on March 11, while driving east to Vale to pick up some ranch equipment, Bennett realized, as his truck approached the bridge, that Cow Creek was at least living up to its name.

he said, so surprised he was by the vigorous volume of snowmelt tumbling down the usually arid channel among the sagebrush.

Bennett was amused, as well as shocked, because of a sign that used to be posted at that bridge.

The sign warned against jumping from the structure.

“I almost pulled over and took a picture,”

Given the almost constant absence of water below — the typical thing that lures people to leap from bridges — Bennett said he always wondered what had prompted the seemingly superfluous sign.

Bennett said he’s optimistic about the water outlook this year based on the snowpack.

“So far it seems to be pretty good,” he said. “There was heavy runoff this past weekend, and it seems to be soaking in.”

Whether the streams and springs on his ranch continue to flow well into summer depends on how much rain falls this spring.

Regardless, Bennett said the situation is much more promising than it was for several years in the past decade, particularly from around 2019-22, when drought dominated.

The weekly U.S. Drought Monitor reflects Bennett’s optimism.

Since March 19 the map of Oregon has been blank, meaning no part of the state, including the northeast corner, was in a drought — or even rated as abnormally dry, the category that precedes the four levels of drought: moderate, severe, extreme and exceptional.

That hadn’t happened since November 2019.

Watching a reservoir

Mark Ward doesn’t choose Martin’s superlative when asked to describe the moisture situation in his family’s crop fields in early March.

“I think we’re medium, average, right down the middle,” said Ward, whose family grows peppermint, potatoes, wheat, alfalfa and silage corn in Baker Valley Ward said he was grateful for the snowstorms in early February, and disappointed that the snow, at least at lower elevations, melted within a couple weeks.

“I wasn’t ready to see winter be over with,” Ward said. “I’d like another foot of snow.” Winter did indeed linger in the mountains. A couple of Pacific storms that swept inland during mid-March, and another period of wintry weather at the end of the month continuing into the first couple days of April, bolstered a mountain snowpack that in parts of the region hovered near record highs for much of the winter.

The snowpack is especially bountiful in the southern half of the Wallowa Mountains, on the west side of the Elkhorns and in parts of the southern Blue Mountains, including the Strawberry Range.

The water content in the snow — a statistic more relevant, in predicting water supplies, than snow depth — is also above average in much of the northern Blue Mountains, but not as far above as in other areas.

Melting snow, in addition to replenishing ground depleted during the drought that has prevailed for much of the past decade, also trickles into reservoirs.

For Ward, the key impoundment is Phillips Reservoir, along the Powder River about 17 miles southwest of Baker City.

Continued on page 6

Sporting a driftwood brown faux leather with a gently distressed sense of charm, this sectional invites you to drift away in high style. Rest assured, the sectional’s leather alternative upholstery offers a warm, cozy feel, while clean-lined styling and jumbo stitching deliver the cool, contemporary look you love. Factor in power reclining motion, USB charging, convenient cup holders, and a drop-down table, and you’ve got all the makings for the best seats in the house.

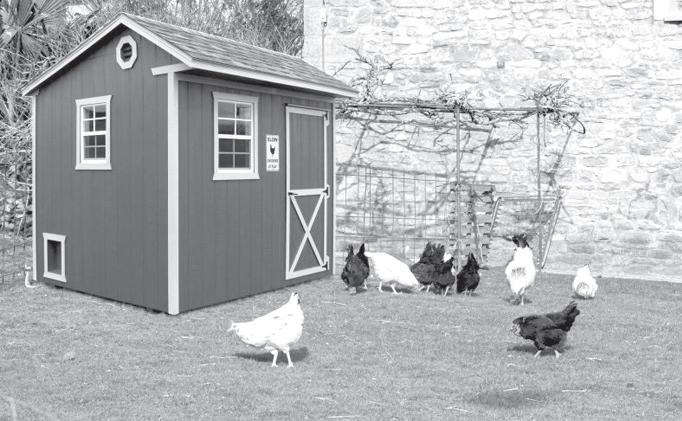

Curtis Martin

Mark Bennett

Its waters irrigate more than 30,000 acres, mainly in Baker Valley.

Ward is a board member for the Baker Valley Irrigation District, which manages water releases from the reservoir, which was created when Mason Dam was finished in 1968.

Phillips Reservoir hasn’t filled since 2017.

And Ward doesn’t expect that streak to end in 2025.

He said board members, based on the reservoir’s level in early March — about 33% full — concluded that it’s likely to top out

around 75% of capacity.

Phillips is considered full at 73,000 acrefeet, although it can store more water if needed for flood control.

(One acre-foot of water would cover one acre of flat ground to a depth of one foot. The figure is equal to about 358,000 gallons.)

Based on that prediction, Ward said he and other farmers who have rights to water stored in the reservoir likely will get from one acrefoot to 1.5 acre-feet of stored water per acre of irrigated ground.

When the reservoir is full, their allotment can be as much as 3.5 acre-feet per acre.

Phillips began refilling rapidly during March due to a period of warmer weather that started to melt snow at lower elevations in the Powder River basin. As of April 1 the reservoir was 52% full.

Although snowpack has the biggest influence on the reservoir level, other factors can play a role as well, Ward said.

Spring rain is the most important, particularly if it falls before early to mid June. Rain helps in two ways, Ward said.

The obvious benefit is that rain keeps fledgling crops moist.

But also, generally speaking, the more rain that falls during April, May and the first part of June, the less water the irrigation district has to release from the reservoir.

“If it rains like it can, that’s just great,” Ward said. “But the stars have to line up.”

Although May is on average the wettest month in Baker Valley, and June ranks second, Ward said the gusty winds that often follow spring rainstorms can quickly dry the top layer of soil, forcing farmers to use more irrigation water than they otherwise would.

Another factor is fire.

Two blazes, one in 1989 and the other in 2015, burned thousands of acres on and around Dooley Mountain, about a dozen miles south of Baker City.

The fires killed most of the trees in the previously dense forests of pine and fir, and without their shade, the snow melts earlier in the spring than it used to, Ward said.

Those areas are downstream from Phillips Reservoir, so the melting snow flows into the Powder River and can’t be stored.

Ward said that before the 1989 fire, melting snow from Dooley Mountain in some years fulfilled the demand for irrigation water in much of Baker Valley, allowing the irrigation district to save most of the upstream runoff in the reservoir.

Grateful for last fall’s rain

Although spring rain is especially valuable for farmers, storms that happened several months ago have a lingering benefit, Ward said.

That’s especially true for mint, a shallowrooted crop.

Ward said autumn rain, if it falls before the ground freezes, can moisten the top 6 inches or so of soil, including the mint plants’

root zone.

Mint thrives in such conditions, he said, and in the year after a damp fall the plants tend to produce more of the pungent oil that is distilled and then sold to companies that use the liquid to flavor products such as toothpaste and chewing gum.

“It’s a huge benefit,” Ward said. “This is the first time in 10 years or so that our mint went to bed, so to speak, adequately hydrated during that crucial period. That benefits the health of the plant going into winter.”

Commodity concerns

Ward said markets for many regional crops, including wheat, alfalfa, barley and silage corn, are not promising.

Although his family’s operation is still called Ward Ranches, reflecting its history in the cattle business, they sold their herds in the early 1990s.

AgWest Credit Union issued its spring commodity outlooks on March 12.

Cattle

“Low cattle inventories continue to sustain strong margins for most cow-calf producers,” AgWest reported. “Improved moisture in the

Pacific Northwest and Montana has eased the need for herd reductions, while drought in the Southwest and Midwest has sharply cut cattle numbers. Sustained dry conditions in most major cattle producing areas are expected to constrain herd rebuilding which will support cattle prices through 2025.”

Wheat

“Wheat producers face another challenging year in 2025. Prices are projected to remain below breakeven levels, fluctuating between $5.45-$6.00 per bushel in 2025,” AgWest reported. “Growers also face higher costs including rising repair and maintenance costs, along with inland basis and transportation expenses exceeding $1.00 per bushel. This follows on the heels of a difficult 2024, where most growers experienced financial losses and decreased working capital.”

Hay

“Hay producers face a difficult operating environment marked by low prices, higherthan-normal inventory levels and increased operating debt,” AgWest reported. “To move inventory, some growers are selling hay at discounted prices.” LA GRANDE (541) 963-2136

(541) 437-3484

(541) 426-3177 BAKER CITY (541) 524-1984

Looking to the sky

Winter rains indicate average wheat yield for upcoming season

BY BERIT THORSON AND YASSER MARTE EAST OREGONIAN

IONE — Green wheat stalks just barely poked through the soil of a rolling hill in Ione as fourth-generation farmer Clint Carlson talked about the moisture content this winter.

“The thing is, you know, we’re at the mercy of the weather,” Carlson said. “ This time of year, you want calm weather so you can get out and get your field work done, but you’re always hoping for that next cloud to come over the hill and drop some rain.”

Carlson is one of many dryland wheat farmers in Morrow and Umatilla counties partway through the growing season of his winter wheat crop. Harvest is still months away, but as the wet season ends, he and other farmers are keeping close watch over their plants.

According to Carlson and Oregon State University Extension researchers based in Pendleton, the outlook for the wheat harvest is about average. In areas closer to the Blue Mountains in eastern Umatilla County, where it rained a little more over the winter, the yield may even be higher than normal.

Rainy season recap

In drier parts of the region, farmers like Carlson, who gets eight to 10 inches of rain per year, may average 3540 bushels per acre, which is about what Carlson expects from the upcoming crop. The fall of 2024 was pretty dry, he said, though it did get wetter going into winter, which balanced out the lack of moisture. Unless a lot of rain comes in spring and early summer, he said, it will likely be an average year.

But the final outcome depends a lot on the last rains of the season coming during May and into June.

“ Sometimes you get it and sometimes you don’t,” he said. “Last year we did and that’s why we had a good crop. The year before, we didn’t hardly get any rain and we had a really bad crop.”

Francisco Calderon, director of OSU’s Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center, said rains in the Pendleton area — a moderately dry region that sees an average of 16 inches of rain per year — were slightly above the average during part of the winter. February, for instance, had 1.9 inches of rain, which is about 128% above the 30-year average. And beyond that, the region isn’t currently in a drought, nor is one expected.

The rains refill the soil profile with moisture to sustain the wheat even when the heat comes in the summer, making it one of the most significant factors in the outlook for dryland wheat, which doesn’t get the benefit of irrigation from sprinklers.

“With all that in consideration, I would say that we are on track to hit good yield numbers this year,” Calderon said.

The Adams-based research station’s wheat crop may reach 100 bushels per acre or beyond if the rains continue, he said.

High costs, low prices

According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, nationally, overall wheat harvest was up in 2024 despite a decrease in acres planted. Wheat production has been declining since the 1980s, and is down by about 800 million bushels now compared to 1981.

In the Pacific Northwest, though, most of the wheat planted and harvested is soft white wheat, which is used for baked goods like cakes and pastries. Oregon, Washington and Idaho produce about 95% of soft white wheat that is exported, according to Amanda Hoey, CEO of the Oregon Wheat Commission and the Oregon Wheat Growers League.

A fallow wheat field in Ione March 21, 2025, awaits being cut down before the soil is seeded again this fall. — Berit Thorson/East Oregonian

Although yields nationwide might be up, so are costs, and prices aren’t following.

“ We’ve certainly seen a continued period of low wheat prices, very competitive global markets on wheat,” said Hoey. “We have seen a rebound in some of those export sales, particularly for soft white wheat in comparison to last year, in particular, but we continue to experience low prices.”

Carlson echoed Hoey, adding that input costs — for things such as fuel, herbicide and fertilizer — since the pandemic have “just skyrocketed,” but prices per bushel generally haven’t.

“ It’s hard when your prices are so low,” Carlson said. “ It’s hard to put a budget together that you can cashflow a profit out of it and so we depend on crop insurance and those kind of things to help us out to make into the next year.”

Disease, weeds also a factor

Prices aren’t the only challenge wheat farmers contend with. Like other growers, they deal with diseases and weeds.

Stripe rust is a common fungal disease affecting wheat. Researchers are working to combat stripe rust susceptibility with disease-resistant wheat strains.

According to OSU, stripe rust spreads more easily in wetter and more humid conditions. The later the fungus appears, the better off a grower is, as that means the disease will have less time to spread. OSU’s Calderon said the cold spell in February, with temperatures dropping into the single digits, likely means stripe rust won’t be too bad this season.

Hoey said growers rely on plant pathologists to help monitor diseases and give early indicators of what to keep an eye out for. That helps them figure out what herbicides to use for weed control and how to approach disease spread.

Some diseases and weeds are becoming resistant to intervention. Russian thistle and mustards will compete with wheat for resources, Carlson said, so he’ll generally spray a broadleaf chemical sometime in April if it’s needed. He works with OSU’s weed scientist to combat Russian thistle and find herbicides it’s not resistant to.

Calderon said it’s similar to antibiotics in people. “Antibiotics are changing their efficacy for controlling different infections,” he said, “so that’s kind of what’s going on with some herbicides.”

Harvest preparation

Between March and July, farmers will be preparing for harvest. This includes checking equipment, possibly spraying herbicides in areas that need it, and adding fertilizer if necessary to help the plants grow.

“ The healthier the crop, the less disease you have, the less weed pressure you have, and so you want to make sure that it

is growing and it’s healthy and it matures with a good head, with lots of kernels and that kind of thing,” Carlson said. Then, come July and into August, he’ll start harvesting when the wheat kernels are golden and crunchy. By September and October, the process will start over again.

For now, he and other growers will keep an eye on the sky and hope for those early summer rains.

Fourth-generation wheat farmer Clint Carlson stands in front of his crop March 21, 2025, at one of his fields in Ione. Carlson said he expects an average yield this year. — Berit Thorson/East Oregonian

Fire effects linger with high prices for grazing

Lower hay costs could help offset some of the increase

By JUSTIN DAVIS | BLUE MOUNTAIN EAGLE

JOHN DAY — Last year’s wildfires don’t appear to have affected hay and alfalfa prices, but they may be contributing to rising private grazing costs.

Last summer, a particularly active fire season led to the torching of over 317,000 acres in Grant County, nearly 11% of the county’s total area. Some farmers and ranchers, like M.T. Anderson of Canyon City-based High Desert Cattle Company, saw significant grazing allotments go up in flames last summer.

“We lost 30,000 acres of grazing lands,” Anderson said.

What did not burn however, were pastures where hay is raised, which is keeping costs of cattle feed down, according to Rusy Inglis, the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association District I Vice President.

“It didn’t burn up hay ground — rangeland yeah,” he said. “It burned up where people are going to need to turn out this spring on and they won’t be able to, so they’ll have to find alternate pastures to go.”

Anderson manages several hundred commercial cows and needed alternate grazing lands for them in the aftermath of the wildfires, which burned while thousands of cattle were grazing on their usual summer pastures. He’s been able to secure alternate grazing lands to cover the 30,000 acres lost this summer with the help of the Forest Service.

“In this case, they’ve been a big help,” he said.

While Anderson said he thinks he’s going to emerge from last year’s wildfire season in good shape, he did raise alarm about the rising cost of securing private grazing allotments.

“Some of the costs of private pasture, some of the prices I’m hearing are insane,” he said.

Scarcity of grazing lands and rising costs in utilizing them could ultimately drive up hay prices as farmers and ranchers grapple with the need to feed their cows and the situation on the ground.

“It could possibly drive up the cost, because if they can’t find alternative grazing, and they have to do feed earlier than normal, then you have to buy more hay, and that could drive up the cost if there’s a shortage of it,” Inglis said.

Inglis stressed that he doesn’t know of anybody predicting a sharp increase in hay prices at this time, however.

Scorched rangelands could recover relatively rapidly because the fires generally were low-intensity burns.

“If invasive annual grasses were absent from these areas, then this type of burn will likely either benefit or have neutral impact to rangeland vegetation,” Grant Soil and Water Conservation District Manager Kyle Sullivan said.

Sullivan said the snowpack is encouraging this year and moisture levels in the soil are good. “More periodic rainfall, less wind and seasonable temperatures will help production,” he said.

That all lines up with Anderson’s assessment of his situation. Despite all of the uncertainty from last year’s busy wildfire season, Anderson said High Desert Cattle Company will be just fine.

“We’re going to land OK on this,” he said. “Better than some other people.”

A group of cows emerge from the Rail Ridge fire in Grant County unharmed. — M.T. Anderson/Contributed Photo

WALLOWA COUNTY

Farmers express optimism as crop year starts

Planting hasn’t yet started, but growing conditions look good

By BILL BRADSHAW | WALLOWA COUNTY CHIEFTAIN

ENTERPRISE — As winter arrived a bit late this year, most farmers in Wallowa County are waiting to get in the fields to start the year’s planting.

Recent snows blanket many of the fields in the county and only fall-planted winter wheat and alfalfa hay have really made any progress, a couple people in the know said March 18.

The crops

“Fall-planted wheat is in, but other crops haven’t been planted yet,” said Pete Schreder, Oregon State University Extension’s livestock, range and natural resources agent for the county.

Kevin Melville of the family-owned Cornerstone Farms Joint Venture agreed, adding that the fall wheat and alfalfa appear to have survived the winter well.

“Fall wheat, from what we can tell, has come through the winter just fine,” Melville said.

Cornerstone, with about 5,000 acres it either owns or leases in the county, has a wide variety of crops, including hay, timothy grass and forage mixes, as well as small grains like wheat, barley, oats, peas, canola and lentils. It’s a no-till operation, Kevin’s dad, Tim Melville, said.

Since 2008, the Melvilles have sold some of their premium wheat to an orthodox Jewish bakery in Brooklyn, New York, to make matzoh for Passover. The Jews come out to the county and examine the grain closely to ensure there is no germination activity, which would prevent it from being kosher.

Tim Melville said they hope to get the wheat that will be sold to the Hasadim this month.

Kevin agreed, and he’s counting on good weather soon.

“Looks like it’ll be good early next week. We want to get it in before end of March for (next year’s) Passover,” he said. “There’s a lot of snow on most of our fields.”

He said Cornerstone expects to plant it on 114 acres of the first field it seeds.

Biosolids

The Melvilles have another issue that’s been bothering some folks around the county. They’ve recently agreed to accept biosolids gleaned from the wastewater treatment plant of the city of Enterprise to use as fertilizer. The city will pay Cornerstone $4,500 a year to take the waste off its hands since the Wallowa County Landfill has decided it’s running out of room for the biosolids.

Kevin Melville said the federal Environmental Protection Agency has decided conditions are right on the land Cornerstone wants to use for the waste and approved the plan.

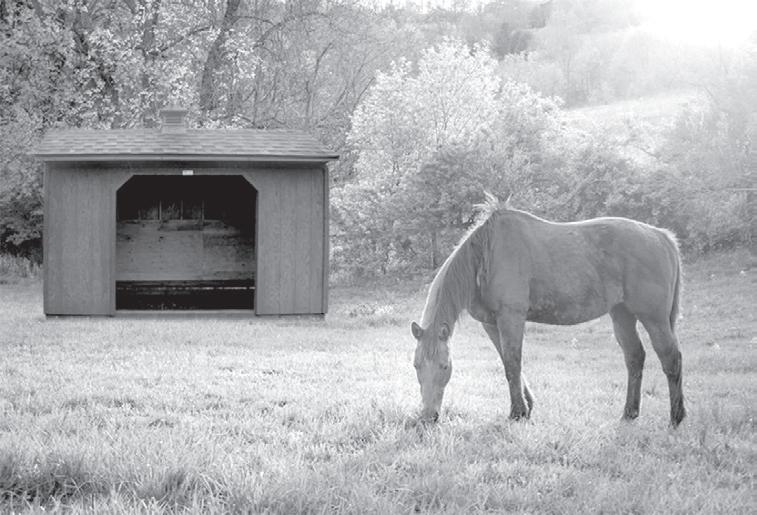

Bill Bradshaw/Wallowa County Chieftain Farmers have yet to get in the fields, but ranchers need to feed their animals all year long. Here, bales of hay are offloaded at Jason Dunham’s ranch along West Russell Lane near Joseph. A couple years ago, one of Dunham’s heifers gave birth to triplets. All three grew to maturity and “they’re food now,” Dunham said March 19, 2025.

He said the amount of land the city is going to distribute the biosolids on is minimal, compared to the overall farm. The city is “going to put that on 40 acres a year, so it’s not a big thing.”

Melville said Cornerstone plans to distribute the biosolids on land it farms off of Leap Lane north of Enterprise.

“A gentleman (from the EPA) said our soils are in good condition and we could apply them,” he said.

Pests

Last fall, the Oregon Department of Agriculture issued a report on infestations of grasshoppers and Mormon crickets in Northeastern Oregon. The counties listed in the report did not include Wallowa County, but Schreder said there have been reports of Mormon crickets on rangeland in the county.

However, there have been other pests here. A couple of years ago, there was a serious infestation of army worms, and field agronomists have been watching out for them ever since, as well as setting traps.

“We just wanted to make sure no outbreaks like two years ago,” he said. “We’ve been fortunate.”

So far, Schreder said, there has been little sign of the worms, though they would most likely show up in the fall.

Soil moisture

The other thing farmers always find necessary is water for their crops. The winter hasn’t been particularly wet, though there is a healthy snowpack in the Wallowa Mountains and the Wallowa Lake level is robust.

Schreder said he didn’t have the figures on the snowpack, but he expects it’ll be all right.

“A bit hit and miss. … In last month, still bit dry but we’ve got a good snowpack. We should have a good crop year.”

Kurt Melville, Kevin’s brother and business partner, said the water availability is still a bit of an unknown.

“We’re still waiting to see after snow melts. I expect it’s about average, but really won’t know until we start working things,” he said. “For irrigation, I expect we’ll be doing all right, but it depends how fast it melts. Even if you have good snowpack, it’ll depend on storage.”

Kurt Melville summed it up for what farmers will be looking for.

“We’re hoping the price of wheat goes up,” he said. “That’s what we’re watching to see if we can make money this year.”

Kevin agreed and voiced some optimism.

“The price of soft white wheat went up in the last month about 40 cents a bushel,” he said.

BOARDMAN

Shane Lazinka

541-481-3445

BURNS

Laura Georges

541-573-2006

CONDON

Amber Schlaich

541-384-3501

ENTERPRISE

Bob Williams

541-426-4205

HEPPNER

Amber Schlaich

541-676-9125

HERMISTON

Kolby Currin

Jared Lathrop

541-303-8274

Shane Lazinka 541-422-7466

JOHN

Bob Quinton

541-575-1862

LA GRANDE

David Stirewalt

Kristy Nelson

541-624-5040

MADRAS

Jon McPhee

541-475-7296

MORO

Shane Lazinka

541-565-3712

ONTARIO

Jed Myers

Nial Bradshaw

Stacie Talbot

541-889-4464

PENDLETON

Mike Short

Tracy Hamby

541-276-6509

BAKER COUNTY

Bushels of awards for Baker Valley farmer

Jess Blatchford has won two straight national prizes for his irrigated spring wheat crops

BY JAYSON JACOBY | BAKER CITY HERALD

BAKER CITY — Jess Blatchford never thought of growing wheat in the Baker Valley as a competition until he started winning national awards.

Although he concedes that the valley’s weather, which can careen from scorching sun to a snow squall in little more than a day and paint wheat stalks with frost in any month, makes for a formidable foe.

Blatchford heard about the National Wheat Yield Contest, run by the National Wheat Foundation, several years ago.

But he didn’t consider entering.

Until a couple years ago, when a friend who is a representative from a company that sells seed corn happened to look at one of Blatchford’s irrigated spring wheat fields while they were touring the farm.

“She said I should enter” the wheat contest, Blatchford said.

He had no idea what sort of yield he’d need to compete for a prize in the irrigated wheat category (there is a separate category for dryland wheat).

But in 2023 he decided to enter.

Blatchford’s 150-acre field produced 164.5 bushels per acre of soft spring wheat.

A good harvest, he said, but not his best.

Blatchford was surprised, then, when his 2023 crop placed first.

Only one entry — from his longtime friend Dallin Wilcox of Rexburg, Idaho — had a higher yield, winning the “Bin Buster” title.

After that unexpected result, which included a trip to Houston to collect the award at the annual Commodity Classic trade show in early 2024, Blatchford said he figured he ought to enter again.

Despite the hottest summer on record in Baker Valley, his 2024 crop, grown on 150 acres adjacent to the 2023 award-winning field, was even more prodigious, at 174.7 bushels per acre.

Blatchford won the Bin Buster award, swapping places with Wilcox, who placed first with 169.9.

Another prize and another trip to the Commodity Classic in early 2025. This year’s event was in Denver.

Blatchford shrugs when he talks about his consecutive awards.

“Just lucking out, in my opinion,” he said.

Still and all, Blatchford, 46, said he has enjoyed the new experience of putting up his wheat crop against fields nationwide.

“It’s a lot of fun, and I’ve met a lot of people from across the country,” he said.

And although like any farmer Blatchford has ample financial incentive to try to grow the best crop possible, he said the wheat contest adds a new element to the endeavor.

“It makes it fun to just see how much you can push the limits of the (wheat) variety,” he said. “What is the maximum it can sustain?”

Both the 2023 and 2024 award-winning crops were grown from the WestBred WB 6341 seed. Blatchford said the variety, developed about 20 years ago, was grown in southern Idaho, where the climate is comparable to Baker Valley’s.

He said he started using the seed about seven or eight years ago.

But the variety wasn’t available this year, so Blatchford planted a similar seed on this year’s competition field, 150 acres just south of the field that won in 2023.

‘Four fields in one’

This year’s crop, planted in early April, will grow on ground that typifies the varied nature of the farm where Blatchford and his wife, Chelsea, and their sons, Sawyer, 16, and Carter, 12, raise potatoes and field corn as well as wheat.

The soil across the 150 acres ranges from relatively dry to “all but a swamp,” Blatchford said with a chuckle.

“It’s like four fields in one,” he said.

Moisture isn’t the only variable that can change dramatically across a single field, though.

Blatchford said his farm is partially underlain by an alluvial fan from the Elkhorn Mountains, which rise more than 5,000 feet just a few miles to the west. An alluvial fan is a mixture of gravel and sand washed into the valley from streams, such as Rock and Pine creeks, that chew away the sedimentary and metamorphic Elkhorns.

“This valley is different from about anywhere when it comes to soil,” Blatchford said.

His dad, Dave, who died in 2020, started dealing with those challenging soils when he moved from Hillsboro to Baker Valley in 1970, several years before Jess was born.

Jess Blatchford said wheat has been “sort of the baseline crop” for the family ever since.

They added potatoes to the operation in 1987.

Blatchford grows both spring wheat, which as its name implies is planted in the spring, as well as winter wheat, which despite its name is planted in the fall.

A spring storm over a field of winter wheat on Blatchford farms in Baker Valley on March 31, 2025. — Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald

examines frost-damaged potato plants in a Baker Valley field on June 20, 2023.

Both types are harvested in the summer.

Blatchford said that although it’s possible to grow dryland wheat in Baker Valley — relying solely on precipitation to irrigate the crop, as is done in much of the Columbia Basin — the paltry yields don’t make it economical given the size of the farms.

Blatchford plants spring wheat as part of a rotation that includes potatoes and corn.

He said he typically plants spring wheat in fields that the previous year produced corn.

The advantages include timing.

Because corn is harvested late in the fall, often in November, there wouldn’t be time to plant winter wheat, Blatchford said.

Following corn with spring wheat also helps combat one of his chief weed scourges, cereal rye.

The rye, which Blatchford said was brought to Baker Valley in hay in the early 1970s, germinates in the fall. By tilling a former corn field in the spring, just before sowing wheat, he can nip the cereal rye before it gets a roothold, resulting in a “cleaner crop of wheat.”

Cereal rye is stubborn, though.

“If there was a market for it, it wouldn’t grow here,” Blatchford said with a rueful smile. “It grows really good, and it matures faster than wheat. It’s been a 50-year-plus project to get rid of it.”

Weathering the wheat market

In common with wheat growers across the state and nation, Blatchford has had to navigate a rough patch in the market the past couple years.

“Prices are lower than we’d like to see,” he

said. “And we don’t really know why.”

Much of the region’s wheat is exported, Blatchford said. Asia is the main market, where soft wheat is ideal for making flour for noodles.

But the past two years, Blatchford said he has sold his wheat crop as an ingredient in cattle feed, including Baker City Cattle Feeders, on the opposite side of Baker Valley, and to Beef Northwest, which has feedlots in Nyssa and Boardman.

On the positive side of the ledger, as rain sluiced down on the last day of March outside Blatchford’s shop at the intersection of Brown and Pole Line roads, and fresh snow whitened the forests that cloak the Elkhorns, he said he’s optimistic about the growing season ahead.

“I think it’s shaping up to be a fairly decent water year,” he said.

Blatchford doesn’t have rights to irrigation water stored in Phillips Reservoir. He relies on wells and, early in the season, on snowmelt that swells Rock and Pine creeks.

As always he hopes for ample rain during April and May. More rain means less need to irrigate.

Blatchford also likely will endure a few restless nights in late spring, wondering if the temperature will dip below freezing, a threat that some years extends beyond the summer solstice.

Late frost typically poses a greater threat to budding potatoes than to spring wheat, he said.

Blatchford said he plans to continue entering the wheat contest.

Although he expects that he might soon have competition close by.

Jess Blatchford

— Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald, File

Eyes to the skies

Baker County 4-H, BMCC hold program about drones and agriculture

Drew Leggett, a precision agriculture instructor at Blue Mountain Community College, led a special program about drones and agriculture on March 10, 2025, for the Baker County 4-H program. — Katie Hauser/Contributed Photo

BY LISA BRITTON | BAKER CITY HERALD

BAKER CITY — Drew Leggett teaches at Blue Mountain Community College in Pendleton, but he also hits the road with a mobile lab to teach youngsters around Eastern Oregon about new technology in agriculture.

On March 10, he led a special program with Baker County 4-H to talk about drones, and let the kids operate one in the show barn at the fairgrounds.

“Drones are one of the many tools farmers have,” said Leggett, a precision agriculture instructor at BMCC.

He secured a USDA grant several years ago for a Mobile Precision Agriculture Laboratory focused on precision

agriculture, which simply means applying water, seeds and fertilizers to the right places and the right times to maximize yields.

“The end goal is helping farmers increase the profit margin,” he said.

Leggett presents at clubs, schools and fairs by providing information but also, most importantly, giving people a chance for hands-on experience with drones and a side-by-side with automatic steering and a GPS-controlled sprayer.

With the 4-H’ers in Baker City, Leggett encouraged the youngsters to study the barn floor as if it were a field.

“There was one place with standing water,” he said.

In conversation, the group decided that could, in a field,

indicate a natural spring that provided more moisture to a certain area.

“That will have to be managed differently,” Leggett said. Another spot looked white, which they described as alkaline soil.

“It’s not going to grow crops well,” he said. Applying technology in real-world situations helps young people understand, he said.

“If they can see it, that helps it sink in,” he said.

Of course, precision ag isn’t just about the cool gadgets — a drone project could include mission planning, flying the field, collecting data and analyzing it to create a “prescription” for the sprayer.

The job market

Leggett also sees the mobile lab as a way to get kids interested in precision agriculture careers.

“It has a job growth rate significantly higher than other jobs,” he said.

When he presents to high schools, he is joined by industry partners who can talk about job opportunities.

BMCC has a two-year program in precision agriculture, and Leggett said it’s the only one like it in the Pacific Northwest.

Leggett is a 2005 graduate of Baker High School, and attended BMCC and Oregon State University through Eastern Oregon University. He earned a degree in ag sciences, with a minor in business administration, then completed his master’s in plant science at the University of Idaho. He’s worked for BMCC since 2018. He was, he said, a student who learned best through experience.

“I’m a hands-on learner, and I discovered I liked hands-on teaching,” he said.

Although, he admits that in high school he never considered teaching — until a counselor mentioned it as a possibility.

“I wish I could shake his hand,” Leggett said. “Teaching was a good idea.”

The 4-H connection

Hands-on experiences is a particular goal of the 4-H program, said Katie Hauser, 4-H program manager in Baker County.

“At 4-H, we offer hands-on learning experiences across multiple disciplines, from mechanics, arts, performance, leadership, livestock and more,” she said. “These programs help youth build skills while sparking curiosity and excitement. Through partnerships with GO-STEM, OMSI, and Blue Mountain Community College, we connect kids with experts to explore specific areas of interest.”

For updates on future programs, visit the Facebook page for OSU Extension Baker Co. 4-H Oregon.

“We’re committed to helping youth discover their passions and prepare for the future, while enriching their learning with guest speakers and professionals,” Hauser said.

“It’s incredibly rewarding to see them grow in unexpected ways — and all of our volunteers are grateful to be part of that journey.”

Mobile

Katie Hauser/Contributed Photo

Jacob Boulter, left, and Lola Parker participated in a “Drones and Agriculture” program organized by the Baker County 4-H program on March 10, 2025.

BAKER COUNTY

Hoping for Phillips Reservoir to refill

Key source of irrigation water in Baker Valley on pace to reach highest level since 2017

BY JAYSON JACOBY | BAKER CITY HERALD

BAKER CITY — The next two months or so will determine whether the water of Phillips Reservoir climbs farther up the shoreline than it has in almost a decade.

Predicting the reservoir’s rise, though, is a task fraught with uncertainty.

“I don’t even have a clue what’s going to happen,” Jeff Colton, manager of the Baker Valley Irrigation District and the man who controls water releases from the reservoir, said on Tuesday morning, April 8.

Colton said the water supply outlook is considerably better, though, than it was during the drought that dominated from around 2018 through 2022.

During those years the reservoir along the Powder River, in Sumpter Valley about 17 miles southwest of

Baker City, never came close to reaching 73,000 acrefeet, which Colton said is considered full.

(The reservoir can store an additional 17,000 acre-feet if needed for flood control. One acre-foot of water would cover one acre of flat ground to a depth of one foot. One acre-foot equals almost 326,000 gallons.)

That meant less irrigation water for many farmers, primarily in the Baker Valley. Water from the reservoir, which was created in 1968 by the construction of Mason Dam, irrigates more than 30,000 acres.

On Tuesday morning the reservoir was holding slightly more than 40,000 acre-feet — 55% of full.

By late summer each year from 2018-22, after the irrigation season, the reservoir dropped below onequarter of its capacity.

And the subsequent winter snowpack, the main source of water to replenish the reservoir, wasn’t sufficient to

Baker Valley farmers are hoping Phillips Reservoir will come closer to full in 2025 than any year since 2017. On April 8 the reservoir was at 55% of capacity. — Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald

refill such a severely depleted body of water.

The drought began to ease in early 2023.

The reservoir was nearly empty, with a little more than 5,000 acre-feet of water, at the start of April 2023.

But the combination of an above-average snowpack in the upper Powder River basin, and a stretch of warm weather in early May that rapidly melted the snow, pushed a glut of water into the reservoir that continued for weeks.

From early April to early June 2023, the reservoir rose by about 46,000 acre-feet. It peaked, on June 16, 2023, at 53,600 acre-feet, the most since early August 2017.

(2017 was also the last time the reservoir filled.)

The next spring, 2024, was quite different.

The reservoir held much more water than a year earlier — about 42,000 acre-feet in early April, compared with 5,000 the previous year.

But the snowpack wasn’t as deep — about 40%

less than in 2023 — and the runoff was comparatively scant.

The reservoir added just 11,000 acre-feet during April and May.

Its peak, reached in mid-May rather than mid-June, was almost exactly the same, at 53,400 acre-feet.

The current snowpack occupies a middle ground between the previous two years.

As of April 8, the water content in the snow at an automated station near Bourne was 17.8 inches. That’s more than the 12.8 inches on that date in 2024, but less than the 21.3 inches on the date in 2023.

The problem, Colton said, is that the snowpack, although a useful barometer for estimating runoff into the reservoir, is hardly a definitive one.

The amount of water that flows into Phillips can vary dramatically from one year to another, even when the snowpacks are similar, he said.

Other factors that are more difficult to measure, such as how much of the melting snow soaks into the ground rather than flowing directly into streams, can have a major effect on the reservoir level, Colton said.

Another vital matter is when downstream farmers with rights to water stored in the

Expert Auto, Truck and Motor Home Repair

reservoir start to ask for the water — and how much they need.

During a warm, dry spring, the demand for irrigation water can swell as early as April.

But if the season is cool and damp, Colton might be able to store most of the water flowing into the reservoir, holding it until the heat of summer.

The complications continue, though.

The same weather pattern that delays irrigation and keeps water in the reservoir also stifles the rate of snowmelt, preventing the torrent of inflow — as in the spring of 2023 — that can rapidly replenish the reservoir.

Mark Ward has seen all those factors affect the reservoir over the decades.

His family uses reservoir water to irrigate crops in the Baker Valley. He’s also a member of the board of directors for the Baker Valley Irrigation District.

Ward said on Tuesday, April 8, that he doesn’t expect the reservoir to rise above about 55,000 acre-feet this year. That would be the most since August 2017, slightly above the peaks of 2023 and 2024, but still only about 75% of full.

Ward said he would appreciate another major rainstorm.

Honest, Reliable Service