THE RACIALIZATION OF CLASS IN MEXICO THROUGH XALAPA'S HOUSING CASE STUDY

Escarleth Cucurachi Ortega

UP 434 Race in the City

Instructor: Dr. Deyanira Nevarez Martinez

Master of Urban and Regional Planning

Michigan State University May 2023

Escarleth Cucurachi Ortega

UP 434 Race in the City

Instructor: Dr. Deyanira Nevarez Martinez

Master of Urban and Regional Planning

Michigan State University May 2023

1. INTRODUCTION

2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Colonization and Racial Stratification in Latin America

2.2 Mestizaje and Racism in Mexico

2.3 Post-racism in Mexico

3. POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

3.1 Inequality of Socioeconomic Opportunities

3.2 Housing Framework In Mexico

4. CASE STUDY: XALAPA CITY

4.1 Housing Typologies in Xalapa

4.2 Housing Framework in Xalapa

5. CONCLUSION

6. REFERENCES

Racialization

In recent years, discussions surrounding racism and discrimination in Mexico have become more prominent. While many have held onto the belief that Mexico is a country free of racism, this overlooks the impact of colonization on Indigenous populations and the imposition of European culture, language, and religion. The consequences of this social inequality are still felt in Latin America today, and it is vital to acknowledge and address these issues.

On top of that, the mestizaje movement, which aimed to fuse the Indigenous and Spanish veins of the population in Mexico to create a single national culture and race, perpetuated existing social hierarchies and rendered Afro-descendants and Indigenous people invisible. Moreover, the post-revolutionary Mexican State established an assimilationist model towards Indigenous peoples that stripped them of their individuality and ignored the historic robbery of their lands and culture. As a result, discrimination against Indigenous people and Afro-descendants is still the main problem reported by these communities, despite the multiculturalism that was supposed to address these issues.

Furthermore, the effects of skin tone and ethnicity on social inequality are well documented, and research shows that socioeconomic differences by skin color are partly explained by the effect of historically accumulated disadvantages due to racial discrimination from previous generations. Discrimination limits access to certain types of jobs and opportunities for career advancement, perpetuating socioeconomic inequality and hindering economic development.

In addition, the severe housing crisis that Mexico faces affects the most vulnerable populations. Hence, it is imperative to approach the housing crisis from a social justice perspective that takes into account the historical discrimination that has played a role in the marginalization of ethnic minorities.

Overall, it is clear that Mexico needs to take significant steps to address the impact of colonization and historical discrimination on Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations, as well as address current issues, such as the housing crisis that is directly related to those marginalized groups. This paper will explore these issues, seeking to address the correlation between class, race, and housing opportunities in the country.

“There is no racism in Mexico, we are all mestizos.”

The colonization of the Americas was a significant event that profoundly impacted the indigenous populations. The arrival of Europeans to the Americas resulted in the displacement and subjugation of the Native American peoples, who had inhabited the continent for thousands of years. In addition, the European colonizers imposed their ideologies, cultures, and religions on the indigenous populations.

One of the most significant impacts of colonization on Native American populations was the loss of their lands. The Europeans claimed the land as their own, disregarding the fact that the indigenous peoples had already occupied it. As a result, the land was taken away from the Native Americans, who were forced to move to other areas or were killed. This led to the destruction of Native American communities and cultures, as their connection to the land was severed (La Colonia o el Virreinato en México (1521-1810), n.d.).

The European colonizers also imposed their culture and religion on the indigenous populations. They considered the Native American culture to be inferior to their own, and as a result, they attempted to erase it (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2014, p. 6). Accordingly, the indigenous people were forced to adopt European languages, religions, and customs, resulting in the loss of their identities (La Colonia o el Virreinato en México (1521-1810), n.d.)

Moreover, the Europeans brought with them the ideology of social inequality based on physical characteristics and the caste system. They believed that people could be categorized by their physical appearance and be judged according to their intelligence. This ideology resulted in the construction of rights and privileges based on physical characteristics. The social stratification system that was implemented during the colonial period was designed to benefit the Spaniards and their descendants, who occupied the top of the caste hierarchy. The Indigenous and African groups were impoverished and were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, without any rights or privileges (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2014, pp. 6-7).

The consequences of the social inequality imposed by the Europeans on the Native American populations were severe. The loss of their lands, identities, and culture resulted in the impoverishment of the indigenous populations, who were the poorest, the most prone to diseases, and without any rights. Furthermore, the colonial period resulted in the construction of a social hierarchy that still has an impact on Latin America today.

The idea of mestizaje as a solution to racial inequality in Mexico has had significant repercussions for future generations, particularly for Afro-descendants and indigenous people. Vicente Guerrero, an Afro-descendant who became the second president of Mexico, believed that social inequality would cease to exist if people were no longer categorized based on race

(Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2014, p. 8). This assumption led to the emergence of the mestizaje movement, which sought to fuse the indigenous and Spanish veins of the population to create a single race and a single national culture, the mestizo (Gall, 2021, p. 57).

However, the implementation of this ideology rendered Afro-descendants and indigenous people invisible throughout Latin America, with minimal changes to social stratification. This was because the mestizo identity ideal was built on the notion that the indigenous and Spanish veins of the population were the only two bloodlines and cultures that mattered in the creation of the Mexican identity. This belief system opposed the European model, which used race to articulate belonging to the nation and establish its borders (Gall, 2021, pp. 57-59).

The Mexican elites sought to address this dilemma by promoting mestizaje as the embodiment of the ideal characteristics of nationality. However, this solution had its problems. European immigration was encouraged, particularly to areas with high concentrations of indigenous and African people, and white prostitutes were sent to areas where there was a high concentration of Afro-descendants to "better the race," according to Chavez-Dueñas et al. (2014, p. 9).

Furthermore, Gall (2021, pp. 59-60) describes how two alternative and incompatible accounts of ethnic nation coexisted, which led to a cultural murder of indigenous peoples. The first account considered the essence of the Mexican race as rooted in the original peoples, who had been hit by the conquest but had been reborn from their ashes with independence. The second account considered the essence of the "Mexican race" to be the Creoles, the product of colonization, emancipated from their tyrannical parents and who had forged their autonomous identity for centuries, reaching their identity maturity with independence.

The post-revolutionary Mexican State established an assimilationist model toward indigenous peoples, which Mexican critical anthropology denounced in the 1970s as ethnically discriminatory (Gall, 2021, p. 61). The indigenous peoples were stripped of their individuality to classify them in a class of uniformity, which embodied tacit racism under the shelter of the process of "mestizaje." The indigenous peoples thus acquired the same rights as the Creole population but lost recognition of the historic theft of their lands and the trespassing of their culture and roots.

Despite the relative "refuge" that mestizaje provided to give a kind of equality to all groups, no work was done to balance the privileges that the caste system had granted whites and Europeans for years. No matter that everyone was called mestizo, whites continued to have the economic benefits and privileges of a social status that never faded. On the other hand, indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples were pigeonholed into the same stereotype but without any recognition of the historical theft of their identity and lands.

Consequently, the mestizaje movement, while well-intentioned, did not achieve its goal of eradicating social inequality in Mexico. Instead, it rendered Afro-descendants and indigenous people invisible and perpetuated existing social hierarchies. The idea of a single national culture and race excluded and marginalized groups that did not fit within that framework. The postrevolutionary Mexican State's assimilationist model towards indigenous peoples further entrenched discrimination and ignored the historic theft of their lands and culture.

Mexico has been a society that, for almost the entirety of the 20th century, demonstrated a consensus, whether implicit or explicit, that mestizo Mexico was not a racist society, including its institutions and intellectuals. Nonetheless, the emergence of the Zapatista movement gave rise to new voices that criticized the mestizo movement and its racist character in Mexican society and the State. The central message of the mestizo project was that a country that takes pride in its mixed blood and cultures could not be labeled racist. However, the Zapatista movement challenged this idea, and a large percentage of Mexican society had already embraced it (Gall, 2021, pp. 61-62).

The fact that discrimination is the main problem reported by the indigenous community in Mexico reveals the severity of the issue (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2014, p. 9). The exclusion of indigenous people and Afro-descendants from the mestizo project has prevented them from commenting on its nature, which is not only unjust but also perpetuates racism. Multiculturalism, which was supposed to break with historical racism against peoples and communities already formally recognized as ethnically different and as subjects of collective rights, has not been able to do so entirely (Gall, 2021, p. 63)

Racism in Mexico is hidden behind a discourse that resorts to tactics to keep the population alienated from fundamental problems that have not been fully resolved or recognized. In this regard, Chavez-Dueñas et al. (2014, p. 10) claim that the omission of social actors, omission of racist practices, naturalization of racism, distortion of information, and justification of racist practices are some of the strategies used to keep racism hidden in Mexico

Moreover, racial discourse is engraved in the Mexican unconscious through "dichos" or sayings, which perpetuate negative stereotypes about indigenous people and Afro-descendants. Some of which Chavez-Dueñas et al. point out:

▪ “Hay que mejorar la raza o cásate con un blanco [We need to better the race by marrying a White individual].”

▪ “¡Ahi que bonita es su niña, es tan güerita/blanquita! [Oh! How pretty your daughter is, she’s so beautifully White!].”

▪ “Vete por la sombrita [Go into the shade (to avoid getting darker].”

▪ “Oh, nació negrito/ prietito pero aun asi lo queremos [Oh, he was born Black/dark but we still love him all the same].”

▪ “Pobrecita, tiene el cabello tan malo [Poor little thing, her hair is so bad (coarse)].”

▪ “Eres tan Indio [You are so Indian (connoting negative stereotypes about indigenous people)]” (2014, p.17).

To which could be added:

▪ “Trabajo como negro para vivir como blanco” [I work like a black person to live like a white person, referring to slavery and white privileges]

▪ “Soy de color humilde” [I am of humble color, referring to the fact that mostly brown or black people are poor]

Mexicans seek to minimize their problems by explicitly denying racism; however, they continue to victimize their situation of poverty or divert attention from the fundamental problem with other justifications (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2014, p. 18). It is essential to recognize the history and contributions of Afro-Latinos and indigenous people and acknowledge the existence of racist practices. Mexico must avoid normalizing racism and discrimination as natural phenomena that occur as a result of how a society develops. The elevation to the character of the law of respect for the history, reasons, territory, cultural and legal institutions of indigenous peoples, and their right to autonomy and self-determination is a significant step towards acknowledging and rectifying the problem.

“Trabajo como negro para vivir como blanco.”

The Political Constitution of the United Mexican States is a legal document that has recognized and guaranteed a broad spectrum of civic, political, and social rights to the Mexican population. Conversely, while the Constitution states that people shall enjoy the human rights recognized in it and international treaties, there is a significant gap between the legal recognition of socioeconomic rights and their actual implementation (Damián, 2019, pp. 627-628).

The expansion of social rights recognized in the Constitution began in 1974 with the reform to Article 4. This expansion was intended to provide citizens with access to decent housing, among other rights. However, legally recognized socioeconomic rights lack precise mechanisms for their implementation, and secondary laws have not been approved for some of them. This lack of implementation has resulted in the intentional and systematic violation of social rights, including by the government (Damián, 2019, pp. 627-629)

The violation of social rights is not limited to socioeconomic factors; it is also deeply rooted in racism and ethnic discrimination. For a long time, Mexicans believed that their society was not racist, and the social disadvantage of indigenous peoples was attributed to a lack of socioeconomic development, geographic isolation, or "cultural backwardness." Nonetheless, in reality, social inequality is reproduced through systematic deprivations imposed on ethnic-racial minorities (Solís & Güémez, 2021, p. 256).

The effects of skin tone and ethnicity on social inequality are well documented, and research shows that socioeconomic differences by skin color are partly explained by the effect of historically accumulated disadvantages due to racial discrimination from previous generations (Solís & Güémez, 2021, p. 259). Moreover, the situation of the social disadvantage of indigenous peoples and Afrodescendant populations is evident, as they represent the two poorest groups of Mexicans in the country, according to recent surveys (Gall, 2021, p. 54).

This situation of social inequality is not new; it has deep colonial roots that have reigned in Mexico since its creation as a modern nation-state. The effects of this colonial legacy are still felt today, and they deepen inequalities and justify them. In addition, it creates a situation where some have, by their nature and culture, the right to better living conditions than others (Gall, 2021, p. 56)

In this regard, the findings from the 2016 study carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), called the Intergenerational Social Mobility Module (MMSI), suggest that there may be some form of discrimination or bias based on skin color in the job market. The study measured the socioeconomic differences and professional opportunities according to the phenotypic skin traits of the population. The results showed that the population with darker skin tones had a higher propensity to work in blue-collar jobs, while those with lighter skin tones had a higher propensity to work in white-collar jobs (see Graph 1 below).

Likewise, Solís & Güémez's (2021, pp. 279-281) research findings support the idea that ethnicracial and socioeconomic circumstances are interrelated due to the accumulation of socioeconomic disadvantages associated with racism and ethnic-racial discrimination in previous generations. Their study found a statistically significant association between skin color, ethnicracial characteristics, and economic assets. Moreover, they observed that individuals with ethnicracial characteristics related to indigenous peoples or Afro-Mexicans are more likely to come from families with a lower socioeconomic status.

In addition, these findings suggest that discrimination based on skin color is not only unfair but also has severe consequences for individuals and society as a whole. For example, discrimination limits access to certain types of jobs and opportunities for career advancement, which can perpetuate socioeconomic inequality and hinder economic development. It also undermines social cohesion and perpetuates social divisions, which can lead to conflict and unrest.

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the existence of racism in Mexico (Gall, 2021, p. 57) Nonetheless, this awareness is relatively recent, and it is essential to continue to educate the population and create policies that address racism and ethnic discrimination. The situation of social inequality in Mexico is complex and multifaceted, but recognizing and addressing the role of racism and ethnic discrimination is an essential step toward creating a more conscious population of its racist historical framework and its repercussion in current lives.

Furthermore, the recognition of social rights in the Constitution is an essential step toward creating a more equal and just society. Nevertheless, it is not enough to merely recognize these rights; it is also necessary to implement them effectively. This requires clear mechanisms for their implementation and an active commitment to their realization. It also requires a recognition of the deeply ingrained racism and ethnic discrimination that underlies social inequality in Mexico.

The University Program of Studies on the City (PUEC) of the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) presented in 2021 the following relevant points on housing conditions in Mexico in accordance with the provisions of UN-Habitat:

1. According to estimates, 38.4% of homes in the country are in inadequate conditions, which affects vulnerable populations such as lower-income households, informal workers, women, indigenous people, youth, and displaced persons.

2. The country has 12.6 million homes in a deteriorated state.

3. Approximately 37.5% of houses built and financed by ONAVIS between 2011 and 2014 are uninhabited and located in the urban peripheries.

4. Half of the houses built in the last 20 years are concentrated in only eight states in the country, which are Baja California, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, Jalisco, Guanajuato, Estado de México, and CDMX.

5. The housing financing policy is focused on providing support to individuals with formal employment and sufficient income to obtain a loan.

6. Households with the lowest income would require 33 years to pay for an affordable house with a subsidy, 47 years without a subsidy, and 120 years for an average house.

7. Over 87.7 million Mexicans live in high-risk areas due to natural and climatic phenomena.

8. Between 2000 and 2017, disasters related to natural and climatic events caused damage to over 1.4 million homes, with 82.6% of the damages related to climate change and 17.4% due to natural disasters. (Onu-Hábitat, 2019)

Mexico is facing an acute housing crisis that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations such as lower-income households, informal workers, women, indigenous people, youth, and displaced persons. The estimates indicate that 38.4% of homes in the country are in inadequate conditions, and households with the lowest income face significant challenges in accessing affordable housing. Further, the current housing financing policy is focused on individuals with formal employment and sufficient income to obtain a loan, which excludes those most in need of support to improve their housing situation. Consequently, households with the lowest income would require up to 120 years to pay for an average house, highlighting the enormous financial burden that housing places on vulnerable populations.

Similarly, with this data is clearly drawn the relationship between the poorest living conditions of low-income households and their ethnicity highlights the pervasive impact of historical racism in Mexico. Ethnic minorities, including indigenous people, often face discrimination and exclusion from mainstream society. This marginalization affects their access to resources, including safe and affordable housing. As a result, many indigenous people are forced to live in inadequate conditions, with little access to basic services and infrastructure.

Moreover, the lack of access to affordable and safe housing perpetuates the cycle of poverty and marginalization among ethnic minorities. It limits their ability to participate fully in society and hinders their economic and social progress. Therefore, the housing crisis in Mexico must be viewed through a lens of social justice that considers the historical injustices that have contributed to the marginalization of ethnic minorities.

“That is how things are.”

Xalapa is the capital of the state of Veracruz in Mexico. It is located in the physical center of the territory and has a population of 488,531 inhabitants, according to the INEGI 2020 Census. This city has a very severe topography, especially on the periphery of the urban sprawl where hollows can be found, which causes a high risk of landslides.

According to the INEGI 2020 Census, Xalapa has approximately 195,268 homes. These homes are categorized into five typologies according to the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021:

The first typology, Precarious, represents 6.24% of the total housing and represents social groups with lower income. These houses are built with perishable materials on walls and/or roofs and are located on the periphery of properties with vulnerable and risky conditions. Most do not have access to municipal services, which can have negative impacts on health and well-being (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149).

Populated by low to medium-income groups, the second typology, known as Popular, accounts for 52.60% of the total housing. These houses are built with permanent materials, and the surface area of the properties varies depending on the type of dwelling. In addition, they have basic services, which means that access to water, sanitation, and electricity is limited (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149). While these houses offer better living conditions than the Precarious typology, they still face challenges related to access to basic services, infrastructure, and public spaces. Moreover, the high percentage of this typology in Xalapa reflects the significant income inequality present in the city, which limits the ability of low- and middle-income households to access quality housing and secure land tenure.

Additionally, the Social Interest typology, comprising 5.71% of the total housing, is distinguished by its occupants who have a fixed salary and are beneficiaries of loans like FOVISSSTE, INFONAVIT, and other similar programs. It is considered institutional and complies with official housing regulations. This typology represents an effort by the government to address the housing deficit in Xalapa by providing affordable housing options for formal workers with stable incomes (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149). Nonetheless, the limited percentage of this typology shows that there is still a significant gap in the provision of affordable housing in the city, particularly for the most vulnerable populations.

On the other hand, the housing type referred to as Medium, accounting for 26.48% of the total housing, is typical of social groups with moderate economic income. These houses have a minimum area of 160 m2 and are built with permanent materials and quality finishes. They have all the services and are located in subdivisions in some regions of the city or coexistence with other types of housing (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149). This typology represents a significant improvement in housing quality and access to basic services compared to Precarious and Popular typologies. However, the limited percentage of this typology highlights the substantial

income inequality present in the city and the limited ability of middle-income households to access quality housing.

The last typology, Residential, accounts for 8.99% of the total housing and is defined as dwellings with a minimum construction area of 200 m2 . These houses have a large construction surface with high-quality finishes and belong to the high socioeconomic group. They are located within residential subdivisions and have all the services provided through specialized infrastructure (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149). This typology reflects the most significant disparity in housing quality and access to basic services, highlighting the significant differences between economic groups and access to a better quality of life.

Hence, these typologies present a clear picture of the socioeconomic disparities that exist within the city, with the majority of the housing falling under the Popular typology. The typologies also highlight the different services and quality of housing available to different socioeconomic groups. Furthermore, the concentration of "Precarious" and "Popular" housing in the periphery of the city, coupled with its topographical challenges, underscores the need for urgent action to provide safe and secure housing to the most vulnerable populations.

Like many cities in Mexico, Xalapa is a city of contrast, where the divide between the highincome and low-income populations is evident. The low-income population is concentrated in the peripheries of the city, where they face poor services, physical hazards, and a lack of accessible facilities. This project's data shows that the peripheries of Xalapa are the areas with the lowest percentage of public services, including electricity, water, and drainage services.

The city's spatial distribution of housing typologies can reveal stark inequalities between low and high-income populations (see Map I below). For example, the location of the Precarious and Popular typologies, typically occupied by lower-income households, is mainly in the city’ s periphery, in areas with poor infrastructure and public services. Meanwhile, the Residential typologies, which are associated with higher-income households, are concentrated in the eastsouth of the city, where there is better access to quality services and security. In addition, the Medium typologies are situated in the center of the city, which is the historical urban zone and the urban planning area of the 80s (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149-153)

This distribution of housing typologies can be interpreted as a reflection of the socioeconomic disparities that exist within the city. The periphery is generally neglected and lacks investment, leading to a concentration of precarious housing and an underserved population. Conversely, the city center and areas inhabited by higher-income households enjoy better infrastructure, services, and security. This inequality of access to resources and opportunities can further perpetuate socio-economic disparities between different groups within the city.

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

One major challenge facing Xalapa's low-income populations is the lack of access to essential services. The city’s peripheries have the highest percentage of homes that do not have access to electricity, water, and drainage services (see Maps 2, 3, and 4, respectively below). This situation has severe consequences for the residents, including the lack of sanitation and hygiene, which can spread diseases. The absence of these services also poses a significant risk to public health, as access to clean water is critical to preventing the spread of water-borne diseases.

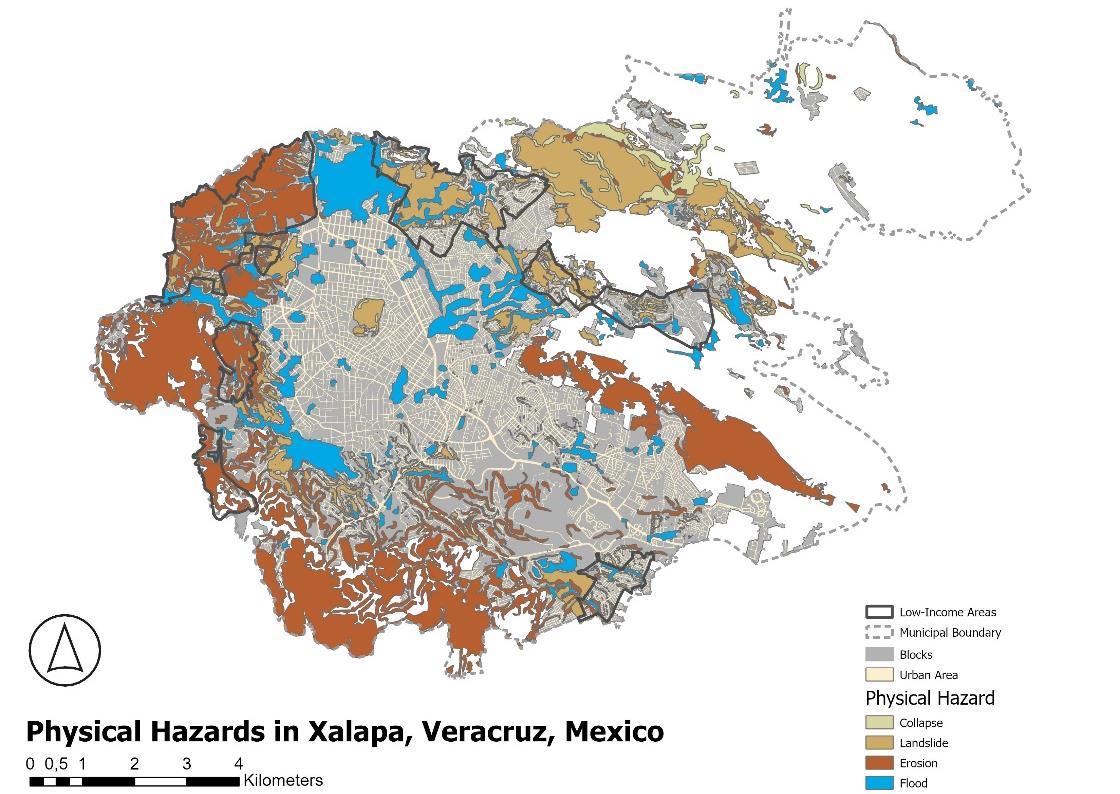

Moreover, physical hazards such as landslides, floods, and other natural disasters pose a severe threat to residents of the peripheries of Xalapa. Almost all the territory of these areas is covered with physical threats, making them the most dangerous areas in the city (see Map 5 below). Unfortunately, in 2021, ten people died due to a landslide in the riskiest area of the periphery (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149-153).

In addition, the street network in Xalapa has a concentration of paved roads in the central and southern parts of the city. A significant portion of these roads are cobblestone, reflecting the city's colonial heritage. In contrast, low-income areas in the periphery of the city have a high percentage of dirt roads (70%), making it challenging for public transportation and other essential services to reach these neighborhoods. The lack of proper infrastructure in these areas exacerbates social and economic inequalities (see Map 6 below).

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

Source: Prepared by the author on the basis of data supplied by the Municipal Program of Territorial Planning of Xalapa, Veracruz, 2021.

Furthermore, the physical features of the peripheries of Xalapa present significant challenges for low-income populations. For example, these populations do not have property documents, making it difficult for them to relocate to other city sectors. Additionally, the lack of accessible facilities, combined with the substandard quality of public transportation and roads in these areas, makes it difficult for residents to access the services they need (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149-153).

The government's inability to offer public services to these sectors due to the cost of extending the lines of services aggravates the situation (Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz, 2021, p. 149-153) This lack of investment in public services creates a cycle of poverty, where low-income populations are unable to access the resources and opportunities they need to improve their situation.

The situation in Xalapa is not unique. Most of the cities in Mexico face similar challenges, where the high-income population lives in the best sectors of the city, leaving the low-income population to settle in the most dangerous areas. The segregation of low-income populations has severe consequences for public health and social equality.

The case study of the city of Xalapa highlights the stark inequality that exists between different socioeconomic groups in Mexico. It is evident that people with higher incomes have better access to services, security, and a better quality of life, while the most vulnerable groups are left without opportunities to improve their situation. This inequality is perpetuated by the real estate framework in Mexico, which requires a formal income and economic wealth to obtain a mortgage loan. This leaves lower-income groups without opportunities to access decent and affordable housing, as recognized by the Mexican Constitution.

Furthermore, lower-income groups are disadvantaged due to the systemic racism that has historically existed in Mexico and has not been recognized. People of different races carry historical disadvantages, which the system perpetuates by privileging white people and leaving ethnic populations at the bottom of the hierarchy. Accordingly, the children of these generations are born with tacit disadvantages, most likely being from a lower socioeconomic class with lower incomes and more significant struggles to gain access to higher education, a well-paid job, or a suitable home.

Likewise, the relationship between race and socioeconomic privilege is reflected in the type of house or living conditions to which individuals can access. For example, indigenous ethnic groups, Afro-descendants, or people who identify with a darker complexion are more likely to belong to the lowest-income socioeconomic group in the country. This subsequently impacts the conditions of their homes, which are closer to a Precarious or Popular typology.

It is essential to recognize that systemic racism and socioeconomic inequality are intertwined, and addressing one requires addressing the other. Therefore, Mexico must acknowledge and attend to the historical injustices that have perpetuated this inequality and take steps to create policies that allow lower-income groups to access decent and affordable housing, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

The lack of access to decent and affordable housing for lower-income groups is not only a violation of their human rights, as recognized by the Mexican Constitution but also perpetuates a cycle of poverty. In addition, without adequate housing, individuals are more likely to struggle with their health, education, and employment opportunities. This impacts not only their lives but also the broader economy and society as a whole.

Mexico must take steps to dismantle the structures that perpetuate inequality, such as systemic racism and the real estate framework that excludes lower-income groups from accessing decent and affordable housing. This requires a fundamental shift in societal attitudes toward race and a commitment to creating policies that address the root causes of inequality.

In summary, the case study of Xalapa highlights the urgent need for Mexico to address the significant inequalities that exist between different socioeconomic groups and accept and tackle systemic racism. The lack of access to decent and affordable housing for lower-income groups perpetuates a cycle of poverty and violates their human rights. Addressing systemic racism and creating policies that allow lower-income groups to access decent and affordable housing, regardless of race or ethnicity, is essential to improve their quality of life and discourse historical injustices.

Chavez-Dueñas, N., Adames, H., & Organista, K. (2014). Skin-Color Prejudice and WithinGroup Racial Discrimination: Historical and Current Impact on Latino/a Populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 36(1), 3-26. doi:10.1177/0739986313511306

Damián, A. (2019). Pobreza y desigualdad en México. EL TRIMESTRE ECONÓMICO, LXXXVI (3), 623-666. doi:10.20430/ete.v86i343.920

Gall, O. (2021). Mestizaje y racismo. Nueva Sociedad, 53-64.

Gobiero del Estado de Veracruz. (2021). Vivienda: inventario y demanda. En Programa Municipal de Ordenamiento Territorial de Xalapa, Ver. (Vol. I, págs. 149-153). Xalapa: Gaceta Oficial del Estado de Veracruz.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2016). Módulo de Movilidad Social Intergeneracional 2016, Principales resultados y bases metodológicas. INEGI. Obtenido de chromeextension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/m msi/2016/doc/principales_resultados_mmsi_2016.pdf

La Colonia o el Virreinato en México (1521-1810). (s.f.). Obtenido de Mexico Desconocido: https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/el-virreinato-o-epoca-colonial-1521-18101.html

Onu-Hábitat. (April de 2019). ONU HABITAT. Obtenido de La vivienda en el centro de los ODS en México: https://onuhabitat.org.mx/index.php/la-vivienda-en-el-centro-de-los-ods-enmexico#:~:text=ONU%2DHabitat%20estima%20que%20al,mejorados%20de%20agua%20y%20sa neamiento.

Solís, P., & Güémez, B. (2021). Características étnico-raciales y desigualdad. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 36, 255-289. Obtenido de http://dx.doi.org/10.24201/edu.v36i1.2078

The Racialization of Class in Mexico through Xalapa's Housing Case Study