The European Security and Defence Union

Europe and Space

Benefits for mankind versus growing geopolitical competition

Benefits for mankind versus growing geopolitical competition

From the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea, GA-ASI is a proud provider of advanced ISR capabilities for NATO’s most challenging requirements. Our proven multi-mission MQ-9B remotely piloted aircraft stands apart in capability and is ready now to deliver the interoperability, configurability, and versatility needed for unmatched situational awareness.

by Hartmut Bühl, Editor-in-Chief, Paris

Long before the start of Putin’s war against Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Russian preparations for a military offensive were revealed by observation satellites of various nations. Even though the world was provided with information on Putin’s military intentions and Russia’s operational readiness to attack Ukraine, European leaders decided to pursue a policy of appeasement, trying to save peace through diplomacy.

However, many things have changed since then, not least in space policy. Until recently, most of the treaties and agreements of the European Union (EU) and its Member States – from the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 to the 2021 Regulation for a new Space Programme (2021-2027) – referred essentially to the societal and economic dimensions of space.

Civilian space technologies and services have indeed become essential to our daily lives for communication and navigation. Satellites also provide immediate information about disasters, help secure transportation and energy infrastructure and are a valuable tool in the field of climate research. For many years however, defence and military applications were deliberately excluded from the EU’s space policy.

Only in 2022, with the Strategic Compass, did Brussels acknowledge that space-based systems are crucial for military engagement on earth and sea and advocated the coordinated protection of vulnerable systems by the western community. However, even in space, security and defence remain national prerogatives where it is difficult to reach consensus.

Against the background of the current geopolitical context of increasing power competition and threat intensification, the first ever EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence of March 2023 is a welcome move. The new strategy proposes action to protect European space assets, defend the EU’s interests, deter hostile activities in space and strengthen the Union’s strategic posture and autonomy.

Hartmut Bühl

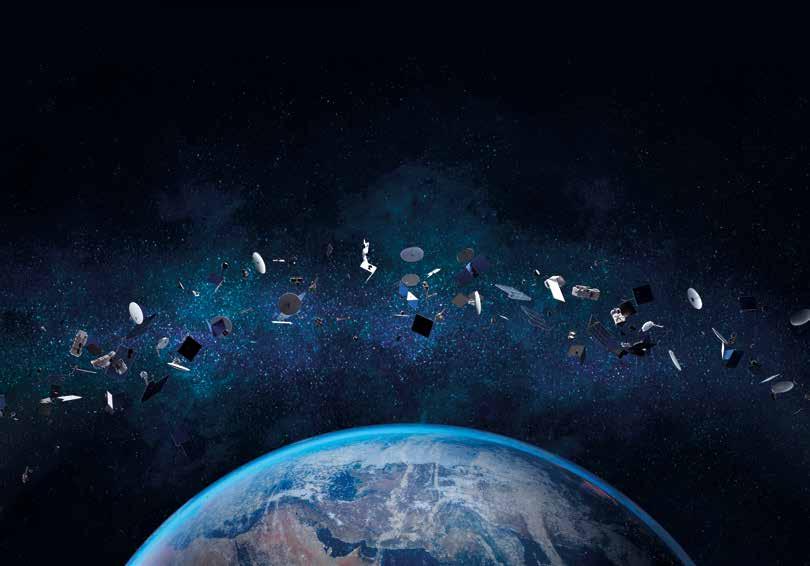

These are essential measures for our future, in view of the serious challenges in outer space. Russia and China have carried out successful tests to prove that they can use anti-satellite systems to shoot down any satellite in space. More nations, including rogue states, are striving to develop space capabilities or divert civilian assets for military use. Furthermore, the fast-growing amount of space debris is an increasing threat to vulnerable high-tech space systems.

Alas, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which contains broad principles to guide the activities of nations in space, does not contain detailed rules for the use of space. While the treaty specifically prohibits weapons of mass destruction anywhere in space, it does not prohibit the use of conventional weapons or the use of ground-based weapons against space assets. There is therefore an urgent need for updated common rules governing safe, peaceful and sustainable activities in outer space.

Europe has a number of important assets to pursue a successful space policy, with its highly valuable space systems like Galileo, Egnos and Copernicus. It also uses excellent dual-use systems in its Space Surveillance and Tracking System (SST) as part of the EU’s Space Situational Awareness Initiative (SSA). In addition, individual EU Member States have many other capabilities to meet current challenges.

Today, it is essential to further bundle these capabilities into a joint and coordinated approach at all levels to underpin Europe’s strong role in space and guarantee its security.

Hartmut Bühl

The role of space in ensuring the European Union’s security

Timo Pesonen, Brussels 18 DOCUMENTATION

The EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence

19 Who does what

Space agencies and institutions in Europe

Nannette Cazaubon, Paris 21

The potential of European space capacities

Making better use of space

Interview with Margit Mischkulnig, Vienna 24 Thinking differently

Research for Europe’s security

Prof Dr-Ing Anke Kaysser-Pyzalla, Cologne

26 DOCUMENTATION

The European Space Programme 28

The need for societal legitimisation

The public value of space exploration

Dr Stefan Selke, Furtwangen

30

Space debris and satellite protection

Governance and security in outer space

Dr Antje Nötzold, Chemnitz

32 Story from Torrejón

Europe’s eyes in the sky

Nannette Cazaubon, Paris

Which

Stefanie

35

Supporting all types of missions

ESOC – Europe’s centre of excellence for satellite operations

Hartmut Bühl, Paris 36

The need for strong space infrastructure

Western sovereignty in space matters!

Sinéad O’Sullivan, Washington D.C.

37

38

Continuing peaceful space exploration

NASA – historic and new space strategies

Hartmut Bühl, Paris

A Japanese perspective

International cooperation for space security in the age of the great power competition

Prof Hideshi Tokuchi, Tokyo

40 Unprecedented challenges in space security

The added value for Europe in space cooperation with Asian partners

Luke Hally, Brussels

42 The strive for modern space technologies

The possible use of satellite launch vehicles for the carrying of warheads

Debalina Ghoshal, Kolkata

Marketing Report

Electronic warfare in space

Dennis-P. Mercklinghaus, Munich

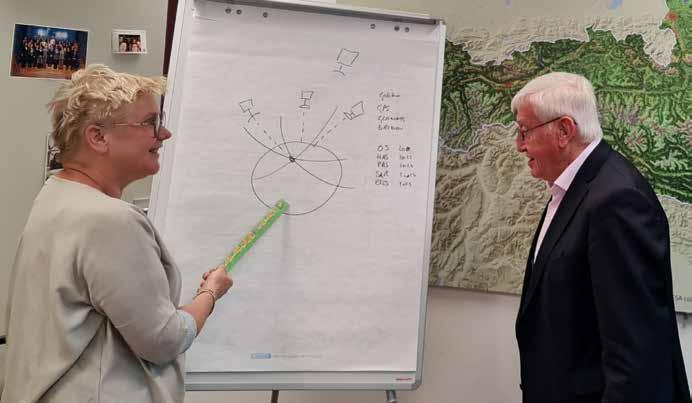

47 Field report from Austria

The future EU CBRN Reconnaissance and Surveillance System

Hartmut Bühl, Paris

49 Marketing Report

Protecting cities and people –expertise from Singapore

Interview with Chua Jin Kiat, Singapore

Masthead

THE EUROPEAN –SECURITY AND DEFENCE UNION

Volume 51 2/2024

www.magazine-the-european.com

Published by Mittler Report Verlag GmbH A company of the TAMM Media Group

Office Address: Mittler Report Verlag GmbH

Beethovenallee 21, 53173 Bonn, Germany

Phone.: +49 228 35 00 870 Fax: +49 228 35 00 871 info@mittler-report.de www.mittler-report.de

Managing Director: Peter Tamm

Editorial Team

Editor-in-Chief: Hartmut Bühl (hb)

Deputy-Editor-in-Chief: Nannette Cazaubon (nc)

Editorial Assistant: Céline Angelov

Translation: Miriam Newman-Tancredi Philip Minns

Free Correspondents: Gerhard Arnold (Middle East)

Debalina Ghoshal (India/South Asia) Ioan Mircea Pașcu (Southeast Europe) Hideshi Tokuchi (Japan/East Asia)

Copy Editor: Christian Kanig

Layout: AnKo MedienDesign GmbH, Germany

Production: Lehmann Offsetdruck und Verlag GmbH, 22848 Norderstedt, Germany

Advertising, Marketing and Business Development

Achim Abele

Phone: +49 228 25900 347 a.abele@mittler-report.de

Exhibition Management and Advertising Administration: Karin Helmerath

Advertising Accounting: Florian Bahr

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission of the publisher in Bonn.

Cover Photo: Adobe Stock / roadrunner

Reduced annual subscription rate for distribution in Germany: €95.00 incl. postage

Annual subscription rate:€ 78.00 incl. postage

(nc) In a statement on 4 June 2024, EU High Representative Josep Borrell said that the EU gives its full support to the three-phase roadmap proposal from Israel to Palestinian Islamist group Hamas to end the war in Gaza. The roadmap for a ceasefire, the release of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners, and the reconstruction of Gaza was announced by US President Joe Biden on 1 June. The EU High Representative stated that “the EU appreciates the determined efforts by the US, Egypt and Qatar in facilitating negotiations to bring an end to the war between Israel and Hamas, while ensuring Israel’s security, to which the EU remains fully committed”. Borrell further underlined that the EU urges both parties to accept and fulfil the three-phase proposal and “stands ready to contribute to reviving a political process for a lasting and sustainable peace, based on the two state solution, and to support a coordinated international effort to rebuild Gaza”.

➭ See the article by our Middle East correspondent on Page 12-13

Ukraine

Turnaround in the Ukraine war

(hb) Russia’s attack on the Kharkiv region finally caused a change of mind in western states regarding strikes against Russian territory with the weapon systems they deliver to Ukraine. In early June 2024, the United States and other NATO allies, including Germany, allowed Ukraine to use these weapons for limited strikes on Russia’s soil in order to prevent a possible concentration of Russian troops for a larger offensive in border areas. Until then, NATO states had agreed to supply weapons systems and ammunition to Ukraine only for the defence of Ukrainian territory against the Russian aggressor. US President Joe Biden feared escalation and repeatedly warned of a third world war, and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz clearly rejected the delivery of Taurus cruise missiles to Ukraine because they could hit Moscow. In response to the recent permit, Putin warned that he could arm western opponents around the world. This did not impress French President Emmanuel Macron: on 7 June 2024, in the presence of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Macron announced the possibility of sending French military trainers to Ukrainian soil and of providing Mirage 2000-5 fighter jets to the country.

(nc) The latest Eurobarometer survey is out, reflecting the opinion and expectations of EU citizens ahead of the European elections. Released on 23 May 2024, the survey shows that 77% of Europeans are in favour of a common defence and security policy among EU countries while over seven out of ten EU citizens (71%) agree that the EU needs to reinforce its industrial capacity to produce military equipment. In the medium term, Europeans consider that security and defence (34%) is the priority area for EU action, followed closely by climate and the environment (30%). Health (26%) comes third, economy and migration fourth (both 25%). Among the most recent crises, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has had the greatest influence on EU citizens’ vision of the future (42%), followed by the pandemic and other health crises (34%) and the economic and financial crisis (23%).

https://bit.ly/3VJ94N3

(nc) In April 2024, the Robert Schuman Foundation published the 18th edition of its “Report on Europe, the State of the Union”, edited by Pascale Joannin. This excellent book brings together key figures from politics, including the French President, the President of the European Commission and the President of the European Parliament, and gives the floor to people from the worlds of business, research and diplomacy. Their view on the European Union is completed with original maps and commented statistical data, which make the publication a vital tool to understand the multi-dimensional challenges facing contemporary Europe. The report can be purchased in French and English via the foundation's website. https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/bookshop

(hb) On 9 May 2024, German Federal Defence Minister Boris Pistorius, invited by the American-German Institute and the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, held a speech in Washington where he stated that “this year, Germany will spend more on defence than ever before in the history of the Bundeswehr”. He added: “I am working hard to ensure that our spending and our investments will continue to rise. Two percent are our floor, not our ceiling.” Pistorius further stated that work is ongoing to prepare the Bundeswehr for today’s challenges and expressed his conviction that Germany, which suspended the obligatory military service in 2011, “needs some kind of military conscription. We need to ensure our military staying power in a state of national or collective defence.” While this topic remains politically sensitive in Germany, in other NATO nations an increased emphasis on conscription as a key part of the military’s toolbox can be observed.

Pistorius’ speech: https://bit.ly/3yPVY7n

(hb) On 4-5 June 2024, the 8th edition of the European Civil Protection Forum took place in Brussels with about 1,500 participants under the theme “Shaping a disaster-resilient Union: charting a path for the future of European civil protection”. The excellently organised event brought together experts, policy makers, first responders, scientists and the private sector, who discussed the latest evaluation (adopted on 29 May 2024) on the Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM). The evaluation, presented at the Forum by Commissioner for Crisis Management Janez Lenarčič shows that a more coordinated response across different sectors and levels will be needed in the face of the increasing number and severity of complex emergencies. While the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) and rescEU – the EU's own reserve of equipment and supplies to respond to disasters – are evaluated positively, there are also concerns that the UCPM's flexibility might not be sufficient to address all new needs and developments.

https://bit.ly/3KBMQWM

(nc) On 29 May 2024, the European Union unveiled its new office dedicated to Artificial Intelligence (AI), established within the European Commission. The AI office aims at enabling the future development, deployment and use of AI to mitigate risks and foster societal and economic benefits and innovation. The office will play a key role in the implementation of the Artificial Intelligence Act, the world's first comprehensive law on AI which was provisionally agreed by co-legislators in December 2023 and should enter into force by the end of July 2024. The new office will be composed of 5 units (Excellence in AI and Robotics; AI Regulation and Compliance; AI Safety; AI Innovation and Policy Coordination; and AI for Societal Goods) and will employ more than 140 staff, including technology specialists, administrative assistants, lawyers, policy specialists, and economists, to carry out its tasks. It will be led by the Head of the AI office and will work under the guidance of a Lead Scientific Adviser and an Adviser for international affairs.

https://bit.ly/3z1XXFH

(nc) As highlights a recent study of the Vienna based European Space Policy Institute (ESPI), space has increasingly found its way into the political discourse of the European Parliament. The study explores the impact of space on political programmes and campaigns across Europe ahead of the European elections and reveals that space has seen a notable surge in interest with a 41% increase in space-related references compared to 2019 across party manifestos.

Study: https://bit.ly/3Xfc2de

➭ See our main topic on Europe and space, starting p.15

11 June 2024

by Hartmut Bühl, Paris

Europe has voted! The 720 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) have been elected for the next five years by citizens in the 27 countries of the European Union (EU) on 6-9 June 2024. While for the past five years the EU was governed by a majority composed by the centre-right European People's Party (EPP), centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and Liberals (Renew Europe), a clear shift to the right can be observed after the 2024 elections.

While the EPP, the Parliament’s largest group, sees the number of its members increased to 186, never have so many groups of the far-right-wing spectrum gained the attribution of seats, never before have so many opponents of Europe been elected to the EP. On the other side, the Greens/European Free Alliance lost seats, notably through the vote in Germany, and the liberal Renew Europe also shrunk, mainly due to the French voters: the Renaissance party of French President Emmanuel Macron only received 14.6% of votes (13 seats), which is less than half of Marine Le Pen’s right-wing extreme Rassemblement National (RN) which earned a spectacular and unprecedented 31,7% of votes (30 seats) –a result that prompted the French President to announce new legislative elections by the end of June/beginning of July 2024.

However, the European Parliament election result allows for the formation of a pro-European coalition that wants to move Europe forward. But for this, intensive discussions between the EPP, the S&D and Liberals about content is required. The Parliament, but also the Council and the future Commission, will do well to address the issues that have shaped the election campaigns in almost all Member States, such as migration, the green deal, consumer purchasing power, and the protection of European industry. Not to forget: the advancement of a realistic European defence capability and common armaments in view of the threat from Moscow and the overall tied geopolitical situation.

In autumn, the next European Commission will take over for the period 2024-2029. The nomination of the Commission President is still pending. The EPP is certain that its top candidate, the cur-

rent President Ursula von der Leyen, will be her own successor. To do so, however, the governments of all Member States first need to vote on the candidates before the European Parliament can give its voice.

The candidate for the Commission presidency should not expose him or herself to trying to get decisive votes from the right-wing extremist spectrum of the Parliament. That would be the beginning of the end of the future of the European Union!

Last update: 11 June 2024

(nc) On 25 April 2024, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg received Atlantik-Brücke’s Eric M. Warburg Award in Berlin “for his outstanding dedication to the transatlantic friendship and partnership in turbulent times”.

“ I am convinced that Ukraine will prevail because its cause is just. Democracy is stronger than autocracy. And Putin is wrong that we are not willing or able to defend our values. We are. The war in Ukraine demonstrates that security is not regional. It is global.”

The award was handed over in Berlin by German Federal Defence Minister Boris Pistorius and the laudatory remarks were held by Dr Irina Scherbakowa, co-founder of Memorial, a Russian human rights organisation awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022 for its mission to review political repressions in the former USSR and in today’s Russia.

Dr Scherbakowa said that Secretary General Stoltenberg, from the start, has understood the dangers that Russia’s aggressive behaviour against Ukraine meant for security and stability in Europe. She thanked the Secretary General, saying: “You did not have any illusions about appeasing Putin, instead you worked on building up the military strength of the alliance and urged us to prepare for the threats coming from Putin’s regime”.

Before presenting the award to the Secretary General, Minister Pistorius described him as “a man who speaks his mind and who stands up for his beliefs and values”. Referring to the situation in Ukraine, the minister expressed his belief that the situation in the country “is Europe’s most decisive and strategic issue today”.

In his acceptance speech, Jens Stoltenberg warned that in today’s Russia, “the past echoes loudly in the present. Thought is controlled, freedom is curtailed, opposition is crushed.” He added that, “as Russia has become more oppressive at home, it has become more aggressive abroad, waging a fully-fledged war in Ukraine.”

The Secretary General emphasised the need to strengthen the alliance’s deterrence and defence, increase support to Ukraine, and work with friends around the world to ensure that NATO maintains peace and prosperity for its one billion citizens. He showed confidence “that Ukraine will prevail because its cause is just. Democracy is stronger than autocracy. And Putin is wrong that we are not willing or able to defend our values. We are. The war in Ukraine demonstrates that security is not regional. It is global.”

The Atlantik-Brücke founded in 1952 is a non-profit organisation that has developed into a broad transatlantic professional network fostering cooperation between Germany, Europe, and North America, transcending sectors and party lines.

https://www.atlantik-bruecke.org/en/

by Stefanie Buzmaniuk, Senior Research Fellow and Development Manager, Robert Schuman Foundation, Paris

Although Europe provided a quick, united response to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a closer look at Franco-German strategies to stop Putin’s war over the last two years reveals major differences. The Franco-German tandem, that supposedly leads any European action in such sensitive matters, appears

dysfunctional on multiple levels. Despite the main goal –stopping the war and freeing Ukraine from Russian forces –remaining unchanged and clear, unfortunately Germany and France’s diverging approaches rarely coincide, and friction frequently emerges. Three main observations can be noted in this matter.

Firstly, it might seem paradoxical, but France and Germany both find comfort in their pre-war logic, even though essentially, they are contradictory.

France has invested heavily in a more European approach to defence. Its current President Emmanuel Macron has especially reiterated that the answer to Europe’s security and defence issues do not lie in the transatlantic alliance since the US is increasingly a partner that cannot be relied. After the start of the war in Ukraine, strengthening European defence mechanisms, joint actions, and investing in European defence industries has, for France, become ever pressing and obvious.

Germany, however, has long relied on the American security umbrella and shown attachment to its US partner in defence issues. The European scale has not been a priority for Germany – not even investments in its own defence – since only NATO seemed capable of defending Germany, and Europe as a whole. After Russia’s aggression, it became even clearer to Germany that NATO should be strengthened, and that Europe’s partnership with the US remains vital to defeat Russia.

Significantly, however, certain elements have changed more radically

for Germany, likewise for France 1, due to the war in Ukraine. Both have adapted their views to the new geopolitical reality and should theoretically have opened up to the possibility of more fruitful cooperation.

For instance, Emmanuel Macron has understood that NATO is indeed an integral part of European defence, it is not experiencing “brain death” as suggested in 2019, and that the transatlantic alliance needs to be fully engaged in the defence of Ukraine. In contrast to Germany, however, France believes this to be a short-term solution, as it is sceptical about any future reliance on the US. And so, the shift in the French doctrine has been slight, but still perceivable, and this might have impacted cooperation with Germany positively since their views now seem more aligned.

As for Germany, it was shocked by Russia’s move on Ukraine and on 27 February 2022 Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke of a “Zeitenwende”,2 announcing a €100bn package devoted to its defence. Germany realised that it must take responsibility for its own security and not rely solely on the US, that it must contribute to European defence more generally, and that its partnership with France is vital – a realisation that should have brought it closer to its French neighbour who applauded the “Zeitenwende” speech at the time.

Both leaders have also drastically hardened their language against Russia and its president. At the beginning of the war, both tried to convince Putin through diplomacy to cease his attack. Today, Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron both clearly stress that Russia needs to be defeated and diplomatic pathways

“ Franco-German divisions are playing directly into Russian hands.”

have been shut down by both leaders. Statements such as “Russia’s defeat is essential” (Emmanuel Macron, February 2024) and “If the Russian president believes that he just has to sit this war out and that we will weaken our support, then he has miscalculated” (Olaf Scholz, March 2024) clearly illustrate this. Over the last two years while Russia has been waging war in Ukraine, it is clear that “rapprochement” might have been expected between the two historic partners, but this has not taken place because the basic views of European defence and of how Europe should respond to the Russian attack have remained the same for France, as well as for Germany. This is mirrored in their actions which have not occurred in unison, but rather unilaterally.

Secondly, the German decision to send US-Israeli rather than European military equipment to Ukraine – the latest decision being to deliver a third US Patriot air defence system in March 2024 – has led to major rifts as France insists on the need to buy European to strengthen the Union’s defence industry and, in fine, enhance its security sovereignty. Germany’s argument has

been that European equipment would not have been manufactured as fast, deeming France’s approach too unpragmatic in this emergency. France, however, views Germany’s approach to be too short-sighted.

Moreover, the French President’s suggestion of possible boots on the ground in Ukraine after the international conference in Paris in February 2024,3 led to Germany’s ire and a negative response by Olaf Scholz. This major disagreement came amidst debate over whether Germany would send Taurus systems to Ukraine – a decision against which the German chancellor voiced his firm opposition as he feared this would imply direct German involvement in the war. Trying to explain his decision, the chancellor said that “what the British and French are doing in terms of target control and monitoring of target control cannot be done in Germany”. France and Great Britain were surprised by a sensitive revelation such as this to the press which did not help smooth out Franco-German relations, on the contrary.

Thirdly, finding common approaches in the future will be increasingly difficult as mistrust, misunderstandings, and disappointments continue to grow and are more frequent. Recurring accusations have meant that clichés have started to fly between German and French officials, the media and the public, without much will to understand each other.

Debate over figures issued by the Kieler Institute is an interesting example in that sense. According to its statistics, Germany is the second largest donor to Ukraine (after the US) with France providing less than half of the military aid that Germany does. France explains this disparity with various arguments, but significantly here Germany persists in saying that France is lagging considerably behind, and France constantly accuses Germany of not sending the most pertinent equipment.

The most fruitful strategy – a strong Franco-German tandem pushing for a coherent European approach – seems to be the one losing out. And this is the one clear conclusion that must be drawn. Franco-German divisions are playing directly into Russian hands, although their approaches could be complementary, and their views brought together in a constructive way. ■

Stefanie Buzmaniuk is Senior Research Fellow and Development Manager at the Robert Schuman Foundation where she previously held the position of Head of Publications. Furthermore, she is an external lecturer at the French business school ESSEC, teaching the course “European Kaleidoscope”. She also worked as Research Assistant in the German-British think tank Convoco in London. Her research focus lies on the politics of European migration, the Franco-German relationship, and European identity.

© Adrien Thibault

TIran is a major obstacle to peace

by Gerhard Arnold, publisher and theologican, Middle East correspondent of this magazine, Würzburg

he states of the Middle East have experienced considerable upheavals over the past few years, which should in principle lead to a reduction in tensions and greater stability. However, the Gaza war and the de facto state of war between Israel and Iran harbour considerable potential for escalation. The biggest factor of uncertainty remains the regime of the mullahs in Iran.

The group of four on the move

Egypt, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, who call themselves “the quartet” see themselves as the vanguard of a new and better Arabia. The shock of the “Arab Spring” in 2011 made them realise that there is an urgent need for rapid economic and social improvements in the Arab world to give young people prospects for the future. The Egyptian government under al-Sisi does not need any new unrest and the population, which now stands at almost 110 million, needs better living conditions but has insufficient resources of its own. Population pressure and growing supply insecurity threaten the country's continued political and social stability.

Non-alignment as a new strategic goal

The upheaval in the Arab states of the Middle East also encompasses the geopolitical reorientation that Saudi Arabia in particular, the economically and politically strongest power

on the Arabian Peninsula, has pursued following the confusing policies towards the Middle East of US Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Today, the main plank of Joe Biden’s security policy is containing China, combined with a stratgic withdrawal from the Middle East. In response, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) has also been seeking better relationships with China and Iran as part of his own geopolitical reorientation. On 18 March 2023, the Saudi and Iranian foreign ministers agreed in Beijing on a rapprochement and the resumption of diplomatic relations. The Saudi leadership is also hoping that this will put an end to the missile and drone attacks on Saudi territory by the pro-Iranian Houthis in Yemen.

But economic developments are also driving Saudi reorientation towards non-alignment. MbS is looking to the post oil era and wants to diversify its economy, promote tourism and become the new banking and technology centre of the Middle East. This involves opening up the country to Chinese investors in particular.

His “Vision 2030” includes a gigantic construction and technology programme.

Syria's readmission to the Arab League at the instigation of Saudi Arabia – publicly celebrated at the summit in Jeddah on 19 May 2023 – was also linked to the hope that Syrian leader Assad would now make serious efforts to end the civil war in his country.

One of the positive developments in the Middle East is the attitude towards Israel. The small island kingdom of Bahrain under King Hamad al Khalifa began to visibly improve its political relations with Israel as early as 2017. The leading ruling house in the UAE, the Sheikh Zayid al Nahyan family, also made the pragmatic calculation that Israel was a very interesting military and technological cooperation partner.

With strong support from the then US President Donald Trump, the “Abraham Accords Declaration” between Israel, Bahrain and UAE was signed in Washington on 15 September 2020. They established diplomatic relations between Israel and the two Arab states and opened up prospects for greater cooperation in the economic and technological fields. Regional peacebuilding was also agreed. Morocco joined the agreement on 10 December 2020 and Sudan on 7 January 2021.

Due to pressure from the Arab populations, the Gaza war has led to a temporary standstill in cooperation under the Abraham Accords Declaration. Saudi Arabia is now likely to be prevented from formally joining the Abraham Accords for some time, but will continue to cautiously explore further rapprochement with Israel informally, despite the sceptical attitude of its own population.

“ The serious efforts by several Arab states to achieve regional stability, including with Israel, are being massively fought by Iran.”

Since the mullahs came to power in Iran in 1979, the Shiite country has pursued a largely destructive regional policy. At its core is the effort to export the Shiite revolution to neighbouring Sunni Arab countries and destabilise them. In addition, the regime wants to drive the US, with all its might, out of the Middle East and wipe out Israel, which it sees as a vassal of the US.

Iranian proxies have made massive efforts to destabilise Iraq since the Iran/Iraq War in 2003. Iran's political and military influence in Syria since the beginning of the civil war in 2011 is considerable, above all due to its military involvement in supporting the Assad regime. Iranian military bases threaten Israel. The regime has also been supporting the Houthi rebels in Yemen for some years and has allowed them, at the very least, to attack Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and now also Israel, with rockets and cruise missiles. Lebanon has been completely destabilised politically and is economically devastated, not least due to the efforts of the pro-Iranian Hezbollah, a Shiite militia.

Can there be peace with this problem state? No. The serious efforts by several Arab states to achieve regional stability, including with Israel, are being massively fought by Iran.

Against this background, Iran’s dangerous nuclear programme also has to be mentioned, particularly because Iran now produces highly enriched uranium that can be used to make nuclear weapons. The Iranian mullah regime is therefore the biggest obstacle to peace in the Middle East. Israel is particularly under threat because there are a number of Iranian proxies in its immediate neighbourhood: Hamas in the Gaza Strip, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Assad regime in Syria, all of whom have vowed to destroy Israel. The major Iranian attack on Israel on 14 April 2024 has also heightened fears among neighbouring Arab states of more Iranian aggression.

According to popular opinion, the solution to the IsraelPalestine conflict lies in the so-called two-state solution, entailing the establishment of an independent Palestinian state. However, it would be more accurate to speak of a three-state solution because the Gaza Strip, under the rule of Hamas, has become a separate political area to the West Bank, which is self-governed by the Palestinian authority. Israeli society, which is now deeply divided, is probably no longer capable of making decisions with regard to a peace solution with the Palestinians. And seen in the cold light of day, the Gaza conflict is insoluble as long as 2.3 million people in 364 square kilometers have no basis for their economic existence. The Gaza conflict is therefore likely to be the hardest nut to crack in efforts to bring peace to the Middle East.

There are visible efforts underway to calm the conflict and restore stability in the Middle East, as Israel, the US and several Arab states are working intensively to this end. However, strong population growth, not only in Egypt, is exacerbating social problems in many Arab countries. In addition, new challenges are emerging, like climate change and water scarcity. Three further factors continue to put a strain on regional stability: the still smouldering civil war in Syria, the economic collapse of Lebanon and the almost failed state of Iraq. As unbearable as the IsraeloPalestinian conflict is and will remain, it is also clear that Iran, under the continuing rule of religious fanatics, is still the greatest threat to this already conflict-ridden region. This will remain the case with the successor of President Ebrahim Raïssi who died in a helicopter crash in May 2024. ■

Gerhard Arnold

is a German protestant theologian and publisher. Born in 1948, he published numerous monographs and essays in the field of contemporary church history on the themes and issues of ethics of peace and international security policy.

by Hartmut Bühl, Paris

In April 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron, in a speech at the Sorbonne University in Paris, warned of Europe’s downfall, saying that “our Europe is mortal”. He stated that Europe must free itself from its strategic immaturity and at the same time called upon Europeans to form an efficient pillar in NATO to strengthen the Atlantic Alliance.

Macron’s speech made it clear that he is striving for more distance from the United States to reduce Europe’s dependency on America and build European capabilities. He described the US and China as Europe’s competitors. “We need strategic credibility for Europe”, he said, moving at least semantically away from his first Sorbonne speech in 2017, in which he called for “strategic autonomy” for Europe. This was met with widespread incomprehension at the time. Macron later created the term of “strategic sovereignty” which became his leitmotif for a Europe that takes its fate into its own hands: he wants to counter Europe's loss of importance in all strategic areas: political, economic, military, but also social and human.

Besides the terms of “strategic autonomy” and “strategic sovereignty” and the currently employed “strategic credibility” which leaves things more open, he also shaped the expression “strategic ambiguity". For him, this means leaving Ukraine’s aggressor Putin in the dark as to whether and when western states will intervene directly in the conflict in Ukraine.

Macron’s second Sorbonne speech caused a lot of fuss, especially since he once again talked extravagantly about the question of Europe's nuclear protection. “Nuclear deterrence is central to France’s defence strategy. It is therefore essentially a critical element of defence of the European continent”, he said. In France, his opponents accuse the president of betraying his country and De Gaulle's doctrine of 3 November 1959 because he wants to “share” France's nuclear force with European partners. They fear that while sharing the deterrence, only France would have to face the risk of a counterattack.

Far from declassifying France’s nuclear capabilities, Macron did not talk about sharing the responsibility of the “force de frappe” as his opponents claim. And yet, in the context of his

proposal for a European air defence belt – a European strategic missile defence 360° preventing any missile from entering European space – he cleverly linked French deterrence to European security. Indeed, in doing so, he gives the French nuclear weapons a European dimension, but this goes no further than the nuclear capacity of France, as a member of the European Union, being in itself dissuasive and protecting France’s neighbours by its mere existence.

Macron’s proposal for the European air defence belt is to be seen against the background of the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI), a German-led project to build a ground missile capability based on an integrated European air defence system including an anti-ballistic capability. Currently, 19 European Member States are part of it, but not France. For strategic reasons related to its deterrence, the country was not prepared to participate, since the belt was not sufficiently designed, but also because Macron did not see France being adequately considered from an industrial point of view. By triggering the debate around a European air defence belt, Macron wants to make up for the mistakes made.

“ Nuclear deterrence is central to France’s defence strategy. It is therefore essentially a critical element of defence of the European continent.”

Emmanuel Macron

President Macron’s 2024 speech at the Sorbonne shows once again that he is a doer who loves everything but standing still. His inclination for provocations is not easy for his European neighbours; it is driven by the wish to get things moving. To serve French interests... and Europe’s, of course. ■

Macron’s speech: https://bit.ly/4bnia7y

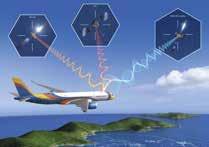

Space technology, data and services have become indispensable to the lives of Europeans. They allow millions of people to communicate via new technologies, travel securely, help tackle the effects of climate change, and ensure the wellfunctioning of critical economic sectors. Space assets also gain strategic value in the security and defence field and geopolitical importance in today’s growing space competition. This dependency on space is double-edged: space assets are more and more exposed to security threats, be it through collisions in Earth's orbit overcrowded with satellites and space debris, or cyber-attacks and hostile activities in space.

A crucial nexus

by Timo Pesonen, Director-General, DG Defence Industry and Space, European Commission, Brussels

In today’s complex and volatile geopolitical environment, space plays a pivotal role. It is crucial to protect the safety and security of our citizens, safeguard the interests of the EU and our Member States and ensure the well-functioning of critical economic sectors.

As Director-General of the European Commission's Directorate General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS), I find myself at the nexus of space and defence that are increasingly intertwined. Space and defence are instrumental to the EU’s freedom of action, rely on complex programme management capacities and require a competitive technological and industrial basis. There are many commonalities that we need to fully leverage.

Timo Pesonen

is the current Director-General of the European Commission’s DirectorateGeneral for Defence Industry and Space. After graduating in 1989 in International Politics from the University of Tampere, he served at the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From 2004 to 2014, he acted as Head of Cabinet of Vice-President Olli Rehn and from 2015-2019 he served as Director-General for Communication. He took helm of Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs in March 2019 and he accompanied the creation of DG Defence Industry and Space in 2020 as the head of the new Directorate-General.

Over the past years, we have torn down walls between space and defence, both at EU and Member States levels. This paradigm shift is substantiated by the EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence of March 2023. The European Union recognises space as a strategic domain and a key enabler for security and defence, addressing a wide spectrum of security challenges,

“ The European Union recognises space as a strategic domain and a key enabler for security and defence.”

ranging from defence, terrorism and cyber threats to maritime piracy and natural disasters, to name just a few. The role of space in Member States’ security and defence strategies is becoming more pronounced, reflecting both the evolving nature of threats and the rapid development of space technologies. Space is crucial for modern security architectures, providing new capabilities for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, secure connectivity, as well as positioning, navigation and timing (PNT). Space-based technologies enhance our situational awareness and resilience both in space and on Earth and enable rapid response mechanisms.

The European Union space programme already provides tangible services, assets and tools in support of security and defence with the already well-known Galileo and Copernicus components. Galileo, the EU global navigation satellite system (GNSS), ensures independent and reliable PNT capacity, reducing our dependence on foreign systems and bolstering the resilience of critical infrastructures, such as energy grids, transport networks or banking and financial services. Copernicus, the Earth observation component of the EU space programme, provides timely and accurate geospatial information that underpins various security services, from border and maritime surveillance to environmental monitoring and disaster management. Moreover, the EU is actively pursuing the development of spacebased capabilities tailored to the specific needs of EU defence and security users. Investing in cutting-edge technologies like the ones needed for secure governmental satellite communications, for space situational awareness, or for in-space operations and services, also reinforces and complements Member States’ capacities.

While space assets gain strategic value in support of security and defence operations, they become more and more exposed to security threats, including to cyber-attacks or to hostile activi-

ties in space. The level of threats has drastically increased in the context of Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine. We need to take action to improve the level of resilience and security of space infrastructure against cyber threats and electromagnetic interference. This is one of the priorities that we aim to address with the upcoming proposal for EU space law.

In tackling these challenges and seizing opportunities afforded by space, the EU must adopt a comprehensive and forwardlooking approach to better integrate security and defence needs into its space policy and the evolution of the EU space programme. This entails fostering closer collaboration between civilian and military stakeholders, leveraging public-private partnerships to drive innovation and investment in space technology, and strengthening our international partnerships to promote responsible behaviour in outer space.

While doing more for the competitiveness of our space industry, we need to increase our strategic posture as a space power. Our sovereign space capacities already offer services for security and defence and strengthen our strategic autonomy. As we look to the future, we are embracing the transformative potential of space and forging a path towards a safer, more secure and prosperous EU. ■

(nc) On 10 March 2023, the European Commission and the EU High Representative presented in a Joint Communication the “EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence” aimed at bridging the gap between space and defence.

The Strategic Compass of March 2022, issued one month after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, already identified space as a strategic domain in the geopolitical context of growing power competition and the intensification of threats. It underlined the need to boost the security and defence dimensions of the EU in space.

The new strategy is aimed to protect the EU’s space assets, defend its interests, deter hostile activities in space and strengthen its strategic posture and autonomy. It outlines the counterspace capabilities in the EU and main threats in space that put space systems and their ground infrastructure at risk. To strengthen the resilience and protection of space systems and services in the EU, the Commission will:

• Propose an EU space law to provide a common framework for security, safety, and sustainability in space, and ensure a consistent and EU-wide approach.

• Set up an Information Sharing and Analysis Centre (ISAC) to raise awareness and facilitate the exchange of best practices among commercial and relevant public entities on resilience measures for space capabilities.

• Launch preparatory work to ensure long-term EU autonomous access to space, addressing in particular the security and defence needs.

• Enhance the technological sovereignty of the EU by reducing strategic dependencies and ensuring security of supply for space and defence, in close coordination with the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the European Space Agency (ESA).

The strategy proposes the launch of two pilots: one for the delivery of initial space domain awareness services building upon capacities of Member States, and another for a new earth observation governmental service (EOGS). The latter will be made available to EU Member States in the next EU multi-annual financial framework (2028-2034) and will harness space data in support of autonomous European decision-making in the area of security and defence.

On 14 November 2023, the Council of the EU issued conclusions welcoming the new strategy. The Council proposed to:

• Increase the EU’s understanding of space threats through a yearly classified analysis, and the strengthening of military and civilian intelligence services on space security.

• Enhance the resilience and protection of space systems and services, acknowledging the Commission’s intention to propose an EU space law.

• Better respond to space threats through space domain awareness information, a dedicated toolbox for EU joint responses, and the further development of exercises.

• Enhance the use of space for security and defence purposes by better integrating the space dimension into Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions and operations; by strengthening the European Union Satellite Centre (SatCen); and by developing space services for governmental use at EU level, including by building on the EOGS pilot project proposed by the Commission. ■

“ Without security, there can be no future in space. (...) For the first time, we are putting forward a strategy that will pull together all our tools to protect EU space assets and ensure that everyone can benefit from space services.”

EU High Representative Josep Borrell

Who does what

by Nannette Cazaubon, Paris

Various agencies and institutions are involved in the implementation of the European Union’s (EU) space policy. Not all belong to the Union, there are also international and intergovernmental organisations that have signed agreements with the EU to support its space activities. In the following, we will highlight a few of them.

The European Space Agency (ESA), established in 1975, is an international organisation with 22 member states: 19 from the EU as well as Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Slovakia, Slovenia, Latvia and Lithuania are associate members; Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta and Canada have signed cooperation agreements with ESA. ESA is closely involved in the EU’s Space Programme through cooperation agreements. The agency’s mission is to promote, for exclusively peaceful purposes, cooperation among European states in space research and technology and their space applications, and to promote European industries. ESA’s activities include launchers, science, robotic and human exploration, navigation, Earth observation, telecommunications, space safety and operations. Headquartered in Paris, the agency has sites with different responsibilities in several European countries (see examples below). www.esa.int

The European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, is ESA’s largest site and the agency’s technical heart. ESTEC provides the managerial and technical competences and facilities needed to initiate and manage the development of space systems and technologies. It operates an environmental test centre for spacecraft, with supporting engineering laboratories specialised in systems engineering, components and materials. ESTEC is supporting European space industries and works closely with universities, research institutes and space agencies all over the world. www.esa.int/About_Us/ESTEC

The European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) located in Darmstadt, Germany also belongs to ESA (mission control). Recognised internationally as a centre of excellence for spaceflight operations, ground system engineering and satellite astrodynamics, ESOC has successfully flown more than 85 satellites belonging to ESA and its partners since 1967. It is also home to ESA's Space Safety programme, focused on hazards in space. Currently more than 20 satellites are flown from ESOC,

with a dozen new missions in development for future launch, including JUICE, Europe’s first mission to Jupiter.

https://esoc.esa.int

➭ See the article on ESOC, page 35

The European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA) headquartered in Prague, Czech Republic, is an EU agency under the supervision of the European Commission. Initially created as the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Supervisory Authority (GSA) in 2004, EUSPA was established in its current form in May 2021. As an operational agency, EUSPA leads the implementation of the EU Space Programme, promotes spacebased scientific and technical progress, and supports the competitiveness and innovative capacity of the space industry sector. The agency advances the commercialisation of Galileo, EGNOS, and Copernicus data and services, engages in secure SATCOM (GOVSATCOM & IRIS²), and operates the EU Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) Front Desk.

www.euspa.europa.eu

The European Union Satellite Centre (SatCen) headquartered in Torrejón, Spain, is the EU’s geospatial intelligence agency. It provides products and services resulting from the exploitation of relevant space assets and collateral data (including satellite and aerial imagery), and related services to EU institutions and Member States. Established in 1992 as part of the Western European Union (WEU), SatCen became an EU agency in 2002 under the supervision of the Council of the EU and the operational direction of the EU High Representative. The centre supports the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), including European Union crisis management missions and operations.

www.satcen.europa.eu

➭ See the article on SatCen, page 32-34 ■

12./13. Dezember 2024

Van der Valk Hotel Brussel Airport

Erstmals im Maritim Hotel Königswinter

Kriegstüchtig – aber wie?

Zur Sicherheit Deutschlands und Europas nach der US-Wahl

Sichern Sie sich noch bis zum 15. August 2024 Ihr vergünstigtes Early-Bird-Ticket

Weitere Infos und Tickets: mittler-report.de/veranstaltungen/sipo

Interview with Margit Mischkulnig, Head of Department for Space Affairs, Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology, Vienna

The European: Ms Mischkulnig, you are the Head of the “Space and Aviation Technologies” department in the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Protection, Energy, Environment, Mobility, Innovation and Technology (BMK). An impressive variety of topics brought together in a single ministry in Vienna, whereas in other countries they are spread over several ministries. Does this create synergies or is it sometimes difficult to reconcile the different areas of your ministry’s responsibilities?

Margit Mischkulnig: Indeed, our ministry has a very broad remit and in addition, it is also Austria’s Space Ministry. Satellite-based data and services support the green and digital transformation of our society and economy and make a significant contribution to achieving Austria’s goal of climate neutrality by 2040. Therefore, it is very positive from the space perspective to have so many potential users in-house and to be able to cooperate closely to see where space data can satisfy these special needs.

The European: Can you give a concrete example of such cooperation?

Margit Mischkulnig: A good example is the development of a demonstrator called “The Green Transition Information Factory” (GTIF) that was developed by Austrian space companies in very close cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA). GTIF makes the benefits and potential of space data very clear to the non-space sector.

The European: What significance do space and space technologies have for our European societies and for our future?

Margit Mischkulnig: Space technologies, data and services have become indispensable in our daily lives: when using mobile phones and car navigation systems, watching satellite TV, or withdrawing cash. Satellites provide immediate information about disasters and enable emergency and rescue services to be better coordinated. Agriculture benefits from improved land use. Transportation and energy infrastructure is safer and can be more effectively managed thanks to satellite technologies.

The European: And global challenges such as climate change require a lot of detailed information about our planet. What role can space-based solutions play in this challenging field?

Margit Mischkulnig: The 2021 report of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified earth observation satellites as a critical tool to monitor the causes

and effects of climate change. More than half of the Essential Climate Variables defined by the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) depend on space observations. Therefore, space assets are the key elements in providing observations and data that are global, uniform, sustained over years and repeated regularly.

The European: Space also has a role to play for our security by, for example, preventing military aggression through predictive intelligence. At the same time, space has become a place of global competition and the race to master space technologies runs the risk of exacerbating geopolitical conflicts. It seems to me that we are a long way from “peaceful space”?

Margit Mischkulnig: Space is indeed crucial for defence and security. The EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence of 2023 highlights the need to protect and increase the resilience of space infrastructure, strengthen technological sovereignty and address risks. And with the growing space economy, we also need to think about sustainability in space. There is a clear need for common rules governing safe and sustainable activities in outer space.

The European: What is the European strategy in this field?

Margit Mischkulnig: Europe is already taking first steps both in the observation and detection of space objects and in the management of space traffic, but we are only at the beginning.

The European: Is Austria playing a role in this process?

Margit Mischkulnig: Austria is very proud to have an international space hub in Vienna, with the UN office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) and the European Space Policy Institute (ESPI). Both already have sustainability in space on their agenda. To further advance work in this area, Austria will set up a Centre of Excellence for Space and Sustainability at ESPI, located in Vienna. The Centre aims to develop interdisciplinary expertise and know-how on the role of space in supporting sustainable development on Earth and will also address issues regarding the environmental footprint of the space sector itself as well as sustainability issues in outer space.

The European: We in Europe must no doubt combine all our efforts to make cooperative progress in space. Is Brussels doing enough to foster industrial synergies and human resources here?

“ Europe is destined to be a global space power!”

Margit Mischkulnig: Europe is destined to be a global space power! Increasing global competition forces the European Commission, the European Space Agency (ESA) and Member States to further strengthen cooperation.

The European: And what is the reality?

Margit Mischkulnig: Unfortunately, we are still a long way off. Nevertheless, I am convinced that it is essential to have a joint and coordinated approach at all levels to underpin Europe’s strong role in space. Furthermore, it is also necessary to communicate clearly to the outside world what goals are being pursued and what joint steps and measures are being taken to forge an independent and globally competitive European space sector.

The European: Although Austria is a small “space nation” compared to France, Germany, Italy and Spain, your country plays an important role in the concert.

Margit Mischkulnig: That is true. Austria’s membership of ESA and investment in specific ESA programmes as well as our national space funding have been an incentive for Austrian space companies to build up specific competencies and technological leadership, essential for participation in international value chains. A highly competitive supply chain

consisting of numerous dynamic small and medium-sized enterprises, an increasing number of start-ups and established research institutes characterise Austria’s space landscape. But the competition is tough!

The European: Space is a key driver for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). How do we introduce future generations to this topic?

Margit Mischkulnig: To illustrate the usefulness of space solutions, let me cite a 2018 study done by UNOOSA together with the then European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency (now named EU Agency for the Space Programme, EUSPA). This analysis shows that using space solutions has a positive impact on the implementation of all the SDGs. Space solutions help either monitor the status of achievement of a given SDG or actively contribute to its fulfilment. However, at the global level, we can see that space assets are often underutilised and access to the benefits of space remains unequal. There is a lack of information, skills and capacity to use space data.

The European: So, what steps need to be taken?

Margit Mischkulnig: We need to link the different sectors – space innovations and sector policies – more closely so that they can work together to develop innovative tools and solutions. In this sense, we are pursuing a real dynamic of change here in Austria through research, technology and innovation in the areas of climate neutrality and sustainability. We are convinced that innovation must become more transformative and be designed to advance sector policies and their objectives. In this way, we can create a bigger impact.

The European: Can you say a word about the report “EU Space supporting a world of 8 billion people: Contribution to the Space 2030 Agenda” published by UNOOSA and EUSPA in 2023?

Margit Mischkulnig: This joint report shows that cooperation at different levels between systems (Earth observation, GNSS, SATCOM, meteorology) and technologies (artificial intelligence, big data) and between stakeholder organisations (private and public partnerships, networks of academia or entrepreneurs) is of paramount importance to unlock the full potential of space technologies in countries and across continents.

“

I am convinced that it is essential to have a joint and coordinated approach at all levels to underpin Europe's strong role in space.”

The European: Isn’t that exactly the goal of the yearly Word Space Forum, to forge a new international consensus on how we deliver a better present and safeguard the future?

Margit Mischkulnig: You are right, the objective of this yearly event, launched by Austria and UNOOSA back in 2019, is to start a dialogue within the UN system that brings together diplomats, representatives from the space sector, policymakers, non-governmental organisations and young people. The last World Space Forum in November 2023 focused on providing space related input for the next Summit of the Future (September 2024) and the Pact for the Future. The zero draft of the Pact for the Future, which was presented at the end of January 2024, contains several paragraphs on outer space, for example: “We recognize that outer space is a rapidly changing environment and that there is an urgent need to increase international cooperation to harness the potential of space as a major driver of the Sustainable Development Goals.”

The European: Ms Mischkulnig, thank you for this conversation. I wish you every success in your important endeavours. ■

GTIF https://gtif.esa.int

Margit Mischkulnig

has been the serving Head of Department for Space Affairs at the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology (BMK) since September 2017. Holding a master’s degree in economics from the University of Vienna, her areas of specialisation include macro- and microeconomics with specific focus on industrial policy. Ms Mischkulnig joined the BMK in 2015, after working in the Ministry of Finance, the European Commission, and the World Bank Group.

(hb) The Outer Space Treaty, which entered into force in 1967, provides the basic framework on international space law. Talks on preserving outer space for peaceful purposes began in the late 1950s, during the cold war. However, the proposals of the United States and its western allies submitted in 1957 on reserving space exclusively for "peaceful and scientific purposes" was rejected by the Soviet Union which was preparing for the launch of the world's first Sputnik satellite and the test of its first intercontinental ballistic missile. Finally, an agreement, the Outer Space Treaty ruling space activities, was reached in the United Nations General Assembly in 1966.

The Outer Space Treaty provides the following main principles:

• The exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries

• Outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all states and is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty

• The moon and other celestial bodies shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and states shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies

• States shall be responsible for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities and shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects.

Updating the treaty

Today, the Outer Space Treaty, although considered a good basis, is outdated. It lacks specificity and does not reflect the growing number of countries involved in space activities, the rapidly expanding space industry implying private actors, and new space technologies. And while the treaty specifically prohibits nuclear weapons in space, it does not prohibit the use of conventional weapons or the use of ground-based weapons against space assets.

A new negotiated international outer space treaty should provide clear rules or guidelines for activities such as space mining, satellite operations, or space tourism and should also cover space weaponry, space debris, and finally, sanctions in case of non-compliance.

https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html

Thinking differently, ahead, together!

by Prof Dr-Ing Anke Kaysser-Pyzalla, Chair of the Executive Board of the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), Cologne

The often-cited “Zeitenwende” describes the end of an epoch, the beginning of a new era. Geopolitical developments over the past two years have ushered in such a turning point for Europe that is unique and far-reaching. We at the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) are aware of this and are ready, with our partners, to help shape Europe’s new direction. Mastering upheavals and challenges together is in the DNA of a research organisation.

DLR is one of the largest research and technology centres in Europe. We work on technologies for use in industry and business, as well as by authorities, administration and public stakeholders. DLR fulfils its responsibility to society through the intensive, open exchange of knowledge and targeted technology transfer. Current geopolitical developments require us to secure and maintain what we do best – our long-standing skills and competencies in research and development and our ability to evaluate, analyse and evolve – but we also now need to build upon and broaden our expertise. By combining our deep knowledge in aeronautics and space with our capabilities in energy, transport and digitalisation, we can develop the full potential for security and defence research at DLR. However, this requires us to rethink security and defence research itself, together with our partners in politics, industry and research.

“ By understanding national and international strategic areas of interest, we can quickly incorporate solutions into our developing capabilities.”

Dr Anke Kaysser- Pyzalla has been the Chair of the Executive Board of the DLR since March 2020. Previously, she was the President of the Technical University (TU) Braunschweig (20172020). After the completion of her doctorate in mechanical engineering and materials science at the University of Bochum and research activities at the HahnMeitner Institute (HMI) and the TU Berlin, she taught as a university professor at the Vienna University of Technology (2003-2005). She then joined the management team at the Max-Planck-Institut für Eisenforschung GmbH in Dusseldorf as scientific member, director and then managing director. In 2008, she was appointed as scientific director of the Helmholtz Centre for Materials and Energy in Berlin.

To collaborate, providing reliable and resilient expertise across the entire spectrum of DLR research is just as essential a task as driving innovation and development and quickly translating this into applications and capabilities. To develop methods, processes and systemic solutions, we need the strength to sprint, combined with the stamina to run a marathon. Having this attitude will allow us to secure and maintain our national core competencies and international competitiveness in the long term. This turning point also emphasises the importance of joint efforts. To do this, we need the right partners in the right places: good relations, regular coordination and joint exercises with Bundeswehr departments and civilian authorities with security responsibilities are essential for our research. By understanding national and international strategic areas of interest, we can quickly incorporate solutions into our developing capabilities.

For a long time, it has been clear that applications and capabilities developed for space are vital for our existence – from Earth observation and navigation to transport and, of course, security and disaster management. All space exploration, from military to civil, requires working together. Protecting the orbital infrastructure we have come to rely on is a task for the Bundeswehr, ministries and authorities, in cooperation with politics, research and industry.

It is said that security and innovation go hand in hand. We can guarantee the security of society and its infrastructures through the skilful, expert mastery of technology. Reliable and secure research into defence technology is urgently required to guarantee this in the medium and long term. We also need to be open, incorporating results of research into the development of new capabilities and providing insights into what is required next. Above all, we need a stable “triangle of action”, consisting of security organisations, industry and research.

Security and defence research does not have to be about “the gold standard”; in other words, geared towards real needs, simplification and rapid deployment capability. Research is always risky and its output and answers cannot be known for certain in advance, but it is in a position to provide disruptive, genuinely novel solutions to the world’s problems. Achieving this involves effectively using the technological openness that exists today and incorporating research findings from civil research more quickly.

At DLR, with our many decades of experience and diverse range of skills, infrastructure and expert workforce, we are ready. ■

New Location: Van der Valk Hotel Brussel Airport

21/22 January 2025

New Location: Holiday Inn Brussels Airport

Get your discounted early bird ticket now until 15 September 2024

Further information and tickets: mittler-report.de/events/lcm

(nc) The satellites launched into Earth's orbit by the European Union (EU) enable millions of people to communicate via new technologies and travel safely by land, sea and air. Space assets help tackle climate change, improve crisis response and increase security. In April 2021, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament adopted a regulation establishing the EU’s first integrated space programme (with a budget of €14.88bn for the period 2021-2027) to support the Union’s space policy.

The regulation on the EU Space Programme simplifies the existing EU legal framework and governance system and standardises the security framework. It improves and brings together under one umbrella existing EU programmes such as Copernicus, Galileo, and EGNOS.

The regulation establishes the European Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA) and assigns clear tasks to the institutions and agencies involved: the European Commission as the institution mainly in charge of the programme; EUSPA as the opera-

Copernicus is the EU’s Earth observation programme consisting of Earth observation satellites (Sentinel), in-situ sensors like ground stations, and airborne and seaborne sensors. Copernicus provides free information for urban area management, agriculture, forestry and fisheries, the mitigation of climate change effects, civil protection, transport, and tourism. Today, there are eight Sentinel satellites in orbit. The number is to increase to 20 before 2030. Copernicus is funded, coordinated and managed by the European Commission in cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT).

tional manager of Galileo and EGNOS, and responsible for the security and development of downstream applications for all components of the space programme; and the European Space Agency (ESA) responsible for research and development.

The main objectives of the programme are to:

• Provide or contribute to the provision of uninterrupted, highquality, up-to-date and, where appropriate, secure spacerelated data, information and services.

• Maximise socioeconomic benefits to enable growth and job creation and promote the widest possible uptake and use

Galileo is Europe's global satellite navigation and positioning system (GNSS), on which numerous EU economic sectors rely, from transport and agriculture to border management and search and rescue. The system consists of a ground, user, and space segment with currently 30 satellites orbiting Earth at an altitude of 23,000km. Galileo’s signals, providing 20cm accuracy, are freely transmitted and more than 2.5bn smartphones are already Galileo-enabled. Galileo is a joint initiative of the European Commission (overall responsibility), the European Agency for the Space Programme, EUSPA (operational management) and ESA (system evolution).

The European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) is Europe's regional satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS). EGNOS has been deployed to provide safety of life navigation services to aviation, maritime and land-based users over most of Europe. Today, EGNOS uses a set of geostationary satellites and a network of ground stations to increase the accuracy of GPS. A more powerful system (EGNOS V3), currently in preparation, will strengthen both Galileo and GPS signals. The exploitation of EGNOS is the responsibility of EUSPA, the operational management and maintenance of EGNOS is assigned to the EGNOS service provider under a contract with EUSPA.

of the data, information and services provided by the programme’s components both within and outside the EU.

• Enhance the safety and security of the EU and its EU Member States and reinforce EU autonomy, in particular in terms of technology.

• Promote the EU’s role in the global space sector, encourage international cooperation, reinforce EU space diplomacy and strengthen its role in tackling global challenges, supporting global initiatives and raising awareness of space as a common heritage of humankind.

• Enhance the safety, security and sustainability of all outer space activities concerning space objects and space debris proliferation, along with the space environment. The programme also introduces new security components, such as the Space and Situational Awareness (SSA) programme, which monitors space hazards, and the Governmental Satellite Communication (GOVSATCOM) initiative aimed at providing national authorities with access to secure satellite communications.

Two new flagship initiatives

In February 2022, the European Commission proposed two new flagship initiatives. The first is IRIS², a secure connectivity system that will provide ultra-fast and highly secure communication services by 2027. The second is Space Traffic Management (STM), as the exponential applications of space services involve more and

The European Union Governmental Satellite Communications (GOVSATCOM) programme aims to provide secure and cost-efficient satellite communications capabilities to security missions and governmental operations managed by the EU and its Member States. Facing threats ranging from natural disasters, pandemics or cyberattacks to traditional forms of conflict or instability, security actors will benefit from a guaranteed access and protection against interference, interception, intrusion, and cybersecurity risks. GOVSATCOM is being established by pooling the capacities of governmental and commercial satellite communication providers. The first implementation phase is running until 2025.

Rocket launches since 1957: about 6,500 (excluding failures)

Satellites placed into Earth’s orbit: about 16,990

Satellites still in space: about 11,500

Satellites still functioning: about 9,000

Debris objects regularly tracked: about 35,150

Estimated number of break-ups, explosions, collisions, or fragmentation: more than 640

Total mass of all space objects in Earth’s orbit: more than 11,500 tonnes

Last update: 06 December 2023

Source: ESA

more traffic in space and the congestion of satellites and debris puts the security of the EU’s and Member States’ space assets at risk (see box above). ■

https://bit.ly/3yk2e7a

IRIS2 (Infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite) is a multi-orbital constellation that will combine the benefits offered by Low Earth (LEO), Geostationary (GEO), and Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) satellites. It will deliver enhanced communication capacities to governmental users, businesses, while ensuring high-speed internet broadband to cope with connectivity dead zones. The system will support a large variety of governmental applications in domains such as border surveillance or crisis management and humanitarian aid. IRIS2’s initial services are to be delivered in 2024 and reach full operational capability by 2027.