Blue and white porcelain from the Yuan and early Ming dynasties

Blue and white porcelain from the Yuan and early Ming dynasties

ISBN: 978 1 873609 55 2

Design, Typesetting and Photography Daniel M. Eskenazi

Printed and originated by Graphicom Srl., Vicenza © copyright 2024 ESKENAZI London

Blue and white porcelain from the Yuan and early Ming dynasties

28 October - 15 November 2024

10 Clifford Street London W1S 2LJ

Telephone: 020 7493 5464

Fax: 020 7499 3136

e-mail: gallery@eskenazi.co.uk

web: www.eskenazi.co.uk

Detail of cat. no. 4

Underglaze blue porcelain

‘Three Friends of Winter’ dish

Ming dynasty, Yongle period, 1403 - 1424

We are proud to present a small but distinctive group of early blue and white porcelain, a subject that is a particular favourite of my father’s and in which the gallery has been dealing in since the 1960s.

The production of Chinese blue and white high-fired porcelain, helped by imperial patronage, baffled potters in Europe who for centuries struggled to match its qualities until the arrival of Meissen in the early eighteenth century. The Yuan and early Ming dynasties marked a clear departure from the subdued and intimate Song ceramics of the past, to an altogether brighter extrovert ceramic that could be more easily admired and impress from afar. This new wave of instantly recognizable underglaze cobalt-blue porcelain with bold contrasting designs has placed the most indelible stamp on the history of world ceramics.

This exhibition, comprising of a cup, five dishes and a guan jar, though not comprehensive, is a select group chosen for quality and rarity. The Yuan barbed dish not only has an even and beautifully painted design in blue on white but also incorporates rarely used white on blue for the moulded leaves and flowers on the rim and cavetto. The fluted cup is a joy to hold, as are the symbolic grape and Three Friends dishes. The impressive large barbed dish, with three central lotus flowers, illustrates how venerated these ceramics were with a seventeenth century etched inscription on the exterior foot-ring indicating it once belonged to Alamg i r I (Awrangzib) (r. 1658 - 1707) . The guan jar, one of only five known, is by far the most complex ceramic of the group. The technical achievement of the Yuan potter comes from not only the four intricate medallions in relief, depicting leafy flowers in a rock garden, but also the flowerheads picked out in underglaze copper red, the hardest glaze to fire correctly at the time.

Diameter: 32.0cm- c

图录 4 号展品细部

青花岁寒三友缠枝四季花卉纹盘 明永乐( 1403 - 1424 年 )

直径32.0 公分

I would like to thank Sarah Wong for her research and cataloguing of the exhibition as well as providing a most informative essay on the remarkable guan jar. I would like to welcome Cherrei Tian to our team and I thank her for translating Sarah’s texts into Chinese.

Both my father and I have enjoyed assembling this exhibition together, reacquiring ‘old ’ friends and making ‘new’ ones, which we hope you will enjoy seeing in person.

Daniel Eskenazi

我们很荣幸可以展出这组别具一格的早期青花瓷,这是艺廊自六十年代起 便涉及的题材,也是我父亲的最爱。

回顾历史,在朝廷 加 持下的中国青花瓷产业,几个世纪以来令欧洲的工 匠们一筹莫展,直到十八世纪初梅森瓷器的诞生之前,他们都一直在努力 的追赶。

和宋代内敛含蓄的风格截然不同,元和明早期青花瓷器的审美转 向鲜明华丽,令人过目不忘。 这种蓝白相间的大胆设计,极具辨识度,在 世界陶瓷史上留下了举足轻重一笔。

此次展览包括一只小杯,五件盘子和一尊大罐。件件展品都精挑细选, 其中元代莲塘纹菱口折沿大盘以白底蓝花满饰盘心,在折 沿和内壁处巧妙的 反转,以蓝底白花突出了模印的花叶,实在独具匠心。青花葵花式杯小巧 玲珑,葡萄纹盘和岁寒三友盘更是令人爱不释手。另外,气势恢宏的青花 十二瓣折枝菱口盘圈足旁有一处十七世纪波斯铭文,显示此器属阿拉姆吉 尔皇 Alamg i r I (Awrangzib) (r. 1658 年 - 1707 年 ) 旧藏,足以见其出处显赫。

青花釉里红大罐无疑是这组展品中工艺最为繁复的一件,世间仅存五件, 弥足珍贵。元代匠人们技艺炉火纯青,四处镂雕开光内的花卉枝叶栩栩如 生,其中花朵处釉里红呈色鲜艳,在当时不可多得。

我要感谢王嘉慧对展览的编目、严谨的研究和图录撰写,尤其是对元代 大罐全面的论述。我也希望借此机会欢迎田园加入我们的团队,感谢她将 图录译成中文。

我和父亲都很享受策划这个展览的过程,希望诸位都有机会见到这些 Daniel Eskenazi

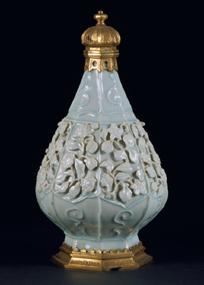

Detail of cat. no. 2

Large underglaze blue and copper-red porcelain jar ( guan )

Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352

Height: 33.0cm

图录 2 号展品细部

青花釉裏红大罐

元 约 1320 - 1352 年

高 33.0 厘米 “故人”和“新友”。

Chronology

Chinese Dynasties and Periods 中国朝代

Xia period 夏 2100c – 1600c Period of Erlitou culture 二里头文化 1900 – 1600

Shang period 商 1600c – 1027

Zhengzhou phase

Anyang phase

1600 – 1400

1300 – 1027

Zhou period 周 1027 – 256

Western Zhou

1027 – 771

Eastern Zhou 东周 770 – 256

Spring and Autumn period

Warring States period

dynasty 秦 221 – 206

Han dynasty

Han

dynasty (Wang Mang)

Six Dynasties period

– 9

Sixteen Kingdoms

304 – 439 Northern Wei

Western Wei

– 535

535 – 557

Eastern Wei 东魏 534 – 549

Northern Qi

550 – 577

Northern Zhou 北周 557 – 581

Sui dynasty 隋 581 – 618

Tang dynasty 唐 618 – 907

Five dynasties 五代 907 – 960

Liao dynasty 辽 907 – 1125

Song dynasty 宋 960 – 1279 Northern 北宋 960 – 1127

Southern 南宋 1127 – 1279

Jin dynasty 金 1115 – 1234

AD 公元

Yuan dynasty 元 1271 – 1368

Ming dynasty 明 1368 – 1644

Hongwu

Jianwen

Yongle

Hongxi

Xuande

Zhengtong

Jingtai

Tianshun

Chenghua

Hongzhi

Zhengde

Jiajing

Longqing

Wanli

Taichang

Tianqi

Chongzhen

洪武 1368 – 1398

建文 1399 – 1402

永乐 1403 – 1424

洪熙 1425

宣德 1426 – 1435

正统 1436 – 1449

景泰 1450 – 1456

天顺 1457 – 1464

成化 1465 – 1487

弘治 1488 – 1505

正德 1506 – 1521

嘉靖 1522 – 1566

隆庆 1567 – 1572

万历 1573 – 1620

泰昌 1620

天启 1621 – 1627

崇祯 1628 – 1644

Qing dynasty 清 1644 – 1911

Shunzhi

Kangxi

Yongzheng

Qianlong

Jiaqing

Daoguang

Xianfeng

Tongzhi

Guangxu

Xuantong

Republic of China

顺治 1644 – 1661

康熙 1662 – 1722

雍正 1723 – 1735

乾隆 1736 – 1795

嘉庆 1796 – 1820

道光 1821 – 1850

咸丰 1851 – 1861

同治 1862 – 1874

光绪 1875 – 1908

宣统 1909 – 1911

中华民国 1911 – 1949

People’s Republic of China 中华人民共和国 1949 –

Fig. 2

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze cobalt-blue and copper-red decoration, Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352, overall height 41.0cm (including cover). Excavated in 1964, Baoding City, now in The Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig. 4

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze cobalt-blue and copper-red decoration, Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352, height 34.3cm, private collection

Fig. 1a

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze cobalt-blue and copper-red decoration, Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352, height 33.0cm, now in the British Museum. After Sotheby’s, London, 25/4/1933

Fig. 1b

The same jar as in Fig. 1a. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Sir Percival David Foundation; ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig. 3

Pair to jar in Fig. 2, height 42.3cm. Hebei Museum, Shijiazhuang

5

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze cobalt-blue and copper-red decoration, Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352, height 33.0cm, number 2 in the present catalogue

Yuan Porcelain Innovation and Adaptation: An Underglaze Blue- and Red-Decorated Guan Jar

by Sarah Wong

Introduction

This magnificent and extremely rare guan jar embodies the innovative, bold and groundbreaking nature of Yuan dynasty (1271 - 1368) porcelain. It is one of a select group of only five known Yuan porcelain guan jars of this design, three of which are in museum collections. On this jar, we see the use of three main decorative techniques, all of which were relatively novel in their own right, adapted, combined and brought to daring new heights. These highly skilled ceramic techniques include the painted application of underglaze cobalt blue, of underglaze copper red and the use of applied floral relief decoration. The three techniques will be considered in relation to this group of jars, as well as within the wider context of Yuan porcelain, including its reception and use.

As described above, this group of five large guan jars combine the use of underglaze cobaltblue and underglaze copper-red decoration and are also all ornamented around the body with four ogival panels, each containing different flowers and rocks in relief, enclosed by double beaded borders. The shoulders of the vessels are painted in underglaze blue with filled cloud collars alternating with other motifs and the bases are encircled by painted lotus petal lappets. 1 One of these jars is the well-known example formerly owned by a founder member of the Oriental Ceramic Society, S. D. Winkworth (1864 - 1938) and sold at auction in London in 1933, having been in his possession for at least ten years. It was acquired by fellow member, Sir Percival David, and is now exhibited at the British Museum as part of the Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Trust (figs. 1a and 1b). A similar pair of these jars, together with their covers with lion-shaped knops, was discovered at Yonghua South Road, Baoding, Hebei province in 1964 in a hoard which contained eleven porcelain objects, among which were also a pair of octagonal meiping vessels, a yuhuchunping bottle, a ewer and monochrome blueglazed vessels. Of the two guan jars related to the present example, one is now in the Palace Museum, Beijing (fig. 2) and the other is in Hebei Museum, Shijiazhuang (fig. 3). A fourth jar was auctioned in London in 1972 where it was acquired by the Japanese dealer Goro Sakamoto; when it was auctioned again in Hong Kong in 2002, it was acquired by Eskenazi Limited and is currently in a private collection (fig. 4). The jar in this exhibition was formerly in a Belgian, and later a Flemish, collection and is the fifth example known at present (fig. 5 and number 2 in the present catalogue).

The present jar, together with the other related examples, represents the height of Yuan porcelain technology and sophistication, while in terms of aesthetics, it embodies what we have come to think of as characteristics of that period – namely, a boldness of decoration, a horror vacui and an innovative three-dimensionality in porcelain design. In addition, the large size of the jar, which required it to be luted together at the leather-hard stage, was a relatively new development in porcelain and large-sized blue and white wares came to characterize much of Yuan production now found in global collections.

The Fouliang Porcelain Bureau ( Fouliang Ciju ) was established early in the Yuan dynasty, in 1278, at Jingdezhen, to manage the production of porcelain and to supply the court at the capital, Dadu, as needed. The appointed officials – a Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner – supervised the production of porcelain for court use, as well as the manufacture of lacquer, horsehair, coir rattan and straw hats. They were concerned with a range of issues including ‘quantity, design, colour, use, restrictions on private production, official posts and production difficulties.’ 2 As with many Yuan appointees, some were drawn from Central Asia or from the Islamic West; the first Supervisor of the Porcelain Bureau was Nepalese while successive officials included those of Persian or Mongolian origin. 3

Skilled artisans, including potters, were highly prized under the Mongol regime and were often moved around the different regions of the empire, which in turn fostered a rich crossfertilization of materials and techniques. During the Yuan, Jingdezhen artisanal potters were

mostly free individuals who, once imperial orders had been fulfilled, were allowed to produce wares in their private workshops for sale. 4 Peter Lam explains how there might have been access to porcelain ingredients tightly controlled by the Fouliang Porcelain Bureau in his quote from Kong Qi, Zhizheng zhiji (Faithful Records of the Zhizheng Reign, preface dated 1363):

Every year officials were dispatched to supervise the production [of porcelain], hence it has been called Imperial Clay. After the official production the clay mines are sealed up and the potters do not dare to secretly use it for their own private consumption. However, if there is a surplus of clay after producing the official pieces, potters may use it to fire dishes, basins, bowls, plates, bottles, ewers and cups. 5

The potters at Jingdezhen therefore were producing porcelains both for private commissions and court use. One of the major innovations at Jingdezhen was the introduction of underglaze brush-applied painted decoration using cobalt blue by the 1330s, apparently inspired by Persian underglaze blue techniques and materials. Concurrently, or even slightly earlier, another Jingdezhen innovation was the introduction of underglaze copper-red decoration. This technique of painting under a transparent glaze was enabled by some specific technical changes at Jingdezhen in the early fourteenth century. One of these was the introduction of the use of kaolin clay ( gaoling ) during this period, combining it in around 10-20% additions to the traditional body material of porcelain stone ( ciqi ), used for example on Song dynasty (960 - 1279) qingbai wares. This not only increased the volume of raw materials available to the potters but also allowed ‘porcelain bodies to be adjusted to variations in kiln temperature –simply by varying the clay to rock ratios.’ 6 The bodies could be fired at a higher temperature to produce finer, harder porcelains. This combination of kaolin and porcelain stone was referred to as ‘imperial clay’ ( yutu ), as discussed above. 7 The glaze on Jingdezhen porcelain was also adapted to the requirements of underglaze painting to enable the design to be more visible. According to Wood op. cit., it was exactly half-way in ‘appearance and composition’ between the fluid qingbai glaze and the more opaque shufu glaze (see below), with the recipes for Jingdezhen lime-alkali glazes using around 10-20% glaze ash. 8

Yuan Qingbai

Of the different types of white porcelains made at Jingdezhen in the Yuan, only qingbai wares will be considered here in relation to the present jar, with its remarkable applied relief decoration in ogival reserves, enclosed by beaded borders. The other well-known Yuan white ware was a version with a thicker glaze known as luanbai or ‘egg white’ (also called shufu and taixi wares after the characters moulded on them), probably for official or ritual purposes.

From the Song dynasty, kilns at Jingdezhen had already established commercial success with the production of the high-fired qingbai (meaning ‘blue white’) wares with their monochrome icy bluish-white glaze. The Hutian kiln at Jingdezhen was the main source of qingbai porcelain, primarily bowls, plates and other table wares, many with a close affinity to silver vessel shapes. During the Yuan, demand from domestic and export markets continued. The importance of the colour white to the Mongol Court and the preference for white porcelain, was probably a factor in the continued popularity of qingbai through the Yuan. 9

Of particular relevance to the present jar is a small group of qingbai vessels decorated with ogival reserves containing applied floral decoration in relief, edged with ‘strings of pearls’ or beaded borders. The most celebrated of these is the Yuan qingbai Fonthill vase, now in the National Museum of Dublin, the earliest recorded Chinese porcelain to have arrived in Europe (fig. 6). It was received in 1338 by Louis the Great of Hungary (ruled 1342 - 82), as a gift from a Chinese embassy on its way to visit Pope Benedict XII (1334 - 42). 10 The pear-shaped vessel ( yuhuchunping ) has the characteristic icy-blue qingbai glaze and the sides are decorated with four quatrilobed cartouches containing different flowers including chrysanthemum, enclosed by fine applied beading. The neck of the Fonthill vase is decorated with scrolls within leaf lappets, also defined by beaded edges. A related vase is in the British Museum collection (fig. 7) and another pear-shaped vase with eight sides, each with different floral motifs, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 8). Other qingbai forms with this type of elaborate decorative beading and applied floral motifs include meiping vessels, stem cups and pillows. 11 It should be noted that this type of beaded and applied floral decoration is also occasionally found on Jingdezhen luanbai wares as well (fig. 9). 12

A related development at the qingbai kilns was the production of devotional figures. The Yuan dynasty saw the continuation of this with large Buddhist and Daoist sculptures in

Fig. 6

The ‘Fonthill vase’, porcelain, Jingdezhen qingbai ware, Yuan dynasty, height 29.1cm. National Museum of Ireland, Dublin

Fig. 8

Octagonal porcelain bottle vase, Jingdezhen qingbai ware, Yuan dynasty, with later German ormolu mounts, height 27.8cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig. 7

Porcelain bottle vase, Jingdezhen qingbai ware, Yuan dynasty, height 27.5cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig. 9

Porcelain stem cup, Jingdezhen luanbai ware, Yuan dynasty, height 12.7cm. Excavated in Yangzhou city, now in Yangzhou Museum

Fig. 10

Porcelain seated bodhisattva, Jingdezhen qingbai ware, Yuan dynasty, late 13th - early 14th century, height 67.0cm

Fig. 11

Lobed, gilded silver dish, Liao dynasty, 907 - 1125, length 19.9cm. Excavated in Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia. Inner Mongolia Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology

Fig. 12

Chabi, Khubilai Khan’s Consort , album leaf, ink and colour on silk, Yuan dynasty, 61 x 47.6cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig. 13

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze copper-red decoration, Yuan dynasty, height 24.0cm. Excavated in Gao’an city, Jiangxi province. Gao’an Museum

porcelain. Amongst these, Avalokiteshvara Guanyin was apparently the most popular (fig. 10). The figures in this well-documented group are finely modelled and many of the Guanyin figures are ornamented with elaborate, finely beaded necklaces which are similar to the beaded borders on the vases above and on the jars in the group being discussed. The famous 1968 Cleveland exhibition included the Manjushri figure from the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; the bodhisattva from the Rietberg Museum; the Shakyamuni Buddha from the Royal Ontario Museum; and the Water Moon Guanyin in the Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City with an inscription with a date corresponding to either 1298 or 1299. 13 Also notable is the Guanyin in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, wearing a beaded necklace and a beaded ‘apron’ draped over the legs. The elaborate jewellery and beaded necklaces on all these figures bear a strong relationship to the decorative jewellery on Sino-Tibetan Buddhist bronze sculpture and John Ayers, for instance, has concluded that on these sculptures, the ‘crisp and refined treatment of jewellery and beaded work…These ornaments betray a metal original…’ 14 Denise Leidy has elaborated further, suggesting that the figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its unusual dress and ornaments ‘demonstrates the responsiveness of the qingbai kilns to evolutions in Buddhist practice at the time.’ 15 Another seated figure of Guanyin with a similar beaded pectoral and apron is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. 16

While the relationship between the examples cited and the jar in this exhibition is evident, the details of the technology are not much discussed. On the present jar, and the others, the ogival

panels were hollowed, likely while at the leather-hard stage. The floral and rock decorations were probably created in moulds, perhaps even in sections or panels, with further details –such as the veins on the leaves - added by careful hand incising. They were then applied to the hollowed panels on the jar to create relief decoration, providing an impression of carved openwork. The blue and red colourants were delicately applied to the relief elements and a transparent glaze applied. The beaded borders were also probably made in moulds and applied in strips or curved swags. These beaded borders and dividers on Yuan vessels were a useful element to lend coherence to the dense surface decoration often found at this period, perhaps later to be replaced by production-efficient moulded or painted borders.

The question of transfer and its chronology is difficult to establish. However, the close relationship between qingbai wares and silver vessels is acknowledged. The connection between the relief decoration and beaded borders on this jar and metalwork, whether the beaded borders on silver or gold vessels (fig. 11) or the jewelled ornament of bronze figures also appears tantalisingly close. One of the most well-known artists directly under imperial patronage was the Nepalese sculptor Anige (1244 - 1306) who was celebrated for his cast metal sculptures amongst other works. 17 He rose through the ranks quickly and became Director of All Artisan Classes in 1273 and Controller of Imperial Factories in 1278, supervising craftsmen throughout the empire. 18 It is not inconceivable that stylistically, qingbai Buddhist sculptures with their beaded decoration drew inspiration from his body of work and artistic direction. It is of course hard to distinguish the material intended to be depicted on the beaded necklaces, either on the bronze or porcelain figures. Some may have been traditional Buddhist rosaries, but it is tempting to speculate that the more complex necklaces may have been intended to be pearl strands. Along with precious metals and stones, pearls were highly valued by the Mongols, evident in the portrait, now in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, attributed to Anige, of Chabi, the principal consort of Khubilai Khan (r. 1260 - 1294), shown with her boqtaq ( guguguan) headdress and hair lavishly decorated with strands of pearls (fig. 12).

A striking and unusual aspect of the present guan jar is the use of underglaze copper red as a decorative element, alongside the use of underglaze blue cobalt. The beautifully controlled copper red is restricted to the applied relief panels, painted on the flowers and the rockwork bases.

One of the early decorative techniques on porcelain at Jingdezhen was the painted application of copper-red pigments under the glaze, appearing around the same time, or perhaps slightly before the use of cobalt blue, around the 1310s or 1320s. 19 Copper is very difficult to control particularly when fired in reduction and tends to spread into the glaze at high temperatures, often firing either to a grey or blackish-red, although this is not the case on the present jar. Copper had been previously used as a decorative element to great effect at various kilns including at the Changsha kilns in Hunan province, during the Tang. It was also used at the Jun kilns in Henan province during the Yuan and Jin (1115 - 1234) periods where copper was brushed onto the glazed surface of a stoneware body to produce dramatic swirls and suffusions after firing. An early and often cited example of underglaze red on porcelain is the oval dish, decorated with moulded leaves and a poem, discovered from the Sinan wreck, its last voyage in 1323. Bound for Hakata in Japan, the cargo of 20,661 pieces of ceramic, mostly from Longquan, Jingdezhen and Jizhou kilns, included white and celadon wares but no blue and white was discovered.

An outstanding cache of Yuan ceramics discovered at Gao’an in Jiangxi province in 1980 included around 239 ceramic objects, among which were sixty-seven pieces from Jingdezhen. The cache was likely hidden during a time of political upheaval, perhaps between 1341 and 1351. 20 Together with outstanding examples of blue and white meiping and guan jars, were only four underglaze red porcelains including stem cups, a spouted vessel and a guan jar painted with birds and flowers. The latter is particularly relevant to this discussion. Measuring 24.0cm in height, this jar, now in Gao’an Museum, is painted with four ogival panels filled with birds and flowers, interspersed with cloud scrolls, both recalling the decoration on the present jar. Here the use of copper red is relatively successful – the colour is bright and the painting remains clearly defined (fig. 13).

Also relevant to this group of jars is the Yuan tomb of Madam Ling, the wife of a Yuan official, discovered in 1974 in Fengcheng county, Jiangxi. The tomb contained a small but significant group of four porcelain objects with underglaze copper-red decoration, two of them

Fig. 14

Porcelain guan jar with underglaze copper-red and cobalt-blue decoration, dated 1338, height 22.5cm. Excavated in Fengcheng county, Jiangxi province. Jiangxi Provincial Museum

Fig. 15

Porcelain model of a storage building with underglaze copper-red and cobalt-blue decoration, dated 1338, height 29.5cm. Excavated in Fengcheng county, Jiangxi province. Jiangxi Provincial Museum

also inscribed in underglaze blue with dates corresponding to 1338 (fourth year of Zhi Yuan); all are now in Jiangxi Provincial Museum. 21 One is a funerary guan -shaped jar with applied high relief decoration of the Animals of the Four Directions and a cover with a double beaded border, topped by a stupa (fig. 14). 22 On this jar, the copper red, only partially controlled, is mostly applied to the high relief decorative elements as accents. It is inscribed around the neck with a dated inscription in underglaze blue, with a further inscription around the shoulder.

Also discovered in this tomb was a porcelain model of a tiered storage building which is also decorated with a combination of underglaze blue and underglaze red, along with iron pigments (fig. 15). The structure is elaborately constructed, with figures of musicians and dancers on a balcony on the upper level while the lower level is set with an epitaph panel inscribed in underglaze blue which has fired to a greyish colour; further inscriptions on the sides are in copper red. The building is also pertinent in its complex use of beaded borders to define the balustrade and the roof ridges. Also included in the tomb were two porcelain figures of officials holding tablets, their robes glazed in copper red.

On the two objects above, the combined use of copper red and cobalt blue under the glaze, with inscriptions referring to a burial date of 1338, must surely be regarded as a technological milestone. Their relevance to the jars in our group is clear, even if the blue on the tomb furniture is not recognisably the bright, rich blue we associate with Yuan wares. It is notable that this ‘revolutionary’ underglaze combination on porcelain is found here on a group of funerary wares and that the cobalt blue is a much smaller proportion of the pigment compared to the copper red and confined mostly to the inscriptions. This use of two pigments is also found on a small group of Yuan porcelains, possibly for court rituals. These include dishes and stem cups with moulded decoration, using a monochrome blue cobalt glaze and a monochrome dark reddishbrown glaze; on most of these vessels, reddish brown is used for the exterior of the vessel and blue for the interior. 23

The Yuan dynasty is the period when the kilns at Jingdezhen first began to produce blue and white decorated porcelain as we know it. The potters there started using a recognizable cobalt blue around the 1330s to produce a vivid blue decoration. The earliest known dated inscriptions on ‘mature’ blue and white porcelain, corresponding to 1351, are on the famous pair of ‘David Vases’ in the British Museum. This type of porcelain came to be known as ‘Zhizheng ware.’ The cobalt pigments used on porcelain in the Yuan have been consistently found to be ‘high-iron cobalts with minimal manganese contents’. 24 Sources of the iron-rich

16

cobalt ore is still a subject of debate but clearly, the extensive trade across the Mongol empire would have allowed greater access to cobalt sources in the Middle East and Il-Khanate Persia where cobalt pigments were already in use as ceramic decoration, and the presence of officials in China from different regions would also have enabled the process. Kerr and Wood do point out though: ‘the usual source proposed for Yuan dynasty Ching-te-chen cobalt pigments, i.e. Qamsar (near Kashan) in Persia, has merits on both compositional and historic grounds. Nevertheless, Persia is far from being the only country where this kind of rock is found.’ 25

Before this period, painted decoration was not a significant feature of Jingdezhen porcelain. It has been posited that the decorative technique of painting on high-fired wares, and indeed, skilled artisans, may have been transferred from nearby kilns, such as Jizhou in Jiangxi province. Gerritsen op. cit. argues that ‘the technology of underglaze painting and calligraphy… came into Jingdezhen via the nearby ceramics centre of Jizhou. The Jizhou potters, in turn, adopted this technology of underglaze painted decorations from the ceramic centres in the north, collectively known as the Cizhou kilns.’ 26 The crucial difference with Jingdezhen however, lay in the use of cobalt, as opposed the other kilns where iron was the main colourant, used to produce dark painted designs against a cream-coloured background on stoneware.

Regardless of how the technique of painted decoration was transmitted or started at Jingdezhen, the fact it was not used there before the Yuan meant that the potters would have drawn inspiration, not just from other kilns, but also from pattern books, from the other decorative arts and from woodblock printed books, as seen on certain vessels with figural decoration. For official wares, ‘orders for quantity and design of porcelains came from the Imperial Manufactories Commission’ ( Jiangzuoyuan ). The designs may have originated with court painters in the Painting Academy which was under the auspices of the Imperial Manufactories Commission. 27 Official decorative motifs were controlled by the Design Office ( Hu Ju ). The present jar and its companions feature design motifs characteristic of Yuan porcelain. The striking ‘cloud collars’ ( yunjian ) on the shoulders, here painted with wide borders and filled with waves and lotus, are a notable feature of Yuan ceramics, textiles, including court dress and royal tents, as well as the decorative arts (fig. 16). Watt op. cit. suggests that the design originated in the Eastern Han as a ‘four-leaf pattern around the base of the knobs of bronze mirrors or as foil decoration around the ring handle on the cover of lacquer boxes.’ He traces its reappearance in Liao metalwork to around the tenth century and then in the textiles of the regions along the Silk Roads. 28 On this jar, as on the Baoding examples, the point of each cloud collar has a tassel, perhaps a nod to textile design. The device is frequently found on Yuan porcelain, filled with different motifs including scrolling peonies, waves and, as here, the lotus pond; the lotus was a Buddhist motif arriving in China with the religion in the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) and the lotus pond is a recurring subject on Yuan porcelain.

The dramatic ogival cartouches on the present jar, outlined with double beaded borders also play a central role in the Yuan decorative vocabulary. They are found throughout Yuan metalwork (fig. 17), lacquer (fig. 18), architectural elements and the decorative arts, working admirably to define and structure the exuberant design elements typical of Yuan. They also figure heavily in underglaze painted porcelain of the period (fig. 19). On the present jar, they enclose and make a feature of the applied flowers and rocks, which was a novel combination that came to be used frequently on later porcelain. On a pragmatic level, both the cloud collar and the ogival panel, with their resonances across the decorative arts, were useful elements within the dense designs on Yuan porcelain. With some surfaces entirely filled, separating devices were needed; both these motifs offered interesting visual alternatives to the horizontal and vertical borders.

As a high-value and rare object, who would have used this jar, and what was its function?

Feasting and banqueting had a central role in Mongol-Yuan society. So much so that ‘an edit to ban such lavish banquets was decreed by the central government’ so that ‘upper and middle households’ were limited to two and three courses and ‘serving a certain amount of wine.’ 29 However, this presumably did not apply to the upper echelons where feasting and banqueting continued to be a way of life. Indeed, the conspicuous consumption of drink was a feature of elite Mongol life and their festive events.

For official and sacrificial purposes, the Mongol court tended to use vessels made of precious metals and white porcelain in comparable shapes; such high value wares were favoured for banquet tables. Wine vessels clearly had a central role and various shapes of wine vessels existed for different purposes, such as warming, serving and drinking wine, in metal and in porcelain. During the Yuan dynasty, wine might have been drunk from a footed bowl with its matching dish or from a stem cup. Vessels for pouring wine included handled ewers with spouts and, also, pear-shaped bottles ( yuhuchunping ). Low-sided vessels with a spout ( yi ) feature in Yuan porcelain and metalwork – such vessels apparently had a dual purpose of warming and pouring wine. Wine storage jars tended to be larger vessels, sometimes in blue and white, and were forms such as the meiping vessels and guan jars like the present example. Both shapes were originally designed with covers to prevent the evaporation of alcohol. 30 They were likely used to store wine during a banquet, from which drink could be decanted into smaller vessels or drinking cups.

On the tomb murals of the Yuan, we can often discern the placement of wine vessels, testifying to their status and central role. On the mural in the Yuan tomb at Dongercun, Pucheng county, Shaanxi province, a couple in Mongol dress - Zhang Andabuhua and his wife, Li Yunxian - are seated in front of a screen, with wine tables on either side of them arrayed with a variety of vessels, mostly for wine. A large guan jar and cover in red is displayed on one side, together with a vase of flowers, a tall-stemmed gold-coloured stem cup and a dish: here the guan jar seems to serve a triple purpose of functionality, ritual and flamboyant display, fulfilling all three by its large and striking nature (fig. 20).

As this present jar is part of a very select group, extrapolations regarding the intended consumers are difficult. However, it is significant that no similar examples exist in the wellknown collections of Yuan porcelains exported as part of trade or tribute to the Middle East, now in the collections of the Topkapi and the Ardabil Shrine (most of the latter in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran). Two of the examples, the one in the British Museum and the other in a private collection, are likely to have been exported from China to the West in the early twentieth century. The excavated pair, found in Baoding, Hebei province, in northern China, perhaps offer a few more potential clues as to their original owner and use. For a discussion of this refer to Guo Xuelei, op. cit. The author believes that the vessels in the Baoding hoard, including the blue- and red-glazed pair of guan , with their sophistication and innovation, represent the very best of Yuan porcelain and as such, they would have been made as a court commission. The part of Baoding in which they were found was apparently, during the Yuan period, an area which housed many officials. The suggestion is that the jars belonged to the well-documented, high-ranking Minister Yuelubuhua who had been based in Baoding and who, it was recorded, was presented with four wine containers, as part of an imperial gift for services rendered.

31 During a period of subsequent unrest in Baoding, the Minister and his family left the city a month before it fell (twentieth year of Zhizheng, corresponding to 1360) and the implication is that these were the buried treasures they could not bring with them. 32

Museum, Zhuzhou

In any event, it is likely that this group of jars were part of a special commission, made to order for a specific patron or patrons and thus produced in very small numbers. They were probably an imperial commission or commissioned at the highest level, rather than made for export purposes or for gifts to foreign courts. The discovery of the pair in the Baoding hoard, suggests that those two may have been given as an imperial gift to an elite high-ranking Mongol official or family member.

Conclusion

This rare jar is part of a small group that testifies to the ambitious and cutting-edge nature of Yuan porcelain. The sophistication of their production suggests that this jar, and its companions, must have been created when the potters’ skills in these areas had matured, a certain highpoint when they had mastered all the techniques discussed above, somewhere in the second quarter of the fourteenth century.

It may be argued that the different techniques and achievements – the use of a modified porcelain body, the combined use of painted underglaze cobalt-blue and underglaze copperred decoration, with applied relief elements using moulding, carving, incising, beaded borders – may not, individually, have been innovative or new in themselves. Some had been used in previous periods and at different kilns. However, the daring and the genius of the Yuan potters, with the relative creative freedom and enterprise afforded under the Mongol regime, was to combine all of these in one single, striking object and to achieve all these different technical requirements with extraordinary aplomb.

Notes

1 For publication and further details on the jars, refer to number 2 in the present catalogue.

2 Joseph Needham, Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood, Science and Civilisation in China , Chemistry and Technology , Part XII: Ceramic Technology , volume 12, Cambridge, 2004, page 186. ³ Ibid.

4 Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China , Alien regimes and border states, 907 - 1368 , volume 6, Cambridge, 1994, page 470, where it is explained that Khubilai Khan (r. 1260 - 1294) ‘offered numerous privileges, including exemptions from most taxes to craftsmen but made corresponding levies on their time or on their production.’

5 Peter Y. K. Lam, ‘ Dragons on Yuan Blue and Whites: As Seen from the Bands on the David Vases ’ in International Symposium on Yuan Blue-and-White Porcelain , volume 1, Shanghai, 2012, page 132.

6 Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes , Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation , London and Philadelphia, 1999, page 58.

7 Jessica Harrison-Hall, Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum , London, 2001, page 52.

8 Wood, op. cit., pages 61 - 62.

9 See for instance, Rosemary Scott, ‘ Qingbai Porcelain and its Place in Chinese Ceramic History ’ in Stacey Pierson ed., Qingbai Ware: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties , London, 2002, page 11.

10 The king had elaborate mounts applied and it was presented as a gift to Charles III of Naples. Subsequent owners included the Duc de Berry, the Dauphin, son of Louis IV and William Beckford of Fonthill Abbey. See Laurie Barnes, ‘Yuan Dynasty Ceramics’ in Li Zhiyan, Virginia L. Bower and He Li ed., Chinese Ceramics from the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty , New Haven and London, 2010, pages 366 - 368.

11 Sherman E. Lee and Wai-Kam Ho, Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279 - 1368) , Cleveland, 1968, catalogue numbers 108 - 111a and b.

12 Wang Qingzheng ed., The Complete Works of Chinese Ceramics , Yuan (2) , volume 11, Shanghai, 2000, number 122.

13 Lee and Ho, op. cit., catalogue numbers 24 - 26, 28. Also exhibited (catalogue number 29) was a qingbai tiered pagoda base or possible stand for a sculpture.

14 John Ayers, ‘Buddhist Porcelain Figures of the Yuan Dynasty’, Victoria and Albert Museum Yearbook , I, 1969, pages 97 - 109.

15 Denise Leidy, ‘Qingbai Buddhist Sculpture’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society , 2016 - 2017, volume 81, pages 111 - 122.

16 Palace Museum ed., Porcelains of Yuan Dynasty Collected by the Palace Museum I , Beijing, 2016, number 90.

17 Shane McCausland, The Mongol Century , Visual Cultures of Yuan China , 1271 - 1368 , London, 2014, pages 66 - 67.

18 James C. Y. Watt, The World of Khubilai Khan , Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty , New York, New Haven and London, 2010, page 103.

19 Needham, Kerr and Wood, op. cit., pages 563 - 564.

20 Barnes, op. cit., page 355.

21 Yang Houli and Wan Liangtian, ‘Jiangxi Fengcheng xian faxian Yuandai jinian qinghua youli hong ciqi’ (Yuan Dynasty Underglazed Red Porcelains with Blue and White Decoration Discovered in Fengcheng, Jiangxi) in Wenwu , volume 11, 1981, pages 72 - 74.

22 Zhang Bai ed., Complete Collection of Ceramic Art Unearthed in China , Jiangxi , volume 14, Beijing, 2008, number 93.

23 Harrison-Hall, op. cit., pages 68 - 69.

24 Needham, Kerr and Wood, op. cit., pages 676 - 680.

25 Ibid. for a full discussion of this topic. The authors point out that the extended trade routes across the Mongol empire was ‘encouraged’ and would have offered opportunities for ‘trade in cobalt during the Yuan period.’

26 Anne Gerritsen, The City of Blue and White , Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World , Cambridge, 2020, page 67.

27 Needham, Kerr and Wood, op. cit., pages 191 and 201.

28 Watt, op. cit., pages 273 - 277.

29 Shi Ching-fei, Experiments and Innovation: Jingdezhen Blue-and-White Porcelain of the Yuan Dynasty (1279 - 1368) , D. Phil thesis, Oxford, 2001, pages 71 - 76.

30 Refer to Guo Xuelei, ‘Baoding Yuandai Jiaocang zhuren ji xiangguan wenti de tansuo’, (A Probe to the Date and the Owner of Baoding Hoard: the Character of the Porcelains Excavated from Baoding Hoard and those of the Tombs of Important Ministers in Early Ming), in Shanghai Museum ed., Splendors in Smalt: Art of Yuan Blue-and-white Porcelain Proceedings , volume II, Shanghai, 2012, pages 170 - 178.

31 The author suggests that the other two wine vessels were the pair of meiping vessels found in the hoard.

32 Guo Xuelei op. cit., pages 182 - 192.

Select bibliography

Ayers, J.: ‘Buddhist Porcelain Figures of the Yuan Dynasty’, Victoria and Albert Museum Yearbook , I, 1969.

Franke, H. and Twitchett, D.: The Cambridge History of China, Alien regimes and border states, 9071368 , volume 6, Cambridge, 1994.

Gerritsen, A.: The City of Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World , Cambridge, 2020.

Guo Xuelei: ‘Baoding Yuandai Jiaocang zhuren ji xiangguan wenti de tansuo’, (A Probe to the Date and the Owner of Baoding Hoard: the Character of the Porcelains Excavated from Baoding Hoard and those of the Tombs of Important Ministers in Early Ming), in Shanghai Museum ed., Splendors in Smalt: Art of Yuan Blue-and-white Porcelain Proceedings , volume II, 2012.

Harrison-Hall, J.: Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum , London, 2001.

Lam, P. Y. K.: ‘Dragons on Yuan Blue and Whites: As Seen from the Bands on the David Vases’ in International Symposium on Yuan Blue-and White Porcelain , volume 1, Shanghai, 2012.

Lee, S. E. and Wai-Kam Ho: Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279 - 1368) , Cleveland, 1968.

Leidy, D.: ‘Qingbai Buddhist Sculpture’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society , 2016 - 2017, volume 81.

Li Zhiyan, Virginia Bower and He Li ed.: Chinese Ceramics from the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty , New Haven and London, 2010.

Liu Jincheng: Gao’an Yuandai jiaocang ciqi (The Porcelain from the Cellar of the Yuan Dynasty in Gao’an), Beijing, 2006.

McCausland, S.: The Mongol Century, Visual Cultures of Yuan China, 1271 - 1368 , London, 2014.

Needham, J., Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood.: Science and Civilisation in China, Chemistry and Technology, Part XII: Ceramic Technology , volume 12, Cambridge, 2004.

Palace Museum ed.: Porcelains of Yuan Dynasty Collected by the Palace Museum I , Beijing, 2016.

Pierson, S. ed.: Qingbai Ware: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties , London, 2002.

图1a 元代,约1320-1352年,青花 釉里红大罐,高33厘米,大英 博物馆藏,伦敦苏富比1933年 4月25日

图1b 同图1a为同一大罐,大维德基 金会©The Trustees of the British Museum

图2

元代,约1320-1352年,青花釉里红大罐,加 盖通高41厘米,1964年于河北保定出土,现藏 于北京故宫博物院

图4

元代,约1320-1352年,青花釉里红大罐,高 34.3厘米,私人收藏

图3

与图2为一对,高42.3厘米, 现藏于石家庄 河 北博物馆

图5

元代,约1320-1352年,青花釉里红大罐, 高33厘米,本图录中第二号展品

元代瓷器的创新与变革–论青花釉里红大罐 王嘉慧

前言

这件珍罕的元青花釉里红镂雕大罐彰显了元代(1271-1368年)瓷器的高度发展与大胆 创新。同属该类元代罐器物目前世间仅存五件,其中三件现藏于博物馆中。细观此罐, 造型丰满浑厚,青花 、釉里红及镂雕三种不同的装饰工艺相交辉映。本文将以这一系列 元代大罐及其背后的史实为本,展开讨论元代瓷器中的制作工艺 、使用以及传承。

一组大罐

如上所述,这组著名的元代大罐,均通体以青花釉里红为饰,腹部四面堆塑双菱形串珠 开光,以釉里红绘山石 、花卉 、青花绘花叶。肩部绘下垂如意云头纹,云头纹内绘青 花水波纹托白莲。近底处绘卷草纹及莲瓣纹 。 1 其中一件曾于1933年伦敦拍卖售出,为 东方陶瓷学会创始人之一 S. D. Winkworth (1864 - 1938年) 的旧藏,之后被大维 德爵士购入,现作为大维德爵士基金会的一部分展出于大英博物馆中(图1 a 及图 1b )。

另,1964年河北省保定市永华南路发现类似的一对大罐,并附狮钮伞形盖。这个窖藏中 共有11件器物,包括两件梅瓶,一件玉壶春瓶,一件执壶及钴蓝釉瓷器等等;这两件大 罐其中一件藏于北京故宫博物院(图 2 ),另外一件现藏于河北省博物馆(图 3 )。这组 大罐中的第四件于1972年在伦敦拍卖,被日本古董商坂本五郎购入,之后在2002年又于 香港再次拍卖,由埃斯肯纳齐购入,现为私人收藏(图 4 )。这次展览中的大罐为这著 名系列中的第5件,原为比利时私人(后为弗拉芒)旧藏(图5 ,图录2号 )。

元代陶瓷的创新

这件大罐及另外著名的四件例子,足以证明元代瓷器令人叹为观止的技术和美学高度。

从审美角度看,它体现了本文认为那个时代应有的一切特征:奔放自由的装饰,密集繁 複的图案和别出心裁的立体设计,另外,在拉坯时巧妙的将几个部分塑在一起组装出如 此硕大的罐体的新技术,也是瓷器发展史上一个重要创新,类似的技术在世界各大博物 馆藏大件元青花器中亦可见一斑。

元初约1278年,浮梁磁局设立于景德镇,为承造大都宫廷用器的造作机构,由其大使及 副手掌管督导,同时兼“漆造马尾棕藤笠帽等事”。 2 元初百纳海川,有来自中亚或伊斯 兰西部的官员们,磁局的第一任大使是尼泊尔裔,后期陆续有来自包括波斯和蒙古的继 任 。 3

在蒙元宫廷统治下的优秀匠人们地位举足轻重,他们经常被调往帝国的不同地区,进而 促使了不同区域的材料和技术的相互交汇,景德镇的制陶工大多是自由身,一旦完成了 皇家订单的任务,便可回到民窑中继续劳作 。 4 学者 林业强 认为浮梁磁局严格控制了瓷 器的制作原料,根据元孔齐在《至正直记》(著于1363年)中所记载: “ 饶州御土,其色 白如粉垩,每岁差官监造器皿以贡,谓之 御土窑'烧罢即封,土不敢私也 ”5。可见景德 镇的陶工们并非编制,接到上面委命则陶作,但也会接受私人定制。景德镇一项最大的 创新是在公元 1330年左右引入了 以钴蓝生成的釉下彩装饰手法,这显然是受到了波斯青 花的影响。与此同時,亦或更早,景德镇的另一项创新是引入釉里红技术。这种在透明 釉下绘画的技术得益于 14世纪早期景德镇的一些 技术性变革。其中之一就是二元配方, 即引入高岭土並将其与传统瓷石按照比例配置之后混合使用,例如宋代(960 - 1279 年)的青白瓷。这不仅增加了陶工可用的原材料量,还允许“通过改变粘土与石粉的比 例来调整瓷胎以适应窑炉温度的变化。”

6 这样的坯体可以耐高温,并生产出更细致且坚硬 的瓷器。高岭土和瓷石的这种组合被称为“御土 ”,如上 文所述 。 7 为了适应釉下绘画的 要求使图案更加清晰可见,景德镇也调整了釉料的配方。据 伍德 (同上)所述,它的“外 观和成分”恰好介于流动性的青白釉和失透状的枢府釉(见下文)之间,景德镇中石灰 碱釉的配方使用约 10-20% 的釉灰 。 8

元代青白釉

在元代景德镇诸多白釉种类中,青白釉与这件大罐的密切联系显而易见,此罐通体施 青白釉,腹部四面堆塑双菱形串珠开光。另一种元代白瓷的釉层略厚,被称为“卵白” ( 也被称为“枢府”和“太禧”瓷,以器物上定烧的文字为名),可能为官用或祭祀 所用。

自宋代起,景德镇窑便凭借烧制精美的青白瓷闻名于世,其中湖田窑是青白瓷的主要 产地,其中很多设计以银器为模本,盛产碗、盘和其它器皿。青白瓷在元代对外贸易 中占很大比例。元人尚白,蒙古宫廷对白瓷的偏爱可能是青白瓷在元代持续流行的一 个因素 。 9

和本罐颇有渊源的一组青白釉瓷器,均饰菱形串珠开光并内有镂雕花卉。其中最广为人 知的是丰山瓶,现藏于都柏林的国立博物馆(图6)。此瓶是最早进入欧洲的瓷器并有 著录:1338年由元代景教与教皇本笃十二世(1344-42年在位)互通的使节过境时,赠 予匈牙利国王路易大帝(1342-82年在位) 。10

此件玉壶春瓶通体施冰蓝色青白釉,周 身饰四个串珠纹开光花卉纹。大英博物馆藏一类似玉壶春瓶(图7),维多利亚及阿尔 伯特博物馆亦藏有一件周身饰八处开光的玉壶春瓶,但花卉纹的种类略有不同 ( 图8)。

类同装饰的青白釉瓷器也可见于梅瓶,高足杯和瓷枕 。11 类似装饰在卵白釉器物上也偶 尔可见(图9)。12

宗教造像亦是青白窑中一个显著发展的代表,元代延续了大型佛教和道教的塑瓷造像传 统,其中以观世音菩萨最为流行(图10)。这组流传有序的造像做工精美,身着精致的 珠链,类似上文中讨论的玉壶春及元代大罐的连珠装饰。1968年那场著名的克利夫兰展 览中群星璀璨,包括芝加哥菲尔德自然历史博物馆藏文殊菩萨像、里特贝格博物馆藏菩 萨像、皇家安大略博物馆藏释迦牟尼佛像;堪萨斯城纳尔逊·阿特金斯博物馆藏水月观 音 , 其铭文对应的年份为 1298年或1299年 。 13 同样值得注意的是纽约大都会艺术博物馆 藏观音像,身着串珠,腿上披着串珠“围裙”。这些佛像上精致的珠宝和串珠与汉藏鎏 金铜佛像上的装饰珠宝如出一辙。例如,约翰·艾尔斯 (John Ayers) 曾总结道,这 些佛像上的“珠宝和串珠工艺简洁精致……这些装饰物的母本应是金银器 ……”14 丹尼 斯·莱迪 (Denise Leidy) 进一步阐述道,大都会艺术博物馆藏的这尊佛像,其衣着 和饰品不同寻常,“反应了青白窑对当时佛教修行演变的呼应 ”。15 北京故宫博物院还藏 有另一尊观音坐像,其胸饰和衣裙也与汉藏佛像有异曲同工之妙 。16

综上所述,引述例子中的诸多细节和此罐的关系显而易见,但其中的技术细节还需展开 讨论。此罐的开光背板在拉胚的时候被制成悬空的,可见同一组中的另外几件也如出一 辙。开光内的花卉和赏石可能为模具分段压制而成,并以手工刻画卷叶,脉纹等细枝末 节,然后组合在镂空开光上,浮雕和镂空之间的相互映衬,形成了错落有致的视觉效 果,青花和釉里红穿插在纹饰上,并施一层透明釉色。连珠部分也可能是整条以模具制 成,元代瓷器中的装饰通常华丽繁复,串珠元素常常如分水岭般凸显视觉上的留白。

尽管很多细节难以确定,但青白瓷和金银器之间的一脉相承是毋庸置疑的。此罐的浮雕 装饰和连珠元素相较于金银器上的连珠纹理(图11),亦或佛造像周身的串珠都如出一 辙。元代最著名的尼泊尔艺术全才阿尼哥(1244-1306年)以其铸造佛像为世人所熟 知。17 1273年他被任命为诸色人匠总管府总管,1278年他已成为元朝的总工程师,统领 所有帝国内的所有工匠们 。18

不难想象这些身着华丽串珠的青白釉佛造像从阿尼哥的风 格中汲取了灵感,但这些铸造佛像和瓷造像上串珠本身的具体材质不得而知,或许为传 统的佛珠,又或为珍珠。那个时代的珍珠尤为珍贵,颇受元代宫廷的青睐,可参见台 北故宫博物院藏元帝忽必烈(1260-1294年在位)后像,高耸的姑姑冠配以多串珍珠头 饰,彰显其尊贵身份(图12)。

元代釉里红

此罐别出心裁的一大亮点是在青花的基础上同时采用釉里红作为装饰元素,对铜红料出 神入化的控制体现在开光中的花卉和山石图案上。

早至1310年-1320年左右,在釉下施以铜红料的装饰技术就已经出现在景德镇,甚至可 能比钴蓝的青花时代要更早一些 。19 铜是一种难以掌控的原料,尤其在高温烧制下容易 渗入釉中,继而呈现泛灰或者黑红色,但因其颜色艳丽,历史上的各种窑口对铜都有广 泛的使用,比如唐代湖南长沙窑等。元金时期(1115-1234年)的河南钧窑以含铜的釉 料直接涂于在胎体上,经烧制之后即‘出窑万彩’。一件早期釉里红双叶纹石纹碟出自 韩国新安沉船的发掘,这艘于1323年前往日本博多港进行贸易的海船上共出水了20661 件陶瓷器,以景德镇 、吉州窑和龙泉窑青瓷居多,并没有发现青花器。

1980 年江西省高安市出土一批元代窖藏,约239件,其中67件来自景德镇。这些瓷器很 可能是在1341年至1351年左右的战乱时期被掩埋的 。 20 除了青花梅瓶和大罐等典型器之 外,仅有四件釉里红瓷器,包括高足杯、芦燕纹匜和花鸟纹大罐。后者现存于高安博物 馆并与本文讨论尤为相关,此罐高24厘米,主体绘有四个菱形开光,内饰格式花卉花鸟 纹,四开光之间点缀灵芝云纹,与此次展览中的大罐纹饰相似。此处釉里红呈色鲜艳, 层次清晰,实为难得(图13)。

图6

元代,丰山瓶,景德镇青白釉 瓷,高29.1厘米,都柏林爱尔兰 国家博物馆藏

图9

元代,卵白釉高足杯,景德 镇,高12.7厘米,扬州出土, 现藏于扬州博物馆

图7

元代,青白釉瓶,景德镇,高 27.5厘米,© The Trustees of the British Museum

图10

元代,十三世纪晚期–十四世纪 早期,青白釉观音坐像,高67.0 厘米

图11

辽代(907-1125),鎏金棱形银盘,长19.9 厘米,内蒙古通辽出土,内蒙古自治区文物考 古研究所藏

图8

元代,青白釉八方瓶及后配德国 鎏金镶嵌,高27.8厘米,伦敦维 多利亚及阿尔伯特博物馆藏

图12

元代,元帝后像,设色绢 本,61x47.6厘米,台北故宫博物 院藏

图13

元代,釉里红开光花卉纹大罐,高24厘 米,江西省高安出土,高安博物馆藏

图15

元代,1338年,青花釉里红瓷仓,高29.5 厘米,江西省丰城出土,江西省博物馆藏

图17

元代,鎏金银发簪,长16.2厘 米,株洲博物馆藏

图14

元代,1338年,青花釉里红灵塔式盖罐,高22.5厘米, 江西省丰城出土,江西省博物馆藏

图16

元代,云肩,通长70厘米,北京故 宫博物院藏

图18

元代,大漆盘,长33厘米,2001年由Friends of Asian Art以Douglas Dillion之名捐赠,纽约大都会 艺术博物馆

1974年在江西丰城县出土的元代官 员凌氏墓中出土了一组数量稀少但意义重大的瓷器, 现藏于江西省博物馆,共四件均饰釉里红,其中两件以青料楷书写 ‘ 至元四年 ’(1338 年)。21 其中一件是灵塔式盖罐,罐上刻有四方神兽高浮雕,盖上饰有双珠边,顶部有 佛塔(图 14)。22 在这件罐上仅高浮雕部分使用了釉里红装饰,以示点缀。瓶颈部十二 字,肩部七字。同在墓穴出土的还有一件青花釉里红瓷仓(图15),为仓亭阁式,气势 雄伟,仓顶是庑殿重檐顶,红柱上的瓦以釉里红点彩串珠组成。楼上有众多乐者舞者, 吹弹歌舞。正面以青花书写对联,两侧文字分别以釉里红书写。墓葬中还发现两位手持 笏板的官员像,其官服上也点饰釉里红。

上述两件器物因有明确纪年,外加青花和釉里红的合璧生辉,成为了烧瓷技术上的里程 碑。尽管这几件出土器物上的青花和众所周知明亮浓郁的元青花有些出入,但不可否认 它们与这组著名元代大罐之间有着千丝万缕的联系。值得玩味的是,两种釉下彩在这些 器物上的出现比例中,钴蓝远少于铜红,并主要局限于铭文部分。类似的装饰风格也 出现在另外一批用于宫廷的元代瓷器中,包括带有模印装饰的盘和高足杯,其内里为青 花,外部为深色釉里红,这批瓷器中所有的器物均里外分明,各执一色。23

元青花

举世闻名的青花瓷始于元代的景德镇。大约在1330 年,这里的陶工开始使用钴蓝绘制 纹样,烧制之后成品蓝白相映,晶莹明快。已知最早的例子是现藏于大英博物馆中的大 维德花瓶,其颈部的铭文明确的指出花瓶产于元至正十一年,即公元1351年,因此又得 名 “至正瓷” 。元代瓷器上使用的钴料一直被 认为是锰含量极低的高铁钴,这些富含铁 质的钴矿来源仍是一个有争议的话题,但蒙古帝国开放的对外贸易政策让人们有机会接 触到中东和伊利汗国波斯地区的钴料,这些钴料在当地已被广泛使用,而中国不同地区 的官员的存在也使这一过程成为可能。24 不过, 柯玫瑰及奈杰尔·伍德 指出:“元代景德 镇钴料的常见来源是波斯的卡姆萨尔地区(靠近卡尚),儘管这种说法在成分和历史上 都一定根据,然而这种矿物材料的产地并不尽在波斯。”25 在此之前,彩绘并非景德镇瓷器的显要特征。有观点认为,高温瓷器上的彩绘技法以 及技艺高超的工匠可能来自附近的窑口,例如江西省的吉州窑。Gerritsen (同上)认 为“釉下绘画和书法技术……通过附近的陶瓷重镇吉州传入景德镇。吉州陶工又从北方 的重要陶场(统称为磁州窑)借鉴了这种釉下彩绘技法。”26 然而,景德镇关于钴的用法 和其它窑场有所差异,他们大多以奶油色为底色,并用铁料绘深色纹饰,也鲜明生动, 独树一帜。

精美绝伦的彩绘装饰技术是如何在景德镇生根发芽的,本文不得而知。元代之前的景德 镇几乎从未使用过这种技术,意味着陶工不仅从其它窑场中汲取灵感,还借鉴了书籍、 其它品类装饰艺术和木版印刷等作为参考,这些书的元素在一些绘有人物故事的器物上 亦可见。由于 “瓷器数量和设计的订单来自将作院”,可见官方纹样来源全权源自将 作院,大有可能直接出自作院直属画院中的宫廷画家。本罐纹饰具有典型元代瓷器特 征。27 肩部饰 “云肩” 般的如意云头纹,内绘水波纹托白莲,是元代陶瓷、刺绣(包括 宫廷服饰和皇家帐篷)以及装饰艺术的显著特征(图16)。屈志仁(同上)认为该设计起 源于东汉,是“铜镜钮底周围的四叶图案或漆盒盖环周围的装饰纹样 ”。他认为 类似设 计在丝绸之路沿线地区的丝织品中也可见,辽代金属器中重新出现的时间可追溯到公元 10世纪左右。与保定窑 大罐如出一辙,此罐的每个云状领口处都有流苏,和绣品纹样有 异曲同工之妙。28

类似图案常见于在元代瓷器上,包括连枝牡丹、波浪纹和莲池;其中 莲池作为佛教元素也是元代瓷器上流行的主题之一,于汉代(公元前206年-220年)随 佛教传入中国。

本罐上的菱花形连双珠开光元素格外引人注目,繁缛精美的设计完美地定义和构建出了 典型元代的装饰风格,它们几乎遍布了元代金器(图 17)、漆器(图 18)、建筑和其 它装饰艺术,在元代视觉语言中有着举足轻重的地位。同时,它们在当时的釉下彩瓷器 中也十分常见(图 19),以此罐为例,开光外缘以珠点相连双连,强调了花卉和山石 的构图,这种新颖的组合后来经常用于瓷器上。从美学角度来看,云肩和菱花形开光的 功能性是元代瓷器繁缛设计中的必要产物,可以有效的分割过于繁密的图案,相较更为 工整的直线条边框,这两种图案化平添了视觉上的趣味和美感。

实用价值

如此一件珍罕重器,它当时为何人所用且如何用,着实令人寻味。元人尚饮风习之炽 烈,首推宫廷为最,以至当时 “中央政府颁布了一项禁止此类奢华宴会的法令”, 其中

提到 “上层和中层家庭”只能享用两到三道菜肴, 和 “ 限量的酒。”29 事实上,宴饮之风 是蒙古精英生活及其庆典的一个特点。

蒙元宫廷在宴飨和祭祀中热衷使用金银器和白瓷;其中酒器之奢,令人咂舌。各式精致 的酒器反映了饮酒礼仪的繁文缛节,其中加温、斟酒,饮酌都有其对应的器皿。以高足 碗和高足配底盘来饮酒在元代十分走俏。倒酒器则以执壶和玉壶春瓶为主,另,甑也颇 为常见,这种器皿显然具有加温和盛酒的双重用途,一石二鸟。酒罐往往形制硕大,梅 瓶和本例中的大罐皆为首选。这两种器型最初的设计都附有盖子,以防止酒精蒸发。30 它们很可能被用来在宴会上储存佳酿,然后再倒入较小的容器或酒杯中酌饮。

酒器在元代墓葬壁画中的醒目摆放位置,彰显其核心地位。陕西省蒲城县洞耳村的元代 墓葬壁画中,身着蒙古服饰的张按答不花和他的妻子 李 云线堂中对坐,两侧酒桌就摆 放着各种器皿,多为酒器。可见一件红釉大罐及盖,时令鲜花、一件金色高足杯和一盘 子:此大罐子似乎兼具实用、礼仪和装饰的三重功能,硕大且庄重(图20)。

元青花存世极少,这组大罐曾经的主人们是何方神圣,有待考究。纵观目前收藏元青花 最丰富的机构,一为土耳其托普卡比宫,另一个是阿尔达比勒神殿(后者大部分收藏在 伊朗巴斯坦博物馆,德黑兰),其中藏品大多为出口贸易的产物,其中并无类似本罐例 子。另外两例,一件现存大英博物馆,一件属私人收藏,很可能是在20世纪初从中国 流出。这或许可以对河北省保定市出土大罐的来龙去脉提供更多线索,有关这方面的讨 论,请参阅郭学雷的文献。作者认为,保定窖藏元瓷,以其复杂考究和新颖独特的创 新,代表了元代制瓷的最高水平,应为宫廷特制。元代保定路是京畿重地,有众多官员 的居所,有观点认为这些大罐属于一位有据可查的重臣月鲁不花,他曾驻扎在保定路, 据载,他曾被 “ 赉上尊四 ” ,即被赏赐了四件上等的瓶罐所装美酒。31 在保定随后的动 乱时期,这位大臣携其家眷在城市沦陷前一个月(至正二十年,即 1360 年)离开了这 里,意味着这些窖藏或是他们深埋地下的御赐之物。32

综上所述,这组产量稀少的大罐很可能是来自最高统治者的定制,应为皇家委托或御赐 之物,而并非为出口或馈赠外国朝廷。保定窖藏中发现的这对大罐极其可能是作为赐赉 瓷赠予蒙元重臣或皇室成员的。

结论

元代青花釉里红数量凤毛麟角,这件珍罕的大罐无疑是元代陶瓷雄心勃勃的缩影和佐 证。其制作工艺的精湛成熟证明这些在活跃在十四世纪下半叶的匠人们已经掌握了上述 所有技法,这件大罐显然是当时制陶技艺登峰造极的产物。

有人可能会说,改良瓷胎的使用、青花和釉里红的巧妙组合、绘、镂、塑、模印、贴等 多种技法 这些不同的技术本身并非完全创新,或多或少已出现在前朝和其它窑口。然 而在蒙元政权赋予的创作自由中,元代工匠史无前例的将所有元素集于一器,在天时地 利人和下终成大器,可谓前无古人,是陶瓷史上意义非凡的里程碑。

图19

元代,青花凤鸟纹瓶细节,高36.5厘米

图20

1269年,张按答不花及夫人李云线墓穴壁画,陕西蒲城出土

1 更多出版和其它,请参考图录中 2 号展品。

2 李约瑟, 柯玫瑰及 奈杰尔·伍德 , Science and Civilisation in China, Chemistry and Technology, Part XII: Ceramic Technology, 12 冊, 剑桥, 2004, 186页。

3 同上。

4 Herbert Franke 及 Denis Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China, Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, 6 冊, 剑桥 , 1994, 470页, 解释了忽必烈(公元 1260–1294年在位)颁布的一系列利民政策,包 括对大多数工匠减免税收。

5 林业强 , 《元青花龙纹考:以至正瓶维中心》,元青花瓷器国际学术研究讨论大会文稿(一), 上海 , 2012, 132页。

6 奈杰尔·伍德 , Chinese Glazes, Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation, 伦敦和费城 , 1999, 58页。

7 霍吉淑 , Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, 伦敦 , 2001, 52页。

8 奈杰尔· 伍德, 同上 , 61–62页。

9 见 苏玫瑰 ,‘Qingbai Porcelain and its Place in Chinese Ceramic History’毕宗陶 编 , Qingbai Ware: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, 伦敦 , 2002, 11页。

10 此瓶镶嵌金属装饰之后被赠予国王的儿子拿波里查尔斯三世,之后多次易主,拥有者包括路易十四王 太子和丰山居主人威廉 托马斯 柏克福德。见 潘筱莉 ,‘Yuan Dynasty Ceramics’, 李知宴 , 包静宜及贺 利编 , Chinese Ceramics from the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty, 纽哈芬及伦敦 , 2010, 366–368页。

11 李雪曼及何惠鉴 , Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), 克里夫兰 , 1968, 图 录 108–111a and b号。

12 汪庆正编 ,《中国陶瓷全集 - 元(下)》11册, 上海 , 2000,122号。

13 李雪曼及何惠鉴 , 同上 , 图录 24–26, 28号, 同时展出(展品29号)的还有一个青白层塔基或雕塑底座 。

14 John Ayers,‘Buddhist Porcelain Figures of the Yuan Dynasty’, Victoria and Albert Museum Yearbook, I, 1969, 97–109页。

15 Denise Leidy, ‘Qingbai Buddhist Sculpture’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 2016–2017, 81 冊, 111–122页。

16 故宫博物院编,《故宫博物院藏元代瓷器(上)》, 北京 , 2016, 90号。

17 马啸鸿 , The Mongol Century, Visual Cultures of Yuan China, 1271 - 1368, 伦敦 , 2014, 66–67页。

18 屈志仁 , The World of Khubilai Khan, Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, 纽约 , 纽哈芬及伦敦 , 2010, 103页。

19 李约瑟, 柯玫瑰及奈杰尔· 伍德, 同上 , 563–564页。

20 潘筱莉 , 同上 , 355页。

21 杨后礼和万良田,《江西丰城县发现元代纪年青花釉里红器》,《文物》, 第11辑, 1981, 72–74页。

22 张柏编 ,《中国出土瓷器全集 ,江西》, 14卷, 北京 , 2008, 93号。

23 霍吉淑 , 同上 , 68–69页。

24 李约瑟, 柯玫瑰及 奈杰尔· 伍德, 同上 , 676–680页。

25 同上,见全文,笔者指出蒙元帝国主动并全面的打开了其贸易版图以促进当时青花瓷的出口业务。

26 Anne Gerritsen, The City of Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World, 剑桥 , 2020, 67页。

27 李约瑟, 柯玫瑰及奈杰尔· 伍德, 同上 , 191和 201页。

28 屈志仁 , 同上 , 273–277 页。

29 施静菲 , Experiments and Innovation: Jingdezhen Blue-and-White Porcelain of the Yuan Dynasty (12791368), 博士论文 , 牛津 , 2001, 71–76页。

30 参考郭学雷 , 《保定元代窖藏主人及相关问题的探索》, 上海博物馆编 ,《幽兰神采:2012上海元青花国 际学术研讨会论文集》,第2辑, 上海,2012, 170–178页。

31 作者认为,另外两件酒器是窖藏中发现的一对梅瓶 。

32 郭学雷 , 同上 , 182–192页。

Blue and white porcelain from the Yuan and early Ming dynasties

盘 通 体

釉

色

莹

润 ,

隙 地 铺 满 青 花 细 线 , 犹 如 漩 涡 浪 花 , 蓝 地 白 花

菱 口 以 两 种 连 枝 花 卉

缠 绕

大 盘 尺 寸 恢 弘 , 菱 口 沉 厚 , 浅 弧 壁 , 圈 足 。 盘 心 以 深 邃 浓 郁 的 钴 蓝 绘 青 花 莲 塘 , 四 蔟 莲 花 绚 丽 绽 放 , 莲 叶 摇 曳 生 姿 。 内 壁 模 印 缠 枝 牡 丹 八 朵 , 立 体 生 动 , 俯 仰 相 宜 ,

1

Large underglaze blue porcelain dish with painted and moulded decoration

此

直 径 四 十 六 . 七 公 分

青 花 模 印 莲 塘 纹 菱 口 折 沿 大 盘 元 代 约 公 元 三 二 十 五 年 三 五 十 二 年

Yuan dynasty, c . 1325 - 1352

Diameter: 46.7cm

Large porcelain serving dish with everted, bracketed rim, rounded sides and a low wedge-shaped foot-ring. The centre of the dish is boldly painted in rich, inky, cobalt-blue tones with a pond featuring four lotus plants, each with opulent blooms, buds and large, stylized leaves, rising on slender stalks from the water. The cavetto is crisply moulded in low relief with a continuous peony scroll, reserved in white against a striated blue and white ground of waves; the eight lush blooms are each depicted from a different viewpoint and delicately outlined in blue. The rim is decorated with two types of alternating floral bands, possibly blackberry lily and aster, moulded in low relief and reserved in white on a blue ground; the edge is left white on top and painted blue around the sides. A continuous, stylized lotus scroll enclosed by double line borders encircles the exterior. The dish is covered with a transparent glaze except for the base and underside of the foot-ring which have fired to a light orange colour.

Provenance:

The family of E. T. Chow (1910 - 1980), Geneva.

Eskenazi Limited, London, acquired from the above, 18 September 1992. Hans Konrad König (1923 - 2016), Switzerland and hence by descent.

Private collection, U.S.A.

Exhibited:

London, 1994, Eskenazi Limited.

Published:

Eskenazi Limited, Yuan and early Ming blue and white porcelain , London, 1994, number 2.

Giuseppe Eskenazi with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand , The Chinese Art World through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi , London, 2012, page 296, figure 301.

Similar examples:

John Alexander Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine , Washington D.C., 1956, plate 22, number 29.129 for an example which is slightly smaller and with one continuous floral design on the rim; and numbers 29.128 and 29.123 for two related dishes, the latter also painted with a lotus pond scene, all now in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran; see also, F. Bagherzadeh et al., Oriental Ceramics , The World’s Great Collections , volume 4, Iran Bastan Museum Tehran, Tokyo, 1978, number 90, for another view of number 29.129; also T. Misugi, Chinese Porcelain Collection of Ardebil Shrine , Tokyo, 1972, page 46, numbers 16 and 17.

Regina Krahl, Early Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelain , The Mingzhitang Collection of Sir Joseph Hotung , Hong Kong, 2022, number 3 for a related example painted in the central medallion with a pair of ducks on a lotus pond.

The beautifully painted central scene of a lotus pond on the present dish is dramatically highlighted by the moulded relief decoration on the cavetto and rim, both of which are reserved in white against a rich blue ground. In particular, the striated ground of waves on the cavetto is densely but delicately rendered while the moulded flowers were perhaps given further detail by trailed slip. These Yuan dishes with relief moulded decoration on the cavetto and rim are rare, each with an individually painted and distinctive central design. A very closely related dish, painted with a lotus pond in the central medallion is in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran as cited above (Pope op. cit. number 29.129). It differs only in that there is a continual floral motif moulded around the rim, whereas the present dish has two different floral motifs on the rim. The other related dish in the National Museum of Iran (Pope op. cit. number 29.123) has reserved decoration on blue in the cavetto but does not appear to be moulded. The Hotung example, also cited above, differs in having ducks on the lotus pond. Other known variants include large Yuan dishes without moulded decoration, painted in underglaze blue with a lotus pond and with different motifs on the cavetto and rim, either with a simple rim such as the two in National Museum of Iran 1 or with a barbed rim. 2

The lotus flower is found carved and painted inside Buddhist cave temples such as Yungang and Dunhuang from the sixth and seventh century in China and at that time was closely associated with Buddhism and themes of purity. By the eleventh and twelfth centuries, both the lotus flower alone and lotus pond scenes often featured on ceramics, seen for instance on vessels from the Ding and Yaozhou kilns. The ‘naturalistic’ lotus pond motif was widely used on Yuan ceramics, either as a band encircling the body of a vessel or as a central medallion on a dish. The addition of a pair of mandarin ducks, which were reputed to be a symbol of marital fidelity, was popular. A lotus pond scene that focuses on the lotus plants, without any ducks, appears more unusual.

1 Pope, op. cit., plate 8, numbers 29.40 and 29.41.

2 Complete Works of Chinese Ceramics , Yuan, volume 11 (II), Shanghai, 2000, page 151, number 162.

内 倒 绘 宝 相 花

纹 。

罐 通 体

釉 色 明

润 ,

圈 足 沙 底 无 釉 ,

呈

米 色 ,

可

见

淡

橘 色 。

颈 部 已

被

替

花 卉 ,

Large underglaze blue and copper-red porcelain jar ( guan ) Yuan dynasty, c . 1320 - 1352

Height: 33.0cm

Large guan jar of well-rounded baluster shape with a straight, short neck, tapering to a low foot-ring with recessed base. The sides feature four ogival panels enclosed by crisp double beaded borders. Each panel is densely applied with moulded and incised decoration of four different, exuberantly flowering leafy shrubs, including peony, chrysanthemum and possibly camellia, rising from behind large, pierced rocks. The flowers and rocks are highlighted in a bright, underglaze copper red, with the leaves picked out in underglaze cobalt blue. Beneath an encircling classic scroll border, the shoulder is adorned with four large cloud collars, each with a tasselled tip, filled with lotus blooms and leaves floating on stylized waves. The cloud collars are interspersed with flowering chrysanthemum or aster branches, each positioned above an ogival panel. Squared lappets containing floral trefoils encircle the base. Above the lappets is a classic scroll band and interspersed, stylized, scrolling trefoils. The jar is covered with a transparent glaze apart from the base and underside of the foot-ring which have fired to a pale biscuit colour with an orange tinge. The neck is a replacement.

换 。 | 、 、

青 花 绘 花 叶 。 肩 部 绘 四 处 下 垂 如 意 云 头 纹 , 内 绘 青 花 水 波 纹 托 白 莲 , 云 头 之 间 绘 折 枝 牡 丹 纹 。

近 底 处 绘 卷 草 纹 及 变 形 莲 瓣 纹 , 莲

瓣 纹

各 式

Provenance:

Private collection, Belgium. Flemish private collection.

Similar examples:

There are only four other known examples of this type of jar. A selection of the publications in which the four other examples are illustrated follows below.

The guan in the Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Trust, London (formerly in the S. D. Winkworth collection), now in the British Museum, London, is published in:

R. L. Hobson, The Wares of the Ming Dynasty, London, 1923, plate 21. Sotheby’s London, Catalogue of the Well-known and Extensive Collections of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Chinese Works of Art and Fine Old English Furniture, the Property of Stephen D. Winkworth Esq., 25 April 1933, number 179.

R. L. Hobson, A Catalogue of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain in the Collection of Sir Percival David, London, 1934, page 111, plate CX.

The International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Art, London, 1935 -1936, number 1577.

W. B. Honey, The Ceramic Art of China and Other Countries of the Far East, London, 1943, plate 91.

John Ayers, ‘Some Characteristic Wares of the Yuan Dynasty’, in Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society , volume 29, 1954 - 1955, plate 39, figure 19.

The Ceramic Art of China , Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1971, number 134.

Margaret Medley, Yüan Porcelain and Stoneware , London, 1974, colour plate B.

Margaret Medley, Illustrated Catalogue of Underglaze Blue and Copper Red Decorated Porcelains , London, 1976, B661, plate XII.

Margaret Medley, The Chinese Potter , Oxford, 1976, colour plate V. Rosemary E. Scott, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art. A Guide to the Collection , London, 1989, page 70, plate 58.

Rosemary E. Scott ed., Chinese Copper Red Wares , Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, Monograph Series No. 3, London, 1992, page 21, figure 1.

Rosemary E. Scott, Elegant Form and Harmonious Decoration, Four Dynasties of Jingdezhen Porcelain , London, 1992, number 14.

Ye Peilan, Yuandai ciqi (Yuan Porcelain), Beijing, 1998, page 88, figure 155.

John Carswell, Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain Around the World , London, 2000, page 118, figure 130.

Stacey Pierson, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art , London, 2002, page 59, figure 40.

Regina Krahl and Jessica Harrison-Hall, Chinese Ceramics, Highlights of the Sir Percival David Collection , London, 2009, page 50, number 23.

The guan in the Palace Museum, Beijing (excavated in Baoding, Hebei province in 1964) is published in:

Adrian M. Joseph, Ming Porcelains: Their Origins and Development , London, 1971, page 15, figure 3.

Toji taikei (World Ceramics), volume 41, Tokyo, 1974, number 4 and page 85, figure 1.

Wan-go Weng and Yang Boda, The Palace Museum Peking , London, 1982, page 101, figure 27.

Geng Baochang ed., The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (I), volume 34, Hong Kong, 2000, page 248, number 227.

Zhang Bai ed., Complete Collection of Ceramic Art Unearthed in China, volume 3: Hebei, Beijing, 2008, number 220.

Palace Museum ed., Porcelains of Yuan Dynasty Collected by the Palace Museum I, Beijing, 2016, pages 60 - 63, number 90.

Guo Xuelei, ‘Baoding Yuandai Jiaocang zhuren ji xiangguan wenti de tansuo’, (A Probe to the Date and the Owner of Baoding Hoard: the Character of the Porcelains Excavated from Baoding Hoard and those of the Tombs of Important Ministers in Early Ming), in Shanghai Museum ed., Splendors in Smalt: Art of Yuan Blue-and-white Porcelain Proceedings , volume II, Shanghai, 2012, page 171, figure 1.

The guan in the Hebei Museum, Shijiazhuang (pair to the one immediately above, excavated in Baoding, Hebei province in 1964) is published in:

Wang Qingzheng, Underglaze Blue and Red , Hong Kong, 1987, page 39, number 23.

Zhongguo meishu quanji: gongyi meishu bian , volume 3, Shanghai, 1991, plate 38.

Liu Liang-yu, A Survey of Chinese Ceramics , volume 3, Taipei, 1992, page 180.

Hebei sheng bowuguan wenwu jingpi ji (Treasures from Hebei Provincial Museum, Beijing, 1999, plate 70.

Complete Works of Chinese Ceramics, Yuan , volume 11 (II), Shanghai, 2000, page 141, number 151.

Zhang Bai ed., Complete Collection of Ceramic Art Unearthed in China, volume 3: Hebei, Beijing, 2008, number 221.

Li Zhiyan, Virginia L. Bower and He Li ed., Chinese Ceramics from the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty , New Haven and London, 2010, page 356, figure 7.36.

James C. Y. Watt, The World of Khubilai Khan, Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty , New York, New Haven and London, 2010, page 285, figure 324.

Yuandai qinghuaci (Yuan Blue and White Porcelain), Shanghai, 2010, page 219.

Guo Xuelei, op. cit., page 171, figure 2.

The guan in a private collection is published in: Christie’s, London, Important Chinese Ceramics and Hardstones , 5 June 1972, number 156.

Michel and Cécile Beurdeley, Chinese Ceramics , London, 1974, page 169, number 95.

S. T. Yeo and Jean Martin, Chinese Blue and White Ceramics , Singapore, 1978, page 17, figure 7.

Anthony du Boulay, Christie’s Pictorial History of Chinese Ceramics , Oxford, 1984, page 107, figure 1.

Ye Peilan, Yuandai ciqi (Yuan Porcelain), Beijing, 1998, page 88, figure 156.

Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation , London, 1999, page 174.

Sotheby’s, Hong Kong, An Exceptionally Important Yuan Jar , 30 October 2002, number 270.

Giuseppe Eskenazi with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand, The Chinese Art World through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi , London, 2012, page 87, figure 80.

Other than the present example, there appear to be only four other related guan jars of this rare type, of which three are in institutional collections as cited above: the example in The Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art Trust, London, now in the British Museum and the pair excavated in Baoding, Hebei province in 1964, now in the Palace Museum, Beijing and in Hebei Museum, Shijiazhuang. The fourth example is currently in a private collection.

The present jar and its four companion pieces are very similar stylistically, with just minor variations in the decoration. The example in this exhibition is most closely related to the pair of guan jars, with covers with lion-shaped knops, discovered at Yonghua South Road, Baoding, Hebei province in 1964, in a hoard which contained some remarkable Yuan porcelain. The moulded flowers in the ogival reserves on the pair and on the present guan appear to be very similar. The painted decoration on all three jars is also very close. On the upper body, all have cloud collars at the shoulders filled with lotus flowers on a pond, interspersed with flowering chrysanthemum or aster branches; all have the lower bands of filled lappets, classic scroll and upright trefoils. The David example differs in that the large cloud collars on the shoulder are filled with flowering branches and are interspersed with smaller cloud shapes, while the neck is encircled by a half-cash diaper. The example currently in a private collection has cloud collars at the shoulder filled with flowering branches, like the David example, but is interspersed with three-point cloud motifs, below a chrysanthemum scroll at the neck.

Together, the five jars form a small and extremely rarified group, likely made for a patron at the highest level of Yuan society. They are not only unusual and visually striking, but technically would have been at the cutting edge of Yuan porcelain production, featuring the combined use of painted underglaze cobalt-blue and underglaze copper-red decoration with applied relief elements using moulding, carving, incising and beaded borders.

For a further discussion on the present jar and its companions, refer to the essay ‘Yuan Porcelain Innovation and Adaptation: An Underglaze Blue- and Red-Decorated Guan Jar’ by Sarah Wong on pages 10 - 21.

莹 润

肥

腴 ,

底

部 素 胎

无

釉 ,

呈

米 黃

色 ,

可

见

少 许

淡

橘 色

窑

渣 。

圈

足

外 侧

有

波

斯

文

丹 山 茶 花

栀 子 花

石 榴 花 芙 蓉 牵 牛 花

莲 花 桃 花 等 ,

折 沿 绘 一

周

缠

枝

莲 。

外 壁 共 绘

六 组

折 枝 莲 花 和 灵 芝 。

此 盘 通 体 青 料 妍 美 ,

3

铭 文 。 | 、 、 、 、 、 、 、 、 、- - - c- c

釉

色

Underglaze blue porcelain ‘three lotus’ dish

Ming dynasty, Yongle period, 1403 - 1424

Diameter: 37.3cm

花 形 , 撇 口 折 沿 , 浅 弧 腹 , 矮 圈 足 。 盘 心 绘 八 角 菱 形 双 框 开 光 , 内 饰 三 朵 缠 枝 莲 , 内 壁 绘 十 二 各 式 花 卉 , 计 有 菊 花 荷 花 牡

Large porcelain dish with rounded, fluted sides, barbed rim and slightly convex base, supported on a low wedge-shaped foot-ring. The centre of the dish is painted in rich cobalt blue tones with three large lotus flowers on tendrils within an octofoil panel surrounded by a double circle. The lobed cavetto is filled with twelve individual flowers including chrysanthemum, lotus, peony, camellia, hibiscus, pomegranate, tea, peony, morning glory, gardenia, peach and rose and the barbed rim is decorated with a lotus scroll. The reverse is painted with six lotus plants alternating with six sprays o f lingzhi f ungus, within line borders. The dish is covered with a transparent glaze except for the base and the underside of the foot-ring which have fired a cream colour with some orange speckling.

The exterior of the foot-ring is incised with a Persian inscription which reads:

Alamg i r Shah i

Belonging to Alamg i r Shah

Provenance:

Marchant and Son Limited, London.

Eskenazi Limited, London, acquired from the above in 1993.

Private collection, U.S.A., acquired from the above in 1994.

Exhibited:

London, 1994, Eskenazi Limited.

On loan to Denver Art Museum, Denver, 1994 - 2005

On loan to Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont, U.S.A., 2006 - 2015.

Included in the exhibition, Azure Skies and Pure Snows: Chinese Blue-andWhite Porcelains of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) Dynasties from the Rui Fang and Barbara P. and Robert P. Youngman Collections , Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont, 25 January - 9 December 2007.

Published:

Eskenazi Limited, Yuan and early Ming blue and white porcelain , London, 1994, number 12.

Similar examples:

Sotheby’s London, Fine Chinese Ceramics, Bronzes and Works of Art , 9 December 1986, number 199; also, John Carswell, Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain around the World, London, 2000, page 96, figure 99.

Tetsuro Degawa, Claire Déléry et al., Porcelaine, Chefs-d’Oeuvre de la Collection Ise , Paris, 2017, number 34 for the example from the Ise collection.

John Alexander Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine , Washington D.C., 1956, plate 33, number 29.83 for a similar dish, with a hexafoil panel.

Chang Foundation ed., Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen , Taipei, 1996, number 50 for an example with a hexafoil panel excavated at Dongmentou, Zhushan, Jingdezhen; also, Capital Museum ed., Jingdezhen Zhushan chutu Yongle gong guanyao ciqi (Yongle Imperial Porcelain Unearthed from Zhushan, Jingdezhen), Beijing, 2007, number 68.

Examples of this type of dish are rare. Of those cited above, only two, like the present example, are painted with an octofoil frame or panel enclosing the central design, while the rest have hexafoil panels. In both cases, the bracket-form panels provide a striking counterpoint to the bracketed rim. Related dishes include those with an octofoil frame enclosing three chrysanthemum sprays, such as the example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but these usually have a flat everted rim. 1

The inscription most likely refers to the Mughal emperor and patron to the arts, Alamg i r I (Awrangzib) (r. 1658 - 1707).

1 Suzanne G. Valenstein, A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics, New York, 1989, page 150, plate 145.- c

部 素 胎 无 釉 , 呈

橘 褐 色 。 | 、 、 、 、 、 、 、 、

近 底 部 绘 仿 古 纹 。 此 盘 通 体 青 料 妍 美 , 釉 色 莹 润 肥 腴 , 底

4

Underglaze blue porcelain ‘three friends of winter’ dish Ming dynasty, Yongle period, 1403 - 1424

Diameter: 32.0cm

Porcelain dish with rounded sides and flat base, supported on a low wedge-shaped foot-ring. The dish is painted in the centre in cobalt blue with intertwined branches of the ‘Three Friends of Winter’ – bamboo, prunus and pine – within a triple circle. The cavetto is encircled by a composite flower scroll with twelve main blooms, including lotus, rose, peony, morning glory, pomegranate, camellia, tea, gardenia, day-lily, mallow, hibiscus and chrysanthemum, with a wave border at the rim. The exterior is painted with a similar composite scroll of twelve blooms with a classic scroll above and a key-fret band below while the foot-ring is encircled by a single line. The dish is covered with a transparent glaze except for the base and underside of the foot-ring which have fired to a brownish-orange colour.

Provenance:

Eskenazi Limited, London.

Private collection, U.S.A., acquired from the above in 1995.

Exhibited:

On loan to Denver Art Museum, Denver, 1995 - 2005.

On loan to Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont, U.S.A., 2006 - 2015.

线 内 绘

竹 梅 , 即 岁 寒 三 友 图 , 内 壁 饰 十 二 朵 各 式 连 枝 花 卉 , 计 有 莲 花 芙 蓉 牡 丹 牵 牛 花 石 榴 花 山 茶 花 菊 花 等 , 外 壁 绘 相 似 缠 枝 花 卉 纹 ,

Included in the exhibition, Azure Skies and Pure Snows: Chinese Blueand-White Porcelains of the Ming (1368 -1644) and Qing (1644 -1911) Dynasties from the Rui Fang and Barbara P. and Robert P. Youngman Collections , Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont, 25 January - 9 December 2007.

Similar examples:

Sotheby’s, London, Catalogue of Important Chinese Ceramics with a Few Works of Art , 25 June 1946, number 19 for the example with a wave border formerly in the collection of Major Lindsay F. Hay, then formerly in the Cunliffe collection; also, Oriental Ceramic Society, Loan Exhibition of Chinese Blue and White Porcelain, 14 th to 19 th Centuries , London, 1954, number 34; also, Oriental Ceramic Society, Loan Exhibition, The Arts of the Ming Dynasty , London, 1957, number 117; also, Oriental Ceramic Society, The Ceramic Art of China , London, 1971, number 150.

John Alexander Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine , Washington D.C., 1956, plate 40, number 29.35 for an example with a key-fret border.

B. von Ragué ed., Ausgewählte Werke Ostasiatischer Kunst , Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Berlin, 1970, number 64.

John Carswell, Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World , Chicago, 1985, page 31, figure 6 for a dish also with a key-fret border, discovered in Damascus, Syria and formerly in the collection of H.E. Henri Pharaon; also, John Carswell, Blue and White, Chinese Porcelain around the World , London, 2000, page 99, figure 106. Eskenazi Limited, Yuan and early Ming blue and white porcelain , London, 1994, number 16, with a key-fret border; also, Giuseppe Eskenazi with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand, The Chinese Art World through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi , London, 2012, page 310, figure 334; also, Regina Krahl, Evolution to perfection, Chinese ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection , London, 1996, number 114; also, Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection , volume 4 (I), London, 2010, number 1640.

Geng Baochang ed., Gugong bowuyuan cang Mingchu qinhuaci (Early Ming Blue and White Porcelain in the Palace Museum Collection), volume 2, Beijing, 2002, number 131 for an example with a wave border and number 130 for an example with a keyfret border, both from the Qing court collection and dated to the Xuande period; also, Geng Baochang ed., The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Blue and White Porcelain with Underglazed Red (I), volume 34, Hong Kong, 2000, number 140 for another view of the latter; see also, Wang Liying, The Complete Works of Chinese Ceramics, Ming (I), volume 12, Shanghai, 2000, page 88, number 76; also, Palace Museum et al., Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Xuande in the Ming Dynasty , Beijing, 2015, number 19.

Daisy Lion-Goldschmidt, Ming Porcelain , London, 1978, for a smaller example.