6 minute read

Farm life

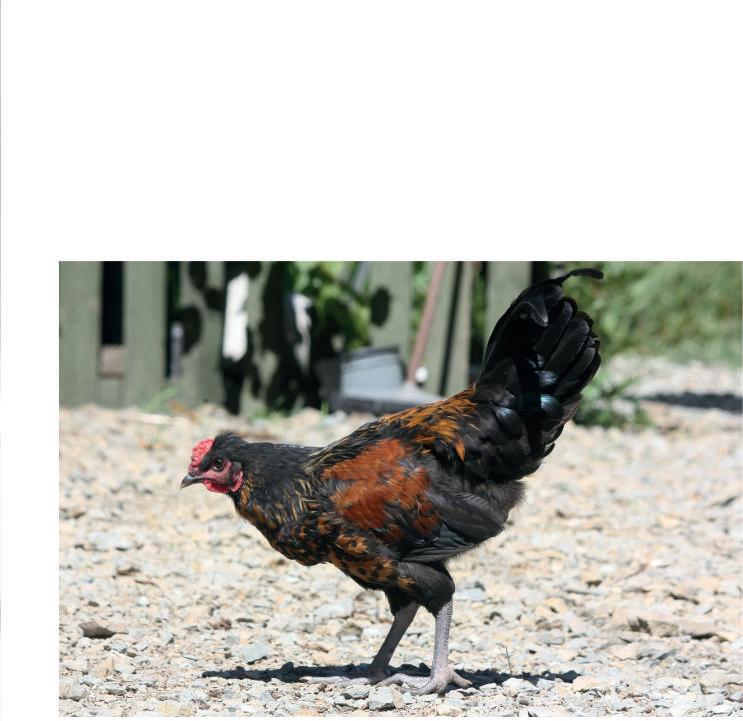

Males right and centre, female left at seven weeks old

Too Many Cockerals!

Advertisement

HATCHING YOUR OWN CHICKS? YOU’LL NEED TO BE PREPARED FOR SOME TO GROW INTO COCKERELS

Tamsin Cooper is a smallholder and writer with a keen interest in animal behaviour and welfare

www.goatwriter.com

By Tamsin Cooper

Sadly for them, too many cockerels really do spoil the flock, unless you have enough hens for each of them. Experts recommend an average of ten hens to every male. Fewer than that can lead to fighting cocks and overworked hens with tattered feathers where they are so often trodden by ardent mates. Last year, our hens hatched a few of their own chicks. Two hens each brooded five eggs. Each clutch had their own minihouse-and-run to protect them from predators. We figured that would result in four or five new hens and about the same number of cockerels. Males have a reputation for fighting; rarely can they live peacefully in a small flock once mature. However, our resident male, Pablo, is a gentle soul who lived harmoniously with his brothers until he came to us at about a year old. I had also read that brothers were more tolerant and less hostile.

First Signs of Cockerel-Hood

As some eggs turned out to be infertile, one hen hatched two chicks and the other three. Maternal hormones kicked in and each hen began to protect and teach her chicks the ways of chicken-hood: foraging, drinking, dust-bathing and perching. These skills they picked up almost immediately, and they soon began bouncing around in play and perching on low branches. Within the first couple of weeks, male chicks start running, leaping and sparring. So we could see that two of the threesome were likely to be male. It was not until the twosome were six weeks old that we recognised signs that one was a cockerel. Barbarossa we called him, as his chest was rich brown (it means “red beard”). He had very sturdy legs and small wattles and comb, as opposed to his sister, whose comb was still only just visible. But chickens develop at different rates and at nine weeks, his comb and wattles were still quite small. By this time, he was attempting to crow. Meanwhile, within the trio, one chick grew substantial wattles and comb at only four weeks old and started crowing at five. His brother had small but distinct wattles and comb by seven weeks old, while their sister had virtually none.

Rapid Early Learning

When the chicks reached four weeks old, we allowed them supervised outings, so that they could get familiar with the flock and range while under mother-hen’s protection. This meant keeping our large bouncy cat indoors while the small chicks found their way around safely. They quickly learned to use perches and bushes

Bottom, Barbarossa at 14 weeks old, when he joined the adult flock Right, Barbarossa at nine months old, when he took over the flock

as safety zones, retiring to a bush if they lost their mother, calling her with high peeps when she returned. By six weeks, the chicks became independent of mother, and no longer needed supervision. This is just as well, because mother-hen was taking little notice of them by now, laying and roosting with the adults in the big house. I had hoped they would follow her, as often occurs. However, they stuck to their infant nests until I moved them over one night, once they were fully integrated into the main flock by day. In retrospect, a henhouse large enough to accommodate closable chick-rearing pens might have worked better. The two groups of chicks first met at six and four weeks old respectively. Males were conspicuous in their behaviour: Barbarossa exchanged threats with both younger males, but the females avoided confrontation. Three weeks later, the youngsters were hanging around together peacefully and hierarchy was evident, the older cockerel being the boss and the others keeping out of his way. Meanwhile, the mothers had rejoined the flock, experiencing only a few pecks from the boss-hen and Pablo’s delighted attention. So brief is the period of motherhood and so quickly the relationship forgotten! When he was seven weeks old, Barbarossa’s brood-mother pecked him away from food, whereas just weeks earlier she was calling him to feed. However, those first six weeks had filled him with chicken-sense and a great start for a strong and healthy life.

Adolescence

At 10 weeks, the chicks started roosting during part of the night, although still apart from the main flock. They would not perch fully until they moved into the main house, which afforded more space. The less-developed male finally showed the longer legs, tail, and fuller comb and wattles of his sex. But he still didn’t crow, perhaps inhibited by his fast-maturing brother, until he was almost six months old. He and his brother engaged in long challenges, but fortunately no actual violence. Around 12 weeks, the chicks’ sweet peeps changed to adult-sounding clucks and gurgles. At this time, males tried out courtship dances towards to adult hens, who refused their advances, while Pablo intervened and chased the young rascals away. At 14 weeks, Barbarossa resolutely joined the adult flock, tolerated by Pablo and accepted by the hens. The younger male chicks stuck together, while the females became a little remote until they too joined the flock. During the next few weeks, the more mature males began to vary their calls, becoming louder and bolder, and moult into more colourful plumage. Some hens started to accept matings from Barbarossa, uncontested by Pablo. However, they clearly preferred Pablo and he would defend them if they ran to him. On the other hand, when Pablo mounted Barbarossa’s sister, the latter was quick to attack, although Pablo chased him away. By six months, the two males were still sharing the flock harmoniously, when the two younger cockerels started following one of the hens around amorously. Together they courted her, and when she finally succumbed, they both tried to jump on her at once. Of course, neither managed to mount properly, but there was no dispute, and they continued to dance and follow her together. As they started to pester more and more hens, it became clear that the flock could not take any more cockerels. Happily, we found them a caring home with flocks of their own.

Pablo’s Last Stand

The peace lasted until Barbarossa was nine months old. He is now tall, deep-chested, colourful and shiny, with a large red comb and wattles. Every inch a hen’s dream, in fact. Outshining, out-sizing, and outcrowing Pablo. One evening, the males did not come for treats, so I went out looking. I found them fighting around the woodpile. Barbarossa pinned Pablo down and tore his comb. A defeated but defiant Pablo eventually stood down and dared not enter the chickenhouse until after the others had settled. Thereafter, he avoided Barbarossa, and suppressed his crow for several days. The hens, meanwhile, nonchalantly stuck with Barbarossa. After several days, Pablo was still skulking around, and when he restarted crowing, it was with a different voice. Barbarossa chased him away from evening treats again: it was heartbreaking to see him demoted to pariah. Fortunately, a kind couple would take either male for their flock. Barbarossa was by now surrounded by hens and difficult to extract from the roost, while poor Pablo perched alone. So Pablo was collected and inherited a new flock of his own. A happy ending for him, but a lesson for us that our flock just wasn’t big enough for the both of them.