10 minute read

Nature

Fine Feathers Make Fine Birds

A male Great-tit puts all its breaks on as it comes in to alight. Note how every feather is at full streatch to bring the tiny, hurtling creature to a stop

Advertisement

WHAT ARE FEATHERS? WHAT DO THEY DO? HOW DOES A BIRD USE THEM? AND HOW DID THEY DEVELOP?

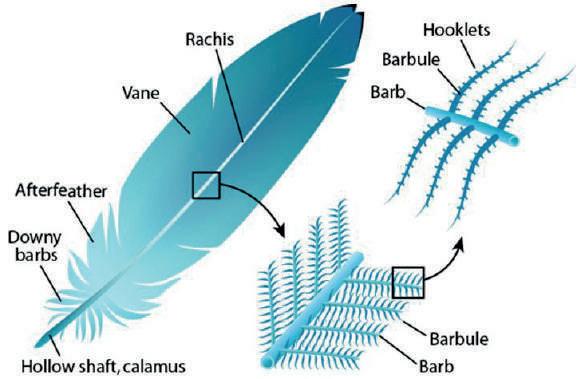

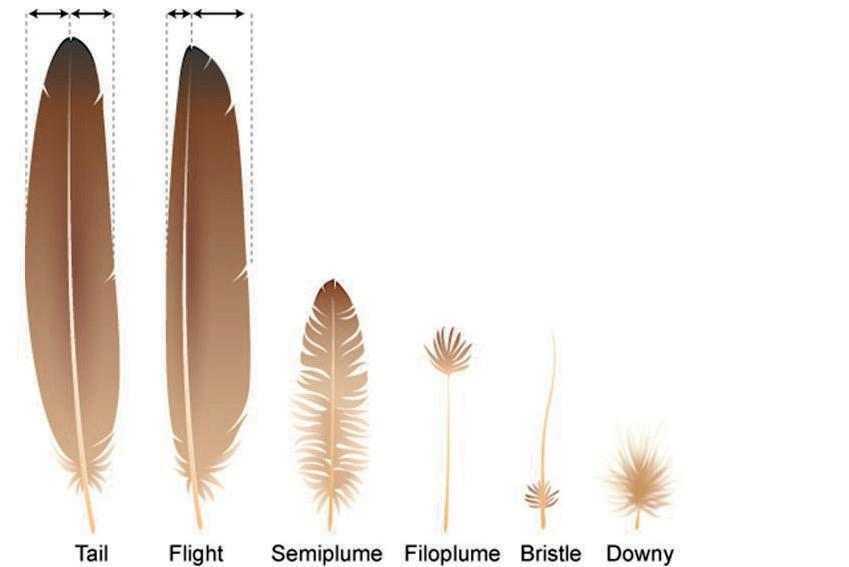

Feathers are remarkably complex birds, they found that their ability to outgrowths from the skin of a bird, catch insects was quite unimpaired! made of keratin, a stiff form of protein similar to the material that forms hair and horn in mammals, but chemically Why does a bird have feathers anyway? toughened to be even stiffer. There are That seems like the most obvious different types of feathers, but they question – they enable them to fly, of resolve themselves broadly into three course. However, that is only part of the which neatly ducked all the issues, were classes: vaned feathers (pennaceous), answer, and, as we shall see, probably seized upon both by the Darwinists and down feathers (plumaceous) and bristle was not the primary reason for growing the Creationists of the time (it was the feathers. The pennaceous feathers are the feathers in the first place. period when the new theory of Evolution ones we usually think of – one long stiff The problem is that we do not really was under hot debate). The Creationists stem (the rachis), either up the centre of know when feathers first appeared. We hailed them as proof that birds were the feather or off towards one side, from know fish had scales from very early on, created independently from other which sprout side-shoots (barbs) which because these are preserved quite well, creatures, or else where did the feathers in turn sprout finer side-shoots of their and anyway, people expect to find scales come from? The Darwinists insisted that own (barbules) all in one plane of growth. on a fish, so they looked for them when they were a transitional stage between The barbules in turn have a Velcro-like they found a fish skeleton. Feathers are reptiles and birds. Neither faction system which locks them together, more perishable, and thus less likely to be was correct. further stiffening the feather and maintaining its shape. These inevitably come slightly undone over time, but the bird can re-secure them as part of the process of preening. preserved in the fossil record, and anyway, the early fossil hunters were more interested in the bones than the other parts of the vertebrate fossils they found. Besides, they had been told that After many years of fruitless argument, someone decided to have a good, close look at the specimens (a couple more had turned up in the meanwhile). Yes, Archaeopteryx did have claws, but then Most feathers are only attached to the these were reptiles – giant lizards – and so does the Hoatzin bird of South flesh of the bird, but the feathers that do whoever saw a lizard with feathers? America (at least in its fledgling stage) the hard work are usually attached to The odd feather turned up in suitably today. The main problem was the bone as well. The flight-feathers and fine-grained rock, but not associated with musculature and the "flight" feathers. some of the tail-feathers fall into this anything else. This merely was noted as Archaeopteryx did not have the deepcategory. They need the strong giving an indication that birds were keeled breastbone, as a modern bird has, attachment to stay stable under stress. around about that time (Jurassic – a bit for the attachment of the heavy-duty What do feathers do? early, but there you are). After all, you often find loose feathers lying about flight-muscles needed to pull the wings downwards against the bird’s weight, nor Usually, it is the today. Why did the "wing" bones have evidence of the pennaceous feathers not then? insertion of such muscles. In addition, that one sees on a the large pennaceous feathers along the living bird. The Had it climbed a tree and The big wing did not insert into bone-tissue, but flight-feathers and tried to jump out, it would breakthrough came were solely inserted into flesh. Thus, the tail, of course, but also the contour feathers. These cover have fluttered in an ungainly tangle to the ground when a beautiful, almost complete skeleton of what “wings” did not have the strength to lift the bird or even to hold it in gliding flight. Had it climbed a tree and tried to jump the entire body, and was at first taken as out, it would have fluttered in an ungainly provide streamlining a Coelurosaurian tangle to the ground. More parachuting to cut down drag, but most of all provide, dinosaur was found than flying! together with the plumaceous feathers below them, a strong thermal insulation, because remember, a bird is endothermic, that is, it uses its own energy reserves to maintain its bodytemperature, like a mammal, and must therefore avoid losing heat unnecessarily. Mammals do the same (with one notable exception), but use the simpler system of hair-cover for the body. The nearest a bird gets to hair are the bristle-feathers, which usually are found on the face, around the base of the beak. Nobody is sure even now what their function is. Someone suggested they act as sensors to facilitate the catching of insects, covering the blind-spot between the edge of vision in the Solnhofen Lithographic Limestone of Bavaria, Germany, in 1861. This limestone is very fine-grained, preserves fine details and splits cleanly. The fossil was missing its head, although there were suggestions of teeth around, but the rest of the skeleton was there, and moreover, it was surrounded by the impressions of large, pennaceous feathers. Subsequently another specimen was found, complete with head, which confirmed the presence of teeth. Unfortunately, although the wing-shape was modified it still bore separate claws, not the fused finger-bones of a modern bird, it had a bony tail and long, robust legs clearly intended for running. In addition, the creature’s tail actually was a tail, with vertebrae going right down it as well as feathers. This would have caused considerable drag in flight, had flight been possible, as would the long and robust legs. So, what was this creature doing arrayed in feathers? What use were the feathers? Where did it get them? Why pretend it could fly when it couldn’t? The answer is that it wasn’t pretending anything. It never intended to fly. The feathers had a very useful purpose, which had nothing to do with flight. The one thing I haven’t told you about Archaeopteryx is its size. It was and the beak. Sadly, when experimenters These specimens, which were given the hardly larger than a crow. 'So?' you ask. shaved the bristles off some insectivorous name Archaeopteryx (ancient feather) That is bird size, what is unusual about

By Mike George

Mike George is our regular contributor on wildlife and the countryside in France. He is a geologist and naturalist, living in the Jurassic area of the Charente

Feather Types & Anatomy

All these different types of feather can form the plumage of a bird. The barbs of the flight and tail feathers must lock together to hold the aerofoil shape. The blue diagrams above show how this happens

that? When you have ruled out the possibility that Archaeopteryx was a bird, you are left with but one conclusion. It was a dinosaur! In fact, apart from its size, it is identical to several other longlegged dinosaurs, and but for the fullydeveloped feathers, which clearly mark it as an adult creature, it might have been taken for a baby Coelurosaurian dinosaur. Now, as a dinosaur, we now know it would have been endothermic, or to remind you, it generated its own body-heat internally. Other dinosaurs solved the problem of maintaining their internal heat by being big, and having a large bulk with a relatively small surface area through which to lose heat. Their problem was getting their young up to sufficient size to reach this situation. That is why the remains of dinosaur babies are few and far between – they grew so fast that they were babies for a very short time. All other things being equal, a small dinosaur could not exist! Archaeopteryx was solving this problem by insulating its body with feathers, which also allowed it to vary its insulation by moving the feathers around, as a modern bird does. It also may have needed the long feathers on its arms and tail to act as stabilisers when it ran, as it undoubtedly did, because its small body was too light to give it the low centre of gravity it needed. Also, it has been suggested that it used its feathered wings as a sort of catch-net for trapping its prey, surrounding it with a conical barrier into which it could push its head and gather the prey with ease. It almost certainly never went into a tree – equipped as it was, a tree would be the last place it wanted to be!

But where did it get the feathers?

As I say, for a number of reasons we have no idea when feathers developed. In the mid-19th century, there was surprise when a feather turned up as early as the Jurassic period, which we now know was about 180 million years ago. Now evidence suggests that feathers must have appeared even earlier, possibly in the Triassic period. Some ancestor of Archaeopteryx and its relatives acquired the ability to grow them, and probably over the millennia some odd arrangements of feathers were tried and failed. It may be that several of the Coelurosaurian species had feathers, which they will have used for warmth, for display, for protection, possibly as an aid in brooding young. Archaeopteryx was one of the experiments, and the experiment proved that, for a dinosaur, small could be beautiful, but it didn’t lead to flight. Then the trick of taking to the air was tried, and that worked. Now plenty of true birds are coming out of fossil beds in China, from the right periods, and indicating that flight evolved as might be predicted. Strangely enough, almost as soon as they had gained the ability to fly, some species of bird relinquished it. Hesperornis used its wings to swim underwater, and developed a penguin-like lifestyle. Others - the Phorosrachids or terror-birds reverted to using size as a domination technique, grew as large as some of the old dinosaurs and forfeited flight. They kept the feathers, though. So, am I saying that birds are descended from dinosaurs? Yes. Most of the dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, but one group gave rise to a new dynasty, the birds. Your garden could be said to be full of tiny dinosaurs, twittering merrily from every bush. It came as quite a shock in the early 1970s when this fact dawned on

Archaeopteryx was solving this problem by insulating its body with feathers, which also allowed it to vary its insulation by moving the feathers around, as a modern bird does. Hesperornis from the Cretaceous Period. An early example of a bird that lost the ability to fly; instead it embraced the lifestyle of the modern penguin

palaeontologists. For generations schoolchildren have wished they could see an actual dinosaur. The whole Jurassic Park franchise is built on that very wish! Well, it seems that they can. These dinosaurs have lost (thank goodness!) their astounding size, their fearsome teeth and many of the “gosh” factors that make them memorable, but they have gained the ability to fly, and that is pretty astounding. In fact, I find the whole thing amazing, and I still, especially in my older years, find myself humbled by the wonders of Nature, and the fascinating mechanisms of Creation. It is a privilege to be able to tell you about them.

Archaeopteryx, the first fossil ever found with feathers. It was, nonetheless, a dinosaur, not a bird.

Archaeopteryx had sharp teeth, three fingers with claws, and a long, bony tail