9 minute read

Generating Blood Based Diagnosis for Alzheimer Disease

Neuronal disorders are marked by changes in blood values, which can be used to improve diagnosis. We spoke to Dr Eugenia Wang about her research into developing a blood test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, work which will also offer important insights into its progression and development

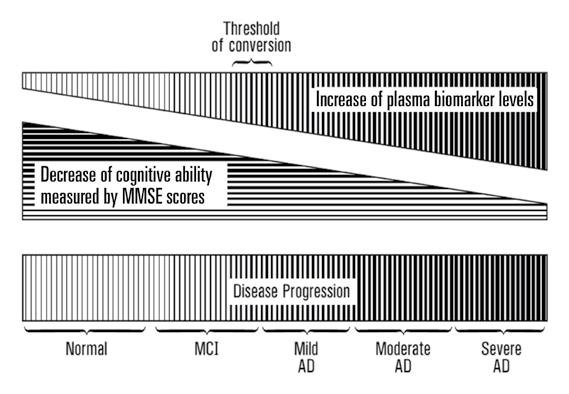

As the most common form of dementia in the world, Alzheimer’s disease is a major global health issue, and with the number of cases set to rise further as life expectancy increases, research into both treatment and diagnosis is an urgent priority. Currently the disease is diagnosed by either a neurological assessment such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE score) or an MRI scan, but now Dr Eugenia Wang is developing a test to diagnose Alzheimer’s by measuring levels of microRNAs in the blood. “microRNAs are tiny molecules that are carried in our bloodstream. Our body has what I would call our equilibrium status, but when something changes suddenly, then our body will reflect this change in the bloodstream,” she explains. Dr Wang says this change in the body’s physiology can be detected. “In the case of a disease situation you can see changes in the plasma of the blood, which are the footprint of the disease process,” she continues.

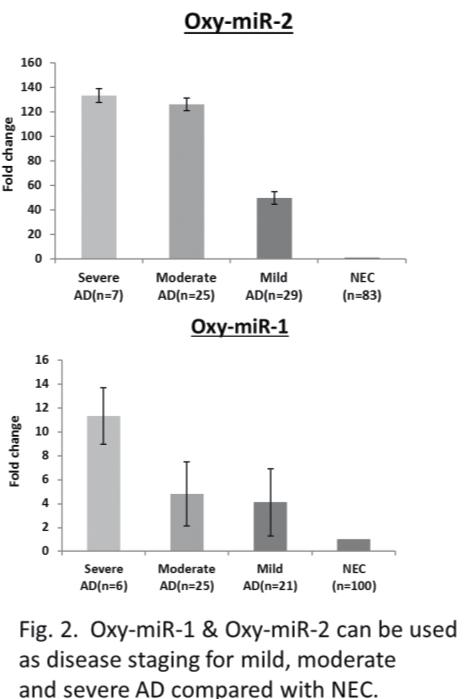

Some individuals start to suffer from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as they grow older, which is often marked by short-term memory loss. This of course is a major concern to the individual affected, but by and large they are still able to live independently; by contrast, cases of Alzheimer’s disease have a far more significant impact. “Alzheimer’s disease cases are characterized by the person starting to lose the ability to perform daily activities, like how to eat and how to bathe,” says Dr Wang. It is thought that people who score less than 24 on the MMSE score are suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, which is then the basis for a more detailed diagnosis. “Then you sub-divide Alzheimer’s patients into three categories; mild is 21-24 on MMSE score, moderate is 10-20, and severe is between 4-9,” outlines Dr Wang. “Not everybody suffering from MCI will convert to bona fide Alzheimer’s disease, but some will. About 15 per cent, annually, convert from MCI to Alzheimer’s disease.”

Oxy-miRs

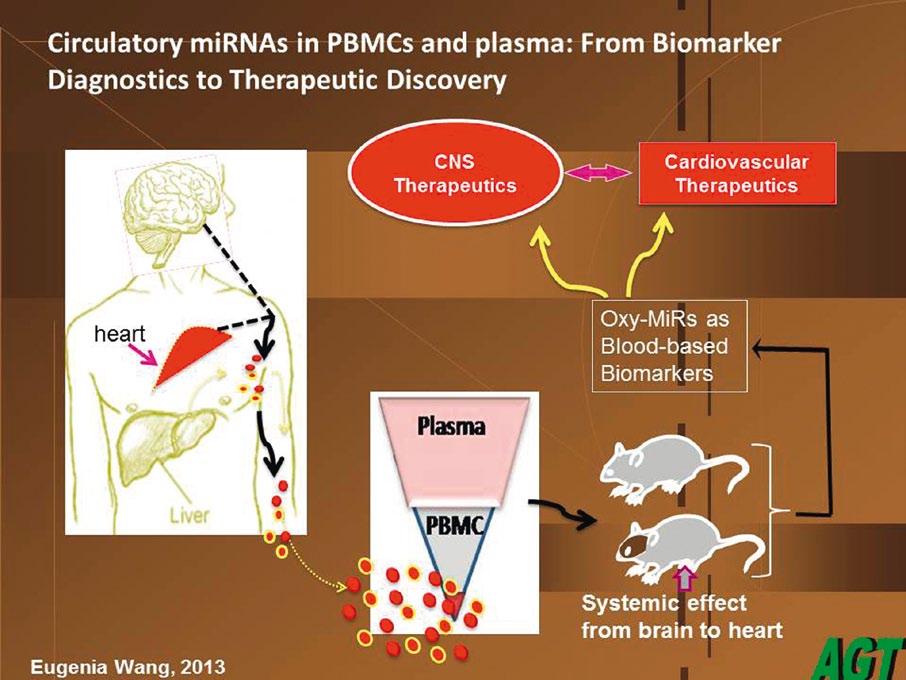

The first objective in Dr Wang’s research was to identify blood differences between Alzheimer’s disease cases and normal controls. Dr Wang and her colleagues have found that this is mainly expressed through Oxy-miRs, a particular species of microRNA whose functions are associated with oxidative defence. “So far we have identified six types of Oxy-miR (reference at the end of the article) that can differentiate between Alzheimer’s patients and normal elderly controls. We are doing in-depth, large population studies on three of them,” she outlines. Oxy-miRs are a subgroup of microRNAs which functionally suppress the expression of a lot of target molecules, acting almost as a dimmer switch which controls levels of gene expression. “We identified the OxymiR species, made a full gene sequence and put it in a vector, then we put it in a mouse. We’ve made a few transgenic mutant strains, and they now express these same microRNAs, but they overproduce them. So these mice are accelerated in their ageing effects, and are being tested now for the amyloid marker associated with Alzheimer’s. Early data shows us these mice have an accelerated senescent phenotype,” explains Dr Wang. These Oxy-miRs are not solely associated with ageing, however, but also play a key role in the body’s defence

against oxidative stress, which occurs when superoxides build up in response to stress, be it emotional, or any other type such as that caused by environmental pollutants. Dr Wang says the body has a mechanism to overcome this. “It has a lot of defence enzymes to get rid of the superoxides. The back-line defence of the body is very smart; it can say, ‘okay, this cell has really got too damaged, I want to get rid of it.’ So it institutes a cell death programme called apoptosis,” she explains. When we want to get rid of damaged cells we institute this mechanism by Oxy-miRs, but this same mechanism can cause problems in later life, a classic case of what scientists call antagonistic pleiotropism. “You gain something in early life at the expense of losing control of it in later life. So in our life we need Oxy-miRs, but an accumulation of them late in life can become too much for us to deal with. Then they may be inappropriately expressed in cells where you do not want them,” says Dr Wang.

The human brain is very versatile and very plastic, so it can accommodate the loss of a certain number of synapses and cells, as typically occurs during the ageing process. However, beyond a certain threshold, losing synapses will begin to cause significant problems. “It’s about how much you can tolerate the loss. So normal elderly controls may lose only 40 per cent. With Alzheimer’s maybe you lose 60 per cent, and you’re into a disease situation. That is the molecular marker we’re looking for, the threshold changes between Alzheimer’s disease and normal controls,” says Dr Wang. Researchers are looking at plasma, the cell-free component of blood, to monitor levels of microRNAs, including Oxy-miRs. “Every human being has a defined volume of blood - you can tolerate a certain amount of change either side. Our blood cells have a fixed lifespan, while our plasma is really a reflection of what we are; it’s generated by discharges from cell-to-cell communication, or from the dead cells from all the tissues. Blood cells effectively bathe in plasma, which is where we can detect and monitor OxymiR levels,” explains Dr Wang.

Blood test

This will provide clinicians with important insights into the progression and development of the disease, as well as enabling them to monitor the effectiveness of treatment. There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, but issues like stress levels and diet are known to be risk factors in the development of the disease, so a blood test could form the basis of more tailored interventions. “I think we should look to develop what I call a combinatory approach which combines stress reduction, mental and physical exercise and dietary changes. Improvements in diagnosis will allow clinicians to focus therapeutic intervention,” says Dr Wang. Eventually

certification, with a community population. That is a step towards commercialisation, and marketing our tests,” says Dr Wang.

The proof of principle is already established and patented; now Dr Wang aims to take her test to the market. Caring for Alzheimer’s patients currently costs the US more than $100 billion a year, but a blood test could help health authorities plan care more effectively, potentially bringing down costs. “We can look at a patient’s Oxy-miR levels and their MMSE score and see that’s defining them as moderate, meaning someone who probably can’t eat well and has to be reminded to fulfil some of their daily functions. We can then tailor healthcare delivery to their particular condition,” explains Dr Wang. This is very important for the care giver - often a relative who already carries a

heavy burden - as they typically want to help them maintain a degree of independence. “For somebody with a mild case, with an MMSE score on the borderline, you may want to provide them with a meal that they could handle themselves, and they would have more independence,” says Dr Wang.

This test could also be highly important in the earlier stages of the disease, leading to earlier diagnosis and allowing people to take preventative action, such as modifying their diet or taking more exercise. The first population studies, based upon which the test has been patented, were done on a clinical population in Montreal by two neurologists with whom Dr Wang collaborates; now she plans to work with people who have been identified as being at risk of developing Alzheimer’s, to gain further insights into the early stages of the disease. “We have deliberately selected people who are in their ‘50s - we are working with five groups of people in their ‘50s, and have started to collect blood samples. These include people with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease in first degree relatives, and other people who are lacking such a family history as the control,” she outlines.

So far we have identified six types of Oxy-miR that can differentiate between Alzheimer’s patients and normal elderly controls. We are

Dr Wang would like to use this test as a general Alzheimer’s screening test for everybody aged 65 or over, a move towards a more personalised approach. “Then each person could say; ‘oh, my Oxy-miR is not at a good level – maybe I should modify my diet or take more exercise. That is what I would call a more broad-based approach,” she says.

It would also be considerably less expensive than the current methods of diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. MRI scans are prohibitively expensive for many people and not all hospitals have a neurological assessment facility, whereas the blood test Dr Wang is developing would be much less costly. “Our goal is for such a blood test to be used in a ‘point of care’ facility such as a doctor’s office or a clinic, where you can go to give a blood sample. They can send a plasma sample to our company, Advanced Genomic Technology, and we can evaluate the OxymiR status,” she says. This could be used as a first stage screening test, as blood samples are readily accessible, then a recommendation could be made on whether the next level of testing is required. “We’re ready to take the next step, called CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment) laboratory

Full Project Title

GENERATING BLOOD-BASED DIAGNOSIS FOR ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Project Objectives

AGT’s mission is to develop and market a non-invasive, blood-based test for diagnosis and prognosis of: (1.) Alzheimer’s disease (AD) victims and at-risk groups, including individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and elderly > 65 years of age; and (2.) metastatic ovarian cancer (ova-ca), providing RNA-based early detection for restricted metastatic carcinoma.

Project Funding

National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, USA; Kentucky Science Technology Corporation

Contact Details

Project Coordinator, Dr Eugenia Wang 5100 US Highway 42 Suite 433 Louisville, KY 40241 USA T: +1 502 228 5438 E: ewangagt@gmail.com W: www.advancedgenomictechnology.com

Schipper, H. M., Maes, O. C., Chertkow, H. M., and Wang, E. MicroRNA expression in Alzheimer blood mononuclear cells. Gene Regulation and Systems Biology 1: 263 - 274 (2007). PMID: 19936094.

Dr Eugenia Wang

Project Coordinator

Dr Eugenia Wang is Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the School of Medicine, University of Louisville (UofL), Louisville, Kentucky. She also holds the Gheens Endowed Chair in Aging and is the Director of the Gheens Center on Aging at UofL. Dr. Wang investigates the molecular mechanisms controlling the process of aging, at both cellular and organismic levels.