SMALL SCALE FISHING DOES NOT ATTRACT GENERATION Z

12 25 39

SEAFOOD

EXPO GLOBAL breaks records— again!

EU PROJECT

AlgaeProBanos will boost the continent’s algae industry

POLISH RESEARCHERS’ new fish trap keeps fish alive, and defies seals

JUNE 2024/3 www.eurofish.dk Poland PUBLISHED BY

JOINING FORCES for AQUACULTURE

Visit us at AQUA24 in Copenhagen on August 26-30 at stand 33-35 to see how six EU projects seek to improve European aquaculture.

Margar sem WF_427163_SEG19_InfoFish_QF.indd 1 12/3/19 2:39 PM

EUMOFA European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products Smart Aqua4 FuturE

Many small scale fisheries in Poland suffer from declining catches

Wolin, the main town on an eponymous island separating the Baltic Sea from the Szczecin Lagoon, is host to the Wolin Fishermen’s Association. Members have experienced a 45 percent decline in landings over the four years to 2023, something they attribute to a combination of o cial restrictions with regard to shing, increasing numbers of predators, dredging and land reclamation works, and the impacts of climate change on the marine environment. However, in other parts of the lagoon shers report that catches though uctuating from year to year are broadly similar to what they have been in the past (page 47)

Recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS) generate waste rich in phosphorus and nitrate. is waste is treated to denitrify it and remove the phosphorus so that the concentrated sludge can be used as fertiliser for crops. e active sludge technology used in sewage treatment plants o ers a model that can be used to treat the sludge from recirculation aquaculture systems. Researchers from the University of Copenhagen and AquaPartners, a private company, concluded from a pilot study using a saltwater recirculation system that active sludge technology had the potential to enhance the sustainability of marine aquaculture (page 26)

Euro sh is part of a consortium (SAFE) that seeks to reduce the environmental impact of freshwater aquaculture by using the e uents in the production of edible biomass for humans (mushrooms, salads) and sh (microalgae, redworms, mealworms). e objective is to increase the circularity of the system whereby waste from sh production is used to grow a feed that can be given to the sh in a virtuous cycle (page 30)

Aquaculture in Georgia includes the farming of trout, carp, sturgeon, and European cat sh in freshwater bodies and Atlantic salmon in the Black Sea. e sector is likely to be given a boost once the recently drafted national aquaculture development strategy is adopted. e strategy outlines four objectives related to government, production, markets and social development which are to be achieved with support from the GFCM (page 52)

Macroalgae have a lot going for them. ey are often edible o ering a number of valuable micronutrients; they do not use valuable resources such as land and fresh water as they grow in the sea; and they are a useful carbon sink. While macroalgae is consumed at scale in east Asia, in the EU it is only just being discovered, something that the European Commission is working to change, says Dr Manfred Klinkhardt (page 55)

Dr Susan Steele, the executive director of the European Fisheries Control Agency, is responsible for the day-to-day operations that seek to ensure that sheries activities comply with the provisions of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. is is only part of her brief, however. She also oversees the agency’s e orts to deliver capacity building, training, and competences to the national sheries inspectors and supervises the cooperation with other European agencies working in related areas (page 62)

In this issue

EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 3

EFCA

6 International News

Events

12 Seafood Expo Global, Seafood Processing Global, Barcelona Unparalleled enthusiasm for seafood

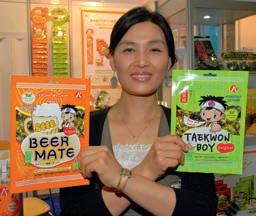

13 Poland pavilion highlights sophistication of nation’s processors

14 PP Orahovica has expanded into farming African catfish

14 The beauty of Salmco’s machines lies in their simplicity

15 Starfish Seafood shows off their salmon smoking skills

16 Bivalve farmers beset by challenges

16 Mussel farming company Fratelli D’Andria exports spat to Spain and France

17 Pelagos Net Farma produces tuna and small pelagics

17 Akvapona farms and processes African catfish

18 Eva canned sardines are based on Adriatic fish

18 Bajcshal guarantees stability of catfish deliveries

20 Smyrna Goods sells wild products from the Aegean Sea

21 Politek produces and processes Turkish Salmon from the Black Sea

22 Creating awareness of the ocean among pupils across Europe

23 GLOBALG.A.P. panel discussion at SEG Collaboration for traceability and transparency

25 AlgaeProBanos project meeting, 3-4 April 2024, Copenhagen Giving the EU algae sector a boost

Projects

26 Study shows active sludge technology’s potential to treat waste from saltwater land-based fish farms Making marine RAS more sustainable

30 The SmartAqua4FuturE (SAFE) EU research project Seeking a revolution in freshwater aquaculture

Poland

34 Adapting to and mitigating climate change impacts calls for new approaches Challenges abound but so do opportunities

37 WPUT’s Food Science and Fisheries Faculty Cross disciplinary cooperation is a strength

DK SE FI LT DE UK IR NL BE CH AU SL BY RU RO HU IT ES IS PT RU SI MT HR AL BG BA RS EL MA DZ TN LY CZ NO LV ME MK PL EE FR LU MD UA 4 Table of News

40 Polish Angling Association hatchery in Goleniów Restocking waters in West Pomerania

43 The logistics of buying, processing, and distributing fresh fish are challenging Whitefish products for the EU market

45 Perch from the Szczecin lagoon now dominates processor’s assortment Adapting to the lack of Baltic cod

47 Making the most of EU funding opportunities Fishers struggle to adapt to changes

49 A group of fishers has concerns about the future of their industry Diversification is the way forward

Georgia

52 The aquaculture sector in Georgia Potential exists despite the challenges

Aquaculture

55 The rising tide of macroalgae cultivation in the EU Macroalgae aquaculture needs to be expanded

Ukraine

59 Ukraine’s seafood business: Impacts of Russia’s war against Ukraine Living on a powder keg

Guest Pages: Dr Susan Steele

EG AZ KZ UZ IR IQ IL JO SA LB SY CY TM TR AM GE (CC BY-SA 3.0) Map based onhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Location_European_nation_states.svgby Hayden120 and NuclearVacuum EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 5 Contents

62 The European Fisheries Control Agency A key partner in the fight for fisheries sustainability Service 61 FISH Infonetwork News 65 Diary Dates 66 Imprint, List of Advertisers Worldwide Fish News Australiapage 8 Belgiumpage 7 Denmarkpage 9 Germanypage 8 Icelandpage 9 Lithuaniapage 6 Norwaypages 6, 7

Norway: Salmon volume dropped, pulling down total seafood export value in Q1 2024

In recent times Norway’s salmon export success has been due to strong prices, not volume, which has been relatively steady. But in this year’s 1st quarter, volume dropped significantly, causing a value drop in the country’s overall seafood exports. The drop has been attributed partly to a production decline caused by a fall in sea temperatures compared to last year. Seafood exports dropped by 3 in value in the first quarter compared to the same period in 2023, disrupting a 3-year value rise. Norway’s currency value visà-vis the euro and dollar has fallen for some time, making its product

prices cheaper in export markets and has helped fuel revenue gains. But such gains have previously depended on a volume of exports that at least stays constant.

The recent volume drop in Q1—to 246,560 tonnes of salmon—more than offset any exchange rate advantage, and Norway’s total fish export revenue fell to NOK 40.2 billion (EUR 11.7 billion). Norway’s largest markets are in the EU, including Sweden and Poland, which process salmon for reexport throughout the EU. Norwegian salmon prices are influenced by global production (which

In 2023, Norwegian exports of salmon reached 1.2 million tonnes valued at EUR 10 billion, or more than 70% of the country’s total seafood exports.

Norwegians play a large part in) and demand. Demand for salmon, in filleted or steak form, fresh or frozen, has been strong for many years, and that has helped Norway, whose salmon (and trout) farmers also have operations in

other countries, such as Chile, the world’s second largest farmed salmon source. Norway’s exports of other species, such as cod, showed mixed results. The largest cause of revenue decline was farmed salmon to the EU.

Lithuania: Environment agency improves rules for reducing cormorant problems

After humans, cormorants are perhaps the largest consumers of fish from Baltic aquaculture sites. These shore birds, of medium size but maximum appetite, nest in colonies along the coast where their favorite food—fish, wild or farmed—is to be found. They are immensely costly to aquaculture farms along the Baltic coast. In Lithuania, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has long sought a balance between populations of cormorants and “populations” of fish farms. For many years the EPA, with EU money, helped farmers with using “nonlethal” means to control cormorants, such as coating their eggs with oil to prevent them from hatching, and financially compensating farmers for cormorant-caused losses. In recent years the money spent on this support has risen to a third of the agency’s entire budget for aquaculture and nature management efforts.

However, the problem has continued. Recognizing cormorants are not an endangered species, the EPA recently announced a new system of individual quotas (farmspecific) for cormorants that are “caught or destroyed” by farmers. The quotas are determined by the EPA using data that farms shall report on the number of problematic birds and the financial losses they cause. Farms can then take the necessary action to reduce the problem, during a period each year set by the agency in accordance with other environmental factors that fall under its managerial purview. “We have agreed that it would make sense to take the next step and go towards setting individual quotas, by determining the number of birds that can be taken for each farm,” said an official. The implementation of the new system is being done gradually; the goal is to have the system fully implemented by 2025, and this year 15 farms will be fully in the system, with only a few more to go.

Cormorant populations are on the rise in the EU, posing a threat to regional fisheries and the viability of smaller enterprises.

Cormorant populations are on the rise in the EU, posing a threat to regional fisheries and the viability of smaller enterprises.

[ INTERNATIONAL NEWS ] 6

Seafood consumption promoting project kicks off in Brussels

Despite its potential advantages in terms of climate impact, sustainability, and nutrition, seafood is frequently disregarded or lumped together with meat. The potential benefits of seafood are often overlooked, particularly in the transition towards a sustainable, equitable and balanced protein system. Seafood consumption in Europe is low compared to meat consumption, and locally produced seafood often cannot compete with imported products because consumers do not know about or value local seafood. To enable healthy and sustainable choices, consumers need information about sustainability and nutrient values as well as provenance and potential health risks and benefits.

VeriFish, a project funded under Horizon Europe will provide a framework of verifiable sustainability indicators based on existing EU and global databases. VeriFish will work on the creation of a prototype web

application, a series of media products and recommendations for communicating sustainability indicators to various stakeholders including guidelines for retail and the hospitality sectors. The goal is to provide an accessible and dynamic framework for the improvement of communication and understanding of sustainable seafood production and consumption.

The indicators framework must not only be communicated to seafood producers and retailers, but also to policymakers, citizens, and children. Therefore, a storytelling series, recipe books for kids, puzzles, and posters are among the planned product outputs. Finally, the project will develop and publish European Good Practice recommendations, co-designed with seafood sector stakeholders, on how to efficiently use the indicator framework to communicate with citizens. The VeriFish website will be launched in June at verifish.info from where one

One of the world’s largest producers of farmed fish has a new fisheries minister following a reorganization of government. Norway’s LaborCenter coalition government has been in power since 2021 and since then has averaged one fisheries minister per year, as it frequently rearranges ministries across the board or replaces people who leave government for one reason or another. The latest appointee will have to learn on the job as she comes from a non-fisheries background, but she is committed to her new role. Marianne Sivertsen Næss takes over the job from Cecilie Myrseth, who has been appointedindustry minister. The community’s marine resources must benefit

the community. The government must pursue an active maritime policy, which ensures people safe and good jobs that we will live on in the future, Ms Næss said. A teacher and school principal before entering politics, she was elected mayor of Hammerfest municipality from 2019 to 2021. She then entered the Storting (Parliament) representing Finnmark and has since chaired the energy and environment committee until her new appointment. The minister of fisheries is responsible for implementing the government’s policy relating to fisheries, aquaculture, and seafood, as well as other policy areas relating to coastal development and sea transport.

Members of the VeriFish consortium at the kick-off meeting. From left to right, back row: Alessandro Petrocelli (COMMpla), Marco Frederiksen (Eurofish), Peter Olsen (NOFIMA), Karl Presser (Premotec PLN), Ixai Salvo (Eurofish) Paul Finglas (EUROFIR), Yannis Tzitzikas (FORTH), Themis Altintzoglou (NOFIMA), Toni Bartulin (Eurofish), Yannis Marketakis (FORTH).

Front row: Sabrina Duri (Trust-IT), Sian Astley (EUROFIR), Sara Pittonet (Trust-IT), Marte Olsen (NOFIMA), Christine Absil (Clupea), Silje Steinsbo (NOFIMA), Michelle Boonstra (Clupea), Cristina González (EUROFIR)

can also reach the project’s social media accounts on X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube.

Norway: Cabinet reshuffle results in a new fisheries minister

Marianne Sivertsen Næss is Norway's new fisheries minister with responsibility for fisheries, aquaculture, and seafood.

Marianne Sivertsen Næss is Norway's new fisheries minister with responsibility for fisheries, aquaculture, and seafood.

[ INTERNATIONAL NEWS ] EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 7

Germany: Closed season set in North Sea fishery to protect eels

The German government has announced a closed season for eels in its North Sea waters, from 1 September 2024 to 28 February 2025. This coincides closely with an EU-wide seasonal closure for eel fishing in the Baltic Sea from 15 September 2024 to 15 March 2025. Both restrictions exclude the late summer period of eel migration, a key time for harvesting activity. There is only one stock, or population, of eel in all of Europe. Despite being perilously close to extinction for many years, as judged by

the world’s main organizations that monitor the state of natural resources, European eel continues to be legally fished in the EU, albeit with some restrictions that have proven to be ineffective in allowing eel resource recovery, according to ICES, whose scientific recommendations are supposed to form the basis of EU fishery regulations.

Eels are notoriously difficult to raise in aquaculture operations, so the wild fishery remains the principal source of eels. Despite the

vanishing numbers of wild eels, fishing is allowed by governments to continue because the eel fishery remains economically important in many rural regions. It is primarily a small-scale sector, supporting many in harvesting, processing, and marketing to a large base of consumers throughout Europe. There is no legal recreational fishing for eels in the EU. “Given the dramatically low population, it is high time to act,” said Claudia Müller, Parliamentary State Secretary to the Federal Minister of Food and Agriculture. “The closed

season helps the eels that are ready to spawn to make the long migration to their spawning area in the Atlantic, the Sargasso Sea east of Florida. The protection of the eel is also important because of its socioeconomic importance: eel fishing secures incomes in many places in Germany. Giving eel stocks a perspective also means securing the livelihoods of people on the coasts and in rural areas in the long term.” Whether Germany’s action will materially contribute to eel protection depends on other member states copying and enforcing it.

Australia: First in-person Seagriculture Asia-Pacific Conference to be held in March 2025

The Belgium-based organizers of the series of Seagriculture Conferences have announced plans for their very first in-person conference designed for the Asia-Pacific region, to be held 18-20 March 2025 in Adelaide, South Australia. The inaugural Asia-Pacific Conference was held in 2023 but it was on-line only. Seagriculture Conferences, which began in Europe in 2012, focus on seaweed production, innovation and marketing. Seagriculture Asia-Pacific 2025 is supported by ASSA (the Australian Sustainable Seaweed Alliance), whose mission is to promote environmentally responsible commercial farming of seaweed to provide food, feed and bioproducts. ASSA’s partners include the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC), the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), the Department of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia (PIRSA) and the Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF).

The event is cosponsored by the government of South Australia and indirectly by the federal government, which has provided A$8 million to the Developing Australia’s Seaweed Farming Program to support investment in the Australian seaweed industry.

There are 1,500 species of seaweed in South Australia waters, a number exceeded only by Japan. The state government has identified the seaweed industry as a growth sector to be promoted not only for employment opportunities but for environmentally sustainable production of wide array of consumer and industrial goods, from food (e.g., ice cream) and skin care (e.g., shampoo) to ingredients in livestock feed and dental molds, among countless other uses. Thousands of attendees are expected from all over the Asia-Pacific region as well as from far away. They will learn about the latest in farming technology, processes, and new products from a sustainable

Adelaide in South Australia will host the Seagriculture conference on seaweed production and innovation 18-20 march 2025.

marine resource whose future seems to be boundless. Plus, on location, attendees will be able to join a site visit to the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), a research facility

dedicated to the sustainable use of natural resources.

Further updates and registration information on the conference will be available on the website: www. seagriculture-asiapacific.com.

[ INTERNATIONAL NEWS ] 8

Italy: Vast piles of waste in fishing nets lead to interest in recycling

From plastic bags to household appliances, thousands of tonnes of waste are brought up from the sea in fishermen’s nets every year. After throwing much of it back and repairing the nets, fishermen are frustrated by this costly environmental problem. In Italy, an idea is emerging to bring the trash to port and recycle it. Most trash can be decomposed into its raw material—plastics,

metals, etc.—and can enter the huge recycling industry for land-based recyclable waste. In a ten year period, fishermen bring up enough trash to cover the circumference of the Earth 15 times, says Paolo Tiozzo, vicepresident of ConfcooperativeFedagripesca, speaking on this year’s Earth Day. It is a growing problem, but fishermen also pay the price for inaction— polluted waters.

Italy’s fishermen probably don’t relish the thought of hauling old tyres from the depths of the Mediterranean to port for recycling, but they might if they can be compensated for it. Plus, they benefit from knowing they are helping sea turtles, birds, and other marine life that make up the natural environment that fishermen are very much a part of. The recycling industry in Italy is worth 3 billion euros a year. It is well developed

Iceland: Presentation area at Icefish 2024 will be a first

Visitors to this year’s Icelandic Fisheries, Seafood & Aqua Exhibition in September will have the opportunity to experience a brand new feature. The IceFish 2024 presentation area. Sponsored by Icelandic consulting company Verkis, the presentation area will give exhibiting companies the opportunity to showcase their latest product, innovation, or initiative to a live audience in a specially built theatre within the exhibition. Presentations will run

on all three exhibition days. Icefish 2024 already boasts a ministerial opening, the Icefish Awards ceremony, and matchmaking meetings. The presentation theatre will provide visitors with the added benefit of being informed through short and sharp presentations on exciting launches during Icefish. A platform for companies to demonstrate their activities offers a more immersive and interactive experience where attendees learn about new technologies whilst exhibitors

and can utilize added materials from the sea. Such waste is “invisible” in that we rarely see it except when it is washed up on a beach. But the marine environment sees it for hundreds of years. A plastic bottle will lie on the sea floor for half a millennium, and even cigarette butts can stay there for half a decade. Any trash, large or small, hauled up and properly disposed of benefits the environment Italy’s fishermen rely on.

gain insights into customer interests. Presentations are expected to attract an audience that will be specifically interested in the topic being presented providing an opportunity to network and build relationships with potential

customers, partners or investors. Details can be found in the new events and demo listings, another new addition to celebrate 40 year’s of Icefish. For more information on bookings, please contact info@ icefish.is or call: +44 1329 825335.

Denmark: Six EU projects to improve European aquaculture join forces at AQUA24

Aquaculture is the world’s most diverse farming practice in terms of species, farming methods, intensity level, and is one of the most sustainable ways of providing animal protein to some of the 8.5bn people expected to populate Earth by 2030. While aquaculture on a global scale is booming, its growth in the EU is stagnant— something the European Commission would like to change. Six EU projects, AlgaePro Banos, AWARE, Baltic Muppets, EUMOFA, FishEUTrust,

and SAFE, dealing with various aspects of aquaculture, will be present at the shared Eurofish organised stand 33-35 at AQUA24 in Copenhagen, Denmark on 26-30 August. The AQUA events are held every six years and comprise a scientific conference, trade exhibition, industry forums, workshops, and student events highlighting the latest aquaculture research and innovation. Visit us to learn how we seek to accelerate growth in EU aquaculture.

JOINING FORCES for AQUACULTURE

[ INTERNATIONAL NEWS ] EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 9

The six project partners at the shared AQUA24 stand are:

AlgaeProBANOS is a fouryear Innovation Action bringing together 26 partners and affiliated entities with a mission to demonstrate viability and market accessibility for sustainable and innovative algae-based products and solutions in the Baltic and North Seas. Our vision is a thriving algae industry within Europe, supporting a broad range of innovative, sustainable, bio-based products, whilst generating new regional sustainable industries and economic growth. AlgaeProBANOS will directly contribute to the Blue Mission BANOS lighthouse initiative, which engages and supports stakeholders across the Baltic and North Sea to reach a carbon-neutral and circular blue economy.

AWARE, or Aquaculture Water Reclamation, pioneers a novel approach to freshwater aquaculture to meet the rising demand for low-carbon-footprint protein sources. By utilizing reclaimed water from rigorous treatment processes, the project integrates fish and vegetable farming in an aquaponic system, a groundbreaking practice in Europe due to regulatory challenges. Collaborating with local wastewater treatment plants, AWARE creates a sustainable loop between food production and wastewater treatment, optimizing low-value urban/peri-urban spaces and preserving natural water sources. This innovative approach promises lower environmental impact and greater resilience to climate change, such as water scarcity, while ensuring the end products’ safety, nutrition, and taste. Currently being tested in Castellana Grotte, Italy, AWARE aims to validate its pilot aquaponic farm within the local wastewater treatment plant and collaborate with authorities to establish the regulatory framework for reclaimed water aquaculture across Europe.

The Baltic MUPPETS project has an overall aim to demonstrate that it is possible to create a viable business based on Baltic blue mussels that is both profitable and beneficial to the Baltic Sea environment. The main objective is to develop new value chains for small mussels (1-3 cm) from the Baltic Sea for pet food and to develop innovative technologies for farming, harvesting, processing and side-stream use. The project will enable a new circular economy in the Baltic Sea Region as well as provide support to mussel farmers across Europe to develop, diversify, and scale their existing businesses.

EUMOFA

European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products

The European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EUMOFA) is an online tool for the EU fisheries and aquaculture sector, which aims at increasing market transparency and efficiency, and at analysing EU markets dynamics. The market intelligence provided by EUMOFA is useful for all stakeholders involved in the fisheries sector: producers, processors, importers, retailers, consumers, market analysts and policy makers. It represents one of the tools of the Market Policy in the framework of the Common Fisheries Policy.

Starting in June 2022, FishEUTrust is a 4-year Innovation Action funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe programme. The project is developing tools to maximize trust in seafood and aquaculture products by guaranteeing quality, safety, and traceability through sensors, metagenomics, genetic biomarkers, isotopic techniques, labelling, product passports, and blockchain. These tools will be integrated into a single digital FishEUTrust data platform. FishEUTrust is establishing five Co-creation Living Labs in the Mediterranean Basin, the North Sea and the Atlantic Sea to enable the validation and demonstration of these innovations for supply chain solutions.

The SmartAqua4FuturE (SAFE) project aims to reverse the declining trend of EU freshwater aquaculture by demonstrating a circular economy model that reduces emissions, minimizes impacts on biodiversity, supports local production of sustainable feed ingredients, improves profitability and creates new jobs. The objective is to reduce the environmental impact and improve the viability of freshwater aquaculture by valorizing solid and liquid waste streams from recirculating aquaculture systems and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems.

SAFE will enable the uptake of these solutions through local and regional scale demonstrations across the EU and will document the necessary management and governance conditions for successful transferability.

[ INTERNATIONAL NEWS ] 10

We look forward to welcoming you in September

The Icelandic Fisheries. Seafood & Aqua Exhibition hosts the latest developments from the industry showcasing new and innovative products and services, covering every aspect of the commercial fishing industry from catching and locating to processing and packaging, right through to marketing and distribution of the final product.

For more information about exhibiting, visiting or sponsoring, contact the events team

Visit: Icefish.is

Contact: +44 1329 825 335 or Email: info@icefish.is

Organised

Media Partner: 18 20

Iceland 2024 SEP

by:

TO Smárinn Kópavogur

#Icefish Book

stand now!

your

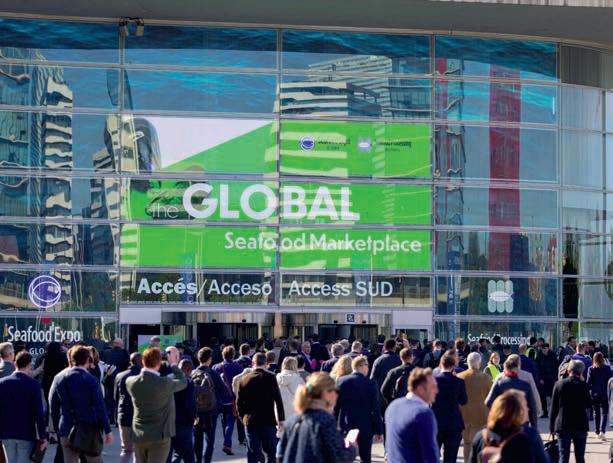

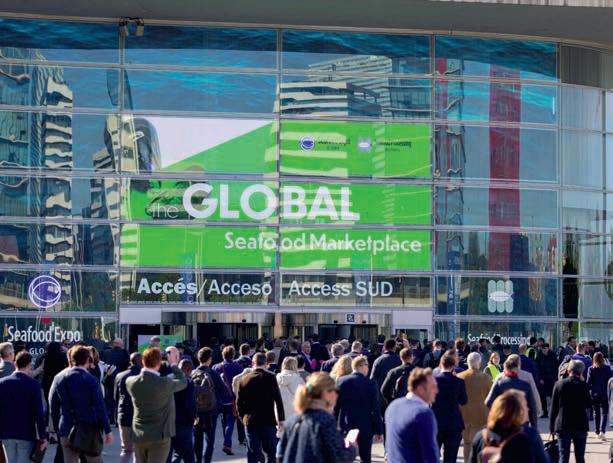

The global seafood industry thronged to this year’s edition of Seafood Expo Global and Seafood Processing Global in Barcelona like never before.

Seafood Expo Global, Seafood Processing Global, Barcelona

Unparalleled enthusiasm for seafood

The 30 th edition of Seafood Expo Global and the third one in Barcelona was the largest ever drawing almost 2,250 exhibitors from 87 countries. Diversified Communications, the organisers, estimate that over 35,000 professionals attended the event with stands or as visitors.

The world's most international seafood show was characterised by a huge variety of processed products from the simple to the sophisticated, made from a variety of species, and in every kind of packaging. The show includes Seafood Processing Global which features equipment and services for the processing industry as well as increasingly for the aquaculture sector. In addition, each of the three days of the event saw a series of seminars, discussions, and presentations on topics of relevance for the industry including sustainability, aquaculture,

labour issues, artificial intelligence and traceability. The Seafood Excellence Global Awards highlighted the best products in different categories giving exhibitors and visitors an overview of trends in product and packaging development. From Eurofish’s perspective almost all

its member countries were represented at the show. In the following pages the participation by some of them is reviewed and it is apparent how useful and productive they found the event. All of them were determined to return in 2025 when the event will be held 6-8 May.

Diversified Communications

12

Poland pavilion highlights sophistication of nation’s processors

As a country with one of the weightiest fish processing sectors in the EU, Poland has good reasons to be present at SEG. Here Polish processors can meet existing and potential suppliers and customers from all over the world under one roof. This year, the Polish Association of Fish Processors together with the Organization of Sturgeon Fish Producers organized a Polish national pavilion where 22 companies from the processing industry presented themselves: Abramczyk, Graal, Evra Fish, Barkas, Freezco, Antonius Caviar, Mik- Food, Mirko, Polski Karp , Offshore Fish Producers Organization,

Salmon Fish Processing, Rybhand, Seamor International Ltd, Seko, Stanpol, Tahami Fish, Thai Union Global, Dega, Contimax Trade, CPF Culinar, Sturgeon Fish Producers Organization. On 23 April, the first day of the show, the pavilion was officially inaugurated by Ms Ilona Kałdońska, Consul General of Poland in Barcelona, Ms Małgorzata Pawliszak, President, Polish Association of Fish Processors, and Mr Mirosław Purzycki, President, Organization of Sturgeon Fish Producers. As in previous years the pavilion featured a cook who prepared samples for the participants as well as for visitors to the pavilion.

Małgorzata Pawliszak, Polish Association of Fish Processors, Mirosław Purzycki, Organization of Sturgeon Fish Producers, and Ilona Kałdońska, Consul General of Poland in Barcelona officially open the Polish pavilion at SEG.

For Polish companies the show is a unique opportunity to promote themselves and their products. A Polish company was among the finalists for the Seafood Excellence Global awards competition suggesting that the seafood industry has moved from pure contract manufacturing to one that

develops sophisticated seafood products for domestic and international markets. Poland’s participation was enabled by support from the European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund for Fisheries program for 20212027 and from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

INTERNATIONAL FAIR OF FISH AND FOOD PRODUCTS GDAŃSK, POLAND

amberexpo.pl

PolFish

PolFish

polfishfair.pl

Monika Pain / Project manager monika.pain@amberexpo.pl

[ EVENTS ] EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 13

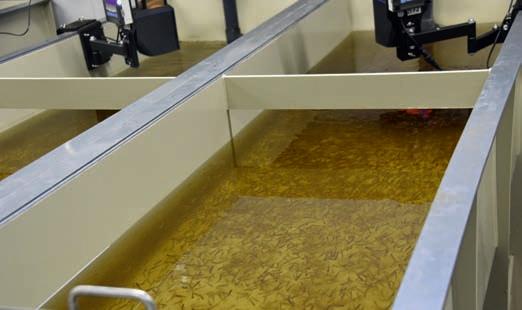

PP Orahovica has expanded into farming African catfish

In addition to farming carp and related species grown in polyculture in ponds, PP Orahovica, a Croatian company, is now also farming African catfish in recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS). The technology is very different from that used to farm carps, says Jakov Beslic Gadzo, the sales manager, as here we use very little water and can control virtually every parameter. Over the last two years the company has learned a lot about the production processes in a RAS and has expanded its production of African catfish, which are processed the same way as the carp. We make steaks, fillets, we pack in MAP, we freeze, and IQF— we make a lot of products from this fish, says Mr Gadzo. African catfish is very interesting for us because it is

robust to breed, the flesh has a very neutral taste, the texture is meaty which means it does not break up like the flesh of other species, and above all it has very few bones. This makes it very popular with children. But chefs like it too, they find it versatile because the taste does not dominate, and it can be successfully paired with sauces of many kinds. The company produces 150 to 200 tonnes of African catfish a year of a total production of 2,500 to 4,000 tonnes. How much the catfish production will expand in the future depends on the market. If there is demand we will expand further because the fish is relatively easy to grow and the technology allows us to control everything, Mr Gadzo states. However, the very fact that it can

The beauty of Salmco’s machines lies in their simplicity

A40-year-old manufacturer of slicing machines for the salmon industry, Salmco is known for the high quality of the equipment it makes. Its slicers can be found in more than 70 countries around the world, and today its most important markets in Europe are Turkey, Spain, France and the Baltic States. Most sales are through dealers in different parts of the world.

Werner Kuehl-Menk, the sales manager, sees several advantages to using dealers. They know the customer, can speak the language, and do the negotiation which allows us to concentrate on the engineering side of things to improve our machines. Despite this reliance on dealers, Salmco also successfully sell overseas and in many other countries, always remaining a reliable point of contact for their customers.

Katica

Katica

be easily produced encourages others also to invest in this production. So, it is a bit tricky, he feels. On the other hand, the company produces according to demand, production can be planned so that there are no surpluses, prices are maintained at around the same level, it is a predictable business, there is no stress.

Orahovica sells over three fourths of its total production outside its domestic market. Neighbouring countries in the Balkans as well as the rest of the EU are among the countries to which it exports. Visitors to the stand could sample batter fried products based on common carp, bighead carp, and African catfish.

The beauty of Salmco’s machines lies in their simplicity. We want our customers to be able to maintain their own machines without having to summon a technician, says Mr Kuehl-Menk. Making more complex products will move away from this philosophy. Besides our customers typically require a machine only for slicing, without any other extra features. Developments in artificial intelligence, internet of things, turnkey solutions etc. are no doubt interesting, but for Salmco they are more a distraction from the business of making simple, reliable, durable, and hygienically designed machinery. This is not to say that the machines cannot be modified. If customers need a standard machine adapted to their needs, Salmco will make the necessary changes. The machines have been evolving over the years. Since 2020

they all have programmable logic controllers, devices that can receive and process data and trigger an output. The knife changing system can now be done without a tool, while before the same operation required a screwdriver. Another refinement is the divided cover, the two parts of which can be removed also without the need

for tools and in just a few seconds lay bare the entire machine for maintenance or for cleaning. A further development that is now in the works is a new kind of belt that carries the product away after slicing. The new belt will allow even small pieces of sliced fish to be collected and sold thus contributing to greater efficiency.

Petkov, Marketing Manager and Jakov Beslic Gadzo, Sales Manager at PP Orahovica

Yana Pluzhnikova, Sales and Marketing, and Werner Kuehl-Menk, Sales Manager at Salmco, a manufacturer of fish slicing machinery.

[ EVENTS ] 14

Starfish Seafood shows off its salmon smoking skills

Seafood offers discerning retailers a range of high end

and

products based on salmon, as well as salmon sausages and salmon paté.

Among the companies present at the Latvian pavilion was firsttime exhibitor Starfish Seafood. The firm may have existed for only five years, but in that time it has managed to carve out a name for itself in the highly competitive market for secondary processed salmon products. These are based on raw material from Norway, the Faroe Islands, and occasionally Scotland, which the company converts into alluring hot- and cold-smoked products for clients in Latvia and other EU countries. Starfish, a Latvian Danish joint venture, started as a trading company, says Aija Serenda, the director, buying smoked products and selling them. But then we decided we could make products better than the ones we were trading, so we started our own processing facility. The production is sold under the company’s own brand, Starfish Seafood, or under a private label. We do a range of products, says Ms Serenda, and specialise in high end exclusive items for retail, where the raw materials, taste, look, and packaging all contribute to something very select. Moving from trader to processor has been a challenge, but the experience of trading has helped greatly in developing the products that Starfish really

wanted to sell. Cold-smoked salmon is produced using beechwood and the process creates a lightly salted product with a smoky smell and taste that does not drown out the natural taste of the fish. The hot smoke on the other hand results in a juicy fillet with a crunchy crust and a taste shaped by herbs such as pepper or garlic. Both types of smoked products can be produced in sizes ranging from 50 g (100 g for the hot smoke) to a whole fillet. The product can be packaged in modified atmosphere, vacuum, or skin depending on the customer’s preference. The company also produces a salmon paté and salmon sausages, the latter is made entirely from salmon with no other ingredients, while the paté spread on toast makes a delicious snack. Exhibiting at Seafood Expo Global has always been a dream for Ms Serenda which was finally fulfilled this year. And the experience has been overwhelmingly positive, she says, both in terms of the interest generated by her own products and the samples that were available to taste, but also because of the variety of products on display at the show which were a rich source of inspiration. As a result, she has every intention of returning to the show in 2025.

Starfish

hot-

cold-smoked

Starfish

hot-

cold-smoked

Kroma promotes a zero-waste policy Discover How We Can Unleash Your Potential Turn waste and dead fish to PROFIT with a SILAGEMASTER solution NO COOLING STORE OUTSIDE PERSIST FOR YEARS SILAGEMASTER Effective handling and storage of your By-product · Optimal solution for by-products · Minimal maintenance · Designed for your plant and needs · Get value out of your waste [ EVENTS ] EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 15

Bivalve farmers beset by challenges

The blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) is an invasive species in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic where it is destroying populations of bivalves. We lost EUR5m one summer in clam production to the blue crab, says Gabriele Albano, a consultant for the fisheries and aquaculture industry. They use their strong claws to crack open the clams and eat them. Mr Albano together with his brother proposed at a conference to extract the meat from the crab using high pressure processing (HPP), but the idea did not gain much traction. Part of the reason may be that Mr Albano is based in Taranto in the Apulia region in southern Italy where there is no tradition for eating crab. Blue crab meat may be more popular further north, he says where there is an existing tradition of eating green crab

(Carcinus aestuarii) in and around Venice. Clams (vongole) are virtually a national dish in Italy where they are typically eaten with pasta and Fedagripesca, an industry association, estimates that blue crabs have resulted in shellfish losses worth EUR100m across Italy, according to Politico, an online newspaper. The government has set aside EUR3m to combat the invasion. Fishers are trying to trap the crabs and destroy them, but that is not a lasting solution, Mr Albano feels. Better would be to treat is as a resource and exploit it. Blue crabs are however not the only challenge that shellfish farmers currently face. Mussel farmers in Taranto have seen the fee to the government for leasing their concessions increase by a factor of 10 completely upending the economics of their activity. Many farmers are

Mussel farming company Fratelli D’Andria exports spat to Spain and France

Gnot paying, says Mr Albano, preferring to wait and see what happens. But this triggers a series of warnings from the government, which are also not pleasant to receive. One solution might be for the farmers to consolidate their concessions. Since the fee is per concession a farmer with, say, five concessions would have to pay for each. By consolidating all five into one the farmer would only have to pay the fee once. The travails of Taranto’s shellfish farmers do not end here, however. Mr Albano recalls how a mussel farmer called him recently to ask if he had a solution for turtles eating his mussels. Apparently, loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) have been causing a lot of damage to his lines of mussels. There is nothing to be done about it, says Mr Albano, as the animal is under threat according to European legislation.

Gabriele Albano, a consultant for the fisheries and aquaculture industry in Italy, feels that by removing the meat using high pressure processing, blue crabs could go from being a menace to a resource.

abriele Albano, a consultant for the aquaculture and fisheries industry, is currently working on a project for a farmer of mussels and oysters in Taranto, Apulia. Franco D’Andria has been farming shellfish for over 40 years and one of the biggest changes he has noted is the increase in automation in the industry. Two decades ago everything was done manually—retrieving the lines, removing the mussels, separating them, cleaning, and packaging. Now, machines perform all these tasks. Automation has enabled Mr D’Andria to increase the number of workers he employed as the production became more efficient. Today some 15 workers are employed in the company.

Mr D’Andria has three concessions and has also been hit by the increase in the concession fee, but he has elected to stagger his payments over two years. But he is annoyed about the hike in the fee. We already pay taxes on our salaries, on our pensions, and a fee for the concessions, he says, increasing it like this is threatening our livelihoods. With Mr Albano’s help Mr D’Andria has sought support from European funds to invest in his business. The first time he bought a vessel to carry out the harvesting. The new boat was nearly 18 m long and equipped with the necessary machinery to harvest, clean, grade, and pack. More recently

he used the fund to equip buoys with RFID tags to prevent theft. While this is an occasional problem, more enduring is the increase in water temperature at the surface of the sea caused by global warming. Mr D’Andria has therefore moved his lines into deeper water where the temperature is lower. He is fortunate that the depth of the water where he has his concessions is 24 m, where usually in Taranto it is not more than 8 m. Moving the lines deeper in the water column does generate more work, but there is no real alternative as the mussels cannot tolerate the warmer water that prevails towards the surface. Like most farmers in the area Mr D’Andria is a primary producer. The mussels are harvested, cleaned, graded, and then packaged in nets for sale primarily in Italy. He also exports mussel spat to buyers in France and Spain, because the sea is very rich in spat. Any substrate introduced into the water will soon be covered by spat. To export it the

Franco D’Andria has been farming mussels for forty years in Taranto and has seen the positive impact of automation in his industry.

spat is collected on 6 m long ropes which are coiled on a pallet and transported by truck. They will easily survive for four days with some ice added into the coils.

[ EVENTS ] 16

Pelagos Net Farma produces tuna and small pelagics

The Croatian pavilion at SEG hosted companies working with many different species seabass, seabream, anchovies, tuna, and sardines. Jadran Tuna and Pelagos Net Farma are two of the four Croatian companies fattening bluefin tuna for the Japanese market. The two are related as the owners of Jadran Tuna are also part owners of Pelagos. Tuna are fattened by feeding them a diet of small pelagic fish and once they reach the right size they are sold to Japanese buyers. Processing vessels from Japan arrive at the time of harvest and take the harvested fish on board to process and freeze it down to minus 65 degrees. Pelagos’ vessels were targeting anchovies and sardines in the Adriatic to feed the tuna and so Dunja Gotovina, the sales director, thought it would be more profitable to use that fish to make products for human consumption. Anchovies and sardines are typical small pelagics

from the Adriatic and in Croatia these are usually salted or marinated. Pelagos began its activity with these species five years ago choosing the best fish from the catch while allowing the rest to be used as tuna feed. The feed is supplemented with frozen herring as the catches are insufficient to cover the company’s requirement for both processed products and tuna feed. The processing factory is located on the pier where the company’s ten vessels land the fish, so the raw material is very fresh when it arrives to be processed. The catch amounts to some 800 tonnes per year in total for both anchovies and sardines and about three fourths is processed for human consumption. We salt the anchovies, she says, and then fillet them by hand before placing the fillets in jars in olive oil or sunflower oil. Another product is marinated anchovies. The sardines, on the other hand, are individually quick frozen either whole

Akvapona farms and processes African catfish

Vladas

working with this fish for the last decade and has seen its popularity increase several-fold. One reason is availability. As a relatively unproblematic fish to

or headed and gutted. Sometimes in summer when the sardines are large, they are salted after being gutted. The salted sardines are then either packed in bulk in barrels as a semi-finished product or are packaged in retail-size glass jars or plastic containers with

breed catfish has proved attractive for entrepreneurs in many European countries particularly in the east. The meat-like texture of the flesh, lack of bones, mild taste, and the health benefits associated with fish make it a sought-after product especially in families with young children who are picky eaters. Mr Vickūnas has

olive or sunflower oil. When processed like this the raw material used is the fresh fish. The products are sold under the Pelagos brand on the Croatian market and at SEG Ms Gotovina hopes to promote them to a wider audience.

developed a range of products including headed fish, fillets with and without skin, portions, and no less than 14 varieties of frozen fish cakes. People at SEG are certainly more aware of catfish today compared with a few years ago when nobody had heard of it. But even so more work needs to be done to promote it, Mr Vickūnas

A Aqquuaaculture T Teecchhnology A small selection of our approved range of products for : Breeding - Holding - Feeding - Aerating - Monitoring - Catching - Transporting - Processing A AqquuaaTTeecch h Unterbrunnweg 3, A-6370 Kitzbühel/Austria, Tel: +43/664-1048297, www.aqua-tech.eu

From left, Dunja Gotovina, Sales and Marketing Director; Ivana Kuzman, Production Manager; Anamarija Bakmaz, Commercialist, all from Pelagos Net Farma.

Vladas Vickūnas and Svetlana Lvova, his wife, used SEG to explore the potential of African catfish on European and other markets.

Vickūnas, an African catfish farmer from Lithuania, is presenting his products at SEG for the first time. He has been

[ EVENTS ] EUROFISHMagazine 3/202417

feels. Discussions with traders at the show have revealed interest in catfish and its potential and a need for certain products like fillets and even whole fish, a product form he cannot sell in Lithuania. The catfish story is just beginning, according to Mr Vickūnas, who started with 50 tonnes and is now producing 1,000 tonnes. While catfish is a sturdy and

Eva canned sardines are based on Adriatic fish

Rovinj, a town in Istria, the westernmost county in Croatia, and one that borders Slovenia, is the site of the Podravka Group’s fish production facility. Fishers catch the raw material, mainly sardines, which are then brought directly to the factory to be processed and canned in Dingley cans. Canned sardines are just one of the products manufactured by the company; it also offers canned hake, mackerel, tuna, and tuna salads. However, the canned sardines is the product Tamara Blazekovic, the lead category manager in the fish business unit, is most proud of. This is because the raw materials come from the Adriatic and are of the highest quality, because of the natural conditions in the Adriatic Sea. According to Ms Blazekovic, the water has the ideal ratio of salinity and temperature which is responsible for the high quality of the fish. In contrast the mackerel used in the production is Atlantic fish. The Adriatic

also has mackerel, but the company was not sure that it would be able to obtain the raw material it needed on a regular basis and from the same source. The group does not have its own fishing vessels relying instead on agreements with independent fishers to supply it with the raw material. Sardines are the company’s biggest category and sales go primarily to Croatia and the neighbouring Balkan countries. Australia, the US, Germany, and Austria are among the other export destinations. Croatian salted anchovies are well known but the company has eschewed their production, because it is a lot of manual labour. Our processing lines are specialised for sardines and we also do not have the distribution facilities we would need if we were to export anchovies to Italy. The facility also produces for private label. At the moment, however, the private label activities have been interrupted because of the lack of sardines. We have to ensure there is

rapidly growing fish it is also sensitive, reacting to noises and smells, and therefore needs to be handled with a little care. Even a power outage when the farm switches automatically to a generator can upset the fish. Mr Vickūnas plans to invest in solar panels which will take care of most his needs making the farm more or less independent of the grid.

A range of canned products are sold under the Eva brand, of which the biggest is canned sardines, says Tamara Blazekovic, Podravka’s lead category manager in the fish business unit.

enough fish for our regular customers here in Croatia. Production last year was around 30m cans of which most were Dingley, but a small volume of club cans is also produced. Cans, says Ms Blazekovic, sometimes evoke negative sentiments among consumers because they associate it with

preserving chemicals (in Croatian the root of both words is the same). The company has launched a campaign emphasising how healthy its canned sardines in fact are, containing nothing other than fish, oil, and salt—and that they have an official shelf life of two years.

Bajcshal guarantees stability of catfish deliveries

AHungarian company, Bajcshal, representing the Hungarian Aquaculture and Fisheries Interprofessional Organisation, was one of the two exhibitors from that country at SEG. Bajcshal is primarily a processing company handling 1,800 tonnes of fish a year of which about a quarter comes from suppliers delivering trout and salmon, while the bulk is from V95. V95 is a producer of African catfish

among other species like carps and related pond-grown fish. Production of African catfish amounts to 1,000 tonnes per year, while the other species total some 250 tonnes. Bajcshal has collaborated with V95 since 2015 and both companies are led by Gábor Szilágyi. At Bajcshal the fish is subject to primary processing such as gutting, and heading, but also filleting and portioning. In addition, the raw material is processed into fish

soup, a Hungarian delicacy traditionally made from carp, which is sold both fresh and frozen. The catfish, on the other hand, is almost all sold as fresh fillets with a small fraction going into the production of smoked fish, smoked fillets, and soup. Mr Szilágyi also farms sturgeon from which he extracts the caviar. The fish and fish products are currently sold on the domestic market, but Mr Szilágyi is at SEG to look for

markets in other countries—in particular for his award-winning caviar. According to him, the biggest advantage with catfish is the reliability of supply. He can guarantee delivery all the year around. African catfish also grows rapidly, taking about 10 months to reach market size. The carps and other species raised in ponds take longer to reach market size and are seasonal—they can be harvested and sold only at a certain

[ EVENTS ] 18

time of the year. At V95 the catfish are raised in a flow-through system that derives water from a river. This is mixed with warm water from a borewell since catfish need water at above 20 degrees before they will feed.

Like other farmed fish producers in Europe, Mr Szilágyi is not happy about what he feels is the lack of a level playing field. Companies like his must jump through hoops to comply with legislation at the EU, national, and sometimes also provincial level, pushing up his costs, yet products from countries that may

not place the same demands on their producers can freely enter the EU. He thinks the lobby for European companies that depend on imported raw materials for their production has become too powerful. In addition, he surmises that there are vested interests in allowing the flow of freshwater fish into the EU because there are European investments in these third country producing and processing firms. These factors make it difficult to be a small-scale fish farmer in the EU and also contribute to the lack of growth in the EU aquaculture sector.

Smyrna Goods sells wild products from the Aegean Sea

Türkiye is well represented at SEG with a large national pavilion hosting companies producing and trading in seabass, seabream, meagre, and tuna among other species. Some of the companies represented also trade in products from capture fisheries. Smyrna Goods, for instance, has a portfolio that includes sea cucumber, squid, octopus, mussels and bottarga (salted and dried roe) from mullet. Ogün Demirel, the founder, who represented the company at SEG said he was looking for volume buyers (those interested in 200 tonnes and above) and was impressed with the quality of the contacts he had made. This was the first time the company was present at the show, but Mr Demirel is convinced he will come back next year. Sea cucumber was the product he started with 12 years ago, and since then he has been adding a new product each year to the portfolio. The company exports sea cucumber to South Korea and China and traders from these countries were among the buyers he met. Some of the other products such as the bottarga, cephalopods, sea urchin, and fish fillets are exported to Europe. The fish fillets are from farmed seabass and seabream and they together with the mussels are

the company’s only products from the aquaculture sector.

Based in Izmir on the Aegean Sea, the company has a fleet of some 100 10 m to 15 m vessels that are responsible for the catch of the wild products. Four fifths of the vessels supply the company exclusively, while the remainder are on contract. The fishing area is in the Aegean Sea and in the northern part of the Black Sea and the vessels supply the entire requirement of raw material. Part of the production is frozen, but we also have a truck a week going to Spain and Italy with fresh products, says Mr Demirel. The product range includes some highly value-added products such as a shrimp burger using the Turkish red shrimp. Available frozen, the burger has a shrimp content of 100%. How exactly the burger is made so that it doesn’t lose its shape when thawed and cooked is a trade secret. Many people have wondered about that, Mr Demirel smiles, but that is our intellectual property and will not be divulged. Because the product is 100% shrimp exporting it is relatively easy due to the lack of other ingredients whose safety may have had to be proved. As a fishing company, Mr Demirel says,

he is well aware of the issue of climate change and its impacts on the marine environment. But beyond the usual fluctuation in catches from

year to year they have not noticed any marked difference in the volumes of fish and seafood caught over the years.

Balazs Szilágyi (left), Dora Szilágyi, and Gábor Szilágyi represent Bajcshal, a Hungarian processing company and its production unit for farmed fish.

Ogün Demirel’s company Smyrna Goods catches, processes, and trades a variety of wild and farmed seafood with markets in Europe and Asia.

[ EVENTS ] 20

Politek produces and processes Turkish Salmon from the Black Sea

Türkiye is now well known for its production of Turkish Salmon, the trade name for trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that is raised to large sizes in the Black Sea. Production has increased steadily over the last years thanks in part to interest in the fish from many of the big fish farming companies in Türkiye as well as from several smaller operators. The fish and its roe are exported to Japan and Russia among other countries. At SEG the association of Turkish Salmon producers had a booth as did one of the producers Politek. Ömer Sener, foreign trade specialist at the company explained that Politek had a total production of 10,000 tonnes of the fish, 6,000 from the sea and about 4,000 from freshwater. The company has production facilities in

both marine and freshwater because the growing season in the Black Sea is only four months, while on land it is all year round. He considers the fish from both sources very similar—the freshwater fish are grown in large, deep lakes fed by nutritious water from the mountains. The fish from the lakes are introduced into sea cages in November and are harvested in June giving them 8-9 months of growth in the sea. We typically place 500-600 g fish in the sea and harvest them at 3 kg. It is also possible to put 1.5 kg fish in the sea and grow them to 5 kg. Temperature affects the appetite of the fish, if the water is cold the fish do not feed as well which reduces the growth rate.

Politek sells both fish from freshwater and from the sea and the fish

Politek prepares for the European market by investing in quality and processing capacity.

is sold fresh. The main markets are in Russia, Japan, Canada, Vietnam, and Thailand. The last couple of years has also seen a significant rise in interest from European buyers which is a very exciting development for the Turkish producers. We see it potentially as another Norwegian salmon story, says Mr Sener, though the two products

[ EVENTS ] EUROFISHMagazine 3/202421

are different and salmon from Norway is well entrenched on the European market. But demand from Europe is encouraging us to work on our quality. For this we have employed special quality managers, and we invest in our plants and

machinery. This year, for example, Politek established two plants with new machinery and a processing line that can handle 200 tonnes a day. Freezing capacity is also 200 tonnes a day and the company also has three cold stores with a

total —capacity of 12,000 tonnes. Currently the main product is frozen headed and gutted fish followed by fresh gutted fish. At SEG Mr Sener held meetings with potential Japanese clients who are interested in fresh shipments delivered

by air. The company also has a production of steaks, fillets, portions and smoked products. By-products from the processing operations such as heads, bellies, frames, and fins are also marketed to countries in south east Asia so that waste is minimised.

Creating awareness of the ocean among pupils across Europe

The European Marine Science Educators Association brings together people and institutions who work in blue education across Europe to create greater awareness about the oceans and the challenges they face. The institutional members could be universities, teaching institutes, aquaria, NGOs, or government departments, and the target for these information campaigns are citizens in general with a sharper focus on children and young adults in education. This could be in primary, secondary, vocational schools, maritime schools, or even universities. The association develops programmes on ocean literacy which can then be integrated into an existing course. The idea is to show what is possible and hope that the recipient organisation will be encouraged to do something similar that will make pupils, students, and staff more aware of the marine environment and the challenges it faces. For example, says Evy Copejans, managing director of the association, a module could include information about sustainability or fish species and could become part of a fisheries education programme. Or a degree in oceanography could include a module about the blue economy. These modules could then be shared with other institutions for them to adapt (or not) and incorporate in their programmes. The association is currently driving

a programme for primary and secondary schools that seeks to bring the ocean, ocean economy, ocean health, and environmental issues to these schools all over Europe and that will be adopted into the regular curriculum. Since each country and educational system takes a different approach the association tries to identify the right people in the right positions who can strengthen the message and magnify the

level of awareness. As an example, Ms Copejans points to the port city of Den Helder in the Netherlands from where young people would leave in search of education or work. The port could offer jobs, but not enough people knew they existed. So, the port authorities and the association designed a programme that started in primary school and continued into secondary school and informed the pupils about

professions needed by the port. Apart from helping the port and the young people, the programme allowed the association to approach the government and demonstrate why it was worth investing in and replicating in other contexts. A certain momentum was thus created from this project that could lead to similar efforts in other places, which is one of the objectives of the association.

Evy Copejans, managing director of the European Marine Science Educators Association, a body that seeks to promote awareness of the ocean and the challenges it faces to school children of all ages across Europe.

[ EVENTS ] 22

GLOBALG.A.P. panel discussion at SEG

Collaboration for traceability and transparency

Aquaculture experts emphasized cross-sector collaboration in the face of evolving aquaculture supply chain transparency requirements.

AGLOBALG.A.P.-sponsored panel discussion titled “Responsible Aquaculture Supply Chains” brought insights from a broad range of voices across the aquaculture sector at last month’s Seafood Expo Global (SEG). During this insightful conversation moderated by Marco Frederiksen, Director, Eurofish International Organisation, industry experts found common ground in the theme of collaboration to meet

aquaculture’s rapidly evolving demands for transparency and traceability.

Collaboration at all levels across aquaculture

Dawn Purchase, Aquaculture Program Manager at the Marine Conservation Society, stressed the vital importance of cooperation at the global level to develop and implement data-driven traceability in aquaculture to mitigate

today’s environmental concerns and achieve sustainable aquaculture systems.

“Collaboration in legislation development identifies and addresses pressing challenges of concern to all stakeholders,” explained Ms Purchase. “We must not forget that we are in a nature and climate crisis, which is why traceability supported by data-based management systems needs to be embraced not

only on a European level, but also globally. Legislation needs to be developed that identifies emerging issues, drives research, and gathers data to establish binding commitments.”

Audun Lem, Deputy Director of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Division and Secretary of the FAO Committee on Fisheries, brought an international and government-level perspective to the discussion.

VIMIDA. YOUR FISH – OUR PASSION. Timeless tradition and modern machinery Lesta 7, Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 555 05 777 E-mail: info@vimida.ee www.vimida.ee Please contact us for more information and to place an order

[ EVENTS ] EUROFISH Magazine 3 / 2024 23

Dr Lem highlighted the growing emphasis on traceability in the industry, and pointed out how aquaculture continues to lead the development of traceability systems within agriculture at large. In further support of the spirit of collaboration, he concluded that governments must welcome input from industry if they are to successfully meet the challenges facing today’s global markets.

Carlos Tavares Ferreira, Sustainability Manager at the Spainbased Stolt Sea Farm, described the real-world challenges of

data collection and data management at the farm level and highlighted the need for workable long-term solutions. He called for support from other supply-chain stakeholders so that, together, they could overcome the challenges facing the industry.

Certification as a tool to demonstrate responsible aquaculture

As a standard-setter for aquaculture and other agriculture sectors, GLOBALG.A.P. constantly seeks input from industry stakeholders

to provide solutions that promote responsible farming around the world. Remko Oosterveld, Aquaculture Key Account Manager, GLOBALG.A.P., represented the brand in the discussion. “Only with cross-stakeholder collaboration can we, as an organization, develop standards that meet the requirements of the whole industry,” he said. “To achieve increased transparency and traceability, with increasing requirements, cooperation with all stakeholders in the supply chain is vital. GLOBALG.A.P. ultimately exists to support the whole sector.”

According to Teresa Fernandez, Sustainability Senior Manager for Seafood and Crops at Hilton Foods Ltd., certification is a tool for suppliers to give tangible proof that they are operating responsibly. “Certification is the baseline for everything that we are doing, and we appreciate holistic approaches that benefit the whole supply chain,” she said. Seafood processors like Hilton Foods favour raw materials sourced from certified producers because certification to trusted standards helps to mitigate risks in the complex aquaculture supply chain.

Audun Lem, FAO; Dawn Purchase, Marine Conservation Society; Teresa Fernandez, Hilton Foods; Carlos Tavares Ferreira, Stolt Sea Farm; Remko Oosterveld, GLOBALG.A.P.; and Marco Frederiksen, Eurofish International Organisation, discuss transparency and traceability in the aquaculture supply chain.

[ EVENTS ] 24

AlgaeProBanos project meeting, 3-4 April 2024, Copenhagen

Giving the EU algae sector a boost

AlgaeProBanos is a Horizon Europe project that aims to demonstrate the viability of and market accessibility for sustainable and innovative algae-based products and solutions in the Baltic and North Sea areas.

AlgaeProBanos contributes to promoting a European algae industry by supporting the development of a broad range of innovative algae-based products thereby creating new sustainable regional industries and boosting economic growth.

On 3-4 April the AlgaeProBanos consortium assembled in Copenhagen at the headquarters of a project partner, Eurofish International Organisation, for the annual project meeting. More than 60 participants—representatives from various companies, partner organisations, and different countries—attended the meeting.

Partners generally satisfied with the progress made in the project

On the first day, progress made in the first period of the project was presented and discussed in detail. The latest deliverables, such as the interdisciplinary multi-level sustainability assessment framework for micro- and macroalgal value chains, and milestones like the “Train the trainers” online workshops were evaluated. Views on these topics were exchanged and developments in specific areas of algae production and processing were debated. Participants also received information and progress updates from sister projects of AlgaeProBanos,

Algae-based shrimp, caviar, and chips were among the innovative products that participants at the meeting got to sample courtesy the Danish company, Jens Møller Products ApS.

namely Locality, Seamark and EU4ALGAE.

The following day, besides familiarising themselves with broader areas of working with algae, attendees tested the digital tools that are under development within project tasks and provided feedback to help improve them. One such tool, Algae Economist, is a biorefinery tool to screen and optimize the economics of algae production, while another, AlgaeBrain, will assist researchers to rapidly find relevant answers to specific questions.

Danish producer shows the potential of algae

The meeting concluded with a field trip to the facilities of the company, Algiecel, just outside Copenhagen, where a pilot project is in progress that provides bio-solutions for decarbonisation, i.e. a modular microalgae photobioreactor. Participants gained firsthand knowledge of the challenges and progress of the work at Algiecel where they could study a photobioreactor built into a shipping container. The reactor was integrated into

the production of sustainable, low-carbon natural microalgaebased ingredients rich in protein, omega-3s, and vitaminsfor use in feed, food, and cosmetics.

A post-meeting survey revealed that the attendees all profited from the information received during different presentations and group work, but more importantly from personal meetings, idea sharing, and brainstorming with other participants.

Eva Kovacs, Eurofish, eva@eurofish.dk

[ EVENTS ] EUROFISHMagazine 3/202425

Study shows active sludge technology’s potential to treat waste from saltwater land-based fish farms

Making marine RAS more sustainable

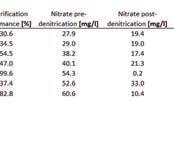

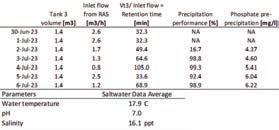

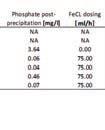

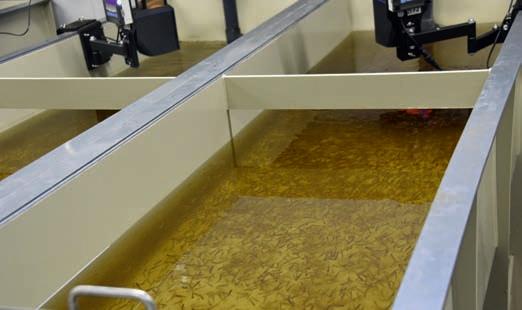

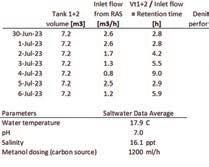

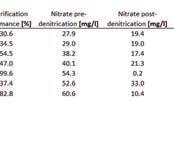

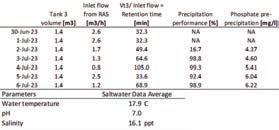

In a recent experiment Louise von Gersdorff Jørgensen from the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, together with Bent Urup, Jeremy Gacon, and Stefan Rathje Lund from Aqua-Partners ApS, Fredericia, treated the discharge from a saltwater recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) in a pilot active sludge system, applying a technology generally implemented in sewage plants. The scientists’ results were overwhelmingly positive with one reservation that they felt could easily be addressed.

From an environmental perspective, a Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) may not always be as sustainable as one might assume. On a RAS farm, cutting-edge technology eciently separates organic waste into sludge. It also transforms ammonia into nitrate, a form of nitrogen, which even in relatively high concentrations is harmless to the sh. Although water is recirculated, a small discharge volume (0.5-1 of the recirculated volume) remains. e internal cleaning process typically splits this discharge into two fractions: a sludge fraction from mechanical ltration, and a potentially low BOD (biochemical oxygen demand), particle-free fraction with high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen (in the form of nitrate). Although much reduced, these

discharges need further processing, otherwise the net discharge of phosphorus and nitrogen to the recipient will remain nearly equivalent to that of a ow-through sh farm. Various technologies have been developed for denitri cation and for the removal of phosphorus in freshwater. And the concentrated sludge from freshwater sh farms, has the potential to be used either as a fertilizer for agriculture or in biogas plants.

Saltwater RAS present unique issues

e challenge lies in nding e ective methods applicable to saltwater RAS plants. e sludge from marine systems contains a high salt content, posing dilemmas for its use as fertiliser or in biogas

plants. Furthermore, removing nitrogen through denitri cation under anaerobic conditions can lead to the production of sulphide—a toxic and notoriously

pungent compound. Nevertheless, as the discharge water from a RAS plant is minor compared to the discharge from a ow-through farm (or from cage farming), more

[ PROJECTS ]

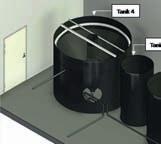

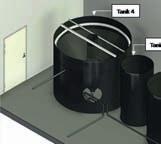

Figure 1, layout rendering of the small-scale active sludge implementation plan within Hanstholm RDF aquaculture facility.

Figure 2, the top of the sedimentation tank (Tank 4) showing accumulation of floating sludge under saltwater conditions.

Figure 3, the top of the denitrification tank (Tank 2) showing accumulation of floating sludge under saltwater conditions.

26

options are available for processing and cleaning. One tried-andtrue method for denitri cation is the active sludge technology used in sewage plants. Here, the sludge serves as the organic carbon source for denitri cation. is o ers cost savings by reducing the need for alternative energy sources like methanol and reducing the overall volume of the concentrated sludge generated. e consequence is a sludge fraction with a greatly reduced organic content that can no longer be used for biogas production. However, in the seawater scenario, the reduction in sludge volume produced, would be an advantage, since repurposing concentrated seawater sludge is more challenging.

Pilot

project hosted by

commercial producer of rainbow trout

e experiment took place at Royal Danish Fish (RDF), a company with a recirculating aquaculture facility for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Hanstholm,

Tank 1. Methanol input in Tank 1 is either increased or decreased depending on Tank 2 carbon requirement.

• Tank 3: Aeration tank for the removal of the nitrogen gas that results from denitri cation, and for increasing the oxygen level in general. In addition, within this tank iron chloride was added via a dosing pump to reduce the level of phosphate (phosphate precipitation) in the clean water outlet of the system.

• Tank 4: Sedimentation tank for the separation of clean water (top outlet) and sludge (bottom outlet). Sludge returned to Tank 1 to increase the level of particles and organic matter required for proper

denitri cation and/or sludge repurposing/collection.

e water source of the smallscale active sludge inlet was the mixed discharge from a single production section within RDF. is was pumped to Tank 1 of the small-scale active sludge system. e ow within the system started from Tank 1, then went to Tanks 2, 3, and 4. Finally, from Tank 4, the water ow is partially split with approx. 65 of the ow being skimmed o from the surface of Tank 4—the skimmed surface fraction considered to be the clean fraction, now free of particles, and the fraction supposedly suitable for discharging into a recipient (it was noted that this clean fraction proved not to be

Denmark. e small-scale active sludge installation consisted of four interconnected tanks (Figure 1) and a control system to manage various ows as well as oxygen levels. e installation was delivered, and testing protocols were developed by Aqua-Partners ApS. e active sludge system was allowed to mature for a few weeks, with RAS discharge water supplied to the installation before the experiment was launched.

e study involved the monitoring and analysis of various water parameters at multiple points within the experimental system, including the discharge water supply into the system, the outlets and within each of the four tanks.

• Tank 1: Denitri cation using organic matter from RAS farm outlet and from return ow of Tank 4. In addition, methanol (carbon source) was supplied by a dosing pump at a desired rate.

• Tank 2: Denitri cation using remaining carbon source in

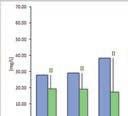

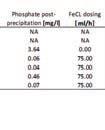

5, denitrification rate during testing days under saltwater conditions, including concentrations of nitrate before and after treatment, and the percentage of reduction obtained.