THE LOW IMPACT COASTAL SEGMENT SEEKS TO REINVENT ITSELF

THE FISH TRADE embraces digitalisation— gradually

INTERVIEW WITH FAO’S Audun Lem as GLOBEFISH turns 40 54

UKRAINIAN trader adapts by replacing seafood products with meat

THE LOW IMPACT COASTAL SEGMENT SEEKS TO REINVENT ITSELF

THE FISH TRADE embraces digitalisation— gradually

INTERVIEW WITH FAO’S Audun Lem as GLOBEFISH turns 40 54

UKRAINIAN trader adapts by replacing seafood products with meat

e low impact coastal shery in Denmark is characterised by vessels up to 17 m using gears such as gill nets, hooks, traps, fyke nets, and Danish seines that have minimal impact on the environment. e association cum producer organisation representing this segment promotes the interests of its members through its participation in Danish parliamentary committees, where it ghts to prevent small harbours from shutting down. At the European level the association has aligned with similar bodies in other countries to create awareness and further their agenda. Read more on page 32

e colour of salmonid esh varies from o white to deep red depending on the astaxanthin content of the feed. Astaxanthin is a plant pigment also found in phytoplankton and some crustaceans from where it makes its way up the food chain. Apart from imparting colour to salmon esh the pigment is also an antioxidant that prevents the fats in muscle meat from breaking down. In the body, some of the pigment is also converted into vitamin A which has anti in ammatory e ects. Astaxanthin may also have a bene cial e ect on the reproductive performance of salmonids. Read Dr Manfred Klinkhardt’s article about this important pigment from page 15

VeriFish, a Horizon-EU project, of which Euro sh is a partner, aims to encourage consumers to consider sustainability when they shop for sh and seafood products. To do this project partners will develop a set of veri able indicators on the health bene ts, sustainability, and climate impacts of di erent seafood products. ese indicators are expected to assist individual consumers, but also commercial enterprises, and policymakers, take decisions about consumption of sh and seafood. An app will be among the tools developed to promote use of the indicator framework. See more on page 23

e Estonian shing sector comprises several segments including the coastal shery, Baltic eet, the distant water vessels, and the inland eet. e pelagic species, Baltic herring and sprat, are the most important in terms of volumes and ensure Estonia is self su cient in the production of sh. Unit value of catches is highest for the distant water eet which targets species like red sh, northern prawn and Greenland halibut. But falling total catches present a challenge to the industry. One way of addressing it is by adding more value to the raw material. Read more on page 37

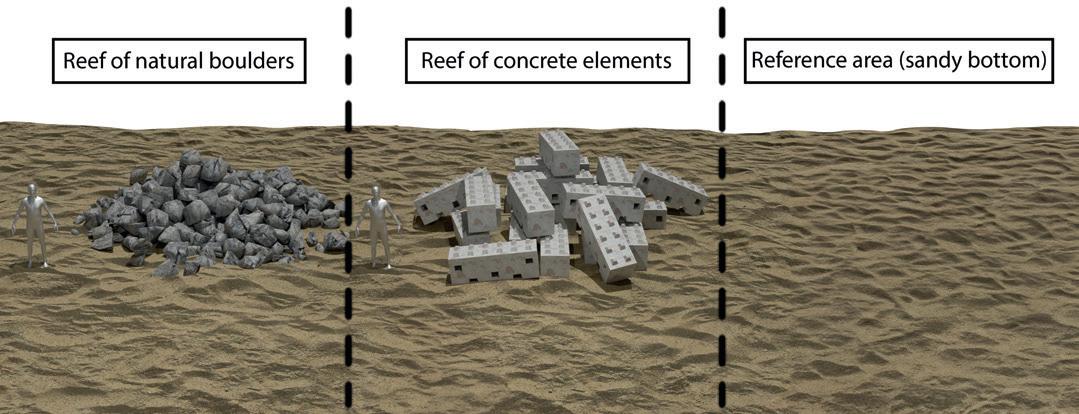

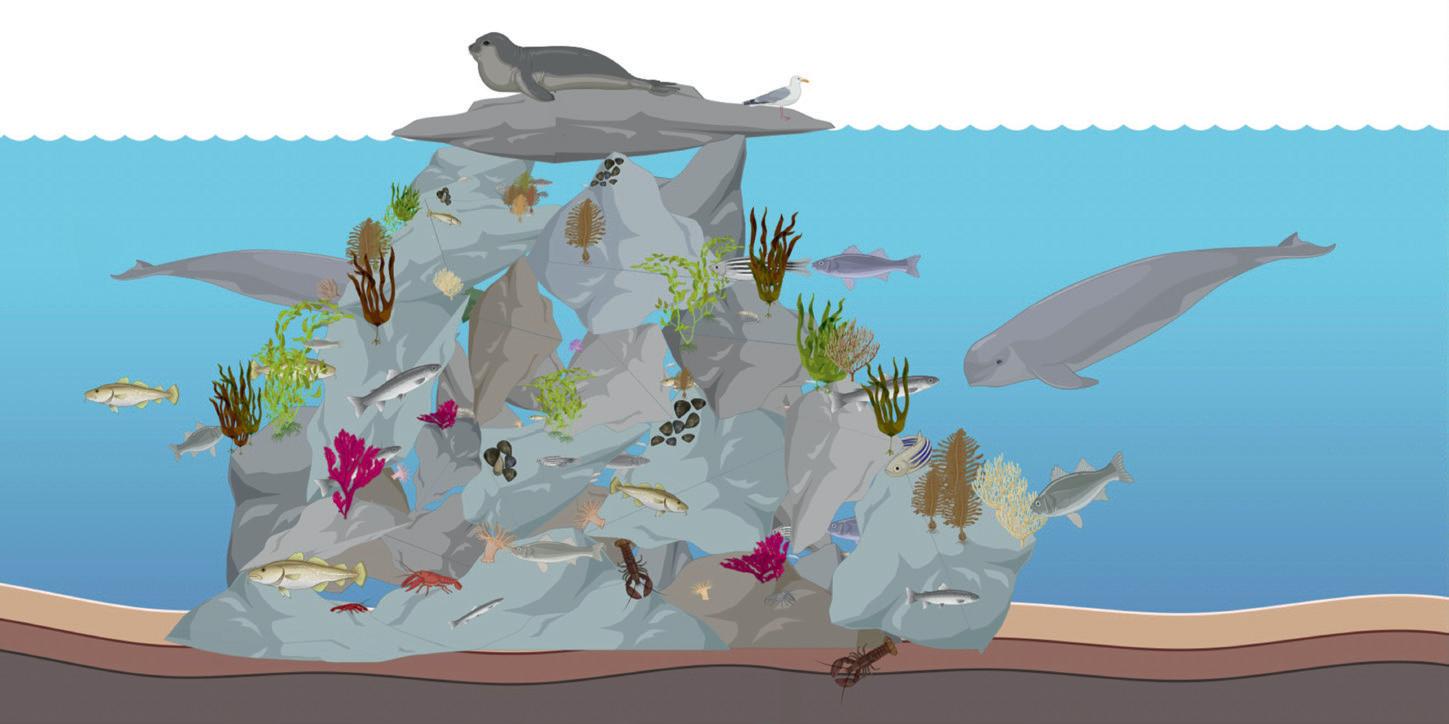

Improving the marine environment is one of the ways of increasing the resilience of sh stocks and researchers in Denmark are therefore studying the positive impacts of arti cial reefs. ese structures create breeding grounds and nurseries for many marine species which, in a virtuous cycle, attracts more sea life to the area, thus augmenting biodiversity. However, these developments do not happen overnight—timespans of a decade or more are common when it comes to the biological maturing of a reef. e researchers are also comparing the performance of reefs made of natural material with reefs of concrete. Read more on page 44

Women account for approximately a quarter of the employment in the sheries and aquaculture sector, where data is available. Large fractions of data from the sector (38 in marine sheries, 40 in aquaculture) do not disaggregate by sex, reports the FAO. While conditions for women have improved, they still lag men in terms of the proportion in full time employment and in wages. Women in the sector are also more exposed to violence. AKTEA is a European network that is trying to remedy some of the ills that a ict women in sheries and aquaculture. Read more on page 48

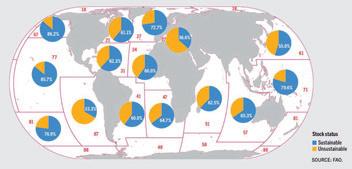

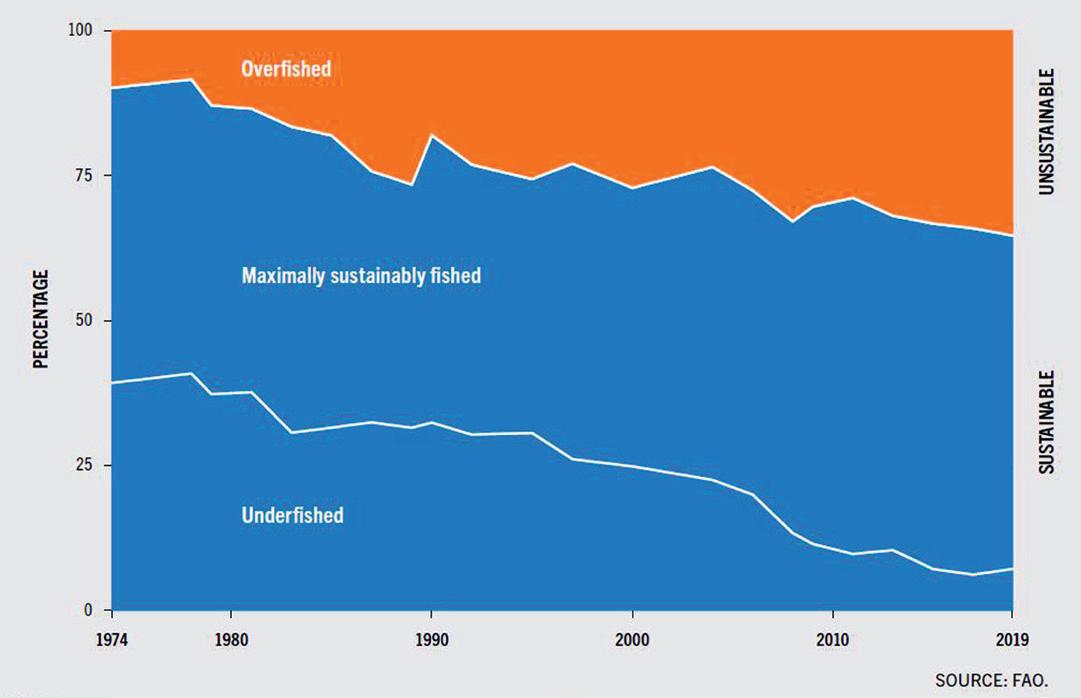

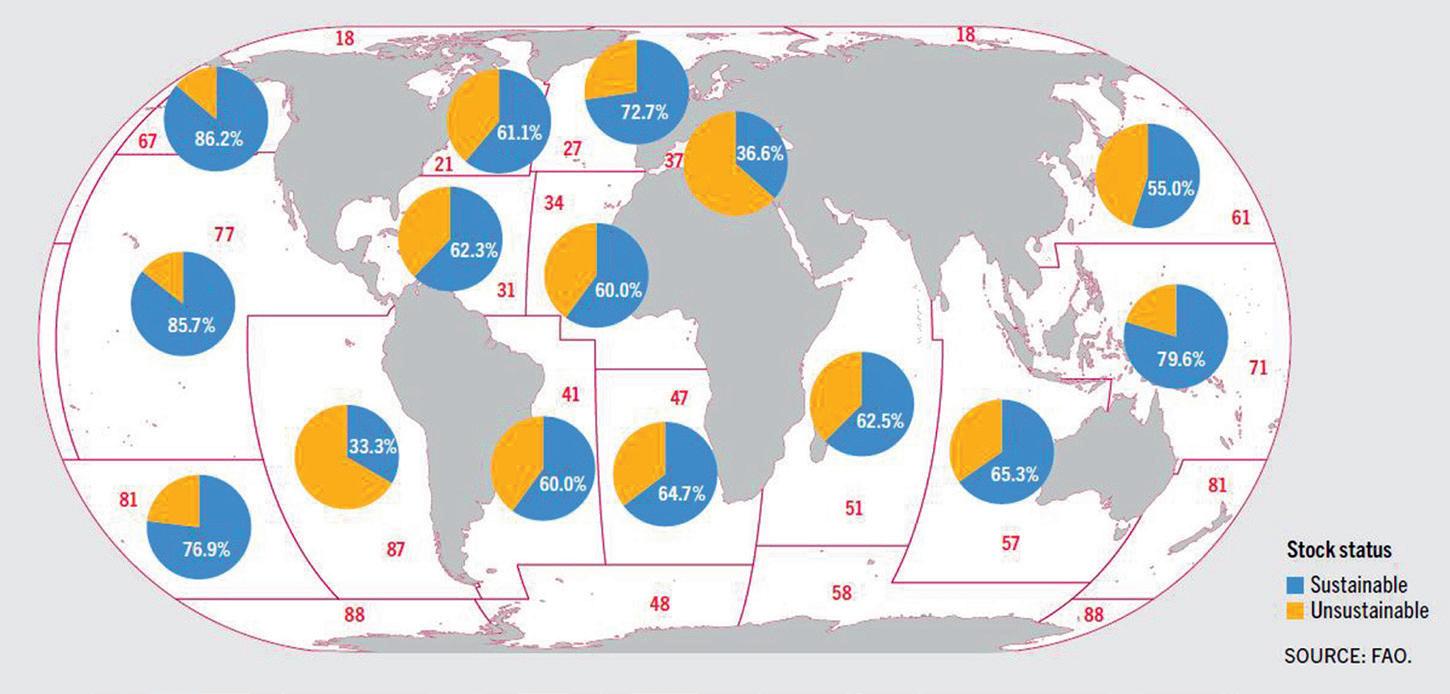

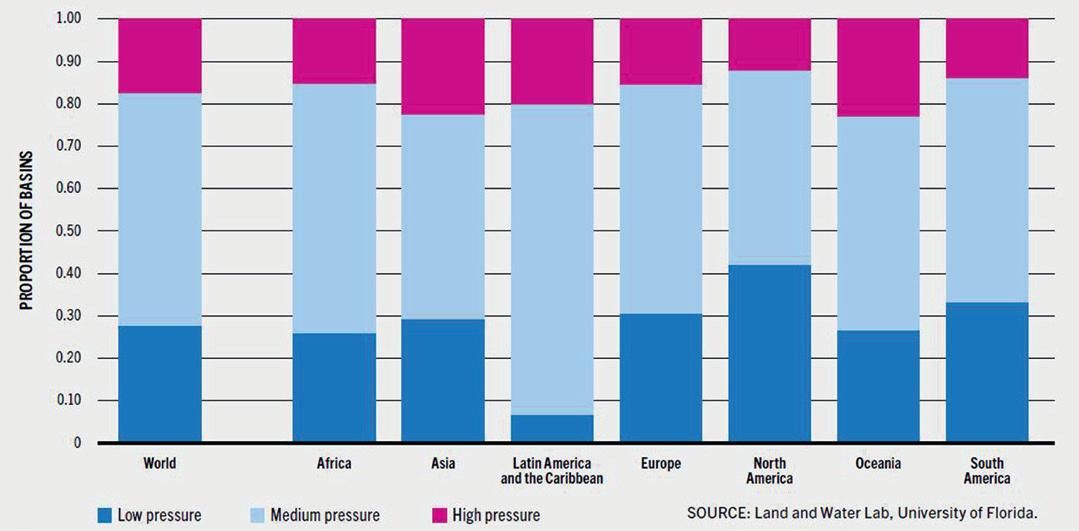

Data collected by FAO on capture sheries represents a huge and complex task with inputs from 240 countries, 26 shing areas, and covering 2,200 n sh species. Analysis of the data reveals that just under two thirds of resources are being shed sustainably, down from nine tenths in 1974. However, data collection remains a challenge in many countries, an issue that was discussed at a series of FAO-organised meetings in 2022. FAO is working to mobilise the resources to improve the situation, but until then relies on estimates using approved methodologies. Read more on page 50

6 International News

12 AQUA 2024, 26-30 August 2024, Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the place to be in late August!

14 Pavilion of Denmark at AQUA24, Copenhagen, Denmark, 26-20 August 2924

Danish cooperation and innovation for a stronger global aquaculture

15 A strong red colour is considered an important feature in terms of quality

The colouring of fillet impacts salmon sales

20 Italian startup deploys biotechnology to create better aquafeeds

Improving feeds through the use of insect meal

23 VeriFish seeks to improve sustainable seafood practices

Empowering consumers to make informed choices

27 Denmark must develop even further as a producer of high-quality food

Sustainability is both environmental and economic

29 Blue Rock combines angling ponds with noble crayfish production

Crayfish for consumption and restocking

32 The Danish coastal fishery faces challenges but also opportunities

Adapting to new realities

35 A Danish vocational school exploits the climate and health benefits of macroalgae

Promoting seaweed consumption to the masses

37 The fisheries sector plays multiple roles in Estonian society

Resilient in the face of threats

41 Consumption trends of fish and seafood in Estonia

High prices are a deterrent

Cover picture courtesy: Aris Adlers

42

Dam-mapping exercise contributes to improving situation for fish fauna

Healthy fish stocks depend on accessible spawning grounds

44 Two projects seek to shed light on artificial reefs’ impact on biodiversity

Marine restoration in Danish coastal waters

48 AKTEA fights for the rights of women in fisheries and aquaculture

Supporting gender equality across Europe

50 More overfishing despite increasing sustainability? FAO analyses depend on estimates

54 Are digital trading platforms for fish worth it? Internet sales expand marketing opportunities

58 Brim sees innovation as key to meeting its commitments Affecting every aspect of the company

60 Ukraine’s seafood business: Impacts of Russia’s war against Ukraine Hostilities affect ratio of meat and fish products

Four decades of analysing the global market for farmed and wild aquatic products

Invasive species of crayfish native to America have been slowly spreading in the freshwater bodies within countries bordering the Baltic Sea, but now the problem has taken a critical turn. The invasive species, starting with signal crayfish but recently joined by at least three other nonnative species, are similar in many respects to the Baltic region’s native European crayfish (Astacus astacus) except in one potentially disastrous respect: they carry a plague to which they themselves are immune but causes a nearly 100% mortality rate for the European species. Scientists in Estonia are struggling to find preventive measures to save European crayfish. The largest problem is the signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus), which first appeared in Estonia in 2008. Another invasive species, the colourful marbled crayfish, is believed to have been released by pet owners, while other species may have invaded from ship ballast discharges. They are all immune to the plague.

Researchers at Estonia’s University of Life Sciences have fought the

crayfish invaders—and the plague they carry— for years without success, using a variety of tools. Poison has been tried, but in flowing freshwaters that signal crayfish prefer, the poison is merely dissipated. Nets like those used to harvest local crayfish do not capture young invaders that escape.

“Electro-fishing,” which sends jolts of energy into the water, doesn’t reach the crevices in rocks where crayfish dwell. More promising efforts include using eels to find and eat small crayfish in tiny hiding places, while the larger ones can continue to be trapped. But the trapping must be more intensive than now, the researchers say, and more public support is required. “The problem is becoming increasingly serious each year,” says Katrin Kaldre, a junior professor of aquaculture biology at the University of Life Sciences. “We practically discover a new signal crayfish outbreak every year.”

The project at the University of Life Sciences includes a public awareness campaign. “We taught in schools and at festivals how

Signal crayfish were first introduced to Sweden in 1960 and quickly spread to other European countries. They were chosen because they were resistant to crayfish plague and considered a viable alternative for aquaculture. Signal crayfish are highly competitive and aggressive, leading to the displacement of native crayfish species.

to distinguish between different crayfish species,” says Kaldre. “It’s important to raise awareness that not all crayfish are the same; you cannot simply move them from one body of water to another.

Such actions have consequences.” People walking near water bodies are encouraged to photograph any crayfish they observe and report them through the national information phone line 1247.

The Fishery Research Center of MATE AKI (HAKI) hosted the 48th Fisheries Scientific Consultation in Szarvas on June 5-6, 2024. As a premier event for Hungary's aquaculture sector, this annual gathering highlighted innovative development opportunities crucial for domestic fish farming. This year's conference was particularly timely, aligning with the forthcoming MAHOP Plusz initiatives and Hungary's presidency of the Council of the European Union (1 July – 31 December 2024), which entails significant fisheries management responsibilities.

Discussions, presentations, and speeches at this year’s Fisheries Scientific Consultation, an annual conference in Hungary, focused on innovative developments in the fish farming sector.

Reflecting the importance of these themes, the event attracted nearly 170 attendees over the two days. During the plenary lectures György Zsolt Papp, Deputy State Secretary responsible for rural development programs and head of MAHOP IH, presented the planned measures under the MAHOP Plusz program. Mónika Bojtárné Lukácsik, group leader at the Institute of Agricultural Economics, detailed the importance and background of the Data Collection Framework (DCF) for fisheries, which is being initiated as part of MAHOP Plusz. Péter Lengyel, fisheries attaché for the Ministry of Agriculture at the EU,

discussed the future development possibilities for aquaculture in relation to the upcoming EU presidency period.

A highlight of the event was the round-table discussion, where experts from HUNATiP and other participants collaboratively explored innovation opportunities and challenges in the domestic aquaculture sector. The discussion underscored HUNATiP's commitment to integrating Hungarian aquaculture into European innovation processes, particularly in precision farming, process regulation, and digitalization. These innovations

Consistent overfishing of Northeast blue whiting, a principal ingredient in salmon feed, threatens the environmental certification of the species. The loss of this certification would, in turn, risk the certification of fish production dependent on such feed and will cost consumer sales, as told by an array of firms involved in feed and salmon farming to the governments of Norway and the Faroe Islands. The European Commission has accused Norway and the Faroes of refusing to meet and agree on country-specific allocations of the overall quota on the blue whiting stock that is set based on advice by the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES), the body which the EU and other fishery management authorities rely on for sound biological advice as to resource stock conditions. Other concerned harvesting nations, including other EU Member States and the UK, follow such

are vital for enhancing the sustainability, competitiveness, and resilience of fish farming. The dialogue emphasized that innovation is crucial for the successful implementation of the MAHOP Plusz program. Following the plenary sessions and round-table discussion, domestic and international researchers presented their latest findings and innovations through scientific lectures and posters. The conference featured several sections, including technology and feeding; reproductive biology and genetics; fish health and hydrobiology; and a new focus on the societal and environmental aspects of fish

farming. This interdisciplinary approach was well-received, offering comprehensive insights into the various facets of aquaculture research.

The 48th Fisheries Scientific Consultation in Szarvas once again proved to be a significant event for the aquaculture community, fostering knowledge exchange and highlighting the critical role of innovation in the future of fish farming. The discussions and presentations at the conference have set the stage for substantial advancements in the sector, aligned with national and European strategic objectives.

quota advice on blue whiting, while the two offenders have refused to agree on their countryspecific quotas from the total fishery quota for all countries and continue to heavily fish the resource.

In such criticism, the EU has been joined by the Northeast Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group (NAPA), an alliance of more than 70 companies including salmon farmers Mowi and Scottish Sea Farms, retailers Asda, Marks & Spencer, Tesco, Waitrose, Morrisons, Aldi, and Co-op, and feed producers Cargill, BioMar, Skretting, and Cooke Aquaculture-owned Northeast Nutrition.

NAPA blames Norway and the Faroes for their farmers and feed producers facing the prospect of refusing blue whiting because of the fishery’s loss of sustainability certification by the Marine Stewardship Council’s “Blue Label” mark of approval. This ultimately

The history of blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) utilisation highlights its transition from a bycatch species to a crucial resource for both human consumption and aquaculture feed.

risks the loss of certification of salmon grown with feed from this blue whiting fishery. In turn, a loss of salmon certification will alienate a large segment of European consumers for whom environmental certification is a priority when buying seafood. NAPA is joining the EU Commission in pressuring the two violating countries to improve their fishery management

activities to align with their responsibilities: in particular, to agree to stop overfishing their blue whiting resource. Charlina Vitcheva, the EU DirectorGeneral for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, said direct blame for the certification status of the blue whiting stock lies with Norway and the Faroe Islands, while other countries have not acted irresponsibly.

Seals everywhere are voracious competitors for the fish that humans catch and farm. They are marine mammals and are thus protected by the EU and other governments around the world, protections which date back decades to when marine mammal populations were depleted. But for seals at least, this is no longer a problem for them, it has become a problem for harvesters. Seals’ burgeoning numbers are causing serious damage to fishermen and aquaculture. In Latvia, seals eat 2-3 times as many fish as fishermen catch, often taking mortal bites out of fish that die a wasteful death or spread the resulting infection in their wounds to other fish. They also tear up nets and allow escapements. In Latvia and other Baltic countries,

fishermen are compensated for lost fish and damaged gear, “But,” says Normunds Riekstiņš, director of Latvia’s Fisheries Department at the Ministry of Agriculture, “of course this is not a solution and, in principle, more and more compensation has to be paid and less and less is caught.”

Fishermen and their representatives have worked for decades to find solutions to the seal problem, but it keeps growing. Recently, an association of 74 Latvian harvesters, Mazjūras zvejnieki, has stepped up pressure on government with a proposal to allow some harvesters the right to kill seals, enough to partly alleviate the problem and the damage that seals cause. The idea is to

limit the seal hunt to those which come in close proximity to harvesting gear and fish. Cīrulis, a representative of coastal fishermen, claims that Latvia is the only country where fishermen are not allowed to hunt seals. In Estonia, for example, protective hunting is allowed. Support from authorities responsible for the environment would be helpful to their cause, and decisions on proposals to allow seal hunting are under consideration by Latvia’s Nature Conservation Agency and other responsible authorities.

FISH4ACP has announced the Blue Food Forum in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to be held 12-13 September 2024. The global forum will focus on sustainable practices in aquatic food value chains. Supported by the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the European Union (EU), and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), FISH4ACP pursues sustainable fisheries and aquaculture in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific (ACP). The Blue Food Forum contributes to this mission by utilising momentum generated by the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit, which inspired global interest and action in transforming food systems. The forum enables FISH4ACP and related

initiatives to share their knowledge with partners, value chain experts, representatives, and supporters. Simultaneously, discussions regarding the national and global pathway to developing a sustainable aquatic food value chain will be encouraged.

FISH4ACP established three ideal outcomes of the Blue Food Forum. First, to understand how aquatic food value chain development intersects with the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda, the European Union’s Green Deal, FAO’s Blue Transformation agenda, and other international policies geared toward sustainability; to build on successes and learn from past experiences in aquatic food chain development in order to identify opportunities for expansion; and, lastly, to identify effective avenues for investment that

will increase aquatic food value chain development. Innovation in their value chain approach, FISH4ACP found, has carved a path toward sustainable fisheries and aquaculture in the ACP region that promotes inclusivity, food security, and minimal environmental impact. Collaboration with both local communities and stakeholders is integral to understanding how aquatic food

value chains promote economic, sustainable, and social growth across the world. At the Blue Food Forum, attendees will explore this approach through panel discussions and opportunities to engage with stakeholders.

Further updates and information on the Blue Food Forum can be found on the FISH4ACP website at www.fao.org/in-action/fish-4-acp.

Exporting feed, equipment, and solutions to the global aquaculture industry is an important part of the Danish economy. Therefore, it is crucial that the industry has the best conditions to ensure continued development towards increasingly sustainable food production based on the best and most energyefficient technologies.

To strengthen the overall voice of aquaculture and create the best possible coherence for the players in Danish aquaculture, the two member organizationsDanish Export Association and AquaCircle - have merged and now will operate under the name Danish Export - Fish Tech. This ensures that all relevant players in the industry now have a single entry point for export promotion,

commercial activities, and political advocacy.

The export network Danish Export - Fish Tech brings together Danish feed, equipment, technology, and service suppliers within aquaculture, including turnkey suppliers of systems, manufacturers of small components, feed producers, and suppliers of processing equipment. In addition to strengthening exports among companies by organizing export promotions and networking activities, the Danish Export Association will now also play a more prominent role in political advocacy with the merger with AquaCircle.

It is important that we can ensure the best possible conditions for industry players by creating a stronger voice together.

The merger between AquaCircle and Danish Export – Fish Tech was announced at an aquaculture networking meeting in Copenhagen and organized by Danish Export – Fish Tech.

Our members in Danish Export – Fish Tech are dependent on a strong aquaculture industry in Denmark to be able to develop in the export markets. Therefore, I am pleased that through the merger with AquaCircle we can also create a stronger political voice, says Martin Winkel Lilleøre, Head of Fish Tech at Danish Export Association.

Martin Winkel Lilleøre, Head of Fish Tech, Danish Export Association, maw@danishexport. dk, +45 60 20 85 57

Mette Kristensen, PR & Communications Consultant, Danish Export Association, mek @danishexport.dk, +45 28856430

The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of a country is a maritime boundary it sets, under the auspices of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), seaward from its land border to 200 nautical miles from shore or to the EEZ of a neighbouring state, whichever is less distant. Rights provided within an EEZ include management of fisheries. There are many disputed EEZs around the world where multiple countries claim a single overlapping area—which often results in fishery mismanagement when two countries’ rules conflict. Fortunately, there is one less problematic EEZ dispute thanks to a recent agreement between the Adriatic nations of Italy and Croatia. After years of noncooperation, ending in 2022 with an agreement

on paper (to be ratified by governments), the two countries agreed at a bilateral summit to each ratify the EEZ agreement, putting it into law in their land and at UNCLOS.

The long mismanagement and overfishing had brought key fisheries such as hake and nephrops in the northern Adriatic to the point of collapse. By the mid2000’s, the crisis drew in the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to assist with sustainable fisheries and aquaculture practices. The crisis had turned Croatia into a net fish importer from an exporter. “By defining this [EEZ] line,” said Croatian Minister of Foreign and European Affairs Gordan Grlić-Radman, “Croatia

In 2022, Croatia had 7,501 vessels in its commercial fishing fleet, where small-scale coastal fishing boats less than 12 metres represented over 95%. However, the largest percentage of catches (up to 90%) are made by purse-seines that target small pelagic fish (sardine and anchovy), representing 3% of total fishing vessels. Pictured, a Croatian fishing vessel.

and Italy will reinforce their cooperation in the Adriatic Sea, as well as our common cultural, historical, geopolitical heritage.” The

arrangement includes a fisheriesrestricted area (FRA) called the Jabuka/Pomo Pit. “The Jabuka/ Pomo FRA has been promoted

as an example of best practice in fisheries management and an example that needs to be followed in all steps, noting that its

effectiveness also rests on the fact that all stakeholders supported its proclamation as a joint initiative in the region,” GFCM

The 17th edition of Polfish —the only trade fair in Poland and one of the largest in Central and Eastern Europe focused on the fish industry—is coming up. Among the exhibitors at the fair, are Polish leaders in imports and processing of fish and seafood from fresh, smoked, salted, and frozen to ready-to-eat. Manufacturers of processing equipment—cutting, filleting, smoking, packaging, and refrigeration—producers of systems for maintaining cleanliness at processing plants, catering facilities, and shops, manufacturers of flooring and drainage systems, providers of consultancy services, processing plant designers, producers of fish shop equipment, and distributors of health and safety

products will also be in attendance. The full list of exhibitors is available at: www.polfishfair.pl.

Polfish draws thousands of local and international visitors, including owners and managers of retail and wholesale stores, supermarket chains, discount stores, HoReCa sector, and more. The event brings together key players in the fish industry to create an arena for sharing experiences, showcasing innovations, and establishing strategic partnerships. An important part of the exhibition is the business programme. Participants can take part in conferences, debates, and discussions, as well as award ceremonies for the Mercurius

Fishery Officer and Subregional Coordinator for the Adriatic Sea Marin Mihanović explained. Officials hope that ratification of this agreement will inspire other Mediterranean countries entangled in similar disputes to follow suit.

As at previous editions, the best Polish chefs will surprise the audience with innovative and trendy fish dishes.

Gedanesis competition, where the best products in the categories Fish Product and Technology will be awarded. Polfish is an important event for the industry and a meeting place for professionals from Europe and beyond.

The deadline for booking the exhibition space is 2 August 2024. More information at: www.

polfishtargi.pl/en/applicationfor-participation/

About Polfish 2024: Dates: 11-13.09.2024

Opening hours: Wednesday and Thursday 10:00-17:00, Friday 10:00-16:00

Venue: AMBEREXPO, Żaglowa Street 11, Gdańsk, Poland

Further information: polfishtargi.pl

The small but energetic trade show Future Fish Eurasia—Turkey’s one and only seafood industry trade show—always attracts hundreds of buyers and sellers of fish, shellfish and the machinery and equipment needed to produce and process them for market. The 11th edition of this biennial event returns to its home at a 10,000 sq. m hall in the seafood city of Izmir, Turkey, on 10-12 October 2024.

The show attracts key players in both Turkey’s seafood industry and in fish-related businesses throughout the region, along the shores of mighty rivers, and across the four seas surrounding

Turkey: the Mediterranean, Black, Aegean, and Marmara. Besides globally-known fish farming companies producing the country’s famous seabream, seabass, rainbow trout, and sea trout, exhibitors in past events have included manufacturers of farming and harvesting machinery. The event features various types of equipment, industrial products, and business services needed to prepare and sell fish on the marketplace.

For European business people wishing to develop contacts for marketing Turkish seafood abroad, or to expand their own business in Turkey and the region, the 2024 edition of Future Fish

As Turkey’s only trade fair for the industry and the leading event in the region, Future Fish Eurasia is the gateway to emerging markets.

Eurasia is an ideal opportunity. Already, more than 200 exhibitors are signed up—the time to reserve a good booth is now, and to do that

(or to experience Future Fish Eurasia as an interested visitor), fill out the paperwork on the event’s website at www.future-fish.com.

TO Smárinn Kópavogur Iceland 2024 SEP

We look forward to welcoming you in September

The Icelandic Fisheries. Seafood & Aqua Exhibition hosts the latest developments from the industry showcasing new and innovative products and services, covering every aspect of the commercial fishing industry from catching and locating to processing and packaging, right through to marketing and distribution of the final product.

For more information about exhibiting, visiting or sponsoring, contact the events team

Visit: Icefish.is

Contact: +44 1329 825 335 or Email: info@icefish.is

AQUA 2024, 26-30 August 2024, Copenhagen

AQUA 2024 is co-organised by the European Aquaculture Society (EAS) and the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) and is held every six years. AQUA 2024 has been organised with the support of our local partners, the Danish Export Association Fish Tech, ICES, DTU AQUA, the University of Copenhagen, Eurofish International Organisation, and the Copenhagen Convention Bureau.

This year’s edition includes a scientific conference, trade exhibition, industry forums, workshops, student events, and receptions. The event will highlight the latest aquaculture research and innovation to underpin the continued growth of this sector. It will be a showcase for Denmark and its innovation leadership in several key technologies crucial for future aquaculture, but also a meeting and exchange platform

Dag Sletmo is a Senior Vice President of the Seafood Division at DNB - the leading bank in Norway and the largest bank globally in salmon farming with clients in Norway, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Scotland, Canada, Chile, and Australia.

Prior to joining DNB, Mr Sletmo worked in Cermaq, the global salmon farmer, and ABG Sundal Collier, a Nordic investment bank. He holds an MBA from Columbia Business School in New York and has studied economics and philosophy at NHH and UiB in Bergen.

for experts from around the world. The total expected participation is 2500 attendees from 90 countries.

is the overarching theme

The scientific conference will include more than 60 sessions covering all aspects of aquaculture research. To put some

general highlights to the conference theme, the organisers included two special plenary sessions in the schedule.

On August 27th, Dag Sletmo from DNB will give an opening speech “Analysing the Future.” According to FAO, sustainable aquaculture must increase by 75% by 2040 to help limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C. Mr Sletmo will discuss the financial investments needed, focusing on new

Signe Riemer-Sørensen is Senior Researcher and Research Manager for Analytics and AI in SINTEF. Her research evolves around overcoming challenges for implementing machine learning and artificial intelligence in a broad range of industrial settings where physics plays a role and data is often sparse and noisy. The solutions integrate domain knowledge into the AI, in so-called hybrid AI, fostering robust, explainable and trustworthy models.

technology, improved practices, and regulations to boost production while reducing environmental impact. He will also address the industry’s reliance on government regulations and social license, and how to finance these initiatives, with a focus on salmon and general aquaculture.

On August 30th, the second plenary will be given by Signe RiemerSørensen from SINTEF, offering

her views on “AI with Knowledge.” Large language models have democratized AI. Co-pilots and chat-bots are changing most office jobs, but despite their impact, they will not revolutionize aquaculture. For that, we need completely different types of AI. Through examples from aquaculture and beyond, Ms Riemer-Sørensen will explain the challenges, provide intuitive insights into AI, and introduce the latest developments on industrial AI and their potential in aquaculture.

A regular feature of EAS events is the Industry Forum and the Innovation Forum, and these will take place during AQUA 2024.

The Industry Forum will be held all day on August 27 and will address the main event’s theme, with key questions about the status and future of the sector with regards to adaptation to climate change, mitigation of its effects, circular approaches, and other externalities.

The Innovation Forum, “Exploring Inter-Regional Collaboration & Innovation Transfer Vehicles for Aquaculture.” will be run all day on August 28. It will examine inter-regional collaboration for innovation transfer within EU policy and globally, featuring four sessions with presentations and discussions about the development of sustainable European aquaculture, practical implementation of innovation

transfer, the role of academic and research networks in such transfer, and strategies for its funding and facilitation.

AQUA 2024 will feature special sessions bridging science and industry, covering topics such as Atlantic salmon health assessment, the EUROshrimp Forum, future aquafeed supply chains, host resistance to sea lice, light effects on fish and other organisms, and IMTA with low-trophic aquaculture.

The AQUA 2024 exhibition will host more than 240 booths from suppliers and operators covering all aspects of aquaculture

production at the global level. All coffee breaks and happy hours will be held in the exhibition hall to maximise interaction between experts and visitors, of which some 1,400 are expected.

The organisers have arranged several tours on 26 August: to high-tech facilities at the Danish Technical University (DTU) National Food Institute, OxyGuard International’s Danish Headquarters, Marel Progress Point Global Demo Center, and to the Danish National Aquarium.

To find more information about AQUA 2024 and to register, please follow the link: https://www. aquaeas.org/

Pavilion of Denmark at AQUA24, Copenhagen, Denmark, 26-20 August 2924

Striving to provide the most efficient and sustainable solutions for global aquaculture, Danish companies have strong cooperation throughout the entire value chain and innovate continuously to meet the needs of fish farmers worldwide.

Each year the 200 Danish farms produce about 56,000 tons of farmed fish and shellfish. Since the domestic market is small, Danish companies supplying the aquaculture industry have been forced to compete internationally— something they have managed very successfully. From turnkey providers and feed producers to suppliers of pumps, filters, and fish processing equipment, Danish suppliers are highly recognized worldwide and have a strong position in markets abroad thanks to their energyefficient, sustainable, and highend solutions.

Sustainability and efficiency through decades of innovation and cooperation

Danish strengths such as sustainable solutions, energy efficiency, and high-end products are seen across industries and apply to aquaculture as well. And Danish suppliers strive for solutions that increase the sustainability of aquaculture. This takes knowledge and experience, strengths built upon years of close cooperation within the industry. Equipment manufacturers work closely with fish farmers and the turnkey providers, just as the feed producers collaborate with fish farmers to optimise their products for

The strengths of Danish suppliers lie in providing sustainable, efficient, flexible, durable, and innovative solutions for various industries, and for aquaculture in particular.

more efficient, sustainable, and disease-free farming.

As research and development require resources as well as skilled employees, Danish products might not be the cheapest on the face of it. But in the long run, Danish solutions might be the most cost-effective.

For instance, fish feed producers have developed feeds supporting higher seafood production. Technology providers bring the most energy-efficient and long-lasting solutions to the table, securing

lower energy consumption, less maintenance, and a longer life span, resulting in a lower total cost of ownership. Furthermore, processing equipment providers have developed machinery that not only handles the processing, packaging, and freezing of the product fast and efficiently, but also maximises the yield from the raw material.

As aquaculture output increases all over the world, Danish companies need to stay updated on markets and upcoming projects. Also in this process, the companies benefit from close cooperation throughout the value chain. For example, turnkey providers can introduce sub-suppliers to new

markets. But to stay relevant to the industry, Denmark needs to keep pushing to remain a leader in greener and more efficient solutions to benefit the whole aquaculture industry.

Danish companies will literally stand together at the AQUA 2024 exhibition in Copenhagen in August. The Danish Export Association organises the Pavilion of Denmark, gathering 27 companies from the whole value chain to meet new and old international business partners and to show the exhibition visitors what Denmark is all about.

A strong red colour is considered an important feature in terms of quality

Recently, I witnessed a strange incident while visiting the fish counter of my favourite supermarket when a customer was loudly complaining about the intense vermilion colour of a salmon fillet on display: “The salmon farmer has once again gone way too far and used far too much colour! The fillet looks completely unnatural!” The sales staff were overwhelmed by this situation. It would have been easy to take the wind out of the angry lady’s sails, as the fillet in question came from sockeye salmon, a wild Pacific salmon species that is not produced in aquaculture and is certainly not artificially coloured, but develops that deep red fillet colour solely through its natural diet.

However, this grotesque scene draws attention to a topic that is widely discussed and unfortunately often misunderstood by large parts of the public. Fuelled by social media and self-proclaimed experts, new claims and myths about the red colouring of salmon meat are constantly emerging. It is not uncommon for this to involve deliberate manipulation with food colouring and consumer deception. In the US, packaged farmed salmon must even be officially labelled with the phrase ‘added colour’ under FDA disclaimer guidelines, leading many consumers to believe that farmed salmon is somehow artificially coloured. In fact, both wild and farmed salmon get their colour in the same manner, i.e. exclusively from their diet. The red colouring of muscle meat is not caused by artificial colouring, but by carotenoid molecules, which also occur in nature. Of the more than twenty carotenoids found in salmon fillets, astaxanthin is by far the most important, as it accounts for over 70 per cent of the total pigment content in Atlantic salmon. Astaxanthin (the name is derived from the former Latin name of the lobster Astacus gammarus) is actually a plant pigment that

also finds its way into numerous animals through the food chain. It is found in yeasts, microalgae and other phytoplankton, carrots, many crustaceans such as krill, shrimp, lobsters and crabs, and even in the plumage of flamingos.

Colour sells when buying salmon

The red colouring of the salmon fillet is a typical visual feature of this fish, which is perceived by many consumers as a criterion of value and quality and is preferred when shopping. Intense red is often even considered an indication of naturalness. The preference for strong red is particularly strong in Asia, where it influences both the acceptance and the price of salmon products. The average astaxanthin content of Atlantic farmed salmon varies between 6 and 8 mg/kg of fillet meat. The Japanese market tends to favour wild Pacific coho and sockeye salmon, which have astaxanthin contents of up to 25 mg per kg of fillet.

Salmon and other salmonidae are among the few fish species that can store astaxanthin in its pure form. They store the pigments not only in their muscle meat, but also in their skin and

in their eggs, which then acquire a yellowish to orange-red colour and protect the embryos from overly intense UV light. The second important colouring pigment besides astaxanthin is canthaxanthin, which is also fat-soluble and comes either from natural sources (e.g. plants, fungi and crustaceans) or is produced synthetically, for example, as food

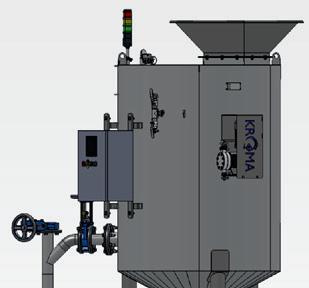

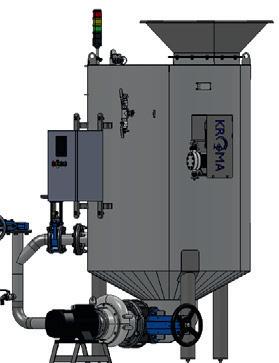

Kroma promotes a zero-waste policy

Astaxanthin, which is added to salmon feed to pigment the fillet, is now often synthetically produced.

additive E 161g. Canthaxanthin is a controversial substance that is suspected of having pathogenic effects and is therefore subject to strict limits. In natural products such as crustaceans, however, the amounts are so small that there is no risk to health. Furthermore, canthaxanthin may continue to be used in animal feed albeit in limited quantities. The Scientific Committee on Animal Nutrition of the European Commission has set the maximum concentration at 25 mg canthaxanthin/kg feed for salmonidae.

Astaxanthin and other pigments not only give salmon its red colour, but are also essential nutrients that ensure health and growth. For example, astaxanthin acts as a powerful antioxidant that protects the fats in muscle meat from breaking down, stimulates the immune system, and protects body tissue from oxidative damage. The antioxidant effect of pure astaxanthin is said to be 100 times stronger than that of vitamin E, which is contained in some human food supplements. Part of the ingested

astaxanthin is converted in the body into vitamin A, which supports cellular respiration and has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. For example, tests on Atlantic salmon have shown that intestinal inflammation, which often occurs when soy bean meal is fed, can be prevented by adding the astaxanthin-containing microalgae Chlorella vulgaris to the feed. Astaxanthin is also believed to have a significant effect on the reproductive performance of many fish species, such as egg production and sperm quality, as well as the fertilization and survival rates of the eggs. Pigments are therefore much more than just simple colouring agents because they also have important biological functions.

The salmon cannot produce the red pigments themselves, only absorbing them through their food. In aquaculture today, most fish are fed formulated feed, which is a mixture of various components tailored to the needs of the fish. Many of these contain insufficient or partially destroyed carotenoids, as these pigments are extremely sensitive. They can lose their functionality due to high temperatures and

pressure during the preparation of the raw materials or incorrect storage of the feed pellets and must therefore be added from suitable sources when mixing the feed. This can perhaps be compared to the intake of nutritional supplements that some people use to supplement their diet. Astaxanthin, which is available over-the-counter at the chemists and elsewhere, brings health benefits not only to salmon, but also to humans. It has an antiinflammatory effect, increases the production of antibodies and the proliferation of immune cells. It is fairly well established that astaxanthin protects against stressrelated cardiovascular diseases, certain types of cancer and diabetes and helps prevent obesity. Preclinical studies suggest that astaxanthin can also regulate the gut microbiome. However, anyone who regularly eats salmon or other red-fleshed salmonidae can easily do without dietary supplements containing astaxanthin, as the fillet of these fish contains enough of these pigments. In addition to omega-3 fatty acids and highly digestible protein with all essential amino acids, this is an additional argument in favour of regularly eating these fish.

In principle, the carotenoids used in salmon feed can be produced from natural sources such as bacteria, fungi, algae and plants or from shrimp shell waste. However, this is complex and expensive (naturally-sourced astaxanthin is four times more expensive than the synthetically produced pigment). In addition, it would be very difficult to meet the immense demand of aquaculture from natural sources alone. This is why feed producers mainly rely on synthetically produced astaxanthin, which is nature-identical, fully biologically effective and very easy to dose. Carophyll Pink is particularly often used in salmon aquaculture as a colourenhancing feed additive, which has been on the market since 1988. It contains antioxidants and a colour-enhancing canthaxanthin carotenoid supplement that significantly increases the colour of the fillets and fish skin. At a dosage of 50 grams per ton of feed, a noticeable improvement in colour can be seen after just two weeks.

In recent years, the desire of many consumers for salmon

to be raised in a more natural, quasi-organic way has led to an increased search for natural sources of astaxanthin. The focus here is on microalgae, which produce pigments in addition to polysaccharides, sulfolipids and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Green algae such as Chlorella sp. and Tetraselmis sp., for example, are rich in chlorophylls and carotenoids. Although relatively little is currently known about how microalgae, many of which have high antioxidant capacity, affect salmon health, some species are already being used with good success in salmonidae feed. For example, the green freshwater microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis (blood rain algae), which is considered an excellent source of astaxanthin for salmon and trout.

In the organic salmon sector, yeasts of the genus Phaffia have been used as natural sources of astaxanthin for some time. The species Phaffia rhodozyma and Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhou s are particularly noteworthy. Both produce astaxanthin as the main pigment, although only

in relatively small quantities, which makes the natural Phaffia pigment still quite expensive. Therefore, biotechnological methods are being used to increase the yield in order to make the production process cheaper. Several yeast mutants that are involved in carotenogenesis and give the colonies a strong red pigmentation have already been isolated.

Some types of bacteria are also potential sources of natural pigments. Species of the genus Paracoccus from the Rhodobacter group, which are eaten by some crustaceans and contribute to their red colouring, appear to be particularly productive. These micro-organisms play a central role in the production of the industrial product Panaferd, which contains not only natural astaxanthin but also other carotenoids such as adonirubin and canthaxanthin. According to the manufacturer, Panaferd contributes to a more natural diet for salmon because it replicates carotenoid sources that these fish would also consume in the wild.

Despite the same pigment content in the feed, salmon often show differences in the colour of their flesh. The red colour is not only influenced by pigments, but also by a variety of other factors. For example, environmental influences, the activities of the fish, the nutrient composition of the feed, its genetic constitution and more. Not all salmon can process and store the pigment molecules equally well, which means that some animals even develop white or slightly grey flesh. In the wild, one in 20 chinook salmon (also known as king salmon) in the Northwest Pacific has white or white-marbled flesh. This is due to a recessive genetic trait (presumably the beta-carotene oxygenase

1 gene), which plays an important role in the carotenoid metabolism of this type of salmon. In the past, such colour aberrations were usually discarded after the fish were caught, but today white king salmon are considered a special attraction and delicacy.

The flesh of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), which is naturally lighter than that of the Pacific Oncorhynchus species, often shows individual differences in colour. The reasons for this usually remain unknown because the colouration processes are complex. We know little about how external factors and biological mechanisms interact to influence the pigmentation of salmon fillets. Science has difficulty tracking carotenoid metabolism because various non-pigmented metabolites occur

Your one stop supplier for:

New Zealand: Hoki, Hake, SBW, Dory, Ling, Mackerel, Squid, Orange Roughy, Warehou... and many more.

Chile:

Hoki, Hake, SBW, Ling, Warehou... and many more

Argentina: Red Shrimp, Hake, Hoki, Squid, Warehou, Savorin... and many more.

Faroe Islan ds: Mackerel, Herring, Northern Blue Whiting.

USA:

Alaskan Pollack, Cod, Surimi base, Hake, Roe, Yellow Fin Sole... and many more.

NEW: MSC Pink Salmon

in its course. It is undeniable that some salmon are simply better at processing the pigments and developing intensely red flesh. It appears that breeding conditions and stress can affect astaxanthin levels. It is also known that highfat feed generally promotes the red colouration of the fillet (fish with a lower fat content tend to have white flesh). With rapid growth, the colouration is usually weaker. Even within a fillet, noticeable colour differences can be seen. The explanation is often given as discrepancies between the role of astaxanthin in protecting against oxidative stress and its deposition in the muscle cells. Whether this is really true is as difficult to prove as it is to disprove. In aquaculture, salmon are indeed exposed to numerous stress factors such as sorting, handling, transport, high stocking densities, diseases, vaccinations, occasional food deprivation and intraspecific aggression, which lead to acute or chronic stress, which in turn increases the release of hormones such as adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine into the bloodstream and can potentially cause colour changes.

Changes in the feed could also affect pigmentation. Less fish meal and fish oil reduce the salmon’s appetite and promote fat accumulation in the intestine. However, phospholipids are particularly important for the transport of nutrients through the intestine and affect the utilization of pigments. The amount of phospholipids in the feed influenced the salmon’s astaxanthin and fat digestibility. In experiments, salmon feed enriched with phospholipids from soy beans led to redder-coloured fillets. Such studies suggest that intestinal absorption could be a bottleneck in the utilization of astaxanthin, which ultimately determines how

much pigment actually ends up in the salmon muscle meat.

Over the last decade, farmed salmon fillets have tended to become paler, despite more pigments being added to the feed. To clarify the causes and extent of this development, the Norwegian Seafood Research Fund has funded the Knowledge Mapping Pigmentation project. As part of the study, data will be collected through questionnaires, interviews and seminars with salmon farmers and feed manufacturers to provide information on changes in production methods and feed composition. Another focus will be on diseases and increasing stress, especially due to frequent delousing, which have a negative impact on astaxanthin levels. Land-based production in RAS with its usually high stocking densities, the

accumulation of waste products in the water and its constant disinfection will also be examined in the course of the study. These are all exciting scientific questions that also have great practical significance and create added value because fillet pigmentation influences salmon sales.

Pigmentation problems could even increase in the future, because it is fairly certain that climate change with rising temperatures contributes to the increased breakdown of pigments in the fillet in summer. This can lead to the formation of stripes or, in extreme cases, even to a complete loss of pigment in the fillet. In the future, pigmentation and astaxanthin utilization could also become selection criteria in breeding programs. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a fast and reliable screening tool for predicting the expected amounts of fat and pigment in the meat. In addition, some researchers are already

seriously considering specifically switching off those genes in the salmon’s genetic material that may have a negative effect on pigmentation. The biological mechanisms involved in the storage of astaxanthin in muscle cells have not yet been sufficiently explained, but the first ‘candidate genes’ have already been identified. With new, powerful gene editing methods (CRISPR/Cas9), it should not take too long to clarify the role of these genes in the absorption, conversion and storage of astaxanthin in various tissues and organs.

Of course, with all these studies and projects, it is important to keep consumers and their wishes in mind. Perhaps some customer groups will soon prefer fillets that are less coloured but still look natural. Consumer preferences may change faster than salmon change their colour. Manfred Klinkhardt

Visit us at AQUA24 in Copenhagen on August 26-30 at stand 33-35 to see how six EU projects seek to improve European aquaculture.

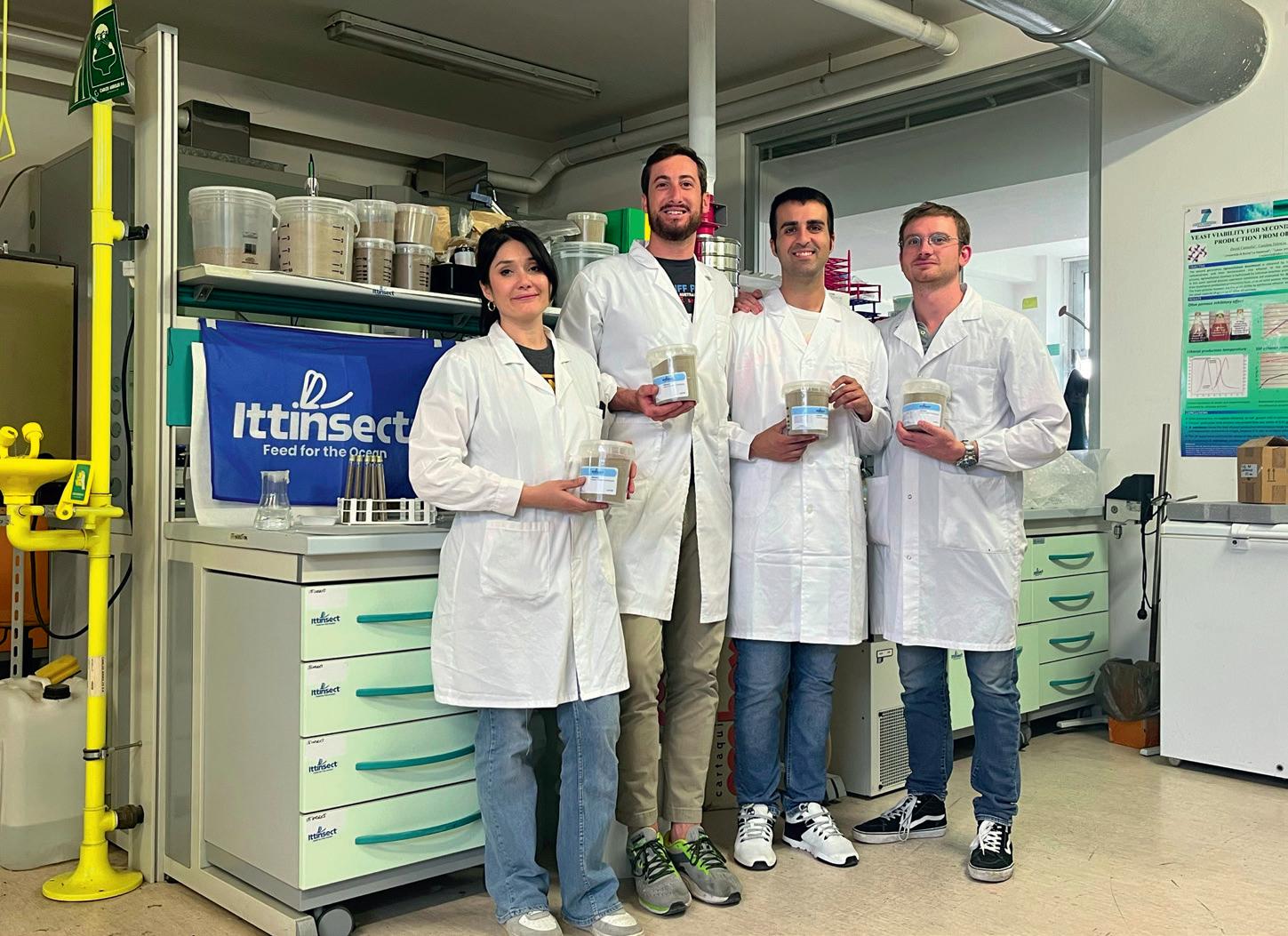

Italian startup deploys biotechnology to create better aquafeeds

Ittinsect, a three-year-old company based in Rome, isolates amino acids from insect meal to create an ingredient for fish feed that improves fish performance.

Farmed finfish can generally either be fed or nonfed and, of the total, the share of non-fed species has shown a declining trend since 2000, according to FAO. Many fed species are carnivorous and are traditionally fed with feeds

based on fishmeal and fish oil that mimic the diet they would obtain in the wild. Fishmeal and fish oil are produced from stocks of small pelagic species and the volumes produced fluctuate in line with catches of those species, however the overall trend

shows a decline in the volume of fish used to produce fishmeal and fish oil. This peaked at 30m tonnes in 1994 and fell to 16m tonnes in 2020, reports FAO. The aquaculture feed industry was the single largest user of fishmeal (86%) and fish oil (73%) in 2020.

Aquaculture farmers are under pressure to use feeds with alternate ingredients both to cut costs, to increase aquaculture’s sustainability, and to avoid accusations of preventing the human consumption of some of these small pelagic species.

Fishmeal and fish oil are increasingly being derived from fish by-products from the processing sector. In 2020 that share amounted to 27% for fishmeal and 48% for fish oil. Rather than being given to fish throughout their growth, feeds using fishmeal and fish oil are increasingly deployed at specific stages of the fish lifecycle such as hatchery, broodstock, or shortly prior to harvesting. Feeds for the growth phase have a smaller and smaller proportion of these two ingredients as they are substituted with plant- or insect-based products. Grower diets for Atlantic salmon or seabass and seabream are often less

than 10% fishmeal and fish oil. Capitalising on the opportunity this development offers, several companies in Europe and other parts of the world are growing insects to produce meal. Ittinsect, an Italian biotech company, uses proteins extracted from insects of different species and from vegetable by-products to produce a protein meal that can substitute fishmeal in fish feed. Alessandro Romano, the CEO, says the process starts with fermentation and the use of enzymes to identify the amino acid needed. This is then extracted and combined with other amino acids to deliver a highly nutritious product. Ittinsect uses the ingredient in its feeds. These are adapted to the needs of the specific farmers who can decide the proportion of the product that should be included

in the feed. Farmers can choose either to replace or supplement the fish meal content of the feed with the protein meal. The product, according to Mr Romano, has a positive impact on fish health, growth rate, and taste of the fish.

The company is currently in the process of expanding the line of feeds it produces for the famers and by the end of the year expects to sell its ingredient off the shelf to salmon feed producers to incorporate in their products. While production amounts to 800 tonnes this year, in 2025 Mr Romano expects to reach 5,000 tonnes. Expansion has been accelerated thanks to public and private investments and he is aware that large volumes bring down the unit costs and make

the company more interesting as a partner for players in the feed business. Production is based in Italy and Spain and is carried out mostly by contract manufacturing to enable large volumes without huge capital investments. Ittinsect has its own laboratories which are responsible for development and validation of the product and which include bioreactors and small extruders for trials. Initially the company sought to consolidate its market in Italy, developing a good customer base and collecting the feedback necessary to further develop and improve the product. Today, three years since it was founded, the target markets have expanded to France and Norway. In the former, the focus is on the feed, while in Norway it is on the ingredient.

Black soldier fly larvae (pictured) and mealworms are among the commonly used insects for meal, but the potential of other species is also being explored.

Interestingly, Mr Romano finds the product is chosen for different attributes in the different countries. For example, in Italy it is the promise of better performance that drives interest, while in France it is the product’s sustainability. The country has made an effort to promote insect protein as a natural protein in fish diets and consumer acceptance is therefore much higher than in Italy, where insect protein is still regarded with some suspicion. In Norway the company contemplates producing locally as that would reduce the environmental impact and would be regarded positively, but the main selling point, he claims, is the higher growth rate, better weight distribution— meaning an improved ratio of fillet weight to belly weight—and lower mortality. These outcomes are due to the processes the raw materials undergo that significantly increase the digestibility of the ingredient Ittinsect manufactures. In addition, the processes

reduce the proportion of antinutritional factors like chitin in the product which lessens the risk of gut inflammation in the fish. By contributing to the overall health of the fish the product enhances the animal’s resilience to factors like stress and disease.

The environmental advantages of the product stem mainly from the use of insect-based raw materials rather than fishmeal and fish oil. By this measure our feeds do significantly better than conventional feeds while also improving fish performance, says Mr Romano, though our carbon footprint is only marginally better. The fish in : fish out (FIFO), a metric showing the volume of wild fish that goes into the production of one kilo of farmed fish, has steadily improved over the years. According to the Marine Ingredients Organisation, a trade body, the FIFO for all finfish species groups except for eels is less than 1. That is, less than a kilo of forage fish is used to produce a kilo of farmed fish. For salmonids the ratio was 0.93 in 2020 (down from 3.03 in 2000) while for eels

it was 1.34. For all fed aquaculture species taken together, the ratio was 0.19 in 2020 (0.47 in 2000). How much of this improvement can be attributed to the substitution of fishmeal and fish oil with insect products is not clear. A study1 in Reviews in Aquaculture that looked at the environmental impact of insect meals in fish feed found that the carbon footprint of insect production was actually greater than that of fishmeal and fish oil, while land use efficiency was about the same. The researchers found that insect production was a relatively recent enterprise and, unlike in the mature marine ingredients industry, the potential

for improvement was vast. They concluded that switching to the industrial-scale farming of insects using energy efficient facilities could reduce the carbon footprint of the activity. Moreover, developing suitable substrates, with low environmental impacts and which improve the nutritional characteristics of the insects, is necessary for insect proteins to become an environmentally viable alternative to marine ingredients.

Ittinsect does not farm the insects themselves. These are now bred all over Europe and are on their way to becoming a commodity, so the company sources the insects from suppliers in five or six European countries. They must have been raised on agricultural waste and have all the necessary health certifications to meet the statutory requirements for their use in feed. This year will see the first French and Norwegian customers and the launch of the first ingredient as an off-the-shelf product. Having successfully formulated and sold feeds based on the ingredient Ittinsect has developed, Mr Romano hopes now to emulate that achievement where the ingredient itself is the product.

Via Giacomo Peroni 386, 00131 Rome Italy

info@ittinsect.com ittinsect.com

CEO: Alessandro Romano

Activity: Bioprocessed ingredients based on insect meal and

agricultural by-products for aquafeeds

Species catered to: Trout, sturgeon, seabass, seabream, salmon

Volumes: 800 tonnes in 2024, 5,000 tonnes in 2025

1 Quang Tran H, Van Doan H, Stejskal V. Environmental consequences of using insect meal as an ingredient in aquafeeds: A systematic view. Rev Aquac. 2021; 14: 237–251. https://doi. org/10.1111/raq.12595

The Horizon Europe project, Verifish, will supply consumers with the tools to make objective decisions about the seafood they buy. The objective is to encourage them to consume sustainably.

In the information age, making informed decisions should be straightforward. Consumers need information about sustainability and nutrient values, as well as provenance, and potential risks and benefits of the products they consume. However, when it comes to seafood consumption, the complexities of health benefits, sustainability, and climate impacts create a daunting landscape for consumers. VeriFish, a Horizon Europe funded project, steps in to address this challenge, aiming to streamline the decision-making process by offering a robust framework of verifiable indicators in Europe. By providing clear, standardised information, VeriFish enables consumers, retailers, producers,

fishers, policymakers, and citizens to make choices that promote sustainable living. VeriFish will also focus on children as they are the consumers of the future, and their choices matter. This article delves into the intricacies of the VeriFish project, exploring its objectives, innovations, and potential impact on the seafood industry and beyond.

Seafood is a vital component of a balanced diet, offering numerous health benefits, including highquality protein, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential vitamins and minerals. Despite its advantages,

seafood is often ignored or incorrectly categorised as meat, leading to a lack of recognition of its lower climate impact compared to other protein sources. This misclassification contributes to lower seafood consumption in Europe compared to meat products. Additionally, locally produced seafood often struggles to compete with imported products because consumers are either unaware of or do not sufficiently value the benefits of local seafood.

The solution to this problem is not to simply convince consumers to purchase more seafood. Indeed, both fishing and aquaculture industries generate issues that complicate consumer

choices. Overfishing, bycatch, habitat destruction, and climate change are just a few of the problems that the fishing sector faces. Overfishing, driven by high demand and inefficient fishing practices, depletes fish stocks and disrupts marine ecosystems. Bycatch further exacerbates biodiversity loss and threatens the stability of marine ecosystems. Habitat destruction, resulting from activities such as bottom trawling and coastal development, undermines the resilience of marine habitats and compromises their ability to support biodiversity. While aquaculture has the potential to relieve pressure on wild fish stocks, it is also not without its drawbacks. Issues such as habitat degradation,

With 60 years of dedication in the aquaculture industry, Aller Aqua continues to deliver feed solutions rooted in long-standing expertise and excellence.

water pollution, disease outbreaks, and the use of antibiotics and other chemicals pose significant environmental and health risks.

Consumers deserve to know the impact of their seafood purchases, but the issues within this industry—notably, the lack of standardised information about its sustainability and environmental impact—continues to hinder consumers from making truly informed decisions. Without clear, harmonised indicators, consumers are left in the dark about the impact of their seafood purchases. Labels and certifications often vary widely in terms of criteria and transparency, leading to confusion and mistrust. This information gap not only affects individual purchasing decisions but also undermines broader efforts to promote sustainable consumption patterns. The absence of standardised metrics complicates the creation and enforcement of regulations by policymakers, and without clear guidelines and incentives, the industry will struggle to transition towards more sustainable production methods. Addressing these challenges requires a coordinated effort from all stakeholders, including governments, industry players, NGOs, and consumers.

The VeriFish project was conceived to tackle these challenges head-on over a two-year period starting in May 2024. Funded by the European Union (EU) and following the objectives of the HORIZON-MISS-2023-OCEAN-01-10

“Choose your fish: a campaign for responsible consumption of products from the sea” call, the project aims to develop a comprehensive framework of verifiable indicators that provide clear, reliable information on the health benefits, climate impacts, and sustainability of various seafood products. These indicators will be based on existing EU global FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data repositories and indicator lists. These will include indicators for environmental sustainability, social sustainability, provenance, processes (including organic production and seasonality), human health, and nutrition. The project will not define new indicators, as it will select existing ones from reliable sources and integrate them in a new and innovative framework. The project is designed to serve consumers, retailers, seafood producers, the HoReCa (hotels, restaurants, and catering) sector, and policymakers alike,

simplifying the complex landscape of seafood consumption. Based on the integrated framework of indicators, the project will develop a prototype of a web-based app, design, develop, and disseminate several types of media products, and develop and publish European Good Practice recommendations. The web-based app and the media products will be promoted through social media channels attractive to targeted groups.

of the project

At the heart of VeriFish is the development of a robust indicator framework. This framework includes a set of verifiable indicators that can be used to make transparent claims about seafood products. These indicators cover a range of aspects, including environmental sustainability, social responsibility, and nutritional value. By standardising these metrics, VeriFish ensures that consumers receive consistent and reliable information, regardless of the source. The framework will be open access and tested via enduser engagement campaigns.

The structure of the VeriFish indicator framework will be closely aligned with the Global Record of Stocks and Fisheries (GRSF) that is based on Ecosystem Approach

to Fisheries (EAF) principles. This database is not only supported by the ongoing Horizon-Blue-Cloud 2026 project, but also is unique because it not only provides a list of sustainability indicators for fisheries, but it also the current state of each indicator. In the case of aquaculture, even though there is no central database like GRSF, there are many other different types compatible with what the project aims to achieve, such as AquaGRIS (FAO) and ISO 12877. In addition to these data sources of environmental sustainability, the indicator framework will contain and link together data sources and indicator lists for social sustainability, provenance, health, and nutrition from different databases, including FishBase, SeaLifeBase, ISO12875, SEAFOODTOMORROW, and FoodEXplorer.

The VeriFish framework will integrate information from different databases and rank them according to the level of reliability. Alongside this ranking, VeriFish will also provide a definition, rationale, method of computation, links to sources, periodicity, (dis)aggregation options, limitations, and comments about the compiled information. The framework will showcase the

most important data about a product using standardised definitions. For many products, indicators can be collected once and used many times.

To avoid skimming 100+ pages of indicators, users and stakeholders will be able to view them in a spider/radar chart that supports connections between ideas, exploration of possible solutions, and visualisation of concepts that would otherwise be difficult to understand. This will allow users to assign a specific scope to an indicator and integrate local, seasonal, or health concerns regarding fisheries and aquaculture sustainability with wider sectoral environmental impact mitigation plans, sustainability of the fisheries, and EU-wide nutritional data.

To fully utilise the indicator framework, VeriFish provides comprehensive guidelines on how to use and visualise these indicators. These guidelines are designed to help retailers and producers effectively communicate the sustainability credentials of their products. Clear visualisation techniques, such as infographics and easy-tounderstand labels, are promoted to ensure that the information is accessible and engaging for all consumers.

The VeriFish project has been designed with high impact in mind, both the expected direct impact outlined in the topic and the wider societal impact following EU policies and UN Sustainable Development Goals. The project pathway towards impact will be through outreach campaigns, factsheets, magazine articles, recipes, games, videos, and SoMe content for different types of seafood, targeting different consumer groups, cultures, and languages.

One of the most exciting aspects of the VeriFish project is the development of a prototype mobilefriendly application. This app is designed to provide consumers with easy access to the indicator framework. Users can search for specific seafood products to see detailed factsheets, including the verifiable indicators, health benefits, and sustainability credentials. The app also offers recommendations on how to make informed and responsible seafood choices based on individual preferences and dietary needs.

The user interface will be convenient and will reproduce the VeriFish indicator framework in an easy-to-navigate format. The app

will provide information describing the status of stocks, activities, food composition information, biological characteristics of species and environmental information, guiding users towards informed choices. Because VeriFish will be available in this portable, accessible form, sustainability can be more easily considered by consumers when they make choices about their seafood.

In addition to the app, VeriFish is creating a series of media products promoting informed consumption. These products include videos, social media content, and educational materials that highlight the importance of sustainable seafood practices. By leveraging multiple media channels, VeriFish aims to reach a broad audience and foster a community of informed and engaged consumers.

One of the key deliverables of the VeriFish project is the development of a European Good Practice (EGP) recommendation. This recommendation will be published as a CEN (French abbreviation for European Committee for Standardization) Workshop Agreement (CWA), providing a standardised approach for communicating about sustainable

seafood. The CWA will offer practical guidelines on how to effectively organise and run campaigns that promote sustainable seafood consumption. By providing a harmonised framework, the CWA aims to improve the clarity and consistency of sustainability messages across Europe.

The CWA will play a critical role in enhancing the communication of sustainability credentials to different end-user groups. For consumers, it will provide clear and trustworthy information that helps them make informed choices. For retailers and producers, it will offer a standardised method for showcasing the sustainability of their products, helping to build consumer trust and loyalty. For policymakers, the CWA will serve as a valuable tool for designing and implementing effective regulations and initiatives.

Feedback from stakeholders will shape Community of Practice (CoP)

Central to the success of VeriFish is the establishment of a Community of Practice (CoP). This CoP will be established for stakeholders committed to

promoting sustainable seafood, which will have a significant impact both during and after the project. The CoP will engage and attract experts, stakeholders, and multipliers to provide information about the VeriFish indicator framework, the media products, and the web app and to engage them in the final project conference in February-March 2025. By fostering collaboration and knowledgesharing, the CoP ensures that the best practices and insights are integrated into the VeriFish framework. The community will offer invaluable opportunities for knowledge sharing, collaboration, and skill development among members by fostering a sense of belonging and shared purpose, as well as enhancing learning and problem-solving within specific domains and professions. The VeriFish CoP will engage actors in the relevant fish supply chains, other experts, and multipliers by providing independent, validated information about fish in the European market. At the same time, the CoP will also contribute to the VeriFish indicator framework and other tools.

Engaging a diverse range of stakeholders is crucial for the VeriFish project. By involving different perspectives and expertise, VeriFish ensures that its solutions are comprehensive and effective. Regular workshops, webinars, and consultations will be held to gather feedback and refine the project’s outputs. This collaborative approach not only enhances the quality of the indicator framework but also builds a sense of ownership and commitment among stakeholders.

The project will offer expert advice and promote good practices on how to collect, collate, aggregate, and present data on indicators. However, for VeriFish to be an effective project, it will follow a validation process with stakeholders and actors along seafood supply chains. This will allow for gathering feedback, ensuring alignment with objectives, and validating fitness for purpose. The goal of this validation phase, which will be conducted more than once to ensure ongoing alignment with stakeholders needs and expectations, is to demonstrate that VeriFish will provide an overview of a seafood product that is accessible in terms of the GRSF (Global Record of Stocks and Fisheries data protocol).

An essential component of VeriFish’s stakeholder engagement is the inclusion of children. Educating children through social media, influencers, and by engaging in “understanding games” about sustainable seafood is crucial. By cultivating today’s youth, VeriFish aims to shape the minds of the future and ensure sustainable production and consumption behaviours. Children, as the next generation of consumers, play a vital role in the long-term success of sustainability initiatives. Educating them about the importance of sustainable seafood practices helps to instil values and habits that will contribute to a more sustainable future.

The mobile app and all media products of VeriFish will be designed with many types of consumers in mind, including children. These tools will provide interactive and fun ways for

The VeriFish consortium comprises ten European partners (eight beneficiaries and two affiliated entities) from nine countries bringing complementary skills and expertise. The project is led by the Italian company Trust-IT that will also contribute to outreach and awareness campaigns. The development of the indicator framework will be led by EUROFIR (Belgium) in collaboration with FORTH (Foundation for Research and Technology Hellas) (Greece), PREMOTEC (Switzerland), and with the support of FishBase and SeaLifeBase (affiliated entities). Eurofish International Organisation (Denmark) will oversee the development of guidelines and will lead communication, outreach, and dissemination campaigns. COMMpla (Italy) and PREMOTEC-PL (Poland) will oversee the development of the web app. NOFIMA (Norway) will be the main partner on the development of the CWA, and CLUPEA (Netherlands) will manage the policy liaison and sustainability of the project. A new partner will come soon in the future to help with outreach and awareness campaigns.

children to learn about the benefits of sustainable seafood, making complex information more accessible and understandable. By involving children, VeriFish not only broadens its reach but also ensures that the message of sustainability is passed on to future generations, fostering a culture of informed and responsible consumption.

Project outputs could enable consumers to boost demand for sustainable seafood

While the initial focus of VeriFish is on developing the indicator framework and related tools, the project has a long-term vision that extends beyond these immediate goals. Future developments may include expanding the indicator framework to cover a wider range of seafood products and other food categories. Additionally, VeriFish aims to continue building and strengthening the CoP that will live on after the project, ensuring that the project remains responsive to emerging challenges and opportunities.

The success of VeriFish depends on both the efforts of the project team and stakeholders, and on the active participation of consumers. By embracing the tools and information provided by VeriFish, consumers can play a crucial role in driving demand for sustainable seafood. The project encourages readers to download the app, engage with the media products, and become part of the movement towards a more sustainable future.