The Albanian fisheries and aquaculture sector is multifaceted. Capture fishing is practiced in the Adriatic Sea, along the coast, in inland waters, and coastal lagoons. Fish farmers cultivate fish and shellfish in the sea and grow fish in freshwater in dam lakes, raceways, and net cages. Fishers use different gears includ ing trawls, seines, dredges, and gillnets to target a variety of species, and their vessels are classified into large- and small scale with the former measuring more than 12 m in length. Catches have remained largely stable over the last five years, but the industry is seeing a growing number of non-native species and has to contend with growing volumes of plastic litter in the sea. Production from aquaculture has more than dou bled over the last five years with the bulk of the volume coming from seabass, seabream, and rainbow trout farming while carp species grown in polyculture make up the balance. However, the sector faces challeng es such as a shortage of labour, the lack of allocated zones, and the need to adapt to higher temperatures. Addressing these will allow development to continue as it has in the past. Read more from page 16

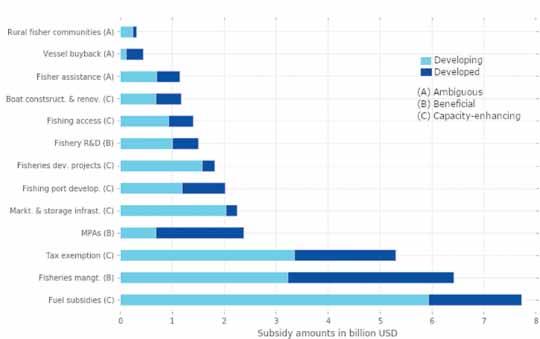

Support to the fisheries sector from governments takes a variety of forms—fuel subsidies, vessel decom missioning, research, monitoring and control, stock management, infrastructure, and direct contributions to fisher’s incomes. The purpose of the support is typically to improve fishers’ welfare, maintain employ ment in the sector, or enhance the sustainability of the activity. However, many forms of subsidy, such as for fuel or vessel renewal (input subsidies), also contribute to an increase in fishing capacity and to overfishing. This means that while fishers profit from subsidies the rest of the population pays the price of depleted stocks and declining biodiversity in the oceans. Globally, subsidies are estimated to cost between USD14 and 54bn a year with one 2019 study from Canada calculating them at USD35bn. And there are vast disparities in the way they are distributed both within and between countries with wealthy countries and large vessels responsible for a disproportionate share. For these reasons and because taming subsidies is an objective un der one of the UN’s sustainable development goals subsidies need to be eliminated. The agreement reached recently at the WTO is a step in this direction. Read Dr Manfred Klinkhardt’s article from page 34

Vegan and vegetarian seafood products are a growing sector of the food industry. The Global Food Institute (GFI) estimates that the vegan meat market is worth almost 1.4 billion dollars with fish and seafood making up 1 of the vegan meat alternatives market. This sector is growing, and it is estimated that the trade in vegan fish products will grow by 28 annually until 2031. This is because despite a consumer’s decision to be vegan or vegetarian, many consumers still want a product that tastes like fish or meat. The production of fake fish requires vast expertise in the production process, so the product replicates fish texture, flavour, microbiology, and nutritional profile. For this reason, fish alternatives have many ingredients such as thickening agents, acid ity regulators, aromas, and preservatives intended to make them taste like fish. However, natural fish are high in bioavailable protein, essential amino acids, and omega-3 fatty acids. Alternative fish products lack these nu tritional benefits and adding these nutrients is expensive and energy intensive. Current complaints about fish alternatives include that the products aren’t organic, they smell is too fishy, and they taste too much like chicken or vegetables. Vegan fish alternatives have a market of willing buyers, however, production challenges have yet to be solved. Read more from page 38

While the war in Ukraine is being felt around the world because of its impact on cereal and oilseed exports from Uksraine which in turn are contributing to global inflation, the effect on the Ukrainian aquaculture industry has been largely confined to the country itself. However, for those that are affected the situation is no less serious. The fall in production of farmed and wild fish threatens the consumption of fish products throughout Ukraine. Processing facilities have either been destroyed or are working only part time due to the difficulties in getting raw material both domestically sourced and imported. A study conducted by the Methodological and Technological Center for Aquaculture, a Ukrainian consultancy based in Kiev, has tried to analyse the war’s impact by gathering information using questionnaires addressed to the indus try, reports Yuri Sharylo, the director of the center. However, in areas that are occupied or where military operations are being conducted it has not been possible to survey the industry and information will only be forthcoming when hostilities end. In the longer perspective the development of the aquaculture sector has been prioritised by the government. Several initiatives have been taken that should revitalise the sec tor after the war. Like the rest of the economy fish farming is suffering, but hopefully it is only temporary. Read more on page 46

The Salmon Eye, a futuristic construction that floats on the sea in the Hardangerfjord in Norway was launched early September at a hybrid event featuring viewers from around the world and an audience at the site itself. Eide Fjordbruk, the company behind the Salmon Eye, is a farmed salmon producer that is committed to the sustainability of its activities. The construction itself is expected to contribute to a more sustainable seafood production that does not burden the environment but in fact helps to solve the challenges thrown up by climate change. At the same time it is intended to cement Norway’s position as a leading seafood

nation with a farmed fish industry that will play a role in food security for the world’s growing population. Technological development and innovative solutions are the way to meet these objectives and the Salmon Eye, itself a product of technology and vision, has been created to change the way seafood is produced. As climate and environmental regulations become more stringent in the coming years the pressure to produce more sustainably will only increase. Eide Fjordbruk is already looking at new solutions for climate neutral production including for collecting and reusing sludge from sea cages. Initiatives like the Salmon Eye promote

The Salmon Eye was created by the company Eide Fjordbruk to change how seafood is produced and to contribute to sustainable food production that meets the UN’s objectives.

an open and transparent dialogue between the stakeholders in the industry where the problems and the potential of aquaculture

can be freely discussed with the ultimate goal of strengthening the Norwegian maritime food industry.

The Lexicon of Sustainability and the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI), with technical support from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) launched the Greener Blue initiative as a part of the FAO International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture. The Greener Blue initiative aims to highlight contributions from artisanal and small-scale fishermen to sustainable food systems and the eradication of poverty. The Greener Blue initiative sought people willing to participate in the project’s “Storytelling Lab” which provided participants with the opportunity to build skills and receive mentorship while acquiring a database of stories from artisanal fishermen. The project gave participants a GoPro camera to keep in return for the fishermen telling their stories. The objective is to celebrate the importance of fishermen and

Greener blue is a storytelling initiative that is part of the FAO International Year of Artisanal Fisheries.

farmers in addressing climate change and protecting ecosystems. Farmers and fishermen have

immense firsthand knowledge, and the initiative plans to build a knowledge sharing platform,

Seafood MAP, to provide a place for stakeholders to learn, connect, and develop solutions.

Researchers from the University of Stirling have identified an exciting potential for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) using sea cucumbers and farmed fish. The research stems from the European Union’s Horizon 2020-funded project “Tools for Assessment and Planning of Aquaculture Sustainability (TAPAS)” and was carried out with the AquaBiotech Group and the University of Palermo. The study found that sea cucumbers flourish by feeding on organic waste from commercial fish farms. The sea

cucumbers consume the fish waste which can effectively mitigate the environmental impacts of organic waste accumulation from fish farming. Using stable isotopes and fatty acid analysis the researchers found that fish waste was the dominant food source for the sea cucumbers contributing to their health and growth. Sea cucumber is a delicacy in parts of Asia. It has nutritional properties and is currently being researched for potential medicinal and other health benefits. The demand for sea cucumber is very high and it

New research suggests that sea cucumbers could be used in multi-tropic aquaculture to mitigate accumulation of organic waste from fish farms.

is being over-fished in regions of the world. Sea cucumber can sell for €30/kg dried and €120/kg as processed product in the

market. The IMTA approach could be a profitable and more environmentally beneficial way of producing fish.

Stakeholders concerned with fishing pressures on the English Channel saw a minor victory when the European Parliament voted to ban demersal seine fishing in parts of the channel. The demersal seine fishing technique, also referred to as fly shooting, has received criticism recently for

putting too much pressure on the channel fishery and having significant effects on small scale fishermen. It is estimated that there are around 75 demersal fishing vessels operating in the channel which is significantly higher than the fishery can support. The EU parliament’s vote on the ban of

The use of plankton in salmon feed is an innovative step in ensuring sustainable salmon aquaculture and the most efficient aquaculture production. Since plankton is a natural prey for salmon, the use of it in aquaculture can help optimize the salmon’s nutrition. For this reason, the Norwegian salmon producer Andfjord has entered into an agreement with Skretting and Zooca to develop a fish food tailored for their on-land flow through salmon production.

Skretting is a feed producer and Zooca will source the plankton. Skretting has developed a fish feed using algae oil instead of marine fish oil and Calanus finmarchicus zooplankton. This feed can contribute to optimal water quality, fish welfare, and fish growth. Additionally, Calanus finmarchicus is a sustainable source to base the feed on because it has an exceptionally high production capacity of 300 million tonnes annually. It is one of the

demersal fishing now makes it possible for the European Commission and EU member states to vote on whether the fishing technique should be banned in French territorial waters. This is part of larger concerns between both the UK and the EU about sustainability of the Channel’s fishing stocks.

The issue stems as well from the origin of the fishing vessels, which is often not French, and therefore removes economic opportunity from French territorial waters and French coastal communities. The push for increased regulation on these waters should help protect small scale French fishermen.

Innovating with plankton as a salmon feed ingredient hopes to improve the quality, taste, and efficiency of aquaculture salmon.

most numerous animal species available and Zooca extraction of Calanus is only 0.0005 of total

annual volume. Therefore, its use in feed will not put pressure on the Calanus populations.

The International Cold Water Prawn Forum will hold its biennial conference on 17 November 2022 in Tromsø, Norway. The event will provide participants with the status of the cold water prawn sector in terms of resources, production, trade, and

markets. The range of speakers will offer a wide international perspective on developments in the industry enumerating the latest challenges and opportunities. Like all such events the key objectives are to inform and to enable participants to network with their

colleagues from countries across the globe. The event was last held face to face in 2019 so for many attendees it will be an opportunity to catch up with their peers after a gap that has been longer than the usual two years.

The cold water prawn (Pandalus borealis) industry will meet for the biennial meeting of the International Cold Water Prawn Forum on 17 November 2022 in Tromsø, Norway.

The cold water prawn (Pandalus borealis) is the most commercially important crustacean in the North Atlantic with total annual landings of 250,000 to 400,000 tonnes, according to the Norwegian institute of Marine Research. P. borealis is distributed in the North Sea, along the Norwegian coast, and in the Barents Sea, as well as around

Iceland, along Greenland and the Canadian coast, among other areas. Greenland, Canada, and Norway dominate landings of this species. It grows to a maximum size of 20 g and 16 cm and is found at depths of 70 m and below. The cold water prawn is caught and often cooked on board. In supermarkets they are available frozen, but also fresh or cooked and peeled. They have a high nutritional value and are the source of a valuable oil and an enzyme used in laboratories.

For more information about the conference visit www.icpwf.com where it is also possible to register.

Researchers from the Centre for Genetic Resources in the Netherlands are to monitor the genetic diversity of wild and cultured aquatic species and then cryopreserve (freeze in nitrogen) samples of the species.

Since aquaculture stocks typically originate from wild populations there is a varied genetic diversity for potential initial stocks. Monitoring differences between wild and aquaculture populations is important for the sustainable use of aquatic resources. This project aims to understanding the genetic makeup of these farmed and wild fish stocks. The research is part of the Netherlands’ commitment to the FAO global action

plan for conservation and sustainable use of aquatic genetic resources. The cryopreservation of the material is intended to help ensure the long-term genetic diversity of the selected species. The project will monitor Crassostrea gigas (Pacific oyster), Ostrea edulis (flat oyster), Mytilus edulis (mussel), Anguilla anguilla (European eel), Scopthalmus maximus ( Psetta maxima ) (turbot), Sander lucioperca (pike perch), Saccharina latissima (sugar kelp), Ulva spp. (sea lettuce), Laminaria digitata (oarweed), and Undaria pinnatifida (wakame, an exotic species, which has permanently established itself in the Netherlands). When applicable, the

Turbot is one of the species that will be genetically studied and cryopreserved in this Dutch study.

project hopes to cooperate with commercial aquaculture companies, however, the monitoring

and sampling will differ depending on the species and access to samples.

Lake Peipus is located on the border between Estonia and Russia and is the site for a vendace fishery in both countries. Vendace is a small freshwater whitefish.

The Estonian Russian fisheries commission has agreed on a split quota for vendace with quotas for 2022 at 50 tons per country.

The vendace season begins on July 1 and by July 10 the Estonian Minister of Rural Affairs halted Estonia vendace fishing as 90 of the quota had already been

caught. Estonian fishermen have expressed concern that Russian fishermen may not be fairly following their allocated quotas. They have identified that while their season is quicky over the Russian fishermen are continuing to catch vendace. The fishermen point to customs data which reveals Vendace being sold from Russia to Estonia. They also pointed to the decrease in the quota from 80 tons last year to 50 tons this year in response to the

Estonian fishermen fear that vendace is being overfished in Lake Peipus.

depleted fish stocks. The stocks will continue to be depleted if the exploitation of the quotas is not managed. However, given

political conflicts and difficulties in proving these accusations, this will be a difficult issue that no one will want to address.

One of the keys to transparency in the global fisheries supply chain is data transparency. Norway has agreed to share their Vessel Monitoring System with the non-profit, Global Fishing Watch. Global Fishing Watch uses satellite tracking data to map commercial fishing vessels and fishing activity. The agreement with Norway will add the location of around 600 vessels to the Global Fishing Watch database. Accurate fishing vessel tracking is a necessary component in mitigating and minimizing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. Norway’s agreement to share their vessel monitoring data with

GFW is a big step in documenting the environmental footprint of the fishing industry and offers the opportunity to establish worldwide data to understand the full scale of impact of the fishing industry. In addition to the agreement, Norway has expanded their vessel monitoring systems to include all commercial fishing vessels and has increased the frequency that vessels must report their location. The agreement has raised concerns as to why the EU has yet to cooperate and share their fishery data to the same extent. EU spokespeople have responded by identifying EU privacy regulations make contributing

the Global Fishing Watch difficult and highlighted the EU’s existing electronic logbook processes for all EU vessels. Regardless, this

agreement reminds all fishery professionals that reporting, and transparency can always be improved and increased.

The Spanish Fisheries Confederation (CEPESCA) has released its report on the Spanish fish sector for the 2020-2021 period. Total production value was 2,043 million euros which was a 10 growth from 2019. The report identified that Spain accounts for 28 of the total value of EU fishing. The Spanish fishing industry generated 31,093 direct jobs and 150,000 indirect jobs in 2020. There was an increase in imports and exports from 2020-2021. This growth reveals the resilience of the Spanish fishing sector in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and maintaining successful health and safety measures on fishing vessels. The report recognizes Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a new crisis for the industry to manage and identifies increased challenges resulting from new EU environmental policies, regulations, and objectives. These new policies include a potential reform of the Common Fisheries Policies and the Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Fisheries Research. The closure of

87 vulnerable marine zones from deep sea fishing will also have an unknown socio-economic

impact on the Spanish fishing industry. The report identified the importance of strong industry

leadership as increases in prices of fishing oil and diesel will make profitability more difficult.

Sea lice are one of the primary challenges in salmon aquaculture. Sea lice put fish health, the economic viability of the product, and wild salmon populations at risk. Monitoring sea lice in aquaculture facilities is a necessary but expensive measure for aquaculture companies. Researchers at NINA, the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, and NTNU, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, have developed an innovative new lice trap system for monitoring sea lice. Norwegian aquaculture operates on a “traffic light” system where the infection pressure from sea

lice on salmonids is monitored to determine if salmon production can be increased or needs to be decreased. The current system relies on significant statistical modeling as well as manual counts. This can be an expensive and time intensive processes. The new sea lice trap technology filters seawater but traps plankton which can be analysed in the lab using DNA based methods to calculate the number of sea lice larvae. In the current early development stages, results from this technology are being compared with results from current monitoring to calibrate the models

Sea lice are a major challenge for the salmon farming industry. A new lice trap technology will help monitor them.

and ensure accuracy. In the early stages of research and development, this method presents a

cost effective and easily scalable solution to monitoring sea lice levels.

A project consortium of six partners from five countries has developed an innovative device for safety training for crews on fishing vessels. The technology is a virtual reality simulator that educates fishermen on hazards and safety procedures, exposes them to hazardous scenarios, and walks them through the safety procedures and how to execute them. This is an important technology for the fishing industry because most fatal accidents that occur on fishing vessels are the result of a lack of knowledge of emergency procedure and how to

execute appropriate emergency procedure. Often, there is a general lack of compliance by crewmembers on periodic training and safety exercise requirements. This VR technology hopes to combat this issue to emphasise the importance of safety in fisheries. The technology was introduced by the European Parliament at an event hosted by MEP Gabriel Mato and EU fisheries experts. The event was attended by fisheries stakeholders, including representatives of EU Institutions, industry and civil society that saw the need for this innovative tool.

Octopus populations in Croatia have been affected by overfishing and hunting by recreational and professional fishermen. Octopus is primarily used for food in Croatia. As octopus stocks have decreased in recent years, they continue to be overfished as their perceived rarity has increased the product value. Researchers at the University of Split are now exploring the viability and potential for octopus restocking. This research has involved the release of hundreds of thousands of octopus larvae into the sea. The researchers will then track the

integration of the octopus into the ecosystem and the wild population. The hope is to develop optimal conditions for octopuses’ survival to help the populations rebound. Currently, only 1 of octopus survive the larval stage and increasing this percentage is imperative for successful restoration. To monitor the success of the released larvae, the scientists are manually tracking the octopus larvae using genetic samples, and they have asked fishermen to contribute to data collection by providing samples for DNA analysis when they catch an octopus.

The Hungarian fishing industry is poised to benefit from the EU’s recent protection of the Balaton fish brand in restaurants. The Balaton fish brand labels indigenous Hungarian fish that have been produced in Lake Balaton, a large freshwater lake in western Hungary. The protection of the Balaton fish label will help ensure

high quality, carefully controlled, and locally produced fish. This will benefit fishermen, restore the status of fish from Lake Balaton as a high-quality product, build awareness of indigenous and nonindigenous species among local people and tourists, and give gastronomic recognition to fish from Lake Balaton. This is an exciting

Hungary: Balaton fish brand will be available in Hungarian restaurants after receiving EU protection

milestone for a region that has historically struggled with overfishing and low fish stocks. It is estimated

that 800,000 people work in the Hungarian fishing industry. Lake Balaton produces 500-600 tonnes

of wild, and 150-200 tonnes of farmed fish annually. If all goes well with the Balaton brand

implementation in restaurants, it will hopefully be integrated into the retail sector soon.

The EU funded project EcoScope aims to identify the key challenges facing the fishing industry and develop electronic and digital tools for mitigating the challenges. The goal is to help implement ecosystem-based fisheries management that can fine tune the accuracy of marine policy scenarios, spatial planning systems, and other models. This hopefully will help mitigate some of the human impacts and ecosystem degradation in European seas. The project began with a survey of fisheries industry

stakeholders to understand their needs, industry challenges, and the potential future obstacles. The survey revealed that 72.2 of respondents believe that global warming is a major threat to fisheries. Secondly, by-catch, increased protection areas, and fisheries restricted areas are the next biggest concern with 50 of respondents identifying each of those factors as a concern. Other notable risks were biodiversity reduction and marine and coastal area user conflicts, and species distribution.

The French and Spanish tropical tuna fleets are currently being undermined by EU margin of tolerance control rules. Stakeholders argue that the regulations that specify the degree of variability between catch estimates and actual catch landing that make it impossible for the tropical tuna fleets to be economically profitable. The regulation identifies that there must be a difference of no more than 10 per species between catch estimates on board and the landed catches. The issue with this regulation is that when the temperatures on the boat are high (above 30 degrees Celsius) the fishermen only have a few minutes to sort and freeze the catch before it becomes unsafe for human consumption. Tuna fisheries organizations argue that differentiating between different species in this short time frame is very difficult and leads to incorrect catch estimates. Consequently, the fleets receive heavy sanctions. Fleets from other countries face

less stringent regulation and therefore the Spanish and French fleets face disproportionate economic challenges. The tuna organizations request that the regulation

be modified so the 10 rule applies to the entire fleet rather than each species. Currently, the sanctions are so detrimental to the fleets than an independent economic analysis

found that if nothing changes by 2026, the ship owners will need to shut down. This would represent a loss of 1,600 French jobs and 2,500 Spanish jobs.

The EU Cohesion policy which allocates funds to support the social, economic, territorial cohesion, competitiveness, green and digital transition for EU countries has allocated 31.5 billion euros to Romania. Of this sum, 162.5 million will be from the European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund to be invested in sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, conservation of aquatic biological resources in the Black Sea, fisheries control, sustainable aquaculture, processing, diversity in local fisheries and aquaculture communities, and in supporting modernisation of fishing infrastructure in the Black Sea. Commissioner for the

Environment, Oceans, and Fisheries, Virginijus Sinkevicius, stated that the Partnership Agreement will allow Romania to build innovative, low-carbon and sustainable fisheries, aquaculture and processing sectors while also reinforcing the economic and social vitality of coastal communities. It will also support the resilience of sectors faced with exceptional events that lead to serious disruption of markets.” This partnership should be valuable for the Romanian fisheries sector’s continued growth and will help mitigate economic challenges resulting from Covid-19, high fuel prices, supply chain disruptions, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In a year that has been rocked by inflation, salmon consumers are finally starting to see some price relief. After consistently high prices for the first half of 2022, salmon prices are beginning to fall. Salmon prices peaked in May of 2022 with a maximum price of EUR 10.57 per kg of fresh salmon. The prices stayed high for a large portion of June, however, the NASDAQ salmon index 12-week average indicates that there has been a 12 decline in prices with the price currently

around EUR8.82 per kg of fresh salmon. Experts from FishPool, a marketplace for salmon financial contracts, predict that the price will fall to 8.69 EUR. This fall in prices would be in line with normal salmon price trends. Demand tends to decrease during the summer holiday while people travel while supply continuously increases. Annual price lows are typically seen in the second half of the year as the supply is consistently higher, but demand either decreases or is stagnant.

Salmon prices see their first decline in 2022.

At the plenary on the EU’s biodiversity protection ambitions, the Croatian MEP Valter Flego requested that the EU pay more attention to the protection of the Adriatic Sea. He said that while soil, forests, and air protection remain at the forefront of EU biodiversity protection

ambitions, the sea seems overlooked. He emphasised that for people living in the Mediterranean and relying on the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas for food, recreation, tourism, and other uses, the sea was just as necessary to protect and maintain as the land or air. He

called for further discussion of the preservation of the sea at the COP 15 summit (the UN Biodiversity Conference). The management and protection of the Adriatic Sea is an important issue because the detrimental effects of climate change are rapidly beginning to

be seen. The sea is changing, and the water temperature is increasing which helps invasive species establish and kills native species. This puts a significant number of economic sources such as fisheries and tourism at risk for Croatia and other Mediterranean countries.

Fishmeal and fish oil (marine ingredients) are derived primarily from small pelagics including Peruvian anchoveta, menhaden, blue whiting, capelin, sardines, and herring although production from by-products is increasing and will continue to grow.

Global production of fishmeal and fish oil depends on catches of these species which vary with the state of the resource. Stock abundance is influenced by natural phenomena such as the El Niño— Southern Oscillation and tends to fluctuate. According to the 2022 edition of the FAO’s State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA), volumes of fish reduced to fishmeal and fish oil peaked in 1994 at 30m tonnes, declined to 14m tonnes in 2004, increased again to 20m tonnes in 2018, before falling back to 16m tonnes in 2020. Fishmeal and in particular fish oil are also derived from by-products from fish processing, a share that is increasing. Other sources of these two ingredients that are being explored include Antarctic krill and the copepod, Calanus finmarchicus, fish silage, a protein rich hydrolysate, and insect meals

The main use of fishmeal and fish oil is in aquafeeds for the aquaculture industry. About 86 of fishmeal and 73 of fish oil was designated for this purpose in 2020. However, as production from aquaculture has increased while fishmeal and fish oil output has remained within certain limits, the share of these ingredients

in aquafeed has been steadily declining. They are increasingly being used for specific stages of production (hatchery, broodstock, finishing diets) rather than in feeds for on-growing diets. As an example, the proportion of these ingredients in on-growing diets for salmon is now often less than 10, according to the FAO. To discuss these and other developments in the marine ingredients industry, Seafood Source, a part of Diversified Communications, organised a webinar on 31 August that was addressed by executives from the Marine

Ingredients Organisation (IFFO), an international trade organisation representing the global marine ingredients industry. The event was moderated by Cliff White from Seafood Source.

Marine ingredients are the most nutritious and most easily digestible components in aquafeeds. They are also the source of the healthful omega-3 fatty acids which benefit both the growing fish as well as the humans who consume the fish. The ingredients also have a multiplier effect with 1 kg of the raw material used

to produce fishmeal and fish oil resulting in 5 kg of farmed fish, according to Petter Johannessen, IFFO Director-General. Many of these fisheries are certified as sustainable. Of the average global production of marine ingredients in the years 2017-21, 49 was certified as sustainable up from 21 in the 2010-14 period. In addition to the omega-3 fatty acids, marine ingredients are also a source of other nutrients such as essential amino acids. Research shows that palatability of salmon aquafeeds increases with the addition of marine ingredients, while protein

digestibility for anchoveta meal is very high and shows little variability, in comparison with alternatives such as soy or corn gluten, reported Brett Glencross, IFFO Technical Director.

Explaining that sustainability was fundamental for the marine ingredients industry, Dr Glencross said that the maximum sustainable yield for a stock was the most common way of looking at sustainability. The MSY is the highest possible annual catch that can be sustained over time keeping the biomass at a level that produces the maximum growth of that biomass. Small pelagic fisheries are among the best managed in the world with their biomass being sustained at expected levels, he pointed out.

Among the reasons is the reduction in fishing pressure over the last couple of decades which has also contributed to a largely stable supply of marine ingredients over this period. The environmental footprint of small pelagic fisheries in terms of their greenhouse gas emissions per unit of landings is the lowest of all species groups (demersal, large pelagics, crustaceans, cephalopods etc.).

Emissions are most closely associated with fuel use during fishing operations. Similarly, the carbon footprint of marine ingredients compares very favourably with those of alternate ingredients.

In terms of their use of biotic resources, however, marine ingredients tend to consume more than other ingredients, though their use of abiotic resources is lower. This balance illustrated Dr Glencross’ contention that the perfect ingredient did not exist; there will always be a trade-off. He also referred to the fact that while

From bulk ingredients in fish feed, fishmeal and fish oil have gradually become strategic ingredients used in specific stages of aquaculture production. In on-growing diets for salmon, for example, the proportion of marine ingredients today is often less than 10%.

most fish caught and farmed is for human consumption less than half is actually eaten. The other half can be recovered and returned to the food chain by using it to produce marine ingredients. Moreover, some species, such as Atlantic mackerel, previously used for reduction to fishmeal and fish oil are now being used almost entirely for human consumption. But these too generate by-products that can be used to produce marine ingredients.

Enrico Bachis, IFFO Market Research Director, confirmed much of what had been said by the previous two speakers but added more detail. The contribution from by-products is increasing, particularly in the case of fish oil, where by-products now amount to a third of the raw material. In the case of fishmeal this fraction is about 15. These byproducts come from both capture fisheries and the aquaculture industry, and their contribution is likely to increase in the future as

the production from aquaculture grows and techniques evolve that allow more of this material to be recycled. The biggest suppliers of marine ingredients in geographical terms are Latin America, Asia, and Europe with Latin America supplying between a quarter and a fifth of the total. In Asia and Europe, the raw material is a mix of wild catches and by-products from aquaculture, while in Latin America the raw material is mainly from wild fisheries. The data for fish oil includes the menhaden fishery in the US which accounts for 12 of the raw material thanks to the species’ high content of fish oil. Average fishmeal and fish oil production over the last nine years was about 5m tonnes and 1.2m tonnes respectively per annum. This stable supply can be attributed to the generally well managed fisheries on which this supply is based. Fluctuations from year to year have been due to natural events such as El Niño, said Dr Bachis, rather than overfishing.

The structure of demand for fishmeal and fish oil has changed over the decades with aquafeeds replacing poultry, pig, and pet feeds as the biggest consumer. The

fraction of fish oil for direct human consumption in the form of products for human health has also increased and in 2020 accounted for some 12 of the total. However, as production from aquaculture has grown and marine ingredients production has remained stable, fishmeal and fish oil have evolved from bulk ingredients in aquafeeds to strategic ones. In closing Dr Bachis showed that crustaceans are the biggest users of fishmeal followed by freshwater fish, marine fish and salmonids. The sheer volume of crustaceans (11.2m tonnes) and freshwater fish (48m tonnes) produced around the globe are responsible for their position ahead of salmonids (4m tonnes) in usage of fishmeal. On the other hand, salmonids are the biggest consumers of fish oil followed by crustaceans and other marine fish. More generally, the crustacean and specifically the shrimp sector is a growing and not just in Asia but also in Central and Latin America. Since production of marine ingredients is stable, farmed species showing strong growth will tend to push out others in the quest for these ingredients. The competition for marine ingredients looks set to increase.

From its initial application in 2009 to the Intergovernmental Conference on accession negotiations earlier this year, Albania has come a long way in its endeavours to join the EU. Frida Krifca, Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, discusses here issues facing Albania’s fisheries and aquaculture sector including the task of aligning national legislation with the EU acquis.

Albania is implementing the provisions of the Stabilisation and Association Agreement as a step towards EU membership. In its status report for 2021 the European Commission points to the lack of sufficient staff in inspection and control. What are the reasons for this and has the situation been remedied? What parts of the CFP remain to be adopted into Albanian legislation?

Albania has taken measures to increase the capacities of the fisheries inspectorate. New staff have been recruited, increasing the number of fishing inspectors and guaranteeing 24/7 control at the four fisheries ports. Also, in the framework of the IPA 2016 Project “Fishing Blue - Support for the fisheries sector in Albania” which is financed by the EU, training sessions were conducted for staff of the fisheries inspectorate with the aim of increasing the capacities of this inspectorate. Likewise, at sea and on land control manuals for the fisheries inspectorate have been prepared and distributed, and all fisheries legislation has been published for fishing operators and the fisheries inspectorate. Within the framework of this project, 11 fisheries inspectors have been trained and certified as national observers for all activities related to tuna fishing, according to ICCAT requirements. In September 2022, the fisheries inspectorate will be

equipped with 2 control vessels, donated from the EU, which will provide a great help in increasing the control of fishing activity

Albania has opened negotiations with the EU for membership. This is a long process which will require a great deal of work for the fisheries administration and the transformation of the sector to align with EU standards. Albanian legislation is generally in line with the EU acquis, but a lot of work is required for the whole sector to be made compliant with the Common Fisheries Policy. Recently, the new fishing strategy was approved, within the framework of the Strategy for Agriculture, Rural Development and Fishing 2021-2027, with the support of GIZ, which prepares the fisheries sector and brings it closer to the EU.

VMS is used to monitor the activities of the Albanian fishing fleet while fisheries inspectors control the smaller vessels. This year (2022) electronic logbooks are scheduled to be introduced to increase the transparency of fishing activities. While these measures benefit managers and policy makers, what has been the response of the fishermen?

The ERS system, the electronic logbook, is planned to be implemented in 2024. During 2022, the legal foundation will be prepared, in

accordance with EU legislation, and during 2023, TORs for its establishment will be prepared and the tendering procedures will be carried out. The implementation of this system is expected to increase the transparency of fishing activities. There will be a long process of consultations with interest groups, but the process of joining the EU requires an increase in fishing standards as well. The interest groups are aware of the necessity of its implementation and the process is advancing as MARD (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) has planned.

Albania is a signatory to the 2018 ministerial declaration

on a regional plan of action for small scale fisheries (SSF) in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. The plan envisages several actions1 in relation to data collection, scientific research, SSF management, climate change adaptation, sustainability etc. over the 10 years to 2028. Which actions are being given priority by the ministry? How does the ministry encourage the organisation of the SSF?

Small Scale Fisheries are an important component of Albanian 1 https://www.fao.org/3/cb7838en/ cb7838en.pdf

fisheries and as such receive special attention from MARD. The ministry improved the fishing law by approximating a part of Regulation (EU) no. 1379/2013, of the European Parliament and of the Council, dated December 11, 2013, “On the common organization of markets for fishery and aquaculture products”. Measures have been taken to improve the technical rules concerning the sector‘s development, and a support package is being prepared to regularise informal operations in the sector.

What has been the impact of the corona virus on the Albanian fisheries and aquaculture sector? What measures were implemented by the government to assist the sector? Would you say that activity has returned to its pre-pandemic level?

The impact of the coronavirus was primarily felt in the decrease in demand as a result of the closure of part of the country‘s markets that consume fish products. The processing industry also saw a reduction in activity despite the growing demand for processed products both on the domestic and international markets. However, despite this, there was an increase in exports of Albanian products in 2020 and 2021 although not at the level of previous years.

Another issue is the impact of the war in Ukraine, which has brought about an increase in the price of fuel for fishing. The first six months of 2022 was a difficult period for marine fisheries, which saw a reduction in fishing activity. To assist fishers with this situation, MARD decided to support the sector by subsidising fishing fuel with 40 lek/litre. This support will be implemented in the second half of 2022 and will compensate some of the additional costs arising from the price increase.

What is the status of the fish auction at Shengjin? Has it contributed to greater transparency in pricing, the removal of middlemen, and better prices for the fishers? Does it facilitate the distribution and sale of fish and seafood products? The new wholesale market at Vlora is scheduled to open this year. What has been the response from fishers and seafood traders to these new structures?

Wholesale fish markets are a priority for MARD. The Shengjin wholesale fish market is in the final stages of being transferred to Lezha Municipality as duties and responsibilities are defined and assigned. The wholesale fish market in Vlora is completed and the fisheries management organization (FMO) in Vlora has applied to manage it. MARD is in dialogue with the FMO to determine the conditions, duties, and responsibilities, related to the transfer of this structure.

Producer organisations (POs) are an integral feature of the Common Market Organisation one of the pillars of the Common Fisheries Policy. POs organise fishers and farmers to jointly pursue objectives listed in the CMO regulation including sustainability, food security, and growth and employment. Do you see this as a useful instrument for the Albanian fisheries and aquaculture sector? Is the legal framework for the creation of POs in place?

As mentioned above, the amendments to law no. 64/2012 “On fisheries” as well as the changes in the law no. 103/2016 “On Aquaculture” as a partial approximation of Regulation (EU) no. 1379/2013, of the European Parliament and of the Council, dated December 11, 2013, “On

the common organization of markets for fishery and aquaculture products” establishes the basic rules for the creation and recognition of Producer Organizations, as an important instrument for the regulation of the sector. Also, the conditions that these organizations must fulfil to be recognized by MARD have been defined and approved. Minister‘s Order no. 357, dated 29.7.2022 “On the adoption of the regulation on the determination of additional conditions for the recognition of production organizations” has been approved.

Fisheries management organisations have been established to manage freshwater resources in several Albanian lakes. How do you assess their usefulness and reliability as partners of the administration in questions of fisheries management. Has the delegation of responsibility to the FMOs resulted in improved stock status, less illegal fishing, and stable catches?

Fisheries management organisations in Albania were created as an important management instrument where interest groups played the main role. FMOs extend to inland and marine waters. MARD has given the management of the fishing port of Durres to FMO-Durres and is in the process of transferring the wholesale fish market of Vlora to FMO-Vlora. FMOs contribute to the management of the sector through co-management, where the ministry delegates powers related to the management of the fishing activity. Regardless of whether the fishing law provides for forms of organization such as FMOs or Producer Organizations, we are of the opinion that FMOs will gradually transform into OPs covering the entire production

chain, from the factory to the final consumer.

A World Bank report2 suggests that the yield from capture fisheries is unlikely to increase very much over time and the future for Albanian seafood production lies in the aquaculture sector. Do you agree with this assessment? What measures are being implemented to boost aquaculture production in Albania? Have allocated zones for aquaculture (AZA) been identified and legally implemented?

We agree with the assessment of the World Bank. The increase in demand for fish products, not only in Albania but also at the global level, will be fulfilled through the increase in production from aquaculture. Global assessments predict that demand for fish products will double by 2030. Today, in the Mediterranean the situation of fish stocks is not good with about 85 of the commercial species overfished. Even at the global level, capture fishing industries are in decline, compared to aquaculture, which continues to show substantial growth. MARD has prepared a study for Allocated Zones for Aquaculture (AZA) in the sea and so far one of them has been approved, and others are in the process of negotiation with the Ministry of Tourism and Environment. In addition, this year MARD is funding a study on AZA in internal waters which will be carried out by the Agricultural University of Tirana with the technical assistance of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean.

2 https://openknowledge. worldbank.org/bitstream/ handle/10986/34892/ Realizing-theBlue-Economy-Potential-in-Albania. pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The fisheries and aquaculture sector in Albania

Global warming and climate change are increasingly affecting fisheries and

and while they may bring some advantages, they also create conditions to which farmers and fishers must adapt.

Capture fisheries in Albania from the sea, along the coast, from inland waters, and coastal lagoons have remained largely stable over the five years to 2021, according to data from Institute of Statistics. Marine catches include some 45 species of fish, shellfish, and cephalopods and averaged about 6,000 tonnes over the five years to 2021.

About a third of the catches can be attributed to just two species, European anchovy and deepwater rose shrimp. Catches of hake and pilchard are also significant while volumes of the remaining forty species are small. Catches along the coastline and in the coastal lagoons also contribute modestly to the Albanian capture fisheries. Inland waters yielded some 3,000 tonnes of fish per year on average over the same period, of which the proportion of carps (common, crucian, silver, bighead etc.) was close to 55. Total yields showed a slight increasing trend over the period. Roaches, mullets, and perch were the other inland water species caught in significant volumes.

The Albanian fleet comprises trawlers, seiners, dredgers, gillnetters, and multipurpose

of which the gillnetters and trawlers dominate the fleet in terms of numbers. In contrast to most EU fleets the number of vessels has been increasing in Albania. Between 2017 and 2021 the fleet increased by over a third to 750 vessels thanks mainly to a 45 increase in the number of gillnetters to 525 vessels. The trawler fleet also increased from 157 to just under 200 vessels. The large-scale fleet (LSF) comprising vessels above 12 m fishes outside the 3 nautical mile limit targeting hake, shrimp, and red mullet. The demersal and pelagic fisheries for sardines and anchovy are managed with temporal restrictions. Two years ago, large vessels were equipped with vessel monitoring system (VMS) equipment so they can be monitored by fisheries inspectors. The individual species with the highest catches in 2021 were anchovy and deep-water rose shrimp

Fish

which accounted for about a fifth and 16 of the total respectively.

Anchovy catches fluctuated violently in the five years to 2021 from 1,500 tonnes in 2018 to 260 tonnes in 2020. Other important species in terms of catch weight were hake and pilchards. The total catch in 2021 was 6,300 tonnes. Fishers have also noticed the presence of species, both native and alien, not normally found in the areas being fished. In a survey conducted among small scale and recreational fishers by staff at the department of aquaculture and fisheries under the FAO Adriamed Project, respondents mentioned 75 species. Their presence could be explained by global warming and the data from the survey might help local communities better understand, manage, and adapt to the ongoing biotic transformations driven by climate change, says Dr Jerina Kolitari from the Aquaculture and Fishery Laboratory in Durrës. Climate change

is not the only issue that fishers and fisheries managers have to contend with. Another is marine pollution which takes the form, among others, of microplastics and ghost gear. Through the laboratory in Durrës, Albania has participated in projects, such as DeFishGear, that aim to quantify and reduce the amount of marine litter in the sea and on beaches.

The small-scale fleet (SSF) fishes within the 3 nautical mile limit and can be controlled when the fishers land their catch as well as at sea where the inspectors check the net dimensions, dimensions of the caught fish, the licenses, and the distance from the shore.

Administrative measures taken against vessels found in breach of the regulations has created an awareness of the need to maintain the permitted depth and the

correct distance from the coast and have prevented some illegal fishing, according to Dr Kolitari.

These measures are intended also to address the paucity of data on the SSF. In an article1 in the Croatian Journal of Fisheries, Prof. Rigers Bakiu, Head of the Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, Agricultural University of Tirana, and his co-authors show that the SSF in the Mediterranean uses many different gears, are active in different seasons and on different fishing grounds and target a variety of species. The Albanian SSF is responsible for about 5 of the total fisheries catch though over 60 of the number of vessels and 28 of the total employment in the fisheries sector. In their study which centred around vessels operating in southern Albania, the scientists established that essentially two types of gear, nets and longlines, were deployed by the fishers. With the former, fishers target hake, mullet, cuttlefish, and sole,

while with the latter fishers target either the large pelagics like bluefin tuna and swordfish or seabreams, porgies, and groupers. The objective of the study was to generate data on the SSF, which are otherwise data deficient, and to use this information to create a clearer picture of the status of marine fisheries and thereby allow more reliable stock assessments. The authors also recommended “robust monitoring mechanisms and multiple control protocols” to reduce data uncertainty.

Production from aquaculture has doubled from 4,000 tonnes in 2017 to 8,100 tonnes in 2021. The main species farmed in Albania are the marine species, seabass and seabream, as well as the freshwater species, rainbow trout. In addition, several carp species are farmed in polyculture with other freshwater species. Natural and artificial lakes, and reservoirs are used to cultivate

horse

these fish and farmers use intensive, semi-intensive, and extensive fish farming techniques.

Finally, there is a cultivation of mussels at a couple of sites, one in the north of the country in the bay of Shengjin and the other in the Butrinti lagoon in the south.

The main growth in the aquaculture sector comes from the production of seabass and seabream and of rainbow trout where companies from Italy and Turkey have invested in facilities in Albania.

Reflecting the growth in production is a steep rise in the number of people employed in the sector which has gone from 2,800 in 2012-13 to 9,600 in 2021, says Frida Krifca, Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development. Now, however, in common with the sector in other parts of Europe, it is becoming more difficult to fill positions and farmers are starting to grumble about the lack of

qualified labour. The lack of interest in fish farming could perhaps be attributed to the work itself which is physically demanding and the salaries that go with it.

Young people would rather be working at a desk in a comfortable environment rather than be mucking around on a fish farm.

The shortfall in labour is one of the challenges facing the sector.

Another is the implementation of allocated zones for aquaculture (AZA). According to the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), AZA are areas earmarked for the development of aquaculture, an activity which, within the zone, has priority over other uses. The identification and implementation of AZA

is a priority for the sustainable development of aquaculture in the Mediterranean at a time when pressure from different interests on coastal zones are proving a bottleneck for the development of the aquaculture sector. AZA are expected to facilitate the integration of aquaculture into plans for coastal development and lead to improved coordination between the various authorities and other stakeholders in the area. In Albania the study to identify the AZA has been completed, says Arian Palluqi, Director, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and sea cages have to be moved 300 m away from the coast. The study was carried out by an Italian consultancy working in close collaboration with the ministry. Areas have been identified in Saranda and in Shengjin and for the cultivation of fish and of shellfish. The government has to approve the map of the different AZA which take into account the interests of the environment and the tourism sector. Although fish farming and tourism tend to compete for the same space, they also have common interests, Ms Krifca points out. For farmers tourists are a ready market for the fish they produce, while for tourists fish farms are not only a source of healthful and very fresh protein, but could also be

an attraction to visit and learn about fish farming. Mr Palluqi is hopeful that the approval will be forthcoming later this year or early in 2023.

A long-term challenge to the aquaculture industry is the impact of global warming which is affecting both freshwater and marine production. Warming water, extreme weather events, a shortage of precipitation, the increased presence of invasive species, and algal blooms can be attributed to global warming. Other impacts include a reduction in the oxygen content of the water, and an increase in acidity as the water absorbs more carbon dioxide due to the increase in atmospheric concentrations of the gas. The FAO has identified the Mediterranean as a region where droughts are likely to be longer and more frequent, a development which is likely to affect the aquaculture sector. And while oceans are warming around the world, it is in the northern hemisphere that this is most obvious, reports the organisation. In Albania, trout farmers experience that as the water warms up the fish move deeper down the water column and if the surface gets too warm they are reluctant to even come

up to feed. For mussel farmers too increasing water temperatures can have an impact on the production as the Mediterranean mussel can tolerate temperatures of up to about 23 degrees centigrade. If it gets any warmer they will start to perish, says Tonin Suli who farms mussels in the Shengjin bay. For fish grown at sites where the water is deep the animals can avoid the higher temperatures at the surface by migrating to cooler depths. Mussels too could be suspended from ropes that extend deeper into the water column. While these adaptations may be feasible at some sites it may not be an option in shallower waters or where higher temperatures have caused water levels to drop. Farmer using

such sites will therefore have to devise other solutions.

Warming does not affect all species equally. Prof. Bakiu says that European seabass is more affected than gilthead seabream, the two main marine species farmed in Albania. Farmers are increasingly producing seabream exclusively as it can better tolerate the increase in temperature and the heatwaves that cause oxygen levels in the water to fall. Moreover, seabass seems to be more vulnerable to the diseases related to the changing temperature, he

notes. In a paper2 in the Albanian Journal of Agricultural Science from 2021 Prof. Bakiu and a colleague looked at the impact of climate change on the abundance and catch of seabass and seabream in Albanian water and stated that temperature and salinity have significant effects on growth and feed intake of juvenile seabass. The species showed a preference for lower temperatures in comparison to seabream which thrived at higher temperatures. This suggests that seabream could become more abundant than seabass in Albanian waters as the temperature increases.

Invasive species that establish themselves in response to warming can also be a threat to the aquaculture industry. Prof. Bakiu mentions the pumpkinseed fish (Lepomis gibbosus) that has invaded the Dumrea lakes near Elbasan and feeds on the larvae and fingerlings of the carp species, common carp, bighead carp, grass carp etc., that farmers are cultivating in the lakes. Sudden extreme heat can also lead to a rapid drop in the oxygen content of the water which can cause mass fish deaths. Fish farmers are trying to adapt by reducing the biomass they hold to facilitate the management of the production, says Prof. Bakiu. He, together with colleagues from the department of aquaculture and fisheries at the university, is conducting a survey of freshwater fish farmers to understand their situation and the threats and challenges they face. The survey will also identify and help to regularise

operators who may be behind on their paperwork. This will allow the government to channel aid to the farmers with which they can invest in aerators or oxygen as a way of adapting to climate change.

Climate change also has an impact on the fishing sector. For fishers too one of the threats from warming water comes from the migration of non-native species to Albanian waters in the Ionian Sea. Prof. Bakiu reported the presence of a lionfish (Pterois miles) in June last year. Recorded for the first time in Albanian waters the species is native to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. It has colonised Greek waters where it is reputed to be a threat to commercially important or critically endangered species, according to a paper in a book3 Lionfish Invasion and its Management in the Mediterranean Sea published by the Turkish Marine Research Foundation. According to Prof. Bakiu it feeds on larvae as well as juveniles of species native to Albanian waters and although it is a valuable species for fishers and charismatic for divers, it needs to be treated with care as its spines are poisonous. He expects it to establish a population in Albanian waters in the next 2-3 years as it moves from the south of the country to the north.

The challenges presented by climate change are only likely to increase in the future. The way towards safeguarding fisheries and increasing resilience is by the effective and sustainable management of resources. Albania has embarked on this path and is making progress towards these objectives.

Kilic’s Albanian subsidiary draws on the knowledge, training, and experience of the parent company in Turkey to farm rainbow trout in a dam lake.

Freshwater fish production in Albania comprises both capture fisheries from lakes and rivers as well as fish farmed in earthen ponds, raceways, and dam lakes. While there is significant overlap between the species from capture and those from aquaculture, one variety stands apart. This is rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) which is farmed in raceways and more recently also in cages in dam lakes.

Probably the biggest producer of rainbow trout in Albania is the company Kilic Albania Aquaculture which was established in 2015. Kilic, a Turkish company, is a giant in the Turkish fish farming industry producing seabass, seabream, trout, meagre, and tuna. The company is fully integrated with hatcheries, nurseries, on-growing, processing, packaging, and distribution. It also manufactures its own feed. Kilic Albania Aquaculture is a fully owned subsidiary of the Turkish company and Saimir Todi, its chief of financial and administrative affairs, an Albanian, speaks fluent Turkish (and English).

The company has a hatchery where the larvae are produced. The trout eggs are imported from Poland, Denmark, Italy, or from Turkey and are placed in

incubators in the hatchery. Each month we need to buy 1 to 1.5m eggs, says Mr Todi to be able to harvest the quantities of marketsized fish that we need through the year. This number also takes into account a mortality rate of about 20 through the production cycle. The main suppliers are Poland and Turkey but irrespective of where the eggs come from, they are certified disease free and all female. If sourced in Turkey the eggs are flown from Adana to Tirana via Istanbul and are then transported by truck to the hatchery in Shkodra. Polystyrene boxes in which the temperature is kept at a constant level of about 5 degrees during the journey are used to store the eggs. Once they arrive at the hatchery they are removed from the boxes and adapted to the temperature of

the water in the hatchery, which is some 7 or 8 degrees. Moving directly from one to the other without adaptation would give the eggs an unnecessary shock.

The hatchery is supplied with water from a spring located 100 m away and which delivers a steady volume of water at a constant 12-13 degrees throughout the year.

The combination of water from a spring, the use of disease-free eggs, and the lack of other trout farms in the area means that the threat of disease is fairly remote.

The water temperature is a fraction higher than the 10-12 degrees that is considered the ideal temperature for a hatchery but is perfectly adequate for the purpose.

Once adapted the eggs are placed in the incubators where they typically hatch after a week. However,

the larvae continue in the incubators for another week before they are moved to large rectangular tanks where they spend the next one month before being transferred to the nursery section. The entire production process is carefully planned so that each stage of the production (incubator, larval tanks, post-larval tanks, nursery, grow-out) is completed in time for the next batch, a cycle which continues all year long, says Ali Gungorer, the hatchery manager. Altogether the time taken from the arrival of the eggs to the production of market sized fish of 300-350 g is 7-8 months. In the post-larval tanks the fish grow another month before being moved to the nursery for two months and thence to the cage farm when they weigh about 3 g. Irrespective of the source of the

eggs the quality of the fish is the same. As Mr Todi explains, if a difference was noted then the company would stop buying eggs from that supplier. The company also maintains a few broodstock fish from which is produced a small number of eggs. But we cannot do everything by ourselves, says Mr Todi, and expect to be very good at each activity. We have chosen to specialise in the production of fish rather than eggs. Besides, the eggs from Turkey come from the Kilic trout hatchery in Kahramanmara , where Kilic Turkey has its trout production.

The young fish are fed with different starter feeds depending on their size. Most of the feed comes from the Kilic feed production in Turkey, but the starter feeds are bought in Germany from a reputed supplier. Turkish foreign direct investment in Albania was the sixth largest in 2021 according to a paper in the European Journal of Business and Management Research1. For the parent company in Turkey the decision to invest in

Albania was influenced partly by the country’s proximity to the EU market and partly by the advantages gained from the lower cost of labour. The value of the investment by the parent company was EUR67m in total. The entire production from the trout farm is exported— the main destination is Poland with some fish also going to Romania. The product is exported fresh and frozen with most of the fresh fish going to Romania, and most of the frozen to Poland. The fish is processed at a facility in Durres with whom the farm has a contract. The fish is transferred to the processing plant where it is cleaned, gutted, and frozen when the order is for frozen fish or packaged in polystyrene boxes on ice when the demand is for the fresh product. For the time being the company has no plans to establish its own processing facility, says Mr Todi, as the system of contract processing works smoothly. But if the production volume increases, then we will consider setting up our own facility, he adds.

The dam lake in which the fish are on-grown is the lowest of three dam lakes in a row and Kilic Albania is the sole producer in that lake. The lake was created in

the 60s under the former regime and is reputed to have submerged several villages, the remains of which can be discerned at the bottom of the lake. The grow-out site is located some 14 km from the hatchery and holds 80 cages each with a diameter of 20 m and a depth of 10 m. According to MrTodi, this is the only farm of its kind in Albania; the other trout production facilities grow their fish in raceways or ponds. There is however a major challenge for the sector in Albania and this is the imposition of an 8.4 levy on the fish when it enters the EU. This obviously makes it very difficult for producers over here to make the margins necessary to invest in the business, Mr Todi states. Another factor that affects production is the fluctuating temperature of the water which can probably be attributed to global warming. There are sudden and sharp increases and decreases in water temperature and Caner Tasel, the farm manager, tries to compensate by keeping the cages full when the water temperature is appropriate and by

keeping fewer and fewer fish in the cages in summer, as the water gets hotter. Thus, from winter to summer the volume of fish in the cage falls from 20 tonnes to 10 tonnes. These adjustments are made without interrupting the production cycle, which must be maintained throughout the year as it determines the supply to the clients. When a cage is ready to be harvested it is towed slowly to the landing stage, where the farm’s vessels are docked, and anchored there. The cage is harvested at night when it is a more comfortable temperature for workers and fish alike and because the fish need to arrive early in the morning at the processing factory in Durres which is two and a half hours away by road.

The Albanian operation is closely monitored from Turkey. The farm

1 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24018/ ejbmr.2022.7.4.1542

The eggs are acclimatised to the water temperature in the hatchery and placed in incubators where they stay for a couple of weeks.

is managed using special software that monitors all the parameters and generates reports, says Mr Tasel. Managers at the Turkey office can also log on to the system and see the status of the farm for themselves. Moreover, the general director for trout farming in Kilic Turkey spends a week each month in Albania making sure that everything is running smoothly. Saimir Todi himself spends 1-2 days a week at the farm in Shkodra and the rest of the time at the office in Tirana. The facility in Albania is responsible purely for production, processing, and packaging; all the sales and marketing for the fish is done by the office in Turkey, which is responsible for all the

customer contact and follow up. The model whereby responsibility is divided between the two entities

in Albania and in Turkey has been shown to work and is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Rruga Haxhi Hysen Dalliu Pallat. Alva Const. Shk. Sek. A Kati. 2, Ap. 4 Tirana Albania

Financial and Administrative Affairs Chief: Saimir Todi +355 69 8722885 saimirtodi@kilicdeniz.com.tr

Hatchery manager: Ali Gungorer Farm manager: Caner Tasel

Volume: 1,500 t per year

Product: Rainbow trout, 300-350 g

Product form: fresh and frozen Markets: EU (primarily Poland and Romania), small quantities to Serbia and Macedonia

Employees: 40 people of which the engineers and divers are from Turkey

Project knits Western Balkan countries closer to each other and to the EU

A project funded by the EU combines the objectives of improving higher education and promoting collaboration between countries to manage non-native species.

The project “Educational Capacity Strengthening for Risk Management of Nonnative Aquatic Species in the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro)—RiskMan” is an ERASMUS+ KA2 Capacity Building in Higher Education joint project, selected within the 2020— EAC/ A02/2019 call, and runs between November 2020 and November 2022. The project is coordinated by Mu la Sıtkı Koçman University, Turkey (http://www.riskman.mu.edu.tr/en/). Besides partner countries from the Western Balkans, the project consortium includes the programme

countries: Croatia, Greece, Italy, and North Macedonia.

Educational institutions cooperate with fisheries and aquaculture workers in fight against NNS

The project aims to promote the education of stakeholders, modernise higher education (HE), and stimulate research and cooperation in the risk management of non-native species (NNS). The project has the following specific objectives: (i) to harmonise the HE system on management of aquatic NNS in the Western Balkan partner

Representatives from the RiskMan project consortium at one of the stops on the Balkan tour. The project intends to strengthen educational capacity in the field of risk management of non-native species.

countries with the international directives given by FAO and IUCN and with the strategies of European Policy Cooperation; (ii) to support the partner countries in addressing the challenges that face their HE institutions and systems concerning the management of NNS, including risk identification, stakeholder participation, planning, and governance of aquaculture facilities and related fishery industries; (iii) to promote communication and awareness of stakeholders (students, workers in aquaculture and tourism sectors, and fishers) about the threat that NNS pose to biodiversity; (iv) to promote voluntary convergence with EU developments in HE and fisheries industry and contribute to cooperation among the consortium partners on the management of NNS; (v) to develop a risk management model for aquatic NNS in the Western Balkans; and (vi) to produce a policy framework for creating new occupations through the proposal of a new position “Risk Manager”.

To reach these objectives and prevent further introduction and spread of NNS in the partner countries, HE institutions and workers from the private sector related to fishery and aquatic ecosystem conservation were involved in the project’s activities.

Stakeholder involvement in creating a common language and providing the necessary structure for every stakeholder to work in the same direction are essential components of this project. Implementing new measures to manage aquatic NNS effectively requires strengthening the partners’ capacities. The added value of this project is the development of a protocol to explore the adaptation processes of socio-ecological systems in contrasting geographical settings, rivers, lakes, and coastal areas.

21 to 28 August 2022. The objectives of the tour were to draft the strategic implementation of the NNS courses in the partner countries, strengthen the established cooperation with stakeholders, and exchange experiences between the partner countries. The first stop on the RiskMan Balkan tour was in the ancient city of Kotor, organised by the Institute of Marine Biology, University of Montenegro. Strategies to introduce the new HE courses and curricula related to NNS in aquatic ecosystems were discussed. Several meetings were organised with local stakeholders, represented by marine aquaculture farmers (mussel and fish farms) and a seafood distribution centre.

equipment that would improve the didactics and provide particular skills for future professionals studying at AUT. The last stop was in Ohrid city, situated on the Ohrid lake, one of the richest European ecosystems in endemic species. Several meetings regarding protected areas and their management were organised by the Hydrological Institute Ohrid and the National Park Gali ica. The Gulf of Bones was chosen as a site for the meetings with stakeholders and dissemination activities. RiskMan partners presented the NNS and invasive species in Ohrid lake and the risks and impacts they could bring.

In the framework of this project, a Balkan tour was organised from

In Tirana, the Agricultural University of Tirana (AUT) and the Albanian Centre for Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development (ACEPSD) hosted the second part of the tour, where future plans for collaboration and joint projects, not only related to NNS, were discussed. As in Kotor, the tour participants had a chance to see the newly obtained

Mussel company owner looks forward to being able to export to the EU

In addition, the RiskMan Balkan tour has spawned a network of lifelong colleagues that will ensure the sustainability of the RiskMan project and form the basis for new initiatives in the future.

Prof. Rigers Bakiu, Head of the Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, Agricultural University of Tirana

Mussels from the Shengjin bay in Albania are grown on ropes for about 12 months before they are harvested and sold on the domestic market. One company, Lissus Adria, dominates the production which is marketed fresh in nets.

The aquaculture sector in Albania includes cultivation in the sea as well as in freshwater. Seabass and seabream are the main finfish species grown in marine water, while rainbow trout dominates the production in freshwater. In

addition, a few companies are producing mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) in the Butrinti lagoon in the south of the country while another, Lissus Adria, is farming them on lines in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Shengjin, a city in the north.

According to Instat, the national statistical institute, mussel production in Albania has fluctuated significantly over the five years

to 2021 peaking at 1,100 tonnes in 2018 and falling back to 600 tonnes in 2021. Tonin Suli, a director and shareholder in Lissus Adria, is responsible for the mussel production. The bivalves are native to the area and are grown on ropes suspended from lines as

Roadshow to different countries strengthens links between partners

Tonin Suli, the director of Lissus Adria, a company that farms Mediterranean mussels on lines in the Shengjin bay.

is typical on the other side of the Adriatic, in Italy. The company has licensed an area of 76 ha for its mussel cultivating activities and is currently the only mussel farming company in the bay.

The mussels are collected and sold exclusively on the domestic market as their export to the EU is banned. Mussels can harbour toxins which they filter from the water in which they grow. These can become concentrated in the flesh of the mussel and pose a risk to consumer health. The level of the toxins is influenced

by several factors including the time of the year and therefore must be monitored continuously.