The Human History of the Shawsheen River

Elaine Clements, Executive Director with the help of Martha Tubinis, Director of Programs and Jim Batchelder, Board of Directors Andover Center for History and Culture

Part 1: Deep History through 1646

Part 2: 1646 through 1700

Part 3: 1700s

Part 4: 1800s

Part 5: 1900s

Part 6: 2000s

The

1/12/2023 1 | Page

Human History of the Shawsheen River,

PART 1: Deep history of the area, pre-1646

Note: Historian Christoph Strobel uses the term “deep history” to describe the time prior to 1490 and European contact rather than using “pre-history.” 1

Archaeologists identify the Indigenous people of the Late Pleistocene era (10,000 and earlier) as “Paleo Indians” who had “sustainable, complex, sophisticated lifeways” that included forest management and agriculture. 2

Archaeological evidence for the Archaic period (8,000-1,000 BCE) that followed indicates the Indigenous people regularly revisited sites during specific times and seasons. Evidence that exists around ponds and lakes indicates seasonal use. By 1400, Indigenous people farmed, foraged, and hunted throughout New England. 3

The Woodland period (1,000-1500 BCE) ended in 1490 with the arrival of Europeans and diseases that caused devasting epidemics that killed between 50% and 90% of the Native population. During the Late Woodland period (900-1650 CE) inland Indigenous communities were predominantly agricultural along with foraging, hunting, and fishing. They lived a semi-sedentary life, moving seasonally and when farm fields were exhausted. 4

2 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

1 Strobel, 11

2 IBID, 13-14

3 IBID, 26-27

4 IBID, 29-30

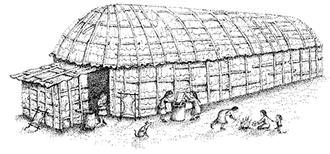

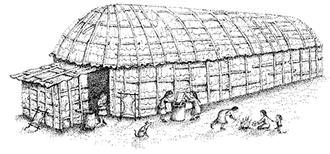

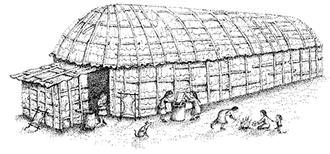

“A Pawtucket Village on the Merrimack River, 500 Years Ago,” diorama built by Guernsey-Pitman Studios of Cambridge, Mass., 1939.

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

“There was an abundance of communities that existed throughout the long pre-colonial history, and that could be found all over the river valleys in many places. In fact, the location of many Indigenous settlements were right in the same places and many New England towns and the now post-industrial cities such as Manchester (New Hampshire) and Lowell (Massachusetts).” 5

The Shattuck farm site on the Merrimack River is a good example. Indigenous residences along other rivers and tributaries were likely similar to the Shattuck farm site. 6

Scant archaeological evidence remains of Indigenous people’s lives from the Late Pleistocene era through the Late Woodlands era (and European contact) along the Shawsheen River as it flows through Andover.

There is a high degree of probability that Indigenous people settled in areas along the Shawsheen River that provided them with needed resources: access to water for sustenance, fishing, and travel, land for agriculture and residences, and woodlands for gathering and hunting. These are the same areas that would later be settled by English colonists.

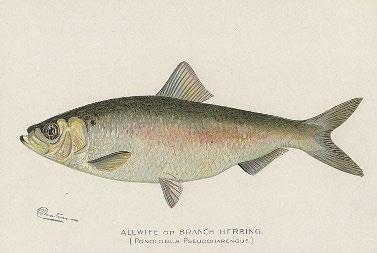

Through court documents, we have a small glimpse into where Indigenous people might have settled. The 1646 attestation of the sale of Andover described “the Indian called Roger & his company” who “may have liberty to take alewives from the Cochichawick River (Shawsheen River), for their own eating” also “the said Roger is still to enjoy four acres of ground where he now plants.”

Attestation:

At a General Court, at Boston 6th of the 3rd m, 1646 Cutshamache, sagamore of the Massachusets, came into the Court, and acknowledged that for the sum of 6 pounds & a coat, which he had already received, he had sold to Mr. John Woodbridge, in behalf of the inhabitants of Cochichawick, now called Andover, all his right, interest, and privilege in the land six miles southward from the town, two miles eastward to Rowley bounds, be the same more or less, northward to Merrimack River, provided that the Indian called Roger & his company may have liberty to take alewifes in Cochichawick River, for their own eating; but if they either spoil or steal any corn or other fruit, to any considerable value, of the inhabitants there, this liberty of taking fish shall forever cease; and the said Roger is still to enjoy four acres of ground where now he plants. This purchase the Court allows of, and have granted the said land to belong to the said plantation forever, to be ordered and disposed of by them, reserving liberty to the Court to lay two miles square of their southerly bounds to any town or village that hereafter may be erected thereabouts, if so they see cause.

3 | Page

5 IBID, 13-14

6 IBID, 13-14

It’s likely that “Roger & his company,” who lived in what they called Cochichawicke, were a Pawtucket band organized as part of the Pennacook Confederacy under the leadership of the Pennacook-Abenaki sachem, Passaconaway.

Lacking archaeological evidence of this settlement, we can surmise that Roger and a small group of people, perhaps his family, lived on four acres along the river near the mouth of what later became known as “Rogers Brook.”

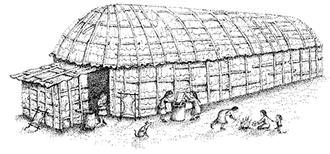

The homes the group occupied would have been a type of dwelling that is variously referred to as lodges, wigwams, wetus, and long houses. These dwellings were round, oval, or conical. The support structure was made of wooden poles that were driven into the ground and bent to form the rounded walls and roof. The dwellings were covered with birch bark. 7

7 cowasuck.org/lifestyle/shelter

8 IBID

4 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Detail from 1692 map showing Roger’s Brook

8

Illustration of a long house

A dwelling area would have been cleared for the construction of residences. Land for agriculture would be cleared. Crops would be planted in April/May using stone or shell hoes. The forests around the dwelling area would be cleared by burning the undergrowth to make game easier to see and hunt. 9 Burning the undergrowth also created open land for crops and provided the soil with nitrogen, an important fertilizer.

It’s not known how large the area that Roger and his company made use of before it was reduced to four acres. Crops grown were likely corn, squashes, beans, pumpkins, artichokes, and tobacco. 10 In the 1620s-1670s, some Indigenous groups also raised domestic animals, such as pigs, to sell for cash.

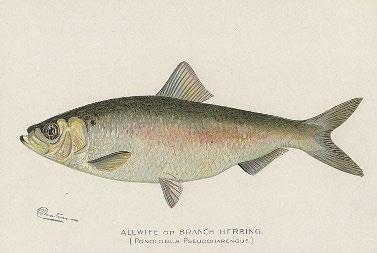

The river was actively fished, especially during alewife, salmon, and shad spawning seasons. The people had sophisticated tools including fishing nets, lines weighted with pebbles, harpoons, spears also known as leisters, hooks, and bone tools known as gorges. 11 The people also constructed fishing weirs, or traps, made of stone and other materials. In other towns such as Concord, Massachusetts, for example, Indigenous stone fishing weirs would later be replaced by dams in the 17th and 18th centuries. 12

There’s no written record of what happened to “Roger & his company” after 1646. The Indigenous people living in the lower Merrimack River valley didn’t “disappear” after 1646, as was erroneously held as fact throughout much of the 20th century. All or some of the group may have moved north to other Pennacook-Abenaki communities in New Hampshire or near Canada. Some may have assimilated into the English population of Andover.

The 19th century idea of “the last Indian” is a false expression. Through intermarriage, some people assimilated into the English culture. Others, such as Nancy Parker, continued to live in the area, married within their community and had children who also stayed in the area. 13

Indigenous people, since first contact to today, continue to work to maintain their communities and cultures.

It’s not known how many Indigenous groups had settled along the Shawsheen River pre-1646. Some researchers have found evidence of groundworks, that they identify as “forts,” throughout the lower Merrimack and Shawsheen Rivers, and local brooks, and ponds. It’s possible that the groundworks indicate where Indigenous settlements were located. 14

9 Strobel, 40-42

10 Fuess, Claude, The Story of Essex County, p60-61

11 IBID, 47

12 journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1093/envhis/emx123

13 Bell, 149-150

14 Fuess, 43-46

of

5 | Page

The Human History

the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

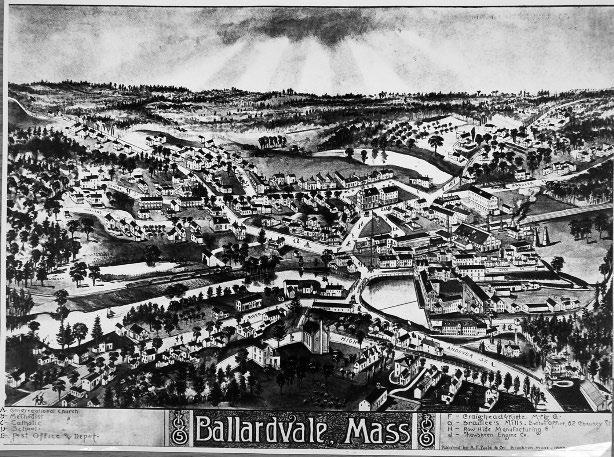

Colonists settled in the same resource-rich places as the Indigenous people, there could have been settlements in what is now Ballardvale, Stevens Street, and Shawsheen Village. 15

PART 2: Post 1646 through 1700 Introduction

The Indigenous people’s way of living was very different from the English settlers’ ways. For example, instead of being organized into divisions that could be neatly mapped with clear, unmovable boundaries (cities, towns, counties, etc.). The local Indigenous people were organized into bands that were fluid depending on marriage and familial alliances, and strategies of leaders.

Attitudes and understandings about land use and ownership between the Indigenous people and the English settlers were inherently different. For the Native people, land was associated with people as long as they used it. When the users of that land moved on, the land was open for use by others. The English concept of absolute land ownership led to misunderstandings and abuse as Indigenous people’s rights to their land was taken away.

The land loss experienced by Native people exemplifies the power dynamics between Native people and English colonists. Some land was purchased legally, according to English law, but most often vastly undervalued. Some land was acquired through questionable, coercive, fraudulent, or corrupt means. 16

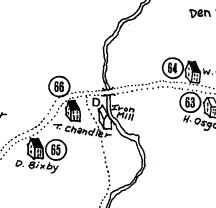

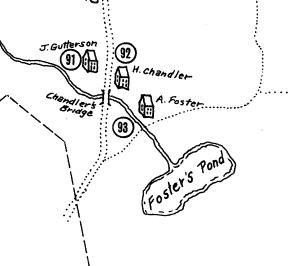

Map of 1692 17

The original English settlement of Andover was in what is now called North Andover. English colonists settled together around the meeting house. Homes were to be built nearby and it was intended that families would live close to the meeting house. Wood lots and land for planting were often situated far from the meeting house. Given the distance between home and farm land, colonists often built dwellings close to their land to make their work easier. Their primary homes, however, were still required to be

15 Strobel, 13-14

16 Strobel, 80

17 Map of Andover 1692, researched and created by the Andover and North Andover Historical Societies, 1995

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 6 | Page

near the meeting house. This arrangement didn’t last for very long. Within 30 years of settlement the south part of town was settled and had a higher population than the original settlement.

Mills and the colonial economy

English settlers came from an environment with scarce natural resources and plentiful labor. The New England environment they settled had the opposite: plentiful natural resources and scarce labor. The economy the settlers created was dependent upon what has been called the “4 F’s”: furs, fish, farms, and forests. Water and wood were central to the economy. 18

Because of the dependency on wood, a sawmill was often the first commercial building built in a new community. Wood was needed for homes and for building other necessary mills. In addition to saw mills, grist mills for grinding grain were critical to the survival of a community. Iron manufacture was also needed to produce fasteners/nails, plowshares, horseshoes, cookware, firearms, and other edged tools.

Colonial mills were built by millwrights. A successful millwright’s skills could include that of a carpenter, joiner, stonecutter, mason, blacksmith, wheelwright, and surveyor. 19

Mills were so important that communities often offered inducements to attract millwrights. Inducements could include free mill site and adjoining land, tax exemptions, monopolies, military exemptions, and cash. Miller’s fees were not small, often ¼ of the lumber or grain produced was charged. However, despite the high fees, noise, water usage, pollution created by mills, millers and millwrights were valued members of the community. 20

Mill and overshot wheel illustrations 21

A good mill site needed to have a water source, which could be a river or a stream. An overshot wheel needed 10’ of head or water height to produce enough energy to move the wheel and power machinery. Dams and waterways were built to create millponds that served as a reservoir during dr y times of the year and gave the miller control over water flow. 22 The weight of the falling water and the velocity of the water when it hit the wheel’s paddles or buckets determined the amount of power the wheel could

18 Colonial America’s Pre-Industrial Age of Wood and Water

19 IBID

20 IBID

21 Lord, Phillip, Mills on the Tsatsawassa: Techniques for Documenting Early 19th Century Water-Power Industry in Rural New York

22 https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-mills-corporations/

| Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 7

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

produce. A good overshot wheel used 50-70% of the water’s energy. The mill site also included a mill trace to carry water to the wheel, a sluice with a gate called a penstock to direct water onto the wheel, and a traceway to carry water away.

The post-contact history of Andover and New England is tied to two terms related to mills: “mill privileges" and "flowage rights”

• “Flowage rights” for a dam set a pre-determined level of water behind the dam to ensure a steady flow of water to serve mills located downstream.

• A “mill privilege” conferred the right of a mill-site owner to construct a mill and use the power from the stream to operate the mill with due regard to the rights of other owners along the stream’s path.

There are a few concepts wrapped up in those two definitions.

Early New England settlements and towns were based on the practices and legal structures settlers brought with them from England, including the use of common land. For example, towns like Andover were built around a central Common where residents could let their animals graze.

The same approach applied to common use of rivers and streams. Long before the English settlers arrived, the Indigenous people relied on waterways for transportation and drinking water, and were an important source of food.

English settlers continued to use waterways in these same ways. Settlers followed the English Common Law concept that “water flows and ought to flow, as it has customarily flowed.” In New England, however, English settlers’ need for building materials and grain often conflicted with this practice of the common waterway.

Because mills were expensive to build and required special skill to maintain, a miller’s monopoly on the service was governed by the social contract that in return for the miller’s investment and mill privilege residents would be charged reasonable rates for the use of the mill.

The associated flowage rights assured that the miller could build a dam or change the flow of the stream to meet the needs of the mill. In return, he was responsible and legally liable for the effects of his actions on people upstream and downstream from him. If the miller’s dam caused a farmer’s fields to flood, for example, the miller was responsible for reimbursing the farmer for his loss. By those same rights, residents upstream and downstream from the mill could legally break the miller’s dam and return the stream to its natural course until the issue was settled in court. Everyone had equal rights to the waterway. 23 23

8 | Page

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-mills-corporations/

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

17th century mills in Andover

In Andover, as in other New England towns, mill privileges and flowage rights were granted by the town's governing body and were included in property deeds, as we see here with the Shawsheen River and Hussey’s Pond.

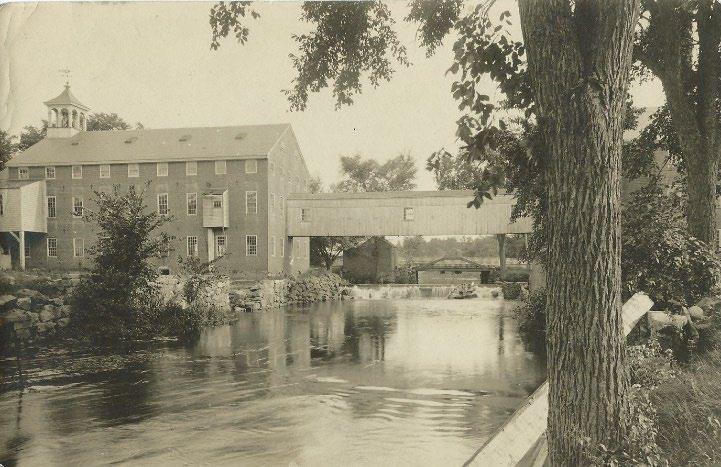

As early as 1682, Andover Town Proprietors granted a “mill privilege on the Shawshin near Roger’s Brook to any inhabitant willing to build a sawmill.” Joseph Ballard erected a grist mill along the Shawsheen River in what is now Ballardvale. 24 Joseph and John Ballard later were the first to establish a fulling mill in Andover.

Fulling is a critical step in woolen production. A newly-woven piece of cloth is loose and airy. Fulling is the process of consolidating the fibers to form a denser fabric. Woven fabric is first cleaned of grease and oils using an acidic liquid, such as stale urine. The cleaned fabric is beaten to compact the threads. Fulling mills used enormous water-powered hammers or beaters. The rhythmic thump of the beaters would have been a familiar sound for those who lived near the mill. 25 Other mills were established along the river in the 17th century. 26 Further back on Roger’s Brook leading to the river, in 1675 a tannery was in operation using water power from the brook and draining into the Shawsheen River. 27

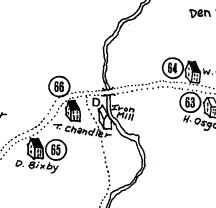

Moving north, in 1678, Thomas Chandler 28 ran his iron works along the river off Stevens Street on the west side of the river. Chandler was a blacksmith by trade and served as a Representative to the Massachusetts General Court.

Detail from 1692 map showing Chandler’s iron mill

24 Historic Preservation website, 210 Andover Street

25 http://www.witheridge-historical-archive.com/fulling.htm

26 Bailey, 102

27 1692 map of Andover

28 Thomas Chandler is also known for his role in the Salem witch trials of 1692.

9 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

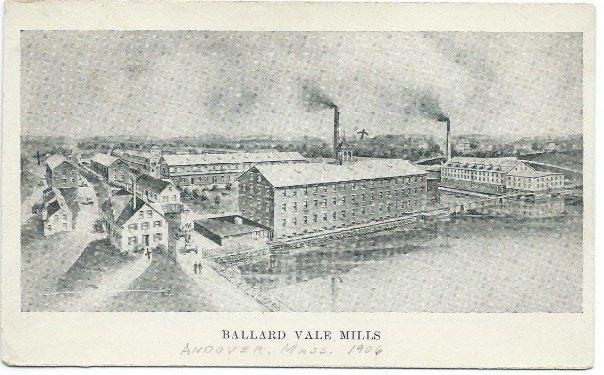

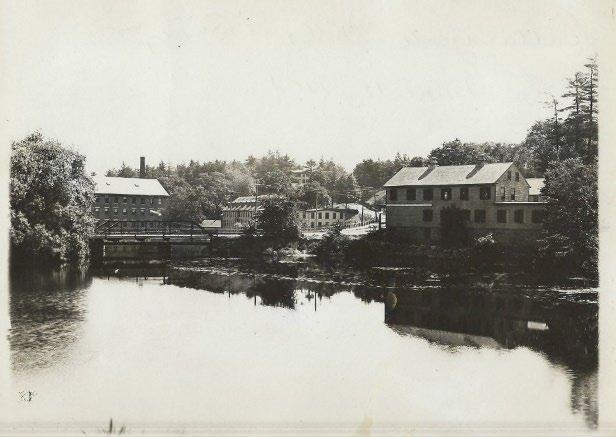

Among other locations around town, mill privileges in Andover were granted at what would become the town’s four mill districts along the Shawsheen River: Ballardvale, Abbot Village, Marland Village, and Frye Village.

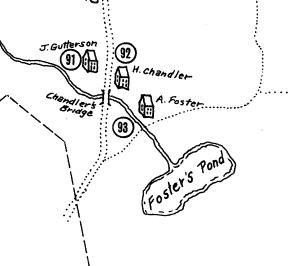

17th century bridges

The 1692 map of Andover shows homes, mills, and farms all along the Shawsheen River, along with the bridges that crossed the river. On Stevens Street, a bridge was constructed next to Thomas Chandler’s iron mill. 29 Further south, the “Little Hope Bridge” crossed the river at the intersection of Lupine and Central Streets, and in Ballardvale on River Street was Chandler’s Bridge, named for William Chandler The brook running from Foster’s Pond ran under Chandler’sBridge.

Other 17th century uses of the river

Fishing was another use of the river during the second half of the 17th century. In 1681, a 21- year monopoly on fishing places from the mouth of the Merrimack River 20 rods (330 feet) downstream on the Shawsheen River was granted to Captain Bradstreet, Lieutenant Osgood, and Ensign Chandler. 30 The 20 rods didn’t extend very far up the Shawsheen River, but the mouth of the river was certainly the most lucrative location. The English settlers harvested the same fish from the river that the Indigenous people did: alewives, herring, salmon, and shad.

In 1692, during the Salem witch hysteria, Samuel Wardwell claimed that he was induced to make his signature in the Devil’s book and was baptized in the Shawsheen River.

29 1692 map of Andover

30 Bailey, p152

10 | Page

Detail from 1692 map

PART 3: 1700s Introduction

By the early 1700s, the settler population of Andover had grown and people were settling and building homes farther away from the Old Center and the Meeting House. The southern end of Andover was by this time more heavily populated that the original settlement.

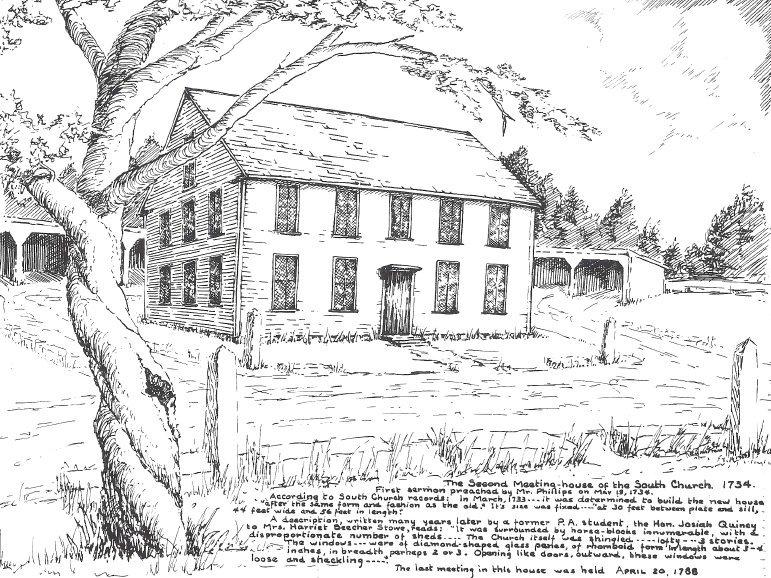

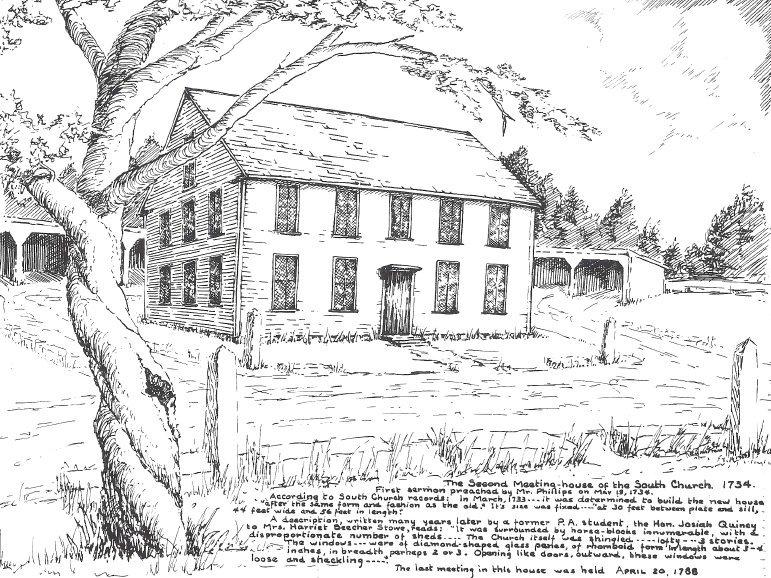

In 1705, the people of Andover voted to build a new meeting house and debate ensued over where to build a new meeting house that would serve the entire town. In 1708, the General Court of Massachusetts decreed that the town could support two churches and so would be divided into two precincts, each with its own church. The South Parish Church was “to be set at ye Rock on the West side of Indian Roger’s Brook.” October 17, 1711, the parish secured their first minister, 22-year-old Reverend Samuel Phillips.

31 https://www.thecricket.com/news/the-alewives-cometh/article_02dbec58-9780-11eb-b375-7f236b29d932.html

32 ACHC #1992.161.11

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 11 | Page Alewife illustration 31

Illustration of what the original South Parish building might have looked like.

32

The

Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

18th century mills

Throughout the 18th century, more mills along the Shawsheen River were erected and operated as Andover’s industrial villages were formed. Additional saw mills and grist mills were erected, and the Chandler iron mill continued. New mill interests constructed during the 1700s included cider, fulling, paper, and gun powder mills.

In Ballardvale in 1753, Humphrey Holt sold to Asa Abbot one half of a sawmill he had erected on the “Shawshin” river near Pine Plaine, also known as Preston’s Plain south of Ballardvale 33 By 1794, Ballardvale Village held a sawmill, grist mill, and cider mill constructed and operated by Timothy Ballard. 34 In her book Historical Sketches of Andover, Sarah Loring Bailey recorded that in 1771 a freshet 35 “carried away Widow Ballard’s mill dam.” 36

Further north along the river, other mills were constructed close to Thomas Chandler’s iron works. 37 Two other Chandler brothers, Henry and Joseph, established a sawmill nearby. In 1745, the Lovejoy family purchased rights to a grist mill and a share of the dam that powered it. 38 Joshua Lovejoy purchased the Chandler iron works on the west side of the Shawsheen River along with a 3/8th share of what was then called the Abbott/Lovejoy dam (where the Marland Mills would one day stand).

In the same general area, early in the Revolutionary War, the grandson of South Parish’s first minister, Samuel Phillips, Jr, saw the need for gunpowder and set up a gunpowder mill located on the Shawsheen River near the junction of what is now North Main Street and Stevens Street.

33 IBID, 210 Andover Street

34 IBID, 214 Andover Street

35A freshet is the flood of a river from heavy rain or melted snow, Oxford English Dictionary

36 Bailey, 604

37 Loring, 580

38 Historic Preservation website, 88 Lowell Street

12 | Page

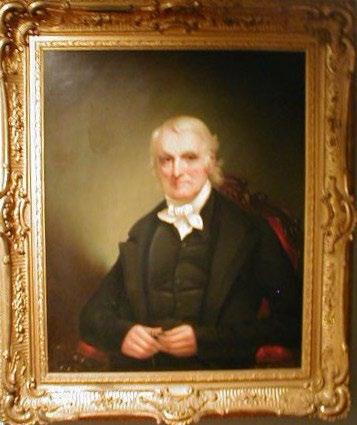

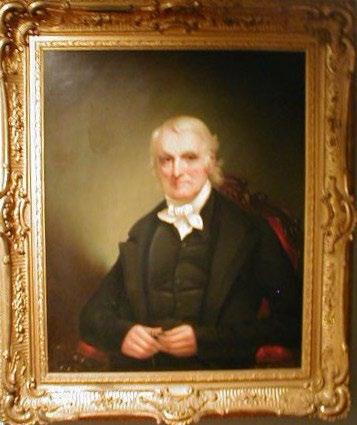

Samuel Phillips, Jr., owner of Andover’s gunpowder mill

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Phillips recruited friend and trained chemist Eliphalet Pearson to assist with the operation. The new mill on the Shawsheen River ran day and night producing 1,200 pounds of ammunition for the Continental Army. General George Washington was unimpressed by the quality of the gun powder and sent it back to the Andover mill. Phillips found skilled British prisoners of war and put them to work manufacturing a better-quality gun powder. Local residents feared the combination of enemies and gun powder in their midst. On June 1, 1778, an explosion at the mill killed three men and partially destroyed the mill. So great was the need for gunpowder during the war that the state sent Phillips money to rebuild the mill. At the end of the war, Phillips turned to the far less risky business of producing paper. 39

Finally, in the north part of town, in the village that would be named for him, in 1718 Samuel Frye built saw and grist mills along the river. His son later added a fulling mill.

In 1765, a mill privilege on Hussey’s pond was deeded for a saw mill. Hussey’s Pond drains into the Shawsheen River. Over the next 150 years, a number of mills and other businesses were built between Hussey’s Pond and the Shawsheen River. 40

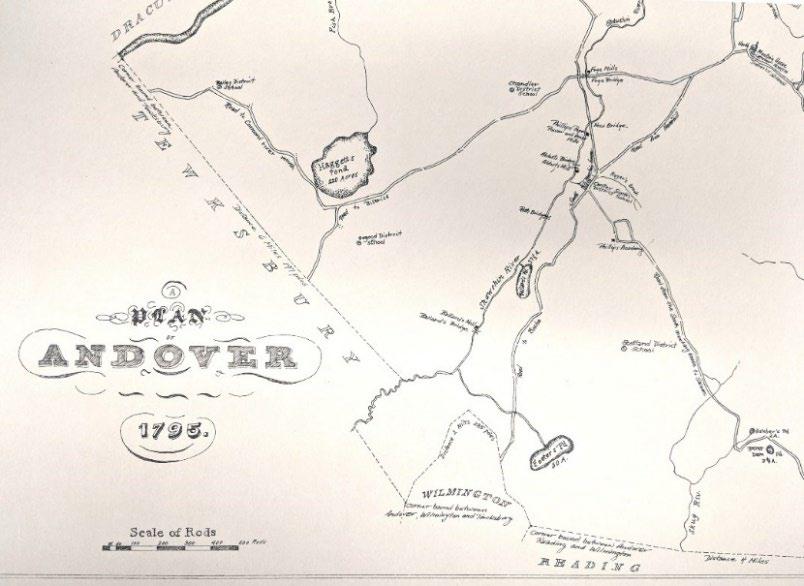

18th century bridges

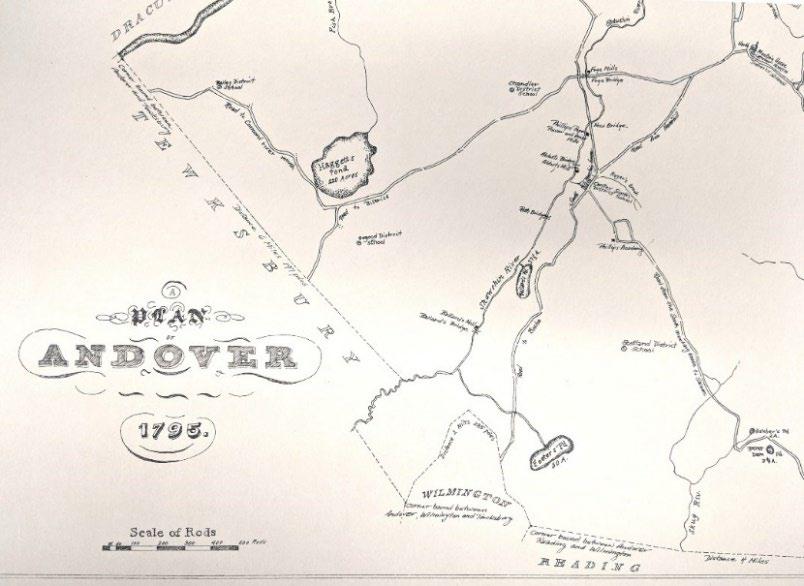

A 1795 map Andover shows bridges crossing the Shawsheen River. Ballard’s Bridge crossed the river near the Ballard mills. The “Roth Bridge” replaced what had been called “The Little Hope Bridge” at Central Street and Lupine Road. There was a bridge at Abbot’s mill, close to Roger’s Brook. A “new bridge” was constructed at the Phillips gunpowder and grist mill in the Stevens Street area. Further north, Frye Bridge crossed at Frye’s mill. Bridges were often, but not always, built close to mills. Causeways were used prior to the construction of bridges.

13 | Page

Detail from Plan of Andover 1795 PART 4: 1800s

39 Mofford, 66-67 40 Bailey, 580

Introduction

“While the newest resident may think of Andover as organized by roads, it was actually oriented toward the Shawsheen River. Main Street did not exist until 1806, and Central Street, the main thoroughfare to Boston, paralleled the river. Water powered the early mills, so population centers grew up along the Shawsheen: Ballardvale, Abbot Village (around present-day Dundee Park), Marland Village (Stevens Street), and Frye Village (now Shawsheen Village).” 41

As Andover’s industrial villages continued to grow and change throughout the 1800s, the names of mills and the products they produced become more familiar to us. For example, by the end of the 19th century, because local production of flour and ground grain was no longer necessary to the survival of the community, grist mills were gone from the landscape. Woolen mills and factories were in operation all along the river until the mid-20th century.

Starting in the mid-1800s, as the coal mining industry grew and railroads expanded, the power-supply for New England mills began to shift from water-power to coal-power. Dams that powered the mills in the first half of the century became less important by the end of the 19th century.

The dams and mill ponds that powered New England industry since 1646 stayed in place even as coal replaced water power. But the mill ponds and heightened water level the dams brought new, recreational uses for the river that would blossom in the early 20th century.

Detail from 1830 map of Andover

41 Richardson, Eleanor Motley, Andover: A Century of Change 1896-1996, for the Andover Historical Society, 1995, page 79

14 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Social, Cultural, Recreation

The mineral springs that fed into the Shawsheen River became destinations in the early 1800s. In 1812, Mssrs. Holt and Osgood made improvements to the mineral spring on what would become Red Spring Road. The site was visited by “many invalids from all parts of the state, who remained in town for a season, to enjoy its invigorating benefits.” 42 In 1890, Paul Hannegan of Lawrence bought the Red Springs and made improvements to the site, including a reservoir to store water that he would take to market. Water continued to flow from a pipe on the site for individual use, “Two weeks ago Sunday the number who drank from the spring was over 300.” 43

In Ballardvale, the mineral springs became the “Lithia Springs” bottling company.

With industrialization came the new concept of leisure time. Individuals, small business, and big companies searched for and created opportunities for people to spend their leisure time. Small businesses rented and sold bicycles and canoes.

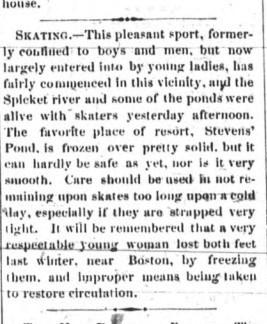

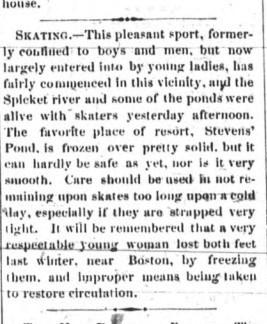

During the winter months, ice skating on mill ponds along the river was a popular, but unsafe, activity. Unheeded warnings sometimes had dire consequences.

15 | Page

Lawrence American/Andover Advertiser, December 1866 and December 1867 42 Andover Advertiser, June 5, 1858 43 Andover Townsman, May 31, 1890

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

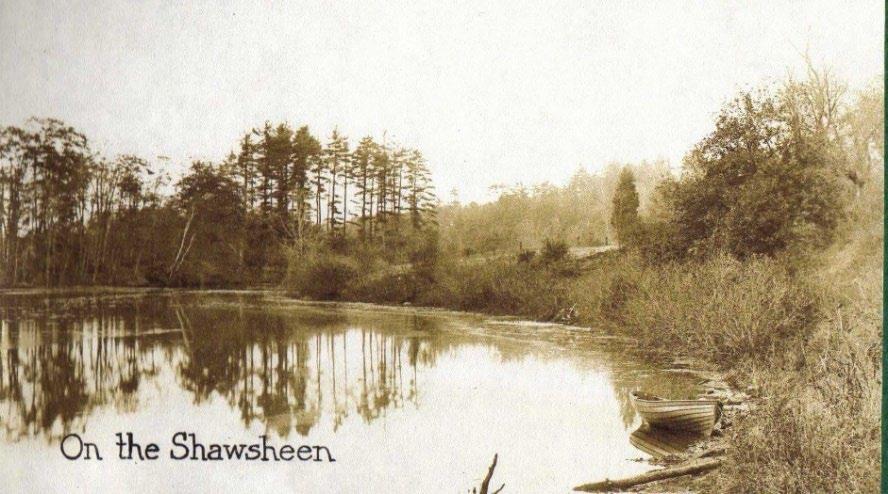

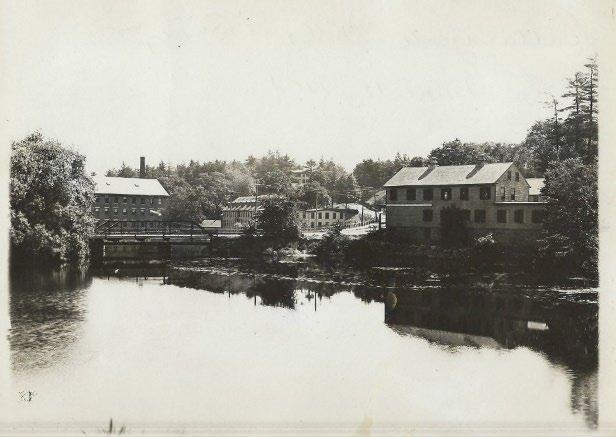

Railroad companies created leisure destinations along their lines to attract passengers. Ballardvale became one such destination in the late 1800s into the early 1900s. Recreational use of the Shawsheen River would rise dramatically in the first few decades of the 20th century.

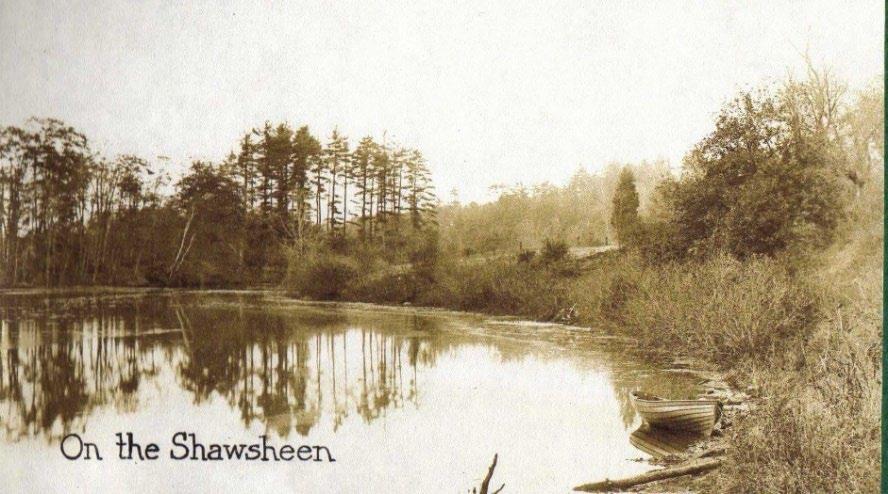

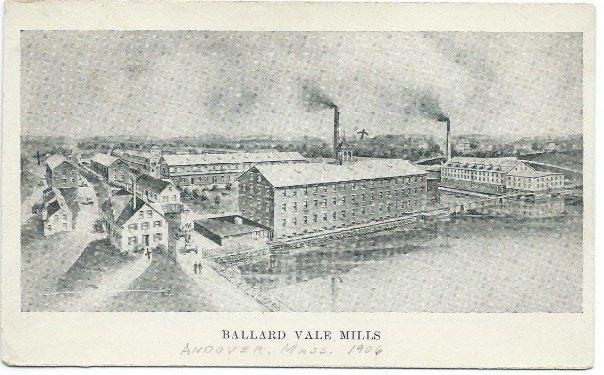

Postcard, ACHC #1983.080.358

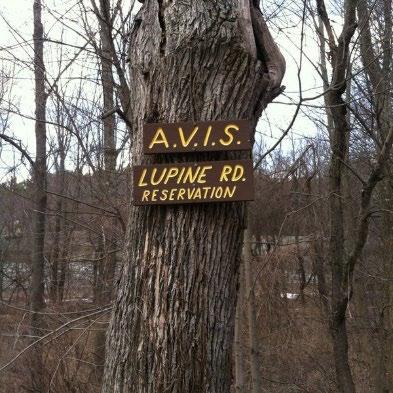

In 1894, the Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) was formed to preserve the character and natural resources of the town. AVIS is the second oldest land preservation society in the U.S. Acquisition of open space, including reservations along the river, increased in the 20th century and by 2022, the organization owned 29 reservations totaling approximately 1,100 acres.

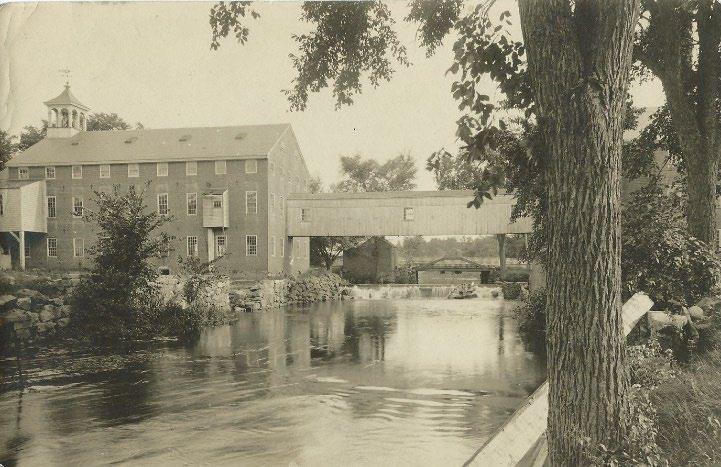

19th century Andover mills

Starting in the south part of town, the mills in Ballardvale continued to change hands throughout the 19th century. In 1833, Abel Blanchard, who was a paper maker, purchased the grist and saw mills, and water privilege from Timothy Ballard’s estate. The next year, the deed was sold to a group of four men –Daniel Poor, Abel Ballard, Abraham Gould and Mark Newman. The group laid the foundation of a brick mill intended to be a paper mill, however, in 1835 they incorporated as the Ballard Vale Manufacturing Company and partnered with John Marland to produce woolen goods. 44

44 Mofford, 99

16 | Page

Postcard, ACHC #2017.062.83

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

In 1838, Ballard Vale Manufacturing Company raised and improved the dam crossing the Shawsheen River. That same year, due to flowage rights and laws, property owners above the dam, whose property was damaged by the change in the river, were awarded compensation. 45

In 1844, John Marland built a wooden mill building for woolen production. He piped water from the springs (later called the Lithia Springs) to his woolen mill for use when fulling fabric. The minerals in the water produced a higher-quality product. 46 Marland later sold the mill to J. Putnam Bradlee. 47

Moving north along the Shawsheen River, in 1810 Abraham Marland established a cotton mill. The next year he converted the mill to woolen production. Worsted blankets produced by Marland’s mill were used by troops during the War of 1812. Many years later, in 1890, the Abbot mill was demolished and the Smith and Dove Village Hall was built in its place (Essex Street at Gradall Lane). This area would become known as Abbot Village, and later still, Dundee Park.

45 Historic Preservation website, 210 Andover Street

46 IBID, 52 Porter Road

47 IBID, 214 Andover Street

17 | Page

Photograph of the Ballardvale mills, ACHC #1989.90.01

Card, ACHC #1995.009.18221

In 1813, Abel and Pascal Abbot established their woolen mill on the west side of the river where the former Redman Card Company operated (Oak & Iron Brewery today). 48 In 1824, John Howarth built the stone mill on the east side of the river to produce woolen goods. The stone mill still remains and is the oldest building in the Dundee Park complex.

Major changes came to Abbot Village in 1843 when the Abbot mill was sold to the Smith and Dove company. Smith and Dove would go on to purchase the Howarth Mill, which was razed in 1895 Over the next 50 years, the company gradually moved from its previous location in Frye Village to Abbot Village, enlarging, razing, and rebuilding the mill buildings to suit production. In 1843, the company had expanded operations to Abbot Village. By 1880, three hundred operatives were processing two million pounds of flax each year. 49 By 1894, Smith and Dove had moved all of its operations to Abbot Village. The company also provided housing, a community center, and recreational facilities along the river. 50

Further north along the Shawsheen River, Marland Village also grew throughout the 19th century. In 1820, Abraham Marland began to move his operations from Abbot Village to the new village that would bear his name. He first leased and later purchased mill and water privileges, the old paper and grist mills, and worker tenements. M.T. Stevens purchased the mill in 1879. 51 By 1896, the Marland Mills employed 200 operatives and manufactured 875,000 pounds of wool yearly.

48 IBIC 63-65 Essex Street

49 Richardson, Eleanor, A Century of Change, p81

50 IBID, 14 Dundee Park

51 Richardson, p84

18 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Abraham Marland, ACHC #1980.0132.11

Heading further north in the area of Penguin Park, in 1830, Ephraim Mayo established a brick and tile yard on clay flats along the river.

In Frye Village, in 1829, the Smith and Dove mill opened. The company started producing cotton, but switched to linen in 1833 because the owners did not want to be associated with the southern slave states and cotton. The mill was powered by the Shawsheen River. The company moved to Abbot Village by the end of the 1800s.

Also in Frye Village, in 1830, Elijah Hussey bought the grist and saw mills and laundry stocks on the west side of the Shawsheen River. Water to power the mills came from Hussey’s Pond, which drains into the Shawsheen River. The laundry operation would continue in this location, under a number of owners, into the 20th century.

In the second half of the 19th century, Andover’s industrial villages along the Shawsheen River became home to substantial industrial textile factories. These large factories required more power than their predecessors. Large mills required “broader, sturdier dams, wider and stone-lined raceways that resembled canals more than the narrow, shallow sluices and wooden troughs of pre-industrial times; and bigger, more powerful, and faster-moving waterwheels. Their buildings were usually made of stone or brick rather than wood, and rose as high as four or more stories. Rather than just one or two mill hands, each of the new mills employed dozens – sometimes hundreds – of men, women, and children.” 52

By the 1870s, the textile factories had outgrown water power. The newly-expanding American coal industry and railroad system provided the fuel for new coal-fired steam boilers.

19 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

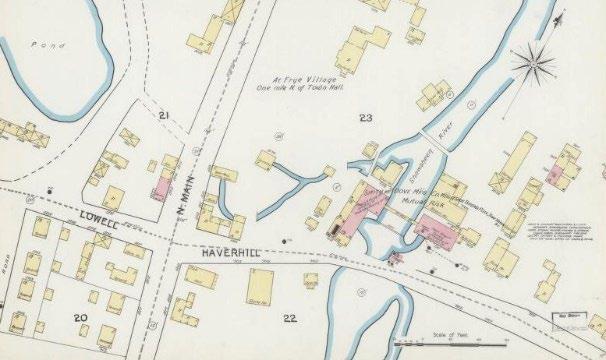

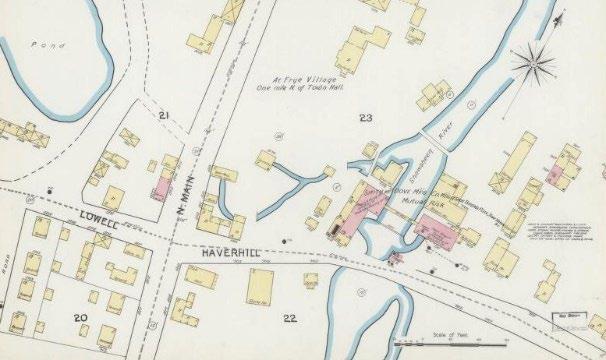

Sanborn map of Frye Village, 1892

52 https://millmuseum.org/swift-waters-the-industrial-environment/

Along with larger mills came more water pollution. Tanneries, like the one on Roger’s Brook, were among the worst polluters, followed by pulp and paper producers. Sawdust from saw mills settled into riverbeds and behind dams, contributing to flooding. Organic material, like the acidic liquids used by fulling mills, depleted oxygen in the water, killed aquatic life, and spoiled water supplies.

Until the mid-1800s, fabric dyes came from natural sources: insects, roots, plants, minerals. In 1856, the first synthetic dye, made from coal tar, was discovered. With the invention of chemical dyes, run-off from textile mills became more toxic. 53

As industrial use of rivers grew throughout the 19th century, water use laws changed. Early laws could resolve differences between individuals and a small number of parties, however that changed as corporations and factories grew. The later 19th century adoption of reasonable use laws favored industrial polluters without necessarily unfavorably impacting other water users. However, the balancing tests that followed allowed industrial companies to take water use and land from others without compensation. Since that time, new layers of laws have been added to protect the interests of others, including the recreational use of water resources. 54

Railroads

The first railroad to come to town was the Andover Wilmington Railroad in 1835. The track was laid through Lowell Junction on the east side of the Shawsheen River across Preston’s Plain. 55

53 https://library.si.edu/exhibition/color-in-a -newlight/making#:~:text=In%201856%2C%20an%2018%2Dyear,product%20of%20coal%2Dgas%20production.

54 Paavola, Jouni, Water Quality as Property: Industrial Water Pollution and Common Law in the 19th century United States

55 Historic Preservation website, 268 Andover Street

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 20 | Page

Smith and Dove flax mill in Frye Village, ACHC #1948.07.92

As the mills expanded, railroad lines were relocated to be closer to the mills of Ballardvale, Marland, and Abbot Villages, and the Shawsheen River. 56 New lines were added to bring coal and supplies to the mills. The new rail lines also served the new city of Lawrence which was established in 1845. The train tracks were laid in 1847 and opened in 1848.

PART 5: 1900s Introduction

Three major employers in Andover were located along the Shawsheen River in the first half of the 20th century: Smith and Dove Manufacturing, Tyer Rubber Company, J.P. Stevens/Marland Mills, and the American Woolen Company.

As strong as the industry was at the beginning of the 1900s, the 20th century also brought the decline of the textile industry in New England. The use of coal contributed to its demise. 57 Freed from the bounds

56 Andover To wnsman, December 2, 2021

57 Water Power, Industrial Manufacturing, and Environmental Transformation in 19th-Century New England,

History of

1/12/2023 21 | Page

The Human

the Shawsheen River,

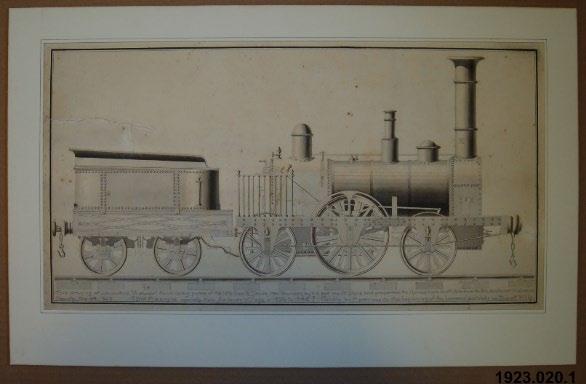

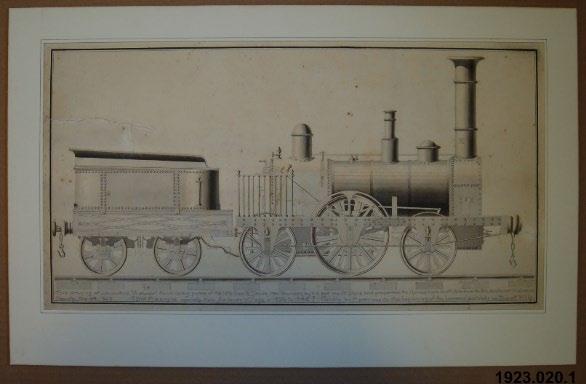

Illustration of the first train to come to Andover in 1832, ACHC #1923.02.01

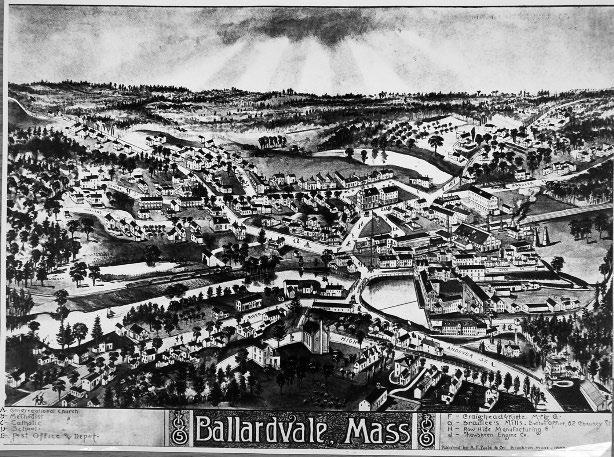

Bird’s eye view map of Ballardvale, 1885

of the river, textile manufacturers could look elsewhere for cheaper sources of fuel and labor, and built new mills in the southeastern United States. New England’s textile manufacturers were largely gone by the 1970s.

At the start of the century, recreational use of the river blossomed as people took advantage of leisure time to indulge in new outdoor recreations of the day. In the later 1800s, bicycling was one of the first new outdoor activities that took advantage of some of the relaxing of social rules. Bicycles gave people, especially women, a new freedom of movement.

Canoeing, the popularity of which started to rise during the later years of the 19th century, reached its peak during the 1920s. Like bicycling, canoeing gave people a new freedom of movement and association, “In the latter years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, a canoe offered sweethearts a pleasant and chaperone-free means to be alone for a time. Almost any waterfront park had a canoe livery where couples could get on the water and escape prying eyes and ears.” 58

Canoeing took place in between the dams and mill ponds: from neighboring Tewksbury to the Ballardvale dam, from Ballardvale to Dundee Park, Dundee Park to the Marland dam, and Marland to Shawsheen Village, and north of the ornamental dam in Shawsheen Village.

Many factors went into the community’s evolving relationship with the river over the 20th century. For example, after reaching its peak with one generation, canoeing fell out of favor with the next generation who looked elsewhere for new forms of entertainment. The automobile, as a major example, gave people unprecedented freedom of movement to look for entertainment outside their local environs.

As the old textile industry left Andover in the second half of the 20th century, new dirty industries took their place. River pollution increased and recreational use dropped away. As the impact of industrial waste was brought to light, the conservation movement picked up steam in the second half of the 20th century. In Andover, the work of AVIS, the Andover Village Improvement Society, shifted from beautification projects to land acquisition and conservation. 59

Social, Cultural, Recreational

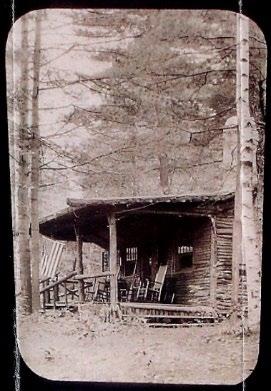

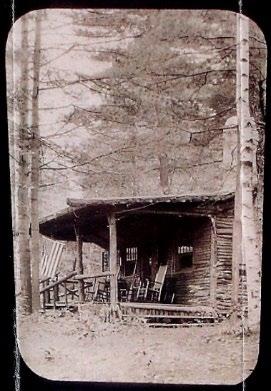

From the 1890s through the 1930s, recreational use of the Shawsheen River was at its peak. Along the river south of Ballardvale and into neighboring Tewksbury, in what was called Shawsheen Pines, rustic camps dotted the landscape.

https://canoemuseum.ca/2012-02-10-canoodling-with-st-valentine/

22 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

58 Canoe Museum,

59 Mofford, AVIS, p91-99

In Ballardvale, the Boston and Maine Railroad promoted excursions from the city. Located on a rise west of the river, “The Grove” at Pole Hill was a popular destination. Pole Hill featured a dance hall, three camps, a refreshment stand, canoe rentals, and an oval track used for foot races. Ballardvale resident William Trautmann told of carloads of visitors arriving for a day in the country. Picnicking and canoeing during the day were followed by dancing in the evenings. Train excursions to Ballardvale ceased after a murder was committed on Pole Hill in August 1900. 61 Local groups continued to use sites along the river for picnics and other events.

In the 1920s, “Parker’s on the Shawsheen” was another popular destination. Situated right on the mill pond above the Ballardvale dam, Parker’s rented canoes and had a second-floor terrace and ballroom overlooking the water. 62

Planks were laid across the top of the Ballardvale dam to raise the water level upstream for recreational purposes.

Parker's on the Shawsheen, ACHC #1995.009.129

60 Research files, Andover Center for History and Culture, Camps/Lodges file

61 Richardson, 203

62 IBID, 204

of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 23 | Page

The Human History

Seboois Lodge on the Shawsheen River 60

In the 1930s, Frank Serio moved his family to a rustic home south of Ballardvale along the Shawsheen River. The forest was still mostly open when the family arrived. Serio made improvements to the property in 1935, bringing electricity and phone lines. Frank Serio Sr also built what he called “The Miami Boathouse,” picnic tables, a playground, dance floor, campgrounds, refreshment stand, and a swimming hole. Serios Grove, as it was known, was in its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1959, the Townsman reported that Frank Serio had built a gondola from pictures seen at Memorial Hall Library. It was 15 feet long and 2.5 feet wide. Serio used the gondola to take people for rides to Pomp’s Pond. 63 The Serio family continued to operate the Grove until the family moved away in 1968. 64

From a memoir in the files of the Andover Center for History and Culture, “Back in the early 1900s there was fun for everyone on the Shawsheen River – swimming and skating parties, hockey games and iceboating; and especially the wonderful water sports on the 4th of July: canoe races, canoe tilting contests, diving contests, but one experience topped them all – the cold winter Sunday when a plane landed on the ice near the Andover Street bridge and out hopped Bill Bonner who had dropped down to visit an old friend and to entice him to taxi up the river to the flats in his plane. Soon they were flying over the brick mill. By this time a crowd had gathered and everyone was on edge until they returned safely.” 65

Andover

Further up the River, just north of the Central Street Bridge (Hartwell Abbott Bridge) was the Andover Canoe Club. Horace Hale Smith was the driving force in establishing a boat rental facility and canoe club at this site in 1913. The club’s first boat house for canoe storage was located on the low flats next to the river. Built on stone piers, it measured approximately 20’ x 30’ with a wooden boat ramp down to the river’s edge. The boat house had a gable roof and wide doors giving entry to many canoe racks inside. Access to the site from Lupine Road was a set of stairs that ran down the embankment 66 Joining the riverside boathouse was an old rubber plant building relocated to become the clubhouse on the east Lupine Road. It is now a private residence.

63 Andover Townsman, July 23, 1959, p1

64 Adams, Tom, Andover Townsman, Andover Stories, Discovering Serio’s Grove, November 4, 2021

65 Shawsheen River research file, Andover Center for History and Culture

66 Article by Jim Batchelder in the research files of the Andover Center for History and Culture

24 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Canoe Club

Members of the Andover Canoe Club, ACHC #1996.076.54

Canoe club members hand dug a canal from the river to Pomp's Pond. A 1915 map of the "Ballard Line" calls it the "most picturesque scenic excursion in eastern Mass." A motor yacht was introduced which required just 10” of water. It was named the William Ballard and could hold 30 passengers. The canoe club held regattas beginning in 1912. The club would become the largest of its kind north of Boston. Club membership dwindled during World War I and Horace Hale Smith moved away in 1920. 67

In an Andover Townsman article from 2006, Bill Dalton wrote about the boathouse,

It disappeared sometime in the ‘30s …inside it were racks with 8 to 12 canoes resting upside down. These canoes were available to the general public for a fee, and many times my father would rent one and load up such members of the family that wanted to paddle off. I think we always went up river. Not too far down the river you came to Frye (Abbot) Village and a dam, which furnished power for a textile mill. So, we went up the river, never to Ballardvale, but always taking a tributary stream that got very narrow, usually requiring some portage, and finally took you to Pomp’s Pond. .

The Andover Sportsmen’s Club hosted an annual fishing derby on the river on opening day of fishing season in the 1950s-1970s. And an Annual Canoe race from the Central Street Bridge to Ballardvale and back was popular in the 1970s and 1980s. 69

20th century industry along the Shawsheen River

Early in the 20th century, ice was harvested from the Shawsheen River. In 1901-1902, Nuckley and Haggerty advertised "Pure River Ice" along with their ice houses on River Street, Ballardvale. Brooks Holt, and later People's Ice, cut and sold Shawsheen River ice. 70

The Ballardvale mills continued to change hands throughout the century. On the west side of the river, the Bradlee mill building continued in the woolen industry until around 1960. After that the mill buildings became home to a number of small businesses. On the east side of the river, the Shawsheen Rubber Company continues to operate today.

67 Article by Jim Batchelder in the research files of the Andover Center for History and Culture

68 Andover Townsman, October 19, 2006, Bill Dalton

69 James Batchelder

70 Andover Historic Preservation website, 326 South Main Street

25 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

.” 68

Ballard LIne map

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Moving up the river to Abbot Village, b y 1894, the Smith and Dove Company had moved all of its operations there from Frye Village. Most of the earlier mill structures were then enlarged, razed, and rebuilt. Smith and Dove remained one of the largest employers in Andover from 1843-1927.

The James Howarth "Stone Mill" building, which sits on the east side of the river, is now the oldest original mill building in the industrial complex of the former Smith & Dove Manufacturing Co. When Smith and Dove was in full operation in Abbott Village there were three separate employee bridge passageways across the river. 71

1923 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Library of Congress

In 1928, Smith and Dove was sold to the Ludlow Manufacturing Company. Subsequently mill ceased operations in 1928. In 1953, the former Smith and Dove buildings and housing inventory was sold in individual parcels. Private investors owned pieces of Dundee Park until 1997 when Ozzy Properties purchased the complex.

71 Andover Historic Preservation, 16 Dundee Park

26 | Page

Smith and Dove mills, Dundee Park, ACHC #1989.872.1

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

In 1945, Ruth and Frederick Redman purchased the old Abbot Mill building on the west bank of the river, across from the old Howarth mill. The Redmans operated the last flourishing textile related business in Andover, manufacturing carding and napping wire for finishing fabric. 72

North of Dundee Park was the Tyer Rubber Company factory, built in 1912. This was the third location used by Tyer Rubber since it was founded in 1855. Its first location was in Ballardvale in 1855. Two years later, in 1857, the company moved operations to North Main Street. In 1912, the company built a new steam-powered tire and tube factory on Railroad Street on a hill overlooking the river. In 1961, the company was purchased Converse Rubber and concentrated on canvas footwear and sneakers. 73 The company continued in this location until 1981 when the business was sold and the factory renovated for housing under the name “Andover Commons.” 74

Next along the river was the Marland Mills, which had been producing woolen goods in Marland Village since 1828. In 1964, J.P. Stevens closed the mills and moved operations to the southeast United States, leaving 450 employees without work. In 1994, the Marland Mill was renovated for assisted living facilities. It has continued this function under different owners since. 75

The river powered many mills in Frye Village, dating back to the 17th century. A series of mills existed where Hussey’s Pond empties into the Shawsheen River. The area held a saw mill well into the 19th century. A series of laundry facilities also existed along that waterway.

In this 1856 map of Frye Village, the Smith and Dove dam can be seen as it stretched across the Shawsheen River where Haverhill Street is today.

72 Richardson, p81

73 Richardson, p88

74 Richardson, p87-88

75 Richardson, p85

27 | Page

Tyer Rubber factory, Railroad Street, ACHC #1976.013.54

The early 20th century brought many changes to Frye Village. After Smith and Dove left Frye Village, another textile business moved in briefly. American Degreasing was a short-lived operation to clean raw wool prior to other processing. This was a dirty industry that used toxic chemicals to clean the wool. The company was in operation only a few years, closing in 1906. 76

The people of Frye Village waited three years for a new manufacturer to move into the village. In 1909 concern was raised in the village that the new company would be a fat rendering plant. Such a change would slow the pace of development in the village. 77

76 History Buzz articles, Frye Village Stories: Degreasing plant comes to Andover, March 5, 2021

77 History Buzz article, Frye Village Stories: Taking a deep dive into General Degreasing, February 5, 2021

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023 28 | Page

1856 map of Frye Village

Smith and Dove mill dam, Frye Village, ACHC #1987.598.5123

In June 1909 in the Andover Townsman, Editorial Cinders wrote: “It isn’t good to think what may become of the Frye Village Mill in the light of all the stories that are current regarding the recent sale of it.

Perhaps Mr. McGovern has bought it for the advancement of science or to establish an agricultural school there, or for some other aesthetic use not yet suggested, but current stories would indicate that it is in his mind to use the property for soap making, or some kind of rendering works.

Much as we want to see business come to the town, and the best possible use made of every agent in the town for business, there should be an emphatic and a successful protest uttered at once upon the first appearance of anything of the sort as suggested.

Frye Village is already attractive as many of the residential places located there. It will become more attractive as Lawrence overflows, and not a single thing should be allowed to occur that would injure this growth. No soap works, no rendering plant, no offense of any kind whatsoever should be allowed in any section of residential Andover.”

Fortunately for the people of Frye Village, in August 1909, Mr. McGovern, owner of the old Smith and Dove mill sold the property to Frank Binney, a representative of William M. Wood. The Hardy Brush company relocated to the old mill in 1910. William Wood built a new factory for Hardy Brush and razed the old mill in 1919-1920. 78 Hardy Brush supplied brushes and other equipment to textile mills, including the American Woolen Company. Their woodshop was used to mill all the interior wood trims for the William Wood’s new Shawsheen Village.

The American Woolen Company was, at one time, the largest worsted wool producer in the world. Wood consolidated eight troubled textile factories to create the company. At its height, the company

29 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

American Woolen Company factory, Shawsheen Village, ACHC #1999.548.12

78 Richardson, p89

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

employed 30,000 people and managed factories in Lawrence, Andover, and Fitchburg, MA, Blackstone, CT, and three in Rhode Island.

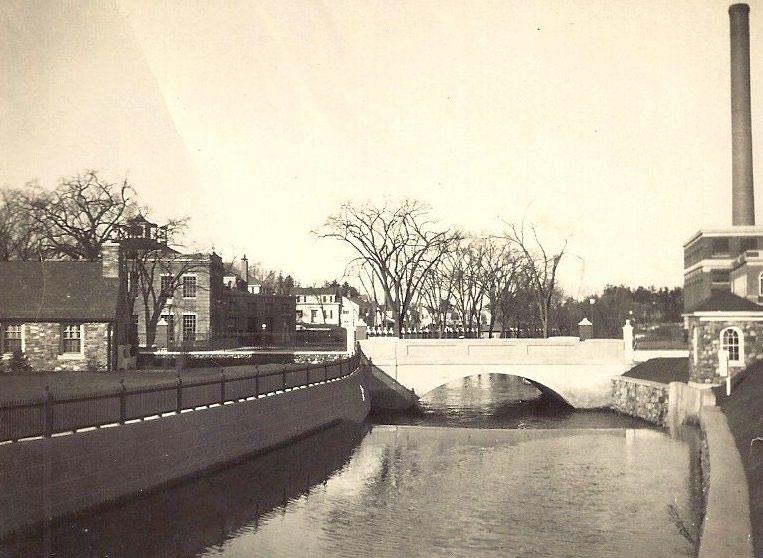

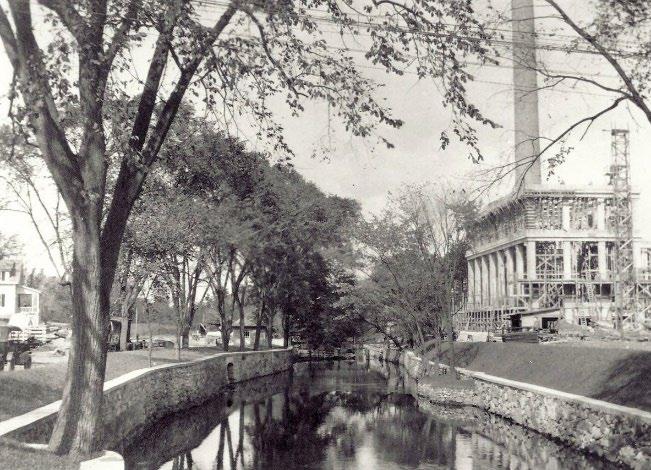

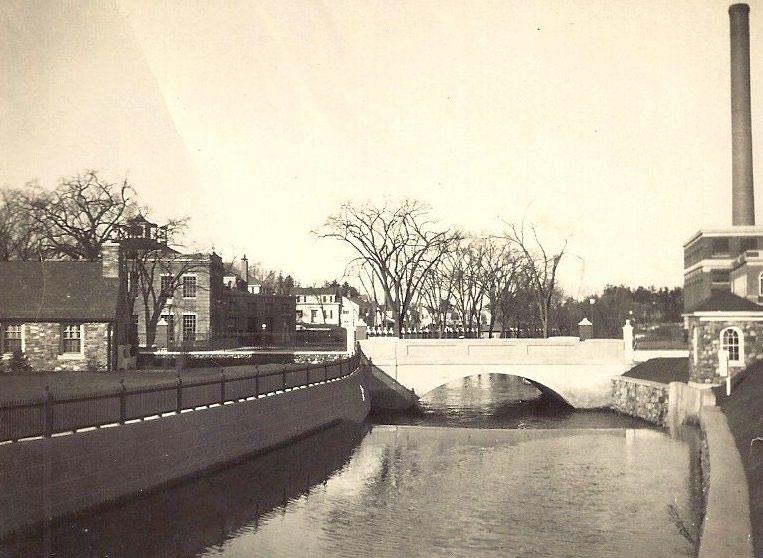

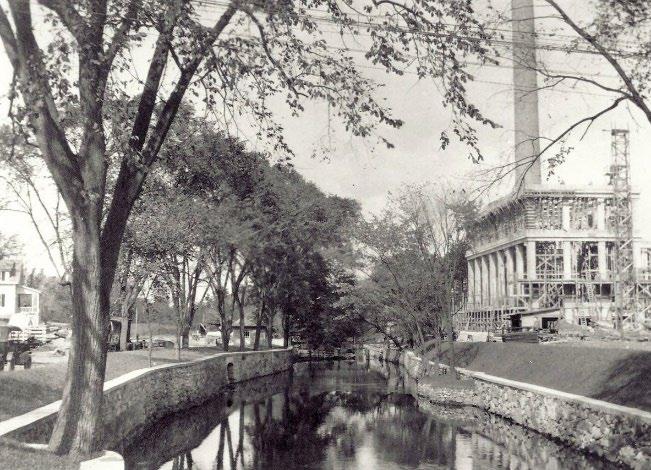

William Madison Wood became president of the company in 1899. Wood brought the American Woolen Company to Andover and transformed Frye Village into a planned corporate community that included company headquarters, factory buildings, homes, schools, services, and recreation. 79 To achieve his vision and create Shawsheen Village, starting in 1906, Wood began to buy properties throughout the village. Over the next 20 years, Wood purchased buildings and properties throughout Frye Village. He built new buildings and moved roads and homes. He also walled in the Shawsheen River as it flowed through the Village and had a canoe launch constructed at the Balmoral Spa Building and constructed an ornamental dam.

30 | Page

Shawsheen River boat landing, Shawsheen Village, ACHC #1995.009.1729

Ornamental dam, Shawsheen Village, ACHC #1992.285.68

79 Mofford, p184

To power his model village, Wood had a power plan constructed. The plant was coal-fired and drew water from the river to heat homes and commercial buildings throughout the village.

Wood’s experimental village was in its heyday from 1919 to 1924 when due to health issues and business problems, Wood was asked to resign his presidency of the Woolen Company. Two years later, in 1926, William Wood committed suicide near his home in Florida. 80 His successors moved the company headquarters back to Boston and New York. In 1931, the homes and commercial buildings were sold. The factories, however, continued to operate until 1957. 81

In 1984, the Shawsheen Village National Register District was formed to recognize and protect the character of the village.

80 Mofford, p183

81 Richardson, p91

31 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Construction of the Shawsheen Village power plant, ACHC #1992.10.01

Shawsheen River, ACHC #1992.85.64

Natural disasters

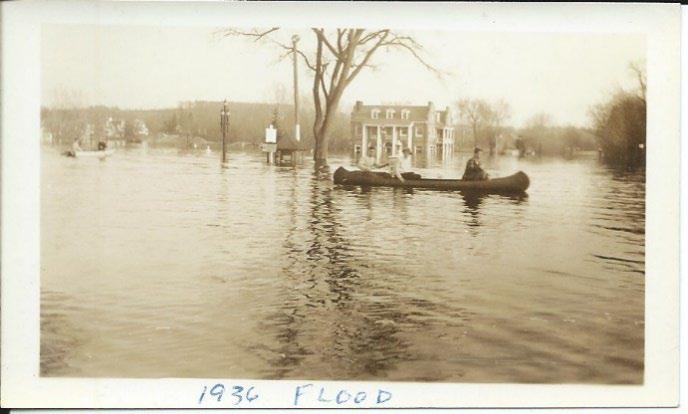

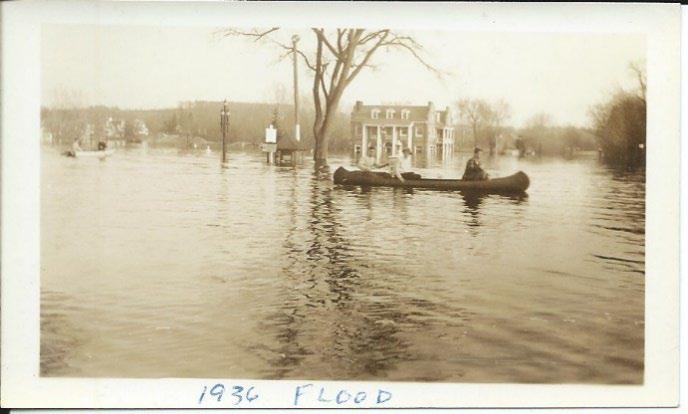

A number of notable floods hit the Shawsheen Village. The Flood of 1936 was a landmark event. An unusually warm spring that caused large amounts of ice to melt. At its peak, the flood waters backed up to the Redman Card Company at Dundee Park 5.5 miles away. Other floods followed in 1962 and 1968.

The impact of industrial waste in the 20th century Community use of the river changed, in part due to shifting interests, but also due to river pollution from centuries of industrial activities along the river.

As an example, in the 1950s, the Reichhold Chemical Company, which specialized in resins, operated in Lowell Junction. Hazardous waste was disposed of in unlined leaching ponds near the Shawsheen River until around 1972. As early as 1979, the presence of contaminants in the groundwater beneath the Reichhold property was documented. As the result of these findings, the state’s “brownfields” law allowed the property to be restored for limited uses. By 2004, 18,000 tons of contaminated soil had been removed with an additional 700 tons from beneath the building. By December, 2012, the site was finally considered “clean” by DEP. Town Meeting 2013 then approved additional monies for remaining Reichhold land. 82

By the 2001 Town Meeting, negotiations for the town’s purchase of the total 46.7 acre site – still not considered “clean” – were well underway. The Town Conservation Commission covered half the price tag in exchange for about 25 acres. The remaining acreage was to be designated as ball fields and sites for town storage, with Reichhold responsible for any remaining cleanup.

Conservation

In 1894, Andover residents formed the Andover Village Improvement Society (AVIS) as “part of a national movement toward the beautification and preservation of aspects of rural America.” 83 The group incorporated in 1896, during Andover’s 250th anniversary year. AVIS’ first order of business was the

32 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Shawsheen Village, flood of 1936, ACHC #1978.38.84

82 Ralston, Gail, Andover Townsman, Andover’s oldest industrial park at Lowell Junction, May 18, 2018 83 Mofford, AVIS, intro

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

saving of Indian Ridge. During the first half of the 20th century, AVIS focused mainly on beautification, improvements, and clean-ups. 84 In 1915, the group held its first clean-up week securing the “cooperation of Smith and Dove Co., of Stevens Mills in Marland Village, and some measure of help in Ballardvale.” 85

In the second half of the 20th century, under the leadership of Harold Rafton, Claus Dengler, Al Retelle, and others, AVIS began to acquire land throughout town. By 1980, AVIS had grown from 23 to 847 acres. 86

AVIS reservations near the Shawsheen River include:

1910, Lupine Reservation

1959, Sanborn Reservation

1960, Vale Reservation

1963, Shawsheen River Reservation

AVIS’s work was buoyed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ creation of the municipal conservation commission in 1957. “Sportsmen’s clubs, garden clubs, nature associations, and charitable foundations had done much to conserve our vanishing natural resources. But a specific municipal conservation agency and authorization of conservation as a valid municipal purpose were needed before communities could acquire lands for passive use.” 87

Andover’s Conservation Commission was formed in 19__. Today, the Commission oversees nineteen reservations including Serios’ Grove and Shawsheen Pines along the river in Lowell Junction.

Into the 21st century, other groups and commissions were formed to protect Andover’s natural resources, including the Shawsheen River. The Shawsheen River Greenway, Andover Trails, and the Shawsheen Watershed Environmental Action Team are examples of these groups.

84 IBID, p35-40

85 IBID, p65

86 IBID, intro

87 Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions website, https://www.maccweb.org/page/AboutConCommMA

33 | Page

PART 6: 2000s

Beginning in the 1990s into the 21st century, community uses of and attitudes toward the Shawsheen River shifted again as the community explored new ways to highlight and use the river. Conservation efforts, which started in the second half of the 20th century, increase. Clean-ups of the river are regular occurrences.

Starting in Lowell Junction, the Andover Conservation Commission created Serio’s Grove Conservation area in 2007. Evidence of Serio’s Grove included an old diving board. 88 In 200_ the 34-acre Pole Hill Reservation was created. 89

Recreational use of the Shawsheen River gained momentum in the 2000s. Organized by the Andover Recreation Department and Andover Trails, kayak and canoe storage racks were placed along the river south of Ballardvale in The Pines, at the end of Dale Street in Ballardvale, and near the intersection of Central Street and Abbot Bridge Drive.

In 2015, the Historic Mill District was formed, bringing new attention to the Shawsheen River in the heart of Andover’s historic industrial area. Reuse of the former Redman Card Building was greeted with enthusiasm by the community as the Oak & Iron Brewery opened along the river in 2017.

The old Marland Mill dam and the decorative dam in Shawsheen Village were removed in 2017. That same year, the Shawsheen River Greenway held its first herring count.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, I can do no better than to quote Denise Pouliot, the Sag8moskwa (Head Female Speaker) of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki. At a public forum held in Andover on September 22, 2022, she said,

“If you want to honor us, honor us by taking care of this place for the next seven generations, because that’s the gift of love we can give our grandchildren. That we thought enough about them today that we changed our ways and created a better society and environment on their behalf. That’s the legacy as Indigenous people that we strive for.” 90

88 https://andoverma.gov/997/Serios-Grove-Reservation

89 https://andoverma.gov/975/Pole-Hill-Reservation

90 Denise Pouliot, September 22, 2022, recorded on Andover TV

34 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Resources Pre-1646 and deep history

Bell, Edward, Persistence of Memories of Slavery and Emancipation in Historical Andover, Shawsheen Press, 2021

Strobel, Christoph, Native Americans of New England, Praeger, 2020

The Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki website, cowasuck.org/lifestyle/shelter

The University of Chicago Press Journals, journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1093/envhis/emx123

Resources 1646-1700

Alewife illustration, https://www.thecricket.com/news/the-alewives-cometh/article_02dbec58-978011eb-b375-7f236b29d932.html

Andover Historic Preservation website

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Riverside Press Cambridge, 1880 Colonial America’s Pre-Industrial Age of Wood and Water, https://www.engr.psu.edu/mtah/articles/colonial_wood_water.htm

Fuess, Claude, The Story of Essex County, Volume 1, Chapter 2, “Essex County in Indian Times,” American Historical Society, 1935

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/americanenvironmentalhistory/chapter/chapter-5-commons-millscorporations/

Lord, Philip, Mills on the Tsatsawassa: Techniques for Documenting Early 19th Century Water-Power Industry in Rural New York, Purple Mountain Press, Fleischmanns, New York, 1983.

Richardson, Eleanor Motley, Andover: A Century of Change 1896-1996, for the Andover Historical Society, 1995

Resources 1700s

Andover Historic Preservation website

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Riverside Press Cambridge, 1880 Mofford, Juliet, Andover, Massachusetts: Historical Selections from Four Centuries, Merrimack Valley Preservation Press, 2004

Witheridge: Fulling: http://www.witheridge-historical-archive.com/fulling.htm

Resources 1800s

Andover Historic Preservation website

Andover Townsman, Andover Stories: The Railroad Comes to Andover, Don Robb, December 2, 2021

Bailey, Sarah Loring, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts, Riverside Press Cambridge, 1880 Historic newspapers, MHL.org, Andover Advertiser and Andover Townsman

35 | Page

The Human History of the Shawsheen River, 1/12/2023

Mofford, Juliet Haines, Andover, Massachusetts: Historical Selections from Four Centuries, Merrimack Valley Preservation Press, 2004

Paavola, Jouni, Water Quality as Property: Industrial Water Pollution and Common Law in the 19th century United States, Environment and History, August 2002, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp295-318, White Horse Press.

The Mill Museum: Windham Textile and History Museum – The Mill Museum, https://millmuseum.org/swift-waters-the-industrial-environment/

Resources 1900s

Andover Center for History and Culture, History Buzz articles, Frye Village Stories: Degreasing plant comes to Andover, March 5, 2021

Andover Center for History and Culture, History Buzz article, Frye Village Stories: Taking a deep dive into General Degreasing, February 5, 2021

Andover Townsman, October 19, 2006, Bill Dalton

Andover Historic Preservation website

Batchelder, James, article in the research files of the Andover Center for History and Culture

Canoe Museum, https://canoemuseum.ca/2012-02-10-canoodling-with-st-valentine/

Mofford, Juliet Haines, AVIS: A History in Conservation, Andover Village Improvement Society, 1980

Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions website, https://www.maccweb.org/page/AboutConCommMA

Ralston, Gail, Andover Townsman, Andover’s oldest industrial park at Lowell Junction, May 18, 2018

Richardson, Eleanor Motley, Andover: A Century of Change 1896-1996, for the Andover Historical Society, 1995

Yale University, Energy History, https://energyhistory.yale.edu/units/rise-coal-19th-century-united-states

Resources 2000s

Andoverma.gov

Mofford, Juliet Haines, AVIS: A History in Conservation, Andover Village Improvement Society, 1980

Conclusion

Town Seal Review Committee, public forum, September 21, 2022, recorded by Andover TV and available online at https://cloud.castus.tv/vod/andover/video/632cb094f0f56f000980649e?page=HOME

36 | Page