Policies That Promote Women In Political Participation In Kenya

Published by:

Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) FAWE House, Chania Avenue, off Wood Avenue, Kilimani P.O. Box 21394 - Ngong Road, Nairobi 00505, Kenya.

Tel:

II WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

(254-020) 3873131/ 3873359 Fax: (254-020) 3874150

© This publication should not be reproduced for any purposes without prior written permission from FAWE. Parts of this publication may be copied for use in research, advocacy and education, provided that the source is acknowledged. FAWE cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies. ©Forum For African Women Educationalists (FAWE). 2021 This publication was copy edited and designed by: EKAR COMMUNICATIONS © Nairobi, Kenya W: www.ekarcommuncations.com E: info@ekarcommunications.com T: +254711409860

Email: fawe@fawe.org www.fawe.org Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This information was complemented by interviews conducted with a range of key stakeholders in Kenya and Tanzania, including Kenya’s senators, MPs – past and present, female governors and deputy governors, leaders of political parties, political analysts and influencers, representatives of bodies vested with responsibilities to oversee politics, and representatives of CSOs. In addition, the results of a situational analysis undertaken by FAWE to inform the WPP program in Kenya and Tanzania has also been referenced.3

The Women in Political Participation (WPP) Program team wishes to thank the resource partners (IDEA & Sweden Sverige) and implementing partners WLSA, Padare, Gender Link, FEMNET and IFAN for their support and cooperation during this exercise. We highly appreciate the FAWE Regional Secretariat leadership team led by Ms Martha Muhwezi, its Executive Director and Ms Teresa Omondi, its Deputy Executive Director, for their policy support and technical backstopping during this study. The Women in Political Participation (WPP) Program team wishes to thank the resource partners (IDEA & Sweden Sverige) and implementing partners WLSA, Padare, Gender Link, FEMNET and IFAN for their support and cooperation during this exercise.

We highly appreciate the FAWE Regional Secretariat leadership team led by Ms Martha Muhwezi, its Executive Director and Ms Teresa Omondi, its Deputy Executive Director, for their policy support and technical backstopping during this study.

Still at the Secretariat, we equally acknowledge the technical, administrative and logistical support provided by WPP coordination team during the entire exercise. To this end, special commendations go to Racheal Ouko, the Programme Officer at WPP, Lilian Bett, Joan Too, and Rose Atieno. We also wish to thank Kelvin Omwansa, Michael Onguss, Elsie Moraa, Emily Buyaki, Juliet Kimotho, and Julie Khamati for effective participation in the process. At the three levels, FAWE teams played their roles very well to ensure timely and successful completion of this work.

Appreciation goes to the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD), which FAWE contracted to support this process. The team that compiled the policy briefs comprised Winfred Lichuma, Mary Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, Damacrine Masira, and Raymond Kaswaga.

A

OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements IV Acronyms 7 1. Executive summary 8 POLICY BRIEF 1: CONTEXT AND REALITY OF WOMEN AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN KENYA 10 1. The Importance Of Context .................................................................. 10 2. The Realities Of Wpp ............................................................................ 11 3. The Role Of Political Parties 14 4. Recommendations ............................................................................... 16 POLICY BRIEF 2: THE ROLE OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER PARTNERSHIPS IN WOMEN ENGAGEMENT IN POLITICS IN KENYA 18 1. Typology Of Csos And Partners Engaged In Wpp ................................ 18 2. Different Roles Performed By Csos And Other Partners In Wpp 20 3. Gaps In Cso And Partner Support To Wpp ........................................... 21 5 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE IV WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

TABLE

AMWIK

Association of Media Women in Kenya

CEDAW Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

CMD Centre for Multiparty Democracy

CoK Constitution of Kenya

CREAW Centre for Rights Education and Awareness

CSO Civil Society Organisation

DfID Department for International Development

FIDA Federation of Women Lawyers

GBV Gender-Based Violence

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

IEBC Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission

KEWOPA Kenya Women Parliamentary Association

KEWOSA Kenya Women Senators Association

KHRC Kenya Human Rights Commission

KWPA Kenya Women Political Alliance

KWPC Kenya Women’s Political Caucus

NGEC National Gender and Equity Commission

ODM Orange Democratic Party

PPF Political Parties Fund

PWD People with Disabilities

SIDA Swedish Development Agency

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNFPA United Nations Development Fund for Women

WMNA Women Members of the National Assembly

WPAK Women’s Political Alliance of Kenya

A ACRONYMS POLICY BRIEF 3: THE POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON WOMEN AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN KENYA 24 1. Global And Regional Commitments Of Women’s Political Rights 24 2. The Constitution Of Kenya And Gender Equality...................................25 3. Promotion Of Political Rights And The Kenya Electoral System ...........26 4. The Electoral Process In Kenya ............................................................. 27 5. Legal Challenges Towards Implementing The Gender Equality Principle In Kenya .................................................................................................... 30 6. The Building Bridges Initiative (Bbi) ......................................................30 7. Key Policy Recommendations 31 POLICY BRIEF 4: WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION IN POLITICS: REGIONAL BEST PRACTICE 32 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................32 2. Best Practices And Key Indicators 33 3. Comparison Of Statistics In National Government ...............................36 3.1 Rwanda ................................................................................................ 36 3.2. South Africa ....................................................................................... 37 3.3. Namibia 37 3.4. Senegal ..............................................................................................38 4. Kenya And Tanzania In Comparison To The Best Practice ....................39 Kenya ........................................................................................................39 Tanzania 39 5. Policy Recommendations .................................................................... 40 General Recommendations ...................................................................... 40 Tanzania .................................................................................................... 42 Kenya ........................................................................................................ 42 References ............................................................................................... 43

7 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 6 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), in partnership with the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), is implementing a 3-year project (2021 – 2024) on Women

Participation in Politics (WPP) in eight countries, namely: Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eswatini, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. The project seeks to fulfil women's political rights in Africa in line with the Maputo Women Protocol of 2003 on the Rights of Women in Africa and other associate and sub-regional protocols and standards, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

FAWE recognizes that despite efforts made to enhance the participation of women in politics in most African countries, women continue to be underrepresented in political seats and spaces. To change this narrative, there is a need to raise and sustain awareness to shift the prevailing attitudes, examine obstacles, make reform proposals and empower identified champions for change while sharing comparative evidence that could propel action.

The first policy brief examines the context and realities of WPP in Kenya. 1The second policy brief examines the role of civil society organizations (CSOs) and other partners in WPP in Kenya. 2The information used for these compilations of briefs is based on literature reviews on WPP, interviews with a range of key stakeholders in Kenya, including senators, members of parliament (MPs), former and current female governors and deputy governors, leaders of political parties, political analysts and influencers, representatives of bodies vested with responsibilities to oversee politics (including Independent Boundaries and Electoral Commission (IEBC) and the Registrar of Political Parties), and representatives of CSOs. There was also crowdsourcing of views from about 30 women on their perceptions towards participation in elective politics. In addition, the results of a situational analysis undertaken by FAWE to inform the program planning and implementation has been drawn upon.

This Policy Brief was compiled by the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) which was contracted by FAWE to support this process. The team comprised Winfred Lichuma, Mary Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, DamacrineMasira and Raymond Kaswaga.

2 This Policy Brief was compiled by the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) which was contracted by FAWE to support this process. The team comprised Winfred Lichuma, Mary Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, DamacrineMasira and Raymond Kaswaga.

Kenya has a bicameral system where the legislature comprises the National Assembly, the Senate and 47 County Assemblies at the county level. This third policy brief is developed based on Kenya’s legal and policy framework. The information used in compiling the policy brief is from a desk review of the Kenyan legal framework for WPP. Further, the literature review is complemented with interviews from numerous stakeholders, including sitting and past MPs as well as senators, Kenyan citizens, institutions established to oversee elections and promote gender equality, including the State Department of Gender, National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC), the IEBC, the office of the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP) and the Kenya Law Reform Commission (KLRC). In addition, the results of a situational analysis undertaken by FAWE to inform the program has been drawn upon.

The last and final policy brief outlines best practices and case studies of WPP in four African countries: Rwanda, Namibia, South Africa, and Senegal. The selection of the countries was guided by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) ranking of women in national parliaments as per the January 2021 IPU report. The information used in compiling this brief is mainly from a desk review that examined the key parameters used to monitor and measure the best practices regarding WPP.

3 This Policy Brief was compiled by the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) which was contracted by FAWE to support this process. The team comprised Winfred Lichuma, Mary Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, Damacrine Masira and Raymond Kaswaga.

E

Ms. Martha R.L. Muhwezi

9 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 8 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Executive Director FAWE Africa

POLICY BRIEF 1:

CONTEXT AND REALITY OF WOMEN AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN KENYA

1. THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT

It is broadly acknowledged that the legal framework in Kenya is largely facilitative for WPP. The equality clause in the Constitution (2010)[1], affirmative action and the gender quotas, which are repeated in the chapter on representation in the Counties, National Assembly and the Senate, provide opportunities for women to participate in the political space.

The nomination seats to the Senate, National Assembly and County Assemblies have been used by political parties to bridge the gender gap, address inequality and can shape public opinion regarding the capacity of women to succeed in the political space. A political analyst interviewed for this assessment opined that: “They (nominations) provide a platform from which a woman can demonstrate leadership. For instance, Millie Odhiambo (MP) was nominated for one term and used the platform to showcase her leadership skills. She then competed against men and won.” In essence, women can use their current leadership positions (in all spheres and at all levels) to build their bases for electoral positions and succeed.

Regardless of the expanded normative commitments by Kenya, women’s political rights continue to be undermined by inadequate implementation, institutional barriers, discriminatory social norms, as well as by violence and intimidation [2]. These violations are indicative of the disconnect between policy and practice. Additionally, it is notable that the context for women in politics cannot be viewed devoid of the context in which they live.

• Politics should be viewed from the broader perspective of social construct Parliaments are mirrors of our societies responding to societal realities. Society is not favourable for women who aspire to engage in political decisionmaking. For instance, in some communities in the country, it is difficult for women to be at the helm due to cultural and religious factors since women’s role is considered peripheral in most patriarchal communities. Men are quick to say “hatuwezi tawaliwa na wanawake” (women cannot lead us).

• Women’s participation is affected by the type of politics in the country

Local politics tend to be masculine and chestthumping. For instance, the Aisha Jumwa (MP) versus Edwin Sifuna (Secretary-General, ODM in December 2020) war of words signalled this [3]. A critical look at the altercation suggests that Ms

Jumwa may have been trying to show that, ‘I have what it takes to be a leader in this country.’ In hindsight, a male political analyst opined: “Women need to know that they can engage differently. They do not need to emulate the male politicians to succeed.”

• WPP is contingent upon the communities to which the women belong Society still frowns at women for daring to challenge the status quo. Consequently, women are measured from a higher moral standard than men. A young woman who responded to a question on whether she would be willing to vie for a political office noted thus: “No because politics in Kenya is a very dirty game. You are doomed if you are not aligned to the 'right clique' at the 'right time'. Your integrity goes down the drain no matter how best you try to remain 'straight'. Politics is like patapotea (lottery). It is not for me or any member of my family. It is a no, no!”

• Lack of preparedness. Some women decide to run late for political office, which may be due to initial fear of the process and other social, financial and political considerations. Consequently, by the time they declare an interest, their opponents will have already gained ground. Furthermore, their late start does not allow them enough time to mobilize sufficient human and financial resources. Some go into politics without understanding the political loops they need to navigate to succeed.

• Inadequate political and civic education on what it takes to be a leader

Some of the women (and men) nominated find themselves in office without knowing what is expected of them. Several respondents noted that for such women (and men), they end up serving the interests of the person and/or party that nominated them rather than support and stand for the women’s cause. Further, some men have made it obvious that they will do everything to discourage women from succeeding in politics, especially if they (the women) appear to be struggling with their campaigns and/or leadership roles.

• The role of the media

The media tends to be a bit more critical when covering women candidates and leaders compared to men. Women candidates have reported in the past that they have received less media coverage than their male counterparts, and the lack of resources has compounded the problem. Gender stereotypes and stigma has been reported as being prevalent in the coverage of female political leaders. The application of double standards for men and women has resulted in female candidates being cautious when invited to participate in television or radio shows/discussions. And this has resulted in women shying away from media-based public discourse, which affects their visibility.

2. THE REALITIES OF WPP

There are three ways through which women find themselves in political offices: (i) competing for elective posts at the various levels and the various seats: Member of County Assembly (MCA), MP, Women Representative, Senator or Governor; (ii) reward by political parties for their services, such as participation in grassroots party activities and/or provision of technical services; and (iii) some of them find themselves in the position – being at the right place at the right time. For gubernatorial seats, the deputies are nominated by the candidate vying for election as County Governor and the nominee for this position is often declared when the nominating governor wins. Most male gubernatorial candidates opt for male running mates, compromising female candidates' positions.

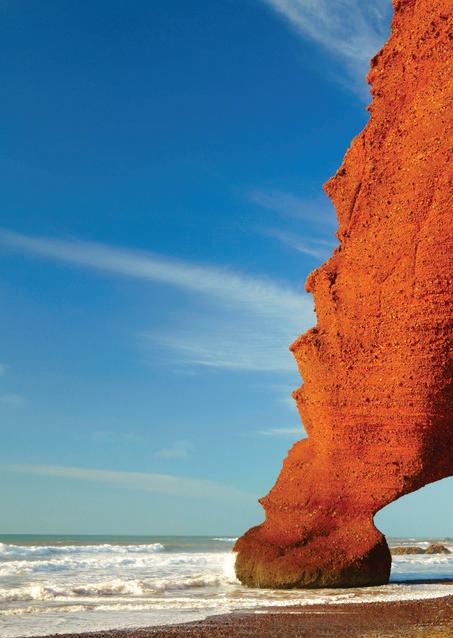

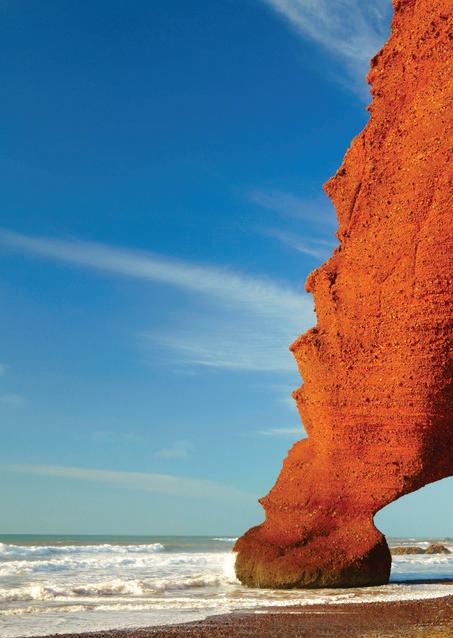

(Left to right) H.E. Adelina Mwau, Deputy Governor Makueni County; H.E. Dr Yulita Mitei, Deputy Governor Nandi County; H.E. Majala Mlaghui, Deputy Governor Taita-Taveta County and H.E. The Late Susan Kikwai.

1 11 WPP in

| By FAWE 10 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Photo credits: FAWE RS

Kenya

It is notable that some of the women who have held nominated posts have thereafter competed successfully and won elective posts. However, it is important to note that women in politics (as in real life) are not homogenous – they are stratified along with marital status (single, married, widowed, separated or divorced, etcetera.), age, religion, education level, ethnicity and political persuasion, etcetera. Their heterogeneity is not different from men, but these attributes are used against them when they decide and run for political office. It is more challenging for women with disabilities to vie for political office.

Discussions with women politicians, current and past, brought out the reality of their struggles to achieve and sustain their presence in the political arena. The following were cited as the key challenges that women face in politics.

Abuse of women in office

A Female Deputy Governor was addressing a meeting, when a man carrying a panty stood up and called her a prostitute. He told her to stop addressing the crowd and go pick her panty. She looked at him and told him that she had left many other items in his house including her petticoat and bra. He should bring all the items then she would go to collect them from him. She continued with her speech.

• Financial constraints.

All the assessment respondents agreed that it is expensive for a woman in Kenya to get into politics. The cost of political participation is too high for most women. A key informant observed: “Winning an election requires money – this is a system that is rigged. You need real money, and anything you touch and any action you take requires money.” An aspiring politician needs money to pay for the party ticket, remunerate her campaign team, brand herself, pay the youth who provide security during campaigns and incentivize voters. In some cases, men, who tend to have more networks and access to more resources, buy off the women’s agents and pay for smear campaigns to tarnish their names.

• Women have failed to systematize hand-holding. Some of the women leaders interviewed noted that it is lonely to aspire to political leadership or to be a leader in general. However, some exceptions were cited, including Hon. Charity Ngilu, who has mentored Hon. Cecily Mbarire, and Hon. Phoebe Asiyo, who is reported to have benefited greatly from the counsel of Hon. Grace Anyango. At the grassroots, fellow women become antagonists, and those who occupy political offices tend to become lone rangers. They do not propel each other (this may be due to other considerations, including clan, ethnicity, family, party affiliations, etcetera.). The general view is that women fight for themselves. One of the respondents noted: “It can get very lonely. You ask yourself why you are even bothering with the whole process. But you keep going since your commitment is to serve your community.”

At the operational level

After elections or nominations into the various political offices, women continue to face many other impediments to their effective participation.

• Fear.

It starts with the woman herself and her ability to reckon with the voter who is influenced by various factors, including gender, ethnicity, marital status, political affiliation, etcetera. Women sometimes feel inadequate, and the men aspirants take advantage of these feelings of inadequacy to dissuade them or harangue them from contesting. A respondent working with the Senate observed: “There is almost an unspoken rule/tendency that points to women’s participation as external tokenism rather than decisions based on their interests. They must wait to be invited to join the discussion rather than be the initiators of the discussion.”

• Multiple and complex loops. Women have to consider their family, social, and religious circumstances before they even grapple with the complexities of the financial and political party. They need permission from their spouses to vie for political office if they are married. Those who aren’t married may require affirmation from their male kin. In some cases, the men have had to go on the campaign trail introduce their wives and/or sisters for them to be allowed to address voters. However, there have been cases where women have successfully vied for political office while in their marital homes (e.g. Gladys Wanga, Women Representative) and in their natal homes (e.g. Late Dr Joyce Laboso, Governor, Bomet County).

• Hostility:

Parliament can be hostile against women even on the floor of the National Assembly. The heckling and ridicule by some men has made some women members of parliament and senators silent listeners. A respondent for this assessment noted watching women in the House over time, and it appears that: “Politics tends to take away rather than strengthen the women in office. Their reputation and standing in society often seem to diminish rather than flourish.”

• Discrimination:

Some of the rules discriminate against women. For instance, chairing committees in the Senate is a preserve of members who have been elected (not nominated). Consequently, since a large proportion of the women are nominated, this requirement limits their capacity to contribute equally to decision-making.

Violence and vulgarity.

During the 2017 elections, verbal abuse was reported to have been more frequent against women. Propaganda and negative campaigning about women’s sexual morality was common. Almost all women candidates reported that rival campaigns would attempt to undermine them through allegations of sexual misconduct. One of the male respondents to the assessment highlighted the difficulties women face when deciding to run: “A woman has to carefully plan how to go out on the campaign trail. The dress code includes tights inside, followed by jeans and then a dress on top because she never knows what will happen.”

• Limited access to resources: MPs have more funds than Women Representatives, who are expected to cater to entire counties' needs compared to constituencies.

1 2

3

13 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 12 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

3. THE ROLE OF POLITICAL PARTIES

The Political Parties Act, 2011 and as amended in 2016, contains provisions promoting political parties' diversity. Section 7 (2) (b) of the Act stipulates that among the conditions for registration of political parties is that their membership must reflect gender balance. Moreover, the governing body of a political party must conform to the principle that not more than two-thirds of the members should be of the same gender. According to section 21 (1) (a), parties that fail to comply with these provisions risk deregistration.

Political parties are instrumental in the recruitment, nomination and election of candidates for public office. The National Democratic Institute (NDI) and FIDA-Kenya conducted an analysis of the 2017 elections, which showed that 97 per cent of national assembly members came in through a political party, which is the vehicle to use for most politicians, including women [4]. The report shows that there was a high rate of interest in the Women Members of the National Assembly (WMNA) slots mainly due to the push and pull dynamics on women: parties push women to compete in the “women’s seats” to free up male candidates to compete in the other races (the lower gender discrimination and harassment in the women-only races may appeal to women candidates). The senate, gubernatorial, and presidential positions attracted the lowest number of women aspirants (1 per cent or less). Unfortunately, very few women go the ‘independent candidate route’ even when they feel illtreated by the political parties.

In recognition of the key role of political parties in ascension for both male and female aspirants into office, a CSO leader opined that: “The major obstacle to WPP is the way political parties are organized. They are owned and financed by individuals who have the final say. They have financial sponsors. The tickets are for sale to the highest bidder.”Political Parties tend to create barriers for women and occasion under performance on their representation function. The respondents' views and the literature review highlight the following aspects of political parties.

• Individuals and their cronies own parties. The owners and influencers of parties determine who vies, who gets the nomination certificate, and who gets nominated. A female leader noted: “In 2017, most women who won genuinely were rigged out by the party structure and by men.” She further opined: “Women need to understand what political parties are and move on when need be. Women tend to be loyal to political parties, but we see men move parties or become independent candidates swiftly when they realize their interests are not being served.”

• People overestimate the power of political parties to reign in members. It was noted that since candidates raise their funds for elections in the current set up of the First-Past-the-Post, they (aspirants) cannot be dictated on how to select their running mates or to leave the position to a woman. For instance, governors tend to feel that if they fund their campaigns, they should be allowed to determine their running mates. The party may provide guidance for consideration, e.g. for a person from the opposite gender as a running mate, but this cannot be obligatory. Most women deputy governors have leadership wrangles with their governors who do not include them in most decision-making.

• Political parties are hardly functional. Most political parties do not have functional structures that extend to the grassroots level (apart from ODM and Jubilee to a limited extent), while others only convene when there is a political message to be passed.

• Interests – personal and party. Some parties are seen as money minting systems, especially around elections. There have been reports of party hopping for people who miss nominations in their preferred party, so long as they can pay. However, voters are learning quickly. Political parties may choose to go a certain way, with a preference for specific individuals, but the voters have shown that they vote for their preferred candidates. Out of 1,259 women who ran for office in 2017, only 271 ran as independent candidates.

• Ineffective support for women aspirants. Despite all party manifestos (Jubilee, ODM, WIPER, NARC, etcetera.) having the provisions for supporting women aspirants, the commitment to actualize this beyond the manifestos is limited. Women leagues of most political parties, which could be instrumental for sensitizing and training women aspirants and voters to understand the value of participation, have not been fully supported. Leagues could be used to ‘raise women's consciousness at all levels. Women with disability face discrimination by political parties who fail to grant them tickets to vie on an equity basis. The consideration of special seats for women with disabilities has not been addressed effectively.

...Most women deputy governors have leadership wrangles with their governors who do not include them in most decision making...

15 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Political Parties tend to create barriers for women and occasion underperformance on their representation function.

What is the potential for WPP?

There is a high probability that if more women ran for political office, more would be elected. Evidence from 2013 and 2017 electoral results confirms this as illustrated below (note that the 2017 women seats exclude the women representative seats).

4. RECOMMENDATIONS

The FAWE Project seeks to support the successful and effective participation of WPP in Kenya. The Project would best serve Kenyan women by implementing the following key recommendations.

(i) Creation of impactful awareness on WPP. This should be done at the community level by addressing the key challenges highlighted here and the other policy briefs and study reports. Awareness will be achieved through fostering a holistic approach that cuts across state and community structures to counter the practices and perceptions that perpetuate discrimination against women. Although social, cultural and religious norms will take a long time to shift, the organization must support awareness activities by addressing these biases. This would entail:

o Understanding the context for each community since they are not homogenous;

o Packaging information in a manner that addresses and respects the social, cultural and religious norms of the communities;

o Amplifying the critical roles women have played in leadership by showcasing the best practices and use of local examples of women who have done well in leadership positions; and

o Paying special attention to women with special needs and providing channels for effectively engaging them in the political space.

(ii) Engage with political parties. Each political party of repute has a manifesto that makes provisions on women and their participation in politics. FAWE should analyse these manifestos, identify key action points and hold consultations with the parties on how to effectively implement these provisions. This analysis should be used to keep the parties accountable. The Katiba ruling delivered on 20th April 2017 requires political parties to restructure and facilitate more women to run in 2022, and FAWE can use this as a key accountability tool. The IEBC is obligated to use its powers of regulating political parties to ensure that they comply with the gender equality principle during nominations.

(iii) Enhance the skills of women political aspirants.

Partner with women leagues and caucuses to ensure that women aspiring to leadership are provided with the necessary skills to package their agenda, brand and effectively engage with the media. This intervention would address the key challenges of women emerging late and their ineffective positioning and visibility. FAWE could consider developing training manuals that could be shared with aspirants for the different seats at the different levels.

(iv) Support mentorship. There is a huge opportunity for older and seasoned female politicians to handhold younger and newer entrants into politics. FAWE could identify resources and facilitate sessions and activities to ensure lessons learnt by the luminaries (including mistakes, failures and successes) are used to inform and prepare the newer entrants for elections and leadership.

(v) Invest in a strong media component. Link with other partners working with the media to help shape public perceptions towards women in politics. This would help shift the narrative about WPP. People vote emotionally based on how the candidate is presented to them, and such an investment would be critical, especially if initiated early.

(vi) Address violence against women aspirants: There is a need for FAWE to include a focus on GBV in its WPP activities. The organization can accomplish this in partnership with other institutions that have been active in addressing GBV before and during elections, including the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC) and FIDA.

(vii) Creatively consider financing women aspirants:

Partner with other organizations to establish mechanisms to support women aspirants in generating campaign resources. Other support could go towards the campaign itself: media presence and branding; support through volunteerism; and legal representation if there is a contestation of election results.

(viii) Institutionalize gender equality: Political parties must eradicate gender inequality and barriers against women’s participation and representation. FAWE should partner with the political parties to develop gender equality tools required to establish a gender-responsive environment as a vital step towards inclusive politics. Deliberate efforts must be made to work with women with special needs, including women with disabilities and those from marginalized communities.

14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 11,720 13,242 971 1,259 Men 2013 Number of contestants Women 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 18.82 12.91 12.01 13.02 Men Success rate Women 2017 2013 2017 Source: A Gender Analysis of the 2017 Kenya General Elections. www.ndi.org.

REFERENCES [1]. The Constitution of Kenya http://kenyalaw.org:8181/exist/kenyalex/actview.xql?actid=Const2010 [2]. Bofu-Tawamba, 2015. Awake to the challenge: African women’s leadership at Beijing+20. https://www.uaf-africa.org/4073-2/ [3]. In December 2020, Aisha Jumwa had a war of words with the ODM Secretary-General (SG), Mr Edwin Sifuna of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) Party, on Msambweni by-election. [4]. A Gender Analysis of the 2017 Kenya General Elections. www.ndi.org. 17 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 16 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

POLICY BRIEF 2: THE ROLE OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER PARTNERSHIPS

(iii) Capacity building and training-oriented CSOs:

These organizations tend to focus on supporting women aspirants through training, skills transfer, exposure visits and mentorship. These CSOs include the Centre for Multiparty Democracy (CMD), Norwegian Democracy Institute (NDI), Kenya Women Holding, FIDA-Kenya, CREAW, CRAWN Trust, among others. The main aim for these CSOs is to ensure that women understand the political processes, the legislation and policies guiding their political parties, the role of the different government entities responsible for electoral processes, and their rights as a people.

(iv) Media and media associations: The media continuously shapes public views and defines events on the public sphere, the identities of those who access the public sphere and, to a great extent, the importance attached to events in the media [1]. In the last two national elections (2013 and 2017), several CSOs have focused on changing communities' perceptions towards women in leadership, including the Association of Media Women in Kenya (AMWIK).

IN

WOMEN ENGAGEMENT

IN

POLITICS IN KENYA

1. TYPOLOGY OF CSOS AND PARTNERS ENGAGED IN WPP

There are different types and formations of CSOs involved in WPP in Kenya. Some operate at the global and regional levels, and others have a more national focus, while others are found active at the grassroots levels. The persuasions, ethos and modes of operation defer based on their objectives, leanings and level of funding. CSOs roles include promoting, respecting and upholding human rights and social justice through empowering people to voice their concerns. CSOs work across all aspects of WPP, including legal and policy reforms, advocacy, leadership, capacity building, media engagement, monitoring and accountability, as described below.

(i)Rights-based organizations: Inclusion of women in political leadership and decision making is not only a prerequisite for a functional democracy but is also a matter of efficiency in governance. CSOs are very active in promoting women’s rights, thus working towards increasing women in political leadership. Several organizations have consistently focused on the rights approach to politics, specifically for WPP. These organizations are involved in legal and policy review (as described further below) and monitoring contravention of women’s rights in the political sphere. These organizations have been central in building the women’s movement, advocating for women’s rights and promoting gender-related actions, including seeking the court’s interpretation on the not more than two-thirds gender rule. Some of the most active CSOs in this area include the Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA-Kenya), Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), CRAWN Trust, Katiba Institute and the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW).

(ii) Capacity building and training-oriented CSOs: These organizations tend to focus on supporting women aspirants through training, skills transfer, exposure visits and mentorship. These CSOs include the Centre for Multiparty Democracy (CMD), Norwegian Democracy Institute (NDI), Kenya Women Holding, FIDA-Kenya, CREAW, CRAWN Trust, among others. The main aim for these CSOs is to ensure that women understand the political processes, the legislation and policies guiding their political parties, the role of the different Government entities responsible for electoral processes, and their rights as a people.

It is, however, notable that the media has often described successful women politicians in masculine terms, as evidenced by a statement about a former Minister for Justice, Hon. Martha Karua as being “the only man in the former President Kibaki’s government.” These might appear positive at a cursory glance, but it is an unwarranted comparison in a context created and perpetuated by the community and given legitimacy through the media.

(v) Parliamentary Caucuses: The Kenya Women Parliamentary Association (KEWOPA), Kenya Women Senators Association (KEWOSA) and the County Assemblies Women Caucuses are legislators’ membership associations whose aim is to strengthen the participation of women in all political spheres through capacity development, partnership building and strategic community engagement. There are also alliances, such as the Kenya Women’s Political Caucus (KWPC), Women’s Political Alliance of Kenya (WPAK) and Kenya Women Political Alliance (KWPA), that tend to gravitate towards capacity building through developing the knowledge and skills to help women political aspirants to win candidate nominations and elections, and ultimately to promote and support women’s participation and influence in politics.4

(vi) The UN system and development partners: These institutions are recognized for supporting CSOs, women alliances and caucuses in Kenya to engage in WPP actively. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP), United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNFPA) and UN Women have consistently supported the WPP CSO initiatives and movements for over 20 years. This support has mainly focused on identifying, training and positioning women to take on leadership positions at the local and national levels. The Swedish Development Agency (SIDA), Department for International Development (DfID) and Ford Foundation have been consistent in their support for WPP.

June 15, 2019

IDEA has illustrated its commitment to addressing the challenges of WPP through various targeted support, particularly through funding the FAWE Project.

It is, however, notable that, like all other institutions and agencies involved in WPP, CSOs have not been spared the politics at the national and community levels, and this is not likely to change soon.

Although it is assumed that the CSOs and partners operate from political neutrality, there are indications that this is not always the case. Their engagement in politics is shaped by the political aspirations and leanings of the CSO leadership and the primary funder. Further, it is important to acknowledge that CSOs are an extension of society – the leadership of some CSOs may not share the values of the extension of women in politics equally. 4

down

2 19 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 18 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Notably, some of the alliances have since closed

due to a lack of resources.

2. DIFFERENT ROLES PERFORMED BY CSOs AND OTHER PARTNERS IN WPP

Armed with international and regional instruments and frameworks for advancing the cause of gender parity, CSOs have been instrumental in causing major shifts in the country on awareness about women’s rights and their entry into the public arena as political actors, with their voice and presence. For the most recent national elections in Kenya (2017), CSOs provided technical assistance to women candidates, created hotlines for women to report violence, and worked with political parties, the IEBC, and other institutions to help women gain leadership positions [2].

Below is a brief description of the key areas of work that CSOs have undertaken to support WPP in the country, including advocacy, legal and policy reforms, financial support to women aspirants, training and skills transfer, and monitoring and oversight over elections.

(i) Advocacy:

Many organizations have been engaged in community awareness activities in various counties across the country to change the negative perceptions of women in leadership and increase support for women candidates. In 2017, social media campaigns such as #NiMama, #ChaguaDada JengaNchi, #BetterThanThis, and the work of groups such as Tuvuke made important contributions to improving media coverage and raising awareness around women in politics. Some organizations held dialogue sessions that brought together women, community elders, and opinion leaders to look for ways to support women in their campaigns [2].

(ii) Legal and policy reforms:

A respondent during the assessment opined: “Give it (CSOs) credit for driving the agenda of equality and inclusivity. The CSOs are currently active in discussing the changes in gender provisions in the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI). For example, FIDA, CREAW and others have continuously challenged the Government even in court.”

(iii) Financial support to women aspirants: One of the key challenges facing women aspirants is the limited financial base they operate from. Men tend to have more networks and seem to mobilize resources more easily. A respondent reported a case in which an aspiring woman MCA sold a cow to generate funds for her campaign, but her husband divorced her when she lost. There have been efforts by some CSOs to support women directly through providing financing. However, given the lack of equity and sustainability of such interventions, there is a need to find different ways to support women candidates in a more meaningful and feasible manner.

(iv) Training and skills transfer: Several CSOs offer women aspirants and candidates training to enhance their knowledge and capacity to effectively compete, both in their party primaries and in general elections. Some programs target the grassroots level women, including the SIDA funded capacity building program that in 2017 helped identify, train and equip women aspirants with knowledge on elections and equipped them with media engagement skills.

(v) Monitoring and election oversight: CSOs start monitoring events around elections as soon as the electioneering period kicks off, through the voting process to the installation of elected officials. CSOs, such as Kenya Human Rights Commission, FIDA-Kenya, Katiba Institute, and CREAW, have been at the forefront of calling out political parties and the Government over election malpractices that have disenfranchised political parties aspirants, especially women. Formal petitions by women who feel unfairly treated by their parties and/or the electoral bodies have been launched, some successfully by CSOs.based on their program plans rather than the electorate’s needs. Some Tanzanian CSOs, funded by Northern donors, have been criticised for being more accountable to their donor agencies than the people they serve [4]. The respondents to this assessment opined that all partners should be responsive and address the contextual and actual needs of the women and communities they intend to support rather than impose their programmatic requirements.

3. GAPS IN CSO AND PARTNER SUPPORT TO WPP

(i) Limited coordination:

This is a key challenge for CSOs while implementing WPP activities, leading in some cases to duplication of activities and inadequate use of the meagre resources in the sector. A respondent noted that “CSOs tend to be reactive and unrealistic”, meaning they do not take time to plan, strategize and build alliances. Although it is critical for the mobilization for women who run for office to start early, the CSOs tend "to wait for the women to inform them that they are running for office for them to start working with them. Sometimes this is too late in the day to render effective and winnable support.” Further, it was observed by the respondents that there has been no concrete relationship between women in power and women in CSO leadership, yet such a relationship could proffer gains for the aspirants, including skills and networking linkages.

(ii) Limited resources:

Many CSOs compete for the same resources in an environment where funding for WPP (similar to funding for other CSO activities) has dwindled. This limitation in resources has led to the collapse or near-collapse of well-meaning CSOs keen on working with women, especially those at the grassroots, to join and be active in politics. The key question remains how many development partners are willing to give money to women and shape them to go a particular way that may not be aligned with the male-driven decision-making.

(iii) Challenges of channelling support:

There was a broad-based view among the assessment respondents that the UN, especially the UN Women, has been politicized. One respondent noted: “The UN Women is now operating as a local NGO engaging in local politics. It has a financial allocation for supporting women in politics, but it decides who gets the money.” One opined, “When UN forms political systems that kill women political movements.” This is an issue that requires further assessment and redress.

Some CSOs are considered to be selective in their support for WPP. Their decisions tend not to be demanddriven but based on their program plans rather than the electorate's needs. The respondents to this assessment opined that all partners should be responsive and address the contextual and actual needs of the women and communities they intend to support rather than impose their programmatic requirements.

(iv) The politicization of civil society: CSOs continue to struggle due to alignment (real or assumed) to particular political persuasions and individual leaders. It is sometimes not easy to differentiate between some political parties and CSOs. This reputational risk has harmed their ability to remain competitive in resource mobilization and in persuading the masses whose voting habits they intend to influence.

(v) Monetization of political processes: Like everything else in Kenyan society, politics is perceived and approached as a money-making machine. The electorate, the agents, parties and individual aspirants approach the whole process as a way to generate an income – ‘to reap from (or milk) the system”. It was observed by a CSO respondent that “Women sometimes do not value the support provided by CSOs especially if the support is not monetary.”

(vi) The short-term view of WPP:

Activities on WPP tend to pick up close to elections and fizzle out soon after. To develop a strong movement for WPP, there is a need for long-term investment in the communities (e.g. to address socio-cultural and religious perceptions) and in the women aspirants, who sometimes join the political races too late in the day.

21 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 20 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

...“Women sometimes do not value the support provided by CSOs especially if the support is not monetary.”...

4.RECOMMENDATIONS

The CSO initiatives, including the FAWE project, are important to all aspects and stages of WPP – from nurturing the desire for women to run for political office to running a successful election campaign and ultimately performing the leadership role once elected. The assessment for this policy brief has illustrated the critical ways through which the CSOs have supported WPP in Kenya and the gaps that still exist. Notably, WPP and CSOs operate in the real world, whose outlook is driven by the prevailing social, economic and political interests with implications on all spheres of life. As women’s political interests increase, so does the need for tangible, meaningful and long-term support to WPP. Below are some key recommendations for FAWE and other CSOs supporting WPP.

(i) Take advantage of the intellectual space: The CSOs (including caucuses and development partners supporting WPP) should compete in the marketplace of ideas. For instance, FAWE could work with partners to organise regular meetings to develop a common agenda for WPP in the country. In addition, instead of giving direct support to aspirants, CSOs and development partners should focus on the electorate – the people that tend to perceive WPP negatively. They could, for instance, focus on providing civic education with a consistent message that ‘women are nurturers, good leaders, resilient and forward-looking’.

(ii) Innovative financing strategy:

Collectively work with partners to develop a campaign fund for women with clear, accountable and equitable support criteria. To ensure the viability of this fund, the women in politics should own the processes and the measures put in place to safeguard the fund. There would need to be a clear plan to ensure the fund's sustainability. The Kenya Women Holding, which is developing such a fund, could be a key partner.

(iii) Partner with political parties: Although political parties have their challenges, they are still the key vehicles women use to ascend into political office. FAWE and other CSOs should petition the parties to dedicate resources for women candidates and give women concessions and/or implement the concessions provided for in their manifestos. FAWE and other CSOs should monitor the Political Parties Fund (PPF) to ensure fair and equitable allocation to women candidates. There needs to be a focus on support to women with disabilities and those from marginalized communities.

(iv) Democratize and institutionalize engagement with the media: FAWE could liaise with Parliament (National Assembly, the Senate, and County Assemblies), Media Council, AMWIK, the Editors Guild and other CSOs to develop content for training women political leaders on the role of the media. This would ensure that women politicians understand how to weave their agendas around the operations of the media. Media houses could be helped to develop specific policy guidelines on gender-sensitive language, especially when covering women politicians. There should be continuous training of journalists on the role of women as political leaders so that they can promote the role of women in leadership. This training could also extend to understanding the vulnerability of women with disabilities and how to render meaningful support as aspirants and parliamentarians.

(v) Document the needs of WPP and provide targeted support:

The current approach of some CSOs and partners developing and funding programs without contextualizing the needs of the voters and women politicians needs urgent redress. An assessment of the needs and requirements of the different leaders and communities should be conducted to inform the agenda for WPP. There is a repertoire of secondary data online that could be augmented with targeted assessments (including the situational analysis undertaken by FAWE) to set the agenda for WPP.

REFERENCES [1]. Mwathi, M. W. (2017) Perceptions of Female Legislators in the 11th Parliament on Media Portrayal of Women Politicians in Kenya. The University of Nairobi. [2]. A Gender Analysis of the 2017 Kenya General Elections. www.ndi.org. 23 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 22 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

POLICY BRIEF 3: THE POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK

ON WOMEN AND POLITICAL

PARTICIPATION IN KENYA

1. GLOBAL AND REGIONAL COMMITMENTS OF WOMEN’S POLITICAL RIGHTS

Representation of women in politics around the world has grown from the global efforts towards the empowerment of women and enhancing their participation in governance and leadership spaces.

The United Nations Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) defines discrimination against women and asks State Parties to strive to eliminate this vice in all spheres. It notes thus:

Kenya has ratified numerous international treaties that promote gender equality in political representation. These include the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICCPR) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCPRD). The UNCPRD underscores equal rights for people with disabilities (PWDs) to participate in political life. The majority of people (men and women) with disabilities are not enabled to vote by the State. However, it is notable that PWDs are not homogenous and represent different categories of disabilities, including the physical, mental, and hearing impaired.

At the African level, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on women's rights in Africa (the Maputo Protocol), 2003, obligates states to eliminate discrimination against women through appropriate, legislative, institutional and other measures. States are called upon to take positive actions, including special measures to promote the right of women to participate in political and decision-making processes. The Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa (2004) reaffirms the state’s commitment to gender equality and accelerate the ratification of the Maputo Protocol. At the sub-regional level, the East African Community Treaty emphasizes on adherence to good governance, democracy, the rule of law, observance of human rights and social justice. Kenya has not ratified the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance of 2004 that seeks, among other things, to promote gender balance and equality in governance and development process, including holding free and fair democratic elections in Africa.

Once a state ratifies any international, regional or sub-regional treaty, the expectation is to domesticate the same, making it enforceable at the local (domestic) level.

Discrimination against women is defined as distinction, exclusion or restriction made on impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, based on equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

CEDAW calls on States to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the political and public life of the country on equal terms with men and specifically to enable women: (a) to vote in all elections and public referenda and to be eligible for election to all publicly elected bodies; (b) to participate in the formulation of government policy, and (c) to participate in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and associations concerned with public and political life. The 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action is a roadmap that set a critical mass for women representation at 30 per cent as a means of achieving gender equality.

2. THE CONSTITUTION OF KENYA AND GENDER EQUALITY

Kenya has ratified numerous international and regional treaties touching on WPP and leadership. These include: (i) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) assented on 23/3/1976; (ii) CEDAW ratified on 9/3/1984; (iii) the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights ratified on 12/12/2003; and (iv) the Protocol to the African Charter on Rights of Women in Africa that was ratified in 2010.

Kenya has put in place electoral laws, rules and regulations, election-monitoring bodies and regulations of political parties to ensure fair, free and credible elections. To accelerate the increase of women in Parliament, the Constitution of Kenya (2010) promotes legislated quotas. Apart from promoting and protecting the political rights of men and women, the CoK 2010 also promotes women’s rights to land, marriage, public participation, inheritance and economic, social and cultural rights. The CoK is well known for its gender equality principle popularly referred to as the …'not more than two-thirds' gender rule.

3

Participants of the WPP situational analysis and policy brief validation meeting pose for a photo at Safari Park Hotel, Nairobi.

Photo credit: FAWE RS/ Emily Buyaki

25 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 24 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

The State is expected to give full effect to the two-thirds gender rule principle through legislative and other measures, including affirmative action, progress and policies that are designed to redress any disadvantage suffered by individuals or groups because of past discrimination (Article 27 (6) (8) of CoK 2010). The CoK provides for how the gender principle is to be realized in the National Assembly and the Senate (Articles 97 and 98 and at the local level – the County Assemblies (Article 177 of the CoK). The general principles for the electoral system include the realization of … not more than two-thirds gender rule (Article 81(b) of CoK).

Article 54(2) of CoK 2010 obligates the State to ensure that at least 5 per cent of PWDs are included in elective and appointive bodies. The PWDs need to be empowered to participate in politics, especially women.

Further, Article 100 of CoK anticipates that parliament will enact legislation to promote the representation of marginalized groups, including women, persons with disabilities, youth, ethnic minorities and marginalized communities. This law is not yet enacted. Thus making the representation of the mentioned categories uncoordinated. The CoK, Article 38 states that every citizen has the right to be involved in political matters. The persons with disabilities Act 2003 in Section 29 specifies that people with disabilities have the right to vote and may be assisted by a personal assistant whose duty is to follow their instructions in voting. On the contrary, Article 99(e) of the Constitution and the Elections Act restricts persons of unsound mind from voting.

The provisions exclude persons with intellectual disabilities to participate in politics.There are, however, reserved seats for PWDs in National Assembly (97(1)

(c), Senate 98 (i) (d) and at the County Assembly (Article 177 (i) (c). PWDs (men, women and youth) have the right to be treated with dignity and respect, among others. They are entitled to use sign language, braille or other appropriate means of communication. The state is expected to ensure the progressive implementation of the principle that at least (5) five per cent of the members of the public in elective and appointive bodies are PWDs S4 (2) of the constitution. The reality is that political parties have continued to exclude PWDs in active politics.

3. PROMOTION OF POLITICAL RIGHTS AND THE KENYA ELECTORAL SYSTEM

The CoK 2010 largely promotes political rights for men and women (See Articles 34, 35, 36 and 38). Expressly, all citizens have the right to:

i. Participate in forming political parties;

ii. Participate in activities of recruitment of members of political parties;

iii. Campaign for a political party;

iv. Free, fair and regular elections based on Universal Suffrage;

v. To be registered as a voter without unreasonable restrictions;

vi. To vote by secret ballot without restrictions; and

vii. Without unreasonable restrictions, to be a candidate for public office within a political party if a member.

Kenya has maintained the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) System, sometimes called the single-member plurality voting or majority electoral system. In this system, inherited from the British, the voters cast their votes for a candidate of their choice and the candidate who receives the most votes is declared the winner.

The CoK 2010 introduced proportional representation (PR) alongside the FPTP for the special seats, i.e. nomination in Parliament (National Assembly and Senate) and in the County Assemblies.

In Kenya, FPTP is used in all single-member constituencies, i.e. 290 constituencies, 47 counties and 1,450 county wards. IEBC uses the PR to determine special seats allocated to political parties proportional to the total number of seats won by candidates of the political party at the general election (Articles 90, (1) (2) and (3) of CoK). The specifications on the number of the seats are provided for in Article 97(1) (c) – National Assembly, Article 98 (b) (c) (d) – the Senate and Article 177 (b) and (c) – Members of County Assembly (MCA). The FPTP system allows voters to choose between individuals rather than parties, thereby giving a chance to a popular candidate to win. The system is also simple to use. However, the FPTP system has not been known anywhere in the world to promote and increase the number of women in Parliament. Its implementation normally excludes small parties and women specifically, who opt to run under small parties. Bigger parties normally attract men who are preferred candidates within communities and are assumed to have higher potential to win the party than women candidates.

The key informants, mainly women, interviewed for the assessment conducted for the production of this brief, had many misgivings about the FPTP. Respondents referred to social and cultural barriers as a hindrance to WPP. Due to male-dominated political party structures, the preferred candidates are usually male instead of women. Political parties fear losing their strongholds to women if contesting against strong men. A majority of former women MPs proposed that Kenya adopt the PR system fully, like in the case of Rwanda or South Africa.

There exist legal barriers as well. The study revealed that the introduction of constitutional guarantees on special seats for women, PWDs and the youth was progressive and aimed to support an increase of the special groups into political leadership. However, it has, on the other hand, compromised women’s chances to get party tickets to vie in political party’s strongholds. Parties have used the trade-off system to circumvent the legal provisions and promised women nominations (special seats as per Article 90 of CoK 2010) and urge women to step down for men in the constituency, county and/or ward-based seats.

4. THE ELECTORAL PROCESS IN KENYA

The full cycle of the electoral process in Kenya is guided by the CoK 2010. It stems from the legislation and policy framework on voter registration, candidates

presenting themselves to an election, eligibility to be in a political party or to be an independent candidate, voting and determining electoral disputes.

This policy brief concisely discusses each law, its merits and demerits in enhancing WPP. It also outlines the legal barriers that key informants pointed out as hindrance to women enjoying their political rights and provides recommendations towards strengthening WPP using the legal framework.

The CoK 2010 calls on the electoral system to comply with the not more than two-thirds gender rule in elective public bodies and also fair representation of PWDs (Article 81(b) (c) and (e). Further, every citizen is free to make political choices that include:

i. to form or participate in a political party; ii. to participate in the activities of, or recruit members for a political party; iii. to campaign for a political party or cause; and iv. a right to free, fair and regular elections based on Universal Suffrage.

Currently, the … not more than two-thirds gender rule…. has no enforceable framework for implementation in parliament. The search for the gender equality principle has been a subject of numerous cases filed mainly by CSOs in the High Court Of Kenya. The courts have found that the executive and the legislature have violated the constitutional principles by not providing a legislative framework. This culminated into an advisory, dated 22nd September 2020, by the Chief Justice Emeritus, David Maraga, to His Excellency the President to dissolve Parliament. Despite the constitutional provisions supporting the process, there has been no response to date. It is clear that the legal framework can only achieve the intended results if fully implemented. This culminated into an advisory, dated 22nd September 2020, by the Chief Justice Emeritus, David Maraga, to His Excellency the President to dissolve Parliament. Despite the constitutional provisions supporting the process, there has been no response to date. It is clear that the legal framework can only achieve the intended results if fully implemented.

Kenya has maintained the First-Past-ThePost (FPTP) System, sometimes called the single-member plurality voting or majority electoral system.

VOTE

27 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE 26 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Below is a brief review of the election enabling legislation that should promote the enhancement of WPP.

a) The Elections Act 2012 and amended in 2017

The Elections Act 2012 provides for the conduct of elections to the Office of the President, the National Assembly, the Senate, County Governor and County Assembly. It also provides for the conduct of referenda election dispute resolution, among others. During this review, it was notable in engagement with women that the majority were unfamiliar with election timelines as provided within the law.

b) The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Act (IEBC) 2011

The IEBC is the election management body (EMB) in Kenya’s electoral system. It is created under Article 88 of CoK 2010, and its functions and mandates as an independent body are provided for in Chapter 15 of the CoK. The Act provides for the structure and roles of the commission in discharging its constitutional mandate. In discharging its functions, the IEBC is bound by the constitutional gender equality principles. The chairperson and the deputy must be of the opposite gender in its leadership. It was noted that IEBC has not put in place any gender-specific regulations to guide the process undertaken by political parties towards the realisation of the not more than two-thirds gender rule. In the case of Katiba v. IEBC of 2017, the court decision noted that it was the responsibility of IEBC to enforce the requirement to meet the gender parity rule.

e) Political Parties Act 2011

The Political Parties Act, 2011 and the 2016 amendments draw their mandate from the CoK 2010 (Article 91). The Constitution stipulates the basic requirements for political parties. Political parties are expected to have a national character and a democratically elected governing body. The party must promote and uphold national will, respect and promote human rights, fundamental freedoms, and gender equality and equity. It also must promote the objects and principles of the Constitution, among others.

The gender parity requirement of political parties is that the party’s governing body must reflect diversity and gender balance and respect the not more than two-thirds gender rule in the party’s governing body. The Act establishes the Independent Office of the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP), Political Parties Liaison Committee (PPLC) and the Political Parties Fund (PPF). Political parties are also authorized to create coalitions and mergers. For a political party to qualify to benefit from the PPF, it must have attained at least 5 per cent of the total national votes cast in the preceding general elections.

Further, not more than two-thirds of its registered office bearers should be of the same gender. The ORPP has simplified all the requirements in a checklist for political parties to comply. However, the ORPP does not readily have the gender analysis of the party’s gender balance and the utilization of the resources for the two parties that received the fund.

The 2016 amendments to the Political Parties Act provide clarity by defining special interest groups to include women, PWDs, youth, ethnic minorities and marginalized groups. The Act amends reference to minorities and marginalized groups to special interest groups whose essence is to recognize women in that category. Political parties are required to disaggregate their membership based on special interest groups. Further, the Act was amended to ensure that…. no more than two-thirds gender principle is met in all party organs, bodies and committees. While the legal framework regulating political parties is clear, it may be important to scrutinise political parties, especially those receiving public funds.

c) The Election Offences Act (2016)

Women observed that gender-based violence (GBV) is a great barrier to women during campaigns. It identifies common election offences and prescribes penalties to be meted upon offenders found culpable. The Act provides for the offence of undue influence among other offences, including using threats, threatening to use any force and violence including sexual violence, restraint or material, physical or spiritual injury, and harmful cultural practices (Section 10). While the offence of use of undue influence includes sexual violence, there is a need to amend the law to define the offence of GBV and link it to the Sexual Offences Act, which has stiffer penalties as opposed to the Elections Act. The elections code of conduct, which has been included in the Elections Act, does not include the prevention of GBV as a duty required of the political parties and the candidates. This is a great omission.

d) The Persons with Disabilities Act

The Persons with Disabilities Act of 2003 guarantees PWDs civil rights to vote and provides that polling stations shall be made accessible during elections. In addition, PWDs should be provided with the necessary assistive devices and services to facilitate their voting. This has not been fully embraced by the electoral management body occasioning challenges to PWDs as candidates as well as voters.

Negative myths and stigma about PWDs are common and work to exclude them from leadership, especially political leadership. The challenges PWDs face cumulatively include lack of support system, e.g. those who require braille or assistance to vote, an unfriendly environment that is physically inaccessible and limits the mobility for those physically challenged. CPRD obligates states to remove all barriers that deny PWDs political rights. Despite the legal provisions promoting PWDs and their rights to vote, the political system is still greatly discriminatory towards them.

Essentially, 15 per cent of the PPF must go to support gender activities. These funds are intended to enhance the electorate to engage better with the parties. While the ORPP indicated that the two parties receiving the PPF (Jubilee and ODM) have used some of the resources towards activities of the women leagues, the evidence was not available to support this assertion. There is a need to review the eligibility criteria of political parties to facilitate more parties to access the PPF.

f) Policy Framework

To strengthen the legal framework towards elections, IEBC developed numerous regulations in 2017. These include Election (Technology) Regulation, 2017; Election (Voter Registration), Regulations 2017; Elections (General Regulations, 2017); Elections (Voter Education) Regulations, 2017; Elections (Party Primaries and Party Lists) Regulations 2017; Rules and Procedures on Settlement of Disputes, 2012; Elections (Parliamentary and County Election) Petition Rules and the Supreme Court (Presidential Election Petition Rules, 2017). The regulations are facilitative for men and women. However, the IEBC has not put in place any regulations to guide the process by political parties’ nomination of candidate’s that would facilitate the realization of the gender principle. IEBC needs to have clear regulations towards implementing the principle of gender equality and inclusion by political parties.

Deputy Governor Taita-Taveta County, H.E. Majala Mlaghui addresses the audience at the launch of the WPP Intergenerational Mentorship Programme on 8th March 2021

Photo credit: FAWE RS

Deputy Governor Taita-Taveta County, H.E. Majala Mlaghui addresses the audience at the launch of the WPP Intergenerational Mentorship Programme on 8th March 2021

Photo credit: FAWE RS

29 WPP in

| By FAWE 28 WPP in Kenya | By FAWE

Kenya

5. LEGAL CHALLENGES TOWARDS IMPLEMENTING THE GENDER EQUALITY PRINCIPLE IN KENYA

i. Article 100 of the CoK requires Parliament to enact legislation to promote the representation of women, PWDs, youth, and marginalized and ethnic minorities. This law has not been enacted. The two-thirds gender framework remains unimplemented.

ii. IEBC has a role in undertaking voter and civic education. The legal and policy framework ensures a conducive environment for all voters (men and women) to participate. However, many respondents noted that most Kenyans are not reached with relevant information on elections and how to vote. Notably, lack of knowledge, skills and attitudes is one of the barriers to the enhancement of WPP.

iii. The 2016 Election Act amendment moved prosecutorial powers from IEBC and vested the same to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution (ODPP). In its evaluation of the 2017 election, IEBC noted that this caused delays in the prosecution of election offences, making it detrimental to quick action in sexual offences complaints that were noted to have increased compared to the 2013 elections.

iv. There have been legal challenges with the Election Campaign Finance Regulations. The Election Campaign Financing was enacted in 2013, seeking to implement Article 88 (4) (1) of the CoK. However, Parliament did not approve the Election Campaign Regulations of 2016 that caused the suspension of the implementation of the Election Campaign Financing Act. Operations of the Act were suspended until after the 2017 elections. This must be regulated since it works against women candidates with limited resources. The implication is that the candidates with resources used the same to lure voters without regulation.

v. Submission and allocation of the Party lists for Special Seats, as per Article 90(1) (2) and (3) has remained challenging for IEBC, which has indicated that the formula for allocation of special seats is not exhaustive where there is a likelihood of similar numbers of qualifying parties. There is still no enabling legislation as per Article 100 of the Constitution that is to promote the representation of marginalized groups. The courts have found that it is the responsibility of IEBC to ensure political parties comply with the two-thirds gender rule in compiling their political party lists for their candidates.

vi. Provisions of the CoK enabling legislation on PWDs have not been fully implemented to the disadvantage of PWDs, particularly women with disabilities bearing the greatest brunt.

6. THE BUILDING BRIDGES INITIATIVE (BBI)

The BBI process emanated from the handshake between His Excellency President Uhuru Kenyatta and the Right Hon. Raila Odinga in March 2018. The handshake was preceded by heightened tension from the divisive 2017 national elections. Many recommendations touching on women representation are made in the proposed Constitutional Amendment 2020, including:

i. Altering the composition of the Senate to allow every county to elect one man and one woman, therefore making it a house of equal vote. The proposal scraps the 47 women representative seats in the National Assembly introduces additional 70 seats but does not provide for legislated quotas. Instead, it introduces a top-up by way of nominations to ensure compliance with not more than two-thirds gender principle using the PR system as per Article 90 of the Constitution;

ii. Inclusion of a sunset clause for affirmative action, i.e. 15 years for National Assembly and 10 years for the County Assembly; and

iii. Introduction of the ‘Best Loser Principle’ in consideration of women into the special seats, aimed at encouraging women who make it to the list to attempt to vie, be the best losers and get to be considered for the PR list.

The success of the planned referendum will alter the electoral process and implementation of the not more than two-thirds gender rule. If it fails, the status quo will be maintained.

7. KEY POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

i. The two-thirds gender rule is a key principle of the electoral system that has not been implemented. FAWE should consider working with CSOs that have been at the forefront, including FIDA (K), CRAWN TRUST, CREAW and KATIBA Institute, to continue to hold the Kenyan Executive and Legislature accountable to implement the two-thirds gender principle.

ii. There have been greater reforms to ensure political parties comply with the gender equality principle. In compliance with the court decision in the case of Katiba v. IEBC of 2017, CSOs must monitor both political parties and the IEBC to ensure the 2022 elections comply with the judgement that the political parties’ nomination lists must comply with the gender principle in Article 81(b).