CHURCHILL’S DARKEST HOUR MAGAZINE BRITAIN’S BESTSELLING HISTORY MAGAZINE

January 2018 • www.historyextra.com

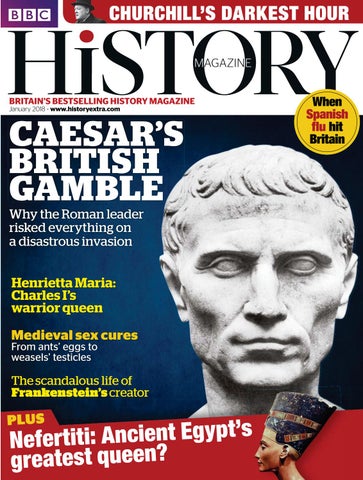

CAESAR’S BRITISH GAMBLE Why the Roman leader risked everything on a disastrous invasion

Henrietta Maria: Charles I’s warrior queen Medieval sex cures From ants’ eggs to weasels’ testicles

The scandalous life of Frankenstein’s creator

P LU S

s ’ t p y g E t n e i c n Nefertiti: A greatest queen?

When Spanish flu hit Britain