Field Notes #11

As geographers seeking to explore and understand space and place it is imperative that we prioritize a critical and ethical approach to the world and our place within it. With that in mind, we would like to acknowledge that this journal and the works within it were produced on Tiohtià:ke, the unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka. We make this acknowledgment as a preliminary step towards taking action against colonial histories and their ongoing effects, especially given our discipline’s colonial past.

It has been an honour leading the 11th edition of Field Notes. The opportunity to thoughtfully assess and curate this year’s complicated and diverse works was an enlightening process. We are proud of the team of editors and writers who contributed to making this year’s journal what it is, and are excited to share the outstanding work.

Geography is an education for life. In today’s age of uncertainty and transformation, learning through geography – whether through a classroom setting or through inthe-field travel and expeditions – crucially shapes socially and environmentally sensitive, better informed, and responsible individuals.

Through Field Notes, we are proud to publish the diverse work of the talented and creative undergraduate students in the department. This year’s edition showcases eleven papers that truly epitomize the interdisciplinarity of the program. Geography is a study of people, places, and the ways that people interact with those places. The topics, techniques, and perspectives displayed in each paper demonstrate the ways that social sciences, humanities, and physical sciences interact with one another to create a deeper geographic understanding.

We would like to issue a big thank you to our authors and editors whose hard work brought this year’s edition to life. Thanks especially to the vision of our outstanding graphic designer, Ankiné Apardian. Additionally, we would like to thank MUGS and AUS, without whom this year’s edition wouldn’t be possible. Lastly, we are especially grateful to our readers for supporting Field Notes.

Cheers!

Lilly Lecanu-Fayet and Olivia Kennedy Editors-In-ChiefIndex

The Pulp and Paper Industry Cluster of the St-Maurice Valley

Zacharie Magnan

Plex Housing as the Montreal Model

Madeleine Anderson

Tewin, a Contested Suburb: Complexities of Incorporating Reconciliation into Urban Planning

Cat Carkner

Women in the Modern Suburb: A Comparison of Albany, California and San Francisco, California

Ailish McGiffin

Dependent Development and Subalternity in Puerto Rico: Why Hurricane Fiona was Worse than Expected

Max Garcia

05 1 3 23 3 1 39

Geospatial Analysis of Water Treatment Plant Vulnerability to Storm Surge-Induced Flooding and Proposed Adaptive Strategies in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Violet Massie-Vereker

Charter City and its “Birthplace” - Hong Kong: Do Charter Cities Worsen Inequality Instead of Alleviating Poverty?

Chester Chau

The Life and Death of the MUGS Lounge: A Brief History of MUGS Lounge BH305 and Its Move

MUGS Executive Board

Meta-Analysis on the Study of Entomophagy

Isabella Pannu

Ontology of a United Geography

Abbi Baran

5 1 69 77 87 95

Abstract

This article examines the history and evolution of the pulp and paper industry in the St-Maurice region of Quebec, from the beginning of the 20th century to the 1990s. Using historical archives, government data, and company reports, the article explores the organization of the industry, labor relations, and the impact of the industry on the region. The piece shows that the industry was an important driver of development for the province of Quebec, with the St-Maurice Valley being an excellent location to develop a pulp mill due to the abundance of a low grade essence used in the production of newspapers. The industry was organized around the subcontractor system, with big entrepreneurs buying logs from small units

of peasant-lumberjack groups dispersed over a large territory. The article highlights the importance of the St-Maurice River as the main method of transportation of the wood that was destined to become paper, and the location of the paper and pulp factories downstream of the river. The article also explores the impact of the industry on labor relations and the difficulty of creating workers’ unions in a highly fragmented labor market. The article concludes by examining the collapse of the industry in the 1990s and its impact on the region.

Keywords: Pulp and paper industry, St-Maurice region, labor relations, subcontractor system, Quebec.

The pulp and paper industry has been an important driver of development for the province of Québec along with propel interest over the province’s hydroelectric potential. In the 19th century,the pulp and paper industry was first driven by a protected trade between the British empire and its colonies that used its lumber to build ships and sustain war efforts against France during the Napoleonic wars. After Britain decided to end this special monopoly system, The province was forced to compete on the free market with other European nations such as Norway and Sweden who were also important lumber exporters in Europe. Due to these changes the province turned to the United States which was developing demand for lumber and its by-products in the second half of the 19th century.

The St-Maurice Valley was an excellent location to develop a pulp mill because of the poor quality of the wood found in the region caused by the clear cuts of the past. This lumber, however, was considered perfect to sustain the insatiable demand for paper, especially newspapers at the turn of the century.1 It was at this point that the first pulp mill was erected on the St-Maurice near Grand’mère, backed by new technology and investments from the United States. This was the beginning of a region changing industry that went on to prosper until the 21st century. In this piece, I will explore the different facets of the industry using historic data and company reports compiled by the work of numerous local historians and newspapers. The organization of the industry, labour relations and the overall evolution of the industry during the period of interest from the start of the 20th century to the 1990s. We will report our main findings in the conclusion following our analysis of the death of the industry and its impact on the region.

The data sources I chose to write this article mostly consisted of historical archives and government data on the exploitation of the forest and the revenues it brought back to the province. Company reports from the Consolidated paper company, representing almost all mills in the St-Maurice region from 1933 give us insight into the possessions and investments made in the region. It is also important to note that these sources are quite specific only providing data for a few variables from specific years or groups of years. Thus, it was hard to find some continuity in the records given the fragmentation and the age of the data. Specific numbers for the rentability of specific pulp mills do not seem to be readily available.

On the other hand, I analyzed many scholarly articles relating to the economic development of the province of Québec at the turn of the 20th century specifically about the St-Maurice region. Many tend to focus on the macro-level of analysis of the industry only describing the larger-scale movements taken by the industry rather than explaining its mode of operation and interaction between the different levels of production. Most describe the level of production is easily the harvesting of the resources and the floating of “pitounes”2 down the rivers of the basin in direction of the pulp mills at different locations along the river. To complete my analysis I used one of the last reports from Emploi-Québec in which the office made an analysis of the current situation in the industry when it was on the verge of collapse in 2000. It will be interesting to compare the state and relevance of the economic cluster from one end of the 20th century to the other.

There is a long way to travel from the lumberjack camp to the paper that would be printed with the New York Times. The locational organization of the industrial cluster can be defined by the different rivers and lakes that were a part of the St-Maurice basin, (see Figure 1). The paper and pulp factories were dispersed downstream of the St-Maurice River, the major stream that connected all the other rivers and the main method of transportation of the wood that was destined to become paper. On nearly every river upstream, the provincial government gave away concessions that could be used by owners that met the conditions for an operating permit. The bosses of these concessions hired lumberjacks to go work all winter which was usually about 4 months where they would be paid according to their personal production after they were allocated a site by the foreman. Usually, these men were farmers, factory workers or even Indigenous peoples from the region. Any person, but predominantly men, who wished to make a good amount of money without any distractions such as Alcohol, Women etc would sign up.3 This system is what is called the subcontractor system.4 Big entrepreneurs bought logs from small units of peasant-lumberjack groups dispersed over a big territory. Most logging operations were very small in size but still accounted for a large part of the provincial production. More than 50% of the logs destined for the pulp industry came

from the St-Maurice valley in 1905.5 The fragmentation of the labour permitted the big entrepreneurs to control the prices they paid the workers to a minimum creating a system that kept French-Canadian labour cheap relative to other groups, which was very common at the time. This part of the industry offered high mobility and freedom for the labourers since they were paid as per their production. It is also important to note that this disorganization made the creation of workers’ unions very difficult and the lumberjacks only started to regroup in 1930 under the Catholic cultivators union to fight for better conditions.6

government enacted an embargo on the exportation of pulp, forcing the exportation of a finished product. The US, which was facing an enourmous rise in demand for newspapers introduced the underwood act in 1913 effectively waiving custom taxes on paper. This stimulated production like never before and the industry saw tremendous growth in the following years.8

The rise and fall of the St-Maurice industrial cluster tells the story of the specialization of a region. The terrain, the resources and the people were perfect for the creation of a competitive pulp and paper cluster. We saw the mode of operation of both facets of production. The sub-contraction model of the extraction of the resource led to the emergence of a traditional Fordist mode of accumulation in the actual factories. It goes without saying that this would have never happened without the considerable financial infusions from rich American capital that was pivotal in the success of this cluster for almost a hundred years.

3 C.-A.

Travailleurs Forestiers En Mauricie Au XIXe Siècle” (thesis, Université du Québec, Trois-Rivière, 1983).

4 B. Gauthier, “La sous-traitance et l’exploitation forestière en Mauricie (1850-1875),” Material Culture Review 13 (1981).

5 G. Gaudreau, “L’exploitation des forêts publiques au Québec (1874-1905) transition et nouvel essor,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 42, no. 1 (1988): 3–26.

6 C.-A. Fortin, “Les Travailleurs Forestiers En Mauricie Au XIXe Siècle” (thesis, Université du Québec, Trois-Rivière, 1983).

7 C. Bellavance, N. Brouillette, and P. Lanthier, “Financement et industrie en Mauricie, 1900-1950,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 40, no. 1 (1986): 29–50.

As the ice melts and logs start running down the river and the ramps built to avoid the dangerous sections of the river. The wood slowly floats down to the pulp mills established at different levels, the Laurentides Pulp Co. in Grand’Mère, the Belgo in Shawinigan Falls and the Wayagamack in Trois-Rivières are examples of these different companies that established themselves at the beginning of the century. These companies bought the logs from the concession owners mentioned earlier and established their production in two parts. Since the mill needs electricity to function the mills also worked as hydroelectric plants harnessing the power from the river to power the heavy machinery inside the factories. The factories were also located close to railway stations or had owners influential enough to bring the rail directly next to their operation center. It is also less costly for the companies to transform the pulp directly inside the complex and ship a finished product out to the printing centers.7

This whole system could not have been made possible without the intervention of the Québec government. In the early 1910s, the factories were only producing pulp and were exporting it to Europe and the US to be transformed into paper. Seeing that they were missing out on a lot of revenue, the

The pulp and paper industry of the St-Maurice Valley gave way to prosperous times for the region. Over time, the employees who were just considered labourers were considered professionals and were given many benefits and rewards for working lifelong careers at the mills.9 My Grandparents were given a house where they paid a very low rent until they bought it for a reasonable price from the company at retirement. This Fordist model of industrial activity came into a drastic wake-up call in the 1980s-1990s, the markets were becoming more and more open to international competition and the Consolidated Paper company which had bought out the other mills of the region in the 1930s was thrown into crisis. The logs were still quite valuable but it was becoming more and more unprofitable to transform the pulp into paper at the same location. Environmental groups were also becoming evermore concerned with the health of the St-Maurice river from the centuries of log transportation and pushed for a ban on the activity. Ultimately, the factory assets went to the Consolidated Abitibi company which decided to close down many of the region’s mills leaving only the most profitable such as the Laurentide paper mill who was still producing high-end paper.10 In 1996 the last pitounes floated on the St-Maurice. Trucks now deliver the logs driving on the 155 road from the La Tuque area.

I had some challenges with the redaction of this paper, first sources are somewhat sparse especially in terms of raw economic data on the production and rentability of the pulp industry, especially in the early 1900s. The classification is also messy, and figuring out what factories were actually owned by the same companies or when they changed names made the task more tedious than anticipated. I think that future research trying to describe this particular industrial cluster would probably be pertinent since most of the literature is written by historians and an economist’s point of view could be beneficial to understand the trends in industrial activities of the St-Maurice.

9 Ibid

Bellavance, Claude, Normand Brouillette, and Paul Lanthier. “Financement et industrie en Mauricie, 1900-1950.” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 40, no. 1 (1986): 29-50. doi:10.7202/304423ar. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/haf/1986-v40-n1-haf2342/304423ar. pdf?fbclid=IwAR2V_mkLsASXDO0C__RWPGeU7EquZrXxWalLCX90p-oA78G7sV_wBvMKyBU.

Bourgeois, Vincent. “La capitale mondiale du papier journal.” Cap-aux-Diamants 98 (2009): 19-21. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/ cd/2009-n98-cd1044827/6368ac/.

“Bûcherons de la Manouane.” 1962. YouTube video, 23:47. Canada: ONF. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4DJAB5kGuo&fbclid=IwAR3zdl7gUqEAy5njxxWVChkah9bNK1b2qxmXtek8QVgq1FKFQeZM5XlcKok

Consolidated Paper Corporation Limited. “First Annual Report of Consolidated Paper Corporation Limited and its Subsidiaries.” 1933. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://digital. library.mcgill.ca/hrcorpreports/pdfs/C/Consolidated_Paper_Corporation_Ltd_1933. pdf?fbclid=IwAR06ikD_sZN-hgu9fcNqmJHbTcr0rz_iS-I57pDvXkqGatn9e4GWfVv8nck.

Fortin, Claude-André. “Les Travailleurs Forestiers En Mauricie Au XIXe Siècle.” PhD diss., Université du Québec, Trois-Rivières, 1983. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://depot-e.uqtr.ca/ id/eprint/6348/1/000325838.pdf.

Gaudreau, Guy. “L’exploitation des forêts publiques au Québec (1874-1905) : transition et nouvel essor.” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 42, no. 1 (1988): 3-26. doi:10.7202/304648ar. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/ haf/1988-v42-n1-haf2382/304

Gauthier, Benoit. “La sous-traitance et l’exploitation forestière en Mauricie (1850-1875).” Material Culture Review 13 (1981). Accessed March 29, 2023. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index. php/MCR/article/view/17080.

Hallé, François. Profil de l’industrie pâtes et papiers en Mauricie François Hallé.... Trois-Rivières: Emploi-Québec Mauricie, 2002. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://collections. banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/50643.

Hardy, René “L’exploitation forestière dans l’histoire du Québec et de la Mauricie”. Histoire Québec 6, no. 3 (2001) : 6–7. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ hq/2001-v6-n3-hq1057791/11343ac/

Abstract

Montreal’s triplexes are an emblem of the city’s architectural style, contributing to the diverse, dense, and dynamic character of the city. Built mainly in the late 19th century, plexes have stood the test of time as an efficient yet comfortable housing option. The vertically stacked apartments foster rental dynamics which support upward mobility, offering an affordable housing solution which promotes diversity. Additionally, plexes are designed for density at the human scale: their external staircases make individual units ground-oriented and provide a sense of independence while also fostering dense and highly walkable neighbourhoods. In an increasingly expensive and inaccessible

housing market, the Montreal plex housing model is a form which could pose innovative and sustainable solutions for the densification of other cities.

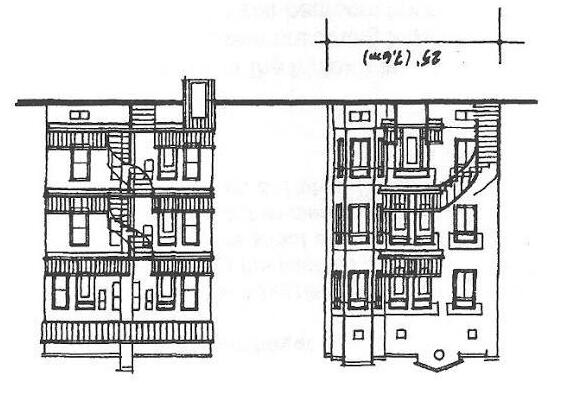

Triplex and 6-plex for sale in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood, Madeleine Anderson, April 2022.

Along with Habitat 67, the Notre Dame Basilica, and the Olympic stadium, Montreal’s rows of unique plex apartments have become an emblem of the city’s architectural style. The outdoor staircases that climb, coil and curve along Montreal’s residential streets give the city a truly unique flair, making it stand out among other North American cities. Built most intensely in the late 19th century, the dwelling style has stood the test of time, despite increasing trends towards suburbanization or high-rise apartment buildings seen in other cities. In an increasingly expensive and inaccessible housing market, the Montreal plex housing model is a form which could pose innovative and sustainable solutions for the densification of other cities.

The inspiration for this paper comes from my own third floor triplex apartment in the Mile End, which I adore living in for both the apartment itself as well as the energy of the neighbourhood. Love them or hate them, the plexes are a quintessential experience as a renter in Montreal, and their history and influences make them a truly Montrealspecific architectural phenomenon.

What is a Plex?

The term plex is derived from the suffix of the types of multi-family stacked housing most common in Montreal; duplexes having two units, triplexes having three units, and multiplexes having generally four or six units, though many variations exist across the city. The two- or three-story buildings typically contain one apartment per story and those with three or more units have a distinct visual style due to their external staircases. The standard triplex has separate entrances for each unit; the bottom floor having access from the street, the second floor being accessible from an external staircase onto a shared balcony with the third floor, and the third unit generally having a second, internal staircase leading to the top (Fig. 1 & 3). Plexes are built on modest residential lots, generally 20 to 30 feet wide1 and form continuous facades, often along entire blocks (Fig. 2 & 3). By stacking units and sharing a wall with

neighbouring buildings, plex buildings are able to efficiently conserve heat in the winter months, as heat is distributed upwards and not lost to the outside.2 Typically, units are laid out with bedrooms and living spaces in the front (street side), with the kitchen and laundry or other utility areas in the back, as well as access to a back balcony (Fig. 1). At the back, a narrow alleyway serves the rear of the buildings, where small backyards, parking spaces, or storage sheds can often be found. In addition to being energy-efficient, the openings at the front and rear of the units allows for optimal light distribution and through air flow, providing relief in the hot summer months. The form of the Montreal plex is unique for a variety of reasons; its external staircases and individual entrances to each unit, as well as the practice of vertical stacking (as opposed to traditional British townhouses). The social and economic backdrop in which these versatile buildings were constructed, as discussed below, ultimately shaped their iconic form.

How did Plex Housing Become so Ubiquitous in Montreal?

The largest building cycle of Montreal’s plexes took place in the late 19th century. Due to intense industrialization and urbanization, Montreal’s population almost tripled between 1870 and 1900.3 One or two large factories opened every year between 1842 and 1855,4 and consequently the housing stock grew from 12,000 to 65,000 households between

1 Sandrine Rastello, “The Plexes of Montreal Make Room for Change,” Bloomberg Citylab, August 4, 2021, https:// www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-08-04/ looking-to-rent-in-montreal-get-to-know-the-plex

2 Anne-Lise Charroy, “Montreal’s Triplexes: The ‘Plex,’” Dynamic Cities Project, accessed March 23, 2023, http://dynamiccities. org/inspirations; Andrea Kennedy, “Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes,” The Fifth Column 10, no. 4 (2002): 64–69.

3 Jason Gilliland and Sherry Olson, “Claims on Housing Space in Nineteenth-Century Montreal,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire Urbaine 26, no. 2 (1998): 3–16; Kennedy, “Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes.”

4 David B. Hanna, The Layered City: A Revolution in Housing in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Montreal, Partage de l’espace, no. 6 (Montreal: Dept. of Geography, McGill University, 1986).

1860 and 1900.5 Additionally, the need for affordable housing for the working class was intensified by several fires which wiped out large swaths of the existing housing stock: of the recorded housing in 1950, 19% was wiped out by fire.6 Following the Great Fire of 1952, the city prohibited wood construction.7 Thus, not only was the existing housing stock depleted, but the supply and feasibility of affordable housing was constrained, as new laws required housing be built with more expensive materials, such as stone or brick.

Multi-family housing was a way in which more expensive and fire-safe housing could be affordable to working class families. Additionally, the vast majority of Montreal workers in the late 19th to early 20th centuries walked to work, making urban sprawl an unfeasible option. The stacked dwelling thus became an obvious solution to the intense need for housing in Montreal at this time.

The plex’s unique exterior staircase was derived from a variety of cultural phenomena. It allowed for multiple stacked units to have their own entrances from the outside and for each unit to have its own street address. Separate entrances, along with balconies and platforms were favourable for families who moved from the countryside into the city, as they were reminiscent of the porches on their country homes.8 This also allowed residents to live in a dense urban environment while retaining a sense of privacy and independence. The external staircase was inspired by older duplex houses in Quebec,

which were freestanding houses, but which featured an outdoor staircase which allowed upstairs tenants to have a separate entrance from the downstairs. Another reason for the separate entrances was the influence of the catholic church; it was frowned upon that multiple households should share a common entrance, because any number of sinful activities could happen in these liminal, unsupervised spaces.9

More practically, the external staircase saved money on utility costs, as it resulted in one less interior space that required heating. The city also implemented building setback rules, which required that the foundations of buildings be a certain distance from the sidewalk, for sanitation and crowding reasons. This led to builders opting to put staircases on the outside, to optimize living space without breaking any building codes.

neighbourhoods a distinctly French flair, the vast majority of plexes were built with a flat roof, maximizing space and cost efficiency.

6 Hanna, The Layered City

7 Paul-André Linteau and Peter McCambridge, The History of Montréal: The Story of Great North American City (Monteal, UNITED STATES: Baraka Books, 2013), http://ebookcentral. proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=1162758

8 Kennedy, “Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes.”

9 Rastello, “The Plexes of Montreal Make Room for Change.”

10 Hanna, The Layered City

11 Kennedy, “Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes.”

12 Kennedy.

Though plex buildings share the recognizable features previously mentioned – stacked units, outdoor staircases, narrow but deep lots, back lane access – there is great variation of layout, materials, and exterior ornamentation across the city. The blocks are highly customizable, with some having larger two-story units up top to accommodate larger families, or different creative staircase layouts and shared balconies. These buildings were mostly not built en masse by large companies (though some larger scale actors were involved10), rather by small builders who took inspiration from each other and put their own flare into the projects. Thus, despite the residential and even suburban applications of this housing type, much variation among buildings exists, creating idiosyncrasies which “set Montreal’s townhouses apart from their European counterparts”.11 The wealthier British-inspired townhouses were often differentiated with flamboyant facades and different types of cladding, such as red brick, glazed brick, or Greystone, whereas the French workingclass residences were “usually quite austere, with dormer windows and cornice details to provide some decorations on the mansard roof”.12 While the mansard roof gave certain

At the time in which plex construction peaked, Montreal was largely divided between French, English, and Irish origins, with few common institutions. According to David Hanna (1986), “ethnic division fostered a mutually disadvantageous competition”,13 keeping wages low and characterizing Montreal as a manufacturing city. Additionally, the ownership dynamics of the plexes reflected the hierarchical class structure in Montreal. Oftentimes one family would own the entire building and rent out the other units. In some duplexes, a smaller unit in the semi-basement would be an affordable option for low-wage workers, while the wealthier owners of the building lived up top. In triplexes, the owners might occupy the bottom floor, and leave the treacherous outdoor stairs to the tenants up top. This created a physical class hierarchy within Montreal’s streets, but also meant that people of various classes and occupations lived together in close proximity, a recipe for diversity. The practice of tenants and landlords living in the same building persists today, though it is now increasingly common for entire buildings to be rented by a landlord who owns multiple buildings, or for the ownership of plex buildings to split up in condominium style.

Plexes also fostered diversity by providing affordable houses for recent immigrants and becoming a space of social mobility. Originally, the majority of the plexes were owned by wealthier English and FrenchCanadian families who lived in one of the units, and the other units were rented out to newer immigrants, often of Italian and Lebanese origin. But when the original owners opted to relocate to single-family homes in the suburbs, this opened the opportunity for those Italian and Lebanese renters to own buildings and provide rental housing to a new wave of migrants to the

city.14 In addition to the rental dynamics, plexes offer a form of high-density affordable housing designed at the human scale; they are ground-oriented and provide a sense of space and independence while enabling a high level of walkability and variability. In many cases, shops and establishments can occupy the ground floor, enriching neighbourhoods and promoting local businesses. Thus, the architectural form of the multiplex and the small-scale rental dynamics it fosters, has provided a vessel through which Montreal has been able to maintain its diverse, dense, and dynamic character for over 150 years.

Despite the classic triplex being a recognizable symbol of Montreal’s urban landscape and character, they were not granted any sort of special protection. In 1945, “the outdoor staircases were seen as unsightly” and a by-law was passed prohibiting them which initiated a new wave of apartment block and high-rise construction that lasted until the by-law was repealed in 1970.15 Without sufficient protection, the original stock of downtown townhouses is being swept away to make room for new developments.16 However, despite some new trends in housing, plexes remain the most common housing type in Montreal, especially in trendy central districts such as the Plateau and Little Italy (Fig. 5). The cultural and economic benefits of plexes are continuously seen, making maintenance and renovation of older buildings as well as the construction of new, modern multiplex housing an attractive option. In 1997, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation conducted research on the viability of plex

13 Hanna, The Layered City

14 Konrad Yakabuski, “Triplexes Help Keep City Vibrant,” The Globe and Mail February 20, 2004, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/ real-estate/triplexes-help-keep-city-vibrant/article994172/; Hanna, The Layered City

15 Yakabuski, “Triplexes Help Keep City Vibrant.”

16 Kennedy, “Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes.”

housing revitalization projects, finding that the “renewal of plex housing as a viable model is not only possible, it is also highly desirable, due to its many social, economic, environmental and sustainable development benefits”.17 With the demands for space per person in apartments increasing over the decades, many triplex buildings have been renovated and remodelled to increase space, or to simply update the facilities. The signs of this kind of update can be seen in my own triplex apartment, where the original walls were knocked down to create a larger, open living room where there was once a corridor connecting many smaller rooms. Additionally, examples of modern multiplex projects fit seamlessly with the pre-existing stock of plexes and are a viable model for new residential development (Fig. 7).

The Montreal Model could thus also be considered as a solution for other cities in need of densification. With cities growing and the demand for housing increasing, densification is a favourable option to urban sprawl, which brings with it a host of economic, environmental, and even health problems. The triplex offers a medium density housing solution which can accommodate up to 350 persons per hectare,18 promoting social interaction and diversity while still retaining a sense of place and independence. For example, Figure 8 compares a standard Montreal triplex to a typical Vancouver lot. The triplex is medium density housing at the human scale: dense enough to be within walking distance from all necessary amenities and to have a lively neighbourhood culture, and dispersed enough that units can have their own front door, not needing elevators to reach your apartment.

17 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), “‘Plex’ Housing : A Renewed Tradition,” Research Highlight. Technical Series 01-102 (Ottawa, July 1, 2002), https://publications.gc.ca/ site/eng/408767/publication.html, 4.

18 Charroy, “Montreal’s Triplexes: The ‘Plex.’”

Broudehoux, A.-M. (2019). Montrealism or Montréalité? Understanding Montreal’s Unique Brand of Livability. In Community Livability (2nd ed., pp. 3–15). Routledge.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). (2002, July 1). “Plex” housing: A renewed tradition. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/408767/publication.html.

Charroy, A.-L. (n.d.). Montreal ’Plex. Dynamic Cities Project. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from http:// dynamiccities.org/inspirations.

Gilliland, J., & Olson, S. (1998). Claims on Housing Space in Nineteenth-Century Montreal. Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire Urbaine, 26(2), 3–16.

Hanna, D. B. (1986). The layered city: A revolution in housing in mid-nineteenth-century Montreal. Dept. of Geography, McGill University.

Kennedy, A. (2002). Montreal’s Duplexes and Triplexes. The Fifth Column, 10(4), 64–69.

Linteau, P.-A. (2013). The History of Montréal: The Story of Great North American City (P. McCambridge, Trans.). Baraka Books. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail. action?docID=1162758.

Oh The Urbanity! (2020, October 26). Montreal’s Medium-Density Multiplex Neighbourhoods. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vsn0ahdfQ9k.

Rastello, S. (2021, August 4). The Plexes of Montreal Make Room for Change. Bloomberg CityLab https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-08-04/ looking-to-rent-in-montreal-get-to-know-the-plex

Yakabuski, K. (2004, February 20). Triplexes help keep city vibrant. The Globe and Mail. https:// www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/triplexes-help-keep-city-vibrant/article994172/

In settler-colonial nations such as Canada, cities and urban planning processes can act as mechanisms of colonial control. Moreover, there is a historic and ongoing underrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in Canadian planning processes and municipal governments. However, some Indigenous groups are now challenging these exclusionary dynamics, asserting their right to the city through their own urban mega-projects. One such project is Tewin, a future residential development that Ottawa City Council agreed to include within the city’s new urban boundary in 2021. Tewin is a collaboration between the Algonquins of Ontario, a treaty-negotiating body of Algonquin communities, and Taggart Investments, a local development company. Tewin is said to be founded on Algonquin values, and local political proponents of

the project have framed it as a symbol of reconciliation. However, both the project’s legitimacy and reconciliatory nature have been called into question by city planners and other Algonquin groups. Using the case study of Tewin, this paper demonstrates the complexities of enacting reconciliation through municipal planning initiatives. More specifically, it argues that local actors involved in reconciliatory urban planning must be prepared (i) to mediate between mainstream and Indigenous planning ideologies, and (ii) to carefully consider issues of identity when engaging in community consultation or participatory planning.

Keywords: Indigenous urbanism, reconciliation, urban planning.

In settler-colonial nations, cities are “key mechanisms of colonial expansion”,1 acting as economic command centres and residential hubs for settler populations. Thus, scholars have identified that cities and local governments in Canada are constructed as non-Indigenous spaces. Stranger-Ross describes the “widespread view that … Aboriginal people [have] no place in modern urban life”,2 even though over half of Indigenous peoples in Canada now live in urban centres.3 Meanwhile, Hertiz and the Ontario Professional Planners Institute note Indigenous peoples’ historic and ongoing underrepresentation in planning processes and municipal governments.4 However, some Indigenous groups are now challenging these exclusionary dynamics, asserting their right to the city through their own urban

Jordan Stanger-Ross, “Municipal Colonialism in Vancouver: City Planning and the Conflict over Indian Reserves, 1928–1950s,” Canadian Historical Review 89, no. 4 (2008): 543.

2 Stanger-Ross, “Municipal Colonialism in Vancouver,” 542.

3 Joanne Heritz, “From Self-Determination to Service Delivery: Assessing Indigenous Inclusion in Municipal Governance in Canada,” Canadian Public Administration 61, no. 4 (2018): 596.

4 Joanne Heritz, “From Self-Determination to Service Delivery: Assessing Indigenous Inclusion in Municipal Governance in Canada,” Canadian Public Administration 61, no. 4 (2018): 599; Ontario Professional Planners Institute, “Indigenous Perspectives in Planning” (Ontario Professional Planners Institute, 2019), 10, https://ontarioplanners.ca/OPPIAssets/Documents/OPPI/ Indigenous-Planning-Perspectives-Task-Force-Report-FINAL.pdf

5 Julie Tomiak, “Contesting the Settler City: Indigenous Self-Determination, New Urban Reserves, and the Neoliberalization of Colonialism,” Antipode 49, no. 4 (2017): 937.

6 Jon Willing, “Council Allows Algonquins of Ontario ‘Tewin’ Site inside a New Urban Boundary,” Ottawa Citizen, February 10, 2021, https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/council-allows-algonquins-of-ontario-tewin-site-inside-a-new-urban-boundary

7 CTV News Ottawa, “Ontario Approves Ottawa’s New Official Plan with Expanded Urban Boundary,” CTV News Ottawa, November 4, 2022, https://ottawa.ctvnews.ca/ontario-approves-ottawa-s-newofficial-plan-with-expanded-urban-boundary-1.6140323

8 Joanne Chianello, “Tewin Has Councillors Making up Planning Policy on the Fly,” CBC, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/ news/canada/ottawa/tewin-reconciliation-1.5905975

9 AOO-Taggart, “Homepage,” Tewin, 2023, https://www.tewin.ca/ (AOO-Taggart, 2022).

10 Jamie Pashagumskum, “Tewin Development by Algonquins of Ontario Will Be Voted on Wednesday,” APTN News (blog), February 10, 2021, https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/ottawa-citycouncil-to-vote-on-tewin-housing-development-wednesday/ Jamie Pashagumskum, 2021.

11 However, given the length of the paper, judgments or conclusions concerning Tewin’s overall contribution to the mission of reconciliation are not within its scope.

mega-projects, such as Senákw in Vancouver or New Urban Reserves (NURs).5

Another such project is Tewin, a future residential development that the Ottawa City Council agreed to include within the city’s proposed new urban boundary in February 2021.6 The new urban boundary, which was officially endorsed by the provincial government in 2022 (albeit in an amended form), aims to expand Ottawa’s boundary, allowing the city to develop more land, supply more housing, and accommodate more residents.7 Tewin is a collaboration between the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO), a treaty-negotiating body of Algonquin communities, and Taggart Investments, a local development company. It will be a suburb of 45,000 residents, built on 445 hectares of land that AOO-Taggart bought from the province in 2020 for $16.9 million (Figure 1).8 The AOO promotes Tewin as a “community founded on Algonquin values” that will deliver “wide–scale socioeconomic benefits for the Algonquin people”.9 In line with this narrative, local political proponents of the project, including then-Mayor Jim Watson and City Councilor Tim Tierney, posited Tewin as a symbol of reconciliation when advocating for its approval. Tierney stated that the Council is “committed to reconciliation with local Indigenous communities and recognizes the importance of working with the [AOO] as a meaningful opportunity towards achieving that goal”10 (Pashagumskum, 2021).

However, both the project’s legitimacy and reconciliatory nature have been called into question by city planners and other Algonquin groups. Using the case study of Tewin, this paper demonstrates the complexities of enacting reconciliation through municipal planning initiatives. More specifically, it argues that local actors involved in reconciliatory urban planning must be prepared (i) to mediate between mainstream and Indigenous planning ideologies, and (ii) to carefully consider issues of identity when engaging in community consultation or participatory planning.11

To illustrate these points, I first explain how local actors struggle to find a balance between advancing reconciliation through Tewin and adhering to mainstream planning policy and expertise. Second, by exploring current debates around Indigenous identity, I show that determining which actors should be involved in such ‘reconciliatory’ urban planning is not a clear-cut process. Finally, I reflect on the task of incorporating Indigenous sovereignty and reconciliation into municipal planning practices and make suggestions for future research.12

existing suburbs, water mains, and public transit in Ottawa. Meanwhile, parcels of land that city planners usually recommend for inclusion in the new urban boundary achieve scores between 40 and 70.14 In a joint statement, local developers Claridge Homes and Minto, whose lands were initially passed over in favour of Tewin, expressed their dismay that the Council opted to sidestep a “prescribed scoring process … and include a parcel of land with a zero score on servicing”.15 The Council and AOO-Taggart also dismissed city planners’

Figure 1. The area where the AOO and Taggart Investments will build Tewin. (www. tanakiwin.com)

Tewin has faced criticism and scrutiny from many urban actors, including Council members, planning staff, and local environmental groups.13 However, for most actors who oppose Tewin, the central issue is not its reconciliatory mission or Algonquin character. Rather, disapproval stems from its associated divergences from mainstream planning policy, namely the Tewin land’s inclusion in Ottawa’s new urban boundary despite its very low score on council-approved planning criteria. Parcels of Tewin land scored as low as -8 points due to deductions related to its distance from

12 Following Tomiak (2017), I want to briefly discuss my positionality in relation to this work. am a Vietnamese-Canadian settler who grew up in Ottawa, on the traditional and unceded land of the Anishinaabe Algonquin Nation. As such, I write as an outsider to the Algonquin Nation and do not intend to speak for them.

13 Willing, “Council Allows Algonquins of Ontario ‘Tewin’ Site inside a New Urban Boundary”; Chianello, “Tewin Has Councillors Making up Planning Policy on the Fly”; Paul Johanis, “Johanis: There’s No Need to Expand Ottawa’s Urban Boundary Anywhere,” Ottawa Citizen, October 4, 2022, https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/ johanis-theres-no-need-to-expand-ottawas-urban-boundary

14 Kate Porter, “Tewin: The Land at the Centre of Ottawa’s Reconciliation Controversy | CBC News,” CBC, February 5, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ tewin-parcel-details-planners-aoo-1.5901324

15 Kate Porter, “Algonquins Come out Sudden Winners in Urban Boundary Vote,” CBC, January 27, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ algonquins-ontario-tewin-planning-arac-vote-1.5888419

request to prolong Tewin’s approval for a five-year study to comprehensively assess its long-term financial and environmental consequences, citing the time-sensitive nature of accomplishing reconciliation.16

By choosing Tewin lands over more highlyrated lands in the west,17 Council disregarded the Provincial Policy Statement, Ontario’s planning guidelines.18

Mayor Watson acknowledged planners’ unfavourable assessment of the Tewin lands, stating that “I know we have a point and a rating system, but I think at times you have to be flexible to recognize that when a proposal like this comes forwards and it’s the first of its kind, that we should take it seriously and look at its merits”.19 While the low quality of the Tewin lands will present real development challenges, Watson’s comments evoke Bouvier and Walker’s work, which questions if Indigenous inclusion in city planning should be “conditional upon strict adherence to colonial capitalism and

16 Chianello, “Tewin Has Councillors Making up Planning Policy on the Fly.”

17 That said, when the Ontario Provincial Government ultimately approved Ottawa City Council’s new official plan in November 2022 (which includes Tewin), they did make amendments to include additional areas for urban development. The provincial government’s amendments include land previously-passed over in favour of Tewin, such as the South March area (CBC News, 2022).

18 Chianello, “Tewin Has Councillors Making up Planning Policy on the Fly.”

19 Kate Porter, “Watson Seeks Reconciliation with Algonquins of Ontario Development | CBC News,” CBC, January 27, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/watson-support-algonquins-of-ontario-taggart-development-1.5890474

20 Noelle Bouvier and Ryan Walker, “Indigenous Planning and Municipal Governance: Lessons from the Transformative Frontier.,” Canadian Public Administration 61, no. 1 (2018): 133.

21 Bouvier and Walker, 131.

22 John Forester, Planning in the Face of Power, 1989, 28.

23 Bouvier and Walker, “Indigenous Planning and Municipal Governance,” 131.

24 Due to legacies of and ongoing colonialism, there are debates regarding the authenticity or legitimacy of non-status-holding Indigenous peoples’ claim to Indigenous identity. Because of the Indian Act, there are many people of First Nations descent who are unable to acquire ‘Indian Status’ or memberships in First Nations communities. Some individuals also hold the view that those who hold status are the only ‘authentic’ First Nations or Indigenous peoples, causing tension. For more information, see: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_status/

settler (including municipal) regulatory authority.”20 Tewin’s opponents could reflect on the financial and technical difficulties involved in developing the Tewin lands (costly expansion of water pipes and transit, for example) and ask themselves if these factors should take precedence over the project’s potential socio-economic contributions to reconciliation.

Tewin is a development that compromises adherence to colonial-derived mainstream planning practices and expertise in favour of centering reconciliation and Indigenous planning proposals. This case study demonstrates that incorporating reconciliation into municipal planning practices may involve the complicated task of negotiating conflicting demands from the “parallel traditions of colonial-derived mainstream and Indigenous planning”.21 Urban centres that seek to develop similar projects should be prepared to navigate similar conflicts between actors and planning goals.

Reconciliatory Planning: Who Gets a Seat at the Table?

Forester writes that planners, by merit of shaping who is involved in the planning process, “can make that process more democratic or less.”22 In the Canadian context, making planning processes more democratic must involve consulting Indigenous peoples and recognizing their “distinctive rights and title beyond those of typical urban stakeholders”,23 given their ongoing exclusion from planning practices, as well as their position as the traditional stewards of the land. However, the controversy surrounding the legitimacy of the AOO’s claim to Indigeneity demonstrates that planners and municipal governments must exercise caution and cultural sensitivity when choosing who to consult in ‘reconciliatory’ planning processes.24

Out of the ten Algonquin communities that make up the AOO, only the Ontario-based Pikwakanagan First Nation is a federally recognized, status-holding Algonquin

community.25 In light of this, many of the recognized Algonquin communities that are not part of the AOO have criticised the Council for failing to consult them on Tewin, given that they are championing it as an act of reconciliation.26 In a joint statement, the Chiefs of the recognized Wolf Lake, Timiskaming, and Barriere Lake Algonquin communities condemned the Council’s approval of the project. They argued that “reconciliation is long overdue. But we believe that it must be done in the right way, and with the right parties”.27 The process of achieving reconciliation through a project on unceded lands, the chiefs argued, “must take place between two nations, not between a municipal government and an organisation or company”.28 Kitigan Zibi First Nation Elder Claudette Commanda went as far as to deem then-Mayor Watson’s endorsement of Tewin as a flawed attempt to get a “gold star on his reconciliation report card”.29 In response to this backlash, Chief of Pikwakanagan First Nation Wendy Jocko and Ottawa AOO representative Lynn Clouthier defended their Algonquin identity and reiterated the reconciliatory nature of Tewin. Jocko asserted that any status-holding Algonquin questioning the Indigeneity of the AOO’s non-status Algonquin groups was subscribing to colonial-minded definitions of Indigenous identity.30

Considering Ottawa’s existence on unceded Algonquin territory and the Council’s proclamation of Tewin as “reconciliation with local Indigenous communities”,31 it stands to reason that every recognized Algonquin community, regardless of whether or not the AOO should be considered a legitimate representative of the Algonquin nation, should have been consulted before Tewin was given the green light in the name of reconciliation. As the debates around the identities of Tewin’s partners demonstrate, planners and municipal governments attempting to enact reconciliation via planning initiatives should be mindful of whom they include in the planning process to ensure that these initiatives respect all Indigenous actors and meaningfully contribute to their goal of reconciliation.

Undoubtedly, advancing the Indigenization of the city and Indigenous participation in planning processes are necessary goals for local actors, primarily municipal politicians and planners. However, as debates surrounding Tewin demonstrate, these are not straightforward tasks. In shaping the ‘reconciliatory city’, urban governance actors must be keenly aware of the tensions between Indigenous versus mainstream colonial planning policies and expertise. Moreover, they should be cognizant of the complexities of Indigenous identity.

Future research could compare the urban governance dynamics surrounding Tewin with those of other urban Indigenous developments, such as the Squamish Nation’s Senákw mega-project in Vancouver or the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation’s NURs. Moreover, the current research could be elaborated on once Tewin’s master plan is released. Who, for example, was consulted while drafting the plan? Although out of the scope of this short paper, questions of how effectively speculative and capitalist real estate projects such as these can advance Indigenous sovereignty are also worthy of further analysis.

25 Hafez, “Algonquin Anishinabeg vs. The Algonquins of Ontario: Development, Recognition & Ongoing Colonization - Yellowhead Institute,” Yellowhead Institute, February 18, 2021, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2021/02/18/algonquin-anishinabeg-vs-the-algonquins-of-ontario-development-recognition-ongoing-colonialization/

26 Joanne Laucius, “Chiarelli Asks Province to Delay Approving Official City Plan so New Council Can Reconsider Tewin,” Ottawa Citizen, September 18, 2022, https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/ bob-chiarelli-asks-province-to-delay-approving-official-plan-so-newcouncil-can-reconsider-tewin-lands

27 Algonquin Nation Secretariat, “Algonquin Nation Secretariat Calls for Tewin Project to Be Put on Ice.” (Algonquin Nation Secretariat, February 8, 2021), http://new-wordpress.algonquinnation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ANS-Press-Release-AOO-Tewin.pdf

28 Kate Porter and Joanne Chianello, “Council Greenlights Algonquins of Ontario Land for Future Suburb CBC News,” CBC, February 11, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ urban-boundary-tewin-council-vote-properties-1.5908405

29 Porter and Chianello.

30 Hafez, “Algonquin Anishinabeg vs. The Algonquins of Ontario: Development, Recognition & Ongoing Colonization - Yellowhead Institute.”

31 City of Ottawa, “Indigenous Relations,” City of Ottawa, November 14, 2022, https://ottawa.ca/en/city-hall/creating-equal-inclusive-and-diverse-city/indigenous-relations; Pashagumskum, “Tewin Development by Algonquins of Ontario Will Be Voted on Wednesday.”

References

Algonquin Nation Secretariat. “Algonquin Nation Secretariat Calls for Tewin Project to Be Put on Ice.” Algonquin Nation Secretariat, February 8, 2021. http://new-wordpress.algonquinnation. ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ANS-Press-Release-AOO-Tewin.pdf

AOO-Taggart. “Homepage.” Tewin, 2023. https://www.tewin.ca/.

Bouvier, Noelle, and Ryan Walker. “Indigenous Planning and Municipal Governance: Lessons from the Transformative Frontier.” Canadian Public Administration 61, no. 1 (2018): 130–35.

Chianello, Joanne. “Tewin Has Councillors Making up Planning Policy on the Fly.” CBC, February 9, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/tewin-reconciliation-1.5905975

City of Ottawa. “Indigenous Relations.” City of Ottawa, November 14, 2022. https://ottawa.ca/ en/city-hall/creating-equal-inclusive-and-diverse-city/indigenous-relations

CTV News Ottawa. “Ontario Approves Ottawa’s New Official Plan with Expanded Urban Boundary.” CTV News Ottawa, November 4, 2022. https://ottawa.ctvnews.ca/ ontario-approves-ottawa-s-new-official-plan-with-expanded-urban-boundary-1.6140323.

Forester, John. Planning in the Face of Power, 1989.

Hafez. “Algonquin Anishinabeg vs. The Algonquins of Ontario: Development, Recognition & Ongoing Colonization - Yellowhead Institute.” Yellowhead Institute, February 18, 2021. https:// yellowheadinstitute.org/2021/02/18/algonquin-anishinabeg-vs-the-algonquins-of-ontario-development-recognition-ongoing-colonialization/

Heritz, Joanne. “From Self-Determination to Service Delivery: Assessing Indigenous Inclusion in Municipal Governance in Canada.” Canadian Public Administration 61, no. 4 (2018): 596–615.

Johanis, Paul. “Johanis: There’s No Need to Expand Ottawa’s Urban Boundary Anywhere.” Ottawa Citizen, October 4, 2022. https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/ johanis-theres-no-need-to-expand-ottawas-urban-boundary.

Laucius, Joanne. “Chiarelli Asks Province to Delay Approving Official City Plan so New Council Can Reconsider Tewin.” Ottawa Citizen, September 18, 2022. https://ottawacitizen.com/news/ local-news/bob-chiarelli-asks-province-to-delay-approving-official-plan-so-new-council-canreconsider-tewin-lands

Nejad, Sarem, Ryan Walker, Brenda Macdougall, Yale Belanger, and David Newhouse. “‘This Is an Indigenous City; Why Don’t We See It?’ Indigenous Urbanism and Spatial Production in Winnipeg.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 63, no. 3 (2019): 413–24.

Ontario Professional Planners Institute. “Indigenous Perspectives in Planning.” Ontario Professional Planners Institute, 2019. https://ontarioplanners.ca/OPPIAssets/Documents/OPPI/ Indigenous-Planning-Perspectives-Task-Force-Report-FINAL.pdf.

Pashagumskum, Jamie. “Tewin Development by Algonquins of Ontario Will Be Voted on Wednesday.” APTN News (blog), February 10, 2021. https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/ ottawa-city-council-to-vote-on-tewin-housing-development-wednesday/.

Porter, Kate. “Algonquins Come out Sudden Winners in Urban Boundary Vote.” CBC, January 27, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ algonquins-ontario-tewin-planning-arac-vote-1.5888419

Porter, Kate, and Joanne Chianello. “Council Greenlights Algonquins of Ontario Land for Future Suburb | CBC News.” CBC, February 11, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ urban-boundary-tewin-council-vote-properties-1.5908405.

Stanger-Ross, Jordan. “Municipal Colonialism in Vancouver: City Planning and the Conflict over Indian Reserves, 1928–1950s.” Canadian Historical Review 89, no. 4 (2008): 541–80.

“Tewin: The Land at the Centre of Ottawa’s Reconciliation Controversy | CBC News.” CBC, February 5, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ tewin-parcel-details-planners-aoo-1.5901324

Tomiak, Julie. “Contesting the Settler City: Indigenous Self-Determination, New Urban Reserves, and the Neoliberalization of Colonialism.” Antipode 49, no. 4 (2017): 928–45.

“Watson Seeks Reconciliation with Algonquins of Ontario Development | CBC News.” CBC, January 27, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ watson-support-algonquins-of-ontario-taggart-development-1.5890474.

Willing, Jon. “Council Allows Algonquins of Ontario ‘Tewin’ Site inside a New Urban Boundary.” Ottawa Citizen, February 10, 2021. https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/ council-allows-algonquins-of-ontario-tewin-site-inside-a-new-urban-boundary.

“Cities are planned by men for men”.1 The lack of consideration given to considering the needs of women in urban planning means that women have a unique relationship with their built environment. This necessitates the analysis of how women interact with and within cities and how these interactions evolve as social contexts shift. Suburbs are a particularly interesting entity to examine both when discussing the role of women in urban areas and how these roles have transformed over time. Although suburbs and cities once offered two segmented lifestyles, the suburb today appears to be taking on more characteristics of city life, which has been beneficial for the suburban woman. Through a comparison of the major city of San Francisco, California (population: 874,784)2 and the suburb of Albany, California (population: 20,145)3, it becomes evident that previous views on a woman’s life in the suburb are less applicable in the present context. Although suburbs were once thought to confine women, suburban life is increasingly becoming interconnected with the needs of modern women.

The city is commonly represented as a source of liberation for women while the suburb is portrayed as a space that limits women’s potential. A popular premise in television and film is a young woman attempting to get out of her stifling suburban town to reach the wonderful big city. The T.V. show The Carrie Diaries,4 centers on a

Wekerle, G. 2006. “A Woman’s Place Is in the City.” Antipode doi:10.1111/j.1467- 8330.1984.tb00069.x, 12.

2 “San Francisco, CA.” 2021. Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/ geo/san francisco-ca

3 “Albany, CA.” 2021. Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/ albany-ca

4 Whole. 2013. The Carrie Diaries. The CW.

5 Gerwig, Greta, dir. 2017. Lady Bird. A24.

6 Hutchinson, Ray, Judith N. DeSena, and Susanne Frank. 2009. “Gender Trouble in Paradise: Suburbia Reconsidered.” Essay. In Gender in an Urban World. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 128.

7 Wekerle, 11.

teenage Carrie Bradshaw attempting to leave her suburban Connecticut hometown for New York City. The film Lady Bird5portrays a similar plot except that Sacramento, California is the suburban town that Lady Bird is attempting to rid herself of in favor of New York City. This view of suburbia as being detrimental to the growth of women spans multiple disciplines, including that of urban sociology. In research on women in suburbs, the suburb is often presented as an urban form that is the antithesis of modern feminism; something to be escaped. In “Gender Trouble in Paradise: Suburbia Reconsidered,” Susanne Frank explains that the concept of suburbia as “a place which casts the women’s social subordination… belongs to today’s unquestioned basic assumptions of critical and feminist urban studies”.6 Frank touches on the fact that, in the word of urban scholarship, the suburban environment as a stunting force for women has been universally accepted. This notion has cemented the perception of suburbia as limiting for women both in research and in popular culture. While the suburb is depicted as an oppressive force for women, the city is presented as a place of opportunity. In “A Woman’s Place is in the City,” Gerda Wekerle states that there is a demand by women for services such as daycares, places of employment, social service offices, and community centers “that can only be found in cities”.7 The idea that these services only exist in cities is compounded by the idea that they are more accessible in cities because public transportation is not prominent in suburban areas. Together, this creates the perception that women will be left without access to key services such as childcare or employment should they live in the suburbs. In past urban research, the city for women is a place for them to reach key services and social institutions that are thought to be unavailable in suburban regions.Although this picture of the suburb as an entity disconnected from the city and its networks may once have been accurate, today the suburb presents many benefits for women that it is typically not given credit for.

A prominent criticism of suburban life is that it physically isolates women and binds them to their homes. This view emerged at the beginning of the suburban housing trend when the cities were designed for working men who commuted and it was less common for women to have a license or own a car. The design of the suburbs lacked consideration for the needs of the women, whose lives at the time were centered around the home. Suburbs during the mid-to-late 1900s were designed for “homebound women”8 and “constrain[ed] women physically”.9 While this viewpoint is applicable to a specific time in the history of suburbia, new upwards trends in both car ownership and the number of women who have licenses makes this criticism less applicable to the present-day suburb. In 2014, it was found that “the number of women with driving licenses (DL) in the U.S. overtook that of men”10 in “all age groups greater than 25”.11 Women’s increased access to cars expanded opportunities for suburban women regarding their way of life.12 Women have previously faced isolation due to a lack of access to transportation in the suburbs. However, women’s increased use of automobiles today means they experience a higher degree of mobility; suburban women are no longer confined to their homes. When comparing the car ownership patterns in San Francisco and Albany, it is found that the average car per household is two in Albany13 and one in San Francisco.14 Residents of San Francisco are more likely than people in Albany to rely on the public transportation system; a system that is non-congruent with the needs of many women.

Women often take multiple trips during the day to drop kids off at school or daycare, run errands, and go to work.15 Not only does this mean that women are having to get on and off public transportation with strollers and multiple bags of shopping, but it also means that they are paying the fare multiple times per day. This is not the only way women pay for their public transit use; the term “pink tax”16 refers to the fact that women experience fear for their safety using public

transportation and pay monetarily for this fear through their increased usage of private car services such as taxis and Ubers. In The San Francisco Examiner article “Women say ‘pink tax’ in SF transit all too real,” the co-chair of the San Francisco Women’s Political Committee, Kelly Groth, recounts being “grabbed from behind”17 after exiting the bus at a stop near her apartment. The same article conducted an informal poll and found that women were spending money on car services to avoid taking public transit at night.18 Experiences like this point to the fact that public transportation in the city of San Francisco is not designed to meet the needs of women. Furthermore, public transportation offers less flexibility and mobility than a private automobile: “A heavy dependence on public transportation means that women’s job choices are more limited and the journey to work is more time consuming”.19

Today, the prevalence of car ownership in the suburb allows women to access a wider range of services such as employment opportunities. It also allows them to spend less time commuting. This contrasts with the previous view of the suburbs as limiting women’s mobility. Suburbs are not only

8 Hayden, D. 1980. “What Would A Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work.” Signs, S170–S187. doi:http://www.jstor. org/stable/3173814 S171.

9 Hayden, S171.

10 Singh, S. 2014. “Women in Cars: Overtaking Men on the Fast Lane.” Forbes, May 23. https://www.forbes. com/sites/sarwantsingh/2014/05/23/women-in-cars overtaking-men-on-the-fast-lane/?sh=364d481468d2

11 Singh, 2014.

12 Frank, 134.

13 Data USA, 2021.

14 Data USA, 2021.

15 Filkobski, Ina. 2022. “Gender.” SOCI 222 Lecture presented at the SOCI 222, November 1.

16 Rodriguez, J. 2018. “Women Say ‘Pink Tax’ in SF Transit All Too Real.” SF Examiner, November 21.

17 Rodriguez, 2018.

18 Rodriguez, 2018.

19 Wekerle, 12.

perceived as physically isolating women, but also as socially isolating. Harry Hiller writes that housewives in the suburbs in the 1960s “were thought to be isolated and lone, cut off from traditional kinship and community ties”.20 The view of women as lacking ties to their community and as being lonely in their suburban lives was found to be untrue even in the 1950s and 1960s: “many women continued their social and political engagement even after leaving the city”.21 Although suburbs are characterized as isolating, there are still many opportunities for women to socialize and engage with their environment. In Albany, the smaller community means many informal groups organize themselves. On Madison Avenue, just off Solano Avenue, Brenda hosts a book club that meets once a week to talk over a glass of wine. Albany Bulb, where Solano ends and the beach begins, is known for hosting many dog walks or beach clean ups organized by members of the community. Although there are more formal social institutions in San Francisco, there are still many informal ways in Albany for women to gather and participate in their community. Another instance of community organization in Albany occurs on National Night Out, a day in the United States where neighborhoods host parties to socialize with their community. In Albany, the community hosts block parties organized amongst neighbors. In contrast, National Night Out parties in San Francisco are organized by formal institutions; they occur in parks or in community spaces.22

As can be seen in the case of National Night Out, the community ties in Albany can be more stronger due to the smaller population size and more direct community involvement. In “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” Louis Wirth characterizes relations in urban life as containing “superficiality,” “anonymity,” and a “transitory character”.23 Wirth touches on the fact that individuals in the city may meet a higher volume of people in their daily interactions, but these interactions lack meaning. Hiller explains Wirth’s theories using the notion of secondary relations, which are “fleeting exchanges between strangers or routine instrumental interactions”24 that render urban residents “incapable of developing deep, personal connections”. Although Wirth’s theories may verge on the extreme, they still point out a key difference for women between socializing in San Francisco and in Albany. While the San Franciscan may see the same barista every day, a resident of Albany is more likely to run into a friend while out running

errands or form a close bond with their neighbors. The high volume of people in the city has also been equated with a diversity that exists in the city but is lacking in the suburbs. However, in the present day, a variety of residents live in the suburbs. Hiller writes that “today’s suburbs are also more diverse than they have ever been, with dual worker households, aging populations, single parents, non-family households, multi-generational families, and ethnic enclaves”.25 Albany reflects this trend with racial and ethnic diversity—the largest groups being White, Asian, and Multi-Racial—and a variety of different family compositions.26 On Madison Avenue in Albany, there is a house of college students, a woman living alone with her teenage daughter, and a young married couple who just had their second child. Today, suburbs are more diverse than ever, meaning women can feel comfortable living their lifestyle of preference and are offered a multitude of opportunities to develop meaningful community ties.

Suburbs have been condemned for lacking essential services for women such as those for work, raising children, and running errands.27 Although commuting from the suburb to the city for employment was once common practice, more employment opportunities have relocated to the suburbs. In her study focusing on the San Francisco Bay Area, Kristin Nelson examines “the process of relocating so-called subordinate office and administration activities from cities to the suburbs for reasons of reducing costs”.28 This process has been labeled “the third and most mature wave of suburbanization”.29 Many services and jobs are now present in suburban areas previously disjointed from the physical job market. This shift was beneficial to the suburban woman: “the decentralization of back offices also helped to systematically access the sought-after pool of a female workforce which had not been available beforehand due to socio-spatial isolation”.30 Although San Francisco hosts a bustling tech job market, Albany offers its fair share of employment opportunities; for example, law offices, architecture firms, and contracting firms. In addition to employment opportunities, Albany has many options for childcare, an essential service for women in the workforce. Albany has many daycares and preschools, three elementary schools, one middle school, and two high schools.31 There are also a variety of options for consumers, including both retail needs and food shopping. Despite previous criticisms of the suburbs lacking essential services for women, present day Albany offers a large variety of services for employment, childcare, consumption, and education.

20 Hiller, Harry H., 2014. “Gender and the City.” Essay. In Urban Canada. Don Mills, Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press, 93. 21 Frank, 133.

22 “12 Different ‘National Night out’ Sf Block Parties & Free Bbqs.” 2022. SF Fun and Cheap https://sf.funcheap.com/12-nationalnight-sf-block parties-free-bbqs-2022/.

23 Wirth, Louis. 1938. “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” American Journal of Sociology 44 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1086/217913, 12.

24 Hiller, Harry H., 2014. “Social Ties and Community in Urban Places.” Essay. In Urban Canada. Don Mills, Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press, 91.

25 Hiller, 239.

26 Data USA, 2021.

27 Wekerle, 11.

28 Frank, 139.

29 Lewis, Paul George. 1996. Shaping Suburbia: How Political Institutions Organize Urban Development. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press, 6.

30 Frank, 140.

31 “Albany Unified School District Home.” 2023. Albany Unified School District. Accessed March 13. https://www.ausdk12.org/

While the inclusion of essential services ameliorated the experience of suburban life for women, there are still lingering challenges surrounding inequities in urban spaces. There is a lack of consideration for women’s urban experiences in city planning, leading to a disconnect between the design of the city and how women use the urban space. This affects not only suburbs but spans all levels of urban forms, from the smallest village to the largest city. As a result, women must struggle with their urban environment or find ways to adapt to inadequacies. In order to create more inclusive and accessible urban spaces, it is crucial to include women in the planning process and to design spaces that are oriented towards integrating women seamlessly into their urban communities.

References

“12 Different ‘National Night out’ Sf Block Parties & Free Bbqs.” 2022. SF Fun and Cheap https://sf.funcheap.com/12-national-night-sf-block parties-free-bbqs-2022/

“Albany Unified School District Home.” 2023. Albany Unified School District. Accessed March 13. https://www.ausdk12.org/.

“Albany, CA.” 2021. Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/albany-ca.

Filkobski, Ina. 2022. “Gender.” SOCI 222. Lecture presented at the SOCI 222, November 1.

Gerwig, Greta, dir. 2017. Lady Bird. A24.

Hayden, D. 1980. “What Would A Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work.” Signs, S170–S187. doi:http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173814

Hiller, Harry H., 2014. “Social Ties and Community in Urban Places.” Essay. In Urban Canada Don Mills, Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Hiller, Harry H., 2014. “Gender and the City.” Essay. In Urban Canada. Don Mills, Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Hutchinson, Ray, Judith N. DeSena, and Susanne Frank. 2009. “Gender Trouble in Paradise: Suburbia Reconsidered.” Essay. In Gender in an Urban World. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Lewis, Paul George. 1996. Shaping Suburbia: How Political Institutions Organize Urban Development. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rodriguez, J. 2018. “Women Say ‘Pink Tax’ in SF Transit All Too Real.” SF Examiner, November 21. “San Francisco, CA.” 2021. Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/san francisco-ca.

Scott, Allen J., Michael Storper, and K Nelson. 1988. “Labor Demand, Labor Supply and the Suburbanization of Low-Wage Office Work.” Essay. In Production, Work, Territory: The Geographical Anatomy of Industrial Capitalism, 149–71. Boston, Massachusettes : Allen and Unwin.

Singh, S. 2014. “Women in Cars: Overtaking Men on the Fast Lane.” Forbes, May 23. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarwantsingh/2014/05/23/women-in-cars-overtaking-men-onthe-fast-lane/?sh=364d481468d2

Wekerle, G. 2006. “A Woman’s Place Is in the City.” Antipode. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.1984. tb00069.x.

Whole. 2013. The Carrie Diaries. The CW.

Wirth, Louis. 1938. “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” American Journal of Sociology 44 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1086/217913.

Abstract

Puerto Rico today is an island in shambles. Despite enduring multiple tropical storms every year, the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona—which made landfall in September 2022—demonstrates that the severity of the situation is beyond the impacts of a natural disaster. Although it was designated as Category 1, the mildest ranking, the storm caused lasting damage throughout the island, devastating people who still face power outages, a lack of clean water, and other challenges months later. Though the United States (US) government may be quick to blame Puerto Ricans on their precarious situation, this paper examines the variety of historical factors that have shaped the island’s current trajectory. Using dependency theory and subalternity

as a theoretical framework, I argue that US intervention supporting corporate interests has entrenched Puerto Rico in dependent-oriented development at Puerto Ricans’ expense. Nonetheless, despite their status as second-class citizens of the US, they continue to fight valiantly against their oppressor with the hope that their voices may one day be heard.

Keywords: Puerto Rico, Dependency Theory, Subaltern, Hurricane Fiona, colonisation, LUMA.

On a cloudy day, a virtuous white woman sails over a crowd of pioneers. Working the land and expelling its previous inhabitants, they act on her behalf, for she is the symbol of fortune and destiny. Shining light on the path ahead, she frames the title for the painting in which she stars: American Progress (see Figure 1). This work represents a period of change for the US. Idealizing the word of President James Monroe, whose 1823 Doctrine declared that the US would seek to defeat and replace European influence in the Western Hemisphere, the painting depicts America as a global superpower through the angelic woman who commands her people and relinquishes those that stand before her.1 She represents the concept of Manifest Destiny, an extension of the Monroe Doctrine that idealizes America as a “chosen people” who represent a force for good that must be spread.2 At the time of this painting, Spain’s influence was declining throughout the Western Hemisphere, providing the perfect opportunity for US expansion into the region—part of its campaign to become a global hegemon. By 1898, the US had won the Spanish-American war and gained control of key territories, including Puerto Rico. However, rather than helping the native Taínos sustain themselves, Americans developed the island through the colonizer’s model of the world.3 As such, “Puerto Rico had been invented: a tropical island in the Caribbean Sea,” meant to support American imperialism throughout capitalist development.4 Any contestation of the commercial and utilitarian agenda for the island went on deaf ears, only to be heard when beneficial to the colonizer.