2

3

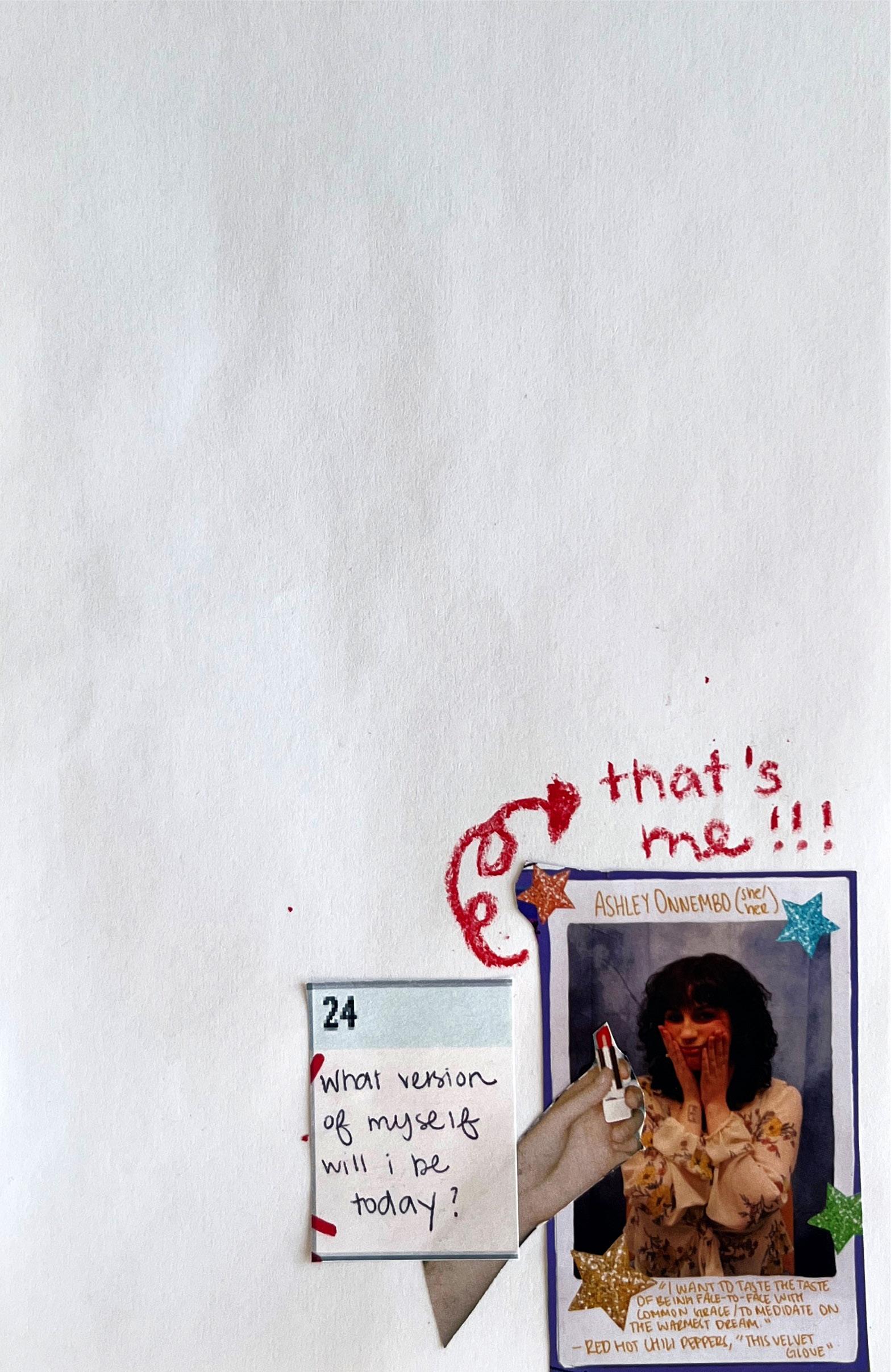

10 years of Five Cent Sound. The magnitude of this sentence is enough to make my whole body shudder. I mull over the ebbs and flows of this magazine since its inception, shouldering a fraction of its evolution and conceptualizing the rest of it.

To grapple with this rift in time, I close my eyes and try to conjure an image of myself at 12 years old. I can’t seem to capture her face in my mind’s eye or recollect the tonalities of her prepubescent voice; I struggle to pinpoint what philosophies she believed in wholeheartedly or the snacks she would reach for without second thought.

It agonizes me to admit how far removed these respective versions of myself are from one another. When I’ve traversed down the rabbit hole of my own contemplation deep enough, I wonder if Five Cent Sound feels the same way that I do: isn’t that the double edge sword of an expansive metamorphosis sprawling across separate semesters? Change is only inevitable, but there is one thing that relates all the voices of Five Cent Sound together (and on an individual level, the younger version of myself): music.

Our collective ability to cherish and connect to a medium so deeply withstands any passage of time. Just like I did in seventh grade, I gravitate towards darkened rooms where my senses are heightened to pulsating vibrations and intricate phrasings. The coos of my favorite artists wrap around me tighter than the warmth of the world’s fluffiest blanket ever could. The muscles of my horizontal body soften as cascading layers of instruments bounce back and forth

between my ears. I am lulled into different worlds and pieces of myself.

I listen to music to indulge in the intensity of an emotion — it’s even empowered me to cheat my way through life, an artist’s words inviting me into circumstances and feelings I have yet to experience firsthand. Whenever I want to recoil in romance and reverb, I queue “Love Songs on the Radio” by Mojave 3. “Forest Lawn” by Better Oblivion Community Center is my celebratory mark to yet another tired triumph. The shimmering guitar chords descending out of “Chop Suey!”’s crashing chorus elicits a petulance harsher than teenage angst, encouraging the stubborn child ingrained in my soul to beam with satisfaction. On days I feel particularly lonely or curious, I remind myself of how individual yet vastly universal music can be.

Five Cent Sound exists to toe this exact line. The magazine bands the music community at Emerson College together, all united by a shared habit to reach for our headphones as a way to navigate and express our love for a city characterized by noise. The subjects inspiring us to create and our headstrong opinions over the years dance circles around each other. Time and time again we crawl back to Five Cent Sound to fulfill a fantasy of being Anthony Fantano or Cameron Crowe. It fills up our lungs as much as it takes the wind out of them, yet generations of writers and readers and creatives continually rely on the outlet to unapologetically rave about music, our shouts resounding through a niche abyss.

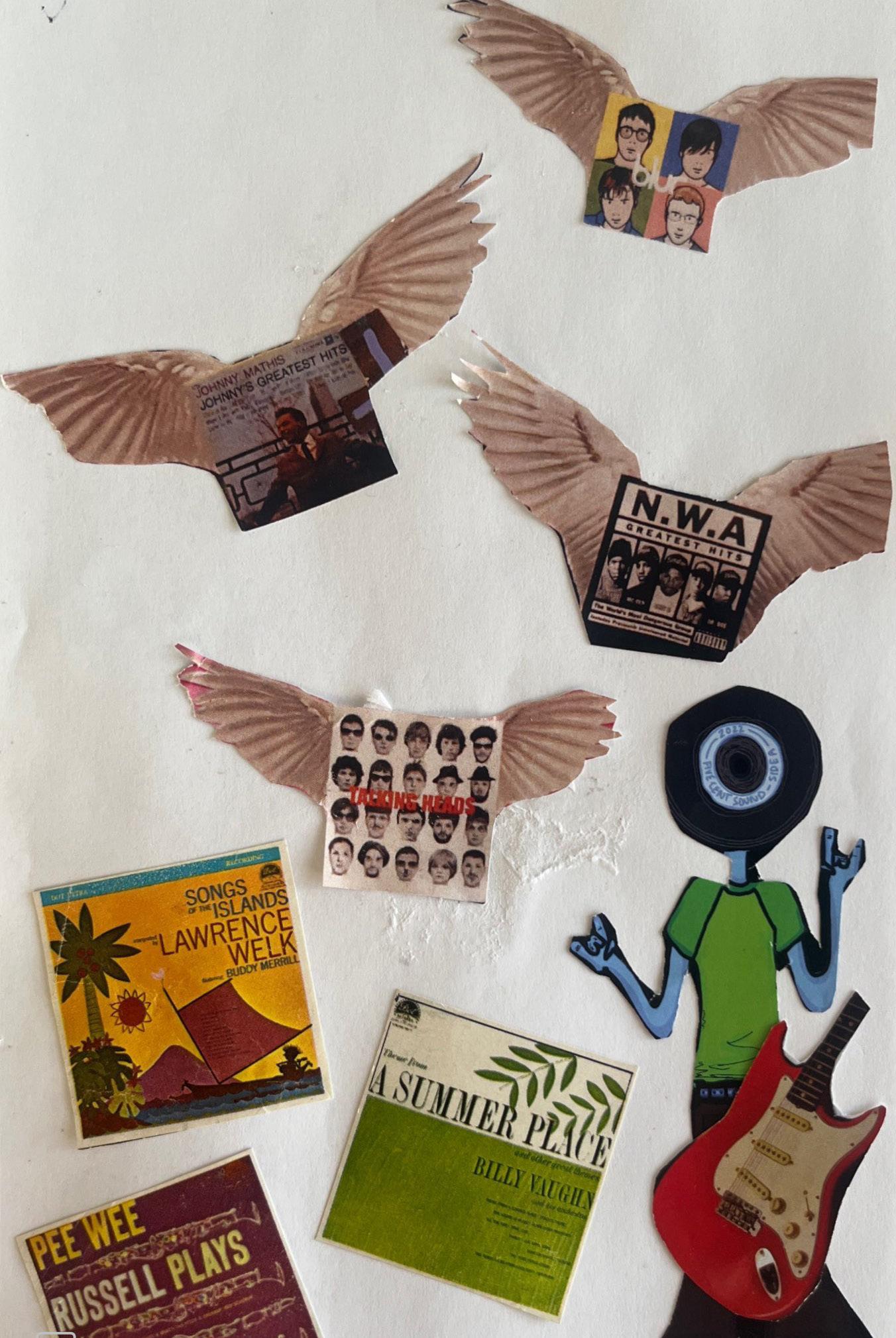

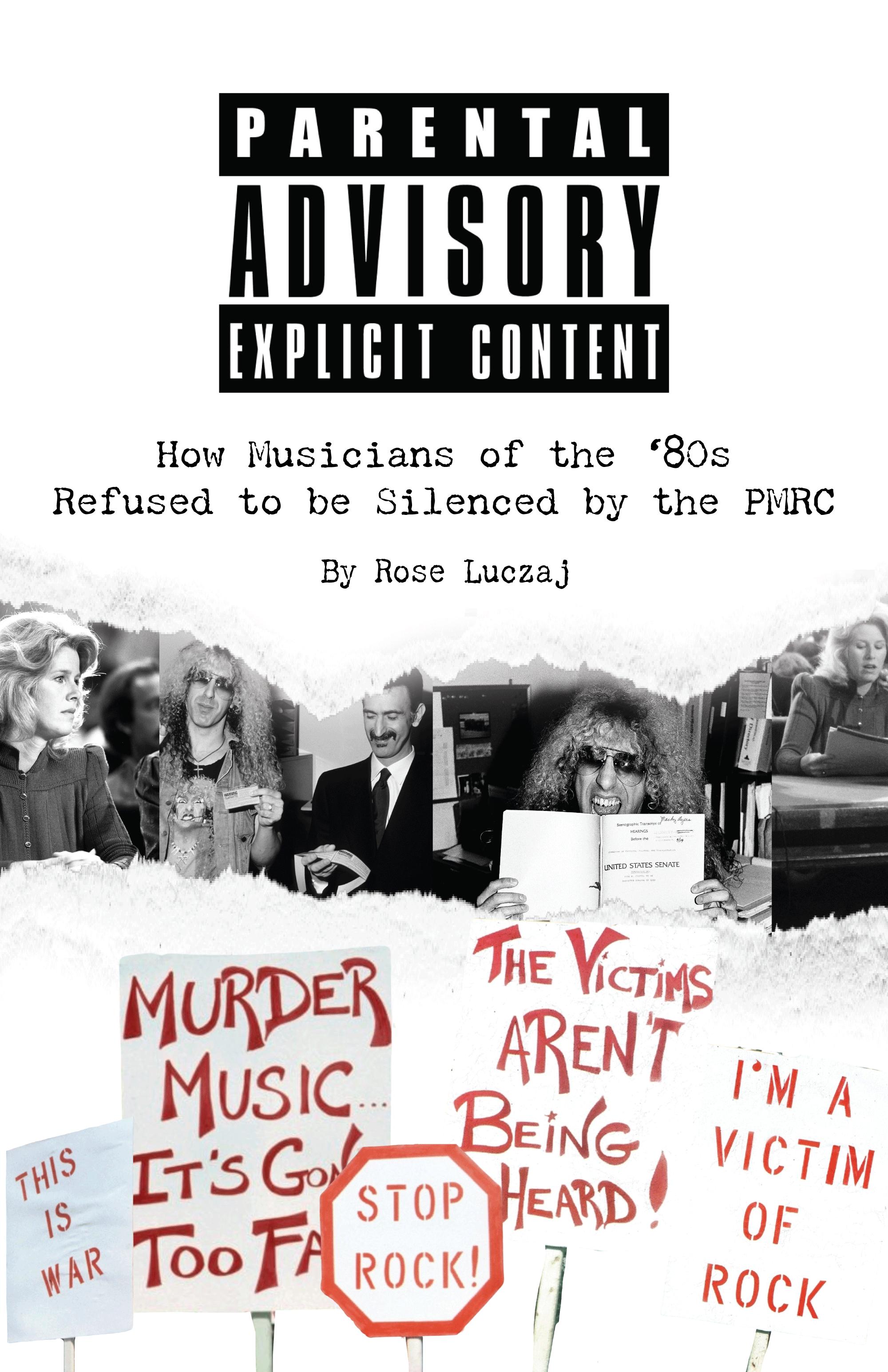

For our tenth anniversary issue, we wanted to unpack how music relates to our connotations of the past, present, and future. Various collages reimagining the artwork and articles featured in our print issues over the past 10 years span throughout the magazine as a way to pay homage to the array of creatives who have graced this publication. We hope this body of work inspires you to delve into the relationship between music and time, dissecting its ability to represent our personalities and speak to the history and culture of society at any given period.

I think of what Five Cent Sound accomplished in 10 years time and how that image will persist and mature with another decade passed. I can’t imagine myself at 32, but I do know

7

the passion of this magazine will live on within me forever. It’s hard for me to let go of something so formative to the fibers of my being, a project I have nourished to a point of worrying and speculating about the lifespan of the publication as if it is a child of my own. I owe so many pieces essential to the mosaic of myself to this magazine and am eternally indebted t to an opportunity that exposed me to so many beautiful minds, examples of taste and the endless possibilities of talent.

To Five Cent, thank you for letting me stand in your sound, even if for just a little while. I’ll close the door but not all the way, leaving a sliver of room to glimpse in on those who have yet to barrel through the hinges.

where anything goes and creativity flows

Editorial

Staff Masthead

Executive Board

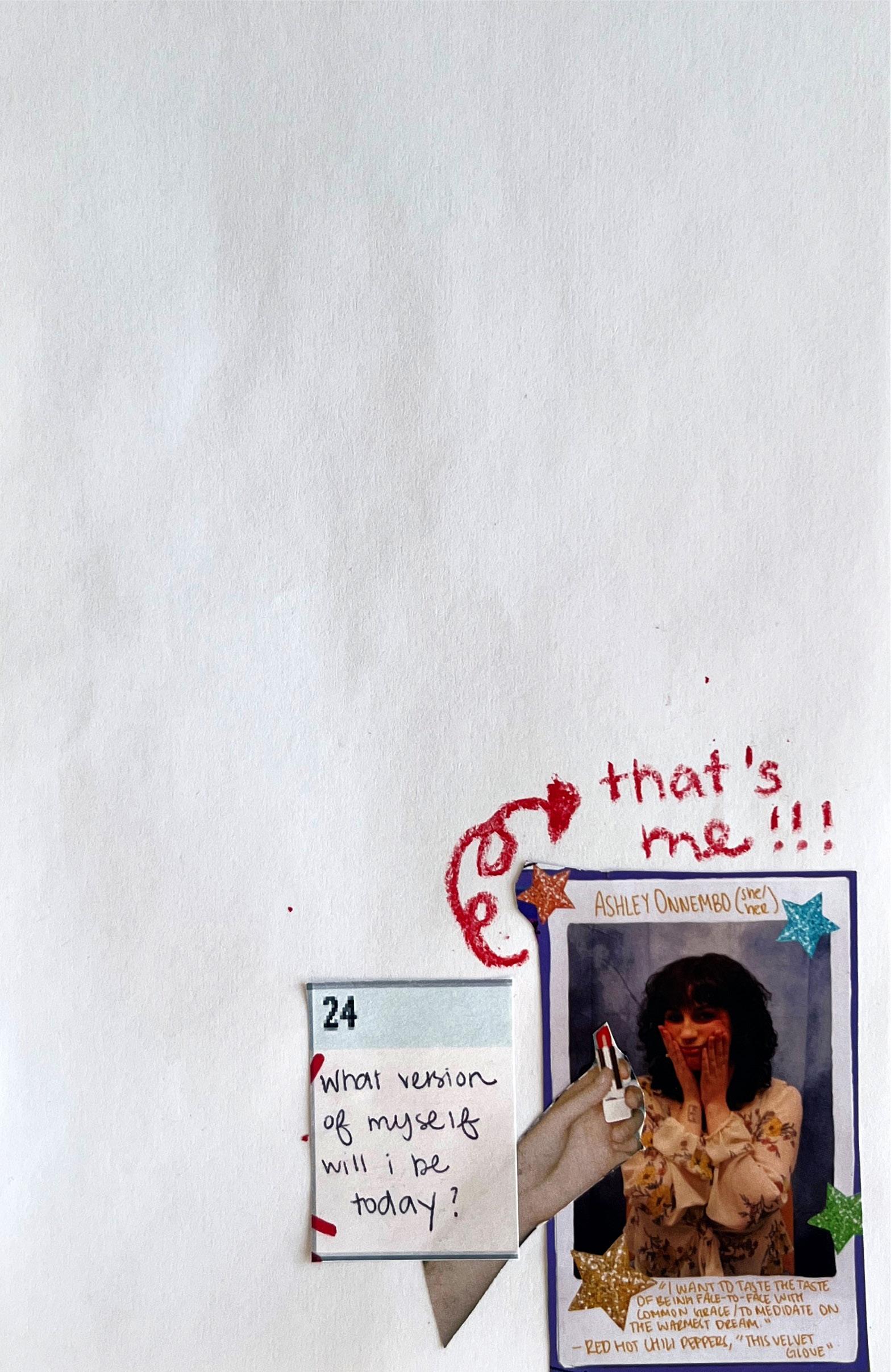

Editor-in-Chief // Ashley Onnembo

Managing Editor // Paulina Subia

Creative Director // Ali Madsen

Assistant EIC // Abby Stanicek

Assistant CD // Quinn Donnelly

Head Online Director // Alexa Maddi

General Editors

Jess Ferguson

Thomas Fienan

Brooke Huffman

Alexa Maddi

Claire Moriarty

Abby Stanicek

Diversity and Inclusion Editors

Minna Abdel-Gawad

Daphne Bryant

Sydney Johnson

Shiyang Shao

Copyeditors

Head: Chelsea Gibbons

Sophie Hartstein

Emma Shacochis

Rebecca Zaharia

Creative

Christina Casper

Bella Cubba

Ashley Davis

Samantha Deras

Emma Doherty

Quinn Donnelly

Mo Krueger

Rose Luczaj

Ali Madsen

Ashley Onnembo

Anya Perel-Arkin

Micki Porcaro

Olivia Tran

and many more online !!

OUR (FIVE) CENTS

Nothing More Punk Than An Aerobics Class

By Lucy Spangler // 12

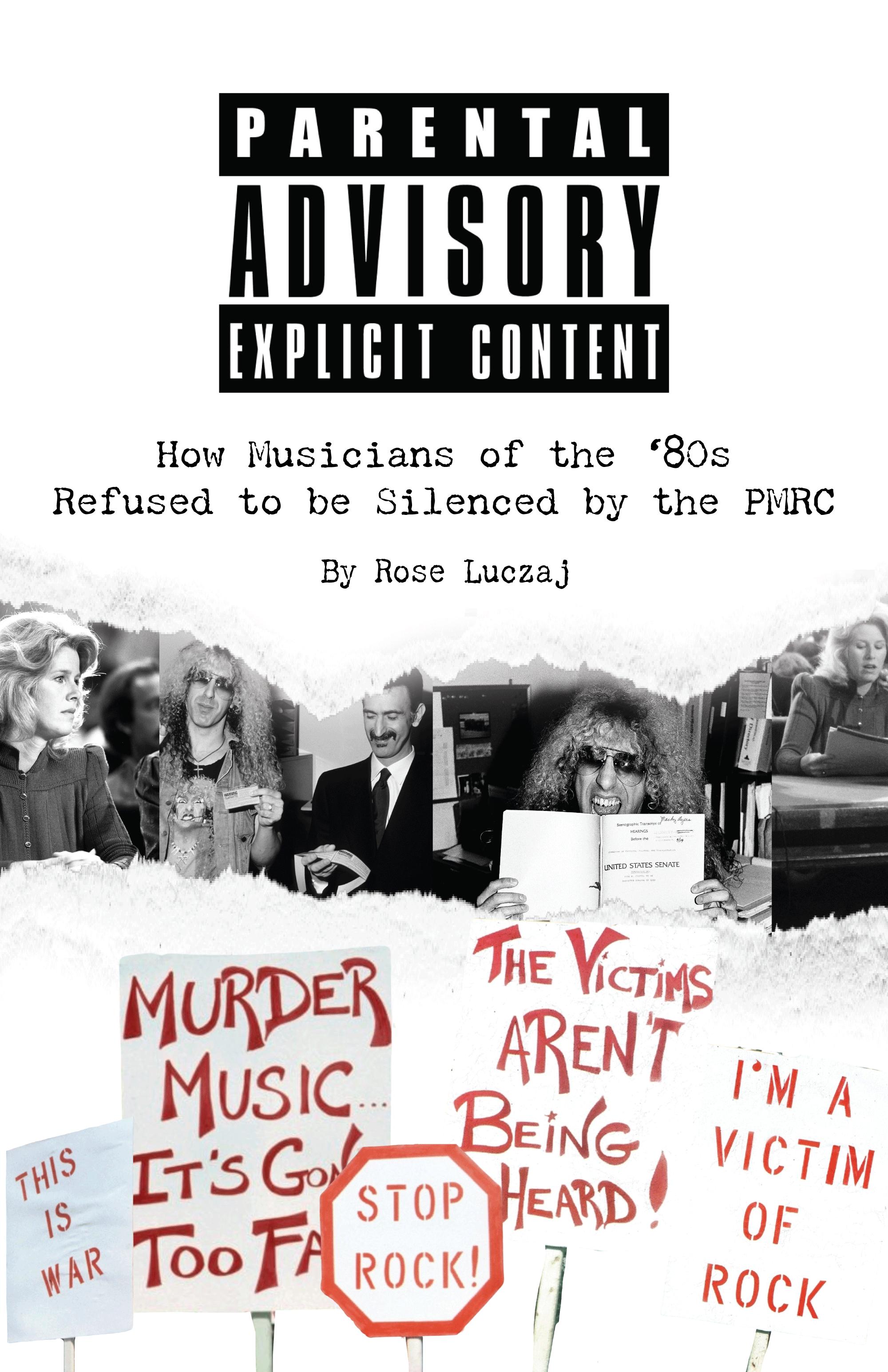

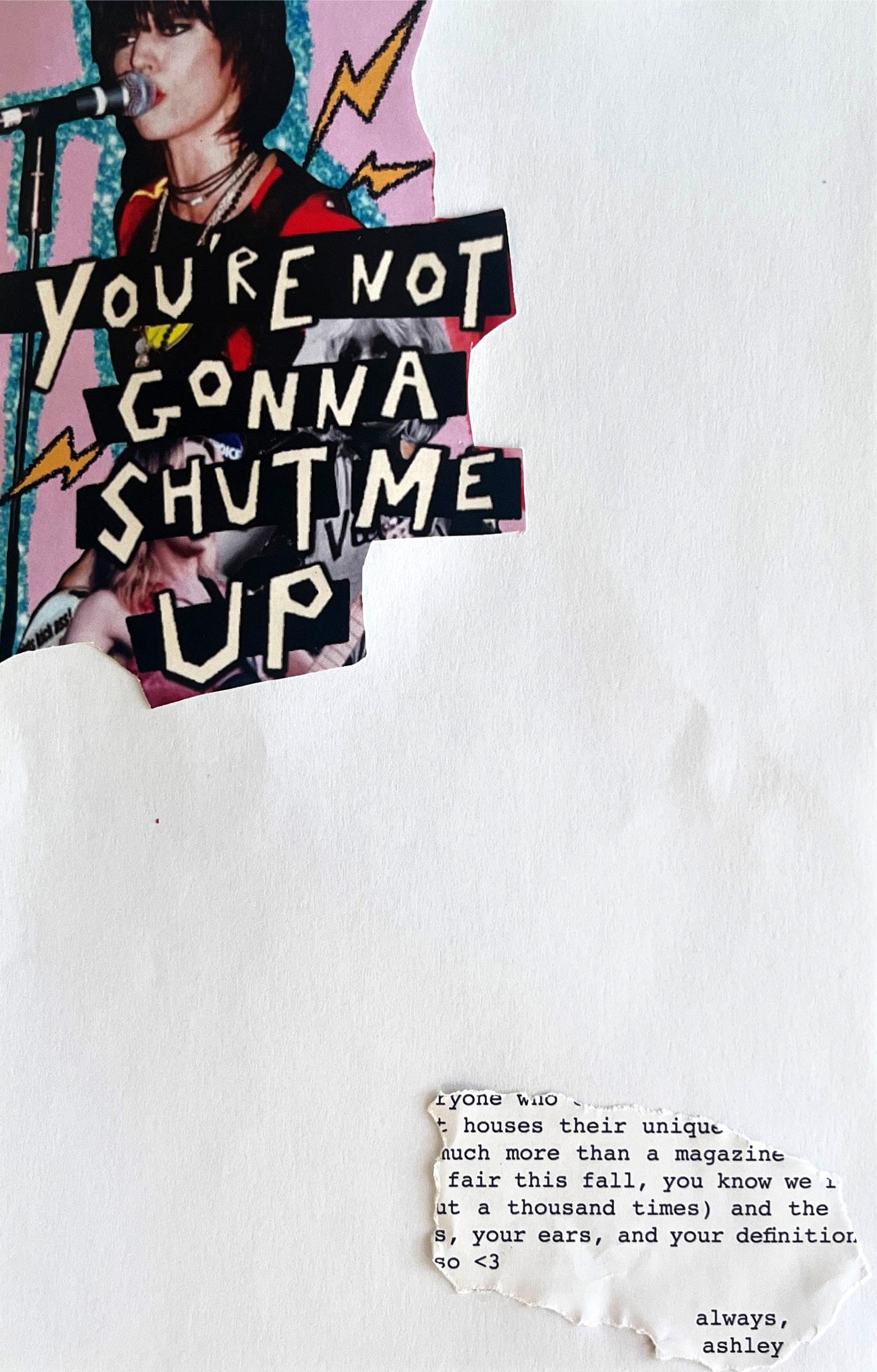

Parental Advisory: How Musicians of the ’80s Refused to be Silenced by the PMRC

By Rose Luczaj //

16

Been There, Heard That

By Nathan Hilyard //

22

The Night-and Day-core of Viral Edits

By Jules Saggio //

29

Electronic Sounds in the Electronic Age

By Basia Siwek //

33

E is for Eyeliner: the ABCs of Emo

By Dionna Santucci // 37

Mario Mood Music: A Deep-Dive into Gaming’s MostInfluential Soundtrack

By Rebecca Zaharia //

Who is Broadway For?

By Daphne Bryant // 53

45

This Is It: An Interview with Gordon Raphael

By Paulina Subia // 58

The Color of Music

By Lily Price // 70

Evergreen Music and the Resurgence of the ’70s

By Minna Abdel-Gawad // 79

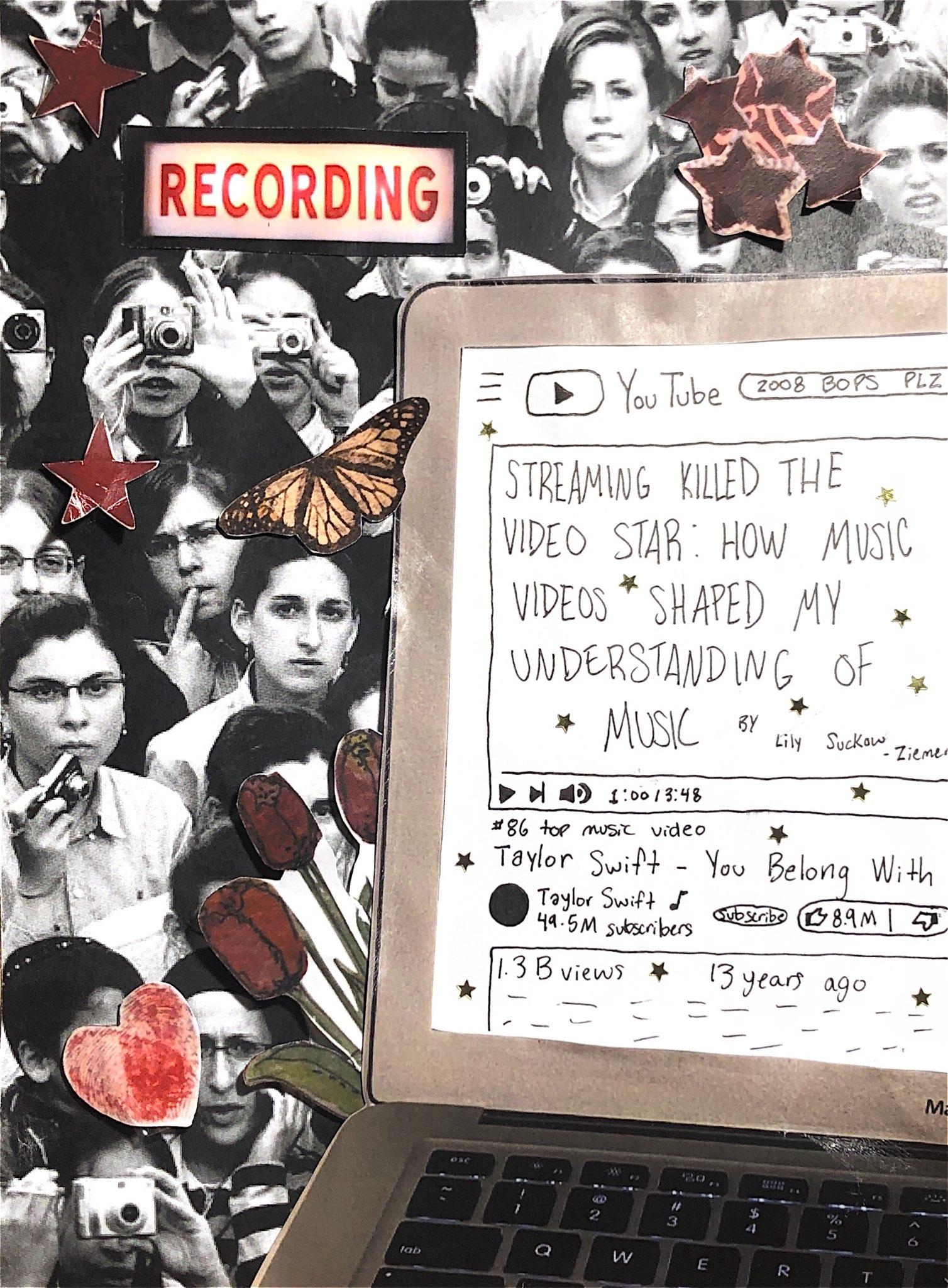

Streaming Killed the Video Star: How Music Videos Shaped My Understanding of Music

By Lily Suckow Ziemer //83

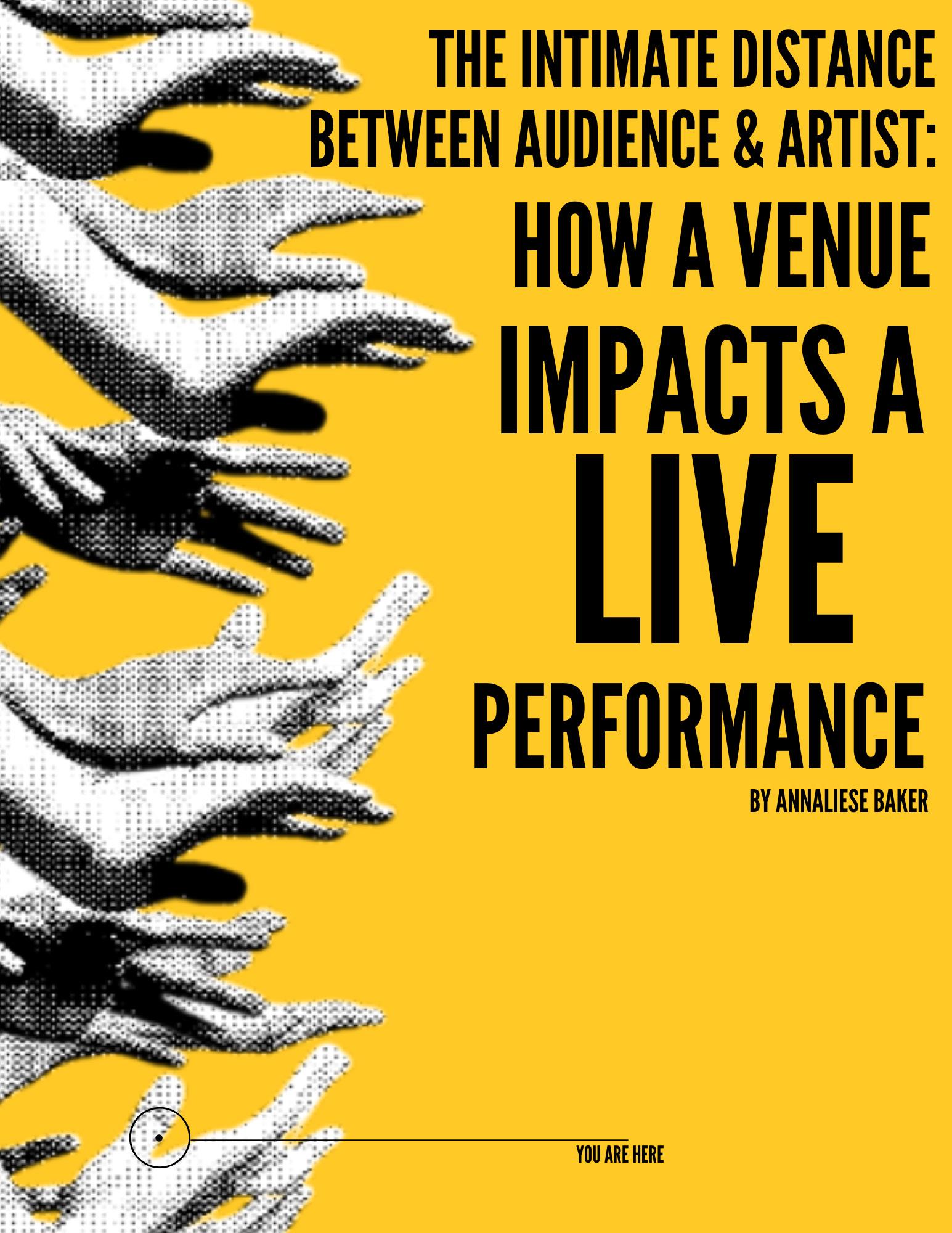

The Intimate Distance Between Audience & Artist: A Study of How a Venue Impacts a Live Performance

By Annaliese Baker //89

The Goat Testicle Implanting Doctor Who Changed Country Music Forever

By Ivy Schulte // 94

How My Parents’ High School Reunion Mixtapes Formed My Music Taste

By Abby Stanicek // 98

Gaze Into the Void, and Your Music Might Gaze Back

By Claire Moriarty // 103

When people asked Johnny Rotten why the Sex Pistols formed, he said it was because “we were sick of all the same old crap and we wanted to do our own thing like any decent human should.” Punk typically draws associations to anarchy or destruction, so the core idea of creating something that fosters a community of likeminded people and outlasts those who established it is overlooked. Punk is really about creating something for misfits, for people who felt like nothing existed for them.

This idea is the crux of what Punk Rock Aerobics co-founder Hilken Mancini wants people to get out of her classes. “Punk Rock Aerobics was created for the misfit, it was created for people who didn’t want to feel like they have to fit into a certain way of being, any category, size or shape,” says Mancini. Following the same structure that formed the Sex Pistols, the class created something that hadn’t been offered to anyone before. And by doing that, they founded a community of people who just want to “show up in their Chuck Taylors and let their freak flag fly, and the music doesn’t suck.”

I was introduced to Punk Rock Aerobics when my dad got tapped to DJ a session and brought me along to take the class. I grew up on punk music, having it spoon fed to me by my parents from the moment I had working ears. Once the first song started playing and Mancini started calling out instructions, I got instantly transported into my kitchen back home, to when my dad would play The Slits on a Saturday night after dinner and my brother and I would throw ourselves around until we almost hurled up our food.

I definitely felt the burn from this class the day after, but the pain couldn’t detract from the reward of trekking out to Jamaica Plain — I could only replay how Manchini weaved between the racks of clothes in her store, her words awakening the creative power of the counterculture within me.

Mancini bought the domain for Punk Rock Aerobics in 2000 with the goal of making the classes a safe space. Sessions take place in both the Greater Boston area and

13

New York, all the while dodging franchisement and sticking to their DIY approach. Music and attitudes aren’t the only aspects of punk that the class draws on: many of the moves reference punk iconography, such as “Never Mind the Buttocks,” a play on the Sex Pistol’s debut album; “The Skank” transcend beyond the pit and iconic cover art of Circle Jerk’s Live at the House of Blues. In 2021, Mancini brought the steps of Punk Rock Aerobics to the screen when producing the music video for Green Day’s single, “Here Comes the Shock.”

According to Mancini, it was never about “making it” when it came to Punk Rock Aerobics. The goal aimed to do something new that wasn’t available to people at the time, and through that, form a community. This mindset is commonplace when it comes to the Boston DIY music scene, a city known mainly for institutions and less for its artists. Musicians in Boston develop a “thick skin,” as she puts it.

“Boston [music scene] has never been monetarily driven,” says Mancini. “If you stay here and you do music, you know you’re never going to make money. You do it because you fucking love it.”

Mancini’s most recognizable contribution to the Boston music scene is the band Fuzzy, which formed in the early ’90s and released their first album in 1993. Currently, she plays guitar for The Monsignors.

“It was a snowstorm, but people would still come and see your show,” recounts Mancini. “It was a community and you can’t buy that. You can’t get that in cities like LA and New York. That’s why I love staying in Boston: it was about the music, supporting each other and developing a community, which is what makes me happy.”

Mancini is always very consciously aware of what her impact and role within this Boston community is and where she can make improvements. One of these improvements stemmed from her experience as a woman involved in the scene. By no means did Boston lack talented female musicians in the 1990s. However, an underlying sense that they existed as a novelty act in a space they should’ve been embraced did.

14

While touring the country with her band Fuzzy, Mancini dealt with everything from passive aggressive comments during soundcheck to being mistaken for a sex worker.

“You’re playing out of those loud amps? I thought you were the singer,” mimics Mancini. “Are you fucking kidding me? No, this is my fucking Marshall stack. It’s 100 watt and I’m playing it really fucking loud. Does it matter that I have a vagina?”

In response to this, Mancini created a nonprofit called “Girls Rock Camp,” an organization dedicated to promoting self-esteem and confidence in girls playing rock music. She recalls how women always upheld the standard of sticking together within the scene, whether it was stepping up to fill in on bass when a band member got sick or showing support to each other’s endeavors.

The common through line between all of these experiences traces back to Johnny Rotten’s words. Punk is so often associated with the destruction of social norms. But what gets neglected when we talk about the history of punk music is the communities that sprang out of the norms it raged against. This cycle is fully on display in the creation of Punk Rock Aerobics and Girls Rock Camp: rejection of the norm, the desire and creative spirit to try and make something new and the community that forms around an idea they didn’t know they needed.

15

“We were in creem magazine, and on the cover it said “Women in Rock” -- you just felt sick to your stomach,” describes mancini. “All these women have been doing rock and roll forever. It’s not a new thing, it’s embarrassing.”

“Rock music destroys kids.”

“Will your child be the next victim?”

“Rock music: public enemy #1”

These phrases marked some of the absurdities that could be read on posters carried proudly by the herd of uniform-clad Catholic school children, planted outside the Senate hearings against rock music on September 19, 1985. On this momentous day in history, the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) successfully wormed their way onto the Senate floor and fought against the “devil’s music” in order to protect the nation’s vulnerable children from explicit music. Despite their requests being highly unconstitutional, they garnered a devout following that supported them throughout the hearings — until they didn’t.

In order to understand how all of the PMRC’s efforts came to a head on this fateful day nearly forty years ago, we need to go back to the very beginning of the organization, along with the four self-proclaimed “Washington Wives” who founded it. Susan Baker, Pam Howar and Sally Nevius came together under the leadership of the obstinate Tipper Gore, who felt outraged when she bought her young daughter a copy of Prince’s Purple Rain.

The album contained the provocative song “Darling Nikki,” which made frequent references to masturbation and other sexual content. Highly offended by the lyrics and frustrated by the lack of warning, Gore decided to found the PMRC. The group promptly released a list of the most explicit songs of the time, titled “The Filthy Fifteen” — of which “Darling Nikki” ranked at the top. The PMRC then went on to propose a list of demands to the United States Senate, which included making a rating system much like that of movies and requiring lyrics of explicit songs to be printed on the sleeves of records. This would allow for ample warning of edgy content by ensuring that no surprises hid from the public eye and hyperactive parents.

But here’s the catch: each of the four founding members of the PMRC held ties to prominent figures in Washington

17

D.C. at the time. Susan Baker was the wife of Treasury Secretary James Baker, Pam Howar was married to D.C. realtor Raymond Howar, and Sally Nevius was married to the former Washington City Council Chairman, John Nevius. And of course, Tipper Gore was the wife of Senator and future Vice President Al Gore.

“I always just thought it was political theater,” said Jay Jay French, co-founder and lead guitarist of Twisted Sister, whose 1984 hit “We’re Not Gonna Take It” had ended up on the Filthy Fifteen list. “Like, are they doing that because some statisticians said ‘You’ve got to do this for the next election’?”

The PMRC justified putting “We’re Not Gonna Take It” on the Filthy Fifteen list due to its message of inciting violence, speculating the track ridiculed their organization (even though it came out before their founding).

“The song was another Dee anthem for me. I mean, he writes them all the time,” French explained, speaking of his co-founder Dee Snider, who testified at the 1985 Senate hearings. “It was always an us against them, against the world.” The song never intended to soundtrack the movement against the PMRC, leading the band to oppose its unjust inclusion on the list.

As amused as French felt with the entire ordeal, Snider took a very different approach to the backlash against their music. Alongside progressive rock legend Frank Zappa and Americana artist John Denver, Dee Snider sat in front of the representatives of the Senate and preached about how morally upstanding all of the members of Twisted Sister actually were.

“The fact is [that] we just were businessmen working really hard,” says French of the band’s members. “We didn’t drink, we didn’t do drugs… We traveled in buses that said ‘no fun bus’ because you couldn’t smoke cigarettes on it… and the fact that we were attacked for some moral decay of America was ironic because we were probably the most moral band out there.” However, French did not want people to know that for commercial purposes, noting that “when Dee decided to proclaim his straightness, the record label was horrified that it was going to destroy our reputation.”

18

After Zappa, Denver and Snider’s testimonies — and a heated rebuttal from the PMRC representatives in front of what Zappa referred to as a “kangaroo court”— the ruling declared that the PMRC’s requests could not be met due to their violations of the First Amendment rights of the musicians behind the songs. Its outcome veered far from the victory most people thought the rock and roll community earned. Even though the PMRC’s demands weren’t legally satisfied by the Senate, Parental Advisory labels appear on the covers of albums today.

The Parental Advisory sticker sprung out of ulterior motives on behalf of the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA). The RIAA represents approximately 85 percent of all record labels in the United States, including Atlantic, Columbia and Motown, and is responsible for the majority of the commercial success of some of the biggest names in the music industry. However, the RIAA ran into some profiting issues due to the ability of consumers to create their own tapes on blank media. The RIAA pushed to pass H.R. 2911, known as the “Blank Tape Tax,” through to the Senate floor since May of 1985. Up to this point, they failed to capture the attention of the Senators. They decided the best way to get their act through would be to appease the wives of the Senators themselves — unfortunately, their instincts proved themselves correct.

The RIAA began to require all explicit content that they produced to include the labeled Parental Advisory sticker, using their stronghold over the entire music industry to meet the requests of the PMRC. Since artists feared for their careers if they did not adhere to the RIAA’s guidelines, most followed the rule, and thus the era of Parental Advisory: Explicit Content unfolded. The “Blank Tape Tax” passed later that same year.

Though many assumed this as a loss for artists’ rights everywhere, the musicians of the next decade and a half refused to let the Parental Advisory label deter them. They worked to redefine the label throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, transforming it from a mark of shame into a flag of notoriety through immense success.

20

Andre Howard, the head of commerce and digital at the independent music distribution company United Masters, explained the countercultural prominence of the Parental Advisory sticker: “It was making it not as accessible for people to buy it because stores didn’t want to pick it up [...] It also created the allure, right?... It’s like that Pandora’s Box — when they tell you not to open it, you want to.”

And open it they did. Throughout the ’90s, groups such as N.W.A. and 2 Live Crew skyrocketed in popularity despite the suppression of the Parental Advisory label. This also calls attention to the power of BIPOC creators in the industry and their ability to take something as taboo as the sticker and throw it back in the faces of the record executives that put it there to stifle them. Their resilience and persistence not only expanded upon the rebellious legacy of the rock icons from the ʼ80s but inspired many more groundbreaking artists for decades to come.

Today, explicit music is just another part of life that we deal with on a person-to-person basis. In an increasingly digital age, the importance of printed lyrics and a physical sticker on CDs is diminished. As for the PMRC, it lost most of its donations after the 1985 trials and faded into but a memory by the early 2000s.

21

“We’ve got the right to choose, and There ain’t no way we’ll lose it

This is our life, this is our song We’ll fight the powers that be, just Don’t pick on our destiny, ‘cause You don’t know us, you don’t belong”

~ “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” Twisted Sister (1984)

“Since I left you…,” begins the first few moments of the Avalanches’ 2000 debut album, “...I found the world so new.” The opening strains mix with a transplanted glamor of vintage vinyl and old Hollywood movies, whispering in and out through a reconstructed melody: “Welcome to paradise….” Since I Left You is an hour-long collage of songs compiled from roughly 900 samples, picked from piles of old media. The project represents one of the more devoted exercises in sampling, but serves as the perfect allegory for sampling as a concept.

Sampling, in its modern form, is the act of removing a piece of audio from its original position, and placing it into a new context. From its conception, sampling morphed into one of the most widely employed practices in both underground and mainstream music. From cult classic albums to one-of-a-kind DJ mixes and chart topping Hot 100 hits, sampling is the driving force behind the exchange of musical ideas; it serves as a vehicle for pulling former sounds into modern productions.

The first murmurs of sampling began to appear in 1940s Paris through “musique concréte,” a type of composition developed by French composer Pierre Schaeffer, which consists of the elaborate looping of found audio footage to create sound collages. Pieces were long and often shapeless, constructed from a wide array of sources and alluding to a life lived through noise. Through experimentation, musique concréte laid the intellectual and technological groundwork for sampling.

With the advent of more standardized sampling technology in the form of keyboards and monophonic digital samplers, the newest and soon-to-be most influential DJs and musicians began to experiment and develop the practice. Quickly, sampling became a staple in underground music circles, with producers and musicians using sampling as a vital tool in the creation and development of new genres like hip-hop, disco and dance.

Fast forward to the 2000s, and sampling settles into its position as one of the most widely-used tools in both music production and performance. In recent charts, many of the most prevalent pop songs feature some sort of sample, which begs the cyclical question: did the

23

music world evolve to a point where it’s too oversaturated with the practice?

Most primarily, sampling helps infuse a sense of comfort and nostalgia by pulling on past sounds listeners are familiar with. In one instance, Madonna revived a stagnant career with the chart topper “Hung Up,” which samples the equally as acclaimed “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” by Swedish music royalty ABBA. Listeners immediately click into the iconic opening riff, but in place of ABBA’s ’70s glam, Madonna infuses a thumping Y2K dance beat. The interpolation masterfully balances borrowing old sounds and developing them into the modern musical landscape and beyond.

Nearly 20 years past the release of “Hung Up,” Madonna continues to pull from the past when creating her new music, in particular with the new single, “Hung Up on Tokischa” featuring the Dominican rapper. The song spotlights some semblance of ABBA’s iconic riff, but now simplifies it to a referential bass line, with the majority of the song’s identity being the original “Hung Up” chorus infused with a Dominican beat. The song is cute — and at points, very fun — but it serves as a warning for sampling gone too far.

The song attempts to do to “Hung Up” what “Hung Up” once did to “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight).” In lieu of harvesting nostalgia, the song really only floats on the developments brought by Tokischa. And when Madonna joins the chorus with the classic “Hung Up” melody, she sticks out sorely from the rest of the piece. Madonna, in this way, dually exemplifies sampling as a successful method of infusing fresh songs with a classic nostalgia and sampling as a crutch which stunts creativity.

There is much to be said about some songs which are, in their own right, incredibly recognizable, and are then sampled and used as reference material for newer songs. Take the Italian Europop hit “Blue (Da Ba Dee)” by Eiffel 65, a song which gained quite a bit of global success upon initial release, but now remains recognizable for its annoyingly earworm-able melody. The song presented a perfect hit for European clubs: it’s danceable,

24

goofy and easy to sing along to. So, when modern artists attempt to use the song’s sounds, how can they find the most success?

Two songs in particular took an admirable stab at sampling it: in 2020, GFOTY released “By My Side” which features the melody of “Blue (Da Ba Dee)” amidst a mixture of glitchy production and the signature Europop beats. GFOTY’s interpolation of the original maintains the gluttonous melody then advanced through modern oddball productions. GFOTY’s use of the sample brings the melody from Italian clubs to the modern cooky-electronic realm, adding to the sonic experience while also pulling from the humor of the song to create a giggly, infectious track.

In an alternate example, Bebe Rexha and David Guetta recently released “I’m Good (Blue),” which also borrows “Blue (Da Ba Dee)”’s infamous melody. Rexha’s interpretation is much more literal and focused for release within the mainstream. “I’m Good (Blue)” removes much of the humor from the song and sticks close to a very radio-ready dance sound. While this results in a sonically fun experience, it still feels a bit tired. There is little expanse beyond the original fun of the Italian hit, and consequently the song does nothing to expand the sample. Where GFOTY developed the melody into a humorous advance into new dance sounds, Rexha and Guetta stick close to the original sound, and subsequently fail to pull the sample into newer progression.

Regardless of whether sampling is done well or poorly, the practice is essentially borrowing the creative work of another artist, therefore making it crucial to consider the social responsibility involved with sampling. Sampling is placing someone else’s work into a new sonic context; music, being inherently tied to culture, must be treated with care when moving between artists. Sampling has proved itself to be a vital form of musical communication and collaboration, helping to transplant ideas within different artists’ work. When the cycle continues and samples are separated farther and farther from the original artist (and, in many cases, culture) there is an inherent disrespect.

25

One album of hot debate over the past year is Rosalía’s tour-de-force of multi-cultural expression, Motomami. The album quickly rocketed to the top of global pop charts, taking a specific hold upon Spanish-speaking music markets, but a significant portion of listeners and critics expressed discomfort with Rosalía’s use of Latin American rhythms and aesthetics, as she is a natural born Spaniard. Motomami acts as an amalgam of references, taking inspiration from Disney ballads, bull fighting, her nephew, Asian cuisine, the sakura flower, motorcycles and many other sporadic sources, but the primary sonic experiment is a blend of flamenco, reggaeton and jazz through a danceable pop form.

Rosario Swanson, a professor of Latin American Literature & Culture at Emerson College, points to the commercial success that is key for pop musicians on both sides of the Atlantic.

“There has always been a ‘dialogue’ of influences between the two areas, Spain and Latin America, at the cultural level and also because of the significant markets each area represents for the other,” says Swanson. “I also don’t know how possible it is for sound not to travel across boundaries that were so fixed before. I am not saying that cultural appropriation is correct or anything of that sort, simply that globalization and commodification of some sounds is a fact.”

While Rosalía may not have been born into these sounds, or even have a right to replicate them, she does have the artistic freedom to experiment. Sampling helps to develop a global sound, spreading ideas and influences to new areas where they may not be as accessible, consequently giving the musicians who originally created these sounds much more exposure and global support. Yet, it is imperative that sampling such as this is done with extreme care as to not divorce these sounds from their rightful creators and cultures.

Chelita (any pronouns), a Black Indigenous 2SQ DJ currently working in Boston, shared their opinions on the subject, saying, “I think there’s a very big disconnect with people who want to create the samples and use them to their advantage, and those who made the samples and deserve that respect and honor of creating those beats

26

Essentially those who get those samples and who create those samples, those old school DJs, they understand the power and the worth of those who made that happen. [...] It’s all about respect; we just need to respect the tracks that we sample.”

Chelita’s sentiment reflects sampling as honoring those who have played before, and using sampling as a means of keeping these legacies and cultures alive. The essence of sampling lies in appreciation — admiring and loving an original piece of music so much that you are willing to incorporate it into your own sound.

Beyoncé’s most recent release, Renaissance, proves itself as the masterclass of sampling as an act of love and respect, pulling mementos from queer and BIPOC spaces from the ’70s and ’80s into new contexts. The album’s essence is rooted in the music created by and for queer people of color during this time period, drawing from a deep pool of artists who worked to develop both these genres and modern culture in such an incalculable way. Beyoncé’s hour-long anthem celebrates these influential musicians, all while furthering the advancement of these genres.

On the topic of Beyoncé, Chelita says, “I think bringing out these sounds that have been staples in the underground are essential.”

The final track, “Summer Renaissance,” pulls the opening riff and infamous melody from Donna “Queen of Disco” Summer’s “I Feel Love.” In a satisfying conclusion, Beyoncé proves the essence of sampling and its importance to music in all its forms, ending the album with a sweet reference: “Oooh, It’s so good / It’s so good / It’s so good / It’s so good.”

Sampling helps preserve the greats and infuse new music with a glistening sense of nostalgia, but it is absolutely essential that it is done as an act of tenderness. Only through paying respect to the musicians who paved the way will modern producers and artists be able to continue the work of cultivating sound and culture.

28

Nightcore and daycore: born from the internet, most know these genres and the stigma that revolves around them. However, why do I open my Spotify “New Releases” to notice that Lana Del Rey released the sped-up version of her 2012 summer hit “Summertime Sadness” a decade after its initial release? Not to mention “slowed and reverb” YouTube edits of songs such as MGMT’s “Little Dark Age” and “sex money feelings die” by Lykke Li.

And, of course, there’s TikTok. While I no longer have the app, I remember viewing people dancing and making edits to both slowed and sped-up versions of viral songs. Did we think “Slow Dancing in the Dark” by Joji could possibly be any more delayed and heartbreaking? Think again. While I believe this is a result of nightcore, which sprung up in the early 2000s, so many new developments in editing the tone of existing songs to emotionally enhance them continue to transpire.

Nightcore originated in Alta, Norway, in 2002, from Thomas S. Nilsen (DJ TNT) and Steffen Ojala Søderholm (DJ SOS). The dual project of these two artists is literally dubbed “Nightcore” and became the origin of the internet genre’s name. Nightcore is the act of taking a widely celebrated song and hyping it up with speed, usually within a range of 160-180 beats per minute. The duo created over four albums, featuring versions of Eurodance bops with the pitch shifted up.

Despite remaining inactive in the public eye, their music trickled down into YouTube culture. Today, TikTok embodies what YouTube originally did: taking a concept or trend and allowing creators to put their own spin on it in various ways. Think back to the Adult Swim “bump” trend that used the sped-up version of the song “Running Away” by VANO 3000, which samples “Time Moves Slow” by BADBADNOTGOOD. Since TikTok’s main source of content is using music clips for trends, this wasn’t originally a copyright issue but rather a mood-setter. “Time Moves Slow” is perfect for a bump on Adult Swim, but, in the case of this trend, the audio moves too slowly to match the speed and mood associated with short clips.

With nightcore speeding up existing music, there’s a similar genre that does the exact opposite: daycore (my

30

personal preference between the two). No clear explanation for its origins exists, leaving most to regard the theory of speeding up and slowing down songs on a record player as a catalyst. I witnessed daycore emerge once Instagram fan pages for different movies and shows soundtracked “thirst trap” edits to this music around 2016.

Nightcore and daycore cannot be attributed to just one genre: daycore embodies an aural, ethereal, and bedroom pop feel, while nightcore exudes energy similar to hyperpop. These styles are heavily associated with anime, but sometimes the correlations specific to nightcore perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Listeners sometimes associate the edits with high-pitched “anime girl voices” and Vocaloid music like Hatsune Miku. The blatantly racist connotations drawn between anime and this music give way to how western audiences fetishize these otherwise fun and alluring pieces of eastern media.

Nightcore and daycore present the possibility of reimagining the original version of a song that seems impossible to stop listening to until it grows tired. Thinking about the amount of times I’ve heard the song “Chanel” by Frank Ocean gives me a mind-numbing headache. Yet, if I’m trying to chill or feel like deriving a different feeling from it, I’ll probably put on the slowed-down version, just for the fact that it sets a more tranquil and ethereal sonic experience.

Slowing down and speeding up a song represent two different ends of the spectrum: slowing a song down can make it feel more hollow and yearning, while speeding it up can make it more chaotic and exciting. The experience is nuanced and sometimes can result in total garbage, similar to meshing songs from different genres together to create a remix: some just don’t work with an altered BPM, especially if it’s sped up.

I believe this phenomenon is so huge because of the empowerment it elicits. According to Spotify, dancing in the bathroom to a playlist called “You’re in an Edit” is more common than you’d think. This feeling of looking as hot, sexy, or badass as your favorite singer, actor, or character is the most intoxicating when you queue the

31

right music. Songs typically sped up for this purpose include “B.O.T.A (Baddest of Them All)” by Eliza Rose, “Stargirl Interlude” by The Weeknd and Lana Del Rey, “Me and Your Mama” by Childish Gambino, “Tek It” by Cafuné and “Jealous” by Eyedress (which is already fast-paced on its own). Admit it, you’ve posed in the mirror and strutted across your room listening to at least one of these songs.

The closest scientific explanation for nightcore and daycore comes from an article called “Effects of Musical Tempo on Musicians’ and Non-musicians’ Emotional Experience When Listening to Music,” which describes tempo, BPM and their psychology devoid of the cultural and contemporary effects that I divulged. Music with a fast tempo arise the most positive emotional reactions due to the activation in the temporal and motor processing areas; medium tempos close to humans’ physiological rhythms arise a strong emotional response by entraining the autonomic neural activation of emotion processes; slow tempos receive the lowest emotional valence and weakest arousal.

The ways this phenomenon impacts us on an individual scale is subjective to the specific song and remix, and many detest altering a track. Some explanations involve legality. Don’t want to get a copyright strike for including a song in your short film? Not interested in making your own music but need some extra bank? Alter an existing song to create a different aura and garner a ton of views from people who will enjoy it just as much as the original. Most importantly, these styles add a simple, personal touch to the music someone enjoys. I’ll admit, I definitely have a “slowed and reverb” playlist saved on my YouTube account for future listening. It’s just that good and will undoubtedly continue to be.

32

Nightcore and daycore present the possibility of reimagining the original version of a song that seems impossible to stop listening to until it grows tired.

a new sound and vibration to beat with. Bored with the despondent moans of Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Alice In Chains, the 2000s underground scene — much like that of underground punk in the 1970s — craved something new, fresh, and upbeat without the gloss of ’80s pop.

Beginning with James Murphy’s (LCD Soundsystem) creation of DFA Records, the basements of Brooklyn rebirthed the dirty, neon and voltaic sound of DJs and techno artists. Just as the techno, pop, and synthetic sound of the ’80s rejected the radical, raw punk of the ’70s, the 2000s rejected the sound of the ’90s. Yet again, history repeats itself with the rise of electro-punk, house music full of head-pounding beats and crawling rhythms as a rejection of the trap and cloud rap that engulfed the 2010s through iconic artists like Travis Scott, Kendrick Lamar, Lil Yachty, and Future.

This rise in electronically warped music is related to the electronic world we live in today. Due to the development of computer technology and the increase in its efficiency, the heavy equipment and accessories used to create unique, synthetic sounds aren’t needed in the same way; now it’s much more accessible because production can be completed digitally via one or two applications instead. We live in an era of fast-paced movement, constant technological advancements and an overwhelming consumption of technology. Our attention spans are shorter and our thirst for the “next thing” is stronger. What better way to reach us than through music that encourages and encapsulates this sonic, computerized and synthetic way of life?

Chelita is part of a music collective called Clear the Floor, Boston’s only BIPOC-centered collective. “Everyone who is part of Clear the Floor is a person of color. My partner and I created CF knowing the city doesn’t have space for people of color DJs, specifically who play club music,” says Chelita. “There’s absolutely no space for BIPOC to feel safe and play shows that are run by Black people. A lot of people out here feel uncomfortable because of how white the scene can be.”

Chelita defines their craft as a complete genre-bending sound, influenced by Latin and Miami-based artists from

their childhood like Dembow and 2 Live Crew, whose music encourages freedom and community through dance.

“My favorite thing is seeing my audience at the parties and spaces that I play actually move their feet. You see a lot of people swaying and bobbing their heads but I always have people come up to me and say, ‘I haven’t moved that way in years,’” recounts Chelita.

When asked about Boston’s music scene, Chelita shared the sad truth of how much potential lies in the city’s underground electro house scene that just isn’t given the platform to perform. “I wish the city was less gatekept in the nightlife industry. In the underground, we are all working together to make a platform here. We are making sure people know what is coming out of Boston.”

Annie Lew, a sophomore at Northeastern, is an up-and-coming Boston-based DJ integrated in the underground electronic music scene. Originally from Connecticut, Lew says Boston is a hub for music students, home to a wide range of colleges that provide resources and opportunities to perform.

“After moving to Boston I understood that art is more universal. I definitely felt a shift in [my] motivation and drive when I moved here,” she says. “Boston is the best city to become a musician in order to prepare for going out into the music world elsewhere.”

Lew first got into DJing after spending four months in Rome, Italy, and gaining exposure to live electronic music. “You experience this collective unity with everyone, which is such an empowering feeling,” says Lew. She is influenced by the fast and intense sounds of hard techno from artists like MDR, as well as electronic alternative artists like Tame Impala.

Lew says Boston’s music scene is home to a small artist community that allows her to get more bookings and make a name for herself much faster than if she were in New York City.

“[Boston] is not concentrated with as many DJs. I don’t think I could be where I am in Boston today in any other

place,” she says. Province 44, a college-student oriented house and techno music collective based in Boston, is a collective Lew previously worked with. “Because the community is so small, if you’re a versatile DJ, you kind of just play with everyone. The people who are going to the techno events go for the music, not for the party,” she says.

Being a younger girl in the DJ scene, Lew is pushed to work harder than other artists. “A lot of people see you as a sexual object or don’t take you seriously, but I think being a girl gives me more motivation because I haven’t met anyone like me doing this,” asserts Lew. “ I want people to know me as Annie Lew and know me as someone who has done it by herself. I want to prove to people that you can do it if you really want to.”

Lew is a Resident DJ for the music collective Infra Boston, as well as a Booking and Business Administrator for their agency. “Infra is one of the main hard techno collectives, bringing in the big names from Europe,” says Lew. DJ Chelita also worked with Infra, characterizing the underground community as one that’s actually pushing the boundaries of the electronic scene in the city.

Lew feels motivated to bring Infra to the next level. “Infra has so much power right now because they are doing so many good things for the city,” she says. Right now, Infra is drawing in the impressive crowds similar to that of the same basements in New York from the 2000s electro scene, which cultivated names like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the Strokes, and the Rapture. Infra is the precursor to the music that will define the electronic age we are living in.

Growing up in an era headlined by the echoes and intonations of music characterized by the lo-fi, hazy and relaxed beats of cloud rap meshed with the grimy, more rhythmic rap of the trap genre, I see the thirst for a new, crisp energy and tune. That tune is electronic.

proclaimed the angst-ridden words that breathed emo music into life almost 40 years ago. Before the belt chains, the smudged eyeliner, and the dyed-black hair, there was “Deeper Than Inside” by Rites of Spring.

Washington D.C., 1985: alternative subcultures overruled the city, and acid-wash jeans are about to become more in style than ever. The 9:30 Club, D.C.’s home for punk music, is the place to be, and Rites of Spring frontman Guy Picciotto just blessed the airwaves with his impassioned voice exploding over the climaxes of their debut album, End on End. Rites of Spring introduced the world to a new outlet for musical expression. They possessed all the frenzy of punk music with a newfound twist through deeply personal and emotional lyrics — a level largely unseen in the hardcore movement. Following the formation of Rites of Spring, the band and others who followed founded a new social movement by 1985 that ascended to the come up: Revolution Summer.

Revolution Summer represented the punk scene’s response to the violence and racism erupting in D.C. by 1984. The movement embraced feminism, animal rights and vehemently (sometimes violently) opposed the presence of skinheads— a subculture that, while originating from “apolitical” working-class youths in the UK, devolved into a community running rampant with far-right, neo-Nazi rhetoric. While white hardcore bands mainly spearheaded the movement, its philosophy and core beliefs drew upon others that came prior to it, such as the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Movement.

Rites of Spring reigned in the foreground of Revolution Summer, along with bands like Beefeater and Embrace. Out of the bands that formed during the movement and gave way to music groups to come, Ian MacKaye’s newly formed band Embrace became an important standout. By following the blueprint of singing vulnerable lyrics to the point of exhaustion over an industrial-like sound, Embrace’s presence in this new, odd scene lent itself to an emergence out of the obscure.

It wasn’t until the following year, in 1986, that the

40

“I’m going down, going down, deeper than inside -– the world is my fuse,”

word “emo” entered the lexicon of music. In their January 1986 issue, Thrasher Magazine used the term “emocore” to describe the sound that spread its wings out of D.C. and made its way down the West Coast to the Midwest. This wasn’t the most readily-accepted term, as illustrated by MacKaye’s less-than-appreciative reaction to the Thrasher article.

While performing at D.C.’s 9:30 Club, MacKaye spoke during an intermission between songs: “‘Emo-core’ must be the stupidest fucking thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life…‘emotional hardcore.’ As if hardcore wasn’t emotional to begin with.” Despite the malaise and occasional outright hatred towards the maligned genre name, “emo-core” caught on. By the early 1990s, the angst-ridden catchall slashed down to the infamous term many embrace today: emo.

Though much of the emo music from the mid-80s contained an obvious punk influence, the emo music that came out in the later ’80s and early ‘90s blended the prior hardcore sound with prose-like lyricism and tempos that could change in the blink of an eye. Bands like Indian Summer and Moss Icon managed to maintain the principles of punk while having a distinct sound that set them apart from their predecessors.

The instrumentals rung loud and abrasive, but melodic. The singing was anything but technically sound, yet still the rawest, unapologetic, laced-with-emotion screaming one could ever imagine. The lyrics, even while seeming incoherent and nonsensical at times, were honest and defenseless. In its origins, emo endured as a groundbreaking genre that retained the against-the-grain persona that thrived in the hardcore scene. Yet, despite the grassroots, anarchic appearance of emo, the genre remained as problematic as similar musical styles

41

Yet, despite the grassroots, anarchic appearance of emo, the genre remained as problematic as similar musical styles popularized during this time.

popularized during this time.

The origins of emo consistently erased musicians of color, specifically Black musicians. To this day, emo music is seen as a white genre made for and by white people. This perception isn’t wrong, per se, but the assumption that often shrouds this perception — that Black people aren’t and never existed in emo — is undeniably false. Black people always participated in emo music, with Black bands specifically shifting sounds within the genre. Though emo’s ideals claim to center around emotional vulnerability and a culture of acceptance, Black bands face a lack of support, recognition and credit within and outside of the emo community.

The story of the Black-fronted group Yaphet Kotto is a testament to this larger phenomenon of BIPOC-fronted or all-BIPOC bands, regardless of genre, receiving their flowers far less often than that of white bands.

Formed in 1996 in Santa Cruz, CA, Yaphet Kotto wielded the then newly-curated emo sound to communicate the frustrations and grievances frontman Mag Delana felt towards the American government. Being one of the first bands to successfully harness the “screamo” sound, Yaphet Kotto employed experimental dissonance and dynamics as a backdrop to lyrics that touched upon the genocide of Native Americans (“The Killer Was In The Government Blankets”) and the legacy of segregation in America (“Reserved for Speaker”). Despite their key role in introducing the masses and Californian underground to screamo as an emo subgenre, the band remains far more obscure compared to their white contemporaries.

Yaphet Kotto’s music is almost exclusively streamable on YouTube. This is another common theme when comparing the longevity of relevance between white and Black bands in the early days of emo: had these bands received equitable profits and recognition, it is likely their music would be as at our fingertips as others. Often only releasing one to two albums in the span of a one to three-year run, the BIPOC groups of this era didn’t seek fame or even recognition — just pure, purposeful noise. Despite the discography consisting, on average, less than 30 songs and scattered across streaming platforms

42

(both modern and no longer with us), the music emerging from this era undeniably instrumented the evolution of the genre.

By the mid-2000s, much of emo music diverged into more discernible categories. It didn’t take long before subgenres like “Midwest emo” spread throughout the, well, Midwest, while pop-punk and screamo continued to dominate both coasts of the country. Despite tonal shifts in the genre, the sounds of the newest breakout bands, along with more recognizable now-veteran emo bands, still trace back to the founders. The Get Up Kids and American Football (featuring Mike Kinsella of Cap’n Jazz fame) corralled the classic Midwest emo sound of raspy vocals layered over distorted guitars.

In more modern times, these categories are less divided by region, especially as bands plateau in their inclination to define themselves by one genre. This isn’t to say that no “revivals” of the early sounds of emo haven’t occurred since the ’80s and’ 90s. Age Sixteen, another widely-underrated Black-fronted band, is a quintessential example of a post-origins group that captured that original emo sound. Active between the years 2008 and 2011, Age Sixteen provided a blast to the past with its complex drum beats, scream-sung lyrics, and spacey reverb. Joined by bands like Snowing, Into It Over It and countless others, Age Sixteen depicted one of the many groups a part of the so-called “Emo Revival.” However, many of these bands — and “Emo Revival” as a whole — largely dissolved by the mid2010s.

Today, most of emo looks and sounds a lot different than it did in the ’80s and ’90s, with the sound surviving in the hands of occasionally eyeliner-clad pop-punk vocalists that aren’t just white men. It would be dishonest to say that white men still don’t make up a large part of the mainstream emo scene, but it’s important to give recognition where it’s due.

Paramore and Pierce the Veil, both powerhouses in the scene, made the comebacks of the century this past year, with transcendental emo kids of both the millennial and Gen Z variety taking to TikTok to kick mainstream emo to

43

the top of the charts once more. But it’s not all icons of the 2000s making the rounds on emo charts. Newcomers to the genre generate waves of their own in the scene, such as Meet Me @ The Altar.

Formed in 2015 as a remote project between bandmates Edith Victoria, Ada Juarez, and Téa Campbell, Meet Me @ The Altar released their first EP Changing States in 2018. They’ve mounted a steady journey to the top ever since. Since their takeoff, the band performed with All Time Low, MUNA, Green Day, and headlined the When We Were Young festival in October 2022.

To see where emo as a genre is heading, I think we only need to look at newer bands like Meet Me @ The Altar’s success and well-deserved stardom. The current blend of more modern pop-punk with the activism and passion for change that characterized early emo makes for a compelling sound. Bands and solo artists like Magnolia Park, Action/Adventure and WILLOW are showing just how far emo and post-hardcore have come in terms of the evolution of sound. The vocals vary from soft and eerie to hoarse and belting from band to band. The use of bass or drum patterns switches from punk to indie-influenced, depending on which Spotify playlist you click on. Emo embodies something much bigger than a genre, but a subculture — and occasional global phenomenon — based on exploration and experimentation. Weirdos, freaks, and basic bitches alike find enjoyment in the music and atmosphere.

So this one’s for the OGs in the scene, those that moshed at basement shows; and this one’s for the teens of the 2000s, those that washed Xs off the back of their hands to drink like the bands; and this one’s for the people that came to age in an emo drought, only to have the Spotify Wrapped of their first years of college be chock full of their middle school favs, with music both new and nostalgic. Regardless of which generation you’re from, if you’re new to emo or a seasoned player, the scene — from the pit to the stage — is in good hands. The world is your fuse.

44

When it comes to soundtracks, music possesses the ability to elevate any media it’s paired with — not as a side piece, but as an amplifier for the tone and atmosphere of the content. Video games offer an opportunity to experience this effect more than any other media format. By nature, they are an immersive art form, meant to be engaged with in a way that gives consumers control over their experience. The visuals and audio of video games work together to draw you in and provide a personal connection to the story.

Video games didn’t always exhibit this relationship, however, and the shift toward symbiosis of sound and imagery was pioneered by none other than Nintendo’s biggest household name: Mario.

Nintendo always pushes the envelope for game development, spearheading pivotal innovations in the industry. They’ve left no stone unturned when it comes to challenging the boundaries of what games can do, and music is no exception. Super Mario Bros. (1985), created by Shigeru Miyamoto and with music composed by Koji Kondo, represents their break-out star. The game’s success can’t only be attributed to its music — Nintendo couldn’t create a franchise with such staying power if there weren’t several factors working together — but the soundtrack certainly held a hand in distinguishing the game as a unique contribution to the market.

Anyone can admit that the main “Overworld” theme is catchy as hell — even people who haven’t played the original game or subsequent installments will recognize the tune, especially since Mario is entrenched in popular culture. The music from these games is powerful in its ability to maintain nostalgia: people all over the world grow up playing these games or have been exposed to them somehow, since the Mario franchise is Nintendo’s highest-grossing property.

The relevancy of Mario only continues to expand as Nintendo produces more games. But how did the franchise’s music manage to have such a lasting impact on the way we experience video games? The main theme earworms its way so deeply into our hearts and minds, a testament to music’s power to enhance our individual experiences with

47

media.

To fully grasp the impact of the Super Mario Bros. soundtrack, we need to situate the game in a broader historical context. In the years leading up to the game’s creation, arcades sustained the gaming industry. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, a home-console war broke out between a plethora of video game companies in the U.S. (most notably Atari). These companies fought to bring video games to consumers’ homes, but this battle ended up oversaturating the market with poor quality games. This led to a large-scale market crash and recession in 1983 that left many people believing that the gaming industry was doomed in North American markets.

Enter Japanese game company Nintendo, who previously established an arcade hit with Donkey Kong (1981); Mario made his first ever appearance as the enemy-fighting plumber we know today. Nintendo took this opportunity to release their Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) console in North America in 1985, a test launch of their redesigned Famicom console previously released in Japan. The NES did extremely well in North America, with games including — you guessed it — Super Mario Bros.

The reason Nintendo succeeded in expanding outside of Japan stemmed from their competitive, passionate approach to video game engineering. The company’s mission statement is centered around “flexibility, uniqueness, sincerity, and honesty,” unconcerned with improving upon something that already exists but rather with trying new things entirely. At the time of the 1983 market crash, Nintendo also provided what any consumers needed, not just gamers in North America. They administered assurance that they prioritized quality first and cared about consumer interest, a rarity amongst other low quality games.

Nintendo offered fresh content that also revolutionized the industry in many aspects. A whole dissertation could be written about the many elements that made Mario influential to game development, but this piece is primarily concerned with the music — and there is a surprisingly rich complexity around the original Super Mario Bros. soundtrack.

48

If you’re looking for a digestible deep-dive into the history and music theory behind Mario music, Koji Kondo’s Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack by Andrew Schartmann is practically a holy text. On composer Kondo’s work, Schartmann writes, “Why does Kondo take the most pride in his earliest hits? Because it was in these early pieces that he first understood how he was different from those who came before him. More than just a handful of catchy tunes, Super Mario Bros. is the cradle of Kondo’s lifelong contribution to video-game music.”

Kondo’s position at Nintendo resulted from the company’s unprecedented decision to hire a composer for their video game soundtracks. Before, arcades shaped the general composition of video game music. The music meant to entice players to engage with the game, drawing you in with its flashing graphics and energized 8-bit tones. Once the game clutched the player in its grip, the music would become background noise. At the time, music came in post game production, almost as an afterthought.

During Super Mario Bros.’ production, Nintendo did things differently, giving Kondo a chance to compose music during the development of the game. In an interview with Wired in 2007, Kondo discussed the process of composing for the game: “I wanted to create something that had never been heard before, where you’d think ‘This isn’t like game music at all, isn’t it?’... First off, it had to fit the game the best, enhance the gameplay and make it more enjoyable. Not just sit there and be something that plays while you play the game, but is actually a part of the game.”

Visual by Ali Madsen

Kondo strived to make music that interacted with the visuals to intensify the emotional and physical immersion into the game. The main theme we know and love is called “Overworld.” Rewritten many times in order to accurately fit the gameplay, the C-major key uses no sharps and flats and helps create the jaunty, adventurous tone that matches the sprightly visuals. The most impressive aspect of this song outside of its inherent catchiness is that Kondo created it within the physical limitations of the NES console. The console could only produce a limited number of tones, obligating him to find some way to mimic different lines (like melody

50

and percussion). The NES console also struggled with memory issues and couldn’t handle long strings of music, so Kondo played around with repetitions and how to cleverly loop sections of the melody without driving a player crazy.

Interestingly enough, it’s possible he purposely went against this technique later on with the “Underworld” theme that plays over underground levels. It’s quite short, and the repetition of only a handful of notes while going through increasingly hard castle levels is a clever way to create tension for the player. The soundtrack enhancing the gaming experience doesn’t end there — once you get to the “Underwater” theme, the soundtrack becomes a waltz, which Kondo composed specifically to remind players of the lilting quality of waves. To contrast the “Overworld” theme, the “Underworld” theme is dark and brusque. Kondo created each song as a seamless extension to the game’s visuals, the intention influencing certain mental associations.

Somehow, Kondo constructed the soundtrack in such a way where the rhythm of the music seemed to match the cadence of one’s gameplay, an eerie tactic attested by many players. This carried into later installments of Super Mario Bros., with enemies stopping to dance on the “wa-wa” beats in the soundtrack — an animation that is, personally, very endearing and contributes to the whimsy that these games ooze.

All the Mario games are also laden with sound effects that blur the lines between player and media. Collecting coins yields a two-note sound, a B going up to an E, that is reminiscent of a cash register or a Vegas slot machine. The physical note change going up is also metaphorically tied to the act of gaining money associated with a positive action. Mario does love its metaphorical sounds, though, which is why notes slide upwards when Mario jumps and downwards when Bowser falls into a pit of lava. Collectively, soundtrack and sound effects create a direct association between a player’s actions and what is occurring in the game, making it the most intimate way to experience a piece of media.

To this day, it’s hard pressed not to recognize a Mario

51

song. Some personal favorites that are easily recognizable able are “Ghost House” — often accompanied by visuals of dark, ominous rooms and Boos gradually creeping closer — and “Coconut Mall” — a playful number laden with piano, steel drums, and saxophone that make it impossible not to dance while driving down escalators.

Nintendo often takes their own themes from the original game and remixes them for new releases, creating a brand that injects nostalgia into every Mario game. The music across the whole franchise, whether it’s from a new game or an old one, contains a certain playfulness that anyone will recognize. Play an audio on TikTok and hordes of people will instantly have an association to the games. Use the coin sound effect in your song — as Charli XCX does in her song “Boys” (2020) — and listeners will be thinking of those gloriously shiny star coins. Remix the original “Overworld” theme — like Lucky Dube in their song “Different Colours, One People” (1993) — and create a mental link between lyrics about solidarity and the wistful, unifying tune of childhood. The history of Mario’s famous theme is a true testament, more than any other piece of media, to how you can perfectly use music to enhance stories and our experiences consuming them.

52

The easy answer is anyone, as it’s a form of public entertainment.

Surely anybody can stroll through the illuminating Theater District of New York City, making their way to work where they handle the operations of riveting plays and musicals. Anyone can act as a Broadway performer, and anyone can buy a ticket to a show, right? Wrong.

One might assume that this is because it takes a lot of hard work to get into the Broadway world, and this is true. An aspiring actor must train incessantly, taking acting, dance and voice classes. They’ve got to seize that “it factor” and the ability to captivate audiences, often for long periods of time. On the other side of the spectrum, someone who wants to hold an authoritative or executive position in Broadway must either be a child of nepotism or network intensely to make connections and be well-versed in the world of theater. But this isn’t a matter of talent or skill or even hard work; it’s a matter of opportunity. For people of color, there are undeniable barriers to breaking into Broadway, whether that be running the production, performing on stage, behind the scenes, or sitting in seats among intricately carved paintings and grand marble columns.

From beginning to the end, racial inequity plagues the Broadway process. AAPAC declares 93.8 percent of directors on Broadway were white in the 2018-2019 season. Broadway directors audition and cast actors as well as assemble and oversee the production team. It’s no wonder BIPOC talent isn’t proactively being hired, because there’s not active representation in the people that are hiring them. The same could be said of writers, stage managers, and producers. In this same season, 60 percent of actors were white.

Student Beyoncé Martinez ‘24, who worked on the pre-

54

Broadway run of Neil Diamond’s musical says “[the experience] made me realize that the world and the career that I’m stepping into is so damaged in the sense that we’re still dealing with racial disparities even in theater.” There is a lack of representation behind the scenes, too. BIPOC actors struggle with makeup departments that wash their rich skin tones out and hairdressers who do not understand 4A-4C and sometimes even 3A-3C hair textures. Even Broadway audiences remain overwhelmingly white.

but why?

At its root, this is a systemic issue that leaked into the music scene and caused rot to fester from the inside out. It is important not to forget that Black theatergoers were intentionally barred from white theater productions and theaters, especially in the time of Jim Crow where segregation ran rampant. In the modern day it is impossible to ignore that mainstream theater is white theater. If a BIPOC actor wants to make it to Broadway, they’ve got to somehow knock down the walls of oppression and microaggressions first. Starting as early as elementary school in BIPOC-majority schools, this might manifest as overcoming the systematic underfunding of art programs and trying to seek it out elsewhere. Later on, jumping over the hurdles of racial wealth gaps and invisible anti-discrimination policies persists as another struggle.

The second issue is visibility, which intermingles with comfort. Segregation may be illegal now, but there are still major racial disparities. I remember my first time seeing Hamilton live in Chicago, and my school of Black and brown kids representing one of the only racial and ethnic minorities present. In that moment of loneliness, despite feeling connected to the music and dialogue, I felt a lack of connection with my fellow viewers, which subconsciously influenced my entertainment experience. Being surrounded by a sea of white people can make BIPOC audiences feel a sense of alienation. Because of this, many would rather stay home and listen to Broadway soundtracks, or avoid associating with the art form

55

altogether.

The Sixth Love by

Then there is the matter of financial woes and gaps. To talk about race without talking about class and privilege would perpetuate a disservice; Broadway is elitist, and it isolates middle and low class BIPOC communities. There is a certain glamour associated with Broadway, and that’s not by accident. People who go and see Broadway are significantly more affluent than the average American, with over 60 percent of Broadway-goers earning more than six figures a year. Only a fourth of Americans earn that number, and when African-American workers continue to earn far less than white counterparts, racial disparities press on.

This intermingles with the concept of access as well, how growing up in rich, art-heavy, white communities can influence your chances on Broadway. In her performing arts classes, Martinez and many of her Black friends on campus experience a sense of imposter syndrome.

She explains, “My fellow white peers have been doing theater since birth. They’ve been in… arrays of shows and also have access to theater mentors and… to higher-ups in the theater boards of their high schools.”

This isn’t an accident, or an unfortunate coincidence. Time and time again, history shows that minorities just aren’t given the same opportunities that white people in this country are, and it causes a disconnect when it comes to networking circles and connections. As I stated earlier, this is key to making it on the big stage.

Karissa

VisualbyAshleyOnnembo FlashbyKennyWood

Schaefer

One reason for the lack of representation concerning Broadway that we don’t talk about nearly enough is the issue of relative material. Seeing yourself in Broadway actors and directors is an important kind of visibility. Josh Streeter, a graduate professor who does project-based theater work surrounding equity in the community, explains some of his job: “I work with companies that are like: ‘Ok, let’s look at your season: you have one show by a person of color. That’s not acceptable anymore.’” When pieces resonate with BIPOC audiences, BIPOC viewers are more likely to attend and pick up that Playbill.

56

One example is Slave Play, created by Black and gay playwright Jeremy O. Harris. Another is Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, whose fast-rapping cadences and iconic one-liners are modeled after songs from phenomenal artists in the Black community such as Jay Z, Mobb Deep, Biggie, DMX, Beyoncé and the Fugees. Additionally, Hamilton features mostly BIPOC actors such as African-American Leslie Odom Jr. and Lin-Manuel Miranda himself, who is Puerto Rican; white actors here are the minority. The ticket prices aren’t changing to accommodate those who may be less fortunate, but the shows that include cultural idiosyncrasies and features BIPOC actors tend to be more appealing to BIPOC consumers.

This being said, shows like Slave Play or The Lion King draw links to another issue called color conscious casting, where BIPOC performers are only casted in shows about BIPOC stories. Such was the case with The King and I; the Asian-American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) did a study in which they found that the Lincoln Center’s production of The King and I accounted for 62 contracts to Asian actors (including understudies and replacements) and 53 percent of all Asian actors employed in the 2014-2015 season. Many of the characters in the musical are Thai or of Asian heritage, which is great for visibility’s sake, but also typecasts Asian actors. There’s no reason why an Asian actress can’t play Glinda in Wicked or an Asian actor play “the Angel of Music”, but these roles are often given to white actors instead.

So what can we do? As discouraging as all of these issues might sound, it just proves and reiterates that these BIPOC Broadway members, in all aspects, are needed. Those who can need to promote equity, making things as fair as possible for those who are on a lower playing field (thanks to the system). This means evaluating who we’re putting in authoritative positions, incorporating diversity and inclusion laws and initiatives in the workplace, fostering open-minded casting and pushing out resources to less fortunate communities. Equity is something we need to strive for, so that it’s possible for all kinds of BIPOC talent to not only break into the Broadway world, but thrive there. The fight is never over.

57

Gordon Raphael’s memoir, The World Is Going to Love This: Up From the Basement with The Strokes, reads as though you’re entering a time capsule into the last great era of rock ‘n’ roll — told from the voice of the man who started it all. Raphael’s work with The Strokes has become stuff of legend: after a chance meeting at the Luna Lounge in New York City, Raphael produced the band’s seminal debut, Is This It, catapulting them into the mainstream and bringing garage rock to the forefront of popular music. Over two decades later, Is This It remains a legendary rock staple that ushered in a wave of rock bands to follow — along with a legacy of leather jackets, skinny jeans, and a “no fucks given” attitude.

Raphael also writes of meeting The Libertines in their early days and almost producing their first album, as well as discovering Regina Spektor and forging a brilliant musical relationship. In discussing his Seattle roots, approach to music production and thoughts on the early 2000s rock culture, it’s clear that Raphael’s passion for music goes beyond the average listener.

Paulina: This is by far the most detailed music memoir I’ve ever read. You’re so meticulous [regarding] the tiniest details, and I found it fascinating! How did you remember everything?

Gordon: I think [that’s] funny and interesting because many of my friends say that I have a very bad memory! My grandfather always told me that he had a strange memory, where if it was important or interesting to him, he would remember it… perfectly clear, and anything else would slip by. And I think it’s that way with me, [with] things that I find fascinating, and events where I was in the moment and feeling the power of life going on, like [a] vortex. It seems like I can remember the details and feel the sensations very clearly, still.

P: Do you have any favorite musicians from childhood that sparked inspiration as a musician and producer?

G: My dad was a jazz musician, and he would play his horn to loud records late at night , and I just thought that was annoying! It kind of made me not like “big band” jazz very much. But then, when I was about 10 , or

and being yelled at for everything. I think we felt more redeemed, [with] the crazy, quirky stuff we were interested [in]. Everybody [would tell] us, “Get a job! This is never going to serve you! You’re wasting your fucking time! You’re just doing things that nobody’s interested in!,” to suddenly, “Hey, I’m on a tour bus and we’re going across America, and I can afford to go to the pawn shop and buy a new keyboard!” This was a vindication.

P: How did your experiences in your bands Sky Cries Mary and Absinthee prepare you to become a producer?

G: Before the time of success, I was recording my own stuff, because of that childhood belief of [having] so many clever ideas and [thinking] the words that come out of my pen are brilliant! I recorded all my songs, and I’ve learned lots of tricks to make things sound cool and interesting. I [often] used this little synthesizer called the ARP Odyssey to make outer space noises and weird psychic sounds from another realm that were always going on in the backgrounds of my songs. When I actually became a producer for other people, I just had all this experience of my own music to fall back on.

P: It seems like you took the approach of world-building when you created your music — you’re not just listening to it, it’s a wholly immersive experience.

G: Yeah, the world [grew] the more I got into mastering music or… play[ing] the piano or [making] a song. At some point, after many experiments and failed songs, I crossed this line and [thought], “Hey, I did that. That’s really cool!” I want[ed] to show all my friends and [they’d say], “Oh, no, here he comes again, with another cassette tape in his pocket. He’s going to play 30 minutes of weird stuff for us. Oh, should we let him in?” But yeah, the world that was being created was so fascinating that I had to go back to check if it was still there [and] see if I could still go in or make another discovery.

P: You also mentioned in the book that the internet revolutionized everything. How did that affect your approach to the industry altogether, when it came to producing?

G: In the previous generation — which I got to actually experience a little bit of in New York — artists and weirdos would hold parties, and it would be really interesting. And in the late ’90s, it was new ”dot com” corporations holding the parties. They were cool parties because they had enough money [to] afford these strange avant-garde artists and performers, [which was] spectacular! As an unemployed musician, I was getting work [from new websites pitching], “There’s a new yoga website popping up, why don’t make yoga music for a while?” [And I’d say], “Okay, I’ll make electronic yoga music.” So there was work to be had, and there were some really good parties from that scene. But there was also this sense of like, “What is going on here?” All these finance bros are moving into the neighborhoods where [there] used to be funky artists and interesting alternative people. Now it’s all these guys intent on making millions with the new medium of the internet.

P: That’s so interesting to hear; I grew up with the internet and am used to streaming services and all that. It seems like there was a major shift almost out of nowhere.

G: For me, it was great because I could write and communicate with people all over the world and have instant friendships and communication. Something like The Strokes may have been… one of the very first bands ever promoted on the internet in this new way.

P: That’s so wild to think about! In the book, you mentioned all these underground artists that you encountered when you first moved to New York; was there anyone that stood out to you that you still listen to or think about today?

G: That’s interesting. The real inspiration [behind] New York when I moved there, and whenever I visited previously, was this one little street in the East Village, St. Mark’s Place. Any free time I could possibly have –which is a lot because I wasn’t really worth very much —I would just go to that street and walk up and down from Tompkins Park, up to Third Avenue. The things you would see on the street on a Friday night, on a Saturday night… it was like a free circus, where you sit there

and look at the parade going by. It was so inspirational to me, it really gave me a lot of vitality. I was always thinking, “Wow, look at the sea of humanity.” There were very interesting people from all over the world: poor, rich, every kind of person was there on that street [joining] this parade.